Social cleavages and election results in Western Europe

To what extent do social cleavages continue to shape election results in Western Europe? By many accounts, it is too soon to proclaim the death of traditional social cleavages such as class and religion. Although social characteristics arguably exert a lesser impact upon voting behaviour today than in the past, the cross-national variations in such patterns make generalization difficult, if not impossible. Literature in this area is often fraught with ambiguity. While some suggest that the linkages between cleavage groups and their traditional parties are on the decline (Dalton et al., Reference Dalton, Flanagan and Beck1984; Franklin, Reference Franklin1985; Clark and Lipset, Reference Clark and Lipset1991; Franklin et al., Reference Franklin, Mackie and Valen1992; Clark et al., Reference Clark, Lipset and Rempel1993; Nieuwbeerta, Reference Nieuwbeerta1996; Nieuwbeerta and Ultee, Reference Nieuwbeerta and Ultee1999; De Graaf et al., Reference DeGraaf, Heath and Need2001; Knutsen, Reference Knutsen2006), others view claims of cleavage decline with a heavy degree of scepticism and assert that cleavage structures remain mostly intact (e.g. Andersen, Reference Andersen1984; Evans, Reference Evans1993, Reference Evans1999; Brooks et al., Reference Brooks, Nieuwbeerta and Manza2006; Elff, Reference Elff2007). The most recent evidence encourages us to recognize country-level differences in cleavage structures and their varying patterns of influence on voting behaviour (Brooks et al., Reference Brooks, Nieuwbeerta and Manza2006; Elff, Reference Elff2007; see also Freire, Reference Freire2006). As Elff (Reference Elff2007) argues, variations in the relationship between cleavage position and voting behaviour should be expected, since contextual features such as party programmes will affect individual incentives to vote in line with cleavage positions. Due to contextual features, the voting behaviour of traditional social cleavage groups is likely to vary cross-nationally, even if there is a tendency for this behaviour to be on the decline.

The findings outlined above should shape our current understanding of electoral politics in Western Europe only if our concern is the voting behaviour of cleavage groups; often it is not. Scholars of electoral politics often have broader concerns that relate to overall patterns of support for political parties, electoral volatility, party system fragmentation, or other forms of macro-level changes in the distribution of the vote. When aggregate electoral outcomes are of interest, accounts of cleavage-based voting behaviour are not enough to link the behaviour of cleavage group members to party vote shares. While these studies may tell us about the likelihood that certain types of voters support certain types of parties, they do not tell us how (or even if) changing patterns of group-based voting behaviour are linked to shifts in party vote shares. In this article I demonstrate how such a link between traditional cleavage groups and party vote shares can be made. Furthermore, I demonstrate how the link between traditional cleavage groups and party vote shares can only be established by incorporating information on group size and turnout, in addition to voting behaviour. The voting behaviour of cleavage groups tells us only a fragment of a larger story, in that the votes of cleavage members matter more or less depending on the turnout and size of the cleavage group. Religious citizens, for example, who support their Christian democratic party without fail, will matter very little to the party’s vote share if there are only a handful of them.

The simple truth is that the numbers of traditional cleavage groups have declined as a result of structural changes in the economies and societies of Western Europe. For instance, Crouch (Reference Crouch2008) provides a recent and thorough description of the declines in the manufacturing industry and the restructuring of Western European economies that has diminished the numbers of the traditional working class (see also Broughton and ten Napel, Reference Broughton and ten Napel2000; Dogan, Reference Dogan2004). Regarding religion, the growing secularization of Western European societies is now a well-documented and virtually uncontested phenomenon (e.g. Dogan, Reference Dogan2004; Crouch, Reference Crouch2008). As Peter Mair notes, it is ‘undeniable’ that workers are still more likely to vote for leftist parties and religious citizens for Christian parties, but there are simply too few of them to have the effect on electoral politics that they once had (Reference Mair2008: 219).

It is this effect on electoral outcomes that determines the electoral relevance of cleavage groups. In order to provide a substantial contribution to a party’s vote share, members of a cleavage group must not only support their party at election time, but also have enough members to contribute a sizeable figure to the party’s vote total. With respect to social and Christian democratic parties, we have good reason to suspect that the electoral relevance of working class and religious citizens has declined. Many of these parties have experienced significant declines in their vote shares over the post-Second World War era. McDonald and Best (Reference McDonald and Best2006) found many negative and significant trends in the vote shares of social and Christian democratic parties. Table 1 replicates and extends this analysis for 21 social and Christian democratic parties in eight Western democracies. Table entries report the results of regressing party vote shares on time (controlling for incumbency status) and the mean party vote share. All Christian democratic parties and many social democratic parties exhibit significant declines in their vote shares over the post-Second World War era. While these two party families have clearly lost much of their electoral ground, the results also point to several interesting exceptions. The German SPD, the Irish Labour Party, and the Dutch PvdA have managed to avoid the declines that characterize parties in other nations, and the French PS displays a positive and significant trend. Overall, the negative trends in party vote shares suggest possible declines in the electoral relevance of traditional cleavage groups for these parties.

Table 1 Trends in vote support for social and Christian democratic parties (1950–2002)

Belgium (SP – Socialistische Partij/Flemish Socialist Party; PS – Parti Socialiste/Francophone Socialist Party; CVP – Christelijke Volkspartij/Christian People's Party; PSC – Parti Social Crétien/Christian Social Party), Denmark (SD – Socialdemokratiet/Social Democrats; Krf – Kristeligt Folkeparti/Christian People's Party), France (PS – Parti Socialiste/Socialist Party), Germany (SPD – Sozialdemokratische Partei Deutschlands/Social Democratic Party of Germany; CDU/CDU – Christlich-Demokratische Union/Christlich-Soziale Union/Christian Democratic Union/Christian Social Union), Great Britain (Lab – Labour Party; Con – Conservative Party), Ireland (LP – Labour Party), Italy (PCI – Partito Comunista Italiano/Communist Party; PDS – Partito Democratico della Sinistra/Democratic Party of the Left), the Netherlands (PvdA – Partij van de Arbeid/Labour Party; CDA – Christen-Democratisch Appel/Christian Democratic Appeal; KVP – Katholieke Volkspartij/Catholic People's Party; ARP – Anti-Revolutionaire Partij/Anti-Revolutionary Party; CHU – Christelijk-Historische Unie/Christian Historical Union).

Table entries are the results of regressing party vote shares in election years on time. Time is scored 0 in 1950. Each additional year adds one and months adds fractions.

*Statistical significance at the 0.05 level for one-tailed tests.

In this article I utilize a simple method of calculating the electoral relevance of a cleavage group for party vote shares that accounts for both electoral behaviour and group size. Electoral relevance of working class and religious citizens is then analysed over time for eight Western European democracies. The contributions of this study to the current literature on the relevance of traditional social cleavages are threefold. First, I demonstrate that when electoral results are of concern, it is essential to account for both group behaviour (turnout and voting behaviour) and group size. Furthermore, the approach utilized here illustrates the differing impact of changes in the size, turnout, and voting behaviour of traditional cleavage groups across countries and cleavage groups. Second, the findings presented here demonstrate pervasive, cross-national declines in the electoral relevance of traditional cleavage groups for their traditional parties. Despite the important cross-national differences that have been found in cleavage-based voting behaviour (e.g. Brooks et al., Reference Brooks, Nieuwbeerta and Manza2006), even fiercely loyal party supporters are no match for the structural changes that have withered away their numbers. While patterns of voting behaviour may vary cross-nationally, the declining electoral relevance does not. Third, the results of this study speak to a recent strain of literature that examines changes in cleavage-based voting behaviour in response to changes in party policy offerings (Evans et al., Reference Evans1999; De Graaf et al., Reference DeGraaf, Heath and Need2001; Elff, Reference Elff2009). Since declines in cleavage group size are unlikely to be counteracted by changes in party strategies, the results presented here illustrate little incentive for parties to employ electoral strategies that encourage traditional patterns of cleavage voting.

The electoral relevance of cleavage groups

Ever since the influential work of Lipset and Rokkan (Reference Lipset and Rokkan1967), social cleavages have been linked to the political alignments and party systems of Western Europe. Due to their historical strength in Western Europe, the two social cleavages that have received the bulk of scholarly attention have been social class and religion. These cleavages have been particularly influential in electoral politics and party systems, as the electoral success of social and Christian democratic parties is often attributed to the electoral support of working class and religious citizens (Lipset and Rokkan, Reference Lipset and Rokkan1967; Rose and Urwin, Reference Rose and Urwin1969, Reference Rose and Urwin1970). Two types of changes serve to undermine the electoral relevance of working class and religious citizens in Western Europe: changes in the behaviour of cleavage group members and changes in the size of these cleavage groups.

Social cleavages and electoral behaviour

Literature examining the continuance or decline of traditional social cleavages has generally focussed on the voting behaviour of cleavage group members, which is then contrasted with the voting behaviour of the opposing cleavage group(s) in measures such as the Alford index (see Manza et al. (Reference Manza, Hout and Brooks1995) for a review of the literature on social class). These assessments of voting behaviour are often driven by theoretical and empirical developments that give us reason to expect declines in cleavage-based voting. For instance, Dalton’s theory of cognitive mobilization suggest voters are relying less on social cues when casting their ballots as a result of educational increases and the prevalence of mass media (Dalton, Reference Dalton1984, Reference Dalton2002). An additional reason to suspect changes in voting behaviour comes from theories of value change and the growing importance of new issues. Inglehart (Reference Inglehart1977, Reference Inglehart1984, Reference Inglehart2008) suggests increases in material well-being have shifted the political preferences of some voters away from traditional cleavage politics. Studies that emphasize the importance of party strategies for cleavage-based voting are also directed at the degree of cleavage group loyalty towards political parties (Evans, Reference Evans2000; DeGraaf et al., Reference DeGraaf, Heath and Need2001; Elff, Reference Elff2007, Reference Elff2009). This body of work generally argues that parties can shape and respond to the degree of cleavage voting by choosing whether to make cleavage-based electoral appeals (see also: Przeworski and Sprague, Reference Przeworski and Sprague1986; Kitschelt, Reference Kitschelt1993, Reference Kitschelt1994). If parties emphasize cleavage issues in their electoral platforms, we can expect the amount of cleavage-based voting to increase, and vice versa.

Current debates over whether, where, and how much traditional social cleavages have (or have not) declined arise from this body of work that takes the voting behaviour of cleavage group members as its focal point. Commonly, the linkages between cleavage groups and their traditional parties are perceived to be on the decline (Dalton et al., Reference Dalton, Flanagan and Beck1984; Franklin, Reference Franklin1985; Clark and Lipset, Reference Clark and Lipset1991; Franklin et al., Reference Franklin, Mackie and Valen1992; Clark et al., Reference Clark, Lipset and Rempel1993; Nieuwbeerta, Reference Nieuwbeerta1996; Nieuwbeerta and Ultee, Reference Nieuwbeerta and Ultee1999; De Graaf et al., Reference DeGraaf, Heath and Need2001; Knutsen, Reference Knutsen2006). However, the uses of different definitions, statistical techniques, countries, and time periods have produced contrasting accounts of whether the importance of cleavages such as social class have declined (e.g. Korpi, Reference Korpi1972; Zuckerman and Lichbach, Reference Zuckerman and Lichbach1977; Franklin and Mughan, Reference Franklin and Mughan1978; Andersen, Reference Andersen1984; Manza et al., Reference Manza, Hout and Brooks1995; Evans, Reference Evans1999, Reference Evans2000; Karvonen and Kuhnle, Reference Karvonen and Kuhnle2001; Brooks et al., Reference Brooks, Nieuwbeerta and Manza2006; Knutsen, Reference Knutsen2006; Güveli et al., Reference Güveli, Need and de Graaf2007; cf. Nieuwbeerta, Reference Nieuwbeerta1996). For instance, Güveli et al. (Reference Güveli, Need and de Graaf2007) find that, while the old order of class-based voting may have declined, a new class structure has arisen that also has the capacity to structure the vote. Furthermore, some recent studies view claims of cleavage decline with a heavy degree of scepticism and assert that cleavage structures remain mostly intact (e.g. Andersen, Reference Andersen1984; Evans, Reference Evans1993, Reference Evans1999; Brooks et al. Reference Brooks, Nieuwbeerta and Manza2006; Elff, Reference Elff2007). If cleavage-based patterns of voting behaviour have declined, this assertion requires many cross-national qualifications and exceptions (Brooks et al., Reference Brooks, Nieuwbeerta and Manza2006; Elff, Reference Elff2007).

Patterns of cleavage-based voting behaviour have been found to fluctuate across both countries and time, often leading us to question whether traditional cleavages still provide structure to voting behaviour. However, the voting choices of traditional cleavage group members are only one component in the calculation of the relevance of these groups for their traditional parties, as I demonstrate below. An additional behavioural component – the turnout of cleavage group members – will also shape the electoral relevance of cleavage groups. Studies of cleavage structures often point to the historical role of labour unions and churches as mobilizing forces on cleavage group members (Lipset and Rokkan, Reference Lipset and Rokkan1967). As the numerical strength of membership in labour unions and churches has declined, we can also expect mobilization of traditional cleavage groups to be on the decline.

The declining size of traditional cleavage groups

In additional to behavioural components, changes in the size of traditional cleavage groups have the potential to dramatically affect their relevance for party vote shares. Furthermore, there is little doubt that the numerical size of traditional cleavage groups has been on the decline. A growing service sector, increases in white-collar employment, declines in industrial labour, and increased secularism have reduced the numbers of working class or religious voters in Western societies (Heath et al., Reference Heath, Jowell and Curtice1985; Kitschelt, Reference Kitschelt1993; Pontusson, Reference Pontusson1995; Broughton and ten Napel, Reference Broughton and ten Napel2000; Dogan, Reference Dogan2001; Knutsen, Reference Knutsen2004; Norris and Inglehart, Reference Norris and Inglehart2004). And while most studies of the class cleavage make little more than passing reference to changes in the size of the working class, Heath et al. demonstrate that about half of the decline in Labour’s vote share in Great Britain between 1964 and 1983 could be attributed to the declining size of the working class (1985: 35–37).

Scholarship on social cleavages has typically favoured examinations of behavioural changes instead of changes in cleavage group size; even after the potential influence of group size on cleavage relevance has been amply acknowledged. For instance, Brooks et al. (Reference Brooks, Nieuwbeerta and Manza2006) state that changes in relevant social cleavages ‘take one of two forms: either change in the partisan alignments of specific groups or change in the relative size of groups’ (p. 91) before moving on to examine only the voting behaviour of cleavage group members. Similarly, De Graaf et al. (Reference DeGraaf, Heath and Need2001) recognize the importance of ‘compositional’ changes in society that alter the size of cleavage groups and, consequently, the vote shares of political parties, but then examine only behavioural elements of change. Despite the paucity of studies that cite declining size as the primary source of cleavage decline (but see Dogan, Reference Dogan2001, Reference Dogan2004), the fact that all Western democracies have experienced de-industrialization and secularization makes the size of traditional groups a potentially critical influence on the electoral relevance of social cleavages. As Van Holsteyn and Irwin note, ‘No political party based upon religion can gain votes if there are no adherents who identify with the relevant religious group’ (Reference Van Holsteyn and Irwin2000: 79). The same can be said of parties based upon social class. In fact, in the following analyses changes in the size of traditional cleavage groups stand out as one of the crucial elements in their declining electoral relevance.

Assessing electoral relevance

The proportion of the vote a party receives from a cleavage group defines the electoral relevance of a cleavage group for a party’s vote share. Electoral behaviour (voting behaviour and turnout) is not the sole determinant of electoral relevance, but interacts with cleavage group size to determine the group’s electoral relevance for a party of interest. Thus, looking at any one aspect alone will provide an incomplete picture of electoral relevance.Footnote 1 The loyalty of cleavage groups towards their traditional parties matters very little in terms of party support if the cleavage group has few members. Of course, a large cleavage group will be inconsequential for party vote shares if no member of the group votes for the party. And neither the size nor the loyalty of the group will matter if nobody in the group turns out to vote. Thus, the proper measurement of electoral relevance is the following interaction of size, turnout, and loyalty.

where Size of the Group = the proportion of the electorate belonging to a cleavage group; Turnout of the Group = the proportion of the cleavage group that voted in a given election; and Loyalty of the Group = the proportion of cleavage group votes cast for the party of interest.

This equation tells us the total percentage of electoral support given to a political party by a cleavage group or, in other words, the contribution of the group to party vote shares (see also Axelrod’s (Reference Axelrod1972) use of a similar equation to estimate party support in the USA). This is the number of interest when one is concerned with electoral outcomes, since it tells us how much electoral support a political party derives from a cleavage group.

Changes in any one of the three variables – size, turnout, and loyalty – will alter the contribution of a cleavage group to party vote shares. For instance, if in country X the working class constitutes 50% of the population, casts 60% of their ballots for the social democratic party, and has a turnout rate of 80%, then the contribution of the working class to the social democratic party is 24%. Thirty years later, the working class in country X which constitutes 20% of the population at present, has a turnout rate of 80%, and casts 80% of their ballots for the social democratic party. If one looks only at voting patterns it will appear as though the strength of the class cleavage has increased – a higher percentage of the working class now votes for the social democratic party. But this higher level of loyalty may mean little to the social democratic party, who now receives a contribution of only 13% from the smaller working class population. Size, loyalty, and turnout are interrelated when it comes to electoral relevance. If any one of these variables drops to zero, the others become irrelevant.

Changes in size, loyalty, and turnout also bear different, and important, implications for the future of electoral alignments. If the electoral relevance of cleavage groups has declined only due to changes in electoral behaviour, then the future of cleavage politics can be moulded by political actors. Loyalty and turnout rates are a result of the choices made by voters and political parties, so that declines in loyalty could be reversed by changes in party strategies (e.g. Elff, Reference Elff2007). In contrast, declines that are the result of changes in the size of a cleavage group are not so easily remedied. The size of the working class population and the degree of secularism are the product of broad structural changes in society that are unlikely to be reversed. Changes produced by the diminishing size of cleavage groups will signal lasting declines in electoral relevance, which in turn will likely bring lasting changes to electoral competition and party strategies (Mair, Reference Mair2008).

Data and analysis

Investigating trends in electoral relevance requires data on voter behaviour and characteristics that span both countries and time. The Eurobarometer survey series are the data source that contains the necessary information in yearly surveys from 1975–2002. Furthermore, these are the same data used recently by Elff who concludes, ‘Reports of the death of social cleavages are exaggerated’ (Reference Elff2007: 289). The results of the following analyses bear rather different implications about the future of traditional cleavage groups.

Data are gathered from 26 surveys in the Eurobarometer series, one representing each year from 1975–2002.Footnote 2 Data are available through the entire time period for eight nations: Belgium, Denmark, France, Germany, Great Britain, Ireland, Italy, and the Netherlands. These countries provide a nice sampling of the historical strengths of the class and religious cleavages as recorded in the literature.Footnote 3 In two of these nations, Denmark and Great Britain, social class has historically been a strong influence on voting behaviour. Slightly lower levels of class voting have been reported in Belgium and Germany. Even lower levels of class voting have been reported in the remaining countries – France, Ireland, Italy, and the Netherlands – where religion often trumps class as the dominant cleavage influence on voting behaviour (Rose, Reference Rose1974; Franklin, Reference Franklin1985; Nieuwbeerta and DeGraaf, Reference Nieuwbeerta and DeGraaf1999).

Scholarship on the class cleavage usually focuses on the different voting patterns of manual and non-manual members of the labour force. Furthermore, accounts of the evolution of social democratic parties stress the linkages between these parties and the industrial working class. Following this tradition, I focus on the contribution of manual workers and households headed by manual workers to social democratic parties.Footnote 4 Respondents were coded as manual workers if they, or the head of their household, were currently employed as a skilled or unskilled manual worker or supervisor.Footnote 5 The Eurobarometer regularly asks respondents to place themselves and their head of household into an occupational category, which I use to identify respondents as manual workers.

Two indicators of religious affiliation are used: denomination and the frequency of church attendance. Churchgoers are often cited to be the most loyal to Christian democratic parties, although Christians often represent the potential base from which Christian democratic parties can derive their support (Broughton and ten Napel, Reference Broughton and ten Napel2000). Respondents are first coded as simply being ‘Christian’. However, there is reason to suspect that different denominations may exhibit different patterns. In Belgium and Italy, the relevant denomination for support for a Christian democratic party is Catholic, in Denmark it is Protestant, and in Germany and the Netherlands Christian democratic parties have drawn their support roughly equally from both Catholics and Protestants (Rose, Reference Rose1974).Footnote 6 Therefore, I also separate Christians into Catholics and Protestants. Following convention in the literature, respondents are coded as ‘churchgoers’ if they report going to church at least once a week.

The Eurobarometer surveys use two types of questions to gauge the voting behaviour of the respondent: reported past voting behaviour and vote intention in the next election. Since questions of past voting behaviour are asked irregularly throughout the series, I use only the vote intention question as the measure of party support and turnout.Footnote 7 I restrict the analysis of party support to those parties identified in Table 1.Footnote 8 Manual workers were coded as being ‘loyal’ if they intended to vote for social democratic parties or, in the case of Italy, communist parties.Footnote 9 Religious respondents were coded as being ‘loyal’ if they intended to vote for Christian democratic parties. Examination of the data reveals volatility in the measure of party support and, to a lesser extent, turnout rates. This is unsurprising, since partisan support may fluctuate between elections in response to current events, governmental performance, or any other number of factors. The following analyses therefore employ three-election moving averages of cleavage loyalty, size, and turnout.Footnote 10

The electoral relevance of social class and religion in the 1970s

The early years of the Eurobarometer surveys provide the benchmark for analysing subsequent declines in the electoral relevance of social class and religion. Table 2 lists the average contribution of manual workers to social democratic parties in the earliest years of the survey – 1975–77 – as well as their loyalty rates towards social democratic parties during these years. To compare the electoral relevance of manual workers with the electorate in general, Table 2 also lists the total amount of national support gained by social democratic parties (National Turnout*National Loyalty) and national loyalty to social democratic parties.

Table 2 Contributions and loyalty rates of manual workers to social democratic vote shares (1975–77)

Table calculations are from the Eurobarometer survey series: 1975–77. The contributions of manual workers to social democratic parties are calculated by multiplying the size, turnout, and loyalty of manual workers. The contributions of all respondents are calculated by multiplying national turnout rates by national loyalty rates.

While manual workers are commonly portrayed as core constituents for social democratic parties, we can see that they contributed rather low percentages of support to social democratic vote shares in the 1970s. In all countries, social democratic parties derived less than half of their total support from manual workers. Furthermore, the contributions of manual workers to social democratic parties range from a low of almost 5% in Ireland and Italy to a high of a 15.4% contribution to the Labour Party in Great Britain. In substantive terms, these figures suggest the vast majority of social democratic vote shares were gathered from the non-manual population. However, the contributions of manual workers to social democratic parties do correspond to cross-national differences in the class cleavage. The class cleavage is commonly regarded as strong in Denmark and Great Britain, and weaker in countries where other cleavage divides – such as religion – are important, as in Belgium, Ireland, and Italy. Thus, the figures for manual workers appear to tap the cross-national variations in the class cleavage rather well, but illustrate that manual workers made only a very small contribution to social democratic parties.

The figures for manual workers look a bit different if we look only at initial loyalty rates. In Denmark and Germany, a majority of manual workers cast their ballots for social democratic parties. In all countries considered, the loyalty rates of manual workers towards social democratic parties were higher than those of the general electorate. If social democratic vote shares are of interest, then loyalty rates clearly do not provide a complete picture. Although a majority of Danish and German manual workers supported social democratic parties, they accounted for less than a third of social democratic vote shares.

Table 3 presents similar figures for Christians, churchgoers, and Christian democratic parties. In sharp contrast to their social democratic counterparts, Christian democratic parties derived almost all of their support from their cleavage base: the Christian population. On average, only about 2% of the national vote going to Christian democratic parties came from non-Christians. A strong share of this support came from churchgoers, who constituted over half of the national support for Christian democratic parties in Belgium, Italy, and the Netherlands. In absolute terms, churchgoers gave a sizable 14–25% of the vote and Christians gave a significant 25–39% of the vote to Christian democratic parties.Footnote 11 The Christian population appears to have been critically relevant to the vote shares of Christian democratic parties.

Table 3 Contributions and loyalty rates of Christians to Christian party vote shares (1975–77)

Table calculations are from the Eurobarometer survey series: 1975–77. The contributions of Christians/churchgoers to Christian democratic parties are calculated by multiplying the size, turnout, and loyalty of Christians/churchgoers. The contributions of all respondents are calculated by multiplying national turnout rates by national loyalty rates.

Loyalty rates of the religious population tell only a slightly different story. A majority of Christian voters in Belgium and almost half of Christian voters in Germany and the Netherlands supported Christian democratic parties, although Christians accounted for almost the entire vote share of these parties. Churchgoers, while constituting a sizeable but lower proportion of Christian democratic vote shares, were fiercely loyal towards these parties, casting between 66% and 72% of their ballots for Christian democrats in Belgium, Germany, Italy, and the Netherlands. Churchgoers were more loyal party supporters, but Christians contributed more to Christian democratic vote shares.

Table 4 examines the contributions and loyalty rates by denomination. In Belgium, Italy, and Great Britain, the contributions and loyalty rates of Catholics or Protestants largely match the figures for Christians. However, in Germany and the Netherlands, Christian support for Christian democratic parties is split between Catholics and Protestants. In both countries, Catholics appear to have been more consequential than Protestants for party vote shares and exhibit higher loyalty rates.

Table 4 Contributions and loyalty rates of Catholics and Protestants to Christian party vote shares (1975–77)

Table calculations are from the Eurobarometer survey series: 1975–77. Contributions are calculated by multiplying size, turnout, and loyalty.

The electoral relevance of social class and religion (1975–2002)

The following analyses investigate whether there have been temporal changes in cleavage contributions to party vote shares by regressing the contributions of manual workers and Christians on time for each of the eight countries. To tease out the independent effects that changes in size, loyalty, and turnout have had on the contributions of cleavage groups to social or Christian democratic parties, cleavage contributions are also calculated varying only one variable at a time – size, turnout, or loyalty – while holding the other two variables constant at their 1975–77 values. When these calculations are regressed on time, the results illustrate the independent effects of changes in size, loyalty, and turnout on the total contributions of cleavage groups.Footnote 12

Manual workers

Table 5 presents the results of regressions for manual workers. Manual workers contributed a low percentage of support to social democratic vote shares at the beginning of the series, and they have become noticeably less relevant over time. Across all countries, the manual worker contribution to social democratic parties has declined significantly since the 1970s, particularly in Italy and the Netherlands. While manual workers gave between 5% and 16% of the national vote to social democratic parties in the 1970s, these results suggest that they contributed even less to social democratic vote shares in subsequent decades. Social democratic parties appear to have lost a good deal of the vote share they received from manual workers in the past.

Table 5 Sources of change in the contributions of manual workers to social democratic parties: size, turnout, and loyalty

Table entries are the results of regressing the variables on time. Size, turnout, and loyalty regressions represent the trends in the contribution when only the reported variable is allowed to vary and the others are held constant at their 1975–77 values.

N = 23 for Belgium, France, Great Britain, and the Netherlands, 24 for Denmark, Germany, and Ireland, and 17 for Italy.

*Statistical significance at the 0.05 level for one-tailed tests.

Generally speaking, declines in all three factors – size, turnout, and loyalty – have driven the declines in the contributions of manual workers we observe. Of these three components of cleavage group contributions, the most consistent results are found regarding the size of the population of manual workers. Declines in the size of the manual worker population have driven significant declines in manual worker contributions in all eight countries, particularly in Belgium, Great Britain, and the Netherlands. The findings also reveal important declines in the proportions of manual workers who support social democratic parties, with significant decreases in manual worker loyalty rates in six of the nations considered: Belgium, Denmark, France, Germany, Italy, and the Netherlands. Turnout rates also appear to have played a more modest role in the declines we observe in manual worker contributions, with relatively small declines apparent in Belgium, Germany, Great Britain, Ireland, Italy, and the Netherlands.

Great Britain deserves special consideration. The contribution of manual workers to the British Labour Party exhibits a decline similar to that found in other countries. However, loyalty rates among British manual workers display significant increases. If one looks only at the loyalty rates of manual workers, then cleavage-based politics appears to be not only alive and well, but also on the rise. The increasing tendency of manual workers to support Labour, however, appears to have been overwhelmed by declines in their numbers. Manual workers contribute less to Labour’s vote share not because they are voting for different parties, but simply because there are fewer of them.

Religion

Although less scholarly attention has been devoted to religion, it has been cited as the cleavage of greater importance (e.g. Dogan, Reference Dogan2004). The figures presented in Table 3 give credence to this claim. Unlike the contributions of manual workers to social democratic parties, the religious population constituted almost all of the electoral support for Christian democratic parties. Thus, any declines in the contributions of religious citizens could have severe consequences for party vote shares. Table 6 presents the results of regressions of the contributions of Christians and churchgoers to Christian democratic party vote shares over time.

Table 6 Sources of change in the contributions of Christians to Christian democratic parties: size, turnout, and loyalty

Table entries are the results of regressing the variables on time. Size, turnout, and loyalty regressions represent the trends in the contribution when only the reported variable is allowed to vary and the others are held constant at their 1975–77 values.

For Christian regressions: N = 19 for Germany, 18 for Denmark and the Netherlands, 17 for Belgium, and 15 for Italy.

For churchgoer regressions: N = 14 for Germany, 13 for Belgium, Italy, and the Netherlands, and 12 for Denmark.

*Statistical significance at the 0.05 level for one-tailed tests.

The results display declines in the contributions of both Christians and churchgoers to Christian democratic parties in all countries. These declines are both substantively and statistically significant. The declining contribution of Christians amounts to a loss of at least 14% of the vote since 1975 in all countries but Denmark. Most of these declines are driven by declining contributions of churchgoers. In Belgium, Germany, Italy, and the Netherlands, churchgoer contributions to Christian democratic parties have dropped between 12% and 22% since the 1970s. Christian democratic parties are gathering much less of the vote from religious citizens than in the past. Considering their initial levels of support, this is likely to have severe consequences for Christian democratic parties.

Declines in the size of the religious population often stand out as the largest contributor to these trends, although in some cases declining loyalty rates have played the most prominent role. In Germany and the Netherlands, declining contributions have been driven mostly by dwindling numbers of religious citizens. In Great Britain and Italy, however, the declining contributions of Christians can be mainly attributed to declining loyalty rates. In Italy, the proportion of the population that reports attending church at least once a week has actually increased. Belgium also presents an interesting case. While the declining contributions of Belgian Christians have been driven by declining loyalty rates, the declining contributions of churchgoers have been driven primarily by declines in size.

Table 7 presents the results of similar regressions by denomination. The patterns of decline mirror the patterns found for Christians, with the exceptions of Germany and the Netherlands where both Catholics and Protestants constitute the basis of support for Christian democratic parties. The declines in the contributions of Catholics in both countries have been larger than the declines for Protestants. This holds both among identifiers and churchgoers. Identifiers in Germany appear to have become less loyal, while the declining contributions of Catholic churchgoers can be largely explained in terms of declines in size. In the Netherlands, both the size and loyalty of Catholic and Protestant identifiers have declined, while the size of Catholic churchgoers and the loyalty of Protestant churchgoers explain the declining contributions of these groups.

Table 7 Sources of change in the contributions of Catholics and Protestants: size, turnout, and loyalty

Table entries are the results of regressing the variables on time. Size, turnout, and loyalty regressions represent the trends in contributions when only the reported variable varies, while the others are held constant at their 1975–77 values.

For Catholics, N = 17 for Belgium and Germany, 18 for the Netherlands, and 15 for Italy.

For Protestants, N = 18 for the Netherlands, 19 for Germany, and 17 for Denmark.

For Catholic churchgoers, N = 13 for Belgium, the Netherlands, Germany, and 12 for Italy.

For Protestant churchgoers, N = 12 for Denmark, 14 for Germany, and 13 for the Netherlands.

*Statistical significance at the 0.05 level for one-tailed tests.

Cleavage groups, vote shares, and party strategies

While most scholarship on the continuity or decline of traditional social cleavages has focussed on changes in the voting behaviour of cleavage group members, the analyses presented above examine changes in the electoral relevance of traditional social cleavage groups for the vote shares of their traditional parties. The analyses demonstrate that when traditional social cleavage groups are viewed in terms of electoral relevance, rather than their voting behaviour alone, the general picture is one of decline.

These findings highlight three contributions of this study to the existing literature on traditional social cleavages. First, when electoral results are of concern, examination of the voting behaviour of traditional cleavage group members provides only a piece of the picture. The results for both manual worker and religious contributions clearly demonstrate that the electoral relevance of a cleavage group is not equivalent to the electoral behaviour of the cleavage group. For instance, if one looks only at the loyalty rates of British manual workers, then the electoral strength of manual workers appears to have increased over time, even though the contribution of manual workers to Labour has declined over this period. More generally, the results demonstrate that strong loyalty rates do not always translate into a high level of electoral relevance. Important cross-national differences in cleavage-based voting behaviour (e.g. Brooks et al., Reference Brooks, Nieuwbeerta and Manza2006), but even where cleavage group members remain strong supporters of their traditional parties their loyalty cannot make up for what they have lost in numbers. While patterns of voting behaviour may vary cross-nationally, the declining electoral relevance of traditional cleavage groups does not. More generally, the analyses presented here demonstrate that all three components (size, turnout, and loyalty) interact to determine the size of the group’s contribution to a party’s vote share.

Second, the findings presented here demonstrate pervasive, cross-national declines in the electoral relevance of traditional cleavage groups that are heavily driven by socio-demographic changes. While there is a wealth of literature documenting changes in traditional cleavage-based voting behaviour, the findings presented here stress the importance of declines in group size. Much of the declining relevance of these groups can be traced to the simple fact that there are fewer members of these cleavage groups than there were in the past. These findings are significant in that they signal declines due to widespread changes in the structure of Western European societies. Since these structural changes are likely irreversible, the declining relevance of traditional cleavage groups is likely irreparable. No amount of political manipulation will shift the post-industrial economies of today back to the industrialized economies of the past. And while there is always a slight chance that societies will become more religious, the changes that we observe are likely to be permanent alterations in the political landscape. Social and Christian democratic parties will have to respond to the declining size of their core base by altering their electoral strategies or will face declining vote shares. This means that party strategies are likely to become increasingly catch-all in nature, partisan alignments are likely to become increasingly variable, and electoral politics in Western European democracies is likely to be fundamentally different from the past (Mair, Reference Mair2008).

Third, the results of this study speak to recent research that views cleavage-based, or ideological, voting behaviour in light of party policy offerings (Evans et al., Reference Evans, Heath and Payne1999; DeGraaf et al., Reference DeGraaf, Heath and Need2001; Lachat, Reference Lachat2008; Elff, Reference Elff2009). Generally, the argument of these studies is that cleavage-based voting depends on the strategies of political parties. When political parties stake out distinct positions on cleavage-based issues, the amount of cleavage-based voting is expected to increase. The findings presented here do not dispute this argument, but question the incentives for parties to pursue such cleavage-reinforcing strategies. Parties may always have reason to stake out clear policy positions, but it is not clear that staking out clear positions on cleavage-based issues – at least as traditionally defined – will provide an electoral benefit. Since declines in cleavage group size are unlikely to be counteracted by changes in party strategies, the results presented here illustrate little incentive for parties to employ electoral strategies that encourage traditional patterns of cleavage voting.

There are strong signs that social and Christian democratic party strategies will (continue to) depart from traditional cleavage-based politics. If these parties perceive the declining size of their traditional constituencies, as they surely do, they can alter their electoral strategies in ways that depart from traditional cleavage politics in the hopes of gaining votes from elsewhere. And since party appeals may serve to either strengthen or weaken cleavage attachments (Dalton, Reference Dalton2002), political parties themselves may encourage disloyalty by de-emphasizing cleavage issues. Examination of the timing of these declines and the role of party strategies is a necessary and fruitful avenue for future research. Furthermore, the extant literature gives us good reason to suspect that the social democratic parties of Great Britain and Ireland may have prevented declining loyalty rates among manual workers by making stronger cleavage-based electoral appeals.

Party strategies have also played a likely role in producing the interesting disjunctions observed between the declining electoral relevance of manual workers and the trends in social democratic party vote shares. In France, Germany, and the Netherlands, the contribution of manual workers to social democratic parties has declined, yet the vote shares of these parties display no evidence of these declines. Declining support from the working class may not matter to general patterns of electoral support if parties counteract these losses with gains in other areas. For instance, Kitschelt’s (Reference Kitschelt1994) description of the social democratic dilemma details the changes in strategy that are often necessary for social democratic parties to avoid declining vote shares when their traditional constituencies have diminished.

Social democratic parties may be particularly adept at finding new constituencies, since the manual working class has never constituted a majority (Przeworski and Sprague, Reference Przeworski and Sprague1986). The findings presented here suggest that some social democratic parties have been more successful than others at representing more diverse constituencies. While the traditional working class was comprised of a roughly homogenous group of male, unionized, industrial manual labourers, the new ‘service proletariat’ (cf. Esping-Andersen, Reference Esping-Andersen1993) is more heterogeneous in both composition and political interests than the traditional working class (Oesch, Reference Oesch2006; Güveli et al., Reference Güveli, Need and de Graaf2007). Lower-level service workers tend to be heavily female, and often young and economically mobile (Esping-Andersen, Reference Esping-Andersen1993; Bernardi and Garrido, Reference Bernardi and Garrido2008), making it difficult for parties to rely on this new ‘class’ as a political base. Nonetheless, fluctuations in social democratic party vote shares are likely due to their willingness and ability to appeal to these new social groups (Güveli et al., Reference Güveli, Need and de Graaf2007). As the traditional industrial order continues to decline, social democratic vote shares are likely to become more dependent on the new service classes.

The declining electoral relevance of religion is more striking in two respects. First, all Christian democratic parties considered have lost electoral ground over the post-Second World War era. Second, the large contributions of religious citizens to Christian democratic parties in the 1970s have declined significantly in all countries. What we are witnessing is a cross-national decline in the electoral relevance of religious citizens for Christian democratic vote shares, which have also rapidly declined (presumably) as a result of growing secularism. This significant loss of the Christian base of support is not likely to be easily overcome, although there are certainly alternative strategies and constituencies available to Christian democrats (van Kersbergen, Reference Van Kersbergen2008).

This study stands apart from typical accounts of cleavage politics in that it has considered cleavage groups in connection with party vote shares. Viewed from this perspective, the general conclusion is that the electoral relevance of traditional cleavage groups, specifically manual workers and Christians, has declined. These cleavage groups give lower degrees of electoral support to social and Christian democratic parties than they did in the past. Whether it is changes in party strategies or party vote shares, the declining electoral relevance of traditional cleavage groups will continue to change the nature of electoral politics in Western democracies. Future party alignments and electoral strategies are unlikely to resemble those of the past.

Appendix

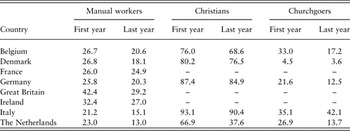

The percentages of manual workers and religious citizens in the first and last available years of the Eurobarometer surveys

Table entries are 3-year averages. Figures for manual workers represent the percentage of respondents in households headed by a manual worker.

The percentages of Catholics and Protestants in the first and last available years of the Eurobarometer surveys

Table entries are three-year averages.