The prevalence of diabetes mellitus is an alarming global health issue. It is one of the six leading causes of death in the United States, where it affects nearly 21 million people (Ref. Reference Resnick1). Diabetes-associated cardiovascular complications and diabetic neuropathy have an important pathophysiological role in the progression of heart failure in both type 1 and type 2 diabetes and account for 30% of diabetes-related complications (Ref. Reference Cohen-Solal, Beauvais and Logeart2). Cardiovascular complications associated with diabetes include coronary artery disease, peripheral vascular disease (PVD), cardiomyopathy and heart failure. Diabetes confers a twofold increase in the risk of death from heart failure (Ref. Reference Giles and Sander3), and according to the United Kingdom Prospective Diabetes Study (UKPDS) the incidence of heart failure correlates with the extent of hyperglycaemia: each 1% increase in haemoglobin A1C (HbA1c) level is associated with a 12% increase in heart failure risk (Ref. Reference Stratton4).

Diabetic neuropathy is a cluster of different neuropathies that vary in symptoms, pattern of neurological involvement and underlying mechanisms (Ref. Reference Tesfaye5). It is a common complication, affecting 60–70% of patients (Ref. Reference Tesfaye5). For almost a century, since the term ‘diabetic neuropathy’ was proposed, scientists have been investigating not only the causes of diabetic neuropathy, but also the consequences of this common complication. The first report on the presence of sugar in urine dates back to 1674; however, the neurological symptoms associated with diabetes were first reported almost 200 years later in 1864 by De Calvi, and the first clinical study implicating diabetes in the degeneration of peripheral nerves was conducted in 1929 (Ref. Reference Rudy6).

Neurohormonal activation has a strong pathophysiological role in diabetes, insulin resistance and cardiovascular disease. However, the role of neurohormones and their neuropeptide effectors in diabetes-associated heart failure is not fully understood. In diabetes, the levels of both autonomic and sensory neuropeptides are dysregulated in the myocardium (Ref. Reference Levy7). These cardioactive neuropeptides include neuropeptide Y (NPY) (Ref. Reference Bolinder8), substance P (SP; also known as tachykinin 1 or TAC1) (Ref. Reference Kunt9), calcitonin-gene-related peptide (CGRP; also known as CALCA/B) (Ref. Reference Ponery10) and the natriuretic peptides (NPs), atrial natriuretic peptide (ANP; also known as A-type natriuretic peptide), brain natriuretic peptide (BNP; also known as B-type natriuretic peptide) and C-type natriuretic peptide (CNP) (Ref. Reference McKenna11). In addition to these neuropeptides, their receptors are also affected in diabetes, and thereby the downstream neuropeptide signalling cascade is disrupted.

Our hypothesis therefore is that the diabetic milieu causes neuropathy, leading to severe dysregulation of neuropeptide expression or activation within the myocardium. This impairment in neuropeptide signalling contributes to the cardiac dysfunction and heart failure associated with diabetes. The major goal of this review is to provide up-to-date information on the role of neuropeptides in diabetic heart failure. In doing so, we begin with a broad overview of the mechanisms of diabetic heart failure and diabetic neuropathy and end with an in-depth analysis of the different neuropeptides that might be affected in diabetes and that have a role in the cardiovascular system.

Mechanisms of diabetic heart failure

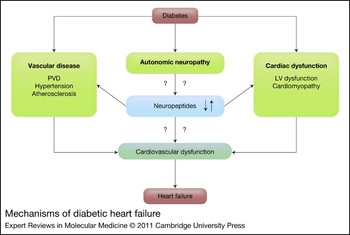

Diabetes and associated complications such as hypertension, dyslipidaemia, obesity, inflammation, poor glycaemic control, autonomic neuropathy, coronary artery disease or diabetic cardiomyopathy are all linked to heart failure (Ref. Reference Giles and Sander3). Autonomic neuropathy that is independent of vascular disease is also involved in major cardiovascular events such as myocardial infarction, ischaemia, fibrillation, or angina and heart failure (Ref. Reference Ziegler12). As illustrated in Figure 1, diabetes causes autonomic neuropathy, and vascular and cardiac dysfunction. Autonomic neuropathy, in turn, can cause neuropeptide dysregulation. This dysregulation further contributes to vascular diseases and cardiac dysfunction, ultimately leading to cardiovascular dysfunction and heart failure (Fig. 1). The dysregulation in neuropeptides might be a major nodal point connecting diabetes and autonomic neuropathy to heart failure.

Figure 1 Mechanisms of diabetic heart failure. Diabetes is known to lead to autonomic neuropathy, vascular disease and cardiac dysfunction. Autonomic neuropathy can lead to neuropeptide dysregulation. Diabetes-associated vascular diseases include peripheral vascular disease (PVD), hypertension and atherosclerosis. Diabetes-associated cardiac dysfunctions include left ventricular (LV) dysfunction and cardiomyopathy. Neuropeptide dysregulation might further contribute to cardiovascular dysfunction that can finally lead to heart failure.

Vascular diseases are major causes of physical disabilities and death in patients with diabetes (Ref. Reference Veves13), and account for approximately 80% of all deaths among diabetic patients (Ref. Reference Aronson14). Diabetes increases the risk for development of coronary atherosclerosis (Ref. Reference Monahan15), which in turn significantly enhances the risk of heart failure (Ref. Reference Bauters16). Additionally, coronary artery disease is the primary cause of heart failure in approximately two-thirds of patients with left ventricular (LV) systolic dysfunction (Ref. Reference Gheorghiade and Bonow17). The pathophysiology of vascular disease in diabetes includes abnormalities in the function of endothelial cells, vascular smooth muscle cells (Ref. Reference Orasanu18) and platelets, and a change in haemostatic factors (Ref. Reference Morel19). Hyperglycaemia, increased free fatty acids and insulin resistance all contribute to vascular dysfunction (Ref. Reference Rask-Madsen and King20).

Diabetic cardiomyopathy, defined as a myocardial dysfunction, is a distinct primary disease that is independent of coronary artery disease and predisposes to the progression of heart failure (Ref. Reference Bauters16). Risk factors for diabetic cardiomyopathy are age, hypertension, obesity, coronary artery disease and hyperlipidaemia, and it is characterised by LV hypertrophy, and diastolic and systolic dysfunction (Ref. Reference Hayat21). Metabolic abnormalities might also have an important role in the progression of myocardial dysfunction, which leads to hyperglycaemia, impaired myocardial glucose uptake, increased free fatty acids and insulin resistance. These factors result in biochemical events leading to cardiomyopathy and heart failure (Ref. Reference Falcao-Pires and Leite-Moreira22).

Diabetic neuropathy

Diabetic neuropathies are heterogeneous and involve dysfunction of large myelinated fibres and small thinly myelinated or nonmyelinated fibres. Small-fibre neuropathy results in a reduction of nerve growth factors and other neurotransmitters such as SP and CGRP (Ref. Reference Pittenger and Vinik23). The pathogenesis of diabetic neuropathy is probably a combination of metabolic and neurovascular factors that lead to a decreased supply of oxygen and nutrients to nerves in diabetic patients (Ref. Reference Obrosova24). These patients can develop neuropathy at any stage, but risk progresses with age, inadequate glycaemic control and duration of diabetes (Ref. Reference Valensi25). Diabetic neuropathy can be classified as peripheral, autonomic, proximal and focal, each of which affects different parts of the body in different ways. Peripheral neuropathy, also called distal symmetrical neuropathy or sensory motor neuropathy, is most common, and affects the nerves of the extremities (Ref. Reference Dinh26). Autonomic neuropathy most often involves the nerves that control the heart, regulate blood pressure and control blood glucose levels (Ref. Reference NINDS27). Focal neuropathy affects the nerves in the head, torso and legs. Proximal neuropathy is generally caused by inflammation, affects the lower limbs, and is characterised by a variable degree of pain and sensory loss associated with unilateral or bilateral proximal muscle weakness and atrophy (Refs Reference Krendel28, Reference Said29).

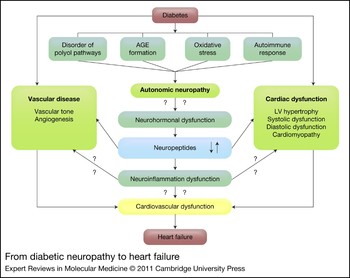

Several pathogenic processes might be involved in diabetic neuropathy, including glycosylation, metabolic insult to nerve fibres, autoimmune destruction, deficiency of the neurovascular, neurohormonal growth factors and oxidative stress (Fig. 2) (Ref. Reference Pittenger30). Hyperglycaemia leads to activation of the polyol pathway, leading to activation of protein kinase C (PKC), which induces vasoconstriction and neuronal damage and reduces neuronal blood flow (Ref. Reference Veves and King31). Hyperglycaemia-induced oxidative stress causes vascular endothelial damage and reduces nitric oxide (NO) bioavailability (Ref. Reference Cameron and Cotter32), whereas excess NO results in nitrosative stress and damage to the endothelium and neurons (Ref. Reference Hoeldtke33). Autoimmunity and inflammation are also involved in neuronal loss and dysfunction (Ref. Reference Pittenger30). Reduction in neurotrophic factors, deficiency of essential fatty acids and formation of advanced glycation end products (AGEs) result in reduced endoneurial blood flow and nerve hypoxia with altered nerve function (Ref. Reference Winkler and Kempler34).

Figure 2 From diabetic neuropathy to heart failure. Diabetes results in activation of the polyol pathways, formation of advanced glycation end products (AGEs), oxidative stress and immune dysfunction. These factors lead to autonomic neuropathy. Diabetes is known to cause vascular and cardiac dysfunction. Autonomic neuropathy can lead to neurohormonal dysregulation, which disrupts neuropeptide function. Neuropeptide dysregulation, either directly or perhaps by dysregulated neuroinflammation, contributes to vascular and cardiac dysfunction by modulating vascular tone, impairing angiogenesis, causing cardiomyopathy and left ventricular (LV) hypertrophy, and affecting systolic and diastolic functions. These cardiovascular dysfunctions can ultimately lead to heart failure.

Diabetic autonomic neuropathy

Diabetic autonomic neuropathy is a serious complication resulting from long-term diabetes that has a negative impact on survival and quality of life (Ref. Reference Vinik and Erbas35). Diabetic autonomic neuropathy involves the entire autonomic nervous system, including the gastrointestinal, genitourinary and cardiovascular systems (Ref. Reference Vinik36). The signs, symptoms and treatment of diabetic autonomic neuropathy vary, depending on the cause and the nerves that are affected. Clinical signs and symptoms include resting tachycardia, exercise intolerance, orthostatic hypotension, silent myocardial ischaemia, erectile dysfunction, impaired neurovascular function, ‘brittle diabetes’ and hypoglycaemic autonomic failure (Ref. Reference Vinik36).

Cardiovascular autonomic neuropathy

Cardiovascular autonomic neuropathy is the most investigated form of diabetic autonomic neuropathy (Ref. Reference Vinik36). In cardiovascular autonomic neuropathy, nerve fibres that innervate the heart and blood vessels are damaged, resulting in abnormalities in the heart and vasculature (Ref. Reference Schumer, Joyner and Pfeifer37). Diabetic patients with this form of neuropathy have a five times higher cardiac mortality than diabetic individuals with other forms of neuropathy (Ref. Reference Ziegler38). The incidence of cardiovascular autonomic neuropathy is 16.8% for type 1 diabetes and 22.1% for type 2 diabetes (Ref. Reference Vinik and Erbas39). The increased mortality might be a result of the direct effect of autonomic neuropathy itself and the indirect effect of accelerating microvascular complications (Ref. Reference Ziegler38). Cardiovascular autonomic neuropathy results in both parasympathetic and sympathetic dysfunction, resulting in increased resting heart rate. The combined parasympathetic and sympathetic dysfunctions might be followed by a fixed heart rate (Ref. Reference Maser and Lenhard40) as detected by loss of heart rate variability (Ref. Reference Weimer41). The Action to Control Cardiovascular Risk in Diabetes (ACCORD) trial showed that cardiac autonomic neuropathy is associated with high mortality (Ref. Reference Pop-Busui42).

Cardiovascular autonomic neuropathy and left ventricular dysfunction

Coronary artery disease and hypertension are associated with LV dysfunction (Ref. Reference Debono and Cachia43). Cardiovascular autonomic neuropathy, through alteration in myocardial blood flow and sympathetic denervation, and changes in myocardial neurotransmitters of the neuropeptidergic system (such as SP, CGRP, vasoactive intestinal peptide and NPY) can cause LV dysfunction (Ref. Reference Debono and Cachia43). Cardiovascular autonomic neuropathy correlates with LV diastolic dysfunction (Ref. Reference Uusitupa, Mustonen and Airaksinen44) in type 2 diabetes, and is associated with LV hypertrophy or higher LV mass index, and diastolic and systolic dysfunction in type 1 diabetes (Ref. Reference Taskiran45). Other studies in cultured rat myocytes (Ref. Reference Rapacciuolo46) and canines (Ref. Reference King47) have shown that hypertrophy or higher LV mass index might be due to sympathetic stimulation or prolonged infusion of norepinephrine.

Cardiovascular autonomic neuropathy and neuropeptides

There is increasing evidence that reduction or loss of neural activation is associated with cardiovascular autonomic neuropathy in diabetes (Ref. Reference Pop-Busui48). The level of pancreatic polypeptide and NPY is absent or low in type 1 diabetic patients with cardiovascular autonomic neuropathy than in individuals without it (Ref. Reference Bolinder8). It has been shown that the level of NPY in diabetic patients might be a useful marker of sympathetic nerve failure (Ref. Reference Sundkvist49). The expression of autonomic neuropeptides such as NPY and vasoactive intestinal peptide is significantly reduced in cardiovascular autonomic neuropathy patients with rheumatic diseases (Ref. Reference El-Sayed50). Moreover, acrylamide-induced autonomic neuropathy of rat mesenteric vessels shows the greatest reduction in intensity and number of CGRP and SP nerves (Ref. Reference Ralevic, Aberdeen and Burnstock51). Reduced expression of SP and CGRP is also observed in cardiovascular autonomic neuropathy patients (Ref. Reference Pittenger and Vinik23).

Diabetes, heart and neuropeptides

NPY, SP, CGRP, ANP, BNP and CNP are vasomodulators released from the central and peripheral nervous systems (PNS). These neuropeptides have an important role in cardiomyocyte hypertrophy (Refs Reference Meit Björndahl, Luxun and Yihai52, Reference Chen53), ischaemic revascularisation (Refs Reference Ekstrand54, Reference Zukowska-Grojec55), wound healing (Refs Reference Pradhan56, Reference Jain57), myocardial contractility (Refs Reference Kim, Cho and Kim58, Reference Woo and Ganguly59), PKC activation (Ref. Reference Sieburth, Madison and Kaplan60), modulation of the rennin–angiotensin–aldosterone system (RAAS) and AGEs (Ref. Reference Hackenthal61). These neuropeptides affect several important functions that maintain cardiovascular homeostasis; therefore, any changes in their signalling can lead to cardiovascular dysfunctions.

Neuropeptide Y

NPY is a 36-amino-acid peptide. It is one of the most abundantly and ubiquitously distributed neurotransmitters in the central nervous system (CNS) and the PNS (Ref. Reference Blomqvist and Herzog62). In the CNS, NPY is mainly released from the paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus (Ref. Reference Adrian63) and appears in the cerebrospinal fluid (Ref. Reference Kaye64). NPY is also produced by vascular smooth muscle cells, endothelial cells, vas deferens cells and pancreatic acinar cells (Refs Reference Adrian63, Reference Zukowska65). It signals through G-protein-coupled receptors with six subtypes: NPY1R, NPY2R, NPY3R, NPY4R, NPY5R and NPY6R (Ref. Reference Brothers and Wahlestedt66). NPY and its receptors NPY1R, NPY2R and NPY5R have an important role in the pathophysiology of a number of diseases, including diabetes, heart failure, hypertension, PAD and feeding disorders (Ref. Reference Pedrazzini, Pralong and Grouzmann67). Furthermore, these receptors are involved in angiogenesis (Ref. Reference Zukowska-Grojec55), calcium homeostasis (Ref. Reference Pedrazzini, Pralong and Grouzmann67), RAAS and PKC activation of diabetes and heart failure (Ref. Reference Kohno68). NPY stimulates the growth of vascular smooth muscle cells (Ref. Reference Pons69) and also has a critical role in atherosclerosis and stress-related alterations of immunity (Ref. Reference Zukowska65).

NPY and diabetes

NPY levels are decreased in patients with type 1 diabetes with cardiac autonomic neuropathy (Ref. Reference Bolinder8). NPY expression is also reduced in the heart, hippocampus and frontal cortex tissue of streptozotocin (STZ)-induced diabetic rats (Ref. Reference Kuncova70). Conversely, in the arcuate nucleus of rats, insulin and hypoglycaemia increase the transcription of the gene encoding NPY (Ref. Reference Watanabe71).

NPY, when acting through its receptor NPY1R, causes vasoconstriction. In alloxan-induced diabetic rabbits, the contractile effect of NPY is reduced in cerebral and coronary vessels (Ref. Reference Andersson72). Clinically, vascular smooth muscle contractile response to NPY is markedly attenuated in diabetic patients (Refs Reference Lind73, Reference Zhang, Han and Zhou74). Thus, in diabetes, it is not just the expression, but also the effect of exogenous NPY, that is diminished in the vasculature.

In contrast to the above studies, in a recent study, plasma NPY levels were increased in patients with type 2 diabetes (Ref. Reference Matyal75). As mentioned earlier, non-neuronal cells such as smooth muscle cells, endothelial cells, pancreatic acinar cells and vas deferens cells can produce NPY. In patients with chronic type 2 diabetes, a compensatory increase in these extraneuronal sources of NPY might explain the discrepancy.

NPY and the heart

NPY is located in the sympathetic nerve endings of the coronary vasculature and cardiac myocytes of humans and many other species. Functional NPY receptors in the heart are NPY1R, NPY2R and NPY5R (Ref. Reference Pedrazzini, Pralong and Grouzmann67). In rats, NPY is co-stored and co-released with norepinephrine and ATP in the postsympathetic nerve terminal and with epinephrine in the adrenal medulla (Ref. Reference Olcese76). However, at presynaptic nerve terminals, NPY inhibits the release of norepinephrine by a negative-feedback mechanism (Ref. Reference Olcese76). NPY, acting through NPY1R and NPY5R, has a pathogenic role by inducing cardiac hypertrophy and vasoconstriction of coronary vessels (Refs Reference Zukowska65, Reference Allen77). In rat models, NPY leads to vasoconstriction indirectly by potentiating the effect of norepinephrine-induced calcium signalling (Ref. Reference Wier78) and by a direct effect of NPY on increasing intracellular calcium ([Ca2+]i) (Ref. Reference Prieto79). NPY induces angiogenesis through NPY2R and NPY5R, and thus has an imperative role in ischaemic revascularisation and wound healing (Refs Reference Meit Björndahl, Luxun and Yihai52, Reference Pradhan56). Therefore, in diabetic patients with reduced NPY expression or activity, there could be a diminished angiogenic response after ischaemia or after wounding, seriously affecting recovery.

Although plasma NPY levels have also been shown to be increased in diabetic patients, there is a decrease in neuronal NPY expression in the right atrium of diabetic patients undergoing coronary artery bypass surgery (Ref. Reference Matyal75). The same study showed that NPY2R and NPY5R expression is increased within the diabetic right atrium. This increase in receptor expression could be counter-regulatory to the reduced NPY expression in the myocardium. In a rat model of long-term type 1 diabetes, similar results are observed, with a reduced expression of NPY and an increased expression of NPY1R in the myocardium of diabetic rats (Ref. Reference Chottova Dvorakova80). Although NPY is a vasoconstrictor in most vascular beds, in the myocardium it decreases contractility. In isolated perfused rat myocardium, NPY decreases the positive chronotropic effect of phenylephrine and isoprotrerenol by decreasing the activity of sarcolemmal Na+/K+ ATPase (Ref. Reference Woo81). In a similar rat model, NPY decreases the positive inotropic effects induced by agonists without having a direct effect (Ref. Reference Woo and Ganguly59).

NPY also stimulates protein synthesis in adult rat cardiomyocytes by activation of pertussis toxin-sensitive G-proteins and phosphoinositol 3-kinase, and induces the fetal-type creatinine kinase-BB by activation of PKC and mitogen-activated protein kinase (Ref. Reference Goldberg82). Exposure of mouse neonatal cardiomyocytes to NPY induces rapid phosphorylation of the extracellular responsive kinase the Jun N-terminal kinase and the p38 kinase, as well as activation of PKC (Ref. Reference Pellieux83).

In a swine model of chronic myocardial ischaemia, exogenous addition of NPY increases mean arterial pressure and improves LV function without changing blood flow (Ref. Reference Robich84). However, there is an increase in capillary and arteriole formation, along with upregulation of NPY1R, NPY2R, NPY5R, vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS), phospho-eNOS (p-eNOS) on Ser1177 and platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF), and downregulation of antiangiogenic factors endostatin and angiostatin in the NPY-treated group (Ref. Reference Robich84). This large animal study emphasises the role of NPY in ischaemic angiogenesis wherein all the important angiogenic (pro- and anti-) factors are affected by NPY. However, the study does not address the connection or lack thereof between increased ischaemic myocardial angiogenesis, with unchanged blood flow achieved by NPY treatment. In addition to its effects on angiogenesis and myocardial function, NPY also activates diuretic and natriuretic properties in vivo (Refs Reference Meit Björndahl, Luxun and Yihai52, Reference Waeber85, Reference Winaver and Abassi86) and promotes the clearance of water and electrolytes by increasing the release of ANP from isolated rat left atrium (Ref. Reference Piao87). NPY has a prominent role in the kidneys, as demonstrated in an isolated rat kidney study, where it induces renal vasoconstriction and inhibits renin release by inhibiting adenylate cyclase activity in vascular smooth muscle and renin-producing cells (Ref. Reference Hackenthal61). In a rat myocardial infarction model of moderate compensated congestive heart failure, continuous infusion with NPY led to a decrease in renin levels (Ref. Reference Zelis88).

Thus, NPY and its receptors have a diverse role in the cardiovascular system by affecting almost all components of this system; therefore, any perturbations in its expression or signalling can have serious effects. There does not seem to be a single common pathway that it evokes. However, its role as a proangiogenic molecule seems to be the most consistent of its cardiovascular effects, with serious implications in diabetes-associated heart failure and the reparative response to a myocardial infarction. Its role in cardiac hypertrophy and vasoconstriction, although not clearly understood, can serve as a contributory factor towards development of diabetic heart failure.

Substance P

SP is an undecapeptide that functions as a neurotransmitter and a neuromodulator that alters the excitability of the dorsal horn ganglion (pain-responsive neurons) (Ref. Reference Ohtori89). It is expressed in the CNS and the PNS (Ref. Reference Hokfelt90) and is released from sensory nerve fibres. Enteroendocrine cells are one of the major sources of endocrine and circulating SP (Ref. Reference Roth and Gordon91). SP is involved in several physiological activities, including maintenance of cardiovascular tone, smooth muscle activity, vomiting reflex, defensive behaviour and stimulation of salivary secretion (Ref. Reference Nieber and Oehme92). The SP receptor, also known as neurokinin 1 receptor (NK1R), belongs to the tachykinin receptor subfamily of GPCRs. NK1R is present in a variety of cell types, including immune cells, epithelial cells, endothelial cells, glial cells and neurons. The interaction of SP with NK1R activates G q, which in turn activates phospholipase C with the net rise in [Ca2+]i that induces tissue response (Ref. Reference Khawaja and Rogers93). SP is metabolised by the enzyme enkephalinase, a zinc metalloprotease that is also known as neutral endopeptidase (NEP) and is present in the cell membrane of cells that express NK1R (Ref. Reference Trippodo94).

SP and diabetes

SP expression is decreased in the CNS and PNS of patients with type 1 and type 2 diabetes (Ref. Reference Kunt9). In the nonobese type 1 diabetic mouse model, administration of SP impedes chronic, progressive β-cell stress, reduces islet cell inflammation, reduces insulin resistance and restores normoglycaemia (Ref. Reference Tsui95). Similarly, skin biopsies from both type 1 and type 2 diabetes patients show a reduced density of SP nerve fibres (Ref. Reference Lindberger96). In type 2 diabetic patients, decreased expression of neuronal NOS and SP is accompanied by a deficiency of gastric interstitial cells of Cajal associated with diabetic gastroparesis (Ref. Reference Iwasaki97). NK1R is the predominant receptor through which SP is known to exert its effect, and signalling through this receptor is affected in most diseases whenever SP is implicated. However, there are a few studies suggesting a change in NK1R expression itself. In one study, a decrease in NK1R expression was observed in the dorsal root ganglia of diabetic rats (Ref. Reference Boer98). These studies suggest that, unlike NPY whose expression could be up- or downregulated in diabetes, SP expression is always downregulated. This downregulation is the effect of diabetes and hyperglycaemia that might lead to sensory denervation and neuropathy.

SP and the heart

Although not an autonomic neuropeptide, SP is significantly associated with cardiovascular regulation (Ref. Reference Paulus99). Most of its effects counteract the effect of autonomic effectors such as norepinephrine and epinephrine. In addition to enteroendocrine cells, other major sources of circulating SP are perivascular nerves. SP release through perivascular nerves contributes to the regulation of vascular tone and acts as a vasodilator, in addition to reducing the effect of vasoconstrictive factors in patients with congestive heart failure (Ref. Reference Tingberg100). Our lab has recently shown that SP increases human dermal microvascular endothelial cell proliferation and tube formation, but the exact mechanism is not clear (Ref. Reference Jain57). Also, SP expression is reduced in cutaneous wounds of diabetic rabbits (Ref. Reference Pradhan101). Several reports have shown that SP enhances the release of NO, which preserves the expression of sarcoplasmic reticular Ca2+ ATPase by opposing norepinephrine. This effect of SP protects myocardial calcium homeostasis and heart function (Refs Reference Paulus99, Reference Calderone102). A recent canine study shows that atrial fibrillation leads to ventricular remodelling with a decrease in SP-positive nerves (Ref. Reference Yu103). Also, blockade of NK1R deteriorates postischaemic recovery of heart in a mouse model (Ref. Reference Wang and Wang104). Furthermore, increasing expression of SP protects the heart from injury by enhancing NK1R expression in guinea pigs and rats (Ref. Reference Wharton105). Another recent rat study shows that loss of cardioprotection by ischaemic postconditioning during diabetes is partly associated with failure to increase the release of CGRP and SP in diabetic hearts. This study also shows that SP and CGRP induce ischaemic postconditioning in both nondiabetic and diabetic hearts, preventing ischaemia–reperfusion injury by improving cardiac function as a consequence of lower levels of creatinine kinase and cardiac troponin I (Ref. Reference Ren106). Treatment with SP reverses LV hypertrophy in patients with essential hypertension (Ref. Reference Yan, Gao and Deng107). Plasma levels of SP are increased in heart failure patients receiving ACE inhibitors compared with those given a placebo, suggesting that ACE breaks down SP (Ref. Reference Valdemarsson108). Thus, ACE inhibitors, in addition to their effect on blocking the expression of angiotensin II, can increase the expression of SP and therefore add to their therapeutic effects. In contrast to the above studies, which show cardioprotective effects of SP, there are fewer studies implicating SP in the pathophysiology of cardiomyopathy and heart failure. Whether the increase in SP is a cause or effect of the underlying pathology is not clear from these studies. In a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled study using the NK1R antagonist aprepitant, SP causes a tonic enhancement of sympathetic outflow to some cardiovascular structures by modulating NK1R (Ref. Reference Dzurik109).

In another study of acute myocardial infarction, within 15 min of coronary artery occlusion, there was an increase in SP in the rat myocardium (Ref. Reference Wang110). Moreover, this study also showed that SP regulates cardiac function through NK1R by modulating adrenergic actions through the protein kinase A pathway (Ref. Reference Wang110). In a rodent model, SP induced parasitic dilated cardiomyopathy (Ref. Reference D'Souza111) and, similarly, SP was increased in patients with moderate and severe congestive heart failure (Ref. Reference Edvinsson112).

Because of its vasodilatory and angiogenic effects, SP seems to have a cardioprotective role that can be compromised in diabetes where SP expression is diminished. In cardiovascular diseases where SP is implicated, its increased expression might be a counter-regulatory effect to negate the effect of sympathetic effectors. In diabetes, where such compensation by SP cannot be achieved as a result of the lack of SP-positive nerves, therapies should be designed for supplementation with SP. Therefore, to determine the ‘cause’ or ‘consequence’ role of SP, additional studies are warranted to perform a more in-depth analysis of this molecule in animal models of diabetes-associated cardiac dysfunction.

Calcitonin-gene-related peptide

CGRP is a 37-amino-acid peptide synthesised in the CNS and the PNS, which is generated from the alternate splicing of mRNA encoding calcitonin in a tissue-specific manner (Ref. Reference Ponery10). CGRP normally colocalises with SP in the sensory nervous system and is a potent vasodilator; it also has various biological effects and both circulatory and neurotransmitter modes of action (Ref. Reference Bergdahl113). The effects of CGRP are mediated by the activation of at least two CGRP receptor subtypes: CGRP1R and CGRP2R (Ref. Reference Quirion114). In addition, calcitonin-receptor-like receptor has also been described as a CGRP receptor (Ref. Reference Juaneda, Dumont and Quirion115) that always requires receptor-activity-modifying protein 1 (RAMP1) (Ref. Reference McLatchie116).

CGRP and diabetes

CGRP shows about 50% homology with amylin, colocalises with insulin (Ref. Reference Adeghate117) and somatostatin (Ref. Reference Saffir118) in the islets of Langerhans, and might be involved in the synthesis or release of insulin from secretory granules (Ref. Reference Adeghate117). It is a circulating hormone that modulates peripheral insulin sensitivity (Ref. Reference Parlapiano119). Studies have also shown that CGRP has trophic effects on the pancreas, myotubules, motor neurons and peripheral nerves (Ref. Reference Ponery10). In rodent models, CGRP ameliorates β-cell destruction and reduces the occurrence of type 1 diabetes (Ref. Reference Sun120). The number of CGRP-immunoreactive cells was significantly decreased in a rat model of type 1 diabetes (Ref. Reference Wharton105). CGRP levels are also lowered in the serum of STZ-induced hyperglycaemic rodents (Ref. Reference Boer98). Impaired CGRP expression has also been shown in the hearts of diabetic STZ mice (Ref. Reference Morrison, Dhanasekaran and Howarth121).

CGRP and the heart

CGRP is found in the human heart, where it exerts complex cardiovascular effects including a protective effect against heart failure by curtailing the workload of the heart (Ref. Reference Creager122). CGRP supports the heart by inducing potent vasorelaxation by the release of NO and cyclic guanosine monophosphate (cGMP) (Ref. Reference Parlapiano119), which protects myocytes and endothelial cells from damage (Ref. Reference Clementi123), and modulating the immune system to reduce inflammation (Ref. Reference Wu124). In rats, the cardiovascular protection of nitroglycerin is partly modulated by the release of endogenous CGRP (Ref. Reference Li125). In a recent rat cardiac ischaemia-reperfusion study, pretreatment with CGRP improved cardiac contractility and overall outcome (Ref. Reference Liu126). Similarly, as mentioned earlier in a rat study, SP- and CGRP-induced postconditioning significantly prevented both nondiabetic and diabetic hearts from ischaemia–reperfusion injury. Ischaemic postconditioning markedly increased CGRP and SP release in nondiabetic hearts, but failed to affect CGRP and SP release in diabetic hearts, indicating that the loss of cardioprotection by ischaemic postconditioning during diabetes is partly associated with failure to release CGRP and SP (Refs Reference Ren106, Reference Covino and Spadaccio127). Clinical studies show that, in addition to cardiac effects, CGRP increases angiogenesis by increasing VEGF-A, basic FGF (bFGF) and transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) in a hind-limb ischaemia model (Ref. Reference Mishima128). Thus, CGRP not only improves cardiac function, but can also facilitate recovery postischaemia by increasing capillary formation and cardiac blood flow.

These studies show that in the heart and vasculature, CGRP is similar to SP in expression and activity and can affect the cardiovascular system in a positive manner. Therefore, in diabetes, where CGRP is found to be decreased, the effects on the cardiovascular system and, more specifically, recovery post-ischaemia can be significantly hampered. There are fewer studies of CGRP in diabetes models compared with studies on SP; however, similarities in the effects of CGRP and SP suggests that CGRP supplementation could prove to be beneficial in the treatment of cardiovascular dysfunction of diabetes.

Natriuretic peptides

NPs are comprised of three structurally related molecules: ANP, BNP and CNP (Ref. Reference Levin, Gardner and Samson129). NPs have three discrete receptors, A-type natriuretic receptor (NPRA), B-type natriuretic receptor (NPRB) and C-type natriuretic receptor (NPRC) (Ref. Reference Hirose, Hagiwara and Takei130). ANP and BNP are cardiac peptides, released from atrial and ventricular myocytes, and bind to NPRA and NPRB, whereas expression of CNP is limited to the CNS and it selectively binds NPRC (Ref. Reference Barr, Rhodes and Struthers131). Moreover, these receptors are homodimeric and catalytic and have guanylyl activity on the intracellular domain of the protein sequence (Ref. Reference Garg and Pandey132). NPRA and NPRB are linked to guanylyl cyclases, leading to the production of cGMP, which in turn leads to relaxation of smooth muscle cells and cardiomyocytes (Ref. Reference Nakayama133). NPRAC is a GPCR that removes NPs from the circulation and is often termed a ‘clearance’ receptor (Ref. Reference Levin, Gardner and Samson129). These peptides have potent natriuretic, diuretic and vasodilating activities, and regulate vessel size, ventricular hypertrophy, pulmonary hypertension, fat metabolism, fluid egress, increased glomerular filtration, and salt and water excretion (Ref. Reference Potter134). NPs impede the action of angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE), angiotensin II, NEP, aldosterone and vasopressin (Refs Reference Struthers135, Reference Nonoguchi, Sands and Knepper136).

NPs and diabetes

NPs have antioxidant activity that inhibits oxidative stress and ameliorates the endothelial dysfunction of diabetes in a rat model (Ref. Reference Woodman137). In several studies, dysfunction of natriuretic peptide receptors has been observed in STZ diabetic rats (Refs Reference McKenna11, Reference Chattington138, Reference Sechi139, Reference Walther, Schuitheiss and Tschope140). Impairment of NPRA uncoupling is involved in diabetic heart failure (Ref. Reference Ganguly141), and the expression of NPRA receptors is reduced in diabetic rat kidneys (Ref. Reference Sechi139). BNP has been shown to be a reliable predictor of patients with type 2 diabetes and is a potential marker of diastolic heart failure (Ref. Reference Bhalla142). Heart failure patients with diabetes have elevated BNP levels compared with patients without diabetes (Ref. Reference van der Horst143). In a recent study, the gene encoding NPRC was found to have different single-nucleotide polymorphisms in diabetic patients, one of which significantly correlated with increased systolic blood pressure in this population (Ref. Reference Saulnier144).

These studies indicate that not only NPs, but also their receptors, are significantly affected in diabetes. Although related, ANP and BNP have very distinct profiles and yet both are good predictive tools in diabetic heart failure patients.

NPs and the heart

NPs have a vital role in congestive heart failure (Ref. Reference D'Souza111). Natriuretic peptide receptors (NPRs) are located on the endocardial endothelium and might be involved in regulating myocardial contractility (Ref. Reference Kim, Cho and Kim58). It has also been shown that NPs reduce myocardial load and enhance systolic and diastolic function in normal hearts and in failing hearts of canines (Ref. Reference Lainchbury145). ANP exerts cardioprotective functions, not only as a circulating hormone, but also as a local autocrine or paracrine factor as shown in an in vitro study of endothelial and vascular smooth muscle cells (Ref. Reference Morishita146). In vitro models demonstrate that it has antihypertrophic and antifibrotic functions and that it inhibits apoptosis and proliferation (Ref. Reference Thomas, Head and Woods147). These results are corroborated in a mouse model that lacks NPRA and hence develops cardiac hypertrophy and fibrosis (Ref. Reference Oliver148). Moreover, ANP attenuates RAAS, sympathetic nerve activity and reperfusion injury, averts LV remodelling and improves LV function in patients with acute myocardial infarction (Ref. Reference Kasama149). In addition to inhibiting RAAS, ANP also inhibits NEP, the enzyme that breaks down SP (Ref. Reference Struthers135). Thus ANP can indirectly increase the levels of SP. Omapatrilat, a pharmacological dual inhibitor of NEP and ACE, is a promising agent for the treatment of hypertension, heart failure and renal failure, as demonstrated in a rat study (Ref. Reference Backlund150). This suggests that ANP, which is an endogenous dual inhibitor, might have the same beneficial effects. In canines, blockade of ANP accelerates the progression of heart failure and postmyocardial infarction (Refs Reference Stevens151, Reference Lohmeier152).

In patients, plasma BNP is an important prognostic marker for the outcome of acute congestive heart failure and is a biomarker for myocardial ischaemia (Refs Reference Barrios153, Reference Nadir154). The level of BNP is generally higher in patients with worse outcomes (Ref. Reference Atisha155). Moreover, the plasma concentration of BNP is also typically increased in patients with asymptomatic or symptomatic LV dysfunction (Ref. Reference Atisha155). In contrast to these studies, short-term administration of subcutaneous BNP during the evolution of LV dysfunction in a canine model resulted in considerable improvement in cardiovascular haemodynamics (Ref. Reference Chen156).

Therefore, similarly to NPY, it is not clear whether low or high levels of ANP and BNP are desired for cardioprotection. In diabetes, there is decreased expression and activity of ANP, and thereby a loss of cardioprotection; therefore, supplementing exogenous ANP might be cardioprotective. In most studies of diabetes and cardiovascular disease, there is increased expression and activity of BNP. However, because of contradictory results, it is not clear whether inhibition or supplementation of BNP will have a positive effect on the cardiovascular system. Therefore, more in vivo studies need to be performed to analyse the role of BNP in diabetes and associated cardiovascular dysfunctions.

Summary

These studies show that the role of neuropeptides in diabetic heart failure is not established and the results are sometimes disparate. Table 1 summarises what we currently understand about the role of neuropeptides in diabetes and the cardiovascular system. Among the neuropeptides, NPY has received the most attention in both diabetes and cardiovascular diseases. Yet, it is not clear whether NPY has an protective or pathological role in cardiac dysfunction. The sensory neuropeptide SP has an undisputed protective role in the cardiovascular system, and in diabetes it is known to be consistently downregulated. Therefore, it could serve as a key therapeutic target in the treatment of diabetic heart failure. CGRP, similarly to SP, might have a cardioprotective role and would therefore also serve as a good therapeutic target in the treatment of diabetes-associated heart failure. However, studies investigating the role of CGRP in diabetes-associated cardiovascular dysfunction are few, and hence the role of CGRP needs more analysis. NPs also have very important roles in the cardiovascular system, but their role in diabetes remains unclear. ANP has been shown to be cardioprotective, but the role of BNP is not fully understood. Thus, BNP also warrants deeper scrutiny.

Table 1 Role of neuropeptides and their receptors in diabetes and the cardiovascular system

Abbreviations: ANP, atrial natriuretic peptide; BNP, brain natriuretic peptide; CGRP, calcitonin-gene-related peptide; CHF, chronic heart failure; CNP, C-type natriuretic peptide; LV, left ventricular; NPs, natriuretic peptides; NPRA, A-type natriuretic receptor; NPY, neuropeptide Y; RAAS, renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system; SP, substance P.

The role of neuropeptides in other diabetic complications, such as wound healing, has been examined much more aggressively. Scientists investigating diabetic heart failure might find neuropeptide wound-healing studies useful for designing cardiovascular research models. In wound-healing studies, neuropeptides have been shown to affect the immune system by regulating immune cell trafficking and cytokine signalling (Ref. Reference Jain57). Perhaps neuropeptides can similarly regulate neuroinflammation in the cardiovascular system and, more importantly, in the myocardium. Therefore, we hypothesise that neuropeptide dysregulation is the common mechanism underlying wound healing and cardiovascular dysfunction in diabetes. Diabetes causes activation of polyol pathways, generation of AGEs and oxidative stress, and a dysfunctional immune response. All these factors contribute to the development of autonomic neuropathy. Diabetes also causes vascular and cardiac disease, sometimes independently. It is our hypothesis that diabetic neuropathy causes neurohormonal dysfunction, leading to dysregulation of neuropeptides and neuroinflammation. Neuropeptide dysregulation, either directly or perhaps by dysregulated neuroinflammation, contributes to vascular and cardiac dysfunction by modulating vascular tone, impairing angiogenesis, causing cardiomyopathy and LV hypertrophy, and affecting systolic and diastolic functions. Finally, these cardiovascular dysfunctions can lead to heart failure (Fig. 2).

Conclusion

Diabetic heart failure is a significant and debilitating health problem that has a negative impact on both quality of life and survival. A review of existing literature suggests that diabetic neuropathy can lead to neuropeptide dysregulation and thereby has very important role in the pathophysiology of heart failure. Reducing the incidence of cardiac autonomic neuropathy or modulating neuropeptide and receptor function in diabetes directly might curtail cardiac dysfunction and heart failure. Understanding the complexity of neuropeptide function is a step towards identifying a therapeutic plan. For these reasons, further studies are warranted to delineate more precisely the role and signalling mechanisms of neuropeptides in diabetic heart failure.

Acknowledgements and funding

We thank the peer reviewers for their constructive criticism, time and effort. This work was funded in part by the William J. von Liebig Foundation.