I

A comparative blindness affects much of the literature on the success and decline of pawn banks. In most developed and developing countries the multiplication of pawnbroking institutions has been associated with the major social and economic changes of the modern age, such as urbanization, the deregulation of the labor market, the difficulty of lower income groups to make ends meet, and the lack of suitable financial intermediaries. Low, irregular wages and job insecurity generated the need for schemes to combat such contingencies and to cushion financial shocks. Pawn banks emerged as the most logical, adaptable and widespread microfinance venue to bridge cash flow shortfalls. Most scholars would share Raymond's view that pawnbrokers ‘helped shape the quality of the material life of the urban working class’ in modern times (Raymond Reference Raymond1978, p. 15).

Current research has clearly documented the increase of pawn banks – both private and public – across Western Europe and the Americas through the nineteenth century. Poverty and the insecurity of the laboring classes caused a growing demand for short-term credit and fueled the rapid expansion of the so-called fringe-banking sector (Tebbutt Reference Tebbutt1983; Caskey Reference Caskey1994; O'Connell Reference O'connell2009; Woloson 2007; Murhem Reference Murhem2016). The working poor regularly looked for short-term loans to buy necessities. Their poverty was not permanent but periodic, not absolute but situational. Life cycles and economic cycles could throw families into temporary crisis and distress. Pawn houses provided cash quickly and discreetly. Recognizing the crucial social function pawn banks played at the lower end of the social spectrum, authorities encouraged their development, and strove to regulate lending procedures in order to protect customers from exploitative practices.

The historical approach and narrative are strikingly different in Italy, where pawn banks were not an invention linked to modern economic development. In fact, Italian commercial centers pioneered microfinance initiatives from the late Middle Ages (Todeschini Reference Todeschini2016). The introduction of church-sanctioned civic pawn banks called Monti di pietà (MdP) in the Renaissance proved a powerful institutional innovation, designed to give credit a social function (Cipolla Reference Cipolla1993, p. 125). Across the peninsula the local MdP became the springboard for civic efforts to provide help through credit on fair terms (Muzzarelli Reference Muzzarelli2001; Avallone Reference Avallone2007). Pictorial representations combined holy heaps of coins and the redemptive image of the dead Christ as the Imago pietatis, underscoring the concept that Monti were compassionate charitable banks (Puglisi and Barcham Reference Puglisi and Barcham2008). MdP boomed in numbers, and their business activities grew in step. Italian historiography has devoted a wealth of scholarship to the topic, but most research has focused on early periods and little effort has been made to chart later developments (Montanari Reference Montanari2001; Barile Reference Barile2012).Footnote 1

On closer examination, pawn banks must be understood through both their early modern roots and their modern developments. On the one hand, the spreading of pawn businesses is associated with attempts to alleviate precarious conditions of poor households, a basic problem that was common in urban areas well before the industrial age and continues to the present day. On the other hand, the pawn business is versatile, adaptable to a variety of social and economic settings, and performs well in different contexts precisely because it is accessible to ‘unbankable’ people.

This article examines why the MdP lost ground and prestige in Italy during the nineteenth century, and to what extent they continued nevertheless to play an important social and economic function. Several factors had an adverse impact: changes in legislation deprived them of the privileged status they had long enjoyed; their financial activities were curtailed and the overall credit environment became less favorable due to the competition of new institutions – savings banks and mutual banks – designed to offer banking services to lower-income people. The difficult relationship between church and state after Italian unification in 1861 also played a role and fed the distrust of the new liberal elite towards establishments that had obvious Catholic roots. Yet, despite these impediments, Italian Monti displayed a remarkable resilience. Their ties to local communities ran deep, and their credit services were often the only ones available to poor households.

We open this article with a survey of the development of MdP in Italy and their later slow spread to other western European countries. We then consider the stormy cultural and political environment MdP faced in the nineteenth century. The last section analyzes data provided by an 1896 national survey – Statistica dei Monti di pietà – carried out under the auspices of the Ministero di Agricoltura, Industria e Commercio (MAIC). The survey, taken during a difficult period of economic crisis, social suffering and mounting unrest, documents MdP resilience, highlights their social functions and reveals the contradiction of social and credit policies in liberal Italy.

II

In the period just after the unification of Italy in 1861, civic pawn banks outnumbered other credit agencies by a ratio of four to one. Yet they were nothing new, and their continuation into the modern age was hardly appreciated as an asset by most thinkers and politicians. By contrast, MdP were not associated with social and economic progress but were seen instead as symbols of the backwardness of the country. As a result, MdP were treated in public policy as obsolete facilities that hampered the new kingdom's efforts to modernize its credit sector.

MdP's origins reached back to the fifteenth century. They were promoted by a cohort of determined Observant Franciscan preachers as a way to put money within reach of the working poor, protecting them from usury, i.e. the high interest rates charged by private, mostly Jewish, moneylenders (Todeschini Reference Todeschini2009). Religious overtones ran high and anti-usury rhetoric could be vicious and frankly anti-semitic. Yet as MdP emerged and expanded from the 1460s, they marked a truly innovative departure from earlier negative views which saw lending as a violation of Catholic doctrine (Muzzarelli Reference Muzzarelli2001). Credit began to be seen as an anti-poverty tool, and charging a small rate of interest in order to maintain a fundamentally charitable operation was deemed acceptable. This had a lasting impact on western economic thought.

The MdP organized themselves according to a standardized set of statutes and became the benchmark of socially responsible consumer credit (van der Wee Reference Van Der Wee1993, p. 184). In roughly half a century – the first Monte opened in Perugia in 1462 – over 130 such institutions sprang up in towns across central and northern Italy (Meneghin 1986). Formal papal sanction allowed the MdP to develop under the protection of the church.Footnote 2 By the mid eighteenth century there were over 700 civic pawn operations across the peninsula (Table 1).

Table 1. Main Italian Monti di pietà

MdP were highly successful institutions. They were created as microcredit agencies to provide short-term loans to poor workers,Footnote 3 but they became key financial players in what has been labeled a ‘moral economy’ (Fontaine Reference Fontaine2008). In most cities the MdP faced little or no competition, and enjoyed a near monopoly status. The imposing facilities for administration and the storage of pawns that they acquired and built in scores of cities speak volumes about their business success.Footnote 4 They attracted large volumes of capital, and expanded the range of financial services they offered to include interest-bearing investment tools. Adding profitable mainstream credit activities did not hurt their social role. In fact, they were allowed to lower fees, with the result that credit costs dropped well below market rates for the most vulnerable clients (Silvano Reference Silvano2005; Ferlito Reference Ferlito2009; Carboni Reference Carboni2014).Footnote 5

Despite swift progress across the peninsula, Monti did not spread rapidly north of the Alps. Religious reasons played a role in some areas, as countries that embraced Protestantism during the sixteenth century were reluctant to facilitate an institution so closely identified with the Catholic Church. In Catholic regions institutions closely mirroring the MdP model were indeed established, yet progress was not rapid. Seventeen agencies opened across Flanders in the early seventeenth century (Marec Reference Marec1983, p. 20; Fontaine Reference Fontaine2008, pp. 169–71). In Spain and in France, the MdP initiated successful business histories only in the eighteenth century: Marseille (1696), Madrid (1702), Barcelona (1751), Paris (1777) and Bordeaux (1801). In all these areas the process of establishing local agencies patterned on the MdP was clearly connected to economic development, urbanization, and the need to fight urban poverty by providing a measure of credit assistance to the needy (Lopez Yepes and Titos Martinez Reference Lopez Yepes and Titos Martinez1995; Carbonell Reference Carbonell-Esteller2012; Danieri Reference Danieri1991; Borderie Reference Borderie1999; Fontaine Reference Fontaine2008; Pastureau and Blancheton Reference Pastureau and Blancheton2014).

The case of French Monts-de-Piété is intriguing. While they made little headway under the ancien régime, they registered swift progress after the revolution. They benefited from Napoleon's 1804 provision, which set out to ‘moralize’ pawnbroking activities and granted them the monopoly of the trade.Footnote 6 Even though Italian Monti were plundered by French invading armies and were regarded by French authorities as tools of clerical oppression, the model was nonetheless imported, adapted and even introduced to other regions of continental Europe under French rule. During the first half of the nineteenth century the number of active MdP increased in France to 45 and transactions soared in relationship to the deregulation of the labor market. Marec has aptly labeled these ‘banque de pauvres’ as ‘barometer de la misère publique’ (Clap and Brihat Reference Clap and Brihat2010, p. 32; Marec Reference Marec1983, p. 57). In cities like Bordeaux and Paris that were rapidly industrializing and expanding, MdP provided resources to remedy working households’ precarious financial situation and played a vital role in lowering social tensions associated with deep economic changes. (Danieri Reference Danieri1991; Pastureau and Blancheton Reference Pastureau and Blancheton2014).

Only in Catholic Ireland did the Monti fail to put down durable roots. Eight such agencies were established in the 1830s and 1840s, but all ceased to operate in a few years. They faced particularly adverse conditions. The predominantly rural economic context of the island was hardly favorable, and they lacked resources to operate cheaply and effectively. In addition, they faced competition from private pawnshops, which dominated the pawnbroking business across the British Isles and which actively ‘combined to operate against them’ (Tebbutt Reference Tebbutt1983, p. 110; McLaughlin Reference Mclaughlin2013). Private pawnshops were common suppliers of working-class credit in Britain and the numbers of licensed private pawnbrokers increased steadily throughout the nineteenth century. (Minkes Reference Minkes1953; Tebbutt Reference Tebbutt1983; Finn Reference Finn2003).Footnote 7

Pawnshops were also common in other mainly Protestant countries, and their numbers increased alongside the demand of the new urban poor for short-term credit. To limit abuse, authorities in some countries intervened, promoting public establishments which closely mirrored the MdP. This was the case in the Low Countries, Germany, Sweden and even the United States. In the Low Countries, authorities set up Banken van Leening (licensed pawn banks) to replace private agencies. In the United States model philanthropic pawn houses included the Collateral Loan Company set up in Boston in 1859 and the Provident Loan Society established in New York in 1894 (Caskey Reference Caskey1994; Furher Reference Furher2001; McCants Reference Mccants2007; Woloson Reference Woloson2012; Deneweth, Gelderblom and Jonker Reference Deneweth, Gelderblom and Jonker2014; Murhem Reference Murhem2016).

III

While pawn banks multiplied across Europe to meet the need of the new urban poor, the well-established Italian Monti led an increasingly troubled existence. This was an odd development in a country where the credit system was rudimentary, and social and financial exclusion was very high. Access to credit to survive lean periods should have been a priority: in 1861 about 40 percent of the population was close to or below the poverty line, and households devoted two-thirds of their income to buying food (Vecchi Reference Vecchi2011, p. 295).

Two sets of events early in the nineteenth century had long-term negative consequences. Many religious institutions suffered heavy financial damage at the hands of invading French armies in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. The so-called ‘spoliazione napoleonica’ referred to the merciless plunder of money and pledges from the vaults and safes of Monti across the peninsula. The loss of assets was so sudden and heavy that this ‘Napoleonic plundering’ was truly a turning point: numerous agencies went out of business, at least temporarily, and the MdP's ability to operate was severely curtailed for years to come (Varni Reference Varni1996). Financial losses were compounded by unfavorable legislative provisions which weakened both Monti’s managerial independence and their ability to conduct business. In 1807 officials of the French regime stripped Monti of their banking qualifications, demoted them to the status of charitable institutions, and subordinated them to the authority of new local administrative units called the Congregazioni di carità (Congregations of Charity). Although in several regions these provisions were reversed during the Restoration of the 1820s, many MdP agencies had difficulty recovering their public reputation as banking institutions, while smaller Monti lacked funds to resume lending.

Competition within the credit sector did not help either. In one city after another, Monti lost their privileged position in the credit market, and even their monopoly of the pawn trade was threatened. Reeling from these legislative and financial difficulties, Monti faced new challenges from private pawnshops. The phenomenon is well documented in the major cities of northern Italy. In Bologna, for instance, the papal Legate explained that from past disorders

a horde of wicked usurers arose to offer a false and pernicious assistance to the poor; and in those days the laws against usury were silenced and morals were lax, so that it was not difficult to practice such base trade. (Fornasari Reference Fornasari1998, pp. 25–6)

A greater challenge to the MdP's standing in the credit market came from new alternative financial institutions: savings banks (Casse di risparmio) and cooperative credit societies (Banche popolari and Casse rurali). These were financial intermediaries with the specific social mission to help those who were ‘unbanked’ (wage workers, farmers and so on) to overcome economic obstacles and to reduce poverty.

Savings banks were philanthropic credit entities that drew their inspiration from German institutions and enjoyed the favor of liberal-leaning urban elites. In Italy such agencies first appeared in 1822, and quickly spread across the peninsula. In roughly half a century the number of savings banks soared to 249 (De Rosa Reference De Rosa2003). While Monti were increasingly seen as outdated entities, contemporaries viewed savings banks as a new and modern remedy to poverty through self-discipline and thriftiness (Balzani Reference Balzani2000).

Casse and Monti were in fact complementary civic institutions. They had different objectives – MdP catered to consumption needs while Casse promoted savings – but they shared similar social aims and vocations or purpose. There was initially a fair degree of cooperation in several cities, and Monti played an active role in promoting Casse or later merged with them. In addition, savings banks could supply vital funds to support MdP lending activities.Footnote 8

Later in the century, fresh competition came from another breed of social banks which also went back to German examples: people's banks (Banche popolari) and credit unions (Casse rurali). Although different in membership, these new banking intermediaries were based on the principle of cooperative credit. They were mutually owned, pooled a community's deposits and lent them out to the same community. Their motto was ‘banks of the people, by the people, and for the people’ (Baradaran Reference Baradaran2015, 65). Cooperative credit societies rapidly spread throughout Italy, and greatly contributed to bringing money where it was more costly and difficult to obtain.

These new credit intermediaries undoubtedly played an important role in fostering development and in expanding the number of ‘bankable’ people. Yet they could do little to help the sort of people who flocked to MdP. These were the working poor who were unable to save, and who needed credit or financial aid to face emergencies, or to bridge periodic gaps between earnings and consumption.

The political climate and legal environment were not advantageous after unification. The Papacy had opposed unification, and threatened excommunication of those Catholics who played a role in the new secular regime. These political circumstances distanced Catholics from active involvement in the new kingdom and exacerbated conflict between liberal and catholic forces. The MdP's traditional association with the church and dispossessed authorities made them suspect. The stigma nurtured distrust, and resulted in fresh waves of hostile provisions that limited their ability to keep operating as credit providers. Monti were corraled as charitable agencies and subject to the 1862 law disciplining charities. While in other European societies MdP were seen as useful social credit institutions, politicians and influential intellectuals in Italy found fault with them and expressed this in sometimes pungent terms. Luigi Luzzatti, an economist of great personal prestige and a vocal promoter of cooperative banks, regarded MdP not only as obsolete but as socially nefarious establishments designed to prey on the poor. According to Luzzatti, Monti ‘were compassionate just in name’ (di pietoso non avevano che il nome) (Luzzatti Reference Luzzatti1952, p. 421). In an age of prevailing self-help ideology, other economists were equally dismissive: Monti belonged ‘to the past, did not conform to the tenets of saving and providence modern economics promoted, and were more a liability than an asset to the poor’.Footnote 9 Worse than that, MdP could even be seen as vehicles of wickedness. They were suspected of fencing stolen goods and accused of fostering improvidence, since they served those who lacked the discipline to work or the foresight to save and so failed to build a financial buffer for a rainy day. In this way, the very ethical foundations that MdP rested upon were turned upside down. Vocal critics claimed that Monti were not only outdated relics of a religious past, but evil agencies that encouraged vice instead of fighting it.

The situation came to a head in the final decade of the century. New credit provisions in 1888 dictated a business separation between savings banks and MdP, barring Monti from taking deposit accounts, which were a vital source of liquidity (De Rosa Reference De Rosa2003). Crispi's 1890 law, disciplining charitable institutions, made a difficult situation worse (Cherubini Reference Cherubini1991; Quine Reference Quine2002). Legislation forced MdP to operate under stricter administrative and budgetary rules, further impairing their ability to conduct business. Faced with concerted opposition, administrators of leading Italian Monti responded by establishing a society (Associazione Nazionale dei Monti) to promote their business and to lobby lawmakers. The effort paid off: a new law in 1898 put an end to the systematic legislative curtailing of Monti’s activities. It acknowledged pawn banks’ unique role in offering financial services tailored to the need of low-income clients, and finally provided a sounder institutional framework, restoring the MdP to their proper place in the credit market (Soldini Reference Soldini1900).

IV

The 1898 law was preceded by a national survey, the Statistica dei Monti di pietà, carried out under the auspices of the Ministero di Agricoltura, Industria e Commercio (MAIC), which steered the legislative process. The survey aimed to chart the number, location, assets and overall range of MdP's activities.Footnote 10 Most institutions had operated for centuries (see Table 1), and they supplied data that were subsequently arranged along provincial and regional lines. The survey provides very valuable information about territorial distribution, and the social and economic importance of Monti at the end of the nineteenth century in a country that was torn between backwardness and development.

The survey was taken at a time of turmoil and mounting unrest. In addition to a severe economic slump, Italy faced a dramatic banking crisis. The bankruptcy in 1893 of the Banca Romana, one of the six note-issuing national banks, and the sudden liquidation of the main commercial banks brought the whole credit system to the verge of collapse, prompting drastic reforms to restore public confidence. In the same years the country was shaken from north to south by a wave of bitter confrontations, strikes and uprisings that were triggered by the rising prices of basic food staples, such as bread. This became known as the ‘revolt of the stomach’ (protesta dello stomaco). Massive protests and riots turned Milan, already Italy's leading financial and manufacturing center, into the heart of the revolt, and were brutally repressed by army units (Colajanni Reference Colajanni1898). This late-century crisis underlined both the plight of rural poor and the rapid growth of a new cohort of poor urban industrial laborers.

Pawn houses traditionally do well in economic downturns. Economic hardships and dramatic and widespread social discontent may have played a role in inducing lawgivers to review the approach to emergency credit. It certainly alerted them to the need to get better and more current information. Political and cultural changes within the Catholic camp provided further encouragement. Catholics slowly returned to active political engagement after the Holy See issued the bull Non expedit in 1868.Footnote 11 Moreover, the church took a new progressive turn when Pope Leo XIII issued the encyclical Rerum Novarum in 1891, and this was reinforced by the active role of new Catholic organizations – such as the Opera dei Congressi – in supporting economic and social activities from below.

Despite several decades of troubled existence, neglect and erratic legislative measures, Italy's MdP were remarkably numerous: there were 12 times as many as in France. In 1896 there were 556 active agencies, one for every 56,277 inhabitants (Table 3). MdP made up about one-third of the country's credit network. They outnumbered savings banks by a ratio of 2.5 to one, and they constituted roughly two-thirds of the fast-growing segment of new cooperative banks, the banche popolari (Table 2).

Table 2. The Italian banking system, 1861–1900

Geographical distribution mirrored the urban landscape. In the industrially and commercially advanced regions of northern Italy there were 196 active Monti, while 139 agencies operated in central Italy and 221 in the southern regions and the two islands of Sicily and Sardinia. With the notable exception of Sardinia – which had only one agency in the capital of Cagliari – the distribution of MdP was fairly even across the country.Footnote 12 The highest density was in the central regions of Umbria (one agency for every 23,359 people) and Marche (one agency for every 13,559 people), which also constituted the Renaissance cradle of the institution. In the mainly rural continental south, the density of Monti slightly exceeded the national average (one agency for every 52,519 people). In the more prosperous northwestern sector (Liguria, Piedmont and Lombardy) the ratio agency/population was considerably lower: there was a Monte for every 83,843 inhabitants, with a density nearly 50 percent below the national average.

At first sight, geographical distribution appears consistent with the mainstream narrative: Monti were credit relics of a bygone age and so it could be expected that their presence would be greater in the economically less-advanced regions of central and southern Italy. In other words, the MdP thrived in traditional pre-modern economic contexts and hence were more numerous and stronger in backward areas, where the tempo of economic change lagged behind, traditional credit practices prevailed and competition was weaker.

Size, distribution of assets and lending activities tell a different story. In northern Italy, Monti were fewer in number, but they were larger, more sound financially and handled more transactions. Across the country Monti employed a total of 3,059 people, giving an average of 5.5 employees for each agency. Yet MdP operating in northwesern Italy had larger staffs. In Lombardy, agencies employed 6.8 clerks on average, in Piedmont 5.8, in Liguria17.8, in Veneto 9.1 and in Emilia 6. In the rest of the country only Tuscany (14.8) and Sicily (6.9) employed numbers per agency that put them above the national average. The tiny agencies active in Umbria employed just 3.3 people, in Marche 2.2, in Calabria 4 and in Basilicata 2.2.

MdP patrimonial assets were closely tied to the core business of pawn lending. Pledges made up over 90 percent of assets (46.4 percent – 78.4 million), followed by other credit activities (40.8 percent – 69 millions) and cash (3.4 percent – 5.7 million). Real estate constituted only 8.75 percent (14.8 million). Available resources were not negligible (169 million lire), but they could hardly match that of their competitors: in 1896, MdP assets totaled only about one-tenth those of savings banks.

Regional distribution by asset size was also quite uneven (Table 4). Nearly two- thirds of assets were claimed by MdP operating in northern Italy (35 percent). In terms of per capita assets, northern MdP were three times wealthier than southern institutions. Everywhere there was a stark contrast between a few well-endowed powerful metropolitan agencies and scores of small and weak establishments. The vast majority of agencies were tiny and short of capital. Their assets were often so modest that their operational viability was constantly at stake. Indeed, 58 southern agencies were so undercapitalized that they had to borrow from others in order to keep lending.

Assets were concentrated in few strong hands. Just 34 agencies (6.1 percent) claimed 80 percent of assets (Table 5). Nearly two-thirds (22) of these agencies were located in the northern regions; just one-third (12) operated in the rest of country (6 in central Italy and 6 in the southern regions). Not surprisingly, the five largest institutions operated in the main metropolitan areas (Milan, Turin, Naples, Rome and Genoa) and claimed over 56 percent of assets.

The survey devoted close attention to MdP credit activities. Out of a total of 556 agencies, 448 (87 percent) carried out only pawn loan operations. Lending against the collateral of pledges involved over 6.5 million transactions and mobilized nearly 104 million lire (about 61.5 percent of assets). Again, sharp regional differences emerge: a little over half of pawn-handling operations (50.6 percent) and almost half of loans (48 percent) were handled by agencies operating in northern Italy (35 percent) (Table 6).

Table 6. Main credit activities of Monti di pietà

a Seven Monti did not provide information.

Source: MAIC (1899).

Neither transactions nor loans were evenly distributed. The national average (20 percent) – i.e. a pawn transaction for every five inhabitants of the kingdom – was the outcome of very different levels of activity, ranging from 97.6 percent in Lazio to 0.4 percent in Basilicata (Table 6). In northern and central regions, the number of operations tended to be higher. Transactions were above the national average in five regions out of nine (Liguria 36.5 percent, Veneto 43 percent, Emilia-Romagna 25.9 percent, Tuscany 38.1 percent, Lazio 97.6 percent). The opposite applied in the south, where all regions, with the exception of Campania (20.8 percent), had a number of transactions below the national average. In four regions (Abruzzi, Puglia, Basilicata and Calabria) the number of pawn operations was very low, and involved less than 3 percent of the population.

The pawn business was much brisker in the main metropolitan areas, where the working poor, the traditional customers of MdP, were more numerous. The number of transactions turned out to be higher than the residing population in 24 out of 33 cities (Table 5). In Venice, Verona, Padua, Vicenza, Udine, Ferrara, Florence, Pisa and Livorno, the number of loans made annually was over twice the number of inhabitants, while in Genoa, Treviso and Bologna it fell just short of that. It must be noted that in expanding metropolitan areas (Turin, Milan, Genoa, Bologna and Rome), MdP opened new branches in low-income neighborhoods to provide easier access to perspective customers. This confirms the view that for many working-class people, going to the pawn bank was a regular routine for survival in lean periods.

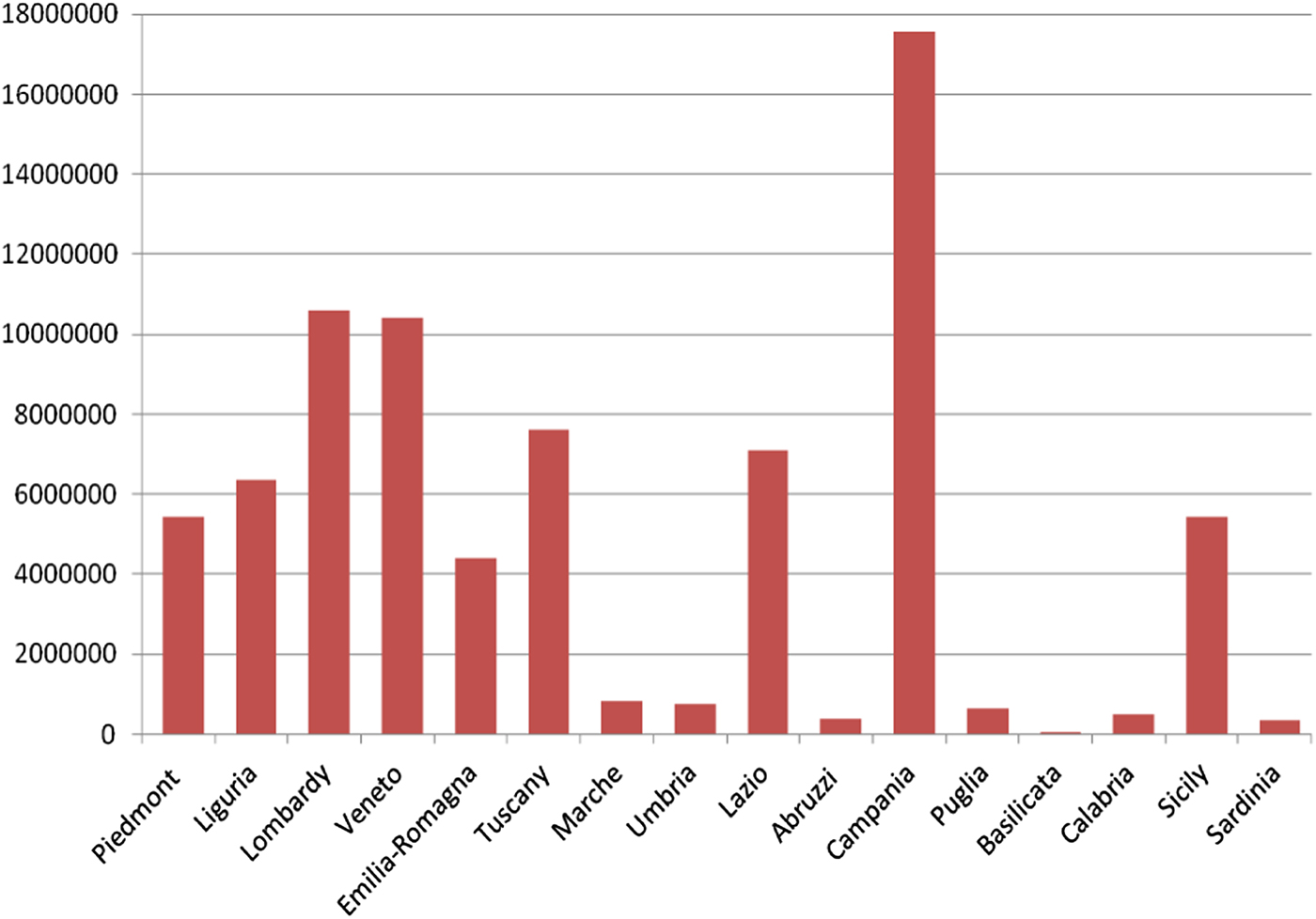

Substantial sums – over 5 million lire – were lent by agencies located in the Po valley, in the central regions of Tuscany and Lazio, and in the southern regions of Campania and Sicily. In absolute terms, the amount of money lent was higher in Campania (over 23 million lire) and Lazio (15.2 million lire) (Table 6 and Figure 1). However, it must be noted that in the latter regions data are heavily influenced by the overwhelming presence of the metropolitan Monti of Naples and Rome. The Monte of Naples handled over two-thirds of pawn loans in Campania, while Rome's accounted for 42.8 percent of that of Lazio. Together they accounted for about one-fourth of pawn lending nationwide.

Figure 1. Pawn loans by region

The branches located in Liguria, Tuscany, Lazio, Campania and Sardinia conducted the largest number of per capita operations.Footnote 13 The leading agencies in terms of loans (over half a million lire) are listed in Table 5. Veneto and Tuscany top the list with four and five Monti respectively. In most other regions just one metropolitan establishment dominated transactions.

Dividing up Monti according to the size of transactions that were carried out, we end up with a pyramid with a wide base of tiny agencies at the bottom – mostly located in southern and central Italy – and at the top a handful of large metropolitan agencies. The bulk of Italian MdP (300) operated in small poor rural communities and handled petty loans below the 10,000 lire threshold per year. About one-third of pawn agencies (183) operated in small towns and handed out annual loans up to 100,000 lire. Just 73 agencies (13.1 percent) mobilized amounts greater than 100,000 lire. Among these leading Monti a group of only 13 metropolitan establishments were able to lend more than one million lire per year (Table 7).

Table 7. Class of Monti di pietà according to loans handled (lire)

a The first class includes agencies that did not file in any report.

Source: MAIC (1899).

The 1896 survey charts in detail MdP lending activities: how many lent money at interest, and how many granted interest-free loans; the amount of money that could be borrowed, and for how long; how much was charged, the minimum and maximum value of accepted pawns, and the number of pawns that were stored and reclaimed on an annual basis. A large majority of agencies (over 83 percent) charged for their services, while only 92 facilities were able to grant interest-free loans. Most of the latter were tiny agencies, operating in rural communities in Lombardy (20 out of 50) and Emilia-Romagna (26 out of 51). They acted as charitable agencies and social concerns took precedence over economic considerations. Certainly interest rates overall were extremely low, ranging from a minimum annualized rate of 2 percent to a top rate of 10 percent.Footnote 14 Several agencies did not apply a fixed charge, but tailored interest rates to the loan and the borrower, i.e. the length of time and the sort of pawns that were pledged. Most MdP – two-thirds – charged between 5 percent (148) and 6 percent (228). Loans tended to cost more in densely populated but poor rural regions such as the Veneto, Campania and Sicily. Here the vast majority of institutions charged more than 6 percent.

The statutes of MdP placed limits on the sums that people could borrow. Loans were granted from a minimum of 3 months to a maximum of 48 months, but the majority of MdP (304) set the limit to one year. As might be expected, about 80 percent of agencies either set a very low minimum amount or none: 64 Monti had no minimum loan requirements and another 372 had a minimum requirement of one lira or less (equivalent to about half a day's pay).Footnote 15 About 90 percent of MdP placed ceilings on the maximum amount they could lend against collateral. Two-thirds of agencies (374) set a maximum amount of 100 lire (about two months’ salary) or less, over half (285) kept the limit below the 50 lire threshold.

One Italian in five had a pledge in storage. MdP granted an average loan of 16.45 lire per pawn, or 3.37 lire to each inhabitant of the kingdom. Generally, a high number of transactions translated to larger loans being handed out. In peripheral agencies, transactions were fewer and loans smaller. Table 5 suggests that it was metropolitan agencies that claimed the lion's share. Indeed, over 60 percent of loans were granted by 34 leading agencies. Just four metropolitan Monti (Naples, Milan, Rome and Genoa) accounted for more than one-third of loans granted through the kingdom. It is striking the high volume of lending performed by the Monte of Naples, which accounted for over two-thirds of total loan issuance in Campania. The average loan per pawn granted was also considerably higher at 27 lire (two-thirds higher than the national average of 16 lire). This hints at a higher number of transactions involving precious pawns and suggests that customers of the Monte in Naples included not just the urban poor, but a middling and perhaps even a more affluent clientele as well.Footnote 16

The survey does not provide data about the social or professional identity of MdP customers. However, the location of leading MdP and the average low value of loans indicates that most customers lived in cities and belonged to either poor or middling social groups. Data assembled in Table 8 suggest that agencies operating in northeastern, central and southern Italy supported mostly poorer and even destitute segments of the population. On average, they handed out loans between 7 lire (Marche) and 15 lire (Sicily).Footnote 17 Elsewhere agencies must also have served a better-off clientele, perhaps competing with mainstream banking. This was the case in the more developed northwestern regions of Liguria (25 lire on average) Piedmont and Lombardy (17 lire). In other regions – Basilicata (26 lire), Campania (35 lire) and Sardinia (37 lire) – larger loans may just mirror a lack of credit alternatives.

Table 8. Per capita GDP, emigration and Monti di pietà activities

a lire, 1896.

Sources: MAIC (1899); Felice (Reference Felice2015); Rosoli (Reference Rosoli1978).

Pawn lending followed peculiar regional patterns. Beyond low income and economic dislocation, there were a variety of factors contributing to different trends (Table 8). High MdP lending activity was associated with widespread poverty in Campania, Sicily and Veneto: here per capita income was lower and outward migration was high. Pawn transactions were also high in wealthier regions such as Lazio, Lombardy, Piedmont and Liguria. Yet they were largely carried out by metropolitan agencies which served the growing cohort of poor urban households. Finally, in some rural regions actual lending was remarkably low, despite a high level of poverty. In Abruzzi, Marche, Basilicata and Calabria the MdP were numerous, but they were so small and undercapitalized that their capacity to operate and to offer credit services could not match local need.

A noteworthy feature is the high rate of reimbursement (over 93 percent). The MdP not only performed a useful social function; they were economically effective as well. The ratio of sale of pawned items was very low: less than 7 percent over the 1894–6 period (Table 8). Despite being poor and vulnerable, most customers held on to their possessions, and chose to pay back their loan. They did so in similar ratios across the country: the sale of unclaimed pawned items ranged from less than 1 percent in Basilicata to a maximum of about 10 percent in Lazio.

Profits from standard pawn lending contributed about 55 percent to MdP earnings, but regional differences were considerable. Pawn operations contributed over 90 percent to earnings in Liguria and Campania, 85 percent in Lazio and Tuscany, 81 percent in Veneto, and 78 percent in Sicily. Their contribution was much lower in Piedmont (17 percent), in Lombardy (29 percent) and in Emilia-Romagna (39 percent). This seemingly modest performance can be explained by the fact that in these regions number of institutions operated which deployed a considerable share of their assets in other credit activities, from government bonds to mortgage loans. Large MdP such as those of Turin and Milan operated as ordinary credit agencies and pawn lending was no longer their main business. Indeed, they earned over two-thirds of their profit from standard banking services.

It must be stressed, however, that agencies providing other credit services in addition to pawn lending were not necessarily larger, more efficient or versatile. Half of the Monti in Basilicata (6 out of 12) and scores of small agencies in inner Campania, Abruzzi and Calabria granted personal loans as well as loans against promissory notes. In poor and remote rural towns across the country, MdP were often the only credit outlets. In addition, handling pawns of little value could be costly, and, in small communities, personal ties could easily make up for the lack of adequate collateral.

V

The 1896 survey provides a revealing and so far neglected picture of Italian Monti di pietà at the end of the nineteenth century. A few features deserve to be stressed. First, the single label of MdP encompassed agencies whose size, assets and operations varied widely. Urban and regional contexts played a crucial role. From early on, the MdP had been versatile credit agencies with deep roots in the local economy and they evolved accordingly. Second, a great operational gulf separated a handful of large metropolitan establishments from the rest. The metropolitan agencies held most assets, carried out most transactions and were able to provide a variety of credit services in addition to pawnbroking. Third, regardless of size, MdP continued to play an important social function as providers of small short-term emergency loans. They were extremely adaptable and served both a poor and middling clientele. Yet there is no question that most loans went to the new cohort of urban poor of the modern age. In fact, the most active establishments were not located in the more lethargic rural regions of central and southern Italy, but either in the more dynamic northwestern regions or in fast-growing metropolitan areas.

Despite suffering heavy financial losses and having to navigate difficult and at times stormy political waters, the Italian MdP displayed a remarkable resilience. They do not cut a poor figure in the late nineteenth-century European social-economic context. In overall number and density, they remained by far the largest network of public pawn banks in western Europe. Large metropolitan agencies were still able to mobilize resources that were hardly matched elsewhere in Europe and beyond. The one million pawns handled by the Monte in Rome in the mid 1890s does not compare unfavorably to the over 1.1 million handled by the MdP in Paris, when we consider that Rome had less than 500,000 inhabitants and Paris over 2.5 million (De Rita Reference De Rita2003). The Monte in Naples handled over five times the pawns of the Monte of Madrid (nearly 600,000 and about 120,000 respectively) despite the fact that the two cities were very close in population (Lopez Yepes and Titos Martinez Reference Lopez Yepes and Titos Martinez1995, p. 98). Florence was smaller than Bordeaux but handled twice as many pawns per year (Pastureau and Blancheton Reference Pastureau and Blancheton2014, p. 288), while Turin was approximately the same size of Mexico City in the 1890s but the number of pawn transactions was 10 times higher (Francois Reference Francois2006, pp. 210, 318).

Contrary to the traditional interpretation, Italian MdP were neither retrograde nor obsolete. They were widely distributed, numerous and well suited to providing much-needed financial aid at the lower end of the market. They accompanied the modernizing spurts of the Italian economy and adapted to its patchwork developments. They responded to a social necessity in a nation afflicted by high levels of poverty and increasingly beset by massive permanent migration.

Ironically, while other developing countries adopted the Italian model of public pawn banks to complement their credit networks, to reach precarious social groups and to prevent their social exclusion, the new Italian state viewed pawn banks as a hurdle on the way to the development of modern banking. Rather than expand them, as others governments were doing, it tried to jettison them. Ideology and hostile regulations enacted by the new Italian state were misconceived. Although MdP remained in business despite all odds, national legislation hampered the traditional access to credit of those most in need – both the traditional rural poor and the growing cohorts of new industrial poor. In doing so, it hardly assisted in speeding up the nation's social and economic development.