Introduction

Does supranational identity have an independent effect on individuals’ beliefs about culturally contested issues in their national systems? Until recently, social and cultural issues were exclusively the domain of domestic contestation among political parties. With the expansion of the EU’s agenda, however, the EU is ‘increasingly perceived by a number of actors as unduly intervening in matters where not only social preferences but, more fundamentally, value systems are at stake’ (Leconte, Reference Leconte2008). A new dimension of political contestation has emerged whose most visible manifestation is the discourse over immigration and multiculturalism, but can also be discerned in attitudes toward gay rights and gender equality. Parties’ positions on this issue cleavage have been shown to be a good predictor of their positioning on European integration (Hooghe et al., Reference Hooghe, Marks and Wilson2002; Kriesi, Reference Kriesi2007). Less is known, however, about how social and normative preferences at the individual level interact with deep-rooted identifications with the nation-state or Europe.

Previous work on supranational identification has vastly focused on the role of identity in shaping attitudes toward the European Union (EU) and EU-related issues (McLaren, Reference Mclaren2004). The interplay between identity and utilitarian factors in determining support for European integration, however, is not the only consequential manifestation of the effects of supranational identification. Kennedy (Reference Kennedy2010, Reference Kennedy2013) demonstrates that supranational identity shapes individuals’ behavior in their domestic political systems as well and is associated with higher levels of political efficacy, political participation, and support for democracy. This paper extends the research agenda on supranational identity by integrating the new value-based dimension of contestation and theorizing that identification with Europe affects citizens’ views on social issues such as lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) rights and the role of women in society.

Empirically, we use the European Values Study (EVS) to examine whether supranational identity is associated with socially liberal preferences. Results from the multi-level models indicate that supranational identity exerts a systematic effect on attitudes toward both gay rights and gender equality. Additionally, while these effects are more consistent in EU member states, supranational identity exhibits a similar impact on social attitudes in non-member countries such as those in the former Soviet Union.

The study contributes to our understanding of how identities work by demonstrating that self-categorization in the supranational realm – a seemingly unrelated category to domestic value cleavages – has implications for individuals’ views on culturally contested domestic issues. Traditional theories of international norm diffusion focus almost exclusively on state-level interactions, but our findings provide further evidence to the existence of a more direct mechanism through which norms reach some citizens. A sense of identification with a supranational entity, such as Europe, makes citizens more likely to espouse the views and opinions promoted by Europe’s most visible supranational body – the EU. This is also encouraging news for the ability of the EU to promote social change and opinion shifts on matters where it does not possess specific legal powers. Informal perceptions of what constitutes appropriate behavior for an individual with a supranational identity can provide a direct channel to some EU citizens, and perhaps even more importantly, they can reach non-EU citizens in countries with distant or non-existent prospects of membership over whose governments the EU has little formal leverage.

Supranational identity and value-based domestic cleavages

The concept of identity in its various manifestations has been the subject of study in an array of social science disciplines such as psychology, political science, and sociology. Group-based social identities are of particular interest to scholars of political psychology as they provide insights into people’s motivations and behavior in the socio-political realm. Social identity of this type refers to a person’s perception of being a part of a certain group(s) and placing value and emotional significance on membership in this shared category (Hogg and Turner, Reference Hogg and Turner1987; Brewer, Reference Brewer1993; Brewer and Gardner, Reference Brewer and Gardner1996; Greene, Reference Green2002). This self-categorization into a social group then creates certain norms and expectations about behavior and forges a bond between members of the ‘in-group’.

Social identities based on group membership can be built around very well-defined and clear categories such as gender, race, political identification, citizenship. The majority of research in political science has focused on the implications of such well-defined social identities for individuals’ behavior and their attitudes toward ‘out-groups’ to which an individual does not belong. Partisanship, the most common form of political identification, has often been conceptualized as a type of social identity where partisans develop a strong emotional and social bond with their party even when their views are not perfectly aligned with official party positions (Converse and Dupeux, Reference Converse and Dupeux1962; Campbell et al., Reference Campbell, Converse, Miller and Stokes1964; Converse, Reference Converse1964; Greene, Reference Green2002). Similarly, ideological identity has recently been established as a type of political identity (Malka and Lelkes, Reference Malka and Lelkes2010). Related research agendas have demonstrated that strong identification with a given group often contributes to negative attitudes and/or discrimination against perceived out-groups (Sears and Funk, Reference Sears and Funk1990; Smith et al., Reference Smith, Spears and Oyen1994; McLaren, Reference Mclaren2004).

Some social group categories, however, are much more diffuse and lack clear distinction lines. Supranational identity falls into that category as its literal meaning of identifying beyond the nation encompasses a very broad ‘in-group’, which cannot be juxtaposed to a clearly defined out-group. Recent studies have revealed that self-categorization in such ‘minimal groups’ can still generate a sense of belonging and even have a greater influence on individuals’ political and social behaviors than membership in social groups with well-defined boundaries (Hymans, Reference Hymans2002; Monroe and McDermott, Reference Monroe and Mcdermott2010). Experiments using this approach have revealed that even arbitrary and virtually meaningless randomly assigned distinctions between groups can trigger a tendency to favor one’s own group and its rules of behavior (Tajfel, Reference Tajfel1970). In political science research, scholars have begun to examine the role of reputational pressures and social norms for state behavior in the international realm. Yet, the individual-level implications of perceiving oneself as a member of supranational minimal groups such as the ‘club of democracies’ or the ‘East’ vs. ‘West’ in the European context have not yet been investigated. A person’s self-categorization with supranational bodies can have far-reaching implications, which are currently not well-understood.

Rather than studying supranational identity as an explanatory factor for domestic political attitudes, the vast majority of previous research into supranational identity comes from the study of Euroscepticism and related EU attitudes. Studies consistently find that identity-based factors such as exclusive national identity and opposition to multiculturalism are among the main drivers of opposition to European integration (McLaren, Reference Mclaren2004; Hooghe and Marks, Reference Hooghe and Marks2005; Vreese and Boomgaarden, Reference Vreese and Boomgaarden2005; Cutts et al., Reference Cutts, Ford and Goodwin2011). The consequences of high supranational identification for non-EU related attitudes have, however, not been sufficiently examined.

Supranational identification can provide a mechanism through which international norms reach citizens directly rather than through national governments. The diffusion of norms and behaviors promoted by supranational bodies such as the EU is viewed primarily through the prism of international relations theories where mass attitudes and orientations are largely missing from the causal models. Liberal institutional theory and constructivist theories both argue that supranational institutions and powerful states create incentives as well as constraints on the behavior of other states. Thus, the policy choices as well as the discourse of the national government changes first in order to receive the benefit or to avoid the reprimand. However, over time the norms become accepted and internalized. Some examples of such norm diffusion can be seen in the diffusion and acceptance of the human rights regime with the help of the United Nations. In the case of Europe, more attention has recently been paid to the process of Europeanization or the dissemination of standardized policies, regulations, and values throughout member states, old and new (Goetz and Hix, Reference Goetz and Hix2001; Olson, Reference Olson2002; Schimmelfennig, Reference Schimmelfennig2003; Schimmelfennig and Sedelmeier, Reference Schimmelfennig and Sedelmeier2005; Schimmelfennig et al., Reference Schimmelfennig, Engert and Knobel2006).

The causal mechanism in the aforementioned theories of international norm promotion often runs from a supranational body to national governments and eventually the socialization of citizens into the new norm is assumed. While this mechanism is highly plausible, it tells only part of the story. A direct link between supranational norm diffusion and individual citizens remains unexplored in policy diffusion models. Such direct links between individuals’ self-categorization into a supranational identity and the adoption of associated norms and behaviors would explain why sometimes shifts in citizens’ opinions precede shifts in government policy. Moreover, norm diffusion from supranational bodies directly to citizens may be becoming more frequent with the development of mass communication technologies that provide a widely available platform to disseminate and access information.

Recent work by Kennedy (Reference Kennedy2010, Reference Kennedy2013) has laid the ground for examining how self-categorization in the international context can affect domestic attitudes and behavior. His findings demonstrate that citizens with a higher level of supranational identification exhibit greater support for democracy, greater political efficacy at the national and local level and greater interest and participation in political affairs. These results are encouraging for the ability of international bodies to promote democratic practices by directly influencing citizen attitudes, rather than by working exclusively through national governmental institutions as intermediaries.

Taking Kennedy’s findings even further, we argue that supranational identity has the potential to affect individuals’ views on morally contested issues, which are sometimes considered more divisive and emotionally charged than traditional political debates. These new issues, where value priorities and ingrained cultural norms are often at stake, include women’s rights, the rights of sexual minorities, reproductive rights, civil liberties, and inter-ethnic relations (Inglehart, Reference Inglehart1977; Dalton, Reference Dalton1996). While traditional cleavages formed around socio-economic lines remain, they now co-exist with value-cleavages of different types and intensity in virtually all democratic countries around the world. Examining whether and how self-categorization in the international context affects individuals’ views on such value-based ‘new politics’ issues will serve to assess the explanatory power or limits of supranational identification as a form of minimal-group social identity.

The EU and new value cleavages

The new role of the EU as a forum for discussion and resolution in the highly contested area of moral issues has been recognized by practitioners and academics alike. The regulations and provisions adopted by EU treaties, the policies of the supranational Commission and European Court of Justice, as well as the deliberations and actions of the European Parliament seem to suggests that the EU has ventured into the territory of highly disputed ‘new value cleavages’ including issues such as gay rights, abortion, stem cell research, and the promotion of multiculturalism (Leconte, Reference Leconte2008). What is more, the EU seems to be espousing and promoting politically liberal norms on these highly contested issues even if not always in the form of official regulations. European integration has evolved from a largely economic enterprise to a point where it demands ‘of each individual, as well as of society as a whole, a high level of tolerance’, when such morally and culturally contested matters are concerned (Weiler, Reference Weiler2002).

Here we focus on two such issues – gender equality and LGBT rights. Both of these issues can be seen as challenging the traditional morality of societies and therefore have historically been under the purview of domestic politics. However, the EU has gradually taken steps toward regulation of these arenas. Since the adoption of the Treaty of Lisbon and with it the Charter of Fundamental Rights, the supranational institutions of the EU have been venturing into areas traditionally outside of their competence.

A legal framework for battling workplace discrimination on the basis of gender or sexual orientation has been steadily developing in Europe. Under the provisions of the Treaty on the Functioning of the EU, the Maastricht Treaty and the Treaty of Amsterdam the provisions against discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation have been laid out. The Charter of Fundamental Rights, which was fully legalized by the Treaty of Lisbon in 2009, makes the legal protection of the LGBT community applicable and binding to all member states. The ECJ has made several rulings chastising the member states for their violations against homosexual citizens. Despite these legal advances, protection of gay rights at the EU level is still in its developmental stages, but less formal channels of norm promotion have been quite active. The European Parliament, and more specifically the Intergroup on LGBT Rights, has served as a watchdog and a forum for advancement of anti-discrimination policies and practices.

The anti-discrimination provisions based on gender differences on the other hand are much more extensive and date back to the Treaty of Rome. The EU has been active in eradication of gender inequality in the work-place and advancing women’s participation in decision making by adopting a three-prong approach to gender inequality. These include equal treatment legislation, gender mainstreaming – incorporating gender perspectives into all policies – and adopting policies for advancement of women (http://ec.europa.eu/justice/gender-equality/). The commission finances specific programs for eradication of gender inequality such as PROGRESS and Daphne III. Additionally, the EU continues to supervise and advance gender equality through more informal channels such as the European Institute for Gender.

As a first test of the link between supranational identity and new politics issues, therefore, we focus on support for gay rights and gender equality. We chose to focus on these issues due to their prevalence and importance in all societies of today’s Europe and, perhaps even more importantly, due to the variation they provide. These issues vary in terms of their divisiveness, visibility, and level of legalization. LGBT rights are more contested and less legalized in all parts of Europe. Even in the established democracies of the ‘old EU-15’, the debates regarding the social and political equality of LGBT citizens are highly contentious. Mass protests in France over the 2013 legalization of same-sex marriage highlight the contentious nature of this issue. Gender equality, on the other hand, while still far from resolved, causes much less societal division. Moreover, as becomes apparent from the brief description above, there is variation in terms of the visibility of EU activity regarding these issues. Gender policies and regulations are much more numerous, older, more legalized at the EU level and are more extensive in terms of issue coverage. On the other hand, policies dealing with the support and promotion of LGBT rights and non-discrimination are less-formally developed, albeit growing.

Thus, we chose to focus on these two issues to ensure that our analysis is broader in scope instead of confined to either the high or low ends of the contestation spectrum. While the interrelated questions of immigration and multiculturalism, for example, represent another important and highly contentious ‘new politics’ issue in Europe’s current social and political environment, the initial test of our theory is better served by including a less contested type of issue such as gender equality. Is the effect of supranational identity on cultural attitudes present for highly contentious issues such as LGBT rights, or is its scope confined to fairly consensual and more legally formalized issues such as gender equality? Given the scarcity of previous research on the matter, allowing for a comparison between the effects of supranational identity on more contentious vs. less contentious cultural issues, would enable more useful insights about the scope of our theory.

In addition, the advancement of both LGBT rights and gender equality is most commonly framed as a question of ‘equal rights’ in the discourse of social movements, institutions, and activists – while evoking utilitarian considerations is not a common strategy. In the case of immigration, on the other hand, utilitarian narratives are frequently used by activists or political actors, thus making the distinction between identity-driven and instrumental attitudes toward multiculturalism difficult to establish without experimental data. As a first test of a theory linking supranational identity and cultural attitudes, therefore, we chose cases where the proposed causal mechanism can be more reliably tested with the available cross-sectional data.

Finally, it should be noted that, while the EU is the most visible supranational body actively involved in national politics, this is not a study of support for the EU. While supranational identification often involves support for European Integration as a whole, when it comes to gender equality and gay rights, there are a number of European and international organizations (such as UNESCO, OECD, Council of Europe among many others), as well as transnational NGO networks, involved in promoting fair policies and value change. Thus, we do not define supranational identification as a feeling of belonging or attachment to the EU, but as identification with ‘Europe’ as a whole. Whether for an individual ‘Europe’ is a broader concept involving a community of nations or perceived as synonymous to the EU is of no relevance to our analysis since both interpretations presuppose a level of supranational identification. Additionally, we allow for an even higher level of supranational attachment by including citizens with the most cosmopolitan outlook who view themselves as global citizens rather than self-identifying primarily with their nation-state or Europe.

The theoretical conceptualization of identity in our study is, therefore, not dichotomous and not bound to the EU as an institution. In the practical world of European politics, however, it is rarely contested that it is the EU, of all the supranational actors, that has the most direct influence on domestic policies and the most opportunities for softer norm promotion in the non-EU member states through association agreements and cooperation initiatives. In the national media of both members and non-members of the EU it is thus primarily the EU and its regional bodies that are the most visible and hence the most likely to be associated by citizens with the particular values and norms promoted by all international organizations active in Europe. For these purposes, the majority of examples provided in this section serve to illustrate actions taken by the EU in promoting LGBT rights and gender equality – if Europeans with higher levels of supranational identification are indeed more likely to support liberal cultural norms promoted by supranational organizations, the EU would be the most likely supranational reference point associated with such norm promotion.

Supranational identity and regional differences

As identities do not exist in isolation and the majority of people have multiple identities, it is worth noting that the relationship between supranational identification and social preferences may likely be mediated by national context. For example, in the old EU member states Europeanization-induced standardization of policies in a variety of issue-areas may possibly have had enough time to spill over into greater standardization of norms and values. Post-communist states in Europe, however, have had fewer years of experience with liberal democracy and many of them have relatively more traditionalistic cultures. Individuals accustomed to such national contexts can perceive Brussels as imposing new norms of morality in their societies. Despite formally adopting certain legal protections in order to comply with accession pressures, new EU member states experienced a political backlash against these new norms which, at least temporarily, worsened the situation of the LGBT population (O’Dwyer, Reference O’Dwyer2012). Recent controversies surrounding gay pride parades and feminist groups in post-communist states are a manifestation of this pattern. With greater public contestation over the value dimension in Eastern Europe, therefore, the relationship between the presence or absence of a supranational identity and social preferences may be less pronounced than in the West.

In addition to possible differences between new and old EU member states, we consider non-EU members as well. While supranational identity in Europe is almost exclusively studied in the context of EU members or candidate states, it is precisely its potential effects in the remaining European states that may possess the greatest implication. As supranational organizations like the EU and the Council of Europe have little formal leverage outside the realm of EU members and hopefuls, supranational identity provides a way to reach citizens without going through government channels. Figure 1 shows that, in fact, there is very little variation among European nations in average levels of supranational identification, with non-members even exhibiting slightly higher averages than recent EU member states from Central and East Europe.

Figure 1 Supranational identity across Europe.

Including non-EU countries – the post-Soviet ones, in particular – serves another important purpose. Testing the link between supranational identity and cultural attitudes in countries, which currently have no prospects of EU membership and few formal ties to supranational organizations in Europe, would lend support to our posited identity-based causal mechanism as opposed to more instrumental motivations linked to perceived benefits derived from EU membership.

The strategies and discourse used by transnational advocacy movements themselves, further lend support to our expectations that supranational identity affects cultural value cleavages since both the EU and transnational advocacy networks have created a narrative of common European rights and norms. Europeanization has provided ample opportunities for transnational LGBT activists, for example, to mobilize across borders and, when seeking domestic support, they have frequently framed the issue of LGBT rights as an ‘inevitable process associated with “European” standards of acceptability’ (Ayoub, Reference Ayoub2013). Transnational activists, if faced with hostile-to-their-cause national governments, can use EU actors and EU norms on LGBT rights as allies in their lobbying efforts. Moreover, charting a common European narrative that ties LGBT rights to the protection and promotion of general human rights, is often perceived to increase the persuasive power of LGBT arguments when seeking to garner public support.

While the opportunities provided by the EU affect mobilizational tactics at all levels of advocacy activism (della Porta and Caiani, Reference della Porta and Caiani2007), its active role has also afforded domestic opposition movements the opportunity to frame the LGBT movement as sponsored by external forces who threaten national cultural values (Ayoub, Reference Ayoub2014). This opposition frame, effectively combining nationalistic overtones with support for conservative values, is particularly strong in post-Soviet non-EU countries, which makes them a valuable addition to our empirical analysis. The presence of identity cleavages in the absence of EU membership conditionality presents a convincing case for an identity-based causal mechanism as opposed to instrumental motivations.

If regional differences do indeed matter, socialization arguments would posit that supranational identity will have a more pronounced effect in countries with greater experience of European integration than in those where value cleavages have only recently come to the surface and have more overtly clashed with EU-promoted norms about appropriate policies and behavior. Strong opinions on such deeply divisive cultural issues may override the effects of supranational identity. On the other hand, if minimal groups theory holds in the case of supranational identity, then those who identify with Europe will nonetheless exhibit more liberal views on such matters. Recent studies have revealed a surprisingly strong influence of thin identifications such as a ‘club of democracies’ for individuals’ behavior (Hymans, Reference Hymans2002). Therefore, a systematic relationship between supranational identity and associated values may work in a similar manner irrespective of national variation in historical experiences and degrees of contestation over value cleavages.

To sum up our expectations, first we propose that higher levels of supranational identification among European citizens will result in more positive attitudes toward homosexuals and support for LGBT rights. Second, greater supranational identification will result in more liberal attitudes toward the role of women in society and higher support for gender equality. Third, longer experience with EU integration will result in greater socialization into conforming to supranational norms and hence greater support for both LGBT rights and gender equality.

Data and methods

The empirical analysis of our hypotheses relies on cross-national multilevel analysis of data from the EVS. The EVS data provides us with an opportunity to analyze the effects of supranational identity on domestic issues of social equality, cross-nationally in over 40 countries. It is particularly suitable for examining whether direct experience with Europe affects the connection between supranational identity and domestic values positions. As stated in the theoretical section, our analysis will include all EU member states, but also non-EU countries in Europe such as the former Soviet states and the Western Balkans.

The 2008 wave of EVS survey data covers an array of questions dealing with our two main dependent variables – respondents’ attitudes toward social, economic, and political rights of homosexual persons and women. As such, we create several composite variables by compiling additive indexes of related questions. The three questions dealing with approval of homosexuality in general, rights of homosexual couples to adopt children, and respondents’ reluctance to have homosexual persons as their neighbors, exhibit sufficient correlation and have thus been rescaled and indexed into a single variable. Higher scores on this index indicate greater acceptance of homosexuality and support for gay rights.

On the issues of women’s rights we identified seven related variables and, via the use of factor analysis, separated these into two distinct measures tapping into two separate dimensions of women’s place in society. The first measure of women’s rights deals with social perceptions of women’s traditional roles such as the importance of children and family in a woman’s life. This index includes questions like, a woman’s need to have children in order to be fulfilled, the perception of woman’s fulfillment with being a housewife, unsuitability of a single woman to raise a family, and disapproval of abortion for a single woman. The second variable taps more into work-related issues and the balance between family and career. This variable is comprises three related questions. Gainful employment as essential to woman’s independence, the perception of a working mother’s ability to have a good relationship with her children, and the equal responsibility of the male partner in raising the family are combined in this second measure. Higher scores on each of the indexes indicate more liberal attitudes on women’s issues and higher support for gender equality.

Our main independent variable is supranational identity of European citizens. This variable comes from EVS survey questions, which ask the respondents to identify which geographic locality s/he belongs to first and second. Locality or town, region, nation, Europe, and the whole world are given as options in both cases. We combine these two questions and create a composite variable (1–3) where higher values indicate greater supranational identity. Respondents who mentioned Europe or the world as their first identification are classified as having high levels of supranational identification; respondents who mentioned Europe or the world as their second most preferred identification were classified as having moderate levels of supranational identification and those who mentioned neither Europe nor the world as their top two identifications were classified as low on this variable.

We employ several individual-level control variables. Sex, age, gender, education, and political ideology are all used in our models since both demographic cleavages and political convictions are frequent sources of attitude formation. We also control for the religiosity of the individual respondents by creating another composite variable, which taps into the individuals’ belief in God and frequency of attending religious services. These two variables give an inclusive representation of a person’s belief in higher power and his/her relationship to the established institutions of organized religions. The literature on religious perspectives of individuals has long established that the true religious cleavage runs between those who follow religious doctrines and attend religious services regularly and those who do not, in short practicing and secular members of the society (Lijphart, Reference Lijphart1979; Lewis-Beck, Reference Lewis-Beck1986; Layman, Reference Layman1997; Inglehart and Norris, Reference Iinglehart and Norris2003). Lastly, in our models we include an index of materialist and post-materialist values to control for broader cultural context. The variable has three categories – materialist, mixed, and post-materialist orientations based on the standard battery of four questions.

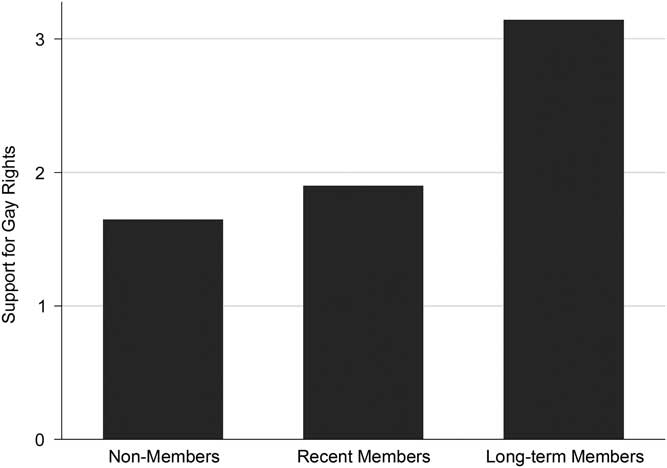

In addition to individual-level controls, we introduce three country-level variables, which account for specificities of socio-economic and political realities of European societies. As mentioned above, we make a distinction between member and non-member states of the EU. Moreover, we distinguish between the ‘old’ EU-15 and new member states. The distinction is a crude measure aimed to capture the degree of ‘Europeanization’ of domestic societies and runs from 1 to 3 where 1 equals non-member state, 2 equals new member state (joined the EU in 2005 or 2007) and 3 equals ‘old’ member states (joined the EU prior to 2005). Figures 2–4 provide some basic information on the degree of variation in our dependent variables among the three groups of states. We see that there are indeed substantial differences with respect to the more controversial issue of gay rights. Non-members have almost twice lower levels of support than long-term EU members, with the recently joined CEE countries falling in between. There is much less country variation in average levels of support for gender equality by degree of Europeanization. Figure 3 – where gender equality is represented by our index of approval for non-traditional roles for women – shows minor regional differences with more Europeanized countries having a slightly higher proportion of liberal attitudes. Figure 4 – where gender equality is represented by our index of gender equality in more career-related aspects – shows basically no variation by region.

Figure 2 Support for gay rights by EU membership status.

Figure 3 Support for gender equality (non-traditional roles for women) by EU membership status.

Figure 4 Support for gender equality (career-related aspects) by EU membership status.

The other country-level variables we use in our model are the Human Development Index (HDI) and democracy scores by Polity. HDI is a score calculated by the United Nations Development Program, which takes into account each country’s aggregate levels of education, life expectancy, and income adjusted for inequality. Polity score is based on a scale of −10 to +10 and represents regimes ranging from authoritarianism to consolidated democracy. Since the fieldwork for the survey was conducted between 2008 and 2010, we use average scores over those 3 years per country for both the HDI and Policy scores. Both of these measures tend to have very low variation per country in proximal years, which makes the 2008–2009–2010 average score a reliable measure for country context. We expect that these variables should have a positive effect on attitudes toward LGBT and women’s rights.

We employ two-level models with individuals nested within countries to account for possible country-level variation. All explanatory variables have been centered for more intuitive interpretation. Coefficients in the resulting models can thus be interpreted as the effect of a given variable with all other variables held at their means.

Results

The results of the multilevel models consistently support our first two hypotheses. Table 1 presents the results of the multilevel models where the dependent variable is our index of support for LGBT rights. The first column consists of findings from a random intercept model. This model assumes consistent slopes across each country while allowing the intercept to vary. Looking at the variances, a variance partition coefficient of 0.32 indicates that 32% of the variance in support for gay rights can be attributed to differences between countries, while the remaining variance to differences among individuals. Our key independent variable of supranational identity is indeed significant and in the expected direction. A one unit increase in supranational identity results in 0.13 increase in support for gay rights. The magnitude of the effect is very similar to that of education, age, and religiosity; and notably larger than that of left–right ideology. At the country level, democracy scores appear to have no significant relationship with attitudes toward homosexuals. While this is indeed surprising, it should be noted that a large portion of the countries in our sample are clustered at the high end of democracy scores with ~81% of observations having a democracy score higher than 7. The HDI on the other hand proves to be an important predictor. A one unit increase in HDI results in 0.6 increase in support for gay rights. Again, a clarification should be made that HDI is a continuous variable that assumes values between 0 and 1 and even minor changes in the index historically take a long time. For example, it took 20 years for the highly developed countries to move from 0.605 to 0.695 in their HDI scores between 1980 and 2000. Thus, HDI results in our models, while important, should be considered in context of the slow-changing nature of a country’s HDI.

Table 1 Multilevel OLS regression predicting support for gay rights

RI=random intercept; RS=random slope.

Standard errors in parentheses.

Boldfaced coefficients significant at P<0.01. LR test vs. linear regression: χ 2 (3)=1681.73, Prob>χ 2=0.00.

In the second model in Table 1, we allow for the possibility that the effect of supranational identity varies across countries. Thus, a random slope for the supranational identity variable is included. Results remain very similar with a one unit increase in supranational identification resulting in 0.13 increase in one’s support for gay rights. Less religious, younger, more educated, more left-wing, and more postmaterialist individuals are also more likely to exhibit more liberal attitudes toward homosexuals. Women are also significantly more likely to support LGBT rights. Finally, models 3 and 4 add a cross-level interaction term between Europeanization at the country level and Supranational Identity at the individual. While Europeanization by itself, did not reach statistical significance in models 1 and 2, there is tentative support for our third hypothesis in model 3. When allowing the intercept to vary, the effect of supranational identity on support for gay rights is significantly higher in countries that are more deeply integrated with the EU. This effect, however, does not remain significant in the equivalent random slope model.

Next, Tables 2 and 3 show the results from executing the same types of models on our measures of support for gender equality. Findings appear similar for both indices. In all models, supranational identity has a statistically significant positive effect on support for gender equality and increases liberal attitudes on women’s issues. The effects are much smaller in magnitude compared with the effects of supranational identity on support for LGBT rights. This is interesting considering that the more controversial issue seems to be more influenced by ‘thin’ identifications such as those with Europe or the world. In relative terms, the sex of the respondent has the largest effect on attitudes toward gender equality, followed by fairly equal effects of religiosity, supranational identification, education, and degree of post-materialism. Country-level variables do not have strong effects in these models. Variance components suggest that the majority of unexplained variance comes indeed from the individual level. When a cross-level interaction term is introduced, there are fairly mixed results as to the importance of involvement with the EU. We see that when using the second index of gender equality, the effect of supranational identity on gender attitudes is significantly higher in more Europeanized countries. However, there does not seem to be a systematic relationship in the case of our first index of gender equality. This is likely due to the greater attention devoted by supranational bodies to career-related aspects of encouraging gender equality and hence, more Europeanized countries are more likely to associate having a supranational attachment with the need to support gender equality in matters of career and work-life balance.

Table 2 Multilevel OLS regression predicting support for gender equality (gender eq. index 1: children and family)

RI=random intercept.; RS=random slope.

Standard errors in parentheses.

Boldfaced coefficients significant at P<0.05. LR test vs. linear regression: χ 2 (3)=2258.54, Prob>χ 2=0.00.

Table 3 Multilevel OLS regression predicting support for gender equality (gender-eq. index 2: career and work-family balance)

RI=random intercept; RS=random slope.

Standard errors in parentheses.

Boldfaced coefficients significant at P<0.05. LR test vs. linear regression: χ 2 (3)=4701.08, Prob>χ 2=0.00.

Overall the models suggest a consistent systematic effect of supranational identity on value-cleavages such as attitudes toward LGBT rights and gender equality. Our third hypothesis concerning country-level differences in degree of EU integration receives only mixed support. As indicated by the initial descriptive data, more controversial issues such as the rights of homosexuals seems to elicit a more clear-cut country-level variation and subsequently produce greater differences in the conditional relationship between identity and social values. A caveat of these findings is that our Europeanization measure is fairly crude, but more precise measures are nonexistent at present, except in the case of the long-term EU member states. Moreover, the Europeanization literature itself has used membership status as a basic proxy for degree of Europeanization (Hix, Reference Hix2003).

Conclusion

Recent literature has pointed out that the EU has been expanding into the new category of morally contested issues that traditionally fell into the purview of domestic politics (Leconte, Reference Leconte2008). Taking this development as a starting point, the current study contributes to the emerging research agenda on supranational identification and its consequences for mass attitudes and orientations. Evidence, presented above, has demonstrated that a link does exist between individuals’ levels of supranational identification and their attitudes on morally contested issues in the national realm. Moreover, the magnitude of such effects appears greater on more controversial issues such as support for LGBT rights. Effects also appear stronger in the more ‘Europeanized’ societies, which have had longer experience with European integration and hence, greater exposure to supranational norms.

The implications of these findings are threefold. First, the results highlight the relevance of even ‘thin’ identifications such as one’s self-categorization in the international realm – a rather diffuse form of identity that is nonetheless able to influence cultural attitudes. How these identities interact with changing attitudes over time needs to be further investigated. While the current study focuses on a single time point, we acknowledge the possibly time-sensitive nature of both supranational identities and views on cultural issues. In particular, are identities formed first and eventually generate value judgments; or are people’s values the source of identities? Both causal directions are potentially at work with such closely-related concepts and, while we have attempted to posit a coherent theoretical justification as to why supranational identity can affect people’s values, future work would benefit from untangling the complex causal linkages between identities and attitudes by adopting a longitudinal approach.

Second, our findings have implications for the spread of international norms – those espoused by the EU in particular. While the majority of EU norms on cultural issues are informal and non-binding, we demonstrate that these norms are better received by individuals with high to moderate levels of supranational identity. Therefore, EU efforts in that area may indeed have encouraging results among less Eurosceptic populations. Given that this effect was found even in former Soviet countries that have no near-future prospects of EU membership, such direct mechanisms of norm diffusion between supranational institutions and citizens can be an important means of influence for EU policy-makers.

Third, while encouraging for the EU from a norm diffusion perspective, results also suggest that since more controversial issues exhibit a more pronounced relationship with supranational identity, domestic clashes over morally contested issues may ‘spill over’ into clashes over European integration. In some new EU member states, and non-EU members, the diffusion of ‘foreign’ EU-promoted liberal norms may be seen as eroding national culture and thus serve to intensify both the polarization over cultural issues and over European integration.

While economic issues are at the forefront of the debate over European integration at present, there is ample evidence from the immigration literature to suggest that culture-related issues can quickly trigger domestic contestation and polarization when brought to the surface. With the EU broaching into similarly sensitive cultural issues, even if mostly through informal norms, a similar increase in the domestic contestation of the EU’s actions can be expected.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the participants and audience of the panel ‘Causes and Consequences of Supranational Identity’ at the 2012 Biannual Meeting of the European Union Studies Association for their thoughtful comments and suggestions. Additionally, we would like to thank the two anonymous reviewers whose comments were instrumental in strengthening this article.

Appendix

Factor Analysis Eigenvalues

Method: principal components analysis.

Rotation: orthogonal varimax.