Introduction

The institutionalization and professionalization of legislatures in the second half of the twentieth century created politicians who, in Weber’s (Reference Weber, Garth and Mills1946 [1919]) famous analysis, lived “for” politics and also “off” politics. “Career politicians”, as King (Reference King1981) termed them, have since become a dominant and controversial presence across the liberal democratic world (Squire, Reference Squire1993; Searing, Reference Searing1994; Norris, Reference Norris1997; Saalfeld, Reference Saalfeld, Müller and Saalfeld1997; Shabad and Slomczynski, Reference Shabad and Slomczynski2002; Cairney, Reference Cairney2007; Koop and Bittner, Reference Koop and Bittner2011; Heuwieser, Reference Heuwieser2018). Many academics believe such politicians are essential for effective governance (Best and Cotta, Reference Best, Cotta, Best and Cotta2000, pp. 21–22; Shabad and Slomczynski, Reference Shabad and Slomczynski2002; Fisher, Reference Fisher2014). Others believe their behavior fuels the “anti-politics” of national populism and undermines political legitimacy (Wright, Reference Wright2013; Savoie, Reference Savoie2014; Allen, Reference Allen2018; Clarke et al., Reference Clarke, Jennings, Moss and Stoker2018; Levitsky and Ziblatt, Reference Levitsky and Ziblatt2019).

Cumulative research in this field has been greatly impeded, however, by conceptual confusion (Allen and Cairney, Reference Allen and Cairney2017). Career politicians are often vaguely and inconsistently distinguished from “professional politicians,” “careerists,” and “the political class.” Sometimes these terms are used as synonyms. This paper aims to clarify the career-politician concept by identifying its principal dimensions, measuring them, and testing the validity of these measures so that they can be used with confidence in empirical research. We eschew “classic” concept construction and instead turn to Wittgenstein’s (Reference Wittgenstein1953) “family resemblance” approach (see Goertz, Reference Goertz2006). We argue that “career politician” is best understood as a multidimensional concept in which the absence of some characteristics can be compensated by the presence of others.

After reviewing the academic literature and wider political discourse, we extract four principal dimensions. Career politicians are associated with strong vocational commitment and political ambition. They are also associated with having narrow occupational backgrounds and limited life experiences, but no particular characteristic seems either necessary or sufficient. From this viewpoint, we move beyond thinking about career politicians in binary terms. The dimensions associated with the concept are all continuous variables. We may use typologies and prototypes to discuss the subject, but being a career politician is clearly a matter of degree.

Finally, we develop measures of the four dimensions and validate them using a data set on British MPs. Career politicians may be found in any established political institution. Our focus on the British House of Commons is partly a reflection of the concept’s initial association with UK politics (King, Reference King1981; Riddell, Reference Riddell1996) but primarily a consequence of the rich data we have collected. A large number of MPs were interviewed in 1971–1974 and re-interviewed in 2012–2016.Footnote 1 The 1970 General Election was a watershed for the rise of full-time career politicians. MPs were now provided with staffing allowances and other benefits, and remunerated sufficiently to enable long-term careers (Norton, Reference Norton, Müller and Saalfeld1997, pp. 23–25; Rush and Cromwell, Reference Rush, Cromwell, Best and Cotta2000, p. 488; Rush, Reference Rush2001; Jun, Reference Jun, Borchert and Zeiss2003; Cairney, Reference Cairney2007; Allen, Reference Allen2013; Langdon Reference Langdon2015). After 1970, these career politicians steadily replaced amateurs and part-timers (Riddell, Reference Riddell1996, pp. x–xi, 14). The virtue of our sample is that it includes many examples of each, which facilitates comparisons between them.

Our measures of career politicians draw on the interviews conducted in 1971–1974 (for convenience we refer to them as 1974). These involved 521 MPs, an 83% response rate. The face-to-face recorded and transcribed sessions lasted 90 minutes on average, ranging from 30 minutes to five hours. They included interviews, at the same response rate, with ministers and opposition frontbench spokesmen. All were given written guarantees of anonymity. The interviews probed parliamentary careers and psychological characteristics embedded in career performances. Respondents completed paper and pencil forms including a pre-parliamentary occupational history. For the present paper, we coded and added to this data information on MPs’ pre-parliamentary occupations, years of service in the House of Commons, retirements, and circumstances of these retirements.

Theoretical claims and political critiques

Professional politicians were discovered by Weber (Reference Weber, Garth and Mills1946[1919]) and introduced to political scientists as “career politicians” by King (Reference King1981). Subsequent academic and popular treatments of the subject endorsed many of King’s main points but reworked the term’s focus (Rush, Reference Rush1994, Riddell, Reference Riddell1996; Reference Riddell2011; Paxman, Reference Paxman2002; Oborne, Reference Oborne2007). Over time, the concept became increasingly multidimensional.

To identify the principal dimensions of “career politician,” we apply a research design constructed by Goertz (Reference Goertz2006). The first step is to examine how the term is used in academic and political discourse. The concept’s principal dimensions can then be derived from these sources and reconstructed systematically without losing touch with the political worlds in which it lives. We approach this task by briefly considering positive and negative claims about career politicians.

Many of the positive claims about career politicians stem from students of legislative professionalization, who value committed, full-time politicians for their contributions to good governance (Polsby, Reference Polsby1968; Best and Cotta, Reference Best, Cotta, Best and Cotta2000; King, Reference King2000; Shabad and Slomczynski, Reference Shabad and Slomczynski2002; Borchert, Reference Borchert, Borchert and Zeiss2003; Borchert and Zeiss, Reference Borchert and Zeiss2003; MacKenzie, Reference MacKenzie2015).

For instance, the House of Commons’ performance improved when professionals gradually replaced amateurs on the backbenches (King, Reference King1981, p. 280). MPs now work harder for their constituents and pay more attention to citizens’ needs and views (Riddell, Reference Riddell1996, p. 24; Reference Riddell2011, p. 83; Squire, Reference Squire2007). They also work harder on policy advocacy and oversight of the executive (King, Reference King1981, p. 280; Searing, Reference Searing1994; Norton, Reference Norton, Müller and Saalfeld1997, pp. 22–23, 27; Saalfeld, Reference Saalfeld, Müller and Saalfeld1997, p. 44; Jun, Reference Jun, Borchert and Zeiss2003, pp. 168–69; Riddell, Reference Riddell2011, p. 83). They are said to be more assertive and independent than their predecessors (Smith, Reference Smith1978; Rush and Cromwell, Reference Rush, Cromwell, Best and Cotta2000, p. 489; Jun, Reference Jun, Borchert and Zeiss2003, p. 176; Allen and Cairney, Reference Allen and Cairney2017, p. 20; Heuwieser, Reference Heuwieser2018, p. 334; c.f. Kam, Reference Kam2006; Hardman, Reference Hardman2018; O’Grady, Reference O’Grady2019, p. 549).

Career politicians are also praised for bringing with them relevant political experience (Riddell, Reference Riddell1996, pp. 306–307; Jun, Reference Jun, Borchert and Zeiss2003, p. 175; Allen, 2013; Reference Allen2018, pp. 54, 61; Fisher, Reference Fisher2014; Crewe, Reference Crewe2015, pp. 114–115). Many come from political apprenticeships and politically allied occupations like public relations, journalism, teaching, and academia. They understand arcane legislative rules and procedures (Squire, Reference Squire2007), are disposed toward compromise (Riddell, Reference Riddell1996, pp. 270–271; Borchert, Reference Borchert, Borchert and Zeiss2003, 20), and are able to digest information and presumably make better political judgments (Squire, Reference Squire2007).

Other commentators, however, emphasize career politicians’ lack of extra-political interests, knowledge, and experience (King, Reference King2015, pp. 71–72). Their predecessors had been prominent industrialists, stockbrokers, landlords, successful barristers, leaders in other professions, manual workers, and trade-union officials. Most career politicians today have not had such experience. Some of them, recently branded as “ultra” career politicians, advance from political activism at university to become MPs’ researchers, assistants, or think-tank staffers, and, soon after being elected themselves, expect preferment and promotion (Goplerud, Reference Goplerud2015).

The narrow background of career politicians matters for several reasons. In the first place, it encourages middle-class homogeneity and excludes people and perspectives from diverse backgrounds (Allen, 2013; Reference Allen2018; Durose et al., Reference Durose, Richardson, Combs, Eason and Gains2013; Abbott, Reference Abbott2015; Heath, Reference Heath2015; King, Reference King2015). It further reduces career politicians’ experiential knowledge of other policy areas (Oborne, Reference Oborne2007; King and Crewe, Reference King and Crewe2014, p. 208; Kettle, Reference Kettle2015). Career politicians also have limited life experience in the real world. They lack maturity and judgment (Wright, Reference Wright2013; Allen and Cairney, Reference Allen and Cairney2017; Clarke et al., Reference Clarke, Jennings, Moss and Stoker2018, pp. 104–105). They have little contextual understanding of the lives of ordinary citizens and are said to be “out of touch” (Wright, Reference Wright2013; Crace, Reference Crace2015; Lamprinakou et al., Reference Lamprinakou, Morucci, Campbell and van Heerde-Hudson2016, p. 208; Allen and Cairney, Reference Allen and Cairney2017; Allen and Cowley, Reference Allen, Cowley, Leston-Bandeira and Thompson2018; Clarke et al., Reference Clarke, Jennings, Moss and Stoker2018, p. 2).

Career politicians have also been criticized for their strong ambition and for focusing less on the common good (Jackson, Reference Jackson1988; O’Grady, Reference O’Grady2019, p. 545). They are Machiavellian and single-mindedly devoted to personal advancement (King, Reference King1981, pp. 279, 283–284; Riddell, Reference Riddell1996, p. 278; Oborne, Reference Oborne2007; Allen and Cairney, Reference Allen and Cairney2017, pp. 18–19; Allen, Reference Allen2018, pp. 36–37; Clarke et al., Reference Clarke, Jennings, Moss and Stoker2018, pp. 88–97). Publics in turn paint them as disingenuous, “not straight talkers,” “twisters,” and characters who generally “make promises they don’t keep” (Borchert, Reference Borchert, Borchert and Zeiss2003, pp. 8, 19; Wright, Reference Wright2013; Allen and Cairney, Reference Allen and Cairney2017, p. 20; Allen, Reference Allen2018, pp. 38–39; Clarke et al Reference Clarke, Jennings, Moss and Stoker2018, pp. 91–93).Footnote 2

Definitions

Many of the positive and negative claims made about “career politicians” have also been applied to “the political class” and “professional politicians” (see Allen and Cairney, Reference Allen and Cairney2017; pp. 21–22; Allen, Reference Allen2018, pp. 20–23; Allen and Cowley, Reference Allen, Cowley, Leston-Bandeira and Thompson2018). This is partly because some commentators and researchers use the terms interchangeably, and partly because there is no consensus on how to distinguish among them. The inconsistent use of concepts and measures in much academic research confounds the comparison of findings (Allen and Cairney, Reference Allen and Cairney2017). Hence, before we extract the concept’s principal dimensions and measure them, it is necessary to clarify who career politicians are.

Distinguishing career politicians from the political class is relatively straightforward. Allen and Cowley (Reference Allen, Cowley, Leston-Bandeira and Thompson2018, p. 222) use “political class” to refer to an unrepresentative group of elected politicians. Others define it more broadly to include MPs’ assistants, lobbyists, political consultants, and staff in political parties and policy institutes (Jun, Reference Jun, Borchert and Zeiss2003, p. 170), executive appointees and judges (Borchert, Reference Borchert, Borchert and Zeiss2003, pp. 5–6, 16), and even political journalists (Oborne, Reference Oborne2007). Whether drawn more widely or narrowly, the idea of a political class is nonetheless distinct from the idea of both career and professional politicians because it refers to an aggregation of disparate individuals who are likely to have different roles, drives, and motives.

The relationship between professional politicians and career politicians is less clear-cut. Allen and Cowley (Reference Allen, Cowley, Leston-Bandeira and Thompson2018) define “professional politicians” as those who enter legislatures from occupations in the political world. Both Borchert (Reference Borchert, Borchert and Zeiss2003) and Jun (Reference Jun, Borchert and Zeiss2003) classify professional politicians as a sub-set of the political class, as individuals who perform their roles full-time. Complete commitment to their roles also distinguishes them from their amateur and part-time predecessors. This is how they are characterized in traditional studies of professionalization and institutionalization (Polsby, Reference Polsby1968; King, Reference King1981, pp. 277–278; Matthews, Reference Matthews1984; Squire, Reference Squire1993; Best and Cotta, Reference Best, Cotta, Best and Cotta2000; Rush and Cromwell, Reference Rush, Cromwell, Best and Cotta2000, p. 490; Borchert and Zeiss, Reference Borchert and Zeiss2003; Cairney, Reference Cairney2007).

The next step requires some context. The term “professional politician” was used in studies of legislative professionalization long before the rise of “career politicians,” which most observers backdate to the 1970s. King (Reference King1981) substituted this new term for professional politician in an essay on the changing profile of British politicians. Just like the professional politician in institutionalization and professionalization studies, King’s (Reference King1981, pp. 250–251) career politician was committed to and aspired to be in politics full-time. But beginning with Riddell’s (Reference Riddell1996) influential book 15 years later, three important dimensions were added, two of which are often regarded as more important than commitment. Since Riddell, this more multifaceted conceptualization of “career politician” has become increasingly commonplace in academic and public discourse.

Since the key marker for professional politicians is that they are full-time, all professional politicians must be counted as at least partial career politicians because they share the career politician’s commitment attribute. To the extent that some professional politicians also satisfy one or more of the three newer definitional dimensions, they become stronger career politicians (career politician is a continuous variable) and are more likely to be so branded by researchers, commentators, and members of the public (Squire, Reference Squire2007). Many people use the terms interchangeably. While this may be imprecise, it is not entirely incorrect.

The career politician: four fundamental dimensions

Applying Goertz’s (Reference Goertz2006) principles of concept formation, we treat “career politician” as a multidimensional concept whose components must be justified by normative claims about their political importance and causal claims about their consequences. From our review of the literature and political discourse, four dimensions stand out: Strong Commitment, Narrow Occupational Background, Narrow Life Experience, and Strong Ambition.

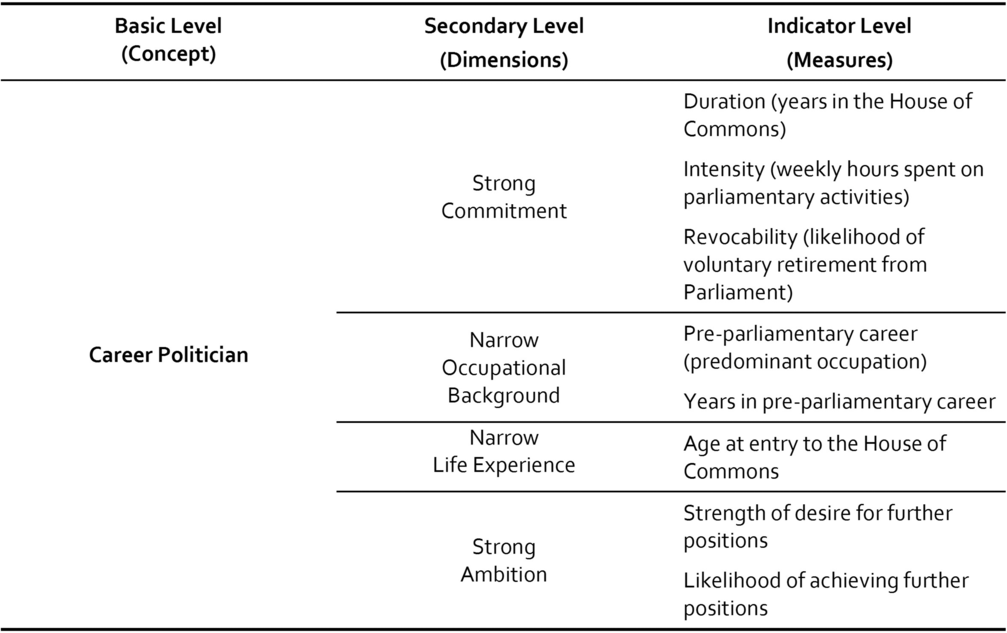

These dimensions can then be considered within a three-level framework (Goertz, Reference Goertz2006, pp. 6–7, 60). The “basic level,” the first column in Figure 1, is the concept itself – career politician – used for making theoretical and empirical claims about consequences. The “secondary level,” the second column, identifies the concept’s fundamental dimensions. The “indicator level,” the third column, lists each dimension’s operationalizations. The basic and secondary levels are sufficiently abstract to enable theory building in comparative analysis. The indicator level can accommodate cross-national differences in accessible data (Goertz, Reference Goertz2006, p. 64). Our data, as noted in the introduction, come from interviews with British MPs in the 1970s, supplemented with information on their pre-parliamentary occupations and subsequent careers, and re-interviews four decades later.

Figure 1. Career politician concept.

Commitment

During the re-interviews, we asked a former minister: “What does the phrase ‘career politician’ mean to you?” In his mind it was simple: “It means someone who thinks politics is their life.” When King (Reference King1981) coined the term that is exactly what he meant too.Footnote 3 Career politicians do not regard politics as a short-term interlude in varied careers (Jun, Reference Jun, Borchert and Zeiss2003, p. 174). Politics is their occupation and preoccupation, their vocation, as Weber saw it (King, Reference King1981, pp. 250–255; Riddell, Reference Riddell1996, p. 7; Oborne, Reference Oborne2007, p. 326). Career politicians are committed to politics as a full-time, lifetime occupation (Riddell, Reference Riddell1996, pp. 2–7). They work very hard and for very long hours. They rule out voluntary retirement to pursue other careers (King, Reference King1981, pp. 250–255).

In Table 1 below, we present measures for three aspects of commitment: duration, intensity, and revocability.

Table 1 The Strong Commitment dimension

Since nearly all the 1974 interviewees were either deceased, retired, or on the cusp of retirement by 2016, it is possible to use behavioral indicators across their entire careers to assess degrees of commitment. Duration is measured by the total number of years each MP served in the House of Commons. It distinguishes those for whom politics has actually been a lifetime occupation and serves as a proxy for vocational tenacity, a personal characteristic associated with commitment as a “calling.” Table 1 shows that there is a wide range of duration: 9% left in 10 or fewer years, and nearly 1 out of 4 did not stay beyond 15 years, not enough for a lifetime’s vocation, which might require 25 years or more – one could enter around age 40 and retire at 65 or later still, which 42% did.Footnote 4

Intensity of commitment is measured by total time spent on parliamentary activities inside and outside Westminster. This information was obtained on a form completed by the 1974 interviewees. Time spent inside the House of Commons (“during a typical week when the House is in session”) included specific estimates for time in standing and select committees, in the Chamber, on constituency work, party meetings, and other (lobby, dining room, etc.). Time spent outside the House was divided into constituency and party work, and other work, which for ministers included their long hours in Whitehall. The modal estimate for total time engaged with the career in a typical week was between 51 and 60 hours. Nine percent reported 40 hours or less, as in a 9–5 job, while nearly half put their estimate at 60 hours or more, which is what some academics who see their own careers as vocations might claim.

Revocability of commitment is measured by two questions in the 1974 interviews: “How likely is it that you might voluntarily retire from Parliament?” and “What would be the reasons for this?” This measure assesses their intentions at the time of the interviews and whether alternative careers were at least considered as possibilities.Footnote 5 Sixty-two percent of respondents were not planning voluntary retirements. We also coded a behavioral measure, which could be used where interview data are not available, of what these MPs actually did over the ensuing decades.Footnote 6 In the end, four out of five stayed the course. Although there is a good deal of measurement error in the behavioral indicator, it nevertheless has a significant correlation (at the 0.05 level) with MPs’ 1974 responses to the interview questions.

Occupational background

While King (Reference King1981) regarded Strong Commitment as the paramount defining attribute of a career politician, other political scientists and commentators have emphasized a general “lack of real-world experience” (Riddell, Reference Riddell1996). During recent decades, attention has increasingly focused on pre-parliamentary occupational backgrounds for which there is often readily available data.

Narrow Occupational Background relates to a particular part of experience in the wider world. What do politicians who have held “real jobs” learn through their occupational experiences about the everyday lives of ordinary citizens? In most cases, not much. But they do acquire sectoral policy expertise, and they may develop valuable management experience. Thus, former miners who go into politics will bring with them knowledge about the mining industry, while soldiers, farmers, and business people will bring with them knowledge about the armed forces, farming, and business, respectively.

Because they have not held such “real jobs,” career politicians are said to lack practical, common-sense, experiential knowledge about policy areas (Oborne, Reference Oborne2007; King and Crewe, Reference King and Crewe2014, p. 208; Kettle, Reference Kettle2015). They are poorly equipped, it is said, to evaluate legislation or, as ministers, to test the advice of civil servants (Groves, Reference Groves2012; Savoie, Reference Savoie2014; Allen, Reference Allen2018; Hardman, Reference Hardman2018, p. xiv). Furthermore, lack of significant managerial experience in commerce or industry impairs the career politician’s preparation for ministerial office. They just do not “know how to run things” (Cavendish, Reference Cavendish2010).

Pre-parliamentary career is our first indicator of Narrow Occupational Background. In 1974, MPs were asked to correct an occupational history form listing their pre-parliamentary occupations. We began with these corrected forms and worked with more recent published sources to ascertain their post-education careers.

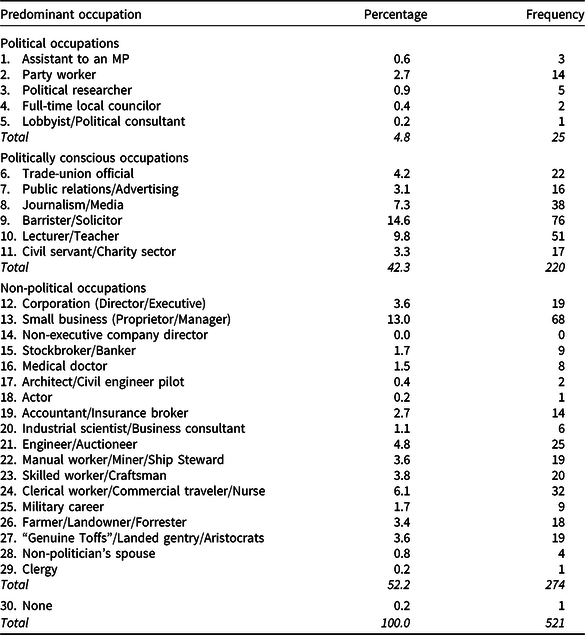

In Table 2, we list MPs’ predominant pre-parliamentary occupations and the number of MPs who pursued each. Following Cairney’s (Reference Cairney2007) widely used classifications, these occupations are divided into three groups: “Political” (Cairney’s “Instrumental”), “Politically conscious” (Cairney’s “Brokerage”), and “Non-political” (Cairney’s “Proper Jobs”).

Table 2. Narrow Occupational Background: pre-parliamentary career

“Political occupations” are those directly related to politics like assistant to an MP, a lobbyist, a party worker, or a researcher at party offices. “Politically conscious occupations” are not directly political but are close to politics and provide perspectives, training, and windows into political careers (Jun, Reference Jun, Borchert and Zeiss2003, p. 173). Many of their practitioners are in touch with political worlds or follow developments in them regularly. These include occupations like trade-union official, public relations, journalism, and barrister. Finally, “Non-political occupations” cover a wide variety of “real jobs” in sectors where most “ordinary people” work: corporations, small businesses, engineering, clerical work, construction, mining, or farming.

In 1974, politicians who had pursued only political occupations were 4.8% of the sample. Adding the intermediate politically-conscious category produces a total of 47%. Finally, MPs with Non-Political backgrounds are 52%.

Years in pre-parliamentary career is our second indicator of Narrow Occupational Background. For this measure, we simply aggregated the number of years that MPs in our sample had spent working in their predominant pre-parliamentary occupation. As Table 3 shows, just under 1-in-10 MPs had spent up to 5 years in their predominant career, while just over 1-in-3 had accumulated 16 years’ experience or more. The majority of MPs (just over 54%) had spent between 6 and 15 years in their predominant pre-parliamentary occupation.

Table 3. Narrow Occupational Background: years in pre-parliamentary career

These measures refine and strengthen the data on predominant occupations. The more years that MPs have spent in their predominant pre-parliamentary career, the more likely they are to bring into Parliament substantial experiential, common-sense knowledge of that policy sector, and, quite often, serious managerial experience.

General life experience

To many citizens, being a career politician is synonymous with being “out of touch.” Career politicians are allegedly unaware of the difficulties and challenges in citizens’ everyday lives because they lack familiarity with citizens’ significant social, economic, and personal life experiences (Wright, Reference Wright2013, pp. 451; Clarke et al., Reference Clarke, Jennings, Moss and Stoker2018, pp. 104–107, 204–207).

Many people expect to see in their politicians something like Aristotle’s (1925) “practical wisdom,” a leadership trait that enables political leaders to comprehend and pursue the well-being of ordinary people and the political community, a leadership trait learned through decades of life experiences. As a former British MP, Tony Wright (Reference Wright2013, p. 452) observed about career politicians:

They are certainly clever… but this does not make them wise. Nor does it compensate for a deficiency of experience of other walks and conditions of life that might inform their political judgments. When people say they think politicians are “out of touch”, these are the sort of considerations they have in mind.

Before the 1970s, many politicians did not enter parliament till middle age, having experienced decades of adult life in “the real world.” Contemporary career politicians, by contrast, enter earlier (Jun, Reference Jun, Borchert and Zeiss2003, p. 174). Since national politics is no longer part-time, significant life experiences beyond the “political bubble” must be absorbed before politicians enter parliament (King, Reference King2015, pp. 71–72).

Today’s career politicians have not done so, and yet expect to rise quickly to ministerial office (Allen, Reference Allen2013). Their growing numbers have created concerns that governments are being run by unseasoned young adults (Clarke et al., Reference Clarke, Jennings, Moss and Stoker2018, pp. 206–210).

For a proxy indicator of Narrow Life Experience, we use age at entry to the House of Commons, as in Table 4, which measures the opportunity for having shared or encountered significant life experiences in the wider world beyond politics.Footnote 7 Ten percent of respondents in the 1974 sample first entered the House when they were age 30 or younger. If we take age 35 as the marker for early entry, the numbers rise to 32%.

Table 4. Narrow Life Experience: age at entry to the House of Commons

Because the career-politician concept’s dimensions overlap in academic and public discourse, some overlap among indicators is unavoidable, and therefore some theoretically justified “double-counting” is required. For example, many politicians who enter in middle age with plenty of life experience, and having had “proper jobs,” are nevertheless regarded as career politicians because they are deeply committed to the career and have very strong ambition. Classic career politicians who enter parliament early with similarly strong ambitions and commitments should, in light of their lack of non-political occupational and general life experiences, score higher on any summary index.

Ambition

Characterizations of career politicians also emphasize their sometimes excessive ambition (King, Reference King2000; Rush, Reference Rush2001, pp. 135–137). Career politicians are said to stand out by the strength of their desire for power and fame (King, Reference King1981, p, 282; White, Reference White1983; Oborne, Reference Oborne2007, p. 33; Goplerud, Reference Goplerud2015; O’Grady, Reference O’Grady2019, p. 551; Riddell, Reference Riddell1996, p. 28; Allen and Cowley, Reference Allen, Cowley, Leston-Bandeira and Thompson2018). This single-minded motivation travels well cross-nationally because many career politicians share a vulnerability: if they lose office in middle age, they may have few other skills with which to pursue alternative careers offering comparable status or even income (McAllister, Reference McAllister and Norris1997, p. 20; Wessels, Reference Wessels and Norris1997, pp. 76–77; Roberts, Reference Roberts2017; c.f. Mattozzi and Merlo, Reference Mattozzi and Merlo2008).

Because career politicians are so driven by ambition, they concentrate on the game of politics (Wright, Reference Wright2013, p. 449; Sieberer and Müller, Reference Sieberer and Müller2017). They want to make a mark to advance their careers. They want laws enacted quickly, push for immediate results, take short-term perspectives, and neglect underlying problems (King and Crewe, Reference King and Crewe2014). Moreover, they have inadequate public-service orientations, for their strong ambitions lead them to “see politics as a career move rather than a call to public service” (Blears, Reference Blears2008).

Data on the desire for office are available from transcribed answers to two questions in the 1974 interviews (Table 5). The first question was: “And finally, your own plans? Are there any further positions in the House that you would like to seek sometime in the future? If ‘Yes,’ and position is left unspecified, then ‘What position might this be?’” The next question was: “What would you say are your chances of achieving (highest position mentioned)?”

Table 5. The Strong Ambition dimension

These were non-attribution interviews with written guarantees, conducted at a time when non-attribution was taken very seriously. Some respondents were reserved, but most seemed to answer frankly.Footnote 8

Strength of desire for further positions

In response to the first question, nearly all those desiring further positions, that is, those we judge to be career politicians to some extent, specified posts ranging from whips to cabinet ministers. On the basis of these discussions, strength of desire was coded from “Absolutely not” to “Very strong.” The last of these categories included respondents who said they would leave the Commons if a position was not forthcoming, a mindset associated with “ultra” career politicians. Those whose self-reported ambitions ran from “No” to “Weak” were further coded for the reasons behind their static ambition: involuntary (age, expects to lose seat, leader would never appoint me) and voluntary (other stronger commitments to family, business, or constituents). Both provided the basis for the summary code of strength of desire for further position presented in the table. Thirty-four percent expressed strong or very strong desires for further positions, with career politicians presumably among them.

Likelihood of achieving further position

For excessive ambition, responses to the second question are instructive: those who believe their chances of achieving further positions are very good or even fairly good (18%) will, according to Schlesinger’s (Reference Schlesinger1966) ambition theory, be more determined than those who want further positions but see their chances as uncertain, very small or negligible (33%) (see also Sieberer and Müller, Reference Sieberer and Müller2017). At the very least, responses to this second question help weed out those who are less serious about promotion.

From the political-science literature and political discourse about career politicians, we have extracted four fundamental dimensions: Strong Commitment, Narrow Occupational Background, Narrow Life Experience, and Strong Ambition, and eight indicators of these dimensions. Now we consider how to handle them.

Career politician: a family resemblance concept

The classic approach to defining concepts relies upon necessary and sufficient conditions (Goertz, Reference Goertz2006). Each of the concept’s dimensions must be necessary for the concept’s definition, all of them together being sufficient to define the concept. Not many social-science concept definitions fully meet these stringent criteria. But “career politician” is a worse fit than most. It has been stretched (Sartori, Reference Sartori1970) to cover an ever-wider variety of cases, while the spotlight has shifted from one definitional dimension to another.

The consequence of decades of thinking with exemplars and conceptual stretching is that none of the concept’s four dimensions is absolutely necessary to identify a career politician, which violates the key requirement for classic concept definitions. Each dimension has notable exceptions, that is, individuals who do not fit its criterion but who most observers would recognize as career politicians because they display one or more of the other dimensions.

Let us consider examples:

Dimension 1: Strong Commitment

Everyone recognizes early-entry, “ultra” career politicians as members of the conceptual family (Kam, Reference Kam2006; Goplerud, Reference Goplerud2015; Henn, Reference Henn2018; Heuwieser, Reference Heuwieser2018; O’Grady, Reference O’Grady2019), but it is not clear they have long-term commitments to their parliamentary careers (Dimension 1). If they do not rise quickly or, having risen, doubt their opportunities for further preferment, they may leave politics to pursue careers in other fields (Mattozzi and Merlo, Reference Mattozzi and Merlo2008). Prominent examples in British politics include David Cameron, George Osborne, Nick Clegg, and David Miliband: “Here today, gone tomorrow politicians,” as a 2016 re-interviewee put it. Nevertheless, they were recognized as career politicians because they lacked occupational and life experiences and displayed very strong ambitions for office.

Dimensions 2 and 3: Narrow Occupational Background and Narrow Life Experience

There are plenty of examples in Britain of MPs – figures like Cecil Parkinson, Norman Tebbitt, Vince Cable, and Chris Huhne – who are recognized as career politicians but who entered Parliament after age 40 and had significant occupational and general life experiences outside politics. Despite not satisfying Dimensions 2 and 3, they are seen as career politicians because they fit the profiles for commitment and strong ambition.

Dimension 4: Strong Ambition

Many professional politicians lack strong ambitions for ministerial office (Dimension 4) and yet are counted as career politicians because they work as full-time “constituency members” and “policy advocates” (Searing, Reference Searing1994) and are in politics for the long haul. The Labour MPs Dennis Skinner and Tam Dalyell were career politicians because of robust commitments to their parliamentary careers. A limited number also enter early without much experience in the wider world (Dimensions 2 and 3).

In sum, “career politician” does not fit the requirements of classic concepts: none of its four fundamental dimensions seems absolutely necessary to the categorization. How then can we measure the concept and identify career politicians systematically?

Actually, there is “more or less consensus” on recognizing career politicians when we see them, but it is difficult to understand where this “more or less consensus” comes from. We suggest it comes from intuitive applications of Wittgenstein’s (Reference Wittgenstein1953) “family resemblance” structure to the concept.

The key difference between classic and family-resemblance concepts is substitutability: necessary conditions do not have substitutes in classic concepts, but the absence of some conditions can be compensated for by the presence of others in family-resemblance concepts (Goertz, Reference Goertz2006, p. 45). All that is required is reaching the point of sufficient resemblance to recognize a case as part of the conceptual family.

There may be no attribute that all members of the category share. Instead, one can focus on single attributes or on different combinations of attributes, as we intuitively do when recognizing members of families by different combinations of key features like hair color, body type, facial structure, gait, or skin tone (Collier and Mahon, Reference Collier and Mahon1993). For example, we may recognize person A as a member of family Q by her possession of three characteristics out of four: 1, 2, and 3, but not 4. But we may also recognize person B as a member of this same family Q by her possession of any two, or even one, of characteristics 1, 2, 3, and 4. In other words, neither characteristic 1, 2, 3 nor 4 is absolutely necessary to establish membership of family Q, because different sub-sets of these characteristics may be sufficient (Goertz, Reference Goertz2006).

The strength of the family-resemblance structure is that secondary conceptual levels (see Figure 1) can, with some substitutability, enable theory building in comparative analysis, while further substitutability at the indicator level can accommodate cross-national differences in available data (Goertz, Reference Goertz2006, p. 64). This structure also keeps the career politician concept close to its usage in political discourse, which protects its political significance and facilitates explanation.

Re-constructing the concept from the dimensions

The key to using the career-politician dimensions is that (a) most political scientists and commentators would likely consider all four relevant, even if they themselves focus on only one or two, and (b) even though many treat the classification as a binary choice, we are in fact dealing with a continuous variable. Any one dimension may be sufficient to recognize whether or not person A is a member of career-politician conceptual family Q. But to measure how much of a career politician person A is, it is desirable to utilize as many dimensions as possible.

We have therefore integrated all four dimensions into a single index, which is summarized in online Appendix Table 1. By using more information than most political scientists and commentators, we integrate their collective understandings and improve the validity of our measures

One problem with creating aggregate-level indices is that not all components are measured on the same scale. In our case, the challenge consists of adding together continuous (e.g., age of entry to parliament), ordinal (e.g., strength of ambition for office), and categorical (e.g., type of pre-parliamentary occupation) variables.

To construct a composite index using the career-politician dimensions, we begin by standardizing and adding together each constituent measure for each dimension. For the Strong Commitment dimension, for example, we apply this procedure to the duration, intensity, and revocability indicators. We again standardize the composite measure to create our final index for this dimension. This step ensures that the overall index remains centered at zero, measuring the number of standard deviations that each politician deviates from that mean. We thereby obtain the following standardized score for each MP’s commitment:

$$x{\big[i\big]_{commitment}} = Standardize\;( {\frac{{{x{{\big[ i \big]}_{years}} - {{\overline x}_{years}}}}\over{{{\sigma _{years}}}}} + \frac{{{x{{\big[ i \big]}_{hours}} - {{\overline x}_{hours}}}}\over{{{\sigma _{hours}}}}} + \frac{{{x{{\big[ i \big]}_{retire}} - {{\overline x}_{retire}}}}\over{{{\sigma _{retire}}}}}\;} )$$

$$x{\big[i\big]_{commitment}} = Standardize\;( {\frac{{{x{{\big[ i \big]}_{years}} - {{\overline x}_{years}}}}\over{{{\sigma _{years}}}}} + \frac{{{x{{\big[ i \big]}_{hours}} - {{\overline x}_{hours}}}}\over{{{\sigma _{hours}}}}} + \frac{{{x{{\big[ i \big]}_{retire}} - {{\overline x}_{retire}}}}\over{{{\sigma _{retire}}}}}\;} )$$We apply the same strategy to the Narrow Occupational Background, Narrow Life Experience, and Strong Ambition dimensions.

Composite career-politician index

We used the same basic approach to build our overall composite career politician index, which is the standardized sum of our four different dimensional indices. The standardized overall composite index is thus defined as:

$$x{\big[i\big]_{career\;politician}} = Standardize\;( {x\big[ {i{\big]_{commitment}} + x} \big[i{\big]_{occupation}} + x\big[ {i{\big]_{experience}} + x} \big[i{\big]_{ambition}}} )$$

$$x{\big[i\big]_{career\;politician}} = Standardize\;( {x\big[ {i{\big]_{commitment}} + x} \big[i{\big]_{occupation}} + x\big[ {i{\big]_{experience}} + x} \big[i{\big]_{ambition}}} )$$Note that this approach gives each of the four dimensions an equal impact on our final composite index scores. Some might argue that equal weights are an inappropriate modeling choice, because recent studies have tended to place a greater emphasis on career politicians’ occupational backgrounds and life experiences over their commitment and ambition (Henn, Reference Henn2018; Heuwieser, Reference Heuwieser2018; O’Grady, Reference O’Grady2019). It is difficult, however, to determine exactly how to weight the dimensions. As an exploratory robustness check, we made qualitative judgments to weight them in a parallel measure that can be found in the online Appendix. As a further robustness check, we extracted the first principal component (1st PC) from our eight indicator-level measures and used its dimension weights as an alternative to our unweighted composite career-politician index. In validations matching those reported below and reported in the online Appendix, both robustness checks produced strikingly similar results to those with our “agnostic” unweighted composite career-politician index.

Validity tests

Recent quantitative investigations use occupational background and age at entry as indicators of “career politician” (Kam, Reference Kam2006; Goplerud, Reference Goplerud2015; Henn, Reference Henn2018; Heuwieser, Reference Heuwieser2018; O’Grady, Reference O’Grady2019) despite some uncertainty about their validity (Heuwieser, Reference Heuwieser2018, pp. 316; 320–321). We report validity tests for these two indicator dimensions and for the other two we use to measure the concept.

As a first validity test of each dimension, we compare the standardized scores for MPs who served as ministers and those who remained on the backbenches. If the indicators work as expected, scores for ministers should be consistently higher, as it is well-established that ministers are more likely to be career politicians than are backbenchers (Koop and Bittner, Reference Koop and Bittner2011; Cowley, Reference Cowley2012; Allen, Reference Allen2013; Goplerud, Reference Goplerud2015; Allen and Cairney, Reference Allen and Cairney2017, p. 23). In practice, this test is even more demanding than it first appears. Those counted as ministers embrace everyone in our sample who held ministerial office, including junior ministers who had little prospect for further advancement (Searing, Reference Searing1994), and indifferent career politicians who served in pre-1970 governments (King, Reference King2015, pp. 62–63).

The results summarized in Table 6 are impressive. In each paired comparison, ministers show a higher standardized mean score than backbenchers on our composite career-politician index and on our 1st PC weighted scores measure, as well as for each separate dimension. In each case, the difference is significant at the 0.05 level based on our obtained t-statistics. The large gap between ministers’ and backbenchers’ Ambition standardized mean scores is striking but perhaps not surprising: MPs who became ministers are more likely to have desired high office than those who remained on the backbenches. The differences for the Commitment, Occupation, and Experience indices are somewhat smaller but still significant and in line with expectations.

Table 6. Validity Test 1: T-tests of standardized composite index, component indices, and 1st PC weighted scores for ministers and backbenchers

To assess the magnitude of our obtained differences, recall that the composite and four component indices are measured in terms of standard deviations from a zero-centered mean. For normally distributed data, about 34% of observations fall within one standard deviation above the mean. This fact allows us to assign percentile values capturing the share of observations that fall above (and below) our obtained standardized mean scores for both ministers and backbenchers.

Focusing on the composite career-politician index, we fail to reject the null-hypothesis (p > 0.1) in a conventional Shapiro–Wilk test, indicating that this index could have been drawn from an approximately normal distribution. We take this, and the approximately normal shapes of the density and QQ-plots of our index (shown in the online Appendix), as evidence that we can apply the above rule to our indicators.

Substantively, we are thus able to recover approximate percentiles for the mean scores of backbenchers and ministers, respectively. Based on their standardized mean in the second column of Table 6, backbenchers (−0.145) score an average value at the 44th percentile of all MPs. This means that the average career-politician score for backbenchers lies above 44% and below 56% among all MPs. This is to be expected because backbenchers should be a fairly random mix of career and non-career politicians. More importantly, the mean score for ministers (0.74) lies at the 77th percentile value on the career-politician index. This means that the average minister in our sample has a higher career-politician score than 77% of all MPs – strong substantive evidence that the composite index accurately measures the career-politician concept.

Our second validity test focuses on career politicians identified by King (Reference King1981; Reference King2015) and Riddell (Reference Riddell1996; Reference Riddell2011), the most knowledgeable academic and journalistic contributors to the subject. Again, this is a demanding test because King’s primary focus on commitment meant that he might have excluded those who received low scores on this dimension but high scores on the other dimensions. Moreover, there are certainly some career politicians in the 1974 sample who were not named by King or Riddell and who are therefore included among our “non-listed politicians,” that is, non-career politicians.

Table 7 reports standardized mean scores for the career politicians identified by King and Riddell and those who were not identified by either author.Footnote 9 All the differences in means are again significant at the 0.05 level based on our obtained t-statistics. Like the results in Table 6, the differences suggest our various component and composite indices capture well the degree to which an MP is a career politician. The dimensions that are most widely used by other researchers, Occupational Background and Life Experience, perform well, while even the weakest performing dimension, Commitment, still produces significant differences. Crucially, this dimension adds valuable information to our composite career-politician index, which again outperforms each individual dimension. The composite and 1st PC indices again produce the largest differences in means between both groups. Moreover, both these measures produce an impressive mean score for named career politicians at the 82nd percentile of the entire sample. The composite index, in other words, captures more than the sum of its component parts.

Table 7. Validity Test 2: T-tests of standardized composite index, component indices, and 1st PC weighted scores for career politicians listed by either King or Riddell

Conclusion

Career politicians are recognized by distinctive attributes for which they are both appreciated and criticized in academic and political discourse. From these sources, we extracted four fundamental dimensions of the career-politician concept: Strong Commitment, Narrow Occupational Background, Narrow Life Experience, and Strong Ambition.

We clarified the concept’s structure and measured its dimensions in order to strengthen the foundation for testing theories and hypotheses associated with it. We treated “career politician” as a multi-level, multidimensional concept that fits Wittgenstein’s family-resemblance structure. This structure helps explain why many observers and researchers can confidently identify career politicians using only one dimension. Yet, when they do so, they may capture sub-types that diverge somewhat from others. For example, professional politicians are career politicians, but they may be only partial career politicians because, although they have full-time commitments to their careers (one of the concept’s four dimensions), they may not share the other three dimensions. To the extent that they do, they are more complete career politicians; to the extent that they do not, they constitute a sub-type.

With interview data, supplemented with information on pre-parliamentary occupations and parliamentary career patterns, we measured each of the concept’s four dimensions with indicators that passed several validity tests: distinguishing between ministers and backbenchers, and between career politicians (named by two expert observers) and the other MPs in the sample. Our composite indices performed best, but each of the four dimensions also produced predicted mean scores. Occupational Background and Life Experience had more impact than Commitment, the oldest and more traditionally accentuated marker. Ambition provided quite strong results, but in the King–Riddell validation, it too was outdone by Life Experience. Compared to Occupational Background, Life Experience was considerably stronger in both validations. Thus, the results demonstrate the importance of the two variables, Occupational Background and Life Experience, that are most often used in empirical studies.

The clarified basic concept and its four dimensions are sufficiently abstract to enable theory building in comparative analysis, while the indicator level can accommodate differences in available data. For cross-national research, we have identified behavioral measures that do not require difficult-to-collect interview data: duration and revocability (see n. 6) for Commitment; types and length of pre-parliamentary careers for Occupational Background; and age at entry for Life Experience. Meanwhile, behavioral measures of Ambition can be imputed using Schlesinger’s (Reference Schlesinger1966) theory of ambition and opportunity structures.

Two broader points arise from our clarification and operationalization of the career-politician concept. The first relates to our use of the family-resemblance structure. There are other ambiguous multidimensional concepts prominent in everyday political discourse that help political actors navigate political developments, and help political scientists explain them, but which, like “career politician,” are difficult to define and measure with classic principles of concept formation. Wittgenstein’s family-resemblance approach can potentially unlock some of them and facilitate their investigation.

The second point relates to the substantive focus of the paper. Political scientists still have a great deal to do in terms of examining the impact of career politicians on policy and national political life. It is important to examine more fully not just the behavior of career politicians but also what it is about career politicians – their commitment, experiences and ambition – that affects policy and politics. It is doubly important to investigate the topic in an era of national populism, when it has become fashionable in most western democracies to regard career politicians as “pariah politicians” (Borchert, Reference Borchert, Borchert and Zeiss2003, pp. 8, 19). Better empirical knowledge can help us evaluate the claims made for and against them and whether active measures might be needed to reduce their numbers.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the University of Chicago Center for Cognitive and Neuroscience and by the Arete, Templeton, and Leverhulme Foundations. Earlier versions of the article were presented at the EPSA Annual General Conference in Milan in June 2017, the General Conference of the ECPR Standing Group on Parliaments in Basel in June 2017, the MPSA Annual Conference in Chicago in April 2018, and the PSA Parliaments Group Annual Conference in November 2018. We are grateful to all those who provided feedback. We would also like to thank the four anonymous reviewers for their helpful and constructive comments.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1755773920000077.