Introduction

Party leaders are important to politics, their political parties and voters. They pursue a series of actions, ranging from voter mobilization or the use of political power in their party’s best interest to policy-making, for a higher quality of governance. They have become central drivers of electoral competition in an unprecedented manner. Political parties grow less reliant on their organizational basis and more on the leadership figures. The entire process of personalization of politics makes party leaders the main anchors for the electorate. Party leaders often make the centre of the stage in electoral campaigns and increase the attractiveness of their parties (Aarts et al. Reference Aarts, Blais and Schmitt2011; Bittner Reference Bittner2011). The role of party leadership expands beyond electoral politics and empirical evidence shows how leaders contribute to party organization building or to ensuring party survival in a broader sense. Leaders are actively involved in the recruitment of political personnel (Dowding and Dumont Reference Dowding and Dumont2014; Hazan and Rahat Reference Hazan and Rahat2010; Norris Reference Norris1997), setting the party policy agenda (Scarrow et al. Reference Scarrow, Webb, Farrell, Dalton and Wattenberg2000), the coordination of party activities and the public image of the party (Cross and Pilet Reference Cross and Pilet2016; Pilet and Cross Reference Pilet and Cross2014; Poguntke Reference Poguntke, Luther and Muller-Rommel2002). Consequently, whether it is the case of new parties, fringe parties, or large and well-established parties, leaders rise to prominence (Blondel and Thiébault Reference Blondel and Thiébault2010; Bolleyer and Bytzek Reference Bolleyer and Bytzek2017; Poguntke and Webb Reference Poguntke and Webb2005; Rahat and Sheafer Reference Rahat and Sheafer2007).

The ways in which party leaders fulfil these tasks can be collated under the umbrella concept of leadership style. An entire research agenda on leadership styles emerged at the end of the 1970s when the dichotomy between transactional and transformational leadership was introduced (Burns Reference Burns1978). The transactional leader engages in an exchange relationship with followers or members of the organization cultivating the hierarchical structure of power. Such a leader ensures clarity of responsibilities at various layers, rewards followers for meeting objectives, and corrects them when they fail to meet the objectives (Avolio Reference Avolio1999; Avolio et al. Reference Avolio, Bass and Jung1999; Burns Reference Burns1978). In contrast, transformational leaders contribute to the development of the organization, inspire followers by mentoring and guiding them (including gaining their confidence), and establish themselves as a role model to follow (Bass Reference Bass1985; Kuhnert and Lewis Reference Kuhnert and Lewis1987). Over time the dichotomy was nuanced and instead of treating leaders as belonging to one of the two types, researchers proposed a continuum that ranges between the transactional and transformational extremes. The most widely used measure to capture leadership styles is the Multifactor Leadership Questionnaire (MLQ) developed by Bass and Avolio in various works (Avolio et al. Reference Avolio1999; Bass Reference Bass1985; Bass and Avolio Reference Bass and Avolio1990, Reference Bass and Avolio1997). Although several alternative measurements have been developed (Alimo-Metcalfe and Alban-Metcalfe Reference Alimo-Metcalfe and Alban-Metcalfe2001; Carless et al. Reference Carless, Wearing and Mann2000), this remains the most influential and broadly used measurement of leadership styles.

While this continuum is intensely explored in organizational analysis, management or psychology, it is far less studied in politics. Most of the literature examining political leadership styles focused on the functions performed by the leaders, closely analysing their actions (Elgie Reference Elgie1995; Goldsmith and Larsen Reference Goldsmith and Larsen2004; Helms Reference Helms2012; Kaarbo and Hermann Reference Kaarbo and Hermann1998; Poguntke and Webb Reference Poguntke and Webb2005; Post Reference Post2004). This article aims to analyse the ways in which party members and party experts perceive leadership across several political parties in new democracies. It addresses two gaps in the literature. First, it applies the transactional–transformational continuum to the study of party leaders and uses data from a modified version of the MLQ to provide a comparative assessment. Second, it moves beyond the traditional description of leaders’ actions and compares the perceptions formed at the level of those who are involved in the daily life of the party (members) and those who closely follow what happens with parties (experts). There are at least two reasons for which the comparisons of members and experts’ perceptions about leaders on the transactional–transformational continuum are valuable in politics. To begin with, these could indicate the frames of reference used to enhance further behaviour. For example, members who focus on particular traits of the leadership style are likely to stick to them in assessing future actions. Experts who perceive leaders as having a particular style are likely to interpret future behaviour of the leader through those lenses and emphasize those traits in their analyses. The discrepancies between these two perceptions may explain why experts or members underestimate or overestimate the popularity of party leaders. Another reason is the dichotomy between the ways leaders behaves within the party and with the external world, which may explain different sources for their leadership legitimacy.

This exploratory article focuses on the party leaders of eight parliamentary parties from two new democracies in Eastern Europe (Bulgaria and Romania) between 2004 and 2018. It builds on the transactional–transformational continuum and uses individual-level data from an original survey conducted from May–July 2018. The data comes from two surveys using the same questions. The traditional MLQ questionnaire focuses on self-perception and the leaders were asked to assess their features. In the modified version used here, the questions are in the third person and the respondents are either party members of experts. The party members’ survey was carried out from May–July 2018 at different layers – ordinary members, leaders of local branches and national-level officials – to ensure a broad coverage within each party. The party experts’ survey was conducted from September–December 2018 mainly among academics with solid knowledge about political parties and their leaders.

The next section reviews the literature on party members and experts and explains why these two perspectives on leadership are worth exploring. The section after presents the research design with an emphasis on case selection, data collection and methodology. The fourth section includes the results of the analysis in which the members’ and experts’ assessments are compared. The conclusions summarize the key findings and discuss the major implications of this study.

Internal and External Assessments

Political parties can hardly be defined today in isolation from the concept of party membership. Extensive research shows how party members are an integrated component of party politics. They perform a broad range of functions, have roles during and outside elections, enjoy an increasing number of rights and transform the political party (Cross and Katz Reference Cross and Katz2013; Gherghina and von dem Berge Reference Gherghina and von dem Berge2017; Hazan and Rahat Reference Hazan and Rahat2010; Katz et al. Reference Katz, Mair, Bardi and Widfeldt1992; Scarrow Reference Scarrow2015; Seyd and Whiteley Reference Seyd and Whiteley1992; van Haute and Gauja Reference van Haute and Gauja2015). Party members started receiving official recognition of their involvement in the life of parties, in addition to their traditional role of supporters, with the model of organization based on mass membership. Labelled either as mass party (Duverger Reference Duverger1954) or as a party of democratic integration (Neumann Reference Neumann1956), this model entails a broad decision-making process, intensive membership and territorially developed branches. The well-articulated structures on the ground give strength to the party through local branches, which are populated with members. Since then, the importance of members gained momentum and further typologies include, explicitly or indirectly, membership as a component of most models of party organization (Carty Reference Carty2004; Gunther and Diamond Reference Gunther and Diamond2003; Harmel and Janda Reference Harmel and Janda1994; Panebianco Reference Panebianco1988).

The large majority of contemporary political parties have developed membership organizations. The cartel party model in which political parties use state resources to consolidate their position (Katz and Mair Reference Katz and Mair1995) led to a decrease of the willingness to pursue high membership rolls (Widfeldt Reference Widfeldt1999). However, many political parties continue to strive for a least minimal membership for several reasons. While some tasks fulfilled by members a few decades ago have been transferred to professionals, e.g. the professionalization of electoral campaigns with the help of consultants and experts (Dalton and Wattenberg Reference Dalton and Wattenberg2000; Norris Reference Norris2000; Plasser and Plasser Reference Plasser and Plasser2002; Strömbäck Reference Strömbäck2007), many other functions continue to be performed by members. They are a useful pool of recruitment for candidates in elections or for socializing future leaders, they provide long-term legitimacy to the policies endorsed by the party, they act as the ambassadors within the electorate boosting the party’s image and support, and they contribute to the decision-making process within the party (Kopecký Reference Kopecký1995; Martin and Cowley Reference Martin and Cowley1999; Sandri et al. Reference Sandri, Seddone and Venturino2015; Scarrow Reference Scarrow2015; Seyd and Whiteley Reference Seyd and Whiteley2004). Even in post-communist Europe where party membership is traditionally lower compared with Western Europe (Bielasiak Reference Bielasiak1997; Enyedi and Linek Reference Enyedi and Linek2008; Gherghina Reference Gherghina2014; Gherghina et al. Reference Gherghina, Iancu and Soare2018; van Biezen Reference van Biezen2003; van Biezen et al. Reference van Biezen, Mair and Poguntke2012), parties still rely on fair numbers of members to fulfil the above-mentioned functions.

In addition to their major role as anchors in society, party members can also be seen as a looking-glass through which we can better understand what happens within parties. Their involvement in the party makes members knowledgeable about the internal functioning and provides them with the opportunity to closely observe the behaviour of the party leaders. They are familiar with what happens within the party and they have greater access to information that does not reach people outside the party. As such, they can express informed opinions about the internal party democracy and about their leaders (van Holsteyn and Koole Reference van Holsteyn and Koole2009). Previous research showed that perceptions, preferences, behaviour and the willingness for involvement vary greatly among party members (Bruter and Harrison Reference Bruter and Harrison2009). While, when analysed from the outside, members may seem to hold uniform opinions due to their similar or overlapping ideological views, within a party there is a diversity of opinions on leadership behaviour and party development. Following these insights from the literature, party members have insiders’ knowledge about how party leaders behave and they can make credible assessments. They are in a very good position to assess the leadership style, especially as there is no official line of the party regarding their assessment (and thus they feel no pressure) and the likelihood of conformity is limited. Some variation in their assessment is likely to occur due to the circles of activity (Panebianco Reference Panebianco1988). The opinion on the leader may vary according to how close a member is to the leader.

The external procedure that is traditionally used to assess what happens with political parties or their policies is expert surveys. These tools capture the judgements made by individual scholars who are knowledgeable about specific political parties. They have been used extensively in the research on policy positions, electoral campaigns or coalition formation. Their popularity rests to some extent on their sheer accessibility, making it relatively feasible for researchers to explore topics that may otherwise be difficult to study in a systematic manner. Another important asset is the advanced and relatively similar level of issue understanding by those who are surveyed. Experts have specialized knowledge that can be fairly easily tapped to examine a particular topic (Maestas Reference Maestas, Atkeson and Alvarez2018; Meyer and Booker Reference Meyer and Booker1991). In spite of these advantages, there are also several limitations of expert surveys. Among these, the most common refer to the expertise of those included in the surveys or the ambiguity of their claims. For example, when asked about policy positions, it is unclear what aspects of the party experts assess, during what time frame and what criteria they use (Budge Reference Budge2000). Research has identified ways to evaluate and ensure the validity of expert judgements so that they can be used as measurements with a low risk of creating bias (Marks et al. Reference Marks, Hooghe, Steenbergen and Bakker2007; Steenbergen and Marks Reference Steenbergen and Marks2007).

The expert assessment on parties provides a more neutral perspective, compared with that of party members. The same applies to the specific case of party leadership where party experts are less likely to feel attachment to the leader they assess.Footnote 1 This comes at the cost of having indirect information about the behaviour of the leader and lacking the possibility to personally interact with the person they assess. Unlike the members who are perceived as more homogeneous from the outside, the experts are usually considered as a potential source of different opinions, thus more heterogeneous. However, since many experts have access to fairly similar information and are active in similar environments (i.e. academia or political consulting), their opinions may be quite convergent and homogeneous.

As such, the experts are more uniform on the inside, the opposite to party members, which is a feature that justifies from a theoretical point of view the comparison between these two categories of respondents. Considering these differences of proximity, degree of neutrality and involvement towards the object to be assessed, it is relevant to observe to what extent the opinions of experts are convergent with those of party members. The representation of a leadership style is likely to be more accurate when considering these two perspectives in comparison. The following section briefly explains the data used in this article, with an emphasis on the two types of surveys used.

Research Design

The article uses individual level data from two surveys conducted from May–July 2018 (party members) and September–December 2018 (party experts) about eight political parties in Bulgaria and Romania. The two countries were selected owing to several common features: they are new democracies with a communist past, they have a handful of political parties in parliament, alternation in government is fairly regular and parties differing in terms of leadership longevity. The analysis includes the parties that were present in parliament on a regular basis between 2004 (the starting point of this study) or the year of their formation and 2018. For the Democrat Liberals in Romania the end year is 2014 when they merged with the Liberals. If the party was formed after 2004, then the year of its formation is the start of analysis, e.g. for GERB in 2006. These parties were: Ataka, Bulgarian Socialist Party (BSP), Movement for Rights and Freedoms (DPS), Citizens for European Development of Bulgaria (GERB), Liberal Democratic Party (PDL), National Liberal Party (PNL), Social Democratic Party (PSD), Democratic Alliance of Hungarians in Romania (UDMR). These parties had 19 different leaders between 2004 and 2018, with a total of 33 terms in office. These party leaders and their terms in office were Siderov 1, Siderov 2, Siderov 3 and Siderov 4 (Ataka), Stanishev 1, Stanishev 2, Stanishev 3, Mikov and Ninova (BSP), Dogan 1, Dogan 2, Dogan 3 and Mestan (DPS)Footnote 2, Tsvetanov, Borisov 1 and Borisov 2 (GERB), Boc 1, Boc 2, Boc 3 and Blaga (PDL), Popescu-Tariceanu, Antonescu, Iohannis and Gorghiu (PNL), Geoana 1, Geoana 2, Ponta 1, Ponta 2 and Dragnea (PSD), Bela 1, Bela 2, Kelemen 1 and Kelemen 2 (UDMR). Whenever possible, the current leader of the party was not included; if the current leader had a term in office that ended in 2017 or at the beginning of 2018, members were asked about that term in office as the most recent one. The unit of analysis is the opinion about one leader and the surveys asked members to make an assessment for each term in office for leaders who had that position for multiple terms.

The two surveys had similar questions, almost all with multiple choice answers. The 21 questions related to the leadership style were identical and they were a modified version of the MLQ. In the original MLQ, leaders are asked to evaluate their own style, but the questionnaires used here used a third-party assessment approach in which the classic self-perception MLQ was replaced by the opinion of party members and experts. The party member survey aimed to include a minimum number of 50 members from each political party, distributed as follows: 35 ordinary members, ten with local level office and five for national level office. While this number of 50 respondents may seem small, a survey among party members in these countries is a challenge. Members are suspicious and some parties want the approval of the leader to proceed with it, which in this case was not a very useful approach. The survey was carried out online and answers were recorded in three ways: (1) by respondents who received the link for the survey from the principal investigator; (2) by research assistants who met the members face-to-face; or (3) by research assistants who conducted the interview over the phone. When comparing the answers recorded with these methods there is no observable bias in terms of completion rate or skipping questions. The questionnaires in which answers were provided to fewer than half of the questions were removed from the dataset. Ataka was the only party for which the target was not reached, for the others there is a small variation between 50 and 67 responses; weights were applied.

The expert survey was carried out online and email invitations were sent to scholars working in the field of party politics, journalists from major newspapers covering political parties and representatives of civil society dealing with politics. Almost 90% of those who answered were scholars. The numbers of answers was considerably higher for the Bulgarian parties, with a minimum of 16 for DPS and a maximum of 30 for BSP. In Romania, the minimum number of answers was four for UDMR and the maximum was 15 for PSD. Experts had the possibility to answer for several different parties, but very few used that option. Many of the validity problems outlined in the previous section are not applicable to this expert survey. First, there was self-selection according to the perception of expertise and several invited scholars replied to the invitation explaining that they do not have the knowledge to fill in the questionnaire. This was filled in by experts who considered that they have a high level of knowledge and the questionnaire included a question about how confident they are about their assessment (see the analysis section). Second, the questions were very specific: about particular party leaders, at specific moments in time (years of the terms in office were provided in brackets). If the party leader occupied a public office while being also the leader of the party (e.g. prime-minister), experts were explicitly asked to refer to the party leadership position in their assessment.

The assessment of the leadership style was done as follows in each of the two surveys. Each respondent had to answer 21 questions about the behaviour of leaders, with answers on a five-point ordinal scale ranging from ‘not at all’ (coded 1) to ‘always’ (coded 5). For example, one item reads as follows ‘Expresses with a few simple words what we could and should do’. For each item, there is a score between 1 and 5 with pure transactional and pure transformational as the extremes. The dependent variable is the average of these scores. For example, the average of one Ataka member for the party leader Volen Siderov is 3.048, while the average of another member for the same leader is 4.381. According to the view of the second member the party leader has more transformational features than in the eyes of the first member. Averages are used to avoid problems when a member skips one of the 21 items, i.e. if they answer 20 items then the average is for those and it is comparable with the rest. Less than 10% of both members and experts skipped items.

Results and Discussion

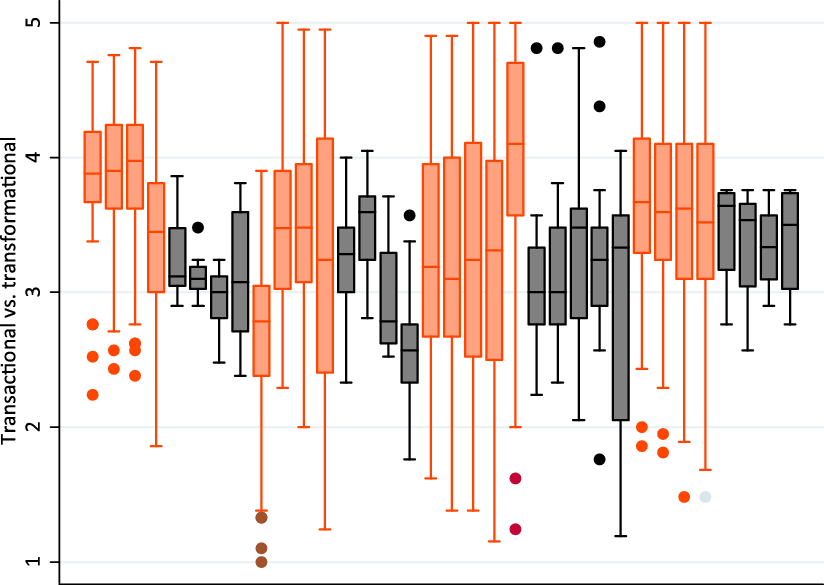

This section compares and contrasts the assessment of party members and experts towards party leadership. Figure 1 include the distribution of individual average scores – to the MLQ – for the Bulgarian parties under investigation. The vertical axis displays the score on the transactional–transformational continuum with a minimum value of 1 and a maximum value of 5. Each box plot indicates the average and distribution of assessments for one party leader. The figure is clustered per political party and presents first the evaluations of the party members, followed by those of experts in darker colour. For example, the first eight plots correspond to the Ataka as follows: the first four reflect members’ opinions about each of the four terms of Siderov (1, 2, 3 and 4), followed by four plots revealing experts’ assessments on the same terms in office. A direct comparison between the assessment of members and experts for the same term in office can be done by contrasting plots 1 and 5, 2 and 6 etc.

Figure 1. The assessment of members and experts for Bulgarian party leaders.

The comparison reveals two major similarities in the ways in which members and experts assess party leaders. The first is that both categories usually distinguish between terms in office held by the party leaders. Although the differences are not very large, it is important to note that these exist and the terms in office coincide with various transactional and transformational features. Sometimes these differences are greater in the case of members as happens with the assessment of Dogan 1 and 2 for DPS, while in other cases the difference is greater among the experts (e.g. Borisov 1 and 2 for GERB). However, there are some instances in which either members or experts fail to distinguish between the terms in office held by the same leader (e.g. Stanishev 1 and 2 for BSP or Borisov 1 and 2 for GERB in the case of members and Siderov 1 and 2 for Ataka or Dogan 1 or 2 for DPS). As these examples illustrate, members and experts see the similarity of leadership styles in consecutive terms in office in difference cases. There is no single leader for which their assessment coincides. Second, with the exception of members’ assessment for some BSP leaders (Stanishev 1, 2 and 3 and Mikov to a great extent), the full range of the transactional–transformational continuum is not used. The assessment is quite compact in many situations. For example, the four terms in office for Siderov (Ataka) are assessed as between 3.3 and 4.8 by the members and between 1.4 and 3.9 by the experts.

There are at least three noticeable differences between the ways in which members and experts assess the party leaders. First, members consider their leaders to be more transformational compared with the opinions of the experts. The most striking examples are for Ataka and DPS with members assessing Siderov and Dogan on average at 4 and 4.6, while the experts place Siderov somewhere in the middle of the scale (2.5) and Dogan slightly above 3. One explanation for this discrepancy is the cult of personality that has been intensely promoted within both parties, resulting in very favourable perceptions on the side of members, with very little dissent throughout the years. In GERB, members assess their leaders above 4, while experts see them as more transactional and place them slightly above 3. The average assessments for the BSP are fairly comparable between the members and party experts. One exception is the assessment for Ninova, who is seen by members as considerably more transformational than the experts consider her to be.

The only time experts see one leader as more transformational than the members is the case of Lyutvi Mestan, the DPS leader who followed Dogan’s long period of leadership. One possible explanation for why members see Mestan as a transactional leader is his failure to organize the party and mobilize support within the DPS in almost three years in office, between January 2013 and December 2015. In addition, his personal affiliation with the Turkish president Erdogan, the problem caused by the Peevski Affair and the very different style compared to Dogan could contribute to a qualification of him as a transactional leader. He was ousted from his position and expelled from the party, forming his own party, called Democrats for Responsibility, Freedom and Tolerance (DOST).

The second difference is that, in general, members classify leaders from the past as more transactional while the most recent ones are more transformational; the only exception is Mestan who faced opposition within the party, as previously explained. Experts, on the contrary, see more recent leaders as more transactional compared with the ones from the past. The exception is GERB where the most recent term in office of Borisov (2) is more transformational than the first, which is in turn more transformational than the term in office of Tsvetanov, the first leader of the party.

The third difference lies in the higher level of agreement regarding the assessment of leaders. Party members have the tendency to be more heterogeneous in their assessment, while the experts are more compact. One possible explanation for this situation is that members have different access to information and to leaders’ behaviour. As explained in the methodology section, the survey included three categories of members. Those on the ground, the ordinary members, have fewer opportunities to interact with the party leader compared with the leaders of local level organizations. Members in the central office benefit from direct access to the actions of the party leader on a regular basis and thus their perceptions may be quite different from those belonging to the members on the ground. At the same time, the experts have access to information about the party leaders from similar sources, usually the media, and thus their perceptions are more homogeneous. The latter is also reflected in their opinion about leadership style. When comparing the assessments of experts for all party leaders (the darker box plots) we can observe that averages evolve around the median point of the transactional–transformational dimension. The values are somewhere between 2.5 (Siderov 4 or Ninova) and 3.2 (Stanishev 2 or Dogan 1 and 2).

Figure 2 reflects the assessment of members and experts for the Romanian party leaders. The similarities identified in Bulgaria – in terms of differences between terms in office and the limited use of the full range of values – hold here as well. There are some nuances with respect to the range of values used for assessment being much broader in Romania. For example, in their assessment of the PNL leader Gorghiu, the party members do not agree on her values. The result is a general spread of values along the transactional–transformational spectrum. The same observation applies to four out of the five PSD leaders and for one UDMR leader.

Figure 2. The assessment of members and experts for Romanian party leaders.

Two differences identified for Bulgaria hold true in Romania. The first difference between members and experts is the one according to which the former perceive leaders as more transformational compared with the latter. The exceptions to this rule are Antonescu (PNL) and Ponta 1 (PSD) who are considered by experts to be slightly more transformational than members perceive them. The second difference lies in the higher level of agreement among experts compared with members regarding the assessment of leaders. With the exception of Dragnea (PSD), the assessments of experts towards party leaders are fairly homogeneous, with considerably fewer outliers compared with those of the party members.

Unlike in Bulgaria, in Romania there is no clear tendency regarding the assessment of party leaders relative to how recently they were in office. There are situations such as the PDL where more recent leaders are considered by members to be more transactional than the leaders from the past (e.g. Blaga compared with Boc 1, 2 or 3). But there are also situations in which more recent leaders are more transformational than those in the past, e.g. in the PSD, Dragnea is considered to be more transformational than both Geoana and Ponta, each with two terms in office, before him. The same applies to the experts’ assessments, as they sometimes consider more recent leaders to be more transactional (e.g. in the PNL, Gorghiu compared with all three before her, but especially with Popescu-Tariceanu and Antonescu) but also more transformational (e.g. in the PSD) or at a similar level (e.g. in the PDL, Blaga with Boc 1 and 2).

Experts’ Confidence and Difference from Members

One of the important conclusions reached above refers to how experts see, on average, party leaders to be more transactional compared with the view of the members. The survey designed for experts included one question about the confidence with which they make their assessment about leadership styles. The question was asked for every leader/term in office and answers were recorded on a four-point ordinal scale that ranges from ‘very much’ (coded 1) to ‘very little’ (coded 4). Out of the total number of experts who answered the survey, three quarters indicated that they have very high or high levels of confidence when making the assessment. Only 5% of those interviewed indicated that they have very little confidence in their assessment. The degree of confidence is related to the amount of information and knowledge that experts have about the leaders.

This article tests for the existence of a relationship between the level of confidence and the experts’ assessment relative to members’ opinion about the leader. The latter is calculated as the difference between each expert assessment and the mean assessment of members for that leader. For example, the mean assessment of members for the third term in office of the PDL leader (Boc 3) is 3.86. An expert who gives a general score of 3 to Boc for his leadership style will have a difference of 0.86, while an expert who gives the same party leader a score of 4 will have a difference of –0.14. The difference is calculated to have positive numbers for more transactional assessments of experts compared with members.

Table 1 presents the correlation coefficients for this relationship, broken down per party. The number of experts was too small to calculate it for every party leader. The results indicate three possibilities. For some parties (Ataka and GERB in Bulgaria and PNL in Romania) there is no relationship between the confidence of experts in their assessments and the difference from the mean assessment of party members. The same conclusion applies to the general correlation for Bulgaria, when the numbers for the four parties are collated. The second possibility is that experts with less confidence in their assessment consider the leaders to be more transactional than do the party members. This is the case for BSP in Bulgaria, the PDL, the PSD and the UDMR in Romania. For BSP and PSD, the coefficients are statistically significant. A common feature of these two parties is that they are both successors of the previous communist parties. Their internal life is not very transparent and both have been characterized at various times as having high degrees of centralization of power. When experts do not know the leaders well, they can base their opinion on the publicity received by the parties when internal conflicts emerge (e.g. contestation, defection). In such contexts the leader’s behaviour can be easily associated with transactional because it is about sorting out the relationship with followers. By putting all these features together one can understand why experts who do not have extensive knowledge about these leaders have a tendency to see them as transactional. The pooled analysis for Romania indicates that, in general, the experts who have less confidence in their assessment are more inclined to qualify leaders as transactional relative to what the members say (0.17, statistically significant at the 0.05 level).

Table 1. Correlations between experts’ confidence in their assessments and the difference from the mean member assessment.

Note: Correlation coefficients are non-parametric (Spearman); ** p<0.01, * p<0.05

The third possibility, observed for the DPS in Bulgaria is to have less confident experts assessing the leader as more transformational than do the members. This result is quite party specific and it is driven by the high discrepancy between members and experts (see Figure 1) about the leadership style of Mestan. Members see him as highly transactional, while experts assess him considerably more transformational, not very far from the style of Dogan in his three terms in office.

Conclusions

This article compared the ways in which party members and experts perceive leadership across eight Bulgarian and Romanian political parties between 2004 and 2018. The results show great variation in the assessment of leadership styles on the transactional–transformational continuum between and within the examined political parties. In addition to the relevant differences between leaders, both members and experts distinguish between the leadership style of the same leader across several terms in office. The members’ assessment has a few particular features relative to the experts: they are more inclined to see leaders as more transformational, their opinions are more dispersed along the continuum and are inclined to see more recent leaders as transformational compared with those of the past; the latter can be observed especially in Bulgaria, but also some Romanian parties display it.

These differences of perception about party leadership are in line with the theoretical expectation that these two categories have access to various types and amount of information. Members have inside knowledge and are more likely to attach emotionality to their evaluation, while experts usually have access to indirect information and are prone to more neutral assessments. Experts who are less confident about their assessment of leaders tend to place leaders closer to the transactional end of the spectrum compared to the other experts, the measurement being done relative to members’ evaluations.

These findings have theoretical, methodological and empirical implications that reach beyond the cases presented here. At theoretical level, they illustrate the importance of analysing leadership styles from several perspectives. Both the internal and external assessment have limitations and the difference between them are fruitful avenues to explore. Further research on party leadership could incorporate both perspectives as either competing dependent variables or as alternative explanations in their analytical frameworks. These differences illustrate how the two sources of data can be complementary. From a methodological perspective, the findings indicate that the evaluations provided by expert surveys can have a bias when experts are less confident on the levels of knowledge. While this is not a novelty, the article presents evidence about its occurrence and emphasizes the necessity to control for it. The empirical implication is the broad variation of party leadership styles between and within political parties. This calls for research to explain what causes this variation.

This exploratory article paves the way to at least three directions for further research. One of these could seek to explain the differences between the assessment of party members and experts by looking at their features, e.g. ideological self-placement, political experience, past membership, etc. Another possible direction for research is to explain, looking at leaders’ behaviour, why members and experts converge in their assessment about that leader on the transactional–transformational continuum. A third possibility lies in qualitative insights to the meaning of these assessments and entails semi-structured interviews with members and experts. These will foster the understanding of what they consider to be transformational and why.

About the Author

Sergiu Gherghina is a Lecturer in Comparative Politics at the Department of Politics, University of Glasgow. His research interests lie in party politics, legislative and voting behaviour, democratization, and the use of direct democracy.