Introduction

Spheres of influence are one of the most commonly referenced yet analytically neglected concepts in international politics. Scholars only rarely use the term, and few have posited clear assumptions or parsimonious causal propositions about them, let alone explored the implications of different understandings of the concept for either the discipline or the practice of international politics.Footnote 1 Spheres of influence are generally understood as a hierarchical structure, the construction and maintenance of which results from a practice involving two specific features: some amount of control over a given territory or polity by a foreign/outside actor, especially as regards third-party relations, and exclusion of other external actors from exercising that same kind of control over the same space.Footnote 2 But the logic, mechanisms, and implications of these features – that is, how and why control and exclusion occurs – can vary significantly depending on key analytical assumptions that derive from divergent theoretical traditions.

Historical analysis is replete with references to spheres of influence, as is much of nineteenth-century history, which saw governments employing the term in the practice of peripheral diplomacy. The term ‘sphere of influence’ has subsequently been used in historiography to frame everything from the structure of Athenian and Spartan empires during the Peloponnesian War to the tributary system on China's periphery during the Qing Dynasty.Footnote 3 More recently, even the most authoritative narratives of Cold War history understand US and Soviet systems as competing spheres of influence.Footnote 4 The term is also indispensable to understanding Western imperial competition in Asia and Africa during the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries because Western governments themselves used the term in diplomatic practice.Footnote 5 Geopolitical strategist Lord Curzon records the earliest known use of the term in 1869, when Russia's foreign minister conveyed to the British that Afghanistan was ‘completely outside the sphere within which Russia might be called upon to exercise her influence’.Footnote 6 As the United States in particular sought to expand its markets into Asia during this same period, it contended with what officials then understood as established spheres of influence in China, Japan, Korea, and parts of the Pacific Islands, staking out its later ‘Open Door’ trade policy as a way to maneuver within and across these spheres.Footnote 7 And for decades before Hawaii became part of the United States, it was considered by other imperial powers as part of an American sphere of influence.Footnote 8

But ‘spheres of influence’ are not only relics of the past. At the beginning of President Barack Obama's term of office in 2009, Vice President Joseph Biden stated ‘We will not recognize a [Russian] sphere of influence. It will remain our view that sovereign states have the right to make their own decisions and choose their own alliances.’Footnote 9 Five years later, the Obama administration would recommit to its rhetorical opposition to spheres of influence. In 2014, speaking to a crowd in Ukraine just months after Russia's intervention there, President Obama declared that ‘The days of empires and spheres of influence are over.’Footnote 10 Also speaking from Ukraine the following year, Biden added that ‘We will not recognize any nation having a sphere of influence.’Footnote 11

Spheres of influence are also part of the discursive landscape characterising contemporary Asia. Some observers claim that China ‘simply wants a sphere of influence that increases its global clout’, but that it would involve the United States abandoning any security commitment to Taiwan, suggesting spheres of influence may be a diplomatic concept capable of resolving regional tensions.Footnote 12 For decades Southeast Asian states have crafted national security strategy with an aim of avoiding what they consider either US or Chinese spheres of influence.Footnote 13 South Korean policy elites similarly express angst about being trapped between competing US and Chinese spheres of influence.Footnote 14 And strategic studies scholars refer to ‘a system of competing spheres of influence in the Western Pacific’ that defines unchallengeable areas of control separating the United States and China.Footnote 15

How do we account for the pervasiveness of references to spheres of influence historically and in practice but not within the academy? And how do spheres of influence relate to other conceptions of international hierarchy?

This article advances two arguments. First, it argues that spheres of influence are not a distinct form of hierarchy in international relations, but rather hierarchical practices of control and exclusion. These practices do not imply – by themselves – a form of governance. Various ideal-type hierarchies in international relations may also be spheres of influence if the practices located within them involve patterns of control and exclusion. Second, these practices are generally underspecified. Different theoretical perspectives on international relations have dealt extensively with the concepts of control and exclusion, but in highly divergent ways depending on grounding assumptions.

Notwithstanding the rarity with which spheres of influence have been an object of analysis in international relations, several bodies of established theory can nevertheless help with the task.

Geopolitical realism provides a classical conception of spheres of influence as the geographic range of a major power's military dominance for the purposes of control and exclusion. In this instrumental-materialist view, spheres of influence are obtained and maintained through fear and coercive power, which is limited to the distance over which it is able to credibly project power to defend or control territories and peoples within that space. Rational contractualism explains spheres of influence as hegemonic orders at any scale, from global to subregional, or even of a single protectorate. From the contractualist perspective, spheres of influence originate from strategic bargains struck between hegemons and client states or allies. Constructivism, in the Wendtian sense of identity construction and co-constitution, offers an understanding of spheres of influence as shared transborder identity discourses that originate from a primary nation or actor. The constructivist interpretation emphasises the common representation of ‘self’, or convergence towards in-group solidarity, as the basis for a legitimate claim to control and exclusion exercised through processes of socialisation and localisation. And the burgeoning literature on relationalism renders spheres of influence positionally, as synonymous with network centrality. This sociological approach, which differs from mainstream constructivism in important respects, treats durable patterns of relations among social actors as structures that influence them; the control and exclusion features of a sphere of influence refer to the availability of opportunities that derive from the structure of ties between a core actor and peripheral ones.

Making ideal-typical comparisons matters because differing assumptions about control and exclusion become the basis for competing hypotheses about alignment behaviour and the reasons for respecting or contesting exclusion and control. More generally, the ability to identify and define spheres of influence in theory gives us the ability to do so more transparently in practice, which translates into a more nuanced discourse about and map of the structure(s) of international politics than traditional caricatures of ‘states under anarchy’ allows; international hierarchy can exist as multiple patchworks that are separate from, overlapping with, or competing among one another.

The remainder of this article proceeds in three parts. The first part outlines core assumptions of four different theoretical traditions on questions of control and exclusion – the defining elements of spheres of influence. The second part explains how these contrasting assumptions lead to variegated expectations about why and when smaller actors align with larger ones, and prima facie scope conditions for contesting spheres of influence, from within and without. The third part discusses the implications of understanding spheres of influence in different ways and how the term does not challenge – but rather complements – the extant hierarchy literature. The term ‘sphere of influence’ is not meaningless or redundant, but by itself fails to clarify the ways in which control and exclusion occur.

Grounding assumptions of control and exclusion

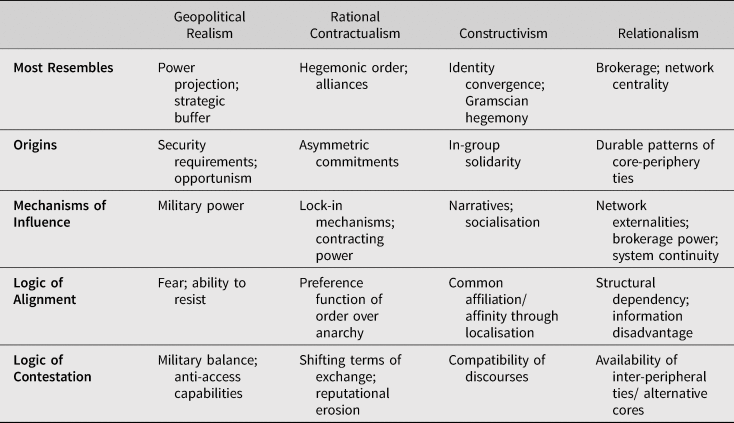

Contrasting assumptions separate four different ways of conceptualising spheres of influence, shown in Table 1.

Table 1. Understanding spheres of influence: Four ideal-type approaches.

There are numerous ways to compare and contrast these theoretical groupings, but I do so below in relation to the specific characteristics of spheres of influence – control and exclusion. As I demonstrate in the next section, these particular sets of assumptions lead to divergent expectations about alignment behaviour of secondary powers and the accordant logic of contestation from within, and external to, a sphere of influence.

Geopolitical realism

Although realism comes in many variants, the literature demonstrates a common tendency towards the Thucydidean notion that ‘the strong do what they can and the weak suffer what they must’. Scholars in this tradition assume that states exist in an anarchical system that demands they provide for their own security.Footnote 16 Material power, in the form of economic or military capacity, is seen as the only reliable means to adjudicate international politics. While many realists also accommodate ideational factors in their research, there is nevertheless an emphasis within much of the realist tradition on geopolitics – the role of geography in shaping the distribution of opportunities and constraints of power politics.Footnote 17

Several assumed motivations for why a great power would seek to establish a sphere of influence fit with a geopolitical realist interpretation. A common reason is to establish a ‘strategic buffer’ around the central power that creates greater physical separation from potential threatening external actors.Footnote 18 The strategic buffer argument is an historically frequent rationale for states claiming spheres of influence. In the latter half of the nineteenth century, a primary rationale among US political elites and naval officers for annexing Hawaii was to establish a strategic buffer for America's recently settled West Coast territorial acquisitions.Footnote 19 More recently, China's policy towards North and South Korea treats the Korean Peninsula as a strategic buffer against US encroachment.Footnote 20 But great powers might also seek spheres of influence for the opposite reason; rather than bolstering a strong defence, certain foreign territories might improve a state's ability to wage a strong offense.Footnote 21 Although not mutually exclusive, whether a controlled foreign territory is a strategic buffer or a platform for greater power projection may hinge on an offensive versus defensive realist assumption.Footnote 22 A third motivation for seeking a sphere of influence is pure economic exploitation. Material resources and economic capacity are crucial inputs into political processes of resource mobilisation that translates them into military power.Footnote 23 A great power may therefore seek control and exclusion of a foreign territory for purposes of resource (including labour) extraction. This was the dominant thinking among the Western imperial powers operating in Asia prior to the First World War. The perception that resources were finite but also the foundation of military prowess sparked a competition for control of territories and markets in Asia that led to unequal treaties, territorial cessions, and jockeying for influence among European powers, far from Europe's shores.Footnote 24

In this reductionist worldview, the ability to credibly exercise military power in particular spaces is what undergirds the claim to a sphere of influence; the aforementioned motivations cannot be indulged without the ability to project military power. Such a ‘might makes right’ world ultimately moots questions of legitimacy and order in favour of questions about relative material strength embedded within particular geographic settings.Footnote 25 This helps to explain why spheres of influence often take the form of strategic geographic buffers for great powers throughout history – among foreign territories, it is a great power's near periphery that is most militarily defensible and controllable. Distance imposes an intrinsic difficulty for power projection, even in an age of long-range precision munitions.Footnote 26 Power projection is thus the basis for asserting control over a foreign territory and excluding others from doing the same within that territory. In a world where force is the ultimate arbiter of disagreements and guarantor of security, credible military superiority over a smaller territory – and in relation to other comers – is the only way to either stake claims of control and exclusion or to contest them.

Rational contractualism

The rationalist ontology from which geopolitical realism is derived accommodates more than one way of thinking about spheres of influence. Like geopolitical realism, rational contractualism traces political outcomes to the microfoundations of egoistic, utility-maximising actors.Footnote 27 But unlike geopolitical realism, it makes assumptions that explicitly accommodate mechanisms other than military force. A rational contractualist approach reflects a Lockean emphasis on strategic bargains between states that, while possibly granting significant advantages to the larger power, fundamentally depend on contracted terms of exchange and the ability of the larger power to make credible commitments.Footnote 28

It provides for this distinction by assuming that, with a sufficient shadow of the future, states can effectively learn their way out of the worst excesses of anarchy.Footnote 29 Asymmetric bargains between larger and smaller powers result in structured arrangements that come to define control and exclusion as the functions of a hegemonic order. Notably, these hegemonic contracts can be distinctly military,Footnote 30 economic,Footnote 31 or political in nature,Footnote 32 depending on the particular scope of exchange. The key to identifying a rational contractual sphere of influence is the presence of specified rights, privileges, and responsibilities on both sides of a transaction that results in some form of control and exclusion by consent, especially of the smaller state's freedom of action with third parties.

The rational contractualist approach does not deny a role for military power projection. Asymmetric material strength drives the formation of dominant-subordinate social contracts. But the ability to dominate militarily or economically is not how a hegemon generates and reproduces control and exclusion over a smaller territory or ally. There must be mechanisms of authority that translate or ‘cash out’ superiority. Through a rational-contractual lens, the means of control and exclusion that create spheres of influence are mutual agreements that delineate roles and specify the terms of sovereignty compromises. Asymmetric commitments thought of in this way represent a large conceptual waterfront – ranging from constitutional orders to hegemonic stability to bilateral alliances or protectorates – with common microfoundations. Different theories in this vein may emphasise political character,Footnote 33 military superiority,Footnote 34 and strategic bargainsFootnote 35 to varying degrees in their interpretations of contractual hierarchy, but all share a commitment to analytical assumptions of learning, transactional exchange, and mutual consent for generating and sustaining control and exclusion. These assumptions make it possible for institutions and social understandings to serve as the instruments of control and exclusion between dominant and subordinate states.

Great powers may seek to reap material advantage through the establishment of hegemonic leadership over a given space, or they may be motivated to escape endless challenges to their security and their preferences. G. John Ikenberry's formulation in particular identifies a core motivation of the liberal variant of hegemonic leadership – recognition that while material supremacy cannot last indefinitely, during the ‘founding moments’ of system ordering it offers an opportunity to ‘lock-in’ asymmetries for extended periods that might not be possible in future circumstances of greater power symmetry among contracting agents.Footnote 36 There can be neither hierarchy nor stability in a world where smaller powers continuously challenge a great power's system preferences. The terms of exchange are born accordingly. The hegemon agrees to responsibilities that come attached to grants of authority – whether strategic restraint, system stability and order enforcement, or guarantees of client security – and the smaller power(s) agree/s to circumscribe their sovereignty, within mutually understood limits. In one rational-contractual account of spheres of influence, for instance, the ‘dominant state possesses the authority only to limit a subordinate's cooperation with third parties’.Footnote 37 Exclusion implies control over third-party cooperation, but the terms of asymmetric bargain need not be limited only to this. As long as the hegemon maintains its material superiority and the hegemonic order allows the smaller power to escape the predation of anarchy, the terms of exchange can hold and thus a sphere of influence can obtain.

Constructivism

A great diversity of theories and interpretive modes of analysis fall within the constructivist tradition. Alexander Wendt's strand of constructivism is most useful for understanding spheres of influence in part because it draws the sharpest distinctions with the other theoretical approaches.Footnote 38 Wendt and others grant the assumption that the international system is descriptively anarchical and states remain an important unit of analysis. And yet constructivism's embrace of a sociological, rather than rational, ontology establishes a core set of assumptions that lead to a different orientation towards international relations than the rationalist traditions described above. The most basic and universal of these assumptions is the social nature of international politics; states (and the people within them) are fundamentally social actors, and the meaning assigned to material circumstances depends on intersubjective understandings they share or contest.Footnote 39

As such, a group or state's interests cannot be assumed from the distribution of military power or quid pro quo exchanges of sovereignty and security. Instead, constructivism problematises interests with reference to group norms and identities. A state's interests in international relations cannot be exogenously assumed if they are determined by shared understandings rather than material reality. The content of interests hinges on actor identity and the norms to which they subscribe; they are mutually constituted.Footnote 40 Thus, the question of national interest, or how international anarchy drives state behaviour, requires inquiring about actor/group identity; the socially constructed, rather than material, attributes of an actor become the object of analysis.Footnote 41 As a result, actor behaviour in constructivism is seen to follow logics of appropriateness and affect, rather than the logic of consequences that governs behaviour in rationalist theories.Footnote 42

Constructivism's identity-focused understanding of international politics recasts the control and exclusion that makes up a sphere of influence. If a sphere is socially constructed –rendering control and exclusion normative rather than instrumental constructs – then we look to identity content (national or ethnic narratives, value systems, or cultural practices) and corresponding shared ideas to account for it. This permits a degree of pluralism in recognising actor relations. The principal axis of international relations may still be interaction between states, but because the constructivist focus is on bonds of convergent practices and identities, there is no reason to make an ex ante assumption that identities are confined to only one kind of unit.Footnote 43

But regardless whether we deal only in states or also embrace social groups as salient actors, spheres of influence are constructed through socialisation that transmits identity traits and forges in-group solidarity, between a primary state and other states (or social groups) that grant a degree of uncoerced subordination to the primary state. Exclusion falls along identity boundaries, and control is interpreted as affect, shared symbols, or accepted narratives that reinforce such identities; both are produced and sustained through practices of exchange or interaction.Footnote 44 Discourses, in other words, become a source of exclusion and control by establishing boundaries and serving as behavioural heuristics.Footnote 45 This is well illustrated in the historiography of Sino-centric Asia and the ‘Eastern International Relations theory’ turn in Asian security studies. China has historically maintained a system of paternalistic order with smaller nations on its periphery, and the claim among Eastern IR theorists is that it did so less through military force projection or credible assurances of protection to smaller states than through cultural diffusion (which facilitates identity convergence) and accepted narratives and practices that reified China as the ‘middle kingdom’.Footnote 46 This system alienated outside powers while allowing China to impose a degree of political control on its neighbours. When European imperial powers tried to penetrate the China market, they were unsuccessful until they adapted to the various symbolic practices that recognised and reified the control and exclusion that comprised the Sino-centric order.Footnote 47

Relationalism

Like cultural constructivism, relationalism in IR draws from a social ontology that presumes material reality only takes on meaning through intersubjective understanding.Footnote 48 For this reason, some believe relationalism should be seen as a subsidiary of the constructivist research programme in IR.Footnote 49 Whatever the merits of considering relationalism within a ‘big tent’ of constructivist tradition, the differences with the narrow Americanised variant of constructivism delineated above demand separation for purposes here, just as realism and contractualism demand separation despite sharing a common commitment to rationalism. Scholars who operate in the relationalist mode, moreover, tend to see themselves as distinct from the dominant ‘isms’ of IR – realism, liberalism, and constructivism – because these ‘isms’ are ‘substantialist’, dealing primarily in essences and attributes rather than relations.Footnote 50 Following this substantialist-relationalist separation, the latter's most salient point of departure from cultural constructivism is its commitment to shifting analytical focus from actors and their attributes to the ties of symbolic or material exchange between actors, which take on structural properties over time.Footnote 51

Relationalism takes seriously the philosophical premise that webs of relations are the gateway to understanding social systems and the actors that co-constitute them. Even if we seek only to understand an actor's attributes and behaviours – and not the origins, topological mapping, and implications of relational structures actors are embedded in – we cannot do so without first understanding the universe of relations surrounding the actor, because they co-constitute the actor.Footnote 52 For relationalists, much can be revealed by the densities, frequencies, and lengths of actors’ social ties, which are inherently not fixed or static, even when durable or recurring. So whereas substantialist research programmes examine relations from an analytical assumption that actors or entities exist prior to entering into ties with others, relationalists privilege relations themselves as analytical priors. And because sets of relations (networks) demonstrate isomorphic tendencies – that is, similarly patterned network structures often demonstrate common emergent logics, constraints, and opportunities across space and time – the relationalist sensibility draws out causal and interpretive insights that other approaches neglect.

In contrast with other approaches, then, the stark, differential underpinnings of a relational approach lead to a radically different understanding of spheres of influence. Within these bounding assumptions, an asymmetry of control and exclusion produce and are produced by patterns of relations between core actors and peripheral ones. Put another way, control and exclusion are advantages or implications of network centrality, a particular type of structured relational configuration in which the ties of a single actor/node account for a disproportionate percentage of all ties that constitute a network.Footnote 53 A network in which only one or a few actors display high ‘degree centrality’ (in the language of network analysis) offers distinct advantages and disadvantages relative to an actor's position in the core versus the periphery.Footnote 54

Core actor control over peripheral actors, and exclusion of out-of-network actors, derives from their role as an intermediary between unconnected actors (brokerage power),Footnote 55 their importance to system or structural continuity (externalities),Footnote 56 and their ability to engage in heterogeneous contracting (exploiting information asymmetries) across unconnected actors.Footnote 57 As intermediaries between unconnected peripheral actors, core actors in a network can either broker ties or buffer them. During much of the nineteenth century, the British empire dominated Western trade with China and, through its victory over China in the Opium Wars, was able to extract favourable rights and privileges that eventually made the British central to gaining access to the China market.Footnote 58 Subsequently, late entrants – such as the United States – could not establish meaningful ties without currying favour with British representatives in China who understood the cultural landscape, knew the local Chinese players of influence, ran the banks through which American transactions passed, and occupied privileged positions in the foreign customs houses. US diplomats and businesses at the time relied on the good offices of the British for entry.Footnote 59

Network centrality also positions the core actor to exert control by virtue of its disproportionate importance to structural or system continuity, generating network ‘effects’ or ‘externalities’.Footnote 60 When peripheral actors that benefit from status quo constellations of relations in a network exhibiting high degree centrality are highly averse to any significant reconfiguration of relational patterns, they interact in ways that reinforce network centrality, making patterns of relations partly endogenous to existing patterns of relations.Footnote 61 Successful social media companies operate according to this logic, explicitly seeking to reach a tipping point by which the sheer number of users itself becomes an incentive for existing users to stay and new users to opt in.Footnote 62 In contemporary Asia, it has become commonplace for Asian states to rely disproportionately on China for trade and investment while still looking to the United States as a security provider.Footnote 63 Although these patterns are leading to a bifurcated regional order that places cross-pressures on Asia's peripheral powers in both realms, their relational patterns continue to reinforce Chinese economic centrality and US security centrality respectively; peripheral powers do not want to divest of China trade or US security provisions, even if those simultaneous relational patterns give rise to a contested and fractious regional order.Footnote 64

A third way that network centrality enables control and exclusion is through ‘heterogeneous contracting’, a structural property of imperial rule.Footnote 65 When peripheral actors’ strongest, most direct, and most frequent relations are with a core actor (and not with other peripheral actors), the latter benefits from information asymmetry; the core actor has the advantage of establishing preferential or concessionary terms of exchange with one peripheral actor without other peripheral actors discovering those terms and demanding similar treatment.Footnote 66 In this way, core actors are uniquely positioned to minimise their own obligations relative to the rights they secure from peripheral actors by stifling collective demands against them. In ideal-typical empires operating in Africa and the Middle East, European core actors maintained control of peripheral colonies in part by exploiting the informational asymmetry they enjoyed over the periphery, establishing bargains and terms of intermediary governance based on local conditions without having to replicate them across peripheral relations. The sparseness of inter-peripheral ties, in turn, enabled imperial cores to pursue ‘divide-and-rule’ strategies that made collective action or resistance against the empire less likely to spill over from one peripheral area to another.Footnote 67

Explaining alignment and contestation

The prior section outlined core assumptions of four different research traditions and explained how those assumptions differently understand the control and exclusion mechanisms that define spheres of influence. On the basis of these divergent understandings of control and exclusion, this section identifies distinct hypotheses that emphasise the other side of spheres of influence. Rather than focusing either on great power reasoning, discursive practices, or the relational structures they impose on others, it considers the logic of weaker powers’ alignment with or resistance to claims of control and exclusion by more powerful polities, as well as the corresponding logic of third parties’ recognition of or challenge to others’ spheres of influence.

Geopolitical realism: Challenging power projection

The geopolitical realist approach posits a supply-side explanation for both weak-state acquiescence to great power impositions of control and exclusion, and contestation thereof. Weak states align with the demands of powerful ones when they are unable to mount meaningful challenges to the latter's power projection capabilities. In an anarchical system where survival is the paramount goal, small states will not enter into fights they have no hope of escaping from intact, and will instead align with a great power that asserts control over it when they believe that ‘resistance is futile’.Footnote 68 For the weak state, a compromise of sovereignty is preferable to a total loss of it.

This landscape – involving anarchy, irreducible uncertainty about intentions, and an overriding goal of survival – gives rise to key determinants of weak-state alignment behaviour: the military balance;Footnote 69 the relative advantage or disadvantage afforded by geography;Footnote 70 the capacity to blunt power projection through asymmetric means despite military inferiority;Footnote 71 and the availability of alternative patrons or allies.Footnote 72 Each of these factors are instrumental-material considerations that speak to a weak state's ability to resist the control and exclusion imperatives of a great power. If a weak state can form an external balancing coalition, or if local geography or military-technical trends make defence against attacks relatively easier than offensives, then the balance-of-power school of neorealism suggests it will resist a stronger power's preferences for control and exclusion. But if the military balance suggests a weaker power will be routed by the larger power, if geography or military-technical trends strongly undermine a weaker power's ability to mount a defence against power projection, or if there are no plausible allies with whom the weaker state can rally against the stronger, then a weak state has no alternative to aligning with a great power's control and exclusion prerogatives.

The logic of contestation from without mirrors the logic of resistance from within. External great powers contest the control and exclusion imperatives asserted by other great powers over foreign territories when they can, and when it improves their relative security situation to do so; otherwise they acquiesce. In a world where military advantage adjudicates politics, resistance by resorting to what realists consider epiphenomena – for example, diplomatic protest, recourse to institutions, or appeals to international norms – is insufficient to change the structure of asymmetric relationships based on power.Footnote 73 Challenging another great power's claim of control requires the use of force or the credible threat of it. This means external great powers must incur some material risk or cost to challenge another's claim to control and exclusion. Material determinants are the same as those holding sway over weak-state alignment (the military balance, geography, etc.). Since power projection is what sustains a great power's exclusionary control over another state, meaningful resistance must take the form of countering another's power projection over a territory in dispute, or credibly threatening an ability to do so.Footnote 74 Whether interference in another great power's sphere of influence improves an external great power's relative security situation in turn hinges on fundamentally offensive versus defensive realist assumptions about great power behaviour. Assuming two great powers’ spheres of influence do not overlap, they can accommodate each other's claims to control and exclusion as long as they are assumed to be seeking a balance of power rather than a preponderance of it (that is, they exist in a defensive realist security environment).Footnote 75 But when competing great powers seek primacy or dominance over the same area, military-technical superiority – relative to geographic circumstances – becomes crucial to whether an external great power can and will mount a winning challenge.Footnote 76

Rational contractualism: Bargaining order

When states are capable of learning and expect to engage in iterative transactions, expectations of alignment with and resistance to spheres of influence deviate from those of an ideal-type geopolitical realist approach. Smaller powers agree to cede some degree of control and exclusion to a larger power when the expected costs and benefits of doing so favour hegemonic order over those of self-help anarchy. A smaller power's grant of authority and willful subordination to a larger power does not directly result from great-power coercion of the former but rather a shared acceptance or bargain involving rights and obligations on both sides of the transaction.Footnote 77 In this sense, larger powers present smaller ones with a choice: fend for yourself in an anarchical world, or accede to a hierarchical relationship that promises some degree of protection and stability in exchange for deference to the larger power's preferences in relations with third parties.

Asymmetric contracts understood in this way also generate expectations for when a smaller power will defect or challenge an established bargain: when the hegemon can no longer maintain superiority in whatever measure that enabled an asymmetric bargain in the first place, and when a hegemon can no longer credibly maintain the bargain.Footnote 78 In the former case, the bargain may hold well beyond the hegemon's loss of material superiority, but only if the smaller power continues to prefer holding to the bargain. In the latter case, whether the bargain holds depends on inferences the smaller power makes about the likelihood of a hegemon holding to its promises, which can derive either from projections based on material circumstances or the hegemon's accrued reputation based on its word and deed over time.Footnote 79

As with the cost-benefit logic of alignment and contestation from within, external powers will challenge another power's sphere of influence when they have the means to do so and expect the terms of another power's asymmetric bargain to adversely impact them more over time. An external power whose interests do not coincide or overlap with spheres of influence in the rational-contractualist sense has no cause to concern itself with any transfers of rights and obligations between two or more other powers. Even multiple spheres of influence – asserted by multiple great powers – do not inherently imply challenges against the control and exclusionary claims of one another. Accommodation, as opposed to contestation, is plausible under several conditions. An external power may have no interest in the geographic scope of a claimed sphere of influence. Alternatively, it may have an interest in the geographic scope (that is, a smaller power's territory or polity) but have no stake in the specific terms of the bargain between larger and smaller powers, such as America's nineteenth-century Open Door policy in Asia, which required economic access to Asia but did not challenge European spheres of control over those same countries.Footnote 80 Even a single region can accommodate multiple assertions of regional order as long as the respective great powers’ preferences for order are compatible. As imperial Japan emerged as a dominant player in nineteenth-century Asia, the British empire saw fit to acknowledge the former's growing control arrangements with other territories because at the time Japan was not challenging Britain's control over its areas of dominance in the region.Footnote 81 In any of these instances, a plausible basis exists for external powers to tacitly accommodate, if not explicitly recognise, another's assertion of control and exclusion privileges.

By contrast, an external power will challenge another power's asymmetric bargain with smaller powers if it has future expectations that either the situation will worsen further over time or that its own enlarging interests will grow more in tension with current arrangements. In the vast literature on power transitions, war is the expected outcome from great powers’ clashing preferences for hegemonic order.Footnote 82 A dominant power seeks to preserve a status quo arrangement of rules, norms, and privileges, while a rising power with competing preferences seeks to challenge it. The question of external power challenge to another's assertions of control and exclusion thus becomes one of the compatibility of respective preferences for order.Footnote 83 The risk of contesting – whether by war or other means – the strategic bargains another great power has fixed hinges on either a rising external power's expanding interests and how they intersect with those established bargains, or the opposite, a declining external power whose interests are increasingly harmed by the existing set of bargains.

Constructivism: Identity and discursive compatibility

In one of the only attempts to theorise spheres of influence, Susanna Hast took a critical approach, arguing that ‘Spheres of influence are constructed in discourses …’ and therefore inherently normative constructs.Footnote 84 Constructivism's emphasis on identity and collectively held norms as keys to understanding interest formation and actor behaviour is an alternative basis for explaining the alignment and contestation involved in spheres of influence. Constructivism's eschewal of causality in favour of mutual constitution between agents and structures makes it easier to specify the reason for alignment behaviour (why) than conditions that cause it (when):Footnote 85 secondary actors permit primary actors to exercise control and exclusion over their third-party relations because they share a high degree of identity compatibility. Although not a probabilistic statement, it does lay out an alternative logic to account for alignment behaviour, by stressing identity content and convergences. Still, we can render this understanding into a testable hypothesis in like-terms with rationalist approaches by specifying the mechanisms that produce identity convergence: secondary actors permit primary actors to exercise control and exclusion over their third-party relations when primary actors socialise relevant discourses that are congruent with constitutive norms and discourses of secondary actors.

Seen through this lens, alignment occurs because mutual identification produces conformity. The mechanisms of control and exclusion consist of prescribed discourses – understood as narratives and practices that convey, represent, and reinforce feelings of solidarity or ‘we-ness’ between a primary actor and secondary ones. One state (or social group) generates discourses that it exposes other states to through interaction. Other states (or social groups) then respond to this socialisation by selective adoption through processes of localisation.Footnote 86 Secondary state elites drive this localisation process by identifying and adopting those elements of external norms and discourses that can complement or be grafted to pre-existing internal political circumstances.Footnote 87 Alignment behaviour is thus interpreted as a reflection of successful primary actor socialisation and secondary actor localisation, bringing identities towards greater convergence. Secondary actor relations with third parties are bounded and guided by successfully transmitted discursive frames that ‘constrains how the stuff that the world consists of is ordered, and so how people categorize and think about the world. It constrains what is thought of at all, what is thought as possible, and what is thought of as the “natural thing” to do in a given situation.’Footnote 88 So when secondary actors challenge or resist what might be considered cultural hegemony in a Gramscian sense, they do so because of either inadequate socialisation (insufficient exposure) or incongruence between exported discourses and prevailing local (affective and normative) conditions.

When control and exclusion take the form of successfully transmitted identity discourses, external actor acceptance or contestation depends on their (third-party actor) identity compatibility with the others (primary and secondary actors). To what extent is a third party's constellation of constitutive beliefs congruent or in common with that shared between primary and secondary actors? To respect or contest the ideas and practices that two or more other actors share in common is neither a question of means nor a cost-benefit calculation; rather, it is about grants of legitimacy, which is reducible to a question of compatible identity content between external third parties and others. Where states have internalised opposing notions of permissible practices, conflicts of interest potentially exist and conditions are more favourable for a ‘clash of civilisations’ logic to obtain. As democratic hegemons occupying dominant positions in world politics, for example, Great Britain in the nineteenth century and the United States in the twentieth century each faced numerous challenges from rising expansionist powers. For both states, their approach to managing rising challengers hinged primarily on their similarity or difference in form of governance compared with the rising challenger; each was more likely to respond to rising autocratic regimes with hedging or containment policies while showing a much greater willingness to engage in appeasement of rising democratic powers.Footnote 89 Daniel Kliman traces these variations to the interaction of attributes associated with the different political identities.Footnote 90

Relationalism: Structural dependency and collective action

The relational approach to questions of alignment and contestation yields still another distinct explanation, based on its analytical privileging of ties among units rather than the units themselves. Relationalism's structural perspective emphasises how relational patterns narrow and widen opportunities for collective action, but does not in itself establish microfoundations of individual behavioural incentives, as substantialist approaches tend to do.Footnote 91 In this tradition, peripheral actors conform to the control and exclusion prerogatives of core actors when they are structurally dependent on them. Alignment behaviour is explained as a structural dependency in the relational sense, formed either because a peripheral actor has sparse inter-peripheral ties and its closest and most frequent interactions are primarily with a core actor, or there is a dearth of alternative core actors.Footnote 92 A relational network structured in this way prods peripheral actors towards alignment with core actor preferences in multiple ways. This may be because the peripheral actor is locked in to an asymmetric pattern of exchange that reproduces (symbolically or materially) a core actor's centrality to the network, because the peripheral actor relies on the core actor to bridge its relations with other peripheral actors, or because the peripheral actor lacks the adequate ‘stuff’ (information or resources, whether symbolic or material) to coordinate collective action among actors on the periphery.Footnote 93 Conversely, peripheral actors possess greater optionality and can more easily mobilise against core actor control when inter-peripheral ties are dense, plausible alternative core actors exist, or a core actor is unable to exploit its structural position to its advantage.Footnote 94

In contemporary relations with the numerous smaller states on its periphery, China has established control and exclusion ‘partnerships’ that leverage its economic centrality to them by deliberately linking trade, investment, and aid with political and security cooperation.Footnote 95 Through heterogeneous contractingFootnote 96 – an approach made possible by China's network position – it has created a series of partnership agreements that grant China terms of control and exclusion, leveraging what it calls ‘strategic comprehensive partnerships’ to ‘shape a more favourable political environment for China’.Footnote 97 Especially with smaller neighbours who are structurally dependent on Chinese economic ties – including Mongolia, Uzbekistan, Tajikistan, and Kyrgyzstan – China's partnerships result in varying amounts of control over these states’ domestic institutions.Footnote 98 At the same time, and far from the Western concept of ‘most favoured nation’ trading status, China uses the partnership mechanism with these states and others to establish exclusionary privileges in relation to third parties. Terms of exclusion that China secures from peripheral states through these partnerships include: foreswearing military and political alliances with third parties that might be turned against China; securing exclusive access to certain areas of peripheral territory for Chinese-only gas pipelines and other projects; and preventing third parties from using the peripheral state's territory against China.Footnote 99

When spheres of influence take the form of network centrality, third-party exclusion from the terms of core-periphery relations depends on position relative to the core actor. As with questions of control, questions of exclusion are agnostic about actor motivations in favour of explaining the opportunities and constraints that derive from an actor's place in a network. And as with control, the mechanism of exclusion in a relational approach has to do with how and where an actor is embedded in a web of patterned interactions among actors. A third party has relatively few opportunities to challenge or disrupt a core-periphery relational structure if it is an out-of-network actor. Regional security complex theory, for instance, supposes that the ability to influence patterns of amity and enmity among actors depends on being part of the same region; distant actors lack opportunities to influence how and whether geographically proximate actors undertake processes of competition and cooperation.Footnote 100

A third party's interaction – or lack thereof – with a network of actors in which only one exhibits high degree centrality is therefore likely to simply reify core-periphery dependencies between other network actors except under two conditions. One is that the third party becomes an alternative hub or core actor, which grants peripheral actors an option that potentially alleviates dependency on the original core actor. The second way a third party can disrupt a core-periphery arrangement is by strengthening inter-peripheral ties, which rearranges the structure of the network in a way that makes collective mobilisation easier. In the above example of China's relations with weak states on its periphery, third parties like the United States have relatively few opportunities to influence the holistic core-periphery control and exclusion that China has established unless they are able to either supplant the economic role China plays in these peripheral economies or integrate peripheral states into a collective resistance or bargaining arrangement.

Spheres of influence within international hierarchies

This article's focus on spheres of influence addresses a lacuna in the study of hierarchical international relations. Despite being a common part of not only world history but also contemporary international politics, too few scholars have attempted to bring conceptual rigour to this phenomenon and too many have either taken it for granted or failed to take it seriously. This article has shown that different theoretical traditions take, as a starting point, different assumptions about the basic properties of spheres of influence – understood as one polity asserting some form of control over another to the exclusion of third parties. The scope of control implicitly involves third-party relations, but can also be much more expansive. Control and exclusion can be viewed as broad mechanisms that produce one specific kind of unequal relations that we may call ‘spheres of influence’. Yet why and how those mechanisms are exercised – which different theories account for in different ways – affects our expectations of the production, reinforcement of, and departure from any particularised sphere of influence arrangement. Accordingly, the most direct payoff from this article has been tracing how different theoretical assumptions furnish different causal logics of control and exclusion, providing a common referent for a theoretically diverse research agenda that understands spheres of influence as merely one type of international hierarchy. We can ‘cash out’ the idea of spheres of influence differently depending on how we think about practices of control and exclusion.

But this step of conceptual clarification also says something meaningful about the study and practice of unequal international relations. The hierarchy literature is replete with particularistic characterisations of specific historical hierarchies,Footnote 101 as well as general theoretical statements about the logic and hierarchical nature of international relations.Footnote 102 Admittedly, some scholars have engaged in middle-range theorising about hierarchies,Footnote 103 but the emphasis in the literature is not on specifying mechanisms of unequal relations. What practices are involved (or not involved) in producing various international hierarchies? Here the literature has had little to say. Foregrounding spheres of influence and how they function helps remedy that. A sphere of influence – regardless how its practices are conceptualised – accounts for at least two dimensions of hierarchy, between the subordinated and superordinated, and the quiescence or resistance of third parties to that hierarchy. Spheres of influence do not represent a hierarchical form distinct from hegemonies, empires, alliances, and other forms of unequal relations. But those ideal-type hierarchies – about which much has been written – may or may not be double-coded as also constituting a sphere of influence. As such, whether we should recognise a sphere of influence in an unequal relation depends on more than mere asymmetry; it depends on whether practices of control and exclusion are found within or reify the hierarchical structure.

For example, the US bilateral ‘hub-and-spokes’ system in Asia is a series of formal, and consensual, alliances, yet during the Cold War, it was also a distinctly American sphere of influence: The United States exercised explicit mechanisms of control over its clients’ foreign policy decisions that precluded communist encroachment, literally circumscribing the sovereignty of Japan, South Korea, and others. Add to this the diffuse cultural hegemonic control over clients as practised through the US-led ‘liberal international order’, and what you had were client states in Asia that for decades were firmly entrenched in their alignment with the United States because exclusionary control existed in more than one way. Since the end of the Cold War, however, we cannot seriously think of America's Asian allies as constituting an American sphere of influence. Even the most stalwart US allies make their own national security decisions and pursue foreign relations with countries like China and North Korea in a manner that all but proves the United States no longer exercises the same kind of influence over its allies’ foreign policies as it did during the Cold War. The cultural hegemonic context of the ‘liberal international order’, moreover, may have reinforced US centrality in the past, but that same project today faces resistance internationally and from some quarters within the United States.

There is a practical dimension to this conceptual analysis too. Understanding what spheres of influence are can help us navigate international politics by, for instance, distinguishing when accusations of moral equivalency in international politics are valid or unfounded. Criticisms of US foreign policy as masking an ‘American empire’ rarely, if ever, mean ‘empire’ in the narrow ideal-typical sense of governance through the use of local intermediaries and heterogeneous contracting;Footnote 104 more precisely, such principled derision is typically targeting US sphere-of-influence practices. And by that standard, the criticism fits some aspects of US foreign relations better than others. Whereas US alliances in Europe or Asia are these days consensual and non-exclusive, the United States does still exercise exclusionary control over Puerto Rico and its territorial holdings in the Pacific.

Similarly, a rigorous sphere-of-influence concept can help us detect hypocrisy when policymakers in any government resort to doublespeak about their foreign policies. Whether Chinese rhetoric about ‘win-win’ and harmonious relations with others or America's ‘free and open Indo-Pacific’, clarity about the assumptions and reasoning animating spheres of influence in its various forms provides a standard by which to look beyond cheap talk and assess how hierarchy is actually pursued and contested. Chinese rhetoric may emphasise ‘win-win’ harmonious relations and Xi Jinping himself has explicitly denied pursuing a sphere of influence in the Asia-Pacific.Footnote 105 But should we put stock in his denial? Scholars and policymakers have observed a pattern of China pursuing and exploiting network centrality in relations with states on its periphery.Footnote 106 They observe China using the United Front and economic penetration to circumscribe the foreign policy choices of non-Chinese societies.Footnote 107 And they observe China's military casting an exclusionary geopolitical shadow over contested territories that it then occupies itself, like parts of the South China Sea.Footnote 108 In all such cases, we can accurately label Chinese foreign policy as attempting to exercise – whether deliberately or not – a sphere of influence, even though the practices of exclusionary control manifest differently in different settings. And acknowledging as much does not itself tell us what type of hierarchical regional order China seeks, since exclusionary control can be found in all manner of unequal structures.

Perhaps most importantly, greater conscientiousness about how control and exclusion occurs in hierarchical relationships provides a basis for strategies aimed at either countering or solidifying spheres of influence. As a prima fascia observation, we might say that the more ways in which control and exclusion occur in a given hierarchical relationship, the harder it will be to dislodge or successfully contest. In this way, calling a thing by its right name is crucial, for it is the starting point for not just theory development, but strategy and policy design as well.

Van Jackson (PhD) is a Senior Lecturer in International Relations at Victoria University of Wellington, a Global Fellow with the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars in Washington, DC, and the Defence and Strategy Fellow at the Centre for Strategic Studies in Wellington, New Zealand. He was previously a Council on Foreign Relations International Affairs Fellow.