1. Introduction

It is now generally appreciated that the Palaeozoic biodiversification of invertebrate animals did not just peak in the radiations of early Cambrian time (the Cambrian Explosion) and during the Ordovician Period, the Great Ordovician Biodiversification Event of Webby et al. (2004), but proceeded reasonably steadily from early Cambrian time up to near the end of the Ordovician Period (Harper et al. Reference Harper, Cascales-Miñana and Servais2020). During the Early Ordovician Epoch, the major continents were well separated by substantial oceans (Fig. 1), and that allowed the development of several distinct faunal provinces, as reviewed by Fortey & Cocks (Reference Fortey and Cocks2003). It also meant that the radiation rates differed between the different major areas at different times; for example, the curves shown by Fan et al. (Reference Fan, Shen, Erwin, Sadler, MacLeod, Cheng, Hou, Yang, Wang, Wang and Zhang2020), based largely on Chinese data, have highs and lows at different times from those shown in Harper & Servais (2013), which gathered data from all parts of the world. Nevertheless it is clear that the number of brachiopod genera approximately doubled between the beginning of the Ordovician Period and the end of the Dapingian Age only 20 Ma later.

Fig. 1. Palaeogeography of Gondwana during Early Ordovician time (480 Ma), showing the chief brachiopod localities within the higher latitudes analysed in this paper. Base map modified from Cocks & Torsvik (Reference Cocks and Torsvik2020). 1, Bohemia; 2, Moldanubia; 3, Armorica; 4, Iberia; 5, 6, NE Africa (Ougarta Range, Anti-Atlas Mountains); 7, East Avalonia; 8, West Avalonia (Acadia); 9, Serbia; 10, Alborz-Kopet-Dagh; 11, Central Andean Basin (Colorado); 12–14, Baltica continent; 12, South Urals; 13, Ingria, Russia and North Estonia; 14, Holy Cross Mountains, Poland; ATA, Armorican Terrane Assemblage; CI, northeastern central Iran platform; PGZ (and red lines), Jason and Tuzo plume generation zones.

The best known of those benthic faunas from the higher latitudes are chiefly brachiopods and trilobites, and the latter made up a calymenacean–dalmanitacean (formerly Neseuretus) Province in the Early Ordovician Epoch (Cocks & Fortey, Reference Cocks and Fortey1990; Fortey & Cocks, Reference Fortey and Cocks2003). The brachiopods were largely within the Mediterranean Province, and the chief aim of this paper is to reidentify those Mediterranean faunas, to compare the individual sites statistically to gain a more nuanced overall picture of the integrity of the province, and to see how the assemblages that make up the province changed from the early Tremadocian Age to the end of the Dapingian Age (during 487–469 Ma). We have also revised some of the contemporary benthic brachiopod faunas on the neighbouring continent of Baltica, whose centre drifted speedily from 45° S to 30° S during that period (Torsvik & Cocks, Reference Torsvik and Cocks2017), in order to compare and contrast that Baltic Province and its changes with the Mediterranean Province.

The Mediterranean Province is only known from the higher southern latitudes of the world since the comparable high latitudes surrounding the North Pole were entirely covered by the very extensive Panthalassic Ocean; any possible land areas, and therefore their surrounding benthic faunas within it, are quite unknown. The Province continued on into later Ordovician time (late Darriwilian – early Katian) with other characteristic but different brachiopod genera, such as Tissintia, but that later history is not considered in detail here.

Spjeldnaes (Reference Spjeldnaes1961) originally introduced the term ‘Mediterranean Province’ for a distinctive cooler Ordovician climatic zone, a concept that pre-dated the awareness of plate tectonics. However, later authors (e.g. Havlíček & Vanĕk, Reference Havlíček and Vanĕk1966) used it as the name of a faunal province, which we follow here, although the Mediterranean Province was called the ‘High-latitude Province’ by Harper et al. (Reference Harper, Rasmussen, Liljeroth, Blodgett, Candela, Jin, Percival, Rong, Villas and Zhan2013). The Early Ordovician Epoch of previous general usage included the Tremadoc and Arenig ages, but the Tremadoc is now known as the Tremadocian Age and the Arenig has now been replaced by the Floian, Dapingian and earliest part of the Darriwilian ages in the international system of stratigraphical nomenclature (Bergström et al. Reference Bergström, Chen, Gutiérrez-Marco and Dronov2009).

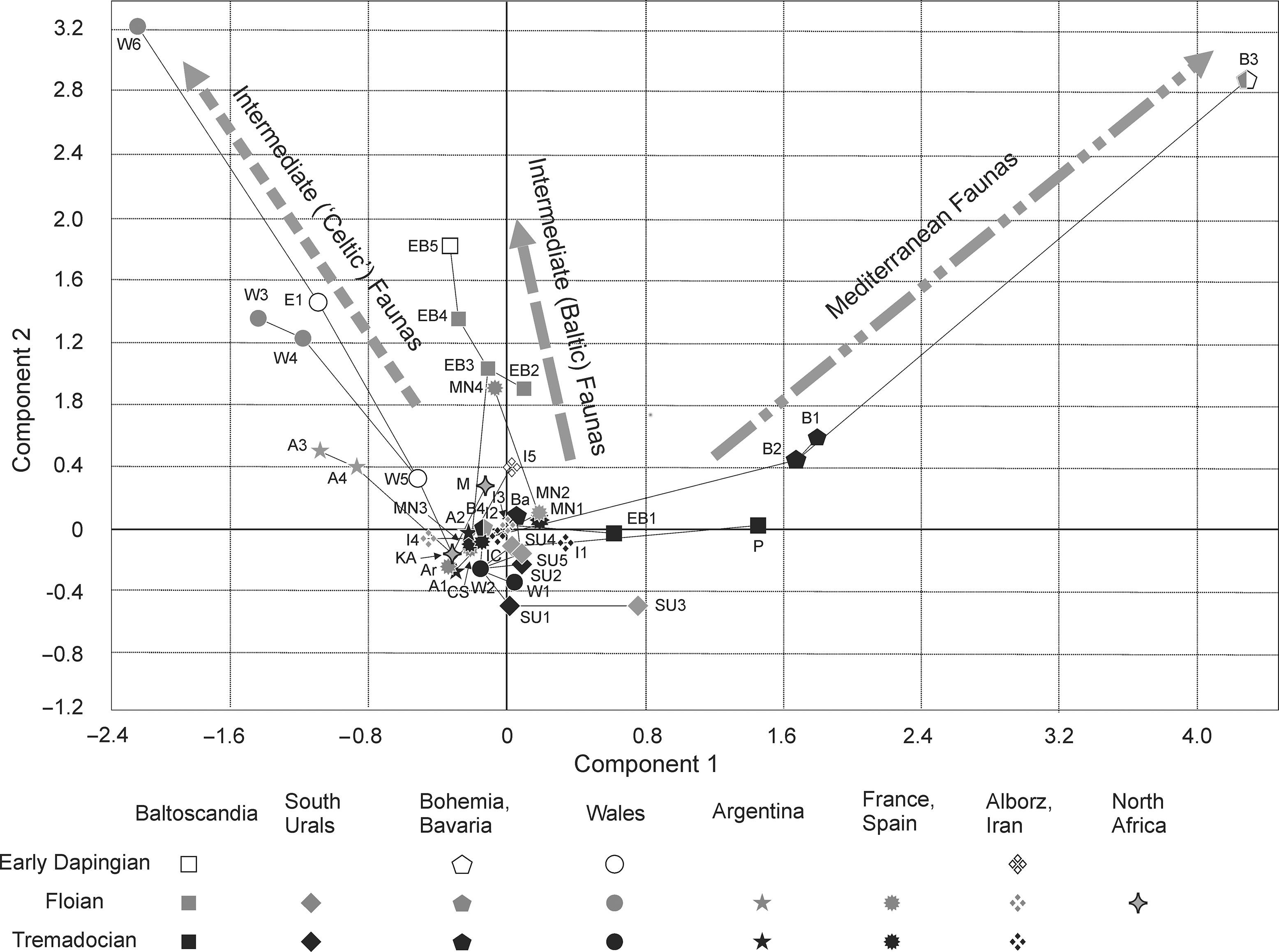

The faunas analysed here date from the Tremadocian, Floian and Dapingian ages, and their sample identifying letters (e.g. B1) are to be found in the rest of this paper as well as in Tables 1–3 and Figures 2, 3. The relevant areas and their brachiopods are now briefly reviewed in turn.

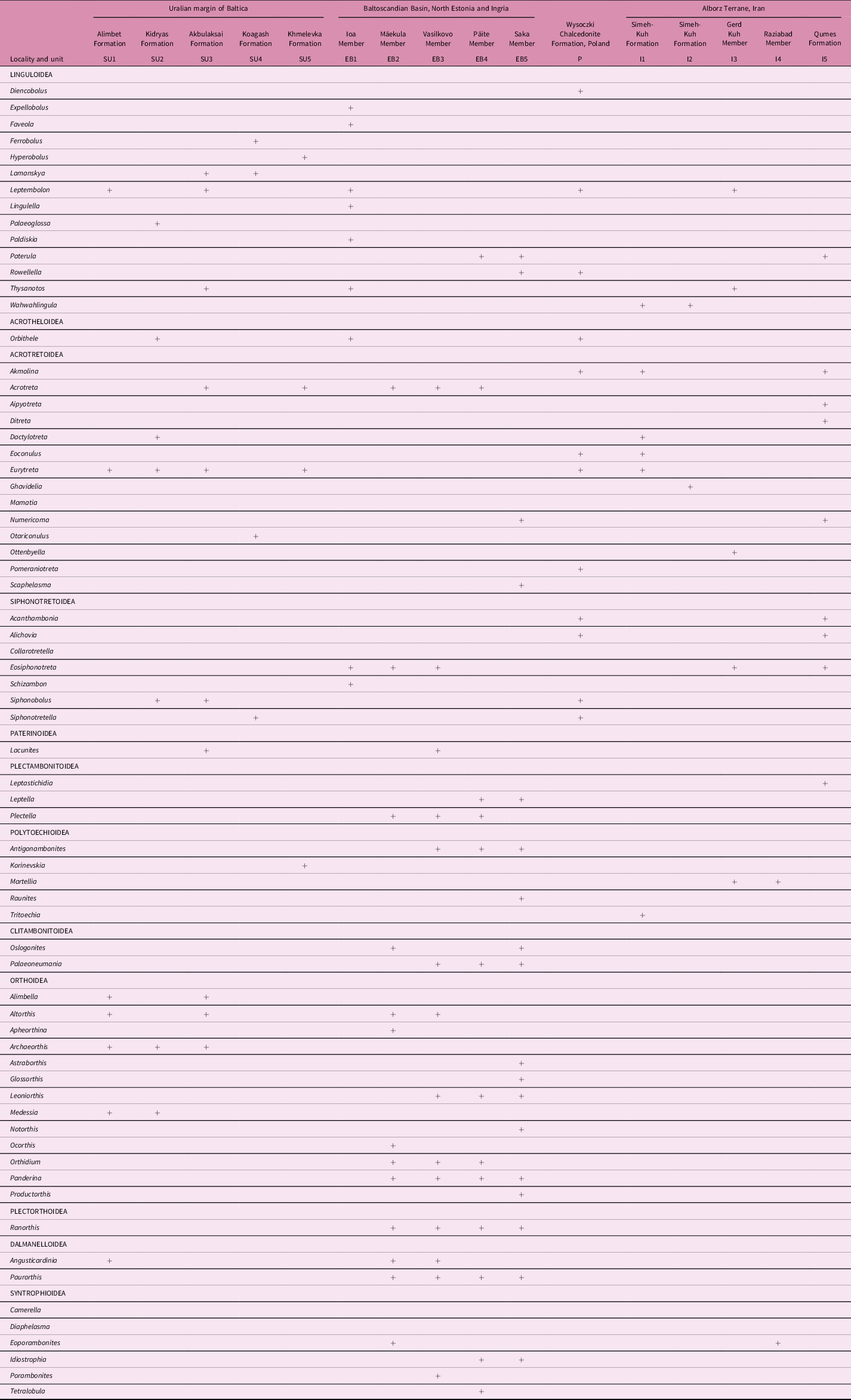

Table 1. Mediterranean Province brachiopod genera of Tremadocian age, which are largely from latitudes of > 70° N and within the Armorican Quartzite facies

a Including the Breadstone, Dol-cyn-afon and Micklewood formations and shales at Cwm Cry (from Sutton et al. Reference Sutton, Bassett and Cherns1999, 2000).

b Mainly from the Shineton Shale Formation, Shropshire, Welsh Borderland.

c The Valconch Formation to lower part of the Borrach Formation.

d Unnamed Upper Tremadoc sandstone within Salta Province, Argentina.

Table 2. Mediterranean Province brachiopod genera of Floian and Dapingian (Arenig) ages, which are largely in finer-grained facies from latitudes of 35–70° N

a Aberdaron, Carmarthen, Ogof Hên formations, Trematid Beds; also Mytton Flags Formation.

Table 3. Tremadocian – early Dapingian brachiopod genera of the Baltic Province (Baltoscandian Basin), South Urals (extension of the Mediterranean Province) and Alborz Terrane (mixed affinities to the faunas of Mediterranean Province and South China)

Fig. 2. Two-dimensional PCA plots on first and second eigenvectors of 163 brachiopod genera from 37 localities of Tremadocian–Dapingian ages from the Mediterranean Province core including Bohemia, Bavaria, Armorican Terrane Assemblage and North Africa, plus other contemporary faunas including Central Andean Basin, Avalonia, Alborz (Iran) and the Baltica continent. B1, Třenice Formation (Tremadocian), Bohemia; B2, Mílina Formation (upper Tremadocian), Bohemia; B3, Klabava Formation (Floian), Bohemia; B4, Železné hory (late Tremadocian – early Floian), east Bohemia; Ba, Vogtendorf Formation (late Tremadocian), Bavaria; W1, Tortworth Inlier, Gloucestershire (Cressagian); W2, Shineton Shale (Migneintian), Shropshire; W3, Ogof Hên Formation (Floian), Wales; W4, Blaencediw Formation (Floian), Wales; W5, Pontyfenni Formation (Dapingian), Wales; W6, Treiorworth Formation (Floian), Anglesey, Wales; Ar, Armorican Quartzite (Floian), Normandy, France, including Budleigh Salterton, England; MN1–4, Montagne Noire, France; MN1 Foulon Formation (Floian–Dapingian); MN2, La Maurerie Formation (Floian); MN3, Cluse de l’Orb Formation (Floian); MN4, Landeyran Formation (Floian); CS, Cabos Series (Tremadocian), Iberian Chains, Spain; M, Upper Fezouata Formation (Floian), Morocco; A1–A3, Tremadocian, Famatina Basin, Argentina; A3, Suri Formation (Floian), Argentina; I1–I3, Alborz, Iran; I1, Simeh-Kuh Formation (Tremadocian); I2, Simeh-Kuh Formation (late Tremadocian); I3, Qumes Formation, Gerd-Kuh Member (Tremadocian); EB2 and EB3, Leetse Formation (Floian), Estonia and Ingria; EB3, Leetse Formation, Vasilkovo Member (Floian), Ingria, Russia; EB4, Volkhov Formation, Päite Member (Floian), Ingria, Russia; EB5, Volkhov Formation, Saka Member (Dapingian), Ingria, Russia; P, Miedzygórz Beds (middle Tremadocian), Holy Cross Mountains, Poland; SU1–SU5, South Urals; SU1, Alimbet Formation (late Tremadocian); SU2, Kidryas Formation (middle Tremadocian); SU3–4, Akbulaksai Formation (early Floian); SU5, Khmelevka Formation (Tremadocian).

Fig. 3. Cluster analysis (using Raup–Crick Similarity Index) of 163 brachiopod genera from 37 localities of Tremadocian–Dapingian ages from the Mediterranean Province core including Bohemia, Bavaria the Armorican terrane cluster, and North Africa, as well as contemporaneous faunas from the Central Andean Basin, Avalonia, Alborz (Iran), and the Baltica continent.

2. Gondwana

The largest continent by far during the Early Ordovician Epoch was Gondwana, which stretched from north of the Equator S-wards to cover the South Pole, which was then under North Africa (Fig. 1). Because it covered so many latitudes, there were biogeographical clines at Gondwana’s eastern and western margins (Cocks & Fortey, Reference Cocks and Fortey1988). In the sector of Gondwana that straddled the Equator to both the north and south, there were the dikelokephalinid trilobite Province and the Cathay-Tasman brachiopod Province (Cocks & Torsvik, Reference Cocks and Torsvik2020), while in the medium to higher latitudes there were the intermediate-latitude brachiopod provinces (including Baltica) as well as the Mediterranean Province discussed here.

The Cambrian origins of the Mediterranean brachiopod faunas are obscured by the significant stratigraphical gaps caused by global late Cambrian – Early Ordovician regressions, which resulted in condensed intervals and erosive unconformities in the Anti-Atlas Mountains of Morocco, the Cantabrian Zone and SW Sardinia (both then within Iberia), and the southern Montagne Noire of France, while the Armorican Massif completely lacks rocks of late Cambrian (Furongian) and Early Ordovician (Tremadocian) ages (Álvaro et al. Reference Álvaro, Ferretti, González-Gómez, Serpagli, Tortello, Vecoli and Vizcaïno2007). Extensive Furongian gaps are also documented from Bohemia, the Turkish Taurides (Dean, Reference Dean2005) and the Uralian margin of the continent of Baltica (Popov & Holmer, Reference Popov and Holmer1994). Baltica was separated by only a narrow ocean from the Mediterranean Province sector of Gondwana at the start of the Ordovician Period, although it subsequently drifted rapidly N-wards so that part of it straddled the Equator by the end of the Ordovician Period (Torsvik & Cocks, Reference Torsvik and Cocks2017). There are relatively continuous late Cambrian (Furongian) successions in the southern Montagne Noire and the Iberian Chains (Álvaro et al. Reference Álvaro, Ferretti, González-Gómez, Serpagli, Tortello, Vecoli and Vizcaïno2007), yet only two rhynchonelliform genera (Billingsella and Saccogonum) are documented from there (Havlíček & Josopait, Reference Havlíček and Josopait1972). Although Cambrian linguliforms were represented by the moderately rich micromorphic brachiopod assemblage near the Guzhangian–Furongian boundary interval, there is no sign of the large shallower-water lingulide biofacies in Gondwana until after the end of the Tremadocian Age. Many of those faunas also lack any orthides, which are usually one of the main components of the Early Ordovician Mediterranean Province.

Hiatuses and highly condensed sedimentation are also characteristic of the Dapingian – early Darriwilian time interval in the Mediterranian and Arabian sectors of Gondwana (Videt et al. Reference Videt, Paris, Rubino, Boumendjel, Dabard, Loi, Ghienne, Marante and Gorini2010; Ghavidel-Syooki et al. Reference Ghavidel-Syooki, Popov, Alvaro, Ghobadi Pour, Tolmacheva and Ehsani2014; Gutiérrez-Marco et al. Reference Gutiérrez-Marco, Sá, Garcıá-Bellido and Rábano2014). As a result, available data on the Dapingian brachiopod taxonomic composition and community structure makes detailed biogeographical analysis very difficult. However, some Dapingian faunas that we have included in this analysis are helpful for observing major trends in the developing biogeographical differentiation of the brachiopod faunas on the moving continents.

3. Armorican Terrane Assemblage

The Mediterranean Province was initially conceived from faunas within the Armorican Terrane Assemblage (Fig. 1, localities 1–4) that surrounds much of the northwestern Mediterranean Sea today (hence the name of the province). Because of later tectonics, chiefly during the Variscan Orogeny, the Ordovician rocks in that Terrane Assemblage today occur in widely separated outcrops. But, as can be seen from Figure 1 and also Franke et al. (Reference Franke, Cocks and Torsvik2017, fig. 10), the various terranes within the Armorican Terrane Assemblage were all integral parts of the main Gondwanan continent at 480 Ma (late Tremadocian). However, rifting between Iberia, Armorica and Bohemia (to the north) and the main part of the Gondwanan continent, as well as Palaeo-Adria, which included Sardinia, Corsica, Adria and Apulia (to the south), caused the start of the opening of the Galicia–Moldanubian Ocean at some time before 460 Ma (late Darriwilian). Nevertheless that ocean did not become significantly wide until after the end of the Ordovician Period, although extensive strike-slip faulting within it moved the northern Armorican terranes some distance laterally to the west. However, that did not prevent those peri-Gondwanan terranes from slowly drifting outside the Mediterranean Province area during Middle Ordovician time; the reason for this was that the South Pole, although it did move slightly, stayed under the NW Africa sector of Gondwana during the entire Ordovician Period (Torsvik & Cocks, Reference Torsvik and Cocks2017). The Armorican Assemblage terranes are now reviewed individually as follows.

3.a. Bohemia

Bohemia today lies mostly within the Czech Republic (Fig. 1, locality 1). Havlíček & Vanĕk (Reference Havlíček and Vanĕk1966) listed all the faunas then known from the Mílina Formation (late Tremadocian) and the Klabava Formation (Floian and Dapingian). Havlíček (Reference Havlíček1982) and Mergl (Reference Mergl1995, Reference Mergl2002) described the lingulides from the same formations, and Havlíček (Reference Havlíček1977) monographed the Orthida from the entire Palaeozoic strata of Bohemia. Havlíček et al. (Reference Havlíček, Vanĕk and Fatka1994) postulated that the Barrandian Basin in the centre of Bohemia formed a large part of an independent terrane that they termed Perunica but, after review, Franke et al. (Reference Franke, Cocks and Torsvik2017) established that during Early Ordovician time it was in the same large fragment of Gondwana (and subsequently peri-Gondwana) as Iberia and Armorica before the late Palaeozoic Variscan events. The faunas in our analysis, all described by Mergl (Reference Mergl2002), Havlíček (Reference Havlíček1977) and Havlíček & Vanĕk (Reference Havlíček and Vanĕk1966), are from the Třenice Formation (middle Tremadocian, B1), the Mílina Formation (upper Tremadocian, B2) and the Klabava Formation (Floian–Dapingian, B3).

A small late Tremadocian – Floian brachiopod fauna with Angusticardinia, Hesperonomiella, Hyperobolus and Lingulella is known from an isolated locality at Železné hory, east Bohemia (Budil et al. Reference Budil, Mergl and Smutek2016) (B4). While the age constraints for this assemblage are relatively poor, the presence of Angusticardinia and Hyperobolus is of considerable interest as a possible biogeographical link with approximately contemporaneous faunas of South Urals.

3.b. Bavaria

The Frankenwald of Bavaria, Germany (Fig. 1, locality 2), formed part of the Moldanubian Terrane during the Ordovician Period. A late Tremadocian fauna from the Vogtendorf Formation (Sdzuy et al. Reference Sdzuy, Hammann and Villas2001) (Ba) contains craniids that can be provisionally assigned to Deliella, and the rhynchonelliform brachiopods Jivinella sp., Kvania kvanica (Mergl, Reference Mergl1984), Poramborthis vonhorstigi Sdzuy et al. Reference Sdzuy, Hammann and Villas2001, Poramborthis cf. klouceki Havlíček, Reference Havlíček1949 and Ranorthis franconica Sdzuy et al. Reference Sdzuy, Hammann and Villas2001.

Another important early Tremadocian fauna was documented by Sdzuy (Reference Sdzuy1955) from the Leimitz Shale Formation. While its strong biogeographic affinity to the Bohemian faunas is evident from the occurrence of Jivinella?, Poramborthis, Orbithele and Thysanotos, the generic assessments of the species assigned to Acrotreta, Lingulella, Nanorthis and Siphonotreta are questionable and the problem cannot be resolved without access to the original collections. That fauna is therefore not included in the cluster analysis presented in this paper.

3.c. Northern France and SW England

In Normandy and Brittany (Fig. 1, locality 3), brachiopod faunas including the distinctive large lingulides were originally described by Rouault (Reference Rouault1850) and revised by various subsequent authors, including Cocks (Reference Cocks1993), and some of their sites were plotted by Emig & Gutiérrez-Marco (Reference Emig and Gutiérrez-Marco1997). Similar large lingulides of Floian ages are known from Britain only in SW England, where they are found within the Gorran Quartzite of Cornwall and also as pebbles within the Budleigh Salterton Pebble Beds of Budleigh Salterton, Devonshire; both those English faunas are included within sample Ar.

The Gorran Quartzites are large olisthostrome blocks within Early Devonian mélanges that were transported NW-wards from Armorica during the late Palaeozoic Variscan Orogeny, and a few comparable pebbles have been occasionally found within other Permo-Triassic conglomerates from as far north as near Birmingham, central England. Although all lithologically similar and mostly containing higher-latitude Gondwanan assemblages, those Permo-Triassic pebbles contain brachiopods of four different ages: two Ordovician and two Devonian (Cocks, Reference Cocks1993). All of those pebbles must therefore have been transported fluvially from northwestern France after the Variscan Orogeny was over near the end of the Palaeozoic Era, and when Europe had largely become united (Franke et al. Reference Franke, Cocks and Torsvik2017). The microcontinent of Avalonia, which included nearly all of England and Wales but not Devonshire and Cornwall (see next section), did not itself host any Group 1 Mediterranean Province brachiopods during Early Ordovician time.

3.d. The Montagne Noire

Much has been published on this very tectonized area near Montpellier in southern France, which includes various fragments of Ordovician rock that were all substantially displaced in Devonian and later times in the Variscan Orogeny (Franke et al. Reference Franke, Cocks and Torsvik2017). Havlíček (Reference Havlíček1980) described the large lingulide brachiopods, Mélou (Reference Mélou1982) the rhynchonelliform brachiopods and, together with Vizcano et al. (Reference Vizcano, Álvaro and LeFebvre2001), provided a summary of the Cambrian and Ordovician faunas and sediments. Both Group 1 and Group 2 of the Mediterranean Province are seen in the Montagne Noire. The faunas in our analysis are from the Saint Chinian Formation (Tremadocian, MN1), La Maurerie Formation (Floian, MN2), Cluse de l’Orb Formation (Floian, MN3) and the Landeyran Formation (late Floian, MN4).

3.e. Iberia

The whole Iberian Peninsula (Fig. 1, locality 4) can be divided into at least six terranes (often termed ‘zones’) whose rocks have been intermingled and affected by many orogenic events from late Precambrian time throughout much of the Phanerozoic Eon. Precisely where each terrane lay (and their individual relationships with all of the others) within the Peri-Gondwanan mélange during the Early Ordovician Epoch is quite uncertain in detail, but their contained faunas indicate that they must all have been parts of the Mediterranean Province region (Gutiérrez-Marco et al. Reference Gutiérrez-Marco, Robardet, Rábano, Sarmiento, San José Lancha, Herranz Araújo, Pieren Pidal, Gibbons and Moreno2002). Large linguliform brachiopods of Group 1 have been recorded from many Spanish localities in the Cantabrian, West Asturia-Leonese (WALZ), Iberian Cordillera and Central Iberian zones by Emig & Gutiérrez-Marco (Reference Emig and Gutiérrez-Marco1997), and by Coke & Gutiérrez-Marco (Reference Coke and Gutiérrez-Marco2001) from the Central Iberian Zones of northern Portugal. The occurrence of Poramborthis hispanica Havlíček (in Havlíček & Josopait, Reference Havlíček and Josopait1972) in the Iberian Chains (IC) represents the most westerly known occurrence of the family Poramborthidae within the Mediterranean Province. The only other Tremadocian rhynchonelliform brachiopod is the polytoechioid Protambonites primigenus Havlíček, which Villas (Reference Villas1995) documented from the Cabos Series (Tremadocian) in the WALZ area of the Cantabrian Mountains and is included in our analysis (CS).

3.f. Eastern Europe

Gutiérrez-Marco et al. (Reference Gutiérrez-Marco, Yanev and Sachanski1999) described a fauna from Serbia (Fig. 1, locality 9) and Macedonia that included Lingulobolus (which may be an erroneous identification of Leptembolon), and what Havlíček (Reference Havlíček1989) recorded as Thysanobolus?, although that is a junior synonym of Thysanotos (see Mergl Reference Mergl2002). Gutiérrez-Marco et al. (Reference Gutiérrez-Marco, Yanev and Sachanski1999) also reviewed other faunas from Serbia that may include some Group 1 large lingulids, although that needs confirmation. If it is true, then those faunas would represent the furthest extent of the Group 1 Mediterranean Province assemblage to the east in Europe, which is within a region that has been very much affected by both the Tertiary Alpine Orogeny as well as the Palaeozoic Variscan Orogeny (Franke et al. Reference Franke, Cocks and Torsvik2017). However, reassessment of this fauna is difficult since the published identifications are problematic and the photographs are poor, and the specimens recall the Leptembolon–Thysanotos fauna rather than being clearly comparable to the large lingulides from the Armorican Quartzite; we therefore exclude this fauna from our analysis. Nevertheless, we speculate that this area was part of the Adria and Tisia Terrane (Units 333 and 367 of Torsvik & Cocks, Reference Torsvik and Cocks2017), which was an integral part of the main Gondwanan continent during the Ordovician Period, situated to the north of the NE Africa sector.

4. Avalonia

Apart from its southwestern tip in Devon and Cornwall (which were parts of Armorica), England and Wales both lay within the relatively small continent of Avalonia during Early Ordovician time (Fig. 1, locality 7). That continent had newly separated from Gondwana just prior to Cambro-Ordovician boundary time, with rifting and the initial opening of the Rheic Ocean at about 490 Ma (Cocks & Fortey Reference Cocks and Fortey2009). Avalonia extended across today’s North Atlantic to include parts of Canada (much of Newfoundland, New Brunswick and Nova Scotia) and the United States of America as far south as Cape Cod, Massachusetts. The Early Ordovician rocks exposed in Carmarthenshire and Pembrokeshire, southwestern Wales, were laid down in a relatively deep-water back-arc basin with many volcanics (Traynor, Reference Traynor1988) on the NW margin of Avalonia, and virtually all of the shelly faunas found in many localities within them have been transported from the nearby shelves and redeposited beneath deeper water. The brachiopods from southwestern Wales were revised by Cocks & Popov (Reference Cocks and Popov2019), and many of those from the Ogof Hên and Blaencediw formations there are typical Group 2 of the Mediterranean Province. Those in our analysis are the Ogof Hên Formation and ‘Trematid Beds’ (included in W3) (Moridunian: Floian); Brunel Formation (Whitlandian: Floian) (included in W3); Blaencediw Formation (included in W4) (Whitlandian: Floian); and the Pontyfenni Formation (Fennian: Dapingian) (included in W5). In addition, Cressagian (Tremadocian) faunas from the Llangynog Inlier, also in Carmarthenshire, and the Harlech Dome in north Wales were included in our analysis (W1).

From the Welsh Borderland of England (Shropshire), Williams (Reference Williams1974) described the Ordovician fauna of the Shelve Inlier, where the Floian Stiperstones Quartzite yielded only a few brachiopods, but the succeeding Mytton Flags was found to carry more brachiopods of Floian–Dapingian ages (Williams, Reference Williams1974), and are included in our analysis (E1). The linguliform brachiopods of the Shineton Shale Formation of Migneintian (late Tremadocian) age, also in Shropshire and described by Sutton et al. (Reference Sutton, Bassett and Cherns1999, 2000) are also included (W2) and, from further south, the faunas in the Tortworth Inlier of Gloucestershire in the Micklewood and Breadstone Formations (Cressagian, W1).

However, slightly later latest Dapingian and early Darriwilian rocks in NW Wales to the NW of the Bala Fault, such as the Anglesey fauna of the Treiorworth Formation (W6) (late Floian) described by Bates (Reference Bates1968) and revised by Neuman & Bates (Reference Neuman and Bates1978), carry more diverse brachiopods, many different from those in SW Wales. That is perhaps because they may not have been as close to SW Wales during Early Ordovician time as they are today, and were probably at a slightly lower palaeolatitude. Nevertheless, both the Anglesey and Shropshire faunas can both be identified as variants of Group 2 of the Mediterranean Province, although the Anglesey faunas are mostly of a slightly later age than the majority of faunas considered in this paper.

The contemporary higher-latitude trilobites were included within the calymenacean–dalmanitacean Province; however, its extent only partly overlapped the brachiopods of the Mediterranean Province during Early Ordovician time (Fortey & Cocks, Reference Fortey and Cocks2003). It is also important to recognize that Avalonia was an integral part of the higher-latitude Mediterranean Province only during Early Ordovician time, since that microcontinent’s independent drift across the closing Iapetus Ocean and behind the widening Rheic Ocean ensured that it progressively entered much lower latitudes during Darriwilian and later Ordovician times (Torsvik & Cocks, Reference Torsvik and Cocks2017). The Floian and Dapingian age brachiopods considered here are therefore almost the final representatives of the true Mediterranean Province in the Avalonian microcontinent. Since the Floian and Dapingian bivalves found in Carmarthenshire are the earliest known from Gondwana (Cope, Reference Cope1996), this also appears to reflect the slightly lower latitude of South Wales during Early Ordovician time by comparison with much of the rest of the Mediterranean Province area.

Western Avalonia is the western limit of the large lingulides of the Lingulobolus Association. In particular, Lingulobolus affinis (Billings, Reference Billings1872) occurs in substantial numbers in Bell Island, Newfoundland (Fig. 1, locality 8), where it forms a monotaxic community. However, that fauna has not been included in our statistical analysis since it cannot be discriminated from the similarly monotaxic Lingulobolus Association of NW Africa (Popov et al. Reference Popov, Legrand, Bouterfa and Ghobadi Pour2019).

5. North Africa

Lower Ordovician rocks crop out in many areas of North Africa (Fig. 1, localities 5 and 6), where Torsvik & Cocks (Reference Torsvik and Cocks2011, fig. 6), plotted many sites of the distinctive large lingulides of the Mediterranean Province on a 480 Ma palaeogeographical reconstruction. The Ordovician brachiopods of Morocco were described by Havlíček (Reference Havlíček1971) and Mergl (Reference Mergl1981), and some of the larger Group 1 lingulides from Algeria (KA) by Legrand (Reference Legrand1971) and Popov et al. (Reference Popov, Legrand, Bouterfa and Ghobadi Pour2019); of Libya and Tunisia by Massa et al. (Reference Massa, Havlíček and Bonnefous1977); and of Algeria and Morocco by Mergl (Reference Mergl1983). Havlíček (Reference Havlíček1971) reviewed other North African areas and noted more Group 1 sites there. We have included brachiopods from the Upper Fezouata Formation (Arenig: Floian) of Morocco (M) from Videt et al. (Reference Videt, Paris, Rubino, Boumendjel, Dabard, Loi, Ghienne, Marante and Gorini2010), and a monotaxic Lingulobolus Association from the uppermost Kheneg el Aatène Formation of the Ougarta Range, Algeria (KA), in our analysis.

6. Middle East and Iran

Early Ordovician brachiopods are in general poorly known from southwestern Asia (the Middle East), but there are many and varied terranes in the region south and SW of the Altaid Fold Belt in Kazakhstan and adjacent countries. Some were integral sectors of Gondwana during Early Ordovician time, but most were independent peri-Gondwanan terranes (Popov & Cocks, Reference Popov and Cocks2017). However, because they spanned a wide range of palaeolatitudes, none of the brachiopod faunas can definitely be classified within the Mediterranean Province, and most were within the Intermediate Latitude Province to its then north. The latter include the Taurides of Turkey (then an integral sector of Gondwana), Karakorum and the various terranes within modern Iran (Fig. 1, locality 10) such as the Alborz and Lut terranes (Cocks & Torsvik, Reference Cocks and Torsvik2013). A relatively representative record of the Early Ordovician faunas currently exists only for the Alborz Terrane (Popov et al. Reference Popov, Ghobadi Pour and Hosseini2008, Reference Popov, Ghobadi Pour, Bassett and Kebria-Ee2009, Reference Popov, Kebria-Ee Zadeh, Ghobadi Pour, Holmer and Modzalevskaya2013 b; Ghobadi Pour et al. Reference Ghobadi Pour, Popov, Kebria-Zadeh and Baars2011; Kebria-ee Zadeh et al. Reference Kebria-ee Zadeh, Ghobadi Pour, Popov, Baars and Jahangir2015). While Mediterranean affinities prevail among the linguliform brachiopod associations, the rhynchonelliform brachiopod fauna became increasingly similar to the contemporaneous fauna of South China by the end of Early Ordovician time, as well as also including some endemic genera. Our analysis includes brachiopods from two levels in the Simeh–Kuh Formation – one in the middle Tremadocian Stage (Paltodus deltifer deltifer Zone, I1) and the other in the uppermost Tremadocian Stage (Drepanoistodus aff. amoenus Subzone, I2) – and three levels from the Qumes Formation – Gerd-Kuh Member (Floian, Prioniodus elegans Zone, I3), the Raziabad Member (uppermost Floian-lower Dapingian, I4) and a further member of the lower Dapingian Stage (Baltoniodus navis Zone, I5).

7. South and Central America

Early Ordovician brachiopods are known from several parts of the western and southern parts of South America (Fig. 1, locality 11), including Bolivia (Havlíček & Branisa, Reference Havlíček and Branisa1980) and Argentina (Benedetto, Reference Benedetto2003), but the bulk of today’s continent was then land. Nevertheless, when describing aspects of the Tremadocian brachiopods of the Central Andean Basin in NW Argentina, particularly the eoorthid Apheoorthina, Muñoz & Benedetto (Reference Muñoz and Benedetto2016) noted that 64% of the genera in that fauna are shared with the Mediterranean area, particularly Bohemia, but the larger lingulates have not been recorded in South America.

From Argentina (not the Famatina Basin in the Precordillera, only Western Puna and the North-west Basin), Benedetto & Carrasco (Reference Benedetto and Carrasco2002), Benedetto (Reference Benedetto2009), Benedetto et al. (Reference Benedetto, Vaccari, Waisfeld, Sánchez and Foglia2009), Villas et al. (Reference Villas, Herrera and Ortega2009), Benedetto & Muñoz (Reference Benedetto and Muñoz2015, Reference Benedetto and Muñoz2017) and Lavié & Benedetto (Reference Lavié and Benedetto2020) recorded brachiopods included in our analysis. Within sample A1 are grouped the Las Vicuñas Formation (mainly Tremadocian Cordylodus angulatus Zone), the lower Tremadocian Guayoc Chico Group, Cardonal Formation and the Devendeus Formation. In sample A2 (late Tremadocian, Paltodus deltifer and Paroistodus proteus zones) we have grouped the Santa Rosita Formation, the Saladillo Formation, the Coquena Formation, Upper Member and an unnamed sandstone in Salta Province. Within sample A3 are grouped the Floresta Formation and the Upper Suri Formation (late Floian, Oepikodus evae Zone), while the fauna from the Molles Formation (late Floian – early Dapingian?) is listed separately (A4).

From southern Mexico, Streng et al. (Reference Streng, Mellbin, Landing and Keppie2011) described the late Cambrian and Tremadocian inarticulated brachiopods from what was then the Oaxaquia Microcontinent (Fig. 1, locality 8) and recorded seven genera from the upper half of the Teñu Formation, the acrotretoids Eurytreta?, Ottenbyella? and Semitreta, the endemic siphonotretoid Oaxaquitreta, and three unidentified linguloids, an obolid and Lingulella?. While not a clear-cut Mediterranean Province fauna, that assemblage can be interpreted as representing a cline between it and the Intermediate Latitude Province, as might be expected from Oaxaquia’s estimated position at about 35° S; however, that fauna has not been included in our statistical analysis.

8. Baltica

During the Furongian and Tremadocian ages, the South Uralian margin of Baltica continent was located in high southern latitudes (Fig. 1, localities 12–14), probably at > 60° S. It was facing the Mediterranean margin of Gondwana and was separated by a narrow ocean from the Gondwana margin (Torsvik & Cocks, Reference Torsvik and Cocks2017). The Lower Ordovician linguliform brachiopod fauna of the South Urals was monographed by Popov & Holmer (Reference Popov and Holmer1994), and the billingsellides were revised by Popov et al. (Reference Popov, Vinn and Nikitina2001). Published data on the rhynchonelliform brachiopods (Andreeva, Reference Andreeva and Markovskii1960; Nasedkina, Reference Nasedkina, Sapelnikov and Chuvashov1977) are very outdated, but they are supplemented by a further collection originally made by VV Korinevskii and currently under revision in the National Museum of Wales; the genera analysed here have therefore all been newly reassessed by LEP. The Early Ordovician linguliform brachiopods of the South Urals are very similar to the contemporaneous faunas of Bohemia and Alborz (Popov et al. Reference Popov, Holmer, Bassett, Pour and Percival2013 a). The moderately rich Floian rhynchonelliform brachiopod fauna from the South Urals includes a considerable proportion of endemic genera, yet the presence of Protambonites is a clear signature of the Mediterranean Province, as well as the occurrence of the trilobite Asaphellus. The linguliform brachiopods also show distinct similarity to those in Gondwana. Faunas included in our analysis include those from the Alimbet Formation (Tremadocian, SU1), the Kidryas Formation (Tremadocian, Paltodus deltifer Zone equivalent, SU2), the Akbulaksai Formation (lower Floian, SU3), the Koagash Formation (upper Tremadocian, SU4) and the Khmelevka Formation (Tremadocian, SU5).

From the area on the eastern side of the Baltic Sea itself (Fig. 1, locality 13) we have analysed more newly reidentified brachiopods from the Leetse Formation: the Ioa Member in North Estonia (Floian, Paroistodus proteus Zone, EB1); the Mäekula Member in Tallinn, Estonia and the Popovka Stream near Pavlovsk, Ingria, Russia (Floian: Prioniodus elegans Zone, EB2); the Vasilkovo Member from the Popovka Stream near Pavlovsk and the Lava River, Ingria (Floian, Oepikodus evae Zone, EB3); the Päite Member (Floian, Oepikodus evae Zone) of the Volkhov Formation in the Lava and Syas rivers, Ingria (EB4); and the Saka Member (Dapingian, Baltoniodus triangularis – B. navis Zones), also of the Volkhov Formation (EB5).

In the Holy Cross Mountains of Poland (Fig. 1, locality 14), the largely inarticulated brachiopods from the underlying Miedzygórz Beds (Tremadocian, P) were described by Biernat (Reference Biernat1973) and Holmer & Biernat (Reference Holmer and Biernat2002). Above them lie the Lower Bukówka Beds whose brachiopods were reviewed in Cocks (2002) and included Plectella, Lycophoria, Paurorthis, Antigonambonites and Syntrophina? They are probably of late Floian age, but may be of earliest Dapingian; in either case they represent a well known assemblage that is very characteristic of the Baltic Province since it was entirely confined to that continent during Early Ordovician time.

9. Palaeogeography and analysis

The new biogeographical analysis of the Early Ordovician brachiopod faunas is based on the extensive database assembled by the authors, which includes 167 rhynchonelliform and linguliform genera representing 42 individual faunas varying in age from middle Tremadocian to early Dapingian. The dataset was subjected to cluster analysis (Raup–Crick Similarity Index) and a principal components analysis (PCA) using the PAST (palaeontological statistics) programme (Hammer & Harper, Reference Hammer and Harper2006, Hammer et al. Reference Hammer, Harper and Ryan2014).

The data sources used in the analysis are heterogenous. Most of the individual faunas are simply lists of taxa that occur in a single lithostratigraphical unit. However, in several cases they represent time slices that include several lithostratigraphical units; for example, the inarticulated brachiopods from British regional stages revised by Sutton et al. (Reference Sutton, Bassett and Cherns1999, 2000) and the Tremadocian faunas of Argentina. Faunas derived from a single lithostratigraphical unit may belong to a single, sometimes monotaxic, community (e.g. the Cabos Series of the Iberian Chains) or a number of different communities (e.g. the Třenice, Mílina and Klabova formations of Bohemia). However, our data still permits us to trace the biogeographical differentiation of the brachiopod faunas within the Mediterranean Province area, the possible centres of origin and initial dispersion of certain key taxa and entire communities, and the faunal divergence caused by the progressive drifting apart of the Baltica and Avalonia continents.

The end of the Cambrian Period was a time of substantial decline of linguliform brachiopod faunas (Bassett et al. Reference Bassett, Popov and Holmer1999) especially evident in the acrotretides, with only six genera crossing the Cambrian–Ordovician boundary. A significant turnover also occurred in the lingulide communities nearshore. The distinctive obolid fauna of the Baltoscandian basin disappeared without descendants near the beginning of the Tremadocian Age (Popov et al. Reference Popov, Khazanovitch, Borovko, Sergeeva and Sobolevskaya1989). The observed patterns of the linguliform biogeographical distribution across the Mediterranean Province in the Tremadocian were therefore due to post-extinction recovery and dispersal. The biofacies differentiation of the Tremadocian–Floian linguliform brachiopod faunas is best documented in Bohemia, as summarized by Mergl (Reference Mergl2002).

The biogeography of the Tremadocian rhynchonelliform brachiopods is poorly constrained because of the relatively small number of localities and low-diversity individual faunas known from across the world; however, broadly low-latitude and high-latitude provinces can be recognized (Harper et al. Reference Harper, Rasmussen, Liljeroth, Blodgett, Candela, Jin, Percival, Rong, Villas and Zhan2013). Further analysis of the mixed linguliform and rhynchonelliform brachiopod assemblages in this paper has also revealed some links helpful for a better understanding of the changing biogeographical patterns in brachiopod dispersal across the southern latitudes during Early Ordovician time.

PCA shows that the Early Ordovician faunas of Western Mediterranean Gondwana, North Africa, Argentina, the Alborz terrane of Iran and the Uralian margin of Baltica formed a compact cluster together with the Tremadocian faunas of Avalonia and Tremadocian – early Floian fauna of the East Baltic (Fig. 2). Remarkably, they completely lack any rhynchonelliform component, which suggests that such clustering is defined in significant part by the geographical distribution of the linguliform taxa. The cluster is characterized by low to moderate negative scores along the second direction of variations, and low negative to low positive scores (−0.8 to 0.8) along the first direction of variations. The only visible differentiation can be seen in the distribution of the Argentinian and Uralian faunas: the latter are characterized by exclusively positive scores along the first direction of variations against the negative scores characteristic of the Argentinian faunas.

Surprisingly, almost all the Early Ordovician brachiopod faunas of Bohemia are placed outside the main cluster of the faunas here assigned to the Mediterranean Province (Fig. 2). They are characterized by positive scores along the second direction of variation and higher positive scores along the first direction of variations, both increasing in time from the Tremadocian to the Dapingian ages. The Early Ordovician Bohemian brachiopod faunas are characterized by the high endemism of rhynchonelliform brachiopods represented by the monotaxic family Poramborthidae (Mergl, Reference Mergl2011) and the high proportion of endemic orthide genera, for example, Ferrax, Nocturniella and Robertorthis. In contrast, the eoorthid Jivinella and endopuctate Nereidella represent some contact with South China, although they are missing from other Mediterranean faunas. The Early Ordovician linguliformeans of Bohemia are outstandingly rich in the generic composition of the assemblages, with many genera in high to temperate southern latitudes unknown from other contemporary faunas.

The Floian to early Dapingian brachiopod faunas of Avalonia are also placed outside the main cluster of the Mediterranean faunas, and show strongly negative scores along the first direction of variations and positive scores along the second direction of variations. Similar tendencies can be seen in the distribution of the Moridunian and Whitlandian linguliform brachiopod faunas (Fig. 2), which is probably a sign of steadily increasing biogeographical divergence.

In the cluster analysis (Raup–Crick Similarity Index), the Moridunian–Floian faunas of Avalonia appear quite distant from other analysed faunas of the Mediterranean Province plus Baltic faunas, forming a separate first-order cluster together with the Floian Argentinian faunas of the Suri and Molles formations (Fig. 3). The Avalonian fauna includes a large proportion of endemic genera (Astraborthis, Rhynchorthis, Rectotrophia and Treioria) or genera that are otherwise known only from the Floian Stage of the Central Andean Basin (Ffynnonia, Monobolina, Monorthis, Skenidioides, Protoskenidioides, Rugostrophia and Productorthis), although some of them make later appearances outside those regions. The plectambonitoidean taffiides Aporthophyla, Taffia and Inversella (Reinversella) make their earliest appearances in Avalonia, which can therefore be considered as the centre of their origin and initial dispersal.

Similarly, the Floian brachiopod fauna of the Central Andean Basin (A3, A4) also contains a significant proportion of local endemics, including Famatinobolus, Chilcatreta, Incorthis, Mollesella, Suriorthis, Punastrophia and the earliest occurrence of the taffiid Ahtiella, and is characterized by the relative abundance of the earliest skenidiids (Crossiskenidium, Skenidioides and Protoskenidioides). Not surprisingly, in the cluster analysis it shows a significant degree of separation from the other Mediterranean faunas and clusters together with British faunas (Fig. 3).

The Tremadocian faunas of the Central Andean Basin (A1, A2) grouped in a separate second-order cluster (Fig. 3). They are characterized by the relative abundance of the early plectorthoid genera (Euorthisina, Gondwanorthis, Incorthis, Lampazarorthis, Lesserorthis, Kvania, Notorthisina and Tarfaya) assigned by Benedetto & Muñoz (Reference Benedetto and Muñoz2015) to the reincarnated family Nanorthidae. They were mostly short-lived local endemics forming low-diversity associations, but some of them show wider geographical distributions. Gondwanorthis is also known from the middle Tremadocian Stage of Iran, Incorthis from the Tremadocian Stage of Bolivia and Morocco, and Kvania from the Mílina Formation of Bohemia (Havlíček et al. Reference Havlíček, Vanĕk and Fatka1994) and Bavaria (Sdzuy et al. Reference Sdzuy, Hammann and Villas2001). The Tremadocian rhynchonelliform brachiopod faunas of the Central Andean Basin include the earliest documented representatives of the families Euorthisinidae (Euorthisina and Notorthisina), Tarfayidae (Tarfaya) and Anomalorthidae (Astraborthis). By Floian time, the Euorthisinidae had dispersed to Avalonia, Bohemia, North Africa and South China (Gutiérrez-Marco & Villas, Reference Gutiérrez-Marco and Villas2007). Notorthisina is probably phylogenetically closely related to Lipanorthis (Benedetto & Muñoz, Reference Benedetto and Muñoz2017), which is the earliest yet known endopunctate orthide. The Anomalorthidae also proliferated in Floian time when they are known from Avalonia and the Uralian margin of Baltica (Alimbella and Medesia), and by the Darriwilian Age had dispersed to Laurentia (Anomalorthis). Tarfaya spread widely during middle–late Tremadocian time across Gondwana, being reported from North Africa, Alborz in Iran and Tasmania as a part of monotaxic or oligotaxic brachiopod communities; it often forms characteristic shell beds nearshore. According to the phylogenetic analysis of Benedetto & Muñoz (Reference Benedetto and Muñoz2017), Tarfaya is most probably the ancestral taxon of the endopunctate family Heterorthidae, which later played a significant role in the Middle–Late Ordovician brachiopod faunas of the Mediterranean Province. In Tremadocian time, the Central Andean Basin was therefore an important brachiopod biodiversity hotspot and a cradle for several lineages that dispersed during late Tremadocian – Floian time across the Mediterranean Province and beyond, including the endopunctate orthides, which played a very important role within the Late Ordovician faunas of the Mediterranean Province.

The linguliform brachiopods of the Central Andean Basin are incompletely known, especially their acrotretide and siphonotretide components, yet they include typical Mediterranean genera such as Leptembolon and Libecoviella, while Monobolina there is otherwise known only from East Avalonia (Benedetto &Muñoz, Reference Benedetto and Muñoz2015; Lavié & Benedetto, Reference Lavié and Benedetto2020).

The core of the Early Ordovician Mediterranean Province is formed by the Tremadocian faunas of Avalonia and Early Ordovician faunas of Bohemia, Bavaria, Montagne Noire, Spain and the South Urals (Fig. 3). It also includes the Tremadocian faunas of Alborz (Iran) and the middle Tremadocian – early Floian linguliform brachiopod faunas of Baltica. In the cluster analysis (Raup–Crick Similarity Index) it appears as a separate subclade within the third-order clade together with the faunas of the emerging Baltica Province. That is not surprising since there are no documented rhynchonelliform brachiopod faunas across Baltica through late Cambrian (Furongian) time, except those from Novaya Zemlya (Holmer et al. Reference Holmer, Popov, Ghobadi Pour, Klishevich, Liang and Zhang2020) and the pioneering moderately rich Floian rhynchonelliform associations from middle–late Floian time of Baltoscandia that emerged suddenly due to immigration, most probably from the temperate-latitude sector of Gondwana (Sturesson et al. Reference Sturesson, Popov, Holmer, Bassett, Felitsyn and Belyatsky2005). Indeed, the brachiopod assemblages from the Mäekula and Vasilkovo members (Prioniodus elegans to Oepikodus evae zones) of Estonia and Ingria contain, in addition to the neoendemics Eoporambonites, Leoniorthis, Lycophoria, Panderina, Plectella and Porambonites, a sizeable fraction of genera otherwise characteristic of the Mediterranean Province, for example, Angusticardinia, Apheoorthina, Ocorthis, Paurorthis, Prantlina and Ranorthis (Havlíček, Reference Havlíček1971, Reference Havlíček1977; Mélou, Reference Mélou1982). It is rather surprising that the brachiopod assemblage from the Upper Fezouata Formation (Floian) of Morocco appears to be closely linked to the earliest Baltoscandian brachiopod associations in the cluster analysis (Fig. 3), but that may simply be a coincidence.

In our analysis, Tremadocian–Floian faunas from the Montagne Noire (MN1, 2, 4) appear quite distant from the other faunas of the Mediterranean Province. Instead, they more closely cluster with the early Baltic faunas (Fig. 3). That affinity is mainly defined by the co-occurrence of linguliforms such as Acrotreta, Rafanoglossa, Spondyglosella and Westonia, but also by the rhynchonelliform genera Ocorthis, Prantlina and Ranorthis. The latter three were also characteristic of the Floian of Baltoscandia (Rubel, Reference Rubel1964). The middle Floian rhynchonelliform brachiopod immigration event in Baltoscandia occurred synchronously with proliferation of the bryozoans, ostracods and agglutinated foraminifers as a part of the early dispersal of the benthic communities with the characteristic features of the Palaeozoic Evolutionary Fauna (Bassett et al. Reference Bassett, Popov and Holmer2002). That immigration was preceded by the almost complete extinction of Furongian – early Tremadocian obolid and siphonotretide local lineages (Ghobadi Pour et al. Reference Ghobadi Pour, Bauert, Popov, Holmer and Álvaro2017) and was followed by the invasion of the Thysanotos–Leptembolon linguliform brachiopod Association, which had originally evolved in the temperate latitudes of Gondwana (Bednarczyk, Reference Bednarczyk1988, Reference Bednarczyk1999; Popov & Holmer, Reference Popov and Holmer1994; Mergl, Reference Mergl1997, Reference Mergl2002). Dispersal of the latter fauna during late Tremadocian – early Floian time towards the Baltoscandian basin was therefore the time of maximum expansion of the Mediterranean Province.

The individual brachiopod faunas grouped within the Early Ordovician faunas of the Mediterranean Province core represent mainly low- to medium-richness assemblages of linguliformean and rhynchonelliform brachiopods, often with little sign of biofacies differentiation. Linguliform brachiopods prevail within the Tremadocian faunas, yet rhynchonelliforms constitute a sizeable fraction within the faunas of Bohemia and Alborz, and the significance of rhynchonelliforms steadily increased during Floian time. The best studied Early Ordovician Mediterranean faunas are from Bohemia, where Mergl (Reference Mergl2002) was able to recognize a number of depth-related brachiopod communities based on 82 individual localities. Some of them are important in the definition of the Mediterranean Province, and others give some clues about the origins of the individual faunas within the Province. Probably the most significant is the Leptembolon Community, which can be considered to be a local variation of the Thysanotos–Leptembolon Association. The latter was also widespread across Baltica, including the Klooga and Joa members (upper Tremadocian – lower Floian, Drepanoistodus proteus – Prioniodus elegans conodont zones) of North Estonia, the Zbilutka Beds (middle Tremadocian, Paltodus deltifer conodont Zone) of the Holy Cross Mountains in Poland (Bednarczyk, Reference Bednarczyk1988), and the South Urals in the upper Tremadocian – lower Floian Alimbet and Akbulaksai formations (Popov & Holmer, Reference Popov and Holmer1994). In Alborz, Iran, the occurrence of the Thysanotos–Leptembolon Association is diachronous but is nevertheless confined entirely to the lower Floian Prioniodus elegans Zone (Popov et al. Reference Popov, Ghobadi Pour and Hosseini2008). According to Mergl (Reference Mergl2002), the Bohemian Leptembolon Community was characteristic of the lower shoreface to upper offshore transition; however, locally Thysanotos overlaps with the rhynchonelliform Protambonites, which is the dominant taxon in the oligotaxic to almost monotaxic rhynchonelliform communities nearshore in the South Urals and Alborz (Popov et al. Reference Popov, Vinn and Nikitina2001, Reference Popov, Ghobadi Pour, Bassett and Kebria-Ee2009) and forms shell beds in the Cabos Series of the Cantabrian Mountains, Spain (Villas, Reference Villas1995). The Bohemian Hyperobolus Community was confined to the mobile sands nearshore (Mergl, Reference Mergl2002), and in life strategies the characteristic taxa strongly resemble the Furongian nearshore obolid communities of the Baltoscandian basin (Popov et al. Reference Popov, Khazanovitch, Borovko, Sergeeva and Sobolevskaya1989). Hyperobolus also occurs in the South Urals in the shell beds formed by the polytoechioid Korinevskia in the Tremadocian Akbulaksai Formation (Popov et al. Reference Popov, Vinn and Nikitina2001). Those oligotaxic to monotaxic polytoechioid brachiopod associations, which produced characteristic shell beds nearshore at the Uralian margin of Baltica and temperate latitude Gondwana, seem to be related to the late Cambrian (Furongian) billingsellide associations (Bassett et al. Reference Bassett, Popov and Holmer2002). The earliest polytoechioids are from the Furongian Stage of Alborz (Iran) and South China (Popov et al. Reference Popov, Holmer, Bassett, Pour and Percival2013 a), which were the likely regions for the origin and subsequent dispersal of the group.

The rhynchonelliform component of the Early Ordovician Bohemian fauna is represented predominantly by the orthides. Some of them were short-lived local endemics (Ferrax and Robertorthis); others (Apheoorthina, Prantlina and Ranorthis) subsequently migrated towards Baltoscandia. Nocturnellia from the Klabava Formation is the earliest genus of the Enteletoidea, another group of endopunctate orthides that achieved much eminence within the higher-latitude faunas during Late Ordovician time. The short-lived monotaxic family Poramborthidae was relatively widespread in the Tremadocian Age, being documented from Bohemia (Havlíček, Reference Havlíček1977), Bavaria (Sdzuy, Reference Sdzuy1955; Sdzuy et al. Reference Sdzuy, Hammann and Villas2001) and Spain (Havlíček & Josopait, Reference Havlíček and Josopait1972), but it is unknown from Armorica, Avalonia, North Africa and South America.

The Bohemian faunas group closely together with other faunas from Bavaria (Ba) and Spain (CA), which are characterized by the occurrence of Porambortis that has biogeographical significance (Harper et al. Reference Harper, Rasmussen, Liljeroth, Blodgett, Candela, Jin, Percival, Rong, Villas and Zhan2013), and more distantly with faunas in Iran (I2, I3, I5) and the late Tremadocian – early Floian faunas of the East Baltic (Ba1), characterized by the proliferation of the Thysanotos–Leptembolon Association. The later appearance of that association in the Baltoscandia and Alborz, Iran may indicate that Bohemia was a primary centre of dispersal of this linguliform fauna.

The Tremadocian (Cressagian–Migneintian) faunas of Avalonia (W1, W2) group with the Tremadocian–Floian faunas of the South Urals (SU1–3), mainly because of the co-occurrences of Acrotreta, Broeggeria, Eurytreta, Semitreta and Orbithele. Three of those genera (Broeggeria, Eurytreta and Orbithele) are common, but not entirely confined, to the cosmopolitan Broeggeria Association, since that association lived in dysaerobic environments with black mud accumulations that were widely dispersed (Bassett et al. Reference Bassett, Popov and Holmer1999). The observed affinity therefore reflects the similar biofacies characteristic of marginal environments, rather than any indication of close biogeographical or provincial affinities.

Another example of marginal biofacies with distinctive taxonomic compositions that overweigh biogeographical signatures is the monotaxic to oligotaxic lingulide communities of BA1, which can be assigned to the Lingulobolus Association. They inhabited mobile nearshore sands and muds and often occur together with the Cruziana and Skolithos ichnofacies (Emig & Gutiérrez-Marco, Reference Emig and Gutiérrez-Marco1997; Coke & Gutiérrez-Marco, Reference Coke and Gutiérrez-Marco2001). The lingulide shells characteristic of the Lingulobolus biofacies form extensive shell beds that are chiefly within quartzites laid down under rather shallow water, as exemplified by the Grès Armoricain of northwestern France itself. McDougall et al. (Reference McDougall, Brenchley, Rebelo and Romano1987) plausibly concluded that the Armorican Quartzite of the Central Iberia Zone of North Portugal was deposited in a variety of disconnected basins adjacent to various local land masses, and the quartzite is usually unconformable on Cambrian and earlier rocks, many of which had been disrupted by the late Precambrian and early Cambrian Cadomian Orogeny. We agree with that conclusion, which is in marked contrast with the enormous extent of an Armorican Quartzite sheet continuous over much of southern Europe and North Africa that had previously been wrongly postulated by some authors. That palaeogeographical condition favours the significant influx of siliciclastic sediments and seasonal freshwater runoff into the shallow basins, which created a favourable habitat for the strikingly distinctive large linguliform brachiopod assemblage.

All the Armorican Quartzites were previously assigned to be of ‘Arenig’ age, but are now considered as confined to middle and upper Floian time based on chitinozoan biozonation (Videt et al. Reference Videt, Paris, Rubino, Boumendjel, Dabard, Loi, Ghienne, Marante and Gorini2010). Figure 1 shows the distribution of the other chief sites that have yielded Mediterranean Province brachiopods in earliest Ordovician time (late Tremadocian, Floian and early Dapingian), as well as some other contemporary brachiopod sites (not discussed in detail in the present paper apart from Baltica) that have yielded brachiopods attributable to other provinces in lower latitudes to the north of the Mediterranean Province; these are briefly reviewed in the next section.

In North Africa and West Avalonia the Lingulobolus lingulide community was often monotaxic (Popov et al. Reference Popov, Legrand, Bouterfa and Ghobadi Pour2019); in southwestern Europe (France and Spain) and Cornwall, it also included Ectenoglossa, Lingulepis, Rafanoglossa, Tomasina and possibly Lingulella. The geographical area occupied by those lingulides was confined to subpolar latitudes of > 65° S. As pointed out by Emig & Gutiérrez-Marco (Reference Emig and Gutiérrez-Marco1997), the lingulid shell beds within the area occupied by the Lingulobolus biofacies was often deposited by catastrophic events, as well as significant freshwater influx into the environment. Because of the high latitudinal position of the shores inhabited by these lingulides, the major source of that freshwater influx can probably be attributed to seasonal ice and snow melting (Popov et al. Reference Popov, Holmer, Bassett, Pour and Percival2013 a). The Lingulobolus Association includes a significant proportion of burrowing lingulides, which are among the earliest examples of the ‘Lingula’-type associations of Ziegler et al. (Reference Ziegler, Cocks and Bambach1968) that proliferated later through the Palaeozoic Era and have continued until the present day.

10. Intermediate latitude and equatorial provinces

Between the two lowest-latitude Equatorial provinces and the Mediterranean Province there were a variety of brachiopod faunas, grouped here as the Intermediate Latitude Province. The most distinctive Intermediate Latitude assemblage is that which surrounded the substantial continent of Baltica, which included a host of endemic taxa including the orthide Lycophoria, the only genus in its family, and most of the genera within the superfamilies Clitambonitoidea and Gonambonitoidea (see also Section 8 above). In contrast, the quite different Asian Intermediate Latitude faunas included a community dominated by the large syntrophioid Yangtzeella, which was originally described from South China, but is now also known from the Taurides of Turkey (then an integral sector of Gondwana), Karakorum and Iran (Cocks & Torsvik, Reference Cocks and Torsvik2013), as well as some more cosmopolitan genera. In addition, to the west of Gondwana and largely in South America today, there were less distinctive assemblages that were largely dominated by more cosmopolitan genera. Also included in the Intermediate Latitude Province is what some authors, summarized by Harper et al. (Reference Harper, Rasmussen, Liljeroth, Blodgett, Candela, Jin, Percival, Rong, Villas and Zhan2013), termed the Celtic Province, although that term has been interpreted in different ways by a variety of authors and it has not been conclusively identified from any rocks older than the late Dapingian in age.

The shallow-water benthos in the Equatorial latitudes were divided into two provinces: the Laurentian Province, which was principally in North America, including the diverse brachiopod genera that have not been comprehensively revised since the classic paper by Ulrich & Cooper (Reference Ulrich and Cooper1938); and the Cathay–Tasman Province, which included that substantial sector of Gondwana that straddled the Equator, including Sibumasu (which remained an integral part of Gondwana throughout early Palaeozoic time), Australia, and the independent North and South China continents (Torsvik & Cocks, Reference Torsvik and Cocks2017).

11. Conclusions

During Early Ordovician time, the varied brachiopod benthic communities of the Mediterranean Province were extensively developed in the latitudes then > c. 55° S, largely at the margins of the large Gondwana continent but also in neighbouring terranes. The individual Early Ordovician Mediterranean faunas from temperate and high latitudes represent loose, commonly low-diversity associations of rhynchonelliform and linguliform brachiopods that were variable in taxonomic composition. They were often a mixture of cosmopolitan genera (mostly linguliforms) and some local endemics (both linguliforms and rhynchonelliforms). Some of them were probably the last occurrences of Cambrian (Furongian) lineages; others were neoendemics either representing local, short-lived genera, or taxa at the base of the Ordovician lineages, most importantly in the Andean Basin and Avalonia. The complex palaeogeographical patterns in the distribution of linguliform brachiopods across the high to temperate latitudes of Gondwana through Early Ordovician time can be explained by the gradual replacement within benthic communities of new taxa of the Cambrian Evolutionary Fauna (dominated by trilobites and linguliform brachiopods) within the early communities of the Palaeozoic Evolutionary Fauna, in which the rhynchonelliform brachiopods were major components, and with increasing numbers of locally abundant bryozoans, bivalves, ostracods and pelmatozoan echinoderms. The rhynchonelliform communities of the latter type first appeared in the Tremadocian Stage of the Andean basin (Benedetto et al. Reference Benedetto, Vaccari, Waisfeld, Sánchez and Foglia2009; Benedetto & Muñoz, Reference Benedetto and Muñoz2017) and the Alborz region of Iran. The latter can be considered as on the periphery of the major Early Ordovician biodiversity hotspot centred within the South China continent (Harper et al. Reference Harper, Rasmussen, Liljeroth, Blodgett, Candela, Jin, Percival, Rong, Villas and Zhan2013; Zhan & Jin, Reference Zhan and Jin2014). These rhynchonelliform-dominant communities were originally characteristic of the lithofacies of the upper offshore and onshore–offshore transition (BA3-4), which during late Tremadocian and early Floian time dispersed towards the shore (e.g. the Tarfaya Community in Argentina, Morocco and Alborz) and further down into the deeper shelves and basins. The Protambonites community inherited the position of the Furongian nearshore billingsellide communities, but it coexisted for some time with the Tarfaya Community (Popov et al. Reference Popov, Ghobadi Pour, Bassett and Kebria-Ee2009; Benedetto & Muñoz, Reference Benedetto and Muñoz2017), which had similar life strategies. By the Darriwilian Age, the latter had evolved in North Africa into the monotaxic, heterorthid Tissintia Community (Popov et al. Reference Popov, Legrand, Bouterfa and Ghobadi Pour2019), which formed a central feature of the Middle Ordovician Mediterranean Province, while polytoechiid communities nearshore had already disappeared by Dapingian time.

The Thysanotos–Leptembolon Association, distinctive in its large epibenthic lingulides, made its earliest appearance in Bohemia and then dispersed within temperate latitudes (mainly > 65°) on both sides of the narrow west branch of the Ran Ocean. Its proliferation in the environments of BA2 and BA3 can be considered as the ‘last stand’ of the Cambrian Evolutionary Fauna. In South Urals, Bohemia and Alborz they coexisted for some time, but were then gradually replaced by the rhynchonelliform brachiopod communities at the end of the Floian Age. In Baltica, the Thysanotos–Leptembolon Association was sharply replaced by a newly immigrant fauna of rhynchonelliform brachiopods, bryozoans, ostracodes and echinoderms in middle Floian time. A similar sharp replacement of the linguliform brachiopod associations by the benthic communities with characteristic features of the Palaeozoic Evolutionary Fauna occurred during early Floian time in East Avalonia (Cocks & Popov, Reference Cocks and Popov2019), with the rich mollusc–brachiopod association from the Ogof Hên Formation of SW Wales as a good example (Cope, Reference Cope1996).

Unlike the Thysanotos–Leptembolon Association, the Lingulobolus Association seems best considered as the earliest example of the ‘Lingula’-type associations that subsequently evolved within the community structure characteristic of the Palaeozoic Evolutionary Fauna. The Tremadocian–Floian high-latitude rhynchonelliform brachiopod faunas are relatively scarce, of low diversity and still not well known. In the Armorican terrane cluster they include only Poramborthis and Protambonites (Havlíček & Josopait, Reference Havlíček and Josopait1972; Villas, Reference Villas1995), while in the Tremadocian Stage of Morocco (the Lower Fezouata Formation) Havlíček (Reference Havlíček1971) listed only Saccogonum, Ranorthis and “Plectorthis”, although the latter generic identification is questionable. All those genera are also present in the Floian Upper Fezouata Formation, where they are accompanied by Angusticardinia, Paurorthis and Tarfaya, all taxa that occupied a more offshore position, meaning that their areas did not overlap with the lingulide communities.

Although the large inarticulated lingulides were confined to Early Ordovician time, the more diverse assemblages can be recognized as continuing aspects of the Mediterranean Province up to near the end of the Ordovician Period (early Hirnantian). However, after a more unified ecological regime during the latest Hirnantian Ice Age, from early Silurian to Early Devonian time, the Mediterranean Province was replaced in comparably higher-latitudes by the Malvinokaffric Province. Its distribution also reflects the fact that most of Gondwana had continuously remained over the South Pole since the Cambrian Period.

Acknowledgements

Many thanks to Trond Torsvik, Oslo, for palaeogeographical discussion and the creation of the map used here as the basis for Figure 1. The manuscript has benefited from the constructive reviews of Yves Candela, National Museums of Scotland, Edinburgh and Michal Mergl, University of West Bohemia, Pilsen. LRMC thanks the Natural History Museum, London and LEP the National Museum of Wales for facilities.

Declaration of interest

None.