I

Nineteenth-century British economic policy was characterised by a commitment to the principles of laissez-faire ideology, which some commentators have argued resulted in the limited development of corporate accounting regulation (Jones and Aiken Reference Jones and Aiken1994, p. 198). However, scholars such as Parker (Reference Parker1990, p. 52) and Morris (Reference Morris1993, p. 165) have recognised that select industries – such as banks, financial institutions, public utilities and railways – were subject to varying degrees of regulation associated with the presence of monopoly powers and the importance of safeguarding the privileges of the state. Bank stability was a matter of public and state interest (Parker Reference Parker1990, p. 57; Sánchez-Ballesta and Lloréns Reference Sánchez-Ballesta and Lloréns2010, pp. 404–5), because banking failures could threaten the financial safety and security of deposits (Lloréns Reference Lloréns2004, p. 2). Parliament, as a steward of the monetary framework, tightened controls over the banking industry in the second quarter of the nineteenth century. This included intervening in the affairs of the Bank of England, as well as those of private and joint stock banks where the power of issuing notes and extending credit remained with the owners (Parker Reference Parker1990, p.57).

The Bank of England dominated English banking from its establishment in 1694 (Collins Reference Collins1988, pp. 10–11). The creation of the bank strengthened London's money market and operated to facilitate the finance needs of government. As a commercial bank, the Bank of England enjoyed governmental privileges enacted within its charter (Schooner and Taylor Reference Schooner and Taylor1999, p. 606). The Bank was the only banking institution able to raise capital from a large number of investors. The Bank of England Act 1697 had reinforced the monopoly of the Bank of England by preventing the setup and operation of any other banking corporation in England (Checkland Reference Checkland1975, p. 46). The passage of the Bank of England Act 1708 had further sanctioned this monopoly by requiring all other banks in England issuing notes to operate under a six-partner rule with unlimited liability. This created some instability in the banking system by encouraging small-scale banking operations advanced by the partnership form and an absence of specialist bankers (Newton Reference Newton2007, p. 3).

Over a century later, the Bank of England Act 1819 introduced another form of financial accountability, by requiring the Bank to lay before parliament an annual account of Exchequer and Treasury Bills, as well as any other government securities purchased and advances that had been made to parliament. These financial accountability requirements were minimal, and did little to prevent the bank failures that occurred in England leading to the major financial crisis of 1825–6 (Neal Reference Neal1998, pp. 53–4). The crisis marked the beginning of a major transformation of the banking system in Britain (Collins Reference Collins1988, p. 9). The Bank of England, country bankers and private bankers were part of a system of banking that needed to adapt to meet the needs of industry and commerce (Cottrell and Newton Reference Cottrell, Newton, Sylla, Tilly and Tortella1999, pp. 81–2). In 1826, the government intervened in the banking system and allowed joint stock banks to engage more partners and to access more capital. In terms of joint stock banks:

It was highlighted that they had a broader and therefore more stable capital base due to their ability to issue shares. They also emphasised that their wealth was not based upon key individuals, family members or merely a few partners, as with the private banks. (Newton Reference Newton2007, p. 1)

Despite these concessions, further economic woes were realised in the financial crisis of 1836–7, with the failure of a number of prominent joint stock banks (Cottrell and Newton Reference Cottrell, Newton, Sylla, Tilly and Tortella1999, p. 83).

Financial crises and scandals have long been associated with advances in regulated accounting disclosures (Lloréns Reference Lloréns2004, p. 2). The British parliament responded to the financial crises of 1825–6 and 1836–7 with regulatory reforms. This included mandates for financial accountability, defined as the discharge of stewardship responsibilities by banks through the provision of financial information to key stakeholders (Game, Cullen and Brown Reference Game, Cullen and Brown2020, p. 1). Attention to transparency by banks was gradually sought by parliament in order to bring about stability in banking operations and help enhance banks’ reputation amongst stakeholders (Lloréns Reference Lloréns2004, p. 4). Using the official transcripts of parliamentary reports from Hansard, and by undertaking a textual analysis of reports recorded by the Mirror of Parliament, this study provides insight into parliamentary reforms and the growth in the financial accountability of banks following the banking crises of 1825–6 and 1836–7. This approach corresponds with Orzechowski's (Reference Orzechowski2019, pp. 181–2) analysis of parliamentary proceedings of free banking and the passage of the Bank Charter Act 1833. The research question posed in this study is:

What developments in the financial accountability of British banks occurred as a result of parliamentary reforms following the financial crises of 1825–6 and 1836–7?

The development of nineteenth-century company accounting legislation in Britain has drawn considerable interest from business historians (Parker Reference Parker1990; Morris Reference Morris1993; Jones and Aiken Reference Jones and Aiken1994). A number of these scholars have offered explanations for the causal impact of political and social influences in effecting regulatory changes (Brebner Reference Brebner1948; Crouch Reference Crouch1967; Taylor Reference Taylor1972; Parker Reference Parker1990; Jones and Aiken Reference Jones and Aiken1995). However, little attention has been devoted to the parliamentary reforms that targeted financial accountability in the period following the 1825–6 and 1836–7 financial crises. Even less attention has been devoted to parliamentary debates about the financial accountability of banks, which reveal the conflicts between laissez-faire doctrine and state intervention in practice. As such, this study seeks to assess parliamentary debates on the financial accountability of banks with particular attention given to the arguments they reveal regarding laissez-faire principles and state intervention. The contribution of this article is twofold. First, the study explains the influence of parliamentary reforms on the development of the financial accountability of British banks following the 1825–6 and 1836–7 financial crises. Second, the study articulates how an increasingly interventionist approach to government policy-making heightened the financial accountability of British banks.

The remainder of the article is organised as follows. Section ii provides an overview of the history of banking reform in Britain over the period 1825–45 and the financial crises of 1825–6 and 1836–7. Section iii elaborates on the economic philosophies and banking schools of thought in early nineteenth-century Britain. Section iv reveals the findings of the study before Section v presents the conclusion.

II

Following the end of the Napoleonic wars in 1815 and the resumption of cash payments in 1821, the British economy entered an expansionary phase (Bordo Reference Bordo1998, p. 77). A contraction followed by mid 1825, triggered by a drop in collateral values of the stock market and a reduction in note issues by the Bank of England (Neal Reference Neal1998, p. 64). City banks immediately became cautious and, by September 1825, some country banks also faced difficulties (Neal Reference Neal1998, p. 64). The failure of Wentworth, Chaloner and Co., a major banking house, created panic, causing a run on several other London banks (Tooke and Newmarch Reference Tooke and Newmarch1848, p. 335). Shortly after, another major banking house, Pole, Thornton and Co., closed its doors (Tooke and Newmarch Reference Tooke and Newmarch1848, p. 336). This encouraged some country banks to procure specie and bank notes from London banks as security against a potential run on their funds (Neal Reference Neal1998 p. 65).

The ensuing liquidity crisis impacted cash reserves, and threatened the convertibility of notes. The public lost trust in the country banks and presented notes en masse to exchange for coin or Bank of England notes (Collins Reference Collins1988, p. 17). Unable to meet these demands for cash, many banks closed their doors. Of the 571 commercial banks (figures exclude Ireland and the three chartered banks of Scotland), 105 banks failed during 1825–6 and almost all of the country banks sought assistance from the Bank of England (Turner Reference Turner2012, p. 39). At the peak of the crisis, and to alleviate panic, the Bank of England increased its lending and narrowly averted issues itself regarding the convertibility of notes (Collins Reference Collins1988, p. 17). The Bank of England and private bankers argued that the country banks were responsible for the crisis due to their excessive note issues. On the other hand, it was suggested that the Bank of England was also culpable due to its role in expanding the money supply between 1822 and 1824, and for neglecting to ‘offset the monetary expansion occurring elsewhere’ (Neal Reference Neal1998, p. 69).

The regulatory reforms of 1826 aimed to bolster the stability of the banking sector. The first reform in March 1826 restricted the circulation of notes in England under £5. This measure saw parliament attempting to curb the circulation of small note denominations due to the volatile nature of this type of money supply (Collins Reference Collins1988, pp. 16–17). The second reform in May 1826 diluted the monopoly of the Bank of England by encouraging the growth of joint stock banks and branch networks. This created an opportunity for dispersed ownership and increased access to capital resources. The 1826 legislative reforms in England took their lead from Scotland (Cottrell and Newton Reference Cottrell, Newton, Sylla, Tilly and Tortella1999, p. 82), where joint stock banks had remained relatively unscathed by the events of 1825–6 (Freeman, Pearson and Taylor Reference Freeman, Pearson and Taylor2012, pp. 45–6). The uptake of English joint stock banking after 1826 was slow and private banks remained active participants in the money market. This may be attributed, in part, to prevailing uncertainty about ‘the duties, rights and privileges of the new corporations’, as well as the adverse economic conditions of the time (Collins Reference Collins1988, p. 68).

The Bank of England's monopoly was further eroded in 1833 when legislation removed a 65-mile exclusion zone. This permitted joint stock banks to establish branches within London, albeit without note-issuing rights (Barnes and Newton Reference Barnes and Newton2014, p. 10). Thereafter, economic conditions strengthened and there was a rapid uptake of joint stock banking in England as well as in Ireland and Scotland (Collins Reference Collins1988, pp. 68–9). In addition to the growth of joint stock companies, the mid 1830s was characterised by a railway boom and the rise of commercial transactions abroad (Turner Reference Turner2012, p. 40; Capie Reference Capie, Dimsdale and Hotson2014, p. 12). However, there was also excessive discounting of questionable securities in this period, most of which were related to Anglo-American trade (Capie Reference Capie, Dimsdale and Hotson2014, p. 12). A decline in railway stock prices in 1836 and 1837 affected both capital and money markets (Turner Reference Turner2012, p. 40). Whilst the structure of joint stock banks made them safer, some of the newly formed joint stock banks did encounter problems. As Chapman has argued,

The precept of the new joint-stock banks was to serve ‘safe and profitable’ customers; before credit was offered ‘the most prudential inquiries were made regarding the prosperity of giving those occasional advances’ and was extended only to ‘houses considered perfectly entitled to them.’ But there can be no doubt that the practice was more erratic. The abundance of capital, low interest rates, and the inexperience of the joint-stock banks gave rise to much unsecured credit, most blatantly in Manchester and Liverpool. (Chapman Reference Chapman1979, p. 59)

The expansion phase ended swiftly with a recession across Britain in the later part of 1836 (Collins Reference Collins1988, p. 69). This triggered, by 1837, the high-profile failures of the recently established Northern and Central Bank and the Agricultural and Commercial Bank of Ireland (Turner Reference Turner2012, p. 40). The failure rate of banks was low. Only five of the ‘weaker and riskier banks’ failed (Turner Reference Turner2012, p. 40). However, the instability of branch network activities and poor bank management contributed to the crisis (Barnes and Newton Reference Barnes and Newton2018, p. 459; Collins Reference Collins1988, p. 84). Parliament was aware of these issues, but the failure of the Northern Central Bank heightened their concern (Barnes and Newton Reference Barnes and Newton2018, pp. 459–60).

A number of parliamentary inquiries were initiated between 1836 and 1840 to review the deficiencies in the British banking system. They investigated variously joint stock banks, branch networks and banks of issue. Legislation followed in 1844 to restrict joint stock banking in England with a return to charter-based incorporation (Barnes and Newton Reference Barnes and Newton2014, p. 11). Branch networks were discouraged, note issues in England and Wales were limited to what was already in circulation in 1844, and the publication of accounts by joint stock banks was mandated. From this date, the Bank of England was the only bank in England and Wales able to increase its circulation of notes. Scotland and Ireland passed similar Acts outlining restrictions for the issue of bank notes in 1845 (Collins Reference Collins1988, p. 72).

III

The philosophies of classic Liberalism and Benthamite utilitarianism greatly influenced British economic policy in the first three-quarters of the nineteenth century (Taylor Reference Taylor1972, p. 13). The government's economic outlook was based upon laissez-faire ideology. The economic works of Adam Smith and the utilitarian ideas of Jeremy Bentham both provided a foundation for laissez-faire principles (Taylor Reference Taylor1972, pp. 18, 32). Smith supported individual freedom and frowned upon state intervention, except in the case of foreign threats or to uphold justice (Taylor Reference Taylor1972, p. 19). Bentham also supported individual rights and supported legislation that would seek the greatest happiness for the greatest number (Jones and Aiken Reference Jones and Aiken1995, pp. 65–6). Both Smith and Bentham hold some claim to the establishment of laissez-faire as a theory of legislative action (Taylor Reference Taylor1972, pp. 18, 32).

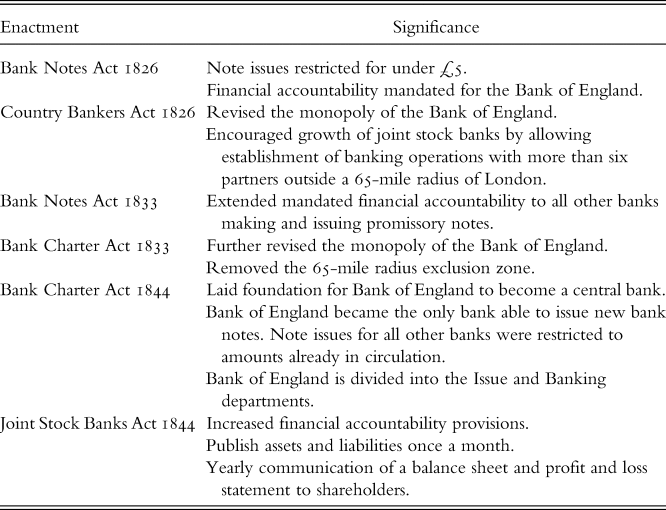

The predominance of laissez-faire policies in nineteenth-century Britain has been challenged by some historians (Taylor Reference Taylor1972, pp. 14–17). As a result, several studies have investigated the legislative environment to assess its influence in key policies and statutes (Brebner Reference Brebner1948; Crouch Reference Crouch1967; Parker Reference Parker1990; Jones and Aiken Reference Jones and Aiken1995). Here, particular industries including banks, financial institutions, railways and public utilities stand out as exempt from the wider adherence to laissez-faire principles (Parker Reference Parker1990, p. 52). These industries were all subject to state intervention to varying degrees with regards to the control of ‘monopoly, privilege and safety’ (Parker Reference Parker1990, p. 51). The 1825–6 and 1836–7 financial crises initiated parliamentary inquiries into the banking industry. This included mandating measures of financial accountability, commencing in 1826 with the full disclosure of note issues by the Bank of England. The extant literature guided the selection of banking enactments for this study and included those identified as important to the development of early nineteenth-century banking systems in Britain (Horsefield Reference Horsefield1944; Collins Reference Collins1984, Reference Game, Cullen and Brown1988; Jones and Aiken Reference Jones and Aiken1994; Neal Reference Neal1998; Barnes and Newton Reference Barnes and Newton2018). Table 1 provides a summary of the banking enactments featured within this study.

Table 1. Significant banking enactments, 1825–44

Both classical Liberalist and Benthamite movements aligned to one or more of the political parties within the British parliament (Bullock and Shock Reference Bullock and Shock2010, pp. xix-lv). The Whigs and Tories were the two dominant political parties in parliament during this period (Evans Reference Evans2001, pp. 25–6). The Whigs’ origin lay in constitutional monarchism and supremacy of parliament. They maintained a political stance that aligned with Liberalist ideologies (Evans Reference Evans2001, pp. 7–21). Tories defended conventional institutions including that of the monarchy and were loyal to conservative ideologies including free trade and patriotism (Evans Reference Evans2001, pp. 7–21). The dominance of the two parties continued thereafter with the Conservative Party and Liberal Party. The Conservative Party emerged from the Tory group in parliament in the mid 1830s, while the Liberal Party was believed to have originated after an agreement was made in 1835 between the Whigs, O'Connellite Irish and Radicals to act in union against the Conservatives (Evans Reference Evans2001, pp. 35–6).

Several political leaders were instrumental in contributing to parliamentary debates that would lead to banking reforms, and more specifically to increased pressure for financial accountability regarding banks. Table 2 lists these key contributors. Parliamentary debates on banking reform were generally shaped by three main schools of thought on monetary policy: the currency school, the banking school and the free banking school (Orzechowski Reference Orzechowski2019, p. 181). Key topics of debate following the financial crises of 1825–6 and 1836–7 centred on the convertibility of paper notes into specie, economic fluctuations, the banking system and the Bank of England's role in mediating the solidity of this system (Doroftei Reference Doroftei2013, p. 50). Key proponents of the currency school (including Samuel Jones Loyd, James Ramsey McCulloch and Robert Torrens) believed that note issuers should be required to hold an equivalent value of paper notes and specie (Eltis Reference Eltis2001, p. 6; Orzechowski Reference Orzechowski2019, p. 186). Proponents of the banking school (namely Thomas Tooke, James Wilson and John Fullerton) argued against the currency principle (Poovey Reference Poovey2008, p. 202). They believed that no principle could control the currency given that bank notes formed only one component of the exchange medium, which also included bills of exchange and deposits. The medium of exchange was less of a focus for the free banking school with anti-monopoly sentiments receiving more support (Poovey Reference Poovey2008, p. 202; Orzechowski Reference Orzechowski2019, p. 186). The key proponents of this view were Henry Parnell, Samuel Bailey, Thomas Hodgskin, George Scrope and James Gilbart.

Table 2. Selected political leaders that contributed to banking financial accountability, 1825–44

Sources: Evans Reference Evans2001; Coohill Reference Coohill2011; Fetter Reference Fetter1975.

A search of British parliamentary debates and committee reports using Hansard's parliamentary records, the Mirror of Parliament and the HathiTrust Digital Library was undertaken. The study identified records that contained reference to both the selected banking enactments and financial accountability provisions. These records, in combination with the legislative acts, form the basis of our argument about the development of the financial accountability of banks during the period under review. The parliamentary debates and committee reports were further analysed to determine the individual contribution of arguments provided by political leaders to resolutions on financial accountability. Transcripts were used to identify references to laissez-faire principles or calls for state intervention. Table 3 provides a summary of financial accountability provisions, including the extent of disclosure introduced, timeliness of reporting as well as dissemination and publicity requirements. The study identified these concepts of financial accountability in the analysis of banking regulations between 1825 and 1845. The item ‘notes in circulation’ has a separate line item due to its importance to banking stability in the nineteenth century. As highlighted in Table 3, note disclosures, introduced in 1826, were subject to timely presentation and publication requirements. Various mandates expanded across the time period to include prescribed forms of presentation, a full balance sheet and profit and loss account.

Table 3. Concepts of financial accountability

Note: The Country Bankers Act 1826 is excluded from this table as it did not include any of the concepts of financial accountability.

IV

The passage of the Bank Notes Act 1826 (22 March 1826) was instigated by the British government in reaction to the 1825–6 banking crisis. The Chancellor of Exchequer (Hon. Frederick John Robinson), deliberating on the excessive note issues by country bankers, raised concerns about the insecurities of circulating £1 and £2 notes (HC Deb 10 February 1826). The primary purpose of the Bank Notes Act 1826 was to ban note issues in England for any sum of less than £5.

Maberly, in taking an interventionist stance during a Commons debate on the Bank Notes Bill, raised an amendment to mandate a basic form of financial accountability on the Bank of England. The proposal suggested that the Bank of England publish a monthly account of all bank notes issued during the preceding month, as well as an account of all notes in circulation at that time (HC Deb 20 February 1826). Maberly praised the benefits of publicity, arguing that it would provide a check on the proceedings of the bank (HC Deb 20 February 1826). The United States and France were already adopting such measures and trading on the assurance it provided to the public about the soundness of bank operations. In Maberly's address to the House, he stated:

Why it was no more, nor so much as the Bank of France had always done. That Bank published an account of its issue of notes, and of gold, the extent of its discounts, and the amount of its profits; in short, it laid every part of its concerns fearlessly open to the inspection of the whole kingdom. And he was quite sure, that, by adopting a similar course, the Bank of England itself would be safer; the public, beyond all question, safer. (HC Deb 20 February 1826, col. 578)

Hume raised a similar recommendation to Maberly, although he believed the monthly account of circulation should extend beyond the Bank of England to include all other banks (HC Deb 27 February 1826). Hume argued for intervention in the regulation of banking financial accountability, citing evidence from the American banking system, where the chartered banks of New York furnished:

an annual account of their issues, and indeed of all their transactions, to the government; and if there appeared the least suspicion as to the solvency of any of them, a commission was immediately appointed to examine into, and report on the matter. (HC Deb 27 February 1826, col. 881)

However, application of regulated banking financial accountability to all other banks did not occur at this time.

In continuing the debate on the amendment raised by Maberly, the Chancellor stated:

that although he was not an enemy to publicity in the transactions of the Bank, he did not conceive that there were the same reasons for demanding a compulsory statement of all its issues, as there were for requiring an account of the circulation of small notes. The House, he admitted, might exercise its power in requiring the amount of issues for a particular purpose; but as a general rule, it was his opinion, that it would lead to serious inconveniencies. He had then stated his objections to the hon. member's motion, to be founded on these grounds; and he begged now to say, that his judgment remained unaltered. It would therefore be better that the subject should now be taken up at the point where it had been broken off.

The Chairman then read the clause enacting that the Bank of England should every month make a return of all the one and two pound notes in circulation since the preceding month, and the amendment moved by Mr. Maberly on Friday, ‘and also an account of the amount of all the notes in circulation since the last day of the preceding month.’ On the amendment being put, . . . (HC Deb 27 February 1826, col. 893)

The Chancellor indicated that it was an unjust inconvenience, which could mislead and result in undue panic if the public became fearful of suffering loss or bank failure (HC Deb 27 February 1826). Maberly argued that publicity was critical to secure against fluctuations that may arise by the expansion and contraction of bank notes. He argued further that the Bank of England had no reason not to publish accounts with the same level of detail as demonstrated in the accounts of the Bank of France. However, he did not suggest that the model adopted by the Bank of France was relevant to Britain. Expectations on the Bank of England were limited to information on its note issues and notes in circulation, which historically could alter significantly. Maberly reiterated that there was no reason for not introducing the additional publicity and that it was in the public interest for the government to compel the bank to make the disclosure (HC Deb 27 February 1826).

Upon assent of the Bank Notes Act 1826, the Bank of England was required under section 6 to deliver to the Treasury a monthly account of notes in circulation under £5 as well as the total notes in circulation, with the same to be published in the London Gazette. Public dissemination of financial information was perhaps the most important contribution of the Bank Notes Act 1826. It is worth noting here that these requirements align with items from 1, 5 and 6 of Table 3's concepts of financial accountability.

The Country Bankers Act 1826 (26 May 1826) was also introduced to restore stability in the English banking sector. The Act amended the monopoly of the Bank of England by allowing the formation of joint stock banks with any number of partners, outside a 65-mile radius of London (Barnes and Newton Reference Barnes and Newton2014, pp. 9–10). Sections 4 and 5 of the Country Bankers Act 1826 detailed aspects of accountable governance. In a demonstration of laissez-faire economics, none of these provisions related to the supply of financial information. Section 4 of the Country Bankers Act 1826 required a return to be lodged at the London Stamp Office prior to the issue or transaction of bills or notes. A prescribed form was developed for the return that detailed the name of the firm as well as the members and public officers of the bank. Section 5 of the Act required the return to be verified by the secretary or a public officer and lodged annually. Noticeably, these requirements do not align with any of Table 3's concepts of financial accountability.

The Bank of England charter was due for renewal in 1833. This led to discussions in parliament on the subject as well as on other banking institutions. Lord Althorp addressed the House on 31 May 1833 and raised a number of points with implications for country banks (HC Deb 31 May 1833). One of these points considered the subject of financial accountability:

It is desirable, that the country should know at all times the exact amount of country bankers’ notes in circulation; and not real or substantial evil can happen in the case of any country banker from such an arrangement; and, further, I am of the opinion, that it is desirable to know, not only the amount of each country banker's paper in circulation, but also the amount of his general assets to meet the demands upon him. (HC Deb 31 May 1833, col. 185)

The requirement for all other banks ‘making and issuing Promissory Notes payable to Bearer on Demand’ to prepare a return of notes in circulation was a primary contribution of the Bank Notes Act 1833 (28 August 1833). However akin to laissez-faire principles, the proposal did not extend existing requirements placed upon the Bank of England by the legislation of 1826, and there was no requirement for publication. The Bank Notes Act 1833 required banks to keep weekly accounts of the average notes in circulation. These averages, consolidated on a quarterly basis, comprised the account submitted to the Commissioner of Stamps. Critically, these requirements align with items 1, 5 and 6 of Table 3's concepts of financial accountability.

The Bank Charter Act 1833 (29 August 1833) further diluted the monopoly of the Bank of England by removing the 65-mile exclusion zone. This allowed banks to establish in London, albeit without note-issuing rights (Barnes and Newton Reference Barnes and Newton2018). Lord Althorp was instrumental in driving the proposal to establish a secret committee on the Bank of England charter, and on the system of banks of issue in England and Wales (HC Deb 22 May 1832). The secret committee deliberated on three key issues, including financial accountability:

What checks can be provided to secure for the Public a proper management of Banks of Issue, and especially whether it would be expedient and safe to compel them periodically to publish their Accounts? (Report from the Committee of Secrecy on the Bank of England Charter, 1832, p. 2)

Due to the limited progress of the inquiry and insufficient materials, the committee declined to offer an opinion on all points. They did provide, with some minor exceptions, the evidence collected for the committee report in its entirety, which was key to subsequent parliamentary debates on the Bank of England charter.

Eight resolutions were proposed by Lord Althorp on 31 May 1833 (Orzechowski Reference Orzechowski2019, pp. 191–2). Resolutions 1–5 were specific to the Bank of England charter. Resolutions 6 and 8 related to joint stock banks, and resolution 7 related to stamp duty on the issue of bank notes. Resolution 1 was for the continuation of the Bank of England charter, subject to the publication of the Bank's accounts. Lord Althorp agreed that the publication of accounts was the most efficient form of check on the bank. The proposal was for the Bank of England to continue as the single bank of issue in London, subject to the control of publicity:

As to the next point, to which I have already alluded – the publication of the accounts of the Bank – I propose, that a weekly account of the amount of bullion and securities on the one hand, and of the paper in circulation, and deposits on the other hand, should be presented to the Treasury, and that, at the end of the quarter, the averages of the preceding quarter should be published in The Gazette. I do not suggest, that the publication should take place weekly for this reason – that it might lead, on many occasions, to false impressions. It may frequently occur, from circumstances not at all connected with the state of the currency, or with the State of the exchanges, that a large sum of bullion may be drawn out of the Bank at one period, which, if the account were published every week, might have an effect upon the public mind, neither just nor desirable. (HC Deb 31 May 1833, col. 178)

The intent of publishing averages of the preceding quarter was to assure the public of the Bank's ongoing system of sound management.

In resolution 6 Lord Althorp proposed a return to charter-based incorporation for newly established joint stock banks, subject to certain conditions. Resolution 8 addressed the provisions for joint stock banks (HC Deb 31 May 1833). The conditions required joint stock banks of issue to deposit in government securities an amount equal to half of the subscribed capital. The liability of the capital was unlimited, and the Bank of England could not hold any shares in the bank (HC Deb 31 May 1833). There was also a requirement to publish accounts periodically. For non-issuing joint stock banks, he proposed that one-fourth of subscribed capital comprised government securities. The minimum value of each share was set at £100 and partner liability was limited to the extent of shares held. Notably, resolutions 6 and 8 on joint stock banks were withdrawn (Orzechowski Reference Orzechowski2019, pp. 191–2).

Financial accountability regulations contained within the Bank Charter Act 1833 may still be considered laissez-faire due to the minimal progression of the clauses within. Section 8 of the Act required the transmission of weekly accounts to the Chancellor of Exchequer. This account contained the amount of bullion and securities of the bank belonging to the governor and company, and of the notes in circulation and deposits. The accounts were consolidated at the end of each month and an average made up of the preceding three months published monthly in the London Gazette. The additional requirements introduced after the Bank Notes Act 1826 related to the disclosure of bullion and securities and the amount of deposits. Here, the financial accountability requirements align with items from 1, 2, 5 and 6 of Table 3's concepts of financial accountability.

Concerns regarding the Country Bankers Act 1826 were first raised in 1832 due to the growing number of joint stock banks and their questionable character (Newton and Cottrell Reference Newton and Cottrell1998, p. 116). However, it was 1836 before more definitive action was taken, when Clay raised a motion to appoint a select committee to review the deficiencies of the Country Bankers Act 1826 (HC Deb 12 May 1836). Deliberating on the defects of the system, Clay proposed a three-pronged remedy including the principles of limited liability, paid-up capital and perfect publicity:

The publicity that I would require, moreover, would be real, searching, and effecting – making clear apprehension of all men the circumstances of the bank both as to its assets and liabilities. Such publicity, so far from being injurious, would be in a high degree beneficial to sound and well-conducted banking establishments, and we should permit no other. (HC Deb 12 May 1836, col. 855)

To support his position, Clay referred to the Bank of England and the benefit of unlimited liability and large paid-up capital. He debated whether ‘great errors’ and distress could have been avoided if publicity had been imposed on it (HC Deb 12 May 1836). Clay referred to the Bank of Scotland, Royal Bank of Scotland and the British Linen Company who also operated on the principle of limited liability and a large paid-up capital. Similarly, the United States (US) system of banking included almost absolute application of limited liability, paid-up capital and publicity. He raised the Colombia Banking Act 1817 in the US, where joint stock banks operated under certain conditions including the requirement to provide a full statement of their affairs annually to the Secretary of Treasury (HC Deb 12 May 1836). Here, Clay clearly supports intervention in the financial accountability of banks.

The Secret Committee on Joint Stock Banks presented a report of their findings in August 1836. The committee raised several points regarding the system of banking that required serious consideration. Point 7 touched on financial accountability:

The Law does not provide for any publication of the liabilities and assets of these Banks, nor does it enforce the communication of any balance sheet to the Proprietors at large (Report from the Secret Committee on Joint Stock Banks, 1836, p. ix)

These requirements were subsequently included in the Joint Stock Banks Act 1844.

The 1836–7 financial crisis again earmarked note issues as an area for legislative reform (Collins Reference Collins1978, p. 379). In 1840, the House of Commons appointed another select committee to address banks of issue. In moving for the select committee, the Chancellor of Exchequer (Hon. Francis Baring) attempted to justify his recommendation:

I state this, in order that the House may see that an inquiry of this nature must be in a very short time forced upon it. It cannot avoid that inquiry; the state of the law of the country renders it inevitable; for I do not conceive it is possible to enter into a fair and proper inquiry touching the renewal of the Bank of England charter, without going, at the same time, into the whole subject. (Mirror of Parliament, 10 March 1840; see Barrow Reference Barrow1840, p. 1676)

The Chancellor also raised the importance of reviewing the financial accountability clause imposed on the Bank of England in the previous Act:

There is, also, for consideration, that clause in the Act which renders notes of the Bank of England a legal tender; and, lastly, a point which is now in the charter, the averages of the Bank of England. Much discussion took place on this point, and much fear and alarm were, at the time, expressed at letting the public into the secrets, as they were called, of the banks. We have now had some experience on that point, and may proceed to consider whether the expected advantage has been derived from it; and if anything turns out to show that the alarm was unfounded, whether the Returns, as they are made at present, afford to the public that information which it is intended should be given to them (Mirror of Parliament, 10 March 1840; see Barrow Reference Barrow1840, p. 1678)

The committee declined offering an opinion to the House on the main subject at hand, instead providing access to the evidence collected. However, on the topic of financial accountability witness testimony highlighted an expectation of increased publicity (Horsefield Reference Horsefield1944, p. 188). The anticipation was secured by An Act to Make Further Provision Relative to the Returns to be Made by Banks of the Amount of Their Notes in Circulation 1841 with application throughout the United Kingdom. Issuing banks were required to keep weekly accounts of the amount of notes in circulation with the averages to be consolidated monthly. The London Gazette published the monthly average of notes in circulation along with accounts provided by the Bank of England for the same period. The practical effect of the Act was to increase the frequency of financial disclosure from quarterly to monthly, and to mandate publication for all banks of issue.

The Bank of England charter came up for renewal again in 1844. Sir Robert Peel raised 11 resolutions for consideration when the House moved into a committee to discuss the subject. Some of these related to points Lord Overstone first raised in his contribution to the debates on the currency, and the evidence he provided during the 1840 select committee hearing (Eltis Reference Eltis2001, p. 7). Items 1–7 were specific to the Bank of England and items 8–11 related to other banking institutions (HC Deb 20 May 1844). The Bank Charter Act 1844 (19 July 1844) restricted note issues to the amounts already in circulation during 1844 and the Bank of England became the only bank able to issue new bank notes (Barnes and Newton Reference Barnes and Newton2018, p. 460). The Bank of England was separated into the Issue Department and Banking Department to ensure matters related to the issuing of promissory notes payable on demand (Issue Department) remained distinct from matters relating to the general banking business (Banking Department).

One of the most important innovations of the Bank Charter Act 1844 was the requirement to publish bank returns weekly (Whale Reference Whale1944, p. 111). Sir Robert Peel refuted the objections that had been raised regarding publication in 1833. He reiterated the benefit of this approach in reassuring the public regarding the credit of the bank (HC Deb 6 May 1844). It was on these grounds that Peel proposed the publication of Bank of England accounts from both the Banking and Issue Departments. The proposal sought a weekly return to the government of the amount of note issues, amount of bullion, deposits and of securities and in general a summary of all transactions processed by both Departments (HC Deb 6 May 1844).

In addition to Peel's proposal, Wood remarked on the form of published accounts by the Bank of England and deemed it desirable for the inclusion of disclosures on reserves and capital:

It is of importance, that we should have the amount of notes ‘with the public,’ distinguished from those which form ‘the reserve of the Bank,’ within the walls of the Bank. We should have the former, if only for the purpose of comparison with the amounts of circulation now published. It is very desirable too, that the public should know what is the amount of notes in reserve in the Bank. The Bank has an immense monied power, and with such a reserve as they happen to have at present, of 9,500,000l, they have the power of throwing in the money market an amount that would damage the ordinary transactions. It is not likely that the present state of things should last long, or occur very often, but still it is desirable that the public should know what is hanging over them in the shape of the Banking reserve. It is also, I think desirable, that the public should know the amount of the capital of the Bank. This has never appeared in the published accounts; but when the publication is to be made so frequent, so accurate, and so full, I think it will be as well that all of the world should see that there is ample security for the safety of the public and of the creditors of the Bank. (HC Deb 20 May 1844, pp. 1372–3)

Further to the requirements detailed for the Bank of England, Peel proposed that all other banks issuing promissory notes should provide a weekly publication of issue (HC Deb 6 May 1844). Justifying the demand for publicity of note issues, Peel stated:

It is said, that the weekly publication of issues will disclose secrets of which a rival may take advantage; that it will show ‘the weak point’. Now I wish ‘the weak point’ (if there be one) to be shown, and that the public may have the advantage of knowing it. (HC Deb 6 May 1844, p. 746)

Peel aligned with laissez-faire ideologies, disagreed with further mandates of financial accountability, other than those requirements already raised regarding note issues:

It has been frequently proposed to require from each bank a periodical publication of its liabilities, its assets, and the state of its transactions generally. But I have seen no form of account which would be at all satisfactory – no form of account which might not be rendered by a bank on the very verge of insolvency, if there were the intention to conceal a desperate state of affairs. The return for instance of ‘overdrawn accounts’ might lead to very erroneous inferences as to the condition of a bank making such a return. A large amount of overdrawn accounts might in one case be indicative of gross mismanagement. It might in another case be perfectly compatible with the security of a bank, acting on the Scotch principle, and making advances at interest to customers in whom the bank had entire confidence. (HC Deb 6 May 1844, p. 747)

The Bank Charter Act 1844 detailed the financial accountability provisions to be observed by the Bank of England in section 6. The bank was required to keep a weekly account in the prescribed form, for the Issue Department and Banking Department. Disclosures for the Issue Department included the amount of note issues, gold coin, gold and silver bullion and securities. Disclosures for the Banking Department included the amount of capital, deposits, and money and securities belonging to the governor and company respectively. The London Gazette would publish these accounts. Akin to the Bank Charter Act 1833, these requirements align with 1, 2, 4, 5 and 6 of Table 3's concepts of financial accountability. The disclosure of capital was an important addition in the development of the financial accountability of banks. With the exception of capital, the financial accountability provisions introduced in the Bank Charter Act 1844 were similar to those already mandated in 1833, but modified to suit a separation of departments (Horsefield Reference Horsefield1944, pp. 188–9).

Financial accountability of other issuing banks was dealt with under section 18 of the Act. Banks issuing notes in England and Wales were to submit to the Commissioner weekly accounts in the prescribed form of the amount of bank notes it issued every day, including an average amount of the notes in circulation during the same week. At the end of every four-week period, an account of the averages during that period was to be compiled and reported along with the amount of the bank notes authorised to be issued. These requirements varied little from the requirements raised by the Bank Notes Act 1833. The London Gazette published the weekly average amounts of the notes in circulation. These requirements also align with items 1, 4, 5 and 6 of Table 3's concepts of financial accountability.

The Joint Stock Banks Act 1844 (5 September 1844) represented the first significant intervention by the British parliament in regulating banking financial accountability in England. The initial proposal regarding the Joint Stock Banks Act 1844 was raised in the Commons debate associated with the Bank Charter Act 1844 (HC Deb 6 May 1844). As with the Bank Charter Act 1844, Peel was instrumental in driving the proposal related to joint stock banks. Notably, components of the proposal were similar to recommendations made by Lord Althorp in 1833. Under the provisions of the Act, the charter-based incorporation returned. The proposed amount of capital was set at a minimum of £100,000 and a share value of no less than £100. A number of points were also outlined in the Act for inclusion in the Deed of Partnership for every banking company.

The Joint Stock Banks Act 1844 took on, in part, the recommendation of the Secret Committee on Joint Stock Banks 1836 regarding the publication of assets and liabilities and yearly communication of a balance sheet to shareholders. The communication of a profit and loss account was also included in the Act, despite not having been a recommendation of the secret committee. Eight years had passed before the secret committee's recommendations were implemented.

Section 4 of the Joint Stock Banks Act 1844 required the Deed of Partnership of every banking company to include specific provisions related to the publication of assets and liabilities once a month. They also mandated the communication of a balance sheet and profit and loss account annually to shareholders. Whilst not a consideration of this study, the Deed of Partnership required an audit. These financial accountability requirements were the most comprehensive in the banking history of England. They align with all items in Table 3's concepts of financial accountability.

V

The 1825–6 and 1836–7 financial crises directed the government's attention to the potential problems associated with note issues. Consequently, note issues became the cornerstone of regulatory reforms for the banks of Britain in the first half of the nineteenth century. The government responded swiftly to the 1825–6 banking crisis; however, in terms of regulating financial accountability, the initial response may be deemed laissez-faire. Initial mandates to introduce financial accountability measures were limited to an immediate check on the note issues of the Bank of England. In the Bank Notes Act 1826, the Bank of England was required to provide and publish a monthly account of note issues under £5 as well as the total amount of notes in circulation. Thereafter, the Country Bankers Act 1826 was passed and was deemed the government's major response to the 1825–6 banking crisis (Barnes and Newton Reference Barnes and Newton2018, p. 459). Surprisingly, the government refrained from enforcing more mandates to impose financial accountability. This apparent silence was criticised by a secret committee in 1836 as the banking laws did not require the publication of liabilities and assets nor did the laws require the communication of a balance sheet to shareholders.

Lord Althorp was instrumental in ensuring the Bank Notes Act 1833 extended financial accountability requirements for the disclosure of note issues to all other banks making and issuing promissory notes in London. Whilst interventionist in principle, financial accountability requirements were still limited to note issues. Parliament appeared reluctant to mandate financial accountability requirements already practised in the US and France. The Bank Charter Act 1833, similarly led by Lord Althorp, strengthened financial accountability mandates on the Bank of England by introducing disclosures beyond note issues to include amounts of bullion and securities belonging to the governor and company as well as deposits.

The next round of incremental regulatory reforms occurred after the 1836–7 financial crisis, when Peel made a number of recommendations leading to the Bank Charter Act 1844 and the Joint Stock Banks Act 1844. Consistent with the tenets of laissez-faire ideology, the Bank Charter Act 1844 progressed little in terms of financial accountability, with mandates similar to those enacted in 1833. The Act did, however, split the functions and reporting of the Bank of England into the Issue and Banking departments. The passage of the Joint Stock Banks Act 1844 introduced extensive provisions for financial accountability in the form of monthly publication of assets and liabilities and an annual communication of a balance sheet and profit and loss account to shareholders. Peel favoured the disclosures surrounding note issues. However, he did not support further mandates of financial accountability for fear of invalid inferences towards the banks making the returns. Regardless, eight years after they were first raised, the Joint Stock Banks Act 1844 incorporated recommendations from the secret committee report of 1836 by mandating the monthly publication of assets and liabilities and the yearly communication of a balance sheet to shareholders.

These findings suggest that state intervention in imposing financial accountability requirements on banks in the first half of the nineteenth century was cumulative. Initial findings suggest that parliamentary intervention was limited, due to the fear of mistaken inferences by the release and publication of information. However, by 1844 parliament imposed expansive control over the banking industry by mandating comprehensive financial accountability requirements. Whilst this study has focused primarily on financial accountability related to the disclosure of accounting information in the form of financial reports, future research may expand upon this research to conduct a similar study related to the development of audit and the impact of these developments on banking regulation and financial accountability.