Introduction

Far right party success depends largely on mobilizing grievances over immigration (Ivarsflaten, Reference Ivarsflaten2008; Rydgren, Reference Rydgren2008; Rooduijn et al., Reference Rooduijn, Burgoon, van Elsas and van de Werfhorst2017). This is particularly relevant within the context of an emerging transnational cleavage at the core of which lies a value conflict between those who support and those who reject multi-culturalism, cosmopolitanism, and globalization (Hooghe and Marks, Reference Hooghe and Marks2017). Theoretically, the importance of cultural values in shaping voting behaviour within the context of this cleavage, and empirically the strong association of cultural concerns over immigration and far right party support at the individual level have led to an emerging consensus in the literature that the increasing success of far right parties may be best understood as a ‘cultural backlash’ (Inglehart and Norris, Reference Inglehart and Norris2016), that is, a reaction to the perceived cultural threats posed by immigration.

Scholars recognize that there are theoretical reasons to expect the material aspects of immigration scepticism to also matter even within the context of a transnational cleavage. However, most empirical studies tend to support the cultural explanation. In terms of anti-immigration attitudes, findings regarding the labour-market competition hypothesis are highly contested (Chandler and Tsai, Reference Chandler and Tsai2001; Sniderman et al., Reference Sniderman, Hagendoorn and Prior2004; Citrin and Sides, Reference Citrin and Sides2008; Malhotra et al., Reference Malhotra, Yotam Margalit and Mo2013; Hainmueller and Hopkins, Reference Hainmueller and Hopkins2014). In terms of far right party support, economic explanations are often understood as secondary (Lubbers and Güveli, Reference Lubbers and Güveli2007; Lucassen and Lubbers, Reference Lucassen and Lubbers2012; Inglehart and Norris, Reference Inglehart and Norris2016) given the greater predictive power of cultural concerns over immigration at the individual level.

This article contests the view that immigration is a predominantly cultural issue and that the strong positive correlation between anti-immigration attitudes and far right party success necessarily and by default constitutes evidence in support of the cultural grievance thesis. We suggest that insufficient attention has been paid both to the predictive power of socio-tropic economic concerns over immigration and to the important distinction between galvanizing a core constituency on the one hand and mobilizing more broadly beyond this core constituency on the other. We test our argument using data on immigration concerns and the far right vote from 8 rounds of the European Social Survey (ESS) across 19 countries.

Findings from multilevel mixed-effects logistic regressions, cross-tabulations, scatter plots, and simulations show that both cultural and economic concerns over immigration increase the likelihood of voting for a far right party. While cultural concerns are a stronger predictor of far right party voting behaviour in a statistical sense, this does not automatically mean that they matter more for far right party success in substantive terms. What determines far right party success is the ability to mobilize a coalition of interests between core voters, that is, those primarily concerned with the cultural impact of immigration, and as large a subset as possible of peripheral voters, that is, the often numerically larger group of voters who are primarily concerned with the economic impact of immigration. This coalition is important for far right parties to extend their mobilization capacity beyond their core support base and thus make significant electoral gains.

This article proceeds as follows. First, we review the literature on immigration-related grievances and far right party support. Second, we present our argument, focusing on why mobilizing a coalition of voters with different types of immigration-related concerns is key to understanding far right party support. Third, we discuss our data and methods and proceed to test our argument empirically. The article concludes with some of the broader implications of our argument and directions for future research.

Immigration and ‘the cultural backlash’

The growing popularity of the far right is often linked to voters’ concerns over immigration (Rydgren, Reference Rydgren2008; Ivarsflaten, Reference Ivarsflaten2008; Arzheimer, Reference Arzheimer2009; Hainmueller and Hopkins, Reference Hainmueller and Hopkins2014; Rooduijn et al., Reference Rooduijn, Burgoon, van Elsas and van de Werfhorst2017). Studies find that immigration has a positive effect on far right parties, often irrespective of other factors (Golder, Reference Golder2003). Voters are affected either by actual immigrant numbers or by negative perceptions about immigrants, or both (Stockemer, Reference Stockemer2016). Far right parties, which ‘own’ the immigration issue (Van der Brug and Fennema, Reference Van der Brug and Meindert Fennema2007; Van Spanje, Reference Van Spanje2010) and share a common emphasis on nationalism (Vasilopoulou and Halikiopoulou, Reference Vasilopoulou and Halikiopoulou2015) or nativism (Mudde, Reference Mudde2007), sovereignty and policies that promote a ‘national preference’, are well placed to exploit immigration-related grievances and generate greater demand.

The question of immigration is particularly relevant within the context of an emerging transnational cleavage whose focal point is ‘the defence of national political, social and economic ways of life against external actors’ (Hooghe and Marks, Reference Hooghe and Marks2017: 2). The increasing salience of the immigration issue may be partly understood by this development, which has altered in-group and out-group dynamics. The transnational cleavage divides voters who hold cosmopolitan values from those who hold nationalist ones and can be best understood as a value conflict between voters who support and voters who reject multi-culturalism, globalization, as well as social and ethnic diversity. It is the result of rapid and profound value change in post-industrial societies (Inglehart and Norris, Reference Inglehart and Norris2016).

Because at the core of the transnational cleavage is a cultural – or value – conflict, scholars emphasize the importance of the cultural dimension of competition with immigrants in driving far right party success. The main proposition of the cultural grievance thesis is the perceived incompatibility between native and immigrant behavioural norms and cultural values (Golder, Reference Golder2016: 485). In other words, the argument here is that what drives far right party support is a fear that immigrants erode the national culture and traditional ways of life, thus threatening the value consensus upon which social norms are based. This cultural threat exacerbates prejudices against immigrants and prompts voters to opt for parties whose main agendas are centred on limiting immigration. According to this view, far right party support may be best understood as ‘a cultural backlash’, that is, a reaction to value change by those who reject universalistic values and place emphasis on national identity and fear the erosion of their cultural values (Inglehart and Norris, Reference Inglehart and Norris2016).

A large body of empirical research finds support for the cultural grievance hypothesis at the individual level (Lubbers and Güveli, Reference Lubbers and Güveli2007; Lucassen and Lubbers, Reference Lucassen and Lubbers2012; Inglehart and Norris, Reference Inglehart and Norris2016). This complements findings that pervasive cultural concerns are an underlying source of opposition to immigration and that culture is more important than the economy in evoking anti-immigration sentiments (e.g. Chandler and Tsai, Reference Chandler and Tsai2001; Sniderman et al., Reference Sniderman, Hagendoorn and Prior2004; Citrin and Sides, Reference Citrin and Sides2008; Hainmueller and Hopkins, Reference Hainmueller and Hopkins2014). Evidence includes the increasing relevance of post-material factors such as age and education, the endorsement of authoritarian values, mistrust in political institutions, and general resentment towards out-groups (Inglehart and Norris, Reference Inglehart and Norris2016). In addition, scholars emphasize the association between cultural concerns, nationalistic attitudes (Lubbers and Coenders, Reference Lubbers and Coenders2017), Euroscepticism (Van Elsas et al., Reference Van Elsas, Hakhverdian and Van der Brug2016), and class (Oesch, Reference Oesch2008). As part of this broader trend towards cultural-oriented explanations of far right party support, immigration scepticism tends to often be identified as a cultural issue (Inglehart and Norris, Reference Inglehart and Norris2016; Kaufmann, Reference Kaufmann2017).

Labour-market competition and economic grievances

Immigration, however, is a multi-faceted issue (Rydgren, Reference Rydgren2008; Mudde, Reference Mudde2012; Lucassen and Lubbers, Reference Lucassen and Lubbers2012; Malhotra et al., Reference Malhotra, Yotam Margalit and Mo2013). Indeed more recent scholarship stresses that the culture vs. economy debate is a false dichotomy (e.g. Gidron and Hall, Reference Gidron and Hall2017; Adler and Ansell, Reference Adler and Ansell2020), and that both dimensions matter, often shaping each other (Burns and Gimpel, Reference Burns and Gimpel2000). There are reasons to expect that competition with immigrants will likely be shaped not only by cultural but also by material interests. Indeed, the labour market competition hypothesis suggests that prejudices against immigrants have objective economic foundations (Scheve and Slaughter, Reference Scheve and Slaughter2001; Mayda, Reference Mayda2006; Dancygier and Donnelly, Reference Dancygier and Donnelly2013; Malhotra et al., Reference Malhotra, Yotam Margalit and Mo2013; Polavieja, Reference Polavieja2016; Hellwig and Kweon, Reference Hellwig and Kweon2016). Concerns might be either ego-tropic or socio-tropic, meaning that either those pessimistic about their personal economic situation and/or those pessimistic about the impact of immigration on the nation’s economy as a whole are more likely to have negative attitudes towards some migrant/ minority groups (Burns and Gimpel, Reference Burns and Gimpel2000; Hainmueller and Hopkins, Reference Hainmueller and Hopkins2014).

We might expect this to hold even in the context of the new transnational cleavage mainly prevalent in post-industrial societies. The decline of traditional cleavages does not necessarily imply that social and economic divisions are politically irrelevant, as new cleavages are ‘strongly shaped by the political legacy of traditional cleavages’ (Kriesi, Reference Kriesi1998: 165−167). While indeed comprehensive welfare states protect minimal standards of living (Inglehart and Norris, Reference Inglehart and Norris2016; Rehm Reference Rehm2016; Vlandas and Halikiopoulou, Reference Vlandas and Halikiopoulou2018), relative deprivation and inequality still affect voters (Colantone and Stanig, Reference Colantone and Stanig2018; Adler and Ansell, Reference Adler and Ansell2020; Engler and Weisstanner, Reference Engler and Weisstanner2020), and position in the labour market continues to have an impact on voting behaviour (Swank and Betz, Reference Swank and Betz2003; Rueda, Reference Rueda2007; Häusermann and Schwander, Reference Häusermann and Schwander2009; Vlandas, Reference Vlandas2013; Marx, Reference Marx2014; Halla et al. Reference Halla, Wagner and Zweimüller2017; Rovny and Rovny, Reference Rovny and Rovny2017; Kitchelt, Reference Kitchelt2018; Swank and Betz, Reference Swank and Betz2018).

A close association between labour market competition and immigration scepticism is more likely (Malhotra et al., Reference Malhotra, Yotam Margalit and Mo2013: 392). Social groups that have a greater exposure to labour-market competition are more likely to have an interest in limiting immigration because ‘an increase in the supply of immigrant workers is likely to lower their wages and/or to increase job insecurity’ (Polavieja, Reference Polavieja2016:396). These may include – but are not confined to – the lower social strata. Which social group will be affected depends on country, individual occupational source, employment sector, and skill level (Dancygier and Donnelly, Reference Dancygier and Donnelly2013). Skilled individuals are more likely to favour immigration in countries where natives are more skilled than immigrants (and oppose it otherwise) ‘because in this case immigration reduces the supply of skilled relative to unskilled labour and raises the skilled wage’ (Mayda, Reference Mayda2006:510). Individuals employed in growing sectors are more likely to support immigration than those employed in shrinking sectors (Dancygier and Donnelly, Reference Dancygier and Donnelly2013). Less-skilled workers are more likely to prefer limiting immigrant inflows (Scheve and Slaughter, Reference Scheve and Slaughter2001). There is also a policy effect as national protection policies may reduce hostility towards immigration (Artiles and Meardi, Reference Artiles and Meardi2014).

All this suggests, we should treat immigration as a complex issue and expect reasons other than xenophobic or racist attitudes including economic grievances (Rydgren, Reference Rydgren2008) to affect people’s attitudes towards immigration and the way they vote. To account for this, research has increasingly distinguished between the different sets of threats – mainly cultural and economic – posed by immigration, and their impact on anti-immigration attitudes (Sniderman et al., Reference Sniderman, Hagendoorn and Prior2004; Malhotra et al., Reference Malhotra, Yotam Margalit and Mo2013) and far right party support (Sniderman et al., Reference Sniderman, Hagendoorn and Prior2004; Rydgren, Reference Rydgren2008; Lucassen and Lubbers, Reference Lucassen and Lubbers2012).

The majority of studies, however, that consider and juxtapose both the economic and cultural dimensions of anti-immigration attitudes and far right party support find greater support for the cultural grievance thesis and tend to agree that, although both dimensions matter, the economy matters much less than culture. These conclusions are based predominantly – but not exclusively – on the strong predictive power of cultural variables at the individual level (Lubbers and Güveli, Reference Lubbers and Güveli2007; Lucassen and Lubbers, Reference Lucassen and Lubbers2012; for a review of studies explaining attitudes on immigration, see Hainmueller and Hopkins, Reference Hainmueller and Hopkins2014).

Why mobilizing an anti-immigrant voter coalition is key to understanding far right party success

Immigration is not just a cultural issue

This article questions the extent to which the stronger predictive power of cultural concerns over immigration necessarily implies that culture is always more important than the economy in driving far right party success. We argue instead that both cultural and economic concerns matter, albeit in different ways. Our argument responds to recent calls in the literature to refine and better explain the economic anxiety thesis (Mudde and Rovira Kaltwasser, Reference Mudde and Kaltwasser2018). We do so by paying more attention to voters’ socio-tropic economic concerns over immigration and to the size and coalition potential of voter groups with both cultural and economic concerns over immigration.

Specifically, our argument enfolds into two separate claims. First, while cultural concerns over immigration are indeed a stronger predictor of voting for the far right than economic concerns, the latter also have a predictive power that is not negligible. This is particularly true of socio-tropic concerns: people’s views about the impact of immigration on the economy motivate them to express opposition to immigration on economic grounds. While, however, scholars agree that socio-tropic drivers of anti-immigration attitudes ‘can be economic as well’ (Hainmueller and Hopkins, Reference Hainmueller and Hopkins2014:230) and that pessimism about the national economy is likely to predict restrictive immigration attitudes (Kinder and Kiewiet, Reference Kinder and Kiewiet1981; Citrin et al., Reference Citrin, Green, Muste and Wong1997; Hainmueller and Hopkins, Reference Hainmueller and Hopkins2014), this is often de-emphasized and under-theorized in cultural arguments about far right party support.

Second, we make the case that in order to understand a party’s electoral success we need to consider not just the predictive power of certain attitudes but also the ways in which they are incorporated into politics. This points to the crucial distinction between receiving support from a core constituency and being able to mobilize more broadly. A party is more likely to have a large electoral potential if ‘a substantial proportion of the voters agree with its political program’ (Van der Brug et al., Reference Van der Brug, Fennema and Tillie2005: 563). It must therefore broaden its support beyond its secure voting base in order to be electorally successful (e.g. Tilley and Evans, Reference Tilley and Evans2017). This entails mobilizing a coalition of interests between different social classes or groups with different preferences. In sum, the size of, and coalition potential between, groups plays a key role in explaining successful electoral performance.

Core and peripheral far right voters

Far right parties share a common emphasis on nationalism, or nativism, in their programmatic agendas (Mudde, Reference Mudde2007). They centre their political programmes on a purported conflict between in-groups and out-groups, postulating that the in-group must in all circumstances be prioritized at the expense of the out-group. Their signature is to propose nationalist solutions to all socio-economic problems (Vasilopoulou and Halikiopoulou, Reference Vasilopoulou and Halikiopoulou2015).

The broad umbrella of voters with nationalist concerns (Lubbers and Coenders, Reference Lubbers and Coenders2017) is a key far right party target group because these voters are more likely to identify with far right positions and the issues they deem salient. Far right parties have ownership of the immigration issue (e.g. Van Spagne, Reference Van Spanje2010) because the latter speaks to the debate about entitlement to national membership, and as such is directly linked to nationalism (Halikiopoulou and Vasilopoulou, Reference Halikiopoulou and Vasilopoulou2018). Voters with nationalist concerns relating to immigration, therefore, could significantly increase the electoral fortunes of far right parties given the rise in the salience of this issue within the context of the transnational cleavage (Hooghe and Marks, Reference Hooghe and Marks2017).

Nationalism, understood as the ‘attainment and maintenance of autonomy, unity and identity of a nation’ (Breuilly, Reference Breuilly, Ichijo and Uzelac2005: 16–17) is however multi-dimensional. Its different components include the ethnic, cultural, territorial, and economic (Halikiopoulou et al., Reference Halikiopoulou, Nanou and Vasilopoulou2012). Opposition to immigration can be linked to one, all, or some – in the form of a combination – of these components. Voters are likely to have different party preferences depending on the source of their grievance and the extent to which they identify with the proposed party’s nationalist platform. This suggests a distinction between core and peripheral voters, which we elaborate on below.

Traditionally, far right parties have been associated with ethnic nationalism and xenophobia (Halikiopoulou et al., Reference Halikiopoulou, Mock and Vasilopoulou2013). Core far right voters, which we term the ‘culturalists’, are more likely to be primarily concerned with the cultural threat posed by immigration and to identify with all elements of nationalism and, by extension, the entire far right party platform. Because their support of the far right is principled, and more specifically linked to a principled form of xenophobia (Rydgren, Reference Rydgren2008), they see far right parties as their natural home. Peripheral voters, on the other hand, identify only partially with this platform. As such, their support is more contingent. This includes groups primarily concerned with the economic impact of immigration, which we call ‘the materialists’. These voters are likely to support the prioritization of the in-group on economic grounds but do not necessarily identify with the other nationalist elements of far right agendas. Because their concerns are related to a weaker form of immigration scepticism (Rydgren, Reference Rydgren2008) and their out-group attitudes are not principled, they may be catered for by a number of other parties and their affinity with the far right is less strong.

The implication of this distinction between core and peripheral voter groups is as follows. While the culturalists are core supporters and hence more likely to vote for the far right, it does not automatically follow that they are more important. To be successful, far right parties can, and often do, draw on a subset of an often larger peripheral electoral group composed of materialists, whose preferences may be more likely to include other parties addressing their economic concerns about immigration. Using ESS data of 19 European countries (see Data section for more details), Figure 1 compares the distribution of economic and cultural concerns over immigration. It is clear from this figure that there are more respondents with economic concerns than with cultural concerns.

Figure 1. Distribution of respondents with cultural (panel above) and economic (panel below) concerns over immigration.

We argue that the ability to mobilize as large a subset of materialists determines far right party success. Sniderman et al.’s (Reference Sniderman, Hagendoorn and Prior2004:36) distinction between galvanizing a core constituency and mobilizing more broadly is crucial for our point: ‘politically [it] makes all the difference as it enlarges the portion of the public in support of these parties and/or the policies they advocate’. Mobilization can be brought about by situational triggers, which exacerbate voters’ socio-tropic economic concerns over immigration. The materialists may not be the core constituency of far right parties, but they are nevertheless important to these parties because they are highly likely to support them given their immigration skepticism. As a result, it is precisely materialist voters who need to be mobilized by far right parties and in many ways determine the broader electoral success of such parties.

Why might we expect some far right parties to be better able to mobilize materialists more than others? Supply-side literature has emphasized the shift from predominantly ethnic (or nativist) nationalist narratives, which draw on ascriptive criteria, to more civic narratives, which draw on ideological rationalizations of national belonging (Halikiopoulou et al., Reference Halikiopoulou, Mock and Vasilopoulou2013). This shift in turn allows these parties to extend their appeal to a broad range of immigration sceptics (Rydgren, Reference Rydgren2008). Part of this changing narrative is an explicit move away from market liberal positions (Kitschelt and McGann, Reference Kitschelt and McGann1995) to the adoption of welfare chauvinism (De Lange, Reference De Lange2007; De Koster et al., Reference De Koster, Achterberg and van der Waal2013; Ivaldi, Reference Ivaldi2015; Afonso and Papadopoulos, Reference Afonso and Papadopoulos2015; Afonso and Rennwald, Reference Afonso, Rennwald, Manow, Palier and Schwander2017), which draws on economic nationalism, thus speaking directly to those voters with material insecurities feeding concerns over immigration.

The importance of group size

Our point regarding the importance of the size of a given group is best illustrated with a simple hypothetical example, displayed graphically in Figure 2. Suppose the electorate is composed of 110 voters and all are concerned about immigration, but 10 feel culturally insecure about immigration (the culturalists), while the remaining 100 feel economically insecure about immigration (the materialists). Suppose further that in the last election, 5 out of 10 people in the culturalist camp voted for the far right so that they have a 50% probability of voting for the far right. By contrast in the materialist camp, 10 out of 100 voted for the far right so that they have a 10% probability of voting for the far right. Thus, in this example, a culturalist is ceteris paribus five times as likely as a materialist to vote for the far right. However, materialists are much more important to the success of far right parties than the culturalists. The materialist group determines far right party success because of its numerical majority despite the fact that individual concerns about immigration’s cultural impact have a stronger effect on individual far right party support than do concerns about its economic impact. Therefore, while it may well be that the core of support for far right parties objects to immigration on cultural grounds, it is the more economically oriented concerns that are especially influential in allowing these parties to expand beyond that core, and indeed those without immigration concerns. In other words, in order to increase their electoral chances, far right parties must mobilize immigration-related grievances beyond culture. In online Appendix 4, we demonstrate using a larger sample of hypothetical data that it is indeed possible for the characteristics associated with a much smaller group of far right supporters to have a larger effect on far right voting.

Figure 2. Hypothetical example illustrating the importance of group size.

The point of this hypothetical example is to show that stronger predictive power in a statistical sense does not necessarily equate to substantive importance in a theoretical and empirical sense. This explains why we cannot infer from the stronger predictive power of individual cultural concerns over voting for far right parties that they necessarily matter more for far right party success at the national level in substantive terms. The assumption that the predictive power of a variable at the individual level equals substantive importance at the national level suffers from an atomistic – or individualistic – fallacy, which consists of ‘formulating inferences at a higher level based on analyses performed at a lower level’ (Hox, Reference Hox2010: 3). Because ‘relationships among variables that hold at one level do not necessarily hold at another level of hierarchy’ (Croon and Veldhoven, Reference Croon and van Veldhoven2007:45), drawing national level conclusions from individual level results is potentially as problematic as inferring individual level dynamics from national level results (i.e. an ecological fallacy). The attempt to make such inferences overlooks the composition dimension or, in other words, the size of the group that shares this particular concern and how widespread this concern actually is among the electorate. Thus, while some variables may be stronger predictors, this does not automatically tell us what matters more in the sense of accounting for this party’s electoral success. This, however, has so far been neglected in the literature on far right voting.

Research design

Data

In order to examine how and to what extent far right party success depends on mobilizing grievances over the cultural and economic impact of immigration, we combine eight wavesFootnote 1 of the ESS, which has been used by previous research on both immigration attitudes and far right support (see, e.g., Citrin and Sides, Reference Citrin and Sides2008; Ivarsflaten, Reference Ivarsflaten2008; Rydgren, Reference Rydgren2008; Lucassen and Lubbers, Reference Lucassen and Lubbers2012; Inglehart and Norris, Reference Inglehart and Norris2016; Rooduijn and Burgoon, Reference Swank and Betz2018).

We adopt the terminology ‘far right’ in accordance with Lucassen and Lubbers (Reference Lucassen and Lubbers2012) and examine all parties that propose nationalist solutions to a variety of socio-economic problems (Vasilopoulou and Halikiopoulou, Reference Vasilopoulou and Halikiopoulou2015), compete along the national identity axis (Ellinas, Reference Ellinas2011), and ‘own’ the immigration issue (Van Spagne, Reference Van Spanje2010; Lucassen and Lubbers, Reference Lucassen and Lubbers2012). Our analysis includes 31 parties in 19 European countries. In each country-wave, respondents were asked which political party they voted for in the last national election. Our dependent variable measures far right party support and is binary: it is coded 1 if the respondent voted for a far right party and 0 if the respondent voted for another party. The countries, parties, ESS round in which they are included, and relevant sources corroborating our classification are listed in online Appendix 1.

Our independent variables include questions that ask respondents whether they think their country’s cultural life is undermined (0) or enriched (10) by immigrants (henceforth ‘cultural concerns about immigration’) and whether they think immigration is bad (0) or good (10) for their country’s economy (henceforth ‘economic concerns about immigration’). In each case, we reverse the scale so that higher values indicate greater concern.

These two variables are partly correlated (0.62) and as such, one may contend that they should be treated as a single variable. However, recent studies have treated the two as separate, assessing the extent to which each type of threat affects attitudes and voters’ propensity to vote for the far right and showing that the two sets of threats ‘independently affect prejudice’ (Lucassen and Lubbers, Reference Lucassen and Lubbers2012: 548; see also Sniderman et al., Reference Sniderman, Hagendoorn and Prior2004). For instance, Lucassen and Lubbers (Reference Lucassen and Lubbers2012) use data from the first round of the ESS to juxtapose cultural and economic threats over immigration and far right party support in 11 European countries. Similarly, using data from the first round of the ESS, but focusing on six European countries, Rydgren (Reference Rydgren2008: 738) also differentiates between racists, xenophobes, and immigration sceptics arguing these dimensions ‘overlap asymmetrically’. In addition, Lubbers and Güveli (Reference Lubbers and Güveli2007) juxtapose cultural ethnic and economic concerns over immigration and their impact on voting for LPF using the Dutch sample of the ESS. Finally, also focusing on the Netherlands and using a series of experiments, Sniderman et al. (Reference Sniderman, Hagendoorn and Prior2004: 35) contrast the importance of considerations of national identity and economic advantage in ‘evoking exclusionary reactions to immigration minorities’. These studies point to the importance of conducting further research that distinguishes cultural from economic threats (Lucassen and Lubbers, Reference Lucassen and Lubbers2012: 576) by using larger samples and including more cases. Following this literature, we not only treat the two variables as separate but also run a variety of tests paying close attention to the extent to which they differ and overlap.

Our controls include age, gender, education (in years), occupationFootnote 2, and level as well as source of incomeFootnote 3. While waves 4−8 use the standard 10-income decile classification, the first 3 waves of the ESS rely on a 12-category variable. We therefore create two separate variables: the first is coded 1 if the respondent is in the bottom 50% (bottom 5 deciles in one case and bottom 6 categories in the second case) and 0 otherwise; the second variable is coded 1 if the respondent is in the bottom 10% for the decile variable and in bottom 2 categories for the 12-category variable. Finally, we control for partisanship, Euroscepticism, and trust in institutions. An 11-point left-right self-placement scale is used to capture the ideological location of the respondents. To account for Euroscepticism, we include a variable capturing trust in the European Parliament (0 – complete trust at all; 10 – no trust at all). There are several variables asking respondents about their levels of trust. We use ‘trust in national parliament’ but show results are the same if we use different forms of trust such as in the legal system, politicians, and political parties (see Table A3.2 in online appendix). All summary statistics are shown in Table A2.1 in online appendix.

Method

Our methodological approach is as follows. First, we use multilevel mixed-effects logistic regressions to examine whether cultural and economic individual concerns about immigration have an effect on voting for the far right and which of these two concerns has stronger predictive power. The standard errors are robust and clustered by country-wave.

Second, we need to ascertain the share of respondents that have each type of concern and vote for far right parties. This speaks to our point about the size of voter groups with different concerns over immigration. A series of tabulations reveals that there are more individuals with economic than with cultural concerns over immigration and that those who are concerned about the impact of immigration on the economy are more important to the far right in numerical terms than those concerned with its impact on culture.

Third, we examine the implications of our argument at the national level. We focus on the cross-national variation in far right party support by plotting the share of materialists and culturalists that vote for the far right against the overall percentage of the far right electorate. More formally, we also test whether the impact of being a culturalist or a materialist on the probability of voting for the far right at the individual level has a bearing on far right party support at the national level. In a first step, we run a series of logistic regression analyses for each country-wave in our sample.Footnote 4 In a second step, we extract the country-wave coefficients for the two variables capturing economic and cultural concerns over immigration, respectively. Then we regress the national level share of far right party support as the dependent variable on these two coefficients as two independent variables. This allows us to assess whether the individual level predictive power of concerns correlates with national level success.

Finally, we run a series of simple simulations to evaluate the extent to which artificially varying the distribution of individual economic and cultural concerns in a given country would result in a different electoral score for the far right. We run a series of logistic regression analyses for each country in our sample. Using the coefficients from these regressions, we calculate individual predicted probabilities for different distributions of economic and cultural concerns: everyone scores 0, everyone scores the true distribution of concerns, and everyone scores 10. We then predict country level far right party support for all possible combinations of these three levels of economic and cultural concerns (i.e. 3×3 = 9 scenarios).

Results: the impact of immigration concerns on far right party success in Europe

The predictive power of economic and cultural concerns

Table 1 reports the coefficients for our key independent variables.Footnote 5 In column 1, we can see that both economic and cultural concerns have a positive and statistically significant association with the probability of voting for the far right. Cultural concerns seem to have stronger predictive power, as we will confirm later by calculating predicted probabilities for different scenarios in a second step. There is a positive and significant association between being male and voting for the far right, while older individuals appear less likely to support the far right. By contrast, being in the bottom of the income distribution has no statistically significant association (column 1).Footnote 6 The subsequent columns include additional controls stepwise, and our results concerning the impact of economic and cultural concerns are stable. Having higher education is negatively associated with support for the far right. These results are consistent with literature that identifies the typical far right voter as a young male, with a low level of education (Lubbers and Scheepers, Reference Lubbers and Scheepers2002; Arzheimer, Reference Arzheimer2009; Lucassen and Lubbers, Reference Lucassen and Lubbers2012; Golder, Reference Golder2016).

Table 1. Economic and cultural concerns over immigration and far right voting

Note: This table presents the results from a multilevel mixed-effects logistic regression taking into account the hierarchical nature of the data; the standard errors are robust and clustered by country-wave. ***p < 0.01, **p < 0.05, *p < 0.1. Column 9 reports the percentage points change in the predicted probability when the independent variable is set at its maximum value minus when it is set at its minimum value, holding all other independent variables at their mean value. Thus, for instance, the predicted probability of voting for the far right is 2.03% for an individual with the lowest economic concerns and 5.64% for an individual with the highest economic concerns and column therefore reports a 3.61 percentage points change in predicted probability.

We find mixed evidence regarding source of income. Being self-employed and receiving a pension are both negatively associated with voting for the far right. The statistical significance of receiving ‘other (non-unemployment/non-pension benefits) social benefits’ is not stable across specifications. We also find a positive and significant association between being unemployed and voting for the far right in all specifications. In terms of occupation, the highly skilled professionals have the strongest negative association with the probability of voting for the far right, while workers in skill-specific craft occupations and low-skilled workers employed as operators (both occupations capturing core parts of the manufacturing sector) are most likely to vote for the far right. Right-leaning individuals are associated with higher support for the far right, while trust in national and European institutions is negatively associated with support for the far right (columns 7 and 8).

In order to assess which variable has the greatest effect on the probability of voting for the far right, we calculate the difference in the predicted probability when taking the maximum vs. the minimum value of each independent variable (see column 9, Table 1). The greatest effects on the predicted probabilities can be observed for the following variables: left-right scale; cultural concerns over immigration; economic concerns over immigration; education and trust. Next, with respect to occupations, craft, operator, and service occupations have the highest effect on predicted probabilities. Being male, unemployed, or a clerical worker also has a sizeable effect (above 1 percentage point higher predicted probabilities). By contrast, the magnitude of the effect of certain occupations (e.g. agriculture and professionals) and different income sources, such as pensions or self-employment, is lower (under 1 percentage difference).

We carry out a number of robustness checks. The results are the same for economic and cultural concerns over immigration when including the borderline Law and Justice (PiS) in the analysis (see online Appendix 5). We also reproduce our results with alternative measures of trust (see Table A3.2 in online appendix). Next, we change the operationalization of our key independent variables. We rerun the results of column 8 in Table 1 using a binary version of our initial variables measuring cultural and economic concerns over immigration. Our binary economic concerns over the immigration variable are coded 1 if the respondents choose a response above 5 to the question of whether immigration is good or bad for the country’s economy, and 0 otherwise. Similarly, the binary cultural concerns over the immigration variable are coded 1 if respondents choose a response above 5 to the question of whether immigration is good or bad for the country’s culture, and 0 otherwise.

Cross-tabulating these two variables reveals that 55.6% of respondents have neither economic nor cultural concerns, 8.2% have cultural but not economic concerns, 15.2% have economic but not cultural concerns, and 20% have both types of concerns over immigration (see Table A3.6 in online appendix). The results in Table A3.3.a in online appendix confirm that being a culturalist has greater predictive power than being a materialist. To address potential criticisms about treating economic and cultural concerns as two separate variables, we add an interaction term and the results are the same (see Table A3.4 in online appendix). We also reproduce these results using binned variables for economic and cultural concerns: the stronger effect of cultural concerns over immigration is confirmed using this different operationalization (see Table A3.5.b in online appendix).

Using the same model as in column 8 in Table 1, we can predict the probability of voting for the far right for individuals with different levels of economic and cultural concerns over immigration. As Figure 3 shows, having cultural concerns has a stronger effect on the predicted probability of voting for the far right, but economic concerns also matter, especially among those with cultural concerns. Even among those with no cultural concerns, an individual with strong economic concerns would be more than twice as likely as an individual with no economic concerns at all to vote for the far right. These results indicate that overall cultural concerns over immigration are a stronger predictor of far right party support, but that economic concerns also matter.

Figure 3. Predicted probability of voting for the far right for different combinations of economic and cultural concerns over immigration. Note: The predicted probabilities were calculated using the coefficients from column 8 in Table 1.

We check the robustness of these results as well. First, as above, the findings are similar when including PiS in the analysis (see Figure A5.1 in online appendix). Second, we reproduce Figure 3 while including an interaction term between economic and cultural concerns over immigration (see Figure A3.2 in online appendix). The results are similar but the impact of economic concerns is now stronger among those with very low cultural concerns and weaker among those with very high cultural concerns. Third, we recalculate and plot the predicted probability using the two binary versions of cultural and economic concerns with and without interaction terms: both cultural and economic concerns increase the likelihood of supporting a far right party (Figures A3.3 and A3.4 in online appendix). Overall, our findings suggest that both economic and cultural concerns have a statistically significant positive effect on the probability of voting for the far right, while the predictive power of cultural concerns is stronger.

Extending support beyond the core far right constituency

Recall Figure 1, which displays the tabulations for economic and cultural concerns over immigration. We can see that at every point of the scale the share of those with economic concerns is greater than for those with cultural concerns. If we use a cut-off point of 5 for each type of concern, we can observe that nearly 57% of our sample scores under the cut-off point for both economic and cultural concerns, 8.2% are culturalists but not materialists, 15% are materialists but not culturalists, and nearly 20% are above this cut-off point for both economic and cultural concerns (Table A3.6 in online appendix). This indicates that the primacy of culture as an explanation of anti-immigration attitudes is not as straightforward as suggested in the literature: even if the predictive power of cultural concerns is greater, there are more people with economic concerns than people with cultural concerns about immigration. In other words, while culturalists are more likely to vote for the far right, materialists are a numerically larger group.

Figure 4 offers a graphical illustration of the number of voters and non-voters for the far right for different levels of economic and cultural concerns. While the share of far right voters for those with cultural concerns is higher (top panel) than the share of these voters among those with economic concerns (bottom panel), there are many more people with economic concerns and as a result they remain more important to the far right. For instance, in this example there are 4182 respondents with economic concerns above 5 who voted for far right compared to 3925 respondents with cultural concerns above 5 who voted for the far right (Table A2.3 in online appendix).

Figure 4. Far right voters and concerns over immigration (0 – low; 10 – high).

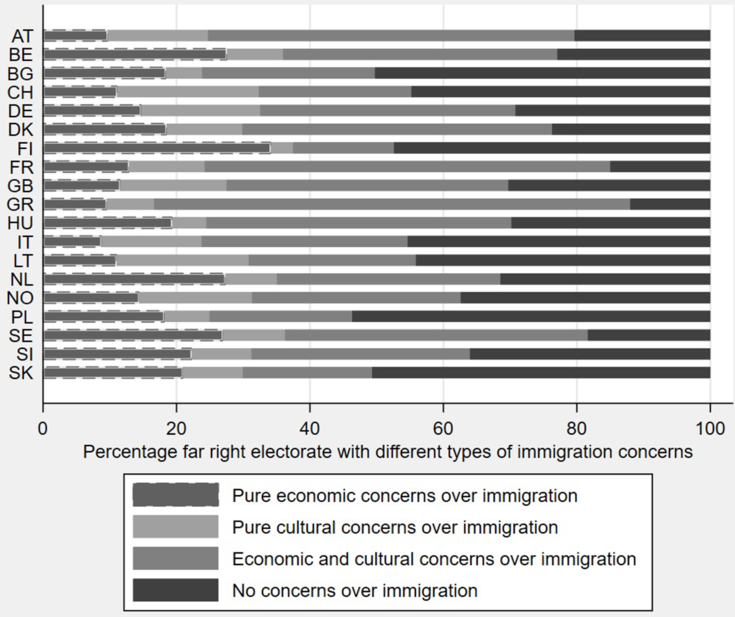

In Figure 5, we plot the distribution of respondents with different types of concerns (just economic, just cultural, both, and neither type of concerns) for each country’s far right electorate. In a range of countries, those with pure economic concerns are more numerous among the far right electorate than those with pure cultural concerns. In addition, when added to those without any type of concerns, those with pure economic concerns are more numerous than those with both economic and cultural concerns (and the latter picture is even starker if a higher cut-off point of 7 is used to identify concerns – see Figure A2.9 in online appendix). Consequently, removing respondents with pure economic concerns from the far right electorate results in a much lower electoral score than removing those with pure cultural concerns in many countries (see Figure A2.10 in online appendix).

Figure 5. Distribution of concerns among far right voters (cut-off point of 5).

Cross-national variation in far right party support and immigration concerns

Thus far, we have argued that both economic and cultural concerns matter for far right party success: having these concerns increases the probability of voting for the far right. In addition, these concerns matter in different ways. While cultural concerns have a stronger predictive power, there are often more people with economic concerns and this group is therefore important for far right party success in numerical terms.

What do these results mean for the cross-national variation in far right party support? If economic concerns were of no or of secondary importance to far right party success, then the share of materialists who vote for the far right should have little bearing on the total share of the far right vote at the national level. However, the evidence is not consistent with this expectation. The bottom panel of Figure 6 plots the country average percentage of far right party votes against the percentage of far right voters among those with economic concerns. The fit appears strong: countries with high average far right party support tend to exhibit substantial support for those parties from materialists (the correlation is above 0.9 with p-value < 0.001 and R-squared of 0.931). If we plot instead the country average percentage of far right party votes against the percentage of far right voters among those with cultural concerns, a similar picture emerges and the correlation remains strong but the R-squared has a lower 0.870 (see top panel of Figure 6).

Figure 6. Percentage of far right voters among the total population vs. among voters with immigration concerns. Note: A cut-off point of 5 is used to identify who has concerns.

Next, we investigate the extent to which the strong predictive power of cultural concerns over immigration at the individual level necessarily translates into higher far right party support at the national level. In other words, is it the case that countries where culturalists are very likely to vote for the far right have particularly high levels of far right party support? To answer this question, we create a new data set with three variables. The dependent variable is the average far right party vote in a given country-wave. Two independent variables capture the predictive power of each type of concern − cultural and economic − over immigration on voting for the far right at the individual level. These two variables are created by extracting the coefficients from a series of logistic regressions for each and every country-wave in our original sample.

The results suggest that there is no statistically significant correlation between the predictive power of cultural concerns on the individual probability of voting for a far right party in a given country-wave and national level far right party votes in that country-wave. By contrast, the predictive power of economic concerns on the individual probability of voting for a far right party in a given country-wave is significantly and positively correlated with the country-wave average far right party vote (see Table 2). In sum, countries where culturalists are highly likely to vote for the far right, as captured by higher coefficients, do not necessarily exhibit high far right party support. This constitutes further evidence that the predictive power of individual level cultural concerns is not enough to explain a party’s electoral success.

Table 2. Individual level coefficients and far right party success at the country-wave level

Notes: Robust standard errors in parentheses, ***p < 0.01, **p < 0.05, *p < 0.1. This regression is run using a country-wave level data set. The dependent variable is the country-wave average far right party success. The two independent variables are coefficients from the respective country-wave logistic regression of individual far right party votes on economic and cultural concerns, with a series of individual level controls. Thus, each coefficient captures the size of the impact of an individual having economic and cultural concerns, respectively, on the probability of voting for the far right in that specific country-wave.

Simulations

Finally, using a series of country level logistic regressions we simulate different scenarios to assess precisely how the predicted country level far right party support varies depending on the distribution of respondents with 0, actual, or 10 on the scale of economic vs. cultural concerns over immigration. This is shown in Figure 7 (for country specific graphs, see Figure A4.1 in online appendix). To illustrate, the square sign for Austria indicates that predicted support is highest when both economic and cultural concerns are set at 10 for every single respondent in that country, and lowest when these are set at 0. The key piece of information here is to compare the predicted support for the actual distribution of both types of concerns to what happens to this prediction when either cultural or economic concerns are set at their maximum vs. minimum values.

Figure 7. Simulations of predicted country level far right party support for different hypothetical distributions of economic and cultural concerns.

Setting economic concerns for everyone at 0 results in lower predicted national support than doing the same for cultural concerns in four countries: Sweden, Norway, the Netherlands, and Bulgaria. In a number of countries, setting cultural concerns at 0 results in lower predicted national support than doing the same for economic concerns (but only by less than 1%): Greece, France, Finland, Denmark, and Belgium. In the remaining cases, setting all respondents to have 0 cultural concerns results in larger falls in support than doing the same for economic concerns (the largest differences are seen in Switzerland, Hungary, Poland, and Slovakia). Setting each type of concern to their maximum values reveals that in three countries economic concerns play a larger role (Norway, Netherlands, and Bulgaria), in six countries cultural concerns play a bigger role but by less than 2%, and in the remaining cases setting cultural concerns to their maximum values results in a higher score by more than 2% (see Table A4.4 in online appendix for specific numbers).

In sum, having individual cultural concerns over immigration has a strong impact on voting for far right parties, but economic concerns also increase support for the far right and there are more people with economic than cultural concerns, both in the broader population and among many successful far right parties’ electorates. In many – but not all – cases, an electorate that has maximum cultural concerns over immigration would in principle yield the maximum support for far right parties. However, this is not always the case and the predictive power of economic concerns at the individual level is correlated with national level support, while this is not the case for cultural concerns. Thus, mobilizing those with economic concerns over immigration is always important to far right party success and in many cases the driving force of their success.

Conclusion

This article suggests that studies focusing on the anti-immigration drivers of far right party support should pay more attention both to voters’ socio-tropic economic concerns and the important distinction between receiving votes from a core constituency on the one hand and the ability to extend support beyond this core constituency on the other. In a nutshell, our argument is that while cultural concerns over immigration may be a stronger predictor of far right party voting, this does not mean that culture necessarily and always matters more for far right party success than the economy. This is because, as shown in our analysis of eight waves of ESS data concerns about the impact of immigration on the country’s economy as a whole are statistically significant and have a strong positive association with voting for the far right.

In addition, those who dislike the impact of immigration on the economy are important to the far right in numerical terms as they allow these parties to extend their support beyond their secure voting base. These findings confirm that the far right parties that are more likely to be electorally successful are those able to mobilize a ‘winning anti-immigrant coalition’ which consists of both the vast majority of the few core supporters who care strongly about the cultural impact of immigration and a subset of the numerically larger group of voters who care strongly about the economic impact of immigration.

This article makes several contributions by challenging a key assumption, which is increasingly becoming consensus in the literature, that culture predominantly drives support for the far right within the context of an emerging transnational cleavage.

First, by presenting an empirical reassessment of theories that examine the relationship between different concerns over immigration and success of far right parties using eight waves of ESS survey data, we show how and why economic considerations over the impact of immigration also drive far right party success. Existing literature in the field has repeatedly stressed the need for further research that nuances the role of economic anxiety (Mudde and Rovira Kaltwasser, Reference Mudde and Kaltwasser2018), distinguishes between the perceived economic and cultural threats posed by immigration and their effect on far right support (Lucassen and Lubbers, Reference Lucassen and Lubbers2012: 549), and identifies ‘how, when and why’ socio-tropic concerns matter (Hainmueller and Hopkins, Reference Hainmueller and Hopkins2014: 225). This article addresses this gap in the literature, and in doing so it brings the economy back in the debate on far right voting within the context of the transnational cleavage.

Second, we point to an important methodological problem arising from inferring what ‘causes’ a cross-national level phenomenon using individual level findings. While the ecological fallacy has been front and centre of the recent drive to use more individual voting data rather than national electoral results, little attention to date has been paid to the reverse risk of the individualistic, or atomistic, fallacy. In this article, we advocate for paying closer attention to descriptive information such as the size and composition of different far right voter groups. We also illustrate the kinds of tests and simulations that researchers can carry out to explore complex multilevel interactions and assess the severity of the atomistic fallacy.

Our article opens avenues for future research. It could form the basis of targeted examinations of the role of economic drivers of far right party support that focus more closely on the specific mechanisms that link voting preferences to far right party success. For example, the adoption of a targeted sampling strategy (see Malhotra et al., Reference Malhotra, Yotam Margalit and Mo2013) might identify trends not prevalent among the general population, and hence not visible in surveys such as the ESS.

Another important issue raised in our article is the multi-faceted character of the immigration issue and the extent to which this multi-dimensionality suggests that immigration should not be treated as merely a cultural variable in theories of far right party support. This point has been previously raised (Rydgren, Reference Rydgren2008), and more work is needed, extending beyond the economy-culture dichotomy. For instance, this could include the extent to which voters are concerned about the impact of immigration on their personal safety, because of increased crime levels, terrorism and deteriorating public services. A related point is that of data availability: the research community would benefit from new or extended surveys that include more elaborate questions on the cultural and security threat dimensions of anti-immigration attitudes. This will allow us to more adequately measure and operationalize anti-immigration attitudes in a manner that captures all the threat dimensions that trigger them.

Finally, demand-side insights emphasized here can be linked to supply, both in terms of far right party strategies and in terms of other parties such as those on the centre-right that also draw on the increasing salience of immigration. Indeed, our article has briefly discussed some conclusions from recent literature, which show that far right parties focus increasingly on social welfare (Afonso and Papadopoulos, Reference Afonso and Papadopoulos2015; Afonso and Rennwald, Reference Afonso, Rennwald, Manow, Palier and Schwander2017; Röth et al., Reference Röth, Afonso and Spies2018; Halikiopoulou and Vlandas, Reference Halikiopoulou and Vlandas2019), in order to appeal to those voters with economic concerns, thus complementing our findings. The field would benefit significantly from more mixed-methods approaches that focus on the complementarity between demand and supply-side dynamics and the ways in which multiple and overlapping societal grievances are targeted by far right parties.

Overall, our findings have significant policy implications. If we are right, then the economic dimension of far right party support is often underestimated. In order to address the success of these parties, policy-makers need to pay attention not only to policies related to national identity and cultural values but also to the underlying economic insecurities that trigger those anti-immigration sentiments, which in turn often translate in voting for the far right.

Acknowledgements

We thank David Rueda, Andy Eggers, Jane Gingrich, Desmond King, David Weisstanner, and José Fernández Albertos for discussions on this topic and/or comments on previous drafts. We are grateful for the feedback we received while presenting previous versions of this paper at the University of Reading, the MFO and St Antony’s college (Oxford), and the APSA, Espanet and the International Public Policy Association conferences. We are indebted to Michael Ganslmeier for excellent research assistance. Finally, we would like to thank the editors and three anonymous reviewers of the EPSR for their insightful comments.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S175577392000020X.