Folates are a family of B9 vitamins that play a critical role in key biosynthetic processes in mammalian cells. These one-carbon donors are required for purine nucleotide and thymidylate synthesis and hence, are essential for the de novo production of RNA and DNA. Folates are also required for vitamin-B12-dependent synthesis of methionine, a precursor of S-adenosylmethionine, which is required for methylation of DNA, histones, lipids and neurotransmitters (Ref. Reference Stokstad, Picciano and Stokstad1). Mammalian cells, unlike bacteria, do not have the metabolic machinery to synthesise folates. Hence, folate requirements must be met entirely from dietary sources. Traditionally, folates were derived from foods such as liver and dark green leafy vegetables. The recent commercial fortification of cereals, grains and bread with folic acid now represents an important source of folates. This has resulted in a rise in folate levels in tissues and blood (Ref. Reference Jacques2). Because of the hydrophilic nature of the charged folate molecule, there is minimal passive diffusion across cell membranes. Rather, highly specific transporters are required to mediate intestinal folate absorption and the transport of folates into systemic tissues. However, despite the importance of these vitamins and their membrane transport, aspects of folate physiology, particularly relating to their transport, were uncharacterised and/or misunderstood until recently.

There is considerable information, acquired over many decades, regarding the properties of two folate transporters. (1) The reduced folate carrier (RFC; official gene symbol SLC19A1), a member of the superfamily of solute carriers, is an anionic exchanger and a major route of delivery of folates to systemic tissues at physiological pH (Refs Reference Matherly and Goldman3, Reference Matherly, Hou and Deng4). (2) Two folate receptors (FRα and FRβ), embedded in the cell membrane by a glycosylphosphoinositol (GPI) anchor, transport folates via receptor-mediated endocytosis at neutral to mildly acidic pH (Refs Reference Kamen and Smith5, Reference Salazar and Ratnam6). Recently, a third folate transporter was identified – the proton-coupled folate transporter (PCFT; SLC46A1). PCFT also belongs to the superfamily of solute carriers and functions optimally at low pH (Refs Reference Qiu7, Reference Zhao and Goldman8). PCFT accounts for the low-pH folate transport activity in many normal and malignant tissues, most notably the small intestine. The critical role that PCFT plays in intestinal folate absorption was established by the demonstration of loss-of-function mutations in this gene in patients with hereditary folate malabsorption (HFM) (Refs Reference Qiu7, Reference Zhao9, Reference Min10).

Structural analogues of folate compounds have been used for treating cancer and autoimmune diseases (Refs Reference Wessels, Huizinga and Guchelaar11, Reference Zhao and Goldman12). These include methotrexate and, more recently, pemetrexed, (Refs Reference Zhao and Goldman12, Reference Chattopadhyay, Moran and Goldman13). These agents utilise the same transporters as physiological folates to enter tumour cells. Transport is an important determinant of antifolate activity, and impaired transport is a key mechanism of drug resistance (Refs Reference Zhao and Goldman12, Reference Chattopadhyay, Moran and Goldman13). This review considers how these three transport systems contribute both individually and collectively to folate homeostasis in man and to delivery of antifolates in the treatment of cancer.

Tetrahydrofolate cofactors: interconversions and utilisation in folate-dependent biochemical reactions

The folate molecule consists of a pteridine moiety with A and B rings linked at carbon 6 by a methylene bridge to p-aminobenzoylglutamic acid (Fig. 1). ‘Folate’ is a generic term for members of the B9 family of vitamins and will be used as such in this review. The parent structure is folic acid, a pharmacological agent not found in nature. Because of its stability, folic acid has been used as a folate source in cell culture medium and in vitamins; within cells, it is reduced at the B ring, first to dihydrofolate (DHF) and then to tetrahydrofolate (THF) (Fig. 1). Folic acid is also used to discriminate between folate transport routes, for which it has markedly different affinities. THF is a good substrate for the enzyme, folylpolyglutamate synthetase (FPGS), which progressively adds glutamate molecules at the gamma carboxyl residue through an amide bond to form glutamate-peptide chains of varying length (Fig. 1). THF polyglutamates associate with methyl, formyl, methylene or methenyl one-carbon moieties at the N5 and/or N10 positions, which serve as one-carbon donors in biosynthetic reactions (Ref. Reference Stokstad, Picciano and Stokstad1). The folate polyglutamate derivatives are, with few exceptions, the preferred substrates for one-carbon transfer reactions over their nonpolyglutamate (hereafter, designated ‘monoglutamate’) precursors (Ref. Reference Shane14).

Figure 1. Structures of representative folate compounds. (a) Folic acid is reduced to dihydrofolic acid at positions 7 and 8 of the B ring, which is in turn reduced to tetrahydrofolic acid at positions 5 and 6 in reactions mediated by dihydrofolate reductase (DHFR). Endogenous folic acid is not found in cells; its presence is related to the consumption of folic acid added to cereals, grains and vitamins. The major oxidised folate in cells is dihydrofolic acid. 5-Methyltetrahydrofolic acid (5-methylTHF) is the major dietary form and the dominant folate found in blood. It is formed endogenously by the reduction of 5,10-methylene-tetrahydrofolic acid (5,10-methyleneTHF). Tetrahydrofolate (THF) is generated upon utilisation of 5-methylTHF in methionine synthesis and 10-formylTHF in purine synthesis. These relationships are depicted in Figure 2. The two carboxyl groups of the glutamate moiety are fully ionised at physiological pH. (b) Structure of 5-methylTHF tetraglutamate, which is one of the 5-methylTHF forms found in nature and in mammalian cells. It is a polyanion and a very poor substrate for folate transporters and multidrug-resistance-associated proteins.

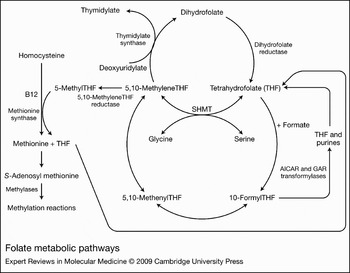

The predominant natural folate in the diet and blood of humans and rodents is 5-methylTHF (Fig. 1). Utilisation of this form in cells begins with the transfer of a methyl group to homocysteine, in a vitamin-B12-dependent reaction mediated by methionine synthase, to form methionine (Fig. 2). The unsubstituted THF released then reacts with formate (via 10-formylTHF synthetase) to produce 10-formylTHF, which donates two carbons to the synthesis of the purine ring in reactions mediated first by β-glycinamide ribonucleotide (GAR) transformylase and then by 5-amino-4-imidazolecarboxamide ribonucleotide (AICAR) transformylase. 10-FormylTHF also undergoes dehydration to 5,10-methenylTHF, which in turn is reduced to 5,10-methyleneTHF. 5,10-MethyleneTHF is also formed from THF by serinehydroxymethyltransferase, which interconverts serine to glycine. 5,10-MethyleneTHF is reduced in an irreversible reaction by 5,10-methyleneTHF reductase (MTHFR) to 5-methylTHF. 5,10-MethyleneTHF is required for de novo synthesis of thymidylate, catalysed by thymidylate synthase, in which a one-carbon moiety is transferred to deoxyuridylate along with a reducing equivalent from the pteridine B ring. This results in oxidation of the THF moiety to DHF. Because of its rapidity and irreversibility, this reaction has the potential to deplete cellular THF cofactors, which rapidly interconvert to 5,10-methyleneTHF by mass action as this folate is oxidised to DHF. However, THF cofactor levels are maintained because of the rapid reduction of DHF to THF, mediated by dihydrofolate reductase (DHFR) (Fig. 2). When DHFR is inhibited by methotrexate, aminopterin or the more recently developed drug PT523, there is rapid interconversion of THF cofactors to DHF, resulting in cessation of one-carbon-dependent processes (Refs Reference Zhao and Goldman12, Reference Matherly15, Reference Seither16).

Figure 2. Folate metabolic pathways. 5-MethylTHF enters the metabolic cycle following transport into cells where, with homocysteine, it is utilised in the synthesis of methionine mediated by methionine synthase and vitamin B12. The tetrahydrofolate (THF) product then acquires a carbon from formate or serine, at the N5 or N10 positions, which, through a series of interconversions, results in several other folate forms that provide carbons for purine, thymidylate and methionine synthesis. Abbreviations: AICAR, 5-amino-4-imidazolecarboxamide ribonucleotide; GAR, β-glycinamide ribonucleotide; SHMT, serinehydroxymethyltransferase.

The folate transporters

The reduced folate carrier

RFC (SLC19A1) was the first folate transporter described at the kinetic and thermodynamic levels (Refs Reference Matherly and Goldman3, Reference Goldman, Lichtenstein and Oliverio17, Reference Goldman and Matherly18, Reference Sirotnak and Tolner19). The gene that encodes human RFC (SLC19A1) is located on chromosome 21q22.3. The K m for 5-methylTHF, 5-formylTHF and methotrexate influx mediated by RFC is in the 2–7 µM range; the K m for PT523 is much lower. RFC has a very low affinity for folic acid (K i ~150–200 µM). The high affinity of RFC for PT523, its very low affinity for folic acid, and its neutral pH optimum clearly distinguish this carrier from PCFT. Methotrexate is frequently used to characterise RFC-mediated transport because it is not metabolised over short intervals and because of the ease and accuracy of influx determinations and distinguishing between free and tightly bound drug within cells (Ref. Reference Goldman, Lichtenstein and Oliverio17).

RFC generates only small transmembrane chemical gradients. However, folates are negatively charged because of the two glutamate carboxyl groups that are fully ionised at physiological pH (Fig. 1). When this is considered within the context of the membrane potential, RFC actually produces a substantial electrochemical potential difference for folates across cell membranes (Ref. Reference Goldman, Lichtenstein and Oliverio17). The energy source for this uphill process is unique. RFC function is not directly linked to ATP hydrolysis and it is neither Na+- nor H+-dependent (Refs Reference Henderson and Zevely20, Reference Goldman21). Rather, RFC-mediated transport is highly sensitive to the transmembrane anion gradient, in particular, the organic phosphate gradient (Refs Reference Henderson and Zevely20, Reference Goldman21). Organic phosphates are highly concentrated in cells where they are synthesised in ATP-dependent reactions and are largely retained. Their resulting asymmetrical distribution across cell membranes provides the driving force for RFC-mediated uphill transport of folates into cells (Ref. Reference Goldman21).

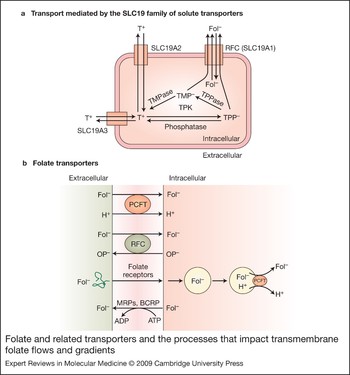

The most substantive support for this model comes from studies on thiamine transport and metabolism. There are two other members of the SLC19 family, SLC19A2 and SLC19A3, with ∼40% homology to RFC (Refs Reference Labay22, Reference Fleming23, Reference Diaz24, Reference Dutta25, Reference Rajgopal26). However, both are thiamine – not folate – transporters. Neither does RFC transport thiamine. However, after thiamine is transported into cells, it is converted to thiamine pyrophosphate and thiamine monophosphate (Ref. Reference Rindi and Laforenza27); both are transported by RFC (K i values of ∼25 µM and 32 µM, respectively) (Refs Reference Zhao28, Reference Zhao, Gao and Goldman29). When cells are exposed to thiamine, these phosphorylated derivatives accumulate intracellularly. However, the higher the level of RFC expression, the lower the level of cellular accumulation of thiamine pyrophosphate, because of enhanced export mediated by RFC. Likewise, when cells are loaded with methotrexate, accumulation of the phosphorylated derivatives of thiamine is enhanced as a result of methotrexate inhibition of their export by RFC (Ref. Reference Zhao28). These observations can only be explained if methotrexate and phosphorylated derivatives of thiamine use the same carrier – RFC. These interactions between thiamine, its phosphorylated derivatives and folates are illustrated in Figure 3a.

Figure 3. Folate and related transporters and the processes that impact transmembrane folate flows and gradients. (a) Transport mediated by the SLC19 family of solute transporters. Thiamine (T+), a cation, is transported into cells via SLC19A2 and SLC19A3. Within cells, thiamine is metabolised to thiamine pyrophosphate (TPP−), an anion, in a reaction mediated by thiamine pyrophosphate kinase (TPK). TPP− can be hydrolysed to thiamine monophosphate (TMP−), also an anion, mediated by thiamine pyrophosphatase (TPPase). Both are substrates for the reduced folate carrier (RFC; SLC19A1) and are exported by that mechanism. Folates enter cells via RFC and are not substrates for the thiamine transporters. Likewise, thiamine is not a substrate for RFC. (b) Folate transporters. The proton-coupled folate transporter (PCFT) is a folate (Fol−)–H+ symporter that functions most efficiently in an acidic extracellular environment. The reduced folate carrier (RFC) is an anion exchanger that utilises the transmembrane organic phosphate (OP−) gradient to achieve uphill transport into cells. Folate receptors FRα and FRβ are high-affinity folate-binding proteins that transport folates into cells via an endocytic mechanism. Once in the cytoplasm, the vesicle acidifies, folate is release from the receptor, and is exported from the endosome by a mechanism proposed to be mediated at least in part by PCFT. Folate monoglutamates are exported from cells via the multidrug- resistance-associated proteins (MRPs) and the breast-cancer-resistant protein (BCRP).

Additional evidence for utilisation of RFC by structurally unrelated anions comes from the observation that folate influx is enhanced in RFC-containing membrane vesicles by phosphate or sulfate in the trans compartment (Ref. Reference Yang, Sirotnak and Dembo30). Likewise, depletion of extracellular anions impairs efflux of folates from cells; an activity that is restored when extracellular anions such as thiamine pyrophosphate, AMP or phosphate are added (Ref. Reference Henderson and Zevely20).

Thus, RFC is not influenced by the cellular energy charge, per se. Indeed, inhibition of anaerobic or aerobic metabolism resulting in ATP depletion enhances rather than diminishes the transmembrane folate gradient mediated by RFC (Refs Reference Goldman31, Reference Fry, White and Goldman32, Reference Dembo, Sirotnak and Moccio33). This is probably due to (1) inhibition of ATP-binding-cassette proteins that export folates and oppose the concentrative impact of RFC (Ref. Reference Kruh and Belinsky34), and (2) maintenance of the net transmembrane adenine nucleotide gradient, because ADP and AMP generated from ATP are more potent inhibitors of RFC-mediated folate transport than ATP (Refs Reference Henderson and Zevely20, Reference Goldman21).

RFC is characterised by 12 transmembrane domains (TMDs) and cytoplasmically oriented N- and C-termini (Refs Reference Cao and Matherly35, Reference Ferguson and Flintoff36, Reference Liu and Matherly37) (Fig. 4). Human RFC is N-glycosylated at an N-glycosylation consensus site in the loop connecting TMD1 and TMD2 (Asn58) (Ref. Reference Wong38). A large loop domain that connects TMD6 and TMD7 is poorly conserved between species and can be replaced altogether by a nonhomologous segment from the SLC19A2 carrier (Ref. Reference Liu, Witt and Matherly39). When separate TMD1–TMD6 and TMD7–TMD12 RFC half-molecules are coexpressed in human RFC-null cells, they are targeted to the plasma membrane surface and restore transport activity (Ref. Reference Witt, Stapels and Matherly40). Hence, the role of the TMD6–TMD7 loop domain is primarily to provide appropriate spacing between the TMD1–TMD6 and TMD7–TMD12 segments for optimal transport.

Figure 4. Gene structure and membrane topology of the reduced folate carrier. (a) Schematic of the upstream region of SLC19A1, the human gene encoding the reduced folate carrier (RFC). There are six alternative noncoding regions, each preceded by a separate promoter, spanning ∼35 kb upstream of the major translation start site. The alternative promoters transcribe unique RFC transcripts, each with a distinct 5′ untranslated region (5′UTR) fused to a common coding sequence. Alternative splicing for the A1/A2, A, B and D 5′UTRs has been described. For the A1/A2 and A 5′UTRs, upstream AUG start codons occur in-frame within the RFC noncoding sequence and result in N-terminally modified RFC protein isoforms, with 64 and 22 additional N-terminal amino acids, respectively. (b) Membrane topology of the human RFC including 12 transmembrane domains (TMDs), internally oriented N- and C-termini, the large cytosolic loop between TMD6 and TMD7 and the N-glycosylation site at Asn58.

Studies with RFC mutants implicated conserved amino acids in TMD1, TMD2, TMD3, TMD4, TMD8, TMD10 and TMD11 as important for transport (Ref. Reference Matherly, Hou and Deng4), and recent results with N-hydroxysuccinimide [3H]methotrexate radioaffinity labeling localised binding of the substrate γ-carboxyl group to Lys411 in TMD11 of hRFC (Ref. Reference Deng41). By exhaustive cysteine-scanning mutagenesis and accessibility to membrane-impermeable thiol-reactive agents of a ‘cysteine-less’ human RFC molecule, amino acids localised in TMD4, TMD5, TMD7, TMD8, TMD10 and TMD11 were implicated in forming the putative substrate-binding pocket (Refs Reference Hou42, Reference Hou43). This is consistent with crystal structures for the bacterial MFS proteins, LacY and GlpT (Refs Reference Abramson44, Reference Huang45).

RFC is ubiquitously expressed with patterns of localisation (in intestine, hepatocytes, renal epithelial cells, choroid plexus) that have suggested its integral role in specialised tissues that are important for in vivo folate homeostasis (Refs Reference Whetstine, Flatley and Matherly46, Reference Liu47). Human RFC is intricately regulated by transcriptional controls involving as many as six alternative promoters and noncoding regions that generate up to 15 distinct 5′ untranslated regions (UTRs) fused to a common coding sequence (Ref. Reference Matherly, Hou and Deng4) (Fig. 4). The net level of RFC transcripts among different tissues probably results from both ubiquitous (Sp, USF) and tissue-specific (Ap1, C/EBP) transcription factors which, when combined, transactivate or repress transcription in response to tissue-specific stimuli. Other factors that are probably important in the regulation of this gene include promoter methylation, general promoter architecture and chromatin structure (Ref. Reference Matherly, Hou and Deng4).

The diverse human RFC 5′UTRs are subject to post-transcriptional controls, including effects on 5′CAP-dependent translation and transcript stabilities (Ref. Reference Payton48). For many 5′UTRs, the effects on steady-state RFC gene transcripts and proteins are subtle and can be overshadowed by differences in promoter activities. However, for noncoding exons A1/A2, A and D, there were profound decreases in steady-state hRFC compared with other 5′UTRs (Ref. Reference Payton48). For the A1/A2 and A 5′UTRs, upstream AUGs occur in-frame within the SLC19A1 coding sequence and result in N-terminally modified RFC protein isoforms, with 64 and 22 additional N-terminal amino acids, respectively (Refs Reference Payton48, Reference Flatley49). The biological significance of these modified RFC proteins is unclear.

High-frequency polymorphisms have been described in RFC involving both the coding region (G80A) and promoters A1/A2 and A (Refs Reference Flatley49, Reference Chango50, Reference Whetstine51, Reference Whetstine, Witt and Matherly52). G80A RFC is associated with an increased risk of fetal abnormalities (Refs Reference De Marco53, Reference Morin54) and methotrexate toxicity in patients with acute lymphoblastic leukaemia (Ref. Reference Laverdiere55). However, the clinical significance of G80A remains controversial (Refs Reference Matherly, Hou and Deng4, Reference Matherly56). The presence of a 61-bp-repeat polymorphism in the SLC19A1 A promoter may protect against neural tube defects (Ref. Reference O'Leary57).

The proton-coupled folate transporter

The proton-coupled folate transporter (PCFT) is a recently discovered folate carrier (SLC46A1) (Refs Reference Qiu7, Reference Nakai58, Reference Umapathy59). There are two other members of this family (SLC46A2 and SLC46A3) but their functions are not known. The gene that encodes human PCFT (SLC46A1) is located on chromosome 17q11.2. PCFT was initially reported to be a low-affinity haem transporter (influx K m of 125 µM) that is pH independent. It was designated as haem carrier protein-1 (HCP1), which mediates haem-associated iron absorption in the small intestine (Ref. Reference Shayeghi60). However, although haem is a weak inhibitor of folate transport in mammalian cells, a haem current could not be detected in Xenopus oocytes injected with PCFT cRNA and neither haem nor haemin inhibited folate currents in oocytes. (Refs Reference Qiu7, Reference Nakai58, Reference Umapathy59). At this point, the role that PCFT might play in haem transport is unclear. What is clear is that PCFT is a high-affinity folate transporter with a low pH optimum. Its identification now explains the molecular basis for the long-recognised low pH folate transport activities in normal and malignant mammalian cells (Refs Reference Zhao and Goldman8, Reference Henderson and Strauss61, Reference Zhao62, Reference Kuhnel, Chiao and Sirotnak63, Reference Sierra and Goldman64, Reference Assaraf, Babani and Goldman65).

Folate transport mediated by human, mouse and rat PCFTs is electrogenic, indicating that there is a net translocation of positive charges as each folate molecule is transported (Refs Reference Qiu7, Reference Umapathy59, Reference Qiu66, Reference Zhao67). Folate-induced currents in Xenopus oocytes microinjected with PCFT cRNA increase as the pH is decreased in parallel to increased transport of tritiated folates (Refs Reference Qiu7, Reference Qiu66). This is opposite to what is observed for RFC, where transport activity falls with decreasing pH from pH 7.4 and is negligible below a pH of 6.0–6.5 (Refs Reference Sierra68, Reference Wang, Zhao and Goldman69). If folates are bivalent anions, as is assumed to be the case, more than two protons must be co-transported with each folate molecule to account for the positive charge of the PCFT–folate–proton complex. Hence, PCFT functions as a folate–proton symporter: the downhill flow of protons via PCFT is coupled to the uphill flow of folates into cells (Fig. 3b). Early studies with rodent jejunal apical brush-border membrane vesicles provided insight into the energetics of what would later be recognised as PCFT-mediated transport. A transvesicular pH gradient resulted in increased unidirectional folate transport and substantial transmembrane folate concentration gradients, from the low-pH to the high-pH compartment, consistent with a proton-coupled process (Ref. Reference Schron, Washington and Blitzer70).

Although the substrate specificity for PCFT shares some similarity with RFC, there are important differences, including a marked difference in pH optima that impacts affinities for transport substrates. The RFC influx K m values are comparable at pH 7.4 and pH 5.5. The fall in transport with decreasing pH is due instead to a marked decrease in influx V max (Ref. Reference Wang, Zhao and Goldman69). By contrast, for PCFT, the influx K m for folates is increased and V max is decreased, upon an increase in pH from 5.5 to 7.4. However, the pattern and magnitude of these changes varies among different transport substrates (Ref. Reference Qiu7). Most notable is the relatively small change in influx K m and V max for pemetrexed, compared with other folates, with increasing pH. Because of this, PCFT mediates pemetrexed pharmacological effects at physiological pH (Refs Reference Qiu7, Reference Chattopadhyay, Moran and Goldman13, Reference Zhao67). Hence, like the divalent metal-ion transporter DMT1, PCFT mediates transport of folates in the absence of a proton gradient (Ref. Reference Mackenzie71). RFC and PCFT are both stereospecific for 5-formylTHF (Refs Reference Qiu7, Reference Sirotnak72).

The PCFT expression pattern in human tissues provides clues as to its functional roles. In murine and human tissues, there are high levels of SLC46A1 mRNA in small intestine, kidney, liver, placenta, retina and brain. Within the intestine, the highest PCFT levels are found in the proximal jejunum and duodenum (Refs Reference Qiu7, Reference Qiu66, Reference Inoue73).

Information on PCFT secondary structure is emerging. Hydropathy analyses predict a protein with 12 transmembrane domains and N- and C-termini oriented to the cytoplasm (Fig. 5). The latter was confirmed by immunofluorescence studies of haemagglutin-tagged PCFT (Refs Reference Qiu66, Reference Unal74). The loop domain between the first and second transmembrane domains must be extracellular, because the two putative N-glycosylation consensus sites in this region are glycosylated. N-glycosylation does not appear to be required for either PCFT trafficking or function (Ref. Reference Unal74).

Figure 5. Genomic organisation and predicted secondary structure of the proton-coupled folate transporter and mutations in patients with hereditary folate malabsorption. (a) Genomic organisation of SLC46A1, the gene encoding the proton-coupled folate transporter (PCFT); positions of the various mutations, as reported, in the first to fourth exons are indicated. (b) A schematic of a predicted human PCFT topology showing confirmed N-glycosylation sites (N58, N68) between the first and second transmembrane domains with the N- and C- termini oriented to the cytoplasm. The positions of reported mutations in the protein derived from patients with the autosomal recessive disorder hereditary folate malabsorption (HFM) are indicated.

Both RFC (Ref. Reference Liu47) and PCFT (Ref. Reference Qiu66) expression is markedly increased in the small intestine when mice are fed a folate-deficient diet. However, the underlying regulatory mechanisms for these changes await definition.

The impact of pH on the relative contributions of RFC and PCFT to folate transport: focus on intestinal folate absorption

The pH at the transport interface is an important determinant of the relative contributions of RFC and PCFT to overall folate uptake when these transporters are expressed at the same site in the same tissue, as is frequently the case. When the pH is 7.4, PCFT transport function is low to negligible (depending on the folate substrate) and RFC function is maximal. As the pH drops, RFC function decreases and PCFT activity increases. At some point, RFC transport disappears altogether and PCFT becomes the sole transport route (Refs Reference Qiu7, Reference Qiu66, Reference Wang, Zhao and Goldman69). From a physiological perspective, the critical transport interfaces where there is an acid pH include: (1) the microclimate of the duodenum and proximal jejunum apical brush-border membranes, where several Na+/H+ exchangers generate a pH of 5.8–6.0, and where folates are absorbed from the diet (Refs Reference Yun75, Reference McEwan76, Reference Ikuma77, Reference Said, Smith and Redha78); and (2) within acidified endosomes containing folate receptors (pH ∼6.0–6.5) from which, following internalisation from the cell surface, folates are exported into the cytoplasm (Ref. Reference Yang79). It is possible that there are other, as yet unidentified, transport interfaces where ambient pH is low because of localised activity of Na+/H+ exchangers.

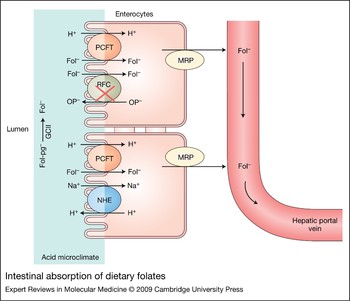

RFC and PCFT are expressed at the apical brush-border membrane of the proximal jejunum (Refs Reference Nakai58, Reference Qiu66, Reference Wang80, Reference Subramanian, Marchant and Said81); however, the acidic pH clearly favours PCFT over RFC (Fig. 6). Indeed, there is a large literature that demonstrates a low pH optimum at this site for folate transport and a K m for folic acid at or below 1 µM – properties clearly different from those reported for RFC. These encompass a broad spectrum of systems: intact intestine in man and rodents; isolated intestinal loops, rings and everted sacs in vitro; and isolated intestinal cells, cell lines or membrane vesicles of intestinal origin (Refs Reference Mason, Rosenberg and Johnson82, Reference Selhub and Rosenberg83, Reference Mason84).

Figure 6. Intestinal absorption of dietary folates. Dietary 5-methylTHF polyglutamates (Fol-pg−) are hydrolysed to monoglutamate (Fol−) by glutamate carboxypeptidase II (GCII) and then transported into cells via the proton-coupled folate transporter (PCFT). Both hydrolysis and PCFT-mediated transport have a low pH optimum and are favoured by the low pH within the microenvironment at the jejunal villi (indicated in blue) that is generated by Na+/H+ exchangers (NHE). RFC is expressed at the apical brush-border membrane but, as indicated by the red cross, is not functional at the pH in this region at usual folate dietary levels. Cellular folates exit the basolateral membrane by a mechanism that probably involves a member of the multidrug-resistance-associated protein (MRP) family of ATP-binding-cassette (ABC) exporters.

However, despite this, because RFC was identified at the intestinal apical brush-border membrane and there was no other known transporter at this location, absorption was attributed to RFC. Indeed, the functional discrepancies between intestinal transport and RFC-mediated transport were attributed to post-translational modifications of RFC that altered its functional properties, although such modifications were never identified (Refs Reference Kumar85, Reference Chiao86). Further evidence that the low-pH folate transport activity is due to a carrier genetically distinct from RFC came from studies in which RFC was deleted from the genome, mutated with loss-of-function, or was silenced. In these studies with a variety of cell lines, including those of intestinal origin, transport at pH 7.4 was lost or markedly diminished but the low-pH transport activity was preserved (Refs Reference Zhao62, Reference Chattopadhyay87, Reference Zhao, Hanscom and Goldman88, Reference Wang89). However, it remains unexplained how in one report siRNA to RFC suppressed folate transport activity in rat-derived intestinal epithelia cells at low, but not physiological pH (Ref. Reference Balamurugan and Said90).

Ultimately, the critical role that PCFT plays in intestinal folate absorption was unequivocally established with the demonstration that subjects with HFM invariably have loss-of-function mutations in the SLC46A1 gene (see below).

The folate receptors

Folate receptors FRα, FRβ and FRγ are very high affinity folate-binding proteins, encoded by three distinct genes located on chromosome 11. Folate receptors are homologous proteins (68–79% identical amino acid sequences), characterised by disparate patterns of tissue expression (see below). FRα and FRβ are both GPI-anchored proteins that mediate folate transport (Refs Reference Kamen and Smith5, Reference Salazar and Ratnam6, Reference Lu and Low91).

Folate receptors have high affinities for folic acid (K d 1–10 nM) (Ref. Reference Jansen and Jackman92). FRα and FRβ from both human and murine sources exhibit different specificities for (6S)- and (6R)-diastereomers of reduced folates, such as 5-methylTHF and 5-formylTHF (Refs Reference Brigle93, Reference Wang94). The markedly lower binding affinities of (6S)-5-methylTHF for FRβ compared with FRα was attributed to Leu49, Phe104 and Gly164 in FRβ, because replacement of these residues with the corresponding residues from FRα (Ala, Val and Glu, respectively) reconstituted the FRα phenotype (Ref. Reference Maziarz95).

Mechanistically, folate internalisation by membrane-associated folate receptors involves receptor-mediated endocytosis (Refs Reference Kamen and Smith5, Reference Salazar and Ratnam6, Reference Lu and Low91, Reference Kamen96, Reference Rothberg97). The process is initiated when a folate molecule binds to a folate receptor on the cell surface. This is followed by invagination of the plasma membrane at that site and the formation of a vesicle (endosome) that migrates along microtubules in the cytoplasm to the perinuclear endosomal compartment where it is acidified to a pH of ∼6.0–6.5. This results in dissociation of the folate from the folate receptor complex (Ref. Reference Yang79). Folate ligand is then exported into the cytoplasm by a process that requires a transendosomal pH gradient (Refs Reference Kamen96, Reference Rothberg97, Reference Kamen, Smith and Anderson98, Reference Prasad99). Recently, PCFT has been proposed as a mechanism of folate export from endosomes (Refs Reference Qiu7, Reference Umapathy59, Reference Andrews100) (Fig. 3, see below).

The physiological roles of folate receptors are unclear in all but a few cases. Although FRα and FRβ can transport folate into cells, this is inefficient compared with transporters such as RFC (Refs Reference Sierra101, Reference Spinella102). FRα is expressed in epithelial cells of the kidney, choroid plexus, retina, uterus and placenta (Refs Reference Salazar and Ratnam6, Reference Parker103). In proximal renal tubule cells, FRα is expressed at the apical (luminal) surface; however, in retinal pigment epithelium, it is expressed on the basolateral membrane (Refs Reference Smith104, Reference Chancy105). FRα is also expressed in tumours, particularly nonmucinous adenocarcinomas of the ovary, uterus and cervix (Ref. Reference Parker103). For ovarian carcinomas, FRα expression correlates with histological grade and stage (Ref. Reference Toffoli106). FRα is negatively regulated by the oestrogen receptor (Ref. Reference Kelley, Rowan and Ratnam107), whereas dexamethasone, a glucocorticoid receptor agonist, is a positive regulator of FRα (Ref. Reference Tran108).

FRβ is expressed during normal myelopoiesis and is present in placenta, spleen, thymus and in CD34+ monocytes (Refs Reference Ratnam109, Reference Wang110, Reference Reddy111, Reference Ross112). A nonfunctional form of FRβ was reported in CD34+ human haematopoietic cells (Ref. Reference Reddy111). FRβ is expressed in chronic myelogenous leukaemia and acute myelogenous leukaemia cells (Refs Reference Wang110, Reference Ross112, Reference Elnakat113). In the latter, FRβ expression is induced by treatment with retinoid-receptor agonists including all-trans retinoic acid (Ref. Reference Wang110). This is independent of cell differentiation or proliferation status and was not observed in nonmyeloid cells.

Folate transport mediated by ATP-binding-cassette transport proteins and other solute carriers

Beyond the transporters that are highly specific for folates, there are other potential folate transport routes. Relevant ATP-binding-cassette exporters include the multidrug-resistance-associated proteins, MRP1-MRP5 (ABCC1-ABCC5) and the breast cancer resistance protein, BCRP (ABCG2) (Refs Reference Kruh and Belinsky34, Reference Assaraf114, Reference Wielinga115). These are low-affinity, high-capacity transporters (K m values ∼0.2–2 mM for folates and antifolates). Members of this family are widely expressed in mammalian cells and suppress the level of free folates or antifolates that accumulate in most cells grown in vitro (Ref. Reference Kruh and Belinsky34). Some of the shorter-chain-length polyglutamate folates may be weak substrates for MRPs. However, in general, folate polyglutamates are retained within cells (Refs Reference Zhao and Goldman12, Reference Kruh and Belinsky34, Reference Fry, Yalowich and Goldman116).

From a physiological perspective, MRP2 plays a critical role in the export of folates across the bile canalicular membrane, as demonstrated by impaired biliary secretion of methotrexate in MRP2−/− mice (Ref. Reference Masuda117). The role that MRP family members play in the vectorial transport of folates in other tissues is less clear. Of particular interest is their potential role in the export of folates from jejunal enterocytes. MRP2 is expressed at the apical membrane, which would oppose absorption mediated by PCFT (Ref. Reference Mottino118). Since MRP3 is expressed at the basolateral membrane of rat jejunum (Ref. Reference Rost119), it could contribute to folate transport across the jejunal enterocyte by mediating export across the basolateral membrane. MRP1–MRP4 and BCRP are expressed in human jejunum, although relative levels have not been firmly established (Refs Reference Taipalensuu120, Reference Seithel121). Although MRP1 and MRP4 were localised to the basolateral membrane of some tissues, their localisation in human jejunum is not known (Ref. Reference Kruh and Belinsky34).

The SLC21 family of facilitative carriers transport organic anions, whereas the SLC22 family transport both organic anions and cations (Refs Reference Koepsell and Endou122, Reference Sekine, Miyazaki and Endou123, Reference Hagenbuch and Meier124). Both are expressed in tissues that mediate vectorial transport – the intestine, kidney and liver. Some of these carriers transport folates and antifolates. Of the SLC21 members, OAT-K1 and OAT-K2 are kidney specific and are expressed at the apical brush-border membrane. These transporters have K m values for methotrexate and 5-methylTHF of ∼2 µM and could play a role in reabsorption of folates at the proximal tubule (Ref. Reference Masuda125). OAT1, OAT2 and OAT3 belong to the SLC22 family and are expressed at the basolateral membrane of renal tubules (Ref. Reference Rizwan and Burckhardt126). These transporters generally have low affinities for methotrexate (10–700 µM), depending on the expression system (Refs Reference Uwai127, Reference Takeda128, Reference Nozaki129, Reference Cha130, Reference VanWert and Sweet131). Since RFC is also present at the basolateral membrane, it is unlikely that the SLC22 transporters have a major role in renal reabsorption of folates.

Genetic deletion of the reduced folate carrier and folate receptors

Genetic deletion of Slc19a1 and folate receptors has been achieved in the mouse. RFC heterozygous (+/–) mice have no phenotype. Loss of both alleles (−/−) is embryonic lethal; however, mice can be brought to term when pregnant females receive subcutaneously injected folic acid. However, pups die within ∼12 days of birth due to failure of erythropoiesis in bone marrow, liver and spleen (Ref. Reference Zhao132). More recent studies on Slc19a1 −/− mice from pregnant females supplemented with low levels of folate reveal a variety of congenital malformations (Ref. Reference Gelineau-van Waes133). FRβ-null mice are normal, as are mice heterozygous for FRα. Loss of both alleles encoding FRα protein is embryonic lethal; the embryos are arrested at the time of neural tube closure (Ref. Reference Piedrahita134). If, however, pregnant females receive parenteral 5-formylTHF throughout gestation, the pups are normal and can be maintained without any apparent abnormalities through to adulthood on a standard chow (R. Finnell, The Texas Institute for Genomic Medicine, Houston, TX, pers. commun.).

Hereditary folate malabsorption

The human PCFT-null genotype/phenotype is known within the context of the rare autosomal recessive disorder HFM (Refs Reference Qiu7, Reference Zhao9, Reference Min10, Reference Geller135). The major defects in HFM are: (1) impaired intestinal folate absorption, resulting in severe systemic folate deficiency; and (2) impaired transport of folates into the central nervous system, associated with very low to undetectable levels of folate in the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF).

PCFT+/− individuals are completely normal. Infants with HFM are normal at birth. Neural tube defects are not seen, indicating that there is adequate placental delivery of folates from mother to fetus. Signs of HFM begin several months after birth, presumably when folate stores provided by the mother during gestation are depleted. The infants develop anaemia, sometimes pancytopaenia, reflecting folate deficiency in rapidly proliferating haematopoietic cells. Gastrointestinal involvement manifests as severe diarrhoea. Immune deficiency due to hypoimmunoglobulinemia is frequent, resulting in infections usually associated with immunocompromised states (Pneumocystis carinii and cytomegalovirus pneumonia). Patients frequently have neurological signs including seizures, neurodevelopmental defects and/or mental retardation. Systemic signs of the disease can be obviated or reversed by low-dose parenteral folate or higher-dose oral folate, which normalises blood folate levels. However, very high blood folate levels are required to achieve CSF folate levels in the normal range (Ref. Reference Geller135).

Eight families with HFM have been reported to date with loss-of-function mutations in SLC46A1, the gene encoding PCFT. The mutations are indicated in Figure 5 (Refs Reference Qiu7, Reference Zhao9, Reference Min10, Reference Lasry136). No mutations were detected in the genes encoding RFC or FRα in patients with HFM. These observations unequivocally establish PCFT as the mechanism by which folates are absorbed across the apical brush-border membrane of the proximal jejunum under normal conditions. This is consistent with the low pH (5.8–6.0) at the jejunal brush-border membrane and observations that: (1) when jejunal pH is decreased, as occurs with pancreatic insufficiency, folate absorption is increased (Ref. Reference Russell137); and (2) when the pH is increased, as occurs with ingestion of antacids or after gastrectomy, intestinal folate absorption is decreased (Ref. Reference Russell138).

The clinical observation that high doses of oral folates can restore systemic folate levels in individuals with HFM raises the question of how intestinal folate is absorbed under these conditions (Ref. Reference Geller135). Defects due to SLC46A1 mutations that decrease the affinity for folates could be overcome by high doses of oral folates. However, in several cases, mutations produce a stop codon, a frameshift in exon 1, or a splicing defect, resulting in the absence of PCFT protein. In other cases, point mutations resulted in defects in trafficking, stability and/or a complete loss of intrinsic function (Refs Reference Qiu7, Reference Zhao9, Reference Min10, Reference Lasry136). Since passive diffusion of folates is assumed to be negligible even in the presence of pharmacological doses of folates, it is likely that intestinal absorption is mediated by RFC, albeit inefficiently, under these conditions.

The folate one-carbon journey from food to macromolecules

This section traces the pathway of folates ingested and the various folate transporters that mediate folate transport across epithelia and into systemic tissues.

Hydrolysis of folate polyglutamates

The major natural folate forms in the diet are polyglutamate congeners of 5-methylTHF that are not substrates for the absorptive process (Refs Reference Rosenberg139, Reference Butterworth, Baugh and Krumdieck140). This is consistent with the recent demonstration that affinities of PCFT for the di- to penta-glutamates of methotrexate are very low (Ref. Reference Qiu66). Rather, folate polyglutamate derivatives must be hydrolysed to their monoglutamate forms by glutamate carboxypeptidase II in human intestine and γ-glutamyl hydrolase in rat intestine (Refs Reference Halsted141, Reference Shafizadeh and Halsted142). The γ-glutamate hydrolytic reaction has a low pH optimum similar to the absorptive process, consistent with the low pH at the surface of mucosal cells in the proximal jejunum (Fig. 6).

Intestinal absorption

Once folate monoglutamate is generated, it is transported across the apical brush-border membrane of the proximal jejunum mediated by PCFT. Because PCFT transport is concentrative, driven by the transmembrane proton gradient generated by Na+/H+ exchangers, the high folate levels in enterocytes should facilitate folate efflux across the basolateral membrane into the periserosal space, and from there, folates enter the vascular system. The mechanism of export from enterocytes is not clear; neither RFC nor PCFT is expressed at the basolateral membrane. However, MRPs are expressed at this site, particularly MRP3 (Ref. Reference Kruh and Belinsky34), and might represent the route of export of folates (Fig. 6).

Transport to, and disposition in, the liver

After intestinal absorption, folates enter the hepatic portal system and are delivered to the hepatic sinusoids in apposition to the hepatocyte basolateral (sinusoidal) membrane. PCFT is highly expressed in the liver, and our preliminary results suggest that it localises to the sinusoidal membrane. This is consistent with a dominant low-pH folate transport activity in hepatocytes and in sinusoidal membrane vesicles derived from hepatocytes (Refs Reference Horne and Reed143, Reference Horne144). In the latter, concentrative folate transport is produced with a transvesicular pH gradient. There is minimal transport activity at pH 7.4, consistent with a low level of RFC activity (Refs Reference Horne, Reed and Said145, Reference Horne146), although RFC is detected at the hepatocyte membrane (Ref. Reference Wang80). It is unclear what the pH is within hepatic sinusoids where hepatic portal vein blood, derived from the intestine, pancreas and spleen, mixes with hepatic artery blood. It has been proposed that a Na+/H+ antiporter at the sinusoidal membrane may generate a local extracellular region of high acidity (Ref. Reference Arias and Forgac147), as is the case in the proximal jejunum.

Folates that enter the liver have three potential destinations. (1) Folates can be converted to polyglutamate storage forms or (2) they can be secreted into the bile at the hepatic canalicular membrane, mediated by MRP2 (Ref. Reference Masuda117), whereby they return to the duodenum and jejunum and are subsequently reabsorbed, thus completing the cycle of enterohepatic circulation. (3) Folate monoglutamates, formed by hydrolysis of polyglutamate forms stored in hepatocytes, or delivered directly from the hepatic portal vein, can enter the hepatic vein, ultimately reaching the systemic circulation whereby they accumulate in, and meet the one-carbon requirements of, peripheral tissues. Folates in blood also encounter epithelial barriers separating compartments containing highly folate-dependent tissues. Notable examples are neural tissues isolated by the vascular blood–brain barrier and the blood–choroid-plexus–CSF barrier.

Transport into systemic tissues

Membrane transport of folates into systemic tissues via the arterial system where the pH is 7.4 is mediated by the RFC. Although PCFT is often coexpressed with RFC, PCFT function would be minimal and would probably not contribute to the delivery of folates systemically, unless, as suggested above, there are tissues where Na+/H+ exchangers produce acid microenvironments at transport interfaces. PCFT may also have a role in FR-mediated transport (see below).

Filtration and reabsorption in the kidney

Blood folates not bound to serum proteins are filtered at the glomerulus; however, because of a highly efficient reabsorptive mechanism, little or none is lost in the urine at physiological levels of folate intake (Ref. Reference Goresky, Watanabe and Johns148). The initial step in reabsorption involves tight binding to FRα that is highly expressed at the luminal brush-border membrane of proximal tubules. The affinities of folates for this site are consistent with their affinities for FRα (Refs Reference Selhub, Nakamura and Carone149, Reference Selhub and Rosenberg150) and the urinary clearance of folates is inversely proportional to their affinities for FRα (Ref. Reference Selhub151). In the FRα−/− mouse (maintained on standard chow – see above) there is increased folic acid clearance and decreased 5-methylTHF uptake (Ref. Reference Birn152). Folates accumulate to high levels in the kidney, reflecting the large component bound to FRα. This is followed by internalisation of receptors, release of folate into the cytoplasm and export at the basolateral membrane by RFC, where the pH is optimal for carrier function (Refs Reference Wang80, Reference Goresky, Watanabe and Johns148, Reference Selhub, Nakamura and Carone149). Several SLC21 solute carriers are expressed at the apical brush-border membrane of proximal renal tubule cells and probably contribute to renal folate absorption, particularly at high folate loads, when FRα-mediated absorption is saturated (Ref. Reference Birn152). The role of PCFT in renal folate reabsorption is not clear. mRNA encoding PCFT protein is highly expressed in the kidney, but its exact location has not been defined (Refs Reference Qiu7, Reference Qiu66). In renal brush-border membrane vesicles, the folate flux and net transport is optimal at low pH when the pH of the trans compartment is 7.4, consistent with a PCFT-mediated process (Refs Reference Bhandari, Joshi and McMartin153, Reference Bhandari, Fortney and McMartin154). The pH in the proximal tubule starts at 7.4 and falls to ~6.8 as filtrate passes down the tubule, where bicarbonate is reabsorbed and chloride is secreted (Ref. Reference Jaramillo-Juarez, Aires and Malnic155). Under these conditions, should PCFT be present, only modest PCFT-mediated transport at the brush-border membrane would be expected.

Although a rigorous analysis of renal folate clearance in subjects with HFM has not been reported, some information can be gleaned from published studies. In one patient with HFM, the clearance of folate from blood, after an intravenous bolus, was no different from that of a normal subject over the first 2–3 hours (Ref. Reference Santiago-Borrero156). In another case, clearance in a patient with HFM over this interval was similar to that published earlier for normal subjects (Refs Reference Goresky, Watanabe and Johns148, Reference Lanzkowsky, Erlandson and Bezan157). These observations suggest that PCFT is not required for reabsorption of folates in the proximal tubule. However, since the initial phase of folate clearance from blood is influenced by uptake and retention in systemic tissues and tight binding of filtered folate to FRα, more than a few hours may be necessary to fully decipher the role of PCFT in the reabsorptive process. It is also possible that at least a component of the folate-receptor-mediated folate reabsorption in the proximal tubule represents a transcytosis in which vesicles formed at the brush-border membrane retain folate as they transit intact to the basolateral membrane where their contents are discharged to the peritubular space. However, uptake of tritiated folate alone, or folate coupled to colloidal gold particles, into renal tubular epithelial cells is consistent with translocation of vesicles across the brush-border membrane, followed at least in part by recycling back to that membrane via dense apical tubules (Refs Reference Birn, Nielsen and Christensen158, Reference Birn, Selhub and Christensen159).

Transport of folates across the blood–brain barrier and the choroid-plexus–CSF barrier

There are two potential routes of delivery of substrates to the brain, the blood–brain barrier at the cerebral vascular endothelium, and the blood–CSF barrier at the choroid plexus. RFC is localized to the vascular blood–brain barrier (Ref. Reference Wang80) and we have found that PCFT protein is expressed there as well. mRNA encoding FRα is neither expressed in brain parenchyma nor is FRα protein detected at the blood–brain barrier (Refs Reference Weitman, Frazier and Kamen160, Reference Kennedy161). The high rate of delivery of 5-methylTHF to brain parenchyma is consistent with folate extraction from blood mediated predominantly at the vascular blood–brain barrier (Ref. Reference Wu and Pardridge162). Transport of 5-methylTHF into human brain capillaries is saturable and can be inhibited by low levels of 5-methylTHF or folic acid (Ref. Reference Wu and Pardridge162). Although this has been interpreted as implicating a role for FRα, this is also consistent with a PCFT-mediated process for which folic acid and 5-methylTHF have comparable high affinities. However, there is no evidence that the pH at this transport interface is acidic.

The choroid plexus represents the pathway for the active transport of substrates and metabolites into and out of the CSF (Ref. Reference Segal163). The concentration of most small molecules in CSF is less than in blood (Ref. Reference Segal163). The opposite is the case for folates. The usual CSF:blood folate ratio is 2–3:1 (Ref. Reference Geller135), consistent with concentrative folate transport across the choroid plexus. It is clear that PCFT is required to achieve usual blood:CSF folate gradients, because this ratio is reversed in subjects with HFM (Ref. Reference Geller135). Evidence suggesting that FRα plays a role in this process comes from the observations that: (1) this protein is highly expressed in choroid plexus; and (2) blocking autoantibodies to folate receptors have been found in the blood of patients with cerebral folate deficiency. In this disorder, there are low levels of CSF folate even though folate intestinal absorption and folate blood levels are normal (Refs Reference Moretti164, Reference Moretti165, Reference Ramaekers166, Reference Schwartz167, Reference Ramaekers168). These subjects do not have mutations in genes encoding FRα, RFC or PCFT (Ref. Reference Moretti164).

Studies on transport of folates into the choroid plexus in vivo and in vitro further substantiate a role for this organ in the transport of folates (Refs Reference Kennedy161, Reference Wu and Pardridge162, Reference Spector and Lorenzo169, Reference Spector and Lorenzo170). We have found that PCFT protein is expressed at the basolateral membrane of ependymal cells at the capillary interface (Ref. Reference Zhao216); RFC is expressed at the apical membrane at the CSF interface (Ref. Reference Wang80). mRNA encoding the FRα protein is expressed in the choroid plexus and is visualised at the basolateral and, to a greater extent, apical basolateral membranes (Refs Reference Kennedy161, Reference Weitman171, Reference Weitman172, Reference Selhub and Franklin173, Reference Patrick174). Although both interfaces are likely at neutral pH, Na+/H+ antiporters expressed at the basolateral membrane (Ref. Reference Segal175) could produce an acid microclimate that facilitates PCFT function, as occurs in the proximal small intestine. One possible model that includes FRα and PCFT envisions FRα-mediated endocytosis across the basolateral membrane, generating a folate gradient across ependymal cells, followed by the downhill flow of folate across the apical membrane into the CSF mediated by RFC. Although RFC produces small folate gradients directed into cells, it mediates very rapid bidirectional fluxes of folates (Ref. Reference Zhao176). According to this model, PCFT facilitates FRα-mediated endocytosis by serving as a route for folate export from acidified endosomes into the cytoplasm (Fig. 3). There is evidence that PCFT augments FRα-mediated endocytosis in HeLa cells (Ref. Reference Zhao216). Similarly to transport across the vascular blood–brain barrier, 5-methylTHF appears to be the preferred substrate for transport across the choroid plexus (Refs Reference Wu and Pardridge162, Reference Spector and Lorenzo170, Reference Levitt177).

Transport of folates across the placenta

FRβ, RFC and PCFT are all expressed in the placenta (Refs Reference Qiu7, Reference Whetstine, Flatley and Matherly46, Reference Ratnam109, Reference Weitman172, Reference Maddox178), although the location and the spatial relationship among all these transporters has not been established. However, the observation that low levels of folic acid, but not methotrexate, inhibit maternal to fetal [3H]folic acid transport across guinea pig placenta suggests that FRα plays an important role in the initial phase of folate transport from maternal blood at the apical membrane of the syncytiotrophoblast (Refs Reference Sweiry and Yudilevich179, Reference Sweiry and Yudilevich180). Further evidence of a role for FRα in placental transport involves the inhibitory effects of bafilomycin A, which blocks the V-type proton pump, or FCCP, which abolishes the transmembrane proton gradient, on folic acid transport into tumour cells of trophoblastic origin. This is presumably due to their inhibitory effects on folate export from endosomes in the endocytic pathway (Ref. Reference Prasad99). Transport of folic acid in the BeWo trophoblastic cell line is maximal at pH 5.0, reflecting PCFT-mediated transport, and decreases as pH is increased, although a second peak of activity at pH 7.4 is also detected, probably reflecting RFC-mediated transport (Ref. Reference Keating181). Vectorial transport of folic acid across BeWo cells, from the apical compartment (maternal side) at pH 5.5, separated by a semipermeable membrane from the basal compartment (fetal side) at pH 7.4, was far greater than transport from the basal to apical compartments when the pH gradient was reversed (Ref. Reference Takahashi182). This suggests a higher level of PCFT activity at the apical interface than that at the basal interface.

Because the placenta is fetal in origin, and because PCFT–/– subjects with HFM do not have developmental defects associated with folate deficiency, PCFT does not appear to be necessary for placental transport of folate from mother to embryo or fetus, despite its high level of placental expression and its potential role in FRα-mediated endocytosis. The histories of families with HFM reveal that PCFT+/– females can support a normal pregnancy. Unanswered as yet, is whether the loss of two SLC46A1 alleles will affect delivery of folates to the fetus. The oldest reported female with HFM is now aged 28 and has had normal menarche but has not, as yet, become pregnant (Refs Reference Min10, Reference Poncz183, Reference Poncz and Cohen184).

Clinical implications/applications

Folate transport is a critical determinant of folate sufficiency and the integrity of one-carbon metabolism in man. Hence, expression of folate transporters, as determined by genetic, epigenetic and other regulatory factors, is of considerable importance. The requirements for RFC and FRα in embryonic development, and PCFT in infancy, are clear. Folate deficiency during adult life may be associated with transport variations that contribute to other pathophysiologic states including cancer, cardiovascular disease and neurological disorders (Refs Reference Davey and Ebrahim186, Reference Mischoulon and Raab187, Reference Ulrich and Potter188, Reference Martínez, Marshall and Giovannucci189). Folate deficiency in pregnant women is a major factor in fetal abnormalities (Ref. Reference Eichholzer, Tonz and Zimmermann190). Mild transport variations could be compounded by alterations in activities of folate-dependent interconverting and biosynthetic enzymes for which there are known allelic variations (e.g. C677T in MTHFR), which have an impact on cellular distributions of individual THF cofactor forms (Ref. Reference Lucock191). The cumulative effects could be impaired nucleotide biosynthesis, impaired repair of DNA damage, DNA hypomethylation resulting in aberrant oncogene expression, or DNA hypermethylation resulting in silencing of protective genes such as tumour suppressors (Ref. Reference Kim185).

An understanding of the molecular basis for HFM now makes possible a definitive diagnosis of this disorder in families. This allows genetic counselling, along with prenatal and in vitro testing. Individualisation of treatment with specific folates might be possible, based upon the functional characteristics and specificity of individual mutant PCFTs in patients with HFM.

RFC-mediated transport is an important determinant of the antitumour activities of antifolate chemotherapeutic drugs such as methotrexate (Refs Reference Matherly, Hou and Deng4, Reference Zhao and Goldman12, Reference Chattopadhyay, Moran and Goldman13). It was recognised early on that intrinsic and acquired resistance to methotrexate is frequently due to impaired transport in cell lines (Refs Reference Kessel, Hall and Roberts192, Reference Hakala193, Reference Fischer194) and is a factor in resistance to methotrexate in acute lymphoblastic leukaemia and osteogenic sarcoma (Refs Reference Ge195, Reference Guo196, Reference Levy197). Enhanced accumulation of methotrexate and its polyglutamates accompany increased levels of hRFC transcripts and copies of chromosome 21 in hyperdiploid B-precursor acute lymphoblastic leukaemia (Ref. Reference Zhang198).

Recently, pemetrexed was approved for the treatment of cancer in the USA, more than 50 years after the introduction of methotrexate (Ref. Reference Chattopadhyay, Moran and Goldman13). Pemetrexed has an affinity for RFC comparable with that of methotrexate. However, pemetrexed differs from methotrexate in its affinity for PCFT, which is sufficiently high, even at physiological pH, that its activity is preserved in tumour cells that are methotrexate resistant because of loss of RFC function (Refs Reference Chattopadhyay, Moran and Goldman13, Reference Chattopadhyay87, Reference Zhao199).

Research in progress and outstanding research questions

The transcriptional and post-transcriptional controls that contribute to tissue-specific expression of RFC have been largely defined (Ref. Reference Matherly, Hou and Deng4). Although there have been extensive studies of high-frequency sequence polymorphisms in RFC coding and noncoding regions in relation to a variety of pathological states (Refs Reference Matherly, Hou and Deng4, Reference Matherly56), these associations remain controversial. The recent production of a ‘humanised’ RFC mouse in which the mouse Slc19a1 is functionally replaced by the human SLC19A1 gene locus (Ref. Reference Patterson200) holds promise for extending in vitro findings of human RFC regulation and function including polymorphic SLC19A1 gene variants to a clinically relevant in vivo model. This will allow correlations with dietary folate status and biological manifestations of folate deficiency.

Structure–function studies of human RFC have provided substantive insight into its membrane topology, N-glycosylation, important domains and amino acids and three-dimensional helix-packing associations (Ref. Reference Matherly, Hou and Deng4). Preliminary studies indicate that there are higher-order oligomers (e.g. dimers) of RFC (Ref. Reference Hou and Matherly217), as has been observed for other transporters (Ref. Reference Veenhoff, Heuberger and Poolman201). Clarification of RFC oligomeric character is especially important for understanding carrier structure and function, including the mechanism of concentrative folate transport. The existence of homo-oligomeric human RFC might also have an important role in antifolate resistance through potential dominant-negative interactions between mutant and wild-type human RFCs that result in alterations in function and/or trafficking defects.

Since PCFT was only recently discovered, there is only scant information on the structural properties of this transporter. A predicted secondary structure was described and localisation of the N- and C-termini and the first extracellular loop was verified (Refs Reference Qiu66, Reference Unal74). Studies are ongoing to identify key amino acid residues that determine substrate binding, proton coupling and carrier mobility. Future studies will emphasise helix packing and tertiary structure using approaches such as substituted cysteine accessibility mutagenesis methods (Refs Reference Cao and Matherly35, Reference Karlin and Akabas202). The finding of higher-order RFC oligomers raises the intriguing possibility that this might occur for PCFT as well. Studies of PCFT structure and function would be enhanced considerably by the availability of a three-dimensional structural model of this transporter. The extrapolation of a prokaryotic model, based upon the glycerol-3-phosphate transporter crystal structure, to PCFT is appealing (Ref. Reference Lasry136), and this approach has been applied to other eukaryotic solute carriers (Ref. Reference Lemieux203). However, the utility of this and/or other models for the characterization of PCFT will require rigorous experimental verification, as noted above for RFC.

Since folate deficiency is associated with increased risk of colorectal cancer, deciphering the roles of RFC and PCFT in the delivery of folates to the large intestine and their regulation at this site, within the context of dietary and environmental factors, will be of considerable importance. These studies need to take into consideration the recent paradigm that folate deficiency results in an increased frequency of oncogenesis but, once cancers are formed, excess folates may accelerate tumour growth. This has been demonstrated in animal models (Refs Reference Song204, Reference Song205) and there is concern that there may be a similar risk for humans on dietary folate supplements (Refs Reference Ulrich and Potter188, Reference Kim206). For RFC, causal associations with loss of carrier function and colorectal cancer were described in mouse models (Refs Reference Ma207, Reference Lawrance208).

The hypothesis that PCFT is required for folate receptor function, by serving as a route of export from acidified endosomes, broadens the potential biological importance of this carrier. Clarification of this issue could establish a critical role for PCFT in the transport of folates across the blood–choroid-plexus–CSF barrier and explain why transport into the CSF compartment is impaired in HFM. Additional information is also required to clarify the functional role of PCFT in other tissues in which it is highly expressed, particularly where there is no evidence for a substantial acidic milieu at the transport interface. This relates in particular, to the extent to which PCFT mediates folate transport from the hepatic portal vein across the sinusoidal membrane to hepatic cells, reabsorption in the proximal renal tubule, transport across the placenta to the fetus, and transport across the choroid plexus and into brain parenchyma at the blood–brain barrier. These questions will be best addressed by studies on a PCFT-null mouse.

The role that PCFT plays in antifolate delivery to tumour cells requires further exploration. PCFT has a high affinity for pemetrexed and, when transfected into tumour cells, selectivity augments the growth-inhibitory activity of the drug without a salutary effect on other antifolates, such as methotrexate, PT523 or raltitrexed, which have a much lower affinity for PCFT at physiological pH (Ref. Reference Zhao67). It will be important to determine whether PCFT contributes more to the activity of pemetrexed, or to the activities of other antifolates when transport occurs within solid tumours in vivo, where cells are hypoxic, the microenvironment is acidic and PCFT would be expected to operate more efficiently (Refs Reference Helmlinger209, Reference Tredan210, Reference Raghunand211). Likewise, because of the high K m values for antifolate transport at physiological pH, it will be important to determine the role PCFT might play in the delivery of antifolates at the high blood levels achieved in clinical regimens under conditions in which RFC is saturated.

Finally, there is an ongoing interest in the development of new-generation antifolates. Antifolate thymidylate synthase inhibitors were designed with very low affinity for RFC but very high affinity for FRα to minimise toxicity due to uptake via RFC, which is ubiquitously expressed, and to maximise uptake via folate receptors that are more selectively expressed in certain tumours (Refs Reference Theti212, Reference Henderson213, Reference Gibbs214). An analogous strategy was recently described for a series of highly potent FR-targeted antifolate GAR (β-ribosylglycinamideribonucleotide) transformylase inhibitors (Ref. Reference Deng215). It will be of particular interest to determine whether the activities of some of these novel FR-targeted agents will be related to their affinities for PCFT, which might enhance their uptake in the acidic milieu of solid tumors and/or their export from endosomes during the endocytic cycle.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank the reviewers of this manuscript for their very helpful suggestions. This work was supported by grants CA53535 (L.H.M.) and CA82621 (I.D.G.) from the National Institutes of Health.