1. Introduction

Silicic magmatism may occur to a greater or lesser extent, both temporally and spatially, in association with predominantly basaltic Large Igneous Provinces (Bryan et al. Reference Bryan, Riley, Jerram, Stephens, Leat, Menzies, Klemperer, Ebinger and Baker2002). The Lower Cretaceous Paraná–Etendeka province of Brazil and Namibia is perhaps the clearest case of temporal and spatial overlap (Peate, Reference Peate, Mahoney and Coffin1997; Marsh et al. Reference Marsh, Ewart, Milner, Duncan and Miller2001), with a clear connection between silicic and basaltic magmatism. Similarly, the Lower Jurassic Karoo province of South Africa (Cox, Reference Cox and Macdougall1988; Marsh et al. Reference Marsh, Hooper, Rehacek, Duncan, Duncan, Mahoney and Coffin1997; Svensen et al. Reference Svensen, Corfu, Polteau, Hammer and Planke2012) includes large-volume rhyolitic rocks of the Lebombo belt (Cleverly, Betton & Bristow, Reference Cleverly, Betton, Bristow and Erlank1984; Sell et al. Reference Sell, Ovtcharova, Guex, Bartolini, Jourdan, Spangenberg, Vicente and Schaltegger2014). The Karoo province is also contemporaneous with, but widely separated from, the oldest phase (Marifil Formation) of the silicic Chon Aike province of Patagonia (Pankhurst et al. Reference Pankhurst, Leat, Srugo, Rapela, Márquez, Storey and Riley1998 a); nevertheless, it has been argued that the Early Jurassic silicic magmatism might be attributable to the same break-up process (Pankhurst et al. Reference Pankhurst, Riley, Fanning and Kelley2000; Storey, Leat & Ferris, Reference Storey, Leat, Ferris, Ernst and Buchan2001). The Columbia River Basalt province (Reidel et al. Reference Reidel, Camp, Ross, Wolff, Martin, Tolan, Wells, Reidel, Camp, Ross, Wolff, Martin, Tolan and Wells2013) and the Miocene phases of the Cascade volcanism (Christiansen & Yeats, Reference Christiansen, Yeats, Burchfiel, Lipman and Zoback1992) are another example of contemporaneity but with spatial separation of magmatism; a complex relationship between the two has been inferred by Gao et al. (Reference Gao, Humphreys, Yao and van der Hilst2011).

A possible example exists in Antarctica. Eruption of the Kirkpatrick Basalt of the Lower Jurassic Ferrar Large Igneous Province (LIP) was preceded by, and to a minor extent was accompanied by, silicic magmatism (Elliot & Larsen, Reference Elliot, Larsen, Findlay, Unrug, Banks and Veevers1993; Elliot et al. Reference Elliot, Fleming, Foland, Fanning, Cooper and Raymond2007). The objectives of this study are to: (1) document the silicic magmatism, which is recorded primarily in the Hanson Formation strata in the central Transantarctic Mountains; (2) provide age constraints on the magmatism; (3) evaluate the stratigraphic record and tectonic setting of the Hanson Formation; and (4) investigate relationships of the Early Jurassic silicic magmatism of the Transantarctic Mountains to the Gondwana plate margin and Gondwana break-up.

2. Regional geology

The Transantarctic Mountains (Fig. 1) comprise a pre-Devonian basement overlain by the late Palaeozoic – early Mesozoic Gondwana sequence, which is capped by Lower Jurassic sedimentary and volcanic strata. The oldest rocks, gneisses and schists that crop out in a limited area at and near the Miller Range (Fig. 1), are Mesoproterozoic, but have Archaean precursors (Goodge, Fanning & Bennett, Reference Goodge, Fanning and Bennet2001; Goodge & Fanning, Reference Goodge, Fanning, Gamble, Skinner and Henrys2002). The basement is predominantly an assemblage of igneous, metamorphic, metavolcanic and metasedimentary rocks, which was involved in the late Neoproterozoic – Cambrian Ross Orogen (Goodge et al. Reference Goodge, Myrow, Williams and Bowring2002, Reference Goodge, Fanning, Norman and Bennett2012; summarized in Elliot, Reference Elliot, Hambrey, Barker, Barrett, Bowman, Davies, Smellie and Tranter2013). The Kukri Erosion Surface (Isbell, Reference Isbell1999), developed on basement rocks, is the defining contact in the Transantarctic Mountains. It is overlain by the Beacon Supergroup (Barrett, Elliot & Lindsay, Reference Barrett, Elliot, Lindsay, Turner and Splettstoesser1986; Barrett, Reference Barrett and Tingey1991), which consists of the Taylor Group of Devonian age and the Permian–Triassic Victoria Group (Fig. 2). The Upper Triassic strata are locally overlain by Lower Jurassic sandstones and silicic tuffaceous rocks, which are succeeded by basaltic pyroclastic rocks and then the Kirkpatrick flood basalts (Elliot & Fleming, Reference Elliot and Fleming2008; Schöner et al. Reference Schöner, Viereck-Götte, Scheidner, Bomfleur, Cooper and Raymond2007). Correlative Ferrar Dolerite sills and dykes are widespread in the Beacon strata and are sparsely distributed in the pre-Devonian basement (Elliot & Fleming, Reference Elliot and Fleming2004).

Figure 1. Location map for Antarctica. Illustrated distribution of the Lower Jurassic volcanic rocks includes both the Hanson Formation and the overlying Ferrar extrusive rocks. Stretched continental crust underlies the Ross Sea, Ross Ice Shelf and West Antarctica (the Ross embayment) through to Ellsworth Land, and was generated during Late Cretaceous – late Cenozoic time. Stretched continental crust also underlies the Filchner–Ronne Ice Shelf region and the adjacent Weddell Sea (the Weddell embayment), but was extended during the Early–Middle Jurassic break-up of Gondwana.

Figure 2. Simplified geologic columns for Devonian – Lower Jurassic strata in the Transantarctic Mountains.

In the central Transantarctic Mountains, where the Hanson Formation crops out, the Victoria Group is approximately 2500 m thick (Fig. 2; Collinson et al. Reference Collinson, Elliot, Isbell, Miller, Veevers and Powell1994). Permian glacial beds (Pagoda Formation) are succeeded by post-glacial shales and fine sandstones (Mackellar Formation), a deltaic sequence (Fairchild Formation) and then Permian coal measures (Buckley Formation). The overlying Triassic Fremouw and Falla formations are mainly non-carbonaceous fluvial deposits. Only in the Marshall Mountains is the contact with the Jurassic Hanson Formation exposed.

Barrett, Elliot & Lindsay (Reference Barrett, Elliot, Lindsay, Turner and Splettstoesser1986) and Barrett (Reference Barrett and Tingey1991) established the first detailed stratigraphy of the central Transantarctic Mountains, including the silicic tuffaceous rocks forming the upper part of Barrett's Falla Formation. Reinvestigation of those rocks (D. Larsen, unpublished M.Sc. Thesis, Ohio State University, 1988; Elliot & Larsen, Reference Elliot, Larsen, Findlay, Unrug, Banks and Veevers1993; Elliot, Reference Elliot2000) led to the tuffaceous rocks being assigned to a separate unit named the Hanson Formation (Elliot, Reference Elliot1996).

3. Hanson Formation

3.a. Distribution

Rocks assigned to the Hanson Formation crop out principally in the Marshall Mountains, southern Queen Alexandra Range (Fig. 3), and to a very limited extent as poorly exposed strata at the Otway Massif, 100 km to the south (Fig. 4). The greatest thicknesses and best-exposed strata are present at Mount Kirkpatrick and Mount Falla (Fig. 3). At the type section at Mount Falla the Hanson Formation was divided into three informal members (Elliot & Larsen, Reference Elliot, Larsen, Findlay, Unrug, Banks and Veevers1993; Elliot, Reference Elliot1996; Elliot, Reference Elliot2000) with a thickness of c. 237.5 m. Elsewhere in the Marshall Mountains the Hanson Formation is thinner and less well exposed, its lower contact is covered and stratigraphic thicknesses are uncertain. On the east face of Mount Marshall it is possible that a true thickness for the Hanson Formation can be measured; it is probably less than at Mounts Kirkpatrick and Falla. At Golden Cap the Hanson beds (forming the top c. 20 m at the summit) are disturbed and tilted by irregular and inclined dolerite intrusions. Exposures are very limited on Otway Massif where contacts are not exposed as a result of surficial debris, and the minimum thickness for the Hanson Formation is only 55 m.

Figure 3. Geologic sketch map of the Marshall Mountains, central Transantarctic Mountains. Numbers (e.g. 85-2) designate the locations of measured stratigraphic columns illustrated on Figure 5. Single numbers (e.g. 79) designate locations of stratigraphic columns not illustrated on Figure 5. Note: orientation is with north up (reverse of Fig. 1).

Figure 4. Geologic sketch map of the Otway Massif, central Transantarctic Mountains. Note: orientation is with north up.

Some basaltic tuff-breccias of the Prebble Formation at the Otway Massif enclose silicic tuff clasts (Elliot et al. Reference Elliot, Fleming, Foland, Fanning, Cooper and Raymond2007). Silicic glass shards are present in a thin bed at the base of the Kirkpatrick Basalt (Elliot, Reference Elliot2000) and in some sedimentary interbeds within the basalt sequence (Elliot, Bigham & Jones, Reference Elliot, Bigham, Jones, Ulbrich and Rocha Campos1991).

3.b. Age and geochronology

The age of the Hanson Formation has been established by the palynology of the underlying Upper Triassic Falla Formation (Farabee, Taylor & Taylor, Reference Farabee, Taylor and Taylor1989) and by vertebrate palaeontology of the Hanson Formation (Hammer & Hickerson, Reference Hammer and Hickerson1996), which suggested an Early Jurassic age or, more precisely, a Sinemurian–Pliensbachian age, and by radiometric age determinations on the Hanson Formation and the Kirkpatrick Basalt. An early Rb–Sr six-point isochron for the tuffs yielded an age of 186±8 Ma (Faure & Hill, Reference Faure and Hill1973). Recent single-crystal zircon U–Pb analysis of Ferrar Dolerite sills and Kirkpatrick Basalt lavas has demonstrated an age of 182.78±0.03 Ma to 182.43±0.04 Ma for the Ferrar LIP (Burgess et al. Reference Burgess, Bowring, Fleming and Elliot2015).

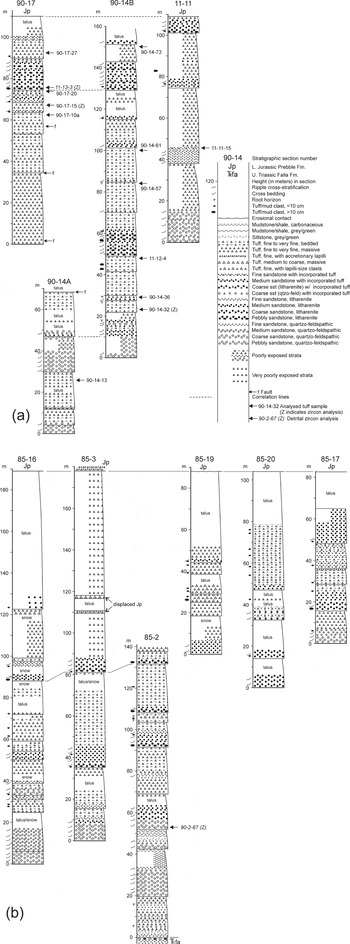

Zircons from two sandstone and two tuffs have been analysed in this study. Detrital zircons have been extracted from a quartzo-feldspathic sandstone (90-2-67) that crops out in the lower member of the Hanson Formation at the type section and from a litharenite (11-11-3) from the upper member. The locations are given in the stratigraphic columns (Fig. 5). Two tuffs were selected for analysis, one low in Section 90-14 at Mount Kirkpatrick and the other high in Section 90-17 and near the contact with the Prebble Formation; locations for both are indicated on Figure 5. Both samples were selected on the basis of field data and microscopic examination that indicated least disturbance and alteration; the choice is limited because tuffs commonly show signs of reworking (the presence of low-angle cross-bedding and/or outsize muscovite flakes). Petrographic descriptions are provided in the online Supplementary Material (available at http://journals.cambridge.org/geo).

Figure 5. Stratigraphic columns for the Hanson Formation. See Figure 3 for locations of stratigraphic sections. (a) Sections measured on Mount Kirkpatrick. (b) Sections measured on Mount Falla and at other localities in the Marshall Mountains. In the legend, ‘incorporated tuff’ refers to layers and lenses of tuff incorporated by reworking (see Section 3.e). Sections designated by single numbers on Figure 3 are incomplete (lower or upper contact not exposed and/or strata poorly exposed). Minimum thicknesses for sections located in Figure 3 but not illustrated in Figure 5: sections 39 (c. 86 m), 78 (c. 100 m), 79 (c. 212.5 m) and 81 (c. 80 m), 83 (c. 90 m); and sections 85-13 (60 m), 85-17 (87 m), 85-19 (90 m) and 85-20 (105 m).

3.b.1. Methods

Zircon grains were separated from total rock samples using standard crushing, washing and heavy liquid (Sp. Gr. 2.96 and 3.3) and paramagnetic mineral separation procedures. The zircon-rich heavy mineral concentrates were poured onto double-sided tape, mounted in epoxy together with chips of the Temora reference zircon, sectioned approximately in half and polished. Reflected and transmitted light photomicrographs were prepared for all zircons, as were cathodoluminescence (CL) scanning electron microscope (SEM) images. These CL images were used to decipher the internal structures of the sectioned grains and to ensure that the c. 20 μm SHRIMP spot was wholly within a single age component zone within the sectioned grains.

The U–Th–Pb analyses were conducted using SHRIMP RG at the Research School of Earth Sciences, The Australian National University, Canberra, Australia following procedures given in Williams (Reference Williams1998). Each analysis consisted of four scans through the mass range, with Temora reference zircon grains analysed for every five unknown analyses. The data were reduced using the SQUID Excel Macro of Ludwig (Reference Ludwig2001). The 206Pb/238U ratios were normalized relative to a value of 0.0668 for the Temora reference zircon, equivalent to an age of 417 Ma (see Black et al. Reference Black, Kamo, Allen, Aleinikoff, Davis, Korsch and Foudoulis2003). Uncertainty in the reference zircon calibration for each analytical session is given in the table footnotes for each sample (online Supplementary Tables S1–S4, available at http://journals.cambridge.org/geo). Uncertainties given for individual analyses (ratios and ages) are at the one-sigma level.

Correction for common Pb was made either using the measured 204Pb/206Pb ratio in the normal manner or, for grains younger than c. 800 Ma (or those low in U and radiogenic Pb), the 207Pb correction method was used (see Williams, Reference Williams1998). When the 207Pb correction is applied it is not possible to determine radiogenic 207Pb/206Pb ratios or ages. In general, for grains younger than 800 Ma (and for areas that are low in U and therefore radiogenic Pb) the radiogenic 206Pb/238U age has been used for the probability density plots. The 207Pb/206Pb age is used for grains older than c. 800 Ma or for those enriched in U. Tera & Wasserburg (Reference Tera and Wasserburg1972) concordia plots, probability density plots with stacked histograms and weighted mean 206Pb/238U age calculations were obtained using ISOPLOT/EX (Ludwig, Reference Ludwig2003).

3.b.2. Results

3.b.2.a. Quartzo-feldspathic sandstone sample 90-2-67

Detrital zircon grains form a heterogenous population, with many round to sub-round grains and others broken fragments of euhedral crystals. A wide variety of internal CL characteristics are present, ranging from oscillatory zoned igneous features to homogeneous metamorphic zircon. The majority of the grains record ages in the range 480–590 Ma with tailing off on the older age side towards 680 Ma, and a subsidiary cluster of Grenville ages at c. 1050 Ma (Fig. 6). The main cluster is broad and irregular with a prominent group at c. 530 Ma and lesser groupings at c. 495 Ma, c. 565 Ma and c. 580 Ma. These are all in the range attributed to the late Neoproterozoic – Early Ordovician Ross Orogen (Goodge et al. Reference Goodge, Fanning, Norman and Bennett2012). A scattering of grains in the range c. 230–175 Ma suggests the possible presence of a Late Triassic – Early Jurassic magmatic source. Overall, the majority of analysed grains are typical of the Gondwana margin signature (Ireland et al. Reference Ireland, Flötmann, Fanning, Gibson and Preiss1998).

Figure 6. U–Pb zircon age-probability density plot and CL image for Hanson sandstone sample 90-2-67.

3.b.2.b. Litharenite sample 11-13-3

The detrital zircon age spectrum shows a major Ross-aged component with the principal peak at c. 525 Ma and a subsidiary older peak at c. 565 Ma (Fig. 7). The other significant cluster has a probability peak at c. 195 Ma (a weighted mean age of 194.2±1.9 Ma) and a minor sub-grouping at c. 220 Ma; the three youngest grains have a weighted mean 206Pb/238U age of 185±3 Ma. There is also a scattering of Neoproterozoic and Grenville-aged grains, and four grains are scattered over the range 3.5–1.7 Ga. The three youngest grains are attributed to contemporaneous airfall deposition, and give an age consistent with the younger tuff bed (90-17-15: see Section 3.b.2.d). The older Jurassic grains were probably reworked from pre-existing Hanson strata and the Triassic grains by reworking of stratigraphically older beds.

Figure 7. U–Pb zircon age-probability density plot and CL image for Hanson sandstone sample 11-13-3.

3.b.2.c. Tuffaceous sample 90-14-32

Many of the zircon grains are elongate and prismatic, although some are broken, and CL images show oscillatory and length parallel zoning. These characteristics are typical of zircon crystallization in magmas in volcanic or subvolcanic settings. Three grains gave Ross ages (527–520 Ma) and three gave Grenville ages (1160–1025 Ma). The weighted mean 206Pb/238U age for the remaining 14 grains is 194.8±1.9 Ma (MSWD = 1.4), although the youngest 12 grains form a tight cluster with a weighted mean age of 194.0±1.6 Ma (MSWD = 0.33) (Fig. 8). Clearly these zoned igneous zircons document Early Jurassic volcanism, and provide a numerical age for that tuffaceous bed. The pre-Jurassic grains tend to be broken and/or sub-round in shape. These grains were either incorporated by surface reworking or were derived from sedimentary rocks carrying the Gondwana-margin detrital-zircon signature during the eruptive process (discussed in Section 3.f).

Figure 8. U–Pb zircon weighted mean 206Pb/238U age plot and CL image for Hanson tuffaceous sample 90-14-32. External uncertainties are included in the age calculation.

3.b.2.d. Tuffaceous sample 90-17-15

This sample contains a mixture of euhedral, occasionally elongate, zircon grains, and those that are sub-round and broken fragments. The former are typical of a volcanic and subvolcanic origin, whereas the latter are probably detrital. Eleven grains forming the dominant cluster yield a weighted mean 206Pb/238U age of 186.2±1.7 Ma (MSWD = 0.43) (Fig. 9) which is interpreted as indicating contemporaneous volcanism, giving a numerical age for that tuffaceous bed. The remaining grains are mainly of Ross Orogen age (575–475 Ma), and have an origin similar to that for the older grains in sample 90-14-32 (Section 3.b.2.c).

Figure 9. U–Pb zircon weighted mean 206Pb/238U age and CL image for Hanson tuffaceous sample 90-17-15. External uncertainties are included in the age calculation.

3.c. Contact relations

The lower contact of the Hanson sequence with the Triassic Falla Formation has been observed only at Mount Falla at the type section (section 85-2, Fig. 5). The uppermost Falla quartzose sandstone is overlain by a thin and discontinuous pebble conglomerate with clasts as large as 10 cm across; the clast compositions include fine-grained volcanic rocks, sandstones and quartz (Barrett, Elliot & Lindsay, Reference Barrett, Elliot, Lindsay, Turner and Splettstoesser1986). The pebble bed is overlain by 3 m of sandstone similar to that below the pebble bed, but lacks sedimentary structures consistent with the pebble sizes, and then passes to greenish-grey sandstones of the lowermost Hanson Formation. The pebble horizon represents a lag conglomerate and therefore a break in deposition, here interpreted as a disconformity. The 3 m thick quartzose sandstone above the pebble bed is therefore considered to be reworked Falla strata. The Falla–Hanson contact is now placed at the base of the lag conglomerate rather than the change in colour and lowest presence of significant primary volcanic material, which had previously been the basis for the lower contact (D. Larsen, unpub. M.Sc. thesis, Ohio State University, 1988; Elliot & Larsen, Reference Elliot, Larsen, Findlay, Unrug, Banks and Veevers1993). Additionally, slight changes in the thicknesses are now proposed (Section 3.d). The upper contact with basaltic pyroclastic rocks of the Prebble Formation is fully exposed only on Mount Kirkpatrick (sections 11-11 and 90-17; Fig. 5); at many sections the uppermost Hanson beds are not exposed, and the contact is placed at the incoming of coarse pyroclastic rocks of the Prebble Formation. Neither the lower nor the upper contact is exposed on the Otway Massif, where Hanson beds have very limited distribution (Fig. 4).

3.d. Stratigraphy

At the type section on Mount Falla (Elliot, Reference Elliot1996) a threefold subdivision of the Hanson Formation was proposed (Elliot & Larsen, Reference Elliot, Larsen, Findlay, Unrug, Banks and Veevers1993); however, more recent analysis does not support regional application of these subdivisions. The threefold division entailed a lower member consisting of a quartzose sandstone-tuffaceous sandstone unit, 65.5 m thick, which in its lower part contains numerous strikingly green beds: a middle member of ledge-forming tuff interbedded with volcaniclastic sandstone, 65.5 m thick, and an upper member of slope-forming weakly lithified tuff, 106.5 m thick (total of 237.5 m). The stratigraphy and correlations have been revised based on the reassessment of the lower contact and more detailed regional observations (Fig. 5). The thickness of the lower member (section 85-2) is increased (to 68.5 m) by 3 m of quartzose sandstone formerly assigned to the Falla Formation; the middle member (section 85-2) is 66.5 m thick, terminating at the onset of tuff deposition above the highest volcaniclastic sandstone; and the upper member (section 85-3) begins immediately above the highest volcaniclastic sandstone and terminates at the base of the Prebble Formation (99.5 m; total 234.5 m). The correlation between sections 85-2 and 85-3, which can also be followed on air photographs, is illustrated in Figure 5. This subdivision at the type section can be partly traced across the northern flank of Mount Falla (sections 85-3 to 85-16; Fig. 5), but the only subdivision elsewhere is into a lower mixed sandstone-tuff sequence and an upper predominantly tuff sequence; the threefold subdivision is therefore abandoned here.

The sections measured on the northwestern face of Mount Kirkpatrick (sections 90-14, 90-17) are neither complete nor continuous, although a composite section has been pieced together and provides an estimated minimum thickness of 202 m (Fig. 5). The lower contact has not been identified, because neither the lag conglomerate at the Falla-Hanson contact at the type section (section 85-2, Fig. 5) nor the lower green sandstone-tuff interval is exposed or present. In addition, faulting parallel to the outcrop face and talus cover introduces further uncertainties. Correlations can be made between the composite section and that measured originally at approximately the same location (Barrett, Elliot & Lindsay, Reference Barrett, Elliot, Lindsay, Turner and Splettstoesser1986). In Barrett's section KO (which was measured adjacent to sections 90-14 and 90-17 and similarly included lateral offsets) the lowest tuff, which is overlain by a garnet-rich sandstone, is here taken as the contact with what is now the Hanson Formation, and on his stratigraphic column gives a thickness of 224 m. The restricted Falla Formation (Elliot, Reference Elliot1996) at section KO is only 58 m thick, a drastic reduction from the 300 m thick Falla at the type section at Mount Falla approximately 15 km to the WSW. On the west face of Mount Kirkpatrick the upper tuff member (section 11-11; Fig. 5) is well exposed and is in contact with Prebble beds, but underlying strata are faulted (parallel to outcrop) and not well exposed. The thick quartz-rich pebbly sandstone forming the lowest 16 m of section 11-11 has conspicuous garnet concentrations, as in the quartzose sandstones in sections 85-2 and 90-14, and it is possible that tuff beds are present but covered in the underlying sequence. The sections (c. 90 m of strata) immediately across the fault and downslope (of section 11-11) are carbonaceous and fluvial, and therefore assigned to the Falla Formation.

Hanson Formation beds crop out below the Prebble Formation in much of the Marshall Mountains. Exposed sections are dominated by tuffs which overlie mixed sandstone-tuff beds (Fig. 5). The greatest measured thickness is 212 m (station 39), although that section is poorly exposed; other sections have lesser thicknesses. Nowhere has the lower contact been observed. On the Otway Massif the thickest section (55 m; section 85-13, Fig. 4) consists of interbedded sandstone and tuff and two very short sections on the NE flank are tuffaceous, one of which is associated with garnet-rich arkose carrying 2 cm angular K-feldspar grains. None of these is in stratigraphic contact with other formations.

Because the lower two members at the type section cannot be separately identified elsewhere, the stratigraphy is here described and illustrated in Figure 5 in terms of (1) two generalized members: a lower quartzose and volcaniclastic sandstone-tuff sequence and an upper sequence of tuff with minor sandstone; and (2) four principal petrofacies (see Section 3.e for details). The lower member includes light-coloured quartzo-feldspathic sandstones and darker (faintly green to pale purple) litharenites higher in the member. These beds rest on erosion surfaces cut into underlying tuffs or tuffaceous beds and comprise cross-bedded multi-story bedsets as much as 12 m thick, with cross-bed sets as much as 2 m thick. Some of these sandstones are laterally continuous for hundreds of metres at Mount Falla and the west face of Mount Kirkpatrick, and at Mount Falla are observed to thin and wedge out. The pebbly coarse- to medium-grained quartzose sandstones are observed mainly low in the member and include some beds that are arkosic with angular K-feldspar pebbles as much as 2 cm long (e.g. 90-2-67). Mud or tuff clasts as much as 25 cm long are also prominent at the base of, and within, these sandstones. Many of the quartzo-feldspathic sandstones are conspicuous in the field for the presence of red garnet grains. In the lower member the pebbly quartzose sandstones grade up into finer-grained quartzo-feldspathic sandstones or litharenites, some displaying ripple cross-stratification, and then into overbank deposits, which are mainly grey non-carbonaceous and black carbonaceous shale. The litharenites higher in the section also are medium to coarse grained, and a few have scattered thin quartz-rich lenses. The highest litharenite beds at Mount Kirkpatrick include pebbles as much as 2.5 cm across and composed of abundant friable pale tuffaceous clasts as well as lesser amounts of dense silicic to intermediate volcanic rock fragments, ignimbrite, vein quartz, quartzose sandstone, jasper and carbonate. Some beds enclose tuff clasts as much as 38 cm long. The litharenites commonly grade quite abruptly into tuffaceous beds.

Tuffaceous strata vary from thin discrete ashfall tuff beds as thin as 10 cm to massive beds several metres thick. Many tuff beds are laminated to thinly bedded, some exhibit sweeping low-angle cross-bedding, and a few show graded bedding. Others with pale pink to pinkish-grey colours are blocky and structureless. All tuff sequences, even those only a few tens of centimetres thick, exhibit an alternation of bedding characteristics, including colour variation (pale green, yellow and pale grey). The upper parts of several tuff intervals exhibit root structures indicating incipient palaeosol formation, which accounts for their lack of internal bedding and almost complete lack of glass shards (see Section 3.e). Tridymite has been identified in some of the root structures. In general, although the blocky weathering tuffs appear unmodified, many exhibit evidence for reworking as demonstrated by the presence of muscovite flakes (commonly much larger than accompanying biotite).

At the type section (section 85-3) the upper member is entirely tuffaceous but talus leads to very poor exposure. However, accretionary lapilli are present in two metre-thick intervals (at 110 m and 117 m), and armoured lapilli are observed in association with the accretionary lapilli in the lower interval. The cores of the armoured lapilli in the lower interval consist of scoriaceous clasts (as large as 5.5 cm across) with ragged ends, comparable to basaltic scoria clasts seen elsewhere only in the overlying Prebble Formation; these clasts are unique with respect to all other tuffs in the Hanson Formation. The coarse lithic-rich tuff at 117 m in section 85-3 lacks silicic shards and includes strongly altered scoria-like particles with ragged outlines. The uppermost interval (178–180 m) consists of very poorly sorted reworked medium-grained tuff, which contains concentrations of accretionary lapilli and scoria-like clasts. This upper interval is reassigned to the Prebble Formation. The beds lower in the section are unlike any at similar stratigraphic levels in the Hanson Formation and are therefore unlikely to be in situ; they are regarded as displaced Prebble strata. The equivalent strata at section 85-16 are no better exposed. On Mount Kirkpatrick the upper tuff member has interspersed quartzose sandstone and volcanic litharenite bedsets, which are up to 15 m thick. Several of these sandstone beds are of mixed composition, resulting from fluvial processes incorporating weakly consolidated clasts of tuffaceous material by bank erosion. Beds may also have formed by simple stream-bank slumping of tuffaceous deposits, which is the case for the principal vertebrate bone-bearing bed (42–48 m in Section 90-14B; Fig. 5) (Krissek et al. Reference Krissek, Horner, Elliot, Collinson, Yoshida, Kaminuma and Shiraishi1992).

Hanson strata elsewhere in the Marshall Mountains are sandstone-tuff sequences (Fig. 5). In almost all sections coarse arkosic sandstones are present as well as quartzo-feldspathic and volcanic sandstones (litharenites); tuff commonly forms the uppermost 10–20 m. Section 78 is notable for the presence in the upper part of the section of coarse bubblewall and tricuspate shards, and pumiceous fragments as large as 1.5 cm across (far larger than shards and pumice observed elsewhere in medium-grained sandstones). Accretionary lapilli are observed in section 85-17 and in the upper parts of poorly exposed sections 39 and 78. The general absence of accretionary lapilli is attributed to the common reworking of the tuffs, although lack of exposure may be a contributing factor.

3.e. Petrofacies

3.e.1. Tuff

Tuffs are very fine grained (>0.125 mm) to fine grained (>0.25 mm), but in rare instances are medium grained (>0.5 mm). Mineral grains are observed in minor to trace amounts and consist principally of quartz, with subordinate to trace amounts of feldspar (mainly sodic plagioclase and rare sanidine) and biotite. The presence of elongate muscovite in many tuffs suggests incorporation of a non-volcanic component by fluvial or aeolian processes. Bubble wall shards are common, and lesser to trace amounts of tricuspate shards occur in most tuffs; in many instances they are observed as ghost outlines seen only under polarized light. Some fine-grained rocks with the microscopic characteristics of the tuffs lack shards. This is the case in the lower green beds (3–16 m) at the type section, where shards are observed only in one sample. Compressed pumice fragments are present sparingly, and accretionary lapilli are rare. The background matrix material is siliceous and is commonly accompanied by colourless to pale brown phyllosilicate shreds in varying amounts.

3.e.2. Quartzo-feldspathic sandstone

These sandstones range in grain size from fine- to very coarse grained and pebbly; most of the sandstones are moderately well sorted. Grains are commonly sub-angular to sub-round, although the coarse sandstones and pebbly sandstones may contain well-rounded grains. A few sandstones are classified as pebbly arkoses in which K-feldspar is present in equal or greater amounts than plagioclase, and feldspar grains are angular and as large as 2 cm across. Quartz, the dominant mineral grain, is normally undulose, but a small proportion of the grains is polycrystalline and consists of several subgrains. Rare quartz grains contain acicular inclusions. Plagioclase, subordinate to quartz, has compositions in the andesine-oligoclase range. K-feldspar, which is subordinate to plagioclase except in arkosic sandstones, includes orthoclase, microcline and perthite. Biotite and lesser muscovite are subordinate minerals. Heavy minerals include garnet, which is conspicuous in hand samples of some sandstones, zircon, amphibole, titanite and epidote. Schistose metamorphic rock fragments, consisting of quartz and oriented micas, are observed sparingly as are clasts of metamorphic quartz (aggregates of small unstrained or lightly strained grains). Quartz-feldspar granitic fragments are similarly rare. Volcanic rock fragments (described under the litharenites) are present in trace to very minor amounts. The cements include silica minerals, phyllosilicate, sparse zeolite and irresolvable material.

3.e.3. Litharenite

Litharenites are distinguished from quartzo-feldspathic sandstones by the presence of moderate to significant amounts of volcanic rock fragments. These have the same range in grain size as the quartzo-feldspathic sandstones and again are moderately well sorted; quartz is the dominant mineral grain and has similar characteristics. Feldspars are less common and K-feldspar is rare. Biotite and muscovite form a minor component. Heavy minerals are commonly dominated by epidote, but garnet and zircon are also present. Volcanic rock fragments are quite varied and include: feldspar aggregates with trachytic or pilotaxitic textures; microcrystalline siliceous grains; similar microcrystalline grains with microphenocrysts of feldspar and/or quartz; grains showing spherulitic devitrification; and grains with the appearance of silicified and compressed ash-flow tuff or flow-banded rhyolite. Some of the trachytic-textured rock fragments have feldspar laths set in alkali feldspar, and clearly have alkaline composition. Less commonly, fine-grained tuff clasts are present and reflect reworking from near-contemporaneous tuffaceous beds. Cements include carbonate, zeolite, phyllosilicate in microscopic shreds, quartz and very-low-refractive-index opaline silica; zeolites include clinoptilolite and analcime (identified by x-ray diffraction: Barrett, Reference Barrett1969; D. Larsen, unpub. M.Sc. thesis, Ohio State University, 1988), and possible natrolite and stilbite. Some vugs or cavities, which are possible root traces, are filled with tridymite which may also replace some of the matrix.

3.e.4. Mixed sandstone-tuff

Microscopically, there is a distinct but minor petrofacies consisting of sandstone with incorporated tuff. The sandstone, usually a litharenite, has distinct microscopic layers or bodies of tuff or, if mixing is more thorough, a more abundant matrix that is partly tuffaceous.

3.f. Provenance

The sandstone-tuff assemblage clearly marks a major change in provenance from the underlying Falla Formation. The quartzo-feldspathic sandstones are in many cases characterized by coarse-grained garnet and angular K-feldspar pebbles, indicating a provenance dominated by granitoids but with a component of medium-grade metamorphic rocks. The coarse-grained arkoses imply a proximal elevated basement terrain. The igneous fragments in the litharenites, which are increasingly important upwards in the Hanson depositional system, indicate a source terrain that includes intermediate to silicic volcanic rocks; a distinction is made between the siliceous volcanic rock fragments having dacitic to rhyolitic compositions and those of alkaline composition, the latter being less common. Pebble- and very-coarse-sand-sized grains argue against long-distance transport and suggest relatively local derivation as opposed to a significant input from the plate margin during late Permian – Triassic time. Sandstone petrology suggests sources included granitoids, a metamorphic terrain and both rhyolitic and alkaline volcanic rocks. Some recycling of Permian and Triassic sandstones was probable, but such detritus cannot be distinguished. The granitoid and metamorphic rock sources could be the upper Neoproterozoic to Lower Ordovician Ross Orogen (Goodge et al. Reference Goodge, Fanning, Norman and Bennett2012). The rhyolitic source may have been the silicic volcanic rocks in the Ross Orogen (Stump, Reference Stump1995; Wareham et al. Reference Wareham, Stump, Storey, Millar and Riley2001), but the alkaline felsic fragments (also represented in the lag conglomerate at the Falla–Hanson contact; see also Barrett, Elliot & Lindsay, Reference Barrett, Elliot, Lindsay, Turner and Splettstoesser1986) have no known source except for the possibility of an extrusive phase accompanying Neoproterozoic–Cambrian alkaline plutonic rocks in south Victoria Land (Read, Cooper & Walker, Reference Read, Cooper, Walker, Gamble, Skinner and Henrys2002).

Detrital zircons from the quartzose sandstone (sample 90-2-67) suggest a major Ross-aged provenance. In a discussion of the Permian strata at Mount Bowers at the head of the Beardmore Glacier, Elliot, Fanning & Hulett (Reference Elliot, Fanning and Hulett2014) noted that zircons with the Gondwana margin signature could not have been derived from local Ross Orogen outcrops because the Victoria Group strata extended far out on either side of the known limits of the orogenic belt, and therefore had to have come from distal flanks. However, the coarse arkoses indicate local derivation from elevated shoulders of a rift, plausibly within the Transantarctic Mountains. Grenville-aged zircons must have been derived from an unexposed terrain of that age within the Ross Orogenic belt. Zircons in the litharenite (sample 11-11-3) have a Ross-aged component, similar to that in the quartzo-feldspathic sandstones, and a Late Triassic – Early Jurassic component. The three youngest grains must record contemporaneous volcanism, but the older Jurassic grains must have been recycled from older Hanson strata or equivalent-aged beds elsewhere. The Triassic grains in sample 11-11-3 were ultimately most likely derived from Triassic strata on the rift shoulders.

Zircons in the two analysed tuffs also have a small component with the Gondwana-margin signature, which could have two possible explanations. Either those zircons were an inherited component in the erupting magma, or they were derived through local surface reworking. In the former case, it implies Ross- and Grenville-aged crust along the Jurassic margin, for which there is no evidence. Further, those ages were not determined on inherited cores. Additionally, Sr and Nd isotope data (Elliot et al. Reference Elliot, Fleming, Foland, Fanning, Cooper and Raymond2007) have been used to argue that the Hanson tuffs were not derived by anatexis of subjacent Ross Orogen crust, and hence the tuffs do not contain a Ross granitoid geochemical component. The Gondwana-margin zircon signature in the tuffaceous beds is therefore interpreted to be the result of contamination by detrital material on surface reworking of these two tuffs.

Tuffs are largely fine to very fine grained, have only a small component of crystal and vitric particles, and range from massive structureless beds to those showing weak to strong planar bedding to those with low-angle cross-stratification. A few tuffs have accretionary lapilli (sections 39, 78, 85-3, 85-17). The shards in the tuffs are interpreted to be distal fallout from Plinian eruptions (Elliot & Larsen, Reference Elliot, Larsen, Findlay, Unrug, Banks and Veevers1993; Elliot, Reference Elliot2000). However, evidence for modification by surficial processes is widespread: palaeosols developed on tuffs have destroyed internal bedding and other possible structures; reworking with addition of non-volcanic sediment is indicated by outsize muscovite flakes and suggested by the sparseness of shards in many tuffs; zircon grains with pre-Jurassic dates are dominated by Ross Orogen ages, the same as the detrital zircons from Hanson sandstones; and poorly defined sweeping low-angle cross-bedding, indicative of transport by ephemeral streams (Picard & High, Reference Picard and High1973). Nevertheless, the few tuffs with accretionary lapilli (sections 85-3, 85-17, 39, 78), widely scattered geographically and stratigraphically, were probably not modified much by post-depositional processes. The tuff beds with poorly defined, low-angle cross-bedding are not attributed to deposition from pyroclastic surges (Fisher & Schmincke, Reference Fisher and Schmincke1984; Valentine & Fisher, Reference Valentine, Fisher and Sigurdsson2000; Francis & Oppenheimer, Reference Francis and Oppenheimer2004) because of moderate sorting and the lack of other indicators of near-vent deposition (e.g. coarse grain sizes and bomb sags).

3.g. Geochemistry

Previous analyses of tuffs (Elliot & Larsen, Reference Elliot, Larsen, Findlay, Unrug, Banks and Veevers1993) were interpreted to suggest a volcanic arc or volcanic arc plus syn-collision source based on the Pearce, Harris & Tindle (Reference Pearce, Harris and Tindle1984) discrimination diagrams. Further, the high silica content of most Hanson tuffs was interpreted to be the result of contamination of the tuffs by siliciclastic material during surface reworking. New analyses (Table 1) are presented here for 12 tuffaceous rocks from the Marshall Mountains. The stratigraphic positions of these samples are indicated on Figure 5, except for one (11-10-2) which comes from disturbed beds at Golden Cap (Fig. 3). An additional five analyses from the Otway Massif, and one each from south Victoria Land and north Victoria Land, are presented in Supplementary Table S5 (available at http://journals.cambridge.org/geo). The five from the Otway Massif (Fig. 4) are not well constrained stratigraphically: one (96-8-2) is from a short section without an exposed top or base; two (96-24-6 and -7) are from tuffaceous beds in megaclasts of Hanson strata enclosed in Prebble Formation breccias; and two (96-27-11 and -14) are from large tuffaceous clasts also in Prebble breccia. The south Victoria Land (Coombs Hills) sample (96-47-4) comes from a broken zone overlying the uppermost quartzose sandstone of the Lashly Formation (Elliot & Grimes, Reference Elliot and Grimes2011; section 02-2-6) and below a zone of mixed rock at the contact with Mawson Formation breccias. The north Victoria Land sample was collected at a limited quartz sandstone-tuff outcrop broken up by dolerite intrusions, located about 9 km north of Mount Hewson in the Deep Freeze Range (Elliot, unpublished data).

Table 1. New geochemical analyses of Hanson Formation tuffs from the Marshall Mountains. See Figure 5 for stratigraphic locations of samples.

XRF analyses conducted at Southern Connecticut State University. All samples were handpicked after coarse crushing to minimize alteration. Major elements determined on glass disks prepared using a lithium tetraborate–metaborate flux (12:22 mixture) and pre-ignited sample powders. Trace elements by XRF determined using pressed powder pellets.

ICP-MS analyses performed at Washington State University Geoanalytical laboratory on splits of the XRF samples.

Total Fe reported as Fe2O3*.

As a result of secondary alteration that involved significant hydration, all of these samples have high loss-on-ignition values, which influences the absolute concentrations of elements. The high-field-strength elements, particularly ratios between them, are generally more resistant to secondary processes, and are regarded as the most reliable petrogenetic indicators. The evidence for widespread reworking and alteration of the tuffaceous rocks renders geochemical interpretation somewhat problematic. Nevertheless, the new analyses from the Marshall Mountains are regarded as a fair representation of the original tuff compositions (discussed below). Careful selection of samples to minimize apparent contamination has resulted in the new analyses (Table 1) showing much less scatter (Fig. 10a, b) than previous results (Elliot & Larsen, Reference Elliot, Larsen, Findlay, Unrug, Banks and Veevers1993; Supplementary Table S5) and restricted distribution on multi-element diagrams. All new analyses (Table 1) have high loss-on-ignition (LOI) and several show depletions and enrichments (e.g. low K2O, CaO, Ba, Rb and Sr in 90-14-13, despite low LOI; cf. 90-17-15 with the highest LOI and Sr) relative to the majority of the data, suggesting secondary alteration even though not obvious microscopically. Similar scatter suggesting secondary alteration is also present in the Otway Massif (e.g. high Ba and Sr, and low K2O and Rb in 96-27-14) and Victoria Land samples (Supplementary Table S5). There is no correlation between LOI and Sr concentrations.

Figure 10. Discriminant diagrams of Pearce, Harris & Tindle (Reference Pearce, Harris and Tindle1984) for silicic tuffs of the Hanson Formation from the Marshall Mountains, Otway Massif, south and north Victoria Land. (a) Rb–(Nb+Y). (b) Nb–Y. VAG – volcanic arc granite; COLG – syn-collisional granite; ORG – ocean ridge granite; WPG – within-plate granite. Filled circles: Marshall Mountains tuffs; open circles: Otway Massif tuffs; crosses: south and north Victoria Land tuffs; star: Mount Poster low-Ti rhyolite (Riley et al. Reference Riley, Leat, Pankhurst and Harris2001, table 1, R.6892.1); filled star: rhyolite from the Altiplano–Puna Volcanic Complex of the central Andes (Lindsay et al. Reference Lindsay, Schmitt, Trumbull, de Silva, Siebel and Emmermann2001, table 6, Toconao crystal-poor pumice sample 96h-20a). Fields for Indian Peak-Caliente silicic rocks of the western USA (Best et al. Reference Best, Christiansen, Deino, Gromme, Hart and Tingey2013) enclosed by dashed line. Fields for previously published Hanson tuff analyses (Elliot & Larsen, Reference Elliot, Larsen, Findlay, Unrug, Banks and Veevers1993) enclosed by solid line.

On a total alkali-SiO2 diagram the majority of the tuffs are rhyolites, however the variability in alkali concentrations makes any further designation unreliable. On discriminant diagrams (Fig. 10), the tuffs plot in the volcanic-arc field. On a multi-element diagram (Fig. 11) the tuffs exhibit a fairly tight cluster except for Ba and Sr, again indicating element mobility and secondary alteration. The niobium-tantalum depletion depicted on the multi-element diagram (Fig. 11 and Supplementary Fig. S1, available at http://journals.cambridge.org/geo) suggests a volcanic-arc plate margin origin. Together with depletions in Sr, P and Ti, the patterns point to the generation of these tuffs involving arc magmas interacting with continental crust. All analysed tuffs show strong negative europium anomalies (Fig. 12 and Supplementary Fig. S2), indicating significant plagioclase fractionation in their evolution. The overall geochemistry does not suggest an extensional tectonic setting.

Figure 11. Multi-element diagram for silicic tuffs of the Hanson Formation (new analyses only) in the Marshall Mountains. Dashed line and crosses illustrate Mount Poster sample R.6892.1 (Riley et al. Reference Riley, Leat, Pankhurst and Harris2001). Normalizing factors for mid-ocean ridge basalt (N-MORB) from Sun & McDonough (Reference Sun, McDonough, Saunders and Norry1989).

Figure 12. Rare Earth element diagram for silicic tuffs of the Hanson Formation (new analyses only) in the Marshall Mountains. Normalizing factors for chondrite from Sun & McDonough (Reference Sun, McDonough, Saunders and Norry1989).

With respect to Nd and Sr initial isotope ratios (Table 2), the Hanson tuffs have a crustal imprint (Fig. 13). They lie off the Ferrar trend (Elliot et al. Reference Elliot, Fleming, Foland, Fanning, Cooper and Raymond2007) and are therefore not derived from sources similar to the crustal contaminants for those basaltic rocks. Neither Sr concentrations nor epsilon Nd exhibit a systematic relationship with Sr isotope initial ratios. Recognizing that Sr mobility (hence disturbed Sr isotope systematics) is indicated by the range of Sr concentrations, the tuffs do not overlap the field for subjacent Cambrian granitoids in the Transantarctic Mountains (Borg, DePaolo & Smith, Reference Borg, DePaolo and Smith1990) nor, to a large extent, the fields for Cambrian gneisses and Devonian, Carboniferous and Permo-Triassic granitoids in Marie Byrd Land (Pankhurst et al. Reference Pankhurst, Leat, Srugo, Rapela, Márquez, Storey and Riley1998 b). The Lower Jurassic Mount Poster Formation rocks (Riley et al. Reference Riley, Leat, Pankhurst and Harris2001) include just one sample (R.6892.1, which belongs to their low-Ti group) that falls close to the Nd–Sr isotope field for Hanson tuffs (Fig. 13), all others plotting at much higher Sr isotope initial ratios. That one sample, from the extra-caldera facies of the Mount Poster volcano, also falls within the envelope for the Hanson tuffs on the multi-element diagram (Fig. 11). One Silurian granitoid lies within the Nd–Sr envelope (Fig. 13) for the Lower Jurassic rocks, and one Cambrian gneiss and two Carboniferous granitoids lie close to the margin of the envelope. The Nd model ages of the Hanson samples are all late Mesoproterozoic, which is similar to model ages reported by Pankhurst et al. (Reference Pankhurst, Leat, Srugo, Rapela, Márquez, Storey and Riley1998 b) for Marie Byrd Land granitoids, by Riley et al. (Reference Riley, Leat, Pankhurst and Harris2001) for the Mount Poster sample (R.6892.1) and for Ross Orogen rocks on the edge of East Antarctica from the Shackleton Glacier to the Dufek Massif area (Borg, DePaolo & Smith, Reference Borg, DePaolo and Smith1990). There is no clear evidence for involvement of Marie Byrd Land Palaeozoic or lower Mesozoic granitoids of any particular age in the generation of the Early Jurassic magmas, but a clear suggestion of upper Mesoproterozoic crust at greater depth.

Table 2. Rb, Sr, Sm and Nd concentrations and 87Sr/86Sr and 143Nd/144Nd present-day and calculated initial ratios at 186 Ma for silicic tuffs of the Hanson Formation.

Isotope ratio measurements performed by MC-ICP-MS at Washington State University.

* Present-day measured isotopic ratios normalized using 86Sr/88Sr = 0.1194 or 146Nd/144Nd = 0.7219. 2σ mean within-run uncertainties in the last two digits are given in parentheses. Mean values (and 2σ external reproducibilities) for standards measured during the same period are: NBS 987, 87Sr/86Sr = 0.710255 (±0.000016); and La Jolla Nd, 143Nd/144Nd = 0.511830 (±0.000018). Rb and Sr concentrations and 87Rb/86Sr ratio by XRF. Sm and Nd concentrations and 147Sm/144Nd ratios determined by isotope dilution using MC-ICP-MS.

† Model initial ratios at 186 Ma calculated with decay constants of 1.42×10–11 (87Rb) or 6.54×10–12 (147Sm); uncertainties (in parentheses) provide for uncertainties in present-day measured isotopic ratios, parent/daughter ratios (0.5% for 87Rb/86Sr or 0.1% for 147Sm/144Nd).

‡ Conventional epsilon notation for 186 Ma with reference values of 147Sm/144Nd = 0.1960 and 143Nd/144Nd = 0.512630 (Bouvier, Vervoort & Patchett, Reference Bouvier, Vervoort and Patchett2008).

§TDM calculated with reference values of 143Nd/144Nd = 0.513142 and 147Sm/144Nd = 0.2136 (Goldstein & Jacobsen, Reference Goldstein and Jacobsen1988; Nd isotope ratio recalculated to reference value of 143Nd/144Nd = 0.512630).

Figure 13. εNd186 Ma versus 87Sr/86Sr186 Ma for silicic tuffs of the Hanson Formation, together with silicic tuff data from Elliot et al. (Reference Elliot, Fleming, Foland, Fanning, Cooper and Raymond2007). Also plotted are data from Pankhurst et al. (Reference Pankhurst, Leat, Srugo, Rapela, Márquez, Storey and Riley1998 b) for Marie Byrd Land granitoids and gneisses, and Riley et al. (Reference Riley, Leat, Pankhurst and Harris2001) for a rhyolitic rock of the Mount Poster Formation, Antarctic Peninsula (most Mount Poster rocks plot outside the diagram at much higher initial 87Sr/86Sr ratios). In the legend, the italicized Hanson tuff data are those from the Otway Massif and Victoria Land. The initial ratios of the Marie Byrd Land granitoids and gneisses have been re-calculated to a common age of 186 Ma; a slightly older age, given the duration of silicic magmatism, makes no difference to the pattern.

The few tuffaceous beds regarded as unequivocal airfall deposits because of their structureless character (e.g. sample 11-11-15) have geochemical characteristics very similar to the other analysed samples. Microscopically, the analysed rocks (Table 1) lack identifiable extraneous material such as muscovite. These new analyses cluster together on all the geochemical diagrams, recognizing that there is scatter in the mobile elements. Analyses listed in the Supplementary Table S5 (available at http://journals.cambridge.org/geo) also fall within the fields for the new analyses except for sample 96-27-14; this tuff comprises packed glass shards and scattered mineral grains, and lacks identifiable extraneous material although Rb, Ba and Sr concentrations clearly indicate secondary alteration. It is the only sample that suggests a slightly different evolutionary path from that of all other tuffs. Within the uncertainties introduced by the evidence for surface reworking, the geochemical analyses are regarded as fair indicators of the original tuff compositions.

3.h. Palaeoenvironmental setting

The tuffaceous rocks of the Hanson Formation reflect an extended period of silicic volcanism. The thickness of tuff and the age constraints imply substantial volcanic activity over more than 10 million years. The fine grain size (<0.25 mm), bubble-wall and tricuspate shard form, and crystal-poor nature suggest derivation from distal Plinian eruptions, as proposed for these tuffs by Elliot & Larsen (Reference Elliot, Larsen, Findlay, Unrug, Banks and Veevers1993). Nevertheless, a few medium-grained tuffs in the upper part of the Hanson Formation, and the presence at Mount Marshall (section 78) of tuffs with glass shards as large as 0.5 mm across and pumice clasts as large as 1.5 mm across, argue for more proximal, but minor, volcanic sources. Additionally, a few tuffs with accretionary lapilli are widely scattered geographically and stratigraphically.

Evidence for modification by surficial processes is widespread: palaeosols developed on tuffs have destroyed internal bedding and other possible structures; reworking with addition of non-volcanic sediment is indicated by outsize muscovite flakes and suggested by the sparseness of shards in many tuffs; zircon grains with pre-Jurassic dates that are dominated by Ross Orogen ages, the same as the detrital zircons from a Hanson sandstone; and poorly defined sweeping low-angle cross-bedding indicative of transport by ephemeral streams (Picard & High, Reference Picard and High1973). However, the few tuffs with accretionary lapilli were probably not modified much by post-depositional processes. The tuff beds with poorly defined, low-angle cross-bedding are not attributed to deposition from pyroclastic surges (Fisher & Schmincke, Reference Fisher and Schmincke1984; Valentine & Fisher, Reference Valentine, Fisher and Sigurdsson2000; Francis & Oppenheimer, Reference Francis and Oppenheimer2004) because of moderate sorting and the lack of other indicators of near-vent deposition (e.g. coarse grain sizes and bomb sags).

Accretionary lapilli are commonly formed by phreatomagmatic processes and imply deposition proximal to active vents (Schumacher & Schmincke, Reference Schumacher and Schmincke1995). However, they are also formed by interaction between ash and condensed moisture in clouds, and therefore may be deposited farther afield. For instance, accretionary lapilli in the Oruanui Formation, New Zealand, have been found 140 km from the vent (Self & Sparks, Reference Self and Sparks1978), suggesting their transport to yet greater distances is possible.

The Hanson Formation is dominated by two lithologic facies: coarse- to medium-grained sandstone (quartzose sandstone and litharenite); and tuffaceous beds. The sandstones are probably low-sinuosity sandy-braided stream deposits (e.g. Miall, Reference Miall1996), with the multistory cross-bedded sandstone bodies representing sand aggradation as various bar forms in broad channels and the thinner sandstone intervals representing either side channels or crude splay deposits. Where well-stratified (as in section 90-14 at c. 25–40 m), the intervening fine-grained tuffaceous beds possibly represent overbank deposits and/or ash recycled by ephemeral streams or aeolian processes. Only a few ash fallout beds of certain origin have been identified. The upsection increase in tuffaceous material reflects depositional systems that were increasingly choked with ash, leading to greater preservation of volcaniclastic material and to mud and tuff clasts in channel sandstones. The fine-grained portion of the Hanson Formation was deposited as a distal volcaniclastic succession (e.g. Smith, Reference Smith, Ethridge, Flores, Harvey and Weaver1987, Reference Smith, Fisher and Smith1991); the coarser sand facies and sheet-like bed geometry, even in the upper member, suggest continuing erosion of a proximal, predominantly plutonic and volcanic, source.

The sandstone petrology indicates two provenance sources: one is a granitic and metamorphic basement and the other a volcanic terrain of dacitic to rhyolitic and, to a lesser extent, alkaline geochemical composition. The coarse grain size of the volcanic rock fragments, similar to that of the quartzose component in the litharenites, is interpreted as indicating a pre-existing source rather than contemporaneous volcanic centres. It is notable that quartzose sandstones are present relatively high in the upper member (section 11-11) and pebbly sandstones (litharenites) are present in the section right up to the contact with the overlying Prebble beds. Given the inferred depositional setting, regional differences in lithologic succession are to be expected. With regard to the overall depositional setting, the Hanson strata bear similarities to the several-hundred-metres-thick High Plains Cenozoic sequence of eastern Wyoming, Nebraska and South Dakota (Stanley, Reference Stanley1976; Evanoff et al. Reference Evanoff, Terry, Benton and Minkler2010; Benton et al. Reference Benton, Terry, Evanoff and McDonald2015). In those strata arkosic and other sandstones fill broad channels that are interbedded with thick sequences of fine-grained fluvial, aeolian and lacustrine deposits, which have a significant component of fine-grained ash derived from distal volcanoes, together with subordinate airfall ash beds. Correlation of some individual tuffs with known contemporaneous Cenozoic volcanic centres suggests deposition as much as 1000 km from their eruptive sources in SW Utah and southern Nevada (Larson & Evanoff, Reference Larson, Evanoff, Terry, LaGarry and Hunt1998; Best et al. Reference Best, Christiansen, Deino, Gromme, Hart and Tingey2013). Fine-grained Hanson tuffaceous beds could therefore have been derived from sources hundreds of kilometres away, either by direct airfall or by recycling of ash deposited upwind through aeolian processes as suggested for the High Plains sequence (Benton et al. Reference Benton, Terry, Evanoff and McDonald2015); however, direct evidence of aeolian deposition has not been recognized.

The tectonic setting for the Hanson Formation has been discussed previously (Elliot & Larsen, Reference Elliot, Larsen, Findlay, Unrug, Banks and Veevers1993; Elliot, Reference Elliot2000, Reference Elliot, Hambrey, Barker, Barrett, Bowman, Davies, Smellie and Tranter2013) and pertinent aspects are summarized below. The lag conglomerate at the base of the Hanson Formation, and the abrupt change in sandstone composition together with the appearance of tuffs, marks the end of foreland basin deposition inferred for the Victoria Group in the central Transantarctic Mountains (Collinson et al. Reference Collinson, Elliot, Isbell, Miller, Veevers and Powell1994). The presence of arkoses with angular detritus and common garnet is interpreted to be the result of local basement uplift. The coarse grain size, particularly the angular pebble-sized K-feldspar, alone suggests a relatively proximal source compared with the distal plate margin and craton sources inferred for the Victoria Group. Reliable palaeocurrent data are very sparse, but suggest that palaeoflow was generally to the NW quadrant.

Structural features affecting Hanson strata and the overlying rock units (Prebble Formation and Kirkpatrick Basalt) provide supporting data for a rift setting (Elliot & Fleming, Reference Elliot and Fleming2008). Two high-angle reverse faults dipping east cut Hanson beds at Mount Falla, and Prebble Formation breccia is intruded along one of the faults and defines the hingeline of a NW-facing monocline affecting those strata (Fig. 3). At Lindsay Peak stratigraphic relationships point to another monocline that flexes Hanson beds (Elliot & Larsen, Reference Elliot, Larsen, Findlay, Unrug, Banks and Veevers1993), one which is E-facing and with more than 50 m of displacement. Just to the east of Lindsay Peak the Kirkpatrick Basalt flows also show apparent monoclinal offset of about 300 m down to the east (Barrett, Elliot & Lindsay, Reference Barrett, Elliot, Lindsay, Turner and Splettstoesser1986). The thickness of many basalt flows (tens of metres up to 135 m at Storm Peak, Marshall Mountains) suggests they are ponded and hence confined by palaeotopography. The postulated tectonic rift therefore became the site for sediment derived from the surrounding rift shoulders and for ash from distal eruptions.

A bounding fault for the inferred rift may be present along the Marsh Glacier (Fig. 14) where a major E-facing fault (Marsh Fault), with cumulative displacement of 2 km, separates the Precambrian rocks of the Miller Range from Victoria Group rocks to the east (Elliot, Reference Elliot, Hambrey, Barker, Barrett, Bowman, Davies, Smellie and Tranter2013). Boundary faults elsewhere for the inferred rift are presumed to be under ice outside the geographic Transantarctic Mountains. Other faults have an order of magnitude less displacement: a W-facing monocline/fault lies parallel to, and east of, the Marsh Fault and displaces Victoria Group strata by about 350 m (Barrett, Elliot & Lindsay, Reference Barrett, Elliot, Lindsay, Turner and Splettstoesser1986); the fault at the Moore Mountains is illustrated (Barrett, Lindsay & Gunner, Reference Barrett, Lindsay and Gunner1970) as normal down to the west, and is projected into the monoclinal structure at Mount Weeks. An unexamined monocline facing east is present in the Dominion Range (Elliot, Barrett & Mayewski, Reference Elliot, Barrett and Mayewski1974) and may lie along strike from the dipping basal Permian strata at Mount Bowers (Young & Ryburn, Reference Young and Ryburn1968; Elliot, Fanning & Hulett, Reference Elliot, Fanning and Hulett2014). A NW–SE-striking small graben with offset of a few hundred metres is situated in the southern Marshall Mountains (Barrett & Elliot, Reference Barrett and Elliot1973); a fault down to the west cuts Coalsack Bluff, displacing upper Buckley beds and lower Fremouw strata (Collinson & Elliot, Reference Collinson, Elliot, Turner and Splettstoesser1984); and an uplifted isolated fault block of north-dipping lower Permian strata overlying Cambrian limestone, demonstrating some 500 m of uplift, is present just to the west of Coalsack Bluff. Structural studies by Wilson (Reference Wilson, Findlay, Unrug, Banks and Veevers1993) on faults and dolerite dykes in the central Transantarctic Mountains suggested extension prior to and during basalt magmatism. Extension directions were sub-perpendicular and oriented ENE and NW, the former sub-parallel with the Mount Falla monocline, but others are not coincident with the extension directions. The distance (c. 125 km) back from the Cenozoic frontal faults of the Transantarctic Mountains along the Ross embayment flank, which are associated with development of the West Antarctic Rift System, suggests the Marsh Fault pre-dates that event and was probably active during Early Jurassic time.

Figure 14. Sketch map of part of the central Transantarctic Mountains to illustrate structural features. Note: orientation is with north up.

Elliot & Fleming (Reference Elliot and Fleming2008) suggested that the phreatomagmatic deposits of the Prebble Formation and its equivalents were erupted into low-lying regions of a linked rift system of Early Jurassic age. In this context, the inferred rift setting for the Hanson deposition was the first stage in the development of an extensive rift valley system several thousand kilometres long along which basaltic magmatism was focused later in Early Jurassic time. The monocline and associated reverse fault offsetting Hanson beds is oblique to the inferred bounding faults. Assuming the Early Jurassic rift valley system was segmented, then the reverse faulting might reflect a region where the facing of the grabens switched, as is observed in the East African Rift Valleys (Chorowicz, Reference Chorowicz2005). However, the analogy cannot be taken far: the Transantarctic Mountain Jurassic sequences are relatively thin and lack evidence for tilting of the pre-rift rocks, and compelling evidence for major basement structures of that age is lacking. Rifting ceased after the short-lived Ferrar magmatism, although rift sedimentation might have continued for some time thereafter.

The presence of a disconformity between the Hanson and Falla formations is based on a lag conglomerate with clasts up to 10 cm across and varying locally from 0–40 cm in thickness. The only complete and measured section through the revised Falla Formation (see Elliot, Reference Elliot1996) is at Mount Falla. At Mount Kirkpatrick, Barrett (in Barrett, Elliot & Lindsay, Reference Barrett, Elliot, Lindsay, Turner and Splettstoesser1986) measured 40–50 m of what is now the revised Falla Formation; however, there is no contact with the Fremouw Formation (that contact might be present on the west face of Mount Kirkpatrick, below section 11-11). North of Tempest Peak (section 79) the Hanson beds are more than 200 m thick, but neither upper nor lower contact is exposed. Elsewhere in the Marshall Mountains the thickness of the Hanson beds appears to be significantly less. In the Kenyon Peaks region, Fremouw strata beneath a prominent sill can be traced from the north and the upper contact of the sill is only 100–200 m below the Prebble Formation. This interval includes at least 100 m of Hanson strata, suggesting less than 100 m of Falla beds. Only on the east face of Mount Marshall might it be possible to obtain accurate thicknesses for Falla and Hanson strata. Assuming the lag conglomerate represents a disconformity, then changes in thickness of the Hanson Formation can be attributed in part to infilling of palaeotopography incised into Falla beds.

4. Discussion

4.a. Correlative silicic volcanism in the Transantarctic Mountains

Silicic volcanism is also recorded in south and north Victoria Land (Fig. 1). In south Victoria Land, 47+ m of silicic ash-bearing strata overlie the Triassic Lashly Formation at Coombs Hills (Elliot & Grimes, Reference Elliot and Grimes2011); however, the lower contact is obscure and an upper contact is absent. Silicic tuff is also present as clasts in the basaltic Mawson Formation and in a mixed zone at a Lashly/Mawson contact at Coombs Hills (Bradshaw, Reference Bradshaw1987; Elliot, Fortner & Grimes, Reference Elliot, Fortner, Grimes, Futterer, Damaske, Kleinschmidt, Miller and Tessensohn2006). Together, these data suggest a formerly more extensive tuff sequence that has been almost completely removed by erosion.

In north Victoria Land a more extensive but geographically scattered record of silicic volcanism is present between the Priestley Glacier and Roberts Butte (Fig. 1). Although silicic ash is present in the uppermost 20 m of the Triassic–Jurassic Section Peak Formation (Collinson, Pennington & Kemp, Reference Collinson, Pennington, Kemp and Stump1986; Schöner et al. Reference Schöner, Bomfleur, Scheidner and Viereck-Götte2011; Elsner et al. Reference Elsner, Schöner, Gerdes, Gaupp, Harley, Fitzsimons and Zhao2013), the principal occurrence is in the overlying Shafer Peak Formation which has a restricted distribution in the Deep Freeze Range, and to the east of the southern Mesa Range. The thickness at the type section at Mount Shafer is 53 m (Schöner et al. Reference Schöner, Viereck-Götte, Scheidner, Bomfleur, Cooper and Raymond2007, Reference Schöner, Bomfleur, Scheidner and Viereck-Götte2011). It consists of tuffaceous siltstones and fine-grained sandstones interpreted as reworked fallout tuff; plant assemblages establish a middle Pliensbachian (Early Jurassic) age (Bomfleur, Pott & Kerp, Reference Bomfleur, Pott and Kerp2011; Bomfleur et al. Reference Bomfleur, Schöner, Schneider, Viereck, Kerp and Mckellar2014). Unlike the Hanson Formation, the Shafer Peak Formation is interbedded with basaltic pyroclastic rocks of the redefined Exposure Hill rocks (Viereck-Götte et al. Reference Viereck-Götte, Schöner, Bomfleur, Schneider, Cooper and Raymond2007), indicating contemporaneous basaltic and silicic volcanism although derived from different sources.

The palaeontological age assignments for the Section Peak Formation are largely supported by U–Pb age determinations. A tuff from the upper part of the Section Peak strata at Shafer Peak gave a SHRIMP age of 188.2±2.2 Ma (Bomfleur et al. Reference Bomfleur, Schöner, Schneider, Viereck, Kerp and Mckellar2014), which is consistent with the ages for the Hanson tuffs. Detrital zircon ages for the Section Peak at its type locality (west of the southern Mesa Range) indicate an age no older than 191±4 Ma (deconvolved into a younger group at c. 187 Ma and an older group at c. 193 Ma; Goodge & Fanning, Reference Goodge and Fanning2012); these are the youngest ages determined for this formation and they come from a sample close to the basement nonconformity, thus implying the Section Peak beds at that locality are no older than Early Jurassic (c. 187 Ma). Older palynological ages and a detrital zircon age no older than 218±4 Ma (and others with younger Triassic and Jurassic detrital zircon ages) have been reported for correlative rocks in the Deep Freeze Range region (Elsner et al. Reference Elsner, Schöner, Gerdes, Gaupp, Harley, Fitzsimons and Zhao2013; Bomfleur et al. Reference Bomfleur, Schöner, Schneider, Viereck, Kerp and Mckellar2014), suggesting the possibility of a diachronous lower contact. The 191±4 Ma age indicates that silicic volcanism might have been initiated later in north Victoria Land than in the central Transantarctic Mountains where tuff underlies the lower dated tuff (194.0±1.3 Ma) at Mount Kirkpatrick (Fig. 5), although the ages are within uncertainties. There is also temporal overlap between the silicic volcanism and Ferrar magmatism, although high-precision dating of north Victoria Land Ferrar rocks is needed to establish more precisely the relationships with the silicic magmatism and then with Ferrar rocks elsewhere in the Transantarctic Mountains.

With respect to the depositional setting, the unnamed conglomeratic beds and the carbonaceous strata of the Permian Takrouna Formation in north Victoria Land, mostly derived locally, were deposited in a NW-trending basin, possibly a deep valley or even a rift valley (Collinson, Pennington & Kemp, Reference Collinson, Pennington, Kemp and Stump1986). No contact between the Permian beds and the Upper Triassic – Lower Jurassic Section Peak Formation is known; if continuous deposition had occurred, all evidence has been removed by erosion. Where the contact is exposed, all Section Peak strata overlie basement granite and metamorphic rocks (Elsner et al. Reference Elsner, Schöner, Gerdes, Gaupp, Harley, Fitzsimons and Zhao2013), and evidence for Early and Middle Triassic deposition is absent. Relative to the Permian strata, the Section Peak beds record a major change to braided stream deposition of quartzose detritus derived from uplifted basement rocks and, to a lesser extent, from Palaeozoic–Mesozoic arcs (Elsner et al. Reference Elsner, Schöner, Gerdes, Gaupp, Harley, Fitzsimons and Zhao2013).

4.b. Regional tectono-stratigraphic summary

In contrast to the central Transantarctic Mountains, in south Victoria Land there does not appear to be a disconformity between the Upper Triassic Lashly Formation and the overlying silicic-shard-bearing rocks (Elliot & Grimes, Reference Elliot and Grimes2011) or in north Victoria Land between the Section Peak and Shafer Peak formations (Schöner et al. Reference Schöner, Viereck-Götte, Scheidner, Bomfleur, Cooper and Raymond2007, Reference Schöner, Bomfleur, Scheidner and Viereck-Götte2011; Viereck-Götte et al. Reference Viereck-Götte, Schöner, Bomfleur, Schneider, Cooper and Raymond2007). There is not extensive enough exposure to assess this with certainty in either area but, if correct, may simply reflect slightly different timing of rift initiation.

A rift setting has been proposed for the Lower Jurassic rocks in the Transantarctic Mountains, based on a combination of data from the Hanson Formation and the extrusive rocks of the Ferrar Province (Elliot, Reference Elliot2000, Reference Elliot, Hambrey, Barker, Barrett, Bowman, Davies, Smellie and Tranter2013; Elliot & Fleming, Reference Elliot and Fleming2008). Much of the data come from the central Transantarctic Mountains where the silicic rocks are widely distributed and, in places, well exposed. In south Victoria Land, palaeotopography is suggested by the breccia deposit in the Mawson Formation, which is interpreted as a landslide (Reubi, Ross & White, Reference Reubi, Ross and White2005; Ross, White & McClintock, Reference Ross, White and McClintock2008). On the other hand the argument for a rift setting depends on interpretation of Ferrar rocks, principally the pyroclastic rocks representing a large-scale phreatocauldron (White & McClintock, Reference White and McClintock2001; Ross, White & McClintock, Reference Ross, White and McClintock2008) which indicates abundant groundwater in a topographic low, and on the 100 m thick pillow basalt sequence in the Prince Albert Mountains (Elliot, Reference Elliot, Gamble, Skinner and Henrys2002; Elliot & Fleming, Reference Elliot and Fleming2008). In north Victoria Land exposures of the silicic volcanic rocks are scattered, but Ferrar phreatomagmatism (Viereck-Götte et al. Reference Viereck-Götte, Schöner, Bomfleur, Schneider, Cooper and Raymond2007) again indicates abundant groundwater and the thick Kirkpatrick lava flows (100+ m) suggest ponding by topography (Elliot & Fleming, Reference Elliot and Fleming2008).

In the central Transantarctic Mountains onset of silicic volcanism can be dated only as beginning in Early Jurassic time before c. 194 Ma; airfall tuffs form an increasing component of the stratigraphic record up to the onset of basaltic magmatism at 183–182 Ma (Burgess et al. Reference Burgess, Bowring, Fleming and Elliot2015). Silicic magmatism continued at least intermittently and at a low level throughout the short-lived eruption of Ferrar lavas. The onset of silicic volcanism in south Victoria Land has not been established, but it was later in north Victoria Land where a tuff interbedded in the upper Section Peak strata is dated at c. 188 Ma. Unfortunately, in north Victoria Land no U–Pb zircon age information exists for the Kirkpatrick Basalt to constrain the onset of basaltic magmatism, although the data for the Ferrar province as a whole (Burgess et al. Reference Burgess, Bowring, Fleming and Elliot2015) suggests it would be 183–182 Ma. In Tasmania, zircons interpreted to have been derived from felsic volcanic clasts in sandstones (Bromfield et al. Reference Bromfield, Burrett, Leslie and Mefre2007) have yielded a maximum depositional age of 182±4 Ma. These sandstones underlie Jurassic basaltic andesite lavas correlated with the Tasmanian Dolerites, which are part of the Ferrar province.

Overall, distal Plinian eruptions are postulated to be the source of the fine- to very-fine-grained silicic ash in the central Transantarctic Mountains and Victoria Land. In the central Transantarctic Mountains however, a few medium-grained tuffs are observed in the upper member and argue for a component of relatively local derivation because the particle size (up to 2.5 mm) is far greater than that of the enclosing tuffaceous beds. Similarly, accretionary lapilli could indicate more proximal sources.

4.c. The Gondwana plate margin

The broader context for the silicic magmatism has to be assessed in terms of the Gondwana plate margin prior to break-up, which was no later than c. 183–182 Ma. Reconstruction of the Antarctic sector of the margin involves uncertainties (see Elliot, Reference Elliot, Hambrey, Barker, Barrett, Bowman, Davies, Smellie and Tranter2013; Elliot, Fanning & Laudon, Reference Elliot, Fanning and Laudon2014). Structural and palaeomagnetic data argue for major displacements and rotations of the continental blocks that now make up West Antarctica and the Antarctic Peninsula. Unfortunately, the lack of geologic pinning points leads to considerable uncertainty in along-strike locations for the assemblage that now makes up West Antarctica and greater New Zealand (Zealandia). The reconstruction used here (Fig. 15) is based on the PLATES UTIG reconstruction (Lawver et al. Reference Lawver, Dalziel, Norton, Gahagan and Davis2014), with modifications to accommodate presumed former geologic continuity between the present displaced continental blocks.

Figure 15. Gondwana reconstruction for Early Jurassic time. The two almost-overlapping granitoid symbols in the Thurston Island (TI) block are two intrusions reported to be Early Jurassic in age (Adams, Reference Adams2008), and the two granitoid symbols in eastern New Zealand (NZE) are clasts in sedimentary sequences (see text). See Elliot, Fanning & Laudon (Reference Elliot, Fanning and Laudon2014) for the Erehwon–FitzGerald block. The Gondwana deformation front was formed during latest Permian through Triassic time. Permo-Triassic strata (the Gondwana sequence) are co-extensive with the Ferrar Large Igneous Province in Antarctica. Reconstruction after the PLATES UTIG project (Lawver et al. Reference Lawver, Dalziel, Norton, Gahagan and Davis2014).