Introduction

In 1960, the United Nations General Assembly (UNGA) adopted Resolution 1514 titled Declaration on the Granting of Independence to Colonial Countries and Peoples. The right to national self-determination upheld in the resolution was certainly not novel in international politics. Given immense authority by both the Russian revolutionary Vladimir Ilyich Lenin and US President Woodrow Wilson, it formed the basis for the emergence of new states in Central and Eastern Europe and the Balkans after the end of WWI. It was later included in the very first article of the UN Charter adopted in 1945, thus becoming an international political and legal right of all peoples and nations.Footnote 1 The UNGA subsequently affirmed this right in a number of resolutions in the 1950s.Footnote 2 Resolution 1514 thus sought to reaffirm the principle of national self-determination as an unqualified right of all peoples – a principle in need of immediate implementation due to the continuation of European colonial rule in many parts of the world.Footnote 3

However, although national self-determination emerged as a fully recognized norm in the post-war era, its practical implementation through decolonization was resisted by European colonial powers well into the post-war period, both before and after the adoption of Resolution 1514. This raises the following questions. How did European colonial powers justify ongoing European rule in international forums? And how were their ideas, narratives and justifications contested by newly decolonized countries? More broadly, how was the struggle for decolonization carried out at the UN?

Existing historical sociological scholarship on decolonization has recognized the role of international forums, particularly the UNGA, in decolonization struggles led by newly decolonized Third World countries [e.g. Bull and Watson Reference Hedley and Watson1984; Crawford Reference Crawford Neta2002; Go Reference Go2008; Go and Watson Reference Go and Watson2019; Meyer et al. Reference Meyer John, Boli, Thomas and Ramirez1997; Reus-Smit 2013; Strang Reference Strang1990]. However, there has not been adequate theorization of how anticolonial demands took shape therein and how these were contested, and ongoing rule justified, by European colonial powers. The aim of this article is to illuminate the dynamic, interactive and contentious processes through which anticolonial political discourses were produced and rendered authoritative at the UN. The analysis proceeds through the case of Algeria’s decolonization from French colonial rule that was debated between 1955 and 1961 at the UNGA.

This article builds on insights from historical sociology and constructivist international relations that emphasize the critical role of rhetorical and discursive struggles, narrativization and argumentation in constituting political outcomes [e.g. Bourdieu Reference Bourdieu1991; Epstein Reference Epstein2008; Krebs and Jackson Reference Krebs Ronald and Jackson2007; Somers Reference Somers Margaret1994; Spillman Reference Spillman1995; Steinberg Reference Steinberg Marc1999]. It advances a relational and dialogical approach by situating UNGA as an agonistic social space characterized by contentious debates and discursive struggles aimed at meaning-making. The UNGA, I argue, is a social site constituted by the relational emergence of competing discourses, couched in distinct historical narratives organized around international legal norms, from which all states choose in the course of voting for proposed draft resolutions.

The Algerian question in particular yielded two distinct discourses with respect to decolonization. The first was an anticolonial internationalist discourse premised on a critique of French imperialism, an affirmation of the embodied experiences and consciousness of Algerians, and the necessity of internationalizing anticolonial struggles. The second was a metrocentric civilizational discourse aimed at redeeming the European colonial project by proclaiming the benefits of the French presence in Algeria, opposing Algeria’s anticolonial struggle, and resisting international involvement in “French Algeria”. Strikingly, both narratives drew on distinct ideas about human rights and development, and both entailed different visions of the functions of the sovereign state and international society. The article’s relational and processual approach also highlights the emergence of distinct camps of states around the two narratives. However, contrary to mainstream understandings, these camps did not fully align with the Third World/West divide. The analysis thus cautions against the widespread tendency to posit a priori distinctions between an anticolonial Third World and an imperialist West.

Decolonization and International Society: Existing Approaches

While empires have risen and fallen across history—and may continue to do so in the future—international society has never been as unanimous as it is today in delegitimizing the forcible long-term occupation of territories. The question thus arises: how did ideas and norms delegitimizing colonialism “stick” in the reconstituted post-war international society? Scholars of decolonization have offered three main perspectives to account for the end of colonial empires in the post-war period: imperial/metropolitan, local/peripheral and international [Darwin Reference Darwin1991: 5-7; Jansen and Osterhammel Reference Jansen Jan and Osterhammel2017: 22-25; Rothermund Reference Rothermund2006: 41-48]. The first emphasizes factors and processes specific to political developments in the colonizing metropole such as, for example, shifting norms within European metropoles [Crawford Reference Crawford Neta2002; Jackson Reference Jackson Robert, Goldstein and Keohane1993]. The second takes anticolonial movements and intellectuals as its point of departure [e.g. Chatterjee Reference Chatterjee1993; Fanon Reference Fanon1965; Mishra Reference Mishra2012; Spruyt Reference Spruyt2000]. The third, which takes an international approach, emphasizes the role of world opinion, international legal regimes, and great/superpower orientations to account for decolonization. This article engages with international approaches with a specific focus on those centered on the UN. None of these, I argue below, have fully delved into the contentious discursive processes through which European colonial rule was delegitimized at the UN.

Within sociology, an influential perspective has been advanced by World Polity/Society Theory (WPT). This approach is primarily concerned with explaining organizational homogeneity among modern states by identifying socialization processes [DiMaggio and Powell Reference DiMaggio Paul and Powell1983; Schofer et al.: Reference Schofer, Hironaka, Frank, Longhofer, Amenta, Nash and Scott2012; Thomas Reference Thomas George2009]. WPT does not take the presence of an international system monopolized by sovereign nation-states as a given. It maintains that this system was produced through the global diffusion of the norm of self-determination by anticolonial movements that was subsequently reaffirmed by the UN in Resolution 1514 [Meyer et al. Reference Meyer John, Boli, Thomas and Ramirez1997; Strang Reference Strang1990].

WPT is certainly on point in noting the import of the norm of national self-determination in the post-war era. However, while WPT recognizes its salience, it does not theorize how this norm was contested, resisted, and eventually consolidated in international society. As a number of scholars have pointed out, this occlusion of conflict is endemic to WPT [e.g. Finnemore Reference Finnemore1996; Koenig and Dierkes Reference Koenig and Dierkes2011]. The primary mechanism that WPT identifies ––diffusion––is “silent on the institutional structures and practices of international society itself,” thereby occluding the complex international politics of decolonization [Reus-Smit and Dunne 2017: 24]. Due to WPT’s tendency to underplay conflictual aspects of international politics, decolonization appears as an uncontested phenomenon at the UN.

The English School of International Relations (ESIR) explains the formation of the post-war international society through the metaphor of expansion. In their seminal volume, The Expansion of International Society, Hedley Bull and Adam Watson define international society as “a group of states … which not merely form a system, in the sense that the behavior of each is a necessary factor in the calculations of the others, but also have established by dialogue and consent common rules and institutions for the conduct of their relations” [Bull and Watson Reference Hedley and Watson1984: 1]. They argue that the post-war international society emerged from the European international society, subsequently permitting entry to a number of non-European states that clamored for international recognition and met the “rigorous qualifications for membership drawn up by the original or founding members” under the rubric of “standard of civilization” [Bull and Watson Reference Hedley and Watson1984: 8; Gong Reference Gong Gerrit1984].

ESIR certainly has a thicker conception of international society than WPT since it is attuned to the central importance of conflict and contestations by Third World actors through which international society expanded. Nonetheless, it ultimately attributes decolonization to the willingness of Europeans to allow non-European states to enter international society, thus overlooking the ways in which European colonial powers strenuously resisted the breakup of their empires. Furthermore, at stake in the “globalization” of international society was not simply a numerical expansion but a profound qualitative transformation that fundamentally altered the texture of international society, including reigning conceptions of moral purposes of the state, functions of international society, racial hierarchies and human rights [Reus-Smit and Dunne Reference Reus-Smit, Dunne, Dunne and Reus-Smit2017: 28; O’Hagan Reference O’hagan, Dunne and Reus-Smit2017: 196]. In short, ESIR does not specify the counterhegemonic strategies and struggles that enabled the creative production and authorization of new international discourses and practices. Rather, it attributes “the revolt against the West” by Third World states and anticolonial movements to ideational changes among colonized elites brought about by the spread of Western liberal and nationalist ideals [Bull Reference Bull, Bull and Watson1984]. Anticolonial discourses are thus situated as arising not from the unique perspectives and lived experiences of colonized peoples but as adopted and derivative ideas.

Finally, a steadily burgeoning cross-disciplinary scholarship, which I characterize as International Third Wordlist Approaches (ITWA), is examining how Third World actors shaped human rights, national self-determination, and development agendas in international organizations and forums [Barreto Reference Barreto2013; Burke Reference Burke2010; Getachew Reference Getachew2019; Go Reference Go2008; Grovogui Reference Grovogui Siba1996; Jensen Reference Jensen Steven2016; Liu Reference Liu Lydia2014; Prashad Reference Prashad2007; Rajagopal Reference Rajagopal2006; Reus-Smit 2013; Terretta Reference Terretta2012; Waltz Reference Waltz2001]. One of the aims of this scholarship is to throw light on Third Worldism, a political project of “active cooperation between political elites in the developing world to achieve an extremely ambitious, yet not wholly unrealistic, agenda of political and economic reordering on a global scale” [Byrne Reference Byrne Jeffrey2016: 6]. This scholarship has been pivotal in emphasizing the role of Third World states in articulating and institutionalizing anticolonial norms in international forums.

For example, Roland Burke [Reference Burke2010], Steven Jensen [Reference Jensen Steven2016] and Meredith Terretta [Reference Terretta2012] demonstrate that Global South actors were central in the fight for decolonization through articulating it as an issue of international human rights. Julian Go [Reference Go2008: 216-220] argues that the global consolidation of the principle of national self-determination by anticolonial movements was pivotal in (re)shaping the post-war global field, ensuring not only that the new superpower, the United States, would not engage in acquiring colonies but would also eventually cease to support its European colonial allies. More recently, Adom Getachew [Reference Getachew2019] has characterized Third Worldist struggles over national self-determination at the UN as a novel project of “worldmaking” that sought to fundamentally reconstitute the old European imperialist world order. Finally, the critical scholarship generated by the Third World Approaches to International Law (TWAIL) collective has demonstrated both the historical entanglements between European imperialism and international law and the counter-hegemonic struggles to appropriate and transform international law towards the ends of global justice and equality [e.g. Anghie Reference Anghie2005; Pahuja Reference Pahuja2011; Rajagopal Reference Rajagopal2006].

ITWA recognizes that the “expansion” of international society through decolonization was a deeply contentious process that was actively resisted by Western colonial powers. It is thus attuned to the role of conflicts and contestations in international forums as mediating the diffusion of the norm of national self-determination. In contrast to ESIR, it also gives a constitutive role to international forums and Third World agency in bringing about the end of colonial empires. Yet, as I discuss next, ITWA can benefit from a greater specification of the relational and dialogical aspects of decolonization struggles at the UN.

Decolonization Struggles at the UN: A Relational and Dialogical Approach

There is a tendency in the above-mentioned approaches to attribute the legitimization of the norm of self-determination at the UN to an “exogenous” variable: the number of decolonized states. In this perspective, as the number of decolonized states increases in the UN, the latter are able to work together to delegitimize colonial rule through their voting behavior. While such an account appears incontrovertible on the surface, it essentially attributes a causal role to the numerical expansion of UN membership, in the process underspecifying the institutional processes through which power in numbers is produced and exerted. Certainly, newly decolonized states are doing things at the UN in such accounts. However, the outcomes of their actions and interactions are predetermined. Furthermore, these accounts implicitly posit that the primary driving force for Third World countries and anticolonial movements was the improvement of their own position within an international society that otherwise remains unchanged. This overlooks the ways in which decolonization struggles entailed contestations over norms concerning sovereignty, development, and human rights [Hall Reference Hall, Dunne and Reus-Smit2017: 351-352; Rajagopal Reference Rajagopal2006].

A relational and dialogical perspective shows that decolonization struggles entailed a re-articulation of the “essential” attributes of states and international society. The core of relational sociology lies in its attention to dynamic, ongoing relations as ontological building blocks of social reality [Emirbayer Reference Emirbayer1997]. Relationalism is fundamentally opposed to “substantialist” approaches that treat social entities—be they individuals, groups, organizations, states, or international organizations—as “preformed” fundamental units of social analysis that “pursue internalized norms given in advance and fixed for the duration of the action sequence under investigation” [Emirbayer Reference Emirbayer1997: 284]. Instead, the seemingly essential attributes of social entities—identities, modes of agency, norms and ideas—are emergent properties of the social relations in which they are embedded [Somers Reference Somers Margaret1994; Somers and Gibson Reference Somers Margaret, Gibson and Calhoun1994; Steinberg Reference Steinberg Marc1999; Tilly Reference Tilly1995; Mische Reference Mische, Scott and Carrington2011]. Relationalism posits that entities are constituted through interactions and transactions that are dynamic and unfolding, and that the outcomes of these interactions cannot be reduced to causal exogenous variables that are deemed to be acting upon already-constituted social entities [Abbott 1992].

From a relational perspective, attributes of modern states are produced and reproduced through dynamic and ongoing processes and relations. For example, territoriality is not an ahistoric and asocial property of the modern state but is produced through the spatio-temporal ordering of “society” to coincide with the territory of the state [Jackson and Nexon Reference Jackson Patrick and Nexon1999: 300]. Similarly, the emergence of ideas about the “state project”—what the state can do within its territorial boundaries—cannot be explained without reference to the “international realm” that the state interacts with in a myriad of ways. In this vein, Julian Go and George Lawson [Reference Go, Lawson, Go and Lawson2017: 23] propose “methodological relationalism” that conceives of political forms as “entities-in-motion” that are “produced, reproduced, and breakdown through the agency of historically situated actors.” The international sphere is one of “interactive multiplicity” wherein “diverse interactions […] take place between historically situated peoples, networks, institutions, and polities.”

The UNGA was a critical site in bringing about the transformation of states and international society through decolonization straggles championed therein by anticolonial countries. Although it appears as a single unified actor when it undertakes measures such as adoption of resolutions, the UN is a social arena in which various countries vie with each other to normalize particular discourses of international-legal import, establish hierarchies among different international norms, and achieve concrete outcomes vis-à-vis the adoption of resolutions [Claude Reference Claude Inis1984: 9-13; Hurd Reference Hurd2020; Koskenniemi Reference Koskenniemi2011; Pahuja Reference Pahuja2011: 32-37]. The UNGA, in particular, is the site—in Bourdieusian terms, a specific subfield within the international political field—for the relational emergence of competing subject positions from which all states choose in the course of voting for proposed draft resolutions. In this conceptualization, actors in the UNGA are engaged in practices that are fundamentally relational since they are oriented towards other actors in this institutional field [McCourt Reference McCourt2016: 479]. With respect to decolonization struggles, a relational perspective demonstrates that this process, ostensibly centered on issues of colonialism, national self-determination and decolonization, entailed acute contestations over identities and functions of states, societies and international society in the emerging post-war world.

In order to throw light on decolonization struggles at the UN, I draw on a particular strand of relationalism—dialogism—that is attuned to the constitutive impact of discursive struggles on social outcomes [Bakhtin Reference Bakhtin1981; Smith Reference Smith, Bell and Gardiner1998; Steinberg Reference Steinberg Marc1999]. A dialogical perspective approaches discourse as “an ongoing process of social communication” [Steinberg Reference Steinberg Marc1999: 743]. Discourse takes shape within concrete social contexts that limit what can be expressed and understood. In other words, discourses do not exist prior to, but take shape through, communication. However, words and ideas constituting discourse are multivocal—“many words, phrases, and utterances do not have one unambiguous meaning but often have multiple meanings given their particular contextual use” [Steinberg Reference Steinberg Marc1999: 745]. Discourse and meaning are actively created through the specific mixing of different words and ideas into different narratives, or subject positions, in concrete social spaces by social actors who occupy different positions in the social hierarchy.

Discourse is produced on “a dynamic, conflict-ridden cultural terrain” [Steinberg Reference Steinberg Marc1999: 748]. This terrain is shaped in large part by the “historically specific repertories” which form the basic template upon, and through which, subsequent creative acts of meaning making occur [Spillman Reference Spillman1995: 140-141]. Central to communication is the fight over fixing meanings. Social actors engage in “discursive struggles” to establish dominant understandings about power, hierarchy and difference—or whatever may be at stake in a particular social field [Bourdieu and Wacquant Reference Bourdieu and Loic1992]. The aim is to establish discursive domination by robbing words of their multivocality.

A dialogical perspective draws attention to the centrality of rhetorical struggles in international society. As Krebs and Jackson [Reference Krebs Ronald and Jackson2007: 36] argue, “rhetoric is central to politics, even when politics takes the form of war.” Furthermore, rhetoric is not “epiphenomenal” but shapes outcomes. Its aim is not always, or just, to “persuade” or change minds, but is often to “leave their opponents without access to the rhetorical materials needed to craft a socially sustainable rebuttal.” It seeks, in other words, to talk opponents into a corner. Krebs and Jackson draw on Michael Billig to argue that rhetoric is an active act of position-taking in a two-sided controversy. Consequently, none of the positions can be fully comprehended without examining the positions which are being criticized, for “without knowing these counter-positions, the argumentative meaning will be lost” [Billig Reference Billig1987: 91]. Such an understanding moves analytical focus away from subjectively held norms and beliefs and towards contexts of deliberation and the exercise of rhetorical power. From a Bourdieusian perspective too, discursive struggles are not undertaken to persuade, motivate, shame or pile opprobrium, although they may have these effects. Rather, the aim is to acquire symbolic power through legitimizing certain “visions and divisions” of society that in turn structure distribution of resources [Bourdieu and Wacquant Reference Bourdieu and Loic1992; Swartz Reference Swartz2013].

A dialogical approach demonstrates that decolonization struggles at the UNGA were shaped by the emergence of competing subject positions that drew on the same set of keywords, in particular human rights and development, but infused them with different meanings. In the process, they produced two distinct historical narratives regarding the nature of European presence in non-European countries. These differing analyses were premised on distinct understandings about the identities and functions of the state and international society in the emerging international order.

Why Algeria?

The Algerian independence movement was spearheaded by the revolutionary National Liberation Front (FLN) that began its offensive in November 1954. Although the resistance was carried out in Algeria through guerrilla warfare, it was crucially oriented towards an international audience, in particular the UN, from the very start [Byrne Reference Byrne Jeffrey2016; Connelly Reference Connelly2002]. Reference to the UN Charter was made in the first public statement issued by the FLN, in which it enumerated one of its core objectives as “assertion, through the United Nations Charter, of our active sympathy towards all nations that may support our liberating action” [Evans Reference Evans2012: 114-117]. This objective was part of the FLN’s broader goal of “restoration of the Algerian state” both through a “national struggle” and the “internationalization of the Algerian problem.” Algerian revolutionaries engaged simultaneously in local armed resistance and international diplomacy and activism, both at the UN and beyond [Bedjaoui Reference Bedjaoui1961; Byrne Reference Byrne Jeffrey2016; Connelly Reference Connelly2002; Johnson Reference Johnson2016; Kinsella Reference Kinsella Helen2011; Klose Reference Klose2016]. Historian Matthew Connelly has thus aptly termed the FLN’s successful fight over “world opinion and international law” as constituting “a diplomatic revolution” [Connelly Reference Connelly2002].

The FLN’s trust in the UN was not misplaced. In orienting its actions towards the UN, the FLN knew it had a number of important allies in this august international body.Footnote 4 From the start, the FLN had explicitly situated its struggle “within the vast movement of liberation of the African and Asian peoples” [Bedjaoui Reference Bedjaoui1961: 85]. Its members also participated in the April 1955 Summit of Asian-African Heads of State in Bandung, Indonesia alongside their Moroccan and Tunisian counterparts where they formed a single delegation with observership status [Byrne Reference Byrne Jeffrey2016: 40-41]. The cause of North African decolonization was endorsed in the conference’s Final Communiqué [Asian-African Conference (1955) 2009: 99].

For seven years between 1955 and 1961, diplomats from the Global South fought tooth and nail at the UN to put pressure on France to decolonize Algeria. These allies took cues from the FLN’s strategic actions and wove them into elaborate narratives depicting the standpoint of Algerian revolutionaries. The aim was to draw on international legal norms to stringently contest France’s claim to Algérie française and advocate for Algérie algérienne. Although it claimed to be indifferent to debates on Algeria at the UN on the grounds that Algeria was an integral part of France and hence its domestic concern, France too was deeply attuned to the UN [Connelly Reference Connelly2002: 6; Thomas Reference Thomas2001: 92-93; Klose Reference Klose2013: 2014-2019]. Thus, some of the most critical decisions undertaken by France on Algeria were announced to coincide with the opening of the UN’s annual sessions. Furthermore, even though France boycotted nearly every UN session in which the Algerian question was debated, its allies diligently presented France’s point of view to the international community by taking the most recent proclamations by French authorities as their point of departure. Ultimately, France lost hold of Algeria despite crushing FLN militarily. The pressure mounted by Algeria’s allies at the UN is a central part of Algeria’s struggle for independence and affords an opportunity to theorize the role of ideological contestations, international legal interpretations and historical narratives in the international politics of decolonization.

The Algerian Question at the United Nations

The Algerian question was debated at the UN for seven years in a row, starting in 1955 when a group of fourteen Asian and African countries petitioned the UN Secretary-General to include the issue on the agenda of the UNGA.Footnote 5 The Algerian question arose at a time when UN membership was rapidly increasing through the entry of Asian and African countries. In 1955, the UN admitted 16 new member states, increasing the number from 60 to 76. In the next two years, six additional states were admitted into the UN. In 1960, “the year of Africa,” 17 African countries became UN member states. Many of these newly decolonized states seamlessly joined Algeria’s allies to advocate the cause of Algerian independence.

The debates on the Algerian question produced two distinct and competing discourses regarding the ongoing conflict in Algeria: an anticolonial internationalist discourse and a metrocentric civilizational discourse Footnote 6 (see Table 1). Each was constituted through differing responses to three key questions: the question of admissibility (was the Algerian question an international concern or a domestic French matter?); the question of naming (was the Algerian anticolonial resistance led by FLN a legitimate nationalist movement or a terrorist movement?); and the question of development (had the French presence been beneficial for Algerians or had it harmed Algeria’s development prospects?) My analysis of the production of these discourses depicts the contentious discursive processes surrounding the international delegitimization of colonialism. The analysis also highlights the fact that this delegitimization entailed a critical re-envisioning of the identity of both the state and international society.

Table 1 Discursive Struggles over The Question of Algeria at the UNGA

The Question of Admissibility

The first contentious issue centered on the question of the admissibility of the Algerian question on the UNGA agenda. This in turn hinged on the broader issue of the role of international society in recognizing the legitimacy of anticolonial movements. The very first sentence of the first petition to the UN held that “The right of self-determination occupies a position of decisive importance in the structure of the United Nations.”Footnote 7 Self-determination was “a prerequisite to the full enjoyment of all other fundamental human rights” and its denial “a potential source of international friction.” Note that by linking the issue of self-determination with international security, the petitioners effectively ensured that it would fit within the competencies of the First Committee of the General Assembly that deals with issues of international security. While the Fourth Committee of the General Assembly deals with issues of decolonization, these at the time were limited to the UN’s International Trusteeship System. The introduction of the Algerian question thus constituted an attempt to broaden the competencies of the UNGA with respect to colonial questions, and situate these as political, as opposed to technical and legal, matters.

In response, the UN Secretary-General placed the issue before the General Committee, the body responsible for setting the General Assembly’s agenda. A diagnostic struggle ensued that was repeated almost annually: was the Algerian question a domestic or an international matter? What was the overriding international legal principle that could decide the issue? Hervé Alphand, France’s ambassador to the UN, drew on Article 2 (7) of the UN Charter to argue that the UN was not competent to consider the issue of Algeria. This article explicitly states: “Nothing contained in the present Charter shall authorize the United Nations to intervene in matters which are essentially within the domestic jurisdiction of any state.” Alphand held that the Algerian question fell within France’s domestic jurisdiction since Algeria “formed an integral part of France on equal footing with the Ile-de-France, Brittany or Auvergne.”Footnote 8 Certainly Algeria had been conquered but that was also true of other parts of France such as Flanders and Burgundy. Diplomats from the UK and the US, among others, endorsed this argument regarding domestic jurisdiction.Footnote 9

Diplomats from the Global South held that the issue was not that Algeria had been conquered by force but that, as the Pakistani delegate argued, “French presence in Algeria has been maintained by force.”Footnote 10 The Syrian delegate argued that Algeria was not an integral part of metropolitan France since it “has nothing more than a colonial status.”Footnote 11 The Lebanese delegate explicitly stated that the “Algerian Arab does not enjoy the rights of French citizenship” and “the so-called departments of Algeria do not receive the same treatment which France reserves for her departments in Europe.”Footnote 12 India’s Krishna Menon noted that the French constitution itself made a distinction between metropolitan France and its “overseas territories”, conceiving of the two as a “Union” and not a single, indivisible France.Footnote 13

Algeria’s allies drew on a number of UN Charter clauses to make the case for the admissibility of the Algerian question [Alwan Reference Alwan1959: 21-30]. Prominent among these were the preamble of the UN Charter with its references to “fundamental human rights,” the “dignity and worth of the human person,” and “equal rights of men and women and of nations small and large”; the first article of the Charter that aims “to develop friendly relations among nations based on respect for the principle of equal rights and the self-determination of peoples”; and Article 55 that aims at “the creation of the conditions of stability and well-being which are necessary for peaceful and friendly relations among nations based on respect for the principle of equal rights and self-determination of peoples.”Footnote 14 Furthermore, the UNGA had the authority to address the Algerian question by virtue of Article 2 (2) of the UN Charter that allowed it to discuss any question relating to maintenance of international peace and security, and to make appropriate recommendations.Footnote 15

Algeria’s allies drew on the endorsement of the cause of North African independence by 29 countries present at the Bandung Conference. These countries represented “more than half of humanity,” and their endorsement represented the deep and widely felt concern of the international community.Footnote 16 A number of delegates drew the Assembly’s attention to the numerous precedents at the UN relating to human rights violations, notably the treatment of people of Indian origin in South Africa; apartheid in South Africa; and human rights violations in Bulgaria, Hungary and Romania, which were part of the Soviet bloc.Footnote 17 Note that the implicit claim here is that the UN ought to represent world opinion and not the interests of powerful countries. This claim, however, was explicitly rejected by Alphand, who argued that the UN could not be tethered to “the will of shaky majorities” by virtue of Article 2 (7) of the UN Charter. Similarly, Belgium’s prominent representative, Paul-Henri Spaak, ominously warned against the transformation of the UNGA into “a sort of international court”, which would turn it into “a chaotic and nondescript body in which no rule would ever be respected and any individual country would be at the mercy of decision taken by fortuitous majorities.”Footnote 18 Spaak openly expressed his disdain at the prospect of a country of France’s stature being held accountable by a world body consisting of a non-European majority.

This vision of the UN was completely contrary to that held by Third World countries, many of which had recently concluded their own anticolonial struggles. “This question [of Algeria]”, stated the Egyptian delegate, “transcends by far the mere matter of whether we should include just another item on the agenda. It is infinitely bigger than that. It is indeed a challenge to the vision of the United Nations and a vital link in the chain of events which will form its history and decide its future.”Footnote 19 The Assembly was in turn reminded that the eminent French jurist, René Cassin, who had been a key figure in the drafting of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR), had famously held that, with the adoption of the UDHR, the question of human rights ceased to be a domestic matter.Footnote 20 Charles Malik, one of the other critical figures in the drafting of the UDHR, who was then serving as Lebanon’s ambassador to the UN, argued that the UN was competent to examine the situation in Algeria since it was “a problem involving such fundamental issues as basic human rights and freedoms, particularly the right of self-determination of peoples.”Footnote 21

The position of Algerian allies prevailed. Despite the recommendation of the General Committee to not include the Algerian question on its agenda, the UNGA voted otherwise, prompting furious French denunciation.Footnote 22 The Algerian question would firmly stay on the agenda of the UNGA until Algeria’s independence in 1962, thus allowing European colonialism to be critically appraised by the international community of states.

The Question of Naming

Throughout the debate on the Algerian question across seven UN sessions, Algerian allies minutely described atrocities being committed by the French army in response to Algeria’s independence movement. The first petition to the UN in 1955 drew attention to mass arrests, outlawing of national political parties, imposition of censorship, banning of newspapers and the seizure of homes, all of which constituted human rights violations.Footnote 23 The Algerian independence movement was described by the Egyptian delegate as “a large-scale nationalist uprising”Footnote 24 while the Indonesian delegate described it as a “colonial struggle” and “a fight for the self-respect and for the basic human rights guaranteed by the United Nations Charter.”Footnote 25 This designation was actively contested by France and its allies. According to France, the situation in Algeria constituted a “rebellion aiming at the dismemberment of the territory of France” by “terrorist bands.”Footnote 26 Algeria was beset by “forces of violence and destruction.”Footnote 27 This was echoed by New Zealand’s delegate who likened Algerian revolutionaries to a “secessionist minority.”Footnote 28 The Colombian representative described the situation in Algeria as “civil strife” of the type undertaken by “revolutionary or separatist movements”,Footnote 29 while the UK’s Pierson Dixon referred to the conflict as an “internal dispute.”Footnote 30

The naming of the Algerian movement—was it a legitimate anticolonial nationalist movement or a domestic terrorist movement seeking to dismember France?—was critical for both the French and Algerian sides in depicting the military tactics of both the FLN and the French army. If, as it claimed, the FLN was indeed engaged in a legitimate international dispute, then the rules of war as defined by the Geneva Conventions of 1949 would become applicable. This would allow the FLN to both justify its own use of violence and counter France’s much more violent and extreme “pacification” measures. On the other hand, if France could convincingly situate the FLN as a domestic terrorist outfit, then it could successfully cushion criticisms of the disproportional use of force being levied at it by the FLN’s allies at the UN. In fact, the FLN, and subsequently the Provisional Government of the Algerian Republic (GPRA) that was formed in 1958, made strenuous efforts to demonstrate their respect for, and adherence to, the 1949 Geneva Conventions [Bedjaoui Reference Bedjaoui1961; Kinsella Reference Kinsella Helen2011: 127-132].Footnote 31

Consequently, both sides at the UNGA made considerable rhetorical efforts to establish their positions as the authoritative ones. Allies of the Algerian independence movement directly received prepared accounts of the ongoing situation on the ground in Algeria from FLN officials working from their New York office.Footnote 32 Criticisms of French counterinsurgency efforts in Algeria were primarily based on information and statistics provided by Western media sources, most often The New York Times and Le Monde, to avoid charges of biased accounts. It was also critical that Algeria’s allies be able to point to “the French press” itself as well as the occasional criticisms voiced at the French National Assembly, or by a French political party, to support their arguments.Footnote 33 UN delegates also drew attention to criticisms being voiced by prominent French intellectuals (as, for example, in the famous Manifesto of the 121 signed by Jean-Paul Sartre) as well as prominent US politicians (such as John F. Kennedy, who spoke in favor of the Algerian cause on the Senate floor in July 1957).Footnote 34 The aim throughout was to display rhetorical power through the force of incontrovertible “facts” that would corner France and its allies.

A recurring theme during the debates was the disproportionate use of force by France to counter Algerian resistance. The Phillipeville massacres of August 1955 were cited as an example: in response to the FLN’s killing of 123 people (mostly Europeans), French forces responded with collective reprisal, razing whole villages to the ground and killing thousands of Muslims in the process (the FLN placed the number of Muslims killed at 12,000).Footnote 35 The Genocide Convention was invoked to argue that French policies of “pacification” constituted genocide.Footnote 36 Attention was drawn to the ongoing suffering, use of torture, heavy loss of human lives, and the forced displacement of thousands of Algerians and their placement into prisons, internment and “regroupment” camps. The latter referred to the French practice of displacing populations and regrouping them in new settlements so as to isolate the FLN fighters and deprive them of critical resources such as access to food and family members, and to pursue a shoot-on-sight, scorched earth policy in emptied areas [Klose Reference Klose2013: 167].

The issue of torture was especially pronounced. The use of torture had been a routine aspect of French rule in North Africa in the inter-war years. For example, it was systematically employed to interrogate Vietminh prisoners during the Indochina war [Cohen Reference Cohen William2003: 233]. News of the use of torture by French authorities in Algeria first appeared in France in January 1955 [Evans Reference Evans2012: 139]. However, these early revelations did not cause a stir. Subsequently, the publication of eyewitness accounts by both French perpetrators and recipients of torture met with wide criticism and disgust in France [Ibid.: 169-170]. These domestic French debates on the use of torture in Algeria, and the concrete evidence on which they were based, were brought to the twelfth UN session (1957-1958). Condemnation of French counter-insurgency measures by prominent French intellectuals and Catholic religious leaders were read verbatim to draw attention to policies of torture, summary executions, and concentration and regroupment camps. These were then framed as violations of UDHR and the UN Charter, and likened to Nazi atrocities.Footnote 37 Delegates drew on French sources such as publications by the Comite de resistance spirituelle and the Paris Bar to show that torture was a daily occurrence in Algeria.Footnote 38 They also drew on reports of various inquiry commissions set up by the French government itself that were routinely leaked to the French press, as well as on condemnations by international monitoring bodies such as the International Commission against Concentration Camp Practices.Footnote 39

The 1960 petition to the UN Secretary-General, signed by 25 countries and requesting the inclusion of the Algerian question on the UNGA agenda, noted that one million Algerians had thus far been subjected to displacement and placed in regroupment camps, internment camps and prisons, while 250,000 Algerians were present in Tunisia and Morocco as refugees.Footnote 40 During the subsequent debate, the Jordanian delegate pointed out that, since 1956, more than 300 Algerian combatants had been condemned by French tribunals and executed while, in the month of July 1960 alone, 11 Algerians had been executed.Footnote 41 France, the Tunisian delegate held, was showing complete disregard for “the elementary rules governing relations between belligerents and treatment of prisoners.”Footnote 42 France thereby stood, argued India’s delegate, in violation of the Geneva Convention’s decrees on the treatment of prisoners of war.Footnote 43

The Question of Development

A central element of the anticolonial internationalist discourse was the argument that the condition of being under colonial rule was inherently antithetical to fundamental human rights, and that it delayed development. The backdrop of this line of reasoning was the claim by France that its “civilizing mission” had significantly improved the condition of Algerians, and that severance from France through independence would return Algerians to a state of backwardness.Footnote 44 “Development” and “human rights” were thus key terms of the debate for both the French and Algerian sides at the UNGA. The critical issue hinged on representing the historical nature of France’s presence in Algeria by appropriating these key terms. While the question of admissibility drew forth competing visions of international society, that of development highlighted competing visions of the identity of the modern state, especially with respect to the sources of state sovereignty and the state’s responsibilities towards its citizens.

In one of the opening debates, Antoine Pinay, France’s Minister of Foreign Affairs, told the UNGA that “France will not tolerate insults or slanders against its civilizing work” from countries that subjected their own minorities to discriminatory treatment, and had high rates of poverty, illiteracy and infant mortality.Footnote 45 The Algerians, he suggested, were far more developed, and enjoyed more human rights, than peoples in Third World countries.Footnote 46 This line of reasoning was carried further in subsequent UNGA sessions by Christian Pineau, who succeeded Pinay as Foreign Minister, and Jacques Soustelle, a parliamentarian and former Governor General of Algeria. Soustelle, provided with dossiers compiled by the French interior ministry on France’s development measures in Algeria, had been specially instructed by Prime Minister Guy Mollet to join France’s UN delegation [Klose Reference Klose2016: 324; Le Sueur Reference Le Sueur James2001: 197]. In elaborate speeches, the two diplomats described French efforts in bringing “medical, economic and social progress” to Algeria.Footnote 47

Pineau, for example, noted the decline in infant mortality rates under French rule. Deploying a language that was fast becoming outdated, he held that “the [resultant] population increase was due to the civilizing mission of France.”Footnote 48 He also drew attention to the rise in agricultural yields through the spread of modern education among Algerian farmers; the increased production of electricity; the development of infrastructure (dams, canals, roads, harbors, airfields, etc.); the increase in consumption; greater access to medical care and public education; and the development of new industries such as coal, iron and phosphate.Footnote 49 Clearly, there were imbalances in certain areas between Europeans and Muslims as, for example, in land distribution and literacy rates. However, strenuous efforts were being made by the French government to eliminate these. Pineau wondered what would become of Algeria “if it were to become a foreign land pledged to fanaticism and, by its very poverty, open to communism.”Footnote 50 The invocation of the supposed threat posed by Islam and communism was a central component of the metrocentric civilizational discourse.

In response, diplomats from the Global South delved both into the nature of colonial rule and the specifics of French rule in Algeria to rebut France’s claims regarding colonial development.Footnote 51 Notable here is the speech by El Mehdi Ben-Aboud, Morocco’s first Ambassador to the United States, which elaborated on what Pierre Bourdieu in his work on Algeria refers to as the “colonial system.” This refers to the idea that colonial society operates through “an internal necessity and logic” constituted by the total domination of the colonized people by the colonized [Bourdieu Reference Bourdieu1961: 1]. Perhaps not incidentally, French colonial rule in North Africa has proved to be an especially fertile ground for some of the most sophisticated analyses of the colonial situation [e.g. Fanon Reference Fanon1961, Reference Fanon1965; Bourdieu Reference Bourdieu1961; Memmi Reference Memmi1957].

Colonialism, Ben-Aboud argued, proceeds through depriving the colonized peoples of their freedom.Footnote 52 This loss of freedom produced a “permanent struggle” between the “conqueror” and the “conquered”, which in turn necessitated the use of force by the colonizer to maintain basic order. Ben-Aboud argued that “the form of domination was total in a colonialist system.” It included “political, cultural and social domination, as well as domination in religious matters.” The multidimensional aspect of colonial domination indicated that “the attempt to stop intellectual development paralleled the attempt to stop the material progress of the population.” Although France spoke of reforms “progress was perpetually blocked in order to justify perpetual colonization.” Consequently, “no colony had become a modern nation within the framework of and with the assistance of colonialism. The territory was always developed unilaterally for the benefit of the European element; the indigenous population was chained in poverty, ignorance and fear.”

Note the centrality of the idea of development in both the metrocentric civilizational and anticolonial internationalist discourses. To understand its resonance at this juncture, it is important to consider the history of the development idea. In a bid to legitimize new forms of colonialism that were instituted through the Mandates System of the League of Nations, European colonial powers inserted clauses about development, both in the Covenant of the League of Nations and in the individual mandatory agreements––all of which pertained to the former colonies of the Ottoman and German empires that were distributed among Western European colonial powers at the end of WWI [Pedersen Reference Pedersen2015]. For example, Article 22 made “the well-being and development” of colonial peoples the responsibility of mandatory powers.

Although older colonial possessions such as India and Algeria were not subject to these legal agreements, development discourse and policies were increasingly deployed in the inter-war and post-war years to legitimize colonial ventures at a time when there was a steady increase in the intensity and volume of anticolonial activity [Cooper Reference Cooper, Cooper and Packard1997; Unger Reference Unger, Macekura and Manela2018]. The British passed the Colonial Development Act in 1929 that would provide one million pounds each year to improve colonial infrastructure, and the Colonial Development and Welfare Act in 1940 that was directed towards measures such as improving health services and educational facilities. France passed its own Fonds d’investissement pour le développement économique et social (FIDES) in 1946. At the same time, measures were taken by both Britain and France to give greater voice to local populations through improved electoral participation and legislative and financial autonomy. Many of France’s economic and social development efforts in Algeria that it enumerated at the UN were undertaken within the FIDES framework.

Furthermore, the UN Charter itself cleared space for the scrutinization of human rights and development record in the colonies. Both the League of Nations Mandates System and the United Nations Trusteeship System were formulated within the framework of European imperial rule and rested on the premise of the West’s “civilizing mission” [Mazower Reference Mazower2009]. However, there were critical differences between the two, with the most striking being the incorporation into the UN Charter of Chapter XI titled “Declaration Regarding Non-Self-Governing Territories” [Claude Reference Claude Inis1984: 357-377]. Chapter XI made it an obligation for all non-self-governing territories—both previous Mandates (now Trusteeships) and colonial territories—to accept the obligation of reporting to the UN on their developmental efforts [ibid.: 361]. This obligation, which was a concession wrung from the colonial powers by anticolonial actors at the UN’s founding conference in San Francisco, was based on the notion that all colonial possessions constituted a sacred trust. Chapter XI was thus critical in clearing space for anticolonial delegates at the UNGA to scrutinize France’s development record in Algeria. More broadly, it led to “a battle between contending forces” as the question of decolonization became “the subject of intensive political debate and complex maneuvering” [Ibid.: 365].

In this context, anticolonial diplomats from the Global South undertook a systematic critique of France’s various post-war development measures in Algeria at the UNGA. The Syrian delegate led the charge, arguing that, while colonial rule did result in notable developments in some geographical and policy areas, its driving force was to make Algeria more productive in order to benefit French interests, thus enriching European colons at the expense of Algerians.Footnote 53 The French had appropriated the most productive lands, leaving the Algerian population relatively backward. The Algerians lacked food security since the land appropriated by the French was geared towards export-oriented viticulture with the result that Algeria was unable to meet the food requirements of its rapidly exploding population. Evidence was provided to showcase differentials in wages, caloric intake, access to health care and education, and employment rates between colons and Muslim Algerians. Ultimately, the Syrian delegate argued, “the sole effect of the civilizing mission of the Western world in the colonial era had been to turn countries of ancient civilization and culture into under-developed regions of the world.”Footnote 54

With respect to the idea that France was engaged in the political development of Algerians, numerous delegates noted that the Statute of 1947 had legislated a double electoral college whereby an equal number of seats were reserved for French and Algerians even though the latter outnumbered the former by ten to one.Footnote 55 French rule, they argued, had also delayed the cultural development of Algerians. The French policy of assimilation, codified in the Senatus-Consulate of 1865, that made the renunciation of “language and religion” (i.e. Arabic and Islam) a condition for becoming French was roundly criticized.Footnote 56 It was noted that Arabic was given the status of a foreign language while French was made the official language of the country. The French had completely eradicated Algerian history from educational curricula, instead teaching Algerian schoolboys to parrot that “Our ancestors were Gauls.”Footnote 57 Yet, as the Saudi Arabian delegate summarized, “after 125 years of French rule only 60,000 Moslems have grammar school certificates” while about 90% of Algerians were illiterate.Footnote 58

Despite these criticisms at the UNGA, the French authorities continued to make efforts to develop Algeria until its independence. Their efforts included the Soustelle plan aimed at agricultural modernization, General de Gaulle’s much-vaunted Constantine Plan aimed at economic reforms including land redistribution and job creation, and related experiments at creating “model” or nouveaux villages featuring schools, sports facilities, and swimming pools.Footnote 59 Pro-Algerian delegates at the UNGA clearly recognized that these efforts were part of France’s diplomatic warfare, responding with “too little too late” sentiment. Through their sustained critique of French policies in Algeria at the UNGA, delegates from the Global South sought to establish a new conception of the state. Legitimate statehood, it was held, entailed a sincere concern for the economic, social and cultural development of the territory under the state’s control. It was precisely these conditions that could not be met by the colonial state in Algeria due to the structural constraints imposed by the colonial system.

Adopting Resolutions: Beyond the West and the Rest

The above discussion has analyzed the contentious debates on Algeria that were held at the UN. This section moves the analysis forward by examining the outcomes of these debates, focusing specifically on the emergence of two main camps: a majority camp supporting Algeria’s allies, and a minority camp supporting the French position. The specific aim here is to demonstrate that the two camps did not fully align with the “West” and “the Rest” dichotomy that pervades much scholarship.Footnote 60 In pursuing this line of argument, I seek to demonstrate that being situated in the Global South did not necessarily lead to support for anticolonial causes. Similarly, being from the Global North did not preclude support for anticolonial movements. The power of anticolonial internationalist discourse lay precisely in its ability to transcend this divide by drawing on international legal norms and principles. It was thus not a parochial discourse animated by narrow-minded hostility to the West, as suggested by ESIL’s metaphor of “the revolt against the West.”

Algeria’s allies encountered significant difficulties in their struggles to pass resolutions affirming the right of the country to self-determination until 1960, when the first substantive resolution was adopted by a two-thirds majority. By this time, the UN had adopted two resolutions on the Algerian question. Both are striking for their brevity and non-committal nature. The first of these held that the “situation in Algeria” was “causing much suffering and loss of human lives” and expressed the hope that, “in a spirit of coo-operation, a peaceful, democratic and just solution will be found, through appropriate means, in conformity with the principles of the Charter of the United Nations.”Footnote 61 The next resolution, passed during the twelfth session in December 1957, went a step further by noting the offer of good offices made by Morocco and Tunisia, and expressing its “wish” for pourparlers (preliminary talks).Footnote 62 Neither resolution mentions France nor gives any indication of the nature of the conflict in Algeria. Both these mild resolutions, sponsored by France’s allies, with the US in the lead, were adopted after stronger resolutions sponsored by Arab and Asian countries were defeated [Alwan Reference Alwan1959: 61-65; Connelly Reference Connelly2002: 129-130; Horne Reference Horne1977: 247]. More strongly worded draft resolutions were adopted in the First Committee where a simple majority was required to move draft resolutions to the General Assembly. Ultimately, Asian and African states voted for milder resolutions on the principle that any resolution on Algeria was better than no resolution [Alwan Reference Alwan1959: 71].

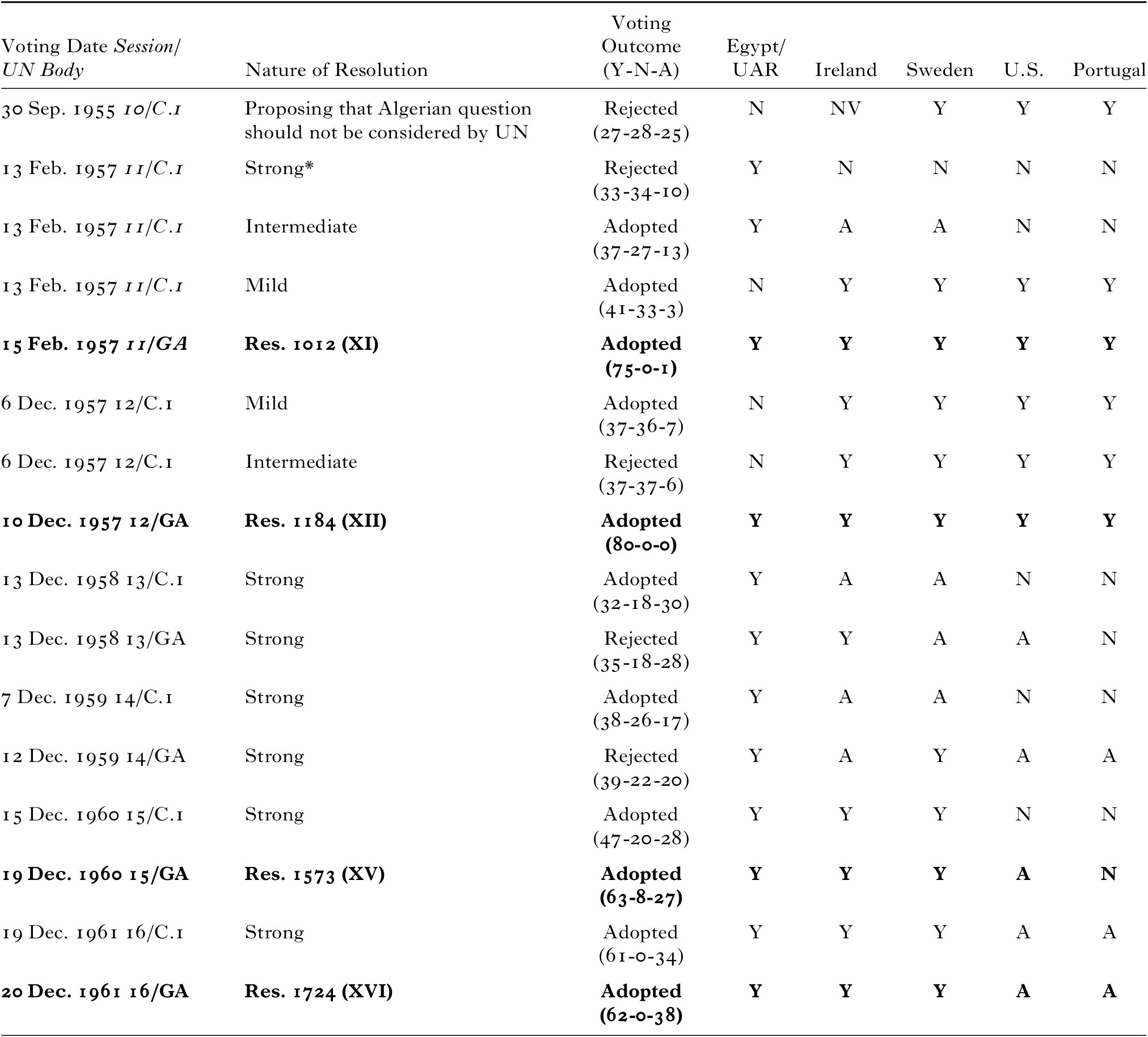

Table 2 lays out the voting outcomes of some of most critical votes undertaken during the debate on the Algerian question, paying particular attention to a number of countries. One group of countries, exemplified by Egypt/United Arabic Republic, consistently voted for strong, pro-Algerian independence resolutions throughout the seven years. These countries were often the sponsors of both petitions made to the UN Secretary-General to consider the Algerian question at the UNGA and of strong resolutions placed before the UNGA. Furthermore, their delegates were at the forefront of shaping the anticolonial internationalist discourse analyzed above. These countries include, among others, Egypt, Syria, Morocco, Tunisia, Saudi Arabia, Lebanon, Libya, and Pakistan.

Table 2 Key votes and voting behaviors of select states

* Strong: strongly pro-Algerian independence; Intermediate: compromise on strong resolution; Weak: pro-France

Y: yes; N: no; A: abstain; NV: no vote

A second voting trend is exemplified by the staunchest allies of France, notably Belgium, Portugal and Union of South Africa. As Table 2 demonstrates, Portugal consistently voted against strong resolutions until 1961, by which time Algeria’s independence from France had become a foregone conclusion. By and large, this group consistently voted against the strong resolutions proposed by African and Asian countries. Their delegates were pivotal in upholding the metrocentric civilizational discourse championed by France, particularly its interpretation regarding the question of admissibility. Portugal and South Africa, by virtue of their colonial empires and policies of apartheid respectively, were especially defensive about this question. South Africa’s policies vis-à-vis its majority Africans and non-European minorities, particularly Indians from South Asia, were already under scrutiny at the UN at the time of debates on the Algerian question. Portuguese colonialism in Africa would come under heavy scrutiny at the UN in the 1970s in the lead up to the disintegration of Portugal’s colonial empire in Africa.

A third trend is visible in the voting behaviors of European countries that sought to steer a middle ground. Notable here are Ireland and Sweden, both of which gently separated themselves from their above-mentioned European counterparts and began to slowly align themselves with Asian and African countries. For example, Ireland went from opposing a strong pro-Algerian independence resolution (in the 1956-1957 session) to abstaining in the middle years of the debate to finally voting for strong resolutions. Throughout, Irish policy was guided by concerns to maintain a friendly posture towards France while adhering, at the same time, to its anticolonial stance informed by its own history of British colonialism [Gillissen Reference Gillissen2008: 154].

Neither a member of NATO nor of the European Economic Community (EEC), Sweden too sought to adopt a middle ground in keeping with its self-identity as a partisan of humanitarian and charitable causes, particularly in Africa [Thompson Reference Thompson Andrew, Thomas and Thompson2018: 465]. Sweden went further than Ireland, voting in favor of a strong resolution affirming the right of Algerians to self-determination in the UNGA in 1958 (this resolution was not adopted). Although more restrained than Sweden, both Denmark and Norway too slowly distanced themselves from the metrocentric civilizational discourse by choosing to abstain, rather than vote against, strong resolutions. In the twelfth (1958) session, Norway, Canada and Ireland sponsored an intermediate resolution in the First Committee that eschewed the language of self-determination while maintaining that Algerians were “entitled to work out their own future in a democratic way” [Gillissen Reference Gillissen2008: 158]. This draft too was not adopted.Footnote 63

Particular mention must be made of the US, which abstained on a few strong resolutions, somewhat reversing its earlier policy of strongly supporting France by voting against resolutions sponsored by Arab and Asian countries [Zoubir Reference Zoubir Yahia1995: 74-75]. The intense diplomatic hostilities with France engendered by the US abstentions have been extensively documented by diplomatic historians [e.g. Connelly Reference Connelly2002; Wall Reference Wall2001]. These studies depict the immense symbolic importance of US voting behavior at the UN for all parties involved. On the whole, the US remained torn between its desire to support its NATO ally, the fear of anticolonial movements with leftist leanings, and the optics of maintaining an anticolonial position in light of the ongoing global Cold War [Go Reference Go2008; Westad Reference Westad Odd2005; Louis Reference Louis Wm2006].

Last, most of the 14 former French colonies in sub-Saharan Africa that gained independence from France in 1960, and were in a position to vote for the Algerian cause, did not do so, choosing instead to side with France.Footnote 64 Only two, Mali and Togo, voted with Asian and African countries for the draft resolution in the First Committee while the rest abstained on the grounds that the operative clause authorizing a UN-led referendum went against the spirit of the UN Charter. Even after this clause was excluded, only five (Central African Republic, Congo-Brazzaville, Dahomey, Mali, Togo) voted for the resolution while six (Upper Volta, Cameroon, Chad, Gabon, Ivory Coast, Madagascar) voted against it and three (Congo-Leopoldville, Niger, Senegal) abstained. In other words, “the more Francophile members” of the renewed French Community did not support the Algerian cause at the UN [Thomas Reference Thomas2001: 115; Cooper Reference Cooper2014: 372; Mortimer Reference Mortimer Robert1980: 13]. These countries were loudly condemned by Algerian allies for “choosing the imperialist camp.”Footnote 65

There is a tendency in existing approaches to situate the Third World as a unified historical actor. This overlooks the significant divisions that have always attended the quest for the formation of unified Third World projects [Mortimer Reference Mortimer Robert1980; Vitalis Reference Vitalis2013]. In the final instance, the Algerian question at the UN demonstrates the eventual triumph of the anticolonial internationalist discourse. At the time the final resolution on the “question of Algeria” was adopted by the UNGA in December 1961, the GPRA had been recognized by 35 countries and had recently attended the celebrated Conference of Heads of State or Government of Non-Aligned Countries, held in Belgrade in September 1961.Footnote 66 Algeria formally gained its independence from France on 19 March 1962, six months before the opening of the 17th annual session of UN. At this session, on 8 October 1962, Algeria was formally admitted as a member of the UN.

Since this article does not consider domestic foreign policy debates, it is not possible to present evidence of why countries vote the way they do. Were Irish diplomats really convinced by arguments presented by allies of the Algerian independence movement? Did these arguments have no effect on Belgium? Such questions cannot be answered on the basis of UN archives. However, as Krebs and Jackson [Reference Krebs Ronald and Jackson2007] argue, even with such evidence, it is notoriously difficult to determine what actors think and whether they have been persuaded or not. What can be readily seen at the UNGA is the voting behaviors of different states which, in the case of the Algerian question, attest to the power of the anticolonial internationalist discourse.

Conclusion

The UNGA was a critical site in the international delegitimization of European colonial empires. This process had two dimensions, one discursive and the other institutional. The first entailed a critique of concrete cases of colonialism, such as French colonial rule in Algeria, through the dialogical production of an anticolonial internationalist discourse. The metrocentric civilizational discourse underpinning France’s claim to Algeria was minutely dissected and its human rights violations put before the world. Allies of the Algerian independence movement demonstrated the existence of gross inequalities between Algerians and colons that were maintained through legal discrimination; European land appropriations and dispossession of Algerians; extreme poverty and malnourishment; under- and un-employment; high illiteracy rates; lack of political representation; and cultural displacement, among others. In so doing, they appropriated the development discourse of colonizers but in the process transformed it from a “discourse of control” to a “discourse of entitlement” [Cooper and Packard Reference Cooper, Packard, Cooper and Packard1997: 4].

Decolonization in its intellectual-ideological dimension not only entailed an affirmation of the international legal norm of national self-determination—the idea that peoples have a right to determine their own destinies—contained in the UN Charter. Equally importantly, it entailed a concrete demonstration of the failure of colonizers to fulfill their self-proclaimed mission as elaborated in the discourse of Europe’s “civilizing mission.” Ultimately, the argument was not simply that complete independence was a better option than colonization. Rather, it was the only option and route forward to a future characterized by human rights and development.

The production of competing discourses was geared towards control of the passage of resolutions. The discursive dimension provides a window into the world of international norms, historical narratives, and contestations over their import. The voting dimension affords a look into how international politics played out in the space of the UNGA. Allies of the Algerian independence movement struggled for years, in the face of acute resistance by France and its allies, to gain international affirmation of Algeria’s right of independence. In highlighting their eventual success in 1960, the aim of this article has not been to make trite claims about the agency of non-Western people. Indeed, formulations of the non-West such as “the darker nations”, “colonized people”, “Third World” and “Global South” do not connote unified historical actors as much as they do ideas and sentiments of a political and ethical import. Rather, it has been to demonstrate the rhetorical power of the partisans of the anticolonial internationalist discourse who eventually prevailed at the UNGA.

Finally, decolonization struggles entailed a fundamental re-articulation of existing notions of the state and international society. Legitimate political sovereignty, according to the anticolonial internationalist discourse, could only obtain when the state was singly oriented towards its citizens, which composed a national body. It was precisely the condition of nationality that was not met by the colonial state in Algeria, which remained riven by a colonial economy that differentiated between rights-bearing European settlers (and their descendants) and a marginalized indigenous population. The anticolonial internationalist discourse mounted a further challenge to the still-existing structure of international society comprised of both imperial and postcolonial national states. This structure precluded a consensus on sovereign statehood by challenging the cardinal principle of national self-determination enshrined in the UN Charter. The struggle for Algerian independence at the UN was thus equally a struggle for the construction of a new international order composed of states formed on the basis of the principle of national self-determination and oriented towards the development of their citizens. This struggle would be followed by other colonial questions at the UNGA: apartheid in South Africa, the end of Portuguese colonialism, the independence of Namibia, and the question of Palestine, among others. It is precisely this struggle, which entailed a continuous engagement with, and refutation of, the metrocentric civilizational discourse that remains undertheorized in existing accounts of decolonization struggles at the UN.