1. Introduction and aim of study

Tsenkher (Mong. Цэнхэр), located deep in the Gobi-Altai region of Mongolia (43°38′41″N, 98°22′09″E), is a near-circular crater structure occurring in a structural basin (valley) (Figs 1, 2). The structure was originally identified as a possible impact crater on remote sensing data in 1997 (Komatsu, Olsen & Baker, Reference Komatsu, Olsen and Baker1998), and a brief visit to the structure by the Joint Mongolian–Russian–American Archaeological Expedition conducted in 1998 provided the first field observation of the structure and an opportunity to collect samples in the context of examining the impact hypothesis (Komatsu, Olsen & Baker, Reference Komatsu, Olsen and Baker1999).

Figure 1. Location map of the study site (Tsenkher structure) in the Gobi-Altai, Mongolia.

Figure 2. Regional view of the Gobi-Altai zone where the Tsenkher structure is located. (a) MrSID Landsat ETM image. (b) Simplified geological map based on a more detailed geological map (ODAPCR, 2003). The Lower Devonian strata are highlighted. These include the Ulgiyn Formation (D11ul, D12ul, D13ul, D14ul) and its adjoining undifferentiated strata (cD1 and rD1) occurring in Edrengiyn Nuruu to the north of the Tsenkher structure.

The diameter of the apparent raised rim is on average 3.7 km, and a breccia layer extending to approximately one crater radius or more outside of the crater rim suggests the presence of an ejecta blanket. The Tsenkher structure has been proposed to be either an impact crater or a maar/tuff ring based primarily on geomorphological observations from remote sensing data and the brief visit in 1998 (Komatsu et al. Reference Komatsu, Olsen, Ormö, Di Achille, Kring and Matsui2006). The problem of equifinality (different processes or causes may produce a similar landform) (e.g. Schumm, Reference Schumm, Rosswall, Woodmansee and Risser1988; Komatsu, Reference Komatsu2007) has been the fundamental problem in determining the origin of the Tsenkher structure.

A combined geophysical survey (gravity and magnetic) conducted during a focused expedition to the structure in the autumn of 2007 aimed to evaluate the two hypotheses. It showed that the structure is most likely rootless (i.e. impact origin), or having only a narrow volcanic pipe (i.e. maar/tuff ring) (Ormö et al. Reference Ormö, Gomez-Ortiz, Komatsu, Bayaraa and Tserendug2010). In addition to the geophysical signature, the solitary appearance, the predominantly sedimentary setting and the comparably large size of the Tsenkher structure are circumstances favouring an impact origin. In this paper we summarize the geological and geomorphological observations from the 2007 expedition, and report results of petrographic and geochemical studies of the samples obtained in the field. Besides searching for definitive evidence revealing the origin of the Tsenkher structure, we apply careful geological reasoning (Baker, Reference Baker2014) in order to reach a conclusion about the most probable formation mechanism of this structure. Furthermore, we discuss the peculiar rampart structure associated with the Tsenkher ejecta and also the degradation processes of the Tsenkher structure.

2. Method

Our research was conducted using satellite remote sensing data, field observation, and petrographic and geochemical sample analysis. The remote sensing data include Advanced Spaceborne Thermal Emission and Reflection Radiometer (ASTER), Landsat images and images made available on Google Earth, as well as digital elevation models (DEMs) from the Shuttle Radar Topography Mission (SRTM). Field observation was conducted during the expedition to the Tsenkher structure in October 2007. It served as a ground-truthing survey of the various lithologies and morphological features observed in the remote sensing data, as well as for the collection of rock samples that later were analysed in the laboratory. At the time of the expedition, the best and most detailed geological maps available to us were those of the Official Development Assistance Project of the Czech Republic (ODAPCR, 2003) at a scale of 1:200000 for a regional view and at a scale of 1:50000 for the area of the Tsenkher structure. These geological maps were used as a basis for our post-expedition compilation of remote sensing and field observation data for analysing the geological units and structural features of the Tsenkher structure.

The collected samples were examined with thin-sections under an optical microscope and in some cases with a scanning electron microscope (SEM) equipped with an energy dispersive spectrometer (EDS) for their petrographic characteristics, with special emphasis on finding evidence for shock metamorphism (e.g. planar deformation features in quartz, diaplectic glass) and other indications for high-energy events such as impact or volcanic processes (e.g. melt, spherules). Quartz grains displaying potential planar deformation features (PDFs) were further investigated using a universal stage (U-stage; cf. Reinhard, Reference Reinhard1931; Emmons, Reference Emmons1943) mounted on an optical microscope, and the crystallographic orientations of identified PDFs were determined according to the techniques described in Ferrière et al. (Reference Ferrière, Morrow, Amgaa and Koeberl2009).

Prompt gamma-ray analysis (PGA) and instrumental neutron activation analysis (INAA) were used for the determination of major, minor and trace elements. Descriptions of the PGA and INAA procedures can be found in Shirai & Ebihara (Reference Shirai and Ebihara2004). Platinum group elements (PGEs) are important for knowing the enrichment of extraterrestrial components in potential impactites relative to the lithologies of the putative target sequence. Five samples of different lithologies were subjected to NiS fire-assay for the determination of PGE abundances by inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (ICP-MS) using isotope dilution and external calibration methods (Shirai et al. Reference Shirai, Nishino, Li, Amakawa and Ebihara2003).

Noble gas isotopic compositions were measured for six samples of different lithologies in search of abnormal isotope compositions possibly derived from extraterrestrial material. Noble gases were measured with a modified-VG5400 (MS-III) mass spectrometer at the Geochemical Research Centre, University of Tokyo. 40Ar–39Ar age was determined for a vesicular melt sample with a modified-VG3600 mass spectrometer (Ebisawa et al. Reference Ebisawa, Sumino, Okazaki, Takigami, Hirano, Nagao and Kaneoka2004) at the Radioisotope Centre, University of Tokyo.

3. Geological setting of the study area

The Tsenkher structure is located in Bayankhongor aimag (aimag being an administrative unit equivalent to province) within the transition zone between the Gobi Desert and the Altai Mountain range (Figs 1, 2), which constitutes part of the Mongolian plateau. The region is a basin and range physiographic province. The mountain ranges originated mainly as Palaeozoic island arc assemblages (Sengör & Natal'in, Reference Sengör, Natal'in, Yin and Harrison1996) and were later subjected to transpressional deformation during late Cenozoic time (Cunningham et al. Reference Cunningham, Windley, Owen, Barry, Dorjnamjaa and Badamgarav1997; Cunningham, Reference Cunningham2005). The mountain ranges are bounded by strike-slip and thrust faults, and they are tectonically uplifted (Cunningham et al. Reference Cunningham, Windley, Owen, Barry, Dorjnamjaa and Badamgarav1997). The region also experienced intrusive events of late Palaeozoic age (Academy of Sciences of the Mongolian People's Republic, 1990; Geological Maps of Mongolia, 1990). The basin fills are Mesozoic, predominantly Jurassic to Cretaceous in age, but thin Quaternary, primarily alluvial materials overlie the Mesozoic sequence.

The study area is located c. 10 km further south of the southeastern part of the NW–SE-trending mountain range Edrengiyn Nuruu (Fig. 2). A geological map of the study area shows crustal materials ranging from Palaeozoic to Quaternary in age (ODAPCR, 2003). The Tsenkher structure is located in the middle of a 10–20 km wide NW–SE-trending basin (Tsenkher Valley) bounded by ranges of Palaeozoic and Mesozoic ages. The section of the basin where Tsenkher is positioned is slightly tilted towards the south, and the regional slope estimated from the SRTM DEM is approximately 0.02 (elevation change/distance). Numerous narrow and shallow S-trending channels dissect this slope, often ending in evaporitic basins. The drainage channels transport materials primarily from the Lower Devonian Ulgiyn Formation and its adjoining undifferentiated strata, both of which compose Edrengiyn Nuruu, and deposit the sediments in the basin. Bedrock sequences of Palaeozoic and Mesozoic ages crop out in windows within Quaternary sediments in the middle of the basin.

The Lower Devonian Ulgiyn Formation (D11ul, D12ul, D13ul, D14ul) and its adjoining undifferentiated strata (cD1 and rD1) of Edrengiyn Nuruu (Fig. 2b) include a complex mixture of volcanic and sedimentary rocks (ODAPCR, 2003). The exposed basin fills in the vicinity of the Tsenkher structure consists of flat-lying Cretaceous bedrock (K2bg: Baruungoyotin Formation) of clastic sedimentary deposits and of Quaternary alluvial materials, both of which were sourced from Edrengiyn Nuruu to the north. Sedimentary bedrock of Palaeozoic age is exposed in windows through the alluvial deposits, and it is dipping steeply (Fig. 3). This bedrock includes fine-grained sandstones, siltstones and cherts. The same Palaeozoic unit is classified as Carboniferous terrigenous sediments by others (ODAPCR, 2003).

Figure 3. The reddish sedimentary bedrock cropping out in the vicinity (west) of the Tsenkher structure. (a) The steeply dipping strata consist of fine-grained sandstones, siltstones and cherts. (b) Close-up of the sedimentary bedrock. Hammer for scale is 33 cm long.

The Tsenkher structure is located a few hundreds of kilometres west of the main Cenozoic volcanic zone of Mongolia, which runs from Khovsgol aimag of northern Mongolia to Khangai Plateau in central Mongolia, and continues south to the eastern Gobi-Altai (Barry et al. Reference Barry, Saunders, Kempton, Windley, Pringle, Dorjnamjaa and Saandar2003; Yarmolyuk et al. Reference Yarmolyuk, Kudryashova, Kozlovsky and Savatenkov2007; Bushenkova et al. Reference Bushenkova, Deev, Dyagilev and Gibsher2008). The closest known volcanic feature to the Tsenkher structure is located c. 47 km to the ENE. It is the 300 m wide and 70 m high Zurkh volcanic cone of black-grey pyroxene tephrite with a tentatively assigned Quaternary age (ODAPCR, 2003). Although the Gobi-Altai region including Bayankhongor aimag has experienced climatic changes throughout the Quaternary, the study area is today semi-arid with very limited vegetation coverage and with the presence of playas (Academy of Sciences of the Mongolian People's Republic, 1990; Komatsu et al. Reference Komatsu, Brantingham, Olsen and Baker2001, Reference Komatsu, Ori, Marinangeli, Moersch and Chapman2007a; Lehmkuhl & Lang, Reference Lehmkuhl and Lang2001). The past climatic variations are also indicated by the richness in Palaeolithic and Neolithic archaeological sites (Derevianko et al. Reference Derevianko, Olsen and Tsevendorj2000; Komatsu & Olsen, Reference Komatsu and Olsen2002; Komatsu et al. Reference Komatsu, Olsen, Ormö, Di Achille, Kring and Matsui2006).

4. Field observations

4.a. The rim

Komatsu et al. (Reference Komatsu, Olsen, Ormö, Di Achille, Kring and Matsui2006) estimated Tsenkher (Figs 4–7) to be a near-circular structure with a c. 3.6 km apparent rim-to-rim diameter based on SRTM DEM and RADARSAT image data. Here we can improve the old estimate by fitting a circle to the most representative rim crest visible in a Landsat TM image, as well as spot measurements on a Google Earth high-resolution image (Image NASA, Image © 2012 DigitalGlobe). The rim crest area has a varied width and the best fitting circle gives a diameter value of c. 3.7 km. The rim-to-rim diameter along two perpendicular profiles crossing the crater centre was also measured with a Global Positioning System (GPS) in conjunction with the geophysical survey carried out during the 2007 expedition with values confirming the remote sensing estimate (Ormö et al. Reference Ormö, Gomez-Ortiz, Komatsu, Bayaraa and Tserendug2010). We note that the rim-to-rim diameter may vary from 3.5 km up to c. 4.2 km in certain locations. The SRTM data indicate that the maximum rim height is c. 50 m above the top of the infill at the centre of the structure, and the height of the rim above the putative target surface taking account of the regional slope (0.02) gives a maximum height range of c. 70–80 m (Komatsu et al. Reference Komatsu, Olsen, Ormö, Di Achille, Kring and Matsui2006).

Figure 4. Tsenkher structure. (a) Google Earth image (Image NASA, Image © 2012 DigitalGlobe) of the Tsenkher structure. The positions of the topographic profiles in Figure 5 are indicated. (b) Simplified geological map. Modified from Komatsu et al. (Reference Komatsu, Olsen, Ormö, Di Achille, Kring and Matsui2006).

Figure 5. SRTM topographic profiles of the Tsenkher structure. The positions of the profiles are indicated in Figure 4a. The STRM grid spacing is c. 90 m. The relative vertical accuracy of the SRTM data is c. 6 m. Modified from Komatsu et al. (Reference Komatsu, Olsen, Ormö, Di Achille, Kring and Matsui2006).

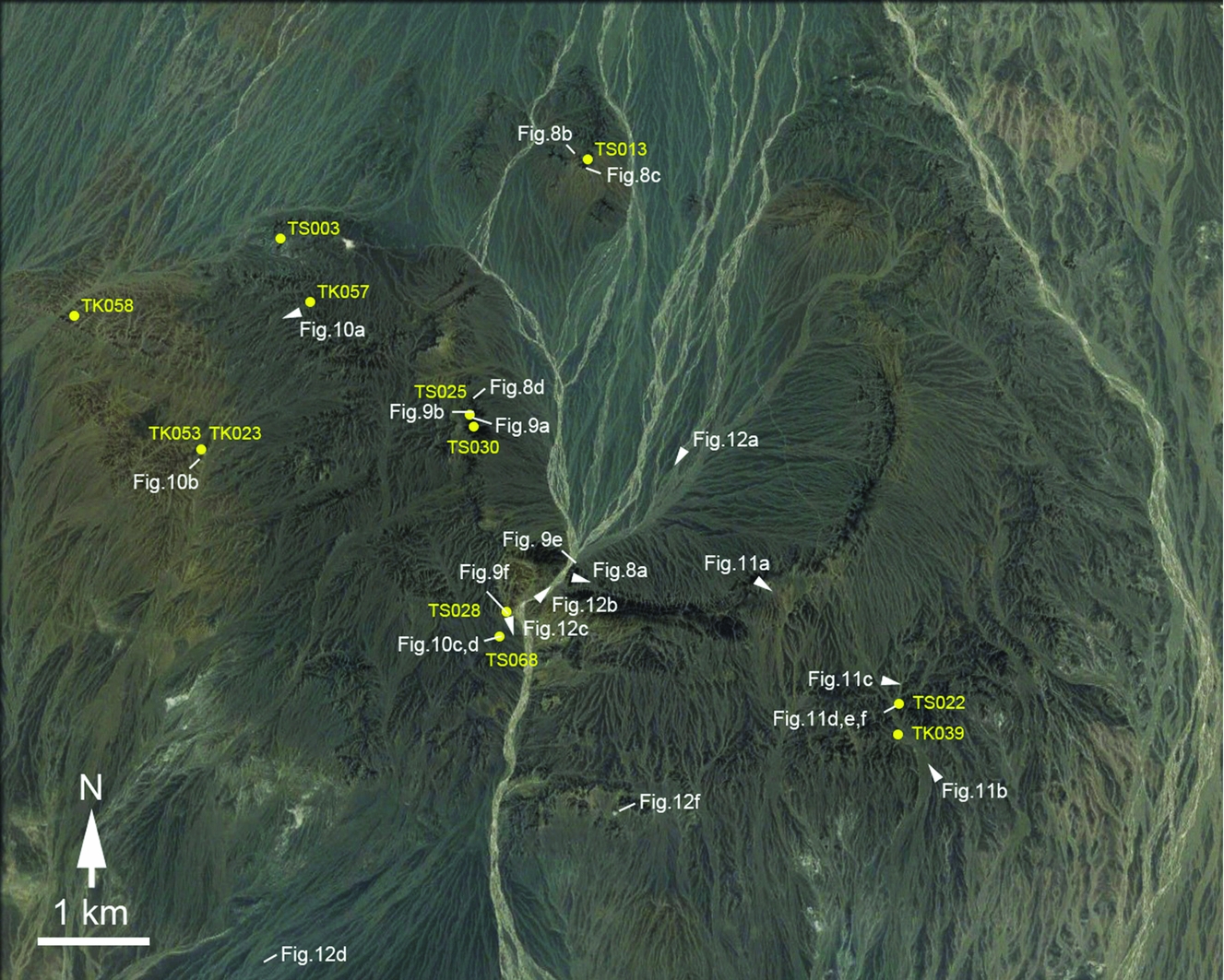

Figure 6. Details of the Tsenkher structure. Locations of photos in Figures 8–12 (except for Figs 9c, d and 12e) in this paper (the positions shown with arrows indicate viewing directions of the photos) are also indicated. Google Earth image (Image NASA, Image © 2014 DigitalGlobe). Locations of sampling sites (Table 1) are also indicated with dots.

Figure 7. Panorama views of the Tsenkher structure. (a) The raised rim and ejecta, view towards east. (b) Rampart (indicted by arrows) and raised rim (higher than the rampart, shown behind the rampart), view towards west.

The general geomorphological characteristics of the Tsenkher structure were examined in the field during the 2007 expedition, and they generally confirm the earlier observations done by Komatsu et al. (Reference Komatsu, Olsen, Ormö, Di Achille, Kring and Matsui2006). The rim of the structure is continuous except for the northern section where breaching seems to have allowed influx of alluvial materials from the north (Figs 4, 6). The lower part of the Tsenkher rim consists mainly of strongly fractured and tilted rocks (Fig. 8). The sequence of these rocks is similar to that of the more fine-grained varieties of the Palaeozoic sedimentary bedrock, mainly pale reddish-yellowish siltstone with sporadic chert-rich beds, exposed outside the Tsenkher structure (Fig. 3), implying that the lower part of the rim formed by structural uplift. The uplifted strata show an upward transition into a polymict breccia. The reddish-yellowish siltstone clasts dominate, giving the breccia the same general colour as the uplifted strata (Fig. 9a).

Figure 8. Rim characteristics. (a) South rim made of uplifted sedimentary bedrock. (b) North rim made of uplifted sedimentary bedrock, view towards north. (c) The contact (arrows) between the uplifted sedimentary bedrock and the overlying breccia layer (north rim). (d) The contact (arrows) between the uplifted sedimentary bedrock and breccia blocks (west rim). Hammer for scale is 33 cm long.

Figure 9. Lithology of the rim. (a) Polymict breccia dominated by the reddish-yellowish fine-grained clasts. (b) Dark and greenish breccia occurring on top of the rim. Note the rounded clasts. (c) Fresh cut of a dark and greenish breccia found just outside of the rim. Rounded and angular clasts are visible. (d) The surfaces of the dark and greenish breccias are frequently sculpted by wind, sometimes forming shapes similar to shatter cones. (e) Injection feature (arrow) found in a south rim cross-section. (f) A dark calcite vein 1 cm wide cutting across a siltstone just outside of the south rim. Hammer for scale is 33 cm long.

On top of the rim (Fig. 8c, d) and outwards in the ejecta layer the breccia frequently shows a dark greenish colour, partially due to desert varnish, and fresh cuts of the breccias show dark-coloured, often rounded clasts, and reddish or yellowish angular clasts (Fig. 9b, c). The rounded clasts are mainly of volcanic origins, and the angular clasts are sedimentary fragments. The surfaces of the dark greenish breccias are frequently sculpted by wind (Fig. 9d), forming in some cases quasi-triangular shapes resembling shatter cones (a type of shock feature associated with impact structures). However, the quasi-triangular shapes have hard and resistant clasts on their points, confirming their wind erosional origin.

The eroded rim, in places, shows fractured sedimentary bedrock cut by up to several metres long and a few centimetres to decimetres wide breccia dykes, possibly originating as injections (Fig. 9e). In a location in the exposed lower exterior parts of the southern sector of the elevated rim c. 500 m outside its crest, fractured siltstones are cross-cut by millimetres to centimetres wide, dark, coarse-crystalline calcite veins (Fig. 9f). At a low hill within the disrupted northwestern sector of the rim a small amount of a clast-rich melt rock with millimetre-sized glassy spherules was encountered (see Section 5).

4.b. Ejecta

Originally called ‘circum deposits’ by Komatsu et al. (Reference Komatsu, Olsen, Ormö, Di Achille, Kring and Matsui2006), the Tsenkher ejecta exhibits different morphological characteristics on the western and eastern sides of the crater. The western side is continuous and rugged (Figs 4, 6), and it extends 1–1.7 times the rim radius distance away from the rim. Locally, the western ejecta layer appears to overlie unconformably the exposed bedrock.

On the eastern ejecta layer, a concentric outer ridge (Komatsu et al. Reference Komatsu, Olsen, Ormö, Di Achille, Kring and Matsui2006) with a variable width range (from hundreds of metres up to 1 km) is identified (referred to as a ‘rampart’, see Section 4.c), with its inner edge beginning c. 1 km from the crater rim (Figs 4, 6). The ejecta surface between the rim and the outer ridge is covered with desert pavement, and its surface gently dips down and outwards.

The outwards increase in the amount of dark and greenish breccia (Fig. 10a) also seems to make the ejecta appear harder and more resistant to erosion. In the western part of the ejecta field, this colouring makes the breccia (i.e. ejecta) distinguishable from the underlying Palaeozoic sedimentary bedrock that is reddish-yellowish in colour (Fig. 10b). The unit boundary can be drawn using satellite imagery (Komatsu et al. Reference Komatsu, Olsen, Ormö, Di Achille, Kring and Matsui2006) as we in this field study can verify that the proposed ejecta extent clearly coincides with the outer limit of the breccia distribution. For most of the western and southern crater exterior the breccia deposit extends up to about one crater radius or more outside the rim. However, on the eastern side, this variety of the ejecta is concentrated in the concentric outer ridge (called the rampart structure in this paper, see Section 4.c).

Figure 10. Ejecta characteristics. (a) Undulating surface of the ejecta. (b) The contact (arrows) between the ejecta (visible in the background at the higher position) and the underlying sedimentary bedrock. (c) The dark clasts (melt) in polymict breccias exhibit contact alteration of the matrix (arrow). (d) A vesicular melt clast within a polymict breccia occurring in the ejecta layer just outside the rim. Note the chert clast sticking out from the melt.

At one location within the ejecta layer to the south of the structure there is a several tens of metres wide exposure of a polymict breccia including dark clasts exhibiting contact alteration of the matrix (Fig. 10c). The dark fragments are found in thin-sections to be melt fragments within a siltstone matrix. Within the breccia there are also up to several decimetre wide melt clasts with a scoria-like vesicular texture (Fig. 10d). Thin-sections confirm the material to be recrystallized glass. The polymict breccia with melt and glassy fragments complies with the definition of an impact melt-bearing breccia (cf. suevite) (Stöffler & Grieve, Reference Stöffler and Grieve1994, Reference Stöffler, Grieve, Fettes and Desmons2007).

4.c. Ejecta rampart structure

The prominent ridge feature positioned c. 1–2 km outside of the crater rim on the eastern side (Figs 4–6, 7b, 11a, b, c, d) was noted in earlier remote sensing and field studies by Komatsu, Olsen & Baker (Reference Komatsu, Olsen and Baker1999) and Komatsu et al. (Reference Komatsu, Olsen, Ormö, Di Achille, Kring and Matsui2006) who called it a ‘raised outer rim’ or ‘outer ridge’. We here choose to refer to this feature as a ‘rampart’ since it strongly resembles rampart ridges observed in a certain morphological variety of ejecta blankets associated with many Martian impact craters (e.g. Barlow et al. Reference Barlow, Boyce, Costard, Craddock, Garvin, Sakimoto, Kuzmin, Roddy and Soderblom2000; Mouginis-Mark & Baloga, Reference Mouginis-Mark and Baloga2006; Komatsu et al. Reference Komatsu, Ori, Marinangeli, Moersch and Chapman2007b). The Martian impact craters with such a feature are commonly called rampart craters. The Tsenkher rampart's maximum height is < 10 m relative to the surface facing the crater, but up to 50 m high relative to the outside, rugged surroundings and smoother plains beyond (Figs 4, 5) (Komatsu et al. Reference Komatsu, Olsen, Ormö, Di Achille, Kring and Matsui2006). Some Martian rampart craters exhibit double-layer ejecta (DLE) structures with the inner layer associated with a more pronounced rampart, and the outer layer sometimes with its own rampart extends outside of the inner layer (e.g. Barlow et al. Reference Barlow, Boyce, Costard, Craddock, Garvin, Sakimoto, Kuzmin, Roddy and Soderblom2000; Mouginis-Mark & Baloga, Reference Mouginis-Mark and Baloga2006; Komatsu et al. Reference Komatsu, Ori, Marinangeli, Moersch and Chapman2007b). The Tsenkher ejecta on the eastern side could also be a double ejecta layer structure since the ejecta appears to extend outside of the rampart (i.e. the rugged surroundings) for up to c. 1.5 km (Figs 4–6). Alternatively, the ejecta outside of the rampart may simply represent the discontinuous thin distal ejecta material commonly observed with Martian single-layer ejecta (SLE) craters.

Figure 11. Rampart morphology and facies. (a) Rim, rampart and ejecta in between them. (b) View of the rampart from the surrounding plain. (c) Undulating rampart surface. (d) A cross-section of the rampart. Note that the larger clasts tend to accumulate near the top surface. (e) The rampart cross-sections exhibit chaotic facies with abundant breccia clasts up to metre-size boulders. (f) Some clasts in the breccia are themselves made up of a melt-bearing breccia causing a ‘breccia-in-breccia’ appearance of the deposit. See the position of this clast in (e) (annotated as melt-rich clast). The thin-section taken from the breccia clast in the centre of this photo is characterized by flow band structure shown in Figure 13a. Hammer for scale is 33 cm long.

Close-up examination of the outcrops of the Tsenkher rampart reveals a mixed, non-stratified facies of large angular fragments (gravels to up to metre-scale boulders) and a poorly consolidated fine-grained (sandy) matrix (Fig. 11d). Blocks of well-consolidated breccia with a similar appearance to the polymict, primarily chert-rich breccia of the proximal ejecta at the rim, as well as blocks of the suevite-like rock described above, do also occur in the mixed deposit, thus giving a ‘breccia-in-breccia’ appearance notwithstanding the mostly unconsolidated appearance of the host material of the rampart ejecta deposit (Fig. 11e, f). Both matrix- and clast-supported varieties exist, but no clear stratification is observed. Larger clasts tend to concentrate in the upper portions of the rampart (Fig. 11d). Thus, the mixed, non-stratified facies is best interpreted as that of a debris-flow deposit. The existence of melt fragments in the blocks indicates that rapid consolidation must have occurred before further emplacement by the debris flow. The concentration of large clasts in the upper portions may be explained by the kinetic sieving process (Middleton, Reference Middleton and Lajoie1970; Pouliquen & Vallance, Reference Pouliquen and Vallance1999).

4.d. Erosional and depositional landforms

The Tsenkher structure appears to be a feature degraded from its original form. The northern section of the rim is discontinuous. This observation can be explained by the fluvial erosion due to the activity of the narrow and shallow S-trending channels that cross the structure from north to south, although their run may have been controlled by pre-existing variations in the rim morphology (non-symmetrical excavation flow due to factors such as oblique impact, structural variations in the target, etc.).

A prominent degradation feature is the spillway cutting across the south rim and the southern ejecta layer (Figs 4, 6, 12a, b, c). The spillway ends south of the ejecta layer in a distributary fan with shifting drainage channels, currently positioned on the east side of the fan (Figs 4, 6). The rest of the fan's surface is covered with desert pavement of dark-coloured pebbles and gravels (Fig. 12d). The transported sediments are deposited in a playa basin (Fig. 4). The boundary between the fan and the playa surface is clearly marked by the dark-coloured pebbles and gravels of the fan, and lighted-toned sands in the playa (Fig. 12e).

Figure 12. Landforms associated with the Tsenkher structure. (a) Shallow channels crossing the crater floor. Note the desert pavement. (b) The spillway cutting the south rim. It is characterized by a braided pattern. (c) The spillway cutting across the ejecta towards the south. (d) The desert pavement developed over the fan that is formed by the sediments transported through the spillway. (e) The terminus of the fan and the playa surface. (f) A small cone found in the ejecta area to the south of the Tsenkher rim. It appears to be a type of spring deposit but its details are not known.

In the ejecta layer to the south of the crater there is a 30–40 m wide, light-toned mound that it is capped with dark brownish coloured pebbles and gravels (Fig. 12f). No analysis has yet been conducted on samples from this mound. The post-fieldwork examination of satellite images reveals that other light-toned materials may exist in the vicinity though in very limited aerial extent. Future works should address the origin of the mound and the light-toned materials in relation to the Tsenkher formation and its post-formational history.

5. Petrographic analysis under optical microscope, elemental analysis, noble gas analysis

The samples studied and reported here are summarized and listed in Table 1. Sample numbers referred to in the text are listed also in the table. Their collection sites are indicated in Figure 6.

Table 1. List of Tsenkher samples referred to in the text

5.a. Microscopic observations

Our microscopy study reveals that breccia samples collected in the ejecta layer are characterized by clasts of variable size and composition. Some breccia samples exhibit a melt matrix (Fig. 13a, TS022) characterized by flow bands (cf. French, Reference French1998). Others have melt fragments in a clastic matrix (i.e. the suevite-like breccia) (Fig. 10c). As mentioned above, the clasts in the studied breccias are ‘sedimentary’ (e.g. siltstone, chert, fossils), ‘volcanic’ (mostly andesitic) or occasionally up to several decimetre-sized microcrystalline recrystallized melt or even glass fragments. The chert clasts can reach from millimetres up to tens of centimetres in size (Fig. 10d), but the volcanic clasts are in general smaller with the maximum range of millimetres (Fig. 13b, TK053). The majority of the sedimentary clasts are cherts very similar to the ones in the sedimentary bedrock exposed west of the Tsenkher structure and at its rim, but there are also occasional occurrences of fossil fragments (Fig. 13c, TS003, TS025).

Figure 13. Petrographic observations (under optical microscope) of samples from the Tsenkher structure. (a) Flow band structure (aligned microcrystals) occurring in a breccia clast sampled in the rampart (see Fig. 11e, f). Sample TS022. Thin-section (open nicol). (b) Sub-rounded to rounded clasts are common in breccias. Sample TK057. Thin-section (open nicol). (c) Fossils are fairly common in breccias. This fossil in the centre of the photo is tentatively identified as a Bryozoa. Sample TS025. Thin-section (open nicol). (d) Calcite (with cleavage) veins cutting across siltstone (see Fig. 9f). Sample TS028. Thin-section (open nicol).

In contrast to the often angular melt fragments seen in the suevite-like breccias most of the volcanic clasts are sub-rounded to rounded (Fig. 13b, TK023, TK053, TK057, TS025), implying defacement likely before their incorporation into the breccia. The Lower Devonian Ulgiyn Formation (D11ul) and undifferentiated strata (cD1 and rD1) in Edrengiyn Nuruu to the north of the Tsenkher structure is extremely rich in volcanic rocks of andesitic to basaltic compositions (ODAPCR, 2003). Hence, it is reasonable to assume a provenance from these areas. Even today, many N–S-trending drainage channels originating from D11ul and cD1 transport well-rounded debris to the area of the Tsenkher structure. It is also probable that the volcanic clasts seen in the breccia samples originated from the Baruungoyotin Formation (K2bg) that likely resulted from the deposition of the Ulgiyn Formation and its adjoining strata during Cretaceous time.

Palaeozoic fossils are occasionally present in Tsenkher samples (e.g. Fig. 13c, TS003, TS025). They are tentatively identified as Bryozoa. In the chert, siltstone and fine-grained sandstone bedrock exposed to the west of the Tsenkher structure there are no visible fossils even under the microscope. Therefore, it is difficult to envision the local surface bedrock as the source of these fossils. We believe that the fossils found in our breccia samples were derived from either deep-seated Palaeozoic (or Mesozoic) bedrock potentially rich in those fossils, or existed as detritus transported from Edrengiyn Nuruu, north of the Tsenkher structure. ODAPCR (2003) reported the presence of taxonomically rich shallow-water fauna including fenestrate Bryozoa in the Lower Devonian Ulgian Formation (D13ul) and its adjoining unit (cD1), both of which are main constituents of Edrengiyn Nuruu. This is also consistent with the inference that the rounded volcanic clasts mentioned above originated from the Ulgiyn Formation and its adjoining undifferentiated strata that existed in situ prior to the Tsenkher formation.

The up to several centimetres wide calcite veins observed cutting across the fractured siltstones in the lower parts of the outer reaches of the elevated rim are nearly black in outcrop, but in thin-section their compositions of large millimetre- to centimetre-scale calcite crystals become evident (Fig. 13d, TS028). The position at the rim and the large crystals could indicate a formation from hydrothermal circulation of fluids.

Some samples obtained from the north rim contain spherules with various sizes from a few tens of microns to a couple of millimetres in diameter (Fig. 14a, b, TS013). These spherules are embedded, sometimes with reaction rims, in rapidly crystallized melt rock characterized by the ophitic texture of the feldspar laths and up to millimetre-sized plagioclase phenocrysts.

Figure 14. Microscopic spherules associated with a Tsenkher sample (TS013). (a) Spherules millimetres in diameter are found in breccia samples from the north rim. The round and dark spherules are embedded in rapidly crystallized melt rock characterized by the ophitic texture of feldspar laths and up to millimetre-sized plagioclase phenocrysts. (b) Thin-section view of one of the spherules.

Some melt clast samples (e.g. TS068) (Fig. 10d) are highly vesiculated scoria-like material. It consists of a homogeneous glassy matrix with fine-grained dendritic crystals of mainly plagioclase and some mafic minerals (pyroxene and olivine). While the grain sizes of the plagioclase are in the tens to a few hundred microns, those of the mafic minerals are less than a few tens of microns. One vesicular melt sample (TS068) is examined in detail with EDS equipped SEM (Table 2). The chemical composition of this melt is 61–63 vol.% SiO2, 6–7 vol.% Na2O+K2O, indicating a silica-rich source rock with an andesitic composition. Areas with abundant semi-spherical grains (< a few microns in size) are noted within the melt (Fig. 15). Measurements of these grains (with some surrounding glassy matrix) exhibit high Fe contents (Table 2).

Table 2. Chemical compositions of a vesicular melt sample (TS068) with or without Fe-rich grains, determined with EDS equipped with SEM

Analyses #1, 4, 5, 6 and 8 are glassy matrix without Fe-rich grains.

Analyses #3 and 9 are Fe-rich grains with some glassy matrix.

n.d. – not detected.

Figure 15. Fe-rich grains in a vesicular melt sample (TS068). (a) An area with abundant Fe-rich grains. Bright Fe-rich semi-spherical grains (< a few microns in size) are ubiquitously distributed in the glassy matrix of this area. What look like spherules (dark circular features) are not spherules. Differences in darkness in backscattered electron imaging (BEI) is likely due to the presence of voids underneath the polished surface. (b) Small Fe-rich euhedral grains (1–3 microns). Euhedral crystals of Fe-rich bright phases indicate that they are liquidus phases.

Shock metamorphic features in the form of PDFs were found in one quartz grain in a fine-grained breccia sample (TS030) obtained from the western part of the rim (Fig. 16). The grain contains two sets of PDFs. The sets are non-penetrative, i.e. only present in the outer margins of the host grain, undecorated and are both oriented parallel to crystallographic planes typical for impact-related shock metamorphosed quartz: r, z {1011} orientations (Fig. 16; Stöffler & Langenhorst, Reference Stöffler and Langenhorst1994; Ferrière et al. Reference Ferrière, Morrow, Amgaa and Koeberl2009 and references therein).

Figure 16. Thin-section photomicrograph (uncrossed polars) of part of the shocked quartz grain from sample TS030, displaying two undecorated PDF sets, both oriented parallel to {1011} orientations.

5.b. Elemental abundances

PGA and INAA, and ICP-MS results for bulk chemical compositions of five Tsenkher samples analysed in this study are given in Tables 3 and 4, respectively. A sedimentary breccia clast (TK039-clast) is probably a fragment of the sedimentary target and it has a high Si content similar to that of the sedimentary bedrock sample (TK058). The melt (TS022), breccia (TK039-breccia matrix) and vesicular melt (TS068) samples from Tsenkher in comparison to the sedimentary target sample (TK058) are all somewhat enriched in Fe but depleted in Na. Major element compositions of melt (TS022) and vesicular melt (TS068) are similar, implying an Fe-rich common precursor. Chondrite (CI)-normalized PGE abundance patterns for the five Tsenkher samples are shown in Figure 17, where the upper continental crust (Park et al. Reference Park, Hu, Gao, Campbell and Gong2012) is also indicated for comparison. The bedrock sample (TK058) has similar CI-normalized PGE abundances to that of the upper continental crust. Compared with the bedrock sample (TK058), the melt sample (TS022) and breccia samples (TK039-breccia matrix and clast) have similar CI-normalized PGE abundance patterns to that of the target sample, implying that the contribution of meteoritic components is not significant when the chondritic materials are assumed to be an impactor for which the PGE pattern should be flat (e.g. Koeberl, Reference Koeberl, Grady, Hutchinson, McCall and Rothery1998). As shown in Figure 17, although the CI-normalized PGE abundance pattern in a vesicular melt sample (TS068) is similar to those of the other four samples, this melt sample has higher PGE abundances (approximately an order of magnitude with respect to the sedimentary bedrock). Ni and Co abundances of this melt sample (TS068) are also higher than those for the bedrock sample (TK058) (Table 2). As Fe-rich grains (having also elevated Co contents) were observed in the same vesicular melt sample (TS068) (Table 1), the enrichments of Ni, Co and PGEs are likely linked to the Fe-rich grains.

Table 3. Major, minor and trace elements abundances in Tsenkher samplesFootnote *

* Errors are due to counting statistics (1σ) in gamma-ray counting.

Table 4. Platinum group elements for Tsenkher samples obtained by ICP-MS coupled with NiS fire-assayFootnote *

* Uncertainties for individual values are due to standard deviations in repeated measurements (n = 20) in ICP-MS.

Figure 17. CI-normalized PGE abundances for Tsenkher samples. For comparison, upper continental crust (UCC) (Park et al. Reference Park, Hu, Gao, Campbell and Gong2012) is also shown.

5.c. Noble gas isotopic compositions and 40Ar–39Ar dating

Noble gases (He, Ne, Ar, Kr, Xe) were measured for six samples: breccia (TK039-breccia matrix), sedimentary clast within breccia (TK039-clast), breccia with spherules (TS013), vesicular melt (TS068), breccia with melt inclusion (TS022) and chert-rich sedimentary bedrock (TK058). Noble gases were extracted from the samples at the heating temperature of 1800°C. A stepwise heating experiment was applied for the breccia sample (TK039-breccia matrix), because a high 3He/4He of (5.0±0.2) × 10−6 observed for the sample at the total melting experiment (Table 5) suggested the presence of extraterrestrial material in this sample. Noble gas elemental and isotopic compositions of all the samples except for the high 3He/4He, however, did not show evidence of extraterrestrial materials in the samples. The vesicular melt sample (TS068) has a low concentration of radiogenic 40Ar, 5.75×10−7 cm3STP/g, much lower than that in other samples measured in this work (3.9×10−6 to 2.8× 10−5 cm3STP/g; Table 5). If we assume a K concentration of 3 wt% for this sample, a young K–Ar age of about 5 Ma is calculated. The observation indicates that the rocks originally located in this area have ages older than c. 100 Ma.

Table 5. Concentrations of noble gases (He and radiogenic Ar) and He isotopic ratios for Tsenkher samples

To verify the young K–Ar age, we applied the 40Ar–39Ar method to the vesicular melt sample (TS068). A plateau age of 4.9±0.9 Ma is obtained in the temperature range from 850 to 1300°C, with c. 90% release of total 39Ar from K.

6. Discussion

6.a. Origin: volcanic v. impact

An explosive origin (such as impact, maar/tuff ring or caldera) of the Tsenkher structure is advocated based on the following observations: (1) near-circular (uplifted) rim, (2) presence of breccia, (3) unconformable relationship between the breccia and underlying sedimentary rocks in a breccia layer (ejecta layer) extending to more than a crater radius outside the rim, (4) presence of breccia with melt fragments, and (5) evidence of shock metamorphism. Therefore, plutonic intrusion and salt tectonics are unlikely origins.

The ODAPCR geological map reports the Tsenkher structure to be composed of andesites, basalts and tuffs of Lower–Middle Carboniferous age, and the structure is concluded to be an eroded volcano (ODAPCR, 2003). However, our field observations and sample analysis contradict these identifications. Our petrographic work identified ‘volcanic’ fragments, but as sub-rounded to rounded clasts in breccias (e.g. Fig. 13b), inferring that the volcanic clasts likely originated from fluvial deposits derived from the Lower Devonian Ulgiyn Formation and/or its adjoining undifferentiated strata. In the case of a volcanic origin of the Tsenkher structure, the polymict breccia with vesicular scoria-like melt clasts (Fig. 10d) as well as other melt clasts (e.g. Fig. 13a) could be volcanic products. Nevertheless, a caldera hypothesis (and also plutonic intrusion) is unlikely owing to the apparent lack of a large magmatic chamber underneath the structure (Ormö et al. Reference Ormö, Gomez-Ortiz, Komatsu, Bayaraa and Tserendug2010). The 40Ar–39Ar age of c. 5 Ma for the vesicular melt sample is likely the formation age of Tsenkher, which is inconsistent with a Carboniferous age. If maintaining a volcanic interpretation, the Tsenkher structure would most likely be a maar/tuff ring (Fig. 18a) as hypothesized by Komatsu et al. (Reference Komatsu, Olsen, Ormö, Di Achille, Kring and Matsui2006), considering its near-circular rim and the presence of ejecta and the absence of lava except for the rare occurrences of melt clast breccias reported here.

Figure 18. Comparison with maars/tuff rings or impact craters. (a) El Elegante is a maar crater located in the Pinacate volcanic field, the State of Sonora, Mexico. Other maar craters occur in the vicinity. The rim-to-rim diameter is c. 1.6 km. Google Earth image (Image @ 2012 GeoEye, Image © 2012 DigitalGlobe). (b) Lonar is an impact crater located in the State of Maharashtra, India. The rim-to-rim diameter is c. 1.8 km. Google Earth image (Image © 2012 GeoEye).

Volcanic landforms in the world occur generally in groups and the majority of documented maars/tuff rings are no exceptions in this regard. Thus, if the volcanic origin is valid, the geographical isolation of a large 3.7 km diameter maar/tuff ring from other volcanic features needs to be explained. An elevated magnetic anomaly some 5 km northeast of Tsenkher (Ormö et al. Reference Ormö, Gomez-Ortiz, Komatsu, Bayaraa and Tserendug2010) may represent an intrusive body at depth, but this body does not coincide with the position of Tsenkher. The closest known volcanic feature, the 300 m wide structure called Zurkh of pyroxene tephrite composition (47 km ENE of Tsenkher), is of presumed Quaternary age (or as old as Palaeogene since it penetrates through Jurassic and Cretaceous formations) (ODAPCR, 2003), and appears to be an eroded out laccolith or volcanic neck, or a cinder cone (Fig. 19f). Other relatively close volcanic features appear to be patches of degraded lava fields and other volcanic features (e.g. eroded out laccoliths or volcanic necks, or cinder cones) distributed in the eastern Gobi-Altai (Figs 19, 20). These features include the 500 m wide Khatan suudal (44°30′28″N, 101°20′33″E) located c. 250 km to the ENE direction, and other groups of volcanic features located 300–350 km ENE to ESE of the Tsenkher structure. These volcanic features are too far away to be directly linked with the Tsenkher structure. The compositions of these volcanic features are reported to be trachyandesite to trachybasalt or basanite (Barry et al. Reference Barry, Saunders, Kempton, Windley, Pringle, Dorjnamjaa and Saandar2003; Yarmolyuk et al. Reference Yarmolyuk, Kudryashova, Kozlovsky and Savatenkov2007), similar to the andesitic composition of the vesicular melt sample found at Tsenkher. However, none of them shows geomorphological characteristics resembling structures from explosive volcanism such as calderas, composite volcanoes and maars/tuff rings (Fig. 19), although the laccolith or volcanic necks are eroded landforms originated by magmatism and it is not certain what kind of volcanic features they are derived from. Their reported ages (Bogd: 32 Ma, Sevrei: 33 Ma, Noyon: 31–37 Ma, Khatan suudal: 32 Ma, Durveldzhin: 88 Ma, Yarmolyuk et al. Reference Yarmolyuk, Kudryashova, Kozlovsky and Savatenkov2007; Bogd: 30 Ma, Sevrei: 32–33 Ma, Barry et al. Reference Barry, Saunders, Kempton, Windley, Pringle, Dorjnamjaa and Saandar2003) are also inconsistent with the age of the Tsenkher melt sample (~ 5 Ma) (Fig. 20). If the Tsenkher structure indeed originated from volcanism, it would mean that a single isolated large explosion, probably a type of phreatomagmatic eruption, suddenly produced one of the largest maars or tuff rings known in the world tens of millions of years after other volcanic eruptions in the region. In addition, the eruption must then have occurred without the presence of a sizable magma chamber, and without any continued eruptions after the formation of the crater.

Figure 19. Volcanic landforms in the known volcanic fields located in the Gobi-Altai. They appear to be patches of degraded lava fields and other volcanic features (e.g. eroded out laccoliths or volcanic necks, or cinder cones). (a) Durveldzhin. Google Earth image (Image © 2012 GeoEye, © 2012 Mapabc.com, © 2012 Google). (b) Noyon. Google Earth image (Image © 2012 GeoEye). (c) Sevrei. Google Earth image (© 2012 Cnes/Spot Image, Image © 2012 DigitalGlobe, © 2012 Google). (d) Bogd. Google Earth image (© 2012 Cnes/Spot Image, Image © 2012 DigitalGlobe, © 2012 Google). (e) Khatan suudal. Google Earth image (Image © 2012 GeoEye, © 2012 Google). (f) Zurkh. Google Earth image (Image © 2012 TerraMetrics, © 2012 Google).

Figure 20. Known volcanic fields located in the Gobi-Altai and their ages. The base map is a MrSID Landsat ETM image. The indicated ages are cited from Yarmolyuk et al. (Reference Yarmolyuk, Kudryashova, Kozlovsky and Savatenkov2007).

The Tsenkher structure lacks other characteristics that are indicative for known maars/tuff rings. Maars/tuff rings often show structural control (e.g. positioned along faults) (Gevrek & Kazanci, Reference Gevrek and Kazanci2000), which is not observed at Tsenkher. The bedded base surge deposits commonly associated with maars/tuff rings (e.g. Fisher & Waters, Reference Fisher and Waters1970) are not observed at Tsenkher either, although we cannot totally rule out the possibility that such deposits have been removed owing to erosion. Maars/tuff rings do not notably exhibit structurally uplifted pre-existing strata (De Hon, Reference De Hon, Fitzsimmons and Balk1965; Gutmann, Reference Gutmann1976), and very large clasts in their ejecta are rare. This is inconsistent with Tsenkher where the pre-existing sedimentary bedrock layers are uplifted and large clasts up to metre scale are commonly observed in the ejecta layer. All these arguments make the Tsenkher structure a very unusual volcanic landform if of volcanic origin.

Given the arguments against a volcanic origin listed above, the impact hypothesis (Fig. 18b) seems a more viable alternative. It is further supported by the rootless structure seen in the geophysical survey (Ormö et al. Reference Ormö, Gomez-Ortiz, Komatsu, Bayaraa and Tserendug2010), as well as geological and geomorphological similarities to known impact craters of similar size. The apparent 3.7 km diameter of Tsenkher places the structure in the range of a simple to complex crater transition (2–4 km; Grieve, Reference Grieve1987) in sedimentary target rocks. The observed variation in rim-to-rim diameter (from 3.5 km up to c. 4.2 km) (Figs 4–6, 8a) could be explained by incomplete development of slump terraces during the modification stage (Melosh, Reference Melosh1989). The outer ridge morphology observed on its eastern side is similar to rampart craters on Mars (e.g. Komatsu et al. Reference Komatsu, Olsen, Ormö, Di Achille, Kring and Matsui2006, Reference Komatsu, Ori, Rossi, Di Lorenzo and Neukum2007b), whose formation has been attributed to fluidization of a water-rich target layer and ejecta materials, or to atmospheric entrainment and deposition of ejected materials (see Section 6.b).

The presence of a quartz grain displaying PDFs oriented along crystallographic planes typical for shock metamorphosed quartz in a breccia sample obtained from the ejecta at the crater rim (Fig. 16) gives further support for an impact origin. For unequivocal evidence a statistical study of PDF planes in more grains is needed. This work is in progress. The geochemical studies presented in this paper do not provide unequivocal evidence for an impact origin of the Tsenkher structure. However, the PGE abundances in a vesicular melt sample (Fig. 10d) show an elevated trend with respect to the sedimentary bedrock of the area (approximately an order of magnitude) (Fig. 17), and noble gas analysis of one breccia sample yielded an elevated 3He/4He value of (5.0±0.2) × 10−6 indicative of an extraterrestrial component. The general lithological and petrographic characteristics of Tsenkher are in good agreement with known impact structures (e.g. Fig. 21), including injection features (Sturkell & Ormö, Reference Sturkell and Ormö1997; Poelchau, Kenkmann & Kring, Reference Poelchau, Kenkmann and Kring2009), mixed, non-stratified ejecta facies (Kenkmann & Schönian, Reference Kenkmann and Schönian2006), suevite (Stöffler & Grieve, Reference Stöffler and Grieve1994), vesicular melt clasts (Osae et al. Reference Osae, Misra, Koeberl, Sengupta and Ghosh2005) with Fe- and Co-rich grains and spherules (Misra et al. Reference Misra, Newsom, Prasad, Geissman, Dube and Sengupta2009; Maloof et al. Reference Maloof, Stewart, Weiss, Soule, Swanson-Hysell, Louzada, Garrick-Bethell and Poussart2010; Weiss et al. Reference Weiss, Pedersen, Garrick-Bethell, Stewart, Louzada, Maloof and Swanson-Hysell2010).

Figure 21. Comparisons with the Lonar impact crater, India. (a) Vesicular melt clasts of Tsenkher are found just outside of the south rim in a channel cutting into the ejecta. They occur within a several tens of metres exposure of a polymict breccia. (b) Vesicular melt clasts of Lonar are found just outside of the east rim in channels cutting into the ejecta. (c) Mixed, non-stratified facies of the Tsenkher ejecta at the terminal rampart. (d) Mixed, non-stratified facies of the Lonar ejecta near its terminus.

6.b. Processes of rampart formation

The ejecta layer on the eastern side of the Tsenkher structure displays a unique rampart morphology. This type of landform is not expected with impact craters or volcanic features with pure ballistic ejecta emplacement. Nevertheless, this ejecta layer morphology is common in impact craters on Mars, often expressed as a pronounced terminal rampart structure or sometimes as a more gradually thickening outwards trend, or as a combination of the two (e.g. Barlow et al. Reference Barlow, Boyce, Costard, Craddock, Garvin, Sakimoto, Kuzmin, Roddy and Soderblom2000; Mouginis-Mark & Baloga, Reference Mouginis-Mark and Baloga2006; Komatsu et al. Reference Komatsu, Ori, Marinangeli, Moersch and Chapman2007b). These features are collectively called layered ejecta structures. There are also some terrestrial impact structures with indications of such a morphology (i.e. terminal rampart or ejecta with a thickening outwards trend), notably the Lonar Crater (Maloof et al. Reference Maloof, Stewart, Weiss, Soule, Swanson-Hysell, Louzada, Garrick-Bethell and Poussart2010; Komatsu et al. Reference Komatsu, Kumar, Goto, Sekine, Giri and Matsui2014) and the Ries Crater (Sturm et al. Reference Sturm, Wulf, Jung and Kenkmann2012).

The Martian rampart craters are generally thought to be formed by impacts into volatile-rich targets or owing to atmospheric entrainment and deposition of ejected materials, which generates a ground-hugging fluidized ejecta flow (e.g. Mouginis-Mark, Reference Mouginis-Mark1981; Barlow et al. Reference Barlow, Boyce, Costard, Craddock, Garvin, Sakimoto, Kuzmin, Roddy and Soderblom2000; Mouginis-Mark & Baloga, Reference Mouginis-Mark and Baloga2006; Komatsu et al. Reference Komatsu, Ori, Marinangeli, Moersch and Chapman2007b; Weiss & Head, Reference Weiss and Head2014). The ground-hugging movement of such flows was likely facilitated by fluidization caused by the presence of volatiles (most likely water), although other processes such as dry granular flows may not be ruled out for both Mars (Wada & Barnouin-Jha, Reference Wada and Barnouin-Jha2006) or the relatively volatile-poor Moon or Mercury (Xiao & Komatsu, Reference Xiao and Komatsu2013). With increasing distance from the crater the friction from the expanding surface area covered by the flow overtakes its kinetic energy and the movement ceases. The trailing part of the flow catches up with the stopped head causing a stacking of material into a ridge resembling the defensive ‘rampart’ of ancient fortifications.

The debris-flow facies of the outer ridge (Fig. 11d, e) indicates that the ridge materials were emplaced after its ground-hugging motion. In both volcanic and impact explosions, the ground-hugging movement of ballistic ejecta and of crater rim materials that were structurally uplifted is envisaged. The inclusion of suevite-like breccia blocks in the chaotic deposit of the rampart gives an impression of a ‘breccia-in-breccia’-type deposit, possibly providing information on the timing of both the lithification of the suevite-like rock and its emplacement with respect to the ejection process responsible for the rampart ejecta layer.

6.c. Degradation of the Tsenkher structure

Regardless of its origin, the Tsenkher structure appears to have been degraded from the original morphology. General morphological similarities between impact craters and maar craters point to the importance of paying attention to degradational states of basic components including the inner basin, rim and ejecta for both structure types.

Degradation of impact craters is an important subject in planetary surface evolution, but it has received relatively little study (e.g. Grant et al. Reference Grant, Koeberl, Reimold and Schultz1997; Grant, Reference Grant1999; Kumar, Head & Kring, Reference Kumar, Head and Kring2010; Komatsu et al. Reference Komatsu, Kumar, Goto, Sekine, Giri and Matsui2014; Nakamura et al. Reference Nakamura, Yokoyama, Sekine, Goto, Komatsu, Senthil Kumar, Matsuzaki, Kaneoka and Matsui2014). The estimated age of Tsenkher (~ 5 Ma) is significantly older than other relatively small and pristine impact craters such as Meteor Crater (49.7±0.85 ka: Phillips et al. Reference Phillips, Zreda, Smith, Elmore, Kubik, Dorn and Roddy1991; 49.2±1.7 ka: Nishiizumi et al. Reference Nishiizumi, Kohl, Shoemaker, Arnold, Klein, Fink and Middleton1991) or Lonar Crater (< 12 ka: Maloof et al. Reference Maloof, Stewart, Weiss, Soule, Swanson-Hysell, Louzada, Garrick-Bethell and Poussart2010; 37.5±5.0 ka: Nakamura et al. Reference Nakamura, Yokoyama, Sekine, Goto, Komatsu, Senthil Kumar, Matsuzaki, Kaneoka and Matsui2014; 570±47 ka: Jourdan et al. Reference Jourdan, Moynier, Koeberl and Eroglu2011). These younger impact craters are characterized by limited sediment burial of the inner basins and possibly rim and ejecta reduction with respect to those of Tsenkher. For example, Tsenkher's inner basin is filled up to the level of the surrounding plains with sediments derived from the inner wall and also fluvial deposits entering through the northern breached rim segments. In addition, considerable amounts of lake and aeolian sediments are probably parts of the infill. In contrast, both Meteor Crater and Lonar Crater (Fig. 18b) have non-breached rims, and their inner basins’ surfaces are far below the surrounding plains (e.g. Kumar, Head & Kring, Reference Kumar, Head and Kring2010; Komatsu et al. Reference Komatsu, Kumar, Goto, Sekine, Giri and Matsui2014), indicating less intense degradation of the rims and that infilling has been much more limited. Thus, the degradational states of various components of Tsenkher in comparison to those of younger impact craters appear to be consistent with the 5 Ma age, reflecting a longer exposure time of Tsenkher to fluvial, lacustrine and aeolian processes.

7. Conclusions

The here-presented field observations from the 2007 expedition to the Tsenkher structure in the Gobi-Altai region of Mongolia as well as subsequent sample analysis favour an impact origin for the structure. The evidence for the impact origin includes: (1) the presence of a structurally uplifted near-circular rim surrounded by an ejecta blanket, (2) abundant breccias, some of which are melt- and millimetre-scale spherule-bearing, (3) shock metamorphic features in the form of PDFs, and (4) possible extraterrestrial components in the form of Fe-rich grains, and elevated PGE abundances and 3He/4He values in melt and breccia samples. A volcanic origin, in particular of maar formation, was proposed previously, but some conditions associated with Tsenkher, including its large size occurring in isolation, the structurally uplifted rim and the lack of bedded base surge deposits are not consistent with known maars. All these conditions make the Tsenkher structure a very unusual volcanic landform if of volcanic origin. 40Ar–39Ar dating of a vesicular melt sample gives the probable age of the Tsenkher structure as 4.9±0.9 Ma. The pronounced rampart structure associated with the well-preserved ejecta on its eastern side could provide important insights into the formation of similar structures found with numerous impact craters in the solar system with a particular significance for Mars.

Acknowledgements

We appreciate Dr Christian Koeberl for review comments. We thank Dr Erica Kido of the University of Graz for her assessment of the Palaeozoic fauna. Dr René De Hon of Texas State University provided valuable insights on maar volcanoes for the comparison with the Tsenkher structure. The field expedition was mainly financed by a grant provided through T.M., and partially by a grant to J.O. from the Spanish Ministry for Science and Innovation (Reference CGL2004-03215/BTE). Continued analytical work within the project was partially supported by funding from the Italian Space Agency to G.K., and by the grants AYA2011-24780/ESP and AYA2012-39362-C02-01 from the Spanish Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness to J.O.. We greatly appreciate administrative support for the fieldwork from Dr Bazaryn Bekhtur of the Research Centre of Astronomy and Geophysics, Mongolian Academy of Sciences and Mrs Noriko Yamauchi of the University of Tokyo. Mr Shinji Yamamoto contributed to the thin-section preparation. Dr Sanna Alwmark of Lund University helped us in the identification of the PDFs. Mr Ryuta Monji of the Tokyo Metropolitan University contributed to the determination of chemical compositions. PGA and INAA analyses were made possible by an inter-university cooperative programme for the use of JAEA facilities, supported by the University of Tokyo. 40Ar–39Ar dating was carried out under the support of the Radioisotope Centre, University of Tokyo.