Introduction

Over the last decade, non-violent protest has reached new heights in modern democracies (Inglehart, Reference Inglehart1990; Tarrow, Reference Tarrow1998; Norris, Reference Norris2002; McAdam et al., Reference McAdam, Tarrow and Tilly2003; Dalton, Reference Dalton2006; Kriesi, Reference Kriesi2008; Dalton et al., Reference Dalton, van Sickle and Weldon2010): an increasing number of people are taking part in peaceful demonstrations, signing petitions, or participating in boycotts to express social grievances and pressure governments. Accordingly, numerous scholars have examined the causes of non-violent protest behavior with foci on single protest movements, specific countries, or general individual attributes and attitudes. Socio-economic factors and political attitudes thereby play an important role in explaining protest behavior on the individual level (Barnes et al., Reference Barnes, Farah and Heunks1979; Inglehart, Reference Inglehart1990; Opp, Reference Opp1990; Verba et al., Reference Verba, Schlozman and Brady1995); whereas on the contextual level, the research mainly concentrates on the explanatory power of political institutions and the accompanying political opportunity structures (Eisinger, Reference Eisinger1973; Tilly, Reference Tilly1978; Kitschelt, Reference Kitschelt1986; Kriesi et al., Reference Kriesi, Koopmans, Duyvendak and Giugni1995; Kriesi and Wisler, Reference Kriesi and Wisler1996; Meyer, Reference Meyer2004; Tarrow, Reference Tarrow2011; Fatke and Freitag, Reference Fatke and Freitag2013; Quaranta, Reference Quaranta2013). Recently, however, a new strand of research has emerged which introduces cultural factors and their interplay with individual attitudes and values to the analysis of non-violent protest behavior (Dalton et al., Reference Dalton, van Sickle and Weldon2010; Welzel and Deutsch, Reference Welzel and Deutsch2012; Welzel, Reference Welzel2013). Welzel and Deutsch (Reference Welzel and Deutsch2012: 465), for example, argue that the examination of the link between psychological variables, such as attitudes and values, and behavior should not be limited to the individual level but should pay attention to societal level effects in order to ‘give […] “culture” its full weight in explaining behaviour’. Based on these insights, our contribution seeks to dig deeper into this new line of research on the relationship between individual attitudes, the attitudinal climate, and political behavior by asking how intolerance toward ethnically, religiously, or culturally diverse groups on both the individual and contextual level is related to non-violent protest behavior. By examining this research question we are able to contribute to the existing literature in three important ways, as both intolerance as well as non-violent protest comprise two highly relevant and largely discussed issues in modern civil societies.

First and in contrast to prior research, we focus on one specific individual attitude as a trigger factor for protest behavior: intolerance toward ethnically, religiously, and culturally diverse groups. Intolerance, in terms of an objection toward diverse groups, represents a major challenge for mature democracies as they are confronted with increasing cultural and ethnic diversity that may erode the public’s general acceptance of immigrants (Norris, Reference Norris2002; Inglehart and Welzel, Reference Inglehart and Welzel2005; Kirchner et al., Reference Kirchner, Freitag and Rapp2011; Freitag and Rapp, Reference Freitag and Rapp2013). While intolerance has high social prevalence, the consequences of this social attitude are less known (Gibson, Reference Gibson1992). Nonetheless, there are examples that underscore the potential behavioral consequences of intolerance: in countries where the public can voice their negative sentiments toward immigrants via institutionalized channels, such as direct democratic instruments, regular votes against immigrants take place as the example of Switzerland shows (Kriesi et al., Reference Kriesi, Lachat, Selb, Bornschier and Helbling2005). But how do individuals voice their intolerance in countries without well-developed direct democratic instruments? One possible way to express opinions in a rather direct way could be engagement in non-violent protest activities.

Second, if there are behavioral consequences of intolerance, hitherto we cannot be sure about their direction. Flanagan and Lee (Reference Flanagan and Lee2003), for example, find that there is a positive relationship between tolerance and an individual’s protest potential, for tolerant people are generally more liberal-leaning and more likely to actively engage in non-violent protest. In sharp contrast, among tolerance researchers the idea prevails that intolerant individuals will be more prone to protest behavior, as intolerance is a stronger and more expressive attitude than tolerance (Gibson, Reference Gibson1992, Reference Gibson2006). The relative deprivation theory (Gurr, Reference Gurr1970), which argues that socially and politically dissatisfied individuals will be more likely to engage in political action, since it is a means to express personal frustration, provides theoretical support for this line of reasoning (Barnes et al., Reference Barnes, Farah and Heunks1979). Recent mass protests in Germany against immigrants from Islamic countries may lend some anecdotal evidence to this argument. The following analysis addresses this obvious puzzle on the relationship between intolerance and non-violent protest behavior.

And last, starting with the path-breaking publication by Almond and Verba (Reference Almond and Verba1963) and drawing on the more recent contribution by Welzel and Deutsch (Reference Welzel and Deutsch2012), it is generally agreed that a country’s prevalent attitudinal culture shapes individual political action. Following this line of reasoning, we expand the literature by analyzing how the attitudinal prevalence of intolerance in a country directly affects an individual’s likeliness to actively engage in non-violent protest. Besides this direct effect, we argue that the attitudinal climate further influences the relationship between individual levels of social intolerance and protest participation. Two competing hypotheses regarding this assumption can be formulated: following the social psychological insights about conformity (Asch, Reference Asch1956) as well as the proposition regarding the spiral of silence (Noelle-Neumann, Reference Noelle-Neumann1974), we expect that a uniform climate of intolerance reinforces the individual-level effect of intolerance on protest participation. From a rational choice perspective (Downs, Reference Downs1957), however, a negative moderating effect is expected, as the expression of opinions becomes redundant for intolerant people within an intolerant culture.

To test our individual and contextual-level hypotheses, we implement multilevel models with cross-level interactions using the World Values Survey (2005–2008) (wave 5). Our results indicate that intolerant individuals will be more actively engaged in non-violent protest, whereas a contextual climate of intolerance leads to less individual protest participation. In contrast, the results based on the conditional hypotheses reveal that the overall attitudinal climate reinforces the positive effect of individual ethnic, religious, and cultural intolerance on the likeliness of protest behavior.

Our paper proceeds as following: in the next section, we outline our main concepts and the theoretical implications underlining the relationship between individual as well as contextual-level intolerance and non-violent protest participation. On this basis, we establish our main research hypotheses. In the fourth section, we elaborate on the methodology used and subsequently subject our main hypotheses to systematic empirical testing. A conclusion completes the article.

The concepts of non-violent protest and social intolerance

Our study focuses on the relationship between intolerance and non-violent protest behavior. Before we elaborate on this, we first specify the two concepts. Broadly speaking, political protest is a form of unconventional political participation (Barnes et al., Reference Barnes, Farah and Heunks1979; van Deth, Reference van Deth2009: 146).Footnote 1 Even though political protest is indeed on the rise and has become widespread since the 1990s (Tarrow, Reference Tarrow2011), the percentage of people engaging in this kind of action is still quite low compared with the percentage taking part in elections (Norris, Reference Norris2002; van Deth, Reference van Deth2009). Therefore, it is reasonable to label this kind of activity as unconventional. We define political protest as the public expression of dissent by individuals or groups in order ‘[…] to influence a political decision or process, which they perceive as having negative consequences for themselves, another group or society as a whole’ (Rucht, Reference Rucht2007: 708). Political protest includes a broad range of actions. While all of these actions are extra-representational, meaning that they do not make use of traditional representational channels to achieve their goals, they can be either exit- or voice-based (Teorell et al., Reference Teorell, Torcal and Montero2007: 340ff.). Political consumerism is assumed to be an exit-based mode of political protest because it follows the logic of a competitive market. On the contrary, taking part in a demonstration is a voice-based form of political protest, where people explicitly and publicly express their political demands. Non-violent protest – or ‘peaceful protest’ as Norris (Reference Norris2002: 191) calls it – means that neither people nor property is harmed by this kind of political action. Subsequently, it is clearly discernable from violent protest activities, like riots.Footnote 2

Intolerance, which is the main explanatory variable in our study, is defined as the objection to groups outside one’s own ethnicity, religion, or culture (cf. Dunn et al., Reference Dunn, Orellana and Singh2009; Kirchner et al., Reference Kirchner, Freitag and Rapp2011).Footnote 3 Within the last decade, rising immigration and cultural diversity has led to increased societal conflicts over diverging views and attitudes (Quillian, Reference Quillian1995; Inglehart and Baker, Reference Inglehart and Baker2000; Flanagan and Lee, Reference Flanagan and Lee2003; Schneider, Reference Schneider2008; Rapp, Reference Rapp2015). As a consequence, the media and politicians often underscore the need for tolerance within societies, for it is a means to cope with these conflicting perspectives. Tolerance is most commonly understood as the willingness to ‘put up with’ others who are different from oneself (e.g. Stouffer Reference Stouffer1955; Gibson, Reference Gibson1992, Reference Gibson2006; Sullivan et al., Reference Sullivan, Piereson and Marcus1993; Mutz, Reference Mutz2001; Forst, Reference Forst2003), implying that disapproval or objection necessitate tolerance (Sullivan et al., Reference Sullivan, Piereson and Marcus1993: 4). We, however, adopt a more inclusive definition of tolerance, expressing a friendly and trustful attitude toward other people reflected in a ‘non-negative general orientation toward groups outside of one’s own’ (Sniderman et al., Reference Sniderman, Tetlock, Glaser, Donald and Hout1989; Dunn et al. Reference Dunn, Orellana and Singh2009: 284; Kirchner et al., Reference Kirchner, Freitag and Rapp2011: 205). Following the logic of Allport (Reference Allport1958: 398) and others, it seems even more appropriate to discuss this warmer notion of tolerance in lieu of the conventional definition: ‘[T]he domain of tolerance should not apply solely to things that we oppose or dislike; rather it is proper to speak of tolerating things even when we like them [… thus] tolerance in some realms may progress all the way from endurance to outright approval’ (Chong, Reference Chong1994: 26). In this line, tolerance is often seen as a positive belief in terms of an absence of prejudice, racism, or ethnocentrism. For example, UNESCO (1995) understands tolerance as the positive recognition of human rights and civil liberties or even as ‘harmony in difference’; with difference referring to ethnic, religious, and cultural diversity. In the following, we exclusively focus on social tolerance, which is defined as the ‘willingness to live and let live, to tolerate diverse lifestyles and political perspectives’ (Norris, Reference Norris2002: 158). In contrast to political tolerance, which refers to the granting of political rights, social tolerance encompasses a general acceptance of diversity in society and of people who are different from oneself in various respects (cf. Dunn et al., Reference Dunn, Orellana and Singh2009; Ikeda and Richey, Reference Ikeda and Richey2009; Kirchner et al., Reference Kirchner, Freitag and Rapp2011: 205).Footnote 4 Against the background of increasing international migration and ethnic diversity, we restrict our analysis to social intolerance toward other ethnicities, religions, or cultural groups. According to this conceptual outline, in the following, social intolerance is defined as the disharmony between ethnically and culturally diverse groupings and the negative orientation or even objection toward such groups.

Non-violent protest and the role of intolerance: theoretical considerations

Having defined the main concepts, we now turn to the theoretical foundations of our study. As mentioned, there are theoretical arguments for both directions of a potential effect of intolerance on non-violent protest. Flanagan and Lee (Reference Flanagan and Lee2003) assume that tolerant people have a higher probability to be liberal and therefore, should be more likely to engage in unconventional political activities such as non-violent protest. This implies a negative effect of intolerance on non-violent protest behavior. Following the insights from the work on post-materialism as well as the emancipative values literature (Inglehart and Welzel, Reference Inglehart and Welzel2005; Welzel, Reference Welzel2013), there are further arguments underlining this relationship: it is generally agreed upon that more liberal and post-materialist individuals tend to be more open to social changes, and thus, should generally be more tolerant (Inglehart, Reference Inglehart1997; Flanagan and Lee, Reference Flanagan and Lee2003). Second, the more educated, the more informed, the more widely connected, and the generally well-off tend to engage more often in unconventional political action (Inglehart, Reference Inglehart1990; Norris, Reference Norris2002; Welzel, Reference Welzel2013: 217). Following Welzel (Reference Welzel2013), we further argue that tolerance represents a highly valuable attitude, which needs to be expressed through social or political actions to increase its general utility. More precisely, Welzel (Reference Welzel2013: 218) states that expressing valuable attitudes ‘fulfills an identity-building purpose that gives value-guided action an expressive utility’. This implies that the more tolerant should be more likely to actively engage in non-violent protest.

There are, however, several arguments emphasizing that intolerant people should have a higher probability to take action. First, intolerant attitudes are assumed to be highly internally consistent compared with tolerant attitudes. For example, Gibson (Reference Gibson2006: 22) argues that ‘intolerant attitudes […] have more substantial political consequences than tolerant attitudes’. Thus, intolerance should constitute a stronger basis for political behavior, as social intolerance has a higher expressive identity and probably a stronger expressive utility. People who do not accept diversity in a society and who tend to be against the equality of rights for ethnically, religiously, or culturally diverse groupings, are more willing to engage in political action on the basis of this dissatisfaction. Following this line of reasoning, intolerance is the stronger and more expressive attitude and protest should be triggered based on this expressiveness. Besides the higher expressiveness of intolerance, deprivation might also serve as a trigger, which translates social intolerance into protest behavior. Relative deprivation is defined as ‘[…] the perceived discrepancy between what people feel they want and deserve and what they get’ (Canache, Reference Canache1996: 549). This perceived discrepancy implies that the subjective evaluation of one’s own situation is most relevant for feelings of deprivation (Gurr, Reference Gurr1970: 24). Relative deprivation, thereby, can either be egoistic or fraternalistic (Runciman, Reference Runciman1966). Egoistic relative deprivation originates in an individual-level interpersonal comparison that makes an individual feel deprived compared with another individual. This interpersonal comparison is more likely to cause stress than motivation to engage in political action (Crosby, Reference Crosby1976; Walker and Mann, Reference Walker and Mann1987). In sharp contrast, fraternalistic relative deprivation relates to intergroup comparisons, that is, between the respective in-group status and the out-group status. Adapted to our research question, these intergroup comparisons might foster negative feelings toward diverse ethnic, religious, or cultural groups and result in social intolerance. Since fraternalistic deprivation is a good predictor of protest orientation (Taylor et al., Reference Taylor, Moghaddam, Gamble and Zeller1987; Walker and Mann, Reference Walker and Mann1987; Grant and Brown, Reference Grant and Brown1995), it might especially trigger the behavioral consequences of social intolerance.Footnote 5 To sum up, social intolerance should reinforce protest behavior due to its expressiveness and through the mechanism of relative deprivation. Thus, we predict a positive effect of social intolerance on individual protest behavior:

Hypothesis 1 Socially intolerant individuals will be more likely to actively engage in non-violent protest behavior.

As we know from numerous studies on political behavior, people’s political actions do not occur in isolation from their context. Individuals are decisively influenced by their surroundings (cf. Books and Prysby, Reference Books and Prysby1988). Surroundings can be wide-ranging: the prevalence of certain values or attitudes in a society is a contextual factor that potentially affects an individual’s political behavior (Almond and Verba, Reference Almond and Verba1963; Weatherford, Reference Weatherford1980; Books and Prysby, Reference Books and Prysby1988; Schwartz, Reference Schwartz2006; Welzel and Deutsch, Reference Welzel and Deutsch2012). Books and Prysby (Reference Books and Prysby1988: 221) describe three ways in which contextual effects can emerge: contextual characteristics affect social interactions, influence conformity to social norms, and structure the flow of information. These three mechanisms are not mutually exclusive; rather they all underscore that contextual effects emerge when people react on ‘contextually patterned information’ (Books and Prysby, Reference Books and Prysby1988: 221). They further state that ‘[…] through observation, interaction with others, and/or media consumption, individuals form perceptions of the context. These perceptions, in turn, should influence attitudes and behavior’ (Books and Prysby, Reference Books and Prysby1988: 225). We therefore assume that people recognize what kind of values and attitudes are prevalent in their society and react accordingly. We argue that the value orientation on a societal level has a decisive effect on individual political behavior. More precisely, the prevalence of social intolerance in a society should affect the probability for non-violent protest behavior. Following Welzel and Deutsch’s (Reference Welzel and Deutsch2012: 467) idea of an ‘elevator effect’, we argue that the prevalence of social intolerance increases people’s probability of non-violent protest behavior. That means even tolerant people – according to our reasoning in Hypothesis 1 – with a lower probability of expressing their opinion by means of non-violent protest are more likely to engage in these kind of actions in socially intolerant societies. In other words, we expect a higher overall level of protest participation in socially intolerant than in socially tolerant societies, that is, non-violent protest behavior is ‘elevated’ by the contextual climate independent of an individual’s level of social intolerance. Consequently, we can formulate the following contextual-level hypothesis:

Hypothesis 2 A climate of social intolerance within a country will lead to more active individual engagement in non-violent protest.

Going back to the assumption, which sees contextual effects as reactions to the perceived contextually patterned information, it is reasonable to argue that people might react differently to this information. An alternative to the uniform and direct contextual effect, described in Hypothesis 2, is an indirect effect pointing at the differential reaction to the value climate depending on one’s own value orientation. Thus, individual non-violent protest behavior could be explained by an interaction between the individual-level value orientation and the societal value orientation. Two competing scenarios concerning this interaction effect are possible: first, the cultural climate might strengthen the hypothesized relationship between an individual’s level of social intolerance and the respective protest participation. Welzel and Deutsch (Reference Welzel and Deutsch2012: 467f.) call this enhancement of the individual-level effect ‘the amplifier effect’. In order to justify this argument, one can draw on two closely interrelated lines of reasoning. According to social psychology research, conformity might explain the reinforcement of an individual-level effect (Asch, Reference Asch1956; Bond and Smith, Reference Bond and Smith1996; Martin and Hewstone, Reference Martin and Hewstone2007; Welzel and Deutsch, Reference Welzel and Deutsch2012). Due to normative or informational social influence, individuals conform to the opinion and judgments of the majority. Social proof is one form of informational social influence. Thus, especially in situations of uncertainty, individuals use the attitudes and behavior of the majority as reference for their own behavior (Cialdini, Reference Cialdini2001; Martin and Hewstone, Reference Martin and Hewstone2007). Regarding our argument, societal intolerance might boost protest behavior of intolerant individuals because they are influenced by the behavior of the majority. An alternative explanation of such a positive interaction might be borrowed from the spiral of silence thesis, which originates in communication science (Noelle-Neumann, Reference Noelle-Neumann1974): people who assume that their opinion is in the minority refrain from expressing this opinion, for they fear isolation within society (cf. Moy et al., Reference Moy, Domke and Stamm2001). Adapted to our argument, this means that in a socially intolerant climate, socially tolerant people remain silent and do not express their political attitudes by means of non-violent protest. This increases the gap between socially tolerant and socially intolerant individuals regarding their non-violent protest behavior. In other words, according to the adaption of the spiral of silence thesis, the positive effect of being socially intolerant on protest is thought to be strengthened. Based on this reasoning, we formulate a first conditional hypothesis describing the interaction effect between individual- and societal-level value orientations:

Hypothesis 3a A climate of social intolerance within a country will amplify the positive relationship between (individual) social intolerance and active engagement in non-violent protest.

From another point of view, namely from a rational choice perspective, it can be reasonable to assume the opposite direction of the described interaction effect. In the context of political behavior, rational choice theory states that political participation is only rational if the benefits of one’s own action are higher than the costs (Downs, Reference Downs1957; Olson, Reference Olson1965).Footnote 6 Against this backdrop, a culture of conformity on certain attitudes makes it unnecessary to take any action. Adapted to our research question, there is no need for socially intolerant people to actively engage in protest if social intolerance prevails within society. In this case, their opinion is already represented. Consequently, an alternative conditional hypothesis to Hypothesis 3a is formulated:

Hypothesis 3b A climate of social intolerance within a country will decrease the positive relationship between (individual) social intolerance and active engagement in non-violent protest.

To sum up, we argue for a positive individual-level effect of social intolerance on non-violent protest behavior (Hypothesis 1), for a positive direct contextual effect of the value orientation on a societal level (Hypothesis 2), as well as for an interaction between individual and societal-level attitudes (Hypothesis 3a and Hypothesis 3b). In the remainder of this paper, we test these hypotheses empirically.

Measurement and analytical strategy

Our analysis is based on the fifth wave of the World Values Survey, covering the time period between 2005 and 2008. We limit our sample selection to countries with a political rights index of three or lower to guarantee that democratic values, such as non-violent protest, are incorporated in the political culture of the selected countries (Freedom House, 2005). Both non-violent protest and social intolerance are basic liberal democratic principles, which are hardly found in ‘not free’ countries (Flanagan and Lee, Reference Flanagan and Lee2003; Gibson, Reference Gibson2013). In doing so, we further hold the political opportunity structure for political protest constant in our sample (see Welzel, Reference Welzel2013). Our overall sample comprises 32 countries with a total number of 33,330 respondents. For an overview of these 32 countries, see Table 1.

Table 1 Mean of non-violent protest activity and social intolerance by country

Our dependent variable is non-violent protest as a means of unconventional political participation (van Deth, Reference van Deth2009; Dalton et al., Reference Dalton, van Sickle and Weldon2010; Welzel and Deutsch, Reference Welzel and Deutsch2012). We focus only on legal and non-violent protest activities, namely signing a petition, joining boycotts, and attending lawful demonstrations. The World Values Survey offers two different questions capturing an individual’s protest activity, one is hypothetical and the other directly asks if the respondent has ever done one of the three above mentioned activities in the last 5 years. We operationalize non-violent protest based on the latter question accounting for remembered action (‘have done’ and ‘have not done’), whereby action is coded as 1 and no action is coded as 0. We construct our final dependent variable of non-violent protest based on a Maximum-Likelihood factor analysis revealing one single factor with higher values identifying a higher likeliness to actively engage in non-violent protest.Footnote 7 The country averages for our dependent variable are depicted in Table 1. The level of non-violent protest varies considerably from country to country. We find the lowest level of non-violent protest participation in Romania (0.04) and Thailand (0.04); Trinidad (0.77) and Great Britain (0.71) are the most active countries.

We capture our main explanatory variable, social intolerance, in terms of an objection to groups outside one’s own ethnicity, religion, or culture (cf. Dunn et al., Reference Dunn, Orellana and Singh2009; Kirchner et al., Reference Kirchner, Freitag and Rapp2011), with a battery of items: ‘On this list are various groups of people. Could you please mention any that you would not like to have as neighbors?’ The question covers 10 categories, whereby we only focus on the four categories identifying an ethnically, religiously, or culturally diverse group: people of a different race, immigrants/foreign workers, people of a different religion, people who speak a different language. Each item is binary coded to capture whether the respondent accepts or rejects a particular group as a neighbor.Footnote 8 Similar to the measurement of non-violent protest, social intolerance is operationalized via a Maximum-Likelihood factor analysis revealing one single factor, where higher values indicate higher social intolerance.Footnote 9 As Table 1 shows, the mean levels of social intolerance vary. The most socially tolerant society in the sample is found in Argentina [0.06], while the most intolerant society in our sample is in India [0.71].

As we are interested in both the individual and the contextual (‘ecological’) effect of social intolerance on an individual’s non-violent protest behavior, we aggregate social intolerance to receive the level of intolerance in each of our 32 countries. Moreover, we implement cross-level interactions to test how the effect of an individual’s level of social intolerance on non-violent protest behavior is decreased or amplified by the prevalence of intolerance within a country. Since our main intention is to underscore the possible consequences of intolerance on political behavior, it is not our aim to fully capture the origins of non-violent protest behavior. This task has already been undertaken by numerous studies in the field. We thus only include those control variables, which potentially confound the relationship between social intolerance and non-violent protest behavior. On the individual level we control for standard socio-economic variables, which were most commonly used in prior analyses (Dalton et al., Reference Dalton, van Sickle and Weldon2010; Welzel and Deutsch, Reference Welzel and Deutsch2012; Welzel, Reference Welzel2013). It is generally agreed upon that younger males with higher levels of education will be most likely to actively engage in non-violent protest actions, with education being one of the strongest predictors for protest activity (Verba et al., Reference Verba, Schlozman and Brady1995). As mentioned, we furthermore anticipate that post-materialist values will lead to more participation (Inglehart, Reference Inglehart1997; Inglehart and Welzel, Reference Inglehart and Welzel2005). In similar ways, active social engagement, as well as the respondent’s personal dissatisfaction with life, should trigger political engagement. It is often argued that an individual’s political ideology also plays a role in explaining protest behavior. It is thus predicted that more left-leaning individuals will be more likely to engage in non-violent protest. In international comparison, however, left and right may have different meanings and we thus refrain from including this variable, instead relying on political interest as a control for political orientation (see also Welzel, Reference Welzel2013). All control variables and their operationalizations are described in detail in the Appendix (Table A1). In addition, on the contextual level we control for ethnic diversity, the longevity of democracy as political engagement becomes differentiated with democratic experience (Roller and Wessels, Reference Roller and Wessels1996), and a country’s degree of human development (Norris, Reference Norris2009a). Our final analyses are based on linear multilevel models with random intercepts. Random slopes are further integrated into the models comprising cross-level interactions between the individual and country level of social intolerance.

Results

How does social intolerance toward ethnically, religiously, and culturally diverse groups on the individual and contextual level relate to non-violent protest participation? To address our research question, we run three linear multilevel models in a stepwise procedure: first, we inspect the individual-level relationship between social intolerance and protest behavior. In a second step, we test Hypothesis 2 concerning the direct ecological effect of social intolerance. Last, we run a random slopes multilevel model to test the interactive effect of the social intolerance climate on the relation between individual social intolerance and non-violent protest participation. The results for these three estimates are presented in Table 2.

Table 2 Social intolerance and non-violent protest – regression results

Standard errors in parentheses; DIC=deviance information criterion.

*P<0.1, **P<0.05, ***P<0.01.

Considering the results in model 1, we observe that the coefficient for individual social intolerance is positive and statistically significant, supporting our proposition of Hypothesis 1. Simply put, socially intolerant individuals are more likely to actively take part in different forms of non-violent protest. This underscores the considerations from the tolerance literature and the relative deprivation theory that, first, intolerance is a more expressive attitude and, second, that intolerant individuals express their dissatisfaction by actively engaging in non-violent protest (Gurr, Reference Gurr1970; Gibson, Reference Gibson1992). Turning to our control variables, we see that well-educated, post-materialist, politically interested, actively engaged males, and people who are quite dissatisfied with their current life situation, are most likely to participate in non-violent protest. These findings are in line with previous studies (Dalton et al., Reference Dalton, van Sickle and Weldon2010; Welzel and Deutsch, Reference Welzel and Deutsch2012).

The question arises as to whether this protest encouraging effect also applies for the contextual level. Turning to model 2 in Table 2, we see that this prediction does not hold: the prevalence of socially intolerant attitudes leads to less non-violent protest participation. Contrary to Hypothesis 2, we do not find a positive effect for a socially intolerant climate on the country level. In sharp contrast, the observed effect shows a strongly negative and significant influence on protest behavior. In other words, there is less individual protest participation in socially intolerant settings. This, however, could be a misleading relationship, as socially tolerant and socially intolerant individuals may react differently to the prevailing attitudinal climate within their country. To test this assumption, we run model 3 with a cross-level interaction between the individual-level social intolerance and the societal-level intolerance.

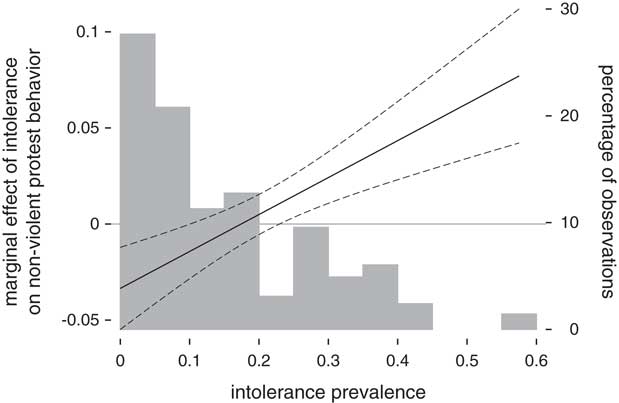

To obtain an even more precise picture of this interactive relation, the results of model 3 are graphically displayed in Figure 1. Here the solid line represents the change in the effect of individual-level social intolerance on non-violent protest behavior for different levels of the contextual social intolerance climate. The dashed lines show the 95% confidence bands revealing the uncertainty of the estimated result. Further, the distribution of the intolerance climate is given by the grey shaded area. At first glance, we observe the overall positive effect of the interaction as already given by the positive and significant interaction coefficient in model 3.Footnote 10 Upon more detailed examination, however, the Figure reveals that for around 50% of the respondents the effect of individual social intolerance on non-violent protest behavior is negative, given a highly tolerant climate in the country. In contrast, the positive relationship in model 1 is strengthened within a context of medium or high social intolerance. Here, the relationship between individual-level social intolerance and non-violent protest is strongly and significantly positive, supporting our expectations from Hypothesis 3a. But it has to be noted that for a substantial portion of our sample the interactive effect is not distinguishable from 0, for the confidence intervals include 0. It thus seems as if only in a culture of conformity, in terms of a low or high contextual social intolerance, is there an increased likelihood for both socially tolerant and intolerant individuals to actively participate in non-violent protests. While this supports Hypothesis 3a, the rational choice-based Hypothesis 3b has to be rejected. Besides our arguments on conformity and the spiral of silence, insights from the literature on intolerance and anti-immigrant attitudes might provide an alternative explanation for this result. As the high importance of cultural and symbolic concerns rather than self-interest shows, rational choice considerations seem to play a minor role when it comes to ethnic and cultural diversity (Manevska and Achterberg, Reference Manevska and Achterberg2013).

Figure 1 Marginal effect of individual-level social intolerance on non-violent protest participation by contextual social intolerance prevalence.

To sum up, our results largely confirm the propositions of Hypotheses 1 and 3a: socially intolerant individuals are more likely to actively engage in non-violent protest. This effect is thereby enhanced in highly socially intolerant political cultures (amplifier effect). The deviance information criterion, which gives the overall model fit – with smaller values indicating a better fit (Gelman and Hill, Reference Gelman and Hill2007) – further shows that the best estimates for non-violent protest in our analyses can be found in model 3. The integration of the cross-level interaction effect thus alters the accuracy of our estimates.

This interactive term further shows that the overall positive effect of the micro-level intolerance on non-violent protest is highly contingent on the context: intolerant people are more likely to protest in intolerant societies. But conversely, this means that intolerant people are less likely to protest when tolerance increases. As soon as a climate of tolerance exists, tolerant persons are more likely to express their attitudes and opinion via political protest. This result underscores our predictions from social psychology research on conformity and the spiral of silence thesis: people holding the majority opinion feel encouraged to participate in non-violent protest. Summing up, given the strong predominance of the negative macro-level effect of intolerance over its positive micro-level effect (in effect size) and the strong dependence of the latter on macro-level intolerance itself, the net effect of intolerance on protest is negative rather than positive.

Conclusion

The aim of this paper was to shed light on the consequences of social intolerance on non-violent protest. Intolerance and especially social intolerance have long been seen as one of today’s major challenges in modern civil societies. Increasing numbers of immigrants, rapidly shifting values, and growing diversity have contributed to rising levels of individual and societal intolerance (Inglehart and Welzel, Reference Inglehart and Welzel2005; Dunn et al., Reference Dunn, Orellana and Singh2009; Kirchner et al., Reference Kirchner, Freitag and Rapp2011; Gibson, Reference Gibson2013). Although prior research emphasized the importance of investigating the individual and societal outcomes of intolerance, the actual consequences have received far less attention (Gibson, Reference Gibson1992, Reference Gibson2006; Sullivan et al., Reference Sullivan, Piereson and Marcus1993; Flanagan and Lee, Reference Flanagan and Lee2003). We focused on non-violent protest participation as a possible consequence of social intolerant attitudes. Similar to tolerance, non-violent protest participation is seen as a fundamental democratic principle. Today, it is an accepted means of influencing ongoing political processes. By combing these two publicly salient concepts, we have gathered new insights on the existing research in both areas. From a theoretical perspective, the literature is undecided about this relationship. While a liberal value orientation of tolerant persons speaks for a negative effect of intolerance on protest behavior, the will to express one’s opinion speaks for an enhanced protest activity of intolerant persons. We address this puzzle by considering the contextual prevalence of intolerant attitudes as a direct as well as moderating factor.

Our results confirmed that social intolerance bears certain consequences for individual political behavior: more socially intolerant individuals are more likely to actively express their attitudes via non-violent protest participation. We explain this finding by adapting arguments of relative deprivation theory, which states that individuals are more likely to take part in protest behavior if they feel (socially) deprived (Taylor et al., Reference Taylor, Moghaddam, Gamble and Zeller1987; Walker and Mann, Reference Walker and Mann1987; Grant and Brown, Reference Grant and Brown1995). In addition, the positive relation between social intolerance and protest is further amplified if an individual lives in a country where social intolerance prevails. Within such a culture of conformity, socially intolerant individuals are even more likely to take part in non-violent protest activities. From a social psychological perspective informational social influence might be at work within this context. At the same time, intolerant individuals will be less likely to engage in non-violent protest if they live in a rather tolerant surrounding. These results are also in line with the spiral of silence thesis, arguing that people who perceive their opinion as in the minority remain silent and abstain from expressing it in public (Noelle-Neumann, Reference Noelle-Neumann1974; Moy et al., Reference Moy, Domke and Stamm2001). Overall, these diverse findings underscore the necessity to distinguish between the effects of individual-level values and their contextual effects as well as their interaction, as they may differ in their influence direction and be largely conditional on each other. With the help of the cross-level interaction, we could show that although we have a positive effect of intolerance on protest behavior, the overall effect of social intolerance is rather negative if we consider the contextual settings.

Although our results emphasize the effect of social intolerance on non-violent protest, its true causal direction may be questionable. Non-violent protest behavior, or political action in general, is often used as a possible explanation for higher levels of tolerance (see especially Peffley and Rohrschneider, Reference Peffley and Rohrschneider2003), with the assumption being that more active individuals are more open to social changes and thus will be more politically and socially tolerant (Mill, Reference Mill1984; Inglehart, Reference Inglehart1997; Peffley and Rohrschneider, Reference Peffley and Rohrschneider2003). Due to our research design, however, we are unable to fully address this causality question, as we would need panel or time-series data to solve this problem. Only against the backdrop of theoretical arguments, we can assume that behavior follows attitudes (Fishbein and Ajzen, Reference Fishbein and Ajzen1975).

In the end, one may ask what implications these findings may have for society and future research. Although the research on tolerance and anti-immigrant attitudes is growing rapidly, the question about the consequences of these attitudes remains (largely) unanswered. What if these attitudes do not result in political or social behavior? We could show that the behavioral consequences of intolerance are strongly dependent on the prevalence of attitudes in the contexts. Intolerant individuals living in intolerant contexts are more likely to participate in non-violent protest. As a consequence socially intolerant attitudes may prevail in these societies. These results should alert socially tolerant individuals living in these predominantly intolerant societies to more actively engaging in political protest or at least to more openly expressing their opinions. On the other hand, we also show that intolerant people are less likely to protest when tolerance increases. Thus, tolerant attitudes might be further strengthened in these contexts. This is good news regarding the anchoring of tolerant attitudes in modern, enlightened societies.

Acknowledgements

The article was prepared within the framework of a subsidy granted to the HSE by the Government of the Russian Federation for the implementation of the Global Competitiveness Program. An earlier version of the article was presented at the 3rd International Annual Research Conference of the Laboratory for Comparative Social Research (LCSR) 2013 in Moscow, Russia, and at the DVPW Comparative Political Science Section Conference 2015 in Hamburg, Germany. The authors would like to thank the participants of both workshops, the three anonymous reviewers as well as Matthias Fatke and Jennifer Shore for very helpful comments and suggestions concerning the manuscript. Errors remain their own. Both authors contributed equally to the article.

Appendix

Table A1 Variables overview