1 Introduction

Subsidies are a common way of incentivizing charitable giving. They typically take the shape of rebates, in which a third party (e.g., the government) refunds a fraction r of the gift back to the donor; or the shape of matches, in which a third party (e.g., a generous donor) supplements each donation at a rate m, such that the charity receives a total of

![]() times the original donation. Both rebates and matches have been extensively studied and several key findings have emerged in the literature (see Vesterlund Reference Vesterlund, Kagel and Roth2016; Epperson and Reif Reference Epperson and Reif2019, for comprehensive reviews). Probably the most notable result is that although rebates and matches imply the same price of giving if the corresponding subsidy rates r and m satisfy

times the original donation. Both rebates and matches have been extensively studied and several key findings have emerged in the literature (see Vesterlund Reference Vesterlund, Kagel and Roth2016; Epperson and Reif Reference Epperson and Reif2019, for comprehensive reviews). Probably the most notable result is that although rebates and matches imply the same price of giving if the corresponding subsidy rates r and m satisfy

![]() , overall donations received by the charity are higher under matches than under equivalent rebates (Eckel and Grossman Reference Eckel and Grossman2003, Reference Eckel, Grossman, Davis and Isaac2006a, Reference Eckel and Grossmanb, Reference Eckel and Grossman2008b, Reference Eckel and Grossman2017; Davis et al. Reference Davis, Millner and Reilly2005; Lukas et al. Reference Lukas, Grossman and Eckel2010; Bekkers Reference Bekkers, Deck, Fatas, Rosenblat, Isaac and Norton2015; Gandullia and Lezzi Reference Gandullia and Lezzi2018; Gandullia Reference Gandullia2019).Footnote 1 Another finding is that matching subsidies often significantly increase private contributions net of the subsidy compared to a no subsidy condition without a lead donor (Eckel et al. Reference Eckel, Grossman and Milano2007; Karlan and List Reference Karlan and List2007; Gneezy et al. Reference Gneezy, Keenan and Gneezy2014; Huck et al. Reference Huck, Rasul and Shephard2015; Eckel and Grossman Reference Eckel and Grossman2017).Footnote 2

, overall donations received by the charity are higher under matches than under equivalent rebates (Eckel and Grossman Reference Eckel and Grossman2003, Reference Eckel, Grossman, Davis and Isaac2006a, Reference Eckel and Grossmanb, Reference Eckel and Grossman2008b, Reference Eckel and Grossman2017; Davis et al. Reference Davis, Millner and Reilly2005; Lukas et al. Reference Lukas, Grossman and Eckel2010; Bekkers Reference Bekkers, Deck, Fatas, Rosenblat, Isaac and Norton2015; Gandullia and Lezzi Reference Gandullia and Lezzi2018; Gandullia Reference Gandullia2019).Footnote 1 Another finding is that matching subsidies often significantly increase private contributions net of the subsidy compared to a no subsidy condition without a lead donor (Eckel et al. Reference Eckel, Grossman and Milano2007; Karlan and List Reference Karlan and List2007; Gneezy et al. Reference Gneezy, Keenan and Gneezy2014; Huck et al. Reference Huck, Rasul and Shephard2015; Eckel and Grossman Reference Eckel and Grossman2017).Footnote 2

The literature has established these findings in a setting in which individuals are asked to decide how much money to give to a charity, arguably the most common scheme for soliciting donations. We refer to this as a money donation scheme. Yet another frequently applied strategy is to frame the donor’s choice variable not in terms of money, but in terms of physical units of a charitable good awaiting funding. A prominent example that has attracted donors from all over the world is ShareTheMeal, a smartphone app and initiative of the UN World Food Programme, which is used to provide food to children in need. Donors for ShareTheMeal do not simply choose an amount of money to give. Instead, they are informed that feeding one child for a day costs $0.80 and are then asked to indicate the number of feeding days (“meals”) that they would like to fund.Footnote 3 We refer to this alternative scheme as a unit donation scheme.

Do the key findings about the effects of matches and rebates in money donations generalize to the alternative unit donation scheme? In this paper, we examine the effect of subsidies on unit donations by conducting an online field experiment. We asked 558 subjects how many units of a charitable good they would like to provide to a predetermined charity, funded out of their reward for answering an unrelated online survey. The decision variable was framed in quantities of nutritional packages provided for malnourished children in South Sudan. The charity we worked with, Sign of Hope, provided this service for $0.50 per nutritional ration. This cost served as the unsubsidized unit price in our donation experiment. In the baseline, no subsidy was offered. The main treatments differed across three subsidy types and two subsidy rates. The first type, the rebate, was offered at a rate of either 33% or 50% such that a third party refunded to the subject about one third or one half of the reward she spent on nutritional packages. The second type, the match, was offered at a rate of 0.5 (1:2) or 1 (1:1) such that a third party added a nutritional package for either every two or each package donated. The third subsidy type is novel for the study of charitable giving and took the form of a per unit price discount of either 33% or 50% (with a third party covering the remaining cost). In other words, the unit was offered to subjects for either $0.33 or $0.25, instead of $0.50. This subsidy type is without a direct parallel in money donations.

The contribution of this paper is threefold. First, we define unit donations as a separate class of charitable donations distinct from money donations. Second, we investigate how rebates and matches perform in a setting of unit donations and compare the results to the established literature on money donations. Based on between-subjects evidence, our core result is that matches and rebates are equally effective in incentivizing private net donations and in generating total charity receipts. In other words, we do not replicate the superiority of matching subsidies observed in the case of money donations. Third, we check whether, in a setting of unit donations, the discount subsidy offers an attractive alternative to these subsidy types. We find that discounts are equally effective as matches and rebates when considering net donations or charity receipts. This may well be good news for charities: In a world in which subsidy types perform equally well, charities enjoy additional degrees of freedom in campaign design. At the same time, the different subsidy types perform differently when disaggregated into the extensive and the intensive margin of giving: Rebates are more effective than matches in attracting donors, but matches result in larger donations. Under discounts, the likelihood of giving is lower than under rebates, and on both margins, behavior corresponds to that under matches. We conclude that if attracting donors is a secondary objective of a fundraising campaign that uses unit donations, rebates merit additional consideration. New donors offer the possibility of an ongoing income stream for charities, since previous donors are more likely to give in the future (Eckel and Grossman Reference Eckel and Grossman2008b; Landry et al. Reference Landry, Lange, List, Price and Rupp2010).

The remainder of the paper is organized as follows. In a background section (Sect. 2), we contrast money and unit donations, explain the mechanics of subsidizing the latter, and review the relevant literature. Section 3 describes our experimental design, followed by a presentation of our main results in Sect. 4, and a discussion of potential explanations in Sect. 5. Section 6 concludes.

2 Background

2.1 Unit versus money donations

For our purposes, we define a money donation scheme as a solicitation scheme in which potential donors are asked to decide how much money to give to a charity. It is arguably the most common scheme for solicting donations. Academic papers in the lineage of the now classic donation models (Bergstrom et al. Reference Bergstrom, Blume and Varian1986; Andreoni Reference Andreoni1988, Reference Andreoni1989) capture its main features by generally assuming a linear production technology for the charitable public good and normalizing the per-unit price of both the private and the public good to one. In such models, the prospective donor i’s choice is to divide her endowment

![]() (in dollars) between private consumption

(in dollars) between private consumption

![]() (in dollars) and giving

(in dollars) and giving

![]() (in dollars) to the charitable good, G. Under a money donation scheme, therefore, the donor’s choice variable

(in dollars) to the charitable good, G. Under a money donation scheme, therefore, the donor’s choice variable

![]() is denominated in terms of monetary expenditures.

is denominated in terms of monetary expenditures.

By contrast, we define a unit donation scheme as a solicitation scheme that frames the donor’s choice variable in terms of physical units of a charitable good awaiting funding. Unit donation schemes have a popularity that extends beyond the food programs mentioned above. Development aid agencies, for example, promote child sponsorships by fixing the monthly donation for the sponsorship—usually around $35—and prospective donors choose the number of child-months to sponsor rather than the amount of money to donate. Similarly, fundraising drives for biodiversity conservation or reforestation programs let donors indicate the number of acres or trees to fund.Footnote 4 In unit donation schemes, the price of a unit of the charitable good G is no longer implicit. Instead, the fundraiser states an explicit price p and asks how many discrete units

![]() the potential donor would like to fund. In this respect, the setting resembles early models of the private provision of public goods that are explicit about units and prices (e.g., Warr Reference Warr1983). Under a unit donation scheme, therefore, the donor’s choice variable

the potential donor would like to fund. In this respect, the setting resembles early models of the private provision of public goods that are explicit about units and prices (e.g., Warr Reference Warr1983). Under a unit donation scheme, therefore, the donor’s choice variable

![]() is denominated in terms of the quantity of the charitable good funded.

is denominated in terms of the quantity of the charitable good funded.

Although donors eventually provide money under both schemes, there are important differences between unit and money donations. First, donors’ choice sets differ. Under a unit donation scheme, the units of the charitable good to be provided are typically indivisible, which introduces an element of discreteness that is largely absent in the virtually continuous money donations. Second, the information provided to prospective donors differs. By stating the per-unit price of the charitable good, unit donation schemes make statements about the charity’s marginal cost of production, whereas money donation schemes frequently provide little information on the cost structure of producing the charitable good. While information on the share of fundraising and overhead costs is increasingly available to donors (Ribar and Wilhelm Reference Ribar and Wilhelm2002; Meer Reference Meer2014), information on the impact of a contribution (or the absence thereof) can substantially affect donations (Bekkers and Wiepking Reference Bekkers and Wiepking2011; Lewis and Small Reference Lewis and Small2019). Third, the framing of the choice differs. By asking for the number of physical units of the charitable good, unit donation schemes emphasize how a donation generates specific outcomes for recipients. As a result, the motive of giving to create an impact (Duncan Reference Duncan2004) might become more relevant for the donation decision.

Diederich et al. (Reference Diederich, Epperson and Goeschl2021) compare the two donation schemes in an experimental study and show that the choice of the donation scheme significantly affects the likelihood of receiving donations. The direction of the effect depends on the size of a physical unit: A unit donation scheme attracts more donors than the equivalent money donation scheme if the unit size is small (daily nutritional rations at a price of $0.50) but fewer donors if the unit size is large (weekly rations at a price of $3.50). The difference at the large unit size is driven primarily by the restricted choice set under the unit donation scheme.

2.2 Subsidizing unit donations

Subsidizing unit donations involves some small but important differences compared to subsidizing money donations. In unit donations, rebates can be applied by refunding a fraction of the donor’s provision costs back to the donor. If, for example, a unit of the charitable good costs $0.50 and a 50% rebate is offered, the donor receives $0.25 back for each unit funded. Matches can be applied to unit donations by providing supplementary units of the charitable good. If, for example, a 1:1 match is offered for tree plantings, the third party funds one additional tree for each tree funded by the donor. Due to the indivisibility of units, matching payments by the third party are restricted to complete units of the charitable good. This introduces some discontinuity in the matching payment if the matching rate is not an integer: For example, at a matching rate of 0.5 (1:2) every second tree funded by the donor induces one tree funded by the third party. However, for a donation of only one tree, there is no additional funding by the third party. This is in contrast to the continuous choice in money donations, in which the matching rate typically applies to any arbitrary amount in the same way (i.e., at a matching rate of 0.5, a donation of any dollar amount induces a matching payment of 0.5 times this amount).

The transferability of results from money to unit donations is therefore not only a matter of framing effects: When matches consist of supplementary units and rebates are refunded costs, rebates and matches are also no longer theoretically equivalent. This is particularly evident at the extensive margin of becoming a donor: The smallest positive donation is to fund one unit of the charitable good. Given a unit price p, this implies a minimum expense of p required under matches. In contrast, rebates provide a refund on the donation given and, at subsidy rate r, the cost of becoming a donor is

![]() . As a result, rebates are potentially more effective in attracting donors. An additional difference comes into play when subsidy rates take non-integer values: The change in the matching payment due to a one unit increase in the donation depends on the donation level. In contrast, under rebates any increase in the donation proportionally increases the subsidy payment, as is the case for both subsidy types under money donations. In sum, there are not only structural differences between money and unit donations; there are also reasons to expect that subsidies perform differently under the two schemes.

. As a result, rebates are potentially more effective in attracting donors. An additional difference comes into play when subsidy rates take non-integer values: The change in the matching payment due to a one unit increase in the donation depends on the donation level. In contrast, under rebates any increase in the donation proportionally increases the subsidy payment, as is the case for both subsidy types under money donations. In sum, there are not only structural differences between money and unit donations; there are also reasons to expect that subsidies perform differently under the two schemes.

In a way, unit donation schemes resemble the shopping experience for private goods. For example, WorldVision provides a comprehensive gift catalog where donors can choose the number of units of various gifts that are associated with explicit prices.Footnote 5 In this regard, a matching subsidy is similar to bonus packs or “buy one get two” offers, whereas a rebate is comparable to coupons that provide an instant refund at checkout or cash-back programs (although the latter usually involve a time delay between the payment and the refund). However, with a well-defined good and an explicit price, there is a third option available, which is a direct price discount. Similar to stores that advertise price reductions, a charity can announce the discounted price of a gift and reveal that the gap to the original price is provided by a large donor or a governmental grant. Hence, if a unit of the charitable good costs $0.50 and a 50% discount is offered, the donor can fund one unit at a price of $0.25 while being informed that the remaining $0.25 are funded by an external party.

A discount at rate d is theoretically equivalent to a rebate at rate r when

![]() . However, two small differences exist that could cause different behavior.Footnote 6 First, rebate subsidies are paid to the donor whereas discount subsidies are paid to the charity. Second, in comparison to rebates (and matches), discounts obviate the need for donors to calculate the effective price of giving. In an online charity gift shop like the one by WorldVision, the rebate would take effect as an instant refund upon checkout whereas the discount is applied to the advertised prices during “shopping.” Furthermore, evidence for private goods shows that consumers may indeed respond different to rebates and direct price discounts (Davis and Millner Reference Davis and Millner2005), which makes it crucial to distinguish between both subsidy types in our research.

. However, two small differences exist that could cause different behavior.Footnote 6 First, rebate subsidies are paid to the donor whereas discount subsidies are paid to the charity. Second, in comparison to rebates (and matches), discounts obviate the need for donors to calculate the effective price of giving. In an online charity gift shop like the one by WorldVision, the rebate would take effect as an instant refund upon checkout whereas the discount is applied to the advertised prices during “shopping.” Furthermore, evidence for private goods shows that consumers may indeed respond different to rebates and direct price discounts (Davis and Millner Reference Davis and Millner2005), which makes it crucial to distinguish between both subsidy types in our research.

2.3 Related literature

We are not aware of any previous study that conducts a clean comparison between subsidy types under a pure unit donation scheme. At the same time, there are parallels with a number of papers studying charitable giving. Like our study, Meier (Reference Meier2007) and Gneezy et al. (Reference Gneezy, Keenan and Gneezy2014), for example, feature discrete choice sets. However, both frame donations in money, rather than physical quantities, and focus on matches only, yielding results that align with the wider money donation literature. A different parallel is with Lewis and Small (Reference Lewis and Small2019) who also provide subjects with information about the cost of a unit of impact and test different framings of the information. They find that a cheaper unit price leads to lower donations, an effect that is eliminated or reversed if the price is framed in units-per-dollar rather than dollars-per-unit. Yet, donations in their study are again framed in terms of money, rather than physical quantities, and the authors do not compare different subsidy types. Also relevant is a literature in marketing that experimentally compares product promotion strategies such as bonus packs (which are similar to matching subsidies) and price promotions (which are similar to our discount subsidy if they explicitly state the effective price). The papers in this literature provide mixed evidence (see, e.g., Sinha and Smith Reference Sinha and Smith2000; Mishra and Mishra Reference Mishra and Mishra2011; Chen et al. Reference Chen, Marmorstein, Tsiros and Rao2012), with bonus packs either being superior, equivalent, or inferior to price promotions. More in line with the money donations literature is Davis and Millner (Reference Davis and Millner2005), who find that matches outperform rebates also for private goods and that direct price discounts have an intermediate effect. While our focus on charitable giving sets our paper apart from this literature, its setting of unit donations offers the opportunity to study price discounts, a tool from private product promotion, in the context of charitable donations.

The paper probably closest to the focus of ours is Kesternich et al. (Reference Kesternich, Löschel and Römer2016). The authors compare the effectiveness of rebate and matching subsidies in the context of carbon offsetting: When buying their ticket(s) online, clients of a long distance bus operator decide whether to offset the carbon emissions from their travel at a given price per kilogram of emissions. Rebates are found to increase the likelihood of a decision to offset emissions while matches do so only to a lesser extent and only for certain matching rates. However, the overall contributions net of the subsidy are higher under matches. Key differences to our study are the binary decision format and the use of an impure public good for which the size of giving is tied to the private good. Both limit the comparability of our study and Kesternich et al. (Reference Kesternich, Löschel and Römer2016). A few other studies implicitly employ an experimental design soliciting unit donations to an environmental public good (Löschel et al. Reference Löschel, Sturm and Vogt2013; Diederich and Goeschl Reference Diederich and Goeschl2014, Reference Diederich and Goeschl2017, Reference Diederich and Goeschl2018), but they do not compare subsidy types.Footnote 7

3 Experimental design

3.1 Donation appeal

We adapt the real-donation dictator game introduced by Eckel and Grossman (Reference Eckel and Grossman1996) and subsequently applied to compare subsidy types (Eckel and Grossman Reference Eckel and Grossman2003; Davis and Millner Reference Davis and Millner2005; Davis Reference Davis2006; Eckel and Grossman Reference Eckel, Grossman, Davis and Isaac2006a, Reference Eckel and Grossmanb). In the standard version of the game, subjects decide how much of a money endowment to hold and how much to pass to a charity. In our variant of the game, subjects decide how many units of the charitable good to fund at a given nominal price.

Our variant of the game requires a charitable good or service that is easily quantifiable. We approached a relief organization, Sign of Hope e.V., which frequently uses various forms of unit donation schemes in their fundraising campaigns. Among their activities, we chose the treatment of malnourished children in a certain area of South Sudan as this service offered practical units and prices for our experiment. At the time of the experiment, children were treated in two “bush clinics” operated by the relief organization. Treating one child for one month using a special nutritional paste and high energy cookies required a donation of US$15. We divided this number into practical units of nutritional packages per child and day, which implied a “price” of $0.50 per package.

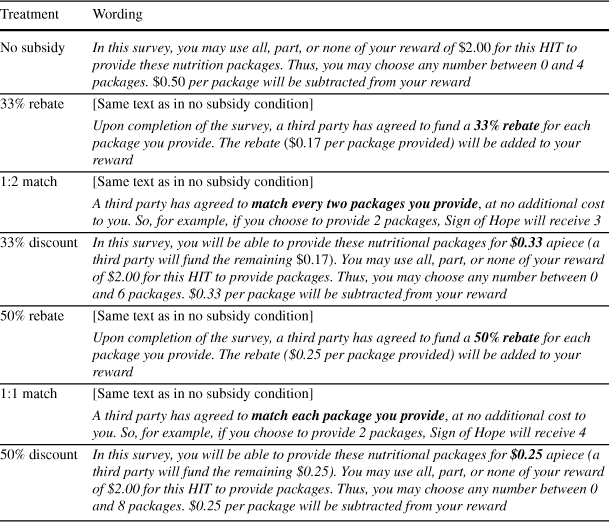

The donation appeal was part of an online survey and participants used their reward for completing the survey ($2) to make any donations. The donation appeal introduced the charity, the charitable good, and the marginal cost of providing the charitable good. We also provided a link to the charity’s web page and informed subjects about a transparency award the charity had won to increase trust in the charity (Adena et al. Reference Adena, Alizade, Bohner, Harke and Mesters2019). The final part of the donation appeal was treatment specific. Table 1 shows the seven treatment conditions. In the control condition, no subsidy was applied and subjects chose how many packages to fund at a price of $0.50. The remaining six treatment conditions follow a

![]() factorial design with one factor being the subsidy type (rebate, match, or discount) and the other factor being the effective price ($0.33 or $0.25) implied by the subsidy level. In the instructions, we framed the rebate conditions as 33% (50%) rebate and stated that while providing packages would cost the subject $0.50 apiece, a rebate of $0.17 ($0.25) per package would be added to the subject’s final reward at the end of the experiment. For the matching conditions, instructions stated that for every two packages (each package) that the subject provided at a nominal cost of $0.50 apiece, one package would be matched at no additional cost to the subject. As a result, the charity would receive the combined number of packages. For the discount conditions, instructions stated that the subject would be able to provide packages for $0.33 ($0.25) instead of $0.50 apiece. Hence, the nominal price corresponded to the effective price. For all subsidy types, instructions noted that the subsidy, i.e., the rebate, the matched units, or the money needed to reduce the nominal price, was provided by “a third party.” This was a truthful yet indefinite reference to the research budget involved. Subjects chose the desired number of packages from a drop-down menu. The exact wording of each treatment can be found in Table 2.Footnote 8

factorial design with one factor being the subsidy type (rebate, match, or discount) and the other factor being the effective price ($0.33 or $0.25) implied by the subsidy level. In the instructions, we framed the rebate conditions as 33% (50%) rebate and stated that while providing packages would cost the subject $0.50 apiece, a rebate of $0.17 ($0.25) per package would be added to the subject’s final reward at the end of the experiment. For the matching conditions, instructions stated that for every two packages (each package) that the subject provided at a nominal cost of $0.50 apiece, one package would be matched at no additional cost to the subject. As a result, the charity would receive the combined number of packages. For the discount conditions, instructions stated that the subject would be able to provide packages for $0.33 ($0.25) instead of $0.50 apiece. Hence, the nominal price corresponded to the effective price. For all subsidy types, instructions noted that the subsidy, i.e., the rebate, the matched units, or the money needed to reduce the nominal price, was provided by “a third party.” This was a truthful yet indefinite reference to the research budget involved. Subjects chose the desired number of packages from a drop-down menu. The exact wording of each treatment can be found in Table 2.Footnote 8

Table 1 Treatment conditions

|

Subsidy type |

Subsidy |

Nominal |

Effective |

N |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

rate |

unit price |

unit price |

||

|

No subsidy |

– |

$0.50 |

$0.50 |

83 |

|

Rebate |

33% |

$0.50 |

$0.33 |

71 |

|

Match |

1:2 |

$0.50 |

$0.33 |

85 |

|

Discount |

33% |

$0.33 |

$0.33 |

90 |

|

Rebate |

50% |

$0.50 |

$0.25 |

58 |

|

Match |

1:1 |

$0.50 |

$0.25 |

80 |

|

Discount |

50% |

$0.25 |

$0.25 |

91 |

Table 2 Final part of donation appeal wording by treatment

|

Treatment |

Wording |

|---|---|

|

No subsidy |

In this survey, you may use all, part, or none of your reward of $2.00 for this HIT to provide these nutrition packages. Thus, you may choose any number between 0 and 4 packages. $0.50 per package will be subtracted from your reward |

|

33% rebate |

[Same text as in no subsidy condition] |

|

Upon completion of the survey, a third party has agreed to fund a 33% rebate for each package you provide. The rebate ($0.17 per package provided) will be added to your reward |

|

|

1:2 match |

[Same text as in no subsidy condition] |

|

A third party has agreed to match every two packages you provide , at no additional cost to you. So, for example, if you choose to provide 2 packages, Sign of Hope will receive 3 |

|

|

33% discount |

In this survey, you will be able to provide these nutritional packages for $0.33 apiece (a third party will fund the remaining $0.17). You may use all, part, or none of your reward of $2.00 for this HIT to provide packages. Thus, you may choose any number between 0 and 6 packages. $0.33 per package will be subtracted from your reward |

|

50% rebate |

[Same text as in no subsidy condition] |

|

Upon completion of the survey, a third party has agreed to fund a 50% rebate for each package you provide. The rebate ($0.25 per package provided) will be added to your reward |

|

|

1:1 match |

[Same text as in no subsidy condition] |

|

A third party has agreed to match each package you provide , at no additional cost to you. So, for example, if you choose to provide 2 packages, Sign of Hope will receive 4 |

|

|

50% discount |

In this survey, you will be able to provide these nutritional packages for $0.25 apiece (a third party will fund the remaining $0.25). You may use all, part, or none of your reward of $2.00 for this HIT to provide packages. Thus, you may choose any number between 0 and 8 packages. $0.25 per package will be subtracted from your reward |

A Human Intelligence Task (HIT) is how Amazon Mechanical Turk calls a “self-contained, virtual task that a Worker can work on, submit an answer, and collect a reward for completing” (Retrieved July 23, 2021, from https://www.mturk.com/worker/help)

3.2 Experimental protocol

We conducted the experiment online recruiting U.S. residents from the online labor market Amazon Mechanical Turk (AMT).Footnote 9 In the case of money donations, online field experiments based on AMT (Gandullia and Lezzi Reference Gandullia and Lezzi2018; Gandullia Reference Gandullia2019) and not based on AMT (Bekkers Reference Bekkers, Deck, Fatas, Rosenblat, Isaac and Norton2015) have been successfully used to replicate the superiority of matches over rebates. Gandullia and Lezzi (Reference Gandullia and Lezzi2018) and Gandullia (Reference Gandullia2019) use the same endowment level and subsidy rates as we do. Our task was posted five times on the AMT task queue between July and October 2015, resulting in five online sessions. Interested workers were informed that they would earn $2 for answering a 20-minute academic survey on several topics. The payment is rather high when compared to the average hourly wage of about

![]() to

to

![]() per worker on AMT (Hara et al. Reference Hara, Adams, Milland, Savage, Callison-Burch and Bigham2018). Each worker was able to participate only once. Donations were mentioned as one of the topics, but the real-donation dictator game was not particularly salient compared to other survey elements. As a result, it is unlikely that subjects considered the donation task as the main subject of investigation. Interested workers followed a link which directed them to the survey containing the experiment on Qualtrics. Having followed the link to the survey platform, interested workers read and confirmed an informed consent page about the research study.

per worker on AMT (Hara et al. Reference Hara, Adams, Milland, Savage, Callison-Burch and Bigham2018). Each worker was able to participate only once. Donations were mentioned as one of the topics, but the real-donation dictator game was not particularly salient compared to other survey elements. As a result, it is unlikely that subjects considered the donation task as the main subject of investigation. Interested workers followed a link which directed them to the survey containing the experiment on Qualtrics. Having followed the link to the survey platform, interested workers read and confirmed an informed consent page about the research study.

The experimental survey consisted of four parts: (1) the donation appeal, (2) a questionnaire on various topics, (3) a low-stake version of the Eckel-Grossman Risk Task (Eckel and Grossman Reference Eckel and Grossman2002, Reference Eckel and Grossman2008a),Footnote 10 and (4) a 5-item manipulation check questionnaire comparable to Eckel and Grossman (Reference Eckel and Grossman2003, Reference Eckel and Grossman2006b) and Davis and Millner (Reference Davis and Millner2005). Parts (1) and (2) were presented in random order. Hence, a subject encountered the donation appeal either before or after the questionnaire. One of the treatment conditions was drawn at random and presented to the subject (between-subjects design).Footnote 11 The questionnaire of part (2) consisted of questions on sociodemographics, employment, and religious beliefs, as well as current ambient environmental conditions and the Ten Item Personality Inventory (TIPI), which is a standard one-minute version of more extensive multi-item instruments to assess the Big Five personality dimensions (Gosling et al. Reference Gosling, Rentfrow and Swann2003; Ehrhart et al. Reference Ehrhart, Ehrhart, Roesch, Chung-Herrera, Nadler and Bradshaw2009). After completion of all survey parts, a unique code was shown that the subject had to enter into the survey task window on AMT to receive payment.

In total, we have 613 observations of participants starting the survey and 599 completed records. Incomplete records were dropped from the analysis.Footnote 12 The obvious concern that some subjects may fraudulently use multiple accounts to participate more than once is generally seen as a minor problem in online experiments (Horton et al. Reference Horton, Rand and Zeckhauser2011; Paolacci et al. Reference Paolacci, Chandler and Ipeirotis2010).Footnote 13 We nevertheless follow the common approach to exclude 40 subjects with duplicate Internet Protocol addresses from the analysis (Reips Reference Reips and Birnbaum2000; Birnbaum Reference Birnbaum2004). Including them does not change the results. We also dropped one subject who indicated an age below 18 in the questionnaire, despite having confirmed an age above 18 when agreeing to the informed consent statement. This leaves us with a sample of 558 subjects (see Table 1 for the allocation of subjects across treatments). Average payouts were $1.80 (net of donations and including an average of $0.33 additional payment for the risk task). Subjects took on average 8.26 minutes to complete the experiment.

4 Results

Variables elicited in the questionnaire suggest a diverse sample of subjects (see Table B2 in Online Appendix B): Slightly less than half of subjects are female, and slightly less than half graduated from college. About one-third of subjects are married, and about the same share has children under age 16 living in the household. Both age and income are well spread, with the median age in category 26–34 and the median yearly income in category US$40,000–49,999. Separate F-tests suggest that the characteristics are well-balanced across our treatment groups. Only one out of 35 comparisons is significant at the five percent level, and only three additional ones with p-values of 0.08, 0.10, and 0.11 could be seen as borderline significant.

Answers to the manipulation check questions indicate that on average, subjects clearly understood instructions and procedures, felt that their anonymity was preserved, trusted the experimenters and the charity, and found the recipients of the donations worth supporting (Table B2 in Online Appendix B). With the exception of the last item, the answers to the manipulation check questions do not significantly differ across treatments.

Table 3 presents descriptive results of donation decisions observed in the experimental treatments. Panel A reports mean values and standard deviations. Column 1 shows the average number of nutritional packages that subjects chose to donate in their version of the donation appeal. Hence, column 1 represents the units purchased before any rebate or matching subsidy while accounting for subsidized nominal prices in the discount conditions. If multiplied by the nominal price, column 1 would correspond to out-of-pocket expenses that are frequently denoted as “checkbook giving” in standard money donation experiments. Column 2 reports individual net donations in dollars after accounting for all subsidies. That is, column 2 is column 1 evaluated at the (discounted) nominal price minus any rebates. Column 3 lists the mean number of nutritional packages the charity “receives,” based on subjects’ choices, that is, column 1 plus any matched packages. If we multiplied column 3 by $0.50 for all treatments, we would obtain gross charity receipts in dollars, a common focus in money donation experiments. Because of perfect collinearity of both receipts measures, we only use charity receipts expressed in units in the following analysis, with the exception of Fig. 1 where we use charity receipts expressed in dollars to illustrate its composition. Columns 4 and 5 show the intensive and the extensive margin of giving, respectively. Column 4 reports mean charity receipts conditional on being a donor while column 5 reports the fraction of donors. For each variable, panels B to D report p-values of pairwise comparison tests between treatments.

The remainder of this section presents the results of our analysis. We first focus on rebates and matches (Sect. 4.1) and subsequently turn to the effectiveness of discount subsidies (Sect. 4.2). We discuss potential explanations for our results in Sect. 5.

Table 3 Descriptive results

|

Treatments |

Donation variable |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Condition |

Nominal unit price ($) |

Effective unit price ($) |

Indivi- dual choice (units) |

Net dona- tion ($) |

Charity receipt, uncond. (units) |

Charity receipt, cond. (units) |

Prob. of dona- tion |

|

|

(1) |

(2) |

(3) |

(4) |

(5) |

||||

|

A. Mean values (S.D.) |

||||||||

|

No subsidy |

0.50 |

0.50 |

1.169 |

0.584 |

1.169 |

2.256 |

0.518 |

|

|

(1.413) |

(0.706) |

(1.413) |

(1.177) |

(0.503) |

||||

|

33% rebate |

0.50 |

0.33 |

1.690 |

0.558 |

1.690 |

2.400 |

0.704 |

|

|

(1.545) |

(0.510) |

(1.545) |

(1.294) |

(0.460) |

||||

|

1:2 match |

0.50 |

0.33 |

1.059 |

0.529 |

1.506 |

3.048 |

0.494 |

|

|

(1.339) |

(0.670) |

(2.021) |

(1.886) |

(0.503) |

||||

|

33% discount |

0.33 |

0.33 |

1.478 |

0.488 |

1.478 |

2.771 |

0.533 |

|

|

(1.973) |

(0.651) |

(1.973) |

1.927 |

(0.502) |

||||

|

50% rebate |

0.50 |

0.25 |

1.931 |

0.483 |

1.931 |

2.732 |

0.707 |

|

|

(1.705) |

(0.426) |

(1.705) |

(1.379) |

(0.459) |

||||

|

1:1 match |

0.50 |

0.25 |

1.113 |

0.556 |

2.225 |

3.787 |

0.588 |

|

|

(1.253) |

(0.626) |

(2.506) |

(2.176) |

(0.495) |

||||

|

50% discount |

0.25 |

0.25 |

2.143 |

0.536 |

2.143 |

3.545 |

0.604 |

|

|

(2.831) |

(0.708) |

(2.831) |

(2.879) |

(0.492) |

||||

|

B. Tests of subsidy types: p-values |

||||||||

|

B1. At effective price of $0.33 |

||||||||

|

33% rebate vs. 1:2 match |

0.01 |

0.76 |

0.52 |

0.06 |

0.01 |

|||

|

33% rebate vs. 33% discount |

0.44 |

0.44 |

0.44 |

0.27 |

0.03 |

|||

|

1:2 match vs. 33% discount |

0.10 |

0.68 |

0.93 |

0.49 |

0.60 |

|||

|

B2. At effective price of $0.25 |

||||||||

|

50% rebate vs. 1:1 match |

0.00 |

0.41 |

0.41 |

0.01 |

0.15 |

|||

|

50% rebate vs. 50% discount |

0.57 |

0.57 |

0.57 |

0.07 |

0.20 |

|||

|

1:1 match vs. 50% discount |

0.00 |

0.84 |

0.84 |

0.63 |

0.82 |

|||

|

C. Tests of subsidized prices: p-values |

||||||||

|

50% vs. 33% rebate |

0.41 |

0.36 |

0.41 |

0.24 |

0.97 |

|||

|

1:1 vs. 1:2 match |

0.79 |

0.79 |

0.05 |

0.09 |

0.23 |

|||

|

50% vs. 33% discount |

0.07 |

0.64 |

0.07 |

0.11 |

0.34 |

|||

|

D. Tests of subsidized vs. unsubsidized prices: p-values |

||||||||

|

D1. Low subsidy rate |

||||||||

|

33% rebate vs. no subsidy |

0.03 |

0.79 |

0.03 |

0.58 |

0.02 |

|||

|

1:2 match vs. no subsidy |

0.61 |

0.61 |

0.21 |

0.02 |

0.76 |

|||

|

33% discount vs. no subsidy |

0.24 |

0.35 |

0.24 |

0.12 |

0.84 |

|||

|

D2. High subsidy rate |

||||||||

|

50% rebate vs. no subsidy |

0.01 |

0.29 |

0.01 |

0.09 |

0.03 |

|||

|

1:1 match vs. no subsidy |

0.79 |

0.79 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.37 |

|||

|

50% discount vs. no subsidy |

0.00 |

0.65 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.25 |

|||

Panel A shows mean values of the donation variables for each treatment (standard deviations in parentheses). Column 1 reports the number of packages that subjects selected to give at the nominal price. Column 2 shows the net dollar contribution implied by subjects’ choices, i.e., column 1 evaluated at the nominal price minus the rebate (if any). Column 3 reports the overall number of packages received by the charity, i.e., column 1 plus matched units (if any). Column 4 reports the same measure as column 3 but conditional on giving (intensive margin). Column 5 reports the share of subjects who donated at least one package (extensive margin). Panels B to D show pairwise tests between treatment conditions. Panel B compares subsidy types conditional on the effective price. Panel C compares the two subsidized prices, $0.25 and $0.33, conditional on subsidy type. Panel D compares the unsubsidized price with the subsidized price arising from the low subsidy rate for each subsidy type. Columns 1 to 4 in panels B to D report p-values of two-tailed t-tests with unequal variances. Column 5 report p-values of Pearson

![]() tests for binary data

tests for binary data

4.1 Rebates versus matches

Three main results follow from columns 1 to 3 of Table 3. First, column 3 in panel A shows that the charity received about 1.7 units per subject in the 33% rebate condition and about 1.5 units per subject in the comparable 1:2 matching condition. When the higher subsidy rate was used, the charity received 1.9 units per subject in the 50% rebate condition and 2.2 units in the 1:1 match condition. At both effective prices, the levels of charity receipts do not significantly differ between the two subsidy types (

![]() and

and

![]() , panels B1 and B2).

, panels B1 and B2).

Result 1

(Charity receipts) Charity receipts do not significantly differ between rebate and matching subsidies.

Second, column 3 also shows that charity receipts significantly increase in the subsidy level, either from introducing a subsidy (

![]() for a 33% rebate, 50% rebate, and 1:1 match, panel D) or from increasing the subsidy rate (

for a 33% rebate, 50% rebate, and 1:1 match, panel D) or from increasing the subsidy rate (

![]() in case of the match, panel C).

in case of the match, panel C).

Result 2

(Law of demand) Charity receipts significantly decrease in the price.

Third, column 2 in panel A indicates that net donations exhibit a roughly constant share of around one quarter of the endowment across all treatment conditions. Thus, neither the introduction of a subsidy at any rate nor an increase in the subsidy rate results in significant changes of subjects’ own contributions net of the subsidy (

![]() for pairwise comparisons, panels C and D). Note that in order to achieve the same level of charity receipts and own net donations, subjects need to select more units to donate under a rebate than under a match (since the match is paid on top of the units selected). This is exactly what we observe in column 1: The average number of units selected is at least 0.5 units larger in panel A (

for pairwise comparisons, panels C and D). Note that in order to achieve the same level of charity receipts and own net donations, subjects need to select more units to donate under a rebate than under a match (since the match is paid on top of the units selected). This is exactly what we observe in column 1: The average number of units selected is at least 0.5 units larger in panel A (

![]() at both effective prices, panel B).

at both effective prices, panel B).

Result 3

(Net donations) There is no evidence for crowding-in or crowding-out of net donations by rebate or matching subsidies of any level.

Result Footnote 3 has an important implication: It implies that the increase in charity receipts (Result Footnote 2) is entirely driven by the additional money provided as subsidy payment by the third party, instead of being driven by individuals actually giving more (see Fig. 1 for an illustration). This finding does not generally hold in the money donation literature. Several papers find that matches significantly increase net donations compared to a no subsidy condition without lead donor (Eckel et al. Reference Eckel, Grossman and Milano2007; Karlan and List Reference Karlan and List2007; Gneezy et al. Reference Gneezy, Keenan and Gneezy2014; Huck et al. Reference Huck, Rasul and Shephard2015; Eckel and Grossman Reference Eckel and Grossman2017). However, there are also some papers that do not find a significant effect on net donations (Lukas et al. Reference Lukas, Grossman and Eckel2010; Karlan et al. Reference Karlan, List and Shafir2011; McCarty et al. Reference McCarty, Diette and Holloway2018). Evidence for rebates is scarcer and rather points in the opposite direction, i.e., that rebates crowd out net donations (Eckel and Grossman Reference Eckel and Grossman2003, Reference Eckel and Grossman2008b; Gandullia and Lezzi Reference Gandullia and Lezzi2018; Gandullia Reference Gandullia2019).

Fig. 1 Average charity receipts in dollars (divided into average net donations and corresponding subsidy payments) by treatment. This corresponds to charity receipts in units (column 3 of Table 3) multiplied by the (unsubsidized) unit price of $0.50

The most substantial difference between our findings and those that are predominant in the money donation literature is the equality of rebates and matches regarding charity receipts (Result Footnote 1). The well-established finding in the context of money donations is that charity receipts under matches exceed those under rebates (Eckel and Grossman Reference Eckel and Grossman2003, Reference Eckel, Grossman, Davis and Isaac2006a, Reference Eckel and Grossmanb, Reference Eckel and Grossman2008b, Reference Eckel and Grossman2017; Davis et al. Reference Davis, Millner and Reilly2005; Lukas et al. Reference Lukas, Grossman and Eckel2010; Bekkers Reference Bekkers, Deck, Fatas, Rosenblat, Isaac and Norton2015; Gandullia and Lezzi Reference Gandullia and Lezzi2018; Gandullia Reference Gandullia2019), while “checkbook giving,” which corresponds to column 1 in panel A of Table 3 multiplied by the nominal price, is often roughly the same under both subsidy types. We therefore now examine whether our results are robust to controlling for available covariates. For this purpose, we estimate an Ordered Probit Model with the individual choice as dependent variable and use it to analyze the effect of the different subsidies on the level of charity receipts. Online Appendix A presents details of the model.Footnote 14

Columns 1 and 2 in panel A of Table 4 present the results in the form of the average marginal effects on charity receipts without and with controlling for covariates. For example, offering a 33% rebate is estimated to increase average charity receipts per individual by about 0.5 packages compared to not offering any subsidy (column 1, Rebate), whereas increasing the subsidy rate from 33% to 50% has no significant effect in the case of the rebate (column 1, Rebate

![]() low price). Analogously to Table 3, the predicted levels of charity receipts are compared pairwise across subsidy types in panel B, holding the effective price constant. The estimates confirm Result Footnote 1 and Result Footnote 2. We repeat the same exercise for predicted levels of net donations. In line with Result Footnote 3, we neither find significant differences in net donations between subsidy types at the same effective price nor any evidence for crowding-in or crowding-out at any conventional significance level when changing the price of giving due to a specific subsidy type.Footnote 15

low price). Analogously to Table 3, the predicted levels of charity receipts are compared pairwise across subsidy types in panel B, holding the effective price constant. The estimates confirm Result Footnote 1 and Result Footnote 2. We repeat the same exercise for predicted levels of net donations. In line with Result Footnote 3, we neither find significant differences in net donations between subsidy types at the same effective price nor any evidence for crowding-in or crowding-out at any conventional significance level when changing the price of giving due to a specific subsidy type.Footnote 15

Table 4 Estimation results

|

Charity receipts, unconditional (units) |

Probability of donation (binary) |

Charity receipts, conditional (units) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

(1) |

(2) |

(3) |

(4) |

(5) |

(6) |

|

|

A. Marginal effects |

||||||

|

Rebate |

0.546** |

0.533** |

0.186** |

0.220*** |

0.091 |

−0.039 |

|

(0.237) |

(0.257) |

(0.077) |

(0.081) |

(0.256) |

(0.27) |

|

|

Match |

0.324 |

0.248 |

−0.024 |

−0.011 |

0.799** |

0.488 |

|

(0.261) |

(0.291) |

(0.077) |

(0.086) |

(0.359) |

(0.392) |

|

|

Discount |

0.306 |

0.231 |

0.015 |

0.012 |

0.537 |

0.316 |

|

(0.247) |

(0.272) |

(0.076) |

(0.084) |

(0.332) |

(0.357) |

|

|

Rebate

|

0.218 |

0.218 |

0.003 |

−0.018 |

0.326 |

0.342 |

|

(0.277) |

(0.302) |

(0.081) |

(0.088) |

(0.266) |

(0.279) |

|

|

Match

|

0.888** |

0.992** |

0.093 |

0.104 |

0.783* |

0.782* |

|

(0.373) |

(0.405) |

(0.077) |

(0.084) |

(0.448) |

(0.466) |

|

|

Discount

|

0.585* |

0.613* |

0.071 |

0.057 |

0.571 |

0.807 |

|

(0.326) |

(0.366) |

(0.073) |

(0.084) |

(0.448) |

(0.503) |

|

|

B. Tests of subsidy types: p-values |

||||||

|

B1. At effective price of $0.33 |

||||||

|

33% rebate vs. 1:2 match |

0.43 |

0.35 |

0.01 |

0.00 |

0.05 |

0.17 |

|

33% rebate vs. 33% discount |

0.37 |

0.30 |

0.02 |

0.01 |

0.17 |

0.31 |

|

1:2 match vs. 33% discount |

0.95 |

0.96 |

0.60 |

0.79 |

0.53 |

0.69 |

|

B2. At effective price of $0.25 |

||||||

|

50% rebate vs. 1:1 match |

0.23 |

0.22 |

0.14 |

0.21 |

0.00 |

0.01 |

|

50% rebate vs. 50% discount |

0.71 |

0.81 |

0.19 |

0.13 |

0.09 |

0.08 |

|

1:1 match vs. 50% discount |

0.43 |

0.37 |

0.82 |

0.77 |

0.33 |

0.78 |

|

Covariates

|

No |

Yes |

No |

Yes |

No |

Yes |

|

Log likelihood |

−801.28 |

−592.51 |

−372.07 |

−250.92 |

−427.37 |

−314.94 |

|

Observations |

558 |

428 |

558 |

428 |

326 |

256 |

(1)–(2): Ordered Probit with the number of packages selected by the individual as dependent variable. (3)–(4): Probit for whether or not a donation was made. (5)–(6): Ordered Probit conditional on being a donor, with the number of packages selected by the individual as dependent variable. (1)–(2) and (5)–(6) treat a single observation with 5 selected packages as if it were 6 selected packages

Panel A presents average marginal effects. Standard errors reported in parentheses, *

![]() , **

, **

![]() , ***

, ***

![]() . For (1)–(2) and (5)–(6), marginal effects refer to the average change in expected charity receipts over all individuals or donors only, respectively. For each individual considered, the change is calculated by taking the difference in expected charity receipts between receiving a particular subsidy at the low rate (rebate, match, discount) and not receiving any subsidy or between receiving a particular subsidy at the high rate (rebate

. For (1)–(2) and (5)–(6), marginal effects refer to the average change in expected charity receipts over all individuals or donors only, respectively. For each individual considered, the change is calculated by taking the difference in expected charity receipts between receiving a particular subsidy at the low rate (rebate, match, discount) and not receiving any subsidy or between receiving a particular subsidy at the high rate (rebate

![]() low price, match

low price, match

![]() low price, discount

low price, discount

![]() low price) and receiving the same subsidy at the low rate

low price) and receiving the same subsidy at the low rate

Panel B presents p-values for the pairwise comparison of treatment effects (subsidy treatment vs. no subsidy) between subsidy types, based on the average marginal effects

![]() Covariates include gender, marital status, the Big Five personality dimensions, risk preferences, categorical variables for age, income, residential environment, and religion, and dummies for whether the individual holds a college degree, whether children under the age of 16 live in the household, whether the individual is a registered voter, whether the individual frequently attends religious services, whether the individual works for a not-for-profit organization and task order. Likelihood ratio tests reject that their coefficients in model (2), (4) and (6) are jointly zero (

Covariates include gender, marital status, the Big Five personality dimensions, risk preferences, categorical variables for age, income, residential environment, and religion, and dummies for whether the individual holds a college degree, whether children under the age of 16 live in the household, whether the individual is a registered voter, whether the individual frequently attends religious services, whether the individual works for a not-for-profit organization and task order. Likelihood ratio tests reject that their coefficients in model (2), (4) and (6) are jointly zero (

![]() ,

,

![]() and

and

![]() , respectively)

, respectively)

Having observed that charity receipts do not differ between rebates and matches, we ask whether this result masks heterogeneities in the “conversion rates” of the experimental donation call (the extensive margin of giving) and the conditional level of charity receipts demanded by donors (the intensive margin of giving). As discussed in Sect. 1, rebates decrease the minimum net expense required to become a donor, making them potentially more effective at the extensive margin than matches. Indeed, switching back to the descriptive results shown in Table 3 confirms that rebates attract a larger share of donors than matches. In particular, column 5 in panel A reveals that the difference amounts to roughly 21 percentage points (70.4% vs. 49.4%) in the case of the high effective price and to about 12 percentage points (70.7% vs. 58.8%) in the case of the low effective price. Pairwise tests show that the difference is significant at the high effective price (

![]() , panel B1) but not at the low effective price (

, panel B1) but not at the low effective price (

![]() , panel B2).Footnote 16 We take this as evidence that the equality result for the level of charity receipts is partly driven by the fact that rebate subsidies are more effective at the extensive margin.

, panel B2).Footnote 16 We take this as evidence that the equality result for the level of charity receipts is partly driven by the fact that rebate subsidies are more effective at the extensive margin.

Result 4

(Extensive margin) Rebates are more effective in attracting donors than matches.

Turning to the intensive margin, column 4 of Table 3 shows that conditional charity receipts under both match conditions significantly exceed the corresponding values in the rebate conditions (3.0 vs. 2.4 units and 3.8 vs. 2.7 units, panel A;

![]() and

and

![]() , panels B1 and B2).

, panels B1 and B2).

Result 5

(Intensive margin) Charity receipts per donor are higher under matching than under rebate subsidies.

Comparing matching and rebate treatments to the control treatment reinforces the view that the channel through which rebates raise unconditional charity receipts primarily is the extensive margin whereas matches unfold their impact through the intensive margin. For the rebate, introducing the low subsidy rate increases the share of donors in column 5 in panel A from 51.8% to 70.4% (

![]() , panel D1) compared to the no subsidy condition, while the intensive margin in column 4 is not significantly affected (

, panel D1) compared to the no subsidy condition, while the intensive margin in column 4 is not significantly affected (

![]() , panel D1). In contrast, for the match, introducing the low subsidy rate increases mean conditional charity receipts in column 4, panel A from 2.3 to 3.0 units (

, panel D1). In contrast, for the match, introducing the low subsidy rate increases mean conditional charity receipts in column 4, panel A from 2.3 to 3.0 units (

![]() , panel D1) compared to the no subsidy condition, while the extensive margin in column 5 is unaffected (

, panel D1) compared to the no subsidy condition, while the extensive margin in column 5 is unaffected (

![]() , panel D1).

, panel D1).

Again, we supplement the descriptive results by estimating appropriate parametric models. Columns 3 and 4 of Table 4 refer to a Probit without and with covariates, respectively, while columns 5 and 6 capture the intensive margin by estimating an Ordered Probit Model for donors only. The latter is set up analogously to the Ordered Probit Model used above.Footnote 17 The parametric estimation in Table 4 confirms results Footnote 4 and Footnote 5, with the exception that the difference between the 33% rebate and the 1:2 match at the intensive margin becomes insignificant when covariates are included (column 6, panel B).

One concern regarding the comparison of rebate and matching subsidies in our experiment might be that differences in the budget constraints for charity receipts could drive some of the results. Under a rebate, the highest possible number of packages received by the charity is always four, since the donor must fully fund each selected unit at a nominal price of $0.5 before receiving the refund. In contrast, the matching subsidy applies on top of the selected packages: If under a 1:1 match a donor decides to spend her whole endowment of $2 to fund four packages, then the charity receives eight packages.Footnote 18 Similar differences apply to almost all laboratory experiments comparing rebates and matches in the money donation literature, as they also endow subjects with a limited amount of money. In the money donation literature, it is shown that the higher effectiveness of matches observed in laboratory studies also holds in field experiments where subjects use their own income (Eckel and Grossman Reference Eckel and Grossman2008b, Reference Eckel and Grossman2017). If the budget constraint mattered in our design, the results could understate the effectiveness of rebates compared to matches for situations in which the budget constraint is looser or non-binding. This implies that rebates might be even more effective than matches in such situations.

To provide a robustness check on this matter, we revisit Result Footnote 1 and Result Footnote 5 by recoding subjects’ choices in order to equalize budget constraints. In our data, a total of 29.5% of subjects give the maximum amount under rebates, compared to 10.9% in the matching conditions. For each condition, we set all charity receipts above four packages to four packages (the maximum level of charity receipts under rebates). Detailed results are presented in Table B4 in Online Appendix B. Although rebates now provide the highest average number of packages received by the charity, the difference to matches is not significant at the high subsidy rate (

![]() ) and only marginally significant at the low subsidy rate (

) and only marginally significant at the low subsidy rate (

![]() ). Hence, Result Footnote 1 survives the robustness check. In contrast, the difference on the intensive margin (Result Footnote 5) vanishes after censoring charity receipts at four packages. A possible explanation is that matches create larger conditional donations only in settings where the budget constraint is binding for a sufficiently large share of individuals.

). Hence, Result Footnote 1 survives the robustness check. In contrast, the difference on the intensive margin (Result Footnote 5) vanishes after censoring charity receipts at four packages. A possible explanation is that matches create larger conditional donations only in settings where the budget constraint is binding for a sufficiently large share of individuals.

4.2 Discount subsidies

Subsidies that consist of a simple nominal price reduction turn out to be as effective as rebate and matching subsidies that produce equivalent effective prices. Charity receipts in column 3 and net donations in column 2 of Table 3 do not significantly differ from those under the other two subsidy types (

![]() for each pairwise comparison in panel B). Hence, the increased salience of the effective price under discounts does not seem to affect demand, and this alternative subsidy type does not lend itself to a more effective subsidy. Instead, the selected number of units (column 1, panel A) under a discount is statistically indistinguishable from that selected under a rebate (

for each pairwise comparison in panel B). Hence, the increased salience of the effective price under discounts does not seem to affect demand, and this alternative subsidy type does not lend itself to a more effective subsidy. Instead, the selected number of units (column 1, panel A) under a discount is statistically indistinguishable from that selected under a rebate (

![]() and

and

![]() , panels B1 and B2) but by an amount higher than under the corresponding match (

, panels B1 and B2) but by an amount higher than under the corresponding match (

![]() and

and

![]() , panels B1 and B2), which approximately makes up for the additional units provided as matching payment. In line with the law of demand, charity receipts in column 3 increase in the subsidy level by applying the 50% discount instead of the no subsidy condition (

, panels B1 and B2), which approximately makes up for the additional units provided as matching payment. In line with the law of demand, charity receipts in column 3 increase in the subsidy level by applying the 50% discount instead of the no subsidy condition (

![]() , panel D2) or instead of the 33% discount (

, panel D2) or instead of the 33% discount (

![]() , panel C). There is again no evidence for crowding-in or -out. Our Ordered Probit estimates in Table 4, columns 1–2, confirm these findings.

, panel C). There is again no evidence for crowding-in or -out. Our Ordered Probit estimates in Table 4, columns 1–2, confirm these findings.

Result 6

(Discounts) The discount subsidy produces the same level of charity receipts and net donations as rebates and matches. Increasing the subsidy rate increases charity receipts, without crowding-in or crowding-out net donations.

As in the previous section, we can differentiate the behavior into the extensive and the intensive margin. At the low subsidy rate, the likelihood of giving under the discount is significantly lower than under the rebate (

![]() , column 5 in panel B1 of Table 3 and columns 3 and 4 in panel B1 of Table 4). Since we would expect the responses to rebates and discounts to be similar at the extensive margin, this difference may hint towards a behavioral bias in the response to an equivalent decrease in the cost of becoming a donor. At the intensive margin, there is only some marginally significant difference between discounts and rebates at the high subsidy rate, shown in column 4 of Table 3 and columns 5–6 of Table 4. In comparison to the matching subsidies, significant differences arise at neither the extensive nor the intensive margin.

, column 5 in panel B1 of Table 3 and columns 3 and 4 in panel B1 of Table 4). Since we would expect the responses to rebates and discounts to be similar at the extensive margin, this difference may hint towards a behavioral bias in the response to an equivalent decrease in the cost of becoming a donor. At the intensive margin, there is only some marginally significant difference between discounts and rebates at the high subsidy rate, shown in column 4 of Table 3 and columns 5–6 of Table 4. In comparison to the matching subsidies, significant differences arise at neither the extensive nor the intensive margin.

5 Discussion

In our experiment, we find equivalence between matches and rebates as subsidy-based incentives to donors and an equivalence with price discounts. This equivalence under a unit donation scheme contrasts with the existing literature that has examined subsidy types under a money donation scheme and has generally found matches outperforming rebates. This includes papers that also use an online experimental methodology (Bekkers Reference Bekkers, Deck, Fatas, Rosenblat, Isaac and Norton2015; Gandullia and Lezzi Reference Gandullia and Lezzi2018; Gandullia Reference Gandullia2019), two of which recruit from a similar subject pool and use the same endowment level as we do (Gandullia and Lezzi Reference Gandullia and Lezzi2018; Gandullia Reference Gandullia2019). A closer parallel exists with experimental evidence comparing product promotions in the marketing literature. For private goods, matches (bonus packs) and price promotions sometimes perform equally well (Sinha and Smith Reference Sinha and Smith2000; Hardesty and Bearden Reference Hardesty and Bearden2003; Chen et al. Reference Chen, Marmorstein, Tsiros and Rao2012). For charitable goods, however, our finding is unusual.

To guide our intuition about this result, note that as discussed in Sect. 2.2, rebates and matches are no longer theoretically equivalent under a unit donation scheme. When donors face the choice architecture of a unit donation scheme, the minimum net expense required to become a donor is lower under rebates than under matches. This does not hold for a money donation scheme. As a result, the behavior on the extensive margin might be a crucial factor to explain why matches do not outperform rebates in our setting. In line with this reasoning, our results on the extensive margin differ from those obtained in the context of money donations schemes. While we find that rebates attract more donors than matches, Bekkers (Reference Bekkers, Deck, Fatas, Rosenblat, Isaac and Norton2015) finds the opposite by using similar subsidy rates in a standard money donation choice architecture. Furthermore, Gandullia and Lezzi (Reference Gandullia and Lezzi2018) use the same online population, subsidy rates, and endowment levels as we do but focus on a standard money donation scheme. In their experiment, both rebates and matches increase the fraction of donors compared to a no-subsidy condition and effect sizes between the different subsidy types are similar.

Additional evidence that the lower cost of becoming a donor under rebates might drive the results comes from a simple recoding exercise. In our experiment, the minimum positive net donation under a match amounts to $0.50. Under a 33% (50%) rebate, 25% (22%) of donors give less than $0.50. Recoding those subjects as non-donors eliminates any significant difference at the extensive margin, and matches now lead to higher charity receipts than rebates (1.506 vs. 1.437 units at the low subsidy rate and 2.225 vs. 1.707 units at the high subsidy rate), yet differences between the two subsidy types remain statistically insignificant (

![]() and

and

![]() ). Hence, equalizing the cost of becoming a donor ex post moves the subsidy comparison towards the standard result from money donations, namely that matches outperform rebates.

). Hence, equalizing the cost of becoming a donor ex post moves the subsidy comparison towards the standard result from money donations, namely that matches outperform rebates.

The importance of the extensive margin to explain our results is also in line with findings by Diederich et al. (Reference Diederich, Epperson and Goeschl2021). The authors show that using unit instead of money donation schemes affects the propensity to give, with the primary driver being the discrete choice set under unit donation schemes. This characteristic is also responsible for the different cost of becoming a donor between rebates and matches in our experiment. While the discreteness thus appears to be an important factor to explain our results, we cannot exclude the possibility that the other distinct characteristics of unit donation schemes discussed in Sect. 2.1—i.e., the additional information on the effectiveness of a donation and the framing in terms of physical units—may also play a role.Footnote 19 Additional research is required to quantify the relative effects of the different characteristics on the responsiveness to subsidies. One possible approach would be to introduce one characteristic at a time, similar to Diederich et al. (Reference Diederich, Epperson and Goeschl2021), and investigate whether and how the effectiveness of certain subsidy types changes.

Regarding the comparison of the rebate and discount subsidies, the equivalence on the aggregate level accords with our prior expectations. However, our data offers some evidence that rebates are more effective in attracting donors. Although we should await future research to confirm the robustness of this finding, such a difference is surprising given that both subsidies imply the same price of becoming a donor. One speculative explanation is that a donor has the feeling of providing the whole unit of the charitable good herself under the rebate but only a fraction of the unit under the discount. In this case, the donor might derive lower warm glow utility from becoming a donor under the discount than under the rebate.

An interesting question for future research is how the effectiveness of the different subsidy types under a unit donation scheme depends on the level of the unsubsidized unit price. At a given subsidy rate, a larger unsubsidized price increases the absolute difference in the minimum expense required to become a donor between rebates and matches. As a result, the differences on the extensive margin might become more pronounced, which in turn might be sufficient to make the rebate raise more money than the match. In contrast, reducing the unit size might move results closer to what has been found for money donation schemes.

Future research could also help verify the generalizability of our results, for example, with respect to the absolute size of the earned endowment and the relative sizes of unit price and endowment. At $2, the earned endowment is small in absolute terms, even though it is large in the context of the experimental population we recruit. Gandullia and Lezzi (Reference Gandullia and Lezzi2018) and Gandullia (Reference Gandullia2019) use the same endowment level with a similar subject pool and replicate the standard finding of matches outperforming rebates under a money donation scheme. These results hint at generalizability, but more research is needed for the specific case examined in the present paper. At $0.50, the unsubsidized unit price of the charitable good is a quarter of the earned endowment and therefore restricts the room for variation in the donation decision, potentially limiting the scope for identifying differences. Although we still find significant differences between the subsidy and no subsidy conditions as well as between the subsidy types on the extensive and intensive margin, the equivalence of rebates and matches regarding charity receipts merits further examination.

6 Conclusion

This paper defines a class of donations in which donors are asked to choose the number of discrete units of the charitable good to fund instead of the amount of money to give. We call the former a unit donation and the latter a money donation. We present empirical evidence from an online field experiment designed to analyze how different subsidy types affect unit donations. In doing so, we focus on the two prevalent subsidy types, rebates and matches, as well as a subsidy type that is novel to charitable giving and framed as a simple price discount. The latter can be applied since for unit donations, each physical unit has a well-defined price that can be explicitly reduced.

The results remarkably differ from the well-established findings on the performance of subsidy types applied to money donations. Matching subsidies do not outperform rebates but are equally effective in raising funds. Yet matching and rebate subsidies create different responses at the extensive and intensive margin of giving. While rebates significantly increase the fraction of donors, matches produce larger donations. The significantly higher likelihood of giving under rebates compared to matches is in contrast to the money donation literature and appears to be one reason why rebates catch up with matches in the unit donation setting of our experiment. Price discounts raise similar levels of funds as rebates and matches. None of the subsidy types significantly affects net donations.

Our results highlight the relevance of the decision environment when soliciting donations and, thus, have important implications for practitioners. First, charities that employ unit donations in their fundraising efforts cannot rely on the insights from the existing literature on subsidizing money donations. Second, whether it is useful to apply a certain type of subsidy to unit donations depends on a charity’s objectives. Previous research has shown that individuals that donated once are more likely to give in the future. If the charity desires to maximize the set of donors, our evidence suggests that a rebate is preferable over a match. If the charity instead seeks to maximize charity receipts, the choice of the subsidy type seems to be irrelevant, offering some additional degrees of freedom to charities in their campaign design. Third, in cases where funds are not tied to being used as a subsidy, subsidizing unit donations is not necessarily beneficial as on the aggregate it may not crowd in private giving.

Acknowledgements

We wish to thank René Bekkers, Christian Conrad, Mark Ottoni-Wilhelm, Konrad Stahl, the editor at Experimental Economics, and two anonymous referees for their helpful comments. We also thank participants at the 5th Science of Philanthropy Initiative Conference, Indianapolis, the 24th Annual Conference of the European Association of Environmental and Resource Economists, Manchester, the 34th Annual Congress of the European Economic Association, Manchester, and the Annual Conference of the German Economic Association, Leipzig, as well as seminar and workshop audiences at Heidelberg University, the University of Bonn, the University of Mannheim, the Centre for European Economic Research Mannheim, and the Karlsruhe Institute of Technology. We thank Sign of Hope e.V. for cooperation and Woodrow Ahn for language assistance in developing the donation question.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Availability of data and materials

Data for this article is available under https://doi.org/10.11588/data/GANTNY

Code availability

Code for this article is available under https://doi.org/10.11588/data/GANTNY

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.