Over the last decade, the EU’s fundamental values concerning respect for democracy, pluralism, and the rule of law have been under attack in several Member States of Central and Eastern Europe (CEE) (Sitter and Bakke, Reference Sitter and Bakke2019). The EU has been noted for its ineffectiveness in addressing this problem by failing to take measures that would stem backsliding on fundamental values (Kochenov et al., Reference Kochenov, Magen and Pech2016) and thereby protect its own ‘normative integrity’ (Lacey, Reference Lacey2017). Particularly puzzling in this regard is the behaviour of European Political Groups (EPGs) in the European Parliament (EP). While some EPGs have consistently attempted to use the limited powers of the EP to defend the EU’s fundamental values against backsliding, others have been much less consistent. This is particularly true of the EP’s largest EPG, the centre-right European People’s Party (EPP). The EPP has adopted an accommodative attitude towards the Hungarian party Fidesz – a formerly Conservative Party turned Populist Radical Right (PRR)Footnote 1 since the country’s accession to the EU in 2004 (Batory, Reference Batory2016; Pytlas, Reference Pytlas, Herman and Muldoon2018). From 2010, the party has governed Hungary with a two-third majority under the leadership of Viktor Orban and systematically dismantled linchpins of democracy, the rule of law, and political pluralism in Hungary. They have done so without receiving sanction from the EPP until September 2018, when the conservative MEPs backed triggering procedures that could lead to sanctions under Article 7 of the Treaty on European Union (TEU). By contrast, the EPP bolstered a confrontational stance towards Poland’s PiS – another PRR party heading a democratic backsliding state since 2015 – voting in favour of proceedings, Article 7 proceedings as soon as January 2018, three short years after PiS took power.

The central explanation for the EPP’s accommodative attitude towards Fidesz has been one of EPG strategic interests: simply, Fidesz is a member of the EPP, and therefore the EPP as a group has been accommodative to maintain Hungarian seats within its ranks; meanwhile, PiS is not a member and therefore the EPP can afford to be more confrontational in this case (Müller, Reference Müller2015; Kelemen, Reference Kelemen2017). Because of the dominant position of the EPP in the EP (274 seats in 2009–2014 and 221 in 2014–2019), as well as their dominant position in the European Commission, this strategic EPG hypothesis has also been used to explain the main reason why EU action under Article 7 against the Fidesz government has been stalled since 2010 (Sedelmeier, Reference Sedelmeier2017). In other words, the relative clout of the EPP across European institutions has served as a powerful bulwark in protecting Fidesz against sanctions for its ‘misdeeds’ – a bulwark largely unavailable to PiS. In addition to this strategic explanation of the EPP’s accommodative stance, attention has also been drawn to constructivist factors pertaining to attitudes towards fundamental values and European integration that may be influencing individual MEPs in their voting behaviour (Sedelmeier, Reference Sedelmeier2014, Reference Sedelmeier2017; Meijers and Van der Veer Reference Meijers and Van der Veer2019b).

We find the evidence suggesting a combination of strategic and constructivist explanations compelling. They tell the beginning of a story, which we hope to deepen. We aim to do so with the help of a dataset assembling the votes of 274 EPP MEPs in 2009–2014 and 221 in 2014–2019 on a total of 24 resolutions that address violations of fundamental values by Member States since Hungary became a ‘problem case’ in 2010 (see Appendix 1 for the full list). Unlike previous studies, which have analysed a small number of votes focusing on sanctions towards Poland and Hungary to explore their hypotheses, our dataset gives a more comprehensive picture of EPP MEP voting behaviour on fundamental values, including a wider range of data points to explore possible changes in voting behaviour over time.

We develop three lines of inquiry. First, we ask to what extent have EPP MEP’s been cohesive in their response to offenses related to fundamental values? Although it has been acknowledged that not everyone toes the party line within the EPP on questions of fundamental values, this phenomenon and its potential significance for understanding the EPPs voting behaviour on these issues has not been sufficiently explored. We precisely identify the cohesion of EPP MEPs on votes pertaining to fundamental values, demonstrating that this cohesion is far lower than average voting cohesion across issues. Second, we ask to what extent has the EPG’s response to fundamental values violations evolved over time? This phenomenon is yet to be studied in detail. We find that, over time, EPP MEPs are increasingly likely to vote in favour of resolutions that address fundamental values infringements. Taken together, the relatively low levels of cohesion and the fact that cohesion has been decreasing over time suggests that the strategic interests of the EPP may not have quite as much explanatory weight as previously believed. Third, we test this by asking what determines the extent to which individual EPP MEPs favour action against the abuse of fundamental values? As with previous studies, we explore both strategic and constructivist variables. In the first instance, we explore the standard strategic hypothesis concerning the extent to which EPP party membership determines voting behaviour. However, we also test another set of strategic variables that have been less investigated. Specifically, we attempt to determine the degree to which the strategic interests of national parties to which MEPs belong could play a role in influencing their voting behaviour. In the second instance, we test standard constructivist variables such as Green-Alternative-Libertarian (GAL)/Traditional-Authoritarian-Nationalist (TAN) ideology and Euroscepticism. Uniquely, we attempt to understand whether these strategic and constructivist factors can explain intra-party variation within the EPP, rather than just inter-party variation between the EPP and other EPGs, which has been the focus of previous studies.

Our analysis corroborates the dominant narrative that EPP strategic interests play a central role in determining EPP MEP voting behaviour on fundamental values. However, our paper also accounts for phenomena that the EPG strategic hypothesis cannot fully explain. Most importantly, this includes the unusually high levels of intra-EPP dissent, and the increase in this dissent over time, which we find on EP votes on fundamental values. By bringing in the role of national party strategic interests and further exploring a range of constructivist variables, we go a long way towards explaining these phenomena. Overall, our paper achieves a better appreciation of the ways in which party politics can either help or hinder the defence of fundamental values in the EU.

The paper proceeds as follows. We first provide a brief overview of the context in which the EPP emerges as an intriguing player in the debate on fundamental values in the EU. In doing this, we highlight what the literature tells us so far about the voting behaviour of MEPs on fundamental values issues, and which blind spots still remain. Second, we provide the first analysis of the positions of EPP MEPs on our sampled resolutions, focusing on their degree of cohesiveness and evolution over time. Third, we develop a series of hypotheses to explain our preliminary empirical findings, based on what we know of MEP voting behaviour and centre-right strategies towards PRR parties from the existing literatures. Fourth, we test these hypotheses, presenting our methods, model and findings. We conclude by discussing what these results add to our understanding of contemporary obstacles to EU sanctions against backsliding Member States.

The EU politics of fundamental values: A complex affair

The partisan foundations of EU inaction

Many detailed institutional reports and academic accounts have convincingly demonstrated that serious breaches of EU fundamental values have occurred in Hungary and Poland under the stewardship of Fidesz and PiS, respectively (Norwegian Helsinki Committee, 2013; Dawson and Hanley, Reference Dawson and Hanley2016; Kelemen, Reference Kelemen2016; Bogaards, Reference Bogaards2018; Przybylski, Reference Przybylski2018; Freedom House, 2019; Sitter and Bakke, Reference Sitter and Bakke2019). Yet the EU has, so far, been ineffective in addressing the problem (Kochenov et al., Reference Kochenov, Magen and Pech2016). The primary available mechanisms are outlined in Article 7.1, 7.2., and 7.3 TEU, allowing for the EU to issue an official warning to offending Member States (Article 7.1) and ultimately to suspend its voting rights if these fail to comply (Article 7.2 and 7.3). It took the EP, with the support of the majority of the EPP, 8 years after Fidesz obtained its two-thirds domestic majority in 2010 to trigger the first steps of this procedure. Starting in 2015, Polish backsliding on fundamental values has been both less aggressive and taken place over a shorter period of time than in Hungary. Nevertheless, the EP was willing to vote against PiS to support the Commission in its triggering of Article 7.1 against Poland in March 2018 (2018/2541(RSP)).

Scholarship has focused on the legal and institutional reasons for the EU’s relative incapacity to protect its normative integrity in this rule of law crisis (Scheppele, Reference Scheppele2013; Müller, Reference Müller2015; Pech and Scheppele, Reference Pech and Scheppele2017; Sedelmeier, Reference Sedelmeier2017). Crucially, Article 7 is the main legal vehicle with which to sanction states guilty of violating fundamental values, yet Article 7.2 and 7.3 require the unanimous support of all other Member States. Furthermore, any new legal mechanisms with real sanctioning power are unlikely without some kind of Treaty revision, which also faces an unanimity hurdle.

Beyond these procedural shortcomings, there are distinctly political reasons for the EU’s lack and inconsistency of action against fundamental values offenders. After all, the warning mechanism of Article 7.1 does not involve formal sanctions, and it can be triggered by the EP and confirmed by the Council acting by a majority of four-fifths rather than by unanimity. Yet not only did the EP take eight years to begin to push back against Hungary with a vote to trigger Article 7 in 2018, but two years later, the Council still proves unwilling to cast a vote on the Parliament’s symbolic recommendation. This incapacity of EU institutions to use the little latitude which the Treaties do provide points to alternative motives of inaction than simply a ‘lack of options’.

A small literature has, so far, considered the political foundations of the impasse on fundamental values violation, with a particular focus on the role of the EP. Sedelmeier (Reference Sedelmeier2014, Reference Sedelmeier2017) and Meijers and Van der Veer (Reference Meijers and Van der Veer2019b) especially have analysed the determinants of MEPs’ inclinations towards sanctions against offending states. Focusing on a small number of votes related to fundamental values violations in specific Member States, they test both rational institutionalist hypotheses relating to the strategic interests of European Party Groups, and constructivist ones related to MEP’s normative commitment to the rule of law and European integration. These studies show that a number of individual factors contribute to frustrating sanctions, including ideological proximity with incriminated states, unfavourable views of European integration, and pre-existing alliances with targeted parties in European Party Groups. Being a member of the same EPG, especially, will make an MEP less likely to take a confrontational stance in cases of rule of law backsliding.

Partisan support for incriminated states has, therefore, emerged as a key determinant of EU inaction. The role of the conservative EPP as a veto player is especially relevant here. As the largest parliamentary group in the past two legislatures, the EPP bears a heavy responsibility in staling action in the EP against the Hungarian Fidesz, an EPP member. The EPP majority voted against six out of the seven EP resolutions and own-initiative procedures adopted to the Hungarian situation since 2011. On the other hand, it allowed action against PiS, a European Conservatives and Reformists (ECR) member, supporting three out of the four related resolutions taken by the EP. The ECR – a small EPG – could afford PiS little protection from unfavourable votes, while the EPP’s sheer size gives it substantial clout to protect its member parties, such as Fidesz, from unfavourable votes (Kelemen, Reference Kelemen2017).

While the EPP’s role in the EU’s crisis of fundamental values is widely recognized, few studies focus specifically on the reasons motivating this obstructive behaviour. The EPP’s leniency towards Fidesz is widely assumed to stem from strategic self-interest: the EPG has taken a soft stance on Hungary’s offenses because it prioritizes maintaining the support of Fidesz as a member party (with 14 seats in 2009–2014 and 12 in 2014–2019) over the protection of EU fundamental values (Sedelmeier, Reference Sedelmeier2014; Müller, Reference Müller2015; Kelemen, Reference Kelemen2017). Daniel R. Kelemen (Reference Kelemen2017, 226) states the point succinctly: ‘Orbán’s Fidesz party delivers MEPs to the EPP bloc in the EP, and in exchange for his ongoing participation in their party group, they turn a blind eye to his misdeeds’. Pech and Scheppele deploy a very similar narrative: ‘losing Fidesz MEPs, who have been loyal members of the EPP when it comes to voting, would undermine the EPP’s primacy within the Parliament and its ability to appoint its members to the most powerful offices’ (Pech and Scheppele, Reference Pech and Scheppele2017, p. 33). As EPP seats have declined with the British Conservative Party leaving in 2009, keeping Fidesz on board as a member might have been particularly important to further the EPP’s ‘policy-seeking’ and ‘office-seeking’ goals (Strom, Reference Strom1990).

The EPP’s position: More than meets the eye

This strategic hypothesis is compelling, but it tends to minimize two key dimensions of the EPP’s position on fundamental values violations. First, there is some empirical evidence that the conservative EPG is in fact strongly divided on these issues. This point is often acknowledged in passing. Kelemen, for instance, recognizes the existence of dissenting figures, such as Viviane Redding or Jose Manuel Barroso (Kelemen, Reference Kelemen2017, p. 225; Kirchick, Reference Kirchick2013). Meijers and van der Veer (Reference Meijers and Van der Veer2019b: 14) also highlight that in the two Hungary-focused resolutions that they analyse, ‘approximately 30 per cent of MEPs from the EPP condemned (the Hungarian) situation (…), indicating important divisions within the party group’. Pech and Scheppele (Reference Pech and Scheppele2017: 32) similarly note that ‘at least half of the EPP members split from the party’s official position and allowed the Tavares Report to pass in July 2013’. However, none of these studies expand on the evidence of these divisions, nor do they present the dissent as important for understanding the complex motivations of EPP MEP’s.

Second, and relatedly, the evolution of the EPP’s position over time also tends to be overlooked. The majority of conservative MEPs switched to supporting the activation of Article 7 against Hungary in September 2018, with 115 in favour, 56 against, and 28 abstaining (2017/2131(INL), thus lifting the EPP’s effective veto on EU action. This was followed by a decision of the EPP Political Assembly in March 2019 to suspend Fidesz’s EPP membership. In September 2020, the EPP also joined forces with other EPGs to demand from the Council a more robust proposal to condition EU funds on respect for the rule of law by Member States (European Parliament, 2020). By tending to treat the EPP as a monolithic bloc and assuming self-interest as its driving force, the current literature fails to adequately explore the role that other factors may play in structuring the position of individual EPP MEP’s on fundamental values issues and its evolution over time.

In this paper, we explore this evidence further, and in this process nuance and add robustness to current understandings of the EPP’s position. We study the votes of 274 EPP MEPs in 2009–2014 and 221 EPP MEPs in 2014–2019 on 24 resolutions pertaining to respect for democratic standards, the rule of law, and human rights by Member States. The paper addresses three key research questions: first, to what extent have EPP MEPs been cohesive in their response to rule of law-related offenses? Second, to what extent has the EPG’s response to rule of law offenses evolved over time? And third, what determines the extent to which individual EPP MEPs favour stronger action against abuse of fundamental values?

Our paper builds on existing studies in several ways. First, instead of focusing solely on the few resolutions that have targeted Hungary or Poland, we situate the stance of EPP MEPs on these critical cases in a wider context, studying the EPP’s legislative politics in matters pertaining to fundamental values as a whole since 2009. The EP has Voted on a total of 28 resolutions or own-initiative procedures that broadly concern the respect for fundamental values within the EU.Footnote 2 We identified these by conducting an extensive search into the EP legislative database using the words ‘Democracy’, ‘Rule of Law’, and ‘Human Rights’. We solely selected resolutions that address fundamental values and their violation within EU Member States, thereby excluding resolutions on third countries or on respect for democratic standards by and within EU institutions. Fifteen of these resolutions target violations in specific Member States, and 6 out of these 15 instruct the EP itself, or other EU institutions, to take concrete steps towards advancing the Article 7 procedure. By studying EPP MEP votes on 24 of these resolutions, for which roll-call data were available on VoteWatch or the EP website,Footnote 3 we are in a unique position to understand the stance of conservative MEPs towards Hungary in light of the party group’s wider fundamental values politics over the past decade.

Secondly, this larger sample allows us to explore the temporal dimension of the EPP’s stance, and whether its changing position on Hungary is part of a larger shift in the EPP’s politics on fundamental values. Our sample considers decisions related to fundamental values taken by the EP since the Hungarian Media law of 22 July 2010, which triggered attention to fundamental values breaches in Hungary and motivated the Parliament’s first resolution on the Hungarian case in March 2011 (2011/2510(RSP)) (Brouillette et al., Reference Brouillette, van Beek and Dencik2011, p. 1). As detailed in our methods section below, we model our data in the form of a conditional risk set model in order to account for the factors that increase likelihood of EPP MEPs voting in favour of these resolutions, thereby adding to the negative binomial regression models applied by Meijers and van der Veer (Reference Meijers and Van der Veer2019b).

Third, in drawing attention to the issue of party fragmentation and focusing on 24 resolutions, we are able to explore the relevance of a larger number of factors than previous studies. We verify whether the factors explaining inter-party variance in EP votes that sanction Hungary or Poland – for example GAL/TAN attitudes or party Euroscepticism – hold for explaining intra-EPP variance as well. We also test a number of additional hypotheses derived from the wider literature on EP competition and the scholarship on the accommodation of PRR parties by centrist forces, hypotheses that have until now been sidelined by the literature on fundamental values politics in the EP. This allows us to complexify the notions of ‘strategic’ and ‘constructivist’ support for parties in government who violate fundamental values.

Understanding the position of EPP MEPs on fundamental values

The cohesion and evolution of EPP votes

To answer our first two questions on the cohesion and evolution of EPP votes on fundamental values, we construct an original dataset containing roll-call data of the 24 resolutions described above, obtained from VoteWatch or the EP website. We operationalize our dependent variable in a binary way: it takes the value of 0 if an EPP MEP votes against the resolution and 1 if they vote in favour. We exclude abstentions, that is, MEPs who did not vote or were absent.Footnote 4 Data on the party line – operationalized as the plurality vote choice of the whole EPP group – and the party group affiliation of the rapporteur are both retrieved from VoteWatch.

Studies of EP votes on the Hungarian situation acknowledge significant divisions among EPP MEPs (Kelemen, Reference Kelemen2017, p. 225; Kirchick, Reference Kirchick2013; Meijers and Van der Veer, Reference Meijers and Van der Veer2019b, p. 14; Pech and Scheppele, Reference Pech and Scheppele2017, p. 32). Our first empirical step is to explicitly explore the nature and relevance of party cohesion in the EPP on Hungary and fundamental values votes more generally. According to Shaun Bowler and Gail McElroy (Bowler and McElroy, Reference Bowler and McElroy2015), intra-party dissensus tends to be greatest when there is inter-party disagreement between the largest parties on a given vote. As such, given the high disparity in voting patterns between the EPP and the Progressive Alliance of Socials and Democrats on issues pertaining to backsliding in Member States, we can also expect high levels of intra-party disagreement on these resolutions.

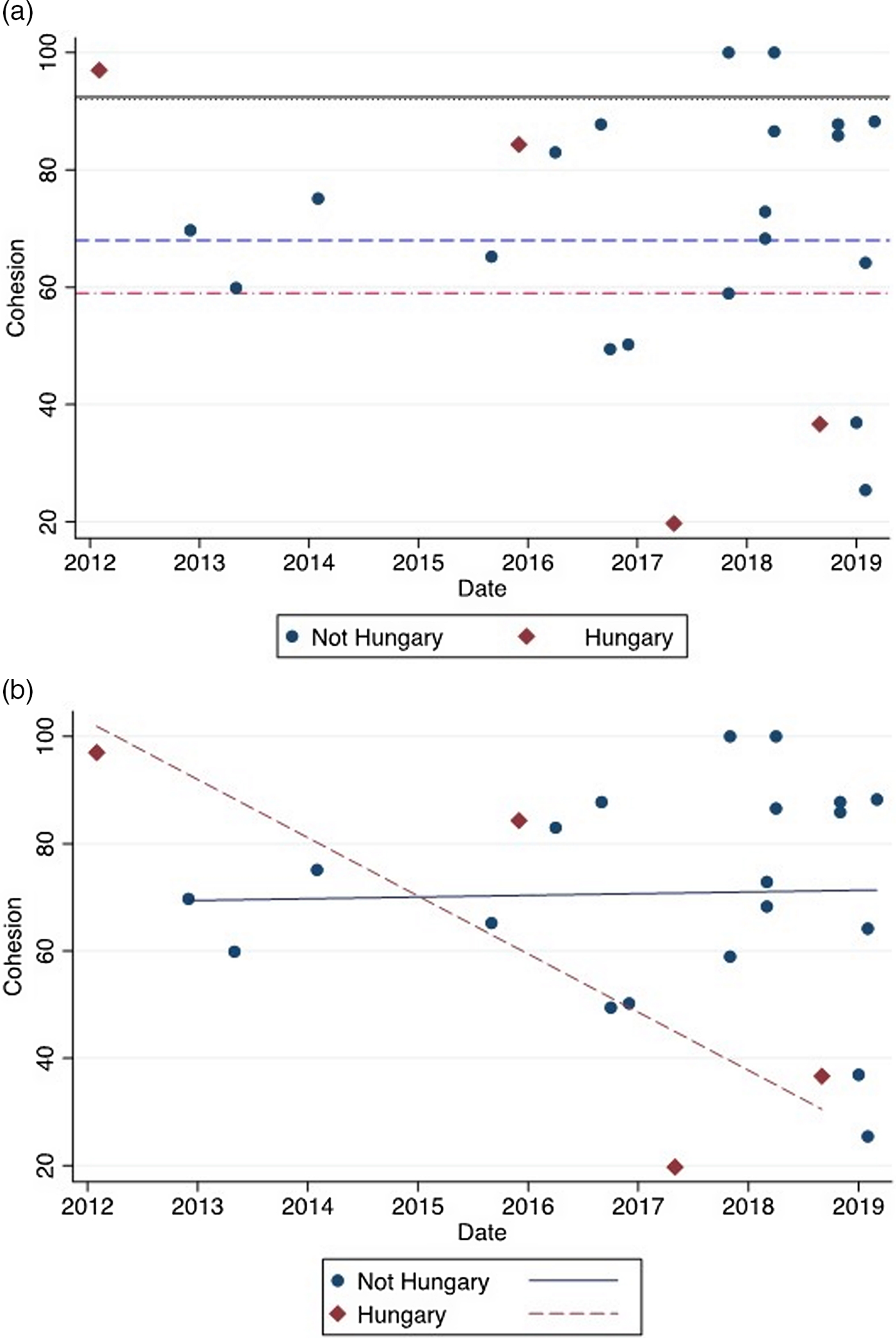

To verify this assumption, we use vote cohesion data collected and made available online by VoteWatch,Footnote 5 which calculates cohesion scores for each individual vote using the ‘Agreement Index’ following the Hix-Noury-Roland formula – the EPG cohesion rate is then the average of the scores of the Agreement Index.Footnote 6 In Figure 1a, we compare the average cohesion score of the EPP across the seventh and eighth terms of the EP (full black line); the average cohesion score for votes in the policy field of Justice and Civil Liberties for the same period (dotted black line); the average cohesion score for the 24 rule of law-related resolutions under study (dashed line); and the average cohesion score for the four votes in our sample about Hungary (dashed-and-dotted line).Footnote 7

Figure 1. (a) Cohesion score of the resolutions in the analysis. (b) Trends of cohesion scores in the analysis.

Note: (a) Diamonds in red indicate resolutions to Hungary. Circles in blue indicate resolutions not relating to Hungary. The solid line signifies the average cohesion score of all EPP votes in the period studies, the average cohesion score of all resolutions relating to civil liberty. The dashed line shows the average cohesion score of all resolution in the study, the ‘dashed-and-dotted’ lines the average cohesion score of all resolutions relating to Hungary. (b) Diamonds indicate resolutions to Hungary, circles resolutions not relating to Hungary. The solid line indicates the fitted trend line for resolutions not relating to Hungary, the dashed line shows the fitted trend line relating to Hungary.

Our data show that intra-EPG dissensions on these issues are particularly high. There is significantly less cohesion on these issues within the EPP than on most other EP policies. As shown in Figure 1a, in the period 2009–2019, EPP average party cohesion on these votes (67.3%) is considerably weaker than the overall average cohesion of EPP votes in the same period (92.5%) and also far lower than for votes originating in the Civil Liberties, Justice, and Home Affairs committee (92.03%). The average cohesion for votes on the Hungarian situation is even lower, at 59%. Figure 1b shows the fitted trend line for all resolutions in the study and the resolutions relating to Hungary. While there is a downward trend (i.e., a decrease in cohesion over time) for the votes relating to Hungary, this is not the case for the other resolutions in the analysis.

We now turn to the evolution of EPP MEP votes over time. As emphasized above, the party’s position on sanctions towards Hungary has evolved in the past decade, from supporting Fidesz in the term 2010–2014 to adopting a more critical position from 2018 onwards. We aim to verify whether this corresponds to a wider shift of EPP MEP positions on fundamental values issues or corresponds to an isolated response towards a particular country. To test this question empirically, we rely on the descriptive data in Figure 2. The figure shows that there has been indeed a wider shift of EPP MEP positions on issues relating to fundamental values, with a positive evolution on votes of this kind as a whole in the second half of the 2014–2018 term especially. This seems to indicate that EPP MEPs become more likely to vote in favour of resolutions as time progresses. As a robustness check, we fit a fixed-effects logistic model with dummy variables for the year a resolution was voted on. The coefficients for the yearly dummies are generally positive and increase in size. This indicates that the likelihood of voting in favour of one of the resolutions increases from year to year, and thus that there is an increase in the propensity to vote for a resolution over time (see Appendix 3). Patterns over time by member state can be found in Appendix 6. As discussed further in the conclusion, a noticeable drop in votes in favour of resolutions seems to occur in 2015 for all EPP MEPs, a period during which a large number of Syrian refugees came to Europe via the so called Balkan Route.

Figure 2. Share of votes in favour for the whole EPP group per resolution, smoothed.

Hypotheses for intra-EPP disagreement on fundamental values votes

Having established the high levels of intra-EPP division on issues relating to the EU’s normative integrity, we now outline several hypotheses that could help to explain this phenomenon. In line with existing literature studying fundamental values votes in the EP, we posit that there are both strategic and constructivist reasons for EPP MEPs either opposing or supporting EU intervention. We test a number of variables that studies have suggested influence the voting behaviour of MEPs on these debates. However, we also consider a number of hypotheses derived from other relevant literatures, which have not yet been applied to this specific question.

Strategic motives related to EU politics

First of all, using our larger sample of resolutions, we follow previous studies in testing the EPG strategic hypothesis concerning the influence of being a member of an EPG on an individual MEP’s voting behaviour when a member of the EPG is targeted. In line with the expectations of this literature, we hypothesize

Hypothesis 1: EPP MEPs are less likely to vote in favour of a resolution that targets one of its members as opposed to resolutions that do not.

From what we know of the literature on competition in the EP, however, the strategic interests of the EPG are not all that count when it comes to understanding the voting behaviour of MEPs more generally. Previous studies on fundamental values votes in the EP have neglected to explicitly explore the potential role that the strategic interests of national parties on the European level may play in influencing the voting behaviour of their MEPs. The literature on competition in the EP teaches us that party loyalty is complex in the EU precisely because MEPs have two main principals: their EPG and their national party (Hix, Reference Hix2002). Even though EPG membership can only explain 15% of variance in individual MEP attitudes to policy issues (with nationality and ideological preferences on the left-right scale accounting for the rest), it is striking that voting cohesion across EPGs hovers around 85 per cent (Willumsen, Reference Willumsen2018) to 90 per cent (Corbett et al., Reference Corbett, Jacobs and Shackleton2011). A number of factors can be cited to explain this phenomenon, such as the fact that EPGs control the career trajectories of MEPs within the EP and so have a material carrot and stick with which to exert party discipline.

However, the literature also suggests that national parties can have an important impact on voting behaviour, both in terms of encouraging MEPs to defect from or stay true to the EPG party line (Hix et al., Reference Hix, Noury and Roland2007). Specifically, MEPs tend to be more responsive to instructions by their national party when the national party is in government and therefore a member of the European Council and Council (Hix et al., Reference Hix, Noury and Roland2006; Willumsen, Reference Willumsen2018). A major reason for this, at least when it comes to the Council (Willumsen, Reference Willumsen2018), appears to be the fact that MEPs are co-legislators with the Council. As such, when agreement is reached in the Council on legislation that favours or disfavours the interests of a particular national party, the relevant minister is likely to exert more pressure on the voting intentions of MEPs belonging to the same national party in order to get the legislation through, or to block it, as the case may be.

There are good reasons to expect that governments with a seat at the Council will instruct affiliated MEPs to oppose EU intervention when it comes to fundamental values issues. It has been long recognized that, given the high consensus hurdles within the Council and the European Council, an atmosphere of deliberation (or at least collegial bargaining) is required if individual states are to build coalitions of mutual interest to advance their respective goals and in order for these institutions as a whole to come to effective conclusions (Warntjen, Reference Warntjen2010; Puetter, Reference Puetter2012). This is especially pertinent as both institutions have taken on greater responsibilities since 2008 in managing responses to the Euro crisis, refugee crisis, and COVID-19 crisis. On this basis, it is reasonable to argue that national parties in government, both individually and as a collective, have strong incentives to ensure that they do not alienate other national governments within the EU by, for example, pursuing sanctions or open criticism of backsliding states. We thereby hypothesize the following:

Hypothesis 2: EPP MEPs from a national party in government at the time of the vote are less likely to vote in favour of a resolution than EPP MEPs from a national party in opposition at the time of the vote.

The rationale behind this hypothesis provokes further reflection on other potentially salient strategic motives of national parties at the European level. We posit that there are two further variables that may be relevant to our present study.

First, EPP MEPs whose national parties are in Member States that have substantial interests in common at the European level may feel the need to support any state that is directly or indirectly targeted by a resolution. The Visegrad group composed of Hungary, Poland, Slovakia, and the Czech Republic have been in a strategic coalition at the European level since they each joined the EU in 2004. Their long-standing military, economic, and cultural cooperation has even spilled over to questions of fundamental values, perhaps most exemplified by a common rejection of ‘humanitarian universalism’ in relation to the treatment of refugees (Vachudova, Reference Vachudova2020, p. 333). It is therefore worth investigating whether MEPs from these four states are any more likely than other MEPs to vote against fundamental values. Since three of the four – Poland, Hungary, and Slovakia – have each been the target of at least one EP resolution on fundamental values, it is likely that their resistance to votes of this kind will be heightened still further. We hypothesize that:

Hypothesis 3: EPP MEPs who are members of Visegrad national parties are less likely to vote in favour of a resolution than EPP MEPs from other national parties.

Second, and more generally, MEPs belonging to national parties in Member States that have reason to expect that they may become the target of resolutions in the future may be less likely to vote in favour of a resolution. They may seek to resist EU interference in domestic politics and to display solidarity with targeted states with the expectation of reciprocity in the future. States that are most likely to be concerned about being the target of an EP resolution on fundamental values are those that display lower levels of respect for the rule of law and human rights. In light of these considerations, we hypothesize that:

Hypothesis 4: EPP MEPs from countries with lower institutional performance on democratic indicators are less likely to vote in favour of a resolution than EPP MEPs from countries with higher institutional performance on democratic indicators.

It should be noted that neither Hypothesis 4 nor 5 depends on an MEP’s national party being in government. In the case of the Visegrad group, shared interests are long-standing. As such, MEPs belonging to national parties in opposition domestically may still have incentives to display solidarity with members of the group on fundamental values resolutions. In the case of poor domestic performance on democratic indicators, it is not obvious that national opposition parties would seek to encourage an interventionist approach from the EU, especially if the opposition may one day be faced with such recrimination when it is itself in power at a later date.

Strategic motives related to domestic politics

National parties influencing EPP MEPs may not be motivated solely by strategic interests at the European level. Domestic strategic interests may also play a role, with centre-right parties attempting to escape criticism from their PRR counterparts for promoting EU interventionism. From the literature on mainstream party strategies towards the PRR, for example, we know that accommodation of the PRR has been the dominant response of the centre-right in domestic electoral contexts. In a bid to limit the electoral success of these opponents, the large majority of centre-right parties in Europe have themselves shifted to the right over time (Bale, Reference Bale2003; Meguid, Reference Meguid2005; Herman and Muldoon, Reference Herman, Muldoon, Herman and Muldoon2018).Footnote 8 There are many good reasons, however, to doubt that this logic also applies to EP politics. Given the limited politicization of EP politics, there is little evidence so far that MEPs have felt the need to accommodate PRR parties at the EU level (McDonnell and Werner, Reference McDonnell and Werner2019; Meijers and van der Veer, Reference Meijers and van der Veer2019a). Furthermore, to the extent that Eurosceptical voters care most about issues such as immigration and unemployment (De Vries, Reference De Vries2018, p. 117), it may be considered very unlikely that backsliding on fundamental values would be a sufficiently prominent issue for national parties to put pressure on their MEPs.

These caveats notwithstanding, voting against sanctions might still be the safest option for a vote-seeking centrist party faced with strong competition from PRR forces. While the details of EP politics might not matter to citizens, right-wing Eurosceptics have nevertheless increasingly been able to mobilize citizens by denouncing overreach of the EU’s powers into issues that rightfully belong to the realm of national sovereignty. Any party associated with supporting novel forms of EU interventionism into how a Member State governs itself – especially given the Eurosceptical emphasis on the EU’s own purportedly weak democratic credentials – is liable to come under inflammatory criticism by the PRR. It is, therefore, still worth investigating whether the following hypothesis holds

Hypothesis 5: EPP MEPs from national parties facing higher levels of electoral competition from PRR parties are less likely to vote in favour of a resolution than EPP MEPs from national parties facing lower levels of electoral competition from PRR parties.

Constructivist motives: ideology

Finally, ideological positioning is a plausible reason for EPP MEPs either opposing or supporting resolutions on fundamental values. We know that ideology plays a key role in MEP vote choice. According to an MEP survey, 45 per cent of variance in MEP policy positions can be explained by distinct ideological preferences (Scully et al., Reference Scully, Hix and Farrell2012 p. 678). Existing studies of MEP voting on resolutions concerning fundamental values indicate that cultural conservatism as well as Euroscepticism explain inter-party variance on these issues (Meijers and Van Der Veer, Reference Meijers and Van der Veer2019b; Sedelmeier, Reference Sedelmeier2014, Reference Sedelmeier2017). We hypothesize that these two key dimensions of ideological preference also play a part in explaining intra-party variance in steering EPP MEPs’ positions on these issues. The reasoning for both expectations is as follows. In the first instance, EPP MEPs who endorse more conservative positions on cultural- and identity-related issues are also more likely to identify with backsliding states ideologically and therefore favour an accommodative position towards them. In the second case, the common Eurosceptical suspicion of overreaching European competences alluded to the above may be enough to dissuade MEPs from supporting EU actions on domestic politics. Plausibly, as Sedelmeier (Reference Sedelmeier2014 p.110) suggests, Eurosceptical representatives may hold this latter view even if they are ideologically bent against backsliding on fundamental values. We thus formulate the following two hypotheses:

Hypothesis 6: EPP MEPs from national parties with more Traditional-Authoritarian-Nationalist (TAN) ideological preferences are less likely to vote in favour of a resolution than EPP MEPs with more Green-Alternative-Libertarian (GAL) ideological preferences.

Hypothesis 7: EPP MEPs from more Eurosceptic national parties are less likely to vote in favour of a resolution than EPP MEPs with stronger pro-European ideological preferences.

Methods

Data and operationalization

To answer our third research question on the reasons for intra-EPP disagreement on fundamental values, we operationalize our independent variables as follows.Footnote 9 In order to test Hypothesis 1 relating to the defence of the EPP’s strategic interests, we include a dummy variable capturing whether the resolution directly targets an EPP member. In our sample, this only includes resolutions focusing on Hungary.

The next three hypotheses relate to the strategic defence of the national party interest at the European level. For Hypothesis 2, we include a variable which takes the value of 0 if a national party group is in opposition at the national level at the time of the vote and 1 if it is in government. To test Hypothesis 3, we include a dummy for whether an EPP MEP comes from a V4 country. For Hypothesis 4, we rely on the V-Dem dataset to operationalize the state of democracy in each Member State (Coppedge et al., Reference Coppedge, Gerring, Knutsen, Lindberg, Teorell, Altman and Ziblatt2019). In particular, we rely on the ‘Liberal Democracy’ aggregated index, which is a continuous variable ranging between 0 for low levels of liberal democracy and 1 for high levels, based on expert placements.Footnote 10

For Hypothesis 5 concerning national party strategic interests at the domestic level, we operationalize the electoral vulnerability of the EPP member party from PRRs as the vote share of the EPP member party, minus the vote share of far-right competitors in the most recent national election. Higher (positive) values thus indicate a larger advantage of an EPP member party over its PRR competitor(s). The variable is labelled ‘EPP Advantage’. We use data from the Parlgov database (Döring and Manow, Reference Döring and Manow2019) and rely on the ‘PopuList’ for the classification of parties belonging to the radical right (Rooduijn et al., Reference Rooduijn, Van Kessel, Froio, Pirro, de Lange, Halikiopoulou and Taggart2019).

Finally, we test two independent ideological variables, for which we make use of the Chapel Hill Expert Survey (Bakker et al., Reference Bakker, de Vries, Edwards, Hooghe, Jolly, Marks and Vachudova2015). For each MEP, we include their national party’s value on the GAL/TAN or ‘cultural’ left/right scale (H6), and we also use a measure of the position of the parties on European integration from the same dataset (H7). We operationalize the GAL/TAN position of a party as a dummy, which takes the value of 0 if a party’s position is smaller or equal to the mean value of 6.5 and a value of 1 if the party’s score is above that value.Footnote 11

Model

As discussed above in relation to Figure 2, the descriptive evidence shows that the share of MEPs voting in favour of a resolution broadly increases over time. In order to model this data structure adequately and to answer the substantive question of interest as closely as possible, we fit an ‘elapsed time’ conditional risk set model, in which the risk of voting for a resolution increases with time elapsed from the beginning of the period in which they are at risk (Box-Steffensmeier and Zorn, Reference Box-Steffensmeier and Zorn2002). This model is a variation of the event history model or Cox regression, which operationalizes the likelihood of an event occurring or an observation transferring to a different state as a function of elapsed time over a set of covariates.Footnote 12 We are focusing specifically on the time elapsed since 21 July 2011, as this day marks the date on which the first controversial ‘Media Authority’ Law (Act 82/100) was passed by the Hungarian Parliament. Arguably, from this day onwards, MEPs were at least implicitly under pressure to condemn fundamental values breaches. Modelling the data in this way, we are able to assess the individual determinants of EPP MEP voting at any given point in time, and thus the factors that make it more likely that they ‘switch’ their vote from a negative to a positive one over time.

In Table 1 below, we fit four different models: Model 1 contains the resolution-related variable (H1) and other variables relating to the interests of the national parties at the EU level (H2, H3, and H4). Model 2 adds the variable relating to the vote-seeking goals of national parties at the domestic level, namely the difference between the vote share of the EPP member parties and their right-wing competitors (H5). Model 3 contains the first set of variables relating to the resolutions and the EU level interest of national parties (those in Model 1), as well as the ideological factors, specifically the GAL/TAN and EU position of the national party group (H6 and H7). Model 4 is the full model, containing all variables. In Appendix 2, we include all four models excluding the votes by Fidesz EPP MEPs, but our results do not seem to be sensitive to this exclusion.

Table 1. Results of the conditional risk set model

Hazard ratios; standard errors in parentheses.

* p < .1, ** p < .05, *** p < .01.

Findings

We now turn to the results of our regression analysis, displayed in Table 1. The results of the conditional risk set model are displayed as hazard ratios, indicating the increase in the ‘risk’ of voting for a resolution associated with a change in the respective variable. Values below 1 indicated a lower risk of voting in favour of a resolution, and values above 1 a higher risk. The results confirm that EPP MEPs are significantly more likely to vote against a resolution if it targets an EPP member, here Fidesz. These results confirm H1 and therefore lends further credence to the ‘strategic EPG hypothesis’ according to which EPP votes on fundamental values violations can be explained by their willingness to protect members of their EPG against sanctions. Throughout the models, EPP MEPs are around 20% less likely to vote for a resolution if it targets Hungary, demonstrating a strong unwillingness to ‘call out’ a member party.

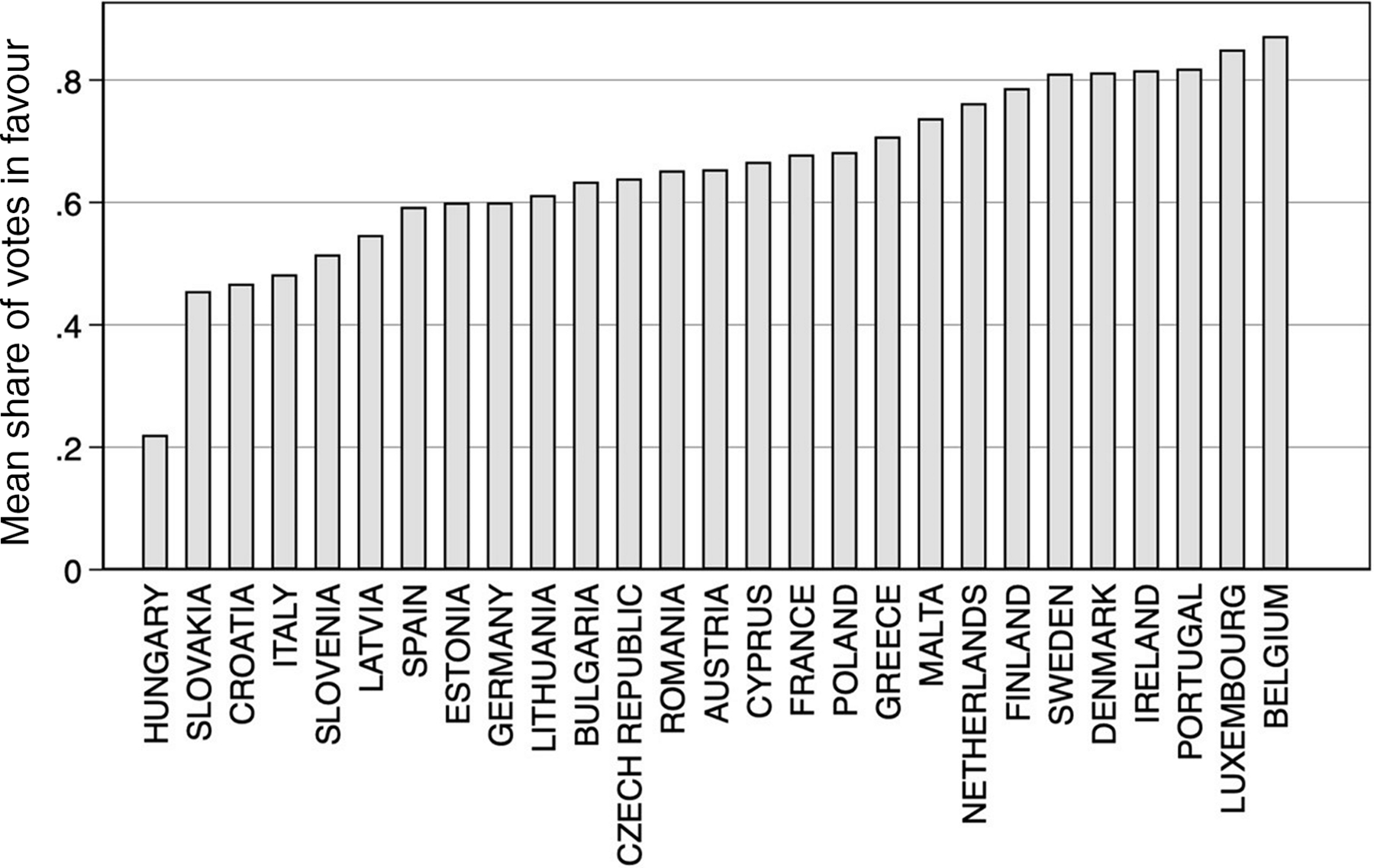

The regression analysis confirms that EPP MEPs with national parties in government (H2) are less likely to vote in favour of resolutions. Parties in government are approximately 20% less at risk to vote for a resolution, as indicated by the hazard ratios. Thus, out of every five resolutions opposition parties vote in favour of, government parties vote against one. A glance at the data shows important disparities in the position of MEPs from different Member States (Figure 3). As Figure 3 shows, there is significant variation between countries with regard to the extent to which EPP MEPs on average vote for a resolution. Indeed, MEPs from the V4 countries seem to be less likely to vote in favour of the resolutions, lending conditional support to Hypothesis 3. In the full model (Model 4), the V4 variable is significant at the 0.01 level. MEPs from the V4 countries are thus approximately 27% less likely to vote for a resolution. We also find an effect for the quality of democracy in the MEP’s home countries (H4). In Model 4, a full-scale change on the V-Dem index increases the likelihood of an MEP from the respective country voting in favour of a resolution by a factor of four. With H2, H3, and H4 confirmed, it appears that EPP MEPs indeed have other strategic reasons to support backsliding states pertaining to the status of their national party in the EU.

Figure 3. Average share of votes in favour for all resolutions, by nationality of EPP MEPs.

The national electoral context seems to have only a minor effect. The closeness of the domestic electoral competition between the EPP member party and its far-right competitors is significant in the full model, but its substantive effect is negative (thus not in the expected direction) and very small. We therefore find no evidence for H5. However, we find clear support for both of our ideological hypotheses, H6 and H7. As expected, the more authoritarian/traditionalist the MEP’s party is, the less likely they are to vote in favour of a resolution, lending support for H7. Substantively, parties with an authoritarian position on the GAL-TAN scale are around 30% less likely to vote for a resolution than parties with liberal values. Finally, we find a strong positive effect for the EU position of the domestic party, whereby EPP MEPs from less Eurosceptic parties are more supportive of the resolutions under study. A unit increase in party support for the EU is associated with an increase of around 25% in the likelihood of voting for a resolution. These findings are consistent with previous studies, confirming that constructivist factors have an important role to play in predicting EPP MEPs’ voting behaviour on fundamental values.

Discussion and conclusion

In this paper, we have sought to investigate three questions. First, we attempted to understand the nature of cohesion within the EPP on votes relating to fundamental values. We found that compared to the average overall vote cohesion within the EPP – and indeed the vote cohesion on issues pertaining to the policy field of Justice and Civil Liberties – the EPP was far more divided on resolutions concerning fundamental values. Second, with our longitudinal dataset, we were able to explore how the position of EPP MEPs evolved over time on questions of fundamental values. We found that on resolutions targeted at Hungary, and indeed all other resolutions on fundamental values, EPP MEPs became more likely over time to vote in favour of sanctions. These findings in pursuit of our first two questions problematize the tendency to treat the EPP as a monolithic voting bloc, driven primarily by its own strategic interests. If questions of fundamental values are polarizing for the EPP, and if the EPP has gradually shifted from an accommodative to a confrontational stance over time on issues of this kind, then it is necessary to consider all possible variables that may explain the original discord and its development over time. This was the nature of our third research question, namely to investigate the determinants of individual voting behaviour on fundamental values within the EPP. Building on existing literature analysing inter-party voting behaviour differences on fundamental values in the EP, as well as literature pertaining to political competition in the EP and on conservative responses to the PRR domestically, we generated some familiar and novel hypotheses to attempt to understand the drivers of intra-party voting variation within the EPP on questions of fundamental values. These hypotheses covered strategic and constructivist variables.

On the strategic side, we verified one of the key findings in the literature on EPG voting behaviour on fundamental values: the EPP has protected Fidesz in order to safeguard Hungarian votes in its ranks, and thus the strategic, office, and policy-seeking interests of the conservative EPG. Our findings also reinforce what we already know about voting behaviour in the EP more generally: MEPs have two main principals and look out for the strategic interests of both their EPG and their national party. The fact that MEPs are more likely to oppose sanctions when their party is in government at the national level suggests they are willing to protect the capacity of their national organizations to form alliances with backsliding states within the EU’s intergovernmental institutions.

We also tested whether the strategic interests of national parties at the domestic level may impact MEP voting behaviour. It appears that domestic electoral pressure from the PRR does not play a significant role in influencing MEPs to vote against sanctions on fundamental values. This is consistent with the more general finding in the literature on political competition in the EP, which finds that EPGs have not significantly shifted their policy positions in light of Eurosceptical challenges (McDonnell and Werner, Reference McDonnell and Werner2019; Meijers and van der Veer, Reference Meijers and van der Veer2019a). The possibility that support for EU sanctions on Member States could be portrayed domestically by the PRR as centre-right support for an overbearing EU does not seem to factor much into MEPs’ considerations.

Two other strategic variables, however, appear to play a role in explaining EPP MEPs’ voting behaviour on fundamental values. First, MEPs from the Visegrad countries are less likely to vote for sanctions than other MEPs. This is an intriguing finding when we consider that, among Visegrad countries, only Hungary had a governing party within the EPP continuously, for the entire period covered by this study. Plausibly, even parties who are in opposition domestically within the EPP see the long-term strategic interests of their nation as bound up with the other Visegrad countries and so are reluctant to take a stand against them on fundamental issues. Finally, we found that being from a Member State that performs less well on democratic indicators will make an MEP less likely to vote in favour of sanctions. We have categorized this finding as most likely to have a strategic explanation. Essentially, MEPs from Member States with lower democratic performance may be concerned about becoming targets of resolutions in the future. They may therefore seek to render the process ineffective by voting against resolutions, or else they may wish to demonstrate solidarity with targeted Member States to secure reciprocity in the future. We should not, however, discount the possibility of a constructivist explanation behind this finding. It is possible that MEPs from Member States with a lower democratic performance are less attached to fundamental values than other MEPs and are thereby less willing to make a fuss over their protection.

By widening out the potential strategic variables that have influenced EPP voting behaviour over time on resolutions concerning fundamental values, we have added complexity to existing accounts. However, we have not neglected the importance of constructivist variables in adding further complexity. What we find corroborates previous accounts.

As expected, both Euroscepticism and an authoritarian positioning of an MEP’s national party on the GAL/TAN axis are strong predictors of opposition to the EP resolutions under study. An unexpected finding within our descriptive statistics on MEP voting behaviour by country lends further credence to these ideological factors. Across EPP MEPs from all Member States, we find a sharp dip in support for fundamental values resolutions in 2015, following the onset of the Syrian refugee crisis (see Appendix 6). Indeed, the Hungarian Government was strongly opposed to the influx of asylum seekers, criticizing the welcoming approach of German chancellor Merkel, and ordering the construction of a fortified fence at its southern border (Csehi and Zgut, Reference Csehi and Zgut2020). This decision, in turn, was criticized by a number of Member State governments. However, it also triggered support from right-wing parties, as well as some members of the EPP. There are therefore grounds to link EPP MEPs’ implicit backing of Fidesz’s tough stance at the time and their unwillingness to promote sanctions against illiberal backsliding in the EU. Based on our results, we can cautiously suggest that EPP MEPs do not simply support Fidesz because they have self-interested reasons for doing so, but because they share some of the principles that Fidesz claims to defend.

On the basis of these findings, we achieve a better appreciation of the ways in which party politics can either help or hinder the defence of fundamental values in the EU. Undoubtedly, the EPP’s opposition is one of the key reasons for the EU’s long period of inaction against fundamental values violations in Hungary. Conversely, the party group’s change of heart since September 2018 has removed a major obstacle to further sanctions in this particular case. How this change has taken place, and what role intra-party disagreement has had in bringing it about, has wider implications for understanding the conditions under which the EU can be expected to act against backsliding on fundamental values in the future. In this regard, we offer three general concluding points.

First, our results suggest that the standard cost–benefit explanation for why the EPP moved from an accommodative to a confrontational stance regarding Fidesz must be broadened to include certain non-EPG strategic interests and constructivist motivations. While the EPG’s changing strategic interests are likely to influence the position of all EPP MEP’s similarly over time, the cost–benefit analysis for each individual MEP varies widely on the basis of other factors. For example, given the ideological sacrifice, it is significantly costlier for an MEP falling at the GAL end of the ideological spectrum to protect Fidesz for strategic reasons than it is for an MEP who subscribes to TAN values. As such, when the EPG strategic reasons for protecting Fidesz begin to weaken for all EPP MEPs, this is likely to have a bigger and more immediate impact on the voting behaviour of liberal leaning politicians over time. For politicians who have consistently supported EP sanctions since 2010, or opposed them as late as September 2018, the weight of ideological factors would appear to be paramount, trumping EPG strategic considerations. Different strategic and ideological calculi will also need to be made depending on whether an MEP is from a Visegard Member State or a Member State with low democratic performance, or whether their national party is in government at the time of a vote.

Second, with good reason, this and other studies have explored the EPP as a case for understanding EP inaction on questions of fundamental values. As the EU’s quintessential democratic body, the EP’s reluctance to stand united and firmly against backsliding on fundamental values is an intriguing and important object of study. Yet, as our results suggests, intergovernmental logics go a long way towards explaining the EPP’s behaviour, which has until now mostly been analysed as a partisan response. It is widely recognized that individual governments and the collectives of the Council and European Council have been insipid in their response to backsliding states. The contrasting approaches of the Council and the Commission in exerting social pressure on backsliding states lends credence to this perspective (Sedelmeier Reference Sedelmeier2017; Pech and Scheppele Reference Pech and Scheppele2017). As Sedelmeier (Reference Sedelmeier2017) explains, the Commission has been able to target backsliding states individually and in a public fashion through its development and use of the Rule of Law Framework. This is conspicuously different than the Council’s best effort, namely the Rule of Law Dialogues, which does not directly target individual Member States, but instead takes on a light-touch thematic focus in their annual discussions. The lack of open criticism by members of national governments across Europe against specific Member States on the issue of backsliding (Blauberger & Kelemen, Reference Blauberger and Kelemen2017, p. 332) only reinforces the point. To this extent, the respective dynamics explaining the lack of action within the intergovernmental institutions of the EU and the EP might not be so distinct. Rather, the constraints facing the Council and the European Council seem to bleed into the EP, to the extent that EPP MEPs are influenced by the strategic interests of their national parties at the European level when these parties are in government.

Finally, by looking at the evolution of EPP MEPs’ voting behaviour on these issues over time, we have seen that there is a slide from an accommodating tendency to a more confrontational tendency. Two, non-exclusive processes might be at play here. First, if we take a strategic perspective and assume the predominance of EPG strategic interests, then it may be the case that the EPG’s strategic interests have changed over time: the benefits of Hungarian membership fell while the costs rose, thereby depriving the EPG of its key reasons for protecting Fidesz. In the past decade, Fidesz has indeed not been the most loyal. For instance, it opposed the EPP party line in September 2015 by voting down the Commission’s proposal for the relocation of refugees throughout the Union (VoteWatch, 2016) and, in June 2014, Viktor Orbàn also voted against the EPP’s official candidate for the European Commission Presidency, Jean-Claude Juncker, in the European Council. In parallel, the fact that the situation with regard to fundamental values has continued to deteriorate in Hungary over the EP’s past two terms – and that breaches have multiplied in other EU countries such as Poland, Romania, Slovakia, Malta, or Bulgaria – might have rendered systematic opposition to EU intervention untenable. In other words, the deteriorating situation may have made it harder for EPP MEPs to publicly deny the problem, while preserving their reputation within the EP and avoiding tensions with the S&D and Renew Europe (formerly ALDE) groups. If strategic factors are the driving force behind the change within the EPP, then we may strike an optimistic note: just as strategic interests may be an obstacle to protecting fundamental values, they can also come to enable action.

Second, beyond these strategic concerns, there may also be constructivist factors at play. Simply, a process of political learning may have been taking place within the EPP, where the accumulation of evidence on backsliding and arguments in favour of taking a stand have progressively convinced conservative MEPs to support sanctions. In 2012, EPP MEPs might have genuinely believed that claims about democratic backsliding in Hungary coming from political opponents were overstated and politically motivated. In 2018, it becomes far harder to minimize the significance of Fidesz’s breaches or to see the Hungarian situation as an isolated case. Further research using qualitative analysis of debates on fundamental values and direct engagement with MEPs could serve to disentangle the respective role of strategic calculations and deeper forms of political learning in motivating EPP MEPs to support sanctions against fundamental values breaches from members of their own group.

As a concluding reflection, the importance of ideological factors in influencing voting behaviour on fundamental values is cause for concern, as it may prove to be a far more resilient obstacle to partisan action against fundamental values violations than strategic interests. While incentives can evolve over time and push rational actors towards a change of course, principled positions are far more rigid. There are also few reasons to believe that conservative parties in the EP will become any more liberal over time: in the past few decades, most centre-right parties in Europe have shifted to the right on the GAL/TAN axis, avowedly to keep up with increasingly popular radical right parties (Bale, Reference Bale2003; Wagner & Meyer, Reference Wagner and Meyer2016; Herman and Muldoon, Reference Herman, Muldoon, Herman and Muldoon2018). Right-wing authoritarianism may thus not only prove one of the key drivers of democratic backsliding within certain EU Member States, but also one of the main stumbling blocks for EU action against such backsliding in the future.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1755773921000023.

Acknowledgements

For their helpful comments, the authors would like to thank participants at the workshop on ‘Democratic Backsliding in Europe’, organized at Sciences Po, Paris in December 2019, at the seminar series of the School of Politics and International Relations, University College Dublin in January 2020 and at the reading group on ‘Democracy and Justice in the EU’ of the Politics Department, University of Exeter in February 2020. The authors would also like to thank four anonymous referees for detailed comments that helped them improve the article substantially.