1. Introduction

In 1992, with a single market in the European Community imminent, the British journal Past and Present turned its attention to the continent, noting that it ‘seemed an appropriate moment to examine how the perception of Europe had evolved and been constructed in the past’.Reference Slack and Innes1 The introduction to an excellent, if eclectic, group of articles justified its decision to break with in-house tradition and publish a single-themed issue in the following terms: ‘Aspirations towards greater European unity are in the process of creating a mental image of the continent as a single “community”, even if they have not yet created the political reality. It can safely be predicted that we will soon have several present-minded histories of that community as a coherent entity. Attempts will be made to give it a continuous, legitimizing past, as persuasive as earlier histories of Europe as Christendom or a collection of nation states.’

Past and Present's concerns proved prescient as it certainly did not take long for the EU to encourage precisely these sorts of narrative. The Maastricht Treaty 1992 (Title IX, Article 128) itself explicitly sought to ‘bring the common cultural heritage to the fore’ and the famous Nice Declaration of 2000, proclaiming the special nature of sport and its social, educational and cultural functions backed up the claim to a common European culture. Both as a participant activity and as a spectator entertainment, sport has been a central cultural feature of European economic, social and political life in the ‘long’ twentieth century – and so it is not surprising that it found itself being tracked on the common cultural radar. In 2008, the European Commission formulated a White Paper on the topic, stating stridently that: ‘[t]he European Council recognizes the importance of the values attached to sport, which are essential to European society. It stresses the need to take account of the specific characteristics of sport, over and above its economic dimension’ (Presidency Conclusions, 11/12 December 2008).

The declaration is as broad as it is bland, and as such might give historians of sport little pause for thought. But its underpinning assumptions – outlined in a White Paper and associated documents – certainly merit further consideration.2 These centre on a purported model of European sport that includes reference to East and West Europe, government and non-governmental involvement, and regulation of the media, but stresses primarily organizational models and forms of associativity. The distinctive European model supposedly rests on the coexistence of governmental and non-governmental organizations and associativity rooted in volunteers and ‘grass roots’ passions. These factors are contrasted with sport in the US and its innate connection with business. European sport, in short, is defined by underlying commonalities and its distinction from its significant ‘other’, the US.

The European Commission is investing much symbolic capital in sport's potential contribution to European harmony, the recent declaration going on to assert ‘that sport has a role in forging identity and bringing people together’. Yet such claims must be strongly qualified. Whilst sport is conspicuously present in Europe as an everyday activity, it is elusively variegated in its social and cultural forms and impacts, and historically informed scholarship points to a more sophisticated approach to an understanding of it.

Sport's major contours on the historical landscape of Europe are already familiar: the role of Britain (primarily England) as the ‘motherland’ of many popular disciplines in the nineteenth century; sport's rivalry with indigenous forms of gymnastic exercise across continental Europe; the growth of international movements such as the German Turner and the Slavic Sokol, which sought to promote nationalistic bonds via muscular strength in anticipation and hope of changing political cartographies; the global reach of British sport via the benign capillary networks of Empire; the increasing realization of physical culture's potential to enhance education, health, and social welfare; its entwinement with – i.e. contribution to and benefiting from – industrial modernization, urbanization, and governmentality at national and municipal levels; its contribution to the image and legitimacy of the incipient nation state; its ‘abuse’ under Fascist and totalitarian regimes, and continued ‘innocence’ in the liberal democracies, enshrined, not least, in the amateur ethos of the British; the emergence of the International Olympic Committee (IOC) with its quadrennial festival, as well as its rivalry with the robustly precocious but ultimately doomed Socialist Worker Sport International and the Red Sports International, themselves plunged into internecine struggle for the right to claim the left; sport's continued role as a symbolic realm for the expression and diffusion of Cold-War tensions; the gradual increase in female participation in the post-1945 period, alleviating a previously dominant masculine culture; and, finally, the irrepressible surge of commercialism in the age of accelerated globalization and mediatization.Reference Pope and Nauright3

As even this thumbnail sketch reveals, the history of modern sport can be understood – and is in fact mostly written – as a constant oscillation between contestation and harmony. The discussion of forceful ideological and socio-cultural currents dominates the field, the switches between them stark, their oppositions apparently absolute. National histories – conceived largely within national frameworks – hold sway, and there is little truly comparative work. It is the lack of such comparison that allows the European Commission to put out its statements, unchallenged, as mood music to its broader vision of integration. Yet the EU's pronouncements come at a moment when sports history has cumulatively been laying the groundwork for a more subtle – and potentially far-reaching – understanding of Europeans’ experience of sport over the last two centuries. Recent research has begun to suggest that future emphasis could be laid less on contrasts and ruptures than on commonalities and continuities.

Soviet citizens of the 1930s, for instance, indulged in the same cult of the sports star as their contemporaries in Western societies;Reference Edelman4 the sporting transition from the fledgling democracy of the Weimar Republic to the dictatorship of the Third Reich was one of evolution rather than revolution;Reference Imhoof5 international networks around the turn of the century contributed greatly to a first-phase globalization of sport on the basis of European ideas (IOC, and the football World Cup);Reference Lanfranchi, Eisenberg, Mason and Wahl6 in such contexts, even ‘Hitler's Games’ in Berlin 1936 have undergone careful revisionist assessment;Reference Young7 as has the untarnished image of British sports – previously set against the militarization and nationalistic agenda of the Fascist states but now gradually seen in the light of the UK government's own use of sport in the armed forces, its political investment in image projection at the interwar Olympics, and the sculpting of a national physique to rival the Nazis.Reference Riedi and Mason8 Our understanding of the imperial and cultural relations of other states now complements the British case, France and Germany are explored for their influencing of colonial subjects in Northern and Southern Africa as well as distant Brazil;Reference Combeau-Mari9 winter sports too, so readily portrayed as an upper-class British passion on the slopes of Alpine Europe, are now tracked out of a rich matrix of Scandinavian and Central European practices, in which the middle class had a decisive role to play;Reference Allen10 with studies of the Vuelta Ciclista a Espana and the Friedensfahrt (which captured the imagination of post-1945 Eastern Europe) complementing the plenitude of work on the Tour de France and the Giro d'Italia, cycling can now be understood, along with handball perhaps, as the sport that uniquely defines continental Europe.Reference Lopez11 Despite local differences, it has also become clear that women across Europe in the early twentieth century – from Portugal to Poland, Italy to Bulgaria, Spain, France, Britain, Scandinavia and Germany to the Soviet Union – found in physical culture and sport at least some space for freedom, self-advancement and (partial) emancipation;Reference Carpentier and Lefèvre12 migration studies – particularly in the popular game of football – portray a sense of expertise and talent in vibrant circulation, whilst – as Laurent Dubois has most eloquently portrayed for France in his reading of the Zinadine Zidane and Lilian Thuram World Cup finals of 1998 and 2006 – immigration from overseas dependencies can give a ‘national’ league a powerfully multi-ethnic texture, in which history seeps deep into the present day.Reference Lanfranchi and Taylor13

This and other recent work sheds some light on the overlapping and interlinking histories of sport in Europe that go beyond the simple binary with the United States laid out in recent EU declarations. The purpose of this article – and the six essays it introduces – is therefore twofold. It aims to enrich a general understanding of European sport and thus to inform wider debates about sport's role, past and future, in the continent of Europe. In so doing, it also seeks to galvanize the impulse and intuition of recent sports historiography and to encourage comparative work in the field. On the one hand, we would certainly agree with Past and Present's conviction back in 1992: ‘If any one conclusion emerges […], it is surely that any […] history [of a culturally unified Europe] must be myth. There exists no one “Europe”, whose history can be written in linear fashion. Its component parts have evolved along different lines. Attempts to conceptualize the totality have always been – and promise to continue to be – sources of division as much as of unity’ (p. 6). Yet, on the other, we would recast the final phrase as diversity and unity, convinced that a sensitively calibrated approach to the history of sport in Europe can uncover hidden commonalities as well as show ‘respect for the added value of diversity’ that will ‘prove to be the clue to success’ as historians are increasingly called upon to illuminate the past ‘in the ongoing movement towards European integration’.Reference Blockmans14

The papers in this collection focus primarily (although not exclusively) on the decades from the fin de siècle to the end of the 1930s, since, as recent scholarship has shown, this is a fecund period within which hegemonic sports cultures developed across the modern world and went on to dominate the sports space of societies down to the present.Reference Markovits and Hellerman15 They consider the evolution of sporting cultures in Eastern and Western Europe (concentrating on Poland, France, Italy, and Spain); the tension between differing conceptions of the body in the dance and gymnastics cultures of mid and Northern European genesis; and the representation of the sporting body in pioneering films of Europe-based summer Olympic Games in the 1920s. Specifically, the collection will enrich the sports historiography of key individual countries and at the same time, taken together, provoke debate as to how comparative work in the field might develop in the future. It relativizes textbook explanations of Britain's leading role in sport's diffusion; widens the familiar focus on Fascist sport in Italy to take in the much underestimated role of the Catholic Church; probes the porous boundaries between movement cultures; explores the role of cinema – the second, lasting mass culture activity of the twentieth century – for early conceptions of sport; and pleads for the study of regions, sub-regions and trans-national flows as a much-needed complement to the well-established literature on sporting nationalisms and their history. Much has been made of the persistence of the local within the global in addition to the influence of the global on the local (Roland Robertson's ‘glocalization’ thesis). The following essays illuminate this core dynamic, including regional configurations, within the making of modern European sport culture. This opening article will introduce them by outlining five important considerations for any future writing of the history of that culture.

2. Diversity and commonalities

Our lead phrase, diversity and unity, appears in one variation or another in most academic writing on pan-European culture. In some respects it verges, admittedly, on cliché, and it certainly provoked Felipe Fernández-Armesto recently to rail against it and argue in European Review that ‘there is no […] culture that is both general throughout Europe and unique to Europe’.Reference Fernández-Armesto16 Both these points must be considered in relation to sport.

To pick up the latter first, there is an obvious question about the extent to which a history of European sport must by definition be a history of global sport.17 Arguably, this must follow, since the sports the world plays are predominantly European in origin and the international sport system, in its culture and institutions, is a European creation. Modern sports rank among the most successful of all European cultural exports, and the global expansion of sports could most certainly be a component of the history of European sport. Equally, it is clear that the story of sport in Europe was influenced in core ways by the story of sport outside Europe. What sport meant at home, in social and cultural terms, was influenced by sport's profile in other parts of the world, either real or imagined. Certainly by the interwar period, if not before, it was the US and not Britain that was regarded as the Number One sports nation. Even the 1936 Olympic Report acknowledged this unreservedly, and a careful historical eye can detect how the effects of US influence worked their way out differently in the closest rival states of France, Britain and Weimar Germany.

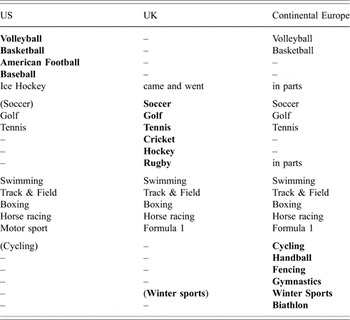

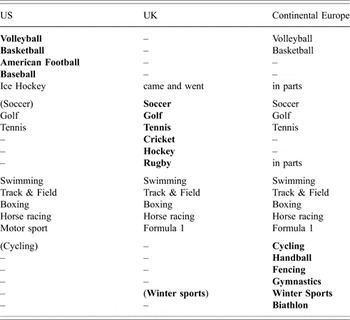

But on balance, Austrian scholar Michael Mitterauer offers the historian of European sport an escape clause in a further European Review essay that ponders the significance of European history in a global context. At first appearing to concur with Fernández-Armesto, stating that ‘[m]uch of what started in Europe has had world-wide effects’, he nonetheless concludes that ‘[t]his fact poses a dilemma only for those who seek to define Europe in the sense of demarcating it.’Reference Mitterauer18 For the results and gain of a comparative study, Mitterauer deduces, it is irrelevant whether this is conducted within Europe as a cultural area or reaches beyond it. As Mitterauer's deliberations suggest, it is counter-intuitive for the EU drastically to delimit the boundaries of European sport in the global context by imposing a strict dichotomy with the United States. Rather, an informed sports history should feel little compunction about focusing on Europe (comparative cultural histories of the continent are, after all, few and far betweenReference Sassoon19), so long as it remains alive to the permeability of the phenomenon. In fact, a brief glance at the hegemonic sports – i.e. those most played, followed and felt instinctively to belong – in the United States and Europe makes a prima facie case for a dedicated study of European sports (see Table 1). As the distinction between the United Kingdom (highlighted here because of the special status of its team sports) and continental Europe suggests, however, further differentiation will obviously prove fruitful.

Table 1 Hegemonic sports in the US, UK, and continental Europe; origins, where definitely known, in bold. Information gleaned from the standard sports history overviews

This brings us to the second of Fernández-Armesto's contentions: that there is no culture that is general throughout Europe. In direct response to this argument, Peter Burke had little difficulty conceiving the categories ‘European uniqueness’, ‘European variety’, and ‘European consciousness’ as mutually compatible, his analysis chiming to a large extent with Michael Mitterauer's. Rather than argue over the status of diversity, however, Burke emphasized the need to understand it: ‘The diversity is obvious enough; the problem is to discover how variety is structured. The question whether Europe is divided into cultural regions generally receives an affirmative answer. The problem is that scholars do not agree on the number of regions, let alone on the boundaries between them’ (emphasis added).Reference Burke20 Burke cites Hungarian medievalist Jeno Szucs's tripartite model (West, East, and East-Central Europe), Austrian geographer Hugo Hassinger's five-part scheme (which adds the centre to the four points of the compass), and the perennial chestnut of defining Central Europe as examples of the problem of mapping Europe historically, politically, and culturally. But he is flagging a need for complexity rather than waving the white flag of defeat.

Capturing how the variety of European sport is structured is no less challenging, and no less important. As an initial attempt, we offer the following cockshy. Leaving aside the continuity of folk games (such as skittles, bowls, quoits), and regionally distinct activities such as hurling (Ireland) and bullfighting, we would contend that Europe had at least four clusters of sport with varying physical forms and cultural meanings across the twentieth century: the British, the German, the Scandinavian, and the Soviet.

• The British cluster is characterized by an absence of state intervention, the reliance on private organizations and clubs, and is dominated by an anti-commercial ethos through the ideology of amateurism. British sport was a form of moral education, instilling ideals of fair-play. Although serving the needs of Empire in the nineteenth century, sport's link to militarism and the state in the twentieth century was weaker than in other comparable nations.

• The German cluster originates in nineteenth-century militarized forms of culture (Turnen) and was marked by: an emphasis on the collective, the individual body in harmony with the body politic, and a non-competitive ethos. Politically, it created differentiated effects, the common code of physical and moral practice allowing regional and particular loyalties to flourish whilst simultaneously fostering a unity of the greater German Volk. In the 1930s, Turnen and sport's innate nationalistic bent became exploited by the regime, as in several other states.

• The Scandinavian cluster is a variant of the German one. Although equally focused on improving national spirit and defence in the nineteenth century and not without rhetorical brio, which drew even on Viking traditions, in the early twentieth, it placed greater emphasis on individual movement, bodily harmony, and aesthetics. In addition, the notion of ‘idrott’ proposed a recreational outdoor ideal of physical development in harmony with nature (jogging, walking, cross-country skiing).

• In the Soviet/Eastern European cluster, sport is an extension of the state apparatus, both in spheres of mass display and the cultivation of elite athletes. It was marked by political and bureaucratic centralization, medical and scientific support, and the intensification of Cold War rivalries.

These clusters are ‘ideal types’ in the Weberian sense, i.e. characterizations of significant patterns of cultural phenomena, which contribute to the ongoing process of theory-building. Moreover, they coexisted to different degrees, in different places, at different times. The German cluster, for instance, inspired forms of gymnastics culture and physical exercise across Eastern Europe, but was not identical with them.Reference Pfister21 A term such as fizkultura was certainly resonant in Eastern Europe, but held a variety of meanings as sporting cultures developed in early-twentieth-century Russia as a precursor to the Soviet model. And as ongoing debates over the concept of ‘Norden’ in general might indicate, within Scandinavia, there were/are certainly key differences in sports culture: Denmark lacks a strong winter sport but enjoys a lively cycling culture instead; sport served in each individual country to boost nationalism; and sport's relation to the workplace – despite the famed Scandinavian welfare philosophy – was handled in ways specific to each state.Reference Kayser Nielsen22 These caveats not withstanding, however, Scandinavia can certainly lay claim to a formative role in European sport – and it is this (along with the importance of the other clusters), we simply argue, that European sports history needs clearly to acknowledge. Its Nordic Games (1901–1926) provided a model for international competition that blended tradition and modernity, and its dedication to proto-Olympic ideals (reaching back to the first half of the nineteenth century), emphasis on athletic prowess, and insistence on the separation of sport and politics made it a key player in the emerging world of international sport in the early twentieth century.Reference Jorgensen23 It is no accident that Sweden was awarded the summer Games of 1912 – an event held by many influential IOC functionaries down to the 1970s as the quintessential Olympic event; nor that in the 1930s, Finland could boast the second highest number of track and field world records.

One might ponder in this context the status of France. Here we see how the British model became increasingly dominant in the first half of the twentieth century, whilst the Scandinavian and German forms were merged together in what was seen as a distinctly French form of physical culture. Even within a liberal democratic state, the French government defined the role of this culture in schools precisely. France, therefore, could be conceivably viewed as a ‘pick and mix’ state. Alternatively, as Paul Dietschy argues in this issue, we might even be justified in seeing sport as a further example of French exceptionalism: caught at the crossroads of sporting influences, French sport is characterized by a peculiar potpourri of anglomanie, invented traditions, internationalism, state intervention and eclecticism. As the French case indicates, the choice between lumping and splitting is a natural hazard when attempting to characterize larger units of cultural and social influence. It is nonetheless still worth trying.

One final example of the possibilities and problems must suffice. One could imagine a Latin sports ‘area’, akin to the Scandinavian one perhaps, comprising Spain, Italy, France and Portugal, and consisting of a particular combination of common traits (which existed, of course, individually elsewhere) such as: the politicization of sports due to the interference of political parties and the Catholic Church; the importance of cycling culture; and the proximity of Fascist, pro-Franco, Vichy and pro-Salazar sports policies. Nevertheless, this case is also not without significant caveats: the nationalistic emphasis in France is quite different from that in Italy or Spain. At the same time, sports were tied to the Church and Communist party in non-Latin countries such as Germany and Belgium as well.Reference Munoz24 The Church played little role in sport in Spain, in contrast to Italy, as the essays on these two countries by Andrew MacFarland and Simon Martin in this issue demonstrate. Moreover, the issue of opening towards the ‘South’ also requires differentiation: if sport (particularly football) in France and Portugal was characterized by a certain racial mix due to colonialism and (partial) assimilation, this is not true of Italy or Spain.

In conclusion: the basic clusters we propose certainly contest the grand European model put forward in recent EU documents. But we have also noted complications to these clusters. It will take some sophistication to map European sport in such a way that is neither too simple or generalizing, nor so complicated that it makes no useful generalization possible.

3. Time and space

A further challenge for historians of popular culture is to do justice to these diverse patterns over time. In his reply to Fernández-Armesto, Peter Burke went on to complicate the problems of the European regions, stating that:

any attempt to divide Europe into cultural areas needs to be situated in time. Europe is what the Russian literary theorist Mikhail Bakhtin called a ‘chronotope’, in other words a space-time package […] The Renaissance helped to Italianize Europe, the Reformation to Germanize it and the Enlightenment to make it more French and British. These movements needed to be studied in their national (or more exactly, local) contexts […] However, this should not be done at the price of overlooking certain common characteristics that helped give educated Europeans more of a common culture.Reference Burke25

Burke echoes Nicolette Mout who laments the abrupt switch of focus from country to country at decisive points in European historiography and lauds Piotr Wandycz's The Price of Freedom. A History of East Central Europe from the Middle Ages to the Present, a work that divides Europe into zones that are very variable in their form and do not answer to strict geographical definition.Reference Mout26 Burke, Mout, and Wandycz (amongst others) caution against the reduction of any one part of Europe to a single scheme of historical development.

Sports history both bears out the wisdom of their warning and needs to heed it more keenly. Skirmishes have been fought for some time around the peripheries of the field over the evidence, or lack of it, for sport's existence in the pre-modern era.Reference Carter and Krüger27 The most recent is worth recalling. In 2009, Wolfgang Behringer put a decisive nail in the theory that modern sports arose as a by-product of industrialization, making a case for the largely neglected early modern era instead.Reference Behringer28 A broad range of documents such as memoirs, correspondences, diaries and account books indicate that many ‘modern’ traits might have been evident from as early as 1450, sport becoming increasingly institutionalized through: the creation and codification of rules for ball games such as tennis, pallamaglio (croquet and golf's predecessor), football and calcio; its integration into school and university curricula; the building of sports spaces such as gymnasia, arenas, sports schools, Ballhäuser, jeux de paume and malls; the rise in production and European-wide trade in sports equipment and paraphernalia such as racchetti, palle and palloni; and, not least, the emergence of a professional class of athletes, coaches, referees, ground-keepers and the like. From the Renaissance onwards, the sportification of military exercises and the rise of spectator sports as popular entertainment can also be observed. Behringer's richly suggestive paper delivers a key intervention to debates about the rise of leisure in Europe, and underscores Peter Burke's insight of a decade ago that this history is best served by a model of complex and multilayered growth than by the binary opposites of pre- and post-industrial continuity or discontinuity theories.Reference Burke29 The thesis will need to be supported with further research – presently it contains little socio-historical material and relies heavily on published sources – but the weight of current evidence indicates that the threshold for the beginnings of modern sport – at least in some social classes in some regions – could be moved back before 1800. A consequence of this temporal shift would be a concomitant broadening of focus beyond the British ‘cradle’. In Behringer's argument, early cross-European patterns begin to emerge: Italy is strongly represented, as is France and Southern parts of Germany.

A wider tracking shot of sports history in Europe might also encourage scholarship to think less starkly in dichotomies. Panning across the continent in the nineteenth century, for instance, we might begin to view the difference between German Turnen and British sport in ways that gets us beyond reductionism. Recent cultural history has begun to illuminate the ways in which the bodily practices and social rituals of gymnastics inculcated a sense of the German nation in the decades after its founding. At a time when the idea of ‘nationhood’ still polarized as much as integrated public opinion, gymnastics clubs processed it through several filters. Incubating a certain style of manhood, Turnen fostered a range of auto-stereotypes such as decorum, discipline, courage, obedience and order, which combined to produce an ingrained sense of belonging, delivered emotionality, and rewarded achievement. For all the differences between the gymnastics and team-sports traditions, there is a striking, overlooked similarity – and it is the possibility of this similarity that we simply wish to highlight. Once it has been recognized, there will be a place for further, considered differentiation. For if we leave aside distinctions such as nationalism versus internationalism, the collective versus the individual, we can see in Turnen a physical activity that produced similar effects to those of British sports: decorum, discipline, courage, obedience and order, which combined to produce an ingrained sense of belonging. It should not be forgotten that in Britain these characteristics fostered a military and civil servant class that went on to run the Empire. Furthermore, we should stop to consider what many Turner were actually doing. The militaristic Jahn strand has often been over-emphasized, particularly in English-language accounts, whereas the popular GutsMuths variety of the late eighteenth century, which enjoyed popularity throughout the nineteenth century and was translated into Danish, French, Norwegian, English and Swedish, orientated itself around classical Greek models. These Turner ran, jumped, timed and measured. Set against this, the notion that track and field was invented in Britain looks less compelling. A certain form of athletics that went on to be influential might have gained prominence from Britain, but it landed on very fertile ground in Europe.

Giving serious consideration to time-space dimensions will help interrogate the conclusions of familiar narratives, acknowledge the contribution of large parts of Europe to sport's development (often in trans-national modes), and open new ways of exploring commonalities, even where they are not at first apparent.

4. Avoiding presentism

In all of this, however, we must avoid the lure of presentism. It is tempting to start from where we are today and set out to discover how we got here. Historians of Europe in the age of the European Union have encouraged such an approach, not least the authors of Past and Present's introduction in 1992: ‘The European past has turned out to impinge on the present, and the present to have the capacity to illuminate the past, in more varied and significant ways than we anticipated.’ There can, of course, be no objection to historians using their specialist knowledge to explain and enrich the present, but we should also be aware of those elements, and connections between elements that existed in the past but no longer exist today. Sports history is rich in examples of past alternatives that were only later foreclosed – types of rugby and football that overlapped in the nineteenth century, the popularity of baseball in early twentieth-century Europe etc – and scholarship should trace the boundaries of such activities and ideologies that were fluid in earlier times, as well as the reasons for their ossification or disappearance.

One such example, discussed in greater depth by Marion Kant in this issue, is the line between gymnastics and dance. From the Renaissance, dance, along with sport, formed the basis of ‘polite’ and ethical behaviour, offering a frame within which social norms could be taught and enacted. In later centuries, it maintained both social and political implications, and constantly crossed over into gymnastics and sport. As already noted, scholarship has concentrated on the contrast between British sports and collective gymnastics, but it has neglected the proximity of dance to both forms, particularly the latter. From Friedrich Ludwig Jahn, who sketched the first national and patriotic movement system in Die deutsche Turnkunst 1816, to dance master Franz Anton Roller, gymnastics teacher Adolf Spiess, and dance gurus Rudolf von Laban and Mary Wigman, the distinction between dance and gymnastics was constantly re-negotiated. In fact, as Kant shows, Modern Dance of the early twentieth century developed out of nineteenth-century Turnen and gymnastics. Aiming to revolutionize German society physically and aesthetically, dance incorporated concepts that gymnastics systems had already explored (spatial conceptions, representations of rhythm, etc) and hoped to establish national institutions and evoke national sentiments through movement rituals, communal celebrations and grand spectacle. These projections of motion in time and space created a modern and revolutionary physical practice. Whilst this reached its most extreme articulation during the 1930s when dance, gymnastics and sport became markers of the racial state, it is equally important to observe how precisely this mix of German gymnastics and dance rejuvenated educational curricula and cultures across Northern Europe.

Equally, disciples of Ling's Swedish variant of gymnastics had considerable success in English women's PE colleges. Although in its purest sense functional and physiological, the Scandinavian model was developed by Lingian educationalists such as Dorette Wilkie (formerly Prussian Wilke) at Chelsea College in London to embrace folk dance within the curriculum. The influence of the gym mistress extended over a good hundred years on a long, slow fade. ‘[C]onfident in what she was doing and with an authority which gave her poise’, in Britain ‘she was central to the running of many girls’ schools until the latter part of the twentieth century’.Reference Fletcher30 And as the primary school PE experiences of both authors – in 1950s’ North West England and 1970s’ Northern Ireland – can attest, this influence was not restricted to single-sex environments. Dance in its connection to physical education might now seem like a lost continent, but it should not be ignored. To do so would be to overlook the fact that the twentieth century began and ended with widespread participation in forms of gymnastic culture, moving from collective forms to individualized and feminized practices (pilates, keep-fit, yoga). The route from one to the other – quite probably via discontinuities – has yet to be mapped. Moreover, to view dance and gymnastics merely as some lost Atlantis would be to ignore the fact that at the point when Britain was ‘exporting’ sport to the world, it was itself – in the figure of Martina Bergman-Österberg, who was called to England in the late nineteenth century and later founded her own teacher-training college – importing Swedish expertise to bolster the strength of its ailing children. Or – as Jonathan Westaway has recently shown in an exquisite article on the impact of German gymnastics practices on mountaineering in nineteenth- and early-twentieth-century Manchester and Northern England – it would be to neglect, still more, the long vanished influence of German immigrants on physical techniques, regional identity, and the formation of the middle class.Reference Westaway31 This brings us to our next point.

5. Diffusion and Britain as the ‘Motherland’ of sport

The widely held belief that Britain gave sport to the world is in need of urgent revision. The distribution shown in Table 1 indicates that Britain (a) might have incubated many important athletic disciplines; and (b) could not, however, remotely account for the range of European, far less world, sport. The accompanying narrative of Britain's disdain for the outside world once sport had ‘diffused’ is already subject to significant reassessment. British football trainers who took up employment in large numbers on the continent in the early twentieth century did so less out of missionary zeal than because of the basic need to earn a living: English clubs allowed the board and general manager to select teams (a tradition that afflicted the English national side down to the 1950s) and dispensed with the apparently superfluous skills of experts.Reference Taylor32 And, as Paul Dietschy argues in this issue, it would be negligent not to recognize the French as key initial disseminators, with Paris a particularly strong diffusion point and Eastern Europe a keen recipient, and soon after, with the wind of universalism in their sails, as facilitators of vital international networks and tournaments (FIFA, IOC, Tour de France, and later the European Cup in club football, followed by competitions in basketball, volleyball, handball, and rugby). Future work should, equally, exploit and extend existing research on the Swiss who exerted not inconsiderable influence on the bourgeois culture of the Austro-Hungarian empire and – as is often the case in the early phase of sport – via individual contacts made its presence felt in Eastern Europe.Reference Lanfranchi33

An example – plucked almost at random – will further illustrate the point. If we consider the beginnings of football in Bulgaria, we see that the sport was indeed played around the turn of the twentieth century with British seamen along the Black Sea coast. But as recent research has shown, football was already underway in the preceding decades – inland and particularly around the capital Sofia.Reference Ghanbarian-Baleva34 This incipient sporting activity emerged from two distinct but ultimately overlapping sources: Switzerland and Turkey. In the late nineteenth century, as the Bulgarian government sought to modernize in the wake of the Russian-Turkish war, which had given it independence from the Ottoman Empire, the Minister of Education undertook a tour of Europe and invited Swiss educators to come to Bulgaria, which they duly did, bringing football with them. At the same time, wealthy pupils were returning from schools in Constantinople, where an unofficial football league had already developed. So in Bulgaria alone, football's origins can best be explained in terms of polygenesis: Britain, at most, influencing the coast and the ports, with the Swiss and the Turks playing the major roles elsewhere. Moreover, from the 1920s through to the 1940s, Bulgarian footballers spread across Europe, and could be found playing in leagues in Germany, Austria, Czechoslovakia, Switzerland and France. There was certainly a European football scene at an early stage, and Bulgaria was contributing more to it – at least in terms of player mobility – than Britain. Finally, when Bulgarian sides played against teams from their major rivals Hungary, they were comprehensively beaten. The Hungarians were adept at playing the offside trap; and the Bulgarians were bamboozled at their opponents’ ability to rotate players through different positions. This was already the norm in 1923, some 30 years before Hungary humiliated England at Wembley with their fluidity and vast tactical superiority.

Seen from a Balkan perspective, European sports history takes on a different complexion from the (mostly accurate) one the British tell themselves about the arrogance, ignorance and decline that followed the initial donation phase. The Balkan Games, held between 1929 and 1933 to improve relations between Greece, Turkey, Bulgaria, Yugoslavia, Romania, and Albania,Reference Kissoudi35 have recently received attention, and Bulgarian football might best be captured in a complex post-colonial mode – in a vortex of the former colonizer Turkey, the neighbouring Austro-Hungary Empire, and Britain, the commercial and trading force allied to the Russian liberators. As the case of divided Poland, discussed in the next section, also suggests, parts of sporting Europe demand to be viewed through a different prism to the dominant Anglo-Franco-German lens.Reference Girginov and Mitev36

6. Taking Eastern Europe seriously

Several of our examples have already underlined the importance of regional and cross-national flows and influence. And with our final substantive point we wish to stress the significance of Eastern Europe specifically in such configurations. Until recently, this area has scarcely crossed the radar of European sports history, and – some outstanding exceptions notwithstanding – it is still under-researched. Whilst a common agenda and scholarly language are still lacking, a new network, based at the University of Bonn and sponsored by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft, has begun to make good the deficit and is laying the foundations for an appropriate cultural and social history of the topic.37

Anke Hilbrenner and Britta Lenz's article in this issue presents several theses that have wider ramifications for European sports history in general. Taking Poland as their example, they show how this particular history can only be explained beyond the paradigm of nation states: since these evolved comparatively late in this part of the continent, a regional approach is required to capture the complexity of the area's trans-national and multi-ethnic communities and structures. Due to the tripartite division of Poland, for instance, sport came under varied influences and underwent different rates of development. Habsburg-rule in Galicia opened paths to Austrian, Czech, and Hungarian educationalists, coaches and contacts, while the English model held sway in Russian-dominated Warsaw. In interwar Poland, sports clubs existed along and across the lines of every social, cultural, national or ethnic border. There were not only Jewish sports clubs, but Jewish socialist, Zionist bourgeois and Zionist socialist varieties, while Jews also engaged in Polish liberal or Polish socialist associations. If we take the German, Ukrainian, Russian, Lithuanian, and Polish populations into account, it is clear that sports formed historically contingent rather than fixed national identities. Moreover, given that sport developed primarily in the rural areas of Galicia, inhabited by the most traditional sections of the population such as Ukrainian peasants or Chassidic Jews, rather than the industrial centre Warsaw or the towns of Silesia, it is evident that in Poland, at least, sport did not evolve in accordance with modernization and industrialization. In this part of Eastern Europe, therefore, the pattern of diffusion contradicts both the common paradigm of sport and modernization and, to a certain extent, the popular notion of Eastern European backwardness.

As the Polish case implies, Austro-Hungary must also be taken very seriously. Definitional debate about the status of Central Europe and the divisions of the Cold War should not blind us to the fact that the individual countries succeeding from the Empire laid claim to rich sporting traditions that extended through the century. Despite neither team reaching its expected pinnacle, Austria produced arguably the best football side of the 1930s, Hungary following suit in the 1950s.Reference Molnar38 Austria enjoyed a superlative record in winter sports, and in Mexico City 1968, the last Olympics before the East German drug programme took effect, Hungary finished third (or fourth, depending on the method of accounting). In fact, as the East Germans discovered when they arrived in Budapest in the late 1960s to discuss ways of disrupting the cultural programme at the 1972 Munich Olympics, they were stone-walled by their hosts who told them that the people's love of sport was too important to jeopardize and its running had been outsourced to a semi-autonomous body, largely clear of government interference.Reference Young39 The huge popularity of sport in Hungary is born out by Andrew Handler's From the Ghetto to the Games, which opens up a further fascinating dimension: between 1896 and 1968, Hungarians hauled over one third of Olympic medals won by Jews worldwide.Reference Handler40

Czechoslovakia merits attention in its post-empire context too. Although still in need of further historical rigour, sociologist Maarten van Bottenburg's suggestion that Czechoslovakia owed the exceptional tennis prowess that set it apart from the other Soviet satellites to its Austro-Hungarian heritage offers a potentially rich insight into the long-reach of sporting traditions and infrastructures in the region.Reference van Bottenburg41 All three countries, moreover, should be seen within an extended central European and Adriatic network of footballing powers, which drew in Italy and Yugoslavia and played either side of the Second World War for the Mitropa Cup.Reference Marschik and Sottopietra42 Neither the presence of Italy (twice), Czechoslovakia or Hungary in the finals of the 1934 and 1938 World Cups, nor the later influx of Slovakian players via traditional entry routes into Austrian leagues after the fall of the Iron Curtain should come as a surprise.

7. Conclusion

The history of sport and the history of pan-European culture are littered with good intentions and the topos of almost certain failure. It is certainly an odd mix. Peter Burke notes that ‘the history of European consciousness or the cultural construction of Europe remains to be written’.Reference Burke43 Jacques Le Goff, who edits the well-established series ‘The Making of Europe’, argues that the writing of a truly European history is ‘not yet possible because most of the existing literature […] is based on an idea of the nation state as held in the nineteenth century’.Reference Blockmans44 And back in 1983, Allen Guttmann wrote that the ideal history of European sport had not yet been written and probably never would be.Reference Guttmann45 It still hasn't. But there is hope. Whilst much remains to be done, good work is emerging across the continent.Reference Tomlinson, Young and Hilbrenner46 And whilst ‘the history of Europe looks very different when narrated by an English, French, German, Spanish, Portuguese, Russian, Polish, Serbian, Greek, Romanian historian [… t]he images, representations and implicit expectations of European history and values chang[ing] according to the cultural environment and (quintessentially national) education of the author’,Reference Woolf47 networks are burgeoning for scholars to meet and exchange knowledge and research expertise.48 They are finding that sport in Europe, even in the age of globalization, is characterized both by strong national histories and trans-regional and trans-national patterns and connections. It is this dynamic rather than any bland dichotomy with the United States – to return to our starting point – that defines European sport.

In 1989, Germany's most respected post-war poet and social critic, Hans Magnus Enzensberger, wrote a series of non-fictional travelogues (English title: Europe, Europe), which took in seven countries in the East and West of the continent and deliberately bracketed out Britain, France, and Germany.Reference Enzensberger49 The rationale was a bold one, and the cultural-political zigzag through Hungary, Sweden, Italy, Spain, Poland, Portugal, and Norway yielded a rich understanding of European diversity as well as a sense of what it meant to be European. Interviewed in 2010 by the British press, Enzensberger railed against Brussels bureaucracy, remarking: ‘Europe is the best place to be in the world. But it is not an office or an institution: it's a real thing. It has a much richer future than the codified language of treaties’.Reference Oltermann50 We can only agree, and add – if the poet will permit us to appropriate his line – that it also has a much richer history.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank the contributors to three workshops held at Pembroke College, Cambridge (2008–2010), as part of the Arts and Humanities Research Council network ‘Sport in Modern Europe. Perspectives on a Comparative Cultural History’ (http://www.sport-in-europe.group.cam.ac.uk/index.htm); and the discussants at lectures given at the Institute for Historical Research, University of London (2009), and the School of Sports and Tourism, University of Central Lancashire (2010).

Alan Tomlinson is Professor of Leisure Studies and Director of Research in the Chelsea School's Centre for Sport Research, University of Brighton, UK. He has authored and edited three dozen volumes, and written more than a hundred articles and book chapters on sociological and historical aspects of sport, leisure and consumption. He is a former editor of Leisure Studies and the International Review for the Sociology of Sport. His book Sport and Leisure Cultures (University of Minnesota Press) appeared in 2005; his Dictionary of Sports Studies was published by Oxford University Press in 2010 and The World Atlas of Sport (Myriad Editions/New Internationalist) appeared in 2011. His current research, funded by the British Academy, is on the political economy of the sporting spectacle in Europe 1992–2004.

Christopher Young is Reader in Modern and Medieval German Studies, former Head of the Department of German and Dutch at the University of Cambridge, UK, and Fellow of Pembroke College. He has authored and co-edited eight books on German language, literature and culture, and a further six volumes and journal special issues on international sport, including (with Alan Tomlinson) German Football (Routledge, 2006) and National Identity and Global Sports Events (SUNY, 2006). In 2010, The Munich Olympics 1972 and the Making of Modern Germany (with Kay Schiller), for which he received support from the AHRC, British Academy and the Alexander von Humboldt Foundation, appeared with the University of California Press. Most recently, he co-edited a special issue of German History (2009) on the history of German sport.