Introduction

The European Union (EU) is no longer a project of the political and economic elite but affects all EU citizens. In turn, the attitudes of EU citizens are decisive for the future of European integration. To create an ever-closer union, it is therefore ‘imperative to identify the sources behind attitudes of support or rejection of the EU’ (Ilonszki, Reference Ilonszki2009). Some scholars emphasised the crucial influence of sociodemographic variables as a practical explanation for the difference of support for EU integration (Anderson and Reichert, Reference Anderson and Reichert1995; Gabel, Reference Gabel1998). Education, class, age, urban upbringing, and income are important factors used to distinguish between social groups that potentially benefit from integration and those that do not. Commonly, those perceived as most likely to benefit from European integration are the young and highly educated because of their better qualifications, which make them more competitive in the enlarged EU labour market (Mau, Reference Mau2005). Referring to these objective sociodemographic variables, most studies exclude gender as an important aspect in predicting attitudes towards the EU (Noe, Reference Noe2016). Gender is often applied as a control variable and not as an explanatory factor. Few studies have explored the gender gap in attitudes towards the EU (Liebert, Reference Liebert1999; Nelsen and Guth, Reference Nelsen and Guth2000; Mau, Reference Mau2005, Reference Mau2010). In the majority of these scholarly works on the formation of EU attitudes, women are described as being generally less favourable towards EU integration. These traditional theoretical explanations often point to a variety of reasons for this gap, such as women’s political interest, economic preferences, and vulnerability (Inglehart, Reference Inglehart1970; Liebert, Reference Liebert1997; Nelsen and Guth, Reference Nelsen and Guth2000; Mau, Reference Mau2005). Newer research provides a more nuanced and sometimes diverging view on gender-based support for the EU. Some studies argue that political preferences vary in different age groups (Shorrocks, Reference Shorrocks2018) and political interest may depend on national policies and gender-specific interests for political issues such as social welfare or local politics (Coffé, Reference Coffé2013).

Almost all of these studies, however, focus on Western EU member states and overlook the shifting political and economic context brought by EU membership for women in Central and Eastern European (CEE) (Słomczyński and Shabad, Reference Słomczyński and Shabad2003; Noe, Reference Noe2016). Decades of state socialism – and its legacy after the fall of communism – created powerful continuities and different perspectives on gendered discourses and practices compared to those in Western Europe (Gal and Kligman, Reference Gal and Kligman2012). Despite the ‘gender blindness’ of the EU enlargement debate itself (Regulska, Reference Regulska, Jähnert, Gohrisch, Hahn, Nickel, Peinl and Schäfgen2001), the transformation from state socialism to European integration promoted new ideological debates, initiated policy reforms, and offered new opportunities for women in Poland and other states in CEE. These dynamic developments and the potential changes in women’s political views deserve scholarly attention to assess gendered political participation in the context of developing opportunities within the EU after the fall of communism. The majority of the studies on gendered support for European integration in CEE countries argue that gender differences do not demonstrate strong disparities in public support for European integration and perceived benefits. Słomczyński and Shabad (Reference Słomczyński and Shabad2003) found that women in Poland are generally less favourable towards EU membership than men but that the gender gap is diminishing. Similarly, conducting a multiple regression analysis and cross-country comparison over time, Schlenker (Reference Schlenker2012: 107) found that sociodemographic variables in CEE do not have a strong impact on attitudes and gender has the least influence. These studies, however, include the whole population and rarely consider the social realities of young, well-educated women and men growing up in post-communist cities.

Within the group of new EU member states, Poland forms an important and interesting example of gender regimes among young people in transition. It is the biggest new EU member state, and Polish citizens constitute almost half of the population in the expanded EU (Pascall and Kwak, Reference Pascall and Kwak2005). Support for the EU is generally higher than in other CEE states (CBOS, 2017). Schlenker (Reference Schlenker2012) notes that except for Poland and Estonia, citizens in the new member states are usually less supportive of EU membership than before accession. She also finds that this decline is not specific to CEE countries and can be found across all EU member states. The European Parliament Eurobarometer 2017 concludes that generalisations are difficult because it is the national contexts that strongly influence public opinions. This is also true in Poland. Despite a high level of public support for EU integration in Poland, ‘young people’s perceptions of the EU are characterised by undercurrent Euroscepticism’ (Fomina, Reference Fomina2017: 141). The young cohorts’ attitudes have been considerably shaped by the domestic context, such as the politicisation of EU integration by Eurosceptic parties and the Catholic Church. These institutions perceive EU membership as a threat to Polish national identity and traditional family values (Warat, Reference Warat2014). However, liberal gender models from the West compete now with conservative views on gender roles and may have influenced citizens’ opinions on the EU, specifically in Poland’s urban centres (Galent and Kubicki, Reference Galent, Kubicki, Góra and Mach2010).

With this study, I aim to enrich empirical research on gender-generation gaps in EU attitudes with focus on countries that are still described as being part of a somewhat culturally distant post-communist East (Sztompka, Reference Sztompka2004). I evaluate members of the generation of Poles who are in the position to ‘create the Europe of the coming few decades’ (Moes, Reference Moes2008: 13): the well-educated urban youth. This generation is the first in Poland that has no personal experience of living in a communist political system and, instead, is faced with the realities and changes offered by EU membership. Looking at this specific cohort that is arguably benefiting the most from European integration, I ask how potential gender gaps influence attitudes towards the EU among young, well-educated people living in post-communist Poland. By addressing the gender perspective in EU support among the winners of the transition in formerly communist countries, this study contributes to the scholarly literature about the influence of sociodemographic characteristics on public opinion towards the EU. I suggest that support for EU integration among the sampled cohort of young, well-educated Polish citizens is influenced by a gender-based complex combination of personal benefits, political values, and country-specific national traditions. To understand the mechanisms behind support for EU integration, gendered political preferences and knowledge, perceptions of personal benefits, and effects of the national context should not be ignored. In my study, I demonstrate that for many young well-educated women, Poland’s EU membership offers a chance for personal self-fulfilment and the opportunity to be integrated into a political system that promotes more liberal views, compared to the conservative domestic discourse at home. To shed light on the influence of gender as a context for attitudes towards the EU among the representatives of the young well-educated generation in Polish cities, I posit the following research questions:

Do well-educated young women and men living in Poland’s urban areas differ in their attitudes towards the EU and in their perception of personal benefits?

What factors influence these well-educated young women and men in their assessment?

Adopting a mixed-methods approach, I provide a comprehensive assessment of this young cohort’s social world. My sample of young, urban, well-educated citizens – although not representative of all young citizens in Poland, serves as a microcosm through which to better understand the process of modern gendered views on EU integration in CEE. The collection of comparable data on a subnational level contributes to a better understanding of gender-related differences and idiosyncrasies in Poland. My research hereby highlights the change of norms and values in post-communist urban societies after EU accession.

The first section of the study evaluates the literature and theoretical assumptions on potential gender gaps in support for European integration and utilises these theoretical approaches to evaluate previous data on attitudes towards the EU in Poland. The section is structured along political interests, economic approaches, and Poland’s national context. Secondly, I present the data and the methods to evaluate the gendered perspective on integration among the sampled young, highly skilled individuals using survey data and semi-structured interviews. Subsequently, I discuss the results of the mixed-methods analysis and provide a conclusion and suggestions for further research.

Theoretical background: gendered attitudes towards the EU in Poland

Studies on gendered attitudes towards the EU suggest a diverse set of attempts to theorise public opinion. Borrowing from the relevant literature on the topic, three gender-related aspects for explaining public support for European integration among the well-educated young population in Poland emerge, namely: political interests and preferences, economic utilitarian incentives, and national characteristics. The relevance of theories assessing attitudes towards the EU within the sampled cohort of well-educated young citizens in Polish cities is guided by the insight that the public opinion among the so-called ‘winners’ of the post-communist transition period (Tucker et al., Reference Tucker, Pacek and Berinsky2002) serves as an indicator for transformations in CEE after European integration.

Political interests and preferences

Traditional gender gap perspectives suggest that differences in public EU support appear as manifestations of diverging political interests between men and women. The ‘female deficit hypothesis’ assumes that women are generally less interested in politics and if they become politicised, they hold more traditional views than men (Liebert, Reference Liebert1997). Some studies, such as the one conducted by Inglehart (Reference Inglehart1970) argue that women tend to show less support for European integration because of the higher levels of political interest and cognitive mobilisation among men. The underlying assumption of female deficits of these earlier studies has slightly changed over time. In newer studies, some scholars argue that the lack of support results from women’s unfamiliarity with EU politics and commitment to traditional values. In Nelsen and Guth’s (Reference Nelsen and Guth2000) study, political distance proved to be a good predictor for individuals’ attitudes towards the EU in all 15 evaluated countries. More women than men stated that they know little about EU integration but conservative values make predominately men less supportive of EU integration in some countries. Similarly, Fraile and Gomez (Reference Fraile and Gomez2017) acknowledge that overall, women declare lower levels of political interest and knowledge but suggest that this gender gap could be alleviated by promoting gender equality, especially for older generations. Yet, gender-friendly policies may not always reach younger women. Due to their childhood socialisation influenced by traditional family values, the gender gap of political interest within this cohort is often present even in countries with greater gender equality. Some studies also show that ‘political interest’ may not necessarily mean the same for men and women (Coffé, Reference Coffé2013). According to this strand of research, women know less about the EU than men but more about social welfare and local politics. With regard to political preferences, some analyses argue that an age-related modern gender gap in left–right self-placements emerges in Western countries (Corbetta and Cavazza, Reference Corbetta and Cavazza2008; Shorrocks, Reference Shorrocks2018). In her study, Rosalind Shorrocks (Reference Shorrocks2018) argues that in younger cohorts in Western states, women are more left than men whereas the opposite occurs in older cohorts. This modern gender gap among young women appeared due to ongoing secularisation, more support of equality, redistribution, and state intervention to mitigate economic vulnerability. All these comparative studies allowed for the evaluation of cross-national variations and more nuanced analyses of gendered political interests in Western European countries. They further demonstrate the complexity of gender-based political preferences and support for the EU as not all studies include the same variables and cases.

Looking at Poland, public opinion towards integration has been favourable since its accession into the EU in 2004, although never unequivocally positive. The latest European Parliament Eurobarometer 2017 measured 65% support for the EU in Poland, whereas 7% had a negative opinion, and 26% reported neither good nor bad attitudes towards the EU. These figures reveal more support for EU integration than in other countries of the Visegrád GroupFootnote 1 (CBOS, 2017).

Slightly more men (51%) than women (49%) in Poland have a positive image of the EU. However, women (40%), more often than men (32%), have a neutral image and men (16%) see the EU generally more negatively than women (9%) (EB 88, 2017b). Looking at political distance as indicator for EU support, 71% of Polish citizens claim to understand how the EU works. This level is even higher among young people (15–24 years) – 82% and 88% among students (Fomina, Reference Fomina2017). Intriguingly, more men (82%) than women (72%) argue that they understand how the EU works (EB 88, 2017b).

These results do not necessarily contradict previous findings and theoretical explanations on gender-based support for the EU (Inglehart, Reference Inglehart1970; Liebert, Reference Liebert1997; Nelsen and Guth, Reference Nelsen and Guth2000) but the numbers make no statement on specific differences in political interest or the nature of age-based political preferences, and struggle to reveal the underlying reasons for differing EU attitudes between men and women. In this research, I argue that the sampled young, well-educated women living in Polish cities show equally positive attitudes towards the EU as men and that these positive attitudes might be a result of better political knowledge of the EU.

Economic utilitarian incentives

The human capital theory suggests that urban citizens with higher education and better cultural resources are more likely to support integration because they are in a better position to take advantage of free movement and facilitated access to a larger job market (Pichler Reference Pichler2009a, Reference Pichler2009b; Teney et al., Reference Teney, Promise Lacewell and De Wilde2014). Regarding gendered differences, Torres and Brites (Reference Torres and Brites2006) argue that increasingly similar education levels of men and women induce a diminishing gap in attitudes towards the EU among the two sexes. Other research demonstrated that economic utilitarian theories are able to reveal certain nuances in how benefits are perceived between men and women. According to Nelsen and Guth (Reference Nelsen and Guth2000), women might view EU integration as a threat if the economic costs of a country’s EU accession fall on individuals instead of the government. Some feminist scholars (e.g. Kofman and Sales, Reference Kofman, Sales, Garcia-Ramon and Monk1996) criticise the EU for its focus on a neoliberal agenda and economic competition that challenges women’s social needs and the fundamental principles of the welfare state. If European integration leads to higher personal costs regarding welfare policies, women may have a less favourable view on the EU (Vitores, Reference Vitores2015). Focusing on perceived personal benefits among men and women, Mau (Reference Mau2005) states that such gendered effects are not very strong but significant in 10 of the 15 analysed member states. The different views may result from a higher reliance of women on the state (Mau, Reference Mau2005: 300). Related to individually perceived benefits or disadvantages, Liebert (Reference Liebert1997, Reference Liebert1999) adapted the theory of ‘relative deprivation’ with a focus on collective perceptions. She found that women are less supportive of the EU if they expect European integration ‘to deprive them relatively from what they already have attained at their national or local level’ (Liebert, Reference Liebert1997: 22).

In Poland, most citizens voted for EU accession to secure better opportunities for their children. A decade later, the majority of Poles acknowledged personal benefits they experienced resulting from European integration (Ministry of Foreign Affairs, 2014). Among the most important advantages were economic growth, facilitated free movement within the EU, and better work opportunities (EB/EP 88.1, 2017). Gender-related economic aspects are also reflected in public opinions among Poles. According to the Eurobarometer (EB 88, 2017b), 33% of all surveyed men perceive the economic perspective in Poland as good, and 28% of the sampled women have a positive opinion about the outlook for the national economy. Results about perceived personal benefits stemming from Poland’s EU membership are also rather balanced. For the majority of women (58%) and men (55%), the EU stands for better freedom of movement, travel, and work.

Looking at these surveys conducted among Polish men and women, I expect that the sampled cohort of young, well-educated men and women in Polish cities show similar or even higher levels of EU support because they expect to personally benefit from EU integration. However, the question remains if there are any specific gender-based reasons that influence the individual perception of economic benefits and costs resulting from Poland’s EU membership (Mau, Reference Mau2005) or if education mitigates these differences (Torres and Brites, Reference Torres and Brites2006).

National traditions and contexts

Eichenberg and Dalton (Reference Eichenberg and Dalton1993) theorise national traditions in foreign policy as an important factor for attitudes towards the EU. Nelsen and Guth (Reference Nelsen and Guth2000) confirm that gendered attitudes towards the EU may be anchored in national traditions, domestic political contexts, and national identities, without specifying such national historical trajectories. Despite the importance of national traditions and the accession of post-communist countries to the EU, most of the research on attitudes towards European integration has been conducted in Western Europe (Christin, Reference Christin2005). Some scholars argue that it is important to focus on specific characteristics in CEE countries as there is no West European equivalent to the extensive economic and social shifts taking place in new members states and therefore no equal effect on citizens living in post-communist countries (Tucker et al., Reference Tucker, Pacek and Berinsky2002; Christin, Reference Christin2005). Fomina (Reference Fomina2017) argues that Polish citizens generally supported EU integration because it gave them the opportunity to move on after the fall of communism and to return to Europe. Yet, most Poles did not fully grasp the political mechanisms of European integration and did not necessarily share the EU’s values and principles. To better understand these dynamics and the context in which Polish women develop their views on the EU, it is worth looking at gender policies, the role of the Catholic Church, and aspects of geopolitical security. Communist states introduced gender equality, prohibited discrimination, and offered equal access to the labour market but these policies did not challenge the traditional understanding of gender roles in private life (Zielińska, Reference Zielińska2016). Family and domestic obligations were hardly challenged, political representation remained low and despite high levels of female employment, payment was not equal. After the fall of communism in 1989, previous gender polices were seen as a remnant of state socialism. A strong anti-feminist movement emerged led by the Catholic Church and conservative parties, which reinforced the traditional vision of women as mothers and wives (von Wahl, Reference Von Wahl and Roth2008; Warat, Reference Warat2014). Gerber (Reference Gerber2011) argues that Poland differs from other CEE states in the degree to which it pursued the re-traditionalisation of previous gender arrangements. The narrative of the Polish national identity revolves more around religious identification than civic nationalism (Zubrzycki, Reference Zubrzycki2001). The church promoted a traditional model of women as homeworkers and mothers, which was based on the idea that women have a certain place and an assigned role in society for the good of the country. ‘Polish national identity is inseparable from Christian Catholic values understood as socially conservative norms’ (Fomina, Reference Fomina2017: 154). Attempts to challenge these norms, such as promoting gender equality, would be perceived as a threat to national identity.

Equal opportunity laws were only adopted under strong pressure of the EU during accession talks. During these negotiations, the nation was also caught between the twin impulses of independence after the fall of communism and the will to become integrated again as part of the EU (Gerber, Reference Gerber2011: 506) and large segments of the population faced social, political, and cultural changes. The Catholic Church supported EU accession with much ambivalence (Fomina, Reference Fomina2017) but the ongoing pressure from Eurosceptic groups and members of the church led to difficulties in negotiating legislation related to gender equality (Warat, Reference Warat2014). These processes of democratic transition were, and still are, very challenging and complex. The transition to a competitive market economy proved especially difficult for women. In addition to ongoing economic changes, right-wing parties and the Catholic Church in Poland continue to promote policies of nationalism and a re-traditionalisation of gender roles (Siara, Reference Siara2013).

Politically, EU accession had a positive impact on Poland’s international security. The long history of communist rule and foreign domination resulted in a rather positive attitude towards European integration. A CBOS survey (2014) shows that 72% of the surveyed population in Poland believe EU membership increases the country’s security. Most participants of the CBOS survey referred to the country’s history as a communist satellite state and the distrust they maintain against the current Russian state. This results in a vast majority of these respondents (80%) identifying Russia as main security concern and is equally prevalent for both sexes in Poland. For women (25%) and men (26%), peace and security are the second most important personal benefits resulting from EU membership (EB 88, 2017b). This rather grief-stricken preoccupation with Poland’s history illustrates that, despite the lack of personal experiences, young Polish citizens are still in the process of coming to terms with the country’s past and political trajectory. Yet, there is a notion of relief that emerges from the feeling of belonging to a larger community that offers protection against any potential Russian threat.

As a consequence of Poland’s communist history, the generation of young citizens born after 1989 has been socialised within a different political and economic reality than their parents but in a still traditional cultural system that impacts on political views and opportunities (Jakubowska and Kaniasty, Reference Jakubowska and Kaniasty2015). Two connected characteristics are still apparent in today’s Poland: economic liberalism and cultural conservatism, including a low level of gender equality (Noe, Reference Noe2016). However, Morokvasic (Reference Morokvasic2004) notes that the post-communist transition towards a market economy and European values has slowly changed the lives of young women. Today, they often refuse to accept traditional gender expectations and individually benefit from freedom of movement and new opportunities within the EU. Similarly, White (Reference White2010) states that young citizens display now more egalitarian attitudes than previous generations. These developments raise questions about the normative power of Europe and future of support for the EU among young, well-educated women. Including gender into the scholarly debate underscores the necessity of studying sociodemographic differences in post-communist societies. Based on the presented national context and traditions, I assume that well-educated young women in Poland show generally positive attitudes towards the EU and that they tend to share liberal values brought by European integration that stand in contrast to national advances towards re-traditionalisation.

Data and method

Sampling and data collection

I conducted the investigation in five large cities in Poland: the Tricity Area (Gdańsk–Sopot–Gdynia), Poznań, Warsaw, Wrocław, and Kraków. The target population in this study are Polish MA students, who live and study in these urban areas. I recruited students from various colleges at each university, including Arts and Humanities, Social Sciences, and Science and EngineeringFootnote 2. Legal restrictions, issued by the respective universities, prevented me from conducting a probability sample.Footnote 3 This means that no randomisation was possible, and generalisations cannot be drawn from the sample used in this study. Nevertheless, my research contributes to solving the puzzle of gendered support for European integration in CEE. The surveyed population includes 815 MA students. Subsequently, 27 MA students allowed me to contact them for a semi-structured interview. Each interview lasted between 60 and 75 minutes.Footnote 4

The number of female MA students who answered the questionnaire (70.40%) was much higher than the number of male MA students (29.60%). This unequal distribution is also prevalent when looking at MA students who are studying at the universities where I conducted the survey. The numbers confirm that more women (64.95%) than men (35.05%) are enrolled in MA programmes at the universities of the selected cities and corroborate the assumption that my sample is similar to the actual distribution of men and women.

Methodological approach

I apply a mixed-method approach on my assessment of the well-educated youth in Poland. This ensures a more in-depth understanding of citizens’ perceptions and actions. To measure if the well-educated men and women differ in attitudes towards EU integration (‘EU attitudes’) and perception of personal benefits (‘EU for you’), I asked the MA students the same questions as have been asked in the Eurobarometer since 1973 to measure support for the EU: ‘Generally speaking, do you think that Poland’s membership of the European Union is a good thing (3), a bad thing (1) or neither good nor bad (2)?’ The same question was previously used in other studies to measure support for European integration (Gabel and Whitten, Reference Gabel and Whitten1997). I also asked the students if ‘Poland’s membership of the EU is a good thing (3), a bad thing (1) or neither good nor bad (2) for their personal benefit?

The qualitative part of this study addresses potential reasons for the quantitative findings. I analysed the data along the theoretical approaches using the Nvivo software. To ensure comparability, I generated coding categories and checked their consistency throughout the interview process. The aim is to understand why men and women think about European integration the way they do, thereby providing an in-depth and nuanced exploration of the sampled student’s feelings, thoughts, and understandings. The semi-structured interviews included questions about EU attitudes, political interests, economic utilitarian drivers, and national traditions and contexts. I asked the students to explain in detail: their individual view on the EU and national politics, their personal economic situation and perceived benefits resulting from Poland’s EU membership, and their opinion on national identity and Poland’s historical narratives. I then analysed the different dimensions of the categories and identified relationships between them to uncover specific patterns related to the theoretical approaches. The identical level of education and the demographic requirements allowed me to focus on gender as a variable that might influence respondents’ opinions on the EU and personal benefits.

Analysis and results

To assess the research question, I first present the quantitative data, followed by the results from the semi-structured interviews. I used nonparametric procedures to analyse the questionnaires because data were not normally distributed and measured in an ordinal scale. More specifically, I apply Spearman’s rank-order correlation (ρ) for ordinal data, to test for the strength of the monotonic relationship between variables that are not drawn from a probability sample (Siegel and Castellan, Reference Siegel and Castellan1988).

Gender and EU attitudes: quantitative results

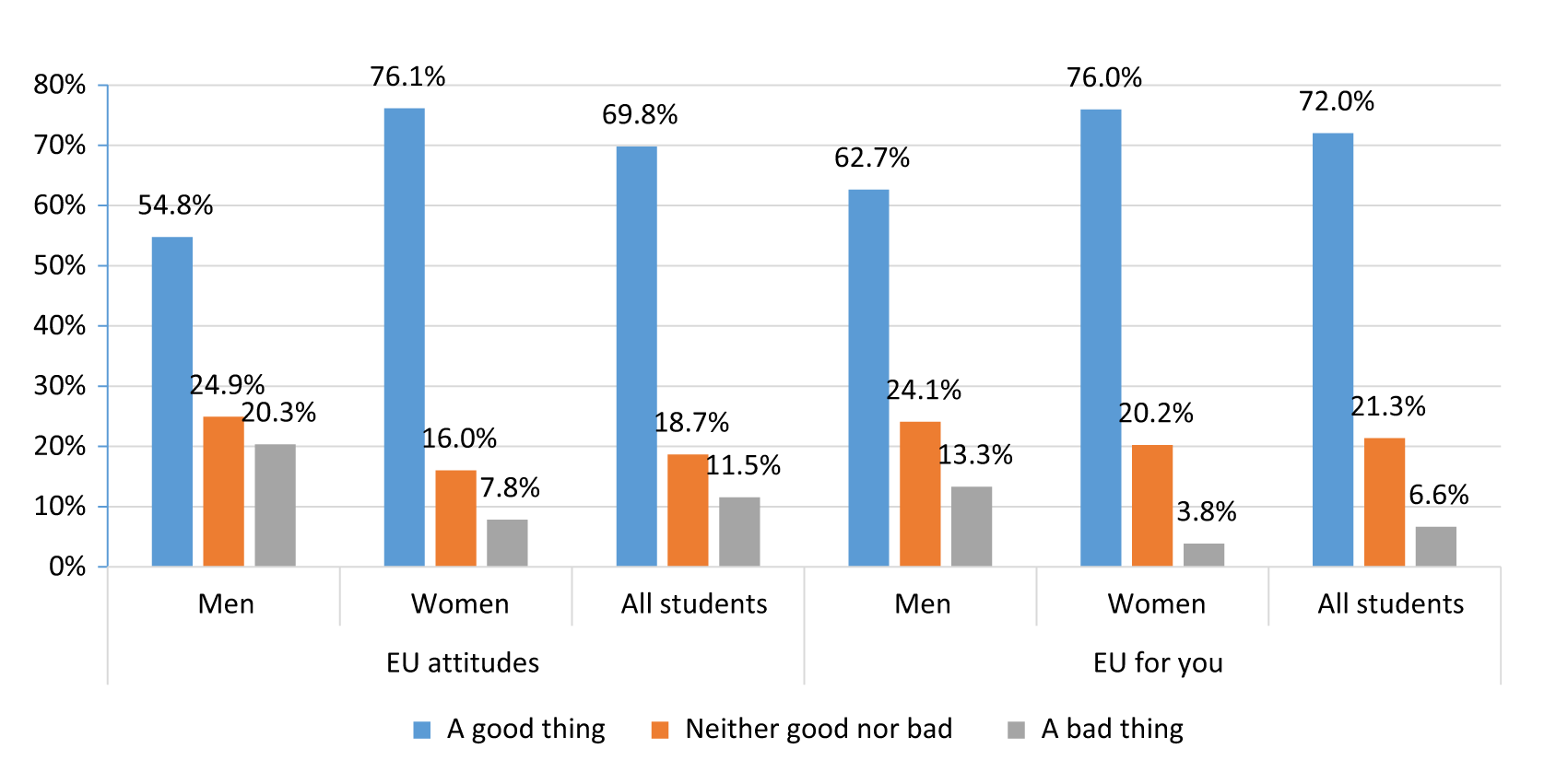

Based on the literature, I previously assumed that the sampled young well-educated women show similar levels of EU support as the men in my study. To evaluate if attitudes towards EU integration and the perception of personal benefits resulting from EU membership differ (or not), I first analyse the data descriptively by presenting an overview of the answers to the questions. Figure 1 shows the results in percentage (%), broken down by gender.

Figure 1. Gender-based attitudes towards EU membership and perceived personal benefits.

The data show that the majority of the surveyed students (69.8%) had a positive perception of Poland’s EU membership. This number is higher than the outcome for the whole country (65%), as measured by the European Parliament (EB/EP 88.1 2017). The same applies for results on personal benefits from Poland’s EU membership. Most students (72%) indicate that EU membership is a good thing for them. Interestingly, male students are considerably less supportive of EU membership (54.8%) than female students (76.1%). The sampled women are also much more convinced that EU membership is a good thing for them personally (76%) than the sampled male students (62.7%). The stark differences in perception of benefits and EU attitudes between the surveyed well-educated men and women highlight an important point. The surveyed women are generally more enthusiastic about the EU than men. The question remains, what makes these young, well-educated women so supportive of EU integration? A main concern in the academic literature is the association of European integration with personal economic benefits.

I tested if gender influences the correlation between EU attitudes and the subjective perception of personal advantages resulting from Poland’s EU membership. Based on academic literature and previous survey results, I argued that well-educated young women associate EU membership less with economic costs but with personal economic benefits. To assess this association, I split the data sample by gender to show the correlation of the two variables. Table 1 presents the results.

Table 1. Correlation with positive attitudes towards the EU (‘EU attitudes’)

** Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (two-tailed).

Source: Authors’ survey.

N = 815.

N women = 574, N men = 241.

The coefficient shows that the variables are highly correlated for both men and women. This connection indicates a strong positive relationship between the ranked attitudes towards the EU and perceived personal benefits from EU membership. In other words, within the sampled population of young well-educated urban residents, attitudes towards European integration coincide with the individual subjective assessment of personal benefits. Gender differences do not play a strong role in this assessment process but the correlation between the variables among men is slightly higher. This indicates that men tend to have a somewhat more positive attitude towards the EU if they are also satisfied with the personal advantages from EU membership. But what are the specific factors that influence these well-educated young people in their assessment? And are these factors different among men and women? The qualitative analysis aims to address these questions.

Gender and EU attitudes: qualitative results

The first questions aimed to elicit the interviewees’ level of political interest and personal political preferences. During the interviews, over 90% of all students voiced clear opinions about the EU, national politics, and local political issues. Their statements showed awareness and informed critical opinions. Regarding local politics, men and women had a fairly similar view on policies conducted by the authorities of their respective city. Almost all of the sampled students mentioned public transport as an important aspect for the development of the city and for the improvement of their personal environment and quality of life. Some students also acknowledged that the EU invests in urban development, which in turn benefits local residents.

At the national level, the sampled students frequently mentioned the current political milieu in Poland, with the Law and Justice party (Prawo i Sprawiedliwość, PiS) being the dominant party. Most interviewed students had a rather negative view of the party’s conservative ideology and the shift towards more nationalistic tendencies, but women were much more vocal in their opinion and did not contain their incomprehension. At the same time, several women said that the party’s anti-feminist policies invigorated their interest in national politics and law, and some of them attended mass demonstrations against PiS taking place in Poland’s bigger cities. Only two of the male interviewees expressed similarly explicit negative opinions.

The party’s policies also led to friction with the EU, which was another reason for concern predominantly among the interviewed women. They feared that the EU might not remain inactive and will take actions, for example, that they will lose investments or the EU’s trust. Some of the sampled female students were worried about the reputation of Polish citizens abroad and voiced concerns that disputes over democratic values and judicial independence could negatively affect Poland’s image in Europe.

Regarding Poland’s EU membership, men and women were equally critical about certain aspects. The potential loss of the country’s autonomy and the feeling of being ruled by bureaucrats in Brussels were repeatedly criticised. One student noted: ‘I think there are bad things resulting from unification. That someone in the government of the EU tells us what we should do, and we have to adjust to their laws’ (JKo, F, Kraków). Related to this lack of independence was the notion that the EU was unnecessarily meddling in the Polish economy by imposing new laws and norms, which in turn prevent Polish products from being produced and exported. A few students specifically mentioned the European Commission’s tough stance on emissions caused by coal, which hurts the largely coal-powered Polish economy, and issues for traditionally produced Polish food. Aside from these critical views, several students referred to actual projects funded by the EU, such as energy and infrastructure that are beneficial for Poland’s development. Indeed, within the financial framework 2014–2020, Poland will be the ‘biggest EU funds beneficiary among all the member states’ (OECD, 2018).

The second set of questions was intended to determine economic utilitarian incentives of support for European integration. The majority of the sampled students issued positive views on personal benefits resulting from Poland’s EU membership. Almost all students mentioned freedom of movement and Erasmus programmes as beneficial for their personal future. This is no surprise given the fact that Poland was the fifth highest participating country in Erasmus programmes in 2016 (European Commission, 2017a). However, the motivations and incentives to take advantage of free movement and open borders differed between the sampled men and women. Whereas most interviewed male students mentioned economic aspects – such as higher salaries and facilitated access to the European labour market – many women expressed their motivation to travel more, to learn a new language, to visit interesting parts of Europe, and to meet young people from other countries. This discrepancy shows a difference in focus of utilitarian aspects that are not only connected to a better job and salary but also include the value of cultural exchange, which can be crucial for personal enrichment or future career development. The sampled women perceived the EU as a space where they could use their knowledge and skills to broaden their horizons and to advance their personal development.

The results also show that the interviewed women did not mention higher personal costs, a threat to welfare, or fears of relative deprivation due to Poland’s EU membership. The real threat often mentioned by female students was the potentially negative influence of the Eurosceptic Law and Justice party on their personal benefits resulting from European integration. Their statements revealed an underlying insecurity about the future of the relation of Poland with the EU and how this potentially affects their own future. In other words, some of the sampled women expected the ruling party to deprive them from what they have attained at the European level.

I then asked the students about their view on national traditions and contexts. The students’ statements made clear that while the young generation is seemingly faced with an ideological and institutional Europeanisation with more opportunities, old boundaries are still in place, while new boundaries emerge and need to be debated and negotiated (Cichocki, Reference Cichocki2011). Many students distinguished between the ‘East’ (Poland) and the ‘West’ (the EU) (JH, F, Warsaw) and mentioned that they sometimes feel as if they are still not fully accepted EU members. Another cleavage that emerged was the election of PiS that seemingly affected the social cohesion and gender equality in Poland. The students described how the Polish nation became divided again over citizens’ affiliations and opinions of PiS. One student summarised: ‘We are really fighting each other’ (JA, M, Warsaw). Poland’s ruling party became popular, most importantly because of its social welfare programmes, its defence of traditional values and national identity, and its stance against the EU’s involvement in Poland’s internal affairs (Szczerbiak, Reference Szczerbiak2015). In contrast to the party’s ideology, the interviewees displayed rather liberal and egalitarian views but also criticised their own inactivity to change things. As one female student mentioned: ‘When PiS was elected, it was a shock for most young people. You know what’s the problem? Young people are not going to vote and older people go because they feel that it is important’ (MPo, F, Wa).

Predominately, female students mentioned that Poland’s EU membership was also important regarding matters of security and protection from Russian threats and political influence. The feeling of belonging to a larger community that offers protection against any potential Russian threat offered a relief and demonstrates that the collective memory among young adults about the past Soviet occupation is still vivid. As one student put it: ‘I feel safer if I know that we are in the EU instead of being on our own. Because even if Russia threatens us like they did in the past, I can have this little hope that somebody helps us if they someday attack us. I don’t trust Russia. I have this in my blood’ (AS, F, Tricity).

Another aspect reflecting national traditions is the central role of the family and relatives. Within my sample, many of the interviewed women emphasised that they want to benefit from EU integration but were somewhat restricted by the loyalty to their family and want to return to Poland after spending time abroad and pursuing their career. This attitude illustrates both a move away from traditional family models and the continued fundamental importance of the family as a stable social network that the interviewed women did not want to leave behind.

Discussion

I examine the relation of gender to attitudes towards the EU and perceived personal benefits from European integration among a sample of well-educated men and women in Poland. The key findings of this study paper are the following: The quantitative analysis of the sampled group of winners of European integration (Kriesi et al., Reference Kriesi, Grande, Lachat, Dolezal, Bornschier and Frei2008) reveals higher support for European integration among this group than among the citizens in Poland (EB/EP 88.1, 2017). There are also notable differences between men and women. Only 54.8% of all surveyed men have favourable attitudes towards the EU while 76.1% of the surveyed women supported European integration. These results show that contrary to previous findings (Schlenker, Reference Schlenker2012), within the group of sampled students, gender has an effect on attitudes towards the EU if we look at a group of people of the same age and education level. The data also confirm the assumption that objective sociodemographic characteristics, which indicate personal benefits from European integration, are positively associated with attitudes towards European integration among both genders (Pichler, Reference Pichler2009a, Reference Pichler2009b). Interestingly, the correlation between these two variables is slightly higher among men than women. These findings therefore demonstrate that characteristics such as age, education, and place of residence are important but not sufficient to assess winners of European integration and to explain their opinion about European integration (Liebert, Reference Liebert1999; Torres and Brites, Reference Torres and Brites2006). Gender-related aspects play a role in the perception of European integration and personal benefits resulting from Poland’s EU membership (Noe, Reference Noe2016).

The qualitative results help explain the factors that influence these well-educated young people in their assessment of European integration and personal benefits. Structured along three theoretical approaches – political interests, economic utilitarian drivers, and national traditions – the interviewees’ statements reveal gendered insights in development of attitudes towards the EU. Yet, these theoretical approaches cannot always be separated and often influence each other. For example, based on the country’s communist past, predominately female students mentioned that they are happy to belong to a larger community that offers protection against any renewed potential Russian threat. As one student said: ‘For me, it’s good to be an EU member because of the politics of Russia. If the EU would fall apart, for me it would be very scary. For Poland, it’s a matter of security’ (AM, F, Kraków).

The statements of the sampled cohort illustrate the influence of national traditions and contexts on the nature of personal benefits and they also contradict previous research that assumes women to be less interested in European politics (Inglehart, Reference Inglehart1970; Liebert Reference Liebert1997; Nelsen and Guth Reference Nelsen and Guth2000). Men and women in my sample were equally critical and informed about local as well as national politics and certain aspects of Poland’s EU membership. This fact would confirm the assumption that education is an important factor in gaining better political knowledge and may not come as a surprise since all participants in my study are young and highly educated (Gabel, Reference Gabel1998; Nelsen and Guth, Reference Nelsen and Guth2000). According to the Eurobarometer, older and less educated people state less often that they understand how the EU works (EB 88, 2017b). Additionally, following the dispute between the EU and Poland over democratic values, some of the female participants mentioned that they became interested precisely because they realised how much is at stake for them.

For most interviewed students, the EU offered benefits in terms of free movement and personal career opportunities. While they critically assess the influence of EU membership on Poland, the majority emphasised personal advantages resulting from Poland’s EU membership. Their individual idealisation of the West with simultaneous critical recognition of European integration (Sztompka, Reference Sztompka2004) often surfaced when they described local economic conditions and individual future perspectives. Utilitarian reasons, such as job opportunities and higher salaries abroad, serve as drivers for their support for integration but women also mentioned post-material factors, such as quality of life and intellectual fulfilment. Many of them had clear plans how they want to benefit after graduating. These plans often included transnational relocation to spend some time abroad in a specific country of their choice. This points towards an empowering factor of mobility as an important tool to improve social capital and personal innovation (Morokvasic, Reference Morokvasic2004). With access to the European network and growing up in urban conditions with better economic stability and more equality, highly skilled women are in a good position to move away from expected traditional behaviour and to focus on their own needs and post-materialist aspirations (Inglehart, Reference Inglehart1990).

Unlike in previous research (Mau, Reference Mau2005; Vitores, Reference Vitores2015), the well-educated young women in my sample did not feel that European integration would lead to higher personal costs. Besides their educational background, age, and place of living, the reason for the absence of feelings of vulnerability could be twofold. First, none of the interviewed women had children and most of them were still living at home. This situation means they did not feel vulnerable (Vitores, Reference Vitores2015), nor were they overly reliant on the welfare state (Mau, Reference Mau2005: 300), nor restricted by motherhood (Siara, Reference Siara2013). Second, their biggest concern was the actions and the Eurosceptic rhetoric of the ruling Law and Justice party. Predominately, women considered the current situation as unfavourable, both for their own opportunities and for the Polish society. This is an interesting finding because in contrast to Liebert’s (Reference Liebert1997) study, the interviewed women used opportunities resulting from EU membership as a frame of reference to assess impacts deriving from national politics. There is a negative discrepancy between the sampled women’s current position as winners of European integration with assumed personal future gains, and the position they are expected to be according to values promoted by political and religious institutions in Poland. Fears of relative deprivation (Liebert, Reference Liebert1997) originated rather from conservative national politics and policies of re-traditionalisation (Siara, Reference Siara2013) than European unification.

These results, however, may differ if we look at less educated and older Polish citizens. According to the Eurobarometer (EB 88, 2017b), freedom of movement and work in the EU are much less important for Polish citizens with lower education levels (29%), compared to citizens with high education (74%). Similarly, only 54 % of Polish citizens of 55 years and older argued that the opportunity to work everywhere is important, compared to 64% among people between 15 and 24 years old. These sociodemographic indicators are important but place also matters in terms of social compositions and values (White et al., Reference White, Grabowska, Kaczmarczyk and Slany2018). There is a perception of a cultural divide between Eastern and Western Poland, with Eastern Poland being more rural, more underdeveloped, and more conservative. In this region, catholic norms and conservative family values are more deeply engrained than in the cosmopolitan cultural centres, such as the bigger cities in Western Poland.

The results of this study demonstrate the complex history and national traditions in current Poland. Young well-educated urban residents are confronted with an array of historical narratives, political conflicts, and socioeconomic changes. The collapse of communism in 1989–1990 and Poland’s EU membership in 2004 brought an entirely new situation in which strong external and domestic forces started to exert their influence. Multiple frames of reference contextualise the ways in which the young interviewees experience all aspects of social life and how they plan their future. They are faced with a communist past and a still ingrained fear of Russian influence. Combined, these views contributed to the students’ self-description of being European but at the same time feeling apprehended by the West as being ‘other than Europe’ (JH, F, Warsaw).

Domestically, they are affected by a political milieu that continues to promote a conservative ideology (Fomina and Kucharczyk, Reference Fomina and Kucharczyk2016). Although not explicitly mentioned by the interviewees, the Church in Poland plays ‘a fundamental role in the development of Polish national history and domestic politics’ (Guerra, Reference Guerra2016: 40). Catholicism may not be the determinant factor for Euroscepticism in Poland, but it could become a source for negative attitudes towards the EU by influencing the narrative on national values. The notion of a specific national identity, including freedom from the communist regime, can overlap with conservative norms promoted by the ruling party PiS. In their study Balcer et al. (Reference Balcer, Buras, Gromadzki and Smolar2017) note that in recent years, many young people in Poland have turned towards these conservative values and often vote for nationalist parties because they stand for more economic security and national self-determination. Over 48% of voters aged 60 years and older chose PiS but equally, two-thirds of voters between 18 and 29 yearssupported one of the parties to the right of the centre in the 2015 parliamentary elections (WP, 2015). This voting behaviour stands in contrast to the modern gender theory put forward by Shorrocks (Reference Shorrocks2018) and contradicts the findings about political preferences voiced by the sampled well-educated cohort in this study and deserves further research.

Around 80% of Polish citizens state that the family is the most important thing to them (Grabowska, Reference Grabowska2013), which may restrict young people’s ambitions. White (Reference White2010) argues that young Polish people often perceive the possibility of free movement as an escape from restrictive expectations, providing them with an opportunity to be independent of parents. This position was also mentioned by the sampled students but individually, feelings of attachment and the moral obligation to be close to the family restrict the agency of some of the sampled individuals, and predominantly women. However, my findings confirm that open borders, cultural exchanges, liberal values, and individualism increasingly compete with conservative views and traditional gender models at home (Slany, Reference Slany, White, Grabowska, Kaczmarczyk and Slany2018) and are likely to lead to social changes among the interviewed young, well-educated Poles (Siara, Reference Siara2013). This increasing outward orientation and the unfavourable assessment of the political climate in Poland could be one of the reasons why many young Poles talk about politics but are often reluctant to involve themselves personally (Jakubowska and Kaniasty, Reference Jakubowska and Kaniasty2015). Having the opportunity to move freely, they rather vote with their feet and leave.

Conclusion

In this mixed-methods study, I investigated if a sample of well-educated young women and men living in Polish cities differ in their attitudes towards the EU. I hypothesised that the gender gap might play less of a role among the surveyed winners of European integration. On the basis of the analysis presented in this article, I can confirm that there are more similarities than differences between these well-educated young men and women. Indeed, education may alleviate assumed gender gaps but that does not mean that well-educated men and women support integration based on the same factors and share the same experiences. The quantitative part of my study shows that female students have more positive attitudes towards the EU and see more personal advantages resulting from Poland’s EU membership. Looking at the factors for EU support, the qualitative part shows certain similarities but also interesting disparities in personal assessments of European integration and resulting benefits. Many of the interviewed students showed equal interest in local, national, and European politics but women were more often concerned with the current conservative political climate in Poland and its consequences for the country’s image in Europe and the effect on liberal values. Interviewees were also aware of the benefits they could receive from EU integration, but women included both, economic and noneconomic advantages. Regarding national traditions and contexts, women in Poland are faced with greater opportunities, old boundaries, newly emerging political cleavages, and traditional values. More specifically, EU membership is important for the sampled women’s empowerment but many of them find it difficult to cope with long-established stereotypes by West Europeans vis-à-vis post-communist countries. They are also more affected by the nationalist rhetoric and conservative policies of the ruling Law and Justice party, and personal restrictions because of strong loyalty towards their family.

These findings, although not generalisable, contribute to shed light on new aspects of post-communist transitions and gendered attitudes towards the EU among well-educated urban citizens. I suggest that gender deserves more attention and academic investigation as an explanatory variable that offers nuanced insights into attitudes towards the EU within post-communist societies. Further research such as comparative multilevel analyses and a different sampling method would be promising to put the findings of this case study in perspective and to provide results that are more generalisable than this sample of well-educated, urban men and women.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1755773919000304

Acknowledgements

I want to thank the students who gave me their time and filled out the questionnaire, and who allowed me to interview them. I also want to express my gratitude to the academics, working at various universities in Poland, who allowed me to come to their classes to conduct my research.