I. Introduction

Ethical approaches to artificial intelligence (AI) in general and the concept of trustworthy AI in particular have been in vogue in recent discussions on the social challenges posed by new technologies. The notion of trustworthy AI has been endorsed by the European Union’s (EU) institutions in their discourse and legislative practices. Nevertheless, little attention has been paid to the realisations of these values by the very same institutions in their use of technological solutions to tackle social problems.

In its communication of 8 April 2019, the European Commission declares that the European approach to AI should contribute to build confidence in AI: “[T]rust is a prerequisite to ensure a human-centric approach to AI: AI is … a tool that has to serve people with the ultimate aim of increasing human well-being”.Footnote 1 This Communication is part of the broader EU strategy for AI,Footnote 2 according to which Europe has to champion an approach that places people at the centre of technological progress, which should benefit the whole society. Drawing on the recommendations of the High-Level Expert Group on AI (HLGAI),Footnote 3 the Commission details several key requirements that constitute “human-centric AI”: human agency and oversight; technical robustness and safety; privacy and data governance; transparency, diversity, non-discrimination and fairness; societal and environmental well-being; and accountability. In the White Paper on AI,Footnote 4 the Commission calls for an “ecosystem of trust”, noting that although AI applications are already subject to EU legislation (on fundamental rights, consumer protection, etc.), “some specific features of AI (e.g. opacity) can make the application and enforcement of this legislation more difficult”.Footnote 5 The Commission’s proposal for a legal framework on AI in April 2021 marks a significant step in the European AI strategy.Footnote 6 The proposal follows a risk-based approach in which the level of regulation depends on the level of risk posed by AI systems.Footnote 7 Through this proposal, the EU confirms its desire to distinguish itself from other international powers such as the USA and China by becoming “a global leader in the promotion of trustworthy AI” and spearheading “the development of new ambitious global norms”.Footnote 8

Interestingly, in parallel with its efforts to create an ecosystem of trust and to develop a human-centric approach to AI, the EU has also shown interest in the use of digital technologies and AI applications in the implementation of its own policies in the field of migration policy and external border control.Footnote 9 Indeed, since the 1990s, the EU has been building a vast digital infrastructure that includes various information systems and databases with the aim of expanding the surveillance and control of the movement of third-country nationals. In the last decade, the trend towards the “digitisation of control”Footnote 10 has been clearly confirmed, notably in the Communication “Smart Borders – Options and the Way Ahead”, in which digital technologies are presented as essential to ensuring “swift and secure border crossings”.Footnote 11

Among the latest major developments in the field is the adoption by the European Parliament and the Council of the Regulation 2018/1240 establishing a European Travel Information and Authorisation System (ETIAS)Footnote 12 – an information technology (IT) system that will provide travel authorisation to visa-exempt foreigners.Footnote 13 ETIAS imposes a new condition of entry on non-EU citizens who are currently able to enter European territory without any prior authorisation. When ETIAS becomes operational (which is planned for May 2023),Footnote 14 every visa-exempt traveller will be compelled to hold an authorisation,Footnote 15 delivered on the basis of an assessment of the presumed security, illegal immigration and/or high epidemic risks. This risk assessment will notably be performed by a profiling algorithm, called “screening rules” in the Regulation’s nomenclature. The establishment of these screening rules is a major milestone in the history of the management of external borders and the use of digital technologies, as it constitutes the first European automated risk-profiling system that will be used in migration management.Footnote 16

Taking ETIAS as a case study permits us to examine the human-centric AI narrative in light of the EU’s own use of AI to pursue its own purposes. The highly moral discourse that characterises EU institutions’ communications and legislative acts on the matter becomes more precise when confronted with a concrete example of how the promoted values are realised “on the ground”. ETIAS seems to be a well-suited object of study, since it will be one of the biggest automated information systems using profiling techniques developed by the EU with far-reaching consequences for foreign travellers, who are nonetheless not required to possess a visa to cross the EU’s external borders.

Despite what precedes, it should be stressed that it is an open question as to whether ETIAS’s screening rules and their underlying profiling algorithm will be effectively based on AI. The proposed Regulation only provides for a framework without explaining in detail how the algorithm will be established. The newly adopted delegated decision by the EU Commission does not give much information about the algorithmic process,Footnote 17 and it cannot be taken for granted that machine learning algorithms – with which AI is often associated – will be implemented. Because it is not clear that AI will be used in ETIAS, one might ask whether it is a well-suited case study for assessing the EU’s narrative on AI in light of its actions. Still, we contend it is suitable for at least two reasons.

Firstly, as we will address later in our analysis, there is evidence from the EU itself that machine learning techniques may be used in ETIAS, either at launch or later, once it is implemented. Secondly, the very notion of AI,Footnote 18 which is so fashionable today (including within EU institutions), is often used in a vague and imprecise way. Indeed, legal and political approaches to AI do not operate under exactly the same meaning of AI compared with what computer engineers and data scientists encompass under the umbrella of “artificial intelligence”. In this regard, some experts argue that the definition of AI set out by the EU Commission in Annex I of the proposed Regulation on AI is so broad that any computer program could qualify as an AI system under its provisions.Footnote 19 Interestingly, Article 83 of this proposal excludes AI systems that are components of large-scale IT systems in the Area of Freedom, Security and Justice – the list of which includes ETIAS – from its scope.Footnote 20 This demonstrates that the Commission itself assumes that ETIAS is likely to constitute an AI system within the meaning of the proposed Regulation on AI; otherwise, there would be no need for an exception rule. Thus, regardless of the exact functioning of the screening rules, we argue that ETIAS is undeniably part of the EU’s narrative on AI.

This paper is divided into two main parts. In the first (Section II), we briefly depict the digitalisation of the EU’s external borders with an overview of the six large-scale information systems that have been set up by EU institutions as significant tools for their migration policy and border management. We then turn to our case study by briefly developing the historical context that gave rise to ETIAS. We explain the decision and operational processes of ETIAS that specifically aim at enhancing surveillance at external borders. In the second part (Section III), we focus on the profiling algorithm that is set forth in Article 33 of ETIAS Regulation. Based on the information available to date, we show how the algorithm would work once operational. Promoted as a tool of rationalisation and optimisation of border control, ETIAS may well on the contrary produce arbitrary and groundless results, as we intend to show by drawing on the seminal paper of Barocas and Selbst.Footnote 21 We argue that ETIAS is an instrument of differential exclusion, playing a key role in European border management.

By way of conclusion (Section IV), we tackle the ambiguities that lie behind the often supposedly naïve European discourse on AI. Indeed, we show that the risk-based approach (applied to the “undesirable” foreign population) constitutes a prerequisite of the “ecosystem of trust” (promoted among European citizens).

II. A new piece in the jigsaw of the EU’s large-scale information systems

1. The digitalisation of the EU’s external borders

The digitalisation of the EU’s external borders can be traced back to the achievement of the EU’s Area of Freedom, Security and Justice. The resulting lifting of internal border controls and subsequent loss of Member States’ sovereignty over their own borders were compensated for by increased cooperation at the external borders, particularly in the fight against illegal immigration.Footnote 22 This development reached new heights following 9/11 and the terrorist attacks perpetrated in Madrid in 2004 and in London in 2005. Migration policies became the main lever of/in the “war on terror”, shedding light on an “intertwining between immigration and security” or a “migration-risk nexus”.Footnote 23 Borders have become a privileged site for public investment in arms and high-tech industries. Drones, thermal and facial recognition cameras and biometric identification tools have been tested and deployed primarily on migrant populations, as well as a number of other technologies aiming at automating the treatment of visa, asylum or residence permit applications.Footnote 24 The technological change has been accompanied by a conceptual one: human mobility has been represented in terms of manageable and dynamic flows (motilitiesFootnote 25) and captured through novel technologies and digitalisation that allow a wide range of non-EU citizens’ data to be collected and stored in large-scale databases with multiple purposes.

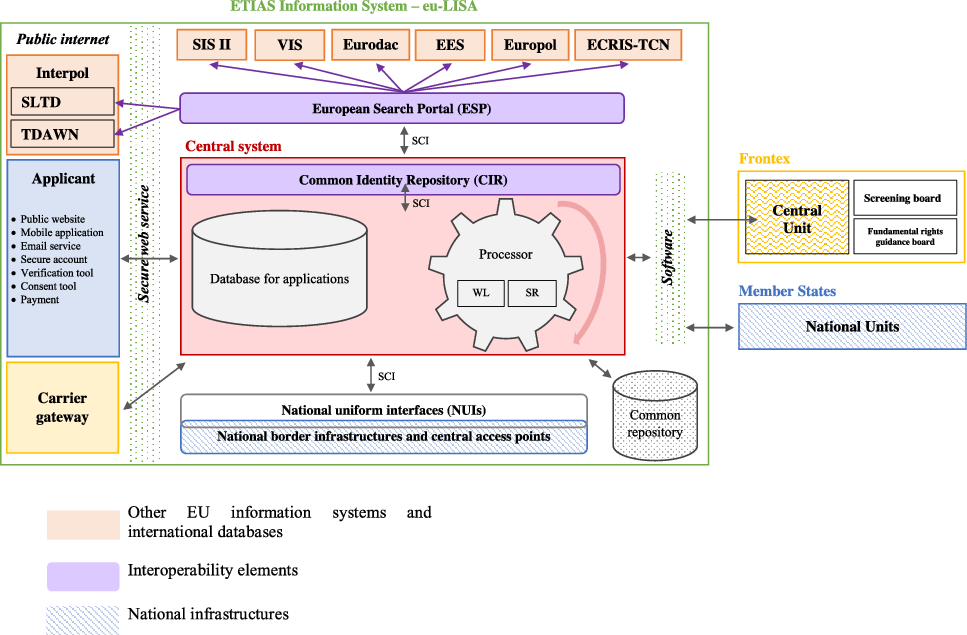

To date, there are six EU databases on third-country nationals in the EU (see Figure 1). Three of them are operational: the Schengen Information System (SIS II), which enables national authorities to have access to alerts on persons and property during border controls;Footnote 26 Eurodac, established in the framework of the Dublin system,Footnote 27 which registers asylum seekers’ and undocumented people’s fingerprints with the aim of their identification, as well as the determination of the Member State responsible for examining an asylum application;Footnote 28 and the Visa Information System (VIS), which collects all data relating to any application for a short-stay visa, a long-stay visa and a residence permit in order to implement the common visa policy.Footnote 29 In the wake of the so-called “migration crisis” of 2015 and the terrorist attacks in Paris in 2015 and Brussels in 2016, three other large-scale EU information systems (which are not yet functional) have been created: the Entry/Exit System (EES), which will record a range of data of any foreigner crossing the EU’s external borders for the purpose of a short stay (no more than ninety days) and pursue more than a dozen objectives;Footnote 30 ETIAS, which will be studied in detail in what follows; and the European Criminal Records Information System for Third-Country Nationals (ECRIS-TCN), which collects information on the criminal records of non-European citizens.Footnote 31

Figure 1. Overview of the European Union (EU) information systems (our illustration). BMS = biometric matching service; CIR = common identity repository; ECRIS-TCN = European Criminal Records Information System for Third-Country Nationals; EES = Entry/Exit System; ESP = European search portal; ETIAS = European Travel Information and Authorisation System; IT = information technology; MID = multiple-identity detector; SIS II = Schengen Information System; VIS = Visa Information System.

This patchwork of six successively created databases considerably diverges from the initial intent of the EU Parliament, which planned to create a single EU information system in the 1990s.Footnote 32 Indeed, the Commission itself has described the resulting compartmentalisation as an obstruction.Footnote 33 To override what was perceived as a weakness, the new concept of interoperability has made its way from computer science to the politics of European data management. Standardised in an International Organization for Standardization (ISO) norm,Footnote 34 interoperability refers to the ability of several functional units – such as information systems – to share and exchange data. Two regulations implementing interoperability were enacted at the EU level. The first one deals with borders and visas, whereas the second one is concerned with police and judicial cooperation, asylum and immigration.Footnote 35 Their common objectives cover the common visa and asylum policies, the fight against illegal immigration and the management of security and public order. According to these two regulations,Footnote 36 interoperability takes the form of four components: the European search portal (ESP),Footnote 37 the shared biometric matching service (BMS),Footnote 38 the multiple-identity detector (MID)Footnote 39 and the common identity repository (CIR). The CIR will be the core of the EU digital infrastructure in the future as it will contain a personal record of every single data subject registered in the EES, VIS, ETIAS, Eurodac and/or ECRIS-TCN.Footnote 40 Moreover, it is worth noting that a central repository for reporting and statistics (CRRS) is established “for the purposes of supporting the objectives of the EES, VIS, ETIAS and SIS … and to provide cross-system statistical data and analytical reporting for policy, operational and data quality purposes”.Footnote 41

The progressive development of the various databases detailed here, from the first SIS to the latest techno-legal interoperability devices, is marked by the same trend of expansion. The primary purpose of a database is to ease the application of a specific legal mechanism, such as the “Schengen acquis” for the SIS II or the identification of the Member State responsible for examining an asylum application for Eurodac. Then, new objectives are added to the initial one(s), notably the fight against irregular immigration or law enforcement. As a result, the categories of personal data collected and processed are extended, thus encompassing biometric data in particular. Finally, with interoperability, the collection and processing of personal data serve yet other purposes, which were not initially included in the respective legal instruments, such as to facilitate the identification of unknown persons.Footnote 42

As Niovi Vavoula rightly notes, the raison d’être of this expansion mirrors the paradigm of filling in “information gaps” and can be qualified as “data greediness”.Footnote 43 The current landscape of information systems effectively covers all groups of third-country nationals, providing various types of data on their status and mobility. The Foucauldian metaphor of the panopticon has often been mobilised to account for this “emerging know-it-all surveillance system, whereby authorities would be able to achieve total awareness of the identities of the individuals”.Footnote 44 The recourse to Foucauldian theory is surely grounded in the analysis of devices of migration control. Nevertheless, ETIAS may not be reduced to just another window in the tower of the prison officer or a simple tool of mass surveillance. It also speaks to a recent paradigm shift from migration control (reactive, focusing on concrete individuals) to migration management (proactive, focusing on potential migrant populations). In this sense, ETIAS is plainly part of the theoretical framework developed in Foucault’s Discipline and Punish and Security, Territory, Population. Both of these roles – a tool of mass surveillance of foreigners and an instrument of an individualised population management – will be explored in the pages that follow.

2. ETIAS: background and constitutive elements

Developing an automated European travel authorisation for visa-exempt third-country nationals was first considered in 2008 when the Commission launched a study on establishing an Electronic System of Travel Authorisation, called “EU-ESTA” in reference to its US counterpart.Footnote 45 This project gave rise to divergent opinions. On the one hand, the European Parliament, following the lead of the European Data Protection Supervisor,Footnote 46 questioned the necessity and proportionality of such a system and criticised the underlying assumption that “all travellers are potentially suspect and have to prove their good faith”.Footnote 47 On the other hand, other EU institutions unequivocally favoured preventative and anticipatory actions based on the use of new technologies and the massive collection of data for risk assessment.Footnote 48 A security narrative (“intelligence-led policies”Footnote 49) was used to ground the need for information. In 2011, the auditing firm PricewaterhouseCoopers (PwC), commissioned to study the feasibility of EU-ESTA, concluded that the development of such a system “would not … be responding to fully unambiguous, well-identified and fully understood needs and problems at this stage”.Footnote 50 Eventually, the Commission gave up on the project on the grounds that the “potential contribution [of an EU-ESTA] to enhancing the security of the Member States would neither justify the collection of personal data at such a scale nor the financial cost and the impact on international relations”.Footnote 51

However, it took less than five years for the EU executive to put a draft travel authorisation for visa-exempt foreigner travellers back on the table. In a 2016 Communication, the Commission asserted the need to strengthen external border controls, citing (the migratory consequences of) the Syrian conflict and the threat to internal security arising from the terrorist attacks in Paris in 2015 and Brussels in 2016.Footnote 52 The Commission argued that there were “shortcomings” in EU information systems, notably “gaps in the EU’s architecture of data management”.Footnote 53 This, coupled with the visa liberalisation policy, is “particularly relevant” for the monitoring of external (land)Footnote 54 borders.Footnote 55 This time, the European Parliament warmly welcomed the Commission’s initiative and invited it to propose a text.Footnote 56

On 16 November 2016, the Commission tabled a proposal for a Regulation establishing ETIAS.Footnote 57 The reading of the proposal raises at least two major concerns. Firstly, although the Commission stated that it was aware of the major impact ETIAS is likely to have on human rights, no ex ante assessment (neither in general nor with regard to human rights in particular) was carried out by its services. There was a feasibility study conducted by PwC between June 2016 and October 2016,Footnote 58 but contrary to what the Commission claimed in the proposal, it focused exclusively on the feasibility of establishing ETIAS. This ignores the terms of the 2016 Interinstitutional Agreement on Better Law-Making, which obliges the Commission to carry out an impact assessment where its initiatives, such as the one at stake here, are likely to have a significant economic, environmental or social impact.Footnote 59 Secondly, the very fact that the feasibility study was again entrusted to PwC – the same company that was charged with the study on EU-ESTA five years earlier – raises some questions. The ubiquity of PwCFootnote 60 in the field of external border and migration management reveals a worrying privatisation of policies that should remain under the public sector’s roof, especially in situations where people’s lives and rights are at stake. It is reaching its paroxysm here, as the Commission seems to have drawn directly from PwC’s study as regards ETIAS’s operational process and IT architecture.Footnote 61

Although raised in the European Parliament’s Committee on Civil Liberties, Justice and Home Affairs (LIBE Committee),Footnote 62 to which the legislative proposal was submitted for discussion and vote, these concerns were not followed up and the Regulation was adopted by the co-legislators in the summer of 2018.Footnote 63 Hence, serious shortcomings can be identified in the democratic process, in which “building trust” does not seem to have been of concern.

a. ETIAS’s general architecture

The contextual overview shows that ETIAS and its legal framework are a full product of the long-lasting but still ongoing digitalisation of external borders detailed above. ETIAS’s primary objective is to determine whether the short stay of these foreigners on Member States’ territory “would pose a security, illegal immigration risk or a high epidemic risk”.Footnote 64 But there is more: ETIAS also aims at making the prevention, detection and investigation of terrorist offences or of other serious criminal offences more effective.Footnote 65 These are indisputable examples of the migration–security nexus already identified.

ETIAS consists of a large-scale information system (managed by the European Agency for the Operational Management of Large-Scale IT Systems in the Area of Freedom, Security and Justice – eu-LISA), a Central Unit (created within the European Border and Coast Guard Agency – Frontex) and National Units (which Member States have to set up).Footnote 66 The information system (Figure 2) provides the technical infrastructure that supports ETIAS,Footnote 67 while the units – both Central and National – are responsible for the manual processing of applications submitted by travellers.Footnote 68 This multiplication of stakeholders entails a fragmentation of responsibilities between EU agencies and Member States. Therefore, accountability, which is fundamental in the AI trust-building process, could well be undermined.

Figure 2. Overview of the European Travel Information and Authorisation System (ETIAS) information system (our illustration). ECRIS-TCN = European Criminal Records Information System for Third-Country Nationals; EES = Entry/Exit System; EU = European Union; eu-LISA = European Agency for the Operational Management of Large-Scale IT Systems in the Area of Freedom, Security and Justice; SCI = secure communication infrastructure (fourth-generation Trans European Services for Telematics between Administrations – TESTA-ng); SIS II = Schengen Information System; SLTD = Interpol Stolen and Lost Travel Document database; SR = ETIAS screening rules; TDAWN = Interpol Travel Documents Associated with Notices database; VIS = Visa Information System; WL = ETIAS watchlist.

b. ETIAS’s decision process

ETIAS Regulation stipulates that every visa-exempt third-country national who wishes to enter a Member State’s territory must complete an online form containing more than twenty personal data fields,Footnote 69 such as common identity data (including nicknames and nationality), contact details (including domicile or place of residence), travel documents, place of birth and parental first name(s), level of educationFootnote 70 and current profession.Footnote 71 The applicant is also required to answer three specific questions relating to any previous criminal convictions, stays in a war or conflict zone and orders to leave the territory of a Member StateFootnote 72 or return decisions to which they could have been subject. Once the application is introduced and declared admissible, the information system automatically creates an application file and records and stores the IP address from which the application form is submitted.Footnote 73 These data are kept for the period of validity of the travel authorisation (which is in principle set at three years) or during five years from the last decision of refusing, cancelling or revoking the authorisation.Footnote 74

ETIAS then examines the application, based on automated and individual processing, to determine whether there is a positive answer (“hit”) or, to put it differently, whether non-EU citizens pose a risk.Footnote 75 If the assessment processing does not result in a hit, the travel authorisation is automatically issued to the applicant.Footnote 76 If, on the contrary, there is a hit, the application is first examined by the Central Unit, which is responsible for checking whether the personal data in the application file correspond to the data that triggered the hit: the aim is to remove the “false positives” caused by data errors.Footnote 77 If the identity of the applicant is confirmed or doubts remain, the application is sent to the National Unit of the Member State responsible for manual processing,Footnote 78 which is responsible for issuing the travel authorisation.Footnote 79 Where the national authority refuses, the applicant has the right to appeal “in the Member State that has taken the decision on the application and in accordance with the national law of that Member State”.Footnote 80 Nevertheless, the effectiveness of this right seems to be undermined by the lack of a detailed motivation for the decisionFootnote 81 and practical obstacles to accessing European judicial bodies from abroad.

For the sake of completeness, it should be noted that carriers (air, sea or coachFootnote 82; before boarding) as well as border authoritiesFootnote 83 (at the border crossing point) consult the ETIAS information system to verify whether foreign travellers are in possession of a valid travel authorisation, since it is a new condition of entry into EU territory.Footnote 84

c. ETIAS’s operational process

What remains to be described is the operational process of the ETIAS information system or, in other words, the operations it entails when it examines an application. These operations are of three kinds.

Through the first operation, ETIAS launches “a query by using the ESP to compare” the applicant’s data with those “contained in a record, file or alert recorded in an application file stored in the ETIAS central system, SIS, the EES, the VIS, Eurodac, ECRIS-TCN, Europol data and in the Interpol SLTD [Stolen and Lost Travel Document] and TDAWN [Travel Documents Associated with Notices] databases”.Footnote 85 In other words, ETIAS automatically checks whether, for example, a person has been denied entry under the EES or is subject to an SIS alert, in which case there is a match. If the identity of the applicant is confirmed by the Central Unit, the National Unit makes a sovereign assessment of the security and/or illegal immigration risk(s) that the applicant could pose and issues or refuses the travel authorisation accordingly.Footnote 86

Through the second operation, ETIAS “compares” the applicant’s data with the ETIAS watchlist,Footnote 87 which “shall consist of data [entered by Europol or the Member States] related to persons who are suspected of having committed or taken part in a terrorist offence or other serious criminal offence or persons regarding whom there are factual indications or reasonable grounds, based on an overall assessment of the person, to believe that they will commit a terrorist offence or other serious criminal offence”.Footnote 88 This list, for which the framework has not yet been adopted,Footnote 89 is based on a logic of pre-emption, whereby persons who are only suspected of committing an offence in the future will potentially be denied authorisation to cross external borders. If the applicant’s data are included in the watchlist and their identity is confirmed by the Central Unit, the National Unit makes a sovereign assessment of the security risk(s) posed by the applicant and issues or refuses the travel authorisation accordingly.Footnote 90

Last but not least, the third operation has the purpose of assessing the risks posed by the applicant in the light of “screening rules”Footnote 91 (ie a profiling algorithm laid down in Article 33 of ETIAS Regulation). If the applicant’s data match “specific risk indicators” and their identity is confirmed by the Central Unit, the National Unit makes a sovereign assessment of the applicant’s security, illegal immigration and/or high epidemic risk(s) and, accordingly, issues or refuses the travel authorisation. Significantly, the National Unit is required to conduct an individual assessment and “in no circumstances” can make an “automatic” decision solely on “the basis of a hit based on specific risk indicators”.Footnote 92 However, it is doubtful that this obligation of autonomous human assessment will be satisfied in practice, considering the well-documented automation bias.Footnote 93

The first operation is past-orientated, since it seeks to cross-check someone’s data with the pre-existing information stored in other databases.Footnote 94 The second operation is hybrid: it works in the same way, except that the watchlist, as we have said, will also be composed of information about persons who are merely deemed likely to commit a serious criminal offence in the future. The third operation is fully future-orientated, since the screening rules aim at singling out “persons who are unknown” but “assumed of interest for irregular, security or public health purposes due to the fact they display particular category traits”.Footnote 95 This process of profiling is examined in the next section.

III. The algorithmic profiling system set up by ETIAS

1. The profiling algorithm introduced by Article 33 of ETIAS Regulation

a. How does profiling work?

Schematically, profiling refers to making a prediction about a hidden variable of interest (also called a target variable) on the basis of one or more characteristics of a group of subjects (human or otherwise) that are highly correlated with this variable. Frederick F. Schauer proposes a comprehensive example. Consider a rule prohibiting certain breeds of dogs such as pit bulls from entering parks for security reasons. This constitutes a form of profiling, where the hidden variable of interest is the dog’s dangerousness and the correlated criterion is the breed.Footnote 96 Such a rule is justified by the fact that a pit bull is statistically more likely to behave dangerously compared to other dog breeds. This measure, based on generalisation, therefore aims to reduce the risk of accidents in parks (even though many pit bulls are harmless). Profiling is thus a rudimentary technique present in our everyday lives. Regardless of the technologies used, its essence lies in the detection of correlations and patterns: a dog, simply because one of their physiological traits is correlated with dangerousness, will be denied access to parks, even though nothing is known of their past individual behaviour.

While profiling is a long-standing practice, it has been the subject of much scrutiny for several years, mainly due to the latest developments in the IT sector. On the one hand, the growing influence of digital technology – notably through the Internet of Things and the multiplication of sensors in both private and public spaces – has led to the production of an unprecedented amount and diversity of data. On the other hand, this myriad of data produced daily has been successfully processed and analysed thanks to the considerable progress made in computer storage and computing capacities. The development of data mining and machine learning techniques has thus given rise to new forms of profiling: digital footprints and online behaviour (eg on social networks), public transport journeys or credit card purchases are all pieces of information that allow algorithms to make inferences about our future behaviour.Footnote 97 Whereas, for instance, traditional credit scoring models take salary and household composition as the main relevant variables, alternative forms of credit scoring now consider data such as one’s network of friends on Facebook or the time spent reading terms and conditions.Footnote 98 These “profiles 2.0” are very far from the “dangerous dog” profile described above, but the principle remains of making predictions based on variables that are supposed to be statistically good indicators of the information sought.

Alongside marketing, which is the field par excellence in which data mining techniques were experimented with, the field of security was also one of the first to be affected, particularly in the aftermath of 9/11.Footnote 99 It fostered the emergence of a pre-emptive rationality illustrating “the efforts of the policymakers to capture the future and fold it back into the present” to render it “actionable”.Footnote 100 This has been done by developing risk analysis tools to assess a probable, yet unknown, threat that a human could pose.

b. Trends of profiling at the EU level

As for the EU, digital technologies play a major role, as we have seen, in the management of external borders. However, although EU databases and information systems have contributed to the development of a massive infrastructure of surveillance, they have had little recourse to predictive and profiling methods so far. A first step has been achieved in that direction with the establishment of SIS II mentioned earlier. Whereas the first version of SIS (SIS I) was merely an alert system operating through the collection of information, its latest version (SIS II) makes it possible to assess the risk of a person on the basis of not only the data that are directly related to that person, but also links that would connect them to someone (or something) else listed in the system.Footnote 101 A second step was initiated with the Passenger Name Record (PNR) Directive, adopted on 27 April 2016, which introduced the collection of passengers’ data to prevent and detect serious crime and terrorism. This Directive requires each Member State to set up “Passenger Information Units” responsible for processing and analysing this data, which involves profiling techniques.Footnote 102

However, there are several reasons to argue that ETIAS is not a mere additional step of the trend initiated by the two systems we have just described. Firstly, ETIAS is the first European information system to use profiling for extremely broad objectives, far from being limited to the field of terrorism. This ambition appears unprecedented. Secondly, the profiling system will be managed by the EU, with Member States playing only a secondary role. By contrast, in the PNR Directive, Member States are responsible for the collection and processing of PNR data. As for SIS II, it is an EU database that takes the form of an investigation tool allowing for interlinking different alerts, but it does not use algorithmic profiling. Thirdly, ETIAS’s profiling system will be a compulsory step for all visa-exempt third-country nationals. This does not mean that the risk represented by individual visa-exempt travellers has not been assessed so far. Border guards have already had the power to deny access to foreigners at external borders – a prerogative that they will keep after ETIAS’s implementation, as we have already explained. What is new here is the implementation of a systematic and generalised digital procedure: all visa-exempt foreigners will necessarily be assessed against the screening rules (ie profiled).

c. How does ETIAS’s profiling algorithm work?

At this stage, as mentioned in Section I, the exact content of the screening rules is not yet known. The only official document available is the Regulation. Article 33 contains the main elements, which will serve as the basis for the following analysis. This provision specifies that the screening rules shall take the form of an algorithm enabling profiling as defined in point 4 of Article 4 of the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR).Footnote 103 The algorithm will determine whether data collected from the applicant matches “specific risk indicators … pointing to security, illegal immigration or high epidemic risks”. ETIAS Regulation does not precisely define the nature of the algorithm, and its terminology is (to say the least) vague, referring alternately to “risks”, “specific risks” and “specific risk indicators”. The Commission has recently adopted a delegated decision to further define what is referred to as the “risks” (ETIAS Regulation, Article 33(2))Footnote 104 and has yet to adopt an implementing act to determine the “specific risks” (ETIAS Regulation, Article 33(3)).

This is why, in order to better understand how the screening rules will work and what kinds of algorithmic techniques will be used, we contacted several relevant EU institutions and agencies. First, eu-LISA, which is responsible for ETIAS’s technical infrastructure,Footnote 105 denied access to information because “ETIAS is currently under design and development, and it is not in operation. Therefore, the disclosure of the requested information could have a substantial impact on the decision-making process of the Agency since with access to such information the public can create an unnecessary pressure on the ongoing process and jeopardize the design and development of the system”.Footnote 106 Then, the Commission offered some insights but replied that it would be more appropriate to ask Frontex since, pursuant to Article 75(1)(c) of ETIAS Regulation, this Agency is responsible for the screening rules.Footnote 107 Finally, the latter answered that, as regards the screening rules, “[i]t is probably more appropriate to talk about filtering queries than complex algorythms [sic]. … no sophisticated analysis methods … and no machine learning, or any other form of AI is involved”.Footnote 108

Despite these statements, there are various indications that machine learning techniques (classification or clustering algorithms) could be used, either at launch or at a later stage. In its 2020 report “Artificial Intelligence in the Operational Management of Large-Scale IT Systems”, eu-LISA considers, for instance, that “an additional level of automation or analytics based on AI or machine learning could be introduced” to assist national authorities in dealing with applications that have triggered a hit.Footnote 109 In the same vein, the report “Opportunities and Challenges for the Use of Artificial Intelligence in Border Control, Migration and Security”, written by Deloitte for the Commission,Footnote 110 states in relation to ETIAS’s screening rules that “AI could support in selecting these indicators and possibly adapting them over time/depending on the applicant”. The report further adds: “Based on this risk level, applications can be classified for individual review (‘triaging’) by an appropriate case worker. Additionally, a suggested decision (e.g. similar cases resulted in the following outcome) could be provided by the AI model based on historical data (and thus similar applications). This would not only ensure a fair assessment, but also improve consistency across Member States”.

Both these reports, which perfectly illustrate the current trend towards the growing mobilisation of AI for migration management, make us think that Frontex’s response should not be taken too literally. This seems all the more true when one considers that tens of millions of applications will be processed each year by ETIAS.Footnote 111 Furthermore, given the puzzling history of EU information systems in the Area of Freedom, Security and Justice, it cannot be excluded that the items of information required to shape the screening rules will be completed by data coming from other EU or international databases and/or new categories of data. Last but not least, as will be seen below, the Commission insists on the need to collect data on a quasi-continuous basis in order to constantly identify the specific groups of travellers who pose a risk. This demonstrates the willingness to follow the continuous evolution of risks and to use the most recent data to feed the risk profiles so that they stick as closely as possible to the ever-changing reality. This goal of making models evolve in response to new data as quickly as possible can be more accurately achieved using machine learning algorithms than by humans.

Thus, despite the indeterminacy resulting from the lack of transparency in the algorithmic design by the European institutions, we may formulate several strong assumptions on the functioning of the screening rules based on the reading of Article 33.Footnote 112 Rather than talking about a single algorithm, it seems more appropriate to describe the screening rules as forming a complex algorithmic decision-making system that will be composed of various algorithms, including expert-system algorithms and presumably machine learning techniques.Footnote 113 Two aspects should be distinguished: on the one hand, the rules themselves, which will determine whether a given applicant poses a risk by comparing their data with the “specific risk indicators” (ie risk profiles thus triggering a hit); and on the other hand, the way in which these profiles of risk will be defined and the data that will be taken into account for doing so. The latter will be established by the ETIAS Central Unit (which is part of Frontex) on the basis of one or more of the following items of information: (1) age range, sex and nationality; (2) country and city of residence; (3) level of education (primary, secondary or higher education or none); and/or (4) current occupation (multiple-choice answer).

But how and on what basis will the risk profiles be defined? What will justify some combinations of attributes being considered risky and others not? Article 33(2) and the Delegated Decision that further defines the risks list three sources of information that will be taken into account: (1) data provided by the World Health Organization (WHO) and the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC); (2) data transmitted by Member States; and (3) statistics produced by EES and ETIAS itself.

Firstly, the data transmitted by the WHO and the ECDC will help to identify high epidemic risks. Frontex, in its answer, stated that “the ETIAS Central Unit will monitor the Outbreak Disease Notices published by WHO. Frontex will also cooperate closely with the ECDC to have an accurate and up to date situational awareness on the diseases that might represent a high epidemic risk relevant for ETIAS”.Footnote 114 In practical terms, if the WHO declares that an outbreak of a certain disease has occurred in a given region of the world, the ETIAS Central Unit could modify the screening rules so that a hit would be triggered for anyone (or certain categories of people) travelling from that region. While the ETIAS Regulation was adopted before the COVID-19 pandemic, it is not difficult today to gauge the significance of such a provision.

Secondly, Member States will provide information that relates to data on “abnormal” rates of overstaying and refusals of entry, “specific” security risks and high epidemic risks. The scope is thus extremely broad. Articles 4 and 5 of the Delegated Decision state, in terms of security risks and abnormal rates of overstaying and refusals of entry, that “Member States shall review their analysis at least every 6 months or where new information emerges that makes it necessary to modify the analysis”.Footnote 115 They must describe the risks identified and provide evidence and known facts related to it and the sets of characteristics of specific groups of travellers associated with the security or immigration risk. As each Member State will be a producer of knowledge in this respect, harmonisation is needed so that these data can be compared. Without this, any data analysis is impossible.

In their answer, Frontex told us that “Member States will transmit their periodic reports to Frontex via the regular channels established for risk analysis purposes”.Footnote 116 Indeed, Member States have already been required to provide Frontex with a certain amount of data on a regular basis, in accordance with the “Common Integrated Analysis Model” (CIRAM), through which Frontex monitors the situation at the borders and assesses the capacity of each Member State to deal with migration flows.Footnote 117 Scholars have shown that risk analysis was one of the most important, if not the most important, tasks of Frontex: the results of risk analyses allow for the comparison of Members States’ capacity to manage their borders and serve as a basis for key decisions such as the allocation of financial support to Member States.Footnote 118 The implementation of ETIAS will therefore increase the data reporting obligations of Member States and incidentally the influence that Frontex has acquired in the field of migration management. More broadly, Frontex’s risk analysis and ETIAS should be seen as part of the same approach towards migration: this phenomenon is seen as a threat that needs to be managed in a rational way (via risk assessment) through the collection and processing of large amounts of data.

Last but not least, there are the reports and statistical data produced by EES and ETIAS. Importantly, these data will only be collected once the two information systems are operational. This means that at the start of ETIAS’s functioning the screening rules will only be shaped by the data given by the Member States, the WHO and the ECDC. The (statistical) data provided by EES and ETIAS is biographical and related to travel information. Pursuant to Article 84(2) of ETIAS Regulation, the information is stored in an interoperability component, the CRRS.Footnote 119 For EES, this specifically covers “abnormal” rates of overstaying and refusals of entry into the EU. For ETIAS, this constitutes statistics pointing to “abnormal” rates of refusals of travel authorisations. Statistics produced by EES and ETIAS shall also be combined to find correlations between information collected through ETIAS’s application form and abnormal rates of overstaying or refusals of entry.Footnote 120 In other words, the aim is to detect profiles of “irregular” migrants, such as by analysing, among the travellers who will appear in EES statistics as overstayers, whether specific groups of travellers sharing common sets of characteristics can be identified.Footnote 121

These specific groups of travellers are anything but static: the Delegated Decision explicitly mentions that the data used to determine the risk profiles must be collected “in a manner that makes it possible to continuously identify sets of characteristics of specific groups of travellers” who exhibit a so-called illegal immigration risk.Footnote 122 In this sense, the Commission, in a Delegated Regulation detailing the rules on the operation of the CRRS, provides for the daily collection, by way of extraction, of anonymised data on overstays, refusals of entry and refusals of travel authorisation.Footnote 123 The Central Unit may then obtain statistical data and reports (which may be customised) “to further define the risks of overstaying, refusal of entry or refusal of travel authorisation”.

This ever-changing nature of ETIAS’s screening rules may well conflict with the notion of a “rule” itself, which supposes that clear criteria are defined. A similar critique was raised by the authors of the report to the LIBE Committee, according to whom it is doubtful that the reasons why a hit will be triggered will be intelligible and publicly accessible.Footnote 124 Talking about “screening rules” seems consequently to be misleading. This reflects more globally the problem of opacity that characterises many automated decision-making systems, as frequently noted by the Commission itselfFootnote 125: National Units will not be able to understand the risk score attributed by the algorithm and therefore will not have the means to justify their decisions. Default of interpretability entails difficulties in the motivation of the decision.

That being said, the ETIAS profiling system – as currently described in Article 33 – is not exactly what we tend to call a “black box”. Indeed, one element regularly pointed out as being characteristic of Big Data is the variety of such data (ie the fact that, for the same person, extremely numerous and diverse categories of data are taken into account). In the case of ETIAS, while a significant amount of data will be collected and processed overall (given that millions of travellers will have to go through the process every year), only a relatively limited number (ie six) of the applicants’ attributes – corresponding to well-established sociodemographic categories – will be taken into account. Furthermore, Article 33(6) of ETIAS Regulation provides that “[t]he specific risk indicators shall be defined, established, assessed ex ante, implemented, evaluated ex post, revised and deleted by the ETIAS Central Unit after consultation of the ETIAS Screening Board”.Footnote 126 The Regulation does not elucidate how this provision will be implemented, but this implies that, even if machine learning is likely to be used, the existence of a human factor in the establishment of the specific risk indicators is clearly somehow foreseen.

In any case, there is no doubt that the way in which the screening rules will be applied requires close scrutiny. Under EU law, Article 24 of the EU institutions data protection Regulation, which mirrors Article 22 GDPR, states as a general principle (subject to exceptions) that each data subject “shall have the right not to be subject to a decision based solely on automated processing, including profiling, which produces legal effects concerning him or her or similarly significantly affects him or her”. Although the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU) has not yet ruled on the interpretation of the scope of those provisions, the screening rules do not seem to fall within their scope, especially because the final decision rests with the National Units, which make a sovereign assessment of the risk(s) posed by the applicant.Footnote 127

Moreover, there are several reasons to believe that the ETIAS screening rules will not meet the safeguards set up by the CJEU in its Opinion 1/15 on the EU–Canada PNR Agreement and in its La Quadrature du Net and Others judgment (both related to the field of security and the fight against terrorism),Footnote 128 in which it ruled that the models and pre-established criteria used to conduct automatic data analysis must be specific and reliable, limited to that which is strictly necessary, not based on sensitive data in isolation and non-discriminatory.Footnote 129 Indeed, ETIAS is bound to produce unfair and/or wrong results, as we argue in the next section.

2. Non-discriminatory profiling of foreigners?

Article 14 of ETIAS Regulation states as a general principle that

[p]rocessing of personal data within the ETIAS Information System by any user shall not result in discrimination against third-country nationals on the grounds of sex, race, colour, ethnic or social origin, genetic features, language, religion or belief, political or any other opinion, membership of a national minority, property, birth, disability, age or sexual orientation. It shall fully respect human dignity and integrity and fundamental rights, including the right to respect for one’s private life and to the protection of personal data. Particular attention shall be paid to children, the elderly and persons with a disability. The best interests of the child shall be a primary consideration.Footnote 130

This provision unequivocally embodies the principle of equality and non-discrimination, which is also a core value of the “human-centric AI” promoted by the Commission and is mentioned in its 2021 proposed Regulation on AI.Footnote 131

Yet, in a report drafted during the legislative procedure of the ETIAS Regulation and submitted to the LIBE Committee, the EU Agency for Fundamental Rights (FRA) warns against the risks of discrimination that the screening rules may entail. It states that ETIAS “may in practice unduly complicate the obtaining of a travel authorisation for some persons in comparison with other applicants”.Footnote 132 Although the FRA does not question the Commission’s distinction between bona fide travellers and potential risk-bearers, it points out that the former could be put in a disadvantageous position if they are associated with a risk group, even in the absence of “individual reasons” for concluding that they embody a risk of illegal migration.Footnote 133 The FRA further cautions that combining ETIAS, EES and Member States’ data with risk profiles based on age, gender, nationality, place of residence, education and occupation could lead to “indirect discrimination”. In conclusion, it advises European legislators to postpone the enactment of the screening rules until a testing phase demonstrates that they are “necessary, proportionate and do not result in discriminatory profiling”.Footnote 134 Unsurprisingly, this advice was not followed.

But what exactly should we understand by non-discriminatory profiling? Can we take seriously the guarantees contained in Article 14 and ask for their effective implementation? This question is all the more salient in the field of migration law,Footnote 135 which is itself a form of institutionalisation of direct discrimination on the ground of nationality.Footnote 136 Non-EU citizens wanting to travel to Europe need a visa or an entry authorisation precisely because of their foreign nationality. It is therefore appropriate to start our analysis with some clarifications on the particular meaning of discrimination in the case of the algorithmic profiling of foreigners in the context of our case study.

Kasper Lippert-Rasmussen notes that the term “discrimination” has a double meaning.Footnote 137 According to the first, neutral meaning, “to discriminate” is simply to distinguish or differentiate. Discrimination in this sense is a primary task of an algorithm: in our case, it is to distinguish between categories of travellers on the basis of their characteristics. As Barocas and Selbst observe, “[b]y definition, data mining is always a form of statistical (and therefore seemingly rational) discrimination”.Footnote 138 The second, morally blameworthy sense of the term “discrimination” automatically entails a negative evaluation of the act or practice in question. Accordingly, if the effects of an algorithmic distinction in a particular political and social context contradict our sense of justice, one may be compelled to denounce discrimination in this second meaning. However, for such a claim to materialise before a court, one ought to prove a discrimination in a third, legal sense (ie a given differentiated treatment negatively affecting protected groups, pursuing an illegitimate aim and/or disproportionate).

Algorithmic profiling may well lead to adverse impacts on different groups of foreigners. This is because profiling, or the assignment of a given person to a migratory profile, can have far-reaching consequences in terms of their rights: “In an age in which rights, or in this case lack of rights, are coupled to identities through registration, a network of databases aimed at registering (potential) irregular migrants is bound to make life inside the Member States of the EU harder”.Footnote 139 Of course, this also holds for non-EU citizens who would never have the chance to find themselves “inside” the Schengen boundaries because of ETIAS and other instruments of the borders’ externalisation.

Already a superficial reading of the ETIAS Regulation allows one to conclude that the profiling based on nationality, sex, age range, country or city of residence, level of education and current occupation can hardly be neutral in regard to these grounds, which, what is more, correspond to the protected groups under anti-discrimination law.Footnote 140 Moreover, the algorithmic profiling of foreigners intervenes at several stages of the procedure, so that the potentially detrimental effect cannot be attributed to a single element of the system or a particular decision: “[A]s the European migration case illustrates, structural biases at every moment of ‘calculation’ – data gathering, organization, aggregation, algorithmic design, interpretation, prediction and visualization – serve to construct legitimized difference by reproducing existing inequalities across individuals as data subjects”.Footnote 141

In a seminal paper entitled “Big Data’s Disparate Impact”, Barocas and Selbst distinguish five ways in which Big Data can “unduly discount members of legally protected classes and put them at systematic relative disadvantage” at different stages of the design of (machine learning) algorithms: problem specification, training data, feature selection, choice of proxies and masking discriminatory intentions.Footnote 142

In the following subsections, we use Barocas and Selbst’s theoretical framework as an analytical tool to argue that ETIAS’s screening rules can pave the way to disproportionally adverse outcomes on groups of third-country nationals and may well provoke unfair and/or wrong results. Their analysis appears relevant to our case study since we have demonstrated that there is an indication that machine learning is likely to be used at some stage in ETIAS. In addition, much of their reasoning is relevant more generally for applications that resort to probabilities and statistics. Therefore, even if ETIAS’s risk profiles are not established through machine learning, our argument remains valid because these risk profiles will be inherently statistical.

Importantly, our ambition is not to demonstrate that ETIAS’s profiling algorithm is strictly discriminatory in the third, legal sense stated above.Footnote 143 Rather, we intend merely to show its encoded biases can lead to prima facie discriminatory disparities (ie instances of suspicious discriminations).Footnote 144 By relying on the principle of the shared burden of proof of EU equality law,Footnote 145 our aim is to put forward facts from which it may be presumed that discrimination is at stake, as an alleged victim of discriminatory practices, such as a non-EU citizen whose travel authorisation has been denied due to ETIAS’s screening rules, would do in courts.Footnote 146 We thus leave aside the questions of legitimate aim and proportionality that require a contextual analysis in concreto, which will not be possible as long as ETIAS’s information system is not operational. Similarly, we do not tackle the thorny question of whether there are cases of prima facie direct or indirect discriminations (or both), not only because it is a difficult exercise to perform in abstracto, but also due to the blurring of the conceptual distinction between direct discrimination and indirect discrimination in the algorithmic society.Footnote 147

a. Defining “target variable” and “class labels”: problem specification in ETIAS

The “art of data mining” consists of translating a complex social problem into a formal question about the state or value of a target variable – a process that is called “problem specification”. As we have seen, in the case of ETIAS, the target variable – or otherwise what the data minerFootnote 148 is looking for – is a security, illegal immigration or high epidemic risk, as stated in Article 33 of the Regulation. The different values that the target variable can take are called “class labels”. For our case study, these values are divided into a binary dichotomy: being a foreign traveller who poses a risk or not.

Barocas and Selbst argue that discrimination may result from the decisions taken already at this early stage of the algorithmic design,Footnote 149 notably when defining the target variable involves the creation of new classes. A “good migrant”/“bad migrant” detector, such as ETIAS, serves as a perfect example of this phenomenon. The “risk of illegal migration”, which ETIAS is supposed to detect, is actually an “artifact of the problem definition itself”.Footnote 150 Firstly, at the more general level, this is because ETIAS is a tool of the legal production of migrant illegality.Footnote 151 Unlike earthquakes, which other data-mining algorithms seek to detect, the risk of undocumented migration does not exist outside of the legal and technical infrastructure (of irregularisation) of which ETIAS is a part. In this way, ETIAS contributes to creating illegal migration, which it is designed to combat. Secondly, the algorithmic definition of irregular migration and the related risks performatively create the sociolegal condition of the irregular migrant. As will be explained in more detail below, what is meant by “irregular migration risk” is subject to a changingFootnote 152 and quite arbitrary definition. Thus, ETIAS defines the irregular migration risk, which it pretends to proactively prevent.

b. Training data

Any data-mining algorithm learns from examples to find relevant correlations. This means that ETIAS, whose aim is to detect potentially dangerous travellers, will learn from data regarding persons who have been “labelled” dangerous and thus stopped at the border in the past. But what happens if the data on the border checks and border detention reflect a strong bias due to the discriminatory nature of these practices or systematic errors in the data collection? As Barocas and Selbst explain, “biased training data leads to discriminatory models”.Footnote 153 This bias may intervene, according to the authors, in two ways. Firstly, if bias has played some role in qualifying valid examples for learning, it will be reproduced by the algorithm. Secondly, if data mining draws conclusions from a biased sample of the population, any decision based on these conclusions may systematically disadvantage those who are under- or over-represented in the data set.Footnote 154

A closer reading of ETIAS Regulation gives a clue as to the potentially adverse impact of biased labelling examples. Following Article 33, paragraph 2(c), the security, irregular immigration or high epidemic risks should be defined by the Commission on the basis, among others, of the “information substantiated by factual and evidence-based elements provided by Member States concerning abnormal rates of overstaying and refusals of entry for a specific group of travellers for that Member State”. If these “abnormal rates of refusals of entry” are themselves shaped by the discriminatory practices of border guards,Footnote 155 ETIAS is deemed to reproduce or even amplify this historical bias. Anyone who has visited an international airport may confirm that the criteria of target selection of border checks are far from colour-blind. Some 79% of border guards consider ethnicity as a helpful indicator for effectively recognising persons attempting to enter the country in an irregular manner before speaking to them, according to a FRA study.Footnote 156 This figure reaches 100% in some of the European airports examined in the study. This practice is very likely to be ruled discriminatory, as a judgment of a Higher Administrative Court of Rhineland-Palatinate in Germany shows.Footnote 157 ETIAS’s algorithmic design is deemed to reproduce the discriminatory and potentially racist practices of border guards.

Secondly, as noted above, if data mining draws conclusions from a biased sample of the population, any decision based on these conclusions may systematically disadvantage those who are under- or over-represented in the data set. A more detailed reading of the ETIAS agreement gives, once again, a perfect example of this mechanism. Apart from the commonplace errors in administrative databases on third-country nationals,Footnote 158 structural biases may actually be encoded in the program. According to Article 33, paragraphs 2(a) and (c), the statistics generated by ETIAS shall be correlated with the EES statistics to explore the characteristics of the specific groups of travellers that tend to overstay. This may seem to be a perfectly rational measure that aims to detect the “illegal immigration risk”. However, according to EES Regulation (which refers to the Schengen Code),Footnote 159 any person who has lodged an application for asylum or for a residence permit during their authorised stay will be considered an overstayer from the ninety-first day of their stay and thus registered as such. From a legal point of view, such an applicant is in a precarious but regular situation. Nevertheless, they will appear in the EES statistics as an “overstayer” until their application is successfully processed (or until their return in the case of rejection). For asylum or naturalisation applications, this can take several years. During this period, travellers having characteristics (nationality, place of residence, sex, etc.) similar to persons who have lodged a residence or asylum application will be considered as representing an “illegal migration risk” by ETIAS.

Consider the example of Venezuelans, whose asylum applications have been growing considerably over the past few years.Footnote 160 If these trends continue after the EES’s entry into force, Venezuelans will be overrepresented in the overstayers statistics, even if, for the most part, they will be legally residing in a given Member State waiting for their asylum application to be examined. As a consequence, the new (Venezuelan) candidates for travel to Europe will be more likely to see their demands of authorisation of entry refused by the National Units on the basis of high irregular migration risk, as defined by ETIAS. The growing number of refusals of travel authorisation may have two consequences. The first is a potential rise in attempts of unauthorised border crossing, logically leading to a higher number of refusals of entry at the border, and the second is the decreasing number of authorised entries registered by ETIAS, leading to the underrepresentation of Venezuelans in the ETIAS statistics. Both of these consequences will lead to a self-reinforcing effect confirming and amplifying the effects of ETIAS’s predictions.Footnote 161 Therefore, one might go so far as to conclude that the aim of the system is not so much to fight against irregular immigration but instead to combat any form of immigration altogether.

Although this view can be considered rather pessimistic, there are arguably ways to prevent this issue to some extent. Indeed, while establishing the specific risk indicators, the Central Unit, after consulting the ETIAS Screening Board (which are both human components), could or should take into account the rise in applications for international protection and therefore neutralise – for example – the criterion based on nationality or any other parameters it believes relevant to avoid potential biases. Therefore, human oversight, which is part of the EU’s framework on trustworthy AI, might in some respects be an answer to the issue we have just identified. However, this is not to say that human intervention is, by itself, sufficient. This will depend, among many other things, on whether the Central Unit will actually pay attention to such potential harm, and this cannot be taken for granted, especially when one knows that the groups of people who will be targeted by the adverse treatments will have little or no opportunity to make their voices heard as they are not EU citizens or on EU territory.

c. Feature selection

Bias may occur also at the stage of feature selection; that is, the process of selecting a subset of relevant features (variables, predictors) for use in model construction. Data are only a simplified form of representation of complex social phenomena. The selection of the attributes that should and should not be taken into account in the analysis is never a neutral decision, notably because “members of protected classes may find that they are subject to systematically less accurate classifications or predictions because the details necessary to achieve equally accurate determinations reside at a level of granularity and coverage that the selected features fail to achieve”.Footnote 162 Frederick Schauer explains that decision-makers may be “simultaneously rational and unfair” if they rely on “statistically sound but nonuniversal generalisations”.Footnote 163

Certainly, six basic sociodemographic categories considered by ETIAS cannot reflect (nor accurately predict) the complexity of migration phenomena. As stated above, the profiling performed by ETIAS does not really involve advanced Big Data techniques, since it is limited to a relatively small number of attributes. Thus, the conclusions drawn by ETIAS screening rules may be statistically accurate but still highly approximate.Footnote 164 For example, ETIAS is blind to factors such as the applicant’s family situation, heritage, knowledge of the language and disabilities or the presence of their family members in the country of destination, even though all of these may have a significant impact on the “risk of irregular migration”. This data scarcity logically implies highly approximate results. They may disadvantage some groups of travellers bearing attributes diminishing the risk of irregular migration (eg paternity), since they may be associated with a given “risk profile” because of their age, nationality and level of education, notwithstanding these additional characteristics. Of course, by bringing to light the risk of bias induced by a relatively small number of attributes in feature selection, we are not calling for the addition of further types of data to the questionnaire. Our aim here is merely to put into question the objectivity of the results obtained by the screening rules.

Apart from this, the choice of attributes/features itself can reveal unfair outcomes for specific groups of travellers. The “current occupation” serves as a telling example. The Central Unit might consider it relevant to establish profiles of (say, security) risk in which particular job categories are qualified as “suspect” for some reasons we simply ignore. Journalists or human rights activists might then be prevented from crossing the EU’s external borders based (solely or partially) on their occupation. ETIAS Regulation explicitly encourages this in Article 33(4). It leaves the door ajar to the arbitrary selection of jobs that are perfectly suited for the EU’s political, economic and social strategies (while excluding those that are not), without the possibility of clearly understanding the reasons why such choices are made by the Central Unit.Footnote 165

d. Proxy

“Proxy discrimination” is currently a common term in the literature on law and AI. In brief, it refers to the fact that algorithmic data processing can produce adverse effects on specific groups even when protected characteristics are not inputted as permissible variables. This often occurs when a model “may easily detect other variables and ‘neutral’ data points that are closely related to those characteristics”.Footnote 166 This kind of indirect discrimination may be non-intentional when the examined attributes that “are genuinely relevant in making rational and well-informed decisions also happen to serve as reliable proxies for class membership”.Footnote 167 The notion of proxy discrimination seems particularity relevant to grasping the risk of bias posed by ETIAS’s screening rules.

Article 33(5) of the Regulation, which mirrors Article 14, guarantees that specific risk indicators “shall in no circumstances be based on information revealing a person’s colour, race, ethnic or social origin, genetic features, language, political or any other opinion, religion or philosophical belief, trade union membership, membership of a national minority, property, birth, disability, or sexual orientation”. Nevertheless, as the notion of proxy discrimination indicates, blinding the screening rules to these “sensitive social categories” does not mean that unfavourable treatment based on these characteristics may not occur. This is for two reasons. Firstly, membership in a protected class may be encoded in other data. Thus, “race” or ethnic origin may be “deduced” from other, non-suspicious data, such as nationality, place of residence and education level. Moreover, there is no definition of the scope and limits of the prohibited grounds, so the degree of overlap with proxies required for the protection to apply is unclear.Footnote 168 Secondly, and more generally, even a perfectly accurate model of irregular immigration risk will be discriminatory on the ground of “race”, on account of the racialised (or racist) reality that it describes. A great majority of undocumented third-country nationals residing in Europe belong to racial or ethnic minorities. Consequently, ETIAS is compelled to encode their race or ethnic origin when processing their data. This conclusion is valid for most immigration law enforcement measures, be they digital or not. As stated by the United Nations Special Rapporteur on contemporary forms of racism: “States regularly engage in racial discrimination in access to citizenship, nationality or immigration status through policies and rhetoric that make no reference to race, ethnicity or national origin, and that are wrongly presumed to apply equally to all”.Footnote 169

Unidimensional proxy discrimination is not the only type of discrimination that is relevant here. According to Article 33(4) of ETIAS Regulation, specific risk indicators will consist of “a combination of data including one or several of the following characteristics: age range, sex, nationality, country and city of residence, level of education, current occupation” (emphasis added). While it is guaranteed that specific risk indicators “shall in no circumstances be based solely on a person’s sex or age” (paragraph 5; emphasis added), meaning that ETIAS may not automatically deny an authorisation to all women or all persons in the age group between twenty and twenty-five, for example, it may very well identify women between twenty and twenty-five years of age as belonging to a risk profile. Though admittedly simplistic, this example gets the key point across. Thus, risk profiles may be located at the intersection of illegal motives of discrimination. This is why the notion of intersectional discrimination (ie that occurring at the intersection of more than one protected groundFootnote 170) seems particularly relevant to understanding the adverse impacts of ETIAS’s profiling. Because specific risk indicators combine attributes constituting protected grounds (sex and age) with other, seemingly non-suspicious grounds (nationality, residence, level of education and occupation), which may serve as proxies for other protected grounds (“race” or ethnic origin), they are intersectional by design.

As demonstrated in the seminal work of Kimberlé Crenshaw,Footnote 171 victims of intersectional discrimination experience specific difficulties in proving the discrimination that they suffer from. Consider the following example: an established risk profile points at highly educated women in their twenties coming from big towns in Serbia. They will fall short of establishing a prima facie case of (unidimensional) discrimination. If there is no hint in the ETIAS statistics that women in general are subject to higher rates of refusal than men, no discrimination on the ground of sex occurs. The same is true if the rate of refusal for the whole group of highly educated persons is similar to poorly educated ones or if the rate of refusal for all persons in their twenties is the same to that for older people. Neither group may prove that they were treated unfavourably solely on the basis of their nationality. This is why the strongly embodied single-axis testing tools set forth,Footnote 172 which look for a biased distribution of error rates according to a single variable only, such as race or sex, will not be sufficient to assess the risk of adverse impacts posed by ETIAS. Only intersectional bias auditsFootnote 173 may adequately do so.

e. Masking

This brings us to the last point brought up by Barocas and Selbst: data mining may also be intentionally used for discriminatory purposes. All discrimination begins with a distinction. The task of an algorithm is precisely to operationalise this distinction. ETIAS screening rules distinguish groups of travellers previously indistinguishable (at least systematically) by the hierarchical legal system of global mobility. To better understand this point, we tackle the purpose of establishing travel authorisation for visa-exempt third-country nationals.

As explained in Section II of this article, ETIAS “fills the gap” presumed to exist in the EU surveillance of global mobility. As such, it is part of “the global mobility infrastructure”, which Thomas Spijkerboer defines as “physical structures, services and laws that enable some people to move across the globe with high speed, low risk, and low cost”.Footnote 174 This perspective shows that ETIAS is not merely a tool of exclusion or just another brick in the wall enclosing the European fortress. Rather, we propose to analyse it also as an instrument of selective and differentiated inclusion, which stimulates the cross-border mobility of some categories of people while restricting the rights of entry of other, “undesirable” travellers. By regulating access to the global mobility infrastructure through instruments such as visa systems, ETIAS and ESTA or carrier sanctions rather than controlling access to their sovereign territories, Global North countries can pursue their aim of increased human mobility while at the same time maintaining sovereign control over their territories and populations.Footnote 175

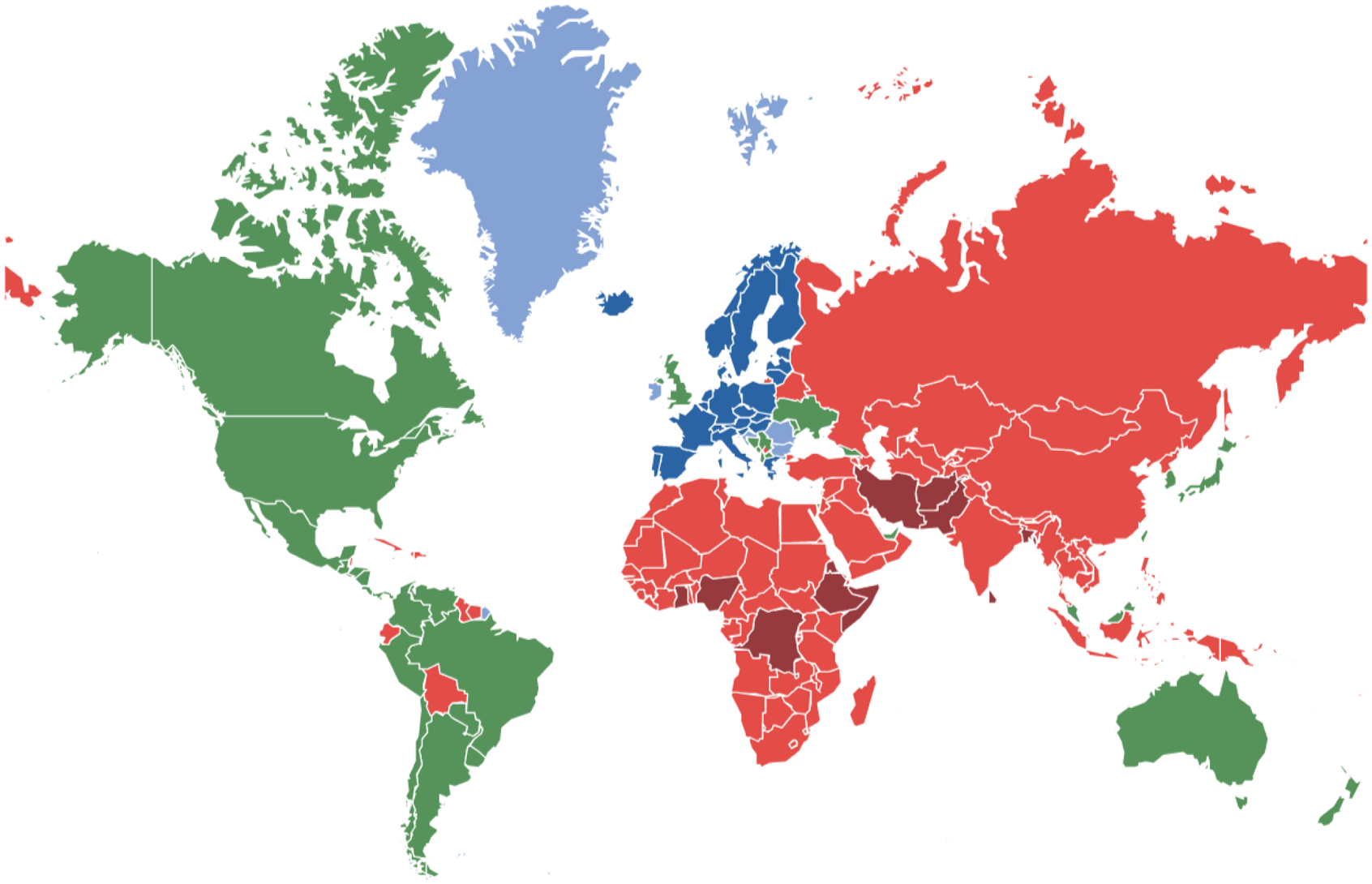

The EU visa system is undeniably a key element in the control over access to the global mobility infrastructure. It is enough to look at the map representing the countries whose nationals are subjected to visa requirements (Figure 3) in order to see that it approximately (with the exception of certain South American countries) reflects the Global North/Global South divide. Moreover, a great majority of visa-exempted countries are traditionally Christian. One could say that the visa obligations imposed on poor and non-Christian countries hosting racialised populations basically represent a presumption of undesirability in the Schengen Area.

Figure 3. The European Union’s (EU) visa policy. In dark blue: Schengen Area; in light blue: EU states and territories of EU states not part of Schengen and other exceptions; in green: no visa required to enter the EU; in light red: visa required to enter the EU; in dark red: visa and airport transit visa required to enter the EU. Source: European Commission (2021). Note that the Southern Hemisphere seems abnormally compressed.