Introduction

About 6 million years ago, the Mediterranean basin was the location of one of the most extraordinary events in the recent geological history of the Earth: the so-called Messinian Salinity Crisis (MSC). MEDSALT aims to create a new flexible scientific network addressing the causes, timing, emplacement mechanisms, and consequences – at local and planetary scale – of the largest and most recent ‘salt giant’ on Earth: the Mediterranean Salt Giant (MSG). The MSG is a 1.5 km thick salt layer that was deposited on the bottom of deep Mediterranean basins about 5.5 million years ago, in late Miocene (Messinian), and is preserved beneath the deep ocean floor today. The origin of the Mediterranean salt giant is linked the Messinian Salinity Crisis. Research on the MSC has initiated one of the longest-living scientific controversies in Earth Science. Pioneering scientific drilling in 1970 induced some researchers to publish the theory of the ‘desiccation’ of the Mediterranean during the Messinian. In their view the Mediterranean Sea level dropped by 1–2 km and the basin was transformed into a huge hot, dry salt lake as a consequence of the tectonically-driven closure of the Atlantic gateway at the present-day Gibraltar strait. This interpretation was successful not only among the scientific community, but also in public opinion. On one hand, the progress of scientific research provided additional evidence for the desiccation theory. On the other hand, researchers questioned the theory, providing alternative interpretations of the geological data, and theoretical arguments supporting a model of salt deposition from a deep brine, assuming a very limited sea level change. Controversial views also exist on the mechanisms that ended the MSC: was it a catastrophic flood of Atlantic waters from the re-opening of the Atlantic gateway, or a slow mixing with brackish water from the Black Sea area first before the re-establishment of the normal marine connection with the Atlantic Ocean? In order to trigger progress on the understanding of the MSC, a widespread international scientific community has promoted the largest coordinated research on the MSC since its discovery, clustered around scientific drilling. COST (European Cooperation in Science and Technology) was identified as the most appropriate tool, as COST Actions provide tools for networking, training, mobility and dissemination. The network has further promoted one Marie Skłodowska-Curie European Training Network (SALTGIANT) offering 15 PhD fellowships across Europe. New contacts have been activated with a variety of stakeholders, including governmental administrations, non-governmental organizations, the industry and, indirectly, society at large, demonstrating the importance that science and society renew a relationship of trust and confidence. In all, 200 scientists are working together – across disciplines such as geophysics, geology, biology, microbiology, and also social sciences – towards a common scientific goal: uncovering the Mediterranean salt giant.

The Origin of the Controversy

The ‘Messinian Salinity Crisis’ (MSC) is regarded as one of the longest-living scientific controversies in the field of Earth Sciences (e.g. Roveri et al. Reference Roveri, Flecker, Krijgsman, Lofi, Lugli, Manzi, Sierro, Bertini, Camerlenghi, De Lange, Govers, Hilgen, Hubscher, Meijer and Stoica2014a). The controversy has its roots in the Apennine mountain chain of Italy, and its ribbon of gypsum-rich rocks that extends discontinuously from Piedmont to Sicily (Figure 1). The term MSC was introduced in the scientific literature by Selli (Reference Selli1960), who made the link between the Apennine gypsum deposits and what he proposed had been a major disruption of the salinity of the Mediterranean Sea during the Messinian stage of the Miocene epoch (now dated between 5.97 to 5.33 million years ago).

Figure 1. A panoramic view of the geological formation ‘Vena del Gesso’ in the vicinity of Brisighella, in the northern Apennines (Italy). The cliffs are made of 16 distinct gypsum layers with a total thickness of about 200 m interpreted as the deposition of the primary lower gypsum during the first phase of the MSC (Lugli et al., Reference Lugli, Manzi, Roveri and Schreiber2010).

Gypsum (CaSO4·2H2O) was known in Selli’s times to be a mineral formed by chemical precipitation during the evaporation of seawater. Gypsum is not, however, the only marine evaporitic mineral, because seawater contains a complex mixture of dissolved ions. Six ions make up 99% of seawater-dissolved salt: chloride (Cl–), sodium (Na+), magnesium (Mg–), sulphate (SO4–), calcium (Ca–) and potassium (K+). Together they make up the bulk of marine dissolved salt, equal to about 35 parts per thousand in weight. This means that the complete evaporation of 1 kg of seawater results in the chemical precipitation of 35 g of salts. Despite small spatial changes in the salinity of the ocean, the concentration ratio among the major dissolved ions is geographically homogeneous. This is due to the rapid mixing of ocean water masses (over about 5000 years), compared with the residence time of the major dissolved ions in the ocean (millions of years). As a result, the sequence of precipitation of minerals during the evaporation of seawater is constant: the six major ions combine to produce the precipitation of CaCO3 (calcite), which with a subsequent substitution of Ca ions by Mg may transform to CaMg(CO3)2 (dolomite), CaSO4·2H2O (gypsum), which by loss of water may transform to CaSO4 (anhydrite), NaCl (halite), and, finally, a series of additional Mg- and K-chlorides, so-called ‘bitter salts’ KCl (sylvite), KMgCl3 + 6H2O (carnallite), KMg(SO4)Cl + 3H2O (kainite).

This sequence of mineral precipitation, that is easily reproducible in the laboratory, also occurs in nature. One well-known case is that of salterns, artificial salt ponds that have served throughout human history to harvest halite salt for food conservation. In salterns, seawater is brought to evaporate in a hot and dry climate in a series of shallow artificial ponds. Calcium carbonate and gypsum precipitate first and are discarded; the residual brine is then allowed to precipitate halite, taking care that the ‘bitter salts’, which precipitate last, do not contaminate the halite harvest; the residual, highly concentrated brine is then delivered back to the open sea.

Rock salt is the other naturally occurring salt deposit. Rock salt is found underground and harvested in salt-mines. Amongst the oldest and most famous salt mines are those of Salzburg, in Austria, which were discovered by the Celts. Salt extracted from these mines was used by the Celts to preserve cod fished in the northern seas, where salt production in salterns was problematic owing to a humid climate and limited evaporation. It is this rock salt, and the attempt to explain its origin in the Mediterranean Sea that led to the emergence of the scientific controversy known as the Messinian Salinity Crisis.

The idea that rock salt forms by evaporation of seawater led Selli to interpret the gypsum deposits of the Apennines as the result of a dramatic change in the salinity of the Mediterranean Sea. His reasoning was straightforward and based on solid geological ground: gypsum, although the most abundant evaporitic mineral in the Apennines, is often accompanied by calcium carbonate, and, in a few locations in Sicily, Calabria and Tuscany, by halite. The similarity of this mineral association with the marine evaporitic sequence was striking, and pointed directly to an event of excessive evaporation of the Mediterranean Sea. The large gypsum sequences now outcropping on land had been deposited underwater in what were interpreted as shallow marine environments lying at the periphery of the deep Mediterranean Basin. But the trigger for the exceptional salinity increase was unknown and the exploration of the 4000 m deep Mediterranean marine realm was in its infancy – the MSC controversy was yet to come.

Salt Giants

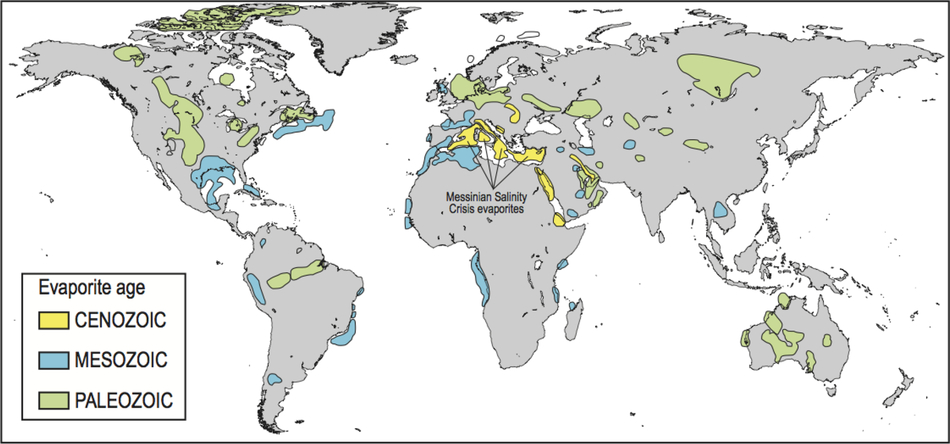

Before looking at how the MSC controversy unfolded, it is important to understand the concept of ‘Salt Giants’. Giant, halite-dominated salt accumulations are common on Earth (Figure 2); they have horizontal dimensions spanning from hundreds to thousands of kilometres, and kilometre-scale thickness; they are present on all continents, and below the seafloor of the Atlantic Ocean, the Mediterranean Sea, the Red Sea, the North Sea, the Baltic Sea, and even in certain areas of the Arctic Ocean. The age of salt giants spans from the Paleo-Proterozoic (about two billion years) to the Messinian stage of the late Miocene (~6.0–5.5 million years). The youngest salt giant on Earth is the Mediterranean Salt Giant.

Figure 2. Geographical and temporal distribution of salt giants (modified by J. Lofi from Warren Reference Warren2010), among which the Mediterranean evaporites MSC are conspicuously young. Saline giants are found only in the most recent 600 million years of Earth history. The initial salinity of the global ocean is inferred to have been 1.5 to 2 times the modern value. To view this figure in colour please see the online version of this journal.

Salt giants form during two stages of the evolution of oceanic basins according to the Wilson Cycle (Wilson Reference Wilson1968): during the birth of an ocean, following the continental rifting phase; and during ocean closure, when lithospheric subduction has almost entirely consumed the oceanic crust, leading to incipient collision of the two converging continents. In both cases the following conditions are met: (1) the oceanic basin is surrounded by landmasses that restrict water exchange with the global ocean through one or more narrow and shallow sills (gateways); and (2) the rate of evaporation exceeds the rate of water input by precipitation and continental runoff. Excess evaporation causes the salinity to rise in the evaporitic basin, leading to the accumulation of rock salt on the seafloor.

Salt giants are often mined for industrial purposes. Rock salt is used for highway de-icing, water softening, animal nutrition and food conservation. One additional potential use of salt giants is as storage of dangerous – nuclear or chemical – waste. This is due to the peculiar properties of halite, which has a low density (about 2.16 g cm−3) compared with the average density of host rocks, and a very low permeability to ground water. In response to long-term geological stress, creep deformation at the level of the crystal structure results in plastic deformation. With the plastic re-arrangement of its crystalline microfabric and the nearly null water content, halite has been considered as a perfect seal for dangerous waste. Salt is also an effective seal to hydrocarbon fluids (petroleum and gas): hydrocarbons migrating in salt-bearing sedimentary basins are often trapped under impermeable salt seals where they accumulate in industrially-exploitable oil and gas fields. Recently, the discovery of a giant gas reservoir capped by the Messinian salt giant in the Egyptian offshore has triggered a renewed interest in this geological formation in the Levant Basin of the Mediterranean Sea, and which is likely to affect the delicate geopolitical equilibria in the area.

However, rock salt is mobile during burial and rises though the sedimentary overburden, forming salt diapirs that can pierce the earth surface and ocean floors; salt is subject to complex gravity-gliding phenomena causing hundred-metre-thick salt layers to slide downwards from the basin margins to the deep basin floor; salt can fracture, becoming permeable to groundwater, and lose part of its sealing capacity with respect to water. Lastly, the mobility of underground salts, and their solubility in water, makes buried salt deposits a hazard: sink-holes and landslides are often associated with shallow salt deposits, both onshore and offshore.

Salt giants are an important resource – but also a potential hazard – for human activity.

From Salinity Crisis to Desiccation Theory for the Mediterranean Sea

The MSC controversy emerged in 1973, when the scientific drilling vessel Glomar Challenger (Figure 3) of the nascent Deep Sea Drilling Project (DSDP) entered the Mediterranean Sea for the first time. The scientists of this pioneering expedition found evidence that evaporitic rocks, equivalent in age and mineralogy to those described by Selli in the Apennines of Italy, were buried under hundreds of metres of sands and clay below the seafloor of the Mediterranean Sea. Three scientists – Ken Hsü, Bill Ryan and Maria Bianca Cita – proposed that the salts found in the deep Mediterranean Sea and on the Mediterranean margins had originated simultaneously by seawater evaporation, and that the sea-level of the Mediterranean Sea had lowered during the deposition of the evaporites, exposing the seafloor of the Mediterranean almost entirely (Figure 4): the theory of the Late Miocene Desiccation of the Mediterranean (Hsü et al. Reference Hsü, Ryan and Cita1973) was born.

Figure 3. The research drilling ship Glomar Challenger, with whom the Deep Sea Drilling Project (DSDP) explored the world oceans from 1968 to 1983. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:GlomarChallengerBW.JPG.

Figure 4. An artist’s vision of the desiccated Mediterranean Sea during the Late Miocene (above), and the contrasting hypothesis of a deep, non-desiccated basin (below). The two scenarios are part of the MSC controversy today. Illustration from Krijgsman et al. (Reference Krijgsman, Capella, Simon, Hilgen, Kouwenhoven, Meijer, Sierro, Tulbure, van den Berg, van der Schee and Flecker2018) modified after The First Eden: The Mediterranean World and Man by David Attenborough (Reference Attenborough1987).

There were two fundamental observations to support this theory: (1) the samples of the evaporites recovered by drilling contained ‘chicken-wire’ nodular anhydrite and algal stromatolites that needed light to exist at the time of seawater evaporation, suggesting a subaerial sabkha depositional environment (Figure 5); and (2) geological and geophysical investigations on the margins of the Mediterranean Sea had revealed the existence of very deep erosional valleys, some of which were buried by sediments, extending inland from the major river systems (Rhone, Nile, Po); similar, profound V-shaped mountain incisions now host the southern-Alps lakes Maggiore, Como, Iseo and Garda. These could have been formed only if the water level in the Mediterranean had lowered dramatically during the salinity crisis. The trigger of the MSC was identified as the partial, or complete, closure of the Miocene-time Gibraltar Strait combined with a negative hydrological balance of the Mediterranean–Black Sea hydrographic basin.

Figure 5. Micro-photograph of algal stromatolites identified during a petrographic study of the evaporite rocks in cores obtained from DSDP Sites 124, 132, and 134 suggesting that these rocks originated in a subaerial sabkha environment (Friedman, DSDP Leg 13 Initial Reports, 22, 1973). Photo Courtesy: Bill Ryan, ECORD Magellan Plus Workshop DREAM 2013, Brisighella.

The theory of the Late Miocene Desiccation of the Mediterranean Sea received worldwide attention, both by the scientific community and by the general public. It has entered the textbooks at university and high-school levels, according to some, as a paradigm. The MSC is described as an extraordinary example of how the Earth system is vulnerable to natural change, and how the interplay between natural climate change and tectonic movements can result in a huge impact on the oceanography, landscape and ecosystems of a huge region of our planet.

However, not all scientists are convinced that in order to precipitate salts at the bottom of a deep oceanic basin, that basin has to desiccate. The salinity of an oceanic basin can increase without a substantial decrease in the volume of water, until the entire water mass has become a dense brine from which salts begin to precipitate chemically (Schmalz Reference Schmalz1969). The idea of the desiccation of the Mediterranean was questioned in the literature based on several arguments (e.g. Selli et al. Reference Selli and Drooger1973, later re-proposed by Roveri et al. Reference Roveri, Bassetti and Ricci Lucchi2001; Lugli et al. Reference Lugli, Manzi, Roveri and Schreiber2015 and in many other works): the evidence for deep-water environments of deposition in rock outcrops; the interpretation of the deep incised valleys as the product of dense brines sinking and eroding the flanks of the deep Mediterranean basin; and results from paleoceanographic models that can reproduce salinity-increase in a deep water environment using the most probable climatic condition during the MSC (e.g. Bache et al. Reference Bache, Popescu, Rabineau, Gorini, Suc, Clauzon, Olivet, Rubino, Melinte-Dobrinescu, Estrada, Londeix, Armijo, Meyer, Jolivet, Jouannic, Leroux, Aslanian, Reis, Mocochain, Dumurdžanov, Zagorchev, Lesić, Tomić, Namık Çağatay, Brun, Sokoutis, Csato, Ucarkus and Çakır2012; Simon and Meijer Reference Simon and Meijer2017). These criticisms added to earlier ideas proposing that the Messinian evaporites had in fact accumulated in a shallow-basin, shallow-water system subject to continuous subsidence under the increasing load of accumulating evaporites (Nesteroff Reference Nesteroff and Drooger1973). Since its birth in 1973, the provocative idea of a deep desiccated Mediterranean has been continuously challenged by part of the scientific community.

A further important disagreement feeding the controversy regards the mechanism by which the Mediterranean Sea returned to normal open marine conditions at the transition from the Miocene to the Pliocene. From the very beginning, the proposers of the desiccation theory postulated a dramatic flooding of the Mediterranean when the Gibraltar strait re-opened. The idea of the Gibraltar ‘cataracts’ attracted the attention of the general public and the press (Figure 6), and found support from early modelling studies (Blanc Reference Blanc2002). But did a dramatic flooding of the Mediterranean basin take place if there was no substantial sea-level drawdown during the MSC? Further, there is disagreement on the origin of the waters invading the Mediterranean at the end of the MSC. The Messinian evaporites are often covered by layers of varying thickness of sand, clay and, sometimes, gravel, which contain microfossils typical of shallow-water, brackish environments. These microfossils originate from the East of the Mediterranean, from the so called ‘Paratethis basin’, that in Messinian times occupied the present-day Carpathian and Black Sea areas (e.g. Krijgsman et al. Reference Krijgsman, Stoica, Vasiliev and Popov2010). Theses sediments are referred to in the literature as ‘Lago-Mare’ (literally: Lake-Sea) and represent perhaps the biggest unknown in the whole controversy. The Lago-Mare deposits imply that after the high-salinity phase, during which the evaporites accumulated, there followed a low-salinity stage that was a prelude to the end of the crisis. The Lago-Mare sediments have also been found in the Western Mediterranean, imposing a scenario of a Mediterranean-wide low-salinity phase fed from waters spreading from the Levant Sea, or the Aegean.

Figure 6. The ‘Gibraltar Cataracts’ in the view of Guy Billout, first published in The Atlantic Monthly © 1986. Figure published with permission from the author.

More than 1800 research articles have been published about the MSC, but no consensus exists on the tectonic, climatic and hydro-geo-chemical processes that led to the deposition of the Messinian evaporites and returned the Mediterranean to normal marine conditions at the end of the salinity crisis.

The Controversy Today

Today, nearly 50 years after the beginning of the controversy, in spite of new Messinian evaporite outcrops studied on land, no new scientific drilling has taken place at sea. The MSC controversy remains unsolved. Nevertheless, substantial progress has been made in understanding selected aspects of the MSC thanks to: (1) a dramatic technological improvement of marine geophysical exploration methods and the collaboration between private hydrocarbon sector companies and public sector research institutes; (2) the development and widespread utilization of geochemical and biological proxies of the environmental conditions at the time of evaporite deposition; and (3) the development of numerical models that simulate the hydro-geo-chemical evolution of the Mediterranean basin during the MSC.

Marine geophysical exploration led to the Mediterranean-wide mapping of salt deposits, providing unprecedented information of their extent and internal structure (Figure 7). Estimates of the total volume of salts deposited during the MSC are under way. It is likely that the total amount of salts will exceed ∼1 million cubic kilometres, corresponding to more than 6% of the dissolved salt in the global ocean. We now know that the evaporitic deposits resting in the deep basins of the Mediterranean are laterally heterogeneous. While gypsum accumulated preferentially in the western Mediterranean basin, the eastern Mediterranean evaporitic succession is composed nearly exclusively of halite (e.g. Lofi Reference Lofi2018). The origin of this huge-scale chemical distillation is still unknown. Geophysical surveys have produced extraordinary images of the deep valley and canyon systems, at times resembling proper fluvial systems, at the margins of the Messinian basins offshore the Ebro River (Urgeles et al. Reference Urgeles, Camerlenghi, García-Castellanos, De Mol, Garcés, Verges, Haslam and Hardman2010), the northern Adriatic (Ghielmi et al. Reference Ghielmi, Minervini, Nini, Rogledi and Rossi2013), the Sirte Gulf (Bowman et al. Reference Bowman2012), and the Lebanon Margin (Madof et al. Reference Madof, Bertoni and Lofi2019; Figure 8). These are interpreted as the erosional incisions that developed when peri-Mediterranean rivers were rejuvenated by the fall of the Mediterranean Sea-level. Finally, improved images of the subsurface geological structure in the Ionian Sea have allowed identification of what is thought to be the mega-flood deposit that accumulated at the Sicilian sill when the Mediterranean basin was reconnected with the Atlantic Ocean at the end of the MSC (e.g. Micallef et al. Reference Micallef, Camerlenghi, Garcia-Castellanos, Otero, Gutscher, Barreca, Spatola, Facchin, Geletti, Krastel, Gross and Urlaub2018).

Figure 7. Distribution of the Messinian evaporites in the Mediterranean Basin (Lofi Reference Lofi2018) and the Paratethys (Krijgsman et al. Reference Krijgsman, Stoica, Vasiliev and Popov2010). Dots indicate ODP and DSDP drill sites. Mediterranean: Brown: undifferentiated evaporites outcropping on land; yellow: Deep basin halite Mobile Unit; green: deep basins gypsum and clastics, Upper Unit (light green is where overlying the Mobile Unit); blue: gypsum and/or clastics of various age Bedded Unit; Gray: clastics Complex Unit; Red lines: Messinan thalwegs. Paratethys: Light purple: Lower Pontian; dark purple: Middle Pontian. To view this figure in colour please see the online version of this journal.

Figure 8. Evidence from 2D and 3D seismic reflection data of the Nahr Menashe fluvial deposits deeply buried below Plio-Quaternary sediments offshore Syria, Lebanon, Israel and Cyprus in the Levant Basin. The discovery of this deposit provides evidence for drawdown during the late Miocene Messinian salinity crisis (Madof et al. Reference Madof, Bertoni and Lofi2019).

Geochemical and biological proxies – measurable parameters of sediments that inform on past environmental conditions – highlight what seems to be a complex evolution of hydrology and salinity during the MSC. The strontium isotope composition of MSC evaporites from the deep and marginal Mediterranean basins point to a substantial freshwater input during the last phases of the MSC, culminating with the Lago-Mare unit (Topper et al. Reference Topper, Flecker, Meijer and Wortel2011; Roveri et al. Reference Roveri, Flecker, Krijgsman, Lofi, Lugli, Manzi, Sierro, Bertini, Camerlenghi, De Lange, Govers, Hilgen, Hubscher, Meijer and Stoica2014a). Molecular biomarkers and their hydrogen isotope composition confirm this scenario, and suggest that the freshwater pulse originated via overspill of the Parathetys into the eastern Mediterranean (e.g. Vasiliev et al. 2017; Reference Vasiliev, Karakitsios, Bouloubassi, Agiadi, Kontakiotis, Antonarakou, Triantaphyllou, Gogou, Kafousia, de Rafélis, Zarkogiannis, Kaczmar, Parinos and Pasadakis2019). But the influence of freshwater during evaporite deposition is not limited to the final stages of the MSC. What seem to be local influxes of freshwater also characterize marginal basins of the Mediterranean during the first phase of the MSC, when extensive gypsum successions such as those of the Apennines were being deposited. Evidence comes from salinity measured in gypsum fluid inclusions (Natalicchio et al. Reference Natalicchio, Pierre, Lugli, Lowenstein, Feiner, Ferrando, Manzi, Roveri and Clari2014), and from the oxygen and hydrogen isotopes of gypsum-bound water (Evans et al. Reference Evans, Turchyn, Gazquez, Bontognali, Chapman and Hodell2015), indicating that basin salinity was at times lower that of ocean waters (35 g kg–1). The process of formation of this ‘low-salinity gypsum’ remains unknown.

In the absence of lithological samples from the deep basin, numerical modelling has proven to be a powerful tool to test ideas on the hydro-geo-chemical and geo-tectonic evolution of the Mediterranean basin during the MSC. Paleoceanographic modelling is providing support to the various MSC scenarios, demonstrating the importance played by paleo-climate, paleo-topography and the paleo-hydrological budget of the Messinian Mediterranean Basin (Simon et al. Reference Simon, Marzocchi, Flecker, Lunt, Hilgen and Meijer2017; Simon and Meijer Reference Simon and Meijer2015; Marzocchi et al. Reference Marzocchi, Flecker, Baak, van Lunt and Krijgsman2016). The geometry and evolution of the Atlantic–Mediterranean gateway have been demonstrated to be crucial to the full understanding of the precursory events that led to the onset of the salinity crisis (Flecker et al. Reference Flecker, Krijgsman, Capella, de Castro Martíns, Dmitrieva, Mayser, Marzocchi, Modestu, Ochoa, Simon, Tulbure, van den Berg, van der Schee, de Lange, Ellam, Govers, Gutjahr, Hilgen, Kouwenhoven, Lofi, Meijer, Sierro, Bachiri, Barhoun, Alami, Chacon, Flores, Gregory, Howard, Lunt, Ochoa, Pancost, Vincent and Yousfi2015). Three-dimensional restoration modelling of the Messinian paleo topography, supported by geological and geophysical data, suggests the existence of an isolated, relatively deep Messinian Basin below the present Po Plain and Northern Adriatic (Amadori et al. Reference Amadori, Garcia-Castellanos, Toscani, Sternai, Fantoni, Ghielmi and Di Giulio2018): the Messinian Mediterranean could have consisted of numerous distinct, and at times interconnected, basins, each with its own topographic and hydrologic character. Modelling of sediment erosion and flux rates at Gibraltar during the postulated Atlantic reflooding that terminated the salinity crisis has opened astonishing scenarios for a nearly instantaneous event that re-filled the entire Mediterranean (Garcia-Castellanos et al. Reference Garcia-Castellanos, Estrada, Jiménez-Munt, Gorini, Fernàndez, Vergés and De Vicente2009).

However, numerical models lack the fundamental constraints provided by the lithological, biostratigraphic and geochemical analyses of evaporites and related sediments in the deep Mediterranean basins. It is no surprise then that the hypotheses proposed with the dataset available today are continuously challenged scientifically. The deep erosional valleys at the basin margins, interpreted by the author as evidence of sea level lowering, are re-interpreted by some as the product of margin erosion by sinking brines, and therefore as subaqueous features (e.g. Roveri et al. Reference Roveri, Manzi, Bergamasco, Falcieri, Gennari, Lugli and Schreiber2014b). Erosional truncations found at the top of the salts in the Levantine basin, generally interpreted as the product of salt gravitation gliding and erosion, are interpreted as subaqueous dissolution (Gvirtzman et al. Reference Gvirtzman, Manzi, Calvo, Gavrieli, Gennari, Lugli, Reghizzi and Roveri2017). The geochemical signals pointing to substantial influence of freshwater during the deposition of gypsum in the marginal basins could have been modified by post-depositional mineral dissolution/re-precipitation processes. At present, scientists agree to state that the controversy has no solution unless new data, in particular from the deep basins, are acquired and integrated to evaluate existing – or novel – MSC scenarios.

Finally, a growing scientific discipline in relation to the MSC is considering the impact of a sea-level decrease on faunal migration, taking advantage of temporary natural land bridges caused by sea-level lowering (e.g. Mas et al. Reference Mas, Maillard, Alcover, Fornós, Bover and Torres-Roig2018).

A Deep, Salty Biosphere?

There is a biological twist to the MSC story: the Mediterranean Salt Giant might contain a deep biosphere of microbes that is phylogenetically diverse, metabolically active and characterized by exceptional longevity (Figure 9). In the past 15 years, scientific drilling has shown that microbes are present down to 2466 m below the sea floor in a diverse set of geological environments (Roussel et al. Reference Roussel, Bonavita, Querellou, Cragg, Webster, Prieur and Parkes2008; Colwell and D’Hondt Reference Colwell and D’Hondt2013; Orcutt et al. Reference Orcutt, LaRowe, Biddle, Colwell, Glazer, Reese, Kirkpatrick, Lapham, Mills, Sylvan, Wankel and Wheat2013; Inagaki et al. Reference Inagaki, Hinrichs, Kubo, Bowles, Heuer, Hong, Hoshino, Ijiri, Imachi, Ito, Kaneko, Lever, Lin, Methé, Morita, Morono, Tanikawa, Bihan, Bowden, Elvert, Glombitza, Gross, Harrington, Hori, Li, Limmer, Liu, Murayama, Ohkouchi, Ono, Park, Phillips, Prieto-Mollar, Purkey, Riedinger, Sanada, Sauvage, Snyder, Susilawati, Takano, Tasumi, Terada, Tomaru, Trembath-Reichert, Wang and Yamada2015). Although the biosphere of deeply buried salt deposits has never been studied, recent investigations suggest that microbes living in the Mediterranean Salt Giant are involved in extensive mineral transformations that both provide oxidative energy for life and are the driving force for the development of microbial diversity.

Figure 9. (a) Samples of authigenic carbonates formed via the microbial reduction of evaporitic gypsum of Miocene age (Gulf of Suez, Egypt); microbes used reduced carbon compounds in petroleum as an energy source for metabolism (Aloisi et al. Reference Aloisi, Baudrand, Lécuyer, Rouchy, Pancost, Aref and Grossi2013); this process, based also on methane and organic matter, may promote widespread microbial sulfate reduction in the MSC salt giant. (b) Microbial filaments imaged in cleavage plains of Messinian selenite (gypsum) crystals from the Monte Tondo Quarry (Vena del Gesso, Italy); based on the analysis of DNA extracted from these samples, the filaments are the remains of photosynthetic cyanobacteria living at the time of gypsum deposition (Panieri et al. Reference Panieri, Lugli, Manzi, Roveri, Schreiber and Palinska2010). (c) Cells of the halophilic alga Dunaliella trapped in a fluid inclusion of halite from the Death valley; the light green and orange colour suggest the preservation of chlorophyll and β-carotene, indicating the presence of photosynthetic organisms (Schubert et al. Reference Schubert, Lowenstein, Timofeeff and Parker2009). To view this figure in colour please see the online version of this journal.

Evidence comes from the microbiological and geochemical study of evaporitic deposits, including those outcropping on the margins of the Mediterranean. These investigations suggest that subsurface gypsum accumulations promote the development of deep biosphere communities of sulphate reducing microbes. These thrive on the reduction of gypsum and anhydrite-derived sulphate and the concomitant oxidation of reduced organic carbon compounds such as methane, petroleum and organic matter (Figure 9(a)) (Aloisi et al. Reference Aloisi, Baudrand, Lécuyer, Rouchy, Pancost, Aref and Grossi2013; Peckmann et al. Reference Peckmann, Paul and Thiel1999; Ziegenbalg et al. Reference Ziegenbalg, Birgel, Hoffmann-Sell, Pierre, Rouchy and Peckmann2012). This process has implications for sedimentary biogeochemical cycles, the souring of crude oil and the formation of the enigmatic mineral dolomite, one of the long-standing controversies in Earth Sciences.

The thickness of the Messinian evaporites and the range of chemical environments it harbours poses fundamental questions: will the interaction of several extreme environmental parameters such as temperature, salinity, pressure and chemical composition limit the ability of microbes to take advantage of such favourable thermodynamic conditions? And has such a diverse set of physical and chemical environments fostered microbial diversity, rather than phylogenetic specialization, as research into deep Mediterranean brine systems seems to indicate (Daffonchio et al. Reference Daffonchio, Borin, Brusa, Brusetti, van der Wielen, Bolhuis, Yakimov, D’Auria, Giuliano, Marty, Tamburini, McGenity, Hallsworth, Sass, Timmis, Tselepides, de Lange, Hübner, Thomson, Varnavas, Gasparoni, Gerber, Malinverno and Corselli2006)? Dwelling in up to 3 km in salt thickness, close to the known temperature limits of life and with fluids associated with carbonate, sulphate, halite and potash salts, microbes living within and around the MSC salt giant will be subject to the most exotic combinations of extremes, and are likely to have evolved into as yet unknown adaptations.

Gypsum and halite crystals contain fluid inclusions that are a micro-habitat in which microbes survive for tens of thousands, to possibly millions, of years (Figure 9(c)) (McGenity et al. Reference McGenity, Gemmell, Grant and Stan-Lotter2000; Schubert et al. Reference Schubert, Lowenstein, Timofeeff and Parker2009). This poses fundamental questions about whether cells can devote nearly all of their energy flow to somatic maintenance needs, rather than growth and reproduction, and opens new avenues of research concerning life on other planets. Fluid inclusions and the microbes they contain also inform us of the chemical and physical conditions of the sedimentary environment at the time of formation. Mediterranean gypsum of Messinian age outcropping in the Vena del Gesso (central Italy) contains what could be the most ancient known cyanobacterial RNA (Panieri et al. Reference Panieri, Lugli, Manzi, Roveri, Schreiber and Palinska2010) (Figure 9(b)), suggesting deposition of gypsum under a shallow, illuminated water column. Fossil filaments trapped in a Messinian gypsum crystals outcropping in the Tertiary Piedmont Basin (northwest Italy), on the other hand, are thought to be the remains of microbes capable of oxidising H2S (Dela Pierre et al. Reference Dela Pierre, Natalicchio, Ferrando, Giustetto, Birgel, Carnevale, Gier, Lozar, Marabello and Peckmann2015), proof of an active biogeochemical sulphur cycle at the time of gypsum deposition. These exciting questions about life in salt lie at the core of a new set of international initiatives that have the goal of solving the open controversy.

New Perspectives and the Power of Scientific Networking

After a second Deep Sea Drilling Project (DSDP) expedition had drilled the Messinian evaporites in 1975, scientific drilling operations stopped. The possibility of intersecting hydrocarbon pockets, or karstic holes, and the dissolution of the salts surrounding the drilling pipes, were considered a drilling hazard – so penetration into the evaporites was limited to 50 m. With such a drastic technological limitation, scientists did not identify scientific drilling as an opportunity to improve the knowledge on the MSC for decades.

The international scientific community decided to change this ‘stalled’ situation. During the milestone workshop ‘The Messinian Salinity Crisis from mega-deposits to microbiology’ held in Almeria, Spain in 2007 (CIESM Reference Briand2008), scientists concluded, based on the observations and data available, that the new input that will enable this change lies in samples and geophysical data to be obtained in a new phase of scientific drilling. The availability, starting from 2003, of the riser-drilling vessel, Chikyu, owned by the Japanese partner of the Integrated Ocean Drilling Project (IODP), restored the hope for change. With a riser-drilling rig, R/V Chikyu can attempt drilling into the salts that the riser-less drilling rig of the ship JOIDES Resolution was not permitted to penetrate. A couple of drilling projects were submitted to IODP for approval in the 2000s but were not considered for scheduling. Furthermore, R/V Chikyu was busy carrying out long-term drilling programmes in the Pacific Ocean, with no real opportunities to be deployed in the Mediterranean area.

More recently, a renewed push to build a global scientific network unifying the different schools of thought on the Messinian Salinity Crisis led to a road map elaborated during two workshops sponsored by ECORD, the European Consortium for Ocean Research Drilling. This initiative goes under the acronym of DREAM (Deep Sea Record of Mediterranean Messinian Events). In 2013, in Brisighella (Italy), three generations of scientists (those who participated in the discovery, those who were actively involved in research at the time, and the next generation) met to identify locations for multiple-site drilling in the Mediterranean Sea that would allow the open questions posed by the MSC to be answered. This was the start of the largest coordinated research on the Messinian Event since its discovery, clustered around ECORD and IODP. It was an honour for all of us attending the Brisighella meeting to discuss the future of MSC research together with Ken Hsü, Bill Ryan and Maria Bianca Cita (Figure 10). The participants agreed that given the complexities of the distribution of the Messinian seismic markers in the Mediterranean, and because of the differences in the paleoceanographic conditions in the Mediterranean between the Western and Eastern basins, the drilling strategy must include multiple sites covering representative locations of both Western and Eastern Mediterranean basins.

Figure 10. William B.F. Ryan, Maria Bianca Cita and Kenneth Hsü attending the ECORD Magellan Plus Workshop DREAM in Brisighella in 2013. (Credit: L. Lourens.)

In 2014, a second workshop was held in Paris to prepare the Multi-phase Drilling Project, called ‘Uncovering a Salt Giant’, which serves as an ‘umbrella’ proposal under which the scientific questions posed by the MSC are submitted to the IODP scientific review system. The umbrella approach implies the submission of additional site-specific drilling proposals addressing not only the MSC, but also salt tectonics and fluids, surface- to deep-Earth connections, and the deep biosphere. The approach identified is that of multi-platform drilling, with some sites accessible only with the drilling vessel Chikyu in riser mode, and others accessible with the riser-less JOIDES Resolution.

At the same time, the stakeholders of scientific drilling through the Mediterranean salt giant felt the need to cluster in a stable scientific network to face all the preparatory phases for the projects. COST (European Cooperation in Science and Technology, https://www.cost.eu/) was identified as the most appropriate tool, as COST Actions provide tools for networking, training, mobility and dissemination. COST Action CA15103 Uncovering the Mediterranean salt giant (MEDSALT) was launched in March 2016 and includes 20 COST Countries, eight Institutions from COST Near Neighbour Countries, Japan, and the USA. Associated to this was another network, similarly called MEDSALT, funded by the French Agence Nationale de la Recherche (ANR) with the purpose of supporting the preparation of scientific drilling proposals.

The four overarching scientific objectives of COST action MEDSALT are:

(1) to understand salt giant formation and its relationship with local, regional and global environmental change;

(2) to investigate salt dynamics and associated fluid flow quantitatively in order to assess geohazards;

(3) to understand if salt giants promote the development of metabolically active and phylogenetically diverse deep biosphere communities of microbes and viruses;

(4) to model the isostatic response of the lithosphere to extreme and rapid mass transfer and to kilometre-scale differential vertical motions of the Mediterranean margins.

The strategy behind successful scientific networking in MEDSALT is based on the following points.

Global implications of the MSC. Scientific networks should address the causes, timing, emplacement mechanisms, and consequences at local and planetary scale of the largest and most recent ‘salt giant’ on Earth.

Technological challenge. The technological developments in drilling salt and the possibility that the IODP will bring its platforms to the Mediterranean area have pushed scientific and industrial interests in Mediterranean salt and sub-salt geological environment to converge.

Projection into the deep biosphere. The rising interest in exploring microbial diversity in deep, extreme environments supports the biological exploration of the high salinity, high pressure, and high H2S environments most likely to be encountered in the deep sedimentary record of the MSC.

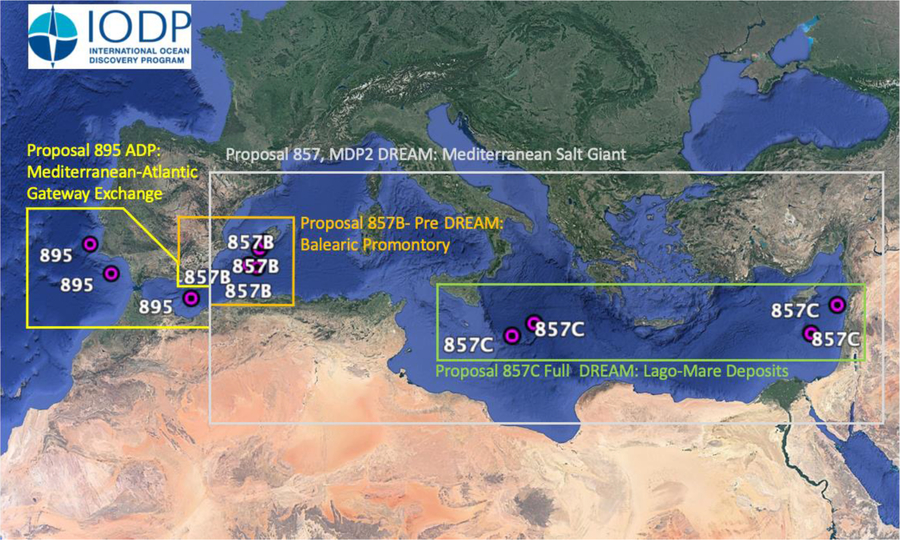

The ongoing MEDSALT scientific cooperation is largely inter-sectorial and multinational, comprising a critical mass of both experienced and early-career researchers from Europe and beyond. The goals are addressed through capacity building, researchers’ mobility, skills development, and knowledge exchange. The network today is working as an incubator of new ideas and new initiatives, and is providing a framework for the management of the drilling initiatives derived from the success of the umbrella drilling proposal. To date, there are three site-specific scientific drilling proposals under evaluation by IODP (Figure 11), with a good chance to be transformed in scientific drilling expeditions before 2023.

Figure 11. Location of the scientific drilling sites under evaluation by the International Ocean Discovery Program (IODP) for drilling before 2023. Proposal 895 (Investigating Miocene Mediterranean-Atlantic Gateway Exchange (IMMAGE)) is led by R. Flecker of the University of Bristol aiming at an amphibious drilling project (continental and offshore drilling) designed to recover a complete record of Atlantic-Mediterranean exchange from its Late Miocene inception to its current configuration. Proposal 857 (Uncovering a Salt Giant) is an Umbrella proposal of the multi-phase drilling project (MDP) led by Angelo Camerlenghi (OGS) to coordinate drilling proposals with different platforms addressing the Messinian Salinity Crisis. The following proposals have been submitted under the Umbrella proposal and aim at answering some of the still open fundamental questions related to the MSC Salt Giant: Proposal 857B (Deep-Sea Records of the Messinian Salinity Crisis) led by Johanna Lofi (University of Montpellier) aims at recovering the MSC deposits and associated deep biosphere in a series of sub-basins lying at various water depths by drilling with the JOIDES Resolution a transect of sites on the southern margin of the Balearic promontory. Proposal 857C (The demise of a salt giant: climatic-environmental transition during the terminal Messinian Salinity Crisis) led by Claudia Bertoni of the University of Oxford aims at recovering the deep basin records of the demise of the Mediterranean Salt Giant and documenting the deep biosphere and dolomite formation in the upper reaches of the Mediterranean Salt Giant.

The MEDSALT Incubator has not only produced and managed the drilling plans: it is training the next generation of scientists who will contribute to implement drilling projects. Training is taking place through the Marie Skłodowska-Curie Innovative Training Networks (ITN) ‘SALTGIANT – Understanding the Mediterranean Salt Giant’, that was launched in February 2018 (https://www.saltgiant-etn.com). SALTGIANT brings together a diverse group of researchers from Europe and beyond in order to train a new generation of outstanding scientists at the frontier between natural and social, fundamental and applied sciences, all focusing on the understanding of an exceptional natural event and to understand the far-reaching implications it has for fundamental science, industry and society. The SALTGIANT programme provides 15 PhD students with a cross-disciplinary, high-end scientific expertise, with access to state-of-the-art experimental facilities and field laboratories, and collaborations with the oil, mining and biotechnology industries that will enable them to address our ambitious research goals.

More ideas are in the MEDSALT Incubator: to expand the drilling plan to the continental realm, addressed by the International Continental Drilling Project (ICDP); to integrate the knowledge gathered on the Mediterranean Salt Giant (the youngest on Earth) to older salt giants, including the oldest on Earth (Onega Basin in Russian Karelia Paleoproterozoic era, 2.5 to 1.6 billion years ago); communicate to the different sectors of our society what are the scientific challenges in the Earth and biological sciences.

The latter is becoming an urgent need for science and society. Scientific drilling and the geophysical exploration of the Earth subsurface (whether on land or below the oceans) is too often perceived by citizens as the precursor of industrial mining and hydrocarbon extraction operations. The legitimate ambitions of society to implement a sustainable carbon-free economy with minimum impact on the natural environment sometimes generate conflicts with the ambitions of scientific research, which shares tools, investigation techniques, and scientific knowledge with the industry. All parties should make an effort to maintain an open and transparent dialogue, based on scientific knowledge, sharing of information, and mutual trust in order to guarantee the progress of science and society.

Acknowledgements

Johanna Lofi (University of Montpellier) and Wout Krijgsman (Utrecht University) revised the content and provided useful input to the final draft of this work. This contribution results from the work of two projects: COST Action CA15103 ‘Uncovering the Mediterranean Salt Giant’ (MEDSALT), supported by COST (European Cooperation in Science and Technology); and SALTGIANT, funded by the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under the Marie Skłodowska-Curie grant agreement no. 765256.

About the Authors

Angelo Camerlenghi, MS in Geological Oceanography at Texas A&M University and PhD in Earth Science at the University of Milano, is senior researcher and director of the research section of Geophysics at the National Institute of Oceanography and Applied Geophysics, in Trieste, Italy. He teaches Marine Geology at the University of Trieste. He is chairmen of the Management Committee of COST Action CA15103 ‘Uncovering the Mediterranean salt giant’ (MEDSALT) and participant in the SALTGIANT Training Network. His scientific activity is largely based on marine geophysical surveys and scientific drilling to understand the evolution of sedimentary basins and related geological hazards.

Vanni Aloisi, PhD in geochemistry at the Université Pierre et Marie Curie (Paris, France), is a senior researcher at the Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique (CNRS, France) and a research scientist at the Institut de Physique du Globe de Paris (France). He is the scientific coordinator of the European Training Network (ETN) SALTGIANT: ‘Understanding the Mediterranean Salt Giant’ and leader of the ‘Beep Biosphere’ working group of the MEDSALT COST action (CA15103). His research focuses on the use of stable isotopes of carbon, oxygen, hydrogen and sulphur to investigate low-temperature geochemical and biogeochemical processes.