Although childhood disorders of cognition, language and behaviour are extremely common (WHO: http://www.who.int/en/), causative genes have remained particularly refractory to traditional genetic approaches since the disorders themselves are often sporadic in nature and their causes complex and both genetically and environmentally heterogeneous. Genomic disorders, caused by the gain, loss or inversion of specific chromosome regions, are often characterised by neurodevelopmental phenotypes and present a unique opportunity to identify genes and pathways that are necessary for proper brain development and function (Ref. Reference Inoue and Lupski1).

One such region that is prone to genomic rearrangement is the Williams–Beuren syndrome (WBS) locus at chromosome 7q11.23. This 1.5 million base pair region has been shown to commonly undergo deletion, duplication or inversion through unequal meiotic recombination between highly similar flanking segments of DNA (Refs Reference Valero2, Reference Osborne3, Reference Somerville4). Inversion of the region is not associated with any clinical features, but can predispose the chromosome to subsequent unequal recombination during the next round of meiosis. The inversion is estimated to be present at a frequency of 1 in 20, but there is a fivefold increase in carrier frequency in the parents of children with the WBS deletion (Refs Reference Osborne3, Reference Bayes5). Deletion and duplication of 7q11.23 result in distinct patterns of cognitive impairment, both of which impact on language and speech abilities, albeit in very different ways (Refs Reference Somerville4, Reference Mervis and Becerra6, Reference Mervis and Klein-Tasman7) . The WBS deletion has an estimated frequency of between 1 in 7500 and 1 in 20 000 (Refs Reference Greenberg8, Reference Strømme, Bjørnstad and Ramstad9). As a result of the mechanism of genomic rearrangement, duplication should occur at a similar frequency; however, owing to its very recent discovery, the population frequency has not yet been determined.

Genomic structure of 7q11.23

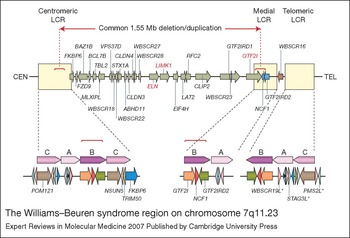

The WBS region lies on the long arm of chromosome 7, at 7q11.23 (Ref. Reference Ewart10). It is flanked by chromosome-specific, low-copy repeats (LCRs) that are thought to be directly responsible for the recurrent rearrangements (Ref. Reference Valero2). Deletion of the region has been shown to occur as a result of unequal meiotic recombination between grandparental chromosomes in the transmitting parent (Refs Reference Dutly and Schinzel11, Reference Urban12), and two-thirds are interchromosomal rearrangements (between the chromosome 7 homologues) while the remainder are intrachromosomal rearrangements (between sister chromatids of the same chromosome 7) (Ref. Reference Baumer13). It is predicted that this nonallelic homologous recombination is precipitated by the LCRs, which are made up of genes, pseudogenes and gene clusters that form highly homologous stretches of sequence (Refs Reference Osborne14, Reference Perez Jurado15, Reference DeSilva16). These regions have been broken down into blocks named A, B and C, which are present in the centromeric, medial and telomeric LCRs (Fig. 1). Each centromeric, medial and telomeric block can be distinguished by single nucleotide differences, but regions of greater than 99% sequence identity exist over distances of 100 kilobases or more, making detailed analysis of the LCRs extremely difficult (Ref. Reference Bayes5).

Figure 1 The Williams–Beuren syndrome region on chromosome 7q11.23. Genes within the 1.55 Mb commonly deleted/duplicated region at 7q11.23 are represented by green arrows indicating the direction of transcription. ELN (elastin), LIMK (LIM domain kinase 1) and GTF2I (general transcription factor II, I) all of which have been linked to phenotypic aspects of Williams–Beuren syndrome, are highlighted in red. The two genes that are variably deleted/duplicated, depending upon the location of the telomeric breakpoint, are represented by blue arrows. WBSCR16, which lies outside the commonly deleted/duplicated region, is represented by a brown arrow. The flanking low-copy repeats (LCRs), which mediate meiotic rearrangement of the region, are represented by cream-coloured boxes. Each LCR is expanded beneath to show its composition of blocks of homology designated A, B and C. Approximately 95% of deletions occur between the highly similar B-blocks in the centromeric and medial LCRs, as indicated by the dotted red lines. Pseudogenes are indicated by an asterisk. For full versions of gene names see the HUGO Gene Nomenclature Committee website (http://www.gene.ucl.ac.uk/nomenclature/index.html). The figure was adapted from Ref. Reference Scherer, Osborne, Stankiewicz and Lupski113, with permission from Humana Press.

The common WBS deletion almost always occurs between the directly oriented B-blocks, although a small proportion of breakpoints reside in the A-blocks (Ref. Reference Bayes5). Both the high homology and high level of transcription from the LCRs are thought to contribute to the frequency of rearrangement in this region. The predominance of recombination between the B-blocks rather than the A-blocks is postulated to occur because of the higher sequence identity (99.6% versus 98.2%), more contiguous homology (there are two interstitial deletions of the medial A-block), and the shorter distance between the B-blocks (1.55 Mb versus 1.84 Mb). Duplication of the region has also recently been demonstrated, with the recombination breakpoints mapping to the same highly conserved B-blocks as those of the deletion (Ref. Reference Somerville4). As mentioned earlier, recombination can also occur between blocks in an inverted orientation with respect to each other, and this results in a common, nonpathogenic inversion of the WBS region (Refs Reference Osborne3, Reference Bayes5).

Deletion at 7q11.23

Clinical, cognitive and behavioural features of WBS

WBS is a multisystem disorder, resulting in physical, cognitive and behavioural features that together present a unique clinical picture. WBS is associated with a recognisable facies, and characteristic cardiovascular lesions – most frequently supravalvular aortic stenosis – are found in ∼75% of patients. Other symptoms include hernias, visual impairment, hypersensitivity to sound, chronic otitis media, malocclusion, small or missing teeth, renal anomalies, constipation, vomiting, growth deficiency, infantile hypercalcaemia, musculoskeletal abnormalities, diabetes and a hoarse voice (Refs Reference Pober and Dykens17, Reference Morris18, Reference Morris, Morris, Lenhoff and Wang19, Reference Mervis, Morris, Mazzocco and Ross20).

Individuals with WBS usually have mild to moderate intellectual disability or learning difficulties. However, they characteristically exhibit distinct peaks and valleys of ability, with relative strengths in verbal short-term memory and in language, alongside extremely poor performance on visuospatial construction tasks (writing, drawing, pattern construction) (Ref. Reference Mervis, Winograd, Fivush and Hirst21). On the Kaufman Brief Intelligence Test (KBIT; Ref. Reference Kaufman and Kaufman22), the most commonly used IQ test in research studies of individuals with WBS, mean composite IQ is 69.32, with a range from 40 (lowest possible IQ on this measure) to 112 and a standard deviation of 15.36 (Ref. Reference Mervis, Morris, Mazzocco and Ross20). This mean composite IQ value is approximately 2 standard deviations below that for the general population, but with the same amount of variability. The KBIT measures verbal ability and nonverbal reasoning ability but does not assess visuospatial construction. When a full-scale measure of intellectual ability that includes visuospatial construction is used, mean IQ is considerably lower. For example, on the Differential Ability Scales (DAS; Ref. Reference Elliott23), mean general conceptual ability (GCA; similar to IQ) is 58.29, with a range from 24 (lowest possible GCA) to 95 and a standard deviation of 12.77 (Ref. Reference Mervis, Morris, Mazzocco and Ross20). However, for most children with WBS, GCA is not a valid indicator of intellectual ability because either their verbal standard score or their nonverbal reasoning standard score is significantly higher than expected given their GCA (Refs Reference Mervis, Morris, Mazzocco and Ross20, Reference Meyer-Lindenberg, Mervis and Berman24).

The behavioural profile for WBS includes overfriendliness, empathy and anxiety (Ref. Reference Klein-Tasman and Mervis25). Approximately 65% of children with WBS meet DSM-4 diagnostic criteria (Ref. 26) for attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD); ∼55% meet DSM-4 criteria for non-social specific phobia, and by early adolescence >20% meet DSM-4 criteria for generalised anxiety disorder, with a much higher proportion showing anticipatory worrying that is impairing but does not meet DSM-4 diagnostic criteria (Ref. Reference Leyfer27). Hyperreactivity, sensory integration dysfunction, and multiple developmental motor disabilities affecting balance, strength, coordination and motor planning are also seen in WBS (Ref. Reference Mervis, Morris, Mazzocco and Ross20).

Speech and language abilities in children with 7q11.23 deletion

Bellugi and her colleagues (e.g. Ref. Reference Bellugi, Bishop and Mogford28) brought WBS to the attention of cognitive and language researchers with the argument that WBS was characterised by ‘intact’ language despite severe mental retardation. Thus, WBS was argued to provide strong evidence of cognitive modularity – in particular, the independence of language from other aspects of cognition. Nevertheless, most researchers who are currently studying WBS do not consider the language abilities of individuals with WBS to be independent of their other cognitive abilities (Refs Reference Mervis and Becerra6, Reference Mervis29; for contrasting positions see Refs Reference Bellugi, Bishop and Mogford28, Reference Bellugi, Wang, Jernigan, Broman and Grafman30, Reference Clahsen and Almazan31, Reference Bellugi32, Reference Clahsen, Ring and Temple33).

Early language

There has been very little research on speech ability in WBS. However, it is known that the onset of babbling is delayed (Ref. Reference Masataka34), perhaps due to delays in the onset of rhythmic banging, which Masataka has argued provides the motor substrate for canonical babble (strings of at least two syllables composed of a consonant and a vowel, such as baba and dadada), without which the production of words is largely impossible. Velleman and her colleagues found that at 18 months, children with WBS evidenced more immature babble patterns than typically developing children of the same age (Ref. Reference Velleman, Horga and Mildner35). Early speech perception abilities are also delayed (Ref. Reference Nazzi, Paterson and Karmiloff-Smith36), and Nazzi et al. have argued that difficulty segmenting words out of the ongoing speech stream likely plays a role in the language delay characteristic of WBS. Although there have been no studies of the articulation skills of school-age children with WBS, most children with this syndrome are easy to understand by the early school years, if not sooner.

Vocabulary

For most children with WBS, age of acquisition of an expressive vocabulary of 100 words is below the fifth percentile for typically developing children (Ref. Reference Mervis and Becerra6, Reference Mervis and Robinson37). At age 4 years, children with WBS who showed the nonlinear vocabulary growth pattern characteristic of typically developing children (slow early growth followed by considerably more rapid later growth) had considerably more advanced vocabulary, grammar, memory and nonverbal abilities than children who showed a slow linear pattern of growth (Ref. Reference Mervis and Becerra6). For most older children and adults with WBS, receptive concrete vocabulary (understanding of words for objects, actions and descriptors) is their most advanced ability (Ref. Reference Mervis and Becerra6). The same pattern holds for individuals with Down syndrome (Ref. Reference Glenn and Cunningham38), although consistent with the general finding that mean IQ is lower for Down syndrome than for WBS (Ref. Reference Klein and Mervis39), the level of receptive vocabulary is lower for individuals with Down syndrome than for individuals with WBS of the same chronological age (CA). The receptive conceptual/relational language (e.g. spatial, temporal, quantitative and dimensional terms) ability of individuals with WBS is considerably weaker than their receptive concrete vocabulary (Ref. Reference Mervis, Morris, Lenhoff and Wang40) [closer to their level of visuospatial construction ability (Ref. Reference Mervis and Becerra6)].

Grammar

By late childhood, most individuals with WBS speak in complete sentences that are typically grammatically correct, whereas CA- and IQ-matched individuals with Down syndrome rarely speak in complete sentences. This contrast was critical to Bellugi's argument (Refs Reference Bellugi, Bishop and Mogford28, Reference Bellugi, Wang, Jernigan, Broman and Grafman30, Reference Bellugi32) that for individuals with WBS, language was independent of cognition. Bellugi's finding that individuals with WBS use more complex grammar than CA- and IQ-matched individuals with Down syndrome has been replicated by several research groups (Refs Reference Mervis, Morris, Lenhoff and Wang40, Reference Vicari41). However, when individuals with WBS are matched either to individuals with other aetiologies of intellectual disability for CA and IQ or to younger typically developing children for mental age, the grammatical abilities of the individuals with WBS are typically at the level of the contrast group [Refs Reference Mervis, Morris, Lenhoff and Wang40, Reference Udwin and Yule42, Reference Grant, Valian and Karmiloff-Smith43, Reference Zukowski, Rice and Warren44 (English); Ref. Reference Gosch, Stading and Pankau45 (German); Ref. Reference Lukács46 (Hungarian); Refs Reference Volterra47, Reference Volterra48 (Italian)]. Thus, Bellugi's original finding is currently interpreted as indicating the extreme difficulty that individuals with Down syndrome have with grammatical development, rather than that individuals with WBS have unusually good grammar relative to their overall intellectual abilities (Refs Reference Mervis and Becerra6, Reference Mervis, Morris, Mazzocco and Ross20, Reference Mervis and Abbeduto49). Studies of morphological abilities, especially in languages that have more complex morphology than in English, have indicated that these abilities are at the same level or slightly lower than those of typically developing children matched for mental age [Ref. Reference Karmiloff-Smith50 (French); Ref. Reference Levy and Hermon51 (Hebrew); Ref. Reference Lukács46 (Hungarian)]. Grammatical ability is more closely linked to verbal working memory ability for children with WBS than for younger typically developing children matched for grammatical ability (Ref. Reference Robinson, Mervis and Robinson52).

Pragmatic/communicative aspects

Although children with WBS are highly approaching and overly friendly (Ref. Reference Klein-Tasman and Mervis25), they have considerable difficulty with the pragmatic/communicative aspects of language. Toddlers with WBS are less likely to produce or comprehend referential gestures (e.g. points) or engage in triadic joint attention episodes (simultaneous attention to a communicative partner and an object or event) than are CA- and IQ-matched children with Down syndrome (Ref. Reference Mervis and Becerra6) or younger typically developing children matched for mental age (Ref. Reference Laing53). Although WBS is often argued, especially in the media, to be the clinical opposite of autism, the communicative difficulties identified in the studies of toddlers with WBS overlap those found in children who have autism. When preschoolers with WBS and limited language were assessed by the Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule (ADOS; Ref. Reference Lord54) Module 1, a semistructured measure designed to capture difficulties in sociocommunication for children with limited or no expressive language, more than half demonstrated significant difficulties with pointing, other gestures, giving, showing, and appropriate use of eye gaze (Ref. Reference Klein-Tasman55). Many also showed significant difficulties with joint attention and with the integration of gaze with other behaviours. Use of the Children's Communication Checklist (CCC; Ref. Reference Bishop56) to evaluate the language and communicative abilities of a group of older children and young adults with WBS showed that the majority met the criterion for pragmatic language impairment (Ref. Reference Laws and Bishop57).

Summary of language abilities in children with 7q11.23 deletion

In summary, although the language abilities of individuals with WBS are considerably more advanced than those of individuals with Down syndrome, they are not more advanced than expected for overall level of intellectual ability. Verbal working memory ability is more strongly linked to grammatical ability for children with WBS than for typically developing children. Receptive concrete vocabulary is the strongest area of language ability, and receptive conceptual/relational language is the weakest area. Both are strongly related to other aspects of intellectual ability (Refs Reference Mervis, Morris, Mazzocco and Ross20, Reference Mervis58). Although articulation abilities have not been explicitly studied for children with WBS, by the early school years the speech of most children with WBS is easy to understand. Individuals with WBS have significant pragmatic difficulties not only as very young children but also as adolescents and adults, even though by then their expressive language is typically grammatically correct and they have good concrete vocabularies.

Genotype–phenotype correlation

People with WBS

Unequal meiotic recombination between flanking repeats at 7q11.23 results in the hemizygous deletion of the same chromosome interval in almost all people with WBS. This interval spans at least 26 genes, although it is unlikely that all are contributing to the WBS phenotype, since not all genes are dosage-sensitive. Elastin is known to be the culprit for symptoms affecting elastic tissues, primarily causing cardiovascular stenoses and likely contributing to hypertension, diverticuli and the hoarse voice (Ref. Reference Curran59). Point mutations of the elastin gene (ELN) have been identified in numerous cases with supravalvular aortic stenosis, but none of the additional, characteristic WBS features was present in these individuals (Refs Reference Li60, Reference Tassabehji61, Reference Metcalfe62). Further insight into which genes might be most important in the genetic basis of WBS has come from the study of a handful of individuals with smaller than usual deletions of 7q11.23. Individuals who have short deletions that include the common telomeric breakpoint appear to have classic WBS (Refs Reference Botta63, Reference Heller64), whereas many others exhibit only a few features of WBS and have a variety of smaller deletions, all including ELN (Refs Reference Frangiskakis65, Reference Tassabehji66, Reference Gagliardi67, Reference Hirota68, Reference Morris69, Reference Tassabehji70, Reference Howald71, Reference Tassabehji72, Reference van Hagen73). From these partial deletion cases, researchers have argued that LIMK1 (encoding LIM domain kinase 1) is involved in the visuospatial construction difficulties associated with WBS (Refs Reference Frangiskakis65, Reference Morris69; but see Ref. Reference Tassabehji66), that CLIP2 (encoding CAP-GLY domain containing linker protein 2) hemizygosity contributes to problems with motor coordination (Ref. Reference van Hagen73), that GTF2IRD1 (encoding GTF2I repeat domain containing 1) is important for proper craniofacial development (Ref. Reference Tassabehji70) and that GTF2I (encoding general transcription factor II, I) (at the telomeric end of the deletion) is involved in the general intellectual disability/mental retardation (Ref. Reference Morris69) and/or visuospatial construction difficulties (Refs Reference Gagliardi67, Reference Hirota68, Reference Tassabehji70, Reference Edelmann74) associated with WBS.

Mouse models of WBS

In an attempt to understand more about the function of each of the genes from the WBS commonly deleted region, investigators have utilised mouse models. Several knock-out models have been generated and characterised, and some have semi-dominant phenotypes that suggest the gene may be haploinsufficient in WBS (Refs Reference Li75, Reference Hoogenraad76, Reference Meng77). Mice heterozygous for Clip2, for instance, show impairment in motor tasks, hippocampal dysfunction, and mild growth deficiencies, all of which are also seen in WBS (Refs Reference Meyer-Lindenberg, Mervis and Berman24, Reference van Hagen73, Reference Hoogenraad76). Studies of mice, although helpful, raise important questions about the parallels between humans and model organisms. Genes that are haploinsufficient in humans might not be so in mice, as a result of functional redundancy or the presence of alternative biological pathways. In addition, studies of characteristics such as language, emotion and behaviour can be extremely difficult in organisms other than humans, for obvious reasons.

Brain-imaging studies of individuals with WBS

Structural magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) studies, comparing adults with WBS who have normal intelligence to a group of CA- and IQ-matched adults in the general population, have indicated three regions in which there is reduced grey matter in WBS: in the intraparietal sulcus, the orbitofrontal cortex, and the region around the third ventricle (Ref. Reference Meyer-Lindenberg78). The same reduced grey matter region has been identified in the intraparietal sulcus in children with WBS (Ref. Reference Boddaert79). Reductions in intraparietal sulcus depth have been identified in individuals with WBS who have normal IQ (Ref. Reference Kippenhan80) as well as in individuals with WBS who have intellectual disability (Ref. Reference American Academy of pediatrics committee on Genetics D.C.81). Path analyses using data from functional MRI studies of individuals with WBS and normal IQ, and an IQ-matched contrast group of individuals in the general population, have implicated the intraparietal sulcus in the visuospatial construction difficulties characteristic of individuals with WBS (Ref. Reference Meyer-Lindenberg78), and have linked the reduced grey matter region in the orbitofrontal cortex with the hypersociability and non-social specific phobia characteristic of WBS (Ref. Reference Meyer-Lindenberg82). Meyer-Lindenberg et al. (Ref. Reference Meyer-Lindenberg78) hypothesised that the reduced grey matter region around the third ventricle may be associated with the hormonal disturbances characteristic of WBS (Refs Reference Morris, Morris, Lenhoff and Wang19, 83, Reference Cherniske84). Multimodal imaging studies of the hippocampal formation indicated that although any structural changes were minimal, functional changes were significant. Positron emission tomography (PET) imaging indicated that baseline neurofunctional status was profoundly reduced. Proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy also indicated a reduced ratio of N-acetyl aspartate to creatine, indicating overall reduction in hippocampal energy metabolism and synaptic activity (Ref. Reference Meyer-Lindenberg85). For a review of neuroimaging studies in WBS, see Ref. Reference Meyer-Lindenberg, Mervis and Berman24.

Duplication of 7q11.23

Although duplication of the WBS region had been predicted to occur at a similar frequency to deletion (based on the mechanism of rearrangement), duplications of this region were identified only recently. Hypotheses for the apparent lack of duplications were lethality, an absence of phenotypic consequence, or a clinical presentation that was unlike WBS, making screening of an appropriate patient population impossible. It turned out that the third hypothesis was correct, and that duplication of 7q11.23 results in a nonoverlapping clinical phenotype, with severe speech and expressive-language delay being the most prominent feature.

An initial paper describing the discovery of an 8-year-old boy with exact duplication of the WBS region reported that the most striking aspect of the phenotype was the severe delay in speech and expressive language, an area that is relatively spared in individuals with WBS compared with overall intellectual abilities (Ref. Reference Somerville4). The boy was able to correctly pronounce only a very small number of words, but scored at a much higher ability level on receptive vocabulary and on nonlanguage tasks.

Individuals with larger chromosome 7 duplications that include 7q11.23 also present with speech and language impairment, along with mild developmental delay (Refs Reference Tassabehji72, Reference Tan-Sindhunata86, Reference Velagaleti87, Reference Chantot-Bastaraud88, Reference Lichtenbelt89, Reference von Beust90, Reference Berg91). A review of these reported patients also suggests the presence of a subtle but recognisable facial phenotype, consisting of a high broad nose, posteriorly rotated ears, high arched palate and short philtrum. Since the initial report, eight additional children with a reciprocal duplication of the WBS region have been reported (Table 1; individuals with supernumerary ring chromosome 7 that includes the WBS locus are also described). Although only scant information concerning their phenotypic presentation is available for six of these cases, all have been diagnosed with speech delay (Refs Reference Berg91, Reference Golden92, Reference Jayakar93, Reference Kriek94, Reference Kirchhoff95, Reference Torniero96, Reference Depienne97). These duplication cases were identified during screens for copy number changes in regions of the genome known to undergo frequent rearrangements. The children were all part of cohorts with developmental delay, except one who was identified in a cohort with autism spectrum disorder. Developmental delay has been seen in each of the identified individuals with 7q11.23 duplication, suggesting it is likely part of the phenotype associated with this chromosome rearrangement.

Table 1 Phenotypic characteristics of 7q11.23 duplication, showing common feature of expressive-language and speech delay

aAll cases of supernumerary ring chromosome 7 reported in this table have confirmed duplication of the WBS region. bNo information on language ability reported. cBased on observation rather than formal assessment. No verbal or overall IQ reported. dNo information reported re speech acquisition. eNo verbal or overall IQ reported. fToo young to evaluate for language delay. Abbreviations: ADHD, attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder; CHD, congenital heart disease; DD, developmental delay; LD, learning disability; NA, not available.

Speech and language abilities in children with 7q11.23 duplication

The five children with 7q11.23 duplication for whom published data are available [Refs Reference Somerville4, Reference Kriek94, Reference Kirchhoff95, Reference Torniero96, Reference Depienne97; four other cases have been reported in conference proceedings (Refs Reference Berg91, Reference Golden92, Reference Jayakar93)], have been characterised as having developmental delay, with greater delay in speech and expressive language than in general intellectual abilities. More detailed information was reported for three of the children. At age 8 years 10 months, the child reported by Somerville et al. (Ref. Reference Somerville4) was able to pronounce only a few words correctly. He communicated by a combination of vocalisations (including a number of words that family members were able to understand even though they were not clear to people who were not familiar with his speech), gestures, pantomime, manual signs, and drawing. Unlike children his age who have WBS, this child rarely produced word combinations. His performance on tests of expressive language was at floor (lowest possible standard score), although he performed in the low average range on tests of receptive vocabulary. His drawing ability was considerably stronger than that of children his age with WBS. He had good social interaction skills. Both he and his sister had ADHD; his parents were also reported to have had ADHD as children.

The child studied by Torniero et al. (Ref. Reference Torniero96) was identified with severe speech and language delay at age 4 years. At age 8 years, she was able to pronounce bisyllabic words but showed some consistent phonological substitutions. Testing indicated that she did not have orofacial apraxia. At age 12 years, she pronounced bisyllabic words correctly but only rarely produced multiword combinations. Overall intellectual functioning was in the range of moderate intellectual disability, with drawing ability stronger than verbal ability. Receptive vocabulary was in the range of mild disability. Spatial memory ability was in the low average range; in contrast, verbal memory ability was in the range of moderate to severe disability. She had good social interaction skills and did not have ADHD.

The child studied by Depienne et al. (Ref. Reference Depienne97) was found to have 7q11.23 duplication based on a screening for 7q11 rearrangements conducted on 206 individuals with autism spectrum disorder. This child was considerably more disabled than the previously identified individuals. He had severe intellectual disability, ADHD, severe speech delay, and talked in single words that were unintelligible out of context, although the language he did have was usually used appropriately. Although the speech and language characteristics of this child were similar to those of other individuals with 7q11.23 duplication, he had more severe intellectual disability, sudden outbursts of aggression (which were being treated with thioridazine), and hyperphagia, and had been diagnosed with autism – all characteristics that had not been reported previously for individuals with 7q11.23 duplication. This pattern suggests that this child may also have an additional genetic disorder.

MRI, electroencephalogram (EEG) and audiometry findings are available for all three children. The child studied by Torniero et al. (Ref. Reference Torniero96) had a normal EEG at age 4 years. However, at age 12 years she began having partial seizures, which were controlled by medication within a few months. At 13 years, structural MRI revealed cortical dysplasia of the left temporal lobe. Audiometry revealed normal hearing. The child reported by Depienne et al. had an MRI that showed mild dilatation of the left temporal horn and a small arachnoid cyst in the temporal fossa (Ref. Reference Depienne97). EEG recordings were inconclusive, with unstructured rhythms but no synchronised activity. Audiometry indicated normal hearing at 18 months of age. The child studied by Somerville et al. had a structural MRI at age 6 years and an EEG at age 7 years; no significant abnormalities were found on either (Ref. Reference Somerville4; supplementary appendix). Results of behavioural audiometry and otoacoustic emmisions indicated normal hearing (Ref. Reference Somerville4). Neuroimaging studies of additional children with duplications of the WBS region are needed to determine if the findings of Torniero et al. (Ref. Reference Torniero96) and/or Depienne et al. (Ref. Reference Depienne97) are typical for individuals with 7q11.23 duplication.

Implications for understanding speech and language development

Developmental speech/language impairments are estimated to affect 3–10% of children and have been shown to be highly heritable (Ref. Reference Bishop98). A study of 2-year-olds found a heritability of 0.73 (Ref. Reference Dale99) and twin studies have reported monozygotic concordance of 70% and dizygotic concordance of 45% (Refs Reference Lewis and Thompson100, Reference Bishop, North and Donlan101, Reference Tomblin and Buckwalter102) (for a single gene disorder with complete penetrance, monozygotic concordance would be 1.0 and dizygotic concordance 0.5). The underlying genetic bases for the majority of cases of speech/language impairments have been postulated to be complex, involving several loci that interact with each other and the environment to produce an overall susceptibility (Ref. Reference Fisher, Lai and Monaco103). Linkage analysis has identified several possible contributing loci (Refs 104, 105), but so far only a single gene – the transcription factor FOXP2 on chromosome 7q31 – has been implicated in the aetiology of developmental speech/language impairments, and only in a few cases (Refs Reference Lai106, Reference MacDermot107, Reference Feuk108, Reference Shriberg109, Reference Zeesman110, Reference Lennon111). Disruption of FOXP2 results in reduced functional dosage and produces deficits in both expressive and receptive language in addition to orofacial dyspraxia that impairs the coordination of complex fine motor movements of the lower face for speech and nonspeech purposes (Ref. Reference Lai106).

The recent identification of individuals with an exact duplication of the WBS region and severe speech and language delay defines 7q11.23 as a new locus for expressive language disorder and speech impairment (Refs Reference Somerville4, Reference Kriek94, Reference Kirchhoff95, Reference Torniero96, Reference Depienne97). Although the common duplication interval spans at least 26 genes, it might be predicted that, as is the case with deletions of the region in WBS, only one or a few of these genes are playing a prominent role in the language-impairment phenotype. The prospect of evaluating two dozen genes, rather than the 40 000 or so in the entire human genome is certainly appealing. In addition, we might also expect to identify individuals with smaller duplications of the region that will enable genotype–phenotype correlation and narrow the critical interval even further. Since research into 7q11.23 duplication is in its infancy, there are no clues as to which gene(s) are likely to be implicated at this time. Analysis of gene expression in lymphocytes from one child with a 7q11.23 duplication revealed increased expression of all but one gene from the duplicated interval (Ref. Reference Somerville4).

Finding the gene(s) responsible for this expressive-language and speech impairment will shed new light on the molecular genetics of speech and language and on the physiological basis of expressive language. Although the children with 7q11.23 duplication identified so far have not undergone detailed orofacial movement and oral praxis testing, they do not appear to show any obvious problem with motor coordination of the lower face muscles or tongue, although mild gross motor coordination difficulties were reported in some. This is in contrast to most patients with disruption of FOXP2, who have problems with sneezing, throat clearing and coughing and are sometimes unable to blow their noses (Refs Reference Lai106, Reference Feuk108, Reference Zeesman110). Other reported oromotor problems arising from FOXP2 disruption include difficulties with lip protrusion, tongue elevation and lateralisation, and rapid alternating movements, as well as difficulties with chewing, gagging and swallowing in their early years (Refs Reference Feuk108, Reference Zeesman110). The underlying basis for expressive-language impairment in children with 7q11.23 duplication is, therefore, potentially unrelated to that in children with FOXP2 disruption.

The study of WBS is unlikely to be as fruitful as the study of 7q11.23 duplication syndrome for advancing our understanding of the genetics of language impairment. Although the language abilities of most children with WBS are lower than would be expected for their CA, these abilities are typically at or slightly above the level that would be expected for their overall intellectual ability (Refs Reference Mervis and Becerra6, Reference Mervis, Morris, Mazzocco and Ross20). Individuals with shorter deletions that do not include GTF2I typically have stronger language abilities than individuals with classic WBS deletions. However, the overall intellectual ability of individuals with shorter deletions that do not include GTF2I is also considerably higher than that of individuals with classic WBS deletions; performance is higher not only for language but also for nonverbal reasoning and for visuospatial construction, suggesting that the stronger language abilities are probably related to the higher level of general intellectual ability rather than reflecting an independent improvement in language (Refs Reference Morris69, Reference van Hagen73).

Research in progress and outstanding research questions

Although the frequency of 7q11.23 duplication is estimated at between 1 in 7500 and 1 in 20 000 live births based on the frequency of 7q11.23 deletion, the actual number of children carrying this genomic rearrangement remains unknown. Furthermore, the usual or ‘classic’ clinical presentation has not yet been established, because of the small number of individuals identified so far. It is not known whether a severe delay in speech and expressive language is always associated with 7q11.23 duplication, or whether some level of developmental delay is always present. The answers to these phenotypic questions will not become available until a much larger number of children with the duplication have undergone detailed developmental assessment. Since children with 7q11.23 duplications have received a primary diagnosis of speech and expressive-language delay, and of developmental delay, individuals with either of these diagnoses are the focus of duplication-screening efforts.

To dissect the molecular basis for language impairment in children with 7q11.23 duplication, it will probably be necessary not only to use genotype–phenotype comparisons in humans but also to utilise animal models. Since we would predict that it is the overexpression of a particular gene(s) that is contributing to the speech and expressive language delay, increasing the dosage of candidate genes in the mouse may help uncover the precise genetic basis. This can be done either by duplicating the same set of genes, which conveniently lie together in the same order on mouse chromosome 5, or by adding individual genes one at a time. It may seem strange to consider modelling a speech disorder in an animal, but such models present attractive tools for understanding the neurogenetic and physiological mechanisms by which developmental speech/language impairments arise. They also provide access to vital information about the temporal and spatial expression of genes and allow us to study the development of neural networks both in the normal state and in genetically manipulated models of the human condition.

The Foxp2 gene has been disrupted in a mouse model of developmental dyspraxia, with fascinating results. Neonatal pups homozygous for the Foxp2 disruption showed a complete absence of ultrasonic vocalisation on being separated from their mother, along with severe motor impairment and premature death, while pups heterozygous for the disruption (as is the case in humans with FOXP2 disruption) showed significantly reduced vocalisation (Ref. Reference Shu112). Clues to the origin of the phenotype in these mice included cerebellar abnormalities such as a disorganised Purkinje cell layer and abnormal migration of granule-cell progenitors.

By combining studies in humans and animal models, it will be possible to identify the genetic basis for speech and expressive-language delay that resides at 7q11.23, and to understand more about the physiological and neurological processes that mould speech and language development. Should 7q11.23 duplication prove to contribute significantly to the aetiology of speech and expressive-language delay, testing for this genomic arrangement in children with a characteristic phenotype can be easily integrated into the existing molecular genetics screening panel, allowing for earlier diagnosis and implementation of intensive speech and language therapy.

Acknowledgements and funding

The authors' research is supported by grants from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (L.R.O), Sick Kids Foundation (L.R.O), Genome Canada/Ontario Genomics Institute (L.R.O), the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (R01 NS35102 – C.B.M) and the National Institute of Child Health and Development (R37 HD29957 – C.B.M).