Introduction

The COVID-19 outbreak caused an exceptional social and health crisis that forced politicians to address the fundamental rights of individuals with various recommendations and restrictions that reduce social interaction. The situation of uncertainty and the flood of information tested the cornerstones of representative democratic societies: average citizens had to trust that politicians’ decisions that restrict citizens’ rights are timely and in the best interests of the population as a whole. The aggregate level of trust forms the starting point for crisis management, especially in countries where people enjoy the freedom to act on their own volition, reason, and interest (Esaiasson et al., Reference Esaiasson, Sohlberg, Ghersetti and Johansson2021). Perhaps partly due to this fact, the health crisis evoked a lot of scholarly attention to research on trust.

Thus far, the focus has mostly been on the effect of trust in policy responses and the pandemic’s impact on trust. The significance of trust was revealed in the first wave of the pandemic, as various restrictions and recommendations were introduced more quickly and COVID-related mortality progressed more slowly in countries with high confidence in political institutions (Oksanen et al., Reference Oksanen, Kaakinen, Latikka, Savolainen, Savela and Koivula2020; Elgar et al., Reference Elgar, Stefaniak and Wohl2020). Other studies also showed a linkage between greater trust in political institutions and increased compliance with COVID-19 mitigation strategies (Hafner-Fink and Uhan, Reference Hafner-Fink and Uhan2021; Madsen et al., Reference Madsen, Mikkelsen, Christensen and Bækgaard2020; Olsen and Hjorth, Reference Olsen and Hjorth2020; Sedgwick et al., Reference Sedgwick, Hawdon, Räsänen and Koivula2021). The previous findings also suggested that the COVID-19 outbreak increased trust in political authorities from an initial phase to an acute phase in the spring of 2020, thus reinforcing the democratic status quo (Jennings, Reference Jennings2020; De Vries et al., Reference De Vries, Bakker, Hobolt and Arcenaux2021; Amat et al., Reference Amat, Arenas, Falcó-Gimeno and Muñoz2020; Esaiasson et al., Reference Esaiasson, Sohlberg, Ghersetti and Johansson2021; Groeniger et al., Reference Groeniger, Noordzij, van der Waal and de Koster2021).

The studies on political trust in the initial phase of the pandemic have largely focused on the upsurge of political trust during the first wave—either as a factor enabling strict policy measures or because of them. Besides these questions, we should ask to what extent was trust in the pandemic situation based on critical evaluation of the decision makers’ accountability and to what extent trust derived from anxiety and emotional attachment to the authorities, in a new and unpredictable situation. This distinction may have significant underpinnings for citizens’ willingness to adapt to the restrictions and recommendations. One significant factor affecting compliance with recommendations is evidently the trust level per se (e.g., Hafner-Fink and Uhan, Reference Hafner-Fink and Uhan2021). However, we do not know how this compliance is related to citizens’ subjective political competence. With subjective political competence, we refer to a citizen’s internal efficacy, i.e., how capable he/she considers herself of influencing politics, understanding it, and controlling political decision making (Chaples, Reference Chaples1976; Lane, Reference Lane1959).

By analyzing longitudinal data collected from 2017 to 2020, we study 1) how political trust developed within Finland during the first wave of COVID-19, 2) whether increased trust was based on increased feelings of subjective political competence, and 3) how the levels of political trust and subjective political competence were associated with the willingness to follow authorities’ recommendations. Before going into the empirical study, we conceptualize the mechanisms between political trust and political competence according to the previous literature. We also briefly describe the study context, Finland, and how it endured throughout the pandemic.

Theoretical background

Lockdown and rally around the flag effects on political trust

Political trust is an overarching concept covering the evaluations of the object’s competence to act on the subject’s behalf. COVID-19 caused a shock that is potentially shaping the established perceptions of institutions and other people as well as the expectations associated with them. In general, it is still unclear which characteristics weigh the most when citizens evaluate their trust in political authorities: the decision makers’ competence, care, commitment, reliability, or predictability (see van der Meer and Dekker, Reference van der Meer, Dekker, Zmerli and Hooghe2011; van der Meer, Reference van der Meer and Uslaner2018). It is likely that evaluation of all of these occurs in a health crisis.

Experienced trust may result from a longer socialization and therefore may be strongly linked to social frameworks (Campbell, Reference Campbell1979; Uslaner, Reference Uslaner2002). The competing theory claims that political trust directly reflects the current institutional performance, and the established finding is that economic performance in particular directly affects an individual’s political trust (Hetherington, Reference Hetherington1998; Mishler and Rose, Reference Mishler and Rose1997). Independent of its roots, a high level of political trust, in general, works as a buffer in situations in which difficult political decisions are bound to be made, and it keeps the democratic system together in economic, political, and social crises (van der Meer and Zmerli, Reference van der Meer and Zmerli2017). If a society is built on trust, even in a situation in which decisions must be implemented effectively and quickly, the citizens accept them more easily. Previous studies have shown, however, that political scandals (Bowler and Karp, Reference Bowler and Karp2004) and other societal crises (Nicholls and Picou, Reference Nicholls and Picou2013) influence the level of political trust, and this impact is likely to be negative. Therefore, crisis situations test even high-trust societies. Evidently, during the first wave of COVID-19, the statistics on cases, deaths, and those who recovered were probably more important in citizens’ evaluation of institutional performance than economic situation. However, it is highly likely that trust levels also in high-trust societies will suffer from the economic situation following the pandemic. The trust levels, however, tend to recover as soon as the economy recovers (van der Meer, Reference van der Meer and Uslaner2018).

The usual factors that cause democracies’ trust levels to fluctuate—economic recessions and political scandals—are endogenous in character. In contrast, during the pandemic, the political system has been threatened from the outside, due to which citizens have been more willing to accept strong leaders, support strong technocratic governance, and give up their own freedom (Amat et al., Reference Amat, Arenas, Falcó-Gimeno and Muñoz2020). As De Vries et al. (Reference De Vries, Bakker, Hobolt and Arcenaux2021) noted, during the first wave of COVID-19, developments abroad significantly affected incumbent approval at home. This is hardly exceptional for the COVID-19 crisis: the preference for strong leadership and willingness to accept control and restrictive operations to reduce personal insecurity and psychological strain have been rather common in other crises as well (see e.g., Hasel, Reference Hasel2013; Hunt, Reference Hunt1999). During COVID-19 the so called lockdown effect highlights citizens’ approval for political institutions with increased trust (e.g., Amat et al., Reference Amat, Arenas, Falcó-Gimeno and Muñoz2020; Madsen et al., Reference Madsen, Mikkelsen, Christensen and Bækgaard2020; De Vries et al., Reference De Vries, Bakker, Hobolt and Arcenaux2021). Indeed, for instance, Bol et al. (Reference Bol, Giani, Blais and Loewen2021) and Groeniger et al. (Reference Groeniger, Noordzij, van der Waal and de Koster2021) showed that the lockdowns in the first acute phase increased support for the incumbents, thus giving support for the retrospective evaluation of performance mechanisms. While aiming to protect health, the lockdowns simultaneously reduced civil liberties, increased economic insecurity, and eroded social capital (Elgar et al., Reference Elgar, Stefaniak and Wohl2020). However, confidence in one’s own ability to absorb information from several sources, and to process that information, creates the basis for the critical evaluation of the government measures. Willingness to follow the restrictions requires the ability to evaluate how threatening one believes the pandemic is to themselves but also to the entire society (see Olsen and Hjorth, Reference Olsen and Hjorth2020).

Having said that, citizens’ perspective of the ‘knowledge’ about the virus itself, the disease it causes, and prevention of and recovery from the disease are multidimensional and contradictory (Gallotti et al., Reference Gallotti, Valle, Castaldo, Sacco and De Domenico2020; Naeem and Bhatti, Reference Naeem and Bhatti2020). Evidently, we cannot know how realistically the citizens evaluate their own competence to understand political decision making in a complex situation in which health professionals mainly lead discussion, though admittedly, subjective political competence is theoretically and empirically related to key measurements of more objective political competence (i.e., political knowledge and political interest; Craig and Maggiotto, Reference Craig and Maggiotto1982), which are also key factors in building political trust.

Indeed, as Schraff (Reference Schraff2020) argues, collective angst in the face of exponentially rising COVID-19 may as well put the usual cognitive evaluations of institutions aside and lead citizens to rally around the existing institutions. Like in lockdown effect, in the rally around the flag effect, the government has a significant role in shaping public attitudes. While, however, the former is based on the citizens’ evaluative judgments of the effectiveness of government measures, the latter is more emotionally driven. Rallying around the flag is based on elite messages that create national identity, strengthen national affiliation, and relieve feelings of insecurity and anxiety. It should be noted here, however, that even if the lockdown effect is based on citizens’ evaluation of the government measure, it does not say anything about how much objective knowledge they have on the COVID-19 pandemic, as such, but to what extent citizens feel that they are part of the political process in a crisis situation. In contrast, the rally around the flag effect makes citizens pure spectators of the governmental decisions.

Subjective political competence and political trust

It is unclear what kind of long-term impact the rather short-term shocks, like the pandemic, have on political systems in general, and political trust in particular. Indeed, incumbents’ everyday choices may affect trustworthiness of the whole political system because political trust is ‘a middle-range indicator of support’ for political institutions where attitudes toward democratic principles and everyday actors and policies meet (Zmerli et al., Reference Zmerli, Newton, Montero, van Deth, Montero and Westholm2007). In other words, if the crisis erodes the specific support for a political system (Easton, Reference Easton1965, Reference Easton1975)—that is, support for those in power—the discontent may spill over to political institutions in general (see Bowler and Karp, Reference Bowler and Karp2004).

Political trust is first and foremost about the relationship between the citizens and the state. Presumably, this relationship is severely weakened if citizens find that they do not have sufficient knowledge to act in the political system or are unable to affect its decision making (e.g., Finifter, Reference Finifter1970). Thus, when evaluating the state of democracy, the level of political trust, and the citizens’ ability to understand the political situation, political decision making and policy measures should be considered. The degree of political trust can be divided roughly into three concepts: distrust, trust, and lack of trust. The first two are linked to citizens’ deeper orientation toward political institutions, and the third is likely to be associated with short-term evaluations of politicians and political events (Cook and Gronke, Reference Cook and Gronke2005). These concepts, however, do not say much about citizens’ political competence that the trust or distrust is based on. This is particularly important to note in a crisis situation that is, as the COVID-19 pandemic has shown, accompanied by a massive information flow from various sources (Gallotti et al., Reference Gallotti, Valle, Castaldo, Sacco and De Domenico2020). The development of informed opinion requires interest in the issue and the analytical skills to differentiate reliable from less reliable sources.

Therefore, at the citizen level, supportive citizens should be separated conceptually from committed ones (original concepts, see Sniderman, Reference Sniderman1981). Political trust of the former is based on a citizen’s confidence in her ability to evaluate political decision making critically and make a balanced judgment of its benefits and shortcomings (Hooghe and Marien, Reference Hooghe and Marien2013). The latter refers to a citizen with weak political competence who supports the system but trusts the political decisions in the hands of the elite without critically evaluating them. Building on this idea, we recognize two additional groups of citizens. Those with strong subjective political competence may withdraw their trust if they feel the system is not acting according to their normative expectations. We describe such citizens as critical. Citizens may also lack subjective political competence and not trust the system itself. This group of citizens, we call politically alienated. Figure 1 presents these four groups of citizens in quadrants.

Our categorization somewhat resonates with the ideas of Norris (Reference Norris2022), who distinguishes skeptical trust from skeptical mistrust. In the former, the performance of political institutions and the citizen support correlate positively, and in the latter, the performance and the trust level turn negative. Thus, the relationship of the supportive citizens to the political system could be characterized as skeptical trust while critical citizens present skeptical mistrust. Norris (Reference Norris2022) continues, however, that skeptical citizens should be able to offer coherent reasons for the untrustworthiness of the political decision-makers and political institutions but this is not necessarily the case. The trust (or distrust) may have its roots in more affective projections and cultural values, e.g., by negative partisanship, ideological views about the role of government, or by identity cues derived from shared personal characteristics and social traits. Thus, it should be noted that while critical citizens evaluate the political system based on either their subjective political competence and/or on their factual knowledge, this does not mean that this evaluation is always objective and based on rational reasoning.

Figure 1. Interaction between political trust and political competence.

Research context

In general, Finland, like its Nordic neighbours, boasts high trust levels from one comparative study to another and therefore had a strong baseline of trust regarding pandemic management (e.g., Oksanen et al., Reference Oksanen, Kaakinen, Latikka, Savolainen, Savela and Koivula2020). Preliminary results from Finland also showed that public trust in decision makers was high during the first year of COVID-19 (Jallinoja and Väliverronen, Reference Jallinoja and Väliverronen2021). Surprisingly, however, when compared to other Nordic countries, the average subjective political competence or internal efficacy (i.e., the belief that one can understand politics) is exceptionally low in Finland (Kestilä-Kekkonen, Reference Kestilä-Kekkonen, Borg, Kestilä-Kekkonen and Westinen2015; Rapeli and Koskimaa, Reference Rapeli, Koskimaa, Kestilä-Kekkonen, Borg and Wass2020). No conclusion has been reached regarding why this continues to be the case from one election study to another: the usual suspects are the Finns’ self-critical mentality, the open list electoral system with candidate choice and party proportionality, and coalition governments based on consensual decision making. Although high trust and low subjective political competence are long-term phenomena in Finland, we lack knowledge about how these factors combine and how they evolve in specific cases, like during the pandemic in Finland.

Finland survived the first wave of COVID-19 relatively well. Infections admissions to intensive care units and mortality were low compared to other European countries (Oksanen et al., Reference Oksanen, Kaakinen, Latikka, Savolainen, Savela and Koivula2020). The first infections were detected in early January, but significant spread did not begin until mid-March. Weekly case numbers peaked as early as April, after which they began to decline (WHO, 2020).

The Standby Act was introduced on 16 March 2020, when there were just over 400 confirmed cases. The Standby Act included stringent restrictions that regulated people’s lives in many ways: Those 70 years and older were strongly encouraged to stay in quarantine-like conditions; movement into and out of the metropolitan area was restricted because the coronavirus situation there was clearly worse than elsewhere. Most educational facilities were restricted except for children in grades 1–3 and whose parents worked in critical sectors. Visits to care institutions, health care units, and hospitals were largely banned, except for special groups. Working remotely when possible was recommended. In addition, public venues and restaurants were closed. Finns in other countries were called home, and those returning from abroad were instructed to quarantine or maintain quarantine-like conditions for two weeks. Finland’s borders were closed except for work and freight traffic. Finns were also encouraged to refrain from unnecessary domestic travel (Koivula et al., Reference Koivula, Vainio, Sivonen and Uotinen2020).

Strong restrictions did not undermine support for the ruling political parties during the first wave of the coronavirus. On the contrary, support for the Social Democratic Party (SDP), the largest party in Finland, clearly increased. According to regular polls, the SDP was supported by 16% of the population in February 2020 and 22% at the peak of the first wave of COVID-19. In April 2020, Prime Minister Sanna Marin was widely praised for her clear communication and effective leadership in times of crisis. According to a recent study, Marin was involved with leaders who were able to coordinate the various branches of the government, the public, and the scientific community to rally for the greater public good in the battle against COVID-19 (Purkayastha et al., Reference Purkayastha, Salvatore and Mukherjee2020).

This study

Hypotheses

At the first stage of study, we assessed how the level of political trust developed after the outbreak of COVID-19 and how the changes were related to changes in political competence by utilizing longitudinal panel data.

Based on previous research, we hypothesized (H1) that Finns’ trust in political institutions increased in the early stages of the COVID-19 outbreak. Citizens typically rally around the flag in the early stages of external crisis and support their governments (Mueller, Reference Mueller1970). Many studies have shown this to be the case in other countries during the COVID-19 pandemic (Sibley et al., Reference Sibley, Greaves, Satherley, Wilson, Overall, Lee, Milojev, Bulbulia, Osborne, Milfont, Houkamau, Duck, Vickers-Jones and Barlow2020; Bol et al., Reference Bol, Giani, Blais and Loewen2021; Schraff, Reference Schraff2020; Elgar et al., Reference Elgar, Stefaniak and Wohl2020; Esaiasson et al., Reference Esaiasson, Sohlberg, Ghersetti and Johansson2021).

Our second hypothesis (H2) was that political competence was negatively associated with political trust in the early stages of the COVID-19 outbreak. The COVID-19 outbreak has shown how much information is available in the current media environment and how difficult it is for citizens to understand all the information that influences decision making (Gallotti et al., Reference Gallotti, Valle, Castaldo, Sacco and De Domenico2020; Weber and Koehler, Reference Weber and Koehler2017). In this uncertain situation, information is exceptionally fragmented and widely available, so people’s perception of their own abilities and effectiveness may not increase even if interest and activity in information retrieval increases. Therefore, it is very likely that trust will also increase independent from changes in subjective competence. Other side of the coin is that those who feel capable of absorbing information from different sources in a complex manner, may be more ready to question the government’s actions and feel more ready to be able to evaluate their long-term consequences, which has underpinnings for their level of political trust.

At the second stage of the study, by utilizing cross-sectional data, we analyzed how political trust and political competence were associated with people’s compliance with various recommendations at the first wave of COVID-19. By following recent literature (Bargain and Aminjonov, Reference Bargain and Aminjonov2020; Balog-Way and McComas, Reference Balog-Way and McComas2020), we put forward the hypothesis that (H3.1) political trust is positively associated with recommendation compliance. Moreover, we assumed that those with strong political competence may also act as voices that are critical of the authorities’ decisions (Norris, Reference Norris1999; Geissel, Reference Geissel2008), which is likely to be reflected in a backlash against recommendations. Therefore, we hypothesized that (H3.2) subjective political competence was negatively associated with recommendation compliance.

After direct associations, we examine the interaction between trust and competence. We assume that when high levels of trust and strong subjective political competence interact, they create the basis for informed citizenship, which forms a solid ground for trust in authorities’ decisions and active participation among individuals (Hooghe and Marien, Reference Hooghe and Marien2013). In this respect, we expect (H4) a significant interactive effect of political trust and subjective political competence on recommendation compliance.

Participants

We utilized three-time-point longitudinal data derived from the first three rounds of the Digital Age in Finland survey. With ‘t1’, we refer to the survey that was implemented at the turn of the years 2017 and 2018, t2 refers to the survey data collected in 2019, and t3 refers to the survey data collected in 2020. We collected the final round of data between 12 May and 12 June 2020, when multiple restrictions related to the first wave of COVID-19 were still in place (Koivula et al., Reference Koivula, Vainio, Sivonen and Uotinen2020).

This study’s longitudinal data were based on responses from citizens who participated in each round of surveys. The first survey at t1 included 3,724 respondents, of which 66% were taken at random from the Finnish Population Register (DVV 2022), and the rest had completed the online panel organized by Taloustutkimus Inc. We asked respondents whether they would be willing to participate in a second survey about a year after the first data collection. A total of 1,708 participants expressed their willingness to participate in the follow-up survey, which we conducted 15 months after the first round in March 2019. A total of 1,134 people participated in the follow-up survey, comprising a response rate of 67% in the second round. We conducted round 3 among 971 respondents who had expressed their willingness to continue tracking during t2. A total of 735 participants responded to the survey at t3, representing a response rate of 75.7%.

The main question form was essentially the same for each round of data collection. The final round also included questions specific to COVID-19, which we presented at the end of the main question form. Birth cohorts from 1943 to 1999 participated in each round. The data were slightly biased in terms of gender and age distribution (Male 52.3%, Mage = 51.6, SDage = 15.9). A more detailed description of the data collection and its representativeness is shown in the data report published online (Koivula et al., Reference Koivula, Vainio, Sivonen and Uotinen2020).

Measures

Table 1 shows the variables used in this study and their descriptive statistics. At the first stage of the analysis, we focused on longitudinal changes in political trust. We concentrated on trust in politicians, political parties, and the Finnish parliament. The internal consistency of the items was 0.85 (Cronbach’s alpha). From these items, we computed a mean variable (M = 2.61, SD = 8.4) with slight kurtosis (2.56) and very small skewness (−.06). Political trust was a time-variant variable at the first stage of the study. At the second stage, we considered the level of trust measured in the third round.

We asked all three questions about political trust similarly across rounds and measured respondents’ trust in various institutions via a 5-point scale, from 1 (not trustworthy at all) to 5 (very trustworthy). In recent years, there has been an increasing shift to measure political trust with a more granular 11-point scale used, for example, in the ESS survey. On the other hand, a significant portion of previous research has been conducted on a narrower 3-4 point scale (Citrin and Stoker, Reference Citrin and Stoker2018). Political trust has also been measured on a 5-point scale in many previous studies, including the ISSP survey and COVID-related studies (e.g. Strömbäck et al., Reference Strömbäck, Djerf-Pierre and Shehata2016; Goubin, Reference Goubin2020; Lalot et al., Reference Lalot, Heering, Rullo, Travaglino and Abrams2020).

Subjective political competence was a key explanatory variable throughout the analysis. In general, political competence or internal efficacy has been measured in terms of whether the respondent perceives the politics as too complex for someone like him/her or the extent to which he or she feels able to influence various political issues (Craig and Maggiotto, Reference Craig and Maggiotto1982). However, our question was aimed specifically at the level that the respondent found she/he understood in general about politics and social issues. The question was elicited in each round with a single question: ‘How would you rate your understanding of political issues on a scale from 0 to 10?’ The extreme values were labeled with a score of 0 (very poor) and 10 (very good). At the first stage of the study, we take into account the variation in competence between time points. At the second stage, we consider the respondent’s competence measured in the third wave.

At the second stage of the study, we analyzed to what extent political trust and competence were associated with compliance with authorities’ health recommendations. For a dependent variable, we focused on social distancing as a popular health-protection measure for compliance during the COVID-19 outbreak (e.g., Sedgwick et al., Reference Sedgwick, Hawdon, Räsänen and Koivula2021). We approached this variable solely in the final round of the survey (t3), in which we asked to what extent the following statements describe respondents: ‘I have limited my time spent in public places’, ‘I have limited my time spent with friends’, ‘I have limited my time spent with relatives’, and ‘I have limited my time spent with people in at-risk groups’. The possible responses were 1 (not at all), 2 (very little), 3 (somewhat), 4 (significantly), and 5 (very significantly). The internal consistency of variables was very high (Cronbach’s alpha 0.9). We then combined the responses into a mean variable. Due to high kurtosis (5.4) and skewness (−1.6), we rounded values to integers to mirror the initial response scales and treated the variable as ordinal in further analysis.

Throughout the analysis, we controlled for respondents’ interest in politics. Political interest has been measured in previous studies in many ways but most often on a four-point scale. Our question aims at the level of general interest in politics on an 11-point scale and has been used in the past, for example, in the Swiss Household Panel (Prior, Reference Prior2010). We asked about political interest in each round with the same question: ‘How would you rate your interest in politics on a scale from 0 to 10?’ The presented scale was labeled from 0 (not at all interested) to 10 (very interested). We treated political interest as a time-variant variable at the first stage of the study. At the second stage, we considered the respondents’ interest measured in the third wave.

Other control variables included party preference, birth cohort, education, gender, and region. We asked about respondents’ party preference in the second round, one month before the parliamentary elections in 2019: ‘Which of the following parties would you vote for if the parliamentary elections were held now?’ All the parliamentary parties were possible responses. In addition, respondents could choose something else or state they would not vote. In the analysis, we compared respondents according to whether the party they preferred was a part of the government or part of the opposition. We also distinguished a separate category for respondents who expressed no party preference or supported a minor party. In Finland, the 2019 parliamentary elections have been the basis for the parties’ power relations in government throughout the COVID period.

For the other sociodemographic variables, we also used data collected in the second round. We determined the respondents’ age via an open-ended question in which they reported their year of birth. We treated gender as binary. We categorized respondents’ education into three categories, following the International Standard Classification of Education (UNESCO 2012): ‘Primary’, ‘Secondary’, and ‘Tertiary’. We took the respondent’s region into account by classifying province of residence in relation to the NUTS-2 level, which distinguishes 1) Helsinki-Uusimaa, 2) the rest of Southern Finland, 3) Western Finland, and 4) Eastern and Northern Finland.

Analysis procedure

We conducted the analysis in two stages to test our study hypotheses. The first stage focused on longitudinal associations. We began by concentrating on temporal changes in political trust, political competence, and political interest according to the survey round. We used fixed-effects models with maximum likelihood estimations and cluster-robust standard errors to account for the panel data’s autocorrelated error structure. We standardized the dependent variables so that the effects presented estimated the change from the mean over the observation period.

Afterward, we focused on the longitudinal relationship between political trust and political competence. We constructed the hybrid mixed-effects model by considering the various levels of time-varying variables (within-between) and the effect of time-invariant variables (Schunk and Perales, Reference Schunck and Perales2017). More specifically, we distinguished the between-person effects and within-person effects over time to predict changes in political trust according to changes in political competence while the control variables and time effects were introduced. Consequently, aggregated individual means form Level 2 variables when within-individual observations are considered Level 1 variables. Previous studies have shown that the within-between approach provides researchers with additional information regarding between-group marginal effects (Dieleman and Templin, Reference Dieleman and Templin2014). We first modeled the effect of time-varying variables (competence and interest), while the time effect was introduced by simultaneously modeling the dummies t2 and t3 with respect to the omitted variable t1. Second, we introduced the time-invariant control variables into the model. Finally, we estimated the time interaction considering the effect of time-varying variables at t3.

The second stage of the analysis focused on cross-sectional associations. We assessed how respondents complied with social distancing recommendations during the COVID-19 outbreak. We constructed ordinal logit models to determine how political trust and political competence were associated with the likelihood of complying with recommendations.

Finally, we ran an interaction analysis to determine whether the effect of political trust was related to political competence when assessing recommendation compliance. To understand the disparities between the levels of trust and competence, we also estimated predicted probabilities for the outcome of highest category of social distancing from the final interaction model and plotted the results by standardized political competence across the level of political trust. The level of political trust was assessed using standard deviations from one to two. We performed the analyses with Stata 16 and used a user-written coefplot package to illustrate the results (Jann, Reference Jann2014).

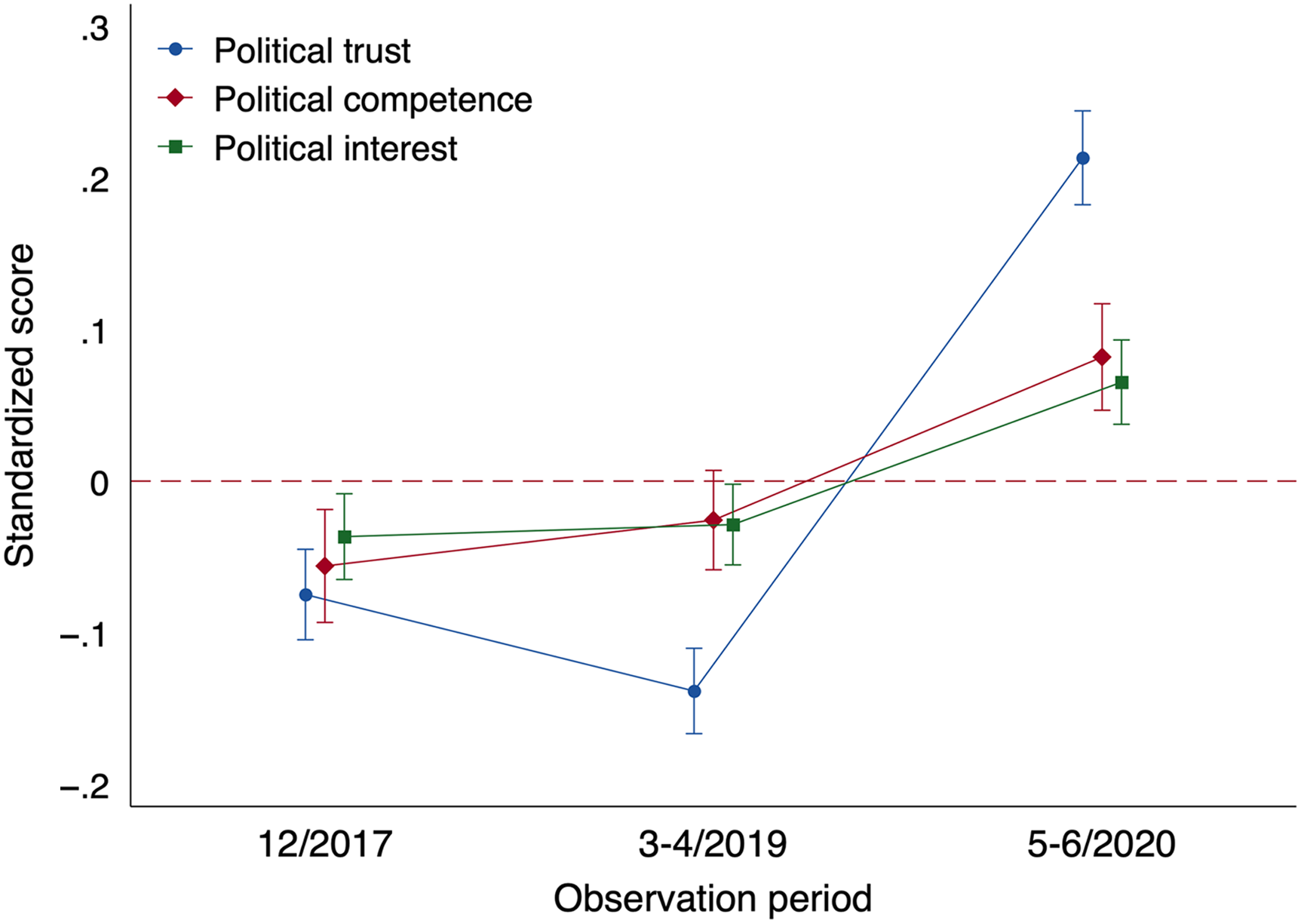

Figure 2. Political trust, political competence, and political interest 2017-2020. The standardized predicted scores from the fixed effect models with the confidence intervals (95%).

Results

Development of political trust at the early stages of COVID-19

Figure 2 shows the longitudinal changes in political trust, competence, and interest. The results supported our hypothesis, revealing that political trust (B = .35, p < .001) increased between t2 and t3. The initial trend of political trust reversed at t3 after decreasing between t1 and t2. Political competence and political interest showed no changes between t1 and t2, but similar to political trust, both increased between t2 and t3.

Next, we analyzed longitudinal changes in political trust according to political competence within and between individuals during the observation period. The within-individual model shown in Table 2 indicates that the growth in political trust was not significantly associated with the growth in political competence within individuals (B = .02, p = .36). The between-individuals model indicated political competence predicted decreased political trust (B = −.13, p = .02). According to the interaction analysis, the effects of political competence did not change in the last observation period, which we conducted during the COVID-19 outbreak.

Table 1. Descriptive statistics of applied variables

Measurement time in parentheses

Table 2. Predicting political trust according to political competence and political interest. Coefficients from the hybrid mixed models

Clustered standard errors in parentheses

*** p < 0.001, ** p < 0.01, * p < 0.05

According to the effect of control variables, political interest predicted increased political trust within and between individuals during the observation period. We introduced the time-invariant control variables into the second model. The results indicated that differences in political trust were associated with tertiary education. Moreover, party preference distinguished individuals because political trust was negatively associated with support for the opposition and for not supporting any parliamentary party. Gender, age, and region were not associated with differences in political trust. Finally, we concluded that the between-effects of political competence and political interest remained significant after controlling for background variables.

The effect of political trust and political competence on health recommendation compliance

The second stage of our analysis focused on the impacts of trust and competence on compliance with the government’s recommendations during the COVID-19 outbreak. Table 3 shows that political trust (B = .35, p < .001) was associated with the increased propensity to comply with social distancing. However, compliance with social distancing was not linked to political competence (B = .06, p = .61).

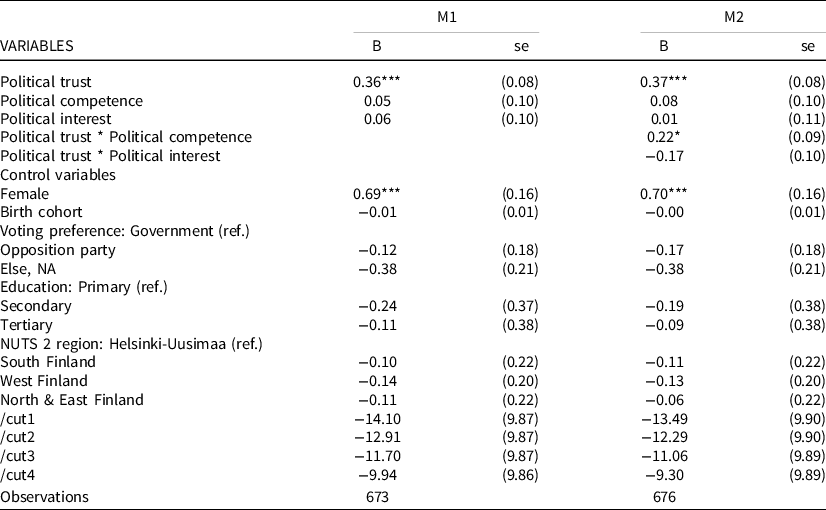

Table 3. Predicting compliance with social distancing recommendations according to political trust and political competence. Coefficients with standard errors from the ordinal regression models

Standard errors in parentheses

*** p < 0.001, ** p < 0.01, * p < 0.05

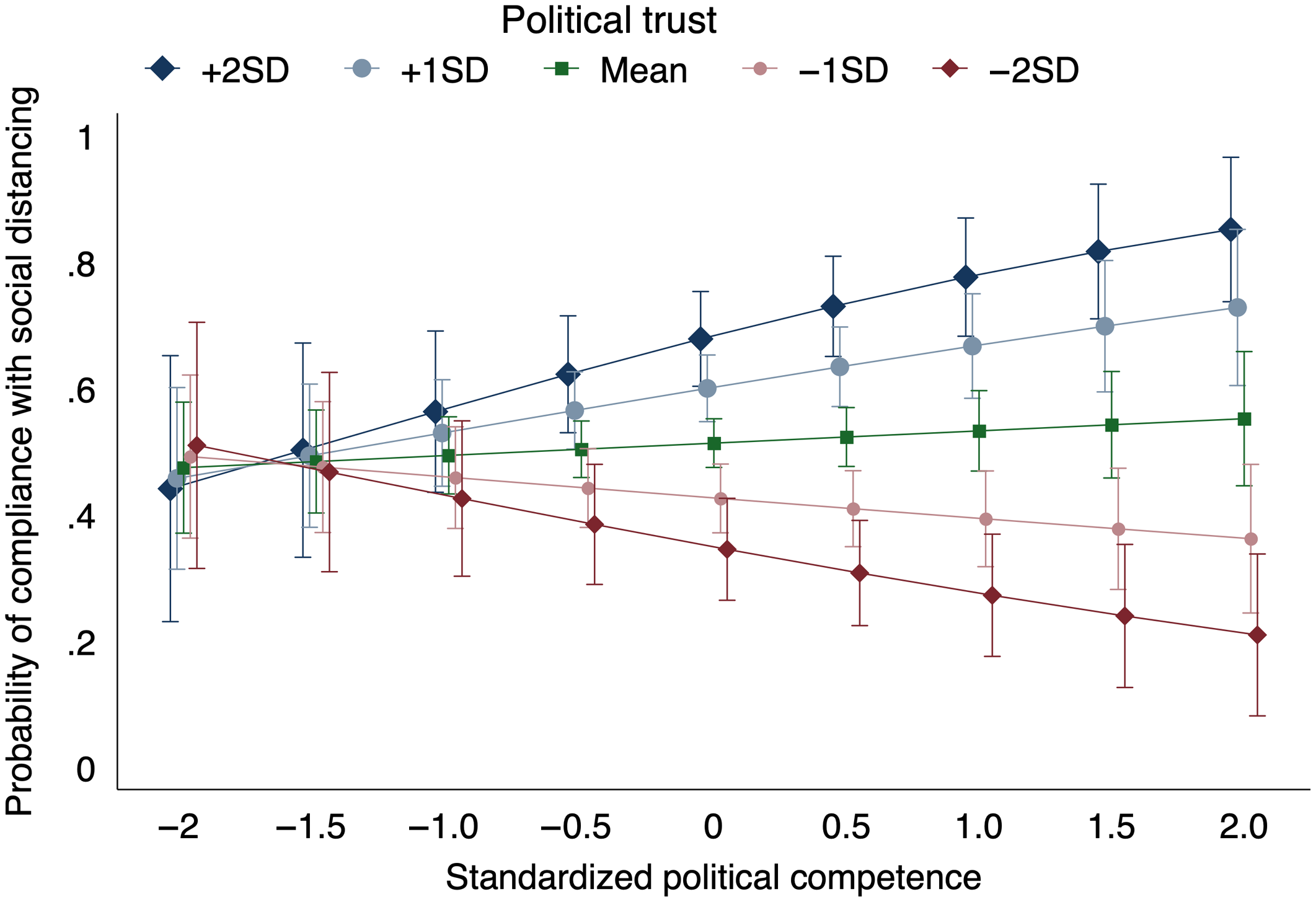

Finally, we found an interaction (B = .22, p = .02) between political trust and political competence. However, the results reveal that the main effect of trust remained significant even after considering the interaction with competence. We illustrate the interaction in Figure 3, showing how the effect of competence varied across levels of political trust. The figure can be interpreted as follows: the likelihood of compliance increased according to competence if trust is high, but the opposite effect was also true: if trust was low, the effect of competence was negative. The effect of trust was significant when competence level was at mean, but it strengthened according to competence. Finally, it can also be interpreted from the figure that high trust did not increase compliance with recommendations if competence was low.

Figure 3. Interaction between trust and political competence when assessing compliance with social distancing. The predicted probabilities from the ordered logistic regression models with confidence intervals (95%).

Discussion

In this study, we examined how political trust and subjective political competence developed in Finland during the first wave of COVID-19 and how they were reflected in people’s behaviour and compliance with COVID-19 protective recommendations. The study underlined previous results and increased the understanding of people’s behavior during a crisis.

Our results provide support to the first hypothesis, suggesting that Finns’ political trust increased significantly during the first wave of COVID-19. As far as we know, this was the first longitudinal study to confirm results observed in previous studies in Finland (Jallinoja and Väliverronen, Reference Jallinoja and Väliverronen2021). Many international studies have also shown that political confidence increased in the early stages of the COVID-19 outbreak despite multiple restrictions and general uncertainty (Sibley et al., Reference Sibley, Greaves, Satherley, Wilson, Overall, Lee, Milojev, Bulbulia, Osborne, Milfont, Houkamau, Duck, Vickers-Jones and Barlow2020; Baekgaard et al., Reference Baekgaard, Christensen, Madsen and Mikkelsen2020).

The second hypothesis was partly supported: according to the between-individual model, subjective competence was negatively associated with trust. However, the within-individual model indicated that changes in competence were not causally related to changes in trust over time among respondents. The between-level effect suggests that those individuals with strong experience of their political competence may be more critical of the actions of decision-makers than those who do not have such strong competence in the early stages of the crisis. The nonsignificant within-individual effect indicates that trust in decision-makers is strengthening in the early stages of the crisis, despite the understanding that political issues would not change. In this respect, we can argue that some people tend to rely on authorities and come together to respond to an external threat during an uncertain situation (Mueller, Reference Mueller1970; Baekgaard et al., Reference Baekgaard, Christensen, Madsen and Mikkelsen2020). Thus it seems that the increased trust in Finland during the first wave of the pandemic was mainly based on rallying around the flag in the insecure situation, which is in line with the previous studies.

The second stage of our study supported the hypothesis (3.1) that people’s compliance with the recommendations was linked to their trust in political institutions. This result is in line with recent findings from various countries highlighting the importance of political and institutional trust in pandemic management (Bargain and Aminjonov, Reference Bargain and Aminjonov2020; Devine et al., Reference Devine, Gaskell, Jennings and Stoker2021; Sedgwick et al., Reference Sedgwick, Hawdon, Räsänen and Koivula2021). Our study also supported the hypothesis (3.2) suggesting that compliance with recommendations was negatively associated with subjective political competence. Perceived understanding of political and social issues can also be reflected in criticism toward decision-makers. During the COVID-19 outbreak, many recommendations have directly restricted individuals’ rights to decide their own actions, which is also likely to raise critical voices.

Finally, we assumed that trust would moderate how political competence is related to compliance with recommendations. Our results supported the hypothesis regarding the interaction effect (H4) and showed that the effect of trust is strengthened by political competence. The in-depth analysis suggested that compounded high subjective political competence and high trust were associated with higher compliance with recommendations. Adjusted predictions of interaction also suggested that low trust compounded with high competence would lead to less compliance with recommendations. This finding is in line with those of previous studies suggesting that high political competence may also be associated with protesting political behavior (Valdez et al., Reference Valdez, Kluge and Ziefle2018).

If we return to our quadrant model that distinguishes committed citizens from supportive citizens and critical citizens from alienated ones: How political trust and subjective political competence were combined during the COVID-19 crisis? Two of these groups were clearly identified: critical citizens with high competence and low trust and supportive citizens with high trust and high competence. The latter ones comply with recommendations being supportive of the political system and feel they recognize the objectives behind the various decisions political institutions make. Instead, critical citizens had their own perceptions of politically controversial issues, which they channeled into mistrust toward the political system and rejection of the norms its institutions set during the crisis.

We could not find committed citizens who comply with recommendations with low competence and high trust. However, it is noteworthy that trust was a significant factor that seemed to differentiate people’s tendency to comply with recommendations, even though subjective competence was at an average level. According to the results, there was no remarkable alienated group that did not trust politicians, did not feel that they understood political issues, and therefore did not follow the recommendations either. Thus, it seems that the interaction between competence and trust becomes more pronounced as competence is high, but it does not appear in the other direction, since the importance of trust decreases as competence is at low. In this respect, politicians cannot expect even confident citizens to be supportive of decisions unless the information is clear.

Our research underlines previous studies suggesting that political trust creates resilience for people in an uncertain situation, such as a pandemic crisis. Trust facilitates the work of decision makers, ensuring that people voluntarily participate in joint action against the epidemic without separate regulations (Vinck et al., Reference Vinck, Pham, Bindu, Bedford and Nilles2019; Bargain and Aminjonov, Reference Bargain and Aminjonov2020). However, healthy democracy also includes distrust and suspicion, which manifest during a pandemic: Our results show that the highest levels of public compliance with recommendations will be achieved when there is a high level of trust and high subjective political competence. It is therefore of paramount importance that decision makers strengthen people’s feeling that they are able to understand the political processes and have an influence on them.

In a representative democracy, it is essential that citizens partially delegate their decision making rights to politicians and various other institutions, but this delegating can also lead to a ‘paradox of trust’: High levels of trust in political institutions can lead people to underestimate the risks associated with the situation and thus reduce their tendency to act individually (Wong and Jensen, Reference Wong and Jensen2020). One may also ask whether trust is more prone to fluctuations unless it is based on citizens’ own acquisition of information (i.e., political competence). In the long run, this could make planning crisis management challenging: If trust and compliance with measures are strongly interlinked, fluctuations caused by an external factor could affect trust and hence people’s compliance with recommendations. Our research also underlined previous findings suggesting that these dimensions of commitment do not increase over time together, indicating that trust and competence stem from various factors.

An important factor to note is that Finland had successfully managed the epidemic from the very beginning of the crisis, which inevitably strengthened trust in political institutions. For instance, in Finland’s neighboring state, Sweden, health authorities, professionals, and political decision makers had led the response to the COVID-19 crisis. This is in comparison to our test case of Finland, in which the government was primarily responsible for enforcing Finland’s COVID-19 strategy. In Sweden, trust in political institutions (parliament and government) increased, but studies have reported that the increase was not as high as elsewhere in Western Europe and was strongly connected to party politics. Trust in government and parliament increased the most among the government parties’ supporters (Anderson and Oscarsson, Reference Anderson and Oscarsson2020).

Although our research provides valuable insights into people’s experiences, we conducted it in the early stages of the crisis, which significantly impacts interpretations. As the COVID-19 outbreak persists due to viral transformations, individuals’ experiences of the management of the crisis may worsen. This fact will likely contribute to an erosion of public confidence in the government and politicians, as observations of previous epidemics have indicated (Johnson and Slovic, Reference Johnson and Slovic2015). Individuals’ trust in institutions is also embedded in institutions’ performance, and one factor that affects people’s satisfaction and institutional trust is the economic situation (Tabellini, Reference Tabellini2008; Mishler and Rose, Reference Mishler and Rose1997). During the first wave, economic impacts were difficult to predict and did not, therefore, directly affect citizens’ everyday lives. Additionally, economic issues did not receive much media coverage at the time. Instead, the concrete COVID-19 restrictions had more significant effects on citizens’ everyday lives, and the Finnish media was filled with information on COVID-19 restrictions and recommendations. Moreover, following the concrete restrictions might have increased citizens’ confidence that their actions could prevent the spread of the virus. In this respect, we require additional research on the mechanism and a more extended timeframe.

Our research also raises the question of whether the trust that is based on rallying around the flag will deescalate quickly. First, one year after the COVID-19 outbreak, in spring 2021, a more deadly second wave swept across Europe, including Finland. At the same time, the pandemic’s economic impact became more concrete. At the end of 2021, the Omicron variant spread quickly in European countries. This variant was, however, much less deadly, partly due to improved vaccination coverage and started to evoke more critical voices regarding whether the restrictions were still necessary. Therefore, this study’s results might indicate different trends in the levels of political trust and political competence had we collected data during the second wave. The recommendations have been almost removed in Finland at the time of writing although the virus keeps spreading at a fast pace.

In summary, our findings indicate that increased trust is not based on increased subjective political competence. In this respect, some people did not necessarily feel confident in their ability to absorb and process information related to the COVID-19 pandemic but instead handed the responsibility for information processing over to politicians. The results also highlight trust as a critical element that facilitates collective action against the epidemic without constant negotiations about rationales. Accordingly, successful pandemic management requires that the recommendations and restrictions politicians set are successful in mitigating the pandemic’s effects.

Funding

This study was funded by Helsingin Sanomat Foundation and Academy of Finland.

Conflict of Interest

Author A declares that he has no conflict of interest.

Author B declares that he has no conflict of interest.

Author C declares that she has no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.