Introduction

When do organizations constitutive for civil society (CSOs)Footnote 1 such as interest groups, political parties, or service-oriented organizations consider their existence under threat? As demonstrated by important specialist literatures, these three types of organizations’ distinct political and social functions have fundamental implications for their behavior in the arenas they operate in. That said, Lowery (Reference Lowery2007) has prominently argued that the ability to assure survival is the most fundamental precondition for interest groups to pursue any other goal (see also, for instance, Beyers et al., Reference Beyers, Eising and Maloney2008; Halpin, Reference Halpin2014; Dür and Mateo, Reference Dür and Mateo2016; Hanegraaff and Poletti, Reference Hanegraaff and Poletti2019), an underlying driver of organizational behavior equally stressed in research on service-oriented organizations and political parties (e.g., Panebianco, Reference Panebianco1988; Walker and McCarthy, Reference Walker and McCarthy2010; Rimmer, Reference Rimmer2018). Building on such parallels, a growing body of research has started to study groups and parties fruitfully alongside each other, showing how they are confronted with similar challenges and choices (e.g., Hasenfeld and Gidron, Reference Hasenfeld and Gidron2005; Saurugger, Reference Saurugger2008; Allern and Bale, Reference Allern and Bale2011; Biezen et al., Reference Biezen, Mair and Poguntke2012; Fraussen and Halpin, Reference Fraussen and Halpin2018; Farrer, Reference Farrer2018). This paper argues that the exposure of organizational leadersFootnote 2 to survival pressure – or mortality anxiety – can be suitably theorized and accounted for by such an encompassing approach.

The characteristic central to the approach proposed in this paper is that many interest groups, service-oriented organizations, and parties fall in the class of ‘membership-based voluntary organization’. This class of organization is confronted with two fundamental challenges in contemporary democracies frequently highlighted in interest group, party, and nonprofit research alike: first, being constituted by voluntary members, organizations need to make continuous efforts to maintain their support base (e.g., Wilson, Reference Wilson1973; Barasko and Schaffner, Reference Barasko and Schaffner2008; Gauja, Reference Gauja2015). Second, when operating in individualizing societies, organizational maintenance becomes increasingly difficult and interest representation complex as collective identities and group affiliations weaken (e.g., Dekker and van den Broek, Reference Dekker and van den Broek1998; Biezen et al., Reference Biezen, Mair and Poguntke2012; van Deth and Maloney, Reference van Deth and Maloney2012). While the former challenge reinforces pressures of organizational self-maintenance, the latter enhances functional pressures of goal attainment (Weisbrod, Reference Weisbrod1997: 545; Beyers et al., Reference Beyers, Eising and Maloney2008: 1115; Halpin, Reference Halpin2014: 24, 62–63). CSO leaders need to reconcile these two fundamental pressures, a balancing act based on which distinct categories of factors expected to shape mortality anxiety can be specified and hypotheses can be formulated.

Studying mortality anxiety – as compared to actual disbandment – is important as it grants a fine-grained understanding of the drivers of organizational stress (Heylen et al., Reference Heylen, Fraussen and Beyers2018), which is crucial for the adaptive capacity of organizations – their ability to counter vulnerabilities causing anxiety – and (to the extent such ability is limited) the evolution of group populations (Halpin and Thomas, Reference Halpin and Thomas2012: 217). This aligns with a growing literature stressing the centrality of the ‘survival imperative’ to understand better what groups do, when they do it, and how they do it (for an overview, see Halpin and Fraussen, Reference Halpin and Fraussen2015). More specifically, Halpin and Thomas (Reference Halpin and Thomas2012: 216–217) have stressed that given the prominence of ecological theory in group research, it is important to determine whether mortality anxiety is predominantly driven by intraorganizational factors (such as related to an organization’s membership) or by external challenges (such as competitive pressure) (see also Gray and Lowery, Reference Gray and Lowery1997; Heylen et al., Reference Heylen, Fraussen and Beyers2018). Similar questions have been raised in research on party performance and change contrasting the influence of intraorganizational properties with party system dynamics as central drivers of party behavior and survival (e.g., de Lange and Art, Reference de Lange and Art2011; Schumacher et al., Reference Schumacher, de Vries and Vis2013; Bolleyer et al., Reference Bolleyer, Correa and Katz2018). Furthermore, the only cross-national study of mortality anxiety we are aware of has shown that mortality anxiety shapes the influence strategies of groups (Hanegraaff and Poletti, Reference Hanegraaff and Poletti2019), hence affects how the latter engage in politics. On a fundamental level, this points to mortality anxiety as a central mechanism whose drivers not only grant insights into a factor that contributes to how CSOs try to assure democratic voice. They also – in the reverse – grant insights into the roots of a fundamental ‘representation bias’ in organized civil society reinforcing societal inequalities, which does not relate to organizational mobilization but affects existing organizations’ survival prospects on the one hand and their influence strategies on the other (Schattschneider, Reference Schattschneider1960; Halpin and Thomas, Reference Halpin and Thomas2012; Fisker, Reference Fisker2015; Hanegraaff and Poletti, Reference Hanegraaff and Poletti2019). Finally, the fact that drivers of mortality anxiety to date have only been studied within single country settings, notably Belgium, Scotland, and the USA (Gray and Lowery, Reference Gray and Lowery1997; Halpin and Thomas, Reference Halpin and Thomas2012; Heylen et al., Reference Heylen, Fraussen and Beyers2018), stresses the importance of cross-national research to put existing knowledge on a broader footing.

We test our hypotheses on organizational mortality anxiety with new data from four recent surveys of regionally and nationally active parties and groups in Germany, Norway, Switzerland, and the UK. Applying ordered logistic regression analysis to data covering different types of membership organizations across four countries, our findings put earlier insights into organizational mortality anxiety on a broader footing. More importantly, some prominent claims (e.g., about the centrality of organizational finances) are challenged, and earlier contradictory findings (e.g., on the relevance of organizational age) are clarified. Finally, by considering new aspects (e.g., the challenge to mobilize diverse constituencies) or more nuanced measures for central variables (e.g., distinguishing administrative and policy-oriented staff), our findings help to broaden our understanding of which civil society organizations tend to experience stress.

In the following, we present our theoretical framework. Having justified our case selection, described the data and variables, we present our findings. We conclude with a summary and a discussion of the broader implications of this study.

Mortality anxiety of membership-based voluntary organizations: a theoretical framework

The following hypotheses on the drivers of mortality anxiety experienced by membership-based CSOs are specified and systematized based on a synthesis of three sets of literature: classical works on political organization generally (e.g., Clark and Wilson, Reference Clark and Wilson1961; Wilson, Reference Wilson1973; Moe, Reference Moe1988), central works on mortality anxiety of interest groups (e.g., Gray and Lowery, Reference Gray and Lowery1997; Halpin and Thomas, Reference Halpin and Thomas2012; Heylen et al., Reference Heylen, Fraussen and Beyers2018; Hanegraaff and Poletti, Reference Hanegraaff and Poletti2019), and influential works on organizational maintenance and survival within the respective specialist literatures on groups and parties (e.g., Panebianco, Reference Panebianco1988; Katz and Mair, Reference Katz and Mair1995; Scarrow, Reference Scarrow1996; Weisbrod, Reference Weisbrod1997; Schmitter and Streeck, Reference Schmitter and Streeck1999; Jordan and Maloney, Reference Jordan and Maloney2007; Fraussen, Reference Fraussen2014; Halpin, Reference Halpin2014).

These literatures suggest that membership-based voluntary organizations that operate in advanced democracies are, irrespective of their political or social functions, confronted with two intertwined challenges – one intraorganizational, one external: the dependence on voluntary support and the volatility of such support in increasingly individualized societies. Each of these two challenges can be analytically associated with a distinct type of pressure from which factors expected to shape CSOs’ mortality anxiety can be derived.

Pressures of self-maintenance vs. goal attainment and how they shape mortality anxiety

CSOs’ ongoing dependence on voluntary support enhances pressures of self-maintenance, which focuses attention on an organization’s ability to keep its basic day-to-day activities going. Not only financial resources but also organization-level characteristics conducive to organizational resilience help countering these pressures, thereby likely to shape mortality anxiety. Meanwhile, when operating in individualizing societies in which collective support is difficult to generate and sustain, functional pressures of goal attainment intensify, focusing attention on the difficulties CSOs face when trying to respond to demands and represent the interests of members and constituencies in increasingly diverse and volatile societal settings. Exposure to pressures of goal attainment are likely to vary with CSOs’ capacity to pursue the interests of their constituencies and the relative difficulties in aggregating, representing, and responding to diverse (social or political) constituency demands, in turn, likely to shape mortality anxiety.

Factors facilitating goal attainment do not necessarily assure self-maintenance as many CSOs’ core goals are directed toward producing collective goods (e.g., policy change, placing an issue on the public agenda, or providing services to broader societal constituencies), which by definition non-members can also profit from (Olson, Reference Olson1965). This can create tensions for groups and parties when trying to respond to both types of pressures simultaneously (e.g., Beyers et al., Reference Beyers, Eising and Maloney2008; Klüver, Reference Klüver2011; Polk and Koelln, Reference Polk and Koelln2017), rationalizing the distinction between the two categories of drivers of mortality anxiety.

As visualized in Table 1, factors shaping organizations’ ability to respond to pressures of self-maintenance and goal attainment can be further grouped into intraorganizational factors and those external to the organization. We specify the expected consequences of the factors associated with each of the four categories in the following.

Table 1. Core dimensions shaping pressures experienced by civil society organizations

Hypotheses on pressures of self-maintenance and their implications for mortality anxiety

Starting with external resource dependencies, organizations’ growing reliance on private funding, especially donations, on the one hand, and on state resources, on the other, has been problematized in the literatures on parties, service-oriented organizations, and interest groups (e.g., Bosso, Reference Bosso, Cigler and B.A.1995; Katz and Mair, Reference Katz and Mair1995; Gray and Lowery, Reference Gray and Lowery1997; Weisbrod, Reference Weisbrod1997; Billis, Reference Billis2010; Bloodgood and Tremblay-Boire, Reference Bloodgood and Tremblay-Boire2017). Building on Wilson (Reference Wilson1973), Gray and Lowery (Reference Gray and Lowery1997: 28–29) considered external sources of finance – whether private or public – generally as an indication of weak organizational autonomy fueling mortality anxiety (Heylen et al., Reference Heylen, Fraussen and Beyers2018). Similarly, Panebianco (Reference Panebianco1988) stressed the fundamental tension between a party’s institutionalization (closely linked with an organization’s self-sufficiency) and its dependence on outside resources, be those resources provided by societal actors or the state. This rationale underpins the following hypotheses:

H1.1 (State Funding Hypothesis): Organizations which strongly rely on state funding are more likely to experience mortality anxiety than those which do not.

H1.2 (Private Donations Hypothesis): Organizations which strongly rely on private donations are more likely to experience mortality anxiety than those which do not.

Moving to factors contributing to intraorganizational resilience, a range of works in party and group research has stressed the importance of organizational self-sufficiency, making an organization more resilient (e.g., Panebianco, Reference Panebianco1988; Weisbrod, Reference Weisbrod1997). Four factors contributing to such resilience should make a voluntary organization feel less vulnerable, two linked to its evolution, namely the organization’s maturity and stability, and two linked to the nature of its membership base, namely members’ loyalty and involvement.

Starting with an organization’s evolution, Gray and Lowery (Reference Gray and Lowery1997: 30) have argued that young organizations might not be realistic about the survival threats confronting them, suggesting lower anxiety levels in younger age. Others, in contrast, have argued that increasing age points to a growing organizational maturity and ability to survive internal and external shocks, and related to this, increasing institutionalization. This underpins expectations of a ‘liability of newness’ (Panebianco, Reference Panebianco1988; Carroll and Hannan, Reference Carroll and Hannan2000; Anderson et al., Reference Anderson, Gray and Lowery2004: 142), hence, lower mortality anxiety with growing age. Similarly, the party literature tends to associate growing age with growing organizational consolidation, thereby suggesting lower risk of death in later periods of parties’ life cycles (Bolleyer, Reference Bolleyer2013). Meanwhile, institutionalized organizations tend to stick with established orientations and strategies, thereby assuring continuity for those operating within them (Panebianco, Reference Panebianco1988). High reliability and stability of structures is, according to ecological theory, associated with competitive advantages, hence, a lower mortality risk (Singh et al., Reference Singh, House and Tucker1986: 588). Organizational changes, in contrast, constitute responses to internal or external problems which have made existing structures unsuitable. This is the case because the introduction of a new orientation, new processes, or new strategies can unsettle an organization (Halpin, Reference Halpin2014). They might be unpopular with some members and face internal resistance or, alternatively, might generate unintended side effects (Panebianco, Reference Panebianco1988: 242; Gauja, Reference Gauja2015: 14). Taking these elements together, organizational stability should decrease mortality anxiety, while organizational changes should increase it. We thus arrive at two hypotheses linking indications of organizational resilience with mortality anxiety:

H2.1 (Organizational Maturity Hypothesis): The older an organization is, the less likely it experiences mortality anxiety.

H2.2 (Organizational Stability Hypothesis): Organizations able to rely on established strategies and structures are less likely to experience mortality anxiety than organizations experiencing change.

Members are constitutive for voluntary organizations, which by definition are under constant pressure to sustain member support to assure their maintenance (Wilson, Reference Wilson1973; Scarrow, Reference Scarrow1996; Jordan and Maloney, Reference Jordan and Maloney1997). Hence, the ability to rely on the latter – especially in individualizing contexts where building stable affiliations is challenging – should enhance organizational resilience and, consequently, reduce mortality anxiety (Gray and Lowery, Reference Gray and Lowery1997: 29). The extent to which members are loyal (i.e., the organization does not suffer membership decline) (Halpin and Thomas, Reference Halpin and Thomas2012: 221; Koelln, Reference Koelln2015) and can be actively involved in organizational activities and work (Halpin, Reference Halpin2006; Jordan and Maloney, Reference Jordan and Maloney2007) should enhance organizational capacity and thereby reduce the mortality anxiety an organization experiences. This leads to the following hypotheses:

H2.3 (Member Loyalty Hypothesis): Organizations with a stable membership base are less likely to experience mortality anxiety than organizations with a shrinking membership base.

H2.4 (Membership Involvement Hypothesis): Organizations able to cultivate an involved membership base are less likely to experience mortality anxiety than organizations with a passive membership base.

Hypotheses on pressures of goal attainment and their implications for mortality anxiety

When theorizing how pressures of goal attainment shape mortality anxiety we again distinguish between external and intraorganizational factors, respectively expected to affect the ability of organizations to be responsive to their members’ or constituencies’ interests, which can involve channeling interests into the political process or public awareness-raising or by meeting other substantive demands (e.g., for certain services) or a combination thereof.

Considering exposure to external pressures, organizations operating in individualizing societies are expected to be confronted with fundamental representation challenges, making goal attainment difficult, thereby enhancing mortality anxiety. One of these challenges relates to the saliency of the organization’s core issues, which is important to groups and parties alike, specifically declining issue salience due to changes in public opinion (e.g., Dalton et al., Reference Dalton, Farrell and McAllister2011; Binderkrantz et al., Reference Binderkrantz, Christiansen and Pedersen2015; Klüver, Reference Klüver2018; Hanegraaff and Poletti, Reference Hanegraaff and Poletti2019). Organizations can also face aggregation challenges when interest representation becomes more complex, resulting from societal individualization (i.e., growing diversity of constituencies’ interests) making organizations’ constituencies more heterogeneous and more difficult to represent coherently when moving from their broader interests to setting concrete priorities, which can be expected to affect partisan, political, and social membership organizations alike (e.g., Ryden, Reference Ryden1996: 25–26; Halpin and Fraussen, Reference Halpin and Fraussen2019: 1342–1343; Biezen et al., Reference Biezen, Mair and Poguntke2012). We can formulate the following hypotheses:

H3.1 (Salience Challenge Hypothesis) The more difficult it is for organizations to assure the salience of core issues, the more likely they experience mortality anxiety.

H3.2 (Aggregation Challenge Hypothesis) The more difficult it is for organizations to represent their constituencies, the more likely they experience mortality anxiety.

We conclude with an intraorganizational aspect expected to be particularly relevant to organizations’ capacity to respond to members’ or constituencies’ interests and demands (whether these are concerned with political or service-oriented activities): the hiring of specialist staff dedicated to policy-oriented (as opposed to administrative) tasks. Reliance on such staff reflects the prioritization of substantive activities (i.e., goal attainment),Footnote 3 rather than basic administrative functions. Paid staff can be generally expected to be more efficient than volunteer staff, while strongly caring about the long-term viability of their organization to protect their jobs (Fisker, Reference Fisker2015; Karlsen and Saglie, Reference Karlsen and Saglie2017). Policy-orientated staff, more specifically, should be particularly able to effectively mobilize an organization’s membership to support policy- and politically orientated activities (Billis, Reference Billis2010). Meanwhile, if organizations can afford to hire numerous specialist staff with a policy-oriented or political function, this suggests a high organizational capacity and functional differentiation that has been associated with lower mortality anxiety (Heylen et al., Reference Heylen, Fraussen and Beyers2018).

H4.1 (Policy-Oriented Staff Hypothesis): The more policy-oriented paid staff an organization is supported by, the less likely it is to experience mortality anxiety.

Table 2 summarizes our hypotheses along the analytical categories.

Table 2. Drivers of the mortality anxiety of civil society organizations

(+) factor expected to increase mortality anxiety; (−) factor expected to decrease mortality anxiety

Methodology and data

Country selection and data

To test our framework, we conducted (between April and October 2016) four surveys, each covering political parties, interest groups, and service-oriented organizations in Germany, Norway, Switzerland, and the UK. These four democracies are most different regarding important macro characteristics considered relevant for the structure and resources of membership organizations and, with this, their activities. Importantly, we cover central types of third sector regimes relevant in long-lived Western democracies (Salamon and Anheier, Reference Salamon and Anheier1998) with the UK being a liberal regime, Germany a corporatist one, Norway a social democratic one, and Switzerland considered a mix between the liberal and the social democratic regime (Einolf, Reference Einolf, Wiecking and Handy2015: 514; Butschi and Cattacin, Reference Butschi and Cattacin1993: 367). Public resources made available to voluntary sector organizations are particularly extensive in corporatist regimes (often associated with organizational ‘co-optation’), while competition for policy access is considered particularly intense in liberal systems. Furthermore, the four cases are located on opposite ends on a spectrum of generous vs. limited state funding for political parties (Germany and Norway on the generous and Switzerland and the UK on the limited end) (Poguntke et al., Reference Poguntke, Scarrow, Webb, Allern, Aylott, van Biezen and Verge2016). Finally, we varied country size, the type of multilevel structure, and the level of societal heterogeneity as factors identified as relevant for patterns of organizational formation, behavior, and survival (e.g., Hug, Reference Hug2001; Coates et al., Reference Coates, Heckelman and Wilson2007; Dür and Mateo, Reference Dür and Mateo2016; Bolleyer et al., Reference Bolleyer, Correa and Katz2018) (for a classification of our countries based on these three characteristics among long-lived democracies, see Appendix A in Supplementary material). If findings on the drivers of mortality anxiety hold across these four different systems, we can reasonably consider them as robust and generalizable to long-lived democracies more broadly.

To specify the populations of active, nationally, and regionally relevant parties and groups, we followed a ‘bottom-up strategy’ based on the most inclusive sources documenting active voluntary membership organizations available for each democracy (Berkhout et al., Reference Berkhout, Beyers, Braun, Hanegraaff and Lowery2018). In the case of groups, this assured the inclusion of a wide variety of organizations ranging from classical interest groups (e.g., business associations) to service-oriented membership organizations. In the case of parties, this strategy included all party organizations participating in elections, parties’ defining characteristic (Sartori, Reference Sartori1976), thereby avoiding a bias toward parties with privileged institutional access. To identify the relevant political parties, we used the respective party registers (UK: the Register of Political Parties of The Electoral Commission; Switzerland: Parteienregister; Norway: Partiregisteret; and Germany: Liste der Zugelassenen Parteien und Wahlbewerber). From these lists, we selected those parties that nominated candidates at the last national election.Footnote 4 Similarly, to compile the list of relevant groups we used, the Directory of British Associations in the UK, the register Enhetsregisteret in Norway, the German directory ‘Taschenbuch des öffentlichen Lebens – Deutschland 2016’ (Oeckl, 2016), and the Swiss ‘Publicus’ (Schweizer Jahrbuch des öffentlichen Lebens) (2016) as main sources. For all organizations, we checked whether they had an active website as indication that they were still in operation when the surveys were launched. We then collected – in line with our theory – up-to-date email contacts of those in charge of the day-to-day running of the organization knowledgeable about membership, procedures, activities, and resources (e.g., chief executives, chairmen, leaders, and organizational secretaries).

The response rates were the following: in the UK 21%, in Norway 28%, in Germany 30%, and in Switzerland 41%. The resulting dataset covers 828 organizations in the UK, 351 in Norway, 1420 in Germany, and 666 in Switzerland. This gives us a dataset of 3265 organizations, which is widely representative regarding the distribution of parties and groups, so are the organization-specific country samples in terms of core organizational characteristics (see for details Appendix A.2 in Supplementary material).

Measurements

Dependent variable: To capture whether organizations face an existential threat or not (i.e., experience mortality anxiety), we drew on earlier work (e.g., Gray and Lowery, Reference Gray and Lowery1997; Halpin and Thomas, Reference Halpin and Thomas2012; Heylen et al., Reference Heylen, Fraussen and Beyers2018; Hanegraaff and Poletti, Reference Hanegraaff and Poletti2019) and use the following five-point Likert scale question: ‘Sometimes, the very existence of an organization is challenged, whether by internal or external forces. Within the next five years, would you estimate that your organization will face a serious challenge to its existence?’. Our results show that 55% of the organizations in our sample perceive such a threat – either considering it as very likely, likely, or moderately likely – and 45% consider it as unlikely or very unlikely (see for more details Appendix, Table B1 in Supplementary material).

Independent variables: Starting with external resource dependencies factors contributing or complicating organizational maintenance, all ‘funding variables’ are based on the same question about the importance of different types of financial support for an organization’s budget using a five-point Likert scale ranging from ‘not at all important’ to ‘very important’.Footnote 5 An organization’s dependence on state funding (H1.1) is captured based on two items from this question, one on the importance of public funding from national government and another from other levels of government, each of which coded 1 when the funding was considered ‘important’ or ‘very important’ and 0 otherwise. Adding them up with equal weight,Footnote 6 we arrive at an index for State Funding ranging from 0 to 2 capturing its increasing importance for an organization’s budget. Private Donations (H1.2) is a dichotomous measure based on the items ‘Donations and gifts from individuals’ and ‘Donations and gifts not from individuals’. It takes the value 1 if donations of any sort were indicated as ‘important’ or ‘very important’, and 0 otherwise.Footnote 7

Organizational Maturity (H2.1) is captured by the age of the organization since foundation. Since this variable has a right-skewed distribution, we include its logarithm. Following Halpin and Thomas (Reference Halpin and Thomas2012: 227), we measure Organizational Stability (H2.2) using an additive index of five items based on a survey question capturing changes undertaken by organizations to enhance their survival prospects in the last five years. More specifically, the measure combines changes in the organization’s mission and constituency (‘first order’ identity changes) and changes in issues, policy strategy, and services (‘second order’ strategy changes) that tend to be interconnected (Halpin, Reference Halpin2014).Footnote 8 The index has a range from 5 to 0, the closer to 0 the more stable the organization is. Member Loyalty (H2.3) is based on a question asking organizations about the change in their levels of membership over the past five years. It is coded 1 if the organization increased its membership base, 0 if it remained stable, and −1 if it declined. Member Involvement (H2.4) is based on a five-point Likert scale asking participants how involved their members are in their organization, 1 being not at all involved and 5 extremely involved.

Moving to external pressures intensifying functional pressures of goal attainment, we measure Salience Challenge and Aggregation Challenge using items from a question in which organizations indicated the importance of several challenges for the maintenance of their organization using a five-point Likert scale (Hanegraaff and Poletti, Reference Hanegraaff and Poletti2019: 132–133). For Salience Challenge (H3.1), we use an item about ‘changes in public opinion about the issues important to your organization’, while for Aggregation Challenge (H3.2), we use the item on ‘individualization/growing societal diversity’. In both measures, we code an organization 1 when the respective challenge is important or very important and 0 if not. Finally, we measure Policy-oriented Staff (H4.1), an internal factor that should mediate pressures of goal attainment, as the total number of staff with a policy-oriented and/or political function. We use its logarithm because of its right-skewed distribution.

To assure the robustness of our findings, we added the following control variables. We control for organizations’ exposure to competition in two ways, a factor stressed as central for group behavior in population ecology, especially niche theory (e.g., Gray and Lowery, Reference Gray and Lowery1997). Competition Density refers to the number of organizations that compete with each other in the same ‘substantive’ area or ‘hunting ground’, either defined by policy field (groups) or ideological orientation (parties) within each country (Panebianco, Reference Panebianco1988; Gray and Lowery, Reference Gray and Lowery1997; Fisker, Reference Fisker2015). Competition density was coded manually, and we distinguished nine policy fields and nine party families, respectively.Footnote 9 We used as sources for groups’ policy orientation their websites, main activities, goals, and manifestos and for parties’ ‘family membership’ data from the Chapel Hill Expert Survey 1999–2014 (Polk et al., Reference Polk, Rovny, Bakker, Edwards, Hooghe, Jolly, Koedam, Kostelka, Marks, Schumacher, Steenbergen, Vachudova and Zilovic2017) complemented by their manifestos. Since we expect the relationship between density and mortality anxiety to be nonlinear, we use its logarithm.Footnote 10 We capture Resource Competition based on a question asking whether organizations perceive competition for new members, funds, government contracts, or other key resources by similar organizations (coded 1) or not (coded 0), an important driver of organizational behavior (e.g., Baumgartner and Leech, Reference Baumgartner and Leech2001; Halpin and Thomas, Reference Halpin and Thomas2012, Fisker, Reference Fisker2015). To capture an organization’s Specialization in terms of its political activities, another central variable in niche theory (Browne, Reference Browne1990), we constructed an additive index ranging from 0 to 11 measuring the range of political activities an organization engaged in often or very often including both insider strategies (e.g., ‘encouraging members and others to contact decision-makers’, ‘participating in public consultations’, ‘contacting government officials’) and outsider strategies (‘legal direct action (e.g., authorized strikes) and public demonstrations’ and ‘civil disobedience and illegal direct action’): the higher the score the less specialized an organization is.Footnote 11 We further control for a range of internal resources: Membership Size is measured through a question on the total number of members in the organization, while Administrative Staff is based on the total number of staff handling administrative tasks working for an organization. Both variables are right-skewed, hence, we used the logarithm. We control for Membership Fees based on the same item as the external resources (see above). The variable is coded 1 if membership fees were an ‘important’ or ‘very important’ income source in an organization, 0 if not. We also control for an organization’s Composition based on a question asking about the type of members constituting the organization. It takes the value 1 if the membership is ‘predominantly composed of individual citizens’ or ‘predominantly composed of a mixture of individuals and organizations/associations’ and 0 otherwise. We control for Organizational Type, which is based on a survey question in which organizations classified themselves as either a political party, an interest group, or a service-oriented organization. This avoids mischaracterizations, as identifying the type of organization among groups can be challenging since some can possess characteristics of both advocacy and service-oriented organizations (Binderkrantz, Reference Binderkrantz2009: 662). Finally, we include Country to account for systemic differences across the four countries.

The survey questions and descriptive statistics for all variables are provided in Appendix B in Supplementary material.

Empirical analysis

Model choice

To assess the impact of our independent variables on mortality anxiety, we use an ordered logistic regression which is the most suitable method when the dependent variable is ordinal (Fox, Reference Fox2008).Footnote 12 As we work with survey data typically characterized by a high number of missing values, we use as a robustness check multiple imputation techniques (King et al., Reference King, Honaker, Joseph and Scheve2001). The main findings remain the same, indicating that missing values are missing at random and our findings are robust (see for details Appendix, Table C1 in Supplementary material). Furthermore, as additional robustness checks, we have split our sample and replicated the main model presented in Table 3 for each country separately. Central findings hold in three or all four countries indicating that the findings are not driven by specific countries (see for details Appendix, Table C3 in Supplementary material). If not otherwise indicated, findings were substantiated by this check.

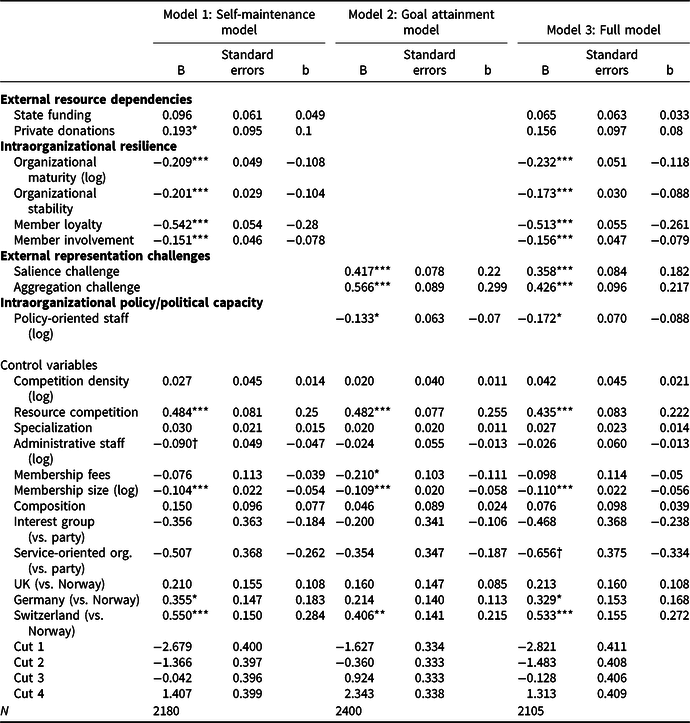

Table 3. Ordered logistic regression models for mortality anxiety

†P < 0.1, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

B = logistic coefficients; b = standardized coefficients for mortality anxiety.

Findings

Table 3 shows the results. We present three models, one containing the variables affecting organizations’ exposure to pressures of self-maintenance (plus controls) (Model 1), one with variables affecting organizations’ exposure to functional pressures of goal attainment (plus controls) (Model 2), and the full model (Model 3). While, as theoretically expected, external and intraorganizational factors associated with both types of pressures – self-maintenance and goal attainment –are drivers of mortality anxiety, it is notable that unlike the other three dimensions theorized in our framework (see also Tables 1 and 2), external resource dependencies associated with self-maintenance do not play a role though such financial dependencies are widely considered crucial for organizations’ viability and vulnerability (e.g., Gray and Lowery, Reference Gray and Lowery1997; Weisbrod, Reference Weisbrod1997; Heylen et al., Reference Heylen, Fraussen and Beyers2018; Bolleyer et al., Reference Bolleyer, Correa and Katz2018). Interestingly, while strong reliance on private funding – as theoretically expected – increases mortality anxiety in Model 1 focusing on variables related to organizational self-maintenance, the effect does not hold in the full Model 3.Footnote 13

In contrast, all factors theorized in the categories of ‘intraorganizational resilience’ (reducing mortality anxiety), ‘intraorganizational policy/political capacity’ (reducing mortality anxiety), and ‘external representation challenges’ (enhancing mortality anxiety) are significant in both the partial and full models. In the following, we discuss how the significant findings in the full model (Model 3) contribute to existing knowledge on mortality anxiety and organizational stress more generally.

Starting with organizations’ ability to cope with pressures of self-maintenance as driven by internal factors, our results highlight the centrality of organizational resilience, both in terms of the evolution of the organization and the nature of its support base. Regarding the former, we find – in line with Halpin and Thomas (Reference Halpin and Thomas2012) – that organizational stability (H2.2) lowers mortality anxiety, though unlike their study on Scottish groups, organizational maturity (i.e., age) is significant as well (H2.1). The results show that for one unit increase in the level of organization stability, we can expect a 0.09 std. dev. decrease in the log odds of higher levels of mortality anxiety, substantiating claims that self-imposed organizational changes bring their own risks and thereby enhance mortality anxiety (Halpin and Thomas, Reference Halpin and Thomas2012). Our results also show that for one unit increase in the logarithm of age, we expect a 0.12 std. dev. decrease in the log odds of higher levels of mortality anxiety. This supports prominent arguments about the ‘liability of newness’ suggesting that groups are more vulnerable in the early years when they try to legitimate their position with key audiences (Anderson et al., Reference Anderson, Gray and Lowery2004), while echoing the party literature stressing the importance of organizations’ consolidation with increasing age (Panebianco, Reference Panebianco1988). This finding is insightful as we simultaneously control for resources such as membership size. This contrasts with earlier studies on mortality rates and anxiety which did not control for age (Hanegraaff and Poletti, Reference Hanegraaff and Poletti2019: 137), or when finding an age effect often did not control for other core resources (Hannan, Reference Hannan2005: 63), or when they did, did not find an age effect (Fisker, Reference Fisker2015: 721; Heylen et al., Reference Heylen, Fraussen and Beyers2018). That said, it is also important to note that age is not significant in half of the country-specific models. Interestingly, in these two countries – Switzerland and Norway –membership size is insignificant or borderline as well (see Appendix, Table C3 in Supplementary material).Footnote 14 While our findings indicate that both age and size are factors that need to be considered in studies of mortality anxiety specifically and organizational stress more generally, future research is necessary to engage in a closer examination of the interdependencies between age as indication of organizational maturity and other central organizational properties such as size in a wider range of country settings.Footnote 15

Regarding the role of an organization’s membership base, despite debates around the declining importance of members for organizations operating in advanced democracies (Scarrow, Reference Scarrow1996; Skocpol, Reference Skocpol2003; Maloney, Reference Maloney2009; Schlozman et al., Reference Schlozman, Jones, You, Burch, Verba and Brad2015), cultivating voluntary support remains important: member loyalty and member involvement (H2.3 and H2.4) enhance the security perceived by CSOs. More specifically, for one unit increase in the level of member loyalty, we expect a decrease of 0.26 std. dev. in the log odds of higher levels of mortality anxiety, while for one unit increase in the level of involvement, we expect a 0.08 std. dev. decrease in the log odds of higher levels of mortality anxiety. Hence, the presence of a loyal membership that actively contributes to organizational work and activities assures elites that the organization is capable of carrying on with their main activities, diminishing the perception of survival threats (Heylen et al., Reference Heylen, Fraussen and Beyers2018). Furthermore, member loyalty is significant in all four country models, and it has one of the strongest negative effect on anxiety levels (see also Figure 1). In contrast, member involvement is significant only in half of the countries, suggesting that future research is necessary on how the influence of this factor is mediated by country setting.

Figure 1. Drivers of mortality anxiety in membership-based CSO. It displays the unstandardized coefficients and 95% confidence intervals of the significant explanatory variables based on Model 3; drivers associated with pressures of goal attainment in italics.

Moving on to external factors affecting goal attainment, we find support for hypotheses theorizing the role of organizations’ exposure to external representation challenges in the upper-right quadrant (Table 1). Both H3.1 and H3.2 are substantiated stressing the importance of external environmental factors that negatively affect organizations’ capacity for goal attainment: organizations confronted with a salience challenge related to changes in public opinion as well as those facing an aggregation challenge – linked to the growing diversity of their societal support base – are more likely to experience mortality anxiety (see also Figure 1). In fact, exposure to a salience challenge increases the log odds of having a higher level of mortality anxiety by 0.18 std. dev. This substantiates Hanegraaff’s and Poletti’s (Reference Hanegraaff and Poletti2019) recent finding on the link between fears related to changes in public opinion and organizations’ survival concerns for different country settings.Footnote 16 Meanwhile, exposure to an aggregation challenge increases the log odds of experiencing more mortality anxiety by 0.22 std. dev. While societal changes that make interest aggregation more difficult have been stressed as an important challenge for groups and parties alike (e.g., Dalton et al., Reference Dalton, Farrell and McAllister2011; Binderkrantz et al., Reference Binderkrantz, Christiansen and Pedersen2015; Klüver, Reference Klüver2018), the impact of such aggregation challenge has to date not been considered as driver of organizational concerns about existential threats.

Finally, our results show that organizations with higher internal policy/political capacity are less likely to experience mortality anxiety (H4.1). Concretely, for one unit increase in the number of policy-oriented staff (in its logarithmic version), the log odds of experiencing higher levels of mortality anxiety decrease by 0.09 std. dev. This contrasts with administrative staff which we included as control and has no significant effect. Hence, unlike staff contributing to basic organizational maintenance, organizations’ ability to afford specialized staff dedicated to political or policy-oriented activities enhances perceptions of security, refining earlier findings which stressed the important role of paid staff (Halpin and Thomas, Reference Halpin and Thomas2012; Heylen et al., Reference Heylen, Fraussen and Beyers2018), and, more generally, professionalization (Hanegraaff and Poletti, Reference Hanegraaff and Poletti2019).

Importantly, our findings hold despite controlling for a range of factors considered important in earlier research such as resource competition, competition density, membership size, organizational type, and composition (e.g., Gray and Lowery, Reference Gray and Lowery1997; Halpin and Thomas, Reference Halpin and Thomas2012; Heylen et al., Reference Heylen, Fraussen and Beyers2018). For instance, in line with population ecology, our results show that direct competition for resources affects organizations’ propensity to consider their existence under threat. This supports previous research suggesting that while density signals that less resources might be available for organizations, it is the perception of direct competition by similar organizations that shapes mortality anxiety (Halpin and Thomas, Reference Halpin and Thomas2012: 228; Heylen et al., Reference Heylen, Fraussen and Beyers2018).

Conclusion

This paper presented and empirically tested a framework accounting for when voluntary membership organizations constitutive for civil society consider their existence under threat. Interest groups, service-oriented organizations, and parties share a fundamental dependency on voluntary support and face growing difficulties to sustain such support in individualizing societies. These two fundamental pressures provided the foundation to analytically distinguish challenges related to self-maintenance (rooted in the former) and goal attainment (reinforced by the latter) and theorize drivers of mortality anxiety accordingly. This, in turn, allowed us to assess to which extent perceived threats to an organization’s existence are driven by factors shaping its ability to assure basic organizational functioning or those shaping its ability to achieve its goals (Wilson, Reference Wilson1973; Panebianco, Reference Panebianco1988). This is important as the demands of self-maintenance and goal attainment can be in tension with each other (e.g., Panebianco, Reference Panebianco1988; Weisbrod, Reference Weisbrod1997; Beyers et al., Reference Beyers, Eising and Maloney2008).

Applying ordered logistic regression, we tested our framework based on new survey data covering parties, interest groups, and service-oriented organizations across four European democracies. Importantly, self-maintenance and goal attainment are relevant to understand mortality anxiety, particularly factors shaping intraorganizational resilience related to the former and intraorganizational political or policy capacity and exposure to external representation challenges related to the latter. Rather surprisingly, external resource dependencies did not play a role.

Our findings – especially the factors indicating intraorganizational resilience – put earlier insights regarding the importance of membership-related resources on a broader footing (Gray and Lowery, Reference Gray and Lowery1997; Halpin and Thomas, Reference Halpin and Thomas2012; Heylen et al., Reference Heylen, Fraussen and Beyers2018), while putting debates around the declining importance of members both in the group and party literature into perspective (Scarrow, Reference Scarrow1996; Skocpol, Reference Skocpol2003; Maloney, Reference Maloney2009; Schlozman et al., Reference Schlozman, Jones, You, Burch, Verba and Brad2015). More specifically, member involvement contributes to an organization’s sense of security, which challenges traditional assumptions about the tensions between institutionalization and participation (Michels, Reference Michels1915). Meanwhile, the implications of specific types of staff such as policy-oriented staff for mortality anxiety show that the consequences of professionalization are more complex than studies considering the overall number of paid staff – which have led to contradictory findings – suggest (Halpin and Thomas, Reference Halpin and Thomas2012; Heylen et al., Reference Heylen, Fraussen and Beyers2018). That only policy-oriented staff (directed toward goal attainment) lowers mortality anxiety, while reliance on administrative staff, included as a control, does not, stresses the need to consider the specific roles different types of staff play in organizational settings more carefully in future research.

While our findings suggest the usefulness of studying parties and groups as ‘membership-based voluntary organizations’ embedded within one encompassing framework, future research should have a closer look at how the specific nature of goals organizations pursue (e.g., electoral success, policy influence and service provision) affects attempts to simultaneously respond to pressures of goal attainment and self-maintenance and how this, in turn, feeds into mortality anxiety.

Moreover, future research needs to turn the perspective around, considering the effects of mortality anxiety. To date, only a recent study by Hanegraaff and Poletti (Reference Hanegraaff and Poletti2019) has done so, showing the impact of mortality anxiety on interest groups’ influence strategies. What we do not know yet is how and how successfully membership organizations counter the mortality anxiety they experience (Heylen et al., Reference Heylen, Fraussen and Beyers2018). We might expect more vulnerable organizations to refocus attention toward efforts of self-maintenance away from goal attainment, underlining the importance of recent calls by group scholars to be more concerned with internal dimensions of group life (Beyers et al., Reference Beyers, Eising and Maloney2008: 1120; Halpin, Reference Halpin2014: 7, 28; Witko, Reference Witko, Lowery, Halpin and Gray2015: 122; Hanegraaff and Poletti, Reference Hanegraaff and Poletti2019: 126). At the same time, though organizations have generally more control over internal features than external pressures (suggesting that intraorganizational factors affecting mortality anxiety might be altered more easily), attempts to do so (if at all possible), for example, in relation to the organization’s membership base, would require costly, long-term investments. Organizations operating under heavy financial constraints often cannot afford such investments. Furthermore, as suggested by ecological theory, organizational change is costly and not necessarily effective: strikingly, we found that having undertaken changes to enhance survival chances in the last five years increased the odds of organizations to expect an existential threat in the future (see also Halpin and Thomas, Reference Halpin and Thomas2012). This suggests that even change designed to make an organization more resilient has more ambiguous effects than rationalist approaches might suggest (Collins, Reference Collins1998), at least in the short run.

If organizations’ ability to counter mortality anxiety is constrained, the latter might be an indication of actual mortality risks (Gray and Lowery, Reference Gray and Lowery1997). Indeed, recent research has shown that central drivers of mortality anxiety in our study do affect actual group and party mortality (e.g., Fisker, Reference Fisker2015; Bolleyer et al., Reference Bolleyer, Correa and Katz2018). If so, the centrality of non-resource-related variables accounting for anxiety levels suggests that organizations struggling to maintain member support, institutionalize, and/or effectively represent their constituencies may also have a harder time surviving. Our findings, then, point to another source of representation bias (Halpin and Thomas, Reference Halpin and Thomas2012: 217), a major theme in group and party research alike (e.g., Yackee and Yackee, Reference Yackee and Yackee2006; Bartels, Reference Bartels2008; Beyers et al., Reference Beyers, Eising and Maloney2008; Rigby and Wright, Reference Rigby and Wright2013). To explore the link between perceived threat and actual decline will allow us to specify when organizations are able to respond to survival threats and when such threats are a proxy for organizations’ vulnerability that soon might lead to their demise, thereby offering fundamental insights into civil society’s ability to adapt to increasingly challenging environments.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1755773920000119.

Acknowledgements

This research has received funding from the European Research Council under the European Union’s Seventh Framework Programme (FP7/2007–13)/European Research Council grant agreement no. 335890 STATORG. This support is gratefully acknowledged. We also thank all participants in the panel ‘Intra-organisational Dynamics, Change and Survival: Parties, Interest Groups and Service-Providers’ at the 68th Political Studies Association Annual International Conference at Cardiff 2018, who commented on an early version of this paper, especially Elodie Fabre and Bert Fraussen.