1. Introduction

As the so-called ‘roof of world’, the geological evolution of the Qinghai–Tibet Plateau has gained significant attention from Earth scientists and other scholars. The South Qiangtang terrane is located in the central part of Tibet and is a key area for studying the evolution of Gondwana. This terrane is commonly considered a micro-continent that was located at the northern margin of Gondwana during early Palaeozoic time. Previous geological studies of the Qinghai–Tibet Plateau have advanced our understanding of the Palaeozoic evolution of the Palaeo-Tethys, although many key geological problems remain unresolved in the Qiangtang terrane (Zhai et al. Reference Zhai, Li, Cheng and Zhang2004; Lu et al. Reference Lu, Zhang, Huang, Tang, Li, Xu, Zhou, Lu and Li2006; Zhai, Li & Huang, Reference Zhai, Li and Huang2006, Reference Zhai, Li and Huang2007; Li et al. Reference Li, Zhai, Chen, Yu, Huang and Zhang2006, Reference Li, Dong, Zhai, Wang, Yan, Wu and He2008 a, Reference Li, Zhai, Dong, Liu, Xie and Wu2009; Wang et al. Reference Wang, Pan, Zhu, Zhu, Lin and Li2006, Reference Wang, Pan, Li, Dong, Zhu, Yuan and Zhu2008; Li, Reference Li2008; Dong & Li, Reference Dong and Li2009; Dong et al. Reference Dong, Zhang, Shi and Wang2009; Wu et al. Reference Wu, Li, Dong, Xie and Hu2009, Reference Wu, Li, Xie, Wang and Hu2010; Wu, Reference Wu2013; Fan et al. Reference Fan, Li, Wang, Xie and Xu2014a ). The existence and geological evolution of Precambrian basement rocks in the Qiangtang terrane continue to be debated (Li et al. Reference Li, Wang, Yang and He2000, Reference Li, Zhai, Cheng, Xu and Huang2005; Wang & Wang, Reference Wang and Wang2001; Li, Reference Li2003; Tan et al. Reference Tan, Chen, Wang, Fu, Wang and Du2008, Reference Tan, Wang, Fu, Chen and Du2009). Rocks in the central South Qiangtang terrane that were once interpreted as Neoarchaean–Proterozoic in age, including the Gemuri, Guoganjianianshan, Mayigangri and Amugang groups, have been identified as Carboniferous to Permian and Triassic strata in recent studies (Li et al. Reference Li, Wu, Wang and Yang2010). Investigations of the Precambrian and early Palaeozoic evolution of the South Qiangtang terrane are greatly limited by the rarity of exposed Precambrian and lower Palaeozoic rocks.

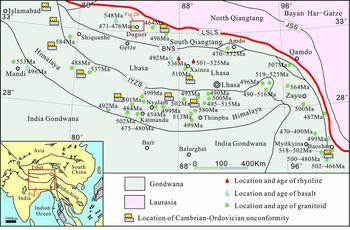

In recent years, unconformities between Cambrian and Ordovician strata and early Palaeozoic magmatic rocks have been identified along the northern Gondwana margin (Fig. 1) (Miller et al. Reference Miller, Thöni, Frank, Grasemann, Klötzli, Gruntli and Draganits2001; Gehrels et al. Reference Gehrels, Decelles, Martin, Ojha, Pinhassi and Upreti2003, Reference Gehrels, Kapp, Decelles, Pullen, Blakey, Weislogel, Ding, Guynn, Martin, McQuarrie and Yin2011; Zhu et al. Reference Zhu, Wang, Zou and Feng2003, Reference Zhu, Zhao, Niu, Dilek, Wang, Ji, Dong, Sui, Liu, Yuan and Mo2012 a; Zhou, Liu & Liang, Reference Zhou, Liu and Liang2004; Li et al. Reference Li, Wu, Wang and Yang2010; Huang et al. Reference Huang, Hao, Bai, Deng, Zhang and Huang2012; Cai et al. Reference Cai, Xu, Duan, Li, Cao and Huang2013; Yang et al. Reference Yang, Zhao, Yuan, Liu and Li2014; Hu et al. Reference Hu, Zhai, Jahn, Wang, Li, Lee and Tang2015 and references therein). It is therefore possible that the South Qiangtang terrane is underlain by an early Palaeozoic metamorphosed and crystalline basement, which raises the question of how the South Qiangtang terrane evolved geologically during early Palaeozoic time. Ordovician strata have been identified in the southern Mayigangri area based on occurrences of nautiloid and graptolite fossils that are reported in previous studies (Li et al. Reference Li, Cheng, Zhang and Zhai2004; Cheng, Chen & Zhang, Reference Cheng, Chen and Zhang2007). Pullen et al. (Reference Pullen, Kapp, Gehrels, Ding and Zhang2011) examined the detrital zircon geochronology of meta-sandstones in the Duguer area and suggested that they are older than the 476–471 Ma Duguer gneisses, based on field relationships. However, the provenance of meta-sandstones and the tectonic affinity of the South Qiangtang terrane are poorly constrained. The youngest reliable detrital zircon age of the Wenquan quartzite is 525 Ma, and Pan-African and Grenville–Jinning tectonothermal events are well documented in the source area (Dong et al. Reference Dong, Li, Wan, Wang, Wu, Xie and Liu2011). In addition, Yang et al. (Reference Yang, Zhao, Yuan, Liu and Li2014) identified an Ordovician parallel unconformity in the Wenquan area, suggesting that the South Qiangtang terrane represents a portion of the Gondwana supercontinent. Furthermore, it is likely that the South Qiangtang and North Qiangtang terranes were separated by an oceanic basin during Early Ordovician time, based on significant differences between Palaeozoic strata and the distinct geological evolutions of the two terranes. Yang et al. (Reference Yang, Zhao, Yuan, Liu and Li2014) proposed that the 476–471 Ma orthogneisses reported by Pullen et al. (Reference Pullen, Kapp, Gehrels, Ding and Zhang2011) are in fact two-mica granites that have undergone intense ductile deformation. Yang et al. (Reference Yang, Zhao, Yuan, Liu and Li2014) also suggested that the surrounding rocks belong to the upper Cambrian Rongma Formation. However, this theory is based solely on regional comparisons and lacks precise geochronological constraints.

Figure 1. Tectonic framework of the Tibetan Plateau showing the distribution of early Palaeozoic igneous rocks based on currently available data. JSS – Jinsha suture zone; LSLS – Longmu Co–Shuanghu–Lancangjiang suture zone; BNS – Bangong–Nujiang suture zone; IYZS – Indus–Yarlung Zangbo suture zone. Modified after Hu et al. (Reference Hu, Zhai, Jahn, Wang, Li, Lee and Tang2015).

Despite detrital zircon U–Pb dating of the meta-sandstones by previous workers, their age and sedimentary provenance remain uncertain. This study focuses on quartz schist in the Duguer area in the central part of the South Qiangtang terrane. Notably, Ordovician quartz schist was first identified in the Duguer area. However, key geological questions remain, including the sedimentary provenance of the quartz schist, the geological evolution of the sedimentary source region and the tectonic affinity of the South Qiangtang terrane. To help answer these questions, we present new laser ablation-inductively coupled plasma-mass spectrometer (LA-ICP-MS) zircon U–Pb ages, trace-element chemistry and Hf isotope compositions of detrital zircon grains from the quartz schist in the Duguer area. In addition, by combining our results with existing geological data from India Gondwana and the South Qiangtang, Lhasa and Himalaya terranes, we interpret the provenance and tectonic affinity of the Ordovician quartz schist, as well as the basement characteristics of the source area.

2. Geologic background and sample descriptions

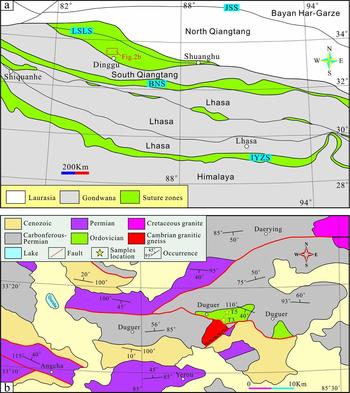

The Tibetan Plateau is located in the eastern part of the Himalaya–Alpine Orogen in southwestern China. The plateau comprises five extensive E–W-trending geological terranes (from north to south): the Bayan Har–Garze, North Qiangtang, South Qiangtang, Lhasa and Himalaya terranes, which are separated by the Jinsha, Longmu Co–Shuanghu–Lancangjiang, Bangong–Nujiang and Indus–Yarlung Zangbo suture zones, respectively (Fig. 2a) (Fan et al. Reference Fan, Li, Xie and Wang2014b ,Reference Fan, Li, Xu and Wang c , Reference Fan, Li, Xie and Liu2016). The Longmu Co–Shuanghu–Lancangjiang suture zone (LSLSZ) is generally considered the boundary between Gondwana and Laurasia, and the terranes to the north and south of the LSLSZ are interpreted to have originated from Laurasia and Gondwana, respectively (BGMR, 1993; Jin, Reference Jin2002; Li, Reference Li2008; Metcalfe, Reference Metcalfe, Buffetaut, Cuny, Loeuff and Suteethorn2009, Reference Metcalfe2013; Zhang, Yuan & Zhai, Reference Zhang, Yuan and Zhai2009). The South Qiangtang terrane is bounded by the LSLSZ and the Bangong–Nujiang suture zone (Fan et al. Reference Fan, Li, Xie and Wang2014b ,c, Reference Fan, Li, Xie and Liu2016). The Duguer area, located in the central part of the South Qiangtang terrane, is dominated by sedimentary strata of Ordovician, late Carboniferous to early Permian, Permian and Cenozoic ages (Fig. 2b). The Ordovician rocks are mainly quartz schist, whereas the upper Carboniferous to lower Permian strata are mainly meta-sandstone, sandy slate, phyllite, glacial marine diamictite and meta-basalt (Li & Zheng, Reference Li and Zheng1993; Jin, Reference Jin2002; Pan et al. Reference Pan, Ding, Yao and Wang2004; Li, Reference Li2008; Fan et al. Reference Fan, Li, Wang, Xie and Xu2014a ; Yang et al. Reference Yang, Zhao, Yuan, Liu and Li2014). The Permian strata comprise slate, bioclastic limestone, meta-sandstone and mafic volcanic rocks.

Figure 2. (a) Tectonic framework of the Tibetan Plateau (modified after Li, Reference Li2008). JSS – Jinsha suture zone; LSLS – Longmu Co–Shuanghu–Lancangjiang suture zone; BNS – Bangong–Nujiang suture zone; IYZS – Indus–Yarlung Zangbo suture zone. (b) Geological map of the Duguer areas in the South Qiangtang terrane, Tibet, showing the sample locations of quartz schist.

In this paper, we focus on Ordovician quartz schist from the Duguer area. The schist is intruded by Early Ordovician granite (now gneiss) (Fig. 3b) and overlain by metamorphosed upper Carboniferous to lower Permian rocks along an angular unconformity (Fig. 2b) (Pullen et al. Reference Pullen, Kapp, Gehrels, Ding and Zhang2011; Yang et al. Reference Yang, Zhao, Yuan, Liu and Li2014). The quartz schist records ductile deformation in the form of stretched folds and rootless folds.

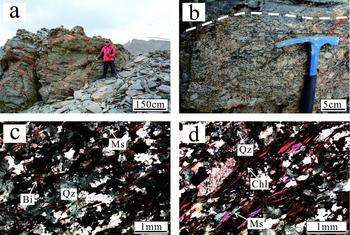

Figure 3. Photographs and photomicrographs of Duguer quartz schist from the South Qiangtang terrane, Tibet. Qz – quartz; Ms – muscovite; Bi – biotite; Chl – chlorite.

We collected two samples for LA-ICP-MS zircon U–Pb dating and Hf isotope analysis (sample locations are shown in Fig. 2b). The quartz schist experienced dynamic metamorphism and is schistose (Fig. 3a) and mylonitic. The principal minerals are biotite (10 vol.%), muscovite (< 5 vol.%), chlorite (10 vol.%) and quartz (75 vol.%) (Fig. 3c, d). Crystalline quartz exhibits evidence of dynamic recrystallization and has a shape-preferred orientation that defines the schistosity and a lineation, together with oriented mica.

3. Analytical methods

3.a. LA-ICP-MS zircon U–Pb analysis

Two samples from the quartz schist were selected for zircon U–Pb analyses. The zircons were separated by conventional flotation, heavy liquid and magnetic techniques at the Special Laboratory of the Geological Team of Hebei Province, Langfang, China. In order to select analytical points for LA-ICP-MS analyses, the internal structures and types of zircon were characterized under reflected light, transmitted light and cathodoluminescence (CL) at the Institute of Physics, Peking University, Beijing, China. The analyses of the U, Th and Pb isotopes and trace elements of the zircons were carried out by LA-ICP-MS at the Geological Laboratory Centre, China University of Geosciences, Beijing, China. The spot size was 36 μm and denudation time was 50 s; the carrier gas was helium and the flow was 0.8 L min−1. Reference and internal zircon standards 91500 (Wiedenbeck et al. Reference Wiedenbeck, Allé, Corfu, Griffin, Meier, Oberli, Quadt, Roddick and Spiegel1995) and NIST610 (29Si) were used for instrument calibration, respectively. The Pb correction method of Andersen (Reference Andersen2002) was applied. For further details of the analytical techniques, see Yuan et al. (Reference Yuan, Gao, Liu, Li, Günther and Wu2004). Reported uncertainties for the age analyses were given at the 2σ value with weighted mean ages at the 95% confidence level. Isotopic data were processed using the GLITTER (version 4.4) and Isoplot/Ex (version 4.15) programs (Ludwig, Reference Ludwig2003).

3.b. In situ Hf isotope ratio analysis of zircon by LA-MC-ICP-MS

In situ zircon Hf isotope experiments were conducted using a Neptune Plus multi-collector ICP-MS (MC-ICP-MS) (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Germany) in combination with a Geolas 2005 excimer ArF laser ablation system (Lambda Physik, Göttingen, Germany) that was hosted at the state Key Laboratory of Geological Processes and Mineral Resources, China University of Geosciences in Wuhan. The same analytical points as those used for the LA-ICP-MS analyses were used, which were selected from CL images. All data were acquired in single spot ablation mode at a spot size of 44 μm. The energy density of the laser ablation that was used in this study was 5.3 J cm–2. Helium was used as the carrier gas within the ablation cell and was merged with argon (makeup gas) after the ablation cell. Each measurement consisted of 20 s of acquisition of the background signal and ablation signal acquisition time was 50 s. Details on the operating conditions and analytical methods are the same as described by Hu et al. (Reference Hu, Liu, Gao, Liu, Yang, Zhang, Tong, Lin, Zong, Li, Chen and Zhou2012). The 176Hf/177Hf ratio of the zircon (91500) standard analysed was 0.282299±31 (2σn, n = 40), which was similar to the 176Hf/177Hf ratios of 0.282302±8 and 0.282306±8 (2σ) determined by the solution method (Woodhead et al. Reference Woodhead, Hergt, Shelley, Eggins and Kemp2004). Off-line selection and integration of analyte signals and mass bias calibrations were performed using the ICPMSDataCal program (Liu et al. Reference Liu, Gao, Hu, Gao, Zong and Wang2010).

4. Analytical results

4.a. Zircon descriptions and U–Pb dating results

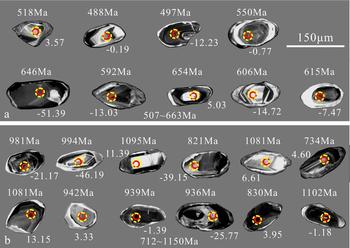

Zircon crystals from the quartz schist are mostly transparent and colourless, with diameters of 50–150 μm, and are divided into three groups based on morphology: spherical, ellipsoid and elongate prismatic. Most zircon grains have a detrital core with oscillatory and banded zoning that is surrounded by a thin, unzoned metamorphic rim (10–30 μm) (Fig. 4). In most zircon crystals, the internal structure is truncated at the boundary with the metamorphic rim.

Figure 4. Cathodoluminescence (CL) images of representative zircon grains, ages and εHf(t) of Duguer quartz schist from the South Qiangtang terrane, Tibet. Solid and dashed circles show the locations of U–Pb dating and Hf analyses, respectively.

A total of 162 spot analyses on detrital zircon cores yielded highly variable U–Pb ages of 2721–488 Ma (Fig. 5a; online Supplementary Material Table S1 available at http://journals.cambridge.org/geo). We report 206Pb–238U ages for U–Pb ages that are younger than 1000 Ma and 207Pb–206Pb ages for U–Pb ages that are older than 1000 Ma. The zircon ages are divided into five clusters according to the dominant age peaks, which occur at 507–663 Ma, 712–840 Ma, 892–1006 Ma, 1062–1150 Ma and 2429–2548 Ma. The two most dominant age peaks are at 605 Ma and 963 Ma (Fig. 6). The analyses yielded a wide range of U (26.76–2012.46 ppm) and Th (11.32–1349.00 ppm) concentrations (online Supplementary Material Fig. S1a available at http://journals.cambridge.org/geo), and variable but relatively high Th/U ratios of 0.01–2.96 (average 0.54), with most of the Th/U ratios being greater than 0.1 (online Supplementary Material Fig. S1b available at http://journals.cambridge.org/geo).

Figure 5. (a) Concordia plot of Duguer quartz schist from the South Qiangtang terrane, Tibet. (b) Plot of εHf(t) v. U–Pb ages for Duguer quartz schist from the South Qiangtang terrane, Tibet.

Figure 6. Age distribution of detrital zircons from the Duguer quartz schist and upper Neoproterozoic–Palaeozoic strata in the South Qiangtang, Lhasa and Himalaya terranes and India. Modified from Zhu et al. (Reference Zhu, Zhao, Niu, Dilek, Wang, Ji, Dong, Sui, Liu, Yuan and Mo2012 b). Data for the South Qiangtang, Lhasa and Himalaya terranes (Zhu et al. Reference Zhu, Zhao, Niu, Dilek, Wang, Ji, Dong, Sui, Liu, Yuan and Mo2012 b), and India (Turner et al. Reference Turner, Meet, Pandit and Kamenov2014; Bickford et al. Reference Bickford, Basu, Patranabis-Deb, Dhang and Schieber2011; Malone et al. Reference Malone, Meert, Banerjee, Pandit, Tamrat, Kamenov, Pradhan and Sohl2008; Collins et al. Reference Collins, Santosh, Braun and Clark2007) are shown for comparison.

4.b. Zircon Hf isotopic and rare earth element data

The zircon Hf isotopic data from the two samples are presented in online Supplementary Table S2 (available at http://journals.cambridge.org/geo) and plotted in Figure 5b. Thirty-five analyses were performed on zircon grains from the 507–663 Ma age cluster, which overlaps temporally with the Pan-African event. The εHf (t) values range from −26.50 to 8.03 (Fig. 5b), and the TDM and TDM C model ages range from 904 to 2208 Ma and from 1013 to 2879 Ma, respectively, except for six analyses that yielded lower εHf (t) values (−52.54 to −31.20) and older TDM (2285–3236 Ma) and TDM C (3041–4242 Ma) ages. Thirteen analyses of zircon grains with U–Pb ages of 712–840 Ma, which are coeval with the Jinning event, yielded εHf (t) values of −16.96 to 4.60 (Fig. 5b), TDM model ages of 1130–1951 Ma and TDM C model ages of 1277–2451 Ma, apart from two analyses with lower εHf (t) values (−39.15 and −33.53) and older TDM (2875 Ma and 2669 Ma) and TDM C (3721 Ma and 3424 Ma) ages. Twenty analyses on zircon crystals with Grenvillian ages (892–1150 Ma) yielded εHf (t) values of −25.77 to 13.15 (Fig. 5b), TDM model ages of 1082–2472 Ma and TDM C model ages of 1083–3091 Ma, except for one analysis with a lower εHf (t) value (−46.19) and older TDM (3295 Ma) and TDM C (4226 Ma) ages. Two analyses on zircon crystals that are older than 1200 Ma yielded lower εHf (t) values (–6.53 and –6.09) and older TDM (2215 Ma and 2308 Ma) and TDM C (2500 Ma and 2585 Ma) ages.

Although the 162 zircon analyses yielded a range of ages, the zircon crystals have similar rare earth element (REE) patterns that exhibit strong heavy REE (HREE)-enrichment, light REE (LREE)-depletion and positive Ce and negative Eu anomalies that become less pronounced with increasing total REE content (online Supplementary Material Fig. S2 and Table S3 available at http://journals.cambridge.org/geo). Most zircon grains have trace-element compositions that are similar to those of magmatic zircons from granitoid rocks (Rubatto, Reference Rubatto2002; Wu et al. Reference Wu and Zheng2004).

5. Discussion

5.a. Depositional age of the quartz schist

The lower Palaeozoic sedimentary rocks of the Tibetan Plateau occur mainly in the Himalaya terrane. Previous studies report numerous unconformities between the Cambrian and Ordovician strata in this terrane, whereas unconformities are rarely reported in the Lhasa and South Qiangtang terranes (Fig. 1). The unconformity between Cambrian and Ordovician strata has so far been documented only in the Gangdisi region of the Lhasa terrane and the Rongma region of the South Qiangtang terrane (Fig. 1). The depositional age of the epimetamorphic clastic rocks that are widely distributed throughout the South Qiangtang terrane remains controversial owing to the absence of reliable fossil evidence. In previous studies, the clastic rocks were interpreted as the upper Carboniferous to lower Permian Zhanjin Formation, which is considered to represent late Palaeozoic passive continental margin deposits of the Palaeo-Tethys Ocean. This interpretation greatly limits our understanding of the early Palaeozoic evolution of the South Qiangtang terrane. Yang et al. (Reference Yang, Zhao, Yuan, Liu and Li2014) investigated the Cambrian and Ordovician strata in the Rongma region and suggested that the Duguer quartz schist was deposited during Cambrian time, based on regional stratigraphic correlations, although no reliable zircon U–Pb ages were determined. Thus, we present a thorough investigation of the depositional age of the Duguer quartz schist. The 162 detrital zircon U–Pb ages presented here indicate that the schist was deposited after 488 Ma (Figs 4a, 5a). Furthermore, Pullen et al. (Reference Pullen, Kapp, Gehrels, Ding and Zhang2011) reported that orthogneiss in the Duguer area yields zircon U–Pb ages of 471 to 476 Ma (Fig. 1). The orthogneiss is granite that has undergone intense ductile deformation, and the granite is hosted by the Duguer quartz schist. Therefore, the depositional age of the Duguer quartz schist is constrained to between 488 Ma and 476 Ma, during Early Ordovician time, as opposed to Cambrian time.

5.b. Provenance of the Duguer quartz schist

The Duguer quartz schist is located in the central South Qiangtang terrane. As described above, the Palaeo-Tethys Ocean existed between the South Qiangtang and North Qiangtang terranes in Early Ordovician time, and it is therefore likely that the sediments of the Duguer quartz schist were derived from terranes located south of the LSLSZ (i.e. the South Qiangtang, Lhasa and Himalaya terranes, and India Gondwana). Zircon is highly stable in sedimentary rocks and the age peaks of detrital zircon grains represent the timing of magmatic events in the sediment source region. Our detrital zircon LA-ICP-MS U–Pb ages from the Duguer quartz schist show that the source area was influenced by multiple tectonothermal events, corroborating the results of previous studies in neighbouring areas (Pullen et al. Reference Pullen, Kapp, Gehrels, Ding and Zhang2011; Dong et al. Reference Dong, Li, Wan, Wang, Wu, Xie and Liu2011; Yang et al. Reference Yang, Zhao, Yuan, Liu and Li2014). The detrital zircon grains have a wide range in U–Pb ages, with age clusters at 507–663 Ma, 712–840 Ma, 892–1006 Ma, 1062–1150 Ma and 2429–2548 Ma, similar to the South Qiangtang and Himalaya terranes, but not the Lhasa terrane (peak at 1157 Ma) or India Gondwana (peaks at 1170 Ma and 1793 Ma) (Fig. 6).

Cathodoluminescence images show that most of the zircon grains that were dated in this study exhibit oscillatory and banded zoning patterns (Fig. 4). The zircon crystals have relatively high Th/U ratios of 0.01–2.96 (average 0.54), and most of the Th/U ratios are greater than 0.1 (online Supplementary Material Fig. S1a, b available at http://journals.cambridge.org/geo). Most zircon grains have similar REE patterns that are strongly enriched in HREEs and depleted in LREEs, with positive Ce and negative Eu anomalies (online Supplementary Material Fig. S2 and Table S3 available at http://journals.cambridge.org/geo). The zircon morphology and trace-element chemistry suggest that the detritus was sourced from magmatic rocks (Rubatto Reference Rubatto2002; Zhang et al. Reference Zhang, Schertl, Wang, Shen and Liou2009). Most of the zircon grains are sub-rounded to rounded, and only a few occur as elongate, prismatic, euhedral–subhedral crystals. Older zircon grains exhibit a higher degree of rounding than younger crystals, which suggests that the older zircon grains were transported greater distances or were subjected to sedimentary recycling, and that the younger zircon crystals originated from a more proximal source. Based on their morphology (Fig. 4), U–Pb age distribution (Fig. 6), trace-element compositions and Hf model ages (Fig. 7a, b), we propose that the 488–1150 Ma detrital zircon grains are from a magmatic protolith of the quartz schist, and that metamorphism occurred during the Pan-African and Grenville–Jinning events in the source area. Zircon ages that are older than 1200 Ma may represent captured zircons or the ages of recycled sediments. The Hf isotope compositions of the detrital zircon grains indicate that crustal recycling played an important role in the formation of the protolith in the sedimentary source region, and that mantle-derived magmatism was dominant during the Pan-African and Grenville–Jinning events (Fig. 5b).

Figure 7. (a) Detrital zircon crystallization age v. TDM C model age indicating older terranes as the source regions of the Duguer quartz schist detrital zircons. (b) Frequency-age plots of detrital zircon TDM C model ages for the Duguer quartz schist.

The U–Pb age peak at 507–663 Ma is widely recognized in the South Qiangtang, Lhasa and Himalaya terranes, and in India Gondwana (Fig. 6), but has no clear significance for the provenance of the quartz schist. Considering the detrital zircon morphology and the widely distributed early Palaeozoic magmatic rocks along the northern margin of Gondwana, we propose that the zircons were derived from the South Qiangtang and Himalaya terranes, and perhaps even from India Gondwana. In addition, we suggest that the 507–663 Ma cluster in detrital zircon U–Pb ages represents magmatic activity in the source area during plate collision and subduction related to the Pan-African tectonic event, or, alternatively, magmatic activity related to extension after the Pan-African event (Liu et al. Reference Liu, Li, Xie, Fan, Wu, Jiang and Li2016). The εHf (t) values of the age cluster range from –26.50 to 8.03, but are mostly negative (Fig. 5b), and the TDM C model ages vary from 1013 to 2879 Ma, apart from six analyses that yield lower εHf (t) values (−52.54 to −31.20) and older TDM C ages (3041–4242 Ma). Therefore, the magmatic rocks of the Pan-African event in the source area are mainly the products of Mesoproterozoic and Palaeoproterozoic recycling of continental crust (Fig. 7a), along with minor mantle-derived magmatism.

Notably, the peak detrital zircon ages of 712–840 Ma and 892–1006 Ma closely correspond to the ages of detrital zircons in the South Qiangtang and Himalaya terranes, and in India Gondwana, but these zircon ages are absent in the Lhasa terrane. Neoproterozoic rocks are rare on the Tibetan Plateau. The Precambrian basement of the Himalaya terrane comprises the Lhagoi Kangri Group, which is Mesoproterozoic to Neoproterozoic in age (Pan et al. Reference Pan, Ding, Yao and Wang2004; Liao et al. Reference Liao, Li, Lu, Yuan and Chu2008). Hu et al. (Reference Hu, Wu, Jiang, Shi, Ye and Liu2005) suggested that the protoliths of the Nyainqêntanglha Group were deposited between 787 and 748 Ma, based on the age of a mylonitized trondhjemite (c. 787 Ma) that is intruded by a mylonitized granite (c. 748 Ma). Guynn et al. (Reference Guynn, Kapp, Pullen, Gehrels, Heizler and Ding2006, Reference Guynn, Kapp, Gehrels and Ding2012) reported 915–840 Ma orthogneisses in the Amdo region. However, the detrital zircon U–Pb age populations of 712–840 Ma and 892–1006 Ma in the Duguer quartz schist require the occurrence of extensive outcrops of Neoproterozoic magmatic rocks in the source region. Existing geochronological data indicate that Neoproterozoic magmatic rocks are widely distributed in India Gondwana (Zhu et al. Reference Zhu, Zhao, Niu, Dilek, Hou and Mo2013; Fan et al. Reference Fan, Li, Xie and Liu2016 and references therein). Therefore, we infer that the most likely provenance of Neoproterozoic zircons from the Duguer quartz schist is India Gondwana, followed by the Amdo and Himalaya terranes. The 712–840 Ma zircon U–Pb age cluster is linked to magmatic activity of the Jinning event. The 1062–1150 Ma and 892–1006 Ma age clusters are related to Grenvillian events that formed the Rodinia supercontinent, as well as the subsequent break-up of Rodinia. The εHf (t) values of the three clusters range from –46.19 to 13.15 (Fig. 5b), and TDM C model ages vary from 1083 to 4226 Ma (Fig. 7a). These results suggest that the magmatic rocks of the Grenville–Jinning event in the source area were derived mainly from mantle and continental crust of Mesoproterozoic and Palaeoproterozoic age. Finally, the 2429–2548 Ma age cluster is interpreted to reflect the age of the oldest crystalline basement, possibly related to the dispersion of a global supercontinent at the end of Archaean time. Thus, the 2429–2548 Ma detrital zircons suggest sedimentary recycling of Archaean basement material.

The present results support the possibility of the presence of Pan-African and Grenville–Jinning basement in the source area of the Duguer quartz schist. Our results also suggest that rocks of the source area were mainly the products of Mesoproterozoic and Palaeoproterozoic (Fig. 7b) recycling of continental crust and that mantle-derived magmatism played an important role. The provenance of the Duguer quartz schist was most likely India Gondwana, followed by the South Qiangtang, Amdo and Himalaya terranes.

5.c. Tectonic affinity

The age distributions of detrital zircons in the present study have also been reported from detrital zircons in metamorphosed sediments from the northern margin of Gondwana (Kapp et al. Reference Kapp, Yin, Manning, Harrison and Taylor2003; Gehrels et al. Reference Gehrels, Decelles, Ojha and Upreti2006; Pullen et al. Reference Pullen, Kapp, Gehrels, Vervoort and Ding2008, Reference Pullen, Kapp, Gehrels, Ding and Zhang2011; Dong et al. Reference Dong, Li, Wan, Wang, Wu, Xie and Liu2011; Yang et al. Reference Yang, Zhao, Yuan, Liu and Li2014). These results suggest that an extensive source region provided abundant detritus to the sedimentary cover strata. Recent research indicates that India Gondwana and the Himalaya, Lhasa and South Qiangtang terranes share a tectonic affinity with Pan-African basement (Miller et al. Reference Miller, Thöni, Frank, Grasemann, Klötzli, Gruntli and Draganits2001; Cenki, Braun & Brocher, Reference Cenki, Braun and Brocher2004; Xu et al. Reference Xu, Yang, Liang, Qi, Liu, Zeng, Liu, Li, Wu, Shi and Chen2005; Gehrels et al. Reference Gehrels, Decelles, Ojha and Upreti2006; Collins et al. Reference Collins, Santosh, Braun and Clark2007; Reference Li, Xie, Sha and DongLi et al. 2008b ). Tectonothermal events that post-date the Pan-African period are well recorded in the early Palaeozoic basement of Gondwana, whereas they have not been identified in the basement of the southern margin of Laurasia (Zhu et al. Reference Zhu, Zhao, Niu, Dilek, Wang, Ji, Dong, Sui, Liu, Yuan and Mo2012 a; Hu et al. Reference Hu, Zhai, Jahn, Wang, Li, Lee and Tang2015 and references therein). The many detrital zircon U–Pb ages of the Duguer quartz schist record the Pan-African event, indicating that the sediment in the schist was derived mainly from the Precambrian basement of Gondwana. The age distributions of detrital zircon grains from the Duguer quartz schist are similar to those of detrital zircon grains from contemporaneous sedimentary rocks in the South Qiangtang, Lhasa and Himalaya terranes, and India Gondwana (Fig. 6). Therefore, the South Qiangtang, Lhasa and Himalaya terranes all likely belong to the northern margin of Gondwana (Fig. 8a). Notably, the detrital zircon U–Pb age peak at 605 Ma in the Duguer quartz schist is older than the recorded zircon U–Pb age peaks in India Gondwana and the South Qiangtang, Lhasa and Himalaya terranes (Fig. 6), suggesting that early Pan-African activity was more pervasive in the source area of the Duguer quartz schist.

Figure 8. (a) Reconstruction of Gondwana showing the locations of major terranes in Early Ordovician time (modified from Zhu et al. Reference Zhu, Zhao, Niu, Dilek and Mo2011, Reference Zhu, Zhao, Niu, Wang, Yildirim, Dong and Mo2012 b; Hu et al. Reference Hu, Zhai, Jahn, Wang, Li, Lee and Tang2015 and references therein). (b) Schematic diagrams illustrating the provenance of the Duguer quartz schist in Early Ordovician time.

A marked sedimentary discontinuity between Cambrian and Ordovician strata is developed in the Himalaya, Lhasa and South Qiangtang terranes (Fig. 1), and generally occurs as a paraconformity rather than an angular unconformity (Miller et al. Reference Miller, Thöni, Frank, Grasemann, Klötzli, Gruntli and Draganits2001; Gehrels et al. Reference Gehrels, Decelles, Martin, Ojha, Pinhassi and Upreti2003, Reference Gehrels, Kapp, Decelles, Pullen, Blakey, Weislogel, Ding, Guynn, Martin, McQuarrie and Yin2011; Zhu et al. Reference Zhu, Wang, Zou and Feng2003; Zhou, Liu & Liang, Reference Zhou, Liu and Liang2004; Li et al. Reference Li, Wu, Wang and Yang2010; Huang et al. Reference Huang, Hao, Bai, Deng, Zhang and Huang2012; Cai et al. Reference Cai, Xu, Duan, Li, Cao and Huang2013; Yang et al. Reference Yang, Zhao, Yuan, Liu and Li2014). All three terranes record magmatic activity at c. 550–460 Ma (Fig. 1), which is younger than the established age of the Pan-African tectonothermal event (570–520 Ma) (Xu et al. Reference Xu, Yang, Liang, Qi, Liu, Zeng, Liu, Li, Wu, Shi and Chen2005). This indicates that the South Qiangtang, Lhasa and Himalaya terranes have a shared tectonic affinity because all three terranes experienced the late Pan-African event at c. 500 Ma and were affected by extension after the formation of the Gondwana supercontinent. The Pan-African orogenic event records continental collision between eastern and western Gondwana, which caused extension at the northern margin of the supercontinent (Fig. 8). The detachment of lithospheric mantle was followed by upwelling of mantle-derived material that may have caused partial melting of the lithosphere and related magmatism (Fig. 8), which is widespread throughout the South Qiangtang, Lhasa and Himalaya terranes (Fig. 1). The unconformity between the Cambrian and Ordovician strata and the Duguer quartz schist is probably a result of the depositional response to an extensional rift basin that formed during the break-up of Gondwana (Liu et al. Reference Liu, Li, Xie, Fan, Wu, Jiang and Li2016).

Most current models suggest that the South Qiangtang, Lhasa and Himalaya terranes were located to the north of India Gondwana (Yin & Harrison, Reference Yin and Harrison2000; Metcalfe, Reference Metcalfe, Buffetaut, Cuny, Loeuff and Suteethorn2009). However, our new detrital zircon U–Pb ages, Hf isotope data and provenance interpretations indicate that detrital zircon grains from the Duguer quartz schist were most likely sourced from India Gondwana, followed by the South Qiangtang, Amdo and Himalaya terranes. This interpretation does not support the Lhasa terrane as being the main source of sediment for the Duguer quartz schist. Based on U–Pb ages and Hf isotope data from detrital zircons from Palaeozoic metasedimentary rocks, Zhu et al. (Reference Zhu, Zhao, Niu, Dilek and Mo2011) suggested that the Lhasa terrane originated from Australia rather than being part of a Palaeozoic continental margin system in India Gondwana. Our new data and interpretations support the theory that the Lhasa terrane might originate from Australia. In recent years, Grenville–Jinning tectonomagmatic events (1300–736 Ma) have been identified in the Himalaya terrane (Xu et al. Reference Xu, Yang, Liang, Qi, Liu, Zeng, Liu, Li, Wu, Shi and Chen2005; Gehrels et al. Reference Gehrels, Decelles, Martin, Ojha, Pinhassi and Upreti2003, Reference Gehrels, Decelles, Ojha and Upreti2006). Conversely, in the Lhasa terrane, ages of 787–748 Ma are limited to metamorphosed intrusive rocks in the Nyainqêntanglha Group (Hu et al. Reference Hu, Wu, Jiang, Shi, Ye and Liu2005). The detrital zircon U–Pb age peak of c. 963 Ma is older than the c. 800 Ma age peak in the Duguer quartz schist (Fig. 6), indicating that both the Grenville and Jinning tectonomagmatic events occurred in the source region, with the Grenville tectonomagmatic event being more significant. The abundance of 800–1100 Ma detrital zircon grains also suggests that the Duguer quartz schist was derived from the Himalaya terrane and India Gondwana (Fig. 8b). Consequently, the South Qiangtang terrane was part of the northern Gondwana margin (Fig. 6). A northward-flowing river system that originated in the Himalaya terrane and India Gondwana likely supplied sediments to the South Qiangtang terrane (Fig. 8b). Such long-distance transport of sediments from the source region would explain the presence of rounded detrital zircons in the Duguer quartz schist.

6. Conclusions

-

(1) The protolith of the Duguer quartz schist was deposited during Early Ordovician time. It has been considered similar to the Zhanjin Formation, indicating that part of the Zhanjin Formation may be Early Ordovician in age.

-

(2) The age spectra of detrital zircons from the Duguer quartz schist suggest that significant Pan-African and Grenville–Jinning tectonothermal events occurred in the sedimentary source region.

-

(3) The Hf isotope compositions of detrital zircons indicate multiple episodes of crustal recycling in the source region, and that mantle-derived magmatism was significant during the Pan-African and Grenville–Jinning tectonothermal events.

-

(4) The U–Pb ages, Hf isotopic compositions and trace-element chemistry of detrital zircon grains in the Duguer quartz schist suggest that the South Qiangtang, Lhasa and Himalaya terranes share a tectonic affinity with the northern margin of Gondwana.

Acknowledgements

We thank Li Su from the Geological Laboratory Centre of the China University of Geosciences, Beijing, for help with zircon U–Pb and whole-rock geochemical analyses. The helpful and constructive reviews and suggestions by Professor W. J. Xiao and the editor are greatly appreciated. This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 41072166, 41272240, 41273047) and China Geological Survey project (Grant No. 1212011221093, 1212011121248, 12120113036700).

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0016756816000212.