1. Introduction

Global changes in phosphorus cycling at the Precambrian−Cambrian boundary (Brasier, Reference Brasier, Lipps and Signor1992) caused the worldwide appearance of major phosphorite deposits (Cook & Shergold, Reference Cook and Shergold1984). Siliciclastic successions of the East European Platform (EEP) retain a record for some of the latest Neoproterozoic (Ediacaran) and the earliest Cambrian climatic and biotic events, including the rise and disappearance of Ediacaran biota and episodes of phosphogenesis (Sokolov & Fedonkin, Reference Sokolov and Fedonkin1990). Phosphorites did not form major deposits on the EEP: the most phosphorus-enriched members of the southwestern margin of the EEP (Cis-Dniester region) contain only 1.8–8.0 kg of phosphorite concretions per m3 (Kopeliovich, Reference Kopeliovich1965). Authigenic phosphates (nodules and cement) were found in the latest Neoproterozoic reference successions of the EEP, at the level of extinction of Ediacaran biota.

Authigenic sedimentary phosphate and biogenic apatite are the traditional substrates for determining Nd isotope composition in ancient marine facies (Shaw & Wasserburg, Reference Shaw and Wasserburg1985). Concentration of rare earth elements (REE) in phosphate, reaching hundreds of thousands of ppm, is considered to be the result of a substitution mechanism in which Ca is replaced by REE (especially intermediate REE: Nd, Sm, Eu, Gd) during recrystallization of pristine phosphate during diagenesis (Reynard et al. Reference Reynard, Lécuyer and Grandjean1999; Trueman & Tuross, Reference Trueman and Tuross2002).

Wide occurrence of Fe sulphide in fine-grained clayey shale and silt is a specific feature for the Ediacaran sedimentary rocks of the EEP (Sochava et al. Reference Sochava, Podkovyrov and Felitsyn1994). Most of these sulphides (mainly pyrite and marcasite) have been formed at synsedimentary and early diagenetic stages (Kopeliovich, Reference Kopeliovich1965). Concentration of REE in diagenetic sulphide amounts to tens of ppm, as shown in pyrite from the sedimentary Mezozoic and Palaeozoic cover in the western part of the EEP (Shatrov et al. Reference Shatrov, Woitsekhowsky and Sirotin2007). Similar values of bulk REE content have been registered in metamorphic gold-bearing pyrite in Jiangxi Province, China (Mao et al. Reference Mao, Hua, Gao, Li, Zhao, Long and Lu2009). REE incorporated into Fe sulphide can retain the Nd isotope signature of surrounding marine facies by analogy with authigenic phosphate. Occurrence of iron sulphide and authigenic phosphate at the same statigraphical levels on the EEP permits comparison of the Nd isotopic signatures in both minerals.

In this paper we present new Nd isotope data for Fe sulphide: authigenic phosphate from two reference sequences of the Ediacaran and Early Cambrian siliciclastic sedimentary rocks of the EEP. A specific goal of this study is to evaluate the suitability of Nd isotope systems in authigenic Fe sulphide for the estimation of Nd isotope signatures in ancient water. For that reason, samples from drill cores with coexisting diagenetic Fe sulphide and phosphorite from two regions with Ediacaran successions on the EEP were selected.

2. Geological setting

The Upper Neoproterozoic and Lower Cambrian sedimentary and volcanic successions underlie the EEP in two areas – the Cis-Dniester region and the Moscow syneclise. According to the palaeogeographical reconstruction, the basins were relatively isolated, and the thickness of the latest Ediacaran siliciclastic sedimentary rock is c. 500 m in the Cis-Dniester region and more than 700 m in the central part of the EEP (Sokolov & Fedonkin, Reference Sokolov and Fedonkin1990). The studied successions are located near the town of Rybnitsa, (Cis-Dniester region, Republic of Moldova) and in the vicinity of Gavrilov-Yam settlement (central part of Moscow syneclise, Russian Federation), where the drill hole penetrated a central part of the EEP. More details concerning the stratigraphy and composition of the studied successions are presented in numerous publications (e.g. Vidal & Moczydłowska, Reference Vidal and Moczydłowska1995; Strauss et al. Reference Strauss, Vidal, Moczydłowska and Pacześna1997; Felitsyn et al. Reference Felitsyn, Vidal and Moczydłowska1998).

The Upper Neoproterozoic unmetamorphosed sedimentary cover is largely siliciclastic and contains two horizons enriched with phosphorus (Fig. 1). The Ediacaran phosphorite nodules in the Cis-Dniester region (Nagoryany Fm) were discovered in the middle of the nineteenth century and later were intensively examined. These phosphorite nodules, with a regular spherical shape from 0.5 to 20 cm in diameter, a tuberous dark brown or black surface and a radial inner structure, occur in 10−15 separate layers from Fe-sulphide enriched black shale. Concretion development took place in soft sediment, suggestive of the early diagenetic nature of the phosphorite (Kopeliovich, Reference Kopeliovich1965).

Fig. 1. Simplified lithostratigraphy of the Ediacaran – Lower Cambrian successions in two sites on the East European Platform, with secular variation of phosphorus content and sampling location (circle – phosphorite nodule; asterisk – sulphide aggregate). Stratigraphic units according to Sokolov & Fedonkin (Reference Sokolov and Fedonkin1990).

Original studies of phosphorus distribution in the Gavrilov-Yam section revealed a c. 100 m thick layer with phosphorus content up to 10 % by weight. (Fig. 1). The enhanced concentration of phosphorus in this layer is related to the occurrence of rounded particles of phosphorite (20–50 mm in size) and phosphate cement in fine-grained shale and siltstone. It is noteworthy that the number of concentration peaks across the 2480−2380 m depth interval of the Gavrilov-Yam borehole is c. 15, similar to the number of phosphate-bearing layers in the Cis-Dniester region.

Acid volcanic tuffs in the Yaryshev Fm (Cis-Dniester region, Fig. 1) are considered lateral correlatives of the volcanic ash layers present in the uppermost part of the Sławatycze Fm, at the base of the Upper Neoproterozoic sequence in eastern Poland. This is situated c. 600 km northwest of the Cis-Dniester region (Vidal & Moczydłowska, Reference Vidal and Moczydłowska1995). Secondary ion mass spectrometry (SIMS) U/Pb zircon dating of the Upper Sławatycze Fm volcanic ash bed from a borehole at the Lublin slope, eastern Poland, yielded an age of 551.0 ± 4.0 Ma (Compston et al. Reference Compston, Sambridge, Reinfrank, Moczydłowska, Vidal and Claesson1995). Volcanic ash layers in the Upper Neoproterozoic sequence of the Gavrilov-Yam borehole, in the central part of the Moscow syneclise, were found in the lowermost part of the Redkino Horizon (Pletenevka and Gavrilov-Yam Fms) at a depth of 2610–2520 m. According to petrographical, geochemical and palaeontological data (Borkhvardt & Felitsyn, Reference Borkhvardt and Felitsyn1992; Felitsyn & Sochava, Reference Felitsyn and Sochava1996), the latter are considered undoubted lateral correlatives of the volcanic ash of the Ediacaran Zimnie Gory section with Ediacaran taxa occurrence (White Sea, Russian Federation, c. 1000 km north of the Gavrilov-Yam borehole), with U–Pb zircon age of 555.3 ± 0.3 Ma (Martin et al. Reference Martin, Grazhdankin, Bowring, Evans, Fedonkin and Kirschvink2000). The volcanic ash sources in the Ediacaran period were located at the southwest (for Cis-Dniester region) and northeast (for the central part of the EEP) margins of the platform (Sokolov & Fedonkin, Reference Sokolov and Fedonkin1990). Latest precise U–Pb dating for zircons from volcanic ash in the Yarishyv Fm, at the level of Ediacaran biota occurrence in the Cis-Dniester region, identifies the age of explosive volcanism as 556.78 ± 0.18 Ma (Soldatenko et al. Reference Soldatenko, El Albani, Ruzina, Fontaine, Nesterovsky, Paquette, Meunier and Ovtcharova2019).

The obtained ages of the volcanic tuffs underlying the phosphate-bearing strata in the Ediacaran sequences of the EEP suggest that the Neoproterozoic episode of phosphogenesis on the EEP is younger than 550 Ma, but older than the Early Cambrian.

An occurrence of Sabellidites cambriensis and Platysolenites antiquissimus in the Lezha Fm siliciclastic sediment of the Gavrilov-Yam borehole points to the Lower Cambrian age of this formation, namely the Vendotaenides–Sabellidites and Platysolenites zones of the Precambrian–Cambrian transition of the Baltica Plate (Strauss et al. Reference Strauss, Vidal, Moczydłowska and Pacześna1997; Felitsyn et al. Reference Felitsyn, Vidal and Moczydłowska1998). Considering the Lower–Middle Cambrian boundary at c. 500 Ma (Landing et al. Reference Landing, Geyer, Buchwaldt and Bowring2014), and Precambrian–Cambrian boundary at 543.5 Ma (Bowring et al. Reference Bowring, Grotzinger, Isachsen, Knoll, Pelechaty and Kolosov1993), or more than 2 millions years younger (Linnemann et al. Reference Linnemann, Ovtcharova, Schaltegger, Gatrner, Hautmann, Geyer, Vickers-Rich, Rich, Plessen, Hofmann, Zieger, Krause, Kriesfeld and Smith2019), the age of the Cambrian phosphorite in the central part of the Moscow syneclise falls within the 540–500 Ma interval. Therefore age estimates of 550 and 540 Ma were used for the ε Nd(t) value calculations as relating to the Ediacaran and Lower Cambrian Fe sulphide and phosphate.

3. Material and methods

P2O5 content in fine-grained siliciclastic sedimentary rocks (mudstone, clayey shale and siltstone) was used to show the distribution of phosphorus across the sequences in the Cis-Dniester region and central part of the EEP (Fig. 1). Data for the Cis-Dniester region are available via the PRECSED database in the Institute of Precambrian Geology and Geochronology, Russian Academy of Sciences. P2O5 concentration in the Gavrilov-Yam section was determined by the photometric method according to certified procedure no. 138-X NSAM RU on the photometer KFK-3-01 (Zagorsk, Russian Federation). The mean relative error of the method is less than 5 %.

Fe sulphides were separated from one statigraphic level with phosphorite nodules (Nagoryany Fm) from the Ediacaran succession in the Cis-Dniester region (drill hole no. 60 near the village of Rybnitsa, Republic of Moldova) and from three levels in the Gavrilov-Yam section. Two of them correspond to members enriched with phosphorus in the top of the Redkino Horizon and Cambrian Lezha Fm. The third relates to the black shale at the bottom of the sequence (Pletenevka Fm).

The samples were crushed down to 100 μm in an agate mortar, and then separated by hydro-gravitational methods. They were then cleaned by an electromagnet and hand-picked under a microscope to extract Fe minerals. The separated Fe sulphides are mainly spherical and oval aggregates of pyrite and a small number of marcasite, 50−100 μm in size. The prevailing size of discrete crystals is less than 5 to 7 μm (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2. SEM images of sulphide aggregates: (a) sample no. 735-86; (b) sample no. 735-93; (c) sample no. GY-15; (d) sample no. GY-22.

Composition of samples was examined before analysis by JEOL-6510LA electron microscope equipped with a JED-2200 (JEOL, Japan) spectrometer. The Fe sulphide was treated by double-distilled 11N hot (70 °C) hydrochloric acid for 3 hours to dissolve it for Nd isotopic analysis.

The diameter of phosphate nodules varies from 15 cm (sample POD-13, Nagoryany Fm) to 0.1 cm (sample GY-322Ph, Lezha Fm). The phosphorite concretions from the Cis-Dniester region consist of two components – francolite and apatite without fluorine and CO2 (so-called podolite) – according to Kopeliovich (Reference Kopeliovich1965). The phosphorite nodules from the Gavrilov-Yam section are represented by francolite only (Felitsyn & Morad, Reference Felitsyn and Morad2002).

To separate phosphate component from the phosphorite concretions the crushed samples (down to 250−500 μm size) were treated by double-distilled 8N HCl for 6 hours at 50 °C. The chemical and analytical procedure details are described in Felitsyn & Gubanov (Reference Felitsyn and Gubanov2002) and Sturesson et al. (Reference Sturesson, Popov, Holmer, Basset, Felitsyn and Belyatsky2005).

The Sm–Nd isotopic system has been analysed by a standard procedure with a multi-collector TRITON mass-spectrometer (Germany) in a static mode. A neodymium isotope fractionation was corrected against the measured 146Nd/144Nd = 0.7219 using an exponential law. The normalized ratios were adjusted to 143Nd/144Nd = 0.511860 (Tanaka et al. Reference Tanaka, Kamioka, Togashi and Dragusanu2000) of the La Jolla Nd isotope standard. The contents of Sm and Nd were determined by isotope dilution using a mixed 149Sm–150Nd spike, according to the procedure described by Mikova & Denkova (Reference Mikova and Denkova2007). A preliminarily prepared aliquot was blended with weighted amounts of mixed 149Sm–150Nd spike solution. Sm and Nd were separated for isotopic analysis in two stages. At the first stage, REEs were separated from the bulk sample using cation exchange chromatography with cation exchange resin AG® 50W-X8 (Bio-Rad, USA). The second stage included extraction chromatography using a di-(2-ethylhexyl) orthophosphoric acid (HDEHP LN-C50-A, Eichrom®, France) on Teflon carrier as a cation exchange medium. The errors of Sm and Nd concentration were 0.5 %. The Sm and Nd blanks were 10 and 20 pg, respectively. Replicate analyses of the BCR-2 standard yielded 6.57 (6.57) ppm Sm, 28.6 (28.7) ppm Nd, 147Sm/144Nd = 0.1389 ± 3 (0.1388 ± 3) and 143Nd/144Nd = 0.512627 ± 8 (0.512629 ± 8), as mean of 15 measurements. Certified values of BCR-2 are given in parentheses (values after Raczek et al. Reference Raczek, Stoll, Hofmann and Jochum2001; Jweda et al. Reference Jweda, Bolge, Class and Goldstein2015).

The obtained Nd isotopic data are represented in the traditional form of ε Nd(t) units = (143Nd/144Ndmeasured/143Nd/144NdCHUR − 1) × 104, where 143Nd/144NdCHUR = 0.512638 (isotopic composition of Nd in Chondritic − Undepleted mantle reservoir), (147Sm/144NdCHUR)0 = 0.1967, λ 147Sm = 6.54 × 10−12 yr-1, after Bouvier et al. (Reference Bouvier, Vervoort and Patchett2008).

The concentration of organic carbon in fine-grained siliciclastic rock was measured with analyser SHIMADZU TOC-L CSH (Japan), according to certified procedure no. 446-X NSAM RU.

The REE composition in Fe sulphide and phosphate nodules was determined by neutron activation analysis (instrumental technique, INAA); mean relative error was less than 6 %. Details of the procedure are presented in Felitsyn & Morad (Reference Felitsyn and Morad2002).

4. Results

Nd isotope compositions of the phosphate component of the phosphorite nodules and in the Fe sulphide from close statigraphic levels are shown in Table 1. As is shown by the data presented, the Nd isotope composition of Fe sulphide and that of the phosphate material taken from the same stratigraphic level are virtually identical: differences are within 1.0−1.5 ε Nd(t) units.

Table 1. Sm–Nd isotopic data for sedimentary phosphate and iron sulphide of the Ediacaran–Cambrian successions, East European Platform

Note: Concentrations of elements in ppm, uncertainty is quoted as 2 standard errors in the last two digits in the 143Nd/144Nd ratios.

The obtained ε Nd(t) values from the Fe sulphide and phosphate concretions clearly demonstrate a certain trend across the two successions. The ε Nd(t) values rise from the bottom of the sequence, with ε Nd(t) ranging from −17.9 to −19.4 in pyrite samples of the central part of the EEP (Gavrilov-Yam section, Pletenevka Fm) to −12.9 to −15.0 in the Fe sulphide and phosphorite from the phosphorus-enriched Redkino Horizon level (Nagoryany Fm in Cis-Dniester region and Nepeitsyno Fm in the Gavrilov-Yam section). More radiogenic Nd with ε Nd(t) from −7.9 to −9.5 was found in the Lower Cambrian. Similar values for the Earliest Cambrian (former Tommotian and Atdabanian = Meishuchuan and Qungzusian) phosphate nodules from Upper Silesia and eastern Poland have been published earlier (Felitsyn & Gubanov, Reference Felitsyn and Gubanov2002).

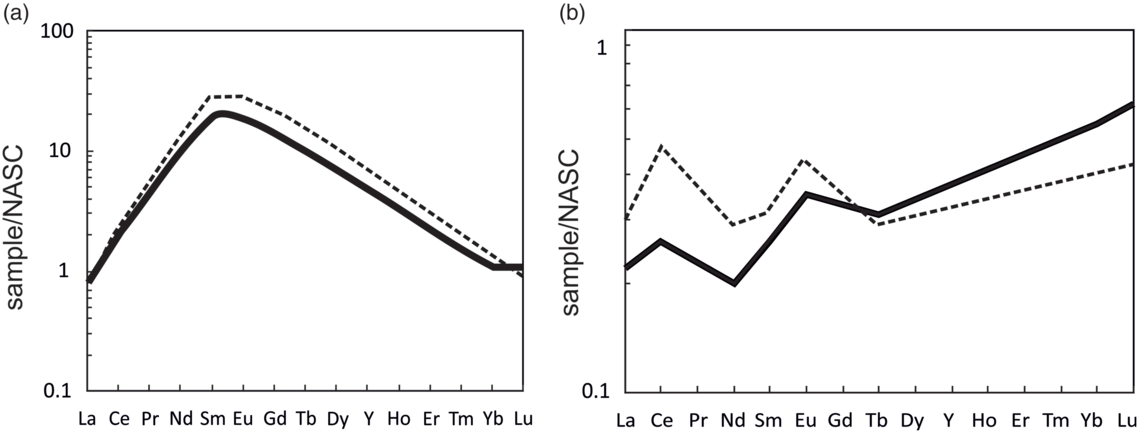

All studied samples of phosphate material display so-called bell- or hat-shaped REE distribution patterns, with significant enrichment in intermediate REE. These data were presented in Felitsyn & Morad (Reference Felitsyn and Morad2002): an average La/SmN ratio in the studied Ediacaran phosphorite is 0.05 with bulk REE content of c. 1000 ppm. The outer edge of phosphate concretion always contains significantly more intermediate REE compared to the inner part, but Nd isotope composition remains the same in both domains (Table 1). Typical REE patterns in studied samples of Fe sulphide and phosphate concretions are shown in Figure 3.

Fig. 3. Shale-normalized REE patterns (INAA data) in (a) phosphorite nodule, sample no. Pod-13 (dotted line – outer edge; solid line – internal part of nodule); and (b) pyrite aggregates (solid line – sample no. 735-93; dashed line – sample no. GY-22).

The 87Sr/86Sr ratio is 0.712806 ± 25 in the central part of the phosphate nodule (sample no. Pod-13) and 0.712789 ± 27 in the peripheral zone (S. Felitsyn, unpublished data). Layers containing sedimentary phosphate (Nagoryany Fm in Rybnitsa succession, and depth interval 2430–2370 m in Gavrilov-Yam section) are enriched with organic carbon: concentration of Corg in phosphorite-bearing strata in the Gavrilov-Yam section varies between 1.6 and 2.7 wt %, with a mean value of 2.3 wt % (n = 19), and in the Rybnitsa succession from 1.0 to 2.2 wt %, with a mean value of 1.8 wt % (n = 12). The concentration of organic carbon is 1.2 % (n = 9) in the Gavrilov-Yam section and 1.1% in the Rybnitsa section (n = 13) for argillite without phosphate concretions and phosphatic cement.

5.1. REE in phosphates and Fe sulphide

According to a common model (Reynard et al. Reference Reynard, Lécuyer and Grandjean1999; Trueman & Tuross, Reference Trueman and Tuross2002), replacement of Ca by REE in pristine apatite crystal lattice takes place at a post-depositional stage, and the proportion of REE enrichment (especially intermediate REE) depends on the extent of recrystallization. Formation of the Ediacaran phosphorite concretion from the EEP at an early diagenetic stage in a non-lithified deposit has been suggested (Kopeliovich, Reference Kopeliovich1965). REE is proposed as possibly being derived from particles of organic matter and Fe oxide during the early diagenetic geochemical processes (Haley et al. Reference Haley, Klinkhammer and McManus2004; Himmler et al. Reference Himmler, Haley, Torres, Klinkhammer, Bohrmann and Peckmann2013; Emsbo et al. Reference Emsbo, McLaughlin, Breit, du Bray and Koenig2015). The causes of REE concentration and patterns in marine phosphorites are related to organic carbon content in the depositional environments, depth of formation, Fe content in pore water and, possibly, the concurrent precipitation of other mineral phases – concentrators of REE (Haley et al. Reference Haley, Klinkhammer and McManus2004; Hein et al. Reference Hein, Koschinsky, Mikesell, Mizell, Glenn and Wood2016; Paul et al. Reference Paul, Gaye, Haeckel, Kasten and Koschinsky2018). The enhanced organic carbon content in phosphate-bearing members implies that particulate organic matter was an important source of REE phosphate material for the Ediacaran phosphorites on the EEP (Felitsyn & Morad, Reference Felitsyn and Morad2002). Two generations of apatite have been discovered in the phosphate nodules from the Cis-Dniester region (Krasilnikova et al. Reference Krasilnikova, Krasilnikova, Yudin, Golovenok and Sochava1989). The first is cryptocrystalline phosphate with fluorine (francolite), the second is presented by the product of primary apatite recrystallization: hexagonal crystals c. 100 μm across lacking fluorine, called podolite, supposedly occurred during recrystallization at an early diagenetic stage (Malinowsky, Reference Malinowsky1955). REE concentration in the apatite depends on the recrystallization extent (Reynard et al. Reference Reynard, Lécuyer and Grandjean1999), thus the REE enrichment in the nodules’ outer zone could result from a different proportion of primarily- and younger-formed phosphate minerals in inner and outer zones of the nodules. A notably similar Nd and Sr isotope composition in both zones for phosphorite concretions from the Cis-Dniester region points to the same source of REE, during formation of the phosphate nodules in the loose sediment and subsequent burial history.

The shape and size of Fe sulphide aggregate (Fig. 2) is thought to be a result of pseudomorph on the organic microfossil substrate. Substitution of organic matter by massive and framboidal pyrite was discovered in all Neoproterozoic sediments with organic matter on the EEP (Afanasieva et al. Reference Afanasieva, Burzin, Mikhailova and Kuzmenko1995). Organic fossils attributed to a formal subgroup Sphaeromorhitae (acritarchs), with predominant diameter 50–100 μm, were found in all Ediacaran successions of the EEP (Sokolov & Fedonkin, Reference Sokolov and Fedonkin1990). The first report of Fe sulphide association with organic matter in Cis-Dniesterian sequences was published by Văscăutzanu (Reference Văscăutzanu1931). The REE patterns in the studied Fe sulphide differ from the REE distribution in the phosphate nodules, displaying a pronounced enrichment with heavy REE (average La/YbN ratio is 0.42) and positive Ce and Eu anomalies. The latter is traditionally regarded as an indicator of strong anoxia in pore water in marine sediment, with pH ranging from 6 to 9 (Sverjensky, Reference Sverjensky1984). REE patterns in the studied Fe sulphide are similar to those in modern-day marine pore water, derived from organic matter with La/YbN ratio <1.0 (Haley et al. Reference Haley, Klinkhammer and McManus2004). A conventional model of an iron sulphide formation (Rickard & Luther, Reference Rickard and Luther2007 and references therein) suggests formation of an iron sulphide gel, framboids of pyrite and subsequent aggregates of pyrite crystals, often in the presence of sedimentary organic matter. Replacement of organic soft tissue by iron sulphide is a very rapid process (Scheiber, Reference Scheiber, Reiner and Tiel2011), therefore microelements adsorbed by a sulphide gel originate from pore water at the moment of iron sulphide formation. Sizes and shape of the studied sulphide (Fig. 2) are likely a result of replacement of organic-wall microorganisms (acritarchs) with iron sulphide. Elements, adsorbed at a gel phase of a pyrite formation could be present in a form of the Cottrell atmosphere alongside dislocation surfaces in newly formed crystals (e.g. Kitamura et al. Reference Kitamura, Matsuda and Morimoto1986; Reddy et al. Reference Reddy, Riessen, Saxey, Johnson, Rickard, Fougerouse, Fisher, Prosa, Rice, Reinhard, Chen and Olson2016). Incorporation of microelements geochemically analogous to Fe and S into pyrite crystalline lattice, with replacement of iron and sulphur, is a common process (Huerta-Diaz & Morse, Reference Huerta-Diaz and Morse1992). Some amounts of REE could be trapped by growing pyrite crystals, consisting of clastic particles and/or be inherited from an organic substrate.

The terminal Ediacaran and Cambrian sedimentary rocks in the Cis-Dniester and Moscow syneclise areas were not affected by any significant thermal impact and tectonic deformation, with their thermal alteration index (TAI) values ranging from 1 to 3 in organic fossils in all reference Ediacaran and Cambrian sequences of the EEP (Moczydłowska, Reference Moczydłowska1991; Felitsyn et al. Reference Felitsyn, Vidal and Moczydłowska1998). Probably, in such mild conditions, iron sulphide and phosphate nodules could retain microelements absorbed during their formation. Thus, both the studied diagenetic phosphate nodules and iron sulphide from the Ediacaran and Lower Cambrian sediments of the EEP have the same source of elements (including REE) – the pore water.

5.2. Nd isotope signature in phosphate material and Fe sulphide

The ε Nd(0) values of seawater in modern-day oceans vary between +2.7 and −26.6 and reflect the age and composition of eroded area in continents surrounding the oceanic basins (Lacan et al. Reference Lacan, Tchikawa and Jeandel2012; Bayon et al. Reference Bayon, Toucanne, Skonieczny, André, Bermell, Cheron, Dennielou, Etoubleau, Freslon, Gauchery, Germain, Jorry, Ménot, Monin, Ponzevera, Rouget, Tachikawa and Barrat2015; van de Flierdt et al. Reference van de Flierdt, Griffiths, Lambelet, Little, Stichel and Wilson2016; Tachikava et al. Reference Tachikava, Arsouze, Bayon, Bory, Colin, Dutay, Frank, Giraud, Gourlan, Jeandel, Lacan, Meynadier, Montagna, Piotrowski, Plancherel, Pucéat, Roy and Waelbroeck2017, and references therein). Looking at Nd isotope signature in Ediacaran and Cambrian Fe sulphide and phosphate as a proxy of Nd isotope composition in coeval seawater, the observed change in ε Nd(t) values across the Ediacaran–Cambrian succession on the EEP could be attributed to a secular increase of radiogenic Nd proportion in the water reservoir.

Lower Cambrian phosphate nodules and biogenic apatite of the Baltica Plate from numerous locations show ε Nd(t) from −8 to −10 (Sturesson et al. Reference Sturesson, Popov, Holmer, Basset, Felitsyn and Belyatsky2005) and, probably, water masses with more radiogenic Nd proportion were coming from the adjacent plates. According to the reconstructions of plate positions in the Early Cambrian (Golonka & Gawęda, Reference Golonka, Gawęda and Sharkov2012), the nearest neighbours to Baltica plate were the Siberia, Gondwana and Laurentia palaeocontinents. ε Nd(t) in Early Cambrian water on the Siberia Platform was −5.4 ± 1.0; in small blocks of Gondwana (Southern Kazakhstan, Silesia, Iberia, Mongolia), ε Nd(t) values in palaeobasins range from −5.9 to −7.1; whereas for Laurentia’s plates water masses display ε Nd(t) from −15.5 to −26.2 (Felitsyn & Gubanov, Reference Felitsyn and Gubanov2002). In this case it is valid to suggest intense water mass exchanges between the Baltica plate and Siberia and Gondwana at the end of the Ediacaran and Early Cambrian, rather than with the Laurentia supercontinent. Noteworthy is the absence of major Early Cambrian phosphorite deposits in areas of Laurentia adjacent to Baltica, whereas Ediacaran and Cambrian phosphorites are located on Gondwanan blocks (Cook & Shergold, Reference Cook and Shergold1984).

The onlap of water masses (probably enriched with element-nutrients) at the time of phosphate deposition has been accompanied by the emergence of low-oxygen facies in the lower part of the water column. This supports the enhanced content of organic carbon in phosphate-bearing beds.

The alternative explanation of the ε Nd(t) shift in diagenetic phosphate and sulphide across the Ediacaran–Cambrian successions on the EEP could be related to diminution of intraplatform source for clastic material input, owing to wide Early Cambrian transgression. At the end of the Ediacaran, the area and depth of basins over the EEP had declined. Numerous gaps and interbedding of sand and siltstone are typical for the top of the Kotlin Horizon; Early Cambrian sedimentary rocks on the EEP are presented mainly by clay, and sedimentation took place in relatively deep palaeobasins. (Sochava et al. Reference Sochava, Korenchuk, Pirrus and Felitsyn1992). In this case, a certain proportion of sources for clastic material (old basement uplands) were covered by water, and their influence on Nd isotope composition in coeval water decreased.

The similarity of Nd isotope composition in the diagenetic phosphate nodules and iron sulphide from the same statigraphic level suggests the same source of REE in the diagenetic phosphate and sulphide, namely coeval pore water. Concentration of Sm and Nd incorporated into the iron sulphide is sufficient for a confident determination of Nd isotope composition, thus a diagenetic pyrite may be regarded as a suitable substrate to determine an Nd isotope composition in an ancient aquatic facies: likewise Fe oxyhydroxide for the same purpose (Charbonnier et al. Reference Charbonnier, Pucéat, Bayon, Desmares, Dera, Durlet, Deconinck, Amédro, Gourlan, Pellenard and Bomou2012).

6. Conclusions

Two episodes of phosphogenesis are recorded in the Ediacaran and Lower Cambrian siliciclastic sediment on the EEP. The first of them occurred somewhat later than 550 Ma and resulted in deposition of 10–15 layers enriched with phosphorus, while the second one (Cambrian) is poorly represented on the EEP. The Nd isotope composition in the phosphate nodules and iron sulphide from the same layer display similar values of ε Nd(t). This allows usage of diagenetic pyrite for determination of Nd isotope signature in ancient marine facies. The distribution of ε Nd(t) values in the phosphate and sulphide across the Ediacaran – Lower Cambrian sequence of the EEP is in full compliance with the geological history of the platform and secular change of a source area age. The basal Neoproterozoic sediment in the central part of the EEP was deposited in a shallow anoxic epeiric basin, and the source of clastic material was the basement older than 2.0 Ga. Diagenetic iron sulphide from this level displays ε Nd(t) values between −17.9 and −19.4. The phosphate precipitation occurred during wide transgression: both diagenetic phosphate and sulphide from the layer enriched with phosphorus show ε Nd(t) ranging from −12.3 to −15.0, while the same Cambrian mineral phases have ε Nd(t) c. −8.0. The progressive increase of radiogenic Nd proportion in authigenic phosphate and sulphide throughout the Neoproterozoic and Cambrian indicates a secular change in Nd isotope composition of the water reservoir on the EEP. Such a trend could be caused by changes in the contribution of Proterozoic rocks in the source area and/or water masses onlap from palaeobasins containing more radiogenic Nd.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by Research project no. 0153-2019-0001, Institute of Precambrian Geology and Geochronology, Russian Academy of Sciences. The authors thank E. Landing and the anonymous reviewers for providing constructive critical reviews.