Before the election of 1932 […] there was a majority in the Riksdag consisting of conservatives, liberals, and members of the farmer party, convinced that the budget should be balanced according to the traditional method and that for this reason the plans of the labor party for large public works, financed by borrowing, should be defeated. […] The labor party instead wanted an expansion of public capital investments, in the hope or expectation of creating a substitute for stagnating private enterprise.

Ernst Wigforss, Sweden’s Social Democratic Minister of Finance, 1938.

I’m convinced that we need at the national level, in many of our countries, some sort of grand coalition. I would have never been able in Italy to have a very thorough pension reform, the introduction of property taxes and the big steps against tax evasion if I didn’t have at the same time the support of the right and of the left.

Mario Monti, former Italian Prime Minister, 2013.

The dominance of budgetary austerity, the programmatic ambiguity and electoral weakness of left parties, the dubiously democratic processes by which widely unpopular reforms have been imposed, and voters’ growing attraction to extreme parties have been among the more striking features of European politics since the financial crisis of 2007-2008. In some ways, Europe’s present situation is eerily similar to the crisis years of the interwar period. With the euro now substituting for the gold standard, it would seem that Karl Polanyi’s (1944 [2001]) unstable world of the double movement, in which national politics sits uncomfortably at the crux of a deepening tension between a liberal-utopian self-regulating international market order and protection-seeking human societies, is back.

And yet, of course, the institutional landscape that inspired Polanyi’s analysis is not the same. Western Europe has recently emerged from neither a Great War nor dramatic episodes of runaway inflation; gold standard capitalism was not the deeply financialized capitalism of the present.Footnote 1 The financial architecture formed by the International Monetary Fund (imf) and other international financial institutions (ifis), among them the European Union’s (eu) main financial agencies—ecofin, the Eurogroup, and the European Central Bank (ecb)—is also distinct.Footnote 2 Meanwhile, thanks to Europe’s singularly aggressive liberalization of capital controls between the late 1980s and mid-1990s in addition to monetary union, authority over economic and financial policy-making in European countries is now much less under the purview of the nation-state (Abdelal Reference Abdelal2007). Last but not least, economics is now a uniquely influential profession on all matters economic. At once global and us-centric, the profession is essential to the arbitration and evaluation of qualified economic knowledge in a way that was unimaginable in the interwar years (Markoff and Montecinos Reference Markoff and Montecinos1993, Fourcade Reference Fourcade2006, Lebaron Reference Lebaron2006).

Less obvious, perhaps, is how this new world is shaping European politics in historically specific ways. One point of entry into this question is to look at the trajectories of bearers of political authority on questions of economic management (hereafter economic authority figures) across crisis periods. Here Mario Monti, Italy’s Prime Minister from late 2011 through 2012 (quoted above), provides an interesting case-in-point. Having followed a trajectory from academic economics, to European technocratic positions, and then into national office, Monti is one instance of a particular kind of economic authority figure, the European economist-technocrat (eet), who has been a key agent in the formulation and implementation of Europe’s crisis-time policies.

The eet is strikingly different from the economic authority figures who came to the fore during the 1930s. For instance it was Ernst Wigforss (also quoted above), an honorary Stockholm School economist and a leading member of the Swedish Social Democratic Workers’ Party (sap), who guided Sweden’s break with conservative orthodoxies in 1932 and 1933 (Henriksson 1991, Mudge forthcoming). One part economist and one part party politician, Wigforss’ hybridity was characteristic of a social type that could be found in many countries during and after the 1930s: what we might call the national party-based economist (npe). In Britain, for instance, John Maynard Keynes started to forge what we now think of as Keynesianism in the 1920s in close connection with the Liberal Party. Keynesian economic thinking would then be carried forth into Labour’s program not by Keynes, but by Labour-connected npes schooled in his thought (and sometimes by him).Footnote 3 Indeed, Wigforss’ account of the left-right distinction in 1930s Sweden is partly indicative of a moment in which npes embodied an intersection of left parties, states, and national economics professions on which a new kind of leftism, grounded in economic science, was built.

This article uses the contrast between the eet and the npe to explore how the institutional conditions of economic knowledge production in European crisis-time politics changed between the 1930s and the post-2008 crisis years. As such it is an inquiry into the institutional conditions of alternative economic thinking—that is, one manifestation of economic culture—in politics. The story of European politics today is about much more than economics of course, but to overlook the role of the economics profession in the making and unmaking of economic orthodoxies in politics would be to ignore a particularly heavyweight elephant in the room.

As is true of any profession, economists are not created equal: their orientations, theories, and projects are mediated by their professional trajectories and institutional locations (Fourcade Reference Fourcade2009; Reay Reference Reay2012). The fact that the 1930s npe was a bearer of non-austere economic truth claims, while the 21st century eet is among austerity’s staunchest defenders, prompts the question of what sort of institutional arrangements made the npe and the eet possible. In pursuit of answers, I emphasize professional economics’ relationship with both political parties and governing bureaucracies, as opposed to focusing mainly on the latter or, alternatively, treating parties as extensions of the state (e.g., Rueschemeyer and Skocpol Reference Rueschemeyer and Skocpol1996, Weir and Skocpol Reference Weir and Skocpol1985, Fourcade Reference Fourcade2009).

The article proceeds as follows. First I describe the double puzzle of European politics today in greater detail. In the second section I situate my approach, relating it to the issue’s theme of economic culture in the public sphere, locating it within a Polanyian framework that draws on insights from the moral markets literatures, and distinguishing it from perspectives that treat ideas as independent causal forces. The third section offers an analysis of the double movement in the 1930s versus the post-2008 crisis years, focusing on the npe and the eet and the conditions giving rise to them. The fourth and concluding section explores the proposition that competitors to reigning economic orthodoxies may be less likely to arise given that economic truth claims enter into politics mainly via technocratic, as opposed to democratic and partisan, institutions.

A double puzzle

Since 2008 European politics has featured a double puzzle. The first is a particularly austere response to crises of public debt (or, more accurately, the plunging of otherwise solvent countries into debt crises, with the exception of Greece). This has come in the form of coordinated efforts to inoculate European member states—especially Portugal, Ireland, Italy, Greece, and Spain, the so-called “piigs”—from the doubts of markets and creditors by committing them (and committing themselves) to severe budget-balancing reforms. In the meantime, Europe’s heads of government pursued the pan-European rule of balanced budgets via the 2012 Treaty on Stability, Coordination and Governance in the emu (the “fiscal compact”), which “requires the national budgets of participating member states to be in balance or in surplus”,Footnote 4 defined as an annual structural government deficit of no more than 0.5% of nominal gdp.Footnote 5 The treaty was ratified by 12 Eurozone members and signed in March 2012 by 25 eu countries; it entered into force on January 1, 2013.

In the meantime, news coverage has tracked civil conflict ranging from peaceful protest to small-scale warfare, even as economic surveys report unemployment rates in some countries, especially among younger demographics, that now rival or surpass Depression-era rates. Troubles notwithstanding, the eu has if anything consolidated its financial and economic powers, and Europe’s monetary integration continues its forward march.Footnote 6

Another curiosity is the programmatic ambiguity and electoral weakness of Western Europe’s parties of the mainstream left. The German Social Democratic Party (spd) offers a useful example. Despite many undecided voters days before the general election in 2013 and a “door-to-door-campaign, Obama-style”, the spd did not prevail over Angela Merkel’s Christian Democratic Union (Miebach Reference Miebach2013). Its percentage of the vote, 25.7%, was second only to its all-time low of 23% in 2009. The spd’s misfortunes are not unusual. In just over two-thirds of the 11 original members of the Eurozone, center-left parties’ share of the vote declined in elections during or just after 2008. Among non-Eurozone eu members, left parties’ electoral fortunes almost uniformly declined.Footnote 7

Europe’s leftist experts and party leaders are keenly aware that center-left parties have not been faring as well as they should be, especially in social democracy’s intellectual and political heartland (e.g, Hacker Reference Hacker2013, see also recent discussions at www.policy-network.net). Some among them point out that the weakness of center-left parties is complemented by a certain programmatic aimlessness (e.g., Hacker Reference Hacker2013). A key part of the problem, understood by both left party leadership and leftism’s many commentators, is center-left parties’ inability to think around austerity, accepting “fiscal prudence” as a moral requisite to which they are at least as committed as their counterparts on the right. The spd, for instance, ran on a series of identifiably “left” positions (a minimum wage, financial regulation, increased taxes on the wealthy, equal pay for men and women), paired with what center-left intelligentsias generally understand as a “mandatory commitment to fiscal prudence and the ‘debt brake’” (Cramme Reference Cramme2013; see also Serwotka Reference Serwotka2013).

Some are nonetheless calling for a return to Keynesianism. For example Roger Liddle, a central figure in British center-leftism since the New Labour years, argues that “the Left across Europe has so far failed to come up with a credible answer to austerity”, noting the difficulties of legitimating a “Keynesian response” in the form of “a fiscal injection of demand through extra borrowing” (Liddle Reference Liddle2013). With Keynesianism understood to mean borrowing by indebted governments in order to boost growth without raising taxes, Liddle sensibly notes the difficulties such a program raises for left parties’ self-presentation as fiscally responsible (ibid.).

And yet, while this understanding of Keynesianism is correct, it is also historically truncated. After all, in the early postwar period the term signified a whole set of assumptions, beliefs, and institutional arrangements that held out the possibility of national political discretion over the very definition of “fiscal prudence”, backed by the reigning orthodoxies and intellectual tools of professional economics. In this context the left-right axis, and leftism in particular, took on a new meaning that was interwoven with mainstream economics.

This represented a definitive shift. Before the 1930s, mainstream political parties of all stripes embraced a conservative orthodoxy that looked much like today’s “fiscal prudence”. Political elites backed this conservatism by invoking economic thought, but not necessarily living academic economists—hence Keynes’ complaint that laissez-faire was a doctrine of “popularizers” and vulgarizers” [Keynes Reference Keynes1926]. But between the 1930s and the 1960s a particular economic authority figure, who had one foot in center-left parties and the other in professional economics, mobilized Keynesianism (or something like it) to legitimate a specifically leftist economic program. A hallmark was the re-figuring of deficit spending as economically beneficial investment rather than fiscal irresponsibility. This helped to untie the hands of left parties to develop proactive policies while still making strong claims to scientifically-grounded economic management. By clearing the way for employment to become a central goal of government policy, it also facilitated left parties’ historical alliances with organized labor (Mudge forthcoming).

Seen in this way, the present moment starts to look distinctive partly because Keynesianism is now a mere policy option that even those on the left are reluctant to advocate. Unraveling the twin puzzle of institutionalized austerity and the missing left requires an understanding of how this came to pass.

From ideas to the making of economic authority figures

In order to understand Europe’s double puzzle one might naturally consider the “power of economic ideas” (Hall Reference Hall1989), noting in particular the neoliberal project and the legitimation of its logic and policies from the 1970s forward (Mudge Reference Mudge2008, Mirowski and Plehwe Reference Mirowski and Plehwe2009, Peck Reference Peck2010). And yet, while there can be no doubt that neoliberal ways of thinking took hold across the political spectrum during this time, taking neoliberal ideas as a fundamental cause raises a series of thorny epistemological and analytical problems. Not least among them is the question of whether neoliberal ideas can really be understood as a thing in mechanistically causal terms. The difficulty is particularly pronounced when dealing with actors on Europe’s political left, who lack ties with neoliberal economists and free market think tanks, directly reject neoliberalism as a discredited project of the right, and have never been mere receptors of social scientific thought (Mudge forthcoming).

For students of classical social theory the vision of a world driven by ideas might call to mind Karl Marx’s famous critique of this kind of thinking. Marx argued that ideational accounts of history inevitably expressed the particular worldview of their socially situated progenitors. If such accounts are widely accepted, Marx argued, it is only because those who advance them “regulate the production and distribution of the ideas of their age” (Marx Reference Marx and Tucker1846 [1978]: 172-173). Pierre Bourdieu (1997 [2000]) made a very similar argument, warning social scientists against mistaking their perspective from the ivory tower—a world in which ideas matter a great deal, as a matter of professional necessity—for general truth (see also Wacquant Reference Wacquant2006).

Taking these warnings seriously, the present analysis backs off from mechanistic ideational explanation in favor of treating economic knowledge production as a grounded social activity that intersects with politics via various institutional channels. Both economic knowledge production and its intersection with politics are integral to moral struggles over markets and market-making, which intensify in crisis periods (Fourcade and Healy Reference Fourcade and Healy2007, Fourcade et al. Reference Fourcade, Steiner, Streeck and Woll2013). At such times the institutional situation of economic authority figures becomes especially central to the “production and distribution of the ideas of the age” (to borrow Marx’s phrasing). Accordingly, and in a way that aims to complement literatures in economic sociology that incorporate a sociology of the economics profession into the study of markets, states, and politics (Lebaron Reference Lebaron2001, Fourcade Reference Fourcade2009, Reay Reference Reay2012), I focus on the making of economic authority figures, as opposed to the ideas they articulate, in order to understand the unfolding of recent crisis-time politics.

Polanyi’s famous analysis of the double movement in the early 20th century offers a useful point of entry into these issues partly because it can be mined for purposes of historical comparison, and partly because he is vague on the significance of the kinds of institutional arenas—representative, technocratic, cultural, marketized—in which his “double movement” plays out. In order to better specify these arenas across historical periods, I start not with institutions but with the professional cross-locations of economic authority figures. Because those cross-locations demand it, I place particular emphasis on the relationship between professional economics and political parties.Footnote 8

Why focus on economists, when economic authority figures have borne a variety of credentials and expert claims in the history of Western policy struggles? By many reports, economists emerged among the victorious by the late 20th century. Their victory was partly due to the postwar reconstruction of states as “economies”, marked by the birth of national accounts and the development of econometrics during the decline of the age of empire; it was also due to the development of economics into a global profession (Callon Reference Callon1998, Mitchell Reference Mitchell1998, Fourcade Reference Fourcade2006). In the process the double movement was technified and internationalized: tensions between market expansion and societal protection came to be channeled through the language, practices, and analytical techniques of consecrated (that is, credentialed) international bearers of professional economic knowledge (Fourcade and Healy Reference Fourcade and Healy2007, Dezalay and Garth Reference Dezalay and Garth2002). Stated in the terms of the present issue, professional economists became privileged bearers of economic culture in the public sphere.

Importantly, professional economists struggled to play this privileged role in the 1930s. Where they did, they stood out both for their non-orthodox truth claims and their close ties to partisan institutions. I turn to this and other important institutional differences between the 1930s and the post-2008 years, focusing on the existential conditions of the npe and the eet, in the following section.

Déjà vu?

Crisis-time politics, then and now

A Polanyian view of present-day European crisis politics is difficult to resist (e.g., Blyth Reference Blyth2013). Europe’s post-crisis efforts to secure the financial stability of the Eurozone amid waves of protest easily call to mind Polanyi’s description of the “self-adjusting market” as a “stark utopia” that would attract political resistance, and ultimately give way (Polanyi Reference Polanyi1944 [2001]: 3-4).

One of the many Polanyian similarities between crisis times then and now is the apparent irreconcilability of democratic pressures with “disembedded” market institutions. For Polanyi the fundamental cause of Europe’s near-civilizational collapse in the first decades of the 20th century was the construction of a crisis-ridden economic order built on English liberal thinkers’ unwavering beliefs in self-adjusting markets. These beliefs, sown into everyday experience via the classical gold standard, helped to build an age of global capitalism between about 1880 and 1913 that has not yet been surpassed (Quinn Reference Quinn2003: 191; see also Hawtrey Reference Hawtrey1947, Eichengreen Reference Eichengreen1998, Cohen Reference Cohen1998, Frieden Reference Frieden2006).Footnote 9

The problem, Polanyi argued, was that this world generated disruptions and instabilities that frayed the fabric of human communities. Since currency equilibration worked through the free movement of gold in and out of countries, the burden of price adjustment fell especially on vulnerable groups: farmers, laborers, and small businesses (that is, most of the population) (Quinn Reference Quinn2003). Absent government efforts to cushion these effects, shocks, and depressions tended to produce a counter-reaction. Thus was born the “double movement”: against the forces of “boundless and unregulated change,” a series of “protective counter-moves” that blunted market forces (Polanyi Reference Polanyi1944 [2001]: 79). The further commodification went, Polanyi argued, the more profound the double movement, and the more precarious the international order, became. In short, Polanyi understood that “you cannot run a gold standard […] in a democracy” (Blyth Reference Blyth2013: 77).

Clearly there are parallels to the present. The financial crisis intensified political instabilities already on display in Western Europe and elsewhere during the market-expanding decades leading up to 2008; the rise of radical right-wing parties and “illiberal politics”, viewed by some as a direct effect of both European integration and economic globalization, was duly noted well before the crisis (Holmes Reference Holmes2000, Swank and Betz Reference Swank and Betz2003, Rydgren Reference Rydgren2007, Berezin Reference Berezin2009). Although today’s right wing parties are not the same as fascist groups of Europe’s past, their emergence and growing strength since the 1980s is entirely consonant with Polanyi’s notion of the double movement as a set of irreconcilable tensions between competing social forces that builds over time.

Both the inflexibility of the gold standard mechanism and its intellectual roots also bear clear parallels to the present. The euro’s imposition on vastly different national economies, eliminating the option of devaluation and tying national monetary fates to each other, all backed by a central bank charged, above all, with controlling the rate of inflation, is not the same thing as the gold standard. However, by constructing a single market more or less by fiat, limiting the ability of national politicians to cushion the effects of market forces, and divorcing monetary policy from non-monetary economic and political concerns, it may be having basically the same consequences. And, like the Ricardian basis of the gold standard, the euro was also grounded in intellectual constructions (or, more accurately, debates over and reactions against them)—including Robert Mundell’s concept of an Optimal Currency Area, or oca (Mudge and Vauchez Reference Mudge and Vauchez2012).

Finally, until the 1930s, budgetary conservatism was, as now, the reigning political common sense. It was for this reason that—unlike in the most recent crisis period—the fact that the electoral fortunes of the left parties were then strong and improving did not mean that they would embrace deficit spending once in government. As unemployment reached new highs and organized labor strengthened, left parties received up to one-third of the vote in some countries, becoming parties of government for the first time during the 1920s (for instance) in Sweden, Great Britain, Germany, and Spain (Sassoon Reference Sassoon1996: 42). Elected on promises of protection and the “socialization” of the economy, their commitments proved hard to keep; soaring unemployment rates threatened the solvency of contribution-dependent unemployment insurance schemes, many of which were introduced between 1907 and 1929. Marxist or not, young left parties-in-government tied their own hands by rejecting the notion that deficit spending could be anything other than a risky stop-gap measure. Polanyi himself noted this curiosity of the interwar years, attributing it to a cross-party, nearly religious faith in the economic orthodoxies that backed the gold standard order.

Bucking the trend in interwar Sweden: the rise of the npeFootnote 10

A duly noted exception, however, was the Swedish sap’s crisis program of 1933, which favored loan-financed, large-scale public works (among other things). This program has been explained as a party-level ideational effect, expressing the adaptive revisionist thinking of the sap, as opposed to the rigid Marxist orthodoxy of the German spd (e.g., Berman Reference Berman1990, Reference Berman1998). Yet this explanation becomes difficult to accept if we consider that the British Labour governments of 1924 and 1929-1931, dominated intellectually by revisionist, non-Marxist Fabian socialists, also embraced conservative budgetary orthodoxies. Another difficulty is that, as late as 1925, sap leadership was conservative on questions of economic policy. Tingsten (1941 [1973]) thus notes that the sap’s 1920s crisis policy was largely “negative”—that is, it relied on austerity, not stimulus.

An account that starts not with ideas, but with (1) the relationships between left party leadership and national economics professions, and (2) how those relationships facilitated or pre-empted the efforts of economists bearing non-orthodox prescriptions, offers a way of coping with these difficulties. In the Swedish case, the sap’s decisive turn away from orthodox thinking was closely associated with the coincidence of Ernst Wigforss’ ascendance to the SAP’s leading ranks and his effective membership in what would later be dubbed the “Stockholm School” of Swedish economics (Ohlin Reference Ohlin1937, Jonung Reference Jonung1991). The only non-academic with honorary membership in the Stockholm-based Political Economy Club at the time, Wigforss was also a younger generation sap party member. He may well have been excluded from the party’s senior ranks but, by happenstance, he replaced his economically orthodox predecessor (Fredrik Thorsson) as the sap’s main economic expert in 1925.Footnote 11

From his new position Wigforss set about incorporating Stockholm School economics into the sap’s program-building procedures. Central to his efforts were arguments that the way to deal with the problem of unemployment was by thinking differently about the uses and effects of government spending—a proposition made more palatable by the breakdown of gold in 1931 (Wigforss Reference Wigforss1938, Jonung Reference Jonung1991). Ties between the sap and Swedish economics that Wigforss both helped to forge and himself embodied resulted in the party’s 1933 crisis program, which married Stockholm School theories to social democratic politics. (Notably, the program’s theoretical appendix was written by the Stockholm economist Gunnar Myrdal) (Tingsten Reference Tingsten1941 [1973]).

In Germany and Britain, meanwhile, the left parties’ non-academic intellectuals blocked economists bearing non-orthodox prescriptions. In Britain Philip Snowden, Labour’s interwar Chancellor of the Exchequer, famously insisted on fiscal conservatism as the best general principle. Snowden rejected (or, perhaps more accurately, ignored) the recommendations of professional economists from both within the party and without—including Keynes (who in any case was closely linked with the Liberals), Hugh Dalton (a Fabian, party member, and Keynesian economist), and others; he likewise dismissed non-economists like Oswald Mosley and trade union leaders who supported Dalton. Snowden, an autodidact who was more partial to hard numbers-based budgetary accounting than the abstract theories of young academic economists, held fast to conservative orthodoxy despite the government’s growing unemployment benefit liabilities (Cross Reference Cross1966, Tanner Reference Tanner2004, Mudge forthcoming). The ensuing impasse would split the party and bring the Labour government to an end.

In Germany, Rudolf Hilferding (the spd’s minister of finance) reacted very much like Snowden to professional economists’ non-orthodox prescriptions. As the spd’s premier in-house Marxist theorist in what was then most influential socialist party in Europe, Hilferding committed the spd to a surprisingly laissez-faire course of action that did little to address unemployment and political unrest (Berman Reference Berman1998, James Reference James1981, Smaldone Reference Smaldone1998). Like Snowden, Hilferding headed off economists bearing non-orthodox prescriptions (most notably Wladimir Woytinsky, then working with the German trade unions) by framing their arguments as contra Marxism and thus unacceptable for a party that was its internationally recognized bearer. This was less a “battle of ideas” and more a battle pre-empted: Hilferding set up Woytinsky’s arguments for dismissal, even as Woytinsky protested that his recommendations had no bearing whatsoever on Marxist theory (Woytinsky Reference Woytinsky1961, Mudge forthcoming). In one of the most scrutinized political events in Western history, the spd-dominated government would soon give way to Hitler’s National Socialists.

Our understanding of interwar crisis politics is thus usefully amended by considering the relationship between party leadership and professional economists—who were, at the time, among the most vocal bearers of non-orthodox prescriptions, but were not the dominant intellectuals of left parties. Neither Snowden nor Hilferding were academic economists; in both countries, the academy had a history of hostility to socialism and Marxism. Partly by necessity, then, Snowden and Hilferding became economic authority figures by virtue of opportunities made available via party organizations, especially the publishing houses, newspapers, and weeklies that were then an essential feature of organized political leftism at that time. They were, in short, party theoreticians, embodying an age in which states and parties drove the definition of legitimate economic knowledge. In this world the npe was an interloper whose advice was easily ruled out-of-bounds (Mudge forthcoming).

In the late 1920s and early 1930s even John Maynard Keynes navigated a primarily domestic political arena in which a professional economist’s opinion on, say, a budgetary question was no more authoritative than that of a politician or technocrat. Keynes had to negotiate his way to authority, partly by working through political parties. In the process Keynes’ fate was hitched to the Liberal party; thus invested in a party that would be defunct by the 1930s, he never did manage to influence Labour leadership directly. Within state administrations, on the other hand, national economists ran up against the authority of civil servants (again, Keynes’ conflicts with the Treasury offer a case-in-point here) (Howson and Winch Reference Howson and Winch1977).

As time progressed, however, mainstream Western parties—especially on the left—became more interdependent with “Keynesian” economics. In the process the npe became a recognizable authority figure in politics, characterized by his hybrid position as both a professional economist and a loyal partisan. Examples abound, from Gösta Rehn in Sweden, to the “Gaitskellites” in the uk, to Walter Heller and James Tobin in the us, to Karl Schiller in Germany (Haseler Reference Haseler1969, Foucault Reference Foucault1979 [2010], Erixon and Wadensjo Reference Erixon and Wadensjö2012, Mudge forthcoming). In Europe especially, this was driven by credentialed economists’ graduation into political parties’ leading ranks and their growing presence in trade union research departments and wartime states, building a multi-faceted bridge between the burgeoning economics profession and national political orders (Mudge forthcoming).

In short, it was not just the generalized force of ideas but a very real interdependence between professional economists and party organizations, embodied by the figure of the npe, that helped to remake mainstream leftism and Western politics between the 1930s and the 1960s.

Europe’s new institutional landscape

In the turbulent years from the late 1960s onwards, the decline of Keynesianism and the “Americanization” of European economics corresponded with a breakdown in the profession’s relationships with national politics and policy debates (Sandelin Reference Sandelin and Coats2000, Frey et al. Reference Frey, Humbert and Schneider2007, Colander Reference Colander2008, Stern Reference Stern2009, Mudge forthcoming). On the other hand, as the profession became more internationalized and developed deeper ties with central banking and finance, its relationship to the main institutions of Europe’s financial architecture strengthened. This world gave rise to a new economic authority figure in European politics: the eet.

Central banks and professional economics

The establishment of central banks began in Europe between the 17th and 19th centuries, but the striking authority and “scientization” of today’s central banks is a relatively recent development (Eichengreen Reference Eichengreen1998, Fourcade Reference Fourcade2006, Marcussen Reference Marcussen2009). Between the crises of the 1930s and the early 1970s ministers of finance were more powerful decision-makers on financial questions than central bankers, whose “presidents or governors played a relatively limited and quiet role in economic and financial policy making” (Pollilo and Guillén 2005, p. 1767). This changed, however, in the 1970s. The collapse of the exchange-rate system in 1973 resulted in the propulsion of central bankers to new positions of power and authority, a joint effect of their prominent role in efforts at international financial and economic cooperation in the 1980s and a growing political acceptance that one of the best ways to control inflation (due to expansionary policies like tax cuts and government spending) was to grant central banks more political autonomy (Pollilo and Guillén 2005: 1767-1768).

During the 1990s no fewer than 54 countries in Eastern and Central Europe, Western Europe, Latin America, Africa and Asia made statutory changes to autonomize central banks. Many that did not make statutory changes, like the United States, granted them greater autonomy by other means (Pollilo and Guillén 2005: 1771-1772). Partly due to the power and influence of the German Bundesbank in the process of building the Eurozone, the ecb stood out among its peers for its particularly high degree of independence when it was established in 1999 (de Haan and Eijffinger Reference De Haan and Eijffinger2000: 396).

With the rise of independent central banks came that of the bankers who managed them. Central bankers became relatively more powerful vis-à-vis finance ministries, treasuries, and the legislative branch. Central bank independence also augmented the power of economists, partly because it had become increasingly common that central bankers were also professionally-trained economists. This period was also marked by central banks’ scientization: the birth of cross-bank networks of credentialed economists built on “epistemic clan structures”, sizable bank-based research departments, in-house academic journals, and other markers of a whole new bank-centered apparatus for the production of economic knowledge (Marcussen Reference Marcussen2009: 375-379).

Complementary to this was the intensification of network ties across ministries of finance, central bank governors, European Commission economic directorates, and ifis from the 1970s forward—a process traceable to the 1950s, linked to expanding international capital flows, monetary instability, and European integration (Mudge and Vauchez Reference Mudge and Vauchez2012, Major Reference Major2014). An effect was the construction of a whole new professional ecosystem—what I have elsewhere termed a “weak field of European economics”—complete with its own elite professional trajectories, internal cultures, and organizational bases of knowledge production and dissemination (Mudge and Vauchez Reference Mudge and Vauchez2012).

A look at some comparative trajectories of central bank governors in the 1930s and in 2008 provides some impression of the change.

Of central bank governors in the us, the uk, and Germany in the 1920s and 1930s, only the German governor had specific training in economics (see Table 1); none were academics. This reflects, in part, the fact that economics in Western Europe was variably institutionalized by the 1920s (Fourcade Reference Fourcade2006: 161; Fourcade Reference Fourcade2009; Jonung Reference Jonung1991). Between 1945 and the early 1970s, however, faculties of economics both proliferated and autonomized from the other social sciences (Fourcade Reference Fourcade2006). Meanwhile credentialing and professional recognition as an economist became more central to the leadership and staffing of central banks. Eisenhower’s appointment of Arthur F. Burns, a professor of economics at Rutgers and Columbia Universities, as Chairman of the Federal Reserve was one marker of the arrival of economics as a core credential in American central banking. By the time of the 2007-2008 financial crisis, a leading central banker with advanced economics training, or actual or de facto membership in the economics profession, flanked by a substantial staff of professional economists, had become commonplace in Western Europe and the United States (Marcussen Reference Marcussen2009).

Table 1 Head central bankers’ credentials in Germany, the UK and the US, 1920s-1930s versus the present1

1 Sources: www.bundesbank.de, www.bankofengland.co.uk, web.worldbank.org, www.federalreserve.gov, all accessed 17 and 22 September 2010.

Ecofin, the Eurogroup, the ecb, and the imf

Central to decision-making during the Eurozone crisis have been the decisions of European finance ministers (ecofin), the European Commission (ec), the Eurogroup (finance ministers of Eurozone countries, the Commission’s Director-General for Economic and Financial Affairs, and representatives of the ecb), the ecb, and the imf. To the outside observer, each appears as a distinctive entity, masking what is in fact a complex infrastructure of European financial and economic governance made up of transversal and overlapping professional networks, inclusive of the world described in the previous section.

The Eurogroup is an informal (that is, not based on an eu Treaty) body made up of the finance ministers of the Eurozone countries, the eu’s Vice-President for Economic and Monetary Affairs and (usually) the President of the ecb (Scheller Reference Scheller2006: 135). It is one facet of a professional ecology with origins that date, at least, to the early 1960s, but that became increasingly elaborate in the wake of the Maastricht Treaty.

Recognized as an informal grouping in the Lisbon Treaty (which came into effect in December 2009), the Eurogroup generally meets once a month, just prior to the meeting of the Council grouping on Economic and Financial Affairs (ecofin) (eu 2014a). ecofin includes many of the same people, as it is composed of the eu member states’ ministers of economic and financial affairs, as well as budget ministers (ecofin 2014).Footnote 12 The Eurogroup’s supporting committee, the Euro Working Group, bridges the Eurogroup and the Economic and Financial Committee (efc); the efc, in turn, links ecofin, the ecb, the Commission and the national central banks to each other (eu 2014b).Footnote 13 Since the financial crisis the expansion and formalization of this world has, if anything, accelerated, with Brussels at its center (eu 2014c).

As is the case for national central banks, the prominence of economics in this world is striking. This has been true, at least, from the beginnings of Europe’s market-making initiatives in the 1980s (Mudge and Vauchez Reference Mudge and Vauchez2012). The European Commission, which had two economist-dominated directorates at its beginnings (competition and economic and financial affairs), was increasingly populated by economists under the presidency of Jacques Delors (Georgakakis and de Lassale Reference Georgakakis and Lassale2008). Last but not least, the establishment of the ecb in 1999—featuring a research directorate with more full-time researchers than the London School of Economics (lse)—is another organizational hub joining European-level bureaucracies and the economics profession (Marcussen Reference Marcussen2009: 377).

These processes went hand-in-hand with the construction of what is now a self-consciously European economics—the existence of which, as recently as the 1990s, some economists found debatable (e.g., Forte Reference Forte1995, Rothschild Reference Rothschild1995). Early glimmers of the crystallization of European economics started to appear in the 1970s, marked by a steep increase in Europe-based centers of economic research.Footnote 14 Two anchor-points, established in the mid-1980s, were explicitly intended as counterparts to the us National Bureau of Economic Research and the American Economics Association: the Centre for Economic Policy Research (cepr), established in London in 1983, and the European Economics Association (eea), established in 1984 in Brussels but now in Milan—in close proximity to Bocconi, an important center of Italian economics from which Mario Monti, among others, hails.

This relatively young ecosystem of European economics intersects with European institutions through the various offices, agencies, and committees that deal with economic, monetary, and financial issues. The presence of professional economists on ecofin and the Eurogroup, in particular, has to do partly with the rise of economists among ministers of finance. At the time of the crisis more than half of Europe’s finance ministers had degrees in economics (at least 53%).Footnote 15

Notably, the cepr is closely connected to academic economics departments cross-nationally, central banks, and European institutions, but keeps a formal distance from partisan ties. Now featuring a network of fellows and affiliates consisting of more than 800 economists working on “the European economy”, the cepr’s anti-partisan structure is clear in its self-description:

cepr is […] a distributed network of economists […] who collaborate through the Centre on a wide range of policy-related research projects and dissemination activities. […] One of cepr’s main achievements has been to create a virtual “centre of excellence” for European economics through an active community of dispersed individual researchers…. cepr’s “thinknet” structure also supports the Centre’s pluralist and non-partisan stance (cepr 2013a).

The cepr’s funding base is spread across private, public, and non-profit organizations, but its corporate members “provide core income” (cepr 2013a). These members include no less than 31 central banks plus the Bank for International Settlements, as well as more than a dozen corporate banks (including Citigroup, Credit Suisse, JP Morgan, and Lloyds) and two finance ministries (the Cypriot Ministry of Finance and the British Treasury) (cepr 2013b).

Europe’s oft-noted dual structure—with market-making centered on the European level, and politics centered on the national level—is thus bisected by a globalized academic profession that has developed, in tandem with the Eurozone, a self-identified European arm. This was an important social basis on which the euro was constructed in the absence of political unification, and set the stage on which post-2008 crisis politics is playing out still.

The rise of the eet

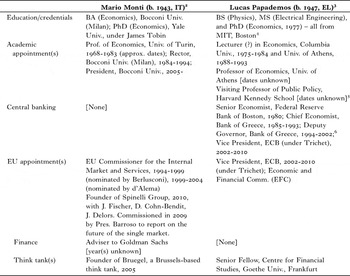

The figure of the eet has played an unmistakably central role in Europe’s recent crisis politics. Strikingly, when it appeared that domestic politics might become an insurmountable obstacle to the imposition of austerity reforms in Italy and Greece, two figures with near-identical professional trajectories entered, unelected, into national office in the year 2011: men born in the 1940s, recognized primarily as professional economists, trained in whole or in part in the United States, with professional trajectories that tracked from the academy, into central banks or eu institutions or both, and then into the prime ministerial offices of their respective countries (see Table 2).

Table 2 Professional trajectories of two EETs (in roughly chronological order, from top to bottom)

2 Sources: MontiReference Monti2010, DonadioReference Donadio2012, BBC 2013, Flores et al. 2013.

3 Sources: http://www.voxeu.org/person/lucas-papademos, BBC 2011, DaleyReference Daley2011.

4 At MIT Papademos was a classmate of Mario Draghi (DaleyReference Daley2011).

6 While at the Bank of Greece, Papademos “worked to stabilise the Greek economy so that it could join the Eurozone” (BBC 2011).

To some extent Monti’s and Papademos’ trajectories are special: most eets do not become prime ministers. And yet their similarity is not coincidental. Monti and Papademos are products of a particular cohort of Europe-based, us-connected economists who came of age alongside (and to some extent within) the making of Europe as it now stands.

Central to this cohort was the partly us-trained Italian economist Tommaso Padoa-Schioppa (1940-2010), widely credited as a “father of the euro” (Sylvers Reference Sylvers2010, Treanor Reference Treanor2010). Signaling the specificity of European professional economics’ new ecosystem, Padoa-Schioppa was a Bocconi classmate of Monti in the 1960s, and worked with him in various capacities until Padoa-Schioppa’s untimely death in 2010 (Monti Reference Monti2011). Padoa-Schioppa was also an acquaintance of Papedemos since (at least) the late 1980s, when Padoa-Schioppa chaired a working group, assembled by eu President Jacques Delors, that was central to the process of building support among central bankers for European monetary union (Monti Reference Monti2011, Thygesen Reference Thygesen2011). What is striking here is not only the biographical interconnections of these emergent economic authority figures, but also their centrality to the construction of the very world that makes the eet possible.

In this world it is now also possible, and perhaps very likely, that one’s professional life depends very little (if at all) on the successful formulation of economic programs that coincide with the interests and goals of partisan institutions, on either side of the political spectrum. It is, in other words, a professional world that intersects with, but does not depend on, the institutions of national democratic politics. This does not mean that political preferences are not at work for the eet, but it casts doubt on the possibility that present-day crises will allow for the carving out of alternative paths, much less a revolution in economic orthodoxy, that is at all comparable to that fostered by figures like Wigforss and Keynes.

Theorizing the probability of alternative thinking

The relationship between the eet, the eet’s professional world, and austerity in Europe is not mechanistic or unidirectional. More importantly perhaps, my aim here is not to point fingers at economists as behind-the-scenes philosopher kings imposing austerity at all costs. Nor is the story one of permanent conservatism in European economics, the profession more generally, or center-left politics: organizations like Vox.eu and the Institute for Economic Thinking (inet), not to mention the striking response to Thomas Piketty’s Capital in the 21 stCentury, suggest that new economic authority figures are surely in the making.Footnote 16 Rather, the basic point is that, regardless of the political leanings or intentions of any particular economist, economics is a profession with variable linkages to political and technocratic institutions. Those institutions shape both professional opportunities and the doxic limitations of struggles over policy-making.

The channeling of professional knowledge claims through partisan, as opposed to technocratic, institutions is of course no guarantee of a doxic break—but, given that the articulation of alternative worldviews is intrinsic to partisan struggles, it is likely an important precondition. The rise of new economic authority figures who are both predisposed toward and capable of injecting non-orthodox prescriptions into mainstream politics—as Keynes and other young economists were—may thus be decidedly less probable in today’s Europe. Whereas economists in the 1930s, to the extent that they did shape politics, mainly did so via political parties and national governments, today’s eet is neither a primarily national animal nor beholden to partisan ties for his or her professional opportunities. Instead, the eet moves in circles marked by deep professional investments in the legitimacy and orthodoxies of the Eurozone.

In short: it stands to reason that an economics that works through inherently oppositional national-level partisan institutions might provide fertile terrain for the articulation of alternatives; an economics that keeps its distance from partisan institutions and is removed from national politics, but is closely tied to increasingly powerful central banks and financial technocracies, probably is not.

Evaluation of this proposition, however, will depend on whether ongoing efforts to reinvigorate the study of political parties (see, e.g., De Leon Reference De Leon2014; Mudge and Chen Reference Mudge and Chen2014) take account of their historical roles as bearers of economic culture in the public sphere.

Acknowledgments

This article draws from a book manuscript currently titled Neoliberal Politics, and from research supported by the Sheffield Political Economy Research Institute (speri). I would like to thank Nina Bandelj, Fred Block, David McCourt, Anthony Payne, and two anonymous reviewers for helpful comments.