1. Introduction

Northeastern (NE) China is characterized by immense Phanerozoic granitic rocks, which are traditionally regarded as being of upper Palaeozoic age. In the past several years, geochronological studies have indicated that Palaeozoic granitoids are not as widely distributed in the area as previously thought, and most of them were emplaced in Mesozoic time (Wu et al. Reference Wu, Sun, Li, Jahn and Wilde2002, Reference Wu, Jahn, Wilde, Lo, Yui, Lin, Ge and Sun2003, Reference Wu, Sun, Ge, Zhang, Grant, Wilde and Jahn2011). Petrographically, the Mesozoic granitoids range from granodiorite (minor), monzogranite and syenogranite to alkali feldspar granite and alkaline granite, which are mostly felsic I- and A-types according to the criteria of Chappell & White (Reference Chappell and White1992) and Whalen, Currie & Chappell (Reference Whalen, Currie and Chappell1987). Among those various types of granitoids, alkali feldspar granite and alkaline granite are composed principally of quartz and perthitic feldspar, accompanied by minor amounts of plagioclase and ferromagnesian and other accessory minerals. Most of these granites contain biotite (< 5%) as the only mafic mineral. In addition, many contain abundant miarolitic cavities but enclaves are rarely seen. These kinds of fractionated granites in the past have mostly been considered as A-type granites (Li & Yu, Reference Li and Yu1993; Sun et al. Reference Sun, Wu, Li and Lin2000; Jahn et al. Reference Jahn, Wu, Capdeviala, Fourcade, Wang and Zhao2001; Wu et al. Reference Wu, Sun, Li, Jahn and Wilde2002; Zhang et al. Reference Zhang, Parrish, Zhang, Xu, Yuan, Gao and Crowley2007; Yang et al. Reference Yang, Niu, Shan, Sun, Zhang, Li, Jiang and Yu2013 and so on). Owing to the difficulties in distinguishing between the A-type and highly fractionated I-type granites, whether or not these Mesozoic alkali feldspar granites and alkaline granites all belong to A-type granites is still in dispute.

On the other hand, the Mesozoic miarolitic alkali feldspar granites mentioned above are also widespread in the central part of the Great Xing’an Range. However, they have rarely been precisely dated and studied in detail. Furthermore, most of the previous studies were limited to the Nianzishan and Baerzhe plutons that only occupy a small part of the Great Xing’an Range (Li, Yu & Chen, Reference Li, Yu and Chen1994; Wang & Zhao, Reference Wang and Zhao1997; Jahn et al. Reference Jahn, Wu, Capdeviala, Fourcade, Wang and Zhao2001; Wei et al. Reference Wei, Zheng, Zhao and Valley2002; Yang et al. Reference Yang, Niu, Shan, Sun, Zhang, Li, Jiang and Yu2013), which significantly hampers understanding of the petrogenesis and geodynamic setting of these rocks.

In this paper, we present new zircon U–Pb ages and Hf isotopes and whole-rock geochemical data for three alkali feldspar granitic plutons in the central part of the Great Xing’an Range, with the aim of constraining the formation time, magma source and petrogenesis of these granitoids. These data are then used to investigate the spatial and temporal distribution of these alkali feldspar granites in the whole Great Xing’an Range, and further discuss what constraints they impose on the tectonic evolution of NE China.

2. Geological settings and sample descriptions

NE China is located within the eastern part of the Palaeozoic Central Asian Orogenic Belt (CAOB) (Jahn, Wu & Chen, Reference Jahn, Wu and Chen2000; Jahn, Reference Jahn, Malpas, Fletcher, Ali and Aitchison2004), separated from the North China Craton by the Chifeng–Bayan fault belt in the south (Fig. 1a, inset), which is called the Xingmeng (Xing’an–Mongolian) orogenic belt (XMOB) in the Chinese literature. It is composed of a series of micro-continents (Ye, Zhang & Zhou, Reference Ye, Zhang and Zhou1994), including the Erguna and the Xing’an blocks in the northwest, the Songliao block in the central part and the Jiamusi–Khanka Massif in the southeast, separated by the Tayuan–Xiguitu, Hegenshan–Heihe and Jiayin–Mudanjiang faults, respectively (Ye, Zhang & Zhou, Reference Ye, Zhang and Zhou1994; Wu et al. Reference Wu, Li, Yang and Zheng2007; Zhang, J. H. et al. Reference Zhang, Ge, Wu, Wilde, Yang and Liu2008; Wilde, Wu & Zhao, Reference Wilde, Wu, Zhao, Kusky, Zhai and Xiao2010; Zhou et al. Reference Zhou, Wilde, Zhao, Zhang, Zheng, Wang and Zeng2010a ,Reference Zhou, Wilde, Zhao, Zhang, Zheng and Wang b , Reference Zhou, Wilde, Zhang, Zhao, Liu, Qiao, Ren and Liu2011a ,Reference Zhou, Wilde, Zhao, Zhang, Zheng and Wang b ; Fig. 1a). The Great Xing’an Range is situated in the western part of the XMOB in NE China. This region is characterized by immense volumes of Mesozoic granitic intrusions and, together with the granitoids in the Zhangguangcai Range and Lesser Xing’an Range, constitutes one of the super-large granitic provinces in the world (Wu & Sun, Reference Wu and Sun1999).

Figure 1. (a) Tectonic sketch map of NE China. (b) A detailed geological map of the Mingshui–Jilasitai –Suolun area showing sample locations.

According to high-precision data published during the past decades, Wu et al. (Reference Wu, Sun, Ge, Zhang, Grant, Wilde and Jahn2011) concluded that those Mesozoic granitic rocks were mainly emplaced during Upper Triassic to Lower Jurassic and Lower Cretaceous times (Fig. 2). The present study was carried out in the Ulanhot area in the Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region, situated within the central Great Xing’an Range. Tectonically, the study field area is located close to the Hegenshan–Heihe fault belt. The granitoids cropping out are mainly composed of Lower Cretaceous granodiorites, monzogranites, syenogranites and alkali feldspar granites. In addition, upper Palaeozoic and Mesozoic–Cenozoic volcanic–sedimentary assemblages also occur widely in the region (Fig. 1b; IMBGMR, 1990). In this paper, three Lower Cretaceous alkali feldspar granitic intrusions in the central part of the Great Xing’an Range, named the Mingshui (MS), Jilasitainangou (JLSTNG) and Suolunjunmachang (SLJMC) plutons, were chosen for geochemical and geochronological investigations (Fig. 1b).

Figure 2. Temporal-spatial distribution map of granitic rocks in the Great Xing’an Range (after Wu et al. Reference Wu, Sun, Ge, Zhang, Grant, Wilde and Jahn2011).

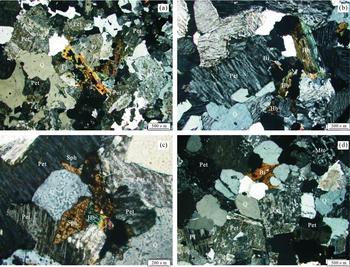

The Mingshui pluton, located to the east of Mingshui town, intrudes the Upper Jurassic volcaniclastic sequences, and extends along an E–W belt (Fig. 1b; IMBGMR, 1990). The pluton consists mainly of hornblende-bearing alkali feldspar granite with a miarolitic texture and a massive structure. The rocks are composed principally of quartz (40–45%), alkali feldspar (45–55%), plagioclase (4–6%) and hornblende (3–5%), with minor biotite (< 2%) and accessory magnetite, zircon and apatite (< 2%) (Fig. 3a). The occurrence of a miarolitic texture suggests a shallow level emplacement with the presence of a vapour phase.

Figure 3. Representative photomicrographs for the Mingshui, Jilasitainangou and Suolunjunmachang plutons in the central part of the Great Xing’an Range: (a) alkali feldspar granite (12GW104), cross-polarized light; (b) alkali feldspar granite (GW04195), cross-polarized light; (c) alkali feldspar granite (GW04195) with sphene and epidote (cross-polarized light); (d) alkali feldspar granite (GW04370), cross-polarized light. Bi – biotite; Hb – hornblende; Pl – plagioclase; Pet – perthite; Mic – microcline; Q – quartz; Ep – epidote; Sph – sphene.

The Jilasitainangou pluton, located in an area south of Jilasitai town, intrudes the Upper Jurassic to Lower Cretaceous volcaniclastic rocks to the north and is in contact with the Cretaceous syenogranite to the south (Fig. 1b; IMBGMR, 1990). The pluton is dominated by alkali feldspar granite with a fine- to medium-grained texture and a massive structure. The main minerals are quartz (40–45%), alkali feldspar (50–55%) and hornblende (2–3%), with minor biotite (< 2%) (Fig. 3b). Accessory minerals are magnetite, sphene, epidote, zircon and apatite (Fig. 3c).

The Suolunjunmachang pluton, located near Suolunjunmachang village in Suolun town, extends nearly elliptically as an intrusive stock. It intrudes the Upper Permian strata and the Upper Jurassic Manitu Formation (Fig. 1b; IMBGMR, 1990). The pluton has a similar mineral assemblage to that of the above two plutons, and is also alkali feldspar granite. The main rock-forming minerals are quartz (40–45%), alkali feldspar (45–50%), plagioclase (4–7%) and biotite (3–6%), with minor hornblende, and accessory fluorite, zircon and magnetite (Fig. 3d).

3. Analytical methods

3.a. Zircon U–Pb dating

Zircon grains were extracted at the Langfang Geophysical Survey, Hebei Province, China, from whole-rock samples by using combined magnetic separation and heavy liquid separation. Zircon grains, together with zircon standards Plešovice and Qinghu were mounted in epoxy mounts, which were then polished to section the crystals in half for analysis. All zircons were documented with transmitted and reflected light micrographs as well as cathodoluminescence (CL) images to reveal their internal structures, and the mount was vacuum-coated with high-purity gold prior to secondary ion mass spectrometry (SIMS) analysis.

Measurements of U–Pb isotopes were performed using a Cameca IMS 1280 ion microprobe at the Institute of Geology and Geophysics, Chinese Academy of Sciences, following analytical procedures described by Li et al. (Reference Li, Liu, Li, Guo and Chamberlain2009). The O2 − primary ion beam with an intensity of c. 8 nA was used to produce even sputtering over the entire analysed area of about 20×30 μm. A single electron multiplier was used in ion-counting mode to measure secondary ion beam intensities by peak jumping. U–Pb ratios and absolute abundances were determined relative to the standard zircon Plešovice (206Pb/238U = 0.05369, corresponding to 337.1 Ma; Sláma et al. Reference Sláma, Košler, Condon, Crowley, Gerdes, Hanchar, Horstwood, Morris, Nasdala, Norberg, Schaltegger, Schoene, Tubrett and Whitehouse2008). Correction of common lead was made by measuring 204Pb. The average present-day crustal Pb composition (Stacey & Kramers, Reference Stacey and Kramers1975) is used for the common Pb assuming that it is largely due to surface contamination introduced during sample preparation. Uncertainties on individual analyses in the data tables are reported at the 1σ level; mean ages for pooled U–Pb analyses are quoted with a 95% confidence interval. Data reduction was carried out using the Isoplot/Ex v. 2.49 program (Ludwig, Reference Ludwig2001). SIMS zircon U–Pb age data are given in Table 1.

Table 1. SIMS zircon U–Pb data for the Lower Cretaceous granitoids in the central part of the Great Xing’an Range

* Note: f206* is the percentage of common 206Pb in the total 206Pb

3.b. Major and trace element analysis

After petrographic examination, a total of 17 fresh samples were selected, crushed and powdered in an agate mill to ~ 200 mesh. Major and trace element analysis of the samples was conducted at two different laboratories: (1) samples 12GW102–12GW106 were measured at the State Key Laboratory of Continental Dynamics of Northwest University; and (2) samples GW04190–GW04198 and GW04369–GW04373 were analysed at the Key Laboratory of Geochronology and Geochemistry, Guangzhou Institute of Geochemistry, Chinese Academy of Sciences. Major element compositions were determined by X-ray fluorescence (XRF; Rigaku RIX 2000 spectrometer) using fused-glass discs. The analytical uncertainties are generally better than 5% for all major elements. Trace element composition analysis in the two different laboratories was determined by inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (ICP-MS) (Elan 6100 DRC and Elan 6000 DRC, respectively). About 50 mg of powdered samples were dissolved in Teflon bombs using a HF+HNO3 mixture. The signal drift of the spectrometer was monitored by an internal standard Rh solution. The international standards BHVO-1, AGV-1 and BCR-1 were chosen to calibrate element concentration of measured samples. Analytical uncertainties are in the range of 1–3%. The analytical results for the international standards (BHVO-1, AGV-1 and BCR-1) indicated that the analytical precision was better than 5% for major elements and 10% for trace and rare earth elements (REEs) (Liu, Liu & Li, Reference Liu, Liu and Li1996; Rudnick et al. Reference Rudnick, Gao, Ling, Liu and McDonough2004; Liu et al. Reference Liu, Liu, Hu, Diwu, Yuan and Gao2007). The operational and calibrated procedures for the major and trace element analyses are similar to those detailed by Li et al. (Reference Li, Sun, Wei, Liu, Lee and Malpas2000, Reference Li, Qi, Liu, Liang, Tu, Xie and Yang2005).

3.c. Hf isotope analyses

In situ zircon Hf isotopic analyses were carried out at the Institute of Geology, Chinese Academy of Sciences (Beijing), with a Neptune MC-ICP-MS with an ArF excimer laser ablation system. During analyses, spot sizes of 63 μm and a laser repetition rate of 10 Hz with 100 mJ were used. The international standard zircon 91500 (176Hf/177Hf ratio = 0.282307±0.000031) from Harvard University was chosen to monitor the instrument status and correct for external parts of samples. Detailed analytical procedures and instrument parameters can be found in Wu et al. (Reference Wu, Yang, Xie, Yang and Xu2006).

4. Analytical results

4.a. Zircon U–Pb ages

In this study, four samples collected from the above three granitic plutons in the central Great Xing’an Range were chosen for zircon U–Pb dating by SIMS. The CL images of representative zircons are shown in Figure 4 and the U–Pb data plotted on concordia diagrams in Figure 5.

Figure 4. Representative cathodoluminescence (CL) images of zircons from the Mingshui, Jilasitainangou and Suolunjunmachang granitoids. The yellow circles indicate the analytical areas for SIMS U–Pb dating. The size of the circles is 20×30 μm.

Figure 5. Zircon SIMS U–Pb concordia diagrams for the Mingshui (a, b), Jilasitainangou (c) and Suolunjunmachang (d) plutons in the central part of the Great Xing’an Range. The concordia age and MSWD are shown in each figure.

Zircons from these samples are light-pink, transparent and euhedral–subhedral in shape. In the CL images most zircons are prismatic to short-prismatic with fine-scale oscillatory growth zoning (Fig. 4). Most of them have high Th/U ratios ranging from 0.34 to 2.10 (Table 1). We interpret these zircons to be of igneous origin (Pupin, Reference Pupin1980; Koschek, Reference Koschek1993).

4.a.1. Mingshui pluton

Sample 12GW104 is an alkali feldspar granite collected from the Mingshui pluton (location: 46°42′09.9″N, 121°50′52.2″E). Fourteen analyses of 14 zircons were obtained during a single analytical session (Table 1). The analysed zircons have moderate U (153–785 ppm) and Th (136–854 ppm) concentrations. Th/U ratios mostly cluster around 0.73–1.65. Values of f206 range from 0.07 to 1.57. Ratios of 206Pb/208U and 207Pb/235U agree internally to within analytical precision (Fig. 5a) and yield a concordia age of 133.6±1.1 Ma (MSWD of concordance = 0.15).

Sample 12GW105 is also an alkali feldspar granite collected from the Mingshui pluton (location: 46°42′10.5″N, 121°50′35.9″E). Thirteen U–Pb isotopic analyses were conducted on 13 zircons (Table 1). Concentrations of U range from 144 to 1189 ppm, and Th from 130 to 1754 ppm. Th/U ratios vary between 0.63 and 1.85. Values of f206 are 0.10–0.84. All the 206Pb/208U and 207Pb/235U analyses are concordant within analytical errors (Fig. 5b). They yield a concordia age of 134.3±1.2 Ma (MSWD of concordance = 2.1).

Samples 12GW104 and 12GW105, which were both collected from the Mingshui pluton, yield ages of 133.6±1.1 Ma and 134.3±1.2 Ma, respectively. There appears to be a small age difference between the two samples, but the two ages marginally overlap within errors. Considering the external uncertainly of c. 0.7% for the SIMS U–Pb age determination (for Mesozoic or older samples) and the similar lithologies of the two dated rocks, we favour the grand weighted mean of the 206Pb–238U age of 133.9±1.1 Ma as the best estimate of the crystallization age for the Mingshui pluton.

4.a.2. Jilasitainangou pluton

Sample GW04190 is an alkali feldspar granite collected from the Jilasitainangou pluton (location: 46°36′29.9″N, 120°53′55.2″E). Fifteen analyses of 15 zircons were obtained during a single analytical session (Table 1). Uranium and Th concentrations vary from 355 to 1061 ppm and from 211 to 1807 ppm. Th/U ratios range from 0.59 to 2.10. Values for f206 are 0.03–0.35. All the measured Pb/U ratios are concordant within analytical errors (Fig. 5c), yielding a concordia age of 135.9±1.1 Ma (MSWD of concordance = 3.8). This age is interpreted as the best estimate of the crystallization age of sample GW04190.

4.a.3. Suolunjunmachang pluton

Sample GW04369 is an alkali feldspar granite collected from the Suolunjunmachang pluton (location: 46°40′57.9″N, 121°13′10.9″E). Fourteen analyses were performed on 14 zircons in a single analytical session (Table 1). Concentrations of U range from 288 to 1689 ppm, and Th from 105 to 744 ppm. Th/U ratios vary between 0.34 and 0.81. Values for f206 are 0.04–1.73. All the 206Pb/208U and 207Pb/235U analyses are concordant within analytical errors (Fig. 5d). They yield a concordia age of 133.6±1.1 Ma (MSWD of concordance = 2.4), which is interpreted as the best estimate of the crystallization age of sample GW04369.

4.b. Geochemistry

4.b.1. Major and trace elements

The results of major and trace element analyses are presented in Table 2. All the alkali feldspar granite samples from the three plutons are high in silica and alkalis, with SiO2 ranging from 74.49 to 78.03 wt% and total K2O+Na2O varying from 8.17 to 9.20 wt% (Table 2). They all plot within the high-K calc-alkaline field in the K2O versus SiO2 diagram (Fig. 6a; Peccerillo & Taylor, Reference Peccerillo and Taylor1976). The granites are peraluminous with A/CNK (molar ratio of Al2O3/(CaO+Na2O+K2O)) and A/NK ratios ranging from 0.99 to 1.13 and 1.05 to 1.18, respectively (Fig. 6b; Maniar & Piccoli, Reference Maniar and Piccoli1989). They have lower total Fe2O3 (0.68–2.07 wt%), MnO (0.01–0.15 wt%), MgO (0.05–0.24 wt%), CaO (0.06%–0.47 wt%), TiO2 (0.09–0.41 wt%) and P2O5 (< 0.05 wt%) contents (Table 2).

Table 2. Major (wt%) and trace elements (ppm) of the Lower Cretaceous granitoids from the central part of the Great Xing’an Range

* Note: Samples 12GW102–12GW106 were measured at the State Key Laboratory of Continental Dynamics of Northwest University.

Samples GW04190–GW04198 and GW04369–GW04373 were analysed at the Key Laboratory of Geochronology and Geochemistry, Guangzhou Institute of Geochemistry, Chinese Academy of Sciences. MS – Mingshui pluton; JLSTNG – Jilasitainangou pluton; SLJMC – Suolunjunmachang pluton.

Figure 6. (a) SiO2 versus K2O diagram (after Peccerillo & Taylor, Reference Peccerillo and Taylor1976) showing the granites plot in the high-K calc-alkaline granite field, and (b) A/CNK versus A/NK diagram (after Maniar & Piccoli, Reference Maniar and Piccoli1989) showing the peraluminous character of the Mingshui, Jilasitainangou and Suolunjunmachang plutons.

Chondrite-normalized REE patterns of the granite samples (Fig. 7a–c; Boynton, Reference Boynton and Henderson1984) invariably show a relative enrichment in light rare earth elements (LREEs), with (La/Yb)N ratios of 4.16–14.6 and significant negative Eu anomalies. In the PM (primary mantle)-normalized spidergrams (Fig. 7d–f; Sun & McDonough, Reference Sun, McDonough, Saunders and Norry1989), all of the samples show negative anomalies in Ba, Nb, Ta, Sr and Eu and are enriched in Rb, U, Th, LREEs, Zr and Hf.

Figure 7. (a–c) Chondrite-normalized REE patterns (chondrite-normalized values after Boynton, 1984). Note that all the granites show negative Eu and enrichment in LREEs and depletion in HREEs. (d–f) Primitive mantle-normalized trace element patterns (primitive mantle-normalized values after Sun & McDonough, Reference Sun, McDonough, Saunders and Norry1989). A common feature of all samples is significant depletion in Ba, Nb, Ta, Sr and Eu.

4.b.2. Zircon Hf isotopes

In situ Hf isotopic analyses of zircons for two samples are listed in Table 3. Twenty-five spot analyses were obtained for zircons from sample 12GW104, giving initial 176Hf/177Hf ratios ranging from 0.282889 to 0.283003 with a weighted average of 0.282947±0.000014 (MSWD = 2.7) (Fig. 8a). The ε Hf(t) values are between +7.02 and +10.94, and the Hf two-stage model ages (TDM2) range from 638 to 998 Ma (Table 3). Twenty-three spot analyses were made for zircon grains from sample 12GW106. Except for one stray spot (spot 12GW106–17 with an initial 176Hf/177Hf ratio of 0.283161, ε Hf(t) value of 16.23 and TDM2 value of 151 Ma), the rest have initial 176Hf/177Hf ratios varying from 0.282876 to 0.283106 with a weighted average of 0.282967±0.000023 (MSWD = 3.4, n = 22) (Fig. 8b), and their corresponding ε Hf(t) values vary from +6.42 to +14.42, and TDM2 values range from 316 to 1044 Ma (Table 3).

Table 3. Zircon Lu–Hf isotopic data for the Lower Cretaceous granitoids in the central part of the Great Xing’an Range

Figure 8. Characteristics of Hf isotopes for the Lower Cretaceous granites. The weighted mean 176Hf/177Hf and MSWD are shown in each figure.

5. Discussion

5.a. Lower Cretaceous granitic magmatism in the central Great Xing’an Range

From available geochronological data (Ge et al. Reference Ge, Wu, Zhou and Zhang2005; Wu et al. Reference Wu, Sun, Ge, Zhang, Grant, Wilde and Jahn2011), the granitic magmatism in the central part of the Great Xing’an Range has been divided into three stages, i.e. Middle to Upper Triassic (235–225 Ma), Lower to Middle Jurassic (182–175 Ma) and Lower Cretaceous (140–125 Ma). However, most of these geochronological data were obtained for granitic rocks from the Ulanhot–Suolun area located in the south of the study region of this paper, and few studies have been carried out on the Mingshui–Jilasitai–Junmachang area. The MS, JLSTNG and SLJMC plutons were previously regarded as Lower Cretaceous in age on the basis that these plutons intrude the Upper Jurassic Mannitu Formation (IMBGMR, 1990), and were not well constrained by precise zircon ages. Thus, the crystallization ages of these three granitic intrusions still remained unknown before this study.

CL images of zircons from these plutons (Fig. 4) indicate that the euhedral and subhedral zircons are of magmatic origin, which is also suggested by their high Th/U ratios of 0.34–2.10 (Table 1). Therefore, the new SIMS U–Pb zircon dating results can provide rigorous constraints on the timing of granitic magmatism in the central Great Xing’an Range. The concordia ages of the MS, JLSTNG and SLJMC plutons are 133.6±1.1 Ma and 134.3±1.2 Ma, 135.9±1.1 Ma, and 133.6±1.1 Ma, respectively (Fig. 5), indicating that these plutons were nearly coevally emplaced during Lower Cretaceous time.

In recent years, it has been recognized that Lower Cretaceous granitoids are widespread throughout the central part of the Great Xing’an Range, including the 136–134 Ma Qingshan pluton, 125±2 Ma Suolunzhen pluton and 128–127 Ma Yonghetun pluton in the Ulanhot–Suolun section (Fig. 2; Ge et al. Reference Ge, Wu, Zhou and Zhang2005), and the 131±1 Ma Wulanmaodu pluton, 120±2 Ma Fengshou pluton, 120±1 Ma Caishichangxi pluton and 119±1 Ma Shenshan pluton in the Zhalaiteqi section (Fig. 2; Wu et al. Reference Wu, Sun, Ge, Zhang, Grant, Wilde and Jahn2011). This conclusion is also be supported by the Lower Cretaceous granitic intrusions in the Chaihe section (Wang et al. Reference Wang, Xu, Liu and Zhou2012). The recognition of these Lower Cretaceous granitic plutons, together with the widespread coeval volcanic rocks in the study area and adjacent regions (Zhang et al. Reference Zhang, Gao, Ge, Wu, Yang, Wilde and Li2010), demonstrates the existence of a huge Lower Cretaceous igneous event in the central part of the Great Xing’an Range.

5.b. Genetic type of the Lower Cretaceous granites

Since Loiselle & Wones (Reference Loiselle and Wones1979) coined the term ‘A-type granite’, granitoids have been further subdivided into I-type, S-type, M-type and A-type based on the nature of their protoliths (Chappell & White, Reference Chappell and White1974; Pitcher, Reference Pitcher1997). During the last decade, a great deal of discussion has revolved around the question of what criteria should be used to distinguish between A-type and other types of granitoids. Although distinction between them is not always straightforward, A-type granites are generally relatively enriched in high-field-strength elements (HFSEs), such as Zr, Nb, Y, REEs and Ga.

The results of the major and trace element analyses (Table 2) show that the three plutons in the central part of the Great Xing’an Range have similar geochemical characteristics, which are closely similar to those of A-type granites and highly fractionated I-type granites (Chappell, Reference Chappell1999; Wu et al. Reference Wu, Sun, Li, Jahn and Wilde2002, Reference Wu, Jahn, Wilde, Lo, Yui, Lin, Ge and Sun2003; Xiao et al. Reference Xiao, Li, Liu, Wang, Yang, Chen and Xu2014). They have high SiO2 and Na2O+K2O with relatively low CaO, Fe2O3, TiO2, MnO, MgO and P2O5 contents. Chondrite-normalized REE patterns show that they are obviously enriched in LREEs and depleted in heavy rare earth elements (HREEs), and have strongly negative Eu anomalies (Fig. 7a–c). The PM-normalized trace element diagrams (Fig. 7d–f) show that they are enriched in Rb, U, Th, Zr, Hf and Nd, and depleted in Ba, Nb, Ta, Sr and Eu, with Sr ranging from 4.20 to 68.7 ppm (< 100 ppm; Zhang, Q. et al. Reference Zhang, Wang, Pan, Li and Jin2008). The average 10000 Ga/Al ratios of the MS, JLSTNG and SLJMC plutons are 2.70, 3.06 and 2.81, respectively, which are a little lower than the global average ratio of 3.75 for A-type granites (Whalen, Currie & Chappell, Reference Whalen, Currie and Chappell1987). However, they are all greater than the minimum value of 2.6 for A-type granites and the values of I-type and S-type granites (2.1 and 2.28, respectively; Whalen, Currie & Chappell, Reference Whalen, Currie and Chappell1987). As proposed by Whalen, Currie & Chappell (Reference Whalen, Currie and Chappell1987), in the discrimination diagrams of Zr, Nb, K2O/MgO and K2O+N2O versus 10000 Ga/Al (Fig. 9a–d) and (K2O+Na2O)/CaO versus (Zr+Nb+Ce+Y) (Fig. 9e), most of these granites fall into the field of A-type granites. However, in the 10000 Ga/Al versus (Zr+Nb+Ce+Y) diagram (Fig. 9f, after Eby, Reference Eby1990), most of these granites fall into the highly fractionated I-type field. Obviously, the genetic type of these granites is still ambiguous based only on the discrimination diagrams.

Figure 9. Discrimination diagrams of (a) Zr versus 10000 Ga/Al; (b) Nb versus 10000 Ga/Al; (c) K2O/MgO versus 10000 Ga/Al; (d) (K2O+Na2O) versus 10000 Ga/Al; (e) (K2O+Na2O)/CaO versus Zr+Nb+Ce+Y and (f) 10000 Ga/Al versus Zr+Nb+Ce+Y for the Lower Cretaceous granites (after Whalen, Currie & Chappell Reference Whalen, Currie and Chappell1987; Eby, Reference Eby1990). Abbreviations: FG – highly fractionated I-type; OGT – unfractionated I, S and M-type.

On the other hand, the concentrations of Zr of these alkali feldspar granites range from 135 to 626 ppm (Table 2). Only one sample is high in Zr (up to 626 ppm), whilst the others have Zr contents mostly between 100 and 240 ppm, which are lower than the Zr contents of the typical A-type granites (Li, Yu & Chen, Reference Li, Yu and Chen1994; Wang & Zhao, Reference Wang and Zhao1997; Jahn et al. Reference Jahn, Wu, Capdeviala, Fourcade, Wang and Zhao2001; Wu et al. Reference Wu, Sun, Li, Jahn and Wilde2002; Yang et al. Reference Yang, Wu, Chung, Wilde and Chu2006a ). This phenomenon indicates that most of the granites have a much lower zircon-saturation temperature. However, as we know, A-type granites are usually formed under high-temperature and low-pressure conditions (Collins et al. Reference Collins, Beams, White and Chappell1982; Clemens, Holloway & White, Reference Clemens, Holloway and White1986). Therefore, it is proposed that the granites in the present study should be classified as I-type granites. This conclusion is also confirmed by the criteria of Sylvester (Reference Sylvester1989) using the diagram of (Al2O3+CaO)/(FeO*+Na2O+K2O) versus 100 (MgO+FeO*+TiO2)/SiO2 (Fig. 10a), in which samples all plot in the field of the highly fractionated calc-alkali series. Furthermore, Th and Y concentrations of the samples increase with increasing magmatic fractionation (Fig. 10b, c), also showing an I-type trend. Based on all the data mentioned above, we thus conclude that the Lower Cretaceous alkali feldspar granites studied in this paper are highly fractionated I-type granites.

Figure 10. (a) (Al2O3+CaO)/(FeO*+Na2O+K2O) versus 100(MgO+FeO*+TiO2)/SiO2 diagram (after Sylvester, Reference Sylvester1989); (b) Th versus Rb and (c) Y versus Rb diagrams (after Chappell, Reference Chappell1999) showing the highly fractionated I-type nature of the granites. SA – subalkaline type; HFS – highly fractionated and subalkaline type; HP – highly peraluminous type; ALK – alkaline type.

5.c. Source characteristics of the granites and crustal accretion

All the alkali feldspar granites described in this paper formed nearly coevally and have similar petrological, geochemical and zircon Hf isotopic compositions, indicating a common source. As discussed above, the alkali feldspar granites are high in silica and alkalis, and low in Nb, Ta and Eu contents, which, together with the geochemical features of the transition elements, suggests that these granites were derived from the partial melting of a crustal source (Taylor & McLennan, Reference Taylor and McLennan1985; Hofmann, Reference Hofmann1988; Wu et al. Reference Wu, Li, Yang and Zheng2007; Zhang, Q. et al. Reference Zhang, Wang, Pan, Li and Jin2008). Geochemically, all of these granites belong to peraluminous and highly fractionated calc-alkaline I-type granites. Besides, they display an enrichment in LREEs and a depletion in HREEs, with significantly negative Eu anomalies (Fig. 7a–c). These characteristics imply that the source of the magma is intermediate–basic igneous rock (Chappell & White, Reference Chappell and White1974; Roberts & Clemens, Reference Roberts and Clemens1993) with plagioclase, but without garnet, in the residue, which, together with the presence of a miarolitic texture, indicates that they were possibly derived from an intermediate–basic crustal source at low pressure. Moreover, all the zircons from the three plutons have relatively positive ε Hf(t) values varying from +6.42 to +14.42 with Hf model ages (TDM2) of 1044–316 Ma (Table 3). The fact that all data spots plot between the depleted mantle and chondrite line in the ε Hf(t) versus t diagram (Fig. 11, after Yang et al. Reference Yang, Wu, Shao, Wilde, Xie and Liu2006b ) far away from the ancient crustal evolution lines, suggests that the magma source was juvenile crustal material of Neoproterozoic to Phanerozoic age mainly derived from depleted mantle. All of the analysed zircons have similar Hf isotopic features to those of zircons from the Phanerozoic igneous rocks in the eastern segment of the CAOB (Fig. 11; Wu & Sun, Reference Wu and Sun1999; Jahn, Wu & Chen, Reference Jahn, Wu and Chen2000; Yang et al. Reference Yang, Wu, Shao, Wilde, Xie and Liu2006b ; Sui et al. Reference Sui, Ge, Wu, Zhang, Xu and Chang2007), but are distinct from those of Phanerozoic igneous rocks in the North China Craton (Yang et al. Reference Yang, Wu, Shao, Wilde, Xie and Liu2006b ). Taken together, we propose that the primary magma of the alkali feldspar granites originated from the partial melting of a Neoproterozoic–Phanerozoic juvenile intermediate–basic crustal source at low pressures.

Figure 11. Plot of εHf(t) versus t (Ma) for the zircons from the Lower Cretaceous granites. CAOB – the Central Asian Orogenic Belt; YFTB – the Yanshan Fold and Thrust Belt (Yang et al. Reference Yang, Wu, Shao, Wilde, Xie and Liu2006b ).

In recent years, a great deal of zircon Hf isotopic data from the study area and adjacent regions have been published, which makes it possible to decipher the major period of crustal accretion in the Great Xing’an Range. Firstly, Zhou, Ge & Wang (Reference Zhou, Ge and Wang2011) have done a detailed geochemical study on the upper Mesozoic granitic rocks in the Ulanhot region, and their results show that the Qingshan, Suolun and Yonghetun plutons have positive εHf(t) values of +6.14 to +10.22, +7.76 to +10.69 and +5.82 to +8.95, respectively, with corresponding TDM2 values of 535–796 Ma, 497–685 Ma and 683–814 Ma, respectively. Furthermore, the εHf(t) and TDM2 values for the upper Mesozoic comendite in the southern Great Xing’an Range vary from +9.07 to +12.08 and 415 to 616 Ma, respectively (Wang, He & Xu, Reference Wang, He and Xu2013). All of these data indicate that the igneous rocks in the mid-southern part of the Great Xing’an Range have similar zircon Hf isotopic compositions with highly positive εHf(t) values (+5.82 to +14.42) and relatively young Hf two-stage model ages of 1044–316 Ma, suggesting that the Neoproterozoic to Phanerozoic was an important period for crustal accretion in the mid-southern part of the Great Xing’an Range.

5.d. Tectonic implications

As mentioned above, I- and A-type granites are widely distributed in NE China (Wu et al. Reference Wu, Sun, Ge, Zhang, Grant, Wilde and Jahn2011), and can be divided into three major episodes: the Permian, Upper Triassic to Lower Jurassic, and Lower Cretaceous (Fig. 2), of which the Lower Cretaceous A-type granites were previously considered to have only been emplaced in the eastern margin of the Great Xing’an Range, as exemplified by the Nianzishan and Baerzhe plutons. The Nianzishan alkaline granite (K–Ar age of 123 Ma) in Heilongjiang Province was considered to have been emplaced within a depression basin (Li & Yu, Reference Li and Yu1993; Wei et al. Reference Wei, Zheng, Zhao and Valley2002), while the Baerzhe alkaline granite (Rb–Sr age of 125 Ma) in Inner Mongolia was considered to have formed in a rift environment (Wang & Zhao, Reference Wang and Zhao1997; Jahn et al. Reference Jahn, Wu, Capdeviala, Fourcade, Wang and Zhao2001; Yang et al. Reference Yang, Niu, Shan, Sun, Zhang, Li, Jiang and Yu2013). Wu et al. (Reference Wu, Sun, Li, Jahn and Wilde2002) summarized that this episode of granites belong to an A1 subgroup and are anorogenic, possibly related to extension following lithospheric delamination in eastern China associated with the subduction of the Pacific Plate in Upper Mesozoic time. An anorogenic extensional environment is also supported by the presence of the coeval intraplate-related comendite in Aliwula in the southern Great Xing’an Range (Wang, He & Xu, Reference Wang, He and Xu2013) and the A-type Chaihelinchang syenogranites (zircon U–Pb age of 133±3 Ma) in the central part of the Great Xing’an Range (Wang et al. Reference Wang, Xu, Liu and Zhou2012). Taken together, we conclude that the anorogenic extensional setting did exist in the eastern margin of the Great Xing’an Range during Lower Cretaceous time. On the other hand, the highly fractionated I-type granites described in this study were formed during 133–136 Ma, which is a little older than the coeval A-type granites (120–133 Ma). Therefore, two questions can be posed: were these highly fractionated I- and A-type granites emplaced in the same tectonic environment and what were the deep geodynamic processes that controlled their emplacement across the central and eastern parts of the Great Xing’an Range?

Based on progressive variations in ages of volcanic rocks from the whole Great Xing’an Range, Zhang et al. (Reference Zhang, Gao, Ge, Wu, Yang, Wilde and Li2010) proposed a broad subduction-induced migrating delamination model to explain the geodynamic setting of the Mesozoic super-large magmatic events in eastern China, which can also be applied to the Lower Cretaceous highly fractionated I-type granites in this study. It is generally thought that the onset of subduction of the Palaeo-Pacific plate may have occurred in Jurassic time, which caused crustal shortening and thickening, forming the westward-younging trend of the granites. During Upper Jurassic time, the westward flat subduction of the Palaeo-Pacific plate reached its peak and changed direction to the north or northwest (Maruyama, Reference Maruyama1997; Sagong & Kwon, Reference Sagong and Kwon2005; Zhang et al. Reference Zhang, Gao, Ge, Wu, Yang, Wilde and Li2010). This was followed by a change in tectonic setting from compression to extension across the whole region, leading to the large-scale delamination of the thickened crust, and the initiation of steep subduction. During Lower Cretaceous time, the delamination reached its peak (Wu et al. Reference Wu, Lin, Wilde, Zhang and Yang2005), causing voluminous magmatism across the whole of NE China and adjacent regions (Wu et al. Reference Wu, Lin, Wilde, Zhang and Yang2005; Zhang et al. Reference Zhang, Gao, Ge, Wu, Yang, Wilde and Li2010). The timing of the peak delamination of the thickened crust was coincident with the emplacement of the A1-type (120–133 Ma) granites mentioned above, but slightly younger than that of the highly fractionated I-type granites studied in the paper (133.6–135.9 Ma). Hence, we propose that the highly fractionated I-type granites were firstly generated during upwelling of the asthenosphere, and when the delamination reached its peak, the A-type granites formed subsequently. All the evidence leads us to conclude that the two types of granites experienced a common geodynamic mechanism: i.e. both of them were emplaced in an extensional environment induced by delamination of the lithosphere that arose from the subduction of the Palaeo-Pacific plate beneath the Euro-Asian plate.

6. Conclusions

-

(1) SIMS zircon U–Pb age data indicate that the Mingshui, Jilasitainangou and Suolunjunmachang plutons of the central part of the Great Xing’an Range formed in Lower Cretaceous time (133.6–135.9 Ma).

-

(2) The Lower Cretaceous alkali feldspar granites in the central part of the Great Xing’an Range belong to peraluminous and highly fractionated calc-alkaline I-type granites and their primary magmas were derived from the partial melting of a Neoproterozoic–Phanerozoic juvenile intermediate–basic crustal source at low pressure.

-

(3) The Lower Cretaceous highly fractionated I-type granites in the central part of the Great Xing’an Range were emplaced in an extensional environment induced by delamination of the lithosphere that arose from the subduction of the Palaeo-Pacific plate beneath the Euro-Asian plate.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the staff of the Institute of Geology and Geophysics, Chinese Academy of Sciences, for their advice and assistance during SIMS U–Pb zircon dating. This work was financially supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (41272076, 41190075 and 41190070).