Introduction

There is growing evidence that external factors like institutions (e.g. Duch and Stevenson, Reference Duch and Stevenson2008; Soroka and Wlezien, Reference Soroka and Wlezien2010) and the informational environment (e.g. Lupia and McCubbins, Reference Lupia and McCubbins1998; Lau and Redlawsk, Reference Lau and Redlawsk2006) affect citizens’ ability to navigate through some of the demands imposed by their political system. The impact of institutional arrangements appears especially important when it comes to voters’ ability to correctly attribute responsibility to elected officials (or parties) for their actions (or inactions). Attribution of responsibility is central to democracy because it allows voters to punish or reward office holders (or parties) in subsequent electoral contests, that is, to hold them electorally accountable. But, particular institutional arrangements sometimes make it difficult for voters to assign credit or blame by obscuring the ‘clarity of political responsibility’ (Powell and Whitten, Reference Powell and Whitten1993). This is particularly true, for example, of numerous political systems like federal ones (e.g. Canada, Germany, the United States), those where power is shared among different institutions or veto players (e.g. the United States with the Presidency, Senate, and House of Representatives), those that produce coalition governments in which more than one party is involved in policymaking, or those with a dual executive. In short, political regimes where authority is divided between several actors and institutions are environments in which it can be more difficult for voters to attribute responsibility.

To date, there have been numerous studies exploring how institutions affect the ability of voters to punish or reward officials at election time.Footnote 1 Very few studies, however, have examined whether institutions affect people’s ability to assign responsibility outside the electoral context, when the intensity of the information being communicated and people’s level of attention to politics are much lower.Footnote 2 And, only a few have started to address the issue of responsibility assignment in policy areas other than the economy.Footnote 3 This paper explores these questions using the case of Fifth Republic France.

One important institutional feature of the French Fifth Republic is that of its dual executive with a president and a prime minister. This semi-presidential political structure entails two executive officers that share power and responsibilities (Duverger, Reference Duverger1986; Sartori, Reference Sartori1997). France constitutes one variant within the large family of semi-presidential regimes (Elgie, Reference Elgie2009). It is an example of ‘premier-presidentialism’ whereby the prime minister and cabinet are named by the president but are exclusively accountable to the assembly majority; and it is an instance where the president is not a mere figurehead but rather holds significant constitutional powers, like dissolution of the assembly. The French dual executive system, however, may come at a cost for the French voters by obscuring which of the president or the prime minister is to be held responsible for failed or successful public policies and good or bad economic conditions. Moreover, while Fifth Republic France has operated most of the time under a unified executive since its inception (i.e. with a president and a prime minister from the same party or a coalition of parties on the same side of the ideological spectrum), it has experienced nearly 10 years of divided (or cohabitation, in French parlance) governments. The attribution of responsibility may well be complicated further by the type of government in place because the respective roles of the president and the prime minister are affected by this particular arrangement (Duverger, Reference Duverger1996). To be sure, France constitutes an interesting case to examine whether dual executive arrangements affect responsibility assignments over time. It allows us to test possible attribution effects in a fixed institutional context with varying unified and cohabitation governments, using measures of multiple policy areas.

Using data on the French presidential and prime ministerial popularities from the Institut Français d’Opinion Publique (hereafter, IFOP) and a methodology adapted to the study of time series public opinion data, we examine whether the French overcome the difficulties associated with this institutional feature by correctly identifying ‘Who’s the Chef?’ (Lewis-Beck, Reference Lewis-Beck1997) and ‘When?’. The findings suggest that, between elections, the French are sensitive to the peculiarities of their political system by appropriately assigning blame or credit to presidents and prime ministers when it is clear which is ‘in charge’. At other times, however, the French appear confused and unsure about which to hold accountable, and this is especially true when both share the policy agenda. Taken together, these results carry significant implications for students interested in the impact of institutions on the democratic accountability process.

Responsibility attribution under a dual executive

Central to understanding the popularity of the executive is the process underlying the attribution of responsibility. Attribution of responsibility occurs when an elected official or a government can be held accountable (or is perceived to be responsible) for an event, be it positive or negative (Shaver, Reference Shaver1985). The ability of people to identify the source responsible for the said event (i.e. an elected official or a government) depends on the availability and clarity of the political and institutional environment in providing such information (Zanna et al., Reference Zanna, Klosson and Darley1976). In electoral democracies, that kind of information is generally provided by the media, parties, elected officials, or other influential actors like union leaders or prominent intellectuals. With the information at hand, people can then apply it to their evaluation of the source deemed responsible for the fortunate or unfortunate event. Thus, attribution of responsibility occurs when people ‘take in’ information provided by their environment about the source believed to be responsible for a particular event and adjust, accordingly, their evaluation of that source.

That said, responsibility attribution for policy outcomes can be made clearer under some institutional arrangements than others. The ‘clarity of responsibility’ argument has been made most forcefully by Powell and Whitten (Reference Powell and Whitten1993) within the context of comparative economic voting studies; but the argument is general enough to be applied to all policy domains and not just the economy. The basic expectation is that a high-clarity institutional environment should lead to greater accountability by the public because it is easier for citizens to assess responsibility for a given policy outcome. Inversely, a low-clarity institutional environment should lead to less accountability because it increases the public’s confusion about who is to be held responsible. Unified policymaking is a high-clarity environment. Clarity is usually operationalized by the number of political parties involved in governance (e.g. single-party vs. coalition governments). This high–low clarity effect has been largely confirmed in the most recent economic voting literature (e.g. van der Brug et al., Reference van der Brug, van der Eijk and Franklin2007; Duch and Stevenson, Reference Duch and Stevenson2008).

But, as Lewis-Beck and Stegmaier (Reference Lewis-Beck and Stegmaier2013) argue, clarity can be about more than the number of parties in control of policymaking. It can also be, for instance, about the concentration of responsibility with one executive branch over another. As they indicate, ‘To the extent that executive authority centralizes itself in a single powerful ruler, the responsibility for managing [a policy domain] becomes less ambiguous’ (Lewis-Beck and Stegmaier, Reference Lewis-Beck and Stegmaier2013: 379). Thus, we may ask whether dual executive arrangements affect attribution of responsibility for policy outcomes. We believe that the impact of having a dual executive can be twofold. First, the sharing of power between the two actors within the executive varies from one semi-presidential regime to another (Elgie et al., Reference Elgie, Moestrup and Wu2011). Hence, the extent to which the executive officers share responsibility or not in one policy domain should have a significant impact on the capacity of the public to attribute responsibility for that domain. In policy areas where responsibility is clearly assigned to one executive branch over another, citizens should hold that executive officer accountable. In policy areas where responsibility is shared, accountability should be more diffused; in this case, allocation can depend on formal responsibility, de facto responsibility for the creation of policy, and actual responsibility for the implementation or execution of policy, with all of that being partly conditional on the informational context (Rudolph, Reference Rudolph2003; Cutler, Reference Cutler2004). Second, partisan division of power between the two executive offices should also be expected to matter. To the extent that the prime minister has more independence in performing his or her executive functions, by virtue of the fact that he or she is from a party different than that of the president, it should be easier for citizens to hold him or her accountable for his or her reserved policy domains. In other words, where there is partisan division (or ‘cohabitation’), the president loses control over domestic policymaking, which may in turn facilitate responsibility attribution to the prime minister for those policy areas.

The impact of semi-presidential institutions on attribution of responsibility has never received much attention in the literature about clarity of responsibility. Powell and Whitten (Reference Powell and Whitten1993: 402) exclude these systems from their analysis because of the complexities that they entail. Duch and Stevenson (Reference Duch and Stevenson2008: 254–262) do look at them briefly, but they limit their attention to whether the economic vote in legislative elections is stronger for the party of the president. We note again that up until recently, the only real focus of previous investigations on responsibility assignment has been on the economic policy domain. One final limitation of extant studies is that they have focused almost exclusively on the vote at election time. While elections are perfectly adequate to examine the consequences of responsibility assignments on political fortunes, they do not allow to assess entirely directly whether the public judges the performance of their executive because they do not account for all that also happens between elections, and also because voters are distracted by the presence of challengers who may distort some of the information about the government’s past performance. In addition, elections are unique in that the amount of political information in circulation and the attention people give to it are abnormally high. For these reasons, popularity series are importantly complementary to election results for examining the responsibility assignment hypothesis.

This is exactly what we do here using over 30 years of French time series data. The case of France allows us to assess the effects on responsibility attribution of the two factors most often associated with semi-presidential institutions, namely the balance of power between actors of the executive and the occurrence of partisan division. We examine these effects outside the electoral context and for a broader range of policy domains (i.e. not limited to the economy). The next section explains how the above general expectations about the role of dual executive arrangements are made more concrete in the specific example of France.

France’s dual executive system and cohabitation

In 1958, France adopted a new constitution, its fifth, after several years of political unrest and constitutional failures. The new constitution called for a president assisted by a prime minister supported by the Assemblée Nationale (the Sénat constitutes the other part of the French parliament). The powers of the president and the prime minister are defined in the Constitution, but its text contains some imprecisions and contradictions (Hoffman, Reference Hoffman1959; Wright, Reference Wright1989). For example, the Fifth Republic Constitution stipulates that the government determines and conducts national policy (Article 20.1) and that it is the prime minister who directs the actions of the said government (Article 21.1). The president, however, appoints the prime minister (Article 8.1), confirms the cabinet selection (Article 8.2), and presides over it (Article 9). The president’s legitimacy is guaranteed by his or her popular election (since 1962) and that of the prime minister comes from his or her parliamentary majority, but, then again, the president has the ability to undercut the prime minister by dissolving the assembly (Article 12.1). Even with respect to national defense the French Constitution is not entirely clear. Article 21.1, for example, says that the prime minister is in charge of national defense, but Article 15 makes the president commander-in-chief. Overall, the Constitution provides little guidance in understanding who’s responsible for what and when, as the powers of one undermine, at times, the powers of the other, and vice versa.

Luckily, the last half-century of governance under the Fifth Republic has been much more informative about the respective powers of both actors within the executive (Safran, Reference Safran1991; Duverger, Reference Duverger1996; Elgie, Reference Elgie1999). Specifically, the powers of the president and those of the prime minister are in large part a function of the parliamentary majorities (Duverger, Reference Duverger1978; Lavroff, Reference Lavroff1986).Footnote 4 The majority power thesis, developed first by Duverger (Reference Duverger1978: 120), stipulates that presidential power is a function of the nature of the parliamentary majority and the president’s relations with that majority. Thus, it is a conjectural explanation of presidential power. In its basic form, the thesis implies three modes of majority power. The first mode is when the parliamentary majority supports the president. The second mode occurs when the majority opposes him or her. And, lastly, the third mode happens when there is no parliamentary majority. We focus here on the first two because the last one, as shown in Table 1, only characterizes the first 3 years of the Fifth Republic.Footnote 5

The majority power thesis stipulates that presidents are more influential when their party, or a coalition of parties supporting them, holds a majority in the Assemblée Nationale (referred to hereafter as periods of unified government). Under such circumstances, the president appoints a prime minister of his or her liking and has more control over the actions of the government, especially over his or her ‘reserved domains’ of foreign policy and national defense (also referred to as ‘high’ politics),Footnote 6 but also over the domestic issues he or she cares most about. The prime minister, for his or her part, conducts the government’s day-to-day activities and serves as the liaison agent between the president and parliament. But prime ministers also exert influence over the domestic agenda.

However, in periods of divided government (or cohabitation), when a party, or a coalition of parties, other than that of the president controls the parliament, it is the prime minister who clearly prevails. Under such circumstances, the president appoints instead a prime minister of the parliament’s liking to ensure a working majority. This parliamentary majority gives, in turn, the prime minister the support needed to govern in his or her own right. The prime minister thus becomes, under cohabitation, the sole decisionmaker over domestic issues. The president can criticize and delay passage of legislation but cannot do much more. The president remains, however, somewhat influential over his or her said ‘reserved domains’ of foreign policy and national defense, but even these powers are considerably curtailed during cohabitation (Zarka, Reference Zarka1992; Elgie, Reference Elgie2001).

So far, there has been three periods of cohabitation: Mitterrand (PS) – Chirac (RPR):1986–88; Mitterrand (PS) – Balladur (RPR): 1993–95; and, Chirac (RPR, UMP) – Jospin (PS): 1997–2002. It became clear right from the first cohabitation (1986–88) that the prime minister, supported by his parliamentary majority, would be in a position to take center stage and isolate the president over domestic policy. Presidents under cohabitation cannot prevent prime ministers from governing, even though, as just mentioned, they can slow the pace of reforms like Mitterrand did in the summer of 1986 by denying then Prime Minister Chirac the use of decrees to pass his legislation on privatizations. But prime ministers under cohabitation can also significantly curtail the presidents’ ‘reserved domains’ powers of foreign policy and national defense by making numerous important appointments (including the Foreign Affairs and Defense Ministers, although these require some negotiation with the president) and by controlling the information necessary to conduct foreign policy and national defense that would normally reach the Elysée (Bell, Reference Bell2000).

In sum, the balance of power between actors within the executive depends upon the majorities formed in the Assemblée Nationale. Sartori nicely summarizes this balance by suggesting that French semi-presidentialism is ‘a truly mixed system based on a flexible dual authority structure, that is to say, a bicephalous executive whose “first head” changes (oscillates) as the [parliamentary] majority combinations change’ (Reference Sartori1997: 125). The ‘oscillations’, however, are not as clear cut as Sartori suggests because it is needed to distinguish between ‘low’ (i.e. domestic) and ‘high’ (i.e. foreign affairs and national defense) politics. But a close reading of the Fifth Republic allows to conclude that (1) presidents, when supported by parliamentary majorities, reign over their ‘reserved domains’, but have to share the domestic agenda with the prime minister; and (2) presidents, without a parliamentary majority, lose complete control over domestic policy and even have to share their ‘reserved domains’.

As argued earlier, particular institutional arrangements sometimes make it hard to identify who is to be held accountable. In light of the preceding discussion, however, we know that presidents dominate over ‘high’ politics during unified government and that prime ministers, for their part, dominate over ‘low’ politics during cohabitation. Thus, attribution of responsibility under those circumstances, and for those particular policy areas, should follow this pattern: blame or credit the president (prime minister) for ‘high’ (‘low’) politics during unified (divided) government.

That said, while in the case of high politics it theoretically makes sense to expect a negative impact of foreign and security-related events on the popularity of the president (to the extent that he or she is to be held partly responsible for events like these), it is also plausible to expect this relationship to actually be positive. Indeed, these kinds of events are also known to positively affect the popularity of politicians because they stir up nationalistic sentiments and fervor (e.g. Mueller, Reference Mueller1973; Kernell, Reference Kernell1978). Obviously, if we were to observe such a ‘rally-‘round-the-flag’ phenomenon, it could not fall under the umbrella of accountability in the sense that we adopt in this paper.

There remains the ‘shared’ domains during the other times, that is, domestic policy under unified government and foreign and national defense policies during cohabitation. Here, citizens should attribute responsibility to both executive officers. The public would perceive their president and prime minister working as a team, both being responsible for the initiation and implementation of policies, and, consequently, hold them equally accountable. For high politics, note again that a ‘rally-‘round-the-flag’ effect is plausible and would result in a positive impact of negative events on the popularity of both executive officers, which could not then be interpreted as evidence of responsibility attribution.

To be sure, a dual executive system does not render easy the attribution of responsibility. Nonetheless, the system presents, at times, circumstances that should facilitate the attribution of responsibility. At other times, however, it presents circumstances that may obscure instead political responsibility. The remaining questions are as follows: (1) what constitutes an appropriate measure of executive performance?; and (2) what are those typical events for which executive officials are generally being held accountable and that affect, in turn, their performance?

Popularity of the executive and its determinants

The scholarship on the popularity of the French executive is impressive. Indeed, many have tried to explain the popularities of French presidents and prime ministers (e.g. Lafay, Reference Lafay1977; Lecaillon, Reference Lecaillon1980; Lewis-Beck, Reference Lewis-Beck1980; Hibbs Reference Hibbs1981; Anderson Reference Anderson1995; Hellwig Reference Hellwig2007) but, with the exception of the recent contributions by Conley (Reference Conley2006) and Boya et al. (Reference Boya, Malizard and Agamaliyev2010), most of the work has focused almost exclusively on the role of the economy, ignoring altogether other known determinants of popularity like wars and domestic unrest. In order to test the hypotheses just presented, we propose to examine both the impact of macroeconomic conditions on the popularity of the French executive, and that of particular events like major strikes, domestic unrest, and events related to foreign affairs of national security and integrity.

Macroeconomic performance

Macroeconomic conditions, in France and abroad, have occupied a central role in most studies on executive popularity. The expectation is that executive office holders should be punished (or rewarded) for bad (or good) economic times. Macroeconomic performance is typically measured in terms of unemployment and inflation. High unemployment is an indication of stagnant or depressing economic conditions and should have a negative impact on the popularity of the executive officers because the latter are perceived as being responsible for this unfortunate situation. Inflation, on the other hand, affects people’s finances negatively by reducing their purchase power and increases in inflation should, therefore, reduce executive office holders’ popularity.

The first comprehensive study of the effects of macroeconomic conditions on the popularity of the French executive was Lafay’s (Reference Lafay1977). Lafay showed, using quarterly data from 1961 to 1977, that increases in unemployment and inflation negatively affect the prime minister’s popularity. A little later, Lewis-Beck (Reference Lewis-Beck1980), using monthly observations covering a similar period, also found inflation and unemployment to negatively affect both presidents and prime ministers, but with weaker effects on the former. Lecaillon (Reference Lecaillon1980), however, found no clear economic effects. Hibbs (Reference Hibbs1981), examining quarterly presidential popularity only, found a negative effect for unemployment but a surprisingly positive one for inflation. Conley (Reference Conley2006), looking at a much longer period (1960–2003), found monthly unemployment and inflation to negatively affect the popularity of presidents, but only inflation to affect that of prime ministers. A number of studies have found economic conditions to affect the prime minister’s popularity more so than the president’s, particularly during times of cohabitation (Lafay, Reference Lafay1991; Courbis, Reference Courbis1995; Lewis-Beck and Nadeau, Reference Lewis-Beck and Nadeau2004; Boya et al., Reference Boya, Malizard and Agamaliyev2010). And, finally, Anderson (Reference Anderson1995), using monthly data from about 1960 to 1990, found no effect for either unemployment and inflation on both presidential and prime ministerial popularity.

On the whole, the precedent work in the area has produced varying results with respect to the effects of macroeconomic conditions on the popularity of the French executive. Indeed, variables important in some are unimportant or oppositely signed in others. The differences in methodology, time period, and unit of observations (monthly vs. quarterly vs. annually) used in these studies may explain the inconsistent findings (Lafay, Reference Lafay1985; Conley, Reference Conley2006).

In the following analysis, we account for both inflation and unemployment.Footnote 7 Including the ‘big two’ macroeconomic indicators (Nannestad and Paldam Reference Nannestad and Paldam1994) can facilitate comparison with previous findings. We also improve over several of the past studies by paying attention to, and correcting for, problems arising from the possible non-stationarity of these indicators. We expect the French to punish (or reward) presidents and prime ministers for increased (or decreased) unemployment and inflation during periods of unified government when both actors within the executive share the domestic agenda. During periods of cohabitation, however, only prime ministers should be punished (or rewarded) for bad (or good) macroeconomic performances because they are the sole head ‘in charge’ of domestic matters.Footnote 8

Political events

Political events at the domestic and international levels should also affect the popularity of French presidents and prime ministers. For example, Conley (Reference Conley2006) as well as Boya et al. (Reference Boya, Malizard and Agamaliyev2010) find support for the hypothesis that ‘rally-‘round-the-flag’ events provide French presidents with a boost in approval ratings. Conley also finds major strikes to affect both presidents and prime ministers negatively with a stronger effect on the former. However, he lumps together strikes with other (and often more violent) forms of domestic confrontation and protest, so that we do not know whether the French public draws a distinction between these two different types of unrest.

We follow these authors’ approach and also account for specific political events. We separate political events into three categories, which we all include into a single French popularity model for the first time. The first category includes all events related to international and domestic terrorism with French targets leading to injury and/or death and those events implicating the French army like troop deployments and attacks against it.Footnote 9 France has suffered from several terrorist attacks, both on its soil and abroad, in response to its dealing with separatist groups (e.g. the FLNC in Corsica) or its foreign policy (e.g. the GIA).Footnote 10 If voters hold their executive partially responsible for these kinds of events, then the latter should negatively affect popularity. However, if these events instead stir up nationalistic sentiments and fervor, then we would observe a positive impact that should be interpreted more as a show of support for the nation’s leader(s) than as evidence of accountability. As hypothesized, these events should only affect presidents during periods of unified government because they reign alone over matters of foreign policy and national defense during these times. During cohabitation, however, the role of presidents is very much reduced, even over those traditional ‘reserved domains’. The public, therefore, should adjust their evaluations of both executive officers (be it negatively or positively). We label this category of events under ‘Foreign Security’.

The second category includes all major strikes. Strikes are not uncommon in France, but major strikes are defined as those disrupting French day-to-day activities are less so. Transportation strikes from the SNCF or RATP, for example, paralyze workers who use these means of transportation to go to work.Footnote 11 Similarly, strikes affecting the education, energy (EDF), and communications (PTT) sectors are also considered major because of their negative consequences on the French daily activities.Footnote 12 Major strikes should negatively affect both presidents and prime ministers during periods of unified government because they are expressions of dissatisfaction with proposed or enacted governmental policies or government’s inaction in solving particular problems, including most notably those dealing with civil servants, and generally benefit from popular support. During cohabitation, however, only prime ministers should be affected by strikes because of their dominant role in domestic policy. This second category is labeled under ‘Major Strikes’.

The third and last category includes events of domestic strife like confrontations between French law enforcement authorities and citizens or riots leading to injury and/or death and terrorist activities motivated by ideological extremism or antisemitism. This category includes, for example, events like violent student protests and the more recent suburban riots of 2005 that lasted nearly 2 months. It also includes the terrorist actions of ideologically extreme groups like Action Directe that claimed conducting an ‘urban guerrilla’ promoting communist values and the less-organized, but still terrifying, attacks against French Jews. Like strikes, domestic strife events should negatively affect both presidents and prime ministers during unified government because they publicly expose their inability to solve important social problems and to provide security for the French and their properties. During cohabitation, however, only prime ministers should be affected by domestic strife events. We label this third category under ‘Domestic Strife’. The complete list of events included in the three categories is reported in the online Appendix.Footnote 13

The popularity of French presidents and prime ministers

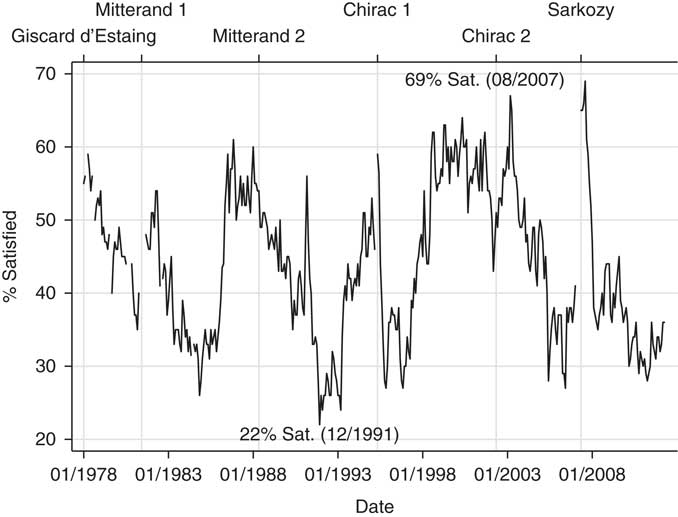

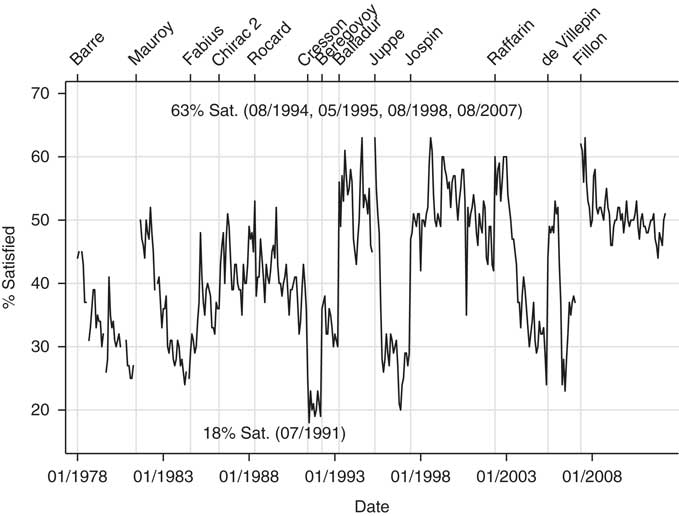

Since 1958, IFOP has asked a representative sample of the French public how satisfied or dissatisfied they are with their president, and since 1959 has also asked the same question about their prime minister.Footnote 14 There are gaps at the beginning of both series, but since the late 1960s the popularities of the French presidents and prime ministers have been measured on a very consistent monthly basis. Figures 1 and 2 present the percentage of respondents declaring that they are satisfied with the president and the prime minister from January 1978 to April 2012, respectively.Footnote 15 The decision to limit the analysis to this time period is based on the fact that the monthly unemployment rate for France, introduced later in our model, is only available from 1978. The exclusion of the first 20 years of the Fifth Republic is also justified by the fact that its early years may have been different in other ways with respect to accountability (Elgie, Reference Elgie1996).

Figure 1 French presidential popularity (1978:1–2012:4). Source: IFOP.

Figure 2 French prime ministerial popularity (1978:1–2012:4). Source: IFOP.

Figures 1 and 2 show that presidents are, on average, slightly more popular than prime ministers (43.9% of the French are, on average, satisfied with their president as compared with 42.3% with their prime minister). The most popular French president during this period is Chirac during his first mandate with an average of 48.9% of the public indicating satisfaction with him. The least popular is Sarkozy with only 39.2% of satisfied. Interestingly, the highest popularity attained by a president during this period was that of Sarkozy in August of 2007 when 69% of the French showed satisfaction with him. The lowest popularity recorded, on the other hand, was that of Mitterrand during his second mandate when his popularity hit a bottom low of only 22% of satisfaction in December 1991. The popularity of French presidents has varied widely with a standard deviation of 10 percentage points.

For prime ministers, the most popular during this period is Balladur (followed closely by Jospin and Fillon) with an average of 52.7% of the French satisfied with him, and the least popular is by far Edith Cresson with a meager 20.9% of satisfaction. Four prime ministers share the highest popularity of 63% during this period (Balladur, August 1994; Juppé, May 1995; Jospin, August 1998; Fillon, August 2007). The lowest popularity registered over the period is that of Edith Cresson in July of 1991 at 18%. The popularity of prime ministers also shows a lot of variation with a standard deviation of 10 percentage points.

Finally, note that French presidents and prime ministers have both been significantly more popular during periods of cohabitation or divided government (52.1 vs. 40.8% for presidents and 49.8 vs. 39.6% for prime ministers). This result is consistent with that for American presidents who have generally been more popular during periods of divided government (Nicholson et al., Reference Nicholson, Segura and Woods2002). It is worth noting that French presidents’ and prime ministers’ popularities have also been more stable under cohabitation, showing less variation in their popularities than during periods of unified government.

Explaining the popularity of presidents and prime ministers

Before delving into the multivariate analysis explaining the popularities of both actors within the executive, it is necessary first to pay careful attention to the peculiarities of time series data more generally. A first step implies evaluating the presence of a unit root in the popularity series. Visually examining the popularity series from Figures 1 and 2, we notice that both series exhibit a non-zero mean with no trend. We performed the Augmented Dickey-Fuller (ADF) test without a trend variable but with the inclusion of a constant term. Moreover, to account for possible autocorrelation, the test is performed with up to 12 lagged differences. The findings for both series indicate that the null hypothesis of the presence of a unit root can be rejected at the conventional 0.05 significance level. The ADF test, however, does not account for the existence of structural breaks and unspecified autocorrelation and heteroscedasticity in the disturbance process of the test equation. Thus, in addition to the ADF test, we performed the Phillips–Perron and Zivot–Andrews unit root tests to address these issues. These additional tests confirm that both series can be examined in levels.

The next step is to look at the multivariate relationships between the two popularity series, on the one hand, and macroeconomic performances and political events, on the other. The macroeconomic conditions are defined by the monthly unemployment and inflation rates. Data for unemployment and inflation come from the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) and Eurostat databases.Footnote 16 A thorough analysis of the unemployment and inflation series indicates that unemployment exhibits a unit root but not inflation.Footnote 17 Consequently, inflation enters our regression equation in levels and unemployment in first-difference in order to draw valid inferences. The unemployment variable now measures the monthly change in the unemployment rate.

The data used to construct the three political events variables, each representing one of the categories of events discussed previously, are unique. The political events series were constructed exclusively from information collected in L’Année Politique, a yearly publication that details French political life on a daily basis. The three political events variables, labeled Foreign Security, Major Strikes, and Domestic Strife, are dichotomous variables taking the value of 1 for the month in which a particular event occurred and 0 otherwise. To be more exact, the political events were coded in a way to account for the fact that the IFOP popularity series are aggregate measures of public opinion surveys that are generally fielded between the first and the 19th of each month. Consequently, events occurring on the 20th or later in a month were coded as 1 for the following month. For example, the RATP strike of 28 June 1991 was coded as a 1 for the month of July because this event clearly could not have affected the June popularity of the executive actors.

Our analysis also takes into account a well-known external shock of popularity series, that is, the election of a president or the appointment of a new prime minister. When elected or appointed, presidents and prime ministers generally benefit from a ‘honeymoon’ period in that their popularities are initially high before returning steadily, with the passage of time, to more ‘normal’ levels (Lafay, Reference Lafay1985). The period commonly refers to the first 100 days of a president’s or prime minister’s tenure. To account for this honeymoon period, the model includes a dichotomous variable that indicates the first 3 months of a president’s or a prime minister’s tenure. We expect this variable to exert a strong and positive effect on both executive popularities.

The model is completed by the inclusion of another dichotomous variable that indicates periods of cohabitation. This last variable is, in turn, interacted with the other independent variables to account for the conditional role of cohabitation on the determinants of popularity.

The estimations of these two popularity equations both exhibit the presence of strong autocorrelation in the residuals, as indicated by the standard Durbin–Watson d statistic (Durbin and Watson, Reference Durbin and Watson1950). To correct for autocorrelation, the lag of each dependent variable is included in their respective equations. Durbin’s (Reference Durbin1970) alternative test, appropriate for assessing autocorrelation when some of the regressors are lagged dependent variables, indicates that the null hypothesis of no autocorrelation cannot be rejected.

The results from the multivariate analysis for presidents and prime ministers are reported in Table 2. Note that we have good reasons to believe that the error terms of both regression equations are correlated, given that both popularity series are explained by common factors (Veiga and Veiga, Reference Veiga and Veiga2004; Boya et al., Reference Boya, Malizard and Agamaliyev2010). Thus, the estimates presented in Table 2 are from feasible generalized least squares adopting the seemingly unrelated regressions (SUR) model (Zellner, Reference Zellner1962).Footnote 18 Note also that the table reports, separately, the effects of the independent variables for periods of unified government and cohabitation to facilitate comparison.Footnote 19 , Footnote 20

Table 2 Explaining French presidential and prime ministerial popularities (from levels) (1978:2–2012:4)

SUR=seemingly unrelated regressions.

*P<0.05, **P=0.01 (two-tailed).

a Indicates the effect is statistically different (at P<0.5, two-tailed) during periods of cohabitation as compared with periods of unified government.

Not surprisingly, the lagged dependent variables show large effects and are highly statistically significant, and this, for both periods of unified government and cohabitation. This finding indicates that the series exhibit important dynamics of their own, where present values of popularity are a function of previous ones. But, interestingly, the lag of both dependent variables exhibit a much weaker effect on popularity during periods of cohabitation than under unified government and the difference is particularly strong for prime ministers (difference statistically significant at 0.05). This finding indicates that, under unified government, the current popularity of prime ministers, but also of presidents to a lesser degree, is a stronger function of its prior monthly popularity than it is under cohabitation.

As expected, both presidents and prime ministers experience honeymoons. Indeed, presidents and prime ministers are significantly more popular during the first 3 months of their mandate than they are in the remaining months. The effect of the honeymoon variable is substantial. Indeed, presidents are some 3 percentage points more popular at the beginning of their tenure. The effect is even stronger for prime ministers during periods of unified government with popularity higher on average by 4.5 percentage points. Interestingly, the honeymoon effect is weaker, although still strong, on prime ministers during cohabitation.

The coefficient estimates for unemployment and inflation indicate no effect on the popularity of both French executive officers during unified government. A χ

2 test evaluating the null hypothesis that both unemployment and inflation exert no effect on presidential and prime ministerial popularities cannot be rejected (

![]() $$\chi _{{(2)}}^{2} =0.65,\,P = 0.72$$

for presidents and

$$\chi _{{(2)}}^{2} =0.65,\,P = 0.72$$

for presidents and

![]() $\chi _{{(2)}}^{2} =1.01,\,P=0.60$

for prime ministers). Macroeconomic conditions, on the other hand, play a more important role in defining the popularity of prime ministers during cohabitation, as expected. Specifically, the estimates indicate that Inflation significantly affects the popularity of prime ministers during those times. Its effect is strong and in the expected direction with increases (decreases) in inflation leading to decreases (increases) in prime ministerial popularity. Specifically, an increase of one point in the inflation rate from its value in the previous month reduces the current popularity of prime ministers by over 7 percentage points. The effect for Inflation is statistically different during cohabitation, as compared with periods of unified government, as indicated by superscript a. Moreover, macroeconomic conditions (unemployment and inflation) exert a statistically significant effect on the popularity of prime ministers during cohabition

$\chi _{{(2)}}^{2} =1.01,\,P=0.60$

for prime ministers). Macroeconomic conditions, on the other hand, play a more important role in defining the popularity of prime ministers during cohabitation, as expected. Specifically, the estimates indicate that Inflation significantly affects the popularity of prime ministers during those times. Its effect is strong and in the expected direction with increases (decreases) in inflation leading to decreases (increases) in prime ministerial popularity. Specifically, an increase of one point in the inflation rate from its value in the previous month reduces the current popularity of prime ministers by over 7 percentage points. The effect for Inflation is statistically different during cohabitation, as compared with periods of unified government, as indicated by superscript a. Moreover, macroeconomic conditions (unemployment and inflation) exert a statistically significant effect on the popularity of prime ministers during cohabition

![]() $(\chi _{{(5)}}^{2} =31.20,\,P=0.00)$

. Finally, also as expected, macroeconomic conditions exert no influence on presidents during cohabitation

$(\chi _{{(5)}}^{2} =31.20,\,P=0.00)$

. Finally, also as expected, macroeconomic conditions exert no influence on presidents during cohabitation

![]() $(\chi _{{(5)}}^{2} =9.75,\,P=0.08)$

. Overall, these results are supportive of the hypothesis that only the popularity of prime ministers should be affected by bad or good macroeconomic conditions during cohabitation because they are alone in charge of domestic affairs like the economy. Interestingly, the French public appears unsure, however, about who to punish (or reward) during unified government for fluctuations in the economy, leaving both unaffected.Footnote

21

$(\chi _{{(5)}}^{2} =9.75,\,P=0.08)$

. Overall, these results are supportive of the hypothesis that only the popularity of prime ministers should be affected by bad or good macroeconomic conditions during cohabitation because they are alone in charge of domestic affairs like the economy. Interestingly, the French public appears unsure, however, about who to punish (or reward) during unified government for fluctuations in the economy, leaving both unaffected.Footnote

21

With regards to foreign and security-related events, we find, contrary to expectations, that the rating of French presidents is not affected by such events when they are in full control of the ‘reserved domains’, that is, under unified government. Specifically, foreign events like troop deployments and terrorist activities threatening national security or territorial integrity do not stir up nationalistic sentiments and fervor that frequently benefit presidents like they do in the United States, for example; nor do they seem to lead to some form of responsibility attribution. Foreign and security-related events also do not affect the popularities of presidents and prime ministers during cohabitation, when the ‘reserved domains’ are shared by both executive actors.

Major strikes, on the other hand, exert an important effect on the popularity of prime ministers. Indeed, strikes negatively affect prime ministers during unified governments and cohabitation. Major strikes, as strong expressions of dissatisfaction with proposed or enacted policies, negatively affect the popularity of prime ministers, as expected. Specifically, major strikes tend to reduce the popularity of prime ministers by 1.18 and 2.59 percentage points during unified governments and cohabitation, respectively. Interestingly, the French public punishes prime ministers more harshly during cohabitation, that is, in times when they are in full control of domestic affairs. Just like for inflation, the attribution of responsibility appears clearer to the French public during cohabitation.

Finally, domestic strife events do not significantly affect the popularity of French executive officers. It was initially expected that domestic strife events would negatively affect the popularity of the executive by showing the inability of governments in finding solutions for pressing social problems and preserving law and order. It appears, however, that the French do not blame their executive for their occurrences.

Overall, the findings from Table 2 demonstrate rather clearly that the determinants of presidential and prime ministerial popularity are conditioned by the type of government in place (i.e. unified or cohabitation), and in ways expected. A χ

2 test evaluating if the determinants of popularity are the same during periods of cohabitation and unified government can easily be rejected (

![]() $\chi _{{\left( 7 \right)}}^{2} =22.49,\,P=0.00$

for presidents and

$\chi _{{\left( 7 \right)}}^{2} =22.49,\,P=0.00$

for presidents and

![]() $\chi _{{\left( 7 \right)}}^{2} =32.67,\,P=0.00$

for prime ministers), indicating that the determinants of popularity are indeed conditioned by the type of government.

$\chi _{{\left( 7 \right)}}^{2} =32.67,\,P=0.00$

for prime ministers), indicating that the determinants of popularity are indeed conditioned by the type of government.

With respect to macroeconomic determinants, the French do not blame (reward) any of the executive officers for bad (good) economic times during periods of unified government. This suggests that the attribution of responsibility for the economy is obscured by this type of institutional arrangement, as suggested by Anderson (Reference Anderson1995) (and going as far back as Hamilton, 1982). In periods of cohabitation, however, the French public correctly perceives that prime ministers are de facto the unique actor over economic affairs, and adjusts, accordingly, their evaluations by punishing (rewarding) them for bad (good) economic conditions. This result is supported by the strongly significant effect of inflation on the popularity of prime ministers during cohabitation, by the appropriate t-test indicating that inflation has a statistically distinct effect on the popularity of prime ministers during cohabitation as compared with periods of unified government, and also by the χ 2 test rejecting the null hypothesis that both macroeconomic variables do not exert a statistically significant effect on the popularity of prime ministers during cohabitation. Interestingly, this finding is consistent with the precedent work on electoral accountability that finds the party of the prime minister to benefit (suffer) most from good (bad) macroeconomic conditions during elections (e.g. Lewis-Beck, Reference Lewis-Beck1997; Lewis-Beck and Nadeau, Reference Lewis-Beck and Nadeau2000; Lewis-Beck and Nadeau, Reference Lewis-Beck and Nadeau2004).

The French public also holds prime ministers solely accountable for major strikes, a domestic issue. Although the public punishes prime ministers for major strikes both under unified government and cohabitation, it does so more severely when prime ministers are in full control of domestic affairs, that is, under cohabitation. That said, a closer examination of the effect of strikes on the popularity of presidents and prime ministers suggests that this effect is conditioned by the political orientation of presidents and prime ministers (left or right).Footnote 22 Specifically, by adding to our model a dummy variable identifying leftist presidents and prime ministers and interacting them with Major Strikes, we find that only prime ministers from the left are negatively affected by strikes and in ways expected, that is, strikes exert a stronger effect on the popularity of leftist prime ministers during cohabitation when they are in full control of the domestic agenda (regression coefficient of −4.89 under cohabitation vs. −1.90 under unified government). Interestingly, the findings suggest that presidents from the left are also punished by strikes (coefficient of −1.62), but, also as expected, only in periods of unified government when both the president and the prime minister share responsibility for domestic policies. Strikes thus appear to be particularly hurtful to presidents and prime ministers from the left. This finding makes sense as unions, the main actors behind major strikes in France, are also natural allies of leftist parties and candidates. That unions strike under governments from the right is expected. But, that they do so under governments from the left demonstrates a particularly strong dissatisfaction with current policies.

Discussion

The preceding analysis suggests that the French public responds reasonably well to the peculiarities of their dual executive system by sensibly assigning blame or credit when responsibility is clearest. Indeed, they punish (reward) only prime ministers for bad (good) times during cohabitation over domestic issues like inflation or major strikes because prime ministers are sole ‘first head’ in those times. At other times, when both executive actors share the policy agenda, the French appear to refrain from holding them accountable.

These findings have important normative implications for students of the democratic process because they indicate that the French public is somewhat responsive and sensitive to the peculiarities of their political system. What is impressive about the French case is the apparent ability of its public to correctly perceive the change in the balance of powers between the two actors within the executive from unified government to cohabitation and adjust their evaluations accordingly. This result may point to the important role played by the media in France by providing close scrutiny to the actions of both the president and prime minister and especially about the latter during cohabitation.

The French institutional arrangements, however, may not always facilitate the attribution of political responsibility. This is particularly true of periods when both actors within the executive share the policy agenda. Under those circumstances, the French public appears possibly confused or unsure about which of the president or the prime minister to hold accountable and both remain unaffected. This interpretation of our findings would be in line with the idea that institutions can, at times, obscure the ‘clarity of political responsibility’ (Powell and Whitten, Reference Powell and Whitten1993), making it difficult for voters to punish or reward their executive for its actions or inactions.

Two other interpretations of these findings are possible, however. One would be that under unified control of government, voters may indeed have trouble pinning responsibility on either executive officer and, therefore, may attach responsibility to the party in power more generally. A direct test of this possible shift in responsibility attribution, from the executive officers to the party, would require to model party popularity series, which may be a fruitful avenue for future research. Another interpretation would be that the lack of responsibility attribution for the economy under a unified government may make perfect sense. That the French public does not appear to hold the executive accountable for changes in macroeconomic conditions may be rational given that politicians do not have complete control over the economy. Therefore, the public would actually be making a correct attribution of responsibility by not taking into account macroeconomic conditions when evaluating the executive (e.g. Kayser, Reference Kayser2014).

While this question of interpretation cannot be readily solved in the study at hand, our analysis nonetheless contributes to the literature assessing the regime performance of semi-presidential institutions (e.g. Weaver and Rockman, Reference Weaver and Rockman1993; Elgie, Reference Elgie2004; Cheibub and Chernykh, Reference Cheibub and Chernykh2009). Although France cannot be considered as the typical example of a semi-presidential regime, our findings show that institutional arrangements like the French dual executive lead to clear accountability for economic and non-economic performance under cohabitation only, that is, when authority is divided among partisan lines. This conclusion is worth keeping in mind given the growing popularity of the semi-presidential regime across the world (Samuels and Shugart, Reference Samuels and Shugart2010: 6; Elgie et al., Reference Elgie, Moestrup and Wu2011).

It is also worth keeping in mind given that the 2000 French constitutional reform shortening the presidential term to 5 years, like that of legislators, is likely to produce more unified governments in the future, just like it did that same year and again in 2007 and 2012, by having semi-concurrent presidential and legislative elections (semi because they are only a few weeks apart, with the presidential election being held first).Footnote 23 This constitutional reform may not end up benefiting much the French voters if it results in lower clarity of political responsibility for the fluctuations in the economy, the unmistakably most important issue on the public’s mind.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Anne Etienne for her research assistance as well as Richard Conley and Christopher Anderson for thankfully sharing their data at an earlier stage of this research project. The authors would also like to thank Timothy Hellwig and John Ishiyama for comments and suggestions.

Supplementary Material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S1755773915000351