The CCAAT/enhancer-binding proteins (C/EBPs) are a family of b-ZIP transcription factors that are exclusively eukaryotic and bind as dimers to sequence-specific, double-stranded DNA to regulate gene transcription. The C/EBP family has important roles in cellular proliferation and differentiation, survival and/or apoptosis, metabolism, inflammation and transformation, and oncogene-induced senescence and tumorigenesis (Refs Reference Cao, Umek and McKnight1, Reference Diehl2, Reference Poli3, Reference Zahnow4, Reference Ramji and Foka5, Reference Sebastian and Johnson6). They share a highly conserved, C-terminal, leucine-zipper dimerisation domain, adjacent to a basic DNA-binding region, together referred to as b-ZIP (Fig. 1a,b). The N-terminal domain is less conserved, but contains three short motifs, referred to as activation domains (Refs Reference Kowenz-Leutz7, Reference Williams8, Reference Angerer9, Reference Williamson10), which interact with transcriptional coactivators (Ref. Reference Mink, Haenig and Klempnauer11) and components of the basal transcription apparatus (Ref. Reference Nerlov and Ziff12) (Fig. 1a). Numerous regulatory regions that hold C/EBPβ in an intrinsically repressed state and inhibit its transcriptional activity have also been identified. For example, seven conserved regions (CR1–CR7) have been described, and two of these motifs, CR5 and CR7 (Fig. 1a), are known to interact with the N-terminal activation domains to inhibit the transcriptional activity of C/EBPβ (Ref. Reference Kowenz-Leutz7). In addition, two inhibitory regulatory domains (RD1 and RD2) have been identified; RD1 constitutively inhibits the transactivation potential of C/EBPβ by inducing a closed conformation that prevents access to the activation domains, whereas RD2 inhibits C/EBPβ binding by inducing a conformation that interferes with the ability of the basic region to interact with DNA (Ref. Reference Williams8). Phosphorylation or deletion of these inhibitory domains leads to activation of C/EBPβ and increased transcriptional activity (Refs Reference Kowenz-Leutz7, Reference Williams8).

Figure 1. Structure of CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein β. The position and size of the activation domains (AD) (orange), the negative regulatory domains (RD) (pink) and the conserved regions (CR) are approximated. The basic DNA-binding region and the leucine zipper are indicated in green and yellow, respectively. The amino acid numbers on the left refer to the position of the relevant initiation codon within the open reading frame of the mouse sequence. The full-length LAP1, and smaller LAP2 and LIP isoforms are shown.

The C/EBP family consists of six members: C/EBPα, C/EBPβ, C/EBPδ, C/EBPε, C/EBPγ, and C/EBPζ that were renamed using Greek nomenclature to indicate the chronological order of their discovery (Ref. Reference Cao, Umek and McKnight1) (Table 1). The protein for the founding member C/EBPα, was purified from rat liver in the mid-1980s by double-stranded DNA-affinity chromatography and interactions with the CCAAT box DNA motif (Refs Reference Graves, Johnson and McKnight13, Reference Johnson14). The cDNA for C/EBPα was cloned soon thereafter (Ref. Reference Landschulz15) and led to the identification of the second member of the family, C/EBPβ, (Refs Reference Descombes16, Reference Chang17, Reference Akira18, Reference Poli, Mancini and Cortese19) and an emerging family of C/EBP proteins.

Table 1. Genes encoding CCAAT/enhancer-binding proteins in rodents and humans

Abbreviations: AGP/EBP, α-1 acid glycoprotein/enhancer-binding protein; CBF, core binding factor; Chr. no., chromosome number; CELF, C/EBP-like factor; C/EBP, CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein; CHOP, C/EBP homologous protein; CRP, C-reactive protein; DDIT, DNA-damage-inducible transcript; GA, locus GA15; GADD, growth arrest and DNA-damage-inducible gene; GPE-BP, G-CSF promoter-element-binding protein; IL, interleukin; NF, nuclear factor; TCF5, transcription factor 5.

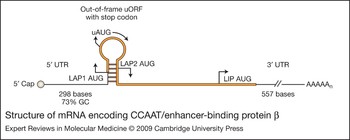

C/EBPα, C/EBPβ, C/EBPδ and C/EBPγ are encoded by intronless genes, whereas the genes for C/EBPε and C/EBPζ contain introns. C/EBPδ, C/EBPγ and C/EBPζ (CHOP, C/EBP homologous protein) are each translated as a single protein, but C/EBPα (p42, p30) and C/EBPβ (LAP1, LAP2 and LIP) are translated as multiple proteins, either by leaky ribosome scanning and the alternative use of multiple translation initiation codons in the same mRNA (Fig. 2), or via regulated proteolysis to generate LIP (Refs Reference Descombes and Schibler20, Reference Ossipow, Descombes and Schibler21, Reference Calkhoven, Muller and Leutz22, Reference Xiong23, Reference Lin24, Reference Welm, Timchenko and Darlington25). C/EBPε is also expressed as multiple isoforms (p32, p30, p27, p14); however, the mechanism involves differential splicing and the alternative use of promoters (Ref. Reference Yamanaka26).

Figure 2. Structure of mRNA encoding CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein β. C/EBPβ is translated into several distinct protein isoforms (LAP1, LAP2 and LIP) whose expression is regulated by the alternative use of several in-frame translation start sites (Ref. Reference Descombes and Schibler20). The 5′ end of C/EBPβ mRNA contains a 5′UTR of 298 bases with a GC content of approximately 73%, which has the potential to form complex, stable secondary structures that can interfere with scanning ribosomes (Refs Reference Kozak188, Reference Raught189). An upstream AUG (uAUG) and a small open reading frame (uORF) are also located in a hairpin loop of 5′ C/EBPβ mRNA between the translation initiation sites for LAP1 and LAP2. This region is crucial for the translational control of the C/EBPβ LAP2 and LIP isoforms (Refs Reference Lincoln190, Reference Calkhoven, Muller and Leutz22, Reference Xiong23, Reference Baldwin, Timchenko and Zahnow102). LAP1 is translated by initiation of the ribosomes at the LAP1 AUG codon. LAP2 is translated by leaky ribosome scanning through the uORF AUG followed by initiation at the LAP2 AUG site. Initiation at the uAUG and translation of the uORF may prevent ribosome reinitiation at the LAP 2 AUG because of the close proximity of the uORF AUG to the LAP2 AUG. However, in some instances, immediate reinitiation after translation of the uORF may occur and this has also been proposed as a potential mechanism (Ref. Reference Calkhoven, Muller and Leutz22). LIP is then translated by leaky ribosome scanning over the LAP1 AUG, followed by initiation of the uORF AUG, and ribosomal reinitiation at the LIP AUG (Ref. Reference Xiong23). Although LIP expression is often regulated by the 5′UTR/sORF (Ref. Reference Calkhoven, Muller and Leutz22), there have also been reports that LIP expression can be regulated in a manner that is independent of the 5′UTR/sORF and that LIP protein stability may be regulated by an undefined post-translational mechanism (Ref. Reference Li191).

The C/EBPs must dimerise to bind DNA (Refs Reference Vinson, Sigler and McKnight27, Reference Agre, Johnson and McKnight28), and in the presence of DNA, the basic region assumes an α-helical configuration and the protein structure becomes stabilised (Ref. Reference Moll29). Because the bZIP domain is conserved, all the C/EBPs are capable of forming intrafamilial homodimers or heterodimers with each other. With the exception of C/EBPζ (CHOP), all C/EBP dimers bind to the same DNA consensus sequence, RTTGCGYAAY, where R is an A or G, and Y is C or T (Ref. Reference Osada30). Although C/EBPζ can dimerise with other C/EBPs, it contains two proline residues in the basic region that disrupt its ability to bind to DNA at the C/EBP consensus site (Ref. Reference Ron and Habener31). Consequently, C/EBPζ normally acts to inhibit the binding of other C/EBP family members to DNA; however, C/EBPζ–C/EBP heterodimers can activate genes during conditions of cellular stress via the consensus sequence PuPuPuTGCAAT(A/C)CCC, where Pu represents a purine (Ref. Reference Ubeda32). Thus, C/EBPζ can either inhibit or activate gene transcription depending upon the cellular conditions. C/EBPγ can also inhibit gene transcription, but in a manner quite different to that of CHOP. C/EBPγ lacks the N-terminal activation domain and can still dimerise and bind to DNA, but blocks gene transcription in a dominant-negative manner by forming inactive heterodimers with C/EBP family members (Ref. Reference Cooper33). Similarly, of the four C/EBPε isoforms (p32, p30, p27, p14), the 30 kDa product has a lower transactivation potential than the 32 kDa form, and the 14 kDa isoform lacks the N-terminal activation domain and thus serves as a dominant negative (Refs Reference Yamanaka26, Reference Lekstrom-Himes34). This pattern of decreased activity in the smaller C/EBP isoforms is seen with C/EBPα. The C/EBPα 30 kDa isoform has a lower activating potential than the larger 42 kDa protein (Ref. Reference Ossipow, Descombes and Schibler21). The C/EBPβ isoforms will be discussed at greater detail later in this review. The smaller LAP2 isoform (34 kDa) is normally a stronger transactivator than the full-length LAP1 (38 kDa), and LIP (20 kDa) lacks the N-terminal activation domains and often functions as a dominant negative. Several reviews on C/EBP structure and function have been published (Refs Reference Zahnow4, Reference Ramji and Foka5, Reference Grimm and Rosen35, Reference Vinson36, Reference Takiguchi37).

Taken together, this information demonstrates that the transactivation potential of each C/EBP isoform can be quite different, and that heterodimerisation among C/EBP family members can result in a myriad of regulatory effects on gene expression. Moreover, the participants in a C/EBP heterodimer or homodimer are subject to variability and are dependent upon the availability of each family member. Species-specific and tissue-specific differences in C/EBP expression, physiological or pathophysiological stressors, and extracellular mediators that acutely regulate C/EBP expression might all play a role in regulating dimer composition and formation.

This review will focus on the family member C/EBPβ, the regulation of its activity by post-translational modification, and the individual actions of the C/EBPβ isoforms (LAP1, LAP2, and LIP). This review will also consider the role of LAP1, LAP2 and LIP in breast cancer and their associations with receptor tyrosine kinase signalling. Unfortunately, numerous published reports included in this review, have not specifically identified the C/EBPβ isoform(s) in their study as either LAP1, LAP2 or LIP, but simply refer to them as C/EBPβ. In these cases, the authors are probably referring to the more abundant and active LAP2 isoform, but might also be examining both LAP1 and LAP2 without discrimination.

Post-translational modifications of C/EBPβ protein

Phosphorylation

Post-translational modifications such as, phosphorylation, acetylation, methylation and sumoylation, play crucial roles in the regulation of C/EBPβ binding, transcriptional activity, protein–protein interactions and subcellular localisation (Fig. 3a and Table 2). C/EBPβ is normally maintained in a repressed state by negative regulatory domains, which sterically inhibit its transactivation domains (Refs Reference Kowenz-Leutz7, Reference Williams8). Phosphorylation within the inhibitory domains can abolish this repressive effect, and in many cases, leads to an increase in the transcriptional activity of C/EBPβ. C/EBPβ phosphorylation occurs on numerous residues and is regulated via numerous signalling pathways, which include: Ras–MAPK (Refs Reference Nakajima38, Reference Zhu39, Reference Mo40), growth factors and glycogen synthase kinase 3β (GSK3β) (Refs Reference Liao41, Reference Piwien-Pilipuk42, Reference Tang43), Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase (Ref. Reference Wegner, Cao and Rosenfeld44), ribosomal S6 kinase (Refs Reference Buck45, Reference Buck46), protein kinases A and C (Refs Reference Metz and Ziff47, Reference Trautwein48, Reference Trautwein49, Reference Mahoney50, Reference Chinery51), and the cyclin-dependent kinase pathway CDK1–CDK2–CCNA2 (cyclinA) (Refs Reference Shuman52, Reference Tang43). For a list of the phosphorylated residues, effectors and cell types see Table 2.

Figure 3. Post-translational processing of CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein β. The structural domains of C/EBPβ are identical to those shown in Fig. 1. (a) Phosphorylated serine (Ser) or threonine (Thr) are indicated with a vertical line and a number that denotes the approximate position of the phosphorylated amino acid in either the mouse (M), rat (R) or human (H) C/EBPβ protein sequence. Acetylated lysine residues are depicted as circles labelled Ac below a lysine (Lys), indicating its position in the mouse (M) sequence. The sumoylation site is represented with a red triangle, and the position of Lys residues in mouse (M) or human (H) is shown. The methylation of Lys39 is shown as a large green circle labelled M in either the chicken (C), mouse (M) or rat (R) sequence. (b) The location of the cysteine residues and the resulting disulfide bridges are shown for the mouse C/EBPβ protein sequence.

Table 2. CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein β phosphorylation sites

Abbreviations: CCl4, carbon tetrachloride; DKO, double knockout, GSK 3β; glycogen synthase kinase 3 beta; HSCs, hepatic stellate cells; MAPK, mitogen-activated protein kinase, TGF-α, transforming growth factor α; TPA, 12-O-tetradecanoyl-phorbol-13-acetate.

Acetylation

Acetylation can also regulate the transcriptional activity of C/EBPβ (Fig. 3A) and C/EBPβ-responsive promoters are often differentially sensitive to different C/EBPβ acetylation profiles (Ref. Reference Cesena53). For example, growth hormone stimulates acetylation of C/EBPβ at Lys39 (Fig. 3A), which increases the ability of C/EBPβ to mediate transcription of Fos (Ref. Reference Cesena53), whereas deacetylation of Lys39 by histone deacetylase 1 (HDAC1) decreases the C/EBPβ-mediated transcription of target genes involved in adipogenesis (Ref. Reference Cesena54). Moreover, during glucocorticoid-stimulated preadipocyte differentiation, C/EBPβ is acetylated at Lys98, Lys101 and Lys102 by the acetyl transferases GCN5 and PCAF, and this leads to a decrease in the interaction of HDAC1 with C/EBPβ (Ref. Reference Wiper-Bergeron55). By contrast, acetylation at Lys215 or Lys216 decreases the binding activity of C/EBPβ on the DNA-binding protein inhibitor ID1 promoter, but deacetylation by HDAC1 can restore its transcriptional activation (Ref. Reference Xu56).

Methylation

The Lys39 residue in C/EBPβ not only serves as a substrate for acetylation, but also as a target for methylation. The histone lysine N-methyltransferase, H3 lysine-9-specific 3 (G9a) has been found to interact directly with Lys39 (Fig. 3A) in the N-terminal activation domain of C/EBPβ (Ref. Reference Pless57). This interaction results in methylation of Lys39 and repression of C/EBPβ transcriptional activity (Ref. Reference Pless57). Phosphorylation of C/EBPβ seems to disrupt the interactions with G9a and to antagonise methylation. Lys39 thus serves as a target for either methylation or acetylation, is conserved in mouse, rat and chicken C/EBPβ, and appears to serve an important regulatory role in C/EBPβ transcriptional activity.

Sumoylation

Sumoylation is a reversible, post-translational modification that involves the covalent attachment of a small ubiquitin-like modifier (SUMO) protein to its substrate. Sumoylation regulates gene expression by altering the subcellular localisation, nucleocytoplasmic trafficking, stability, activity and interactions of target proteins in both the nucleus and cytoplasm of most cells. Sumoylation of transcription factors most often leads to repression of transcriptional activity, but enhanced activity has been reported. C/EBPβ is a SUMO target and modification by sumoylation usually impairs its transcriptional activity. A conserved, five amino acid motif (I/V/L-KXEP), located within the first inhibitory domain (RD1) of C/EBPβ, contains a lysine residue (Lys132 in mouse, Lys173 in human) (Fig. 3a) that is the covalent site of attachment for SUMO1 and SUMO2/3 (Refs Reference Melchior58, Reference Eaton and Sealy59). SUMO2/3 targets only the full-length C/EBPβ-LAP1 isoform, and impairs the ability of LAP1 to activate the cyclin D1 gene (CCND1) promoter without altering the subcellular location of LAP1 (Ref. Reference Eaton and Sealy59). In murine T cells, sumoylation of C/EBPβ and redistribution of nuclear C/EBPβ to a more pericentric heterochromatin location, interferes with the C/EBPβ-mediated repression of Myc expression but has no effect on the C/EBPβ-mediated activation of the IL4 gene (Ref. Reference Berberich-Siebelt60).

Actions of C/EBPβ

C/EBPβ regulates the development of many tissues, and genetically engineered mouse studies have provided much insight into the diverse biological actions of C/EBPβ. Unfortunately, few mouse models have been developed to study the actions of the individual C/EBPβ isoforms. For example, C/EBPβ-knockout mouse models lack all three C/EBPβ isoforms, and although 50-70% of the homozygous C/EBPβ mice are viable on a mixed-strain background, these mice exhibit defects in numerous developmental processes (Table 3). By contrast, mice lacking only the 34 kDa LAP2 isoform have fewer developmental defects than null mice that lack all three isoforms – LAP1, LAP2 and LIP (Table 3). This finding is surprising in light of the fact that the LAP2 isoform is considered to be the most transcriptionally active of the C/EBPβ isoforms (Ref. Reference Williams8) and suggests that LAP1 and LAP2 might have distinct actions, and that LAP2 is not essential for C/EBPβ-mediated development in most tissues. The distinct actions of LAP1 and LAP2 are discussed below.

Table 3. Genetically engineered mouse models provide insight into the actions of the LAP1, LAP2 and LIP isoforms

aC/EBPβ−/− mice lack LAP1, LAP2 and LIP. Abbreviations: C/EBP, CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein; WAP, whey acidic protein.

Distinct functions of LAP1 and LAP2

The LAP1 and LAP2 isoforms differ from each other only in 21 amino acids at the N-terminus (Fig. 1b). This truncation of LAP2 is the result of internal translation initiation from the LAP2 alternative translational start codon, which is downstream of the LAP1 start codon (Figs 1 and 2). Numerous studies report that LAP2 is a stronger transactivator than LAP1, but the molecular mechanisms for this are unclear. The functional relevance of these N-terminal amino acids is still emerging, but the data thus far suggest that the N-terminal region may differentially regulate the activity of LAP1 and LAP2, in part via regulation of C/EBPβ protein tertiary structure and unique N-terminal protein–protein interactions.

The N-terminal region of LAP1 is important for recruitment of the nucleosome-remodeling complex SWI–SNF, which activates silenced genes via chromatin remodelling and increases access of transcription factors to their binding sites (Ref. Reference Kowenz-Leutz and Leutz61). Specifically, it was shown that the N-terminal region of LAP1 interacts with the vertebrate SWI2 homologues, hBRM (human brahma) and BRG1 (brm/SWI2-related gene), which comprise the functional core and mediate the assembly of the SWI–SNF complex (Ref. Reference Kowenz-Leutz and Leutz61). Although the LAP isoforms are known to cooperate with Myb to activate myeloid-specific genes such as mim-1 (MER1-repeat-containing imprinted transcript 1) (Refs Reference Ness62, Reference Burk63), the recruitment of the SWI–SNF complex is now suspected to be important for the LAP1–Myb interaction and the consequent regulation of a subset of myeloid genes (Ref. Reference Kowenz-Leutz and Leutz61).

Disulfide bond formation is also an important determinant of tertiary protein structure and protein activity. Murine LAP1, LAP2 and LIP contain six, five and two cysteines, respectively, which participate in disulfide-bridge formation (Ref. Reference Su64) (Fig. 3b). Specifically, the N-terminal, 21 amino acids of LAP1 contain a cysteine at position 11, which can form a disulfide bridge with Cys33. It was demonstrated in the murine macrophage-like cell line P388D1(IL1) that disruption of the Cys11–Cys33 disulfide bond by redox modification or reducing conditions alters the protein structure of LAP1, and enhances its DNA-binding activity. Thus, LAP1 is selectively activated through a redox switch to regulate the lipopolysaccharide-induced expression of the IL-6 gene, whereas LAP2 and LIP appear to be insensitive to similar changes in redox state (Ref. Reference Su64).

Pro-inflammatory stimuli such as LPS, IL-1β, IL-6 and TNF-α also induce the potent antioxidant enzyme, manganese superoxide dismutase (MnSOD), and C/EBPβ is important in the IL-1β-dependent regulation of MnSOD (Ref. Reference Qiu65). Specifically, LAP1 has been shown to activate MnSOD, whereas LAP2 and LIP block the IL-1β-dependent induction of MnSOD (Ref. Reference Qiu65). Moreover, LAP2 but not LAP1, is known to activate the CCND1 (cyclin D1) promoter (Ref. Reference Eaton66). The mechanism responsible for the differential activation of CCND1 by LAP2 involves sumoylation and inactivation of LAP1 via SUMO2/3 (Ref. Reference Eaton and Sealy59).

Specific N-terminal protein–protein interactions between LAP1 or LAP2 and other non-b-ZIP proteins are also important in the regulation of LAP1 and LAP2 activity. The N-terminal region of LAP1 contains a consensus motif that can interact with the EVH1 (enabled/VASP homology 1) domain of the Homer protein family (Ref. Reference Ishiguro and Xavier67), which is important in synaptogenesis, synapse function, receptor trafficking and axon pathfinding. Homer-3, which is expressed in thymus, interacts with its EVH1 domain to reduce the transactivation potential of LAP1 (Ref. Reference Ishiguro and Xavier67). Another example of the N-terminal 21 amino acids and their regulation of C/EBPβ–protein interactions is provided by the preferential binding of the transcription factor, Nopp140 with LAP2. The lack of a Nopp140 interaction with LAP1 results in a more active LAP2 and transcriptional activation of AGP1 (α1-acid glycoprotein) (Ref. Reference Lee68).

These data demonstrate that LAP1 and LAP2 have unique actions and that in specific cellular contexts the LAP1:LAP2 ratio may be important for regulation of gene expression. The lack of developmental defects in LAP2-null mice also suggests that LAP1 or LIP can functionally replace LAP2 during development.

LIP normally acts to repress transcription but can also serve as a transcriptional activator

A few mouse models have analysed the actions of LIP via tissue-specific targeting in transgenic mice. For example, targeted expression of LIP to the mouse mammary gland leads to hyperplasia and tumorigenesis (Ref. Reference Zahnow69), whereas expression of LIP in stromal or osteoblast cells results in osteopaenia, reduced bone formation (Ref. Reference Harrison70), malocclusion and incisor overgrowth (Ref. Reference Savage71). Although it was hypothesised that LIP acted as a dominant negative in these studies, transcriptional activation was not ruled out.

As a consequence of translation from a C-terminal AUG start codon, LIP lacks all of the activation domain modules (AD1, AD2, AD3) and much of the negative regulatory domain (RD1) normally found in the larger C/EBPβ-LAP isoforms (Fig. 1). LIP can thereby function to inhibit the transcriptional activity of other C/EBPs by competing for C/EBP consensus binding sites or by forming inactive heterodimers with other C/EBPs as a dominant negative (Ref. Reference Descombes and Schibler20). However, emerging evidence suggests that LIP can serve as a transcriptional activator in some cellular contexts, then the mechanism might include the interactions of LIP with other, non-C/EBP, transcription factors, such as glucocorticoid receptor, NF-κB, progesterone receptor B and the runt-related transcription factor Runx2.

LIP activates several genes involved in the acute-phase response. The lipopolysaccharide-mediated acute-phase response in mouse liver leads to a dramatic elevation in LIP, an increase in the LIP:LAP ratio and a LIP-mediated increase in transcription of the acute-phase gene ORM1, also known as α1-acid glycoprotein (AGP1) (Ref. Reference An72). Analyses have demonstrated that LIP preferentially binds to the acute-phase response element of the AGP1 promoter with an affinity that is higher than that for LAP (Ref. Reference An72). Early studies of the AGP1 promoter identified and mapped C/EBP consensus sites in the region of the glucocorticoid response element (Refs Reference Williams73, Reference Ratajczak74), and others showed that LAP and ligand-activated glucocorticoid receptor interact directly via protein interactions with the bZIP structure to synergistically transactivate AGP1 (Ref. Reference Nishio75). It is therefore possible that LIP activation of AGP1 gene expression occurs via protein interactions with the glucocorticoid receptor; however, this has yet to be confirmed.

C/EBPβ is also known as nuclear factor for interleukin-6 expression (NF-IL6) (Table 1), and was originally identified as an IL-1-induced transactivator of the IL6 gene (Refs Reference Isshiki76, Reference Akira18). Studies have shown that the bZIP domain of LIP is important for the LPS-induced transcription of an IL-6 promoter linked to a luciferase reporter in B lymphoblasts (Ref. Reference Hu77). Moreover, an intact NF-κB binding site on the IL6 promoter was found to be necessary for C/EBP activity (Ref. Reference Hu77), which agrees with an earlier study showing that C/EBPβ and NF-κB can synergistically activate the IL6 promoter (Ref. Reference Matsusaka78). Numerous studies have demonstrated an interaction between the leucine zipper region of C/EBP family members and the Rel-homology domain of NF-κB (Ref. Reference Stein, Cogswell and Baldwin79). Taken together, these data suggest that LIP may in part, activate the IL6 promoter via an interaction between the Rel-homology domain of NF-κB and the leucine-zipper region of LIP.

Another example of LIP as transactivator is the functional association of progesterone receptor-A (PR-A) and progesterone receptor-B (PR-B) with both LIP and LAP in endometrial stromal cells (Ref. Reference Christian80). LIP and PR-B physically bind and cooperate to activate luciferase reporter constructs containing progesterone-response elements (PREs) (Ref. Reference Christian80). Although LAP was unable to enhance PR-B-dependent transcription of PRE-responsive promoters, PR-A was found to enhance LAP transactivation of C/EBP-responsive promoters. Consequently, a predominance of LIP and PR-B will activate PRE-driven promoters, whereas increases in LAP and PR-A favour expression of C/EBPβ-dependent genes (Ref. Reference Christian80). Although interactions have been demonstrated between the progesterone receptor and RelA (NF-κB–p65) (Ref. Reference Kalkhoven81), it is unknown whether LIP or LAP cooperates with NF-κB on the PR-A or PR-B gene promoters.

LIP has also been shown to transcriptionally activate genes involved in osteoblast differentiation via interaction with Runx2. LIP expression is upregulated during osteoblast differentiation (Ref. Reference Hata82) and downregulated during adipocyte differentiation (Ref. Reference Tang, Otto and Lane83). During osteoblast differentiation, the LIP isoform interacts with and coactivates Runx2 to induce osteoblast differentiation while inhibiting adipogenesis (Ref. Reference Hata82). Because LIP lacks a transactivation domain, it requires an interaction with Runx2 to function as a transcriptional activator of genes involved in osteoblast differentiation, such as the osteocalcin gene [BGLAP, bone γ-carboxyglutamate (gla) protein]. Consequently, LIP is unable to promote osteoblast differentiation in the absence of Runx2, whereas the LAP proteins are capable of driving differentiation in a Runx2-independent manner (Ref. Reference Hata82).

Long-standing evidence suggests that LIP functions as a dominant negative on many promoters. However, evidence is emerging to support a role for LIP as a transcriptional activator of gene expression.

C/EBPβ in breast cancer

The gene encoding C/EBPβ (CEBPB) is not mutated in breast tumours. Few mutations have been identified in CEBPB, and those that do occur are not believed to contribute to epithelial cancers (Ref. Reference Vegesna84). Similarly, the Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute Cancer Genome Project (http://www.sanger.ac.uk/genetics/CGP/cosmic/) has identified CEBPB as a gene that does not contain somatic mutations in human cancers. CEBPB may, however, be amplified in a small subset of breast neoplasia. A gain at chromosomal 20q13.13, which contains CEBPB, has been found to be associated with lobular carcinoma in situ of the breast (Ref. Reference Mastracci85).

The expression level of C/EBPβ mRNA in cancer was queried using Oncomine Research, a cancer-profiling database (http://www.oncomine.org/) (Ref. Reference Rhodes86). Data analysis performed with the Oncomine 3.0 array database demonstrated that expression of C/EBPβ mRNA is not altered in breast cancer or in breast cancer cell lines compared with normal breast tissue. Other gene expression studies have also shown that C/EBPβ mRNA is unchanged and not altered in breast cancer upon stimuli such as oncogenic ErbB receptor activation (Refs Reference Alaoui-Jamali87, Reference van't Veer88). However, differences in C/EBPβ mRNA expression are observed among a few breast cancer subtypes. For example, Oncomine analysis showed that a significant, but modest increase in C/EBPβ mRNA is observed in oestrogen-receptor-negative breast cancers versus those tumours that are positive for the oestrogen receptor (Table 4) (Refs Reference Gruvberger89, Reference van de Vijver90, Reference Yang91, Reference Saal92, Reference Finak93). Additionally, an elevation in C/EBPβ mRNA is associated with metastatic breast cancer (Ref. Reference van de Vijver90), a high tumour grade (Refs Reference van't Veer88, Reference Ma94, Reference Finak93) and an overall poorer prognosis (Table 4) (Ref. Reference van de Vijver90).

Table 4. Oncomine Research Cancer-profiling Database

Abbreviations: C/EBP, CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein; ER, oestrogen (estrogen) receptor.

It is interesting to note that C/EBPβ mRNA levels are not elevated in most breast cancers compared with normal tissue, but are increased in a more-aggressive subset of tumours versus the less-aggressive tumours. These data are somewhat surprising given that CEBPB expression is primarily regulated via post-transcriptional mechanisms, and mRNA levels would not necessarily be expected to be regulated in breast tumours. Moreover, these data suggest that transcriptional control or regulation of mRNA stability may be a mechanism for CEBPB expression in more aggressive breast cancers. Finally, increases in C/EBPβ mRNA can lead to increased translation, increases in C/EBPβ isoform expression and significant elevations in the LIP:LAP ratio, all of which have been observed in oestrogen-receptor-negative, aneuploid, highly proliferative breast tumours that are associated with a poor prognosis (Refs Reference Zahnow95, Reference Milde-Langosch, Loning and Bamberger96). An increase in the LIP:LAP ratio has also been linked to a defective transforming growth factor β (TGF-β)-dependent cytostatic response in metastatic breast cancer cells (Ref. Reference Gomis97). In pleural effusion samples isolated from patients with metastatic breast cancer, this study found an elevation in the LIP:LAP ratio in proliferative tumour cells that had lost their TGF-β cytostatic response, whereas LAP expression was in molar excess in those samples with a normal cytostatic response to TGF-β (Ref. Reference Gomis97). The forced overexpression of LAP2 in cells expressing an elevated LIP:LAP ratio restored the TGFβ cytostatic response, and led to a significant reduction in the proliferative activity of these metastatic cells. The mechanism of LAP2 overexpression involves an association with the forkhead box protein FOXO and SMAD (mothers against decapentaplegic homologue) proteins to facilitate the activation of the cyclin-dependent kinase CDN2B, as well as the repression of Myc. Because an increase in LIP expression antagonises LAP2 activity, a high LIP:LAP ratio favours the inactivation of p15INK4b, activation of Myc and proliferative behaviour in metastatic breast cancer cells (Ref. Reference Gomis97). Taken together, these data suggest that C/EBPβ has an important role in aggressive, high-grade metastatic breast cancer and that C/EBPβ expression in these more-aggressive tumours might be regulated in part via changes in C/EBPβ mRNA and alterations in the translational regulation of C/EBPβ protein isoform expression.

Studies in genetically engineered mice have also identified a role for C/EBPβ in mammary gland development and breast cancer (Table 3). Transgenic mice that overexpress LIP in the mammary gland develop focal and diffuse alveolar hyperplasia as well as invasive and non-invasive carcinomas (Ref. Reference Zahnow69). Moreover, mammary glands from mice lacking C/EBPβ exhibit delayed ductal outgrowth, distended ducts, decreased branching, reduced secretory activity and decreased levels of the milk proteins β-casein and whey acidic protein (WAP) (Refs Reference Seagroves98, Reference Robinson99). Ductal epithelial cells from the C/EBPβ-null mice also showed decreased proliferation and an increase in the percentage of progesterone-positive (PR) cells compared with wild-type mice (Ref. Reference Seagroves100). Interestingly, no deleterious affects in mammary gland development were observed in C/EBPβM20A/M20A mice, which lack LAP2 expression (Ref. Reference Uematsu101). This result suggests that LAP2 is not essential for C/EBPβ-mediated mammary gland development and that LAP1 and LIP might be able to compensate for the loss of LAP2.

Moreover, in cell culture studies overexpressing LIP in mouse mammary epithelial cells (Ref. Reference Zahnow69), or fibroblasts (Ref. Reference Calkhoven, Muller and Leutz22), LIP overexpression leads to a lack of contact inhibition, resulting in proliferation and foci formation. Although we and others have shown that both LAP1 and LAP2 are expressed in non-malignant, human mammary cells such as MCF10A cells (Ref. Reference Baldwin, Timchenko and Zahnow102), and in tumours from breast cancer patients (Refs Reference Zahnow95, Reference Gomis97), others have shown that LAP1 is predominantly expressed in normal mammary cells, whereas LAP2 is restricted to dividing cells in both normal and neoplastic mammary epithelial cells (Ref. Reference Eaton66). Moreover, it was shown that overexpression of LAP2 in MCF10A cells leads to epithelial–mesenchymal transition and transformation (Ref. Reference Bundy and Sealy103). However, in light of the results in the TGF-β study, it appears that LAP2 expression can also induce senescence or growth arrest when expressed in breast cancer cells containing elevated levels of LIP (Ref. Reference Gomis97). Taken together, these data suggest that aberrant expression of the C/EBPβ isoforms can lead to aggressive breast cancer; however, the precise role of each individual isoform remains to be resolved.

Finally, C/EBPβ might indirectly contribute to breast cancer progression via regulation of aromatase expression in breast stromal tissue (Ref. Reference Zhou104) and multidrug resistance (Refs Reference Combates105, Reference Conze106, Reference Chen107). The multidrug transporter P-glycoprotein, encoded by MDR1, is associated with clinical multidrug resistance and a poor prognosis in breast cancer (Ref. Reference Leonessa and Clarke108). This gene is regulated by C/EBPβ in HepG2 hepatoma cells (Ref. Reference Combates105) and in MCF7 breast cancer cells (Ref. Reference Conze106) via an inverted CCAAT box (Y box) (Ref. Reference Chen107).

A role for C/EBPβ in cell survival, apoptosis and senescence

The role of C/EBPβ in cancer might be partly mediated via its actions in the regulation of cell survival and apoptosis. For example, C/EBPβ is important in the survival of hepatic stellate cells that have DNA damage as a result of CCl4-induced free-radical formation (Ref. Reference Buck46), and in macrophages, which require C/EBPβ expression for survival in response to Myc–Raf transformation (Ref. Reference Wessells, Yakar and Johnson109). C/EBPβ has also been shown to promote cell survival by reducing p53 expression and activity in response to DNA damage (Refs Reference Yoon110, Reference Ewing111). Reduced levels of C/EBPβ can thereby sensitise cells to apoptosis, as observed in C/EBPβ-null mice, which display resistance to DMBA-induced skin tumorigenesis via increases in apoptosis (Ref. Reference Zhu39).

In addition to its role in apoptosis, numerous studies have demonstrated that C/EBPβ has a role in oncogene-induced senescence. Senescence is a state of irreversible growth arrest and can act as a barrier to malignant transformation. It has been demonstrated that forced expression of LAP2 can lead to cell cycle arrest in hepatocarcinoma cells (Ref. Reference Buck, Turler and Chojkier112), keratinocytes (Ref. Reference Zhu113) and fibroblasts (Ref. Reference Johnson114). C/EBPβ also cooperates with RB/E2F to implement Rasv12-induced cellular senescence via an irreversible cell cycle arrest at the G1–S boundary (Ref. Reference Sebastian115). Finally, oncogene-induced senescence has been shown to involve C/EBPβ-dependent expression of a proinflammatory cytokine or chemokine secretory programme (Refs Reference Acosta116, Reference Kuilman117). In summary, C/EBPβ promotes the survival of some transformed cells while inducing growth arrest in others. Clearly, the regulation of survival, apoptosis and senescence by C/EBPβ is highly context specific and worthy of further investigation.

Receptor tyrosine kinases, C/EBPs and breast cancer

Receptor tyrosine kinase signalling contributes to the development of numerous cancers and the epidermal growth factor (EGF) receptor, fibroblast growth factor (FGF) receptor, insulin receptor (IR) and insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-I) receptor subfamilies in particular, have important roles in mammary tumorigenesis. The interactions between C/EBPβ and the EGF, FGF, IR and IGF-I receptor families and their relationship to breast cancer is discussed below.

Epithelial growth factor receptor family

The EGF family of receptor tyrosine kinases (ErbB1/EGFR, ErbB2, ErbB3 and ErbB4) are membrane-bound receptors with intrinsic ligand-activated, tyrosine kinase activity. Numerous growth factors bind to these receptors to initiate receptor dimerisation and the initiation of a kinase signalling cascade (Refs Reference Schlessinger118, Reference Hynes and Lane119, Reference Zahnow120). Both the ErbB receptors and ligands play important roles in mammary development and in breast cancer and each of the ErbB receptors, as well as numerous ligands, are often overexpressed in breast tumours (Refs Reference Walker and Dearing121, Reference Di Fiore122, Reference Allred123). In general, EGFR–ErbB1 signalling leads to increased LIP and LAP expression. In cultured mammary epithelial cells and in transgenic mice, ErbB1 (EGFR) signalling leads to an increase in C/EBPβ-LIP protein expression (Fig. 4a) by a mechanism that includes the increased binding and activation of the RNA-binding protein CUG-binding protein 1 (CUG-BP1) to C/EBPβ mRNA (Ref. Reference Baldwin, Timchenko and Zahnow102). In a rat model of secondary hyperparathyroidism, activation of EGFR via TGF-α leads to elevated LIP expression, an increase in the proliferative activity of parathyroid cells and a decrease in the expression of the vitamin D receptor (Ref. Reference Arcidiacono124). In human bronchial epithelial cells, lysophosphatidic acid activates EGFR signalling, which increases C/EBPβ-LAP expression and leads to expression of cytochrome c oxidase (COX2) and prostaglandin release (Ref. Reference He125). Unfortunately, LIP expression was not examined in this study. Taken together, these studies demonstrate that ErbB1–EGFR signalling can regulate the differential translation of the LAP and LIP isoforms, resulting in elevated LIP expression and an increased LIP:LAP ratio. Elevated LIP then contributes to the mitogenic effects of ErbB signalling by promoting proliferation and a more aggressive disease state. It remains to be determined whether LIP and LAP feedback to regulate EGFR expression.

Fibroblast growth factor receptor family

The FGF receptor family contains four receptor tyrosine kinases (FGFR1, FGFR2, FGFR3 and FGFR4) and 22 ligands that bind to and activate the various receptor isoforms (Refs Reference Dickson126, Reference Eswarakumar, Lax and Schlessinger127). FGFs are different from other growth factors in that they bind to heparin sulphates as well as an FGF receptor to form a ternary signalling complex (Ref. Reference Klagsbrun and Baird128). Strong evidence exists for a role of the FGF family in murine mammary tumorigenesis, and evidence in human breast cancer is slowly emerging (Ref. Reference Dickson126). In mouse studies, aberrant FGF signalling leads to hyperplastic growth and neoplasia (Refs Reference Tsukamoto129, Reference Welm130). Moreover, numerous FGFs and their receptors are overexpressed in malignant human breast tissue (Refs Reference Penault-Llorca131, Reference Dickson126, Reference Zammit132, Reference Tamaru133, Reference Theodorou134, Reference Reis-Filho135, Reference Meijer136, Reference Luqmani, Graham and Coombes137, Reference Hunter138, Reference Easton139).

Mapping studies have demonstrated that two single-base-pair changes in intron 2 of FGFR2 lead to increases in the binding of C/EBPβ (LAP) and Oct1/Runx2, and result in increased FGFR2 mRNA expression (Ref. Reference Meyer140) (Fig. 4b). Elevations in FGF2R expression are observed in oestrogen-receptor-positive breast cancer (Ref. Reference Luqmani, Graham and Coombes137) and an FGFR2 locus was recently found to be associated with a small, but significant increase in the risk of developing breast cancer (Refs Reference Hunter138, Reference Easton139). LAP and LIP also regulate the FGF-binding protein (FGFBP1) promoter in response to EGFR and p38 MAP kinase signalling (Ref. Reference Kagan141) (Fig. 4b). Binding of LAP to the FGFBP1 promoter results in increased promoter activity, whereas LIP inhibits promoter activity (Ref. Reference Kagan141). The binding actions of FGFBP1 lead to increases in the activity of FGF1 and FGF2, and cell lines expressing both FGFBP1 and FGF2 are more tumorigenic and angiogenic (Ref. Reference Czubayko142). Consequently, C/EBPβ appears to be important in the EGFR regulation of FGF activity as well as the regulation of FGFR2 expression in breast epithelial cells (Refs Reference Kagan141, Reference Meyer140). However, it is not yet known whether FGF signalling alters the LIP:LAP ratio.

Insulin-receptor family

The insulin, or insulin-like growth factor, family consists of three members: the insulin receptor, the insulin-like growth factor type 1 receptor (IGF-IR) and the insulin-receptor-related receptor (IRR). Both the insulin receptor (Refs Reference Papa143, Reference Holdaway and Friesen144, Reference Milazzo145, Reference Finlayson146) and the IGF-IR (Refs Reference Pekonen147, Reference Foekens148, Reference Bonneterre149, Reference Surmacz150) are activated and expressed at elevated levels in malignant breast tumours and in breast cancer cell lines. Similarly, elevated serum levels of insulin (Refs Reference Goodwin151, Reference Pasanisi152) and IGF-I (Ref. Reference Pasanisi153), which are ligands for the insulin receptor and IGF-I receptor, respectively, are associated with breast cancer recurrence and a poor prognosis. Although the insulin receptor mediates mostly metabolic effects and the IGF-IR mitogenic effects, both insulin and IGF-I are capable of inducing metabolic or mitogenic effects depending on tissue distribution, and concentration of receptors and ligands (Ref. Reference Papa, Costantino and Belfiore154). Additionally, there is substantial crosstalk between insulin and IGF-I with either ligand binding to either receptor.

C/EBPβ regulation of insulin levels and insulin receptor expression

Regulation of insulin

Expression of the insulin gene is controlled primarily at the level of transcription and C/EBPβ has been shown to be a glucose-induced inhibitor of insulin gene transcription in pancreatic β-cells (Refs Reference Lu, Seufert and Habener155, Reference Seufert, Weir and Habener156). Exposure of pancreatic β-cell lines to high glucose concentrations leads to an upregulation of C/EBPβ-LAP expression (Ref. Reference Lu, Seufert and Habener155) and a reduction in insulin expression (Fig. 4c). Likewise, in the pancreatic β-cell line RIN-5F, increased expression of LAP inhibits insulin expression, whereas expression of LIP has no effect (Ref. Reference Shen157). However, in non-β-cells the reverse is observed, and C/EBPβ-LAP expression stimulates insulin promoter activity and transcription via a C/EBPβ consensus binding motif (Fig. 4c) (Ref. Reference Lu, Seufert and Habener155).

In animal studies, C/EBPβ expression is upregulated in pancreatic islets during the development of diabetes mellitus in two rat models, the Zucker diabetic fatty (fa/fa) rat and rats subjected to 90% pancreatectomy (Ref. Reference Seufert, Weir and Habener156). The elevations in C/EBPβ expression, observed in response to sustained hyperglycaemia or hyperlipidaemia, appear to have a role in the downregulation of insulin gene expression during the development of diabetes mellitus (Fig. 4c). In mice, deletion of C/EBPβ is associated with increased insulin action and decreased fatty acid mobilisation in skeletal muscle, lower fasting blood glucose levels and an overall increase in whole-body insulin sensitivity (Ref. Reference Wang158).

Regulation of insulin receptor

In addition to insulin, C/EBPβ can regulate transcription of the insulin receptor (Fig. 4c) as part of a larger nuclear protein complex containing the transcription factors HMGI-Y and Sp1 in HepG2 cells (Ref. Reference Foti159). Taken together, these data suggest that C/EBPβ regulates insulin sensitivity via regulation of insulin levels or regulation of insulin receptor expression.

Insulin regulation of C/EBPβ expression and activity

Increased insulin signalling has been shown to regulate C/EBPβ expression in liver, adipocytes and muscle tissue. For example, treatment of fully differentiated 3T3-L1 adipocytes with insulin leads to transient increases in expression of LAP and LIP (Fig. 4c) (Refs Reference MacDougald160, Reference Le Lay161). Moreover, in liver tissue, both C/EBPβ LAP and LIP isoforms are rapidly increased in H4IIE rat hepatoma cells treated with 10 nM insulin (Ref. Reference Duong162); however, in diabetic mouse liver, LAP expression is downregulated by elevation of insulin concentration (Fig. 4c) (Ref. Reference Bosch, Sabater and Valera163). In vascular smooth muscle cells, an increase in insulin signalling can lead to the upregulation of nuclear C/EBPβ-LAP expression primarily via PI3K signalling (Ref. Reference Sekine164). Insulin signalling can suppress C/EBPβ-LAP activity (Fig. 4c) via a mechanism that includes the Akt-mediated phosphorylation of p300/CBP, followed by the disruption and removal of p300/CBP from the activation domain of C/EBPβ and a loss in the transactivation potential of C/EBPβ (Ref. Reference Guo165). In summary, C/EBPβ participates in a complex relationship with insulin signalling. Not only does C/EBPβ-LAP regulate insulin levels and expression of the insulin receptor, but insulin can also regulate C/EBPβ isoform expression and activity.

C/EBPβ regulation of IGF-I

In contrast to insulin signalling, less is known regarding the relationship between C/EBPβ expression and IGF-I signalling. For example, it is not known whether C/EBPβ regulates IGF-I receptor expression; however, loss of C/EBPβ (LAP1, LAP2 and LIP) expression has been shown to lead to a disrupted IGF-I axis in rodent studies (Ref. Reference Grimm166). In the mammary gland of C/EBPβ-null mice, the levels of IRS-1 are decreased and the expression pattern of IGF-BP5 and IGF-II are altered compared with wild-type mice (Fig 4D) (Ref. Reference Grimm166). Similarly, it is not known whether IGF-I signalling alters the LIP:LAP ratio; however, studies have shown that LAP expression can regulate IGF-I ligand levels. For example, in transformed bone-marrow-derived macrophages isolated from the C/EBPβ-knockout mouse, IGF-I expression is decreased in response to the loss of C/EBPβ expression (Fig. 4d) (Ref. Reference Wessells, Yakar and Johnson109). Similarly, in hepatocytes, the addition of C/EBPβ-LAP to the human hepatoma cell line Hep3B increases IGF-I expression (Ref. Reference Nolten167). Overexpression of LIP alone appears to have no effect on IGF-1 promoter activity, but does abolish the transactivation induced by LAP (Fig 4d) (Ref. Reference Nolten167). In HepG2 cells, the protein kinase C (PKC) pathway has been implicated in the control of IGF-I gene regulation via a C/EBP site in the IGF-I promoter (Ref. Reference Umayahara168). The mechanism involves the PKC-mediated activation of C/EBPβ at both the transcriptional and post-translational level followed by binding of C/EBPβ to the IGF-I gene promoter to induce transcription (Ref. Reference Umayahara168). The C/EBPs also have a role in the regulation of IGF-I expression in bone cells, and might act as transcriptional coupling factors to coordinate bone remodelling in response to osteotropic hormones (Refs Reference Umayahara169, Reference McCarthy170). In summary, the C/EBPβ isoforms, and in particular, LAP, play a positive role in regulating IGF-I ligand expression as well as various members of the IGF-I axis.

Figure 4. Generalised interactions between CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein β and receptor tyrosine kinases in several tissues. (a) EGFR (ErbB1) signalling leads to an increase in LIP expression and an increase in the ratio of LIP:LAP. (b) EGFR signalling regulates the binding of LIP and LAP to the FGFBP1 promoter and the ratio of LIP:LAP regulates FGFBP1 expression levels. FGFBP1 in turn can increase the activity of FGF1 and FGF2. LAP also binds to the FGFR2 promoter in a complex with Oct1–Runx2 to increase expression of FGFR2. (c) LAP expression reduces or increases insulin expression in pancreatic β cells and non-pancreatic β cells, respectively. In liver, LAP has been shown to regulate transcription of the insulin receptor as part of a larger complex containing the transcription factor HMGI-Y. In adipocytes and muscle, insulin signalling leads to increases in the expression of the LAP and LIP isoforms; however, in diabetic mouse liver, LAP expression is downregulated by elevation in insulin. (d) C/EBPβ-LAP upregulates IGF-I expression in liver, macrophages and bone. Overexpression of LIP alone has no effect on IGF-I gene promoter activity but can abolish the transactivation induced by LAP. The IGF axis is dysregulated in the mammary gland of the C/EBPβ-null mouse, and IRS levels decrease in the absence of C/EBPβ. Abbreviations: EGF, epidermal growth factor; FGF, fibroblast growth factor; FGFBP1, fibroblast growth factor binding protein-1; HMGI-Y, high-mobility group protein HMG-I/HMG-Y; IGF-I, insulin-like growth factor I; IRS, insulin-receptor substrate.

Clinical implications

C/EBPβ is considered to be a potential candidate for therapeutic intervention in epithelial cancers because of its role in the regulation of cell proliferation and differentiation, its associations with cancer and its non-essential cellular functions (Refs Reference Nerlov171, Reference Brennan, Donev and Hewamana172). However, transcription factors such as C/EBPβ are difficult to target because they belong to protein families with redundant, overlapping functions and numerous binding partners. Moreover, C/EBPβ acts as a convergence point to regulate numerous gene expression profiles and because of these wide-ranging cellular effects, target specificity remains a major challenge to the development of C/EBPβ therapies. Specificity issues have, however, been successfully addressed for numerous transcription factors or enzymes that have similar broad-reaching actions. In fact, many of these drugs are currently showing promise in clinical trials and are not eliciting the expected off-target effects. Examples of these agents are enzyme inhibitors to histone deacetylases (HDACs) (Ref. Reference Minucci and Pelicci173), histone acetyl transferases (HATs) (Refs Reference Liu174, Reference Zheng175), Erk signalling (Ref. Reference Kohno and Pouyssegur176) and PI3K–Akt–mTOR signalling (Ref. Reference Yuan and Cantley177), as well as inhibitors of the transcription factors NF-κB (Ref. Reference Gilmore and Herscovitch178), p53 (Ref. Reference Dey, Verma and Lane179), Stat3 (reviewed by Ref. Reference Mees, Nemunaitis and Senzer180) and the Notch pathway (Ref. Reference Rizzo181). Because C/EBPβ activity is regulated via post-translational phosphorylation, acetylation, sumoylation and methylation, numerous kinases, deacetylases, acetyltransferases, demethylases and methyltransferases, as described above, might soon become valuable targets in the regulation of C/EBPβ activity.

Another difficulty in targeting and regulating C/EBPβ activity is the lack of specificity in the interaction of C/EBPβ with DNA. The C/EBPβ DNA-binding site is a dyad symmetrical repeat, but substantial variations in sequence are common in most promoters and are well tolerated by C/EBPβ. To make matters worse, the CCAAT box motif is not specific to C/EBPβ, because most of the other C/EBP family members also bind to the same consensus sequence. Although specific targeting of the C/EBPβ binding site might prove to be one of the more difficult targeting strategies, agents have been designed to block transcription factor binding to DNA. As an example, a high-throughput fluorescent microscopy screen has been used to identify several small molecules that bind to the basic region of C/EBPβ and inhibit its binding to DNA (Ref. Reference Rishi182). The off-target effects and specificity of these agents remain to be examined. Despite the difficulties, advances in the targeting of transcription factors are being made, and several small molecules have been identified that successfully target the dimerisation of transcription factors, such as Stat3 (Ref. Reference Turkson183) and Myc (Ref. Reference Berg184), or protein–protein interactions, such as those between p53 and the E3 ubiquitin-protein ligase MDM2 (Refs Reference Vassilev185, Reference Efeyan186), and HIF-1α and the aryl hydrocarbon receptor nuclear translocator ARNT (Ref. Reference Olenyuk187).

Outstanding research questions

Since the identification of the C/EBPs nearly 20 years ago (Ref. Reference Landschulz15), numerous studies have revealed that the C/EBPs have pivotal roles in the control of cell fate, tissue development and malignant transformation. However, much still remains unknown regarding the individual and overlapping functions of each C/EBP family member and their protein isoforms. For example, the precise roles of LAP1, LAP2 and LIP in metastatic breast cancer are not clear and this makes it difficult to determine which isoform would represent the most effective therapeutic target. Mounting evidence suggests that LAP1, LAP2 and LIP have separate and distinct functions on some gene promoters and this is fascinating in light of the fact that all three bind to the same DNA-recognition sequence. Differences might exist in the binding partners for each isoform and the affinity or specificity of their binding to specific promoters. These questions will need to be addressed using endogenous genes and chromatin immunoprecipitation techniques coupled with proteomic analyses.

Studies in mice that either overexpress a particular C/EBP family member or are deficient for that C/EBP isoform have been crucial to our understanding of the importance of C/EBP in physiological and developmental processes such as metabolism, inflammation, immunity, haematopoiesis, diabetes, reproduction and cancer. Clearly, however, conditional knockouts, regulated knock-ins, and knockouts of more than one C/EBP family member will be necessary to decipher the functional redundancy that exists between C/EBPs as well as to identify the full range of actions for each C/EBP isoform. Progress has been made in our understanding of the molecular actions of the C/EBP superfamily but additional research should continue to focus on the characterisation of interacting proteins and transcriptional targets.

Acknowledgements and Funding

The author is currently funded by NIH grant R01 CA113795, the Susan G. Komen for the Cure Program, the Flight Attendant Medical Research Institute, the Hansen Foundation and the Johns Hopkins Breast Cancer Program. The author is grateful to Peter Johnson and Jeffrey Rosen for critical review of this manuscript and to the anonymous peer referees for their constructive comments. I apologise to all those authors whose work was not included in this review due to space limitations or oversight.