Introduction

Given the ubiquity of media stories of political misconduct and the widespread belief among citizens that their leaders are on the take, it is not surprising that political scientists have paid considerable attention to the phenomenon of corruption.Footnote 1 While some scholars are relatively sanguine about its effects – pointing to its alleged functional role in lubricating bureaucratic and economic transactions, especially in non-democratic polities (Huntington, Reference Huntington1968) – the majority view is that corruption has serious deleterious consequences, distorting administrative and economic processes and producing sub-optimal outcomes (see Seligson, Reference Seligson2002; Warren, Reference Warren2004 for reviews). Research has also directly linked the occurrence of corruption to citizens’ increasingly negative perceptions of their politicians and political institutions (Chanley et al., Reference Chanley, Rudolph and Rahn2000; Anderson and Tverdova, Reference Anderson and Tverdova2003; Bowler and Karp, Reference Bowler and Karp2004). It is even suggested that corruption threatens the legitimacy of the democratic process since it undermines the democratic principles of fairness, transparency, and accountability (Heywood, Reference Heywood1997; della Porta, Reference della Porta2000; Pharr, Reference Pharr2000; Seligson, Reference Seligson2002; Anderson and Tverdova, Reference Anderson and Tverdova2003, but see also Maier, Reference Maier2011). Certainly, it is an intuitively attractive proposition that the political class's perceived impropriety should shock the public, who respond by lowering their trust in their governors. As Pharr (Reference Pharr2000: 192) argues:

Corruption and ethics scandals – whether socially constructed or not, and regardless of the forces that bring them to light – have to make a difference in the bond between the governed and those who govern them in the moral universe of liberal democracies. After all, the basis for that bond involves a covenant between leaders and followers that is based on some level of trust.

Yet, the relationship between corruption and trust is unlikely to be unidirectional (Dalton, Reference Dalton2004: 198). Insofar as corruption is a phenomenon that exists in the eye of the beholder, a pre-existing feeling of mistrust towards politicians may well affect responses to their alleged impropriety, predisposing citizens to ascribe corrupt motives to their actions. Thus Mortimore (Reference Mortimore1995: 579) suggests that ‘an existing general disdain and distrust of politicians’ can make ‘a fertile ground for sowing more specific suspicions’. Della Porta (Reference della Porta2000) draws on thick description to model real and perceived corruption as both a cause and consequence of political and social trust. Likewise, Graham et al. (Reference Graham, O'Connor, Curtice and Park2003: 50) describe the findings of British focus-group research (sponsored by the Committee on Standards in Public Life) on their way to concluding that ‘it is obvious that respondents’ lack of trust in and suspicion of public office holders is the main consideration by which the acceptability of conduct is judged’. Other studies, drawing on large-N East Asian and Mexican data, have since confirmed the endogenous relationship between trust and corruption (Chang and Chu, Reference Chang and Chu2006; Morris and Klesner, Reference Morris and Klesner2010).

This paper does not deny the likelihood that exposure to alleged and actual corruption can reduce political trust; instead, and working on the assumption that individuals’ trust in politicians conditions their responses to allegations of misconduct, it seeks to explore in greater detail the ways in which trust actually shapes responses to ethically ambiguous behaviour. In particular, it explores the conditioning effects of trust in a developed industrial democracy, where corruption is generally reckoned to be less prevalent and where there is considerable variation in the degree of impropriety in politicians’ conduct that comes to public attention. Going further than previous studies, this paper thus distinguishes between different degrees of corruption and investigates the differential impact of trust in situations of varying perceived corruptness.

Drawing on data from the United Kingdom, and utilizing a quasi-experimental design, the first part of our empirical analysis models political trust as an independent variable and demonstrates that it is a significant and important determinant of how individuals respond to politicians’ behaviour. We find that those with low levels of trust are more likely than their more trusting peers to interpret politicians’ actions as corrupt. The second part then explores how different levels of trust affect responses to situations of potential corruption. Interestingly, and perhaps counter-intuitively, we find that the less trusting become relatively more critical, compared with the more trusting, as the generally perceived corruptness of politicians’ behaviour declines. We also find that trust increases in importance as a predictor of ethical judgements when behaviour is generally reckoned to be less corrupt. The analysis demonstrates that this effect is connected to uncertainty. Less obviously corrupt acts are associated with higher levels of uncertainty, which appears to open up a space for trust to play an even more significant role in individuals’ judgements of politicians’ behaviour. The final section of the paper broadens out the analysis and discusses the theoretical relationship between trust, allegations of corruption, and political scandals, with a particular emphasis on the 2009 British MPs’ (Members of Parliament) expenses scandal.

Our findings contribute to our understanding of how distrust can influence significant real-world events, and confirm the importance of political trust as an explanatory variable (for a review, see Dalton, Reference Dalton2004: 9–13, 157–190). Hetherington (Reference Hetherington1998, Reference Hetherington1999; Hetherington and Globetti, Reference Hetherington and Globetti2002) has shown that low trust causes publics to be dissatisfied with their leaders and makes it more difficult for them to succeed, increases resistance to the implementation of controversial and/or costly public policies, and increases non-incumbent and third parties’ electoral shares. Other work demonstrates that distrust, inter alia, destabilizes established electoral politics and political parties and increases support for anti-government initiatives such as term limits and tax revolts; encourages short-termism in voters and politicians; lowers the likelihood that citizens will comply voluntarily with laws, directives and regulations, with paying tax an important example; increases transaction costs generally; reduces the pool of talent from which politicians and bureaucrats are drawn; is associated with the avoidance of tough policy choices; promotes a policy environment that favours conservative over liberal reforms; and further militates against reform when individuals are required to sacrifice ideological principles (see Sears and Citrin, Reference Sears and Citrin1985; Scholz and Lubell, Reference Scholz and Lubell1998; Levi and Stoker, Reference Levi and Stoker2000: 486–495; Chanley et al., Reference Chanley, Rudolph and Rahn2001; Hibbing and Theiss-Morse, Reference Hibbing and Theiss-Morse2001: 1; Hetherington, Reference Hetherington2004; Rudolph and Evans, Reference Rudolph and Evans2005; Lenard, Reference Lenard2008; Rudolph, Reference Rudolph2009).

Not all consequences of political distrust are malign. Conservatives and libertarians probably welcome the brake on the expansion of government programmes. Meanwhile some scholars have interpreted the rise of ‘critical citizens’ to be a positive development, with the tension between public support for democracy and concern about the practice of politics providing an impetus for progressive institutional and constitutional reforms (Norris, Reference Norris1999). The majority opinion among scholars and politicians, however, is far from sanguine. As our concluding remarks make clear, we are not in the optimistic camp.

Defining terms

Both corruption and trust are terms that have been subject to a wide array of interpretations and definitions. Corruption, for instance, is a contested concept, one that is ‘laden with ambiguity and bristling with controversy’ (Anechiarico and Jacobs, Reference Anechiarico and Jacobs1996: 16). At its core, however, is usually some notion of an exchange involving the abuse of public office for private gain (Warren, Reference Warren2004: 329). The occurrence of corruption is defined by broad rules and norms (which differ across countries) concerning appropriate interactions and exchanges, and ultimately by an ideal or healthy condition of politics (Philp, Reference Philp1997: 446). A politician who acts corruptly is not just deviating from his or her expected conduct; his or her behaviour also threatens the health of the system.

Perceived corruption does not, of course, always equate with actual corruption. Citizens’ judgements about the propriety of politicians’ behaviour are likely to be based on incomplete information and to reflect subjective judgements about the appearance of a situation. Corruption may mean different things to different people, and behaviour may be deemed corrupt because ‘it looks bad’, even if there is no violation of the public interest in practice. In the context of the present study, it is therefore doubly important to distinguish between (i) corruption as an actual pattern of behaviour and (ii) corruption as a particularly severe judgement of ethical impropriety where individuals ascribe corrupt motives to actors and/or infer the presence of corruption in a given situation. Since we are interested first and foremost in how trust shapes ethical judgements, we use corruption in the latter sense and simply seek to confront respondents with a particularly stark choice about right and wrong in political life.

Like corruption, political trust is also a complex and contested term, but most analysts concur that it is helpfully conceptualized as a multi-level concept (Levi and Stoker, Reference Levi and Stoker2000). Easton's (Reference Easton1965) distinction between diffuse support for the wider political system or regime and specific support for the politicians and parties that staff the system's institutions is perhaps the most well known and useful, and was the inspiration for Norris's (Reference Norris1999) much cited five-level typology. Easton's work fed the long-running debate between Citrin (Reference Citrin1974; Citrin and Green, Reference Citrin and Green1986) and Miller (Reference Miller1974a, Reference Miller1974b; Miller and Borrelli, Reference Miller and Borrelli1991) over the object, and importance, of American citizens’ apparent mistrust. Citrin argued that declining trust was not a serious problem because it reflected dissatisfaction with incumbents rather than the system – and, of course, it is fairly straightforward to throw the incumbent rascals out. Miller was more concerned because his work showed distrust had a regime-level effect.

Also contested are what is meant when an individual is said to ‘trust’ or ‘distrust’ a politician, an institution, the government, or the system, and how best to measure it. Levi and Stoker (Reference Levi and Stoker2000) identify three approaches to conceptualizing and measuring trust. The first is a role-based definition about the extent to which political actors, broadly defined, are perceived by citizens to behave ethically and fulfil governmental functions effectively and efficiently. The second is the extent to which citizens perceive that political actors encapsulate (Hardin, Reference Hardin1999), represent, or work in favour of their interests. We are more sympathetic to the first definition than the second, but we acknowledge that some citizens may view the relationship more in a ‘what have you done for me lately’ prism. Of course, citizens themselves may have their own ideas about the concept of trust, which leads to Levi and Stoker's third and increasingly common approach that ‘leaves trustworthiness undefined, open to the interpretation of the potential truster’ (Levi and Stoker, Reference Levi and Stoker2000: 498). The present paper operationalizes the latter approach, because it is constrained by the available survey questions, which do not tap respondents’ evaluations on role-based or encapsulated trust, but instead solicit general evaluations about the extent to which government ministers, MPs, local councillors, and their local MP are ‘honest and trustworthy’.

Political trust then has both societal- and individual-level aspects. So too do corruption and perceptions of corruption, which refer to the original act of misconduct and its interpretation by the public, respectively. The result is a series of complex causal mechanisms between levels of trust, on the one hand, and perceptions of corruption, on the other. This paper does not seek to model comprehensively the determinants of actual corruption or perceptions of it (Peters and Welch, Reference Peters and Welch1978a; Mancuso, Reference Mancuso1995; Treisman, Reference Treisman2007; Birch and Allen, Reference Birch and Allen2010; Allen and Birch, Reference Allen and Birch2011). Rather, its central aims are to (i) estimate the empirical plausibility of a causal arrow running from trust to perceptions of corruption in a mature democracy using individual-level data; and (ii) explore the mechanisms underlying any causal relationship.

Research design: untangling causal effects

Clearly, extant research demonstrates the importance of trust as a general predictor of other attitudes and responses. Moreover, the causal arrow running from low trust to perceptions of corruption is theoretically plausible and has been suggested previously (Mortimore, Reference Mortimore1995; della Porta, Reference della Porta2000; Graham et al., Reference Graham, O'Connor, Curtice and Park2003; Dalton, Reference Dalton2004). What mechanism could account for the causal path from trust to perceptions? We suggest that less trusting individuals assess behaviour using a pre-existing negative schema about politics and the political class, while more trusting individuals employ a more positive schema (Axelrod, Reference Axelrod1973; Markus, Reference Markus1977). Thus, when the two types of people hear about the same event, such as an MP lying about an extra-marital affair or making a creative expenses claim, that event is likely to be viewed more negatively by the less trusting than the more trusting. Moreover, less trusting individuals may extrapolate from the behaviour of a single MP that many MPs have low moral standards, lie to cover up their antics and are on the make, an example of the so-called ‘availability’ heuristic (and bias) (Tversky and Kahneman, Reference Tversky and Kahneman1974). Mortimore (Reference Mortimore2003: 114) has suggested that a corresponding but obverse mechanism operates in the medical profession, where the high level of trust in doctors in the United Kingdom causes people ‘to treat even high-profile scandals as isolated incidents’.

Chang and Chu (Reference Chang and Chu2006) and Morris and Klesner (Reference Morris and Klesner2010) employ cross-sectional data and simultaneous equation models (SEMs) to disentangle the potentially messy causal relationship between trust and perceived corruption in Asia and Mexico, respectively. Reference Chang and ChuChang and Chu theorize that corruption influences political trust but also that trust conditions how citizens view the actions of political officials, where citizens with low levels of trust are likely to perceive higher levels of corruption in government. Their analysis indeed finds evidence of a ‘vicious cycle where corruption and trust reinforce each other’ (2006: 260) in the five Asian democracies of Japan, the Philippines, South Korea, Taiwan and Thailand. And Morris and Reference Morris and KlesnerKlesner demonstrate the existence of an endogenous relationship between trust and corruption in Mexico (2010). However, neither of the two papers speak to trust's effect in developed industrial democracies, where corruption is comparatively rare, and neither study distinguishes between different degrees of corruption.

Even more relevant is the application of simultaneous equation modelling in the two studies. SEMs, like all statistical techniques, make certain assumptions about the data under inspection. In particular, a meaningful SEM requires good instruments. Rather than estimating the direct effect of a variable – for example trust on perceptions of misbehaviour and perceptions on trust – SEMs replace the explanatory variable with an ‘instrument’ variable and estimate its effect instead. Researchers must select an instrument that influences the first endogenous variable (e.g. trust) but is uncorrelated with the second (e.g. perceptions of corruption), and select another instrument that influences the second endogenous variable (perceptions) while being uncorrelated with the first (trust). Moreover, the relationship between an instrument and the endogenous variable it proxies must be large, otherwise the estimated indirect effect will be close to zero. Finally, an instrument must not be influenced by (possibly unobserved) tastes and attitudes that also affect other variables in the model (such as trust or perceptions). Assuming such good instruments can be found, they will, when introduced into the SEM model, allow the researcher to unpick the causal paths from trust to perceptions and from perceptions to trust (see Angrist and Krueger (Reference Angrist and Krueger2001) for a good discussion of the issue in econometrics). What variables are exogenous to trust and to perceptions of corruption, and also to other factors that may influence trust and perceptions, while also demonstrating large effects on the endogenous variable they proxy? We contend that such instruments are impossible to find and justify, at least in the data to hand. While Chang and Chu's (Reference Chang and Chu2006) and Morris and Klesner's (Reference Morris and Klesner2010) work is admirable in its ambition, little information is provided about what instruments are employed or why they are valid.

The present paper, while also using individual-level cross-sectional data, adopts a quasi-experimental methodology to address the likely endogeneity between political trust and perceptions of corruption. It utilizes a series of hypothetical scenarios that were included in the April 2009 wave of the British Cooperative Campaign Analysis Project (BCCAP). Conducted between 24 and 28 April, just before the MPs’ expenses story broke on 8 May, the survey posited the following nine hypothetical scenarios involving elected politicians (adapted from Mancuso, Reference Mancuso1995). Respondents were asked to rate on a 7-point scale the extent to which they felt each of ‘the actions in each situation are corrupt or not corrupt’.

1. An MP is retained by a major company to arrange meetings and dinners in the House of Commons at which its executives can meet Parliamentarians.

2. An MP hires a spouse or other family member to serve as his or her secretary.

3. At Christmas, an MP accepts a crate of wine from an influential constituent.

4. An MP is issued with a first-class airline ticket as part of a parliamentary delegation. He or she exchanges the ticket for an economy fare and pockets the difference.

5. A Cabinet Minister promises an appointed position in exchange for campaign contributions.

6. An MP uses his/her position to get a friend or relative admitted to Oxford or Cambridge, or some other prestigious institution.

7. A Cabinet Minister uses his or her influence to obtain a contract for a firm in his/her constituency.

8. A major company makes a substantial donation to the government party. Later, the chair of the company is given an honour.

9. A local councillor, while chair of the planning committee, authorizes a planning permission for property owned by him or her.

We created a composite dependent variable by adding together respondents’ answers to the nine questions, and then dividing by nine to maintain the 1–7 boundaries. The new scale was then inverted, so a score of 1 means the respondent thought that none of the scenarios was in any way corrupt and 7 means s/he thought all the scenarios were completely corrupt.Footnote 2 The scale directly measures individual responses to potentially corrupt behaviour.

The key predictor variable is a political trust scale, based on the extent to which respondents thought government ministers, MPs, local councillors, and their local MPs are ‘completely honest and trustworthy, or not at all honest and trustworthy’.Footnote 3 Each individual's ratings were summed and averaged. A score of 0 means the respondent had no trust in any of the above and 10 represents complete trust.

While the data are cross-sectional, they provide a solution to the endogeneity problem for two interconnected reasons. The first is the order in which the trust and scenario questions were asked in the survey: the former preceded the latter in line with the logic of causal ordering (Davis, Reference Davis1985). If respondents had been quizzed about the scenarios before being asked about trust, the scenarios would have primed responses on the trust measure, making it impossible to disentangle the reciprocal effect of trust on perceptions. Presenting the scenarios to respondents after the trust questions, however, ensured that they could not possibly have contaminated the trust responses.

Yet, question ordering alone does not resolve the endogeneity issue. Regardless of the questions’ temporal order, if survey respondents had been asked to rate recent, actual instances of corruption by politicians, then it would be impossible to know whether the b coefficient generated by a regression equation reflected the effect of trust on perceptions of corruption or perceptions on trust, because of the endogenous relationship between these two factors in the real world. The reason why we can be confident that the b coefficient reflects only the effect of trust on perceptions (and not also the reciprocal effect of perceptions on trust) is that the scenarios both follow the trust question and are hypothetical. Respondents’ expressed prior level of trust cannot have pre-adjusted to the information presented in the scenarios. Of course, respondents’ level of trust will have been influenced by their previous real-life perceptions of corruption (and vice versa), but within the survey context the question ordering and the scenarios’ hypothetical nature mean that the b coefficient represents only the effect of trust on perceptions of corruption. It is important to note, however, that the hypothetical nature of the scenarios means that the results represent an estimate of the empirical connection within the quasi-experimental setting of the BCCAP data set rather than the real world.

A complicating issue is that knowledge of previous real-world political scandals garnered via the media may exert independent and separate effects on both judgements about politicians’ hypothetical behaviour and political trust, where those with a good knowledge may be less trusting and more critical of the behaviour than those ignorant of previous misconduct. Indeed, it would perhaps not be far off the mark to suggest, at least in the British case, that the journalistic mindset is now ordinarily distrustful and that distrust of politics and politicians has been institutionalized in the media establishment (Barnett, Reference Barnett2002). Thus, negative reporting of politics may in turn feed into the public's perceptions of the extent and seriousness of corruption by office holders. To address this potential omitted variable bias, which could result in a spurious correlation between trust and perceptions of corruption, we include a variable in the model that controls for prior knowledge of politicians’ misconduct and another that monitors the number of times each week that respondents read a newspaper.Footnote 4

In addition, the model controls for a range of other possible factors. It is possible that perceptions of corruption may be influenced by respondents’ party identification and/or support for the incumbent party, so we include a dummy variable scoring 1 if the respondent was a Labour supporter and 0 otherwise.Footnote 5 Respondents’ own personal ethical standards may also be important in affecting how they judge politicians. Those who are more relaxed about breaking rules and being dishonest in their private lives may be more relaxed about politicians acting similarly in public life.Footnote 6

Previous research has also determined that ideology, political efficacy and interest in current affairs may influence perceptions of corruption and should thus be controlled for in the model.Footnote 7 In addition, the model includes a social trust variable and controls for the usual range of demographic variables, including age, gender, education, and income.Footnote 8 Finally, the model includes respondents’ retrospective evaluations of their own financial situation (labelled pocketbook retrospective in Table 1) and their retrospective and prospective evaluations of the county's financial situation (labelled sociotropic retrospective and sociotropic prospective, respectively). Given the interval-level tendencies of the dependent variable, ordinary least squares regression is used to estimate the model.Footnote 9

Table 1 Determinants of perceptions of corruption

Notes: B cell entries are un-standardized coefficients. Significance values based on two-tailed tests.

The dependent variable is a corruption scale based on respondents’ answers to nine hypothetical scenarios (see the main text), scored from 1 if respondent thought that none of the scenarios was in any way corrupt to 7 if s/he thought all the scenarios were completely corrupt.

Analysis I

To recap, we hypothesize that respondents with pre-existing low levels of trust will be more likely to perceive corruption occurring within the hypothetical situations than those with higher levels of trust. A simple bivariate correlation between the political trust and perceptions of corruption scales indicates that there is a statistically significant relationship between the two, with a Pearson correlation coefficient of −0.333, significant at the 0.000 level. The negative sign suggests that less trusting individuals are more likely than trusting ones to interpret as corrupt the behaviour of politicians outlined in the scenarios. Of course, the bivariate correlation is indicative only and is a poor predictor of the substantive relationship. Multivariate analysis is required to investigate this relationship more robustly and, in particular, to control for the potentially confounding effects of other variables. Table 1 presents the results of the regression analysis.

It is clear that pre-existing levels of political trust are a significant (at 0.000) and important factor influencing respondents’ perceptions of corruption. According to the model estimated in Table 1, a one-unit increase in political trust (on an 11-point scale) reduces the perception that politicians’ behaviour is corrupt by 0.107 per unit (on a 7-point scale). To make the coefficient more intuitively interpretable, we converted both the dependent and independent variables to a 0–1 scale, with a theoretically infinite number of points in-between. Utilizing the same model with this different coding produces a correlation coefficient of −0.169, meaning that a person with complete trust in politicians will be about 17% less censorious of their behaviour than a person with no trust.

Also significant is personal ethics. People with questionable personal morality – who are sanguine about dodging fares, telling lies, and claiming benefits to which they are not entitled – are less critical of the nefarious behaviour of our hypothetical politicians than people who hold themselves to higher ethical standards. At least the ethically challenged are consistent in the sense that they do not hold others to high standards of behaviour they do not expect in themselves.

None of the three political variables – party identification, ideology, and system efficacy – are significant or even close to significant. Social trust in fellow citizens is also unrelated to people's perceptions of corruption.

We included two variables in the model to control for negative media coverage of politics, but neither knowledge of previous corruption nor newspaper readership fall within generally accepted bounds of significance. Self-ascribed interest in political affairs is also insignificant. It is possible that including all three variables in the same model could hide the significance of one or more because they possibly tap the same underlying causal influences (interest in, exposure to, and knowledge of politics), but manipulating the model to include each individually and in pairs does not raise any to significance.

Of the socio-demographic variables, only age is significant (at 0.011), with older people more likely to perceive corruption than younger cohorts. Gender, education, and income are not significantly correlated with perceptions of corruption. Neither are economic evaluations (measured three ways), which remain insignificant when included in the model in various permutations and when coded differently.Footnote 10

To gauge the relative magnitudes of the predictor variables’ effects, it is useful to examine standardized coefficients (not reported in Table 1 but available on request). These demonstrate that the pre-existing level of political trust is by far the most important predictor of people's responses to the nine scenarios (at −0.252), followed by age (0.106) and personal ethics (−0.100). Trust clearly matters.

Analysis II

The preceding analysis held the behavioural context constant (responses to the nine hypothetical scenarios were aggregated into a single scale) to determine the overall effect of trust on respondents’ perceptions of corruption. This section examines whether trust's effect differs by scenario and, if so, why.

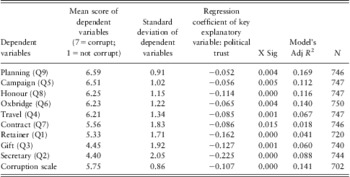

We varied the behavioural context by comparing respondents’ assessments of each of the nine scenarios in turn. In the absence of any objective measure of the corruptness of each scenario, we relied on the respondents’ collective understanding of the scenarios to separate the more obviously corrupt from the less obviously corrupt, or rather those scenarios generally reckoned to be more corrupt and those generally reckoned to be less corrupt.Footnote 11 Thus the second and third columns in Table 2 report each scenario's mean corruption score (arranged in order of perceived seriousness) and standard deviation. The columns to the right report the results of a series of regressions in which each of the hypothetical scenarios is utilized as the dependent variable. The regression models include all the independent variables listed in Table 1, but for brevity's sake Table 2 reports only the coefficients for the trust scale (coefficients for the other variables are available on request). The equations are again estimated using OLS.

Table 2 Regression analyses: political trust's effect on perceptions of corruption by type of misconduct

X Sig = significance values.

Notes: See the main text for question wording of dependent variables.

The independent variable, political trust, is scored from 10 if the respondent thought that government ministers, MPs, local councillors and their local MPs are ‘completely honest and trustworthy’ to 0 if s/he thought they were ‘not at all honest and trustworthy’. Its cell entries are un-standardized regression coefficients, controlling for all variables listed in Table 1. X Sig based on two-tailed tests.

The results demonstrate that respondents’ level of trust is a statistically significant predictor (see column five) of the extent to which they perceive politicians’ behaviour to be corrupt in each hypothetical scenario. The negative signs on all the coefficients (column four) confirm the earlier finding that less trusting individuals are more censorious of politicians’ behaviour than are their more trusting peers. On every scenario, less trusting people judged the same behaviour as more corrupt than people with higher levels of trust. Interestingly, however, Table 2 also demonstrates that trust's effect differs by scenario. While the relationship is somewhat uneven, the trust scale's coefficient tends to increase in size (column four) as the generally perceived corruptness of the offence declines (column two). Put differently, the difference between more trusting and less trusting citizens’ ratings of politicians’ behaviour is larger where the behaviour is generally considered less corrupt (−0.225 for an MP hiring a family member as his or her secretary, for example) and smaller where it is considered more corrupt (−0.052 for a councillor authorizing planning permission for his or her own property, for example). So, less trusting individuals are always more likely than their more trusting counterparts to judge politicians’ behaviour as corrupt, but the less trusting are relatively more critical (compared with the more trusting) on the less corrupt scenarios and relatively less critical on the more corrupt ones. Why?

While Graham et al.'s (Reference Graham, O'Connor, Curtice and Park2003) small-N focus-group sample precludes the drawing of any robust conclusions, the participants’ discussions raised the intriguing possibility of a role for uncertainty. The authors note:

Nowhere is [distrust's effect] more evident than in responses where participants were undecided about whether the circumstances depicted in the scenario imply any improper conduct. In the absence of any concrete evidence of misconduct, those who expressed a lack of trust in public office holders were more inclined to decide that conduct was improper in some way simply because the situation involved a public office holder – particularly where it involved an elected politician. (2003: 50)

From this, we hypothesize that trust plays a bigger role where uncertainty is high about whether a particular behaviour is corrupt or not and a smaller role where uncertainty is low. The suggested mechanism is that uncertainty may open an evaluative space that is, in part, filled by trust.

One way to test the hypothesis that trust is more important where uncertainty is high is to look at the dispersion around the mean for responses to each scenario. If the uncertainty hypothesis is correct, the perceived corruptness of each act should decrease (indicated by the mean scores in column two of Table 2) as the scenarios’ standard deviations increases in size (indicating more dispersion, and thus greater uncertainty). The standard deviations in column three, presented graphically in Figure 1, demonstrate that this is indeed the case. There is less agreement among the survey respondents when they score the less corrupt acts (such as the Gift and Secretary scenarios) and more agreement when they score the more corrupt ones (such as the Planning and Campaign scenarios). It seems likely, then, that trust becomes more important in formulating citizens’ assessments of the extent of an act's corruptness as the act falls into a ‘grey’ area and becomes less readily identified as unethical (for example, because it is no longer clearly illegal or breaks well-established social norms).Footnote 12

Figure 1 Dispersion of opinion on perceived level of corruption by scenario.

Breaking the corruptness scale down into its constituent scenarios, then, reveals some interesting aspects of trust's relationship with ethical judgements and perceptions of corruption, and it also confirms Graham et al.'s focus-group informed intuition. To push this exploration one stage further, we also disaggregated the political trust scale, dividing respondents into 10 roughly equal groups from the least trusting to the most trusting.Footnote 13Figure 2 disaggregates the data by scenario as well as trust decile. For clarity, only selected scenarios are included in the figure.Footnote 14 Comparing the standard deviations for each of the four scenarios within each trust-group column in Figure 2 reveals that uncertainty increases for all trust deciles as the generally perceived corruptness of the scenario decreases. But there are also some interesting differences across groups and scenarios. Combining the data in Figure 2 and Table 2, we find that (1) the less corrupt scenarios have higher and more even levels of uncertainty (across trust deciles), and a larger effect for trust and (2) the more corrupt scenarios have lower but more uneven levels of uncertainty (across trust deciles), and a smaller effect for trust. Thus, (3) trust is most important where individuals across trust deciles share similar and high levels of uncertainty on the less corrupt acts. Trust is still a significant predictor on the most corrupt scenarios, but appears to matter relatively less because there is greater clarity that the acts under consideration are corrupt. As uncertainty grows, so does the role of trust in determining people's perceptions of the corruptness or otherwise of the related act.

Figure 2 Dispersion of opinion on perceived level of corruption by level of trust and scenario.

Discussion

Chang and Cho (Reference Chang and Chu2006) and Morris and Klesner (Reference Morris and Klesner2010) found that people's level of political trust influenced the extent to which they interpreted politicians’ behaviour as corrupt in five Asian countries and Mexico, respectively. Put simply, low trust was associated with more negative perceptions. Based on UK data and a different methodology, the analysis above suggests (1) that this relationship also holds in more mature democracies where more obvious forms corruption are thought to be less common. (2) It also extends earlier research by disaggregating the corruption scenarios and trust scales. While less trusting respondents are always more critical than more trusting ones on each of the nine hypothetical examples of politicians’ behaviour, less trusting respondents become relatively more critical (compared with more trusting ones) as the perceived corruptness of the behaviour declines. (3) Our analysis suggests the reason is that uncertainty about the extent of an act's corruptness is highest on the least corrupt acts, and uncertainty opens a space for trust to play a more significant evaluative role. In the aggregate, then, trust is therefore most important as a predictor where politicians’ behaviour is less obviously corrupt and uncertainty is high.

Given these findings, future research may wish to consider more closely the reasons why trust is an important predictor variable. The present analysis demonstrates that uncertainty helps explain why trust's effect differs according to the seriousness of the perceived corruption. But different causal mechanisms may be in effect elsewhere. Hitherto, these mechanisms have been under-studied. Future research may also wish to explore how survey design can address endogeneity problems between key variables. Simultaneous equation modelling is the current go-to technique for social scientists seeking to unravel reciprocal causal effects but the difficulty in selecting appropriate instruments should lead analysts to be cautious about findings generated this way. As we argue above, the careful placement of survey items together with hypothetical scenarios can help researchers tease out causal effects that would otherwise be difficult to identify.

Moreover, the clear and direct link between trust and perceptions of corruption may have important real-world implications for our understanding of how diffuse levels of trust in politicians may affect the outbreak of major political scandals.

While it is common to use ‘corruption’ and ‘scandal’ as synonyms, and while they may be related empirically, they are nonetheless very distinct concepts and phenomena. Corruption, as seen, is essentially an exchange involving the abuse of public office for private gain. It can exist whenever a political actor chooses to subvert the public interest in this way. A scandal, by way of contrast, is a more complex social phenomenon in which an act or pattern of behaviour offends, and is regarded as scandalous by a critical number of people (King Reference King1986). Corruption, together with lesser forms of misconduct – or, more accurately, perceptions of corruption and misconduct – are central ingredients of scandal, but a scandal is more than the corruption itself and people's subjective assessments of and responses to it. Scandal is the whole of the reported behaviour, responses to that behaviour, and further responses to those responses. In the case of modern political scandals, the media obviously play a key role in both bringing allegations of wrongdoing to the public's attention and constructing a sense of public outrage (Thompson, Reference Thompson2000; Adut, Reference Adut2008: 11–12). Scandal is thus the societal-level response to the original corruption or misconduct, not the behaviour itself. In this sense, scandal is a public event. Scandals often surround reported occurrences of corruption, but corruption can occur without triggering a major scandal.

That the distrusting are always more critical of political misconduct than are the more trusting suggests that it is at least plausible that political trust plays an important role in the outbreak of scandal because a distrusting public is more likely to be morally offended by misconduct and therefore more likely to find it scandalous, which in turn creates more fertile territory for public scandals. For example, the hostile response to stories about MPs’ expenses claims in the United Kingdom in May 2009 may have been conditioned by pre-existing and low levels of trust among the British population (Heath, Reference Heath2011). Perceptions of MPs’ behaviour were possibly more negative than they would have been had trust been higher. In this sense, low levels of trust may have contributed to the magnitude of the scandal. This (theoretical) relationship may also help account for the increasing incidence and magnitude of scandal across western democracies in the absence of any compelling evidence that politicians are more corrupt than previously. Moreover, because trust increases in importance as the seriousness of the offence declines, even quite minor cases of misconduct could prove fertile territory for an outbreak of scandal in polities where trust is low.

There may of course be constraints on trust's role. It is possible that in democratic societies where politicians are held in exceptionally low esteem, new revelations of corruption may be greeted with a resigned shrug by citizens and journalists alike, rather than result in another scandal. And in authoritarian societies, scandal may be unrelated to corruption and mistrust, whatever the scope of corruption and the level of mistrust, in large measure because of the authorities’ control of public communication. We also do not know whether distrust is more likely to engender scandal when a large proportion of the population is generally unsatisfied or when a smaller proportion is intensely distrustful. In other words, is it the distribution or the strength of sentiment that matters more? Further, are the opinions of some social groups more important than others? Does it matter which groups are most distrusting, or is distrust an equal opportunity employer? These conjectures and questions are worthy of further study.

Although we should be cautious about the direct importance of trust, there are nonetheless grounds for pessimism. Morris and Klesner (Reference Morris and Klesner2010) point to a destructive endogenous relationship between distrust and perceptions of corruption, as each causes and reinforces the other. Similarly, if political scandal both contributes to a decline in trust and is itself conditioned by political trust via citizens’ interpretations of their politicians’ behaviour, then the downward spiral of trust is reinforced as low trust breeds scandal and scandal in turn leads to lower trust. Such a cycle is difficult to break and suggests that widespread distrust may, at least in the short to medium term, become the new norm in modern democratic societies.

There is little or no empirical evidence to support the contention that distrust can be addressed by public inquiries, political and electoral reforms, or programmes of citizenship education. Indeed, less trusting citizens are often the most vocal in demanding political reforms but are the least satisfied by reform (Curtice and Jowell, Reference Curtice and Jowell1997; Bromley et al., Reference Bromley, Curtice and Seyd2001). Yet political parties, commentators, and some scholars continue to promote them. The predictable response by the British political class to the 2009 MPs’ expenses scandal was to tighten further the regulatory regime governing allowances, but doing so may, at least in the short term and possibly in the longer term, only increase the incidence of rule infractions (because tighter rules are more likely to be broken than looser ones), increase the appearance of corruption (because an enhanced bureaucracy is in place to investigate it), increase the number of scandals (because the press will report the bureaucracy's findings), and increase distrust (because the public will respond negatively to the new scandal) – and the downward spiral may be given new momentum again.

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge financial support from the ESRC (grant number RES-000-22-3459) and British Academy (grant number SG-52322). They would also like to thank the anonymous referees and the following colleagues for their helpful comments on the manuscript: Paolo Dardanelli, Matthew Loveless, Edward Morgan-Jones, Zim Nwokora, Ian Rowe, Ben Seyd, Paul Stoneman, and Peter Taylor-Gooby.