September, 1219: as the armies of the fifth crusade are besieging Damietta, Francis of Assisi and friar Illuminatus cross over to the Egyptian camp to preach to the Sultan Nâsir al-Dîn Abu ‘l-Ma‘âlî Muhammad al-Kâmil. After a number of days, the two friars return to the crusader camp, having apparently spoken with the Sultan, although we know very little about what was said. This has not prevented writers from the 13th century to the 20th, unencumbered by mere facts, from portraying Francis alternatively as a new Apostle preaching to the infidels, a scholastic theologian proving the truth of Christianity, a champion of the crusading ideal, a naive and quixotic wanderer, a crazed religious fanatic, or a medieval Gandhi preaching peace, love and understanding. As for al-Kâmil, he is variously presented as an enlightened pagan monarch hungry for evangelical teaching, a cruel oriental despot, or a worldly libertine.

This brief article is based on the author’s new book, St. Francis and the Sultan: An Encounter Seen through Eight Centuries of Texts and Images.1 Here, I will merely present a few of the examples of how this encounter has been portrayed from the 13th century to the 20th.

The earliest texts that mention this encounter are from chroniclers of thefifth crusade: Jacques de Vitry and the anonymous author of what has been erroneously entitled La Chronique d’Ernoul. Both authors affirm that Francis did indeed go to the crusader camp at Damietta, crossed over to the enemy camp, and spoke with al-Kâmil, who received him graciously and who then gave him a safe conduct back to the crusader camp.

Thomas of Celano embellishes the incident in his Vita prima in 1228. Francis died in 1226; in 1227 the cardinal Ugolino, who had long been one of the poverello’s most ardent supporters, became Pope Gregory IX. The new pope opened the canonization process for Francis in June, 1228 and solemnly presided over his canonization in July of the same year. A canonized saint needs an authorized biography, and Gregory appointed Franciscan friar Thomas of Celano to compose a biography of the new saint. The result, the Vita prima, was meant to demonstrate that Francis was indeed worthy of veneration as a saint, that he corresponded to the canons of sanctity well established by earlier saints’ lives. Moreover, since Francis and his Friars professed a return to the apostolic life (vita apostolica), it was all the more essential to show how Francis indeed corresponded to the model of the apostles.

The apostles had been first and foremost missionaries, spreaders of the Word to infidels, and most of them had suffered martyrdom as a result of their mission. This was not lost on Thomas, who affirms that Francis ‘longed to attain the height of perfection,’ that he was ‘burning intensely with the desire for holy martyrdom.’ For this reason he embarked in 1212 for the holy land, ‘to preach the Christian faith and penance to the Saracens and infidels.’Reference Armstrong, Hellmann and Short2 Kept from reaching his goal by shipwreck, he later set out for Morocco in hopes of winning a martyr’s crown there.

Then, in 1219, Francis ‘journeyed to the region of Syria,’ says Thomas, where ‘bitter and long battles were being waged daily between Christians and pagans.’ Note the geographical vagueness: the crusaders were besieging Damietta in the Nile delta, but Thomas places these events in ‘Syria’. He says that Francis was seized and beaten by the Saracen troops (although the crusader chroniclers, no doubt better informed, said nothing of this). Then he was brought before the sultan, who received him courteously: indeed, he tried to tempt him with the offer of precious gifts, which Francis scorned ‘like dung’. At this, the sultan was filled with admiration ‘and recognized him as a man unlike any other. He was moved by his words and listened to him very willingly. In all this, however, the Lord did not fulfil his desire, reserving for him the prerogative of a unique grace.’

For Thomas as for other Franciscan hagiographers of the 13th century, it is the saint’s ‘thirst for martyrdom’ that drove him to seek out the sultan. Francis, after all, tried to live the apostolic life, and it was natural for him to wish to die an apostolic death: martyrdom at the hands of infidels. The fact that Thomas calls the Muslims ‘pagans’ highlights this parallel. From this point of view, however, Francis’ mission was an embarrassing failure: he succeeded neither in converting the sultan nor in obtaining the much-desired martyr’s palm. Thomas explains this by saying that God had something special in store for the saint, a ‘unique grace’. This ‘unique grace’, it later becomes clear, is the stigmata.

The order of Friars Minor expanded rapidly during Francis’ lifetime and continued to do so after his death. Francis himself became a popular and widely revered saint, both within and outside the order he founded, object of hagiographical legends and painted cycles. One important early portrayal of the saint is that of the Bardi dossal, currently in the Bardi chapel of the church of Santa Croce in Florence (Figure 1). While there has been much scholarly debate on the dating and authorship of this piece, it probably dates from the 1240s and may have been painted by Florentine artist Coppo di Marcovaldo. At the center of this altarpiece is a large devotional image of Francis, with stigmata clearly visible, shown standing in Franciscan habit, a book in his left hand which is apparently meant to represent both the Gospel and the Franciscan rule. Above, the hand of God unfurls a scroll on which we read Hunc exaudite perhibentem dogmata vitae (‘Obey this man, bearer of the rules of life’). Around the central standing Francis are a series of 20 scenes from his life and post-mortem miracles, including (in the lower left-hand corner), his preaching to the Saracens.

Figure 1 Bardi altarpiece (Santa Croce, Florence) – Francis preaches to the Saracens. Permissions: AKG Images, 67 rue Notre-Dame des Champs, 75006 Paris, France. http://www.akg-images.fr/

The artist of the Bardi altarpiece renders a striking image of Francis’ preaching to the sultan and his subjects. Against a golden background, a crowd of men and women, clearly oriental, is assembled in what seems to be a public square (flanked by buildings on both sides). On the left, Francis preaches standing, haloed, barefoot, in Franciscan habit, a rope tied around his waist, with two friars behind him. He preaches to a very attentive audience, an open book in his left hand; he makes a gesture of blessing with the right. On the right of the composition, the sultan sits in a throne before a building, perhaps his palace. His long beard indicates that he also is oriental, but apart from this detail the artist graces him with all the attributes of a European king: a crown, throne, scepter crowned with fleur de lys. Behind this king, a beardless soldier bears a lance and a shield. The artist presents Francis leading the apostolic life, faithful to the Gospel, which he holds in his hand. Christ had ordered the Apostles to go through the world bearing the good news of the Gospel through preaching to infidels. This is exactly what Francis and his companions are doing in this scene. And they have found a receptive audience: all eyes are fixed on the saint. There is no suggestion here of a desire for martyrdom or of violence suffered at the hands of the Saracens. On the contrary, in the context of the other images of the altarpiece, this seems to be an injunction to Franciscan friars to follow their founding saint’s example and to preach the word to the infidels.

For Bonaventure, ‘Seraphic Doctor’, minister general of the Franciscan order from 1257 until his death in 1274, the ardent thirst for martyrdom played a key role in Franciscan spirituality. It was the highest form of love: at once a longing for union with God and a desire to bring the souls of infidels to Him. Bonaventure’s Legenda maior, which became the order’s official biography of its founding saint, insists on the burning desire for martyrdom which drove Francis East. Bonaventure takes up and expands upon Thomas of Celano’s version of Francis’ series of failed attempts to obtain the crown of martyrdom from the Saracens. He embellishes the interview with al-Kâmil, having Francis propose an ordeal: he and the sultan’s ‘priests’ would enter into a fire; he who came out unscathed would have proven that he followed God’s true law. When the Saracen priests refuse, Francis urges the sultan to light a fire anyway; he wants to enter the flames alone. The sultan refuses, fearing lest he provoke a revolt among his people. Francis then rejects the gifts that the sultan offers him, the sultan, ‘overflowing with admiration, developed an even greater respect for him.’ Since the sultan did not wish or did not dare to convert, Bonaventure concludes, Francis left him. Bonaventure makes even more explicit Thomas’ explanation for the failure of Francis’ mission: God had greater things in store for the saint, the stigmata.3

Bonaventure’s official Franciscan biography of the order’s founding saint is redeployed by many authors over the following decades. It also inspires the painters who immortalize Francis’ life and miracles on the altarpieces and frescoes that adorn dozens of churches, notably the cycle of 28 frescoes attributed to Giotto in the upper basilica at Assisi, painted sometime between 1291 and 1299 (Figure 2). Whereas for Bonaventure the trial by fire had been merely proposed, here Francis is shown ready to step into the fire; the saint is in the center of the composition, with Illuminatus behind him. Francis looks back towards the Sultan, seated on a throne that sports a golden frieze of lions. The Sultan, behind whom are armed soldiers, makes a sweeping gesture with his right hand, as if to urge Francis and the Saracen priests to enter the fire. The fire burns before what looks like a pagan temple, topped with small winged statues. To the left are the Saracen priests fleeing the confrontation, looking back towards Francis, their eyes full of defeat. The artist (whether or not it is Giotto) has transformed what for Bonaventure’s Legenda maior was a failure, a proposed ordeal rejected, into a victory: Francis has succeeded in routing the Saracen priests before the attentive eye of the Sultan. Not that the tension is completely resolved; Francis has not yet stepped into the flames.

Figure 2 The trial by fire, Assisi, upper basilica. Permissions: also AKG Images

A fresco from the Bardi Chapel of Santa Croce in Florence is indeed by Giotto. The scene is similar: here the Sultan is at the center, gesturing towards Francis and looking at his Saracen priests who cover their eyes and look away. Francis raises his right arm in a militant, defiant gesture as he prepares to step into the flames. The Saracens’ priests’ refusal to look suggests a willful blindness, similar to that which Christian polemicists attribute to Jews. Here, Giotto seems to present Francis’ moral victory along with recognition of his failure to convert the stubborn, blind Saracens.

Taddeo Gaddi, a student of Giotto’s, painted a series of 28 scenes showing the parallels between the life of Christ and that of Francis for a cabinet in the sacristy of the same church of Santa Croce in Florence (1330–1335). The panel illustrating the trial by fire is clearly inspired by Giotto’s treatment of the subject in the same church. There is one significant change: one of the Saracen priests is in colloquy with the sultan. They seem to be arguing, the priests raising his arms to signal his inability to confront the flames.

While Giotto and Taddeo Gaddi portray the moment of tension as Francis prepares to place his foot into the flames, Sassetta, in 1444, goes literally one step further. Francis, arm raised defiantly, has placed his left foot in the middle of the flames. Everyone is looking; no one flees or turns away. We have for the first time a real miracle in the presence of the young beardless sultan and of the Saracen ‘priests’.

Similarly Benozzo Gozzoli, in a fresco in the church of Montefalco, shows Francis calmly stepping into the midst of the fire, a crucifix in one hand, making a sign of benediction with the other. The ‘priests’ are watching: the sultan has his hands up in a sign of astonishment.

Gozzoli adds another element to this scene: a young woman watches the miracle, with hands up in astonishment. According to the Ugolino da Montegiorgio’s Actus Beati Francesci (c. 1330, better known in its Italian translation, the Fioretti), the sultan granted Francis the right to preach anywhere in his kingdom. A beautiful young ‘pagan’ woman tried to seduce him; Francis followed her into her house, stripped naked, and lay down in the middle of a fire that blazed in the fireplace, inviting her to join him. Dumbstruck, she renounced her debauchery, converted to Christianity, and became a model of piety, converting many. Here Gozzoli has combined the two fires into one, as we see in the legend to the painting:

Quando soldanus misit unam puellam ad tentandum B. F. et ipse intravit in ignem et omnes estupuerunt (‘When the Sultan sent a girl to tempt blessed Francis and he entered in the fire and amazed everyone’).

In other words, the two incidents, separate in the Actus, are combined and the seductress was deliberately sent by the Sultan to lead the saint astray. The same text has affirmed that Francis succeeded in converting, in secret, the Sultan; this is found in widely-distributed printed modern editions of the Fioretti, sometimes with line drawings showing the dying sultan being baptized by two friars.

Yet not all depictions of Francis’ trial by fire portray it as a clear victory. Benedetto de Maiano sculpted five panels for a pulpit in Santa Croce in the 1480s, with scenes from the life and post-mortem miracles of the saint, including one devoted to the trial by fire. Benedetto was of course familiar with the three earlier portrayals extant in the same Florentine church: the Bardi altarpiece, Giotto’s fresco, and Taddeo Gaddi’s painting. For his version of the trial by fire, he follows, in general, Taddeo Gaddi, although he places the encounter in a renaissance palace. He takes from Taddeo the Saracen priest addressing the sultan; yet whereas in Taddeo’s painting this character seemed fearful and defensive, here he seems more confident, and confronts the sultan; it is Francis who lowers his gaze. Behind, another Saracen holds a book, perhaps meant to be the Qur’ân. Giotto and Taddeo had the Saracen priests hide their faces, flee, refuse to confront Francis. Benedetto, on the contrary, shows them standing firm, confronting Francis without the slightest hint of fear or uncertainty. In the 1480s, as the Ottomans conquered large swaths of Europe and gained a foothold in Italy, it was perhaps harder to present Muslims as cowards who flee confrontation with Christians.

This emblematic encounter between East and west continues to fascinate authors and artists beyond the Middle Ages, to the present. The Gesù of Rome, principal church of the Jesuit order, contains a series of eight paintings devoted to Francis’ life, painted at the end of the 16th century: in other words, at a time that was both the height of Ottoman power and a period of widespread Franciscan and Jesuit missionary activity in many parts of the world. Rather than a trial by fire, this anonymous artist portrays Francis and his companions as prisoners tied by the hands and led into the midst of a large and well-tended military camp, to the throne of a powerful sultan – a Turkish sultan, no longer an Arab one, shown in all his finery, perched high on his throne, in the middle of the powerful army at his command. Here the artist emphasizes both the bravado and the pointlessness of Francis’ mission, as the wealthy and powerful Turks seem the polar opposite of the humility and voluntary poverty of Francis and his barefoot friars. Francis’ mission seems a heroic, courageous, but futile attempt to convert an infidel enemy much too enamored of this world to be able to listen to his message.

Yet in the 18th century, as Ottoman power waned and Enlightenment thinkers took a fresh, and often less hostile, look at Islam, the encounter between Francis and al-Kâmil took on a different aspect. For Voltaire, Francis is a fanatic who recklessly comes to Egypt, seeks out the sultan, and rages on in Italian, proposing an absurd fire ordeal. Al-Kâmil, a wise and generous monarch, like his uncle Saladin, wants only peace and prosperity for his realms, but unfortunately he is assailed by the crusaders, dangerous fanatics from a barbarous land. In Francis, the bemused sultan recognizes a harmless fanatic: he treats him kindly, listens to him indulgently, gives him a meal, and sends him on his way.

In the 19th century, romanticism and colonialism converged to create a new orientalist image of the encounter. One example is Gustave Doré’s illustration (Figure 3) for the Histoire des croisades by Joseph-François Michaud, an international bestseller at the time. For Michaud, ‘Francis was drawn to Egypt by the rumor of the crusade and by the hope of making a spectacular conversion’.4 Francis did not succeed in bending the hard heart of the sultan, which proves to the French historian the necessity of waging military crusades against the Muslims. These crusades, although at times marred by excessive violence, sought to bear the fruits of European civilization to the Orient, just like the French conquests in Algeria in Michaud’s own day. Francis’ voyage was not in vain, for Michaud; it inaugurated Franciscan missions to ‘savage peoples’, a heroic and colossal effort to deliver these people from their ignorance and misery.

Figure 3 Gustave Doré, François d’Assise devant le Sultan, in Joseph-François Michaud, Histoire des croisades, illustrée de 100 grandes compositions par Gustave Doré, gravure 50, vol. 1, p. 402 (photograph from http://www.therionweb.de/dore/dore.htm). Permission from: The Bridgeman Art Library, http://www.bridgeman.co.uk/

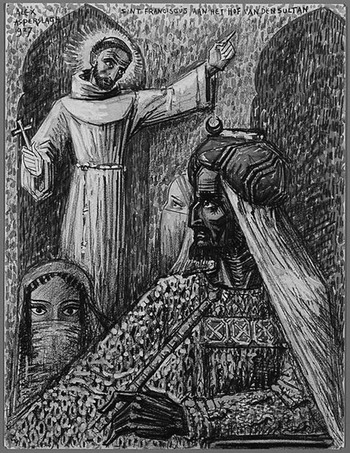

Figure 4 Alex Asperlagh, Sint Franciscus aan het hof van den Sultan (1927) (photograph from http://gemeentearchief.amsterdam.nl/schatkamer/300_schatten/beroemd/actie_voor_de_missie/all.en.html). Permissions: Amsterdam City Archives, Loek de Haan, http://stadsarchief.amsterdam.nl/

Doré’s illustration places the encounter in a Moorish palace that looks like the Alhambra, its walls carved in geometric relief and arabesques, a reception hall where, on a divan draped in rich cloth, the sultan is enthroned, richly dressed, head wrapped in a turban, a golden ring in his ear. Before the sultan stands Francis: standing straight, he holds his left hand over his heart and points with his right hand towards heaven. He speaks to the sultan and looks him squarely in the face. Behind Francis, two turbaned men whisper to each other as they look in from the doorway. The sultan, swarthy, bearded, turns his head towards Francis, but his gaze is lowered: instead of looking the saint in the face, he seems to look blankly and distractedly, without giving the slightest sign of interest or emotion. Francis dominates the solitary sultan, who, seated on a cushioned divan and gazing blankly, incarnates passivity rather than power. The saint of Assisi embodies the virtues of Europe: confidence, eloquence, authority, even audacity – audacity which drove him to this foreign land to preach the Gospel to the most powerful leader of the infidels. These are the qualities that Gustave Doré emphasizes in this etching which dramatizes this encounter. He does not suggest the ascetic rigors of the saint, who here seems well nourished and whose clean bare feet do not seem to have walked far. The saint, in a white habit, bathed in light, bears the brilliance of the true religion back to its cradle, where the shadows of infidelity have reigned for centuries, where doubt and passivity lurk.

For Michaud, Doré, and other Europeans of the 19th and early 20th centuries, Francis of Assisi’s mission to the sultan of Egypt was an act of naïve audacity, yet a noble and admirable act, which exemplified Europeans’ good intentions towards the Muslims, who needed evangelizing and civilizing. Military crusade and preaching missions, far from being antithetical, were complementary: without European armies, the preachers could never bring their load of light and civilization to these hoards cringing in the shadows.

At the end of the 20th century and the beginning of the 21st, this encounter takes on a quite different hue. One no longer celebrates the crusades; one denounces them as nefarious manifestations of violence, rapacity and fanaticism. As a result, one cannot imagine that Francis of Assisi, the gentle saint who spoke with birds and who tamed the wolf of Gubbio, could have approved of these wars. On the contrary, one supposes that he must have been opposed to them and, if one cannot find any textual basis for this anti-war sentiment, one can always affirm that the saint’s contemporaries, blinded by the spirit of the crusades, refused to admit that the saint opposed them. Some authors even imagined that Francis went to Egypt in order to attempt to put an end to the bloodshed, to negotiate peace, or even to initiate himself to Sufism! If the crusades lend themselves to the paradigm of the ‘clash of civilizations’, the peaceful encounter of Francis and al-Kâmil offers, on the contrary, a gleam of hope. Even in the Middle Ages, an age of crusade and jihad, some had cool heads and large hearts and were ready to engage in dialogue instead of war. This is how, for example, Italian journalist Tiziano Terzani presents the encounter, shortly after September 11th, 2001, as a model of peaceful dialogue in the midst of war, in opposition to those who preach hatred. This singular encounter has also become a model of ecumenical dialogue for various Christian authors, especially Franciscans. In January, 2002, Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger, future pope Benedict XVI, affirmed that Francis had understood that the crusades were not the solution to the differences between Islam and Christianity and that he convinced the sultan of this. This peaceful dialogue is a model for today’s Church: ‘let us walk down the path towards peace, following the example of Saint Francis’, exhorts Ratzinger.Reference Ratzinger5 On Christmas day, 2006, in the New York Times, writer Thomas Cahill lauds Francis as a ‘peaceful crusader’ who sought to initiate a dialogue which should be a model for us today, to avoid a clash of civilizations.6

What I have presented here are just a few examples of the portraits of this encounter that one finds between the 13th century and the 20th. For some 13th-century writers, Francis was a new apostle seeking martyrdom; for others, he was a skilled preacher who bested the ‘pagan’ Saracen priests in a debate and proved the truth of Christianity. For Voltaire, Francis was a madman and al-Kâmil a wise and kind ruler who wouldn’t think of harming him. For Idries Shah in the 1960s, Francis was a Christian Sufi whose real motivation in going to Egypt was to train with proper Muslim Sufis. For many writers of the 20th century, particularly Franciscans, Francis was a pacifist who preached against the crusades and was a model for ecumenical dialogue. The manipulation of this event tells us more about our own changing hopes and fears regarding Islam and East-West relations than it does about the historic Francis or Al-Kâmil. If history is a mirror, it reflects above all a darkened and distorted image of our own worries and aspirations.

John V. Tolan received his BA in Classics from Yale and his PhD in History from the University of Chicago. He has taught in universities in North America and Europe and is currently Professor of Medieval History at the University of Nantes (France). He is author of Petrus Alfonsi and his Medieval Readers (Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 1993), Les Relations entre les pays d’Islam et le monde latin du milieu du X èmesiècle au milieu du XIII èmesiècle (Paris: Bréal, 2000), Saracens: Islam in the Medieval European Imagination (New York: Columbia University Press, 2002), Sons of Ishmael: Muslims through European Eyes in the Middle Ages (Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 2008), and St Francis and the Sultan: An Encounter Seen Through Eight Centuries of Texts and Images (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008; French edition published in Paris: Seuil, 2007).