1 Introduction

A large body of evidence has shown that individuals often care about the welfare of others.Footnote 1 These pro-social individuals typically face a trade-off between their monetary incentives and their other-regarding preferences, and might be tempted to exploit the uncertainty in their decision environment to reduce the tension between the two. In a seminal paper, later replicated by Larson and Capra (Reference Larson and Capra2009) and Feiler (Reference Feiler2014), Dana et al. (Reference Dana, Weber and Kuang2007) exposed this trade-off by showing that individuals behave more selfishly when they are uncertain about the consequences of their choice on others’ payoffs.Footnote 2 The fact that people use the uncertainty in their environment as an excuse for their selfish behavior has been supported by subsequent research. For instance, individuals have been shown to manipulate their beliefs about others’ intentions (Di Tella et al., Reference Di Tella, Perez-Truglia, Babino and Sigman2015; Andreoni & Sanchez, Reference Andreoni and Sanchez2020) or to take advantage of the uncertainty on whether their choices would be implemented (Haisley & Weber, Reference Haisley and Weber2010; Exley, Reference Exley2016; Garcia et al., Reference Garcia, Massoni and Villeval2020) to behave more selfishly.

This growing body of evidence has focused on outcome-based preferences, i.e., preferences over the allocation of payoffs between oneself and others. Yet, pro-social behavior can also be shaped by belief-based preferences, i.e., preferences over the allocation of payoffs between oneself and others that are conditional on beliefs.Footnote 3 For example, let’s imagine that Ann hires Bob to work on a job for her in exchange for a fixed wage. Ann holds private expectations about how much Bob should work on the job, given how much she pays him. If Bob is purely selfish, he maximizes his utility function by providing zero effort, regardless of his beliefs about Ann’s expectations. In contrast, Bob’s preferences regarding his level of effort may be sensitive to Ann’s expectations. For instance, Bob may experience guilt from disappointing Ann’s expectations and feel compelled to provide a high level of effort if he believes Ann expects him to do so. If Bob doesn’t know exactly Ann’s expectations, he may be tempted to use this uncertainty to maintain the belief that Ann does not expect much from him so as to provide little effort without feeling guilty.

We investigate whether individuals with belief-dependent preferences engage in self-serving information acquisition when they are uncertain about others’ expectations. To do so, we examine the information acquisition strategy of decision-makers with belief-dependent preferences who face a conflict between their monetary interest and their other-regarding preferences in the context of a trust game. We first present a theoretical framework adapted from the model of endogenous information acquisition proposed by Spiekermann and Weiss (Reference Spiekermann and Weiss2016). In our framework, the second-mover (‘trustee’) is uncertain about the first-mover’s (‘trustor’) expectations and can acquire information to resolve this uncertainty. We distinguish between trustees with ‘subjective’ preferences (i.e., preferences that depend on what trustees believe about the trustor’s expectations) and trustees with ‘objective’ preferences (i.e., preferences that depend on the trustor’s actual expectations). Within this framework, we demonstrate that it is optimal for trustees with subjective belief-dependent preferences to bias their information acquisition strategy towards signals that reduce the tension between their monetary payoff and their other-regarding preferences.Footnote 4

We then conducted an online experiment in which we can classify trustees as either belief-dependent or belief-independent by observing their decisions in the trust game. As in the theoretical framework, trustees were initially uncertain about the trustors’ expectations and were later provided with an opportunity to acquire information about these expectations. Crucially, trustees faced two information sources that were skewed in opposite directions. This feature of the design allows us to assess whether belief-dependent trustees biased their information search in a way that is congruent with their monetary incentives.

We find that 44% of trustees in our sample can be classified as belief-dependent. Among these belief-dependent trustees, 60.47% strategically acquire signals that lead to higher expected payoffs (i.e., lower amounts sent back to the trustor), which is consistent with our predictions for subjective preferences. Our findings highlight yet another channel through which people make selfish choices while keeping a ‘good conscience’.

Our main contribution is to the literature on strategic information acquisition. While there is extensive evidence that individuals can deliberately remain ignorant about the consequences of their actions (see Golman et al., Reference Golman, Hagmann and Loewenstein2017; Hertwig & Engel, Reference Hertwig and Engel2016 for reviews),Footnote 5 a small body of research has now shown that individuals can also actively seek information if, in expected terms, selfish justifications become more available by doing so. When the information acquisition choice is binary (acquiring the information or not), Fong and Oberholzer-Gee (Reference Fong and Oberholzer-Gee2011) find that dictators who choose to acquire information about why their recipient is ‘poor’ use it as an excuse to reduce their donations. When information is acquired sequentially, individuals stop collecting information earlier when they liked early returns (Ditto & Lopez, Reference Ditto and Lopez1992; Smith et al., Reference Smith, Trivers and von Hippel2017; Chen et al., Reference Chen and Heese2021). We differentiate ourselves from these lines of research by focusing on situations in which individuals can discriminate between sources of information. In this literature, individuals have been shown to prefer positively skewed, confirmatory, or less informative information sources (Spiekermann & Weiss, Reference Spiekermann and Weiss2016; Soraperra et al., Reference Soraperra, van der Weele, Villeval and Shalvi2023; Soldà et al., Reference Soldà, Ke, Page and Von Hippel2020; Charness et al., Reference Charness, Oprea and Yuksel2021; Chopra et al., Reference Chopra, Haaland and Roth2023). The current paper especially relates to Spiekermann and Weiss (Reference Spiekermann and Weiss2016), who allow participants to strategically seek and/or avoid information about the descriptive norms of donations. We add to this emergent literature by showing that individuals can also strategically discriminate between more or less self-serving information sources when information relates to others’ expectations.Footnote 6

We also contribute to a recent strand of papers calling attention to the impact of situational excuses on the expression of belief-dependent preferences (e.g., Balafoutas & Fornwagner, Reference Balafoutas and Fornwagner2017; Inderst et al., Reference Inderst, Khalmetski and Ockenfels2019; Morell, Reference Morell2019). In that respect, we are the first to show that people try to remain uncertain about others’ beliefs to make selfish choices while appearing as if they cared about others. Two studies also studied how the uncertainty about others’ intentions could lead to the formation of self-serving beliefs (Di Tella et al., Reference Di Tella, Perez-Truglia, Babino and Sigman2015; Friedrichsen et al., Reference Friedrichsen, Momsen and Piasenti2022).Footnote 7 Di Tella et al. (Reference Di Tella, Perez-Truglia, Babino and Sigman2015) study a corruption game where dictators are uncertain on whether their recipient is making a ‘side deal’ to obtain a larger benefit from the allocation of tokens. When recipients have the option to make such a deal, dictators are more selfish than when this deal is made randomly by a computer (i.e., without selfish intentions). The authors conclude that dictators distort their beliefs about the recipients’ intentions to justify their selfish allocations. While they investigate how uncertainty affects participants’ beliefs and decisions, we move one step further by studying whether belief-dependent participants adopt self-serving strategies to resolve the uncertainty.

The remainder of the paper is organized as follows. We develop our theoretical model in Sect. 2. In Sect. 3, we present the experimental design used to address our research question. Next, we derive our experimental hypotheses in Sect. 4. In Sect. 5, we describe our empirical results. Finally, we conclude in Sect. 7.

2 Theoretical model

We introduce a modified trust game with incomplete information. The first mover (“trustor”) decides between two actions: In or Out. If the trustor chooses In, the second mover (“trustee”) receives an endowment E to allocate between himself and the trustor.Footnote 8 The trustee returns an amount y (with

![]() ) to the trustor and keeps

) to the trustor and keeps

![]() to himself. If the trustor chooses Out, the game ends, and each player receives an outside option. The trustee receives

to himself. If the trustor chooses Out, the game ends, and each player receives an outside option. The trustee receives

![]() , and the trustor receives

, and the trustor receives

![]() , which depends on the state of the world

, which depends on the state of the world

![]() , with

, with

![]() . The trustor knows her outside option with certainty when choosing between In or Out. In contrast, the trustee does not know the trustor’s outside option when choosing y, but knows that both outside options are equally likely, that is

. The trustor knows her outside option with certainty when choosing between In or Out. In contrast, the trustee does not know the trustor’s outside option when choosing y, but knows that both outside options are equally likely, that is

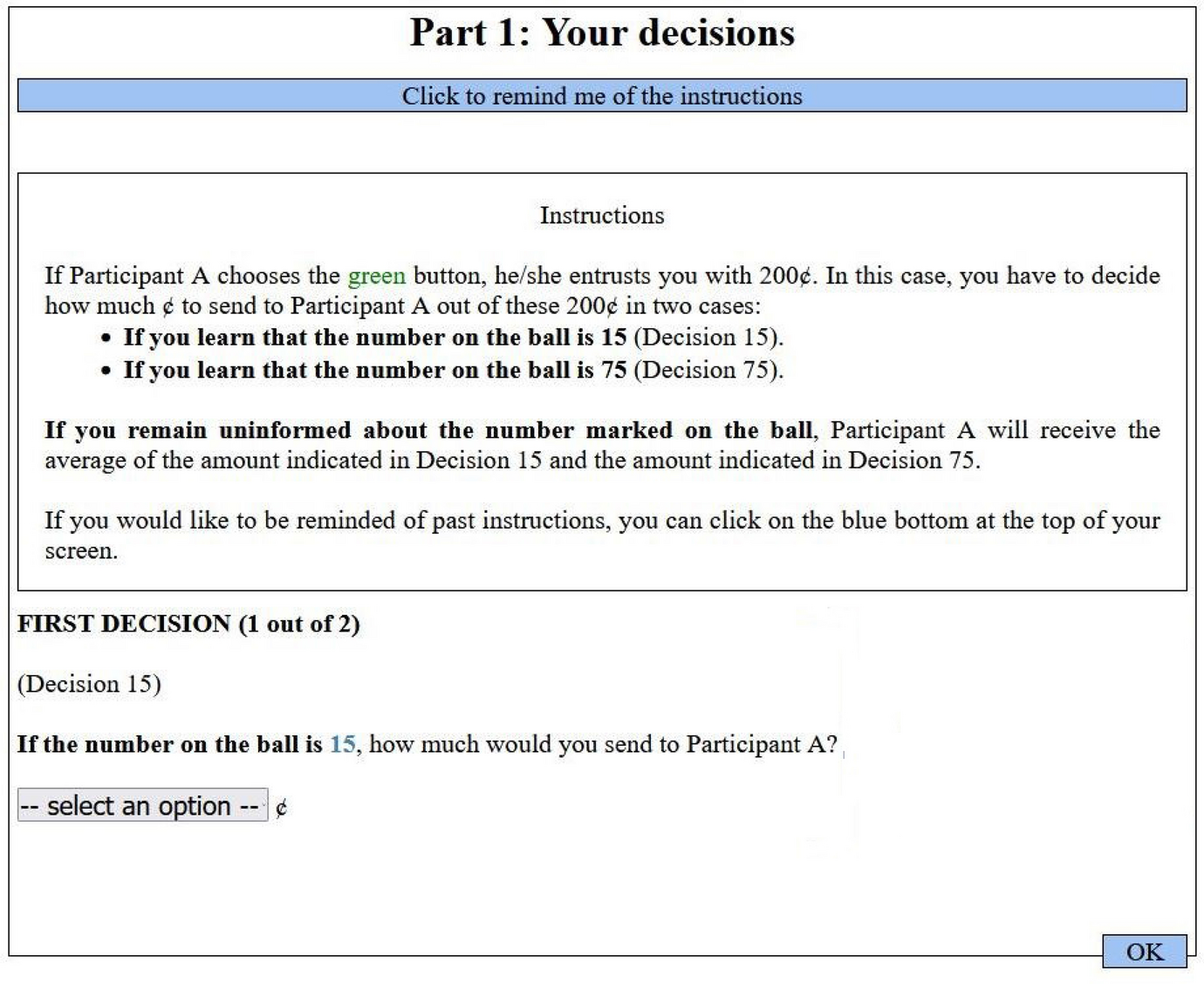

![]() . Importantly, the trustee can acquire costless signals about the trustor’s outside option before choosing how much to return (details in Sect. 2.2). The structure of the game is summarized in Fig. 1.

. Importantly, the trustee can acquire costless signals about the trustor’s outside option before choosing how much to return (details in Sect. 2.2). The structure of the game is summarized in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1 Trust game with High or Low outside option

We define

![]() , the trustor’s expectations about his payoff conditional on choosing In, where

, the trustor’s expectations about his payoff conditional on choosing In, where

![]() ; and

; and

![]() , the trustee’s beliefs about the trustor’s expectations:

, the trustee’s beliefs about the trustor’s expectations:

![]() . We refer to the former as the trustor’s first-order beliefs and to the latter as the trustee’s second-order beliefs.

. We refer to the former as the trustor’s first-order beliefs and to the latter as the trustee’s second-order beliefs.

2.1 Belief formation

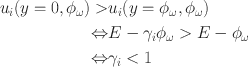

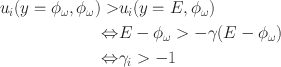

A payoff-maximizing trustor will choose In only if she expects to receive more from doing so than from choosing Out, i.e., when Eq. 1 is satisfied.

Assuming that the distribution of trustors’ first-order beliefs has mass between the two possible values of their outside options, a payoff-maximizing trustor will hold higher beliefs when her outside option is High than when her outside option is Low, conditional on choosing In:

![]() . Using psychological forward induction reasoning (Dufwenberg, Reference Dufwenberg2002), a trustee will be able to infer Eq. 1.Footnote 9 More precisely, the trustee understands that a trustor will only choose In if she expects to receive at least her outside option by doing so. Hence, the trustee’s second-order beliefs also increase in the trustor’s outside option:

. Using psychological forward induction reasoning (Dufwenberg, Reference Dufwenberg2002), a trustee will be able to infer Eq. 1.Footnote 9 More precisely, the trustee understands that a trustor will only choose In if she expects to receive at least her outside option by doing so. Hence, the trustee’s second-order beliefs also increase in the trustor’s outside option:

![]() . It leads to the following assumption.

. It leads to the following assumption.

Assumption

Conditional on choosing In, trustors’ first-order beliefs and trustees’ second-order beliefs are higher when the outside option is High rather than Low.

Note that we make the implicit assumption that the trustor’s outside option only affects trustees’ behavior through these second-order beliefs. We discuss the implication of this assumption in more details in Sect. 6.

2.2 Belief-dependent preferences

The core of our analysis focuses on individuals with belief-dependent preferences. A belief-dependent trustee’s utility function (Eq. 2) depends on his material payoff,

![]() , and his belief-dependent motivation,

, and his belief-dependent motivation,

![]() . The belief-dependent motivation (Eq. 3) is the absolute difference between how much the trustor expects to receive (

. The belief-dependent motivation (Eq. 3) is the absolute difference between how much the trustor expects to receive (

![]() ) and how much the trustor actually receives (y). This psychological component of the utility function is weighted by the trustee’s sensitivity to his belief-dependent motivation, denoted

) and how much the trustor actually receives (y). This psychological component of the utility function is weighted by the trustee’s sensitivity to his belief-dependent motivation, denoted

![]() (Eq. 3), which can be positive or negative. When

(Eq. 3), which can be positive or negative. When

![]() , the trustee experiences a psychological cost from returning an amount y that deviates from the trustor’s expectations. This cost can stem from various psychological considerations such as cognitive dissonance (Festinger, Reference Festinger1962), a distaste for violating social norms (Spiekermann & Weiss, Reference Spiekermann and Weiss2016), an aversion to inflict reliance damage (Sengupta & Vanberg, Reference Sengupta and Vanberg2023), or guilt-aversion (Battigalli & Dufwenberg, Reference Battigalli and Dufwenberg2007). When

, the trustee experiences a psychological cost from returning an amount y that deviates from the trustor’s expectations. This cost can stem from various psychological considerations such as cognitive dissonance (Festinger, Reference Festinger1962), a distaste for violating social norms (Spiekermann & Weiss, Reference Spiekermann and Weiss2016), an aversion to inflict reliance damage (Sengupta & Vanberg, Reference Sengupta and Vanberg2023), or guilt-aversion (Battigalli & Dufwenberg, Reference Battigalli and Dufwenberg2007). When

![]() , the trustee experiences a psychological gain from deviating from the trustor’s expectations. This behavior, while less intuitive at first sight, is also consistent with a wide range of psychological traits including a preference to surprise others (Khalmetski et al., Reference Khalmetski, Ockenfels and Werner2015) or a preference to reward ‘benevolence’, which relates to the concept of expectation-based reciprocity (Dufwenberg & Kirchsteiger, Reference Dufwenberg and Kirchsteiger2004).Footnote 10

, the trustee experiences a psychological gain from deviating from the trustor’s expectations. This behavior, while less intuitive at first sight, is also consistent with a wide range of psychological traits including a preference to surprise others (Khalmetski et al., Reference Khalmetski, Ockenfels and Werner2015) or a preference to reward ‘benevolence’, which relates to the concept of expectation-based reciprocity (Dufwenberg & Kirchsteiger, Reference Dufwenberg and Kirchsteiger2004).Footnote 10

The optimal amount

![]() the trustee returns to the trustor depends on the trustee’s sensitivity to his belief-dependent motives: When

the trustee returns to the trustor depends on the trustee’s sensitivity to his belief-dependent motives: When

![]() , the trustee assigns a higher weight to his monetary payoff than to his belief-dependent motivation. Therefore, he will behave as a payoff-maximizer and return

, the trustee assigns a higher weight to his monetary payoff than to his belief-dependent motivation. Therefore, he will behave as a payoff-maximizer and return

![]() .Footnote 11 When

.Footnote 11 When

![]() , the trustee assigns more value to his belief-dependent motivation than to his monetary payoff. In other words, he is ‘sufficiently belief-dependent’ so that his choices could be distinguishable from those of a payoff-maximizer. This second case splits into two: When

, the trustee assigns more value to his belief-dependent motivation than to his monetary payoff. In other words, he is ‘sufficiently belief-dependent’ so that his choices could be distinguishable from those of a payoff-maximizer. This second case splits into two: When

![]() , the trustee experiences a psychological cost from deviating from the trustor’s expectations, and

, the trustee experiences a psychological cost from deviating from the trustor’s expectations, and

![]() is maximized for

is maximized for

![]() . We refer to such trustees as ‘belief-concordant’. When

. We refer to such trustees as ‘belief-concordant’. When

![]() , the trustee experiences a psychological gain from deviating from the trustor’s expectations and

, the trustee experiences a psychological gain from deviating from the trustor’s expectations and

![]() depends on the level of

depends on the level of

![]() . When

. When

![]() ,

,

![]() is maximized for

is maximized for

![]() . When

. When

![]() ,

,

![]() is maximized for

is maximized for

![]() when

when

![]() , and

, and

![]() otherwise. We refer to such trustees as ‘belief-discordant’. Proposition Footnote 1 below summarizes the optimal amount returned

otherwise. We refer to such trustees as ‘belief-discordant’. Proposition Footnote 1 below summarizes the optimal amount returned

![]() depending on

depending on

![]() and

and

![]() . The proofs are provided in the Appendix A.2.

. The proofs are provided in the Appendix A.2.

Proposition 1

When

![]() , belief-dependent trustees return

, belief-dependent trustees return

![]() . When

. When

![]() , belief-dependent trustees return

, belief-dependent trustees return

![]() . When

. When

![]() , belief-dependent trustees return either

, belief-dependent trustees return either

![]() or

or

![]() depending on the level of

depending on the level of

![]() .

.

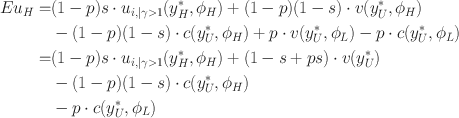

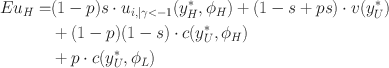

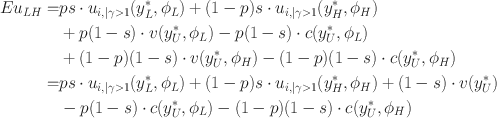

In the remainder of this section, we restrict our analysis to the case where the trustee faces a trade-off between his monetary payoff and his belief-dependent motivations (i.e., sufficiently belief-dependent trustee). Since very few trustees can be classified as belief-discordant in our experiment and both cases are symmetric, we provide the details of the analysis for belief-concordant trustees in the main text below and relegate the corresponding analysis for belief-discordant to Appendix A.1.

Decision Under Certainty. Let

![]() =

=

![]()

![]() be the maximum utility achievable for a belief-concordant trustee for a given expectation of the trustor

be the maximum utility achievable for a belief-concordant trustee for a given expectation of the trustor

![]() . This function decreases with

. This function decreases with

![]() : the higher the expectations of the trustor, the less the trustee keeps for himself. The proof is provided in Sect. A.3. Recalling our auxiliary assumption, which states that

: the higher the expectations of the trustor, the less the trustee keeps for himself. The proof is provided in Sect. A.3. Recalling our auxiliary assumption, which states that

![]() , it follows that

, it follows that

![]() . When the trustor’s expectations are low, a belief-concordant trustee reaches the maximum utility

. When the trustor’s expectations are low, a belief-concordant trustee reaches the maximum utility

![]() by returning

by returning

![]() . When the trustor’s expectations are high, the maximum utility

. When the trustor’s expectations are high, the maximum utility

![]() is reached by returning

is reached by returning

![]() .

.

Decision Under Uncertainty. We now turn to the situation where the trustee is initially uncertain about the trustor’s expectation ex-ante and can acquire costless signals about the trustor’s expectation before choosing how much to return. We define

![]() as the updated probability that the trustor’s expectation is Low after the acquisition of signal(s). The trustee can acquire one or two types of signals, represented by the random variables

as the updated probability that the trustor’s expectation is Low after the acquisition of signal(s). The trustee can acquire one or two types of signals, represented by the random variables

![]() and

and

![]() . With probability s, the signal

. With probability s, the signal

![]() reveals the true expectation of the trustor, that is, the signal reveals that the trustor’s expectation is Low if the trustor’s expectation is indeed Low (

reveals the true expectation of the trustor, that is, the signal reveals that the trustor’s expectation is Low if the trustor’s expectation is indeed Low (

![]() ); or that the trustor’s expectation is High if the trustor’s expectation is indeed High (

); or that the trustor’s expectation is High if the trustor’s expectation is indeed High (

![]() ); and with probability

); and with probability

![]() , the signal does not reveal the trustor’s expectation (null signal,

, the signal does not reveal the trustor’s expectation (null signal,

![]() ). After a null signal, the trustee updates the probability p using Bayes’ rule, which yields a posterior of

). After a null signal, the trustee updates the probability p using Bayes’ rule, which yields a posterior of

![]() after

after

![]() and

and

![]() after

after

![]() . Finally, if the trustee receives both

. Finally, if the trustee receives both

![]() and

and

![]() , no update is necessary as the two signals cancel out each other:

, no update is necessary as the two signals cancel out each other:

![]() .

.

Objective vs. Subjective preferences. To analyze the information acquisition strategy of a belief-concordant trustee, we distinguish between objective and subjective preferences. For a belief-concordant trustee with objective preferences, the psychological cost from a mismatch depends on what the trustor’s true expectation

![]() actually is. Therefore, his psychological component is a function of

actually is. Therefore, his psychological component is a function of

![]() which can take two values, either

which can take two values, either

![]() when the trustor’s expectation is Low or

when the trustor’s expectation is Low or

![]() when the trustor’s expectation is High. In contrast, for a belief-concordant trustee with subjective preferences, the psychological cost from a mismatch depends on his second-order belief

when the trustor’s expectation is High. In contrast, for a belief-concordant trustee with subjective preferences, the psychological cost from a mismatch depends on his second-order belief

![]() about the trustor’s expectation, and not on the trustor’s actual expectation. Crucially, under uncertainty,

about the trustor’s expectation, and not on the trustor’s actual expectation. Crucially, under uncertainty,

![]() can differ from

can differ from

![]() .

.

Objective Preferences Under Uncertainty. Under uncertainty, a belief-concordant trustee with objective preferences cannot be sure to choose the action that minimizes his psychological cost and must instead minimize the expected psychological cost given by:

![]() . Therefore, the maximum expected utility under uncertainty for a given p is achieved when the trustee returns the amount

. Therefore, the maximum expected utility under uncertainty for a given p is achieved when the trustee returns the amount

![]() . Now recall that a belief-concordant trustee with objective belief-dependent preferences maximizes his utility when his return matches the trustor’s actual expectation. This implies that

. Now recall that a belief-concordant trustee with objective belief-dependent preferences maximizes his utility when his return matches the trustor’s actual expectation. This implies that

![]() and

and

![]() . Hence, the information acquisition strategy that maximizes his utility is to acquire both signals, as it maximizes his chances to learn about the trustor’s actual expectation and therefore return the optimal amount

. Hence, the information acquisition strategy that maximizes his utility is to acquire both signals, as it maximizes his chances to learn about the trustor’s actual expectation and therefore return the optimal amount

![]() . The proof is provided in Sect. A.4.

. The proof is provided in Sect. A.4.

Proposition 2

Objective belief-concordant trustees acquire both signals.

Subjective Preferences Under Uncertainty. For a belief-concordant trustee with subjective preferences, his psychological cost from a mismatch depends on the epistemic state of the world

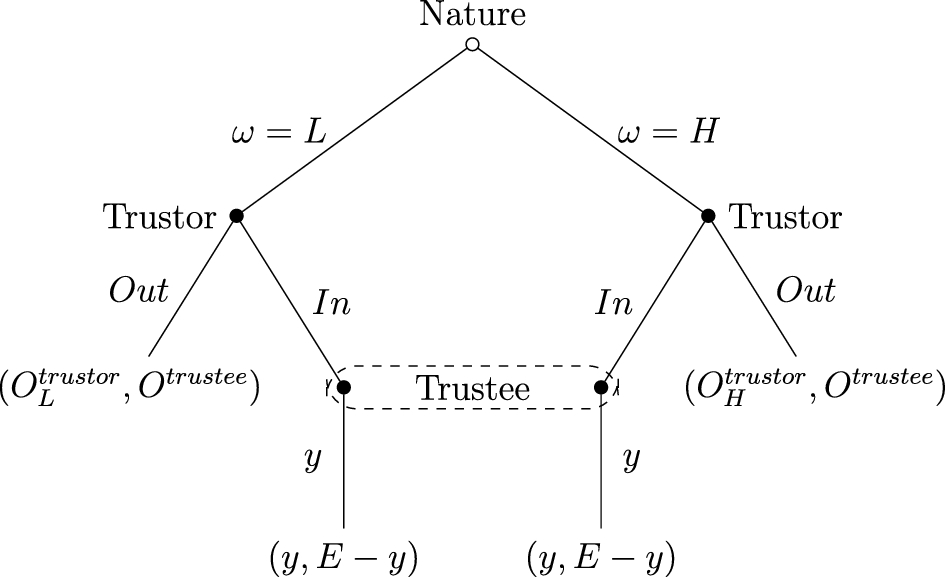

![]() . We follow Spiekermann and Weiss (Reference Spiekermann and Weiss2016) in proposing a coarse mapping from states to beliefs defined as the step function

. We follow Spiekermann and Weiss (Reference Spiekermann and Weiss2016) in proposing a coarse mapping from states to beliefs defined as the step function

![]() (Eq. 4) characterized by the probability p that the state is Low.Footnote 12 As in Spiekermann and Weiss (Reference Spiekermann and Weiss2016), we consider three epistemic states: knowing that the trustor’s actual expectation is Low (

(Eq. 4) characterized by the probability p that the state is Low.Footnote 12 As in Spiekermann and Weiss (Reference Spiekermann and Weiss2016), we consider three epistemic states: knowing that the trustor’s actual expectation is Low (

![]() ), knowing that the trustor’s actual expectation is High (

), knowing that the trustor’s actual expectation is High (

![]() ), or not knowing the trustor’s actual expectation (

), or not knowing the trustor’s actual expectation (

![]() ). In Eq. 4, the parameter

). In Eq. 4, the parameter

![]() represents the degree of ‘caution’ with which a subjective trustee interprets any probability p. As

represents the degree of ‘caution’ with which a subjective trustee interprets any probability p. As

![]() tends to 1/2, the trustee treats any probability p greater than 1/2 as if

tends to 1/2, the trustee treats any probability p greater than 1/2 as if

![]() , and any probability lower than 1/2 as if

, and any probability lower than 1/2 as if

![]() . Note that, when

. Note that, when

![]() , the state

, the state

![]() disappears. Symmetrically, as

disappears. Symmetrically, as

![]() tends to zero, the trustee becomes more ‘cautious’ in his interpretation of p. Crucially, we are making the assumption that a null signal never removes uncertainty to ensure that any update from p to

tends to zero, the trustee becomes more ‘cautious’ in his interpretation of p. Crucially, we are making the assumption that a null signal never removes uncertainty to ensure that any update from p to

![]() does not change

does not change

![]() . It implies

. It implies

![]() .

.

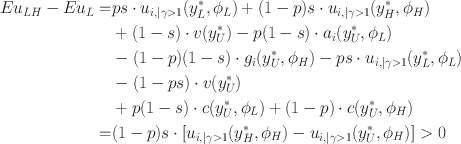

Unlike belief-concordant trustees with objective preferences, a belief-concordant trustee with subjective preferences conditions the amount to be returned on

![]() and not

and not

![]() . Recall that the maximum utility achievable is decreasing in the trustor’s expectations. This implies that

. Recall that the maximum utility achievable is decreasing in the trustor’s expectations. This implies that

![]() . Consequently, a belief-concordant trustee with subjective preferences will sample information from the signal

. Consequently, a belief-concordant trustee with subjective preferences will sample information from the signal

![]() only, as it increases the probability of receiving the highest utility

only, as it increases the probability of receiving the highest utility

![]() without any down-side risk.Footnote 13 The proof is provided in Sect. A.5.

without any down-side risk.Footnote 13 The proof is provided in Sect. A.5.

Proposition 3

Subjective belief-concordant trustees acquire a Low signal only.Footnote 14

To summarize, belief-concordant trustees would prefer to be in the state where the trustor’s expectation is low so as to return little, irrespective of whether their preferences are objective or subjective. However, a belief-concordant trustee with objective preferences cares about the trustor’s actual expectation

![]() and is therefore better off with more information as he cannot change the state he is in. In contrast, a belief-concordant trustees with subjective preferences only cares about his beliefs

and is therefore better off with more information as he cannot change the state he is in. In contrast, a belief-concordant trustees with subjective preferences only cares about his beliefs

![]() about the trustor’s expectation and therefore has an incentive to strategically acquire information that maximizes his chances to learn that the trustor’s expectations are low.

about the trustor’s expectation and therefore has an incentive to strategically acquire information that maximizes his chances to learn that the trustor’s expectations are low.

2.3 Belief-independent preferences

Some trustees may return the same amount y irrespective of their belief about the trustor’s expectations. For instance, a pure payoff-maximizing trustee will always return zero, and an inequality-averse trustee will return the same positive amount (at most

![]() ) regardless of his beliefs about the trustor’s expectations. Because our research question focuses on belief-dependent preferences, we pool these preference types together under the label ‘belief-independent’ preferences. Our theoretical model is agnostic regarding what belief-independent trustees should do. This is because the information is payoff-irrelevant to them, as (by definition) belief-independent trustees return the same amount irrespective of their beliefs about the trustor’s expectations. Hence, they have no incentives to systematically favor one information source over the other.

) regardless of his beliefs about the trustor’s expectations. Because our research question focuses on belief-dependent preferences, we pool these preference types together under the label ‘belief-independent’ preferences. Our theoretical model is agnostic regarding what belief-independent trustees should do. This is because the information is payoff-irrelevant to them, as (by definition) belief-independent trustees return the same amount irrespective of their beliefs about the trustor’s expectations. Hence, they have no incentives to systematically favor one information source over the other.

3 Design

To test our theoretical predictions, we designed an experiment that mimics the theoretical framework described in Sect. 2. Within this framework, we first introduced uncertainty about the trustors’ expectations and then provided trustees with an opportunity to acquire information to alleviate this uncertainty.

3.1 Experiment outline

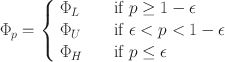

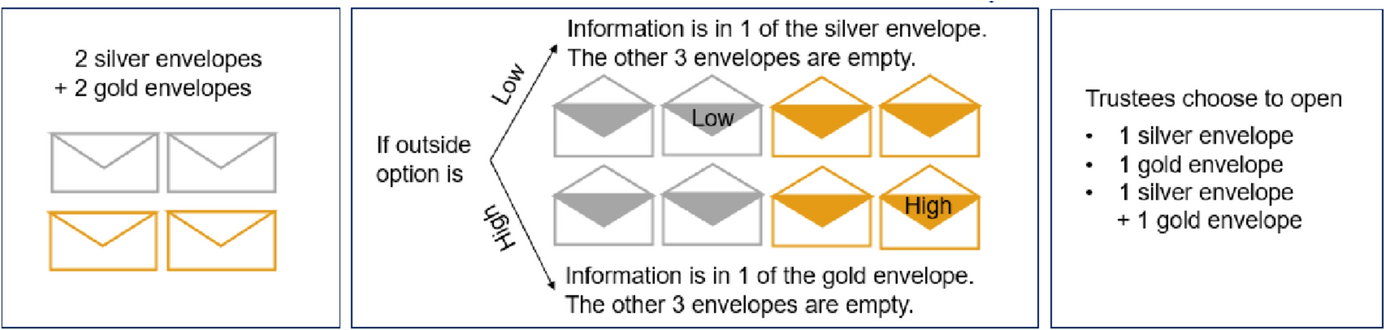

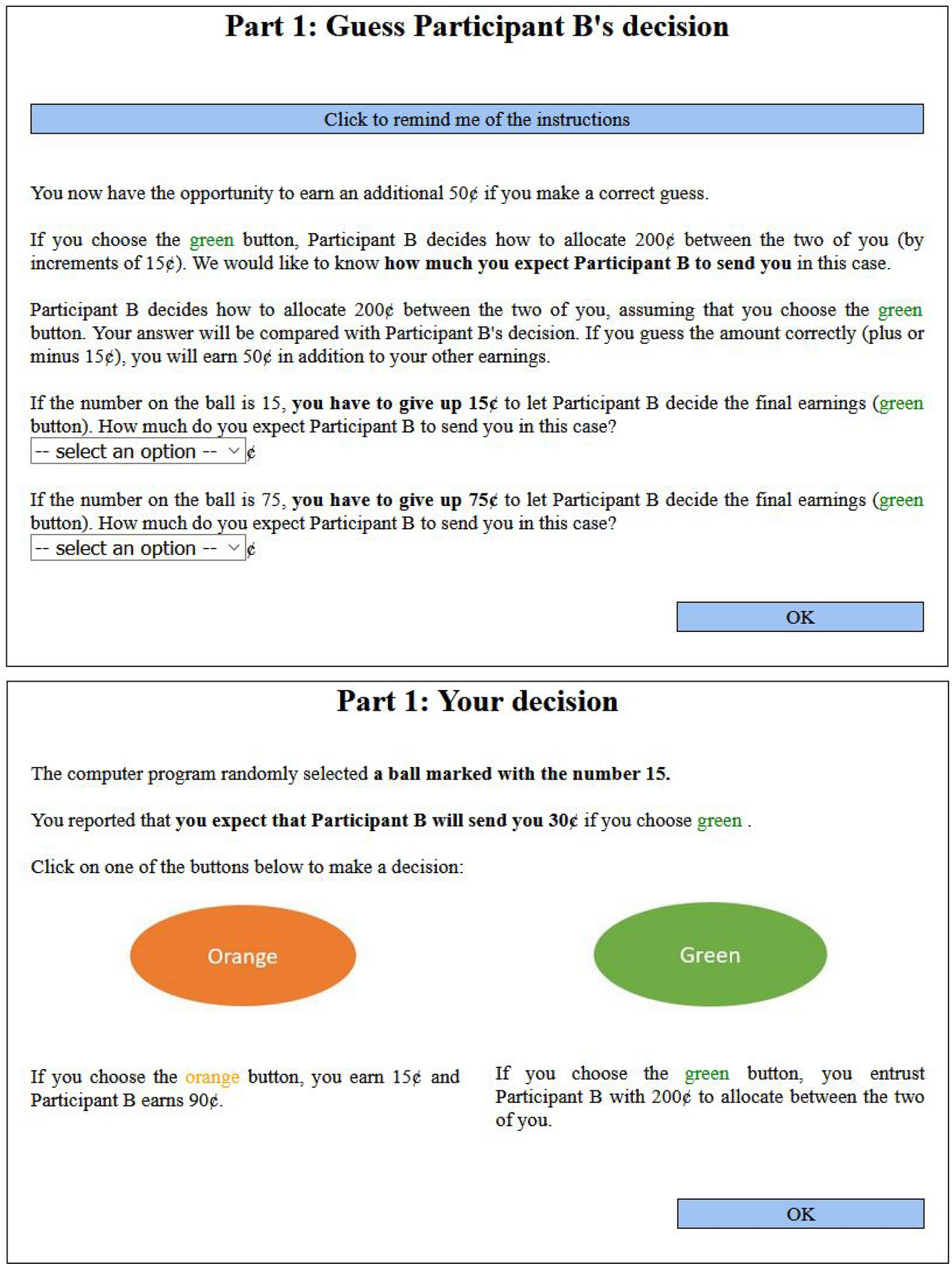

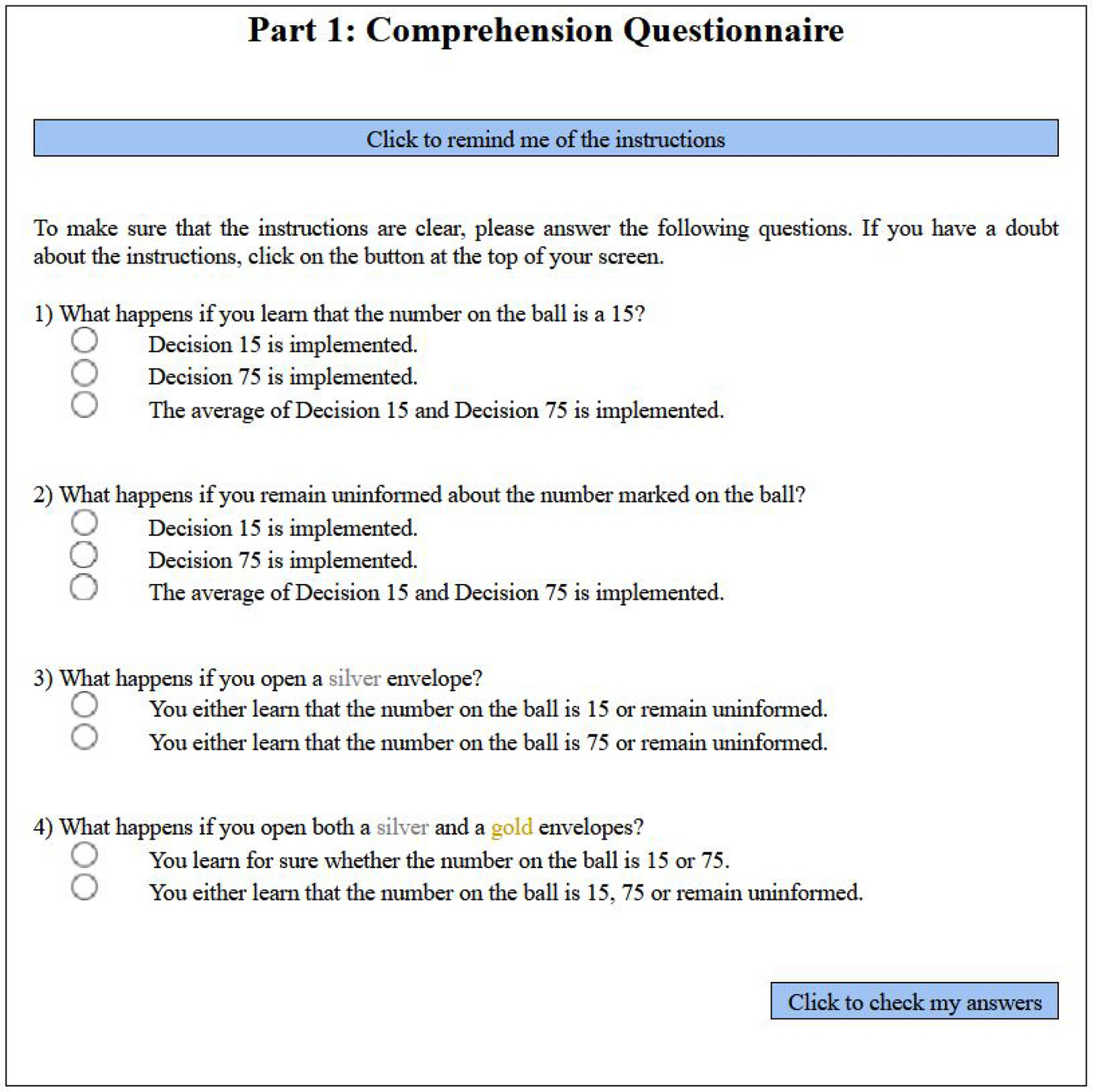

Trust game. At the beginning of the experiment, participants are randomly allocated to either the role of a trustor or trustee. A trustor faces two options: Out and In. If she chooses Out, the game ends, and both players receive their respective outside option. The trustees’ outside option is equal to 90 cents.Footnote 15 In contrast, the trustors’ outside option depends on the game being played. If a trustor chooses In, she foregoes her outside option. As a consequence, the trustee receives 200 cents to allocate between himself and his trustor in increments of 15 cents. Both the trustor and the trustee are informed of the entire payoff structure, including the existence of two equally likely outside options for the trustor. However, trustors are informed about their outside option before they make their decision, while trustees do not know which of the two outside options the trustor is facing at the time of decision.

Outside option manipulation. The trustor’s outside option depends on the game being played. In the Low game, trustors receive 15 cents if they choose Out. In contrast, trustors receive 75 cents if they choose Out in the High game. This feature of the design creates an exogenous variation in the participant’s beliefs about the trustor’s expected payoffs from choosing In. We operate under the assumption that trustors who choose In expect a return at least equal to the outside option that they were willing to forego. Therefore, conditional on choosing In, (i) trustors’ first-order beliefs about their own payoff should be higher when the outside option is High rather than Low, and (ii) anticipating this, trustees’ second-order beliefs about the trustors’ payoff should also be higher when the outside option is High rather than Low.

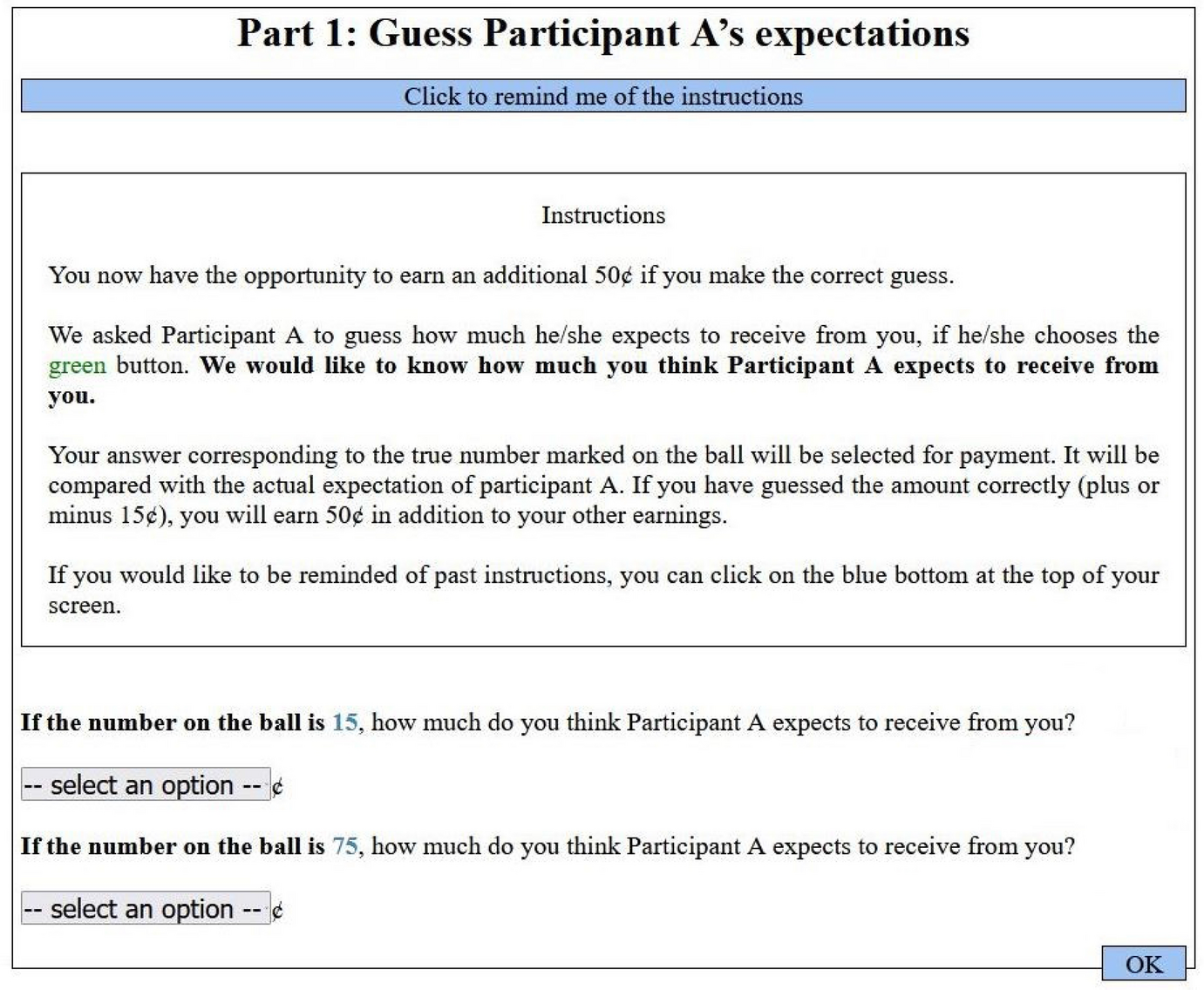

Beliefs elicitation. Before trustors learn whether they are playing the Low game or the High game, we elicit their conditional beliefs about their expected payoffs from choosing In using the strategy method. More specifically, we ask trustors to indicate how much they expect to receive from their trustee if they choose In in the Low game and how much they expect to receive in the High game. Trustors’ beliefs corresponding to the true state of the world are then matched with their trustee’s decision. If a trustor’s belief is accurate, with a 15 cents margin of error, he or she is paid 50 cents. Using a similar method, we also asked trustees to indicate how much they believed their trustor expected to receive if they chose In, both in the Low game and the High game. Trustees’ beliefs corresponding to the true state of the world are then matched with their trustor’s belief in that state. Trustees receive 50 cents if their beliefs are accurate with a 15 cents margin of error.

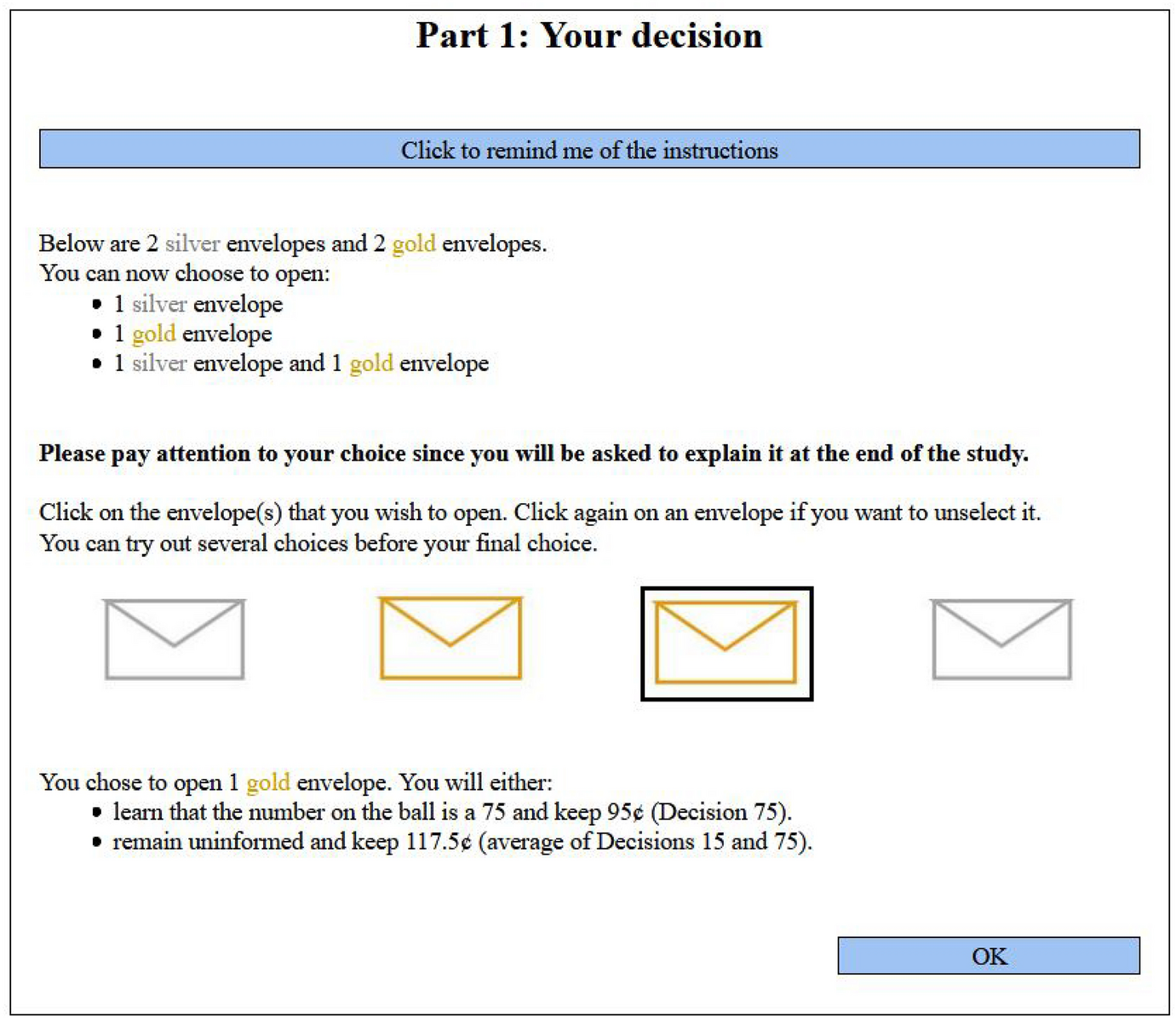

Trustee’s return choices. Because trustees do not know their trustor’s actual outside option at the time of their decision, we elicit how much trustees want to send to the trustor both (i) in case they learn that the outside option is Low (Decision Low) and (ii) in case they learn that the outside option is High (Decision High).Footnote 16 Trustees are informed that if they learn that the trustor’s actual outside option is Low, Decision Low is implemented. Symmetrically, if they learn that the trustor’s actual option is High, Decision High is implemented. If they remain uninformed about their trustor’s actual outside option, the trustor receives the average of Decision Low and Decision High. This key feature of the design, inspired by the ‘menu’ method of Bellemare et al. (Reference Bellemare, Sebald and Strobel2011), is crucial to identify trustees with belief-dependent preferences.Footnote 17 Indeed, because trustors’ outside options are designed to induce a shift in beliefs, eliciting trustees’ returns conditional on their knowledge of the different outside options is equivalent to eliciting their choices conditional on the trustors’ first-order beliefs.

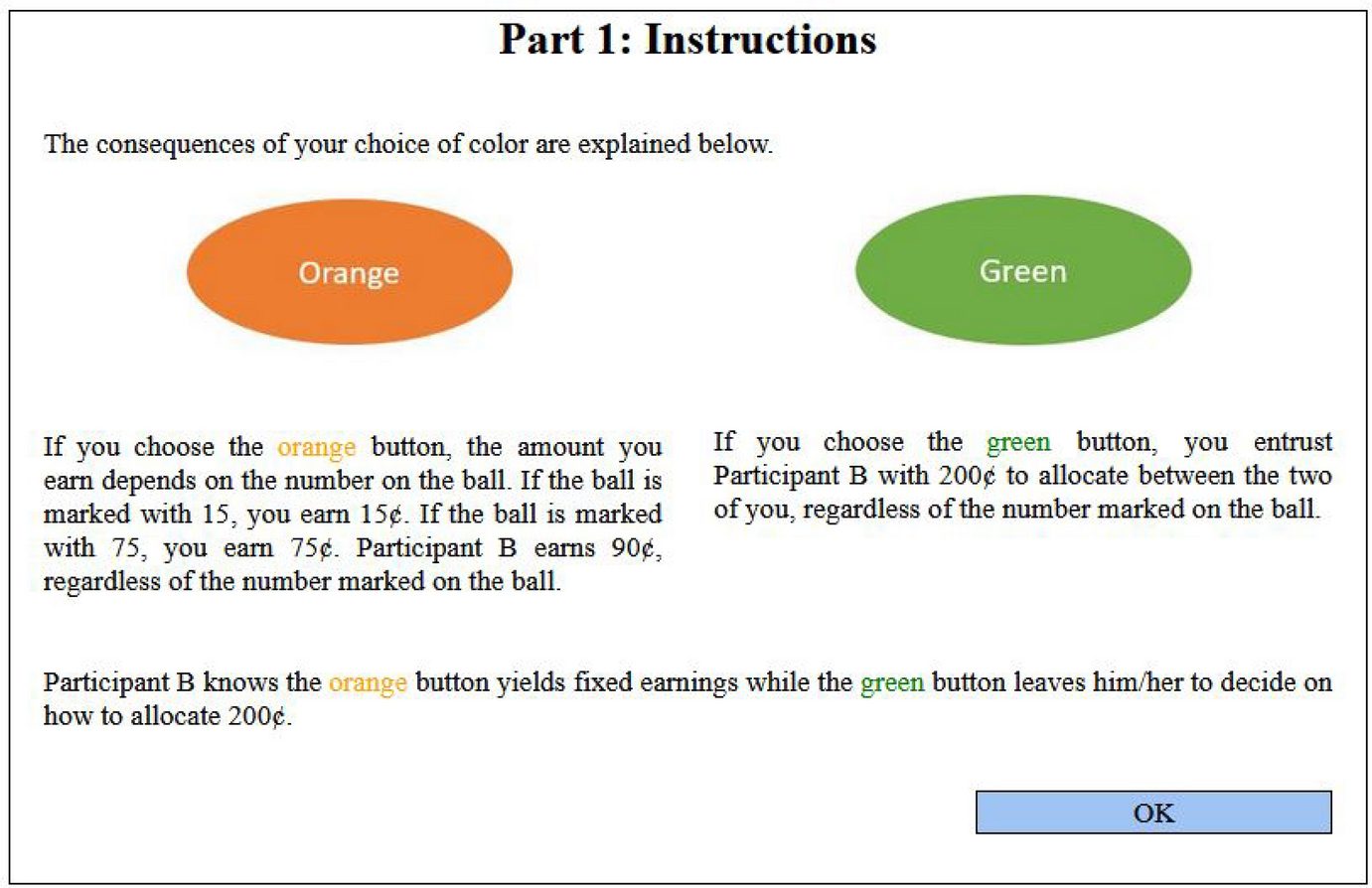

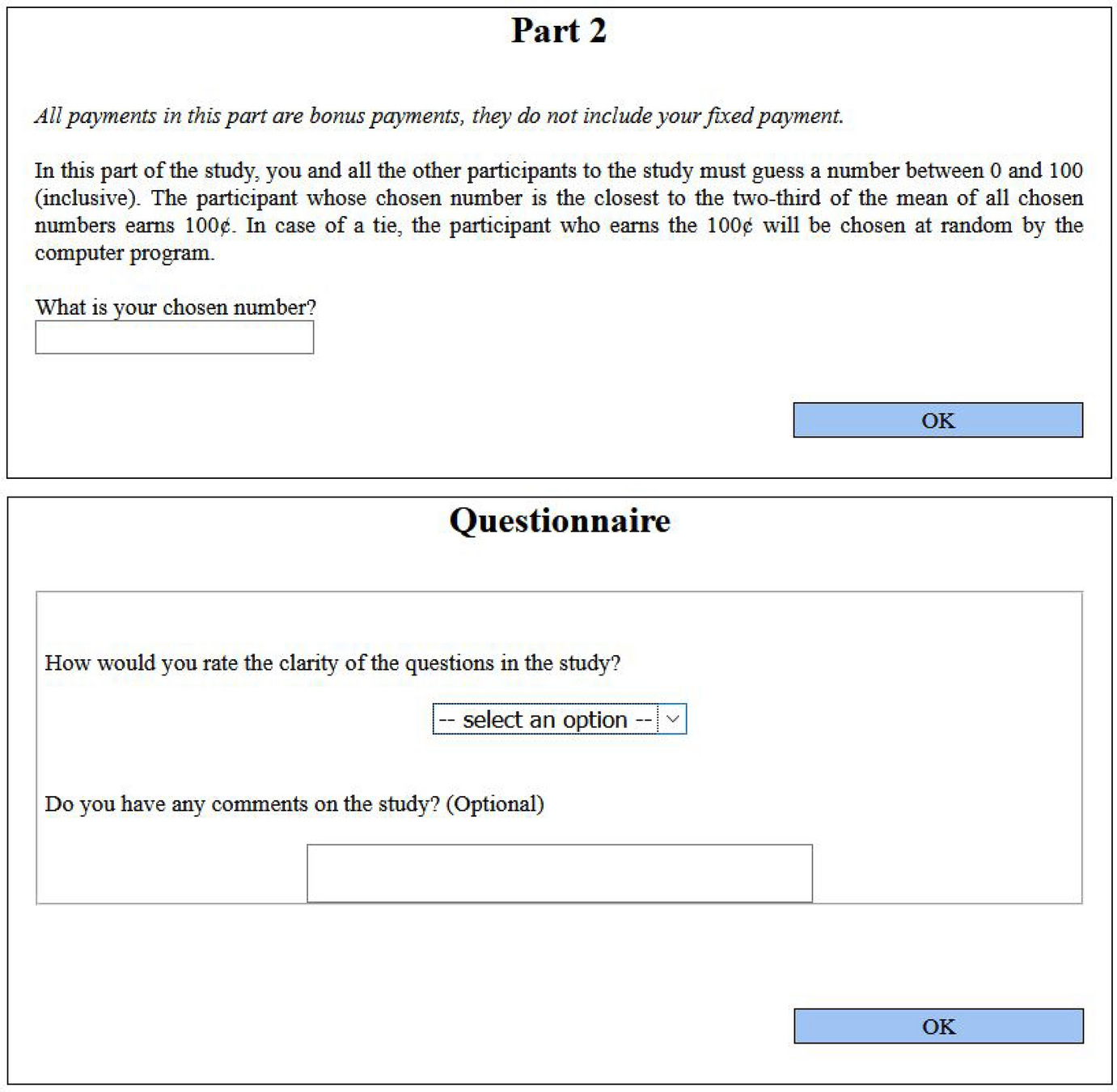

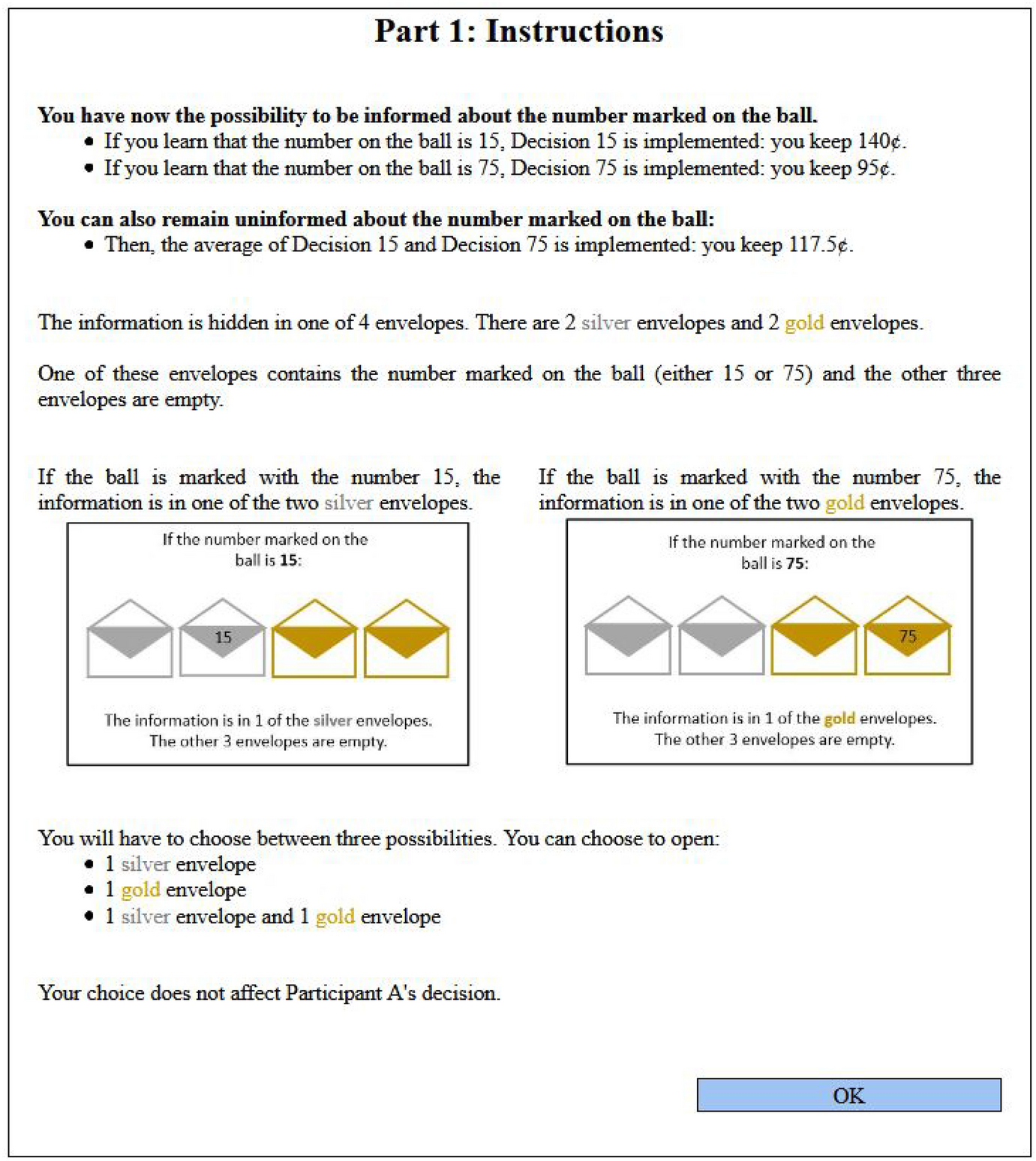

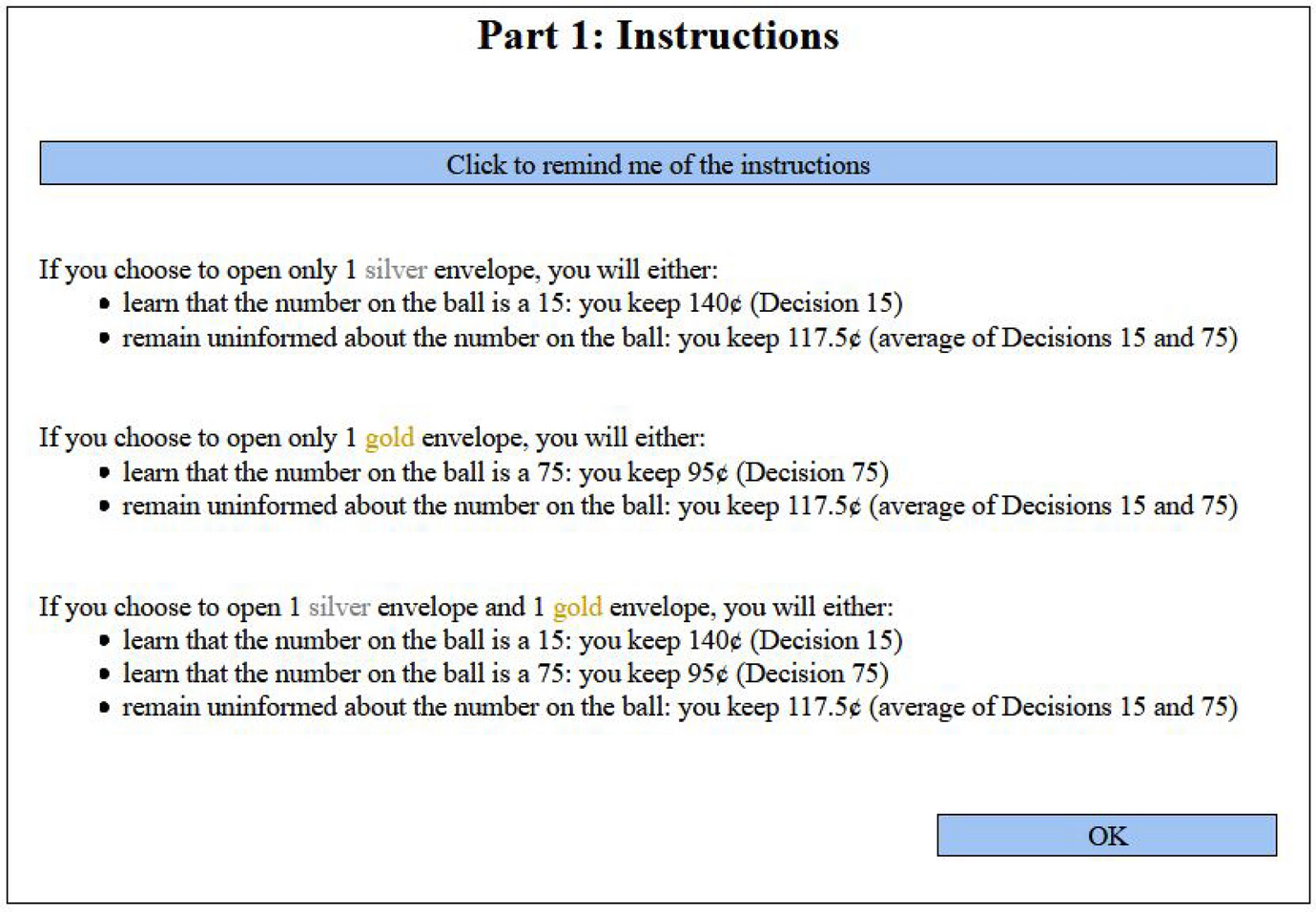

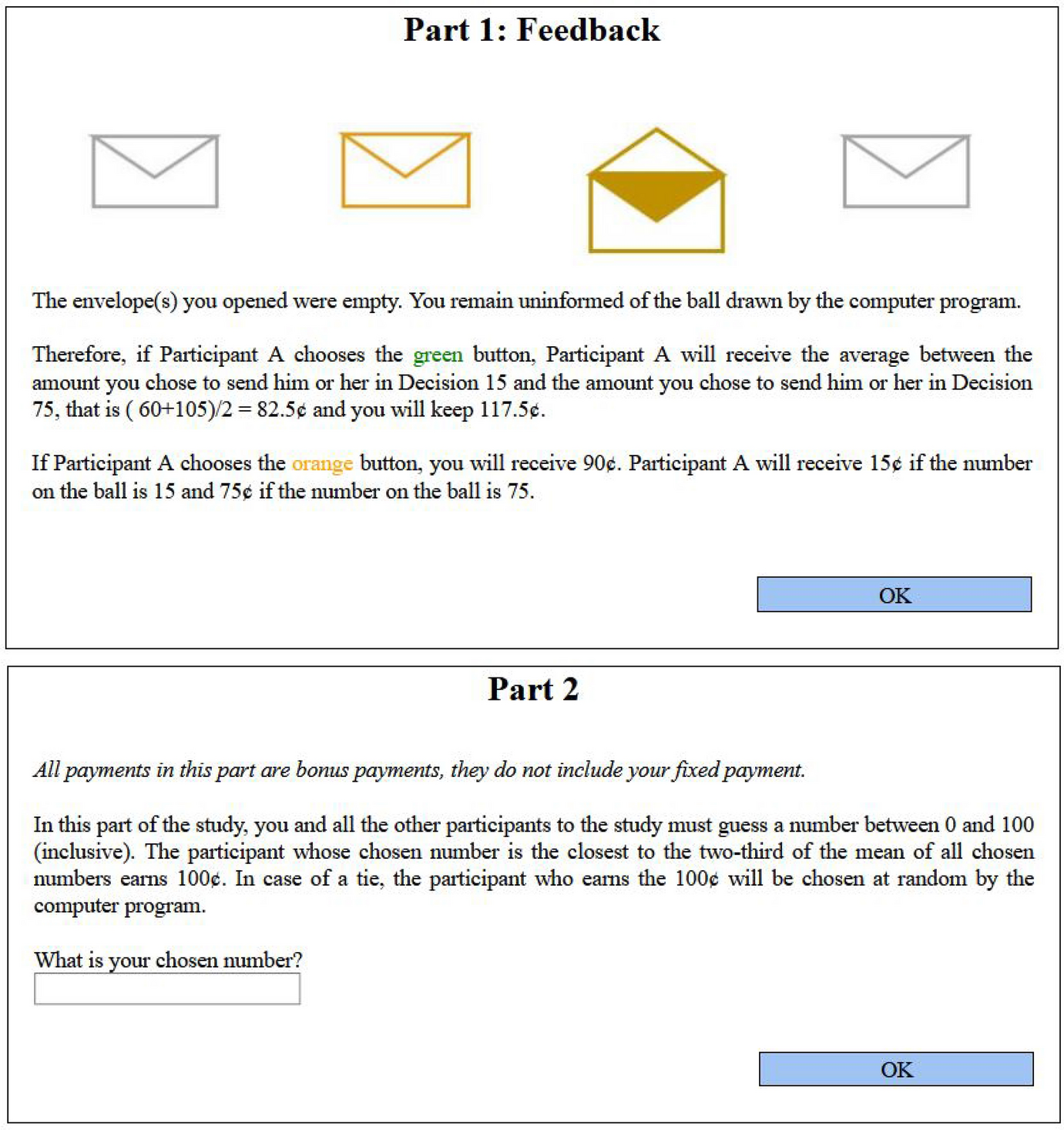

Trustee’s information acquisition. After making their conditional transfer decisions, trustees are unexpectedly offered the opportunity to acquire information about their trustor’s outside option.Footnote 18 We use an information structure similar to Spiekermann and Weiss (Reference Spiekermann and Weiss2016): Trustees face four envelopes of two different colors: silver and gold. Trustees know that if their trustor’s outside option is Low, the information is in one of the two silver envelopes, and the three other envelopes are empty. In contrast, if their trustor’s outside option is High, the information is in one of the two gold envelopes, and the three other envelopes are empty. Hence, a silver envelope can never reveal that the trustor’s outside option is high, and a gold envelope can never reveal that the trustor’s outside option is low. Trustees can choose to open either (i) one silver envelope, (ii) one gold envelope, or (iii) one silver and one gold. The order of presentation of the envelopes was randomized at the participant level. While opening one envelope from each color maximizes the chances to learn the trustor’s actual outside option, a trustee can strategically bias his information acquisition by opening a single envelope only. After selecting which envelope they wish to open, trustees are informed about the content of the selected envelopes, and the computer program automatically implements the corresponding transfer decision.Footnote 19 The information acquisition procedure is summarized in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2 Choosing a source of information

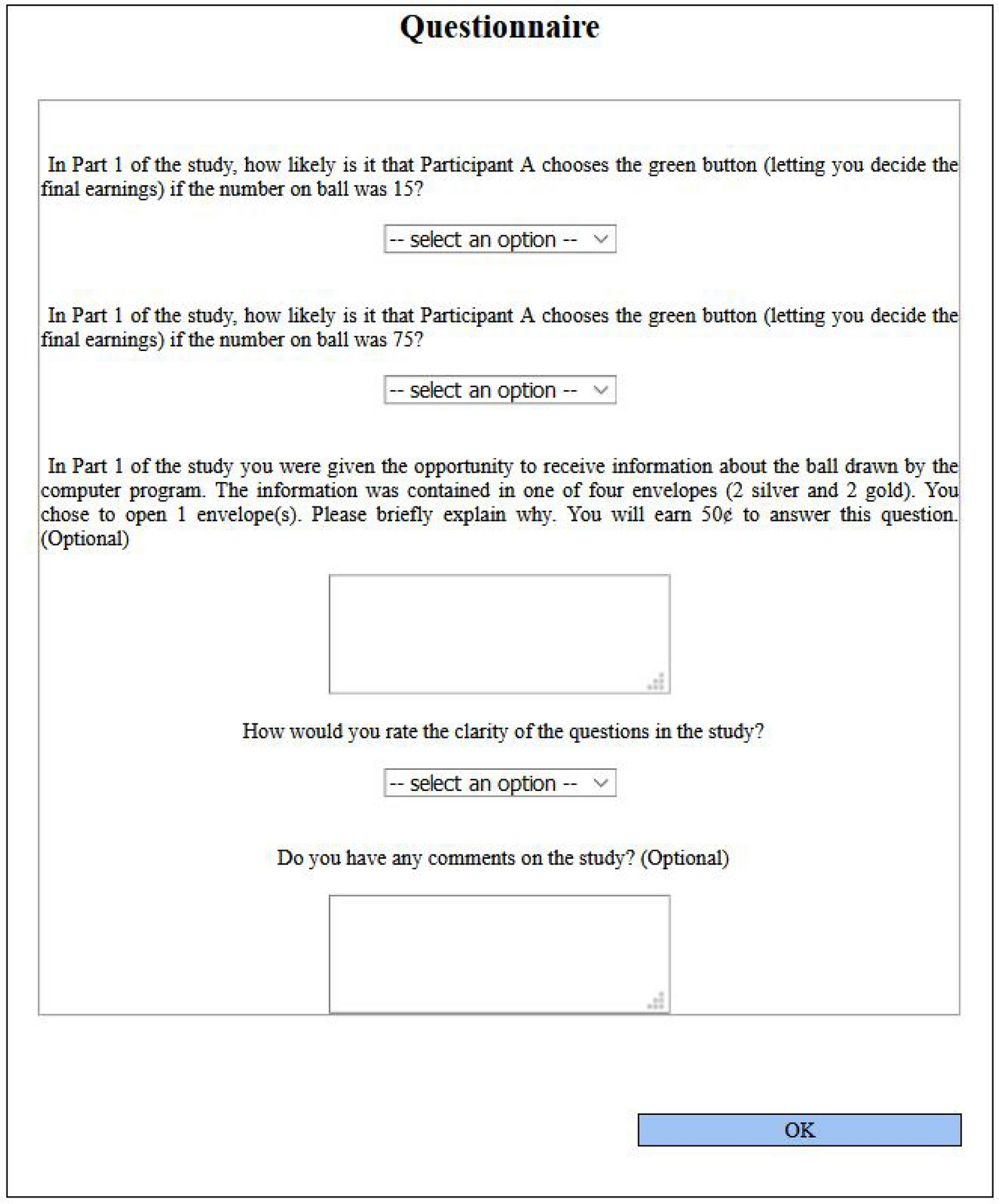

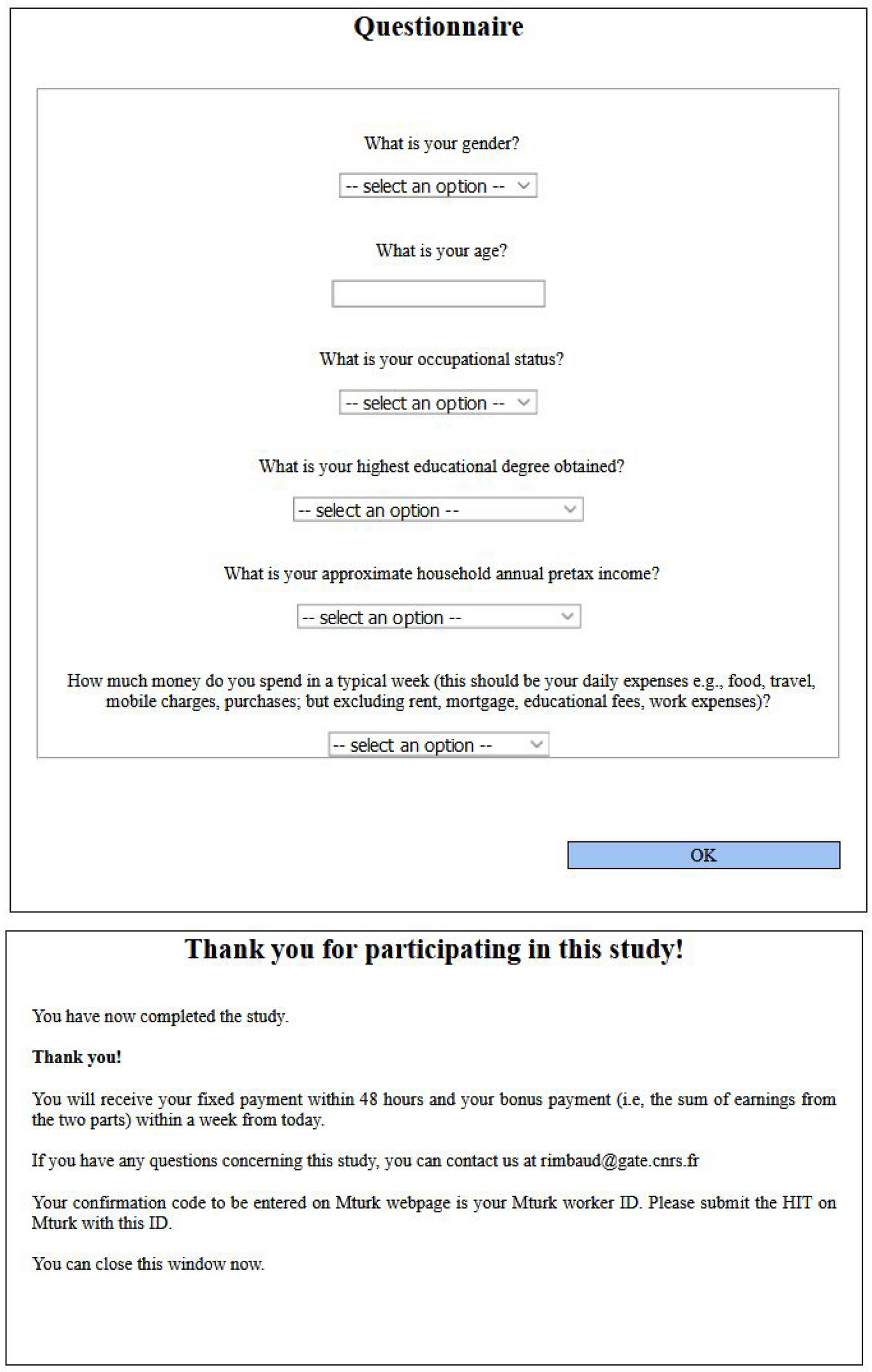

Post-experimental questionnaires. Because our results rely on trustees’ ability to infer their trustor’s expectations from their trustor’s potential outside options, participants’ level of reasoning may affect their responsiveness to our treatment manipulation. Therefore, we elicit participants’ level of reasoning using a 2/3 beauty-contest game in which participants are asked to indicate a number between 0 and 100, and are rewarded with 100 cents if the number they indicate corresponds to two-thirds of the mean of the numbers indicated by all participants enrolled in the experiment. Participants were also asked to report their age, gender, employment status, annual income, and weekly expenditure. Finally, we asked participants to rate the clarity of the instructions using a scale from ‘extremely unclear’ to ‘extremely clear’. In addition, we asked trustees to explain their information acquisition decision in a free-form format, and participants were rewarded 50 cents to provide an answer.

3.2 Experimental strategy

Our experimental strategy relies on two conditions: First, we must be able to observe the signal choices of trustees with belief-dependent preferences. Second, a coarse-grained rule for conditional return under uncertainty must be induced successfully. In this section, we explain our use of the ‘menu method’ to classify trustees according to their preference type and our method to create or reinforce a coarse-grained mapping of beliefs into return decisions.

‘Menu’ Method. To classify trustees as either belief-dependent or belief-independent, we need to identify whether trustees’ return decision varies with the trustor’s expectations at the individual level. Consequently, we cannot rely on a between-subject design to address our main research question. Instead, we use a variant of the strategy method (the ‘menu method’) which allows us to separate trustees with incentives to strategically acquire information and trustees without.Footnote 20

Coarse-grained mapping. The restriction of the trustees’ action space under uncertainty allows us to implement the theoretical assumption of a coarse-grained mapping of belief into action. With the amount of uncertainty fixed externally, trustees cannot adjust their return decision as a response to a change in their belief about the trustor’s expectations in a linear fashion. Theoretically, the amount returned under uncertainty,

![]() , can take any value between

, can take any value between

![]() and

and

![]() . We chose to impose

. We chose to impose

![]() as it corresponds to the amount that a trustee ex-ante expects to return (given that each state is ex-ante equally likely), and it has the advantage that it can be easily explained to the participants without having to introduce probabilities. It also ensures that the monetary incentives of acquiring either signal are the same in absolute terms for all trustees.

as it corresponds to the amount that a trustee ex-ante expects to return (given that each state is ex-ante equally likely), and it has the advantage that it can be easily explained to the participants without having to introduce probabilities. It also ensures that the monetary incentives of acquiring either signal are the same in absolute terms for all trustees.

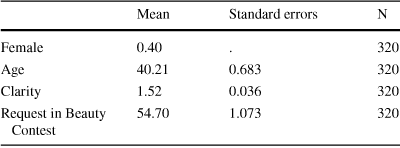

Procedures. We conducted the experiment online on Amazon MTurk. We recruited a total of 320 participants from the United States of America.Footnote 21 Participation was restricted to individuals over 18 years old who completed at least 300 HITs with an approval rate of at least 99%. Participants were randomly allocated the role of trustor or trustee at the beginning of the experiment. Pairs were formed after all participants had completed the experiment. During the experiment, participants could re-read the instructions at any time by clicking on a reminder button at the top of their screen.Footnote 22 Moreover, they had to answer a comprehension questionnaire correctly after the presentation of the instructions to proceed to the next step. Participants were paid less than 48 h after the completion of the experiment.

4 Experimental hypotheses

Our main research question is to assess whether individuals who exhibit belief-dependent preferences acquire information in a self-serving way. We address this question in two steps. First, we classify trustees as either belief-dependent or belief-independent.Footnote 23 Second, we test whether the information acquisition strategy of trustees we identified as either belief-concordant or belief-discordant differs from the information acquisition strategy of trustees we identified as belief-independent.

In Sect. 2, we assume that a higher trustor’s outside option increases both trustors’ first-order beliefs and trustees’ second-order belief about the trustor’s payoff from choosing In. This assumption can hold in theory under certain conditions (see Sect. 2.1) but empirically it remains to be tested.

Auxiliary Hypothesis 1

Conditional on choosing In, trustors’ first-order beliefs and trustees’ second-order beliefs increase with the trustor’s outside option.

If Auxiliary Hypothesis Footnote 1 is verified, we can classify trustees based on the correlation between their beliefs about the trustor’s expectations and their conditional return decisions. Following Dufwenberg et al. (Reference Dufwenberg, Gächter and Hennig-Schmidt2011), we classify trustees with a positive correlation profile as ‘belief-concordant’ (i.e., return increases with beliefs about the trustor’s expectations) and trustees with a negative correlation profile as ‘belief-discordant’ (i.e., return decreases with beliefs about the trustor’s expectations). Finally, we classify trustees as belief-independent if their conditional return decisions are the same irrespective of their beliefs about the trustor’s expectations. This leads to our second auxiliary hypothesis.

Auxiliary Hypothesis 2

The proportion of trustees identified as having belief-dependent preferences is strictly positive.

Our main research question is to identify whether trustees who exhibit belief-dependent preferences acquire information in a self-serving way. Opening both a silver and a gold envelope maximizes a trustee’s chances to learn the trustor’s actual outside option. However, some trustees with subjective preferences might be tempted to bias their information acquisition strategy towards signals that minimize the tension between their monetary incentives and their other-regarding motives. A subjective belief-concordant trustee keeps more money for himself when the trustor’s outside option is Low. Consequently, a subjective belief-concordant trustee should open the silver envelope only as doing so allows him to learn that the trustor’s outside option is Low if it is actually Low, while avoiding learning that the trustor’s outside option is High if it is actually High. Symmetrically, an expectation-based reciprocal trustee keeps more money for himself when the trustor’s outside option is High. Therefore, a subjective belief-discordant trustee should only open a gold envelope as doing so allows him to learn that trustor’s outside option is High if it is actually High, while avoiding learning that the trustor’s outside option is Low if it is actually Low. Finally, belief-independent trustees have no incentive to systematically favor one information source over the other (as information is payoff-irrelevant to them). Therefore, they provide a reasonable benchmark for comparing the information acquisition strategy of belief-dependent trustees. This leads to our two main hypotheses.

Hypothesis 1

belief-concordant trustees are more likely to open the silver envelope only compared to belief-independent trustees.

Hypothesis 2

belief-discordant trustees are more likely to open the gold envelope only compared to belief-independent trustees.

These hypotheses were pre-registered on AsPredicted.Footnote 24

5 Experimental results

In this section, we first evaluate whether beliefs are affected by the outside option manipulation. We then classify trustees according to their type of preferences: belief-concordant, belief-discordant, or belief-independent. Finally, we assess how trustees’ preferences affect their information acquisition strategy.

5.1 Are beliefs affected by the outside option manipulation?

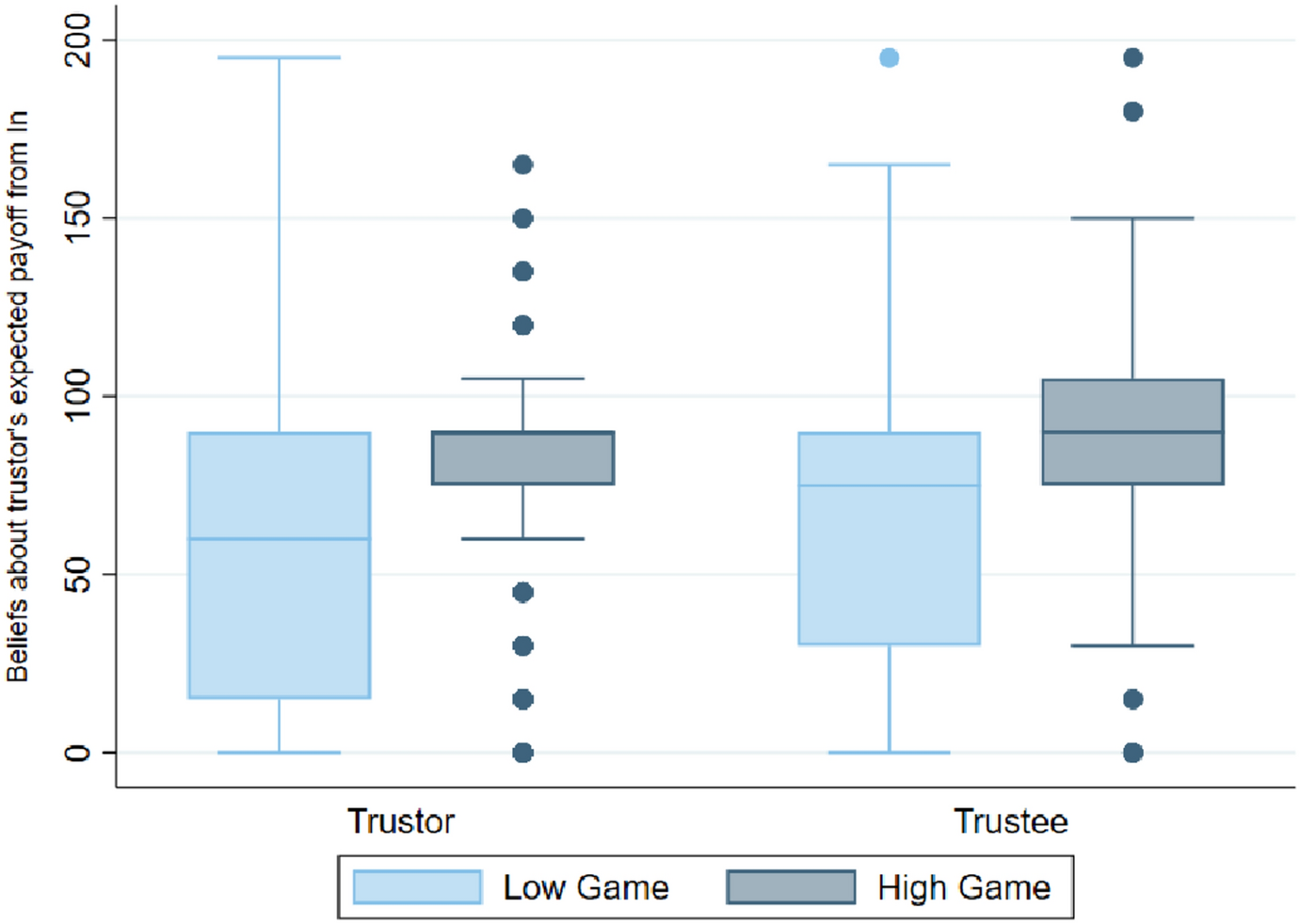

In this section, we assess whether Auxiliary Hypothesis Footnote 1 is verified, that is, whether trustors’ first-order beliefs and trustees’ second-order beliefs about trustors’ payoff from choosing In are higher in the High game than in the Low game.

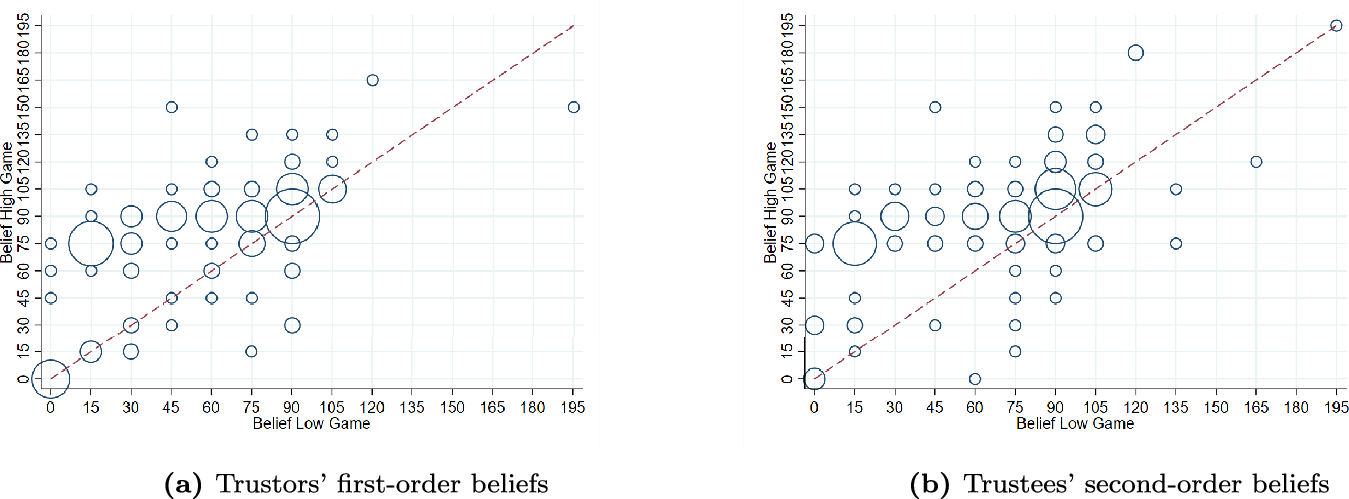

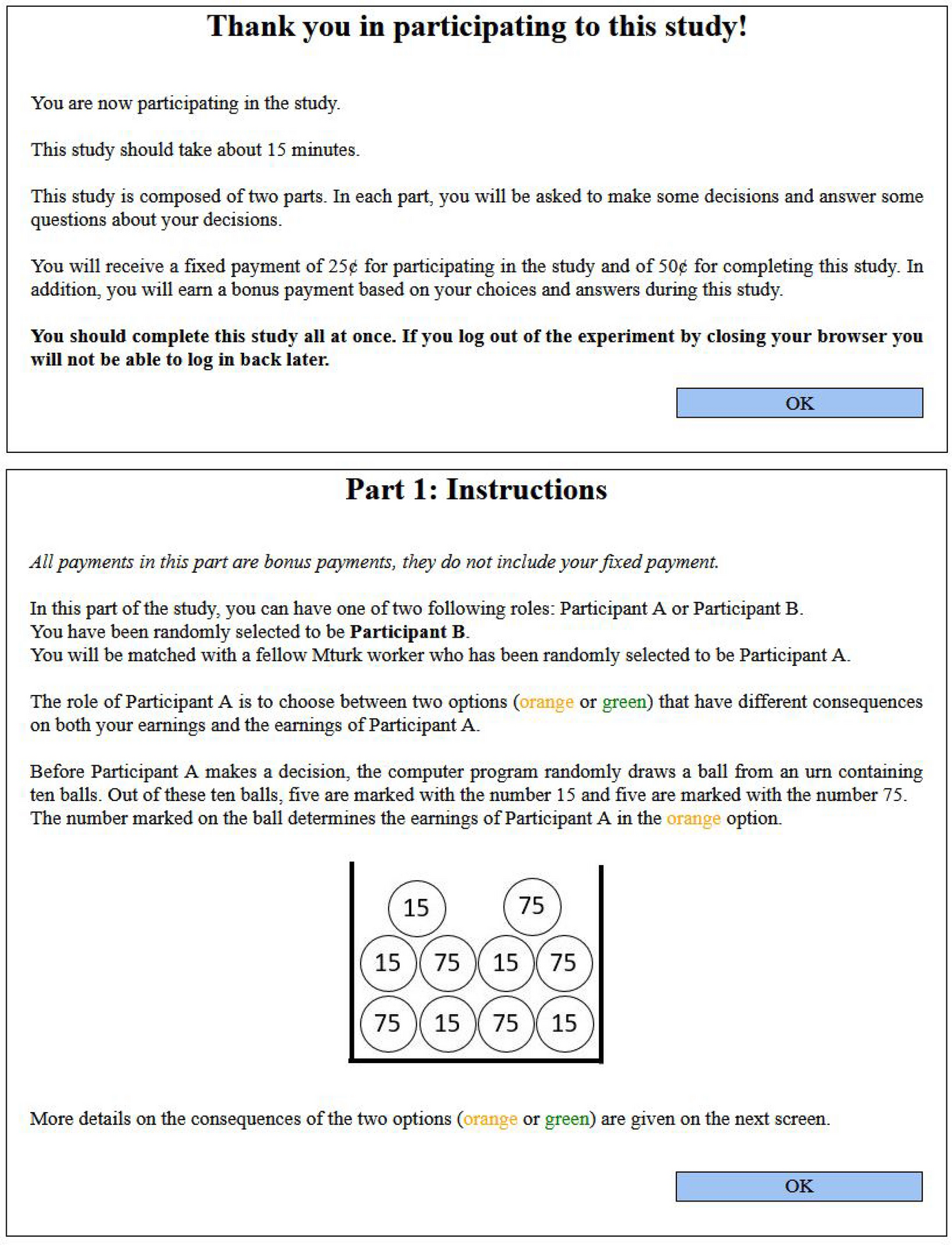

Figure 3 displays the combination of beliefs about trustors’ expected payoffs from choosing In in the Low game (x-axis) and in the High game (y-axis). The left panel displays trustors’ beliefs, while the right panel displays trustees’ beliefs. Figure 3 shows that there is a lot of heterogeneity in participants’ responsiveness to the outside option manipulation.

Fig. 3 Distribution of individual beliefs about trustors’ expected payoff from In

The majority of participants’ beliefs verify Auxiliary Hypothesis Footnote 1. We find that 53.13% of trustors, and 61.25% of trustees held higher beliefs in the High game than in the Low game (i.e., observations above the 45-degree line). In contrast, 10% of trustors and 8.13% of trustees indicated higher beliefs in the Low game than the high Game (i.e., observations below the 45-degree line), and 28.75% of trustors and 38.75% of trustees indicated similar expectations regardless of the game being played (i.e., observations on the 45-degree line). Interestingly, there seems to be a strong focal point around the egalitarian allocation, with 50% of the participants holding undifferentiated beliefs indicating beliefs at 90 cents in both games. To test our theoretical predictions, the subsequent analyses focus on the sub-sample of trustees who satisfied Auxiliary Hypothesis Footnote 1.

Result 1

53.13% of trustors’ first-order beliefs and 61.25% of trustees’ second-order beliefs are higher when the outside option is High rather than Low.

5.2 Are trustees motivated by belief-dependent preferences?

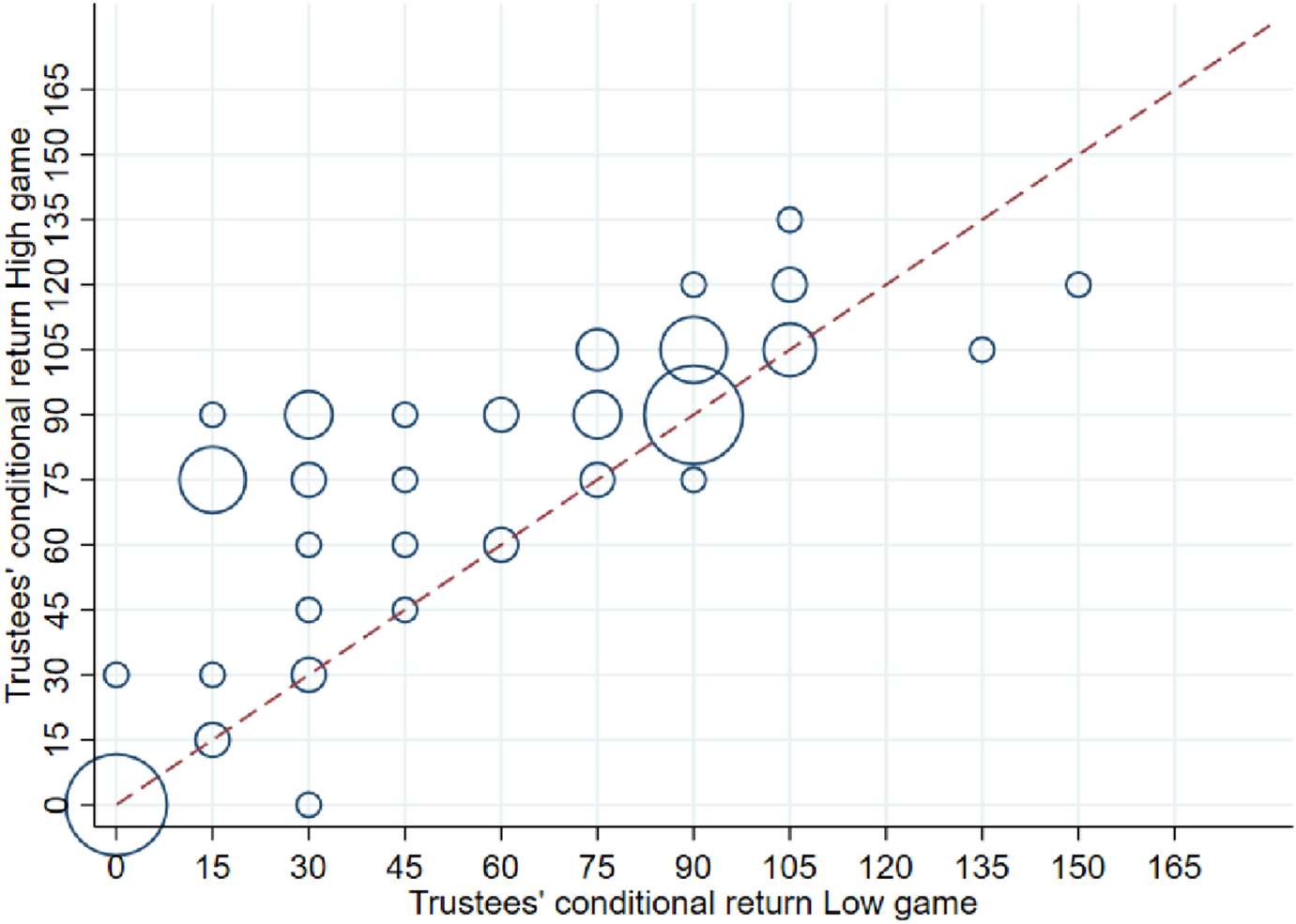

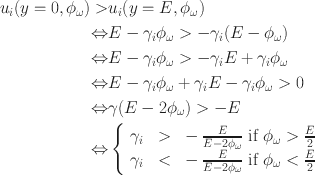

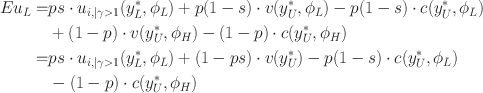

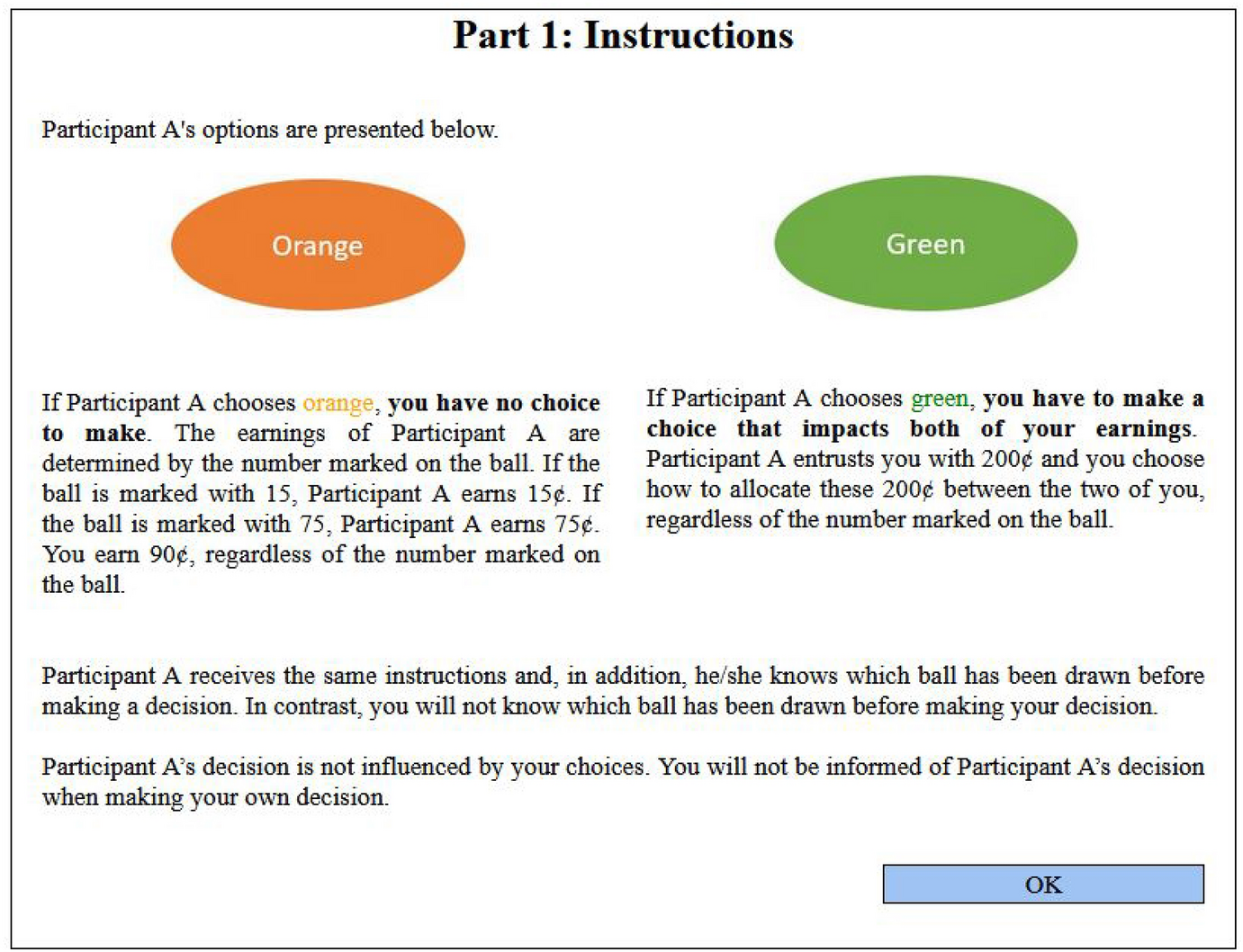

In this section, we classify trustees who satisfy Auxiliary Hypothesis Footnote 1 as belief-concordant, belief-discordant or belief-independent based on their conditional transfers. Figure 4 displays the combinations of trustees’ returns in the Low game (x-axis) and the High game (y-axis). We classify trustees who returned more in the High than in the Low game as belief-concordant (i.e., observations above the 45-degree line) and trustees who returned more in the Low than in the High game as belief-discordant (i.e., observations below the 45-degree line). Finally, trustees who returned the same amount regardless of the game are classified as belief-independent (i.e., observations on the 45-degree line).

Fig. 4 Trustees’ return strategies

About half of the trustees can be classified as belief-independent (52.04%, n = 51), returning on average 50.00 cents (se = 6.14). This average return hides two focal points where the trustees’ payoff is maximized (returning 0 cents), and where equality is maximized (returning 90 cents). We found that 43.88% (n = 43) of trustees can be classified as belief-concordant. The average amount returned by belief-concordant trustees is 87.91 cents (se = 3.37) in the High game and 53.37 cents (se = 5.02) in the Low game. Only 4 trustees can be classified as belief-concordant.Footnote 25

Result 2

There is a positive proportion of trustees exhibiting belief-dependent preferences in our sample: 43.88% of trustees can be classified as belief-concordant and 4.08% of trustees can be classified as belief-discordant.

5.3 How do belief-based preferences affect information acquisition?

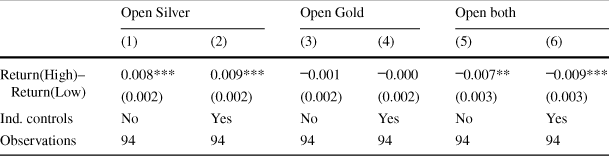

We now examine whether belief-independent and belief-dependent trustees adopt different information acquisition strategies. Given that only four trustees can be classified as belief-discordant, we restrict our analysis of information acquisition to trustees that were classified as either belief-independent or belief-concordant.

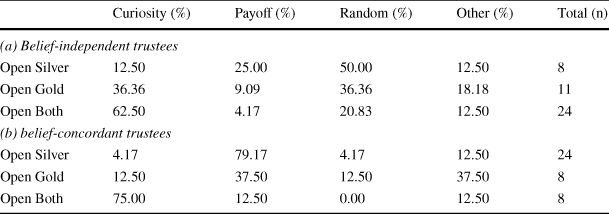

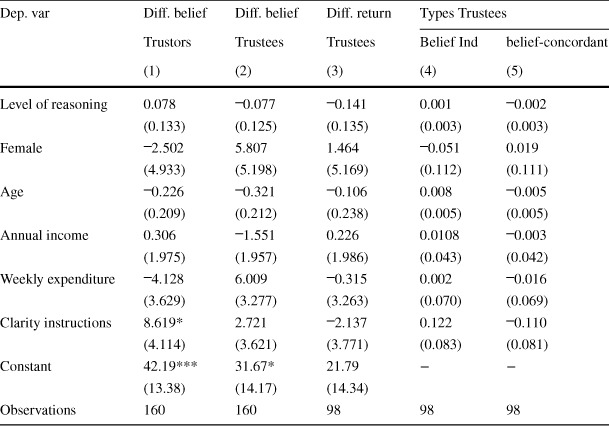

Figure 5 displays the distribution of information acquisition strategies for belief-independent (left-hand side) and belief-concordant trustees (right-hand side). It shows that the majority of belief-independent trustees chose to open both envelopes (52.94%), and they did so significantly more frequently than they would by chance (binomial test,

![]() ,

,

![]() ). We found that 17.65% of belief-independent trustees opened a silver envelope only, and 29.41% opened a gold envelope only. These results suggest that the default choice in the absence of strategic concerns is to acquire as much information as possible.Footnote 26 The post-experimental questionnaire allows us to investigate potential explanations for the trustees’ information acquisition strategy. It revealed that 75% of belief-independent trustees who chose to open both envelopes indicated that they did so out of curiosity.Footnote 27

). We found that 17.65% of belief-independent trustees opened a silver envelope only, and 29.41% opened a gold envelope only. These results suggest that the default choice in the absence of strategic concerns is to acquire as much information as possible.Footnote 26 The post-experimental questionnaire allows us to investigate potential explanations for the trustees’ information acquisition strategy. It revealed that 75% of belief-independent trustees who chose to open both envelopes indicated that they did so out of curiosity.Footnote 27

Fig. 5 Distribution of information acquisition strategies for belief-independent and belief-concordant trustees

In contrast to belief-independent trustees, the majority of belief-concordant trustees chose to open a silver envelope only (60.47%), and they did so significantly more frequently than they would by chance (binomial test,

![]() ,

,

![]() ). In addition, the proportion of belief-concordant trustees who chose to open a silver envelope only is significantly higher than the proportion of belief-independent trustees who made the same choice (Pearson’s chi-square test,

). In addition, the proportion of belief-concordant trustees who chose to open a silver envelope only is significantly higher than the proportion of belief-independent trustees who made the same choice (Pearson’s chi-square test,

![]() ). The results of multinomial logit regressions reported in Table 4 in the Appendix corroborate these findings. Altogether, these observations suggest that the majority of belief-concordant trustees exhibit an information acquisition strategy consistent with subjective preferences. Moreover, such strategy is indeed self-serving, as trustors receive significantly less in expectations (two-sided t-test:

). The results of multinomial logit regressions reported in Table 4 in the Appendix corroborate these findings. Altogether, these observations suggest that the majority of belief-concordant trustees exhibit an information acquisition strategy consistent with subjective preferences. Moreover, such strategy is indeed self-serving, as trustors receive significantly less in expectations (two-sided t-test:

![]() ) when matched with a belief-concordant trustee who chooses to open the silver envelope only (66.32,

) when matched with a belief-concordant trustee who chooses to open the silver envelope only (66.32,

![]() ) than with a belief-concordant trustee who chooses to open both envelopes (70.64,

) than with a belief-concordant trustee who chooses to open both envelopes (70.64,

![]() ).

).

Result 3

belief-concordant trustees are more likely to open only the silver envelope compared to belief-independent trustees.

Although our model is agnostic on the relative proportions of the different information acquisition strategies, it is noteworthy that 20.93% of belief-concordant trustees chose to open both envelopes, which is consistent with our prediction for objective preferences. In contrast 18.60% of belief-concordant trustees chose to open only the gold envelope.Footnote 28 This information acquisition strategy cannot be explained by our model. We contend that it is likely due to behavioral noise. Indeed, this share goes down to 5.56% when excluding trustees who reported that (i) they did not understand that their choice of envelopes was payoff-relevant (n=6) or (ii) the instructions were not “extremely clear” (n=24) (see, Sect. C.2 in the Appendix).

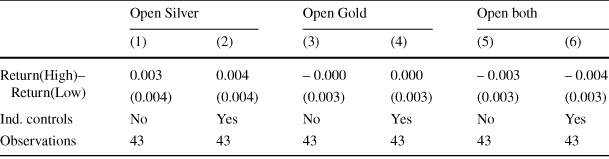

5.4 Determinants of trustees’ information acquisition

We show in Sect. 5.3 that most belief-concordant trustees exhibit an information acquisition strategy consistent with subjective preferences. Hence, one can wonder whether these trustees are the ones that benefit the most from doing so. Indeed, one can imagine that trustees with the most money to lose from learning about a specific state of the world (i.e., trustees with more differentiated return decisions) are the most likely to engage in self-serving information acquisition strategies.

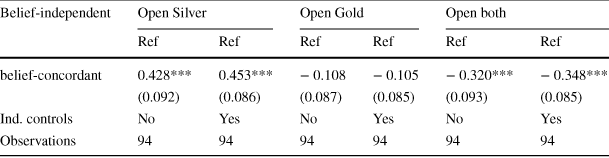

To address this question, we estimate multinomial logit models in which the dependent variable is a categorical variable that summarizes the three possible information acquisition strategies. The main explanatory variable corresponds to the difference between the amount returned by a belief-concordant trustee when he/she learns that the trustor’s outside option is high and the amount returned when he/she learns that the trustor’s outside option is low. The average marginal effects (AME) are displayed in Table 1.

Results from columns (1) and (2) show that a 10-cent increase in the difference in conditional returns leads to a 3% increase in the likelihood to open the silver envelope only.Footnote 29 However, the results are not significant. This null result goes against the idea that trustees with the most money to lose from learning about a specific state of the world are the most likely to engage in self-serving information acquisition strategies.

Table 1 Average marginal effects of monetary incentives on the likelihood of each sampling strategy

|

Open Silver |

Open Gold |

Open both |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

(1) |

(2) |

(3) |

(4) |

(5) |

(6) |

|

|

Return(High)–Return(Low) |

0.003 |

0.004 |

– 0.000 |

0.000 |

– 0.003 |

– 0.004 |

|

(0.004) |

(0.004) |

(0.003) |

(0.003) |

(0.003) |

(0.003) |

|

|

Ind. controls |

No |

Yes |

No |

Yes |

No |

Yes |

|

Observations |

43 |

43 |

43 |

43 |

43 |

43 |

Table reports the average marginal effects of our multinomial logit model of the difference in conditional returns on the likelihood of a given sampling strategy. Controls include the amount guessed in the beauty contest game and socio-demographic characteristics (age, identifying as a female, annual income, weekly expenditure). The sample is restricted to belief-concordant trustees only. Standard errors are in parentheses

*

![]() , **

, **

![]() , ***

, ***

![]()

6 Discussion

We now examine the robustness of our findings in light of our choices regarding the identification strategy, design, and procedures. We discuss potential concerns and report additional analyses from our main experiment, as well as results from a follow-up experiment in an attempt to mitigate them.

Identification strategy. To classify trustees as either belief-dependent or belief-independent, we rely on the assumption that the change in the trustor’s outside options affects the trustee’s decision only indirectly via his beliefs. However, it is possible that our manipulation of the trustor’s outside option directly affects trustees’ behavior. For instance, trustees may care about the sacrifice the trustor makes by choosing In and derive utility from rewarding this sacrifice independently of the trustor’s expectations.Footnote 30 Trustees with such preferences would return more when the outside option is High for reasons that are unrelated to their second-order beliefs. To disentangle these two channels, we turn to trustees who reported the same beliefs regardless of the trustor’s outside option, as these trustees’ return decisions cannot be driven by their beliefs. Comparing the behavior of such trustees to the behavior of trustees who reported higher second-order beliefs in the High game, we find no suggestive evidence in our data for this alternative channel. Indeed, among trustees who reported no difference in their second-order beliefs, 15% returned more when the outside option was higher (i.e., higher sacrifice) while this percentage rises to 44% among trustees who reported higher second-order beliefs when the outside option was higher. This finding reinforces our confidence in the validity of the main assumption underlying our identification strategy.

Experimenter demand effect. While the menu method has been widely used to elicit belief-dependent preferences in the literature (e.g., Khalmetski, Reference Khalmetski2016; Hauge, Reference Hauge2016; Bellemare et al., Reference Bellemare, Sebald and Suetens2017; Bellemare et al., Reference Bellemare, Sebald and Suetens2018), one might be concerned that the use of the strategy method might induce an experimenter demand effect (Zizzo, Reference Zizzo2010).Footnote 31 Because both decisions are elicited on the same screen, participants may feel compelled to provide a different answer for each elicitation, which may not reflect their true preferences. If this is the case, we may be overestimating the role that belief-dependent preferences play in explaining participants’ information acquisition strategy. We believe that demand effects should be limited in our context. Indeed, Bellemare et al. (Reference Bellemare, Sebald and Suetens2017) compare how different elicitation methods affect participants’ responses in the trust game and found that the ‘menu’ method yields results similar to the “baseline” approach. In addition, the sizeable share of participants exhibiting belief-independent preferences also suggests that participants did not feel compelled to condition their return decisions on the trustor’s outside option.

Nevertheless, we attempted to mitigate this concern by conducting a follow-up experiment similar to the original experiment described in Sect. 3 to the exception of three important changes (see the new decisions screens in Sect. D.3). First, we elicited trustees’ transfer decisions conditional on the trustor’s outside option being low and conditional on the trustor’s outside option being high on two separate screens, and the order of the decisions screens was randomized at the participant level. Second, we did not remind trustees about how much money the trustor would give up by choosing In based on the trustor’s outside option to make the trustors’ expectations less salient. Finally, we did not remind trustees of their beliefs about the trustor’s expectations to avoid priming participants into thinking that their beliefs about the trustor’s expectations should matter.Footnote 32 We conducted the follow-up experiment on Amazon MTurk where we recruited 320 participants using the same procedure as in the original experiment. The results of the follow-up experiment are consistent with the results from the main experiment. Notably, we found that the share of participants conditioning the amount of money to return to the trustor on the trustor’s outside option was much higher in the follow-up experiment than in the original one (65.93% vs. 43.88%). If anything, it seems that eliciting decisions on the same screen leads to more consistency between responses (which goes against the experimenter demand effect) than eliciting decisions on different screens.

MTurk sample. A concerned reader might be worried that our experimental setup is too complicated for an online implementation. We argue that this is unlikely to drive the data for several reasons. First, experiments involving beliefs elicitations and information processing have been successfully conducted on MTurk.Footnote 33 Nevertheless, to address this concern further, we replicated our analyses on a (pre-registered) sub-sample of participants from which we excluded participants who indicated in the post-experimental questionnaire that (i) the instructions were not extremely clear or that (ii) they had trouble understanding the instructions. These analyses are reported in the Appendix Sect. C.2 and show that our main findings are robust—and sometimes stronger—in the restricted sample.

7 Conclusion

Other-regarding preferences are prevalent in most human societies. However, the robustness of these preferences tends to be challenged in the presence of uncertainty in the decision environment. For instance, individuals with outcome-based preferences have been shown to exploit uncertainty about the relationship between their actions and outcomes to behave more selfishly. In contrast, the literature on belief-dependent preferences has focused on situations where the uncertainty about others’ expectations is automatically resolved when the action is implemented. Hence, one can wonder whether individuals with belief-based preferences strategically acquire information about other’s expectations to minimize the tension between their monetary incentives and their other-regarding preferences.

To address this question, we adapted the information acquisition model proposed by Spiekermann and Weiss (Reference Spiekermann and Weiss2016) to study whether agents with belief-dependent preferences strategically acquire information about others’ expectations. Our model predicts that agents with objective belief-dependent preferences always prefer more information, while agents with subjective belief-dependent preferences strategically seek information that minimizes the tension between their monetary interest and their other-regarding preferences. We then tested our predictions in an online experiment. We designed a modified trust game in which we manipulate trustees’ beliefs about trustors’ expectations by varying trustors’ outside options. We then elicited trustees’ preferences by asking them to report their return choices conditionally on the trustors’ outside option. Finally, trustees were given the opportunity to acquire information about the trustors’ outside option.

We found that 60.47% of trustees classified as belief-dependent engaged in self-serving information acquisition by choosing to acquire only the signal that was congruent with their monetary incentives, which is consistent with our theoretical predictions for subjective preferences. These findings suggest that previous research may have captured an upper bound of the positive impact of belief-dependent preferences on pro-social behavior. Interestingly, we found no evidence that the individuals with the most to gain from engaging in self-serving information acquisition (i.e., the ones with the most differentiated return decisions) were the most likely to do so. Finally, it is worth mentioning that a non-trivial fraction of our sample acquired information in a pattern consistent with objective belief-dependent preferences (20.93%).

Our findings underline the challenge of designing effective information policies to promote pro-sociality. We show that nudging belief-dependent individuals toward pro-social choices requires that information on others’ expectations is attended to. When information is available but not directly observable, individuals may be tempted to seek self-serving signals, leading to less pro-social behavior than one would expect when information on expectations cannot be ignored.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Giuseppe Attanasi, Laurent Denant-Boëmont, Si Chen, Christoph Vanberg, and Marie Claire Villeval for useful feedback. We thank Quentin Thevenet for his help in programming the experiment. Helpful comments were received from participants to the GATE-Lab and AWI internal seminar series, the JMA Conference in Rennes, and the Lyon-Maastricht workshop. This study has been funded by the LABEX CORTEX (ANR-11-LABX-0042) of Université de Lyon, within the program Investissements d’Avenir (ANR-11-IDEX-007) operated by the French Agence Nationale de la Recherche (ANR) and by a the Young Scholar Research Funding of the FSP EPOS (Universty of Innsbruck). Claire Rimbaud was supported by the Austrian Science Fund (FWF, SFB F63).

Appendix A Proofs of the Theory

A.1 Predictions for a belief-discordant trustee

Following the same reasoning as in Sect. 2, we investigate the information acquisition strategy of belief-dependent trustees with belief-discordant preferences under uncertainty. Let

![]() =

=

![]()

![]() be the maximum utility achievable for a belief-discordant trustee for a given expectation

be the maximum utility achievable for a belief-discordant trustee for a given expectation

![]() . In contrast with belief-concordant trustees, this function increases with

. In contrast with belief-concordant trustees, this function increases with

![]() : the higher the expectations of the trustor, the more likely it is that the trustee will return

: the higher the expectations of the trustor, the more likely it is that the trustee will return

![]() . The proof is provided in the Appendix A.2. Recalling our auxiliary assumption which states that

. The proof is provided in the Appendix A.2. Recalling our auxiliary assumption which states that

![]() , it follows that

, it follows that

![]() .

.

As in Sect. 2.2, when the trustor’s expectation is uncertain, we distinguish between objective and subjective belief-discordant trustees. An objective belief-discordant trustee must maximize the pleasure from a mismatch given by:

![]() . Hence, the information acquisition strategy that maximizes his utility is to acquire both signals, as it maximizes his chances to learn about the trustor’s actual expectation. The proof is provided in the Appendix A.4. In contrast, a subjective belief-discordant trustee maximizes his utility when he believes that the trustor’s expectation is High (recall that,

. Hence, the information acquisition strategy that maximizes his utility is to acquire both signals, as it maximizes his chances to learn about the trustor’s actual expectation. The proof is provided in the Appendix A.4. In contrast, a subjective belief-discordant trustee maximizes his utility when he believes that the trustor’s expectation is High (recall that,

![]() ). Consequently, a subjective belief-discordant trustee will only sample information from the signal

). Consequently, a subjective belief-discordant trustee will only sample information from the signal

![]() only, which provides either information congruent with this belief, or no information. The proof is provided in Appendix A.5. We summarize these results in the two following propositions.

only, which provides either information congruent with this belief, or no information. The proof is provided in Appendix A.5. We summarize these results in the two following propositions.

Proposition 4

An objective belief-discordant trustee acquires both signals.

Proposition 5

A subjective belief-discordant trustee acquires a High signal only.

To summarize, belief-discordant trustees with objective preferences will exhibit the same information acquisition strategy than belief-concordant trustees with objective preferences. In contrast, belief-discordant trustees with subjective preferences will acquire information from the High signal only while belief-concordant trustees with subjective preferences will acquire information from the Low signal only.

A.2 Proof on how to determine trustees’ optimal return

We first show that the problem has only 3 solutions:

![]() ,

,

![]() and

and

![]() .

.

Recall that

![]() . Hence,

. Hence,

We distinguish between 3 cases:

when

![]() , it is straightforward that

, it is straightforward that

![]() is maximised for

is maximised for

![]() . If

. If

![]() , the two corners solutions are

, the two corners solutions are

![]() and

and

![]() . When

. When

![]() or

or

![]() , then the solution is undetermined:

, then the solution is undetermined:

![]() .

.

We can now use comparative statics to determine how

![]() depends on

depends on

![]() and

and

![]() .

.

•

•

•

since

since

We first compare

![]() when

when

![]() and when

and when

![]() :

:

We then compare

![]() when

when

![]() and when

and when

![]() :

:

We can see that (i) when

![]() , a trustee prefers to return

, a trustee prefers to return

![]() instead of

instead of

![]() or

or

![]() , and (ii) when

, and (ii) when

![]() , a trustee prefers to return

, a trustee prefers to return

![]() instead of

instead of

![]() , and hence instead of

, and hence instead of

![]() .

.

It remains unclear what will the trustee prefer when

![]() . To derive predictions in this case, we compare

. To derive predictions in this case, we compare

![]() when

when

![]() and when

and when

![]() :

:

when

![]() , the solution is undetermined and

, the solution is undetermined and

![]() .

.

When

![]() ,

,

![]() . Hence, the inequality

. Hence, the inequality

![]() never holds. Hence, the trustee always prefer to return

never holds. Hence, the trustee always prefer to return

![]() instead of

instead of

![]() .

.

When

![]() , the inequality

, the inequality

![]() holds for some combinations of

holds for some combinations of

![]() and

and

![]() . More specifically, as

. More specifically, as

![]() increases,

increases,

![]() also decreases in

also decreases in

![]() over

over

![]() . This means that, the higher

. This means that, the higher

![]() , the more likely it is that

, the more likely it is that

![]() is above the threshold, the more likely it is that

is above the threshold, the more likely it is that

![]() , and the more likely it is that the trustee will return

, and the more likely it is that the trustee will return

![]() instead of

instead of

![]() .

.

To summarise, we can conclude that

• When

or

or

, the solution is undetermined:

, the solution is undetermined:

.

.• When

,

,

• When

,

,

• When

:

:

– If

,

,

– If

,

,

or

or

but as

but as

increases, the trustee becomes more likely to return

increases, the trustee becomes more likely to return

instead of

instead of

– If

, the solution is undetermined:

, the solution is undetermined:

A.3 Proof on the variation of

with respect to

with respect to

According to the envelope theorem, the total derivative at point

![]() is equal to the following partial derivative:

is equal to the following partial derivative:

Hence, we can conclude that

![]() and

and

![]() .

.

A.4 Proof of Proposition Footnote 2

Let v(y) represent

![]() . Let

. Let

![]() , with

, with

![]() , represent the amount that maximizes a belief-concordant trustee’s (expected) utility.

, represent the amount that maximizes a belief-concordant trustee’s (expected) utility.

When acquiring the signal is

![]() , the expected utility of a belief-concordant trustee with objective preferences is the weighted sum of the trustee’s utility when the true state is

, the expected utility of a belief-concordant trustee with objective preferences is the weighted sum of the trustee’s utility when the true state is

![]() and the trustee knows it (with probability ps), when the true state is

and the trustee knows it (with probability ps), when the true state is

![]() but the trustee does not know it (with probability

but the trustee does not know it (with probability

![]() ), and when the true state is

), and when the true state is

![]() (with probability

(with probability

![]() ).

).

Similarly, when acquiring the signal is

![]() , the expected utility of an objective belief-discordant trustee is given by the following equation.

, the expected utility of an objective belief-discordant trustee is given by the following equation.

When acquiring the signal is

![]() , the expected utility of a trustee with objective belief-dependent preferences is the weighted sum of the trustee’s utility when the true state is

, the expected utility of a trustee with objective belief-dependent preferences is the weighted sum of the trustee’s utility when the true state is

![]() and the trustee knows it (with probability

and the trustee knows it (with probability

![]() ), when the true state is

), when the true state is

![]() but the trustee does not know it (with probability

but the trustee does not know it (with probability

![]() ), and when the true state is

), and when the true state is

![]() (with probability p).

(with probability p).

Similarly, when acquiring the signal is

![]() , the expected utility of an objective belief-discordant trustee is given by the following equation.

, the expected utility of an objective belief-discordant trustee is given by the following equation.

When acquiring both signals, the expected utility of a belief-concordant trustee with objective belief-dependent preferences is the weighted sum of the trustee’s utility when the true state is

![]() and the trustee knows it (with probability ps), when the true state is

and the trustee knows it (with probability ps), when the true state is

![]() and the trustee knows it (with probability

and the trustee knows it (with probability

![]() ) when the true state is

) when the true state is

![]() but the trustee does not know it (with probability

but the trustee does not know it (with probability

![]() ), and when the true state is

), and when the true state is

![]() but the trustee does not know it (with probability

but the trustee does not know it (with probability

![]() ).

).

Similarly, when acquiring both signals, the expected utility of an objective belief-discordant trustee is given by the following equation.

We compare the expected utilities of receiving signal

![]() (

(

![]() ) to receiving both signals (

) to receiving both signals (

![]() ) for a belief-concordant trustee.

) for a belief-concordant trustee.

Eq. 11 is positive since, given

![]() , utility is maximal at

, utility is maximal at

![]() . Using the same reasoning, it yields to the following equation for subjective belief-discordant trustees.

. Using the same reasoning, it yields to the following equation for subjective belief-discordant trustees.

We compare the expected utilities of receiving signal

![]() (

(

![]() ) to receiving both signals (

) to receiving both signals (

![]() ) for a belief-concordant trustee.

) for a belief-concordant trustee.

Eq. 13 is positive since, given

![]() , utility is maximal at

, utility is maximal at

![]() . Using the same reasoning, it yields to the following equation for subjective expectation-based reciprocal trustees.

. Using the same reasoning, it yields to the following equation for subjective expectation-based reciprocal trustees.

We can conclude that taking both signals is the preferred choice for both objective belief-concordant and objective belief-discordant trustees.

A.5 Proof of Proposition Footnote 3

The expected utility of acquiring signal

![]() for a for a belief-concordant trustee with subjective preferences corresponds to the weighted sum of the trustee’s utility when the state is

for a for a belief-concordant trustee with subjective preferences corresponds to the weighted sum of the trustee’s utility when the state is