1. Introduction

This work focuses on the Cenomanian and lowermost Turonian marine series of a lesser-known area of Algeria through field and laboratory work that resulted in an integrated biostratigraphic approach with ammonites and foraminifera, allowing correlations with classical areas important for the study of this interval, including those of Tunisia, well-known since the 1990s. The contribution may help to solve the complex puzzle that is the Cenomanian–Turonian of the Tethyan carbonate platforms and related basin areas of North Africa, and its biostratigraphic comparison with Southern and NW Europe, and other better-known areas.

The studied area of the current Aures massif is located in a Tethyan basin opened to the Tethys to the NE, and E but more or less closed to SW and S. Within this depositional setting, a thick marly sedimentation was developed in the centre and low carbonate content facies in the SW end (Laffitte, Reference Laffitte1939). This subsiding basin (R Guiraud, unpub. thesis, Univ. Nice, 1973) is characterized by a poorly oxygenated (even anoxic) environment, favourable to the preservation of organic matter. The Cenomanian series outcrop in several large anticlines, where they are characterized by a thick marly succession not reviewed since the work of Laffitte (Reference Laffitte1939), and not yet studied in detail. This setting poses several lithologic, stratigraphic (sub-stage boundaries), sedimentological (lack of a detailed diagenetic study and depositional environments characterization) and geodynamic (tectonic structures and their effect on the poorly known palaeogeographic evolution) problems.

The main objective of this study is to present the first attempt at a detailed biostratigraphic analysis of this area in order to establish a relative chronology based on ammonite and foraminiferan data with determination of the Cenomanian sub-stage boundaries in the Aures, more precisely in the Nouader site. The results will then be compared with others already known from neighbouring regions of the Tethyan Realm (Central Tunisia, Algerian–Tunisian borders) and the Boreal domain (NW Europe).

This work is based on materials collected by A. Bensekhria in the framework of a PhD research project, and focuses especially on various aspects of the Aures Basin, such as the local stratigraphy, sedimentology and macro- and microfaunal assemblages, with emphasis on the location of the Cenomanian sub-stage boundaries, the transition to the Turonian, and the palaeoenvironmental evolution.

2. Geographical and geological background

The Cenomanian marine deposits of Algeria are well exposed in the basins of the Atlas Domain, located in the foreland of the Alpine belt, including the Saharan Atlas and the Preatlasic zone. The Oulad Nail, Ziban and Aures–Nemencha regions range from the eastern part of the Saharan Atlas, extending to the NE towards the Mellegue Mountains and further eastwards into the Tunisian Atlas. The Auresian realm represents the eastern part of the Atlas Basin, which extends into Tunisia as the Tunisian Atlas (H Ghandriche, unpub. thesis, Univ. Paris XI, 1986; Herkat & Guiraud, Reference Herkat and Guiraud2006) (Fig. 1a, b).

Fig. 1. (a) Palaeogeographic domains of the Oriental Atlas range (Herkat & Guiraud, Reference Herkat and Guiraud2006) and location of the study area. (b) Topographic map of Ain Beida at a scale 1:250,000 and location of the cross-section (black line AB).

The regional palaeogeography of the Aures Basin consists of three main domains characterized by a progressive deepening from SW to NE. The proximal to intermediate ramp corresponds to a depositional environment with a predominance of alternating marls and limestones generally containing benthic biota. The distal ramp and transition to the basin are characterized by open marine deposits (D Bureau, unpub. thesis, Univ. Pierre & Marie Curie, 1986). These latter consist predominantly of marls with benthic and planktonic foraminifera, with some locally developed organic-rich pelagic limestones marking the transgressive intervals.

The Aures Basin is characterized by a system of tilted blocks bounded by NW–SE to WNW–ESE trending faults. Otherwise, NE–SW faults located within the basin are characterized by transtensional movements (Laffitte, Reference Laffitte1939; R Guiraud, unpub. thesis, Univ. Nice, 1973; JM Vila, unpub. thesis, Univ. Pierre & Marie Curie, 1980; N Kazi Tani, unpub. thesis, Univ. Pau, 1986). The studied deposits are only of sedimentary nature, and Early late Cretaceous in age. They are generally very thick, which can be explained by the significant transgression and the relative subsidence that affected the region during the Cenomanian (for details on regional geology see, e.g., Laffitte, Reference Laffitte1939; Bertraneu, Reference Bertraneu1955; Emberger, Reference Emberger1960; R Guiraud, unpub. thesis, Univ. Nice, 1973; Guiraud, Reference Guiraud1974, Reference Guiraud1975; JM Vila, unpub. thesis, Univ. Pierre & Marie Curie, 1980; D Aissaoui, unpub. thesis, Univ. Strasbourg, 1985; D Bureau, unpub. thesis, Univ. Pierre & Marie Curie, 1986; N Kazi Tani, unpub. thesis, Univ. Pau, 1986; H Ghandriche, unpub. thesis, Univ. Paris XI, 1991; B Addoum, unpub. thesis, Univ. Paris Sud, 1995; M Herkat, unpub. thesis, Univ. d’Alger USTHB, 1999).

This study is based on the Nouader region, which is located in the NE of Algeria, to the SE of Batna province, near the town of Thniet el Abed. It is bounded to the N by Ras Gueddlane, to the NW by Bouzina, to the NE by Mahmel Mountain, to the S by El Krouma Mountain, to the SW by Chir and to the SE by Thniet El Abed district (Fig. 1b). The geological section is oriented NNW–SSE and extends over a thickness of c. 700 m. (Geographical coordinates of the starting and end points are GPS = A: 35°13′ 49″ N, 006°08′ 42″ E, and B: 35°14′ 22″ N, 006°08′ 38″ E.)

The trace of this section was chosen according to several criteria such as the quality of outcrops, the facility access and tectonic absence, but also the presence of lithological and palaeontological landmarks which allowed us to establish regional correlations. It was completed in the northern flank of the Azreg mountain anticline, from the Oued Abdi valley to the local Turonian limestone bars (Fig. 2).

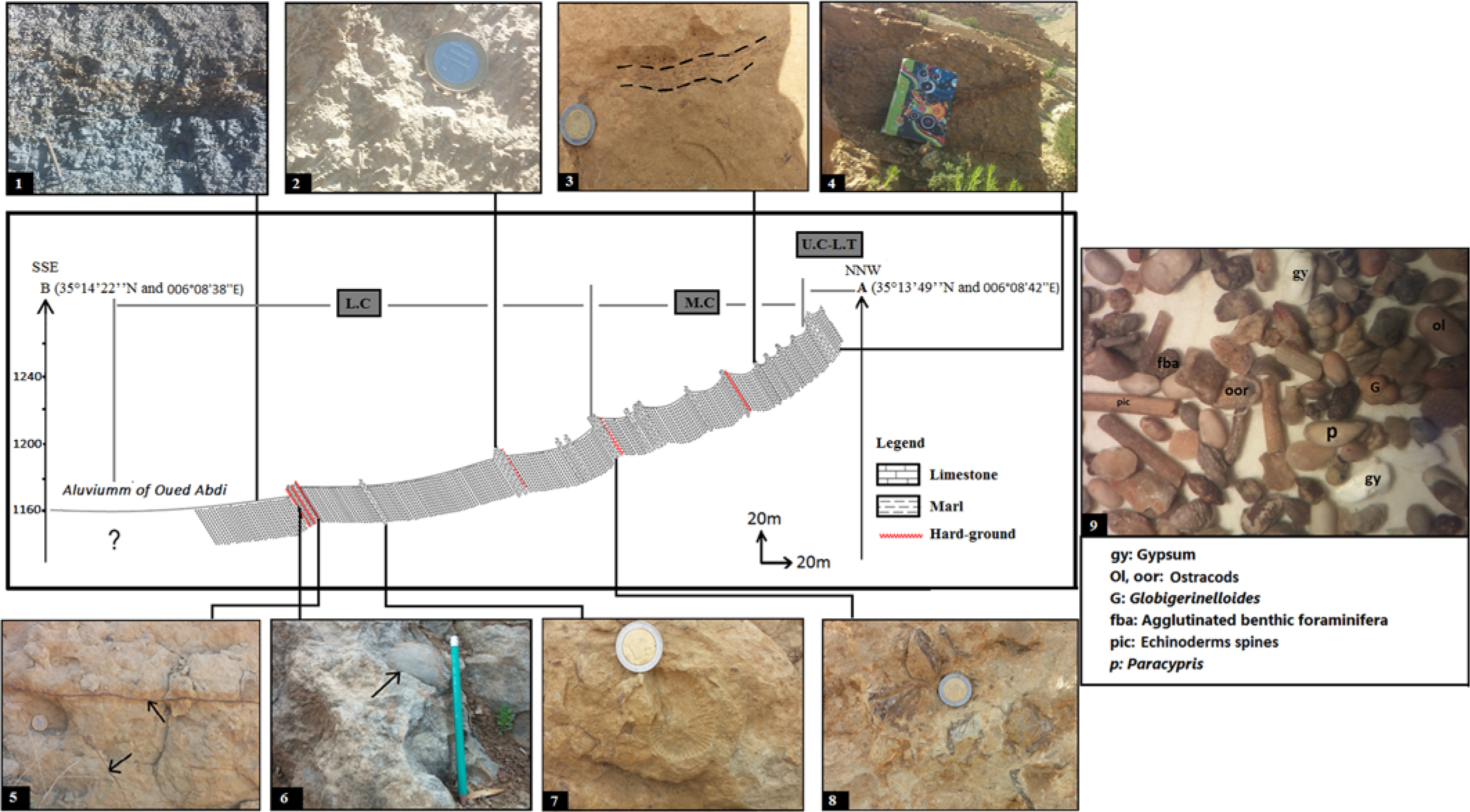

Fig. 2. Geological section of the study area (Nouader). Sub-stages: (L.C) Lower Cenomanian; (M.C) Middle Cenomanian; (U.C) Upper Cenomanian; (L.T) Lower Turonian. (1) Carbonated blue-grey marls from sample 12. (2) Limestone with oriented concentration of turritellid-like gastropods from sample 76. (3) Bioclastic limestone showing fine lineated ferruginous lamination on top of the bed taken from sample 105. (4) Surface top of bed 119 showing a very bioturbated ferruginous hard-ground. (5) Ferruginous mineralization in previous thin fractures (iron vein in black arrow) from sample 10. (6) Dark blue bioclastic limestone with large gastropods highlighted by a black arrow found in sample 10. (7) Bioclastic limestone with ammonite print Mantelliceras dixoni taken from sample 74. (8) Lumachellic limestone in sample 86. (9) Sample of marl sorting under binocular magnifying glass showing gypsum mineral and several kinds of microfossils.

3. Lithology

The Cenomanian succession of the Nouader region has an overall thickness of c. 700 m. It is mainly composed of a thick marly sequence, with generally dark colour and interspersed with calcareous layers of cm to dm thickness, with various facies (bioclastic limestones, laminated limestones and micritic limestones), which mainly occur in the upper part of the section. These lithological variations are considered to reflect relative sea-level variations that can be related to vertical movements of the basement. In detail, the relative sea-level rises and falls are recorded by sedimentary prisms whose succession defines eustatic sequences (not discussed in this article). The fossil content is numerous and varied: oysters, gastropods, ammonites, and nautiloids sometimes pyritous.

Except for the lower part of the section (masked interval of c. 150 m) that made determination of the Albian–Cenomanian limit difficult, the presence of ammonites such as Mantelliceras cf. mantelli and M. dixoni allowed the site to be given an early Cenomanian age (Robaszynski et al. Reference Robaszynski, Caron, Amédro, Dupuis, Hardenbol, Gonzales-Donoso, Llnares and Gartner1993, Reference Robaszynski, Caron, Amedro, Dupuis, Hardenbol, Gonzales Donoso, Llnares and Gartner1994). The Cenomanian succession of the Nouader site can be divided into three lithostratigraphic units, cited from bottom to top: Fahdene Formation, Bahloul Formation and Annaba Member, which is the lower term of the Kef Formation, in relation to subdivisions already established for similar levels of Central Tunisia, defined by Burollet et al. (Reference Burollet, Dumestre, Keppel and Salvador1952–4) and Burollet (Reference Burollet1956) (Fig. 3). These lithological subdivisions were redefined by Fournié (1978), and although old, they continue to be commonly used by authors working in the region (Robaszynski et al. Reference Robaszynski, Caron, Amédro, Dupuis, Hardenbol, Gonzales-Donoso, Llnares and Gartner1993, Reference Robaszynski, Caron, Amedro, Dupuis, Hardenbol, Gonzales Donoso, Llnares and Gartner1994, Reference Robaszynski, Dupuis, Gonzalez-Donoso and Linares2008, Reference Robaszynski, Faouzi Zagrarni, Caron and Amedro2010; Caron et al. Reference Caron, Dall’agnolo, Accarie, Barrera, Kauffman, Amedro and Robaszynski2006; Amédro & Robaszynski, Reference Amédro and Robaszynski2008; Chikhi-Aouimeur, Reference Chikhi-Aouimeur2010; K Chaabane, unpub. thesis, Univ. Badji Mokhtar, 2015; Kennedy & Gale, Reference Kennedy and Gale2015).

Fig. 3. Lithostratigraphic setting with the encountered formations in the region and their corresponding biostratigraphic markers modified from Burollet (Reference Burollet1956) and Amédro & Robaszynski (Reference Amédro and Robaszynski2008).

The lower part of the Fahdene Formation (lower to middle Cenomanian) is composed of dark marls and dark clayey marls (dark blue-grey) dotted with gypsum, rarely interspersed with thin hard beds of limestone and marly limestone, which include abundant ostreids, exogyrinids, pectinids and ammonites (Fig. 4a). Microfossils are less abundant, being mostly noted: globular foraminifera (Hedbergella delrioensis and H. planispira) with keeled foraminifera such as Thalmanninella apenninica and T. globotruncanoides. Near the lower–middle Cenomanian boundary, this succession includes a regressive interval with limestone facies topped by an oyster surface (Fig. 8c further below).

Fig. 4. (a) Dark grey marls of Fahdene Formation. (b) Upper part of the section showing limits between Bahloul Formation (upper Cenomanian) and Annaba Member (lower Turonian). (c) Boundary between the lower and middle Cenomanian. (d) Panoramic view of the study area.

Above that, this unit is followed by the typical Bahloul Formation (upper Cenomanian to lower Turonian), whose facies are clearly visible in this studied area; it is c. 10 m thick and has levels of finely black limestone interbedded with very hard grey marls (Fig. 4b, d). These facies are rich in organic matter (peaks of total organic carbon (TOC) reaching 2–5%), and also typified by the presence of filaments, disappearance of Rotalipora species and the almost complete absence of benthic organisms.

Finally, the Annaba Member (lower Turonian) is characterized by soft yellowish marls. Microfossils in particular are less abundant: rare benthic foraminifera, a few planktonic foraminifera mostly marked by Heterohelix sp., Hedbergella sp. in very poor state of preservation and some Whiteinella sp. Macrofossils are rare, especially ammonites, of which only Pseudaspidoceras flexuosum could be found and used as a biostratigraphic marker. From NNW to SSE, only small changes of facies can be observed, but the overall thickness of the succession, the number of limestone intercalations and the frequency of oyster-rich levels can vary considerably (Fig. 4b).

4. Materials and methods

A regular sampling step of rocks was conducted every 5–10 m in the lower part of the section (Fahdene levels), and much narrower in the upper part, because of the rapid variation of facies (Bahloul levels). The absence of continuous outcrop is responsible for sampling gaps, especially in most flat areas, covered with Quaternary deposits (masked interval at the beginning of the section). Thin-sections were also made from samples of hard limestone levels, for microfacies study purposes (20 thin-sections in all).

The soft levels (marls) were preferentially taken for a standard washing with hydrogen peroxide (soaking) and screened through two sieves of different mesh, respectively 2 mm and 63 μm. Only the residue at 63 μm was then studied and sorted. As far as possible, 250–300 individuals (planktonic foraminifera, benthic foraminifera, ostracods) have been systematically isolated, determined and counted. Of 100 sieved samples, 13 revealed no trace of microfossils. The richness of microfauna in the rest of the samples is varied and differs throughout the section from one sample to another, such as the lower part being characterized by poor richness of microfauna, where only 3–5 species of foraminifera can be counted, whereas the middle part records 8–24 species of foraminifera). Due to the uncompleted determination of ostracod fauna by experts, their results are not cited in this article.

In addition, the amount of TOC was measured. This parameter was analysed at the Agronomic Laboratory of Batna 1 University, using Pyrolyse (Rock-Eval VI), on 22 selected samples taken from Cenomanian levels and from those of the Cenomanian–Turonian transition.

The boundaries between stratigraphic subdivisions of Cenomanian sub-stages were determined using the stratigraphic range of 56 ammonites collected from the local Cenomanian succession and its transition to the Turonian, and calibrated with some index foraminifera (if present). The used biozonations are those of Caron (1985), Robaszynski & Caron (Reference Robaszynski and Caron1995) and, more recently, Amédro & Robaszynski (Reference Amédro and Robaszynski2008), who proposed an integrated correlation of ammonite and foraminifera zones between the Tethyan (Central Tunisia) and the Boreal (Western Europe) domains. The listed species are named in accordance with the enacted rules in the International Code of Zoological Nomenclature (CINZ).

5. Biostratigraphy

5.a. Ammonite zones

The ammonite faunas collected from the studied section of the Nouader site can be dated in terms of the zonal scheme proposed for Central Tunisia and Western Europe where local to interregional correlation between several successions has been suggested.

The upper Albian biostratigraphic setting is based on the works of Amédro (Reference Amédro1992, Reference Amédro2002) and Amédro et al. (Reference Amédro, Accarie and Robaszynski2005), and discussed by Gale et al. (Reference Gale, Bown, Caron, Crampton, Crowhurst, Kennedy, Petrizzo and Wray2011). This interval cannot be sampled in the study area due to the local alluvial cover of Oued Abdi.

The Cenomanian sequence is based on the proposal of Wright & Kennedy (Reference Wright and Kennedy1984), later modified by Gale (Reference Gale1995). These studies were followed by Amédro (Reference Amédro1986) and Amédro & Robaszynski (Reference Amédro and Robaszynski1999) for some French sections, and, later, Kaplan et al. (Reference Kaplan, Kennedy, Lehmann and Marcinowski1998) and Wilmsen (Reference Wilmsen2007), dealing with sequences in Germany. More recently, the scheme was revised by Amédro & Robaszynski (Reference Amédro and Robaszynski2008).

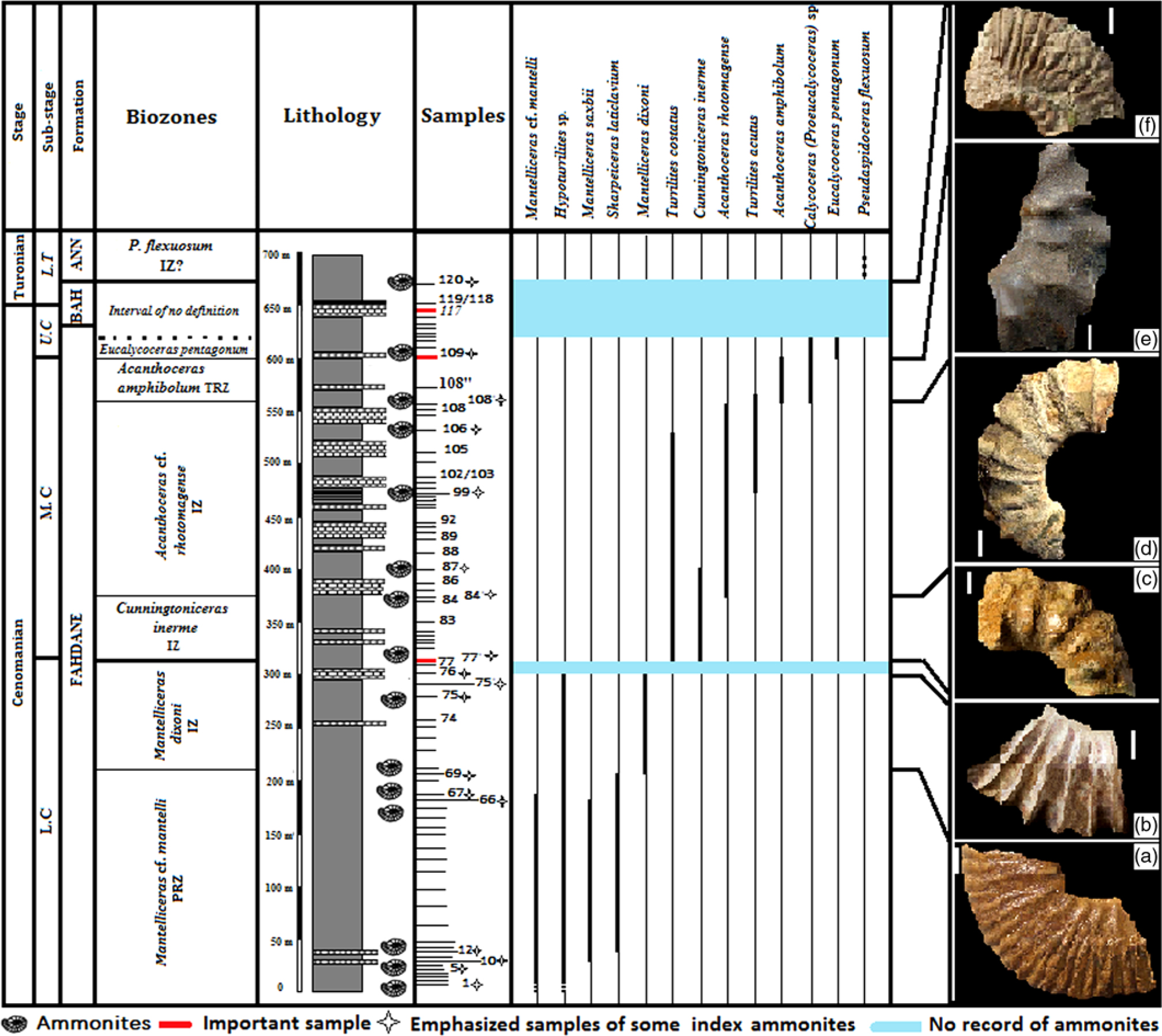

The Turonian sequence is based on the biostratigraphic scheme proposed by Wright & Kennedy (Reference Wright and Kennedy1981), which was later modified by Gale et al. (Reference Gale, Kennedy, Voigt and Walaszczyk2005). Robaszynski et al. (Reference Robaszynski, Caron, Dupuis, Amedro, Gonzalez Donoso, Linares, Hardenbol, Gartner, Calandra and Deloffre1990, Reference Robaszynski, Caron, Amédro, Dupuis, Hardenbol, Gonzales-Donoso, Llnares and Gartner1993, Reference Robaszynski, Caron, Amedro, Dupuis, Hardenbol, Gonzales Donoso, Llnares and Gartner1994, Reference Robaszynski, Dupuis, Gonzalez-Donoso and Linares2008, Reference Robaszynski, Faouzi Zagrarni, Caron and Amedro2010) developed a zonal sequence for the Upper Albian, Cenomanian and Turonian mainly based on sections in the Kalaat Senan region (Central Tunisia). The Cenomanian succession of the Nouader site is of interval zones, taxon range zones, and partial range zones (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5. Biostratigraphic distributions of the ammonite species recorded from the Cenomanian of the Nouader site, according to the first appearance. (BAH) Bahloul; (ANN) Annaba; (L.C) lower Cenomanian; (M.C) middle Cenomanian; (U.C) upper Cenomanian; (L.T) lower Turonian. Respectively: (a) Mantelliceras cf. mantelli (Sowerby, Reference Sowerby1812–22 [1814], pls. 45–78); (b) Mantelliceras dixoni Spath, Reference Spath1926a, b; (c) Cunningtoniceras inerme (Pervinquière, Reference Pervinquière1907); (d) Acanthoceras rohotomagense (Brongniart, Reference Brongniart, Cuvier and Brongniart1822); (e) Acanthoceras amphibolum (Morrow, 1935); (f) Eucalycoceras pentagonum (Jukes-Browne, 1896).

5.a.1. Lower Cenomanian ammonite zones

Mantelliceras cf. mantelli Partial Range Zone (PRZ) (Fig. 5a). Zone between the disappearance of Mantelliceras cobbani and the first appearance of M. dixoni according to several authors (Rawson et al. Reference Rawson, Curry, Dilley, Hancock, Kennedy, Neale, Wood and Worssam1978, Reference Rawson, Dhondt, Hancock and Kennedy1996; Kennedy, Reference Kennedy1984; Wright & Kennedy, Reference Kennedy1984; Amédro, Reference Amédro1986; Clavel, Reference Clavel1986; Christensen, Reference Christensen1990; Robaszynski et al. Reference Robaszynski, Caron, Amédro, Dupuis, Hardenbol, Gonzales-Donoso, Llnares and Gartner1993, Reference Robaszynski, Caron, Amedro, Dupuis, Hardenbol, Gonzales Donoso, Llnares and Gartner1994; Kaplan et al. Reference Kaplan, Kennedy, Lehmann and Marcinowski1998; Kennedy et al. Reference Kennedy, Cobban, Hancock and Gale2005, Reference Kennedy, Amédro, Robaszynski and Jagt2011, Reference Kennedy, Walaszczy, Gale, Dembicz and Praszkier2013; Ellis et al. Reference Ellis, Bowen, Campbell, Knill, McKirdy, Prosser, Vincent and Wilson2007; Lasseur et al. Reference Lasseur, Neraudeau, Guillocheau, Robin, Hanot, Videt and Mavrieux2008; Reboulet et al. Reference Reboulet, Guiraud, Colombié and Carpentier2013). In our region, the appearance of Mantelliceras dixoni is confirmed in sample 69, while no trace of M. cobbani has been found (covered by alluvium), but this area has been proposed due to the presence of M. dixoni at the top, as well as the litho-biological similarities with those of Kalaat Senan in Central Tunisia. The Mantelliceras cf. mantelli Zone extends from the beginning of the section (0 m) to 210 m thick.

The occurrence of this species is more common in the Mantelliceras mantelli Zone of the lower Cenomanian, but it does not extend into the succeeding Mantelliceras dixoni Zone. The species ranges from England to Northern Ireland, France, Germany, Russia, Iran, Kazakhstan, Morocco, Algeria, Tunisia, KwaZulu-Natal in South Africa, Madagascar, Southern India, and Japan (Kennedy & Gale, Reference Kennedy and Gale2017).

Mantelliceras dixoni Interval Zone (IZ) (Fig. 5b). This zone is bounded by the following respective appearances of Mantelliceras dixoni (sample 69) and Cunningtoniceras inerme (sample 77’) according to numerous authors (Rawson et al. Reference Rawson, Curry, Dilley, Hancock, Kennedy, Neale, Wood and Worssam1978; Kennedy, Reference Kennedy1984; Wright & Kennedy, Reference Wright and Kennedy1984, Reference Wright and Kennedy1987; Amédro, Reference Amédro1986; Clavel, Reference Clavel1986; Christensen, Reference Christensen1990; Robaszynski et al. Reference Robaszynski, Caron, Amédro, Dupuis, Hardenbol, Gonzales-Donoso, Llnares and Gartner1993, Reference Robaszynski, Caron, Amedro, Dupuis, Hardenbol, Gonzales Donoso, Llnares and Gartner1994; Kaplan et al. Reference Kaplan, Kennedy, Lehmann and Marcinowski1998; Kennedy et al. Reference Kennedy, Cobban, Hancock and Gale2005; Ellis et al. Reference Ellis, Bowen, Campbell, Knill, McKirdy, Prosser, Vincent and Wilson2007; Lasseur et al. Reference Lasseur, Neraudeau, Guillocheau, Robin, Hanot, Videt and Mavrieux2008; Kennedy et al. Reference Kennedy, Amédro, Robaszynski and Jagt2011, Reference Kennedy, Walaszczy, Gale, Dembicz and Praszkier2013; Reboulet et al. Reference Reboulet, Guiraud, Colombié and Carpentier2013). It extends from 210 m to 315 m. M. dixoni occurrence is restricted to the upper lower Cenomanian dixoni Zone of Southern England, France (the Boulonnais, Haute Normandie, Sarthe, Jura, Basses-Alpes and Bouches-du-Rhône), Germany, Switzerland, Romania, Iran, Northern Mexico, El Salvador and Madagascar (Kennedy & Gale, Reference Kennedy and Gale2017). The record of M. cf. dixoni would indicate non-extension into the lower middle Cenomanian Cunningtoniceras inerme Zone.

5.a.2. Middle Cenomanian ammonite zones

Cunningtoniceras inerme Interval Zone (Fig. 5c). Interval zone between the appearance of Cunningtoniceras inerme (in sample 77’) and the appearance of Acanthoceras cf. rhotomagense (sample 84’). This interval zone is cited by different authors such as Wright & Kennedy (Reference Wright and Kennedy1987), Christensen (Reference Christensen1990), Hancock (Reference Hancock1991), Kennedy & Juignet (Reference Kennedy and Juignet1993), Robaszynski et al. (Reference Robaszynski, Caron, Amédro, Dupuis, Hardenbol, Gonzales-Donoso, Llnares and Gartner1993, Reference Robaszynski, Caron, Amedro, Dupuis, Hardenbol, Gonzales Donoso, Llnares and Gartner1994), Gale (Reference Gale1995), Tröger et al. (Reference Tröger, Kennedy, Bumett, Caron, Gale and Robaszynski1996), Kaplan et al. (Reference Kaplan, Kennedy, Lehmann and Marcinowski1998), Kennedy et al. (Reference Kennedy, Cobban, Hancock and Gale2005, Reference Kennedy, Amédro, Robaszynski and Jagt2011, Reference Kennedy, Walaszczy, Gale, Dembicz and Praszkier2013) and Reboulet et al. (Reference Reboulet, Guiraud, Colombié and Carpentier2013). It has a range from 315 m to 375 m and indicates the lower middle Cenomanian. The index species is known from Southern England, France (Sarthe and Provence), Switzerland, Germany, Turkmenistan, Morocco, NE Algeria, Central Tunisia, Hokkaido, Japan, and Texas in the United States (Kennedy & Gale, Reference Kennedy and Gale2017). It ranges into the succeeding Turrilites costatus Subzone in the Acanthoceras rhotomagense Zone.

Acanthoceras cf. rhotomagense Interval Zone (Fig. 5d). Zone bounded by the occurrence of Acanthoceras cf. rhotomagense (sample 84’) and A. amphibolum (sample 108’) (Dubourdieu & Sigal, Reference Dubourdieu and Sigal1949; Dubourdieu, Reference Dubourdieu1956; Rawson et al. Reference Rawson, Curry, Dilley, Hancock, Kennedy, Neale, Wood and Worssam1978; Birkelund et al. Reference Bireklund, Hancock, Hart, Rawson, Remane, Robaszynski, Schmid and Surlyk1984; Kennedy, Reference Kennedy1984; Amédro, Reference Amédro1986; Clavel, Reference Clavel1986; Wright & Kennedy, Reference Wright and Kennedy1987; Christensen, Reference Christensen1990; Kennedy & Juignet, Reference Kennedy and Juignet1993; Robaszynski et al. Reference Robaszynski, Caron, Amédro, Dupuis, Hardenbol, Gonzales-Donoso, Llnares and Gartner1993, Reference Robaszynski, Caron, Amedro, Dupuis, Hardenbol, Gonzales Donoso, Llnares and Gartner1994; Kaplan et al. Reference Kaplan, Kennedy, Lehmann and Marcinowski1998; Kennedy et al. Reference Kennedy, Cobban, Hancock and Gale2005, Reference Kennedy, Amédro, Robaszynski and Jagt2011, Reference Kennedy, Walaszczy, Gale, Dembicz and Praszkier2013; Ellis et al. Reference Ellis, Bowen, Campbell, Knill, McKirdy, Prosser, Vincent and Wilson2007; Lasseur et al. Reference Lasseur, Neraudeau, Guillocheau, Robin, Hanot, Videt and Mavrieux2008; Kennedy & Klinger, Reference Kennedy and Klinger2010; Mosavina & Wilmsen, Reference Mosavina and Wilmsen2011; Reboulet et al. Reference Reboulet, Guiraud, Colombié and Carpentier2013). This interval is c. 185 m thick (from 375 m to 560 m). It indicates the middle middle Cenomanian, and the index species occurs in Western Europe from Northern Ireland through England, France from the Boulonnais to Provence, Switzerland, Germany, Bornholm in the Baltic, Northern Spain, Romania, Dagestan, Turkmenistan and Northern Iran, Algeria, Tunisia, and possibly Peru and Bathurst Island, Northern Australia (Kennedy & Gale, Reference Kennedy and Gale2017).

Acanthoceras amphibolum Total Range Zone (Fig. 5e). This species has other synonyms such as Acanthoceras. This interval corresponds to the total range of Acanthoceras amphibolum (Kennedy & Juignet, Reference Kennedy and Juignet1993; Robaszynski et al. Reference Robaszynski, Caron, Amédro, Dupuis, Hardenbol, Gonzales-Donoso, Llnares and Gartner1993, Reference Robaszynski, Caron, Amedro, Dupuis, Hardenbol, Gonzales Donoso, Llnares and Gartner1994; Kennedy et al. Reference Kennedy, Cobban, Hancock and Gale2005, Reference Kennedy, Amédro, Robaszynski and Jagt2011, Reference Kennedy, Walaszczy, Gale, Dembicz and Praszkier2013; Wilmsen, Reference Wilmsen2007; Amédro & Robaszynski, Reference Amédro and Robaszynski2008; Kennedy & Klinger, Reference Kennedy and Klinger2010; Reboulet et al. Reference Reboulet, Guiraud, Colombié and Carpentier2013), a species sometimes referred as A. alvaradoense Moreman, 1942 or A. hazzardi Stephenson, 1952.

It is recorded from 560 m to 600 m in the stratigraphic section where it indicates the upper middle Cenomanian. The index species occurs in Egypt, the United States (New Mexico, Texas, Kansas, Colorado, Wyoming, South Dakota, Montana), Japan and Nigeria (Kennedy & Cobban, Reference Kennedy and Cobban1990; Kennedy & Gale, Reference Kennedy and Gale2017), as also in Tunisia and Algeria.

5.a.3. Upper Cenomanian ammonite zone

Eucalycoceras pentagonum Partial Range Zone (PRZ) (Fig. 5f). This zone is placed between the last occurrence of Acanthoceras amphibolum in sample 109 and the first appearance of Pseudaspidoceras flexuosum in sample 120. Several authors had discussed it as an assemblage zone, notably Kennedy (Reference Kennedy1984), Robaszynski et al. (Reference Robaszynski, Caron, Amédro, Dupuis, Hardenbol, Gonzales-Donoso, Llnares and Gartner1993, Reference Robaszynski, Caron, Amedro, Dupuis, Hardenbol, Gonzales Donoso, Llnares and Gartner1994), Gale et al. (Reference Gale, Kennedy, Voigt and Walaszczyk2005), Amédro & Robaszynski (Reference Amédro and Robaszynski2008), Kennedy & Bilotte (Reference Kennedy and Bilotte2014), Kennedy et al. (Reference Kennedy, Amédro, Robaszynski and Jagt2011, Reference Kennedy, Walaszczy, Gale, Dembicz and Praszkier2013) and Kennedy & Gale (Reference Kennedy and Gale2015). It has a local range from 600 m to the end of the section, near the thickness value of 670 m. Indicating the lower-middle upper Cenomanian, with reported occurrences in Colorado, Algeria, Tunisia, France, England, Germany and Spain (Kennedy & Gale, Reference Kennedy and Gale2017).

In the studied section, there is a single specimen of E. pentagonum collected, just above the bed of sample 109, and the remaining part of the following succession did not yield any other ammonites until sample 120, where a specimen of Pseudaspidoceras flexuosum is recorded. In this situation it is possible that the sedimentary record exists for the middle and upper part of the upper Cenomanian, but the absence of ammonites does not allow us to recognize the correlative biozones. It is known that E. pentagonum is a lower upper Cenomanian species that occurs together with Calycoceras guerangeri (Amédro & Robaszynski, Reference Amédro and Robaszynski2008) (see Fig. 9 (right column) further below). In addition, both in sample 112 and upwards there is a noticeable decrease in the percentage of benthic foraminifera against a remarkable increase in the planktonic foraminifera rate (Fig. 6). Therefore, an interval of no definition could also be suggested from the range of the E. pentagonum Zone to the P. flexuosum Zone as a distal deep facies succession where Vascoceratids and other shallow-water ammonites are normally absent.

Fig. 6. Biostratigraphic distributions of the planktonic and benthic foraminiferan species recorded from the Cenomanian of Nouader, according to the first and last appearance.

5.b. Planktonic foraminifera biozones

Five biozones of early Cenomanian to Turonian age have been identified (Fig. 6).

5.b.1. Thalmanninella brotzeni Zone (= Globotruncanoides)

It dates lower Cenomanian to lower middle Cenomanian and contains: Hedbergella planispira, H. delrioensis, H. simplex, Heterohelix sp., Guembelitria sp., Globigerinelloides sp., Praeglobotruncana delrioensis, Rotalipora montsalvensis, Thalmanninella appenninica, Th. balernaensis, Th. brotzeni and Praeblobotruncana stephani. These foraminifera have been found in the less fossiliferous dark marls with rare limestone intercalations (Fahdene Formation). Its thickness is c. 350 m, counting from the beginning of the stratigraphic section (0 m to 350 m).

5.b.2. Thalmanninella reicheli Zone (middle Cenomanian)

The first occurrence of Tahlmanninella reicheli (Fig. 7b) was at sample number 77’ associated with: Hedbergella delrioensis, Thalmanninella appenninica, Th. globotruncanoides, H. planispira, Heterohelix mormani, Praeglobotruncana stephani, H. simplex, Rotalipora montsalvensis and Praeglobotruncana delrioensis. The last occurrence is from sample 87. The lithofacies is similar to the previous one, of sparsely fossiliferous dark marls with rare intercalations of limestone.

Fig. 7. (a) Thalmanninella greenhornensis taken from sample 106; (b) Thalmanninella reicheli from sample 83; (c) Rotalipora montsalvensis found in sample 75; (d) Rotalipora cushmani first occurrence in sample 88.

5.b.3. Rotalipora cushmani Zone (middle to upper Cenomanian)

This biozone is defined by the appearance of the index species (Fig. 7d), after the last occurrence of the species: Thomasinella appenninica and Th. brotzeni, accompanied by that of the first whiteinels (Whiteinella baltica, followed by W. brittonensis and W. paradubia), and slightly upwards, by that of Praeglobotruncana gibba. These few species come to diversify the previous assembly. The facies differs from the previous one; it is about yellowish to greenish marls alternated with phosphated, bioclastic micritic limestones (top of Fahdene Formation and beginning of the Bahloul Formation).

5.b.4. Whiteinella archaeocretacea Zone (upper Cenomanian to lower Turonian)

It is characterized by the presence of many species of the genus Whiteinella including W. archaeocretacea and W. paradubia. The keeled forms are absent. Previous species persist, with the exception of Praeglobotruncana delrioensis. There are also P. gibba and Heterohelix globulosa. Lithologically, this biozone is characterized by facies of marly limestone in black platelets rich in organic matter (Bahloul Formation). The Whiteinella archaeocretacea Zone was known in numerous pre-Atlantic basins (Noemi & Allison, Reference Noemi and Allison2005, Zagrarni et al. Reference Zagrarni, Negra and Hanini2008; Robaszynski et al. Reference Robaszynski, Faouzi Zagrarni, Caron and Amedro2010; Ruault-Djerrab et al. Reference Ruault-Djerrab, Ferré and Kechid-Benkherouf2012, Reference Ruault-Djerrab, Kechid-Benkherouf and Djerrab2014) and it coincides with an anoxic period materialized by rich organic carbon sediments.

5.b.5. Helvetoglobotruncana helvetica Zone (lower Turonian)

Its first appearance is observed in a thin-section of sample 117, associated with Hedbergella sp., Heterohelix sp., H. globulosa, Globigerinelloides sp., Whiteinella sp., W. baltica, W. praehelvetica and Lunatriella sp. This biozone is recorded by a metric order limestone, with beige colour, phosphatic and ferruginous (Annaba Member).

5.c. Cenomanian sub-stage boundaries

5.c.1. Vraconian – lower Cenomanian boundary

The boundary between the Vraconnian and the lower Cenomanian could not be located with precision due to the alluvial cover of Oued Abdi valley.

5.c.2. Lower–middle Cenomanian boundary

As in the Anglo-Parisian basin and Central Tunisia, a similar gap was found between the level of appearance of Cunningtoniceras inerme at 315 m and that of Acanthoceras cf. rhotomagense at 375 m. The base of the middle Cenomanian can be placed at 315 m at the level of sample 77’ (Fig. 5), insofar as the genus Cunningtoniceras is considered by several authors to be typical of the middle Cenomanian (Turkmenia: Wright & Kennedy, Reference Kennedy1984, Reference Kennedy and Cobban1990; Atabekian, Reference Atabekian1985; Amédro, Reference Amédro1986; Texas: Kennedy & Cobban, Reference Kennedy and Cobban1990; Hancock, Reference Hancock1991; Amédro, Reference Amédro1993; Tunisia: Robaszynski et al. Reference Robaszynski, Caron, Amédro, Dupuis, Hardenbol, Gonzales-Donoso, Llnares and Gartner1993, Reference Robaszynski, Caron, Amedro, Dupuis, Hardenbol, Gonzales Donoso, Llnares and Gartner1994; Boulonnais: Robaszynski et al. Reference Robaszynski, Caron, Amedro, Dupuis, Hardenbol, Gonzales Donoso, Llnares and Gartner1994; Sarthe: Kennedy & Juignet, Reference Kennedy and Juignet1993, Reference Kennedy and Juignet1994; England: Paul et al. Reference Paul, Mitchell, Marshall, Leary, Gale, Duane and Fitchfield1994; Gale, Reference Gale1995; Kazakhstan: Marcinowski et al. Reference Marcinowski, Walaszczyk and Olszewskanejbert1996; Gale et al. Reference Gale, Kennedy, Voigt and Walaszczyk2005; Germany & England: Wilmsen, Reference Wilmsen2007; Central Tunisia and NW Europe correlation: Amédro & Robaszynski, Reference Amédro and Robaszynski2008; Madagascar: Kennedy et al. Reference Kennedy, Walaszczy, Gale, Dembicz and Praszkier2013; France: Reboulet et al. Reference Reboulet, Guiraud, Colombié and Carpentier2013, Spain: Kennedy & Bilotte, Reference Kennedy and Bilotte2014; Tunisia: Kennedy & Gale, Reference Kennedy and Gale2015, Reference Kennedy and Gale2017). This boundary is also confirmed and calibrated by the first occurrence of the index species Thalmanninella reicheli (see Robaszynski & Caron, Reference Robaszynski and Caron1995; Amédro & Robaszynski, Reference Amédro and Robaszynski2008) associated to Rotalipora montsalvensis, and Praeglobotruncana delrioensis (Figs 6, 8). According to Kennedy (Reference Kennedy1994), the lowest middle Cenomanian faunas are characterized by different species of the genus Cunningtoniceras (C. inerme, C. cunningtoni) rather than Acanthoceras rhotomagense in the Northern Lower Temperate and Tethyan Realms.

Fig. 8. Calibration of Cenomanian boundaries and biozones of the Nouader site. (a) Middle Cretaceous biozones by planktonic foraminifera (Robaszynski & Caron, Reference Robaszynski and Caron1995). (b) Ammonites and planktonic foraminiferal biozones (this work). (c) Middle Cretaceous biozones of ammonites and planktonic foraminifera (Gradstein et al. Reference Gradstein, Ogg, Smith, Bleeker and Lourens2004). Sub-stages: (L.C) lower Cenomanian; (M.C) middle Cenomanian; (U.C) upper Cenomanian; (L.T) lower Turonian. Formations: (BAH) Bahloul; Member: (ANN) Annaba. Concerned biozones are highlighted in black. Red line highlights the Cenomanian Stage.

5.c.3. Middle–upper Cenomanian boundary

The base of the upper Cenomanian corresponds to the diversification of the genera Calycoceras and Eucalycoceras that already existed in the middle Cenomanian. Indeed, this boundary is not defined by the appearance of a common species, contrary to the previous boundary, but according to Kennedy (Reference Kennedy1984) the most striking event is the disappearance of the genus Acanthoceras (from sample 109 upwards). At this stratigraphic position, the appearance of Eucalycoceras pentagonum has been generally considered as typical of the lower upper Cenomanian (Thomel, Reference Thomel1972; Wright & Kennedy, Reference Wright and Kennedy1990; Amédro & Robaszynski, Reference Amédro and Robaszynski2008; Kennedy et al. Reference Kennedy, Amédro, Robaszynski and Jagt2011, Reference Kennedy, Walaszczy, Gale, Dembicz and Praszkier2013; Reboulet et al. Reference Reboulet, Guiraud, Colombié and Carpentier2013; Kennedy & Bilotte, Reference Kennedy and Bilotte2014; Kennedy & Gale, Reference Kennedy and Gale2015, Reference Kennedy and Gale2017). The calibration of these data with foraminifera marks this boundary in the upper part of the Rotalipora cushmani Zone, according to several authors (Robaszynski & Caron, Reference Robaszynski and Caron1995; Gradstein et al. Reference Gradstein, Ogg, Smith, Bleeker and Lourens2004; Amédro & Robaszynski, Reference Amédro and Robaszynski2008) (Fig. 6). For this purpose, the location of the middle Cenomanian – upper Cenomanian boundary in our study area could be placed at 600 m, precisely at sample 109 (Fig. 5).

5.c.4. Cenomanian–Turonian boundary

The appearance of Pseudaspidoceras flexuosum in sample 120 indicates an early Turonian age within this zone, according to Dubourdieu (Reference Dubourdieu1956) and Birkelund et al. (Reference Bireklund, Hancock, Hart, Rawson, Remane, Robaszynski, Schmid and Surlyk1984). No other ammonite species have been found within this interval, but the calibration with planktonic foraminifera and other criteria, such as (1) the absence of specimens of the genus Rotalipora and the appearance of an association consisting of: Whiteinella baltica, W. brittonensis, W. paradubia, W. archaeocretacea, W. aprica, Dicarinella hagni, D. imbricata, Praeglobotruncana gibba, P. stephani, Hedbergella delrioensis, H. simplex, Heterohelix globulosa and H. moremani between the upper limestones of sample 117 and the black shales of samples 118–119, (2) the first appearance of filaments, (3) the first occurrence of Helvetoglobotruncana helvetica at the level of sample 117 and (4) the appearance of dark grey (black), finely laminated and very compacted facies, suggest that the Cenomano-Turonian boundary could be placed at this level, precisely at 650 m (Figs 5–8).

The stratigraphic level recorded by sample 120 characterizes the upper part of the Whiteinella archaeocretacea (Member of Annaba), belonging to the lower Turonian interval above the OAE2 anoxia crisis (Caron, Reference Caron, Bolli, Saunders and Perch-Nielsen1985; Robaszynski et al. Reference Robaszynski, Caron, Dupuis, Amedro, Gonzalez Donoso, Linares, Hardenbol, Gartner, Calandra and Deloffre1990, Reference Robaszynski, Caron, Amédro, Dupuis, Hardenbol, Gonzales-Donoso, Llnares and Gartner1993, Reference Robaszynski, Caron, Amedro, Dupuis, Hardenbol, Gonzales Donoso, Llnares and Gartner1994, Reference Robaszynski, Faouzi Zagrarni, Caron and Amedro2010; Caron et al. Reference Caron, Dall’agnolo, Accarie, Barrera, Kauffman, Amedro and Robaszynski2006; Amédro & Robaszynski, Reference Amédro and Robaszynski2008; Zagrarni et al. Reference Zagrarni, Negra and Hanini2008; Ruault-Djerrab et al. Reference Ruault-Djerrab, Ferré and Kechid-Benkherouf2012, Reference Ruault-Djerrab, Kechid-Benkherouf and Djerrab2014; Kennedy & Bilotte, Reference Kennedy and Bilotte2014; Kennedy & Gale, Reference Kennedy and Gale2015).

5.d. Interregional correlations

The ammonite succession of the Nouader site, as interpreted from material previously described by Pervinquière (Reference Pervinquière1907), Dubourdieu (Reference Dubourdieu1956) and our own collections, reveals an interval from the lower Cenomanian Mantelliceras cf. mantelli Zone to the upper Cenomanian Eucalycoceras pentagonum Zone, but is incomplete. Whether this is a reflection of the lack of exposure at some levels, primary absence, or non-preservation of ammonites, or all three, is unclear. It should be noted that elements of the Stoliczkaia africana, Graysonites azregensis, G. cobbani, Paraconlinoceras aff. barcusi, Metoicoceras geslinianum, Pseudaspidoceras pseudonodosoides and Watinoceras sp. zones faunas recognized from Central Tunisia in the work of Robaszynski et al. (Reference Robaszynski, Caron, Amédro, Dupuis, Hardenbol, Gonzales-Donoso, Llnares and Gartner1993) and elements of the Arrhaphoceras briacensis, Acanthoceras jukesbrownei, Calycoceras guerangeri, Neocardioceras juddii and Watinoceras devonense zones faunas found in the Anglo-Parisian basin (Amédro & Robaszynski Reference Amédro and Robaszynski2001) have not been recognized in the studied succession.

The interregional correlation table proposed in Figure 9 shows that the ammonite zones of E and NW Europe (Boreal and north Tethyan domains) and those of Tunisia and NE Algeria (southern Tethyan domain) have numerous kinships between them. Nevertheless, several intervals have no direct correlation such as: Stoliczkaia africana in Central Tunisia (Amédro & Robaszynski, Reference Amédro and Robaszynski2008), Stoliczkaia dispar in the Paris–London Basin and Westphalia (Amédro, Reference Amédro1992, Reference Amédro2002, Reference Amédro2008; Robaszynski et al. Reference Robaszynski, Amédro, González-Donoso, Linares, Bulot, Ferry and Grosheny2007; Amédro & Robaszynski, Reference Amédro and Robaszynski2008) and West Kazakhstan and Ukraine with Southern England (Gale Reference Gale1995; Hancock, Reference Hancock2003), Graysonites azregensis and G. cobbani in Central Tunisia (Amédro & Robaszynski, Reference Amédro and Robaszynski2008), Paraconlinoceras aff. barcusi in Central Tunisia (Amédro & Robaszynski, Reference Amédro and Robaszynski2008), Metoicoceras geslinianum in Central Tunisia, Paris–London Basin and Westphalia, and West Kazakhstan and Ukraine with Southern England, respectively (Gale et al. Reference Gale1995; Hancock, Reference Hancock2003; Amédro & Robaszynski, Reference Amédro2008), Pseudaspidoceras pseudonodosoides in Central Tunisia (Amédro & Robaszynski, Reference Amédro2008) and Algeria–Tunisian borders (Dubourdieu, Reference Dubourdieu1956), Neocardioceras judii in the Paris–London Basin and Westphalia (Amédro & Robaszynski, Reference Amédro2008), and West Kazakhstan and Ukraine with Southern England (Gale et al. Reference Gale1995; Hancock, Reference Hancock2003), Watinoceras sp. in Central Tunisia and the Paris–London Basin and Westphalia (Amédro & Robaszynski, Reference Amédro and Robaszynski2008) and Fegesia catinus in the Paris–London Basin and Westphalia (Amédro & Robaszynski, Reference Amédro and Robaszynski2008). These coincide in particular with stage boundaries (eustatic events, lowering of sea-level). But on the other hand, at these levels there is a remarkable episodic occurrence of ammonites with North American affinities in Tunisia and Algeria, successively: (1) at the limit between Albian (Vraconnian) and Cenomanian: Graysonites (only in Tunisia but no record in NE Algeria); (2) in the middle Cenomanian: Paraconlinoceras barcusi (in Tunisia), Acanthoceras amphibolum (recorded in both Tunisia and Algeria); (3) at the Cenomanian–Turonian boundary: Pseudaspidoceras pseudonodosoides and Watinoceras sp. (in Tunisia but none in NE Algeria), Pseudaspidoceras flexuosum (in both Tunisia and NE Algeria). These successive phases of migration are probably linked to eustatic events change.

Fig. 9. Boundaries and correlation attempt of Cenomanian Stage and sub-stages in, respectively: (1) Central Tunisia at the first time by Pervinquière (Reference Pervinquière1907); (2) England; (3) Algerian–Tunisian borders; (4) France; (5) West Kazakhstan and Ukraine with southern England; (6a) Paris–London Basin and Westphalia; (6b) Central Tunisia by Amédro & Robaszynski (Reference Amédro and Robaszynski2008); (7) Algeria. The up- and down- pointing arrows indicate respectively the first and last appearances of the taxa concerned.

Although with an incomplete record in the continuous and thicker series of the Nouader site, the local ammonite zonation can be correlated with interregional data through the known biostratigraphic range of several key species, especially for the lower and middle part of the Cenomanian stage. The lower upper Cenomanian has yielded Eucalycoceras pentagonum (Jukes-Browne, 1896) at the top of the Zone of Acanthoceras amphibolum, but there are no indicators of the succeeding geslinianum, pseudonodoides and Watinoceras sp. Zones. Indeed, it suggests that this level is already lower upper Cenomanian, as this is a guerangeri Zone species in Western Europe and Central Tunisia sequences (Amédro & Robaszynski, Reference Amédro and Robaszynski2008; Kennedy & Gale, Reference Kennedy and Gale2015). The fauna of the pentagonum Partial Range Zone perhaps also indicates a correlation with the guerangeri Zone. After this interval, there is a further major gap in the ammonite faunas sampled from the section, with any record matching with the middle upper Cenomanian to lowermost Turonian geslinianum, juddii and devonense Zones of the Western European standard sequence, or the geslinianum, pseudonodosoides and Watinoceras sp. Zones of the Kalaat Senan sequence (Amédro & Robaszynski, Reference Amédro and Robaszynski2008). Therefore, the middle and upper part of the upper Cenomanian sedimentary record does exist locally, but due to the failure to find further specimens, the correlative ammonite zones cannot be recognized.

In contrast, Segura et al. (Reference Segura, Barroso-Barcenilla, Callapez, García-Hidalgo and Gil-Gil2014) have recognized the main depositional episodes in the upper Cenomanian – lower Santonian of the Iberian and West Portuguese basins; they presented that the sedimentary and palaeontological successions of the northern part of the Iberian Basin (Southern Cantabrian Range) showed a nearly continuous record in marly materials of relatively deep and open inner platform with ammonites. In addition, the ammonite succession in the southern part of the Djebel Mrhila section in Central Tunisia yields marker species of the guerangeri Zone, but there are no indicators of the succeeding geslinianum Zone; instead, the dolomites of the Bahloul Formation yield poorly preserved representatives of the highest Cenomanian Neocardioceras juddii/ Pseudaspidoceras (Kennedy & Gale, Reference Kennedy and Gale2015).

All of these points demonstrate the existence of numerous relationships between the Boreal and Tethyan Realms and their ammonite faunas, not only between Northwestern to Eastern Europe, Tunisia and NE Algeria but also between the North American West Interior and NE Algeria.

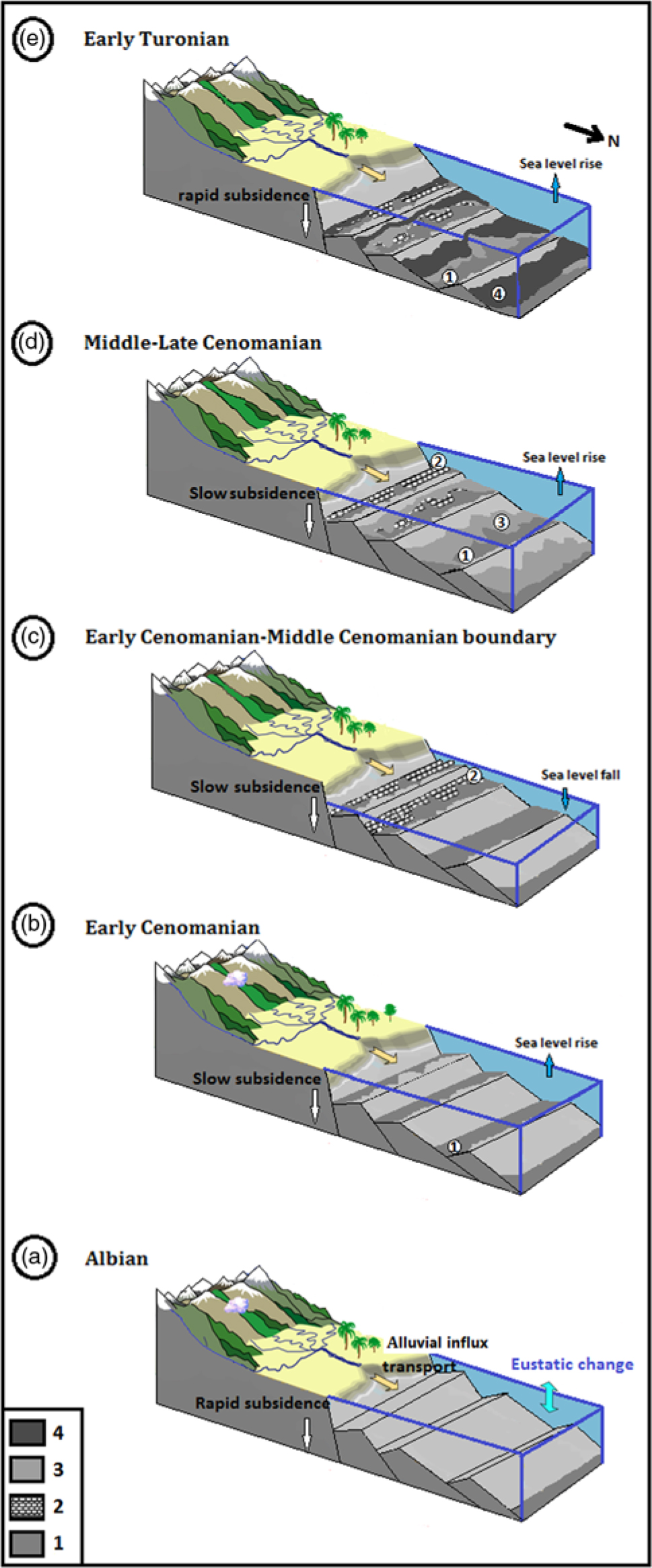

6. Palaeogeography and palaeoenvironmental evolution

For the Eastern Atlas domain, there is only a single Late Cretaceous model of palaeogeographic reconstruction proposed in the literature (M Herkat, unpub. thesis, Université d’Alger USTHB, 1999; Herkat & Guiraud Reference Herkat and Guiraud2006), which shows a structured palaeogeography in blocks tilted from the latemost Albian onwards. These authors propose the existence of a low sloping ramp, whose depths grow from west to east, and successively distinguish a proximal, median and distal transition ramp, and finally the basin. A rapid subsidence intervened at the latemost Albian due to the interaction of active tilted blocks translating the set of deep faults, and a distortion tectonic phase affected the entire Auresian basin (Fig. 10a). Subsidence rate gradually declined at the Cenomanian and resumed at the beginning of the Turonian, and neritic conditions were maintained. The integration of the studied section in this palaeogeographic scheme, modified according to the new data, shows that the Nouader region is located on the distal ramp area.

Fig. 10. Model of palaeogeographical and palaeoenvironmental reconstruction proposed for the latemost Albian to early Turonian interval in the Nouader region. (a) Albian depositional setting; (b) lower Cenomanian high-level marine prism with marly sedimentation and rare limestone intercalations of the lower part of Fahdene Formation (1); (c) lower Cenomanian to middle Cenomanian transition showing a break on sedimentation (the Trough) related to a regressive interval recorded by limestone facies topped by an oyster surface (2); (d) middle to upper Cenomanian transgressive interval with limestone and marl–limestone facies from the upper part of Fahdene Formation (3); (e) lower Turonian high-level marine prism with low-energy black shale facies of Bahloul Formation (4).

6.a. Lower Cenomanian

The lower Cenomanian has a low percentage of planktonic foraminifera with a markedly low specific diversity. Radiolarians are rare, often even completely absent. There are common mineral elements, such as gypsum and pyrite (Fig. 2, plate 9). Macrofossils, including ammonites, are rare but often pyritous, not to mention the main dark colour of marls and clayey marls facies. Poor oxygenation of the bottom waters and substrates has prevented normal development of benthic organisms. The scarce number of present species have been considered by many authors, such as cited by Koutsoukos et al. (Reference Koutsoukos, Leary and Hart1990), as oxygen deficiency tolerant forms. Finally, the frequent pyritization of tests and shells as well as the presence of pyrite is an additional indication of poor oxygenation (Baudin et al. Reference Baudin, Moullade and Tronchetti2008), because this mineral requires an anoxic environment for its formation. It is also necessary to consider the presence of gypsum throughout the studied section, where it never occurs in the form of continuous layers, instead being mixed within the levels. This mineral substance could probably be regarded as a secondary element, resulting from the transformation of pyrite. Thus, the depositional setting seems to correspond to a low-energy, relatively deep environment, which can be located around the middle to the external ramp (Fig. 10b).

6.b. Lower Cenomanian to middle Cenomanian

Compared to the previous interval, the middle–upper Cenomanian is therefore marked by a dominance of planktonic foraminifera, mainly globular forms and by a more developed benthic microfauna, but the specific diversity is still relatively low. The most common species include, in particular, some agglutinated taxa, often dominant (Textularia sp., Thomasinella punica), and small calcareous forms (Gavelinella sp.). On the whole, the concerned levels are characterized by a renewal and a greater diversification of benthic microfauna. Oyster levels are sometimes numerous and densely packed. The presented micro-faunistic associations always indicate a deep and calm environment, of external platform type, although a change in the environment is noticeable. Indeed, higher occurrence and diversity of benthic organisms suggest either a slight decrease in depositional depth or an improvement in bottom oxygenation conditions. Both hypotheses are also likely; in addition, a total absence of pyrite is noticed.

Furthermore, near the upper part of the lower Cenomanian succession of the Fahdene Formation and in a stratigraphic position correlative to the topmost part of the Mantelliceras dixoni Zone, there is a level where no ammonites have been found (Fig. 5, highlighted in blue). This part of the Fahdene Formation is also marked by a distinct break (the Trough) in sedimentation, which can be related to a marked sea-level fall locally recorded by a thin bed of beige-coloured limestone topped by an oyster and bioturbated surface (Figs 4c, 10c). It is succeeded by a transgressive parasequence of brown clayey marls with the ammonite Cunningtoniceras inerme. This allows a possible correlation with the Conlinoceras tarrantense fauna of the Thatcher Limestone of Texas, which is characterized by orange-brown clays with carbonate concretions containing this index species (Hancock, Reference Hancock2003). In the Anglo-Parisian basin, Robaszynski et al. (Reference Robaszynski, Caron, Amedro, Dupuis, Hardenbol, Gonzales Donoso, Llnares and Gartner1994) also recognized ‘the presence of an important fall in sea-level represented on the basin margins by a marked break at the lower-middle Cenomanian boundary’ and they correlated this event through the Mantelliceras dixoni Zone, which is quite well matched with our study area.

6.c. Upper Cenomanian

The upper part of the Cenomanian succession of the Nouader site carries the imprint of the Cenomanian–Turonian crisis. The interest in this limit is due to the fact that it is characterized by the occurrence of a major biological crisis, caused by an anoxia of the bottom waters, which is at the origin of the deposit of an important quantity of organic carbon, and appears in the form of ‘black shale’ layers (Schlanger & Jenkyns, Reference Schlanger and Jenkyns1976).

It is characterized by marly limestone facies known as black shales, the famous Bahloul levels described in many places (e.g. Tunisia: Burollet et al. Reference Burollet, Dumestre, Keppel and Salvador1952–4; Burollet, Reference Burollet1956; Robaszynski et al. Reference Robaszynski, Caron, Amédro, Dupuis, Hardenbol, Gonzales-Donoso, Llnares and Gartner1993, Reference Robaszynski, Caron, Amedro, Dupuis, Hardenbol, Gonzales Donoso, Llnares and Gartner1994, Reference Robaszynski, Faouzi Zagrarni, Caron and Amedro2010; Caron et al. Reference Caron, Dall’agnolo, Accarie, Barrera, Kauffman, Amedro and Robaszynski2006; Kennedy & Gale, Reference Kennedy and Gale2015; NE Algeria: Naili et al. Reference Naili, Belhaj, Robaszynski and Caron1995; Chikhi-Aouimeur, Reference Chikhi-Aouimeur2010; Ruault-Djerrab et al. Reference Ruault-Djerrab, Ferré and Kechid-Benkherouf2012, Reference Ruault-Djerrab, Kechid-Benkherouf and Djerrab2014; K Chaabane, unpub. PhD thesis, Université Badji Mokhtar, 2015; Western Algeria: Benyoucef et al. Reference Benyoucef, Meister, Bensalah and Malti2012, Reference Benyoucef, Meister, Mebarki, Läng, Adaci, Cavin, Malti, Zaoui, Cherif and Bensalah2016). These black-colour-appearance, laminated levels are rich in organic carbon (TOC value c. 4.5%). Another characteristic of this level is the dominance of globular planktonic foraminifera (Hedbergella sp., Heterohelix sp., Heterohelix globulosa, Globigerinelloides sp., Whiteinella sp., W. baltica, W. brotonensis, W. praehelvetica and W. archaeocretacea). The diversity of benthic species is globally low, including such as Nodosaridae, Textularia sp. and Lenticulina rotulata, whereas the oyster-rich levels are absent. Some dispersion of filaments with the presence of glauconite was evident, especially in sample 117. In addition, the phenomenon of ferruginization is very important. Tolerant forms of minimum oxygen (e.g. Heterohelix) indicate relative anoxia corresponding to a minimum oxygen zone (the beginning of the transgressive interval from here) developed during the late Cenomanian to early Turonian, according to the work of Keller & Pardo (Reference Keller and Pardo2004). All these characteristics provide information about a circalittoral environment of external platform type (Fig. 10d).

6.d. Lower Turonian

This interval is marked by the abundance of the genera Whiteinella and Heterohelix, especially the species W. baltica and H. globulosa. Also, the microfaunistic associations with Whiteinella archaeocretacea, W. baltica, W. brittonensis, Heterohelix moremani, H. globulosa, Hedbergella simplex, H. delrioensis and H. planispira, allow the attribution of a Turonian age to this setting. The appearance of elongated test forms (endofauna) represented by Nodosaria reflects a decrease in the oxygen level which would explain a reduction observed on the planktonic population. In addition, the appearance of keeled forms (Dicarinella) reflects a relatively deep environment (Hart & Bailey, Reference Hart and Bailey1980). All these data evoke an external platform-type repository environment (Fig. 10e).

7. Conclusions

A study has been made of the lower–upper Cenomanian boundaries interval of the Nouader site in the Aures Basin, using the association of ammonites and foraminifera. It produced results that allow a good comprehension of the sedimentary interval, chronology and environmental conditions of this north Tethyan range.

The description of 120 samples allowed us to divide the study section into two formations (Fahdene and Bahloul), and one Member (Annaba), whose facies are generally dominated by dark marls at the base and calcareous to the top.

Biostratigraphically, the ammonite fauna allows recognition of six zones dating four sub-stages and yet calibrated with foraminiferan biozones. Respectively: (1) the lower Cenomanian Mantelliceras mantelli Zone, (2) the upper lower Cenomanian Mantelliceras dixoni Zone, (3) the lower middle Cenomanian Cunningtoniceras inerme Zone, (4) the Acanthoceras rhotomagense Zone and its subzones of Turrilites costatus and Turrilites acutus, (5) the upper middle Cenomanian Acanthoceras amphibolum Zone, (6) the lower upper Cenomanian Eucalycoceras pentagonum? Zone and finally the lower Turonian Pseudaspidoceras flexuosum Zone which is not limited to the top in this study due to the inaccessibility of the local topography. The middle and the upper part of the upper Cenomanian are not recognized in the section due to the apparent absence of ammonite species.

Five planktonic foraminifera biozones were identified: (1) Thalmanninella brotzeni Zone, (2) Thalmanninella reicheli Zone, (3) Rotalipora cushmani Zone, (4) Whiteinella archaeocretacea Zone, and (5) Helvetoglobotruncana helvetica Zone.

An interregional comparison with the planktonic foraminifera and ammonite biozones of the Boreal and Tethyan Realms shows numerous affinities between the two domains: five planktonic foraminifera and seven ammonite biozones are common.

Based on species with North American affinities (Pseudaspidoceras flexuosum and Acanthoceras amphibolum), excellent guides for intercontinental correlation could be constituted.

During the Cenomanian, the depositional depth still corresponds to a calm and relatively deep environment, which can be located around the middle to outer platform. A regression period occurs at the end of the early Cenomanian and beginning of the middle Cenomanian, being recorded by a distinct break in sedimentation shown by a thin limestone topped by an oyster-studded surface, probably equivalent to the Thatcher Limestone of Texas, followed by transgressive clayey brown marls with the ammonite Cunningtoniceras inerme. This break (the Trough) represents a lower sea-level in the middle of the Cenomanian Stage known in several areas all over the world such as: NW Europe, Crimea and Kazakhstan, Pueblo in Colorado, South Dakota and Texas (Austin and Fort Worth). During the Turonian, the deepening is accentuated, tending towards the external platform. This deepening has led to the installation of a relative (minimum oxygen) anoxia in the depositional environment, which is comparable to those known elsewhere along the pre-Atlantic basins at this time.

Author ORCIDs

Aida Bensekhria, 0000-0002-7030-8890

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the anonymous reviewers for constructive and useful comments that helped to improve the manuscript.

Repositories of specimens

UB2: University of Batna 2, Batna, Algeria (First Author collections).

Appendix

All identified microfossils are listed in alphabetical order, with foremost ammonites, planktonic foraminifera and benthic foraminifera. The names used comply with the rules of the International Code of Zoological Nomenclature (ICZN).

Ammonites

Acanthoceras cf. rhotomagense (Brongniart, Reference Brongniart, Cuvier and Brongniart1822)

Acanthoceras amphibolum (Morrow, 1935)

Calycoceras (Proeucalycoceras) Thomel, Reference Thomel1972

Cunningtoniceras inerme (Pervinquière, Reference Pervinquière1907)

Eucalycoceras pentagonum (Jukes-Browne, 1896)

Mantelliceras cf. mantelli (Sowerby, Reference Sowerby1812–22, pls. 45–78 [1814])

Mantelliceras dixoni (Spath, Reference Spath1926a, b)

Mantelliceras saxbii (Sharpe, 1857)

Pseudaspidoceras flexuosum (Powell, 1963)

Sharpeiceras laticlavium (Sharpe, 1855)

Turrilites acutus Passy, 1832

Turrilites costatus Lamark, 1801

Planktonic foraminifera

Dicarinella hagni (Scheibnerova, 1962)

Dicarinella imbricata (Mornod, 1949)

Globigerinelloides sp.

Guembelitria cenomana (Keller, 1935)

Hedbergella delrioensis (Carsey, 1926)

Hedbergella planispira (Tappan, 1940)

Hedbergella simplex (Morrow, 1934)

Hedbergella sp.

Helvetoglobotruncana helvetica (Bolli, 1945)

Heterohelix globulosa (Ehrenberg, 1840)

Heterohelix moremani (Cushman, 1938)

Heterohelix sp.

Praeglobotruncana delrioensis (Plummer, 1931)

Praeglobotruncana gibba (Klaus, 1960)

Praeblobotruncana stephani (Gandolfi, 1942)

Rotalipora cushmani (Morrow, 1934)

Rotalipora montsalvensis (Mornod, 1949)

Thalmanninella appenninica (Renz, 1936)

Thalmanninella balernaensis (Gandolfi, 1957)

Thalmanninella globotruncanoides (Sigal, 1948)

Thalmanninella greenhornensis (Morrow, 1934)

Thalmanninella reicheli (Mornod, 1950)

Whiteinella sp.

Whiteinella aprica (Loeblich & Tappan, 1961)

Whiteinella archaeocretacea (Pessagno, 1967)

Whiteinella baltica (Douglas & Rankin, 1969)

Whiteinella brittonensis (Loeblich & Tappan, 1961)

Whiteinella paradubia (Sigal, 1952)

Whiteinella praehelvetica (Trujillo, 1960)

Benthic foraminifera

Ammobaculites sp.

Cuneolina pavonia d’Orbigny, 1846

Dorothia cf. trochus (d’Orbigny, 1840)

Dorothia oxicona (Reuss, 1860)

Dorothia sp.

Flabelammina alexanderi Cushman, 1928

Gavelinella sp.

Haplphragmoides sp.

Lenticulina cf. rotulata (Lamarck, Reference Lamarck1801/1804)

Lenticulina sp.

Lutuolids

Miliolids

Nezzazata simplex Omara, 1956

Nodosaria sp.

Pseudolituonella reicheli Marie, 1954

Textularia cf. chapmani (Lalicker, 1935)

Textularia sp.

Textulariids

Thomasinella punica (Schlumberger, 1893)

Trochamminoides sp.