Introduction

Today's radical right is said to be ‘right-wing’ due to its nationalistic, authoritative, anti-cosmopolitan, and especially anti-immigrant views. The economic placement of the radical right is, however, debated. While earlier works point to neo-liberal stances of radical right parties, studies of the social bases of these parties point to significant support from traditionally left-leaning constituencies. Recent scholarship argues that radical right parties abandoned their outlying economic positions and shifted closer toward the economic center (Kitschelt, Reference Kitschelt2004; De Lange, Reference de Lange2007).

This article, however, questions the utility of assessing radical right party placement on economic issues. It suggests that politics is a larger struggle over the issue content of political competition. Political parties are invested in different issue dimensions, and thus prefer competing on some issues over others. Consequently, parties emphasize their stance on some issue dimensions, while strategically evading positioning on others, in order to mask the distances between themselves and their voters. This article argues that parties, such as the radical right, may successfully adopt a strategy of deliberate position blurring. In light of such competition, taking a position may be neither an appropriate party strategy, nor an adequate academic expectation.

This argument underlines the limits of spatial theory in capturing party competition. While spatial theory conceptualizes political competition as position taking, this article underlines the strategic utility of position avoiding or position blurring. This dimensional approach to political competition considers issue positioning, issue salience, and strategic positional avoidance in a multidimensional context. This approach explains the apparent variance of radical right economic placement as an outcome of these parties’ conscious dimensional strategizing – of deliberate position blurring.

This article combines quantitative analyses of electoral manifestos, expert placement of political parties, and voter preferences based on multiple public opinion surveys. It considers 17 radical right parties in nine Western European party systems. I first review the literature on radical right ideological placement. The second section introduces a dimensional approach to party competition, detailing general party strategies in multidimensional contexts, while generating specific hypotheses about the radical right. The third section discusses the data and operationalization. The fourth section presents the analyses and results, while the final section serves as a conclusion.

Where do radical right parties stand?

Scholarship on radical right parties agrees on many of their ideological characteristics. It suggests that radical right parties rely on emotive appeals to national sentiments defined in ethnic terms; reject cosmopolitan conceptions of society; react to rising non-European immigration; oppose globalization and reject European integration which they see as undermining national sovereignty and identity; and brand themselves as anti-parties, criticizing domestic political elites as corrupt and removed from the ‘common people’ (see Betz, Reference Betz1994; Kitschelt and McGann, Reference Kitschelt and McGann1995; Taggart, Reference Taggart1995; Mudde, Reference Mudde1996; Hainsworth, Reference Hainsworth2000, Reference Hainsworth2007; Hooghe et al., Reference Hooghe, Marks and Wilson2002; Kriesi et al., Reference Kriesi, Grande, Lachat, Dolezal, Bornschier and Frey2008). Rydgren (Reference Rydgren2005) argues that the rise and success of the radical right is associated with the development and diffusion of effective ideological ‘master frames’. The frame, pioneered by the French Front National in the 1970s and 1980s, combines ethno-nationalism and populist anti-establishment rhetoric, without being overtly racist or anti-democratic. It infuses the previously marginalized radical right with a potent ideological model, allowing it to “free itself from enough stigma to be able to attract [new] voters” (Rydgren, Reference Rydgren2005: 416).

This frame, however, says little about radical right economic positions. The rise of radical right parties in Western Europe is associated with a backlash against the ‘excessive role of the state’ in the economy, and the power of labor unions (Ignazi, Reference Ignazi2003). Earlier literature suggests that radical right parties present a “classical liberal position on the individual and the economy” (Betz, Reference Betz1994: 4). Kitschelt and McGann suggest that the radical right must adopt a ‘winning formula’ consisting of authoritarian and nationalistic social appeal coupled with extreme neo-liberalism, “calling for the dismantling of public bureaucracies and the welfare state,” demanding a “strong and authoritarian, but small” state (1995: 19 and 20; McGann and Kitschelt, Reference McGann and Kitschelt2005).

Recent literature considering the social bases of radical right support, however, underscores the cross-class character of radical right voters. Evans (Reference Evans2005: 92) finds that radical right parties attract both self-employed and manual workers, and that continental radical right parties also increasingly attract routine non-manual workers, further diversifying the radical right class base. Ivarsflaten (Reference Ivarsflaten2005: 490) shows that the self-employed and manual worker supporters of the radical right hold significantly different views on the economy, pointing to the radical right “electorates’ deep division over taxes, welfare provisions and the desirable size of the public sector”. Similarly, Kriesi et al. (Reference Kriesi, Grande, Lachat, Dolezal, Bornschier and Frey2008) argue that radical right parties represent disparate ‘losers’ of globalization.Footnote 1 Due to declining identification with workers’ parties and organizations, manual workers are likely to consider more electoral choices, not necessarily solely on the basis of their economic views, but also on the basis of their authoritarian tendencies (Bjørklund and Andersen, Reference Bjørklund and Andersen1999).

Then how do radical right parties respond to the diverse economic interests among their ranks? Mudde underlines the increasing orientation toward social market economy in radical right party literature, bringing these parties’ positions close to Christian democratic parties, or even the social democratic ‘third-way’ (2007: 124). Derks (Reference Derks2006) suggests that in order to capture disenchanted industrial workers hurt by globalization, post-industrial society and the supply of cheaper immigrant labor, radical right parties use a mix of egalitarianism and anti-welfare chauvinism. Similarly, Kitschelt's (Reference Kitschelt2004: 10) recent work reflecting on the radical right constituency's division over economic policies, moderates his ‘winning formula’. He claims that radical right parties may not be on the extreme economic right, but rather on the “market-liberal side of the political spectrum” – a stance demonstrated by the few radical right parties which have attained executive office (Kitschelt, Reference Kitschelt2007: 1183). Testing Kitschelt's restated ‘winning formula’ on three cases, De Lange (Reference de Lange2007) empirically supports the claim that radical right parties have shifted their position to the economic center.

This conceptual approach suggests that radical right parties hold discernible positions on major ideological dimensions. In fact, the study of the radical right – in line with the scholarship on political parties and actors in general – uses spatial conceptions to account for party and voter placement. Kitschelt and McGann (Reference Kitschelt and McGann1995), McGann and Kitschelt (Reference McGann and Kitschelt2005) and Kitschelt (Reference Kitschelt2007) analyze the ideal stance of radical right parties in the form of the ‘winning formula’. Van der Brug et al. (Reference Van der Brug, Fennema and Tillie2005) explain radical right electoral success using party evaluations based on spatial proximity measures. Bjørklund and Andersen (Reference Bjørklund and Andersen1999) suggest that radical right voters in Scandinavia are positioned between the major left- and right-wing parties on economic issues. Ivarsflaten (Reference Ivarsflaten2005) emphasizes the vulnerability of radical right parties, given the spatial differences among their voters on economic issues. Finally, Rydgren (Reference Rydgren2005: 418) notes that radical right success starts with spatial electoral niches where there are “gaps between the voters’ location in the political space and the perceived position of the parties” .Footnote 2

Spatial theory provides a classical understanding of political competition by conceptualizing it as spanning continuous issue scales, simplified into issue dimensions (Hotelling, Reference Hotelling1929; Downs, Reference Downs1957).Footnote 3 Parties take positions within this dimensional structure in response to voter distributions. For spatial theory, the dimensional structure of political space is an assumed context within which competition occurs. Consequently, the spatial tradition sees competition as a contest over party positioning with respect to voters, who minimize the aggregate distance between themselves and the party they vote for in n-dimensional space.

The application of spatial theory to radical right party study has been modified importantly by Meguid (Reference Meguid2005, Reference Meguid2008). While utilizing spatial representation of competition among mainstream parties and radical right parties, Meguid considers not only party positioning, but also issue salience and issue ownership. This leads her to formulate a strategic game in which radical right parties present new political issues into political discourse, and mainstream parties choose to engage or dismiss these issues, thus either boosting or lowering their salience (2008: 28). This broadens the spatial conception of political competition by showing how issue salience allows strategic interaction between parties that are not spatial neighbors.

Meguid's work highlights how the inclusion of issue salience and ownership opens new strategic possibilities in party competition. Its implications are, however, even more profound. When political actors invest salience into new cross-cutting political issues, they are introducing new issue dimensions and redefining the political space where competition occurs. Under these conditions, parties are likely to be invested more in some dimensions than others. Although they are likely to take clear positions on the dimensions of their primary interest, it may be logical for them to avoid taking clear stances on the dimensions in which they are not invested. Taking positions may thus be an inappropriate strategy in the context of multidimensional competition – and consequently, its study. Thus, the question ‘where radical right parties stand’ may not be the right one to ask. The next section turns to an analysis of the implications of multidimensional party competition in greater detail.

Dimensional approach

The dimensional approach to competition introduced by this article is based on two core premises. First, the structure of political competition is not merely a fixed stage, but rather is itself the subject of competition. This approach understands political competition as a contest over the presence and bundling of political issues into various issue dimensions. Competition is then a contest over which issues or issue dimensions dominate political discourse and voter decision-making. Political parties thus do not only take positions on issue dimensions, they actively seek to alter the structure of competition to their advantage by manipulating these issues.

The second premise of the dimensional approach is that parties do not merely respond to voter preferences by taking positions, but that they also seek to affect voters’ choices through emphasizing certain issues in political campaigns. This is borrowed from issue ownership and salience theory (Budge and Farlie, Reference Budge and Farlie1983; Budge et al., Reference Budge, Robertson and Hearl1987; Petrocik, Reference Petrocik1996), which argues that parties strategically increase the salience of those issues on which they hold advantaged positions, while trying to mute issues somehow harmful to them. The relationship between voter preferences and party strategies is thus more complex than that spatial theory suggests. Parties may on the one hand fill popular niches by championing publicly salient, but politically untapped issues. On the other hand, parties may affect the popular salience of issues by either emphasizing or ignoring them.Footnote 4

The dimensional approach points to two theoretically separate party strategies – issue introduction and position blurring. First, as originally formulated in Riker's (Reference Riker1982, Reference Riker1986)heresthetics, political parties tactically alter political competition by introducing novel issues into political discourse (see also Budge et al., Reference Budge, Robertson and Hearl1987; Carmines and Stimson, Reference Carmines and Stimson1989; Rabinowitz and Macdonald, Reference Rabinowitz and Macdonald1989; MacDonald et al., Reference MacDonald, Listhaug and Rabinowitz1991). Introducing a new issue may produce a new dimension of political conflict and create a competitive niche for its protagonist, particularly if the issue does not naturally fold into the standing structure of competition. A party may also wish to introduce a new issue on which it is likely to be viewed favorably. Finally, a party may choose to introduce a new political issue with the aim of creating tensions within competing parties, thus weakening them.

Second, political parties may strategically avoid stances on some dimensions of multidimensional political conflict, and engage in what this article terms position blurring. Since political parties may have different stakes in different issue dimensions, they may not simply mute the salience of issues secondary to them. Rather, parties may attempt to project vague, contradictory or ambiguous positions on these issues. The aim of the strategy is to mask a party's spatial distance from voters in order to either attract broader support, or at least not deter voters on these issues. Position blurring is unlikely to be a successful strategy if applied on all issues. However, in the context of competing along one or few issue dimensions, blurring positions on other dimensions may be beneficial.

This is a contradictory expectation to the ‘obfuscation’ literature in American politics, which almost invariably concludes on both formal and empirical grounds that taking ambiguous positions is a costly strategy (Shepsle, Reference Shepsle1972; Enelow and Hinich, Reference Enelow and Hinich1981; Bartels, Reference Bartels1986; Franklin, Reference Franklin1991; Alvarez, Reference Alvarez1998). This literature, however, considers uni-dimensional competition. Blurring positions on a unique dimension of conflict is a profoundly different situation to blurring positions on some dimensions, while presenting clear stances on others. Position blurring on some dimensions may be a rational strategy in the context of multidimensional issue competition.

Position blurring may take on different forms. First, parties may avoid presenting a stance all together. More frequently, parties may present vague or contradictory positions on a given issue dimension. Mudde (Reference Mudde2007: 127) reports, for example, that many radical right parties mix appeals for low taxation and privatization with economic protectionism, particularly in the agricultural sector. This ideological profile combines stances which are not usually connected, as most parties associate low taxation and privatization with economic liberalism. Misaligning stances on issues commonly attached to a unique dimension allows parties to blur their general dimensional positioning, while giving them the opportunity to present different voters with contradictory programs. Position blurring can thus appear as either a lack of a position, as concurrent multiplicity of positions, or as positional instability over time.

The strategies stemming from dimensional competition carry different costs. The parties facing higher costs to issue introduction and position blurring are likely to be established political parties with long-standing histories, organizational apparatuses, core constituencies, and well-entrenched ideological images. They are likely to face organizational and ideological barriers to shifting political salience to new issues and blurring their positions on others. Established, mainstream parties are likely to find it harder to convince their membership and core constituents of the merits of adopting new issues and obscuring their positions on old ones. Their ideological heritage is likely connected with the historical development of social cleavages in their polity (see Lipset and Rokkan, Reference Lipset and Rokkan1967). This means that their political stance is known and entrenched, and their appeal stickier. Consequently, blurring positions on secondary issues may be futile and new issue introduction may spark crippling divisions.

On the contrary, radical right parties are less constrained in new issue introduction and position blurring. They entered European party systems in recent decades as outsiders ostracized by political elites. Furthermore, they have centralized, hierarchical organizational structures that favor top-down decision-making patterns (Heinisch, Reference Heinisch2003). This gives them organizational facility in strategically contesting the dimensional structure of party competition.

Moreover, radical right parties face an electoral incentive for employing these dimensional strategies. As the literature on radical right social bases suggests, there is a dimensional discrepancy to radical right support. Radical right voters share an ideological affinity on non-economic, socio-cultural issues, such as immigration or law and order, while they are divided over the economy. This argument implies that radical right voters have different preference distributions across issue dimensions. This leads to the following hypotheses.

Hypothesis 1: Radical right voters hold significantly more dispersed economic positions than major party supporters, while being less dispersed on non-economic, socio-cultural issues.

Consequently, radical right parties face different stakes in different issue dimensions. They are induced to compete on non-economic, socio-cultural issues by overemphasizing them in their discourse.

Hypothesis 2: While major parties place comparable emphasis on both non-economic and economic issues, radical right parties overemphasize non-economic issues, while muting economic issues.

This article argues that while competing on the non-economic dimension, radical right parties do not merely deemphasize economic issues. In order not to deter supporters with divergent economic outlooks, radical right parties also present blurred stances on the economic dimension. The positional ambiguity of radical right parties on the economy can be analyzed across data sources, across party types and over time:

Hypothesis 3a: The assessment of radical right party positions on economic issues significantly diverges across data sources, while the evaluation of their non-economic positions is largely consistent.

Hypothesis 3b: Voters and experts are significantly less certain about radical right party placement on economic issues than about the economic placement of other party types.

Hypothesis 3c: The assessment of radical right party positions on economic issues manifests significantly greater fluctuation over time than that of major parties.

The strategic increase in non-economic issue salience combined with position blurring on the economic dimension on the part of the radical right is likely to have positive electoral effects. By shifting emphasis toward their preferred issue dimension and distorting their economic stances, radical right parties attract their voters on the basis of non-economic, rather than economic issue considerations.

Hypothesis 4: While voters consider both economic and non-economic issues when voting for major parties, they consider primarily non-economic (and not economic) issues when supporting the radical right.

Despite its benefits, position blurring has its limitations. Upon entering government, parties become responsible for implementing explicit policies, which circumscribes their ability to present vague or multiple positions, and forces them to take clear stances. Furthermore, parties with ambiguous views who succeed in entering government may face public embarrassment. The fate of some radical right parties, particularly the Austrian Freiheitliche Partei Österreichs (FPÖ), which lost substantial public support after entering governments, underlines this point (Heinisch, Reference Heinisch2003; Luther, Reference Luther2003; Fallend, Reference Fallend2004). Although an effective strategy in opposition, position blurring becomes a liability in government.

Hypothesis 5: Government participation limits position blurring of radical right parties.

Data and operationalization

This article limits itself to contemporary (early to mid 2000s) Western Europe, where scholars argue the political space can be depicted in two dimensions.Footnote 5 The first dimension relates to economics, ranging from state-directed redistribution to market allocation. The second dimension relates to non-economic, socio-cultural issues, concerning such factors as lifestyle choice, national identity, immigration, and religious values, and it ranges from socially liberal, alternative politics to socially conservative and traditional politics (Kitschelt, Reference Kitschelt1992, Reference Kitschelt2004; Laver and Hunt, Reference Laver and Hunt1992; Hooghe et al., Reference Hooghe, Marks and Wilson2002; Benoit and Laver, Reference Benoit and Laver2006; Marks et al., Reference Marks, Hooghe, Nelson and Edwards2006; Vachudova and Hooghe, Reference Vachudova and Hooghe2009). Since the second dimension tends to be more complex and loosely structured, this article refers to it simply as the non-economic dimension (Rovny and Marks, Reference Rovny and Marks2011).

To locate parties on these dimensions, this article uses the 1999, 2002, and 2006 Chapel Hill Expert Surveys (CHES), which place parties on an economic left–right scale and on green, alternative, and liberal vs. traditional, authoritarian, and nationalist policies (Steenbergen and Marks, Reference Steenbergen and Marks2007; Hooghe et al., Reference Hooghe, Bakker, Brigevich, De Vries, Edwards, Marks, Rovny, Steenbergen and Vachudova2010). In order to test hypotheses 1 and 4, concerning voter preferences, the article utilizes the European Social Survey, 2006 (ESS).Footnote 6 To test hypothesis 2, concerning the salience parties attach to different issues, the article uses the Comparative Manifesto Project (CMP) data set (Budge et al., Reference Budge, Robertson and Hearl1987; Volkens et al., 2011). Table A2 in the Appendix lists the CMP categories that were used to construct an additive measure of salience for the economic and the non-economic dimensions. To test hypotheses 3a, 3b and 3c, concerning issue position blurring, the article combines four public opinion surveys: the World Values Surveys, 1999–2000 (WVS), the 2004 European Election Study (EES), the International Social Survey Program (ISSP), 2006, and the ESS, 2006.Footnote 7 It also assesses the long-term positional stability of parties using the CHES data sets. The CHES data set also provides a basis for testing hypothesis 5 concerning the effects of government participation.

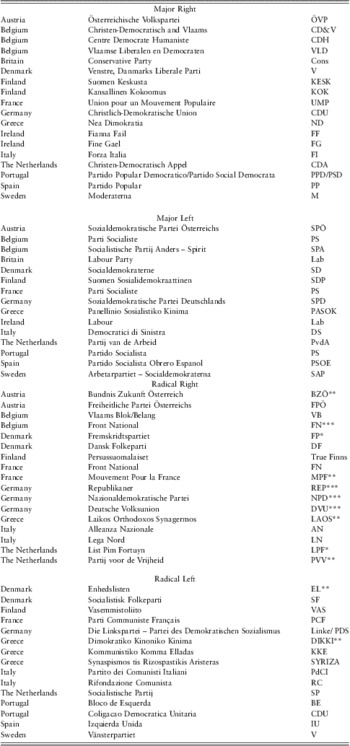

The article considers all Western European parties generally referred to as radical right, populist right, extreme right, or neo-fascist by the party literature (cf. Golder, Reference Golder2003; Norris, Reference Norris2005; Kitschelt, Reference Kitschelt2007). The case selection is, however, constrained by the data.Footnote 8 Consequently, the article is limited to the study of 17 radical right parties in nine countries. These are: FPÖ and Bündnis Zukunft Österreich (BZÖ) in Austria; Front National (FN) and Vlaams Blok/Belang (VB) in Belgium; Fremskridtspartiet (FP) and Dansk Folkeparti (DF) in Denmark; True Finns in Finland; Front National (FN) and Mouvement pour la France (MPF) in France; Die Republikaner (REP), Nationaldemokratische Partei Deutschlands (NPD) and Deutsche Volksunion (DVU) in Germany; Laikós Orthódoxos Synagermós (LAOS) in Greece; Alleanza Nazionale (AN) and Lega Nord (LN) in Italy; and Lijst Pim Fortuyn (LPF) and Partij voor de Vrijheid (PVV) in the Netherlands. Table A3 in the Appendix contains the details.

Major parties are operationalized as the most significant political parties on either side of the left–right spectrum in each party system. These parties are either the primary governing parties or the main opposition parties. In cases where more parties can be considered as major right or major left parties, all such parties are included. See Table A3 in the Appendix for details.

Finally, it should be stressed that each analysis considering party placement variance measures voter or expert deviations from party-specific means. Consequently, the natural differences between party positions are removed from the analyses.

Analyses and results

Radical right voters and issue dimensions

This section tests hypothesis 1, showing that radical right voter preferences are highly dispersed on the economic dimension, compared to the preferences of major party supporters. Simultaneously, radical right voter positions are significantly more compact on the non-economic dimension, as compared to major party voters. Table 1 presents a summary of party-specific standard deviations of radical right and major party supporters on the two dimensions. It considers each voter's deviation from party-specific mean voters, thus removing the differences in individual party placements. This analysis utilizes the ESS, 2006 survey because it provides data on both the economic and non-economic dimensions and it is contemporaneous with the CHES 2006 data used later.

Table 1 Variance ratio tests of voter positions

Variance ratio test of voter placement. Measures voter deviations from party-specific mean voters over radical right and major parties (European Social Survey, 2006).

The statistics in Table 1 suggest that radical right voters have a greater variance around their party's mean voter on economic issues. The variance ratio test shows that this variance is significantly greater than those of either the major right or major left parties. The radical right voter dispersion on the non-economic dimension is significantly smaller than that of major left parties, and almost identical to that of major right parties. Hypothesis 1 is thus supported with the caveat that radical right and major right supporters have the same dispersion on non-economic issues.

The causal order between the radical right voter and party positioning is unclear. It is difficult to say whether some voters support radical right parties because of the parties’ clear non-economic stances and vague economic stances, or whether radical right parties adjust their stances to fit these voter distributions. However, given these distributions of radical right supporters, there exists a political niche combining authoritarian positions on non-economic issues with a broad and dispersed economic placement, allowing the capture of wider economic constituencies. The next sections consider how radical right parties behave in light of this electoral niche.

Radical right parties and issue salience

Testing hypothesis 2, this section suggests that rather than contesting the entrenched issues of political competition, radical right parties highlight nationalism, ethnocentrism, and general opposition to the political establishment. Their main issue domain thus lies not on the primary, economic dimension, but on the secondary, non-economic dimension.

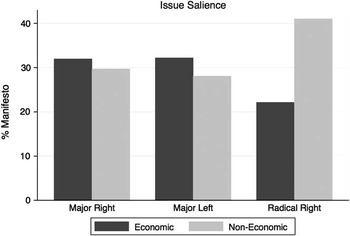

Confirming hypothesis 2, Figure 1 compares the salience that radical right parties place on economic and non-economic issues with major right and major left parties. Major parties devote about 30% of their manifestos to economic as well as to non-economic issues. They tend to slightly overemphasize economic issues, which is logical given the central role the economy plays in mainstream political discourse and public policy. Radical right parties, on the contrary, overemphasize non-economic issues by devoting over 40% of their manifestos to them on average. Economic issues are instead neglected, with only some 22% of manifesto space. The most striking is the relative difference: radical right parties devote almost twice as much of their manifestos to non-economic, rather than economic, issues.

Figure 1 Issue salience by party type. Comparative manifesto data. Average salience by party type for years 2000 and up.

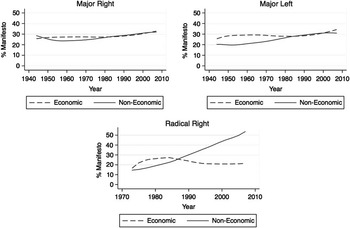

A similar picture emerges when considering the long-term trend of economic and non-economic issue salience of these three party types (Figure 2). Both major left and major right parties balance their attention between economic and non-economic issues over the post-war period. Radical right parties, on the other hand, place more or less constant emphasis on economic issues, while devoting increasingly more of their manifestos to non-economic issues over time.

Figure 2 Issue salience in the post-war period. Comparative manifesto data.

Economic position blurring

Radical right parties project themselves as parties contesting predominantly non-economic issues. For strategic reasons, they muddy their economic outlooks and shy away from discussing economic policies explicitly and at length, which allows them to attract a broader coalition of voters. This economic position blurring is not only picked up by voters, who tend to evaluate the radical right on the basis of their non-economic issue preferences, but also by party experts.

This section tests hypotheses 3a, 3b, and 3c. It first considers the assessment of radical right placements across multiple data sets. Second, it predicts the standard deviations of voter and expert party placements by party types, showing the particularity of the radical right. Finally, it addresses the fluctuations of radical right party placements over time.

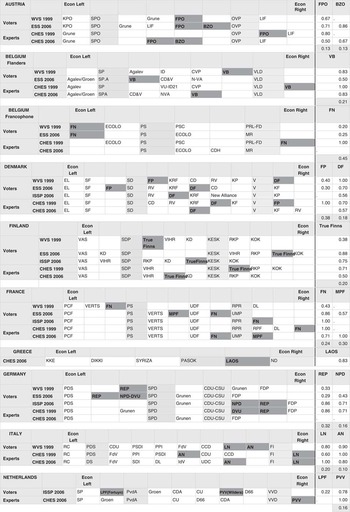

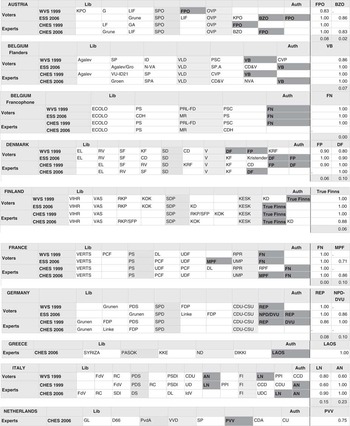

Figures 3 and 4 present ordinal expert placement of political parties and ordinal positioning of mean radical right voters on the economic and non-economic dimensions.Footnote 9 Each row corresponds to a different source of information on party placement within a given party system. Parties are arranged horizontally from left to right on the economic dimension and from social liberalism to authoritarianism on the non-economic dimension. They are lined up with major left and major right parties (lightly shaded) within each party system, while radical right parties are emphasized in bold.

Figure 3 Economic positioning of radical right parties. Extreme right parties are in bold. Anchored by mainstream left- and right-wing parties. Please see Appendix for details regarding the construction of dimensions.

Figure 4 Non-economic positioning of radical right parties. Extreme right parties are in bold. Anchored by mainstream left- and right-wing parties. Please see Appendix for details regarding the construction of dimensions.

The data show that radical right economic placement seems rather erratic. While some sources suggest that a radical right party stands on the extreme economic right, others place it to the left of the major left party in the given system (Figure 3). This contrasts sharply with radical right positioning on the non-economic dimension of competition, where a vast majority of sources agree, and place the radical right on the authoritarian fringe (Figure 4).

The right-hand column of Figures 3 and 4 provides summary measures of radical right ordinal placement, while taking the number of parties in the party system into account.Footnote 10 The standard deviation of these placements is reported at the bottom of the column. The mean standard deviation – that is the average discrepancy between the placement measures of each radical right party – is 0.226 on the economic dimension, while it is just 0.081 on the non-economic dimension.

This evidence, showing that radical right party placement on the non-economic dimension is very consistent across data sources, but that their placement on economic issues diverges extensively within each system, supports hypothesis 3a. This finding underscores the limited utility of spatial conceptions when studying radical right parties. Rather than holding positions on economic issues, radical right parties try to avoid clear economic stances.

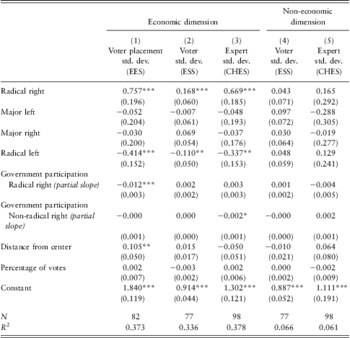

Consequently, it is important to address whether radical right placement varies significantly more than that of other parties. Table 2 presents results of ordinary least squares (OLS) regression analyses predicting voter and expert standard deviations on party placement on the economic and non-economic dimensions.Footnote 11 The standard deviations are explained by party family: major right, major left, radical right, and radical left.Footnote 12 In addition, the models control for general party characteristics: distance from the center of the left–right dimension; government participation; and vote share. Government participation is interacted with the radical right dummy variable in order to assess hypothesis 5.

Table 2 Predicting voter and expert placement std. dev.

EES = European Election Study; ESS = European Social Survey; CHES = Chapel Hill Expert Survey.

Standard errors are given in parentheses, ***P < 0.01, **P < 0.05, *P < 0.1. OLS Regression. The dependent variables are party-level std. dev. – they measure either voter or expert deviations from party-specific means. Voter placement of parties on the general left-right scale measured in the EES (2004; model 1). Voter positions on economic and non-economic dimensions measured in the ESS (2006; models 2 and 4). Expert placement on economic left-right scale and social liberalism and authoritarianism measured in the 2006 CHES (models 3 and 5). Partial slopes calculated using Stata's ‘xi3’ command written by Michael Mitchell and Phil Ender.

The results in Table 2 support hypothesis 3b suggesting that radical right parties blur their economic positions. In the first three models concerning the economic dimension, the coefficient on the radical right is positive and statistically significant, meaning that voters and experts are significantly less certain (have higher standard deviations) about radical right parties. Major parties do not have a significant effect on voter and expert (un)certainty. Interestingly, both voters and experts are more certain about the economic placement of radical left parties, as the radical left has a negative effect on blurring (their standard deviations are significantly smaller). On the non-economic dimension (models 4 and 5), party families do not predict the certainty of voter or expert placement at all. This suggests that there is no significant difference in the (un)certainty of voters and experts about major and radical party placements on the non-economic dimension – they are comparably certain about the placement of all of these parties.

These results reject the speculation that voters and experts simply do not know as much about the parties belonging to the radical right and left, which tend to be smaller and stand on the political extremes. The results further reject the notion that the dependent variable of expert and voter standard deviations thus merely taps the voters’/experts’ (lack of) knowledge, rather than party strategies. First, the models control for vote share and distance from the center. Second, voters and experts are more certain about radical left placement, while exhibiting significant doubts about the radical right on the economic dimension. This discrepancy cannot be simply attributed to voter's and expert's lack of knowledge of smaller, outlying parties. It is very likely that deliberate partisan strategizing – economic blurring of the radical right – is the cause.

The interaction effect in the models of Table 2 provides a basis for evaluating hypothesis 5, which expects radical right parties to decrease their economic blurring when their party is in power. The partial slope associated with the effect of government for radical right parties shows significant effect in the expected direction only in model 1. This supports hypothesis 5 by showing that voters are significantly more certain of radical right party placement on economic issues when these have been in government. However, since the finding is not reproduced in other models, the test of hypothesis 5 is inconclusive. A more refined time-series assessment of radical right strategies when their party forms the government, which is beyond the scope of this article, is likely to provide a clearer answer.

The final test of radical right economic blurring, evaluating hypothesis 3c, assesses radical right party's ideological stability on this dimension over time. Given the hypothesized vagueness of radical right economic placements, we should expect significantly greater positional shifts on the economic dimension among radical right parties as compared to major parties. These shifts should not be interpreted as true movements in the radical right's positions, but rather as a reflection of the uncertainty of their positions.

Table 3 summarizes the mean positional change of radical right and major parties over three time periods, measured by the CHES – 1999, 2002, and 2006. The table provides statistical tests of differences in average absolute position change of individual parties over this time period. Supporting hypothesis 3c, it shows that radical right parties appear to change their positions on economic issues significantly more than major parties. On non-economic issues, radical right parties are not significantly different from major parties.

Table 3 Party position change over time

Mean of absolute change of party positions between 1999, 2002, and 2006. Means difference tests assume unequal variances (Chapel Hill Expert Surveys).

Thus, the evidence so far suggests that radical right parties employ deliberate dimensional strategies. They compete on non-economic issues, while blurring their stances on economic issues. These parties emphasize non-economic issues over economic ones in their manifestos. Both voters and experts are significantly uncertain about radical right economic placement, although they are more certain about the placements of other parties. Finally, radical right parties exhibit seeming instability in their economic placements over time. All these suggest that radical right parties purposefully obscure their economic placements. The next section considers the electoral consequences of this strategy.

Why support the radical right?

Since radical right parties tend to mostly consider non-economic issues, voters should support radical right parties when they agree with them on non-economic issues, as per hypothesis 4. Economic issues should play a limited role in voters’ calculus over casting a vote for the radical right.

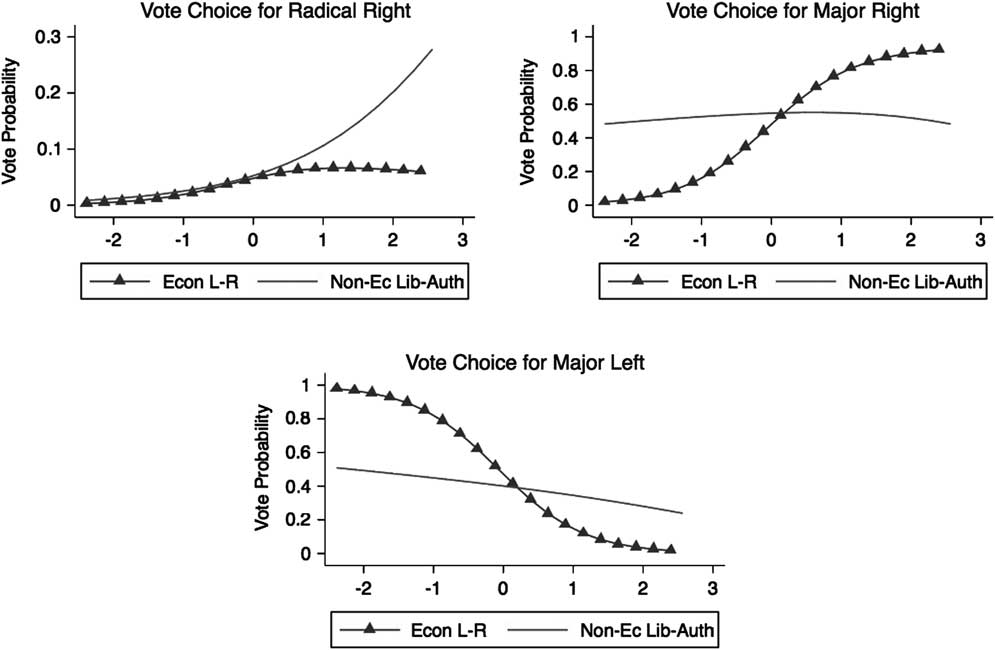

Figure 5 reports results of the Multinomial Logit model predicting vote choice for radical right parties using the 2006 ESS. The model predicts party vote choice by positioning on the economic and non-economic dimensions, while controlling for voters’ gender, age, education, and income.Footnote 13 Although this analysis presents combined data across party systems, looking at individual parties produces substantively comparable results. Substantively comparable results are also obtained using other data sets.Footnote 14 The figure presents the predicted probabilities of voting for radical right and major parties, given a voter's positioning on the economic and non-economic dimensions,Footnote 15 while other predictors are held at their mean.

Figure 5 Vote choice for different party types. Predicted probabilities for economic and non-economic positions while other variables held at their means. Based on Multinomial Logit model presented in Table A1 in the Appendix. European Social Survey (2006), estimated using Stata 11.1 ‘prgen’ command.

The graphs support hypothesis 4 by showing that voters of radical right parties cast their votes on the basis of non-economic issue considerations. Radical right parties attract voters who stand at or near the authoritarian extreme of the non-economic dimension. Conversely, voters do not tend to place similar emphasis on economic concerns while voting for the radical right. Although statistically significant, positioning on the economic dimension does not substantively affect the probability of voting for the radical right. The predicted probabilities stemming from the economic dimension are very low, and the economic left–right curve is almost flat. In comparison, mainstream parties attract voters on both dimensions, while voters’ economic preferences have a particularly strong impact on mainstream party vote.

The radical right's strategies of deliberately understating economic issues and blurring its stances on them shape its electoral fortunes. Since voters do not support the radical right on the basis of economic preferences, radical right parties are able to attract a broader electoral coalition, spanning from unemployed industrial workers to some white collar workers and the self-employed. Multidimensional party competition, with its strategies of issue emphasis and position blurring, permits the amalgamation of voters united by some preferences, but divided by others, with significant electoral consequences.

Conclusion

This article explores the puzzle of radical right party positioning. Using party manifesto data, expert data on party placement, and data on voter preferences, it argues that radical right parties contest the structure of political competition. Due to their investment in various issues, they employ diverse strategies in different dimensions. Consequently, radical right parties emphasize and take clear ideological stances on the authoritarian fringe of the non-economic dimension, while deliberately avoiding precise economic placement.

This article presents a dimensional approach to political competition, which sees politics as competition over the issue composition of political space. Parties compete for voters by seeking to shift the basis of political competition. To sidestep major parties, non-entrenched parties like the radical right are inclined to explore previously neglected issues, such as nationalism and anti-immigration – a strategy facilitated by their hierarchical organizational structure.

This dimensional competition renders the partisan strategy of position blurring viable. Although position blurring has been analyzed as costly in uni-dimensional competition, it is a potentially rewarding strategy in multidimensional contests. While competing on the non-economic dimension, radical right parties maintain a consciously opaque profile on economic issues. Through this position blurring they remove or misrepresent their spatial distance from voters, and attract a broader coalition of economic interests.

Radical right parties benefit directly from their strategy of economic position blurring. Voters respond to partisan signals and vote for radical right parties on the basis of their non-economic issue interests, rather than economic preferences. This benefits the radical right by securing electoral support from socially authoritarian voters, without deterring voters on the basis of economic issue preferences. Blurring ideological positions is thus a rational strategy on the part of the European radical right.

The dimensional approach to political competition presented in this article is consistent with the spatial paradigm in that it considers party and voter placement in n-dimensional space. It is, however, inconsistent with spatial theory, which sees party competition as position taking, without considering the relative stakes that parties may have in different issue dimensions. It is the argument of this article that these stakes determine partisan strategic calculations, potentially leading them to avoid taking positional stances. The academic debate over radical right placement on economic issues should consequently consider the limits of spatial theory, and acknowledge the possibility that parties may compete by deliberate position blurring.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Gary Marks, Liesbet Hooghe, Herbert Kitschelt, George Rabinowitz, John D. Stephens, James A. Stimson, Milada Anna Vachudova, Georg Vanberg and three anonymous reviewers for their helpful suggestions. Special thanks for her comments, editing and support go to Allison E. Rovny. All outstanding errors are mine.