Introduction

The use of Information and Communication Technologies (ICTs) in political contention is increasingly common today [e.g., Bennett and Segerberg Reference Bennett and Segernerg2013; Bimber, Flanagin, and Stohl Reference Bimber, Flanagin and Stohl2005; Earl and Kimport Reference Earl and Kimport2011. For general discussions, see Earl, Hunt, and Garrett Reference Earl, Hunt and Garrett2014; Garrett Reference Garrett2006]. While protestors in Egypt and Tunisia largely adopted Facebook and Twitter in organising street demonstrations and raising local and global awareness of the latest events during the Arab Spring [e.g., Howard and Hussain Reference Howard and Hussain2013; Huang Reference Huang2011], Hongkongers primarily relied on WhatsApp and Facebook when assembling on the street and venting their anger and frustration at Beijing as part of the Umbrella Movement [Lee and Chan Reference Lee and Chan2018: 110]. Why, then, during the political turbulence, did Egyptians and Tunisians depend less on WhatsApp, “the most favoured social tool in the Arab world” [AG Reporter 2015]? Similarly, why did Hongkongers not use YouTube in their civil disobedience campaigns, even though YouTube had enjoyed spectacular growth in Hong Kong [Woodhouse Reference Woodhouse2015]?

To date, much ink has been spilled in analysing the use of ICTs in political contention, i.e., non-routine and diversified forms of collective action that bring “ordinary people into confrontation with opponents, elites, or authorities” [Tarrow Reference Tarrow2011, 7-8]. While extant scholarship yields a nuanced picture of how people have used ICTs during various contentions, there is more to the story than just looking at the use of specific digital communication technologies. In reality, ICTs were not “born” to be used in and for political contention. Rather, people have appropriated and manoeuvred them—some but not others, as we see from the cases of the Arab Spring and the Umbrella Movement—for such purposes, in specific contexts. Consequently, exploring the reasoning behind people’s strategic or tactical understandings, choices, and uses of specific (functions of) ICTs helps clarify the particular mechanisms that lead to ICTs becoming part of these protestors’ repertoires of contention [Tilly Reference Tilly1995]. This process unveils “the microfoundations of political action” by expounding upon the perspective of agency [Jasper Reference Jasper2004: 4] that transforms affordances [Gibson Reference Gibson1966] of given technologies into aspects of the contentious repertoire. In other words, the answer lies at the heart of the research question in this study: How, and under which circumstances, are decisions made to use ICT(s) as the repertoire of contention, with the affordances being the basis that structures the possibilities of using the technology? This study advances understanding of how ICTs as the repertoire of contention are created and developed, with (certain functions of) mobile phones being a part of the protest repertoire in contemporary China as the case.

In the following sections, the study begins with a review and a theoretical grounding that elucidates the relevant, yet rarely addressed, link between affordance and repertoire of contention. Second, it elaborates the method used, including cases, data collection, and methods of analysis. Third, the study unravels the issue as to why people employ certain functions of the mobile phone but not others within their protest practices. The process of strategically choosing which functions of their mobile phones the protesters used in the process of contention is shaped by a confluence of individuals’ habitus of media use that manifests particular affordances and the learned experience of the contested means of the past in mass media. Fourth, the study concludes with thoughts on encouraging a further investigation of the link (or “gap”) between affordances and repertoires of contention.

Affordances and Repertoires of Contention: A Clarification of Controversial Issues

Among studies that explore the role of ICTs in political contention, the dissection and analysis of affordances has emerged as a relevant issue for consideration [e.g., Earl and Kimport Reference Earl and Kimport2011; Bennett and Segerberg Reference Bennett and Segernerg2013; Enjolras, Steen-Johnsen, and Wollebæk Reference Enjolras, Steen-Johnsen and Wollebæk2013]. Nevertheless, the inconsistency and, in some cases, inappropriateness of the use of the term “affordance,” first coined by Gibson [Reference Gibson1966], complicates the understanding of the possible effects that ICTs might have on social movements. Some take the technology-oriented perspective to address the importance of the material aspects of communication technologies. Largely following Norman’s [Reference Norman1988] definition, Earl and Kimport regard affordance to be “the type of action or a characteristic of actions that a technology enables through its design” [2011: 10].Footnote 1 Along similar lines, researchers employ phrases such as “the affordances of blogging technology” [Graves Reference Graves2007], “social media affordances” [Enjolras, Steen-Johnsen, and Wollebæk Reference Enjolras, Steen-Johnsen and Wollebæk2013: 891; Christensen Reference Christensen2011], “affordances of particular social media technologies” [Selander and Jarvenpaa Reference Selander and Jarvenpaa2016: 333], “Facebook affordances” [Kaun and Stiernstedt Reference Kaun and Stiernstedt2014], “the technological affordances of Facebook” [ibid.], and “affordance of Twitter” [Jacobson and Mascaro Reference Jacobson and Mascaro2016; Ogan and Varol Reference Ogan and Varol2016], to mention a few. Others treat the term rather as the potential outcome of ICT use in social movements. For instance, Dahlberg [Reference Dahlberg2011] and Goggin [Reference Googin2013] discuss the “democratic affordances” offered by digital media. Mercea [Reference Mercea2013] explains “horizontal collaboration” as an affordance of social media.

Yet, as Evans, Pearce, Vitak, and Treem [Reference Evans, Pearce, Vitak and Treem2017] point out, affordance is neither a feature of the technology nor an outcome. The outcome-oriented perspective ignores affordances as “constant properties” [Gibson Reference Gibson1977: 285] independent of the goals of the actor [Michaels Reference Michaels2003: 136-137]. In contrast, the technology-oriented perspective uses “language that talks about the affordances of or offered by specific technologies […] and positions the affordance as inherent in use based on some material aspects of the technology;” it fails to acknowledge “the agency present in [the use of] technology” [Evans et al. Reference Evans, Pearce, Vitak and Treem2017: 39, emphasis in original]. In the same vein, Cooren [Reference Cooren2018: 281; emphasis in original] argues, “[p]roperties [of materiality] are never absolutely proper or intrinsic to their bearers, as they are the result of appropriations or attributions.” Nevertheless, contemporary scholars write as though people are unambiguously using Facebook, Twitter, or social media in a straightforward manner that is structurally determined by the communication technologies as such. The technologically-oriented tendency carries the danger of a media-centric, techno-centric or technologically deterministic logic, implying that communication technologies will necessarily lead to, for instance, a homogeneity in use [for a critique in the case of the internet, see Hargittai and Hinnant Reference Hargittai and Hinnant2008]. Parchoma [Reference Parchoma2014: 361, emphasis added] untangles the issue, stating that “affordances neither belong to the environment nor the individual, but rather to the relationship between individuals and their perceptions of environments.” Following this argument, affordance entails a relational nature between the actor and the technology in a specific context [for a similar discussion, see Cooren, Reference Cooren2018], which thereby underlines a three-fold consideration of “the attributes and abilities of users, the materiality of technologies, and the contexts of technology use” [Evans et al. Reference Evans, Pearce, Vitak and Treem2017: 36; see also Davis and Chouinard Reference Davis and Chouinard2016]. In our case, the consideration of affordances in the study of ICTs and contention postulates not only a discussion of the particular material features of (mobile) technology but, more importantly, ideas about the specific perceptions of the selection and use of technology for contentious activities by various users in different contexts.

If affordances imply the possible uses of technology, then “repertoire of contention” functions as a key term in understanding the choice and actualisation of some of the possibilities for action in contention. As Tilly [Reference Tilly2005: 41-42] writes,

The word repertoire identifies a limited set of routines that are learned, shared and acted out through a relatively deliberate process of choice. Repertoires are learned cultural creations, but they do not descend from abstract philosophy or take shape as a result of political propaganda; they emerge from struggle […] At any particular point in history, however, they learn only a rather small number of alternative ways to act collectively.

Therein lies the significance of the contentious repertoire. As a delimited array of contentious claims-making practices and performance, the repertoire in essence is situated in a complex mesh of multifaceted conditions of the moment [Rodríguez, Ferron, and Shamas Reference Rodríguez, Ferron and Shamas2014]. For one thing, structural factors, such as regime type, the history of contention, and changes in political opportunity, have significant bearing on repertoire selection [Tarrow Reference Tarrow2008: 237-239]. For another, people not only closely monitor changes in the political environment, but they also consciously interpret the actions of others. A repertoire of contention hence “[…] calls attention to the clustered, learned, yet improvisational character of people’s interactions as they make and receive each other’s claim.” [Tilly and Tarrow Reference Tilly and Tarrow2006: 16]

It is highly relevant to keep in mind that, as Tarrow emphasises, “[…] the repertoire is not only what people do […] it is what they know how to do and what others expect them to do” [Reference Tarrow1993: 283], emphasis in original]. To explore Crossley’s definition [Reference Crossley2002b: 49], a repertoire involves “a tacit recognition of the know-how or acquired competence involved in specific forms of protest.” This “tactical question,” as van Laer and van Aelst [Reference Van Laer and van aelst2010: 1151] concur in their discussion on the internet and movement repertoires, “is critical for social movements.” Subsequently, in the discussion on the development of the contentious repertoire, it is important to focus not only on which contentious tactics or strategies people adopt or appropriate. Instead, we must also expand on people’s understanding and choice of specific actions, or, more precisely in this study, the perception or know-how of using ICTs—some but not others—as a means of protest.

To better understand people’s perceptions, it is helpful to invoke the suggestion of an integration of Bourdieu’s [Reference Bourdieu1984] notion of habitus as a way of contextualising the discussion on repertoire selection. For Bourdieu’s original idea,

The habitus is a set of dispositions, reflexes and forms of behaviour people acquire through acting in society. It reflects the different positions people have in society, for example, whether they are brought up in a middle-class environment or in a working-class suburb [2000: 19, emphasis added].

In the sociology of movements, Crossley [Reference Crossley2002b: 52] contends that, “[t]he concept of habitus allows us to reflect upon and explore the way in which agents’ life experiences and trajectories shape the dispositions and schemas which, in turn, shape the ways in which they choose from the repertories of contention that prevail within their society.” [See also Crossley Reference Crossley1999, Reference Crossley2003; Haluza-DeLay Reference Haluza-DeLay2008; Husu Reference Husu2013: 265.] More specifically, people develop “perceptual and linguistic schemas, preferences and desires, know-how, forms of competence and other such dispositions” [Crossley Reference Crossley2002a: 171-172] over the course of their lives. In particular, learning in and through contentious movement activities should facilitate a transformation of the habitus of protest participants through “a deepening internalization” of new dispositions and experiences into tacit knowledge of the contentious repertoire [Haluza-DeLay Reference Haluza-DeLay2008: 212]. Meanwhile, “activists’ statuses, skills and social connections all shape their possibilities for protest and this is reflected in their different ways of doing so” [Crossley Reference Crossley2002a: 132]. Consequently, the involvement of habitus “opens up the question of the manner in which activist choices (of repertoire amongst other things) are shaped by activist histories […] [and], analytically, the procedures and methods of practical reasoning that structure those choices” [Crossley Reference Crossley2002b: 52].

Furthermore, Crossley draws attention to the notion that “repertoires are not so much forms of action as of interaction, […] [which] connect and belong to sets of actors” [Reference Crossley2002b: 49, emphasis added]. That is, to use Tilly’s original statement,

The action takes its meaning and effectiveness from shared understandings, memories, and agreements, however grudging, among the parties. In that sense, then, a repertoire of actions resembles not individual consciousness but a language; although individuals and groups know and deploy the actions in a repertoire, the actions connect sets of individuals and groups [1995b: 30, emphasis added].

Hence, the contentious repertoire helps articulate the identity of participants in contentious activity or, in other quarters, evolves into the construction of the identity of the agent producing it. Against this backdrop, individuals and groups consolidate further through the deployment of specific contentious repertories with defined meanings and effects.

The above discussion on extant scholarship with respect to two key conceptions—affordance and repertoires of contention—acknowledges a similarity between the two. Both terms entail not essentialism but relationality. As noted, on the basis of the original Gibsonian view, affordance exists in the relationships between artefacts, active agents (users and designers), and their context [Davis and Chouinard Reference Davis and Chouinard2016: 242]. Repertoires emerge and evolve, by the same token, in relationship with structural variables, the habitus and trajectory of agency, and the cultural context in which they originate. The same repertoire of possible actions may not be adopted or used in the same way in different contentious environments for reasons other than communication technology per se.

Linking Affordances to Repertoires of Contention

Although the notion of affordance and the development of a contentious repertoire, as described above, form part of various discussions, the connection between them remains obscure. For a better understanding of the linking or transformation from affordance to the development of a contentious repertoire, along with a consideration of the habitus, the following diagram sheds light on the deployment of ICTs in political contention (Figure 1).

Figure 1 The relationship among affordance, habitus, contentious repertoire, and use

First, given its relational nature, the affordances of communication technology may differ or vary significantly among different agents, and across different contexts. As discussed above, affordances are possibilities and opportunities for action that emerge from agents engaging with a certain property of technology in a specific context. As such, the same communication technology would therefore denote different meanings and result in dissimilar uses for different people in diverse cultures. There are, for example, significant differences in the utilisation of social media [Egros Reference Egros2011] or the internet [Hermeking Reference Hermeking2005; Hargittai and Hinnant Reference Hargittai and Hinnant2008] among different demographics, and across divergent cultures or countries.

Second, as illustrated in Figure 1, the contentious repertoire essentially develops from—and hence is confined to—the defined affordance(s) of communication technology in a given context. More specifically, affordance underpins “the practical constitution of repertories” via “the activities of everyday life” [Crossley Reference Crossley2002b: 49]. That is, contentious repertoires grow out of affordance and as “a by-product of everyday experiences” [Della Porta Reference Della Porta2013]. For instance, the barricade emerged as an aspect of the protest repertoires developed during the French Revolution as a result of the routine and everyday practice of “neighbourhood protection” in 16th century Paris [Traugott Reference Traugott1993]. Protestors simply chose their protest repertoire from (certain affordances of) the available stock. In this sense, the affordances of communication technologies in everyday life in a given context offer preconditions for possible use of these technologies in contentious activities, but do not imply or guarantee that these repertoires will emerge. As the repertories of contention grow out of people’s habitus, a careful investigation of people’s routine attitudes and practices with (certain) ICTs is essential for the depiction of its affordances.

Furthermore, affordances are a necessary but not sufficient precondition for the development of repertoires of action. In other words, affordance does not equal repertoire, and not every affordance will transfer into the contentious repertoire. Rather, contentious practices encompass a deliberate but constrained selection of actions within the repertoire by agents. In this sense, the transformation from affordances (i.e., the possibilities inherent in the use of a specific technology), to the development of a repertoire of contention (i.e., the possibilities of technology used as a part of the contentious claims-making practice and performance), embodies strategic choices that people as agents make in contention. A careful consideration of both structural factors and issues of agency thus untangles the key issue of the selection of repertoires, or variations in these repertoires as they appear in contention in different parts of the world as demonstrated at the beginning of this study. By doing so, we probe “the social dynamics of the processes by which agents and groups select from that repertoire” [Crossley Reference Crossley2002b: 51].

Third, contentious repertoires, once established, may constrain further, innovative transfers from other affordances to repertoires. In other words, once an affordance becomes part of a repertoire of contention, people may get used to it, making it difficult to innovate new uses or strategies. Once labelled––as was the case of the so-called “Facebook Revolution” or “Twitter Revolution”––protest repertoires tend to overshadow and limit the affordances of the medium. The possibilities and opportunities of digital communication technologies such as Facebook or Twitter are transformed and reified by a narrow, specific, and repeated use in certain circumstances. This may stifle further transformation of other possibilities from affordance to repertoire, consequently restraining the diversification of possibilities for contentious use.

To sum up, the narrow focus on the actual use of ICTs in contention, valuable though it might be for people’s practices of contention, fails to grasp the dynamic possibilities of human agency. Furthermore, it overlooks political and social complexity in favour of a stereotypic rendering of communication technologies. Particular attention should be given to expanding and supplementing empirical research into the investigation of affordances and the establishment of repertoires of contention. The main research questions (RQs) state as follows:

RQ1: What are protesters’ perceptions of ICT(s) as the repertoire of contention, and under which circumstances do they view ICT(s) as the repertoire of contention?

RQ2: What are protesters’ routine practices with ICT(s) that exemplify the affordances of ICT(s) for specific individuals or groups in a given context?

RQ3: How does the transformation from affordances to the repertoire of contention occur?

Method

This study employs a case study design with the heuristic purpose of theoretically exploring [Vaughan Reference Vaughan, Charles and Becker1992] people’s perceptions of ICTs—more precisely, mobile phones—and their subsequent uses in political contention in China. The impact of ICTs on contentious action has emerged as an enduring and substantial focus in the studies of ICTs in China [e.g. Esarey and Xiao Reference Esarey and Xiao2011; Yang Reference Yang2009]. In particular, the ubiquitous use of mobile communication exerts a growing influence over people’s social and political practices, with the increasing use of the mobile phone functioning as an efficient tool for aggregating and articulating citizen input or popular discontentment during the process of public opinion formation and political participation [e.g., Liu Reference Liu2016]. In this study, a case refers to an example of “a class of phenomena” [Flyvbjerg Reference Flyvbjerg2006: 220], i.e., a mobile-facilitated political contention. To present a nuanced picture of people’s perceptions of mobile phones and their subsequent uses in contention, this study examines six cases: the anti-Para-Xylene (“anti-PX” for short) protests in Xiamen in 2007, Ningbo in 2012, Chengdu and Kunming in 2013, and the taxi driver strikes in Fuzhou and Shenzhen in 2010. Concerning people from different geographies and professions, these cases involve the adoption of ICTs––in particular, mobile phones––as an indispensable means of political activism. As early as 2007, people largely relied on mobile communications to organise the anti-PX protest in Xiamen [Liu Reference Liu2013]. In subsequent protests in, for instance, Ningbo [Liu and Yan Reference Liu and Yan2012] and Chengdu [Chang Reference Chang2013], people continued to exploit various functions of mobile phones, such as text messaging and WeChat, to galvanise protests, with protestors sharing information and protest plans, and facilitating collective action mobilisation. The Fuzhou strike of 23 April 2010 arose in response to a surge in police-issued penalties [China Daily 2010]. A similar strike in Shenzhen at the end of October 2010 [eChinacities.com 2010], involved over 3,000 taxi drivers taking part in a three-day strike in protest of the government’s failure to address the problems of suburban drivers and the city’s inequitable cab fare structure. All strikes were organised largely through mobile phones. The diversity of cases offers insights into underexplored phenomena and helps “[…] refocus future investigations” [Yin Reference Yin2018: 97].

On the basis of these cases, the study used snowball sampling and interviews with protest participants to explore their perceptions and uses of the mobile phone, or of certain of its functions, as part of a repertoire of contention. The sample was drawn from interviews with 53 respondents from the cases, 48 of which were conducted face-to-face, and 5 via Gmail due to concerns regarding government surveillance of Chinese social media and e-mail communication. A summary table of respondents from each case is shown in Table 1. The sample covered a range of professions including journalists, editors, graduate students, high-school students, lawyers, sales representatives, consultants, university lecturers, taxi drivers, IT professionals, mobile phone salespersons, barbers, and small clothing storeowners.

Table 1. Summary table of interviewees.

The interviews follow Flanagin, Stohl, and Bimber’s [Reference Flanagin, Stohl and Bimber2006: 39] suggestion to explore “what people are doing, how they are relating to one another, and what opportunities are afforded them, and from these, examining what organisation and structure fit their behaviour and help facilitate collective action.” The interviews began by reconstructing the interviewee’s personal background and experience of mobile phone use, before moving on to their description of experiences during the event, and their self-reflections on the perception of mobile phones. In particular, the interview delved into how the interviewees knew and perceived mobile phones as a means of struggle, what kind of experience or knowledge they had for the protests, where this experience or knowledge came from, and how it was gained, justified, and validated.

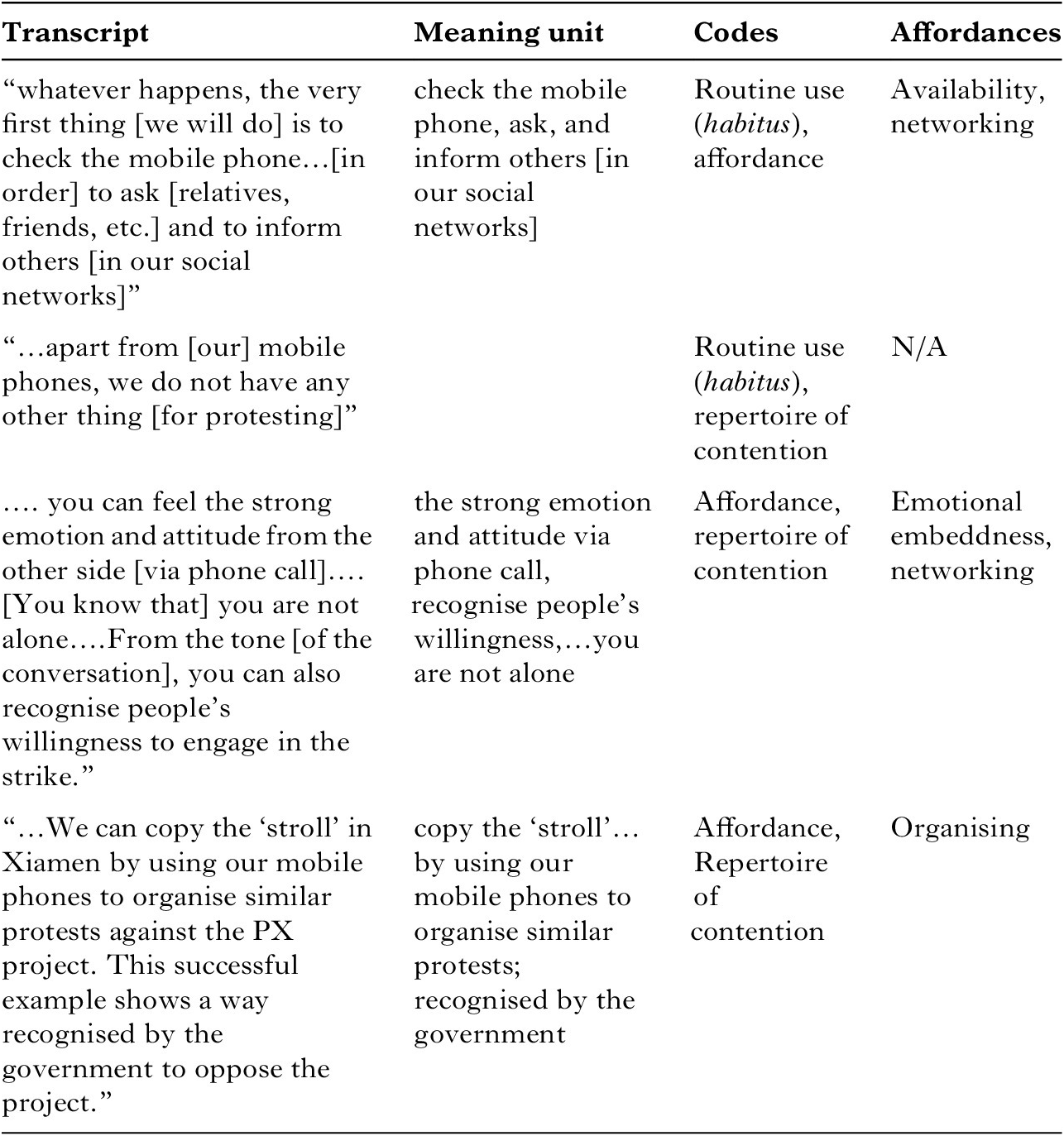

The interviews were conducted in Chinese for a duration of 1.5 hours on average, and were then transcribed and translated into English. We adopted qualitative content analysis with a directed approach [Hsieh and Shannon Reference Hsieh and Shannon2005: 1281-1283] in terms of the framework in Figure 1 and the RQs as the analytical structure. The directed approach not only offers a structured process for the analysis of empirical data, but also allows possible theory extension and refinement [ibid.: 1283]. Two researchers read the transcript independently and highlighted all text representing a meaning unit [Graneheim and Lundman Reference Graneheim and Lundman2004: 106]. They categorised all meaning units deductively using predetermined codes, which include 1) routine use (that illustrates affordance and habitus) and 2) use and perception of the mobile phone as a means of protest, i.e., repertoire of contention. They then reread, identified, and grouped affordances according to their similarities inductively. Consequently, the transcript was merged into predetermined categories, and then from categories to themes of affordances, until no further important or relevant data remained to be coded. Field notes were integrated into the analysis and key statements underlined to identify explanations that illuminate the research questions. Coding examples are illustrated in Table 2.

Table 2. Examples of transcripts, meaning units, codes, and affordances.

Mobile Phones as Repertoire of Contention: Uses and Perceptions

This section presents a discussion of the interviews that probe the different uses and perceptions of mobile phone as a means of protest during a moment of political contention (i.e., RQ1). Interviewees considered and underlined the mobile phone as the “only” resource available for them to express and aggregate their discontentment with the authorities. We found that mobile communication led for the most part to the diffusion of information related to political contention. For all interviewees, mobile communication—including mobile calls, text messaging, and WeChat—functions as the primary means of receiving and circulating contested information. Mobile communication is also important for exchanging information about protests, and for shaping the understanding of mobile phone use as part of a repertoire for action. Equally important, we observed a significant difference in the specific mobile phone functions that interviewees in different cases adopted or relied on in protests.

First, people considered their mobile phones as the most readily—and often the only—available resource for acting against the authorities, even for those with limited technological know-how (e.g., taxi drivers). In the series of anti-PX protests, for instance, residents stated that local media neither covered their concerns over the PX project nor aired their arguments against the government’s decision. Rather, local media simply criticised the opposition to the construction of the PX project, referring to their messages as mere “rumours” that misled the public [e.g., Reporter 2007]. Against this backdrop, people turned to their mobile phones, “the only available means” (emphasis added) as described by several interviewees, to obtain support from their social networks. Similar situations occurred in other protests and strikes. As one taxi driver conceded, “[…] apart from [our] mobile phones, we do not have any other thing [to fight against the authorities]” (personal communication with a 35-year-old taxi driver, October 20, 2010).

Second, mobile communication encourages the circulation of alternative information on politically sensitive topics in society, especially those with contested or controversial contents that have been suppressed or restricted by the authorities. For instance, in the Xiamen anti-PX case, all interviewees acknowledged that they first heard the term “PX” and the controversial information surrounding it via mobile text messaging. The message ran rampant within a short period of time, while, according to a 35-year-old taxi driver, “local media did not mention this issue at all for over three months” (personal communication, October 5, 2010). Mobile texting helped facilitate face-to-face conversations on the issue. The phrase “did you receive the [PX-related] Short Message Service (SMS)?” reportedly became the opening remark when Xiamen residents met each other between March and May of 2007, the period during which popular discontent grew [Zhu Reference Zhu2007, A1].

The various taxi driver strikes followed a similar pattern. However, here, mobile calls functioned as the central means for taxi drivers to exchange information regarding the government’s inaction as well as their discontentment towards the authorities. All interviewees emphasised the relevance of mobile calls and conversations for maintaining contact with “fellow drivers” and receiving update-to-date messages regarding the progress of the situation.

The above cases involved a relatively homogeneous use of mobile phone functions—either text messaging or phone calls—in receiving and spreading controversial information. Later anti-PX protests, however, saw the adoption of various forms of digitally, or mobile mediated, communication for the same purpose. In the cases of Ningbo, Kunming, and Chengdu, local residents mostly resorted to mobile-based instant messaging apps, QQ and WeChat, to disseminate PX-related information, inform their social networks, and initiate discussions. At the same time, as in the other cases, the mass media did not cover the issue at all. In short, mobile communications offer people “a broader autonomy” [Della Porta Reference Della Porta2013: 2] from the official, mass communication in receiving and spreading alternative information.

Third, apart from the circulation and diffusion of relevant information, people used messages for the purpose of mobilisation–––either to come for a “stroll,” a euphemism for street demonstrations in anti-PX protests, or to “drink tea,” which was the code used for mobilising strikes in the taxi driver protests. These were spread via internet-based platforms such as QQ, online forums and, most often, voice calls, text messaging, and WeChat accessed on mobile phones.

In reality, participants in different cases adopted and appropriated different mobile phone functions for this same purpose. In the Xiamen case, mobilising messages were predominantly sent via mobile text messaging, even in the face of local government suppression. In later anti-PX cases, calls for protests expanded via other channels such as WeChat, Weibo, and mobile messaging, which became a key part of the mechanism of mobilisation [e.g., BBC 2014; South China Morning Post 2012]. The cases of taxi driver strikes bear a strong resemblance to the anti-PX protests, with mobile phones as the key resource for the diffusion of mobilising initiatives. Yet, in their strikes, taxi drivers saw a specific mobile technology function—the voice call—as the dominant, or only, means for the dissemination of mobilising calls. All taxi drivers depended on mobile calls to exchange messages regarding the planning and implementation of the strikes. In practice, mobile calls enabled them to share strike initiatives while driving. As one driver said, “[…] Texting creates a lot of visual distraction [while driving], let alone distributing emails or chatting via online instant messaging platforms (e.g., QQ). But driving while talking is easy and convenient. For us, the earlier [we mobilise], the better” (personal communication with a 34-year-old taxi driver, April 25, 2010). Using mobile phones to call for strikes thus became a convenient, flexible, and practical way for taxi drivers to mobilise collective action “[…] while driving and looking for passengers” (personal communication with a 34-year-old taxi driver, April 25, 2010).

After receiving these controversial and mobilising messages via mobile phones, protesters often moved to search engines, microblogging sites, and online forums to look for further information on politically sensitive issues. There, again, mobile communication became a key channel for the newly mobilised individuals to spread further detailed information that they found on different digital platforms, i.e. learning from previous protests concerning the same issues [Liu Reference Liu2016].

For example, the interviewees reported that they learned much from anti-PX protests in other cities as soon as they searched keywords such as “PX” using search engines such as Baidu. They then exchanged that information within their mobile social networks, reading and learning from these past experiences. While the protest in Xiamen remained “the most renowned anti-PX protest,” according to a 27-year-old mobile phone salesperson from the Chengdu case, it was through the mobiles phone that people could easily and quickly retrieve news, photos, and videos about later protests in other cities, from web pages, microblogging, blogs, and online forums, despite government attempts at censorship.

To sum up, people treat—and hence rely on—their mobile phones as the only available means for articulating resources against the authorities. Mobile communications subsequently function as a crucial channel for the diffusion of protest information, which includes alternative information about contested issues, mobilising messages, and past coverage and experiences of protests. Such information substantially shapes people’s perceptions about what protest actions are possible, and helps people develop their own protest repertoires, thus laying the foundation for further contention. Yet, it is important to note a diversification of mobile phone uses as a repertoire of contention. To understand the reason behind such phenomena, we turn to an examination of people’s routine practices with respect to the mobile phone.

Habitus, Affordances, and Learning: Why Certain Functions But Not Others

At the beginning of this study we asked why Egyptian protesters chose Facebook and Twitter while, in contrast, Hongkongers drew their strength from Whatsapp. Similarly, why did people in the anti-PX cases take advantage of multiple functions of their mobile phones, starting with text messaging, photo-taking (during protests), WeChat and QQ to document and facilitate protests, while taxi drivers in different cities primarily relied only on voice calls during their strikes? In other words, why do some people adopt certain functions of the mobile phone but not others as part of their contentious repertoire? This question will be explored in this section, in two parts: (a) affordance, observed through habitus [Crossley Reference Crossley2002b: 57], shapes repertoire choice (i.e., RQ2), and (b) learning through contentious movement activities modularises and legitimises repertoire selection, consequently turning earlier protest experience into a tacit knowledge of the contentious repertoire (i.e., RQ3).

Habitus, Affordance, and Formation of the Contentious Repertoire

As discussed above, protesters’ contentious repertoires grow out of their habitus or, more precisely, routine practices with ICT(s) that exemplify the affordances, i.e., the relational understanding of specific communication technologies to certain agents against a particular context. An interrogation of habitus related to mobile phone use hence reveals the general affordance of mobile phones to participants in all cases, but it also demonstrates distinct types of affordances among different groups.

Generally speaking, the roots of mobile phone use as a readily available protest repertoire are to be found, first of all, in the widespread availability of mobile phones as a simple yet substantial necessity for everyday life. The affordance of availability [also see Schrock Reference Schrock2015: 1236-1237] indicates that both the artefact, i.e. the mobile phone, and its user, are an always-on resource. Notably, all interviewees shared more or less the same understanding of the mobile phone: “whatever happens, the very first thing [we do] is to check the mobile phone… [in order] to ask [relatives, friends, etc.] and to inform others [in our social networks]” (personal communication with a 36-year-old accountant, July 5, 2013). Availability establishes a taken-for-granted perception of the individual’s connections via mobile communication in everyday life [Ling Reference Ling2013]. In other words, people have become used to connecting and being connected, communicating and being communicated with, activating and being activated through their mobile phones, anytime and anywhere.

Availability also entails the easy-to-use features of mobile technology that allow people to engage with their social networks limited effort. A 23-year-old graduate from the Kunming case said that she had forwarded a message via WeChat to her entire class and to her relatives, a total of 75 people, by “[…] just twiddling the thumb” (personal communication, June 2, 2013). In the Xiamen case, the peak of the anti-PX movement occurred as “millions of Xiamen residents frenziedly forward[ed] the same [mobilising] text message around their mobile phones” [Lan and Zhang Reference Lan and Zhang2007], urging each other to join a street protest opposing the government’s PX project. Easy-to-use mobile devices with inexpensive (or “zero-cost”) telecommunication fees became the key facilitator—be it through text messaging, mobile-based QQ, or WeChat—in diffusing mobilising calls to as many people as possible.

Moreover, due to the unavailability, or lack of institutional support and resources for political contention within China’s unique institutional context and authoritarian control, people were used to the limited available resources—in this case, their mobile phones, a means of habitual communication—for receiving and circulating alternative or contested information against the authorities. Availability therefore institutes the adoption of mobile phones, a quotidian, habituated tool, for the “improvisation” [Tilly Reference Tilly1986: 390] of political activism.

It is nevertheless not the mobile phone in a general and abstract sense, but rather its specific functions that help build the contentious repertoires of divergent populations in different contexts. A close observation of variations in repertoires in different cases (Table 3) reveals that, even though mobile technology per se is the same, given its distinctive affordances to disparate social groups that can be detected through the habitus of agents, protest repertoires differ significantly case by case.

Table 3. Variations in contentious repertoire and their corresponding, distinctive affordances.

Affordances of Immediacy and Emotional Embeddedness in the Taxi Driver Strikes

For taxi drivers, the mobile phone affords the voice call as the most convenient way of talking to each other and keeping in contact with their social networks in daily life. This is especially true given the danger or impracticality of the driving-while-reading—let alone texting—practice. These interviewees rarely mention functions other than voice calls in their work routine. Calling and chatting on mobile phones consequently came to be the habitus of taxi drivers.

In practice, voice calls involve affordances of immediacy and emotional embeddedness that taxi drivers take advantage of during strikes. Immediacy refers to synchronous or real-time interaction and feedback, which brings instant confirmation of participation and hence improves the self-perceived effectiveness of organising and mobilisation. Of particular significance is that taxi drivers clearly recognised the difference between voice calls and other functions like text messages, and regarded the former as a more “effective means of mobilisation.”

Although a text message arrives at its destination almost instantaneously, this form of transferring information does not guarantee an immediate response, which compromises the self-perceived effectiveness of the intended mobilisation. That is to say, possibly delayed replies due to the asynchronous interactions inherent in text-messaging dramatically hinders participant motivation due to the uncertainty engendered around the effectiveness of the mobilisation effort. As another interviewee noted, “[…] without response from [the text message recipient], you have no idea about whether the mobilisation message has been received, read, or accepted… you have no idea who, or how many people, will join the strike. How could you decide [to join the strike if you weren’t sure who else would be joining]?” (personal communication with a 43-year-old taxi driver, April 25, 2010).

The synchronous voice call, on the contrary, invites immediate interaction as soon as the connection is established, consequently creating “a feeling of greater propinquity” [Walther Reference Walther1992] with others. The instant connection and conversation with the feeling of propinquity guarantees the effectiveness of the transmission of the mobilising message, fundamentally lowering the uncertainty inherent in organising high-risk collective resistance [McAdam Reference McAdam1986] under authoritarian regimes like that of China. Immediate confirmation via phone call therefore encourages more recruitment practices. As one striker recalls, “when I got my friend’s confirmation, it made me confident [about the organisation of the strike]… Right away, I made another call to invite one more friend” (personal communication with a 36-year-old taxi driver, May 13, 2013). In actuality, by establishing a connection quickly and efficiently, transferring mobilising messages via voice call results in a higher rate of success for the mobilisation of collective action.

No less importantly, voice calls elicit the affordance of emotional embeddedness—that is, the articulation and expression of people’s emotions through vocal elements such as tone, pitch, and volume. These elements easily generate a sense of cohesion and solidarity, and they invite political engagement. One driver stated that, when drivers were calling and speaking with each other regarding the strikes,

[…] you can feel the strong emotion and attitude from the other side [via a phone call], including the grievance of unfair treatment by the police and the anger over the government’s inaction. Such feelings resonate with your own experience… [You know that] you are not alone… From the tone [of the conversation], you can also recognise people’s willingness to engage in the strike. It really makes you feel empowered for emotional togetherness [about the strike]” (personal communication with a 43-year-old taxi driver, April 25, 2010).

As the interviewee elaborates here, vocal communication expresses, transfers, and articulates the communicator’s feelings and emotions [Scherer, Johnstone, and Klasmeyer Reference Scherer, Johnstone and Klasmeyer2002]. While most forms of mobile communication—such as text messages and email—have reduced social interactions to the barebones transfer of textual elements, speaking through the mobile phone establishes “live interactions with human beings.” Emotion has long been recognised as a key driving force in motivating passionate movement action [e.g., Aminzade and McAdam Reference Aminzade and McAdam2002; Goodwin, Jasper, and Polletta Reference Goodwin, Jasper and Polletta2009] and, for this reason, promotes engagement in strikes.

While vocal interaction unfolds and evokes a large degree of emotion, the articulation of emotions and feelings functions as an essential component of collective mobilisation: it involves shared experiences of empowerment and collective effervescence, which greatly affect the transformation “[…] from framed emotion to action and from individual to collective” [Flam and King Reference Flam, King and King2005: 4-5]. Beyond passing on a call to strike, the conversation via voice calls during the taxi strikes became a method of emotional expression, accumulation, and mobilisation through which the taxi drivers articulated their suppressed experiences and were able to empathise with each other’s suffering, which together helped form group cohesion. On top of that, through vocal conversations taxi drivers recognised that, instead of being separate individuals, they were “networked individuals” [Rainie and Wellman Reference Rainie and Wellman2012] enjoying the support of their fellows, friends, and social networks. This feeling of solidarity and empowerment pushes an increasing number of people toward mobilisation via mobile phones and makes them much more likely to engage in protests.

Affordances of Visibility and Networking in the Anti-PX Protests

Distinguished from the cases of the taxi strikes, the anti-PX protests exemplify a totally different picture of affordances. Here, most of the protesters were reportedly middle class [see Zhu Reference Zhu2007], and were clearly manoeuvring a more diversified range of functions of the mobile technologies, including mobile mass texting, photo-taking (during contention), and WeChat, etc. as part of their repertoires of contention. In other words, diversified uses of the mobile phone as a part of the protest repertoire in the anti-PX protests result from the different affordances of mobile phones, embodied in these participants’ habitus, including visibility and networking.

The affordance of visibility, or “whether a piece of information can be located, as well as the relative ease with which it can be located” [Evans et al. Reference Evans, Pearce, Vitak and Treem2017: 42], contributes to the virality and therefore visibility of both contested information about the PX project and later mobilising messages against the project. Leonardi [Reference Leonardi2014: 797] remarks that digital communication technologies increase visibility “by loosening the requirement to select a target audience through email carbon copy features or the instant messaging forward feature. Instead, the sender can create a public communication platform that can be accessed by team members.” Protesters in the anti-PX cases clearly utilise this affordance as part of their protest repertoire to either make calls for mobilisation or share stories of protest from the past. This is done with greater visibility by snowballing these politically sensitive messages via, for instance, a group messaging function, as well as sharing their discontentment toward the silence, false accusations, or censorship from official media.

The “affordance of networking” refers to the capacity of building and maintaining social networks and activating (selected) contacts from these networks. The interviewees concur that the mobile phone is a central means for relationship maintenance and help-seeking in their everyday lives. Consequently, the habituated practice of circulating messages within one’s social networks to inform each other of relevant matters and gather available network resources to help each other easily adapts itself to political mobilisation in contention.

Given the observation here regarding distinctive affordances—and subsequent protest repertoires—to different social groups in diverse contexts, it becomes clear that affordance, as we emphasise, has a decisive effect—in terms of both facilitation and constraint—on later choice of repertoire. On the one hand, taxi drivers hardly ever consider using their phones to mobilise support for protests by using the text messaging function. As voice calls occupy an inseparable place in their working life, it is not surprising that they would pick up their mobile phones and use calls for the purposes of organising and mobilisation. On the other hand, residents in a series of cities who were protesting against the PX project prioritised SMS or WeChat group messaging, as these functions allowed for a mass distribution of relevant information within their networks to quickly muster support, as was the case for these people in their daily lives.

Furthermore, it is the process of repertoire selection that constructs and consolidates the identity of a contentious population in its collective struggles against a suppressive regime. In other words, to employ text messaging or voice calls within one’s contentious repertoire goes beyond an improvised act. Rather, as Tilly [Reference Tilly1995: 30] notes, it is a clustered action that connects sets of individuals. To choose certain aspects of a protest repertoire but not others tends to convey a sense of togetherness in contention. Repertoire choice in this sense reduces heterogeneity within the protest population with respect to factors such as age, career, gender, job, etc. By the very adoption of the same repertoire, people with different backgrounds come together as a collective, consistently with certain functions of their mobile phones as part of their protest repertoire against the authorities.

To summarise, a relevant, yet less-commonly addressed issue comes to light in the discussion of the use of mobile phones as part of a contentious repertoire: the affordances of the very same technology (i.e., mobile phones) varies significantly among different social groups in different contexts, which entails the habitus of mobile phone uses that fundamentally determines (but also inhibits) repertoire choice. As we can see from the cases here, the political use of mobile phones among those with the same group label (for example, “Chinese people”) is indeed not homogeneous. Rather, it is a heterogeneous collection that embodies distinctive affordances of mobile phones among different groups. When people do not have sufficient experience or knowledge of contention, they simply “improvise” [Tilly Reference Tilly1986: 390] out of their habitus in using mobile technology. Habitus embodies specific affordances, and these affordances further facilitate and constrain repertoire choice and actual use of mobile phones. A nuanced view that integrates the consideration of affordance—and further repertoires of contention—hence avoids an oversimplified and homogenised understanding of communication technologies.

Learning through Political Contention: Modularity and Legitimation of Repertoire

If people’s routine practices with respect to to the mobile phone establish the foundation of certain mobile uses as contentious repertoire, then, learning through earlier contentious activities modularises and legitimises repertoire selection. In other words, learning from earlier experiences, especially regarding mobile phone uses as contentious repertoire, exerts a decisive influence on people’s perceptions, and thereby on uses of the mobile phone as a means of protest in later contention.

The learning process may take different forms, among which the diffusion of contention performs a crucial role in facilitating the process. Scholars in this field have delineated how diffusion of contention operates as a key mechanism in disseminating, modularising, and instituting certain contentious forms as aspects of protest repertoires in society [e.g., Wada Reference Wada2012; Traugott Reference Traugott1995b]. To be clear, learning via the diffusion process would involve different actors, via different channels. Some recognise the relevance of organisations (e.g., social movement organisations) or associational networks in the process of distributing information on contention in established networks of communication as a precondition for learning [McAdam Reference McAdam and Traugott1995: 232; also see Haluza-DeLay Reference Haluza-DeLay2008; Minkoff Reference Minkoff1997]. Others advocate the significance of mass media in the process of disseminating the news about protests beyond immediate social settings for people to learn from experiences elsewhere [Oliver and Myers Reference Oliver and Myers1999: 39; Myers Reference Myers2000]. Essentially, the diffusion of contention and learning hereafter encourage people to recognise and gain “modular repertoires” [Tarrow Reference Tarrow1993: 284] that manifest in the capacity of forms of collective action to be used in a variety of conflicts by a number of different social actors and by coalitions of people against a variety of opponents [ibid.: 299]. As such, the spread, modularity, and learning of contentious activity allow for the transferability of repertoires into different contexts [Wada Reference Wada2012]. In this process, a stock of these inherited tactics or forms of contentious actions that become habitual and that transfer across different contentious contexts consequently become “the permanent tools of a society’s repertoires of contention” [Tarrow Reference Tarrow1993: 284].

The cases we examine here epitomise the relevance of learning through information on political contention, including those involving mobile phones, which develops into “learned conventions of contention” [Tarrow Reference Tarrow2011: 29] in later struggles. In the repressive political environment in China, participants in political contention face great political risk and can encounter harsh political suppression by the authorities [e.g., O’Brien Reference O’brien2009; King, Pan and Roberts Reference King and Roberts2013]. Against this backdrop, the mere diffusion of contentious information, or the availability of the mobile phone with various affordances is not sufficient to inspire political action. Instead, protesters exploit official ideologies and tacit consent through, for instance, “[…] the innovative use of laws, policies, and other officially promoted values” [O’Brien Reference O’brien1996: 32] to legitimate their resistance and protests [see also O’Brien and Li, Reference O’brien and Li2006]. A fact that emerges and should not be ignored among the cases is that it is indeed the learning of protest information from official, mass communication that legitimises the contention, establishes mobile technologies as important parts of the contentious repertoire, and encourages the emergence of assimilation in the long run.

In his study of rural contention, O’Brien noted that increased media penetration encouraged villagers to be “more knowledgeable about resistance routines devised elsewhere” [1996: 41]. A similar situation occurred in the cases we have presented here. Apart from the knowledge of protests elsewhere, the news coverage of contentions implies that previously politically sensitive issues were no longer a political taboo. To the general public, the coverage thus denotes that these issues are all but “tolerated” [Tarrow Reference Tarrow2011: 30] by the ruling regime. In other words, the protests were recognised as “a form of officially legitimate public action” [Thireau and Linshan Reference Thireau and Linshan2003: 87] among the general public, as soon as they have been publicly covered by official media [see Oliver and Myers Reference Oliver and Myers1999: 44-45]. This is especially so when the coverage comes from a national-scale news agency (e.g., China Newsweek). Beyond the control of the local authorities but considered as “an extension of state power” [Shi and Cai Reference Shi and Cai2006: 329], it significantly persuaded locals that their protest against the local authorities had been tolerated and accepted with the collusion of the central authority, thereby establishing opportunities for later contention. In short, the interpretation of traditional media’s coverage increases the influence of contention by legitimising the protests as a kind of “partially sanctioned resistance” [O’Brien Reference O’brien1996: 33], and by consequently encouraging widespread duplication.

Reports on protests in mass communication do not merely legitimate earlier acts of contention. Rather, people read and learn details about the use of mobile technologies, among other digital communication technologies, in protests that receive news coverage. That subsequently leads to the use of mobile phones as an essential element of the contentious repertoire and further encourages imitation by late-comers.

Interviewees from several cases referred to a report they read in China Newsweek. They clearly recalled that the report, entitled “The Power of Mobile Messaging” [Xie and Zhao Reference Xie and Zhao2007], detailed how residents used mobile messaging to organise demonstrations as a unique and successful aspect of the protest [The Center for Public Opinion Monitor 2014]. In other words, the report not only describes the political influence of mobile texts; it also leaves the impression that protests and the adoption of mobile phones are bound together. People consequently treated such reports as a signal from the authorities providing tacit consent to use mobile messaging for the successful organisation of protests. This dissemination and interpretation of information generates a demonstrative effect by describing key tactics and serving as a slogan—i.e., the power of mobile messaging—to encourage people to learn and adopt their mobile media for protests. Similarly, in later coverage of the anti-PX protests, mass media reported the use of various digital media in citizens’ protest repertoires, which consequently becomes the main driving force that inspired and encouraged people to “replicate” the successful example of the past by employing their available digital media for protest.

In this way, the learning of contention plays a key role in lending impetus to the knowledge of mobile phone use as part of a repertoire of contention by establishing, modularising, and facilitating patterns of mobile-mediated contentious behaviours that “[…] can be learned, adapted, routinized, and diffused from one group, one locale, or one moment to another.” [Traugott Reference Traugott1995a: 7]. As we can see in later contentious activities undertaken elsewhere, the anti-PX protest has consequently become a typical, successful model that crystallises and acclaims mobile-mediated political activism in the process of struggling against authority and finally forcing it to change its policies. In a long-term perspective, the coverage and diffusion of contentious activities allows people to easily adopt modes of contention by learning from, and duplicating, the past, engendering “the gradual transformation of knowledge into knowing” [Le Cornu Reference Le cornu2005: 175], facilitating its transferability into other cases, and cultivating the popular perception and habitus of mobile technology, or its specific function, as a repertoire of contention in society.

To summarise, the learning of protest-related information through the diffusion of contention coincides with those sent via mobile communication during protest events. Even though the media coverage did not announce that the protests were legal, the reports were considered to be tantamount to a removal of the censorship over contested issues and as a go-ahead signal for the implementation of protest activity. Similarly, the way these reports covered the contention played a fundamental role in shaping people’s attitudes and actions. The interpretation of the coverage on the use of mobile technologies in particular encouraged people to adopting “the successful models” of the past by using their mobile devices for collective action. This consequently drove and sustained the use of mobile technology within various repertoires of contention.

Conclusion: The Social Construction of Mobile Tech as a Repertoire of Contention

This study begins by advocating the relevance of the link between affordances and the development of repertoires of contention in filling a gap in our understanding of the role of ICTs in political contention. Since the development of repertoires of contention involves specifically what people know how to do during protests [Tarrow Reference Tarrow2011: 39], a narrow focus on the use of ICTs alone limits a relational understanding of agency, technology, and context. As the cases in contemporary China illustrate, repertoire choice derives both from habitus of media use that manifests particular affordances, and from the learned experience of the contested means of the past. Variations in repertoires occur largely due to distinctive affordances. A nuanced investigation of affordance and its connection to contentious repertoires hence sheds significant light on similarities and differences regarding the perception of mobile phones as part of a contentious repertoire among different social groups in different contexts. It advances the field and calls for further consideration in terms of the following three aspects.

First, given distinct affordances, the meaning of communication technology is hardly univocal and universal, but rather varies significantly according to various agents in different contexts. As a result, instead of assuming that there is a single logic by which protesters use ICTs in movements, focusing on discrete instances of political activism and ICT use forces us to face the possibility that there may be as many different understandings of affordances as there are distinct ways of using digital communication technologies in the protest repertoires for contentious collective action. In this way, both affordance and repertoires of contention have an advantage in distinguishing fine-grained yet essential nuances in respect of their relational nature. A comparative agenda beyond the specific case of China, for instance, will further advance such understanding within different national contexts.

Second, an understanding of the development of the contentious repertoire requires an extension in order to capture, reflect, and assess the political ferment in and around the routine—or habitual––use of digital communication technologies in this study in everyday lives. Habitus, in this case, offers an analytical approach for investigating the political relevance of the mundane in structuring and underpinning specific contentious moments.

Third, an investigation of both of what people do and do not do with communication technology is of relevance in demonstrating the specific dynamics behind repertoire selection and constraint. That is to say, the reasoning behind protesters’ decisions to not take up certain activities within the protest repertoire is equally as important as their decisions regarding the adoption of specific activities.

To conclude, by explicating the link between affordance and contentious repertoire with cases from China, this study advances three propositions that contributed to a rigorous understanding of ICTs in political contention. First, the uses of ICTs in political contention are too often either taken-for-granted or presumed to be something that can be extrapolated from the functionalities of technology, despite the fact that those uses are far more contingent and deliberate in actuality. The scrutiny of ICT uses hence should not be reduced to bundles of technical properties and functionalities that are indifferent to people or contexts [e.g., Enjolras, Steen-Johnsen, and Wollebæk Reference Enjolras, Steen-Johnsen and Wollebæk2013; Christensen Reference Christensen2011; Kaun and Stiernstedt Reference Kaun and Stiernstedt2014; Ogan and Varol Reference Ogan and Varol2016; Selander and Jarvenpaa Reference Selander and Jarvenpaa2016: 333]. Second, as the use of ICTs in political activism rests on context-specific interpretive practices, the explanations of use beg the questions of affordance and repertoire of contention “for whom” and “how” in the first place. In other words, we need to ask how, and for whom, different “affordances” are transformed into a “repertoire of contention” in particular contentious settings. Third, Bourdieu’s concept of habitus reminds us of the need to contextualise the use of ICTs in political contention within the structure of everyday life, as everyday uses of ICTs establish, prefigure, and constrain the means of contention by which people engage in contentious actions. As Melucci suggests, the “phenomenology of everyday life becomes increasingly important as a research tool in connecting the macro level of collective action to the individual experience in the minute textures of day-to-day practices” [Melucci and Lyyra Reference Melucci and Lyyra1998: 221]. Exploring the use of ICTs through the prism of habitus subsequently uncovers the essence of how everyday practice underpins specific appropriation of technology in contentious moments.