Introduction

The shape of power is always the same: it is the shape of a tree. Root to tip, central trunk branching and re-branching, spreading wider in ever-thinner, searching fingers. The shape of power is the outline of a living thing outward, sending its fine tendrils a little further, and a little further yet.Footnote 1

These are the opening of lines of Naomi Alderman's novel The Power. The power Alderman writes about is an electric force that women and girls are gifted with. They sense it and can learn to use it when it is ‘awakened’ in them. Her novel is a feminist dystopian depiction of what happens when the power spreads and eventually destroys society. Alderman's novel combines ‘elegantly efficient prose with beautiful meditations on the metaphysics of power, possibility and change’.Footnote 2 The matter of concern here is that Alderman's depiction of power and her related meditations appear disturbingly salient also for power, possibility, and change in security/military matters.Footnote 3 Security/military matters, just as the power, are ‘spreading wider’ and ‘straining outward’ ‘a little further, and a little further yet’. They are, as the power, working through an organic within, not that of a tree but that of affective capitalism. And just as the power, their spread (therefore) becomes ‘sticky’. Writing about the spread of security/military matters is a way of engaging the question of how, unlike the power in Alderman's dystopia, they might be prevented from thoroughly militarising society and ultimately destroying it. As neopopulists, neoauthoritarians, and neoliberals are converging in ever more innovative and imaginative neo-neo-neoconstellations where military/security matters figure centrally, such engagement appears particularly salient.

This article attempts such an engagement by focusing on spreading security/military matters at work in the advertising of tracking devices. Much of this advertising plays with sensemaking, working from the inside and negotiating opaque co-presences. In so doing it is generating a form of militarisation in depth. The advertising anchors the preoccupation with security/military matters deeper rather than diffusing them more broadly, and it does so particularly effectively given that we are prone to misrecognise, underestimate, and therefore to be ineffective when intervening with these developments. An overarching reason is the difficulty of observing processes that merge commercial and security/military logics.Footnote 4 Moreover, much advertising defines the tracking devices and their politics in a manner that diverges from (or is opposed to) common tropes about the politics of security technologies. Affective sensemaking and resonance contrast with technical, strategic calculation. Work from the proximate, enmeshed, embodied, inside contrasts with governance at a distance. Situated, adaptable, specific, and indeed opaque co-presences contrast with the fetishisation of transparency. These contrasts do not make the more common tropes irrelevant or false, nor do they eliminate the connections between the two sides of the contrasts. However, they do highlight the import of recognising that things are different, more contradictory, and potentially unstable than they are often made out to be. They also show the import of paying careful attention to objects and their entanglements and of refusing the theoretical blinders that do away with mess, paradoxes, and uncertainties, as well as the political opportunities these can open. Thinking with and through compositions is a way of doing this.

To advance this argument, the first section clarifies the status, form, and method of tracing the security compositions made in the advertising of tracking devices. The following sections lay out the argument that the advertising of tracking devices defines these as playing with the senses, working from the inside and negotiating opaque co-presences, and therefore composing a security where resonance rather than reason, proximity rather than distance, and opacity rather than transparency are central. In the conclusion I return to the question of how to engage the ‘sticky’ politics of the security collage that emerges from these processes.

Tracing the security compositions of tracking device advertising

Before describing the security composing at work in tracking advertising, it may be important to step back and reflect on the scope, logic, and form of tracing I employ here: what is the reason for engaging in such a description and what can/does it (or not) claim and how?Footnote 5 I therefore begin by underlining the import of including the advertising of things in our reflections on security compositions, both because security – as other ‘values and meaning’ in ‘brand society’Footnote 6 – is enacted through advertising and because these things, such as tracking devices, are integral to composing security itself. Second, I advocate for an approach to the composing of security that insists on the combinatorial, accidental, and emerging qualities of compositions – their ‘mess’, ‘partial connections’, and ‘emergence’Footnote 7 – which make up their collage-like qualities. Finally, I make the case that ‘collaborationist’ research strategies, which involve making ‘oddkin’Footnote 8 with the researched, as well as with non-academic genres – such as Alderman's novel and a series of collages by Alg that I rely on below – are helpful (possibly even necessary) to engage collage-like composing.

Advertising tracking devices/composing security

In this Special Issue, we focus on how security is composed. As Jonathan Luke Austin's introduction to this issue makes clear, thinking in terms of compositions is helpful precisely because it directs attention to the wide and heterogeneous variety of socio-material practices that make up security.Footnote 9 At the centre of my contribution is the role of advertising and more specifically of the advertising of tracking devices in this composing.

To begin with the place of advertising, security and military matters are increasingly governed in commercial ways. This is not only (or even mainly) because companies and markets play an increasingly central role in all contexts although they obviously do. It is also because contemporary forms of security management in the public rely heavily on (quasi-) market mechanisms for governance. The merging of bureaucracy and neoliberalism is also spawning forms of ‘neoliberal bureaucratization’Footnote 10 in security politics and practice. The story of this development and its many contextual variations is now so well established that there is no reason to repeat it here. However, it may be important to underline that markets are therefore bolstered (not shrunk) by the current ‘return of the public’ to conventional military/security.Footnote 11 A consequence of that is to make commercial ways of doing and communicating about security/military matters (and this includes advertising) central for all involved; not only for companies and market actors. Trade fairs and professional conventions – such as the SCTXFootnote 12 or ASIS EuropeFootnote 13 – in which the fieldwork for this article was carried out – epitomise this trend. The size, numbers, and kinds of security/military fairs are growing apace with the centrality of markets. In these fairs public military, policing. and intelligence institutions have stands next to universities, research institutions, nongovernmental organisations, and companies ranging from highly specialised intelligence companies to travel agencies. As Theodore Baird argues, they have come to play a crucial role in the production of practical knowledge for security professionals in the current privatised environment, and hence function as an ‘extension, reassertion, reaffirmation, and transformation’ of securitised space.Footnote 14

The specifically commercial aspect of this knowledge formation has implications for the composing of security. Advertising (of tracking devices, for example) is no longer a marginal phenomenon that influences how security is made from the fringes. It is pervasively present at its core, or perhaps a better way of saying this is that the core is distributed in many decentralised market processes. Trends in contemporary advertising therefore matter also for security. Most centrally, as will be discussed extensively below, advertising in security has become increasingly prone to enrolling consumers/clients in practices of co-creation, co-production, or prod-using. Moreover, as elsewhere in security advertising, there has been trend to do this by engaging sensemaking ever more deeply: as Nigel Thrift puts it, ‘the strategy has been to think of commodities as “resonating” in many sensory registers at once, increasing the commodity's stickiness (or at least making it more recognizable in the commodity cacophony of contemporary capitalism)’.Footnote 15 Clearly, ‘Lifeworld Inc.’ and ‘Brand Publics’ occupy a growing space in composing commodities that tend to become ever more sticky.Footnote 16 Exploring these trends in the context of security advertising is a core ambition of this article.

Focusing on the advertising of tracking devices specifically is a way to make this feasible. It is also a way of contributing to the debate about a practically important and rapidly evolving (security) technology.Footnote 17 However, it is also more than this. Analytically, it is a way of turning this enquiry into one focused on what composing security means. Tracking devices are objects. They are connected to advertising in a manner analogous to the one connecting bodies and discourses about bodies that matter.Footnote 18 Advertising is making up tracking devices within the confines of the tracking devices it makes up. Therefore, there is a limited range of tracking technologies, based on sensors that ‘track’ (hence the terminology), for example, location, speed, temperature, sounds, images, heartbeat, or chemicals and an equally limited number of devices, applications (apps), and programmes used to analyse and observe the result. However, it would make no more sense to provide a list like overview of what tracking devices are than it would to provide a list like overview of what the bodies attached to discourses about bodies that matter are. The overview dissolves under observation. Advertising – just as the discourse about bodies that matter – (re)defines both the tracking devices and their relationship to contexts and to the consumer-clients targeted by advertising. Expounding how is a core substantial contribution of the account below.

Composition as collage

The focus on the advertising of tracking devices and therefore on the ways in which commercial, dispersed, socio-, affective, processes are composing security has implications for what the composition is as well as for the meaning and political significance of the composing. It lends the composition a collage-like character.

Advertising is ultimately open-ended. It has no end or final form. New sellers, products, and ideas contribute to advertising in continuous transformation. One might liken it, as a marketing textbook does, to a perpetual ‘sign war’.Footnote 19 It therefore defies the common image of the (artistic, literary, political, etc.) composition as a stabilised, more or less orderly whole, composed through a process following law-like regularities. While such an image is precisely what compositional approaches intend to distance themselves from, it paradoxically continues to linger in them. Gilles Deleuze, for example, explains his interest in Spinoza by underlining that ‘what interested me most … wasn't his Substance, but the composition of finite modes’Footnote 20 and insists throughout the volume that Spinozean composition captures how ‘relations combine according to eternal laws’.Footnote 21 Even though he and Guattari contrast what they feel are legitimate compositions that ‘enhance open-endedness, non-restrictive, nomadic and polyvocal forms of synthesis and connection, open to fullest expression of enhancement of capacities … with [illegitimate] exclusive, restrictive, and segregated ones’, they still think of both types as wholes.Footnote 22 Not surprisingly therefore, in his rendering of Deleuzian thought Manuel DeLanda stresses that ‘assemblage theory is not conceptual but causal, concerned with the actual mechanisms operating at a given spatial scale’.Footnote 23 And Sophie Day and Celia Lury, who have worked with compositional ideas in the context of technologies of sensing and observing, insist on thinking about ‘assemblages as wholes’.Footnote 24

It is consequently justified to ask, with John Law and Annemarie Mol, for more ‘sensitivity to the possibility that social relations don't add up or hang together as a whole’, and to the realisation that this ‘leads us to the logic – the multiple logic – of the patchwork, in which we move from one place to another, looking for local connections, without the expectation of patterns “as a whole”’. As they underline we must ‘ask about the possibility that there are partial connections. Partial and varied connections between sites, situations, and stories.’Footnote 25 Still more compellingly, it may be useful to replace the idea of a ‘patchwork’ with that of a collage. The collage retains the emphasis on the patching together of what is there and of the political import, openness, and fragility of the seams connecting the patching. However, it more strongly emphasises the variable nature of the patches (it is not only about variations of cloth) as well as of the possible techniques involved in composing (it is not only sewing). More than this, as Max Ernst argued, cultivating this variety is a heuristic device in its own right. Clarifying the centrality of collage for his work, he writes ‘I found figural elements united there that stood so far apart from each other that the absurdity of this accumulation caused a sudden intensification of my visionary facilities and brought about a hallucinating succession of contradictory images.’Footnote 26 Law may have reached similar conclusions as a collage opens his book about the relationship between methods and ‘mess’ in the social sciences.Footnote 27 Be this as it may, drawing the analogy to the collage is helpful for retaining attention to the varied and unstable composing/compositions of security through the advertising of tracking devices.

Collaborationist strategies

Multifarious and unstable collage-like compositions by definition elude research strategies following cookbook recipes indicating the precise doses of what should be studied and how the resulting dish should therefore look. Rather, to engage collage-like compositions requires a ‘collaborationist’ strategy that not only allows but also ‘requires the making of oddkin: that is we require unexpected collaborations and combinations, in hot compost piles. We become-with each other or not at all. That kind of semiotics is always situated, someplace and not noplace, entangled and worldly.’Footnote 28 Here I engage in this kind of collaborationist strategy in two directions.

The first is in the direction of the people and objects involved in the composing of the security collages I focus on. Visiting them ‘politely’, remaining ‘curious’ about what they have to say and providing them with the opportunity not only to speak back, but also to shape the security compositions was not optional.Footnote 29 It was a necessary protection against the grand theories and analytical frameworks that risk wiping out the heterogeneity of social and security compositions. Collaboration is necessary to allow the ‘subject- and object-making dance’ in which ‘the choreographer is a trickster’ rewriting the stories.Footnote 30 It is a form of collective writing of ‘apotropaic text’.Footnote 31 It therefore necessarily begins from below, from the mundane, to conceptualise the significance of the nitty-gritty details of how tracking devices are advertised.Footnote 32 This necessarily results in ‘descriptive’ accounts, as collaboration with the observed presupposes that they are given space. Obviously, the resulting accounts cannot be empirically representative or generalisable. What they can offer is a grasp of the specific security composing (through the advertising of tracking devices in this case) that may serve as inspiration for empirical and conceptual work on security compositions more generally. Since a good grip on something limited may be preferable to the damaging delusions generated by empty generalisations,Footnote 33 there is perhaps little need to regret the situated and descriptive accounts of collaborationist research.

Secondly, I extend collaboration to other genres, such as painting, literature, film, poetry, or for that matter science and mathematics, inviting communication. Donna Haraway is a persistent and clear advocate for this kind of collaboration. In the poem shes uses to open, a volume where ‘the paintings of Lynn Randolph introduce and frame themes and arguments’, Haraway suggests that ‘making connections is itself a methodology /Articulating clusters of processes, subjects, objects, meanings, and commitments/ SF is a methodological proposal.’Footnote 34 Here, I gesture towards her ‘methodological proposal’ by collaborating with Alderman's The Power, with which I opened the article, and by allowing the collage series by the Berlin-based artist Alg to introduce and frame the core themes of the argument.Footnote 35

But why these collaborations rather than others? The answer here and more generally is pragmatic and related to what the collaborations bring. Do they provide the connections to other contexts Haraway insists on in her poem? And in so doing can they help locate and put the researched into perspective, in my case situate the pertinence of the security compositions in advertising? Second and along similar lines, can the alliances work as a corrective on the inevitable positionality of the researcher? Can they be reflections on similar phenomena from someone else's perspective that highlight, and perhaps also relativise, the positionality of the observer? If so, they are a welcome alternative to strategies for dealing with positionality. They dispense with the scientific (and authoritarian) pretentions of the sociological ‘objectifying the objectifying subject’Footnote 36 and with the shallow, often narcissistic, exhibitionism of constantly ‘situating the author in the text’.Footnote 37 Collaborating with Alg's collages and Alderman's The Power has been central to the research here on both accounts: establishing connections and dealing with positionality.

So far I have suggested that reflecting on how the advertising of things composes security is of crucial import to contemporary security politics, that to do so we need to accept the collage character of advertising compositions and adopt collaborationist research strategies. I have elaborated on and justified these arguments. I have done this in the positive, pointing to the scholarship I ally (or collaborate) with. This is not to suggest there are no diverging points of view. The scarcity of work along the lines suggested here shows the opposite. The discussions around these issues will continue. But it is important also to leave space for the argument about how the advertising of tracking devices is composing an unlikely security collage. Three of its aspects – its emphasis on sensemaking, on insides and on opacity – appear particularly salient. Acknowledging them is a heuristic device both for tilting the compositional approach towards tending to affect and resonanceFootnote 38 and for redirecting engagements with the politics of commercial security technologies. They therefore structure the account to follow.

Playing with the senses

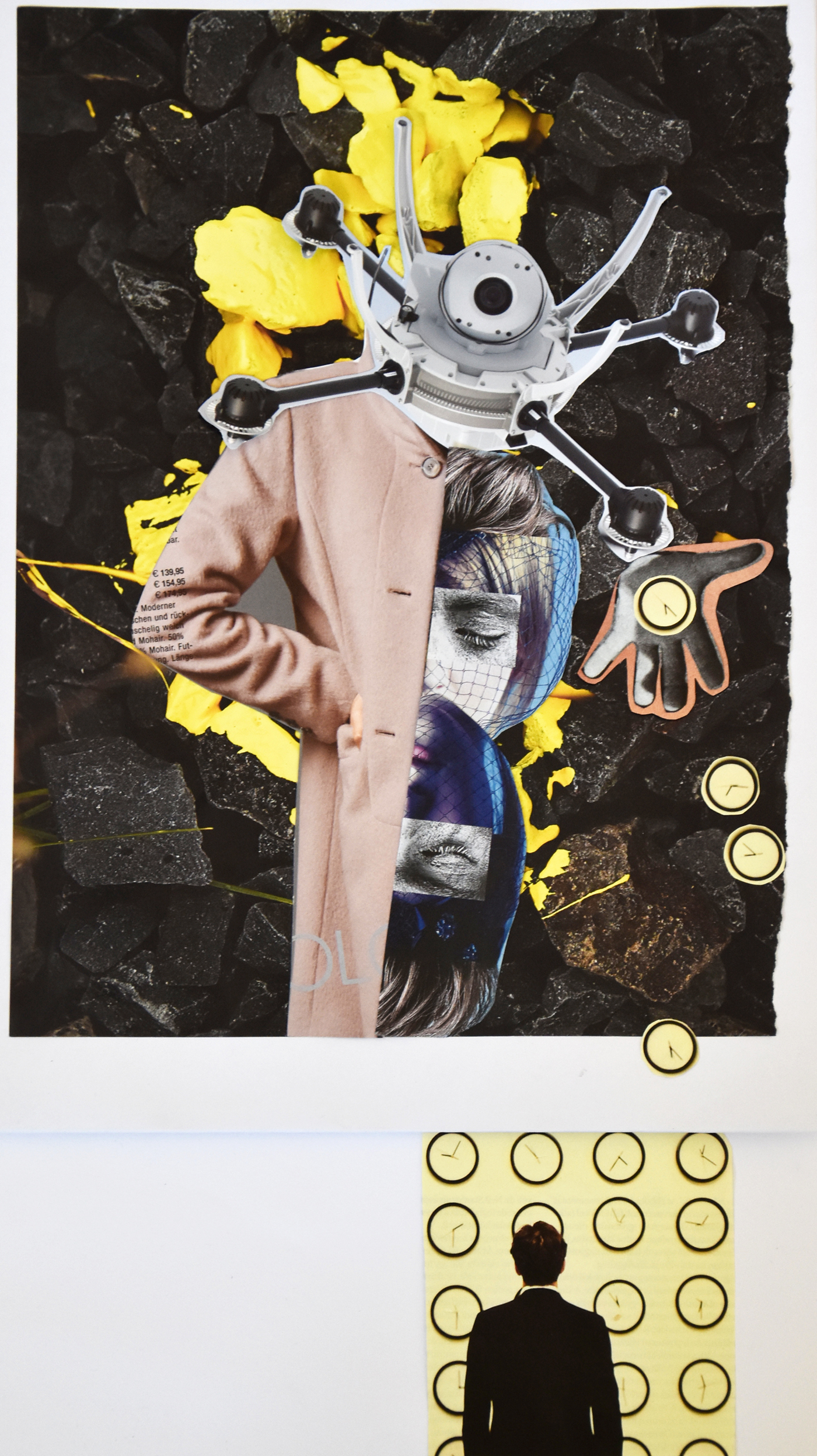

The advertising of tracking devices in security fairs could be expected to reinforce technical, calculative, and strategic forms of security. Not only does much conventional analysis of security technologies focus on their strategic usages,Footnote 39 but critical research has also tended to explore how technologies turn security into an impersonal, technocratic matter for professionals and security bureaucracies to deal with on the basis of ever growing datasets that enlarge the space of indicators, little data analytics and algorithms in the composing of security.Footnote 40 While the advertising of tracking devices does indeed contribute to this kind technical, bureaucratic/strategic and calculative security composing, paying close attention also shows it doing something very different. Like Alg's collage aesthetically implies, security advertising practices are Playing with the Senses (Figure 1). The advertising was composing security by emphasising the import of imagining and embodying it, as well as by connecting it to an understanding of the security profession, where precisely these two forms of sensemaking figure centrally.

Figure 1. Playing the Senses, collage by Alg, Berlin, 2018.

Imagining

An unlikely illustration of the central role imagination plays in the advertising of tracking devices is found in the stand of a small start-up founded by intelligence professionals from a public intelligence service at the SCTX 2018.Footnote 41 A range of rather conventional-looking location tracking devices was on display. The company representatives introduced them by explaining the different location systems the devices were using. They distinguished them from other similar devices by insisting that theirs were more difficult to discover because of the way their signals were encrypted. Moreover, if these tracking devices were discovered they would be impossible to trace back, should anyone try. The devices looked so similar to those commonly used by all kinds of criminal organisations, the representatives insisted, that to most it would probably not seem worthwhile doing so. The very ordinary aspect of the devices was essential to obscuring their origin and technical superiority. The representative also took care to explain that the main clients were intelligence agencies. With this, he was highlighting professionalism and dissipating any suspicion that the start-up's devices were as unsophisticated as they looked.

These conventional and entirely predictable ways of advertising the tracking devices contrasted starkly with the visual references. The screens around the (relatively small) booth were covered by an abstract grid, network, or system pattern in white on a dark blue background. It was a background referencing the common iconography of cyberspace. On one of these screens three images were projected in succession. The first showed a line of people walking across snow with a text reading ‘Tracking: Where is it?’ The next displayed a pipeline asking ‘Sensing: What's happening?’ The last was a world map with lightened spots and the question ‘Analysis: What can we do about it?’ These images seek to enrol viewers and visitors, appealing to their imagination. They ask open questions, suggesting that the tracking devices may help provide the answers. They leave it up the viewers to imagine how. More compellingly, they want the visitor to get involved in the work of imagining how the tracking devices might be used. No references to technical details or factual information interrupt this appeal to the imagination of the viewers. It is up to you to settle, or perhaps more appropriately sense, what you are seeing. The images are not communicating through what they show but through what we as viewers see in them. Ce que nous voyons. Ce qui nous regarde, Georges Didi-Hubermann writes.Footnote 42

Even advertising of the most conventional tracking device – a location tracking device – is tilted towards sensemaking through imagination. The point is not that is should surprise us. On the contrary, imagination and intuition have a long pedigree in military/strategic thinking.Footnote 43 Open questions, pieces of a puzzle, abstract images and photos encouraging the viewer to supply content, are a staple fare in security advertising.Footnote 44 Both dovetail well with general trends geared towards ‘activating consumer ingenuity’.Footnote 45 Rather, the point is to underline that such sensemaking through imagination sits at the core of advertising and that we therefore need to account for it when considering the composing of security.

Embodying

Sensemaking and resonance – rather than strategy and reason – are at the centre of tracking device advertising in a second manner: through the emphasis placed on the potential of ‘embodying’ tracking technologies/practices. The affordances of sensors, and particularly the development of bio-sensing technologies, are at the origin of this strand of advertising.Footnote 46 Cameras can be used to stream what someone is seeing. Sound recordings can be added to track what a person is hearing. Heat sensors can be used to feel their environment. Measurement of pulse heartbeat and calories burnt is available through the technologies underlying fitness watches. Sensors measuring the presence of specific minerals can provide an idea of what a person tastes or smells. Tracking is thus no longer only (or even mainly) tracing tracks in the snow. Rather, it is advertised as involving what these people are seeing, hearing, and feeling, if they are cold or warm, exited or relaxed, afraid or calm, hungry or thirsty. Tracking technology is now drawing and feeding security data into ‘a data eating/data emitting body’.Footnote 47 Tracking has become embodied; connected directly to bodily senses and embodied experience. It is contributing to what Linda Åhäll calls the ‘dance of militarization’.Footnote 48

The advertising in question here makes this connection insisting on the potential of embodying tracking, embedding the tracking inside the body. For most companies integrating biological sensors is an aspiration. They are ‘not quite there yet’, their ‘projects are underway’, and they are ‘developing new solutions’. Even companies that have integrated a variety of sensors tell a story about a potential future. A case in point is Audax®, whose account of ‘How we've evolved points towards possible future integrations’ (Figure 2). Audax®, as the global pioneers of Body Worn video cameras for evidential use, have subsequently added live tracking biometric information in their development of the Bio-Ax® All in One System. When the company representative introduced the product s/he indicated the graphic in their brochure (Figure 2) explaining that the ambition is to potentially add further biometric sensors and information streams in the future.Footnote 49

Figure 2. Audax®, advertising booklet, 2018.

Similarly, elsewhere, a representative of an analytics company explained that their company excels in combining and analysing information from a range of different kinds of sensors. When asked how much work of this kind they do, s/he answers ‘We develop the packages with our customers … Most clients want something rather more simple.’Footnote 50

The potential of embodying tracking that the advertising focuses on contributes to a specific composing of security. Even if the real existing tracking devices and related analytical services cannot (yet) penetrate the body, the advertising inscribes embodiment as an important aspiration, implying that security would be enhanced if indeed it could be grasped through the bodily senses. It is adding embodied sensemaking to the composing of security.

Connecting

Lastly, the advertising of tracking devices is composing a security by connecting to the common sense of security professionals. It is reiterating, reinforcing, and therefore also reinscribing a tradition of seeing professionalism in security as a practical craft. Among security professionals the significance of practical common sense continues to be pervasive. It infuses the professional culture, institution, and language so strongly that researchers inside the institutions, including Carol Cohn, describe how they are themselves transformed by it.Footnote 51 The precise nature and contours of this common sense are obviously contested, as articulated in the debates such as those surrounding the place of racial/ethnic minorities,Footnote 52 the inclusion of women,Footnote 53 the acceptance of homosexuality,Footnote 54 or the valorisation of managerial skills and governance forms.Footnote 55 However, the emphasis on practical common sense has in no way vanished from the commercialised and technologised contemporary security profession. It is omnipresent and perhaps surprisingly often connected in the advertising of tracking devices.

A striking case in point is the advertising of 6ecurity at the SCTX.Footnote 56 6ecurity is a UK/Belgian company. It offers a panoply of conventional security services including guarding, intelligence/forensics, and training. As staff at the stand explained, it has contracts across the world as well as a range of exclusive security training contracts for the Belgian police and armed forces. They also insist that they use the ‘latest technologies’ in their work, including of course various tracking technologies. Interestingly, at SCTX, the (spacious) booth is dominated by a large poster that reads, ‘EDUCATION OF THE SENSES’. When asked what this refers to, the four people in the stand concur that, ‘actually, as a security officer the most important thing’ is to have ‘an intuition for what goes on’. ‘To see what has not yet happened.’ ‘If I work somewhere, I have to be able to sense what is around the corner.’ The company advertising brochure draws similar connections. Its ‘education of the senses program’ can be customised to need and it promises to train and coach ‘your eyes’ as well as a range of skills including ‘awareness’ (Figure 3). When I ask how the emphasis on the senses links to the tracking technologies they just talked about, they answer that they reinforce each other. The one cannot work without the other. The advertising message is clear: professional security is a craft that can be reinforced and bettered if connected to tracking devices.

Figure 3. 6ecurity, ‘Education of the Senses’, advertising booklet, 2018. See also company website, available at: {http://6ecurity.com/} accessed 18 June 2019.

In a somewhat paradoxical fashion, the advertising of tracking devices based on technologies so advanced that they are still being developed, is reinstating the most conventional way of thinking about how security is provided and what competence in the security profession therefore entails. It draws this connection into its composing of security. By playing with the senses, the advertising of tracking devices is composing a non-strategic, non-rational, and non-logocentric form of security; a security where the experienced, affective and commonsensical is decisive.

Working from the inside

The second aspect of tracking device advertising I wish to direct attention to – its emphasis on tracking devices working from the inside – may also stand out as unexpected. Security technologies are usually associated with a politics of ‘governing at a distance’ and/or ‘vertically’.Footnote 57 Grégoire Chamayou makes the problematic ethics of ‘killing from a distance’ a centrepiece in his discussion of drones,Footnote 58 and Mark Duffield suggests that humanitarians ‘replace face-to-face engagement on the ground in favour of techniques of distant sensing and remote management’.Footnote 59 In these accounts security technology works from the remote outside on people and things distinct and separate from them. However, much advertising of tracking devices construes the situation in rather different terms. It promises a security working from within in a manner that makes distance, verticality, and remoteness less significant if not plainly irrelevant. There is a side of the security collage that features neither a ‘here and elsewhere’ pace Shapiro, nor a notion that technologies bring us ‘closer to the distant making stranger of the near’ pace Viriolo.Footnote 60 I will exemplify this by showing how the advertising morphs tracking devices into subjects, moves them inside crowds, and merges them into spaces.

Morphing with subjects

As in Alg's collage Penetrating Control (Figure 4), in advertising, tracking devices morph with the security subject and work from its insides. Quite predictably perhaps: how could a security technology working through the senses work otherwise than from within? An ASIS Europe 2016 presentation of an advertising app for corporate travellers made the point.Footnote 61 The presenter constructed an imaginary scenario: an attack on the hotel where a client was staying. The client was taken hostage and held with many other people in a room. The presenter then proceeded to focus on how helpful the app would be in such a scenario. It would supply information about precise location and temperature. But more centrally, the app would stream video recordings seeing and hearing ‘with the asset’ and it would be connected to the sensors recording the movements, pulse, and blood pressure of the hostage. The app, in other words, would work not only from inside a room, but from inside a sensemaking subject. As the presenter explained, through this sensemaking the app would provide an understanding of the situation generally but also of the hostage. Was s/he beaten, under threat, lying, scared, or on the contrary relatively relaxed? The app would know the answer and provide an ‘insider understanding’ of the situation. It would make security professionals ‘part of the events’.Footnote 62

Figure 4. Penetrating Control, collage by Alg, Berlin, 2018.

The centrality of moving inside and morphing with the subject was highlighted and helped by the language of the presentation. The presenter was constantly sliding between ‘person’ and ‘asset’. Leaving out, not mentioning, or using euphemisms for the security subject makes it possible for advertisers to move around the contentiousness of working from the inside. It is less disturbing to be inside an ‘asset’ than a person or a client. The language distracts from the malaise. It does so all the more effectively when to the audience these slides are part of a professional language. In security language an ‘asset’ is a standard term used to designate the protected, whether persons, products, information, movements, buildings, spaces, or other things. As the welcome page for the ASIS Europe 2018 convention in Rotterdam shows (Figure 5), its usage as an overarching category including people is perfectly normal. This does not diminish the significance of the work the term does to distract attention from the malaise surrounding security information accessed from the insides of people. It merely signals that the app presenter does not have to invent strategies to advertise in spite of it. The language and especially the use of the term ‘asset’ and its naturalising, neutralising, performative effects will do the work.

Figure 5. ASIS Europe 2018, welcome screen, accessed 1 April 2018.

The presentation is advertising the benefit of an app that works from the insides. Distance and remoteness are not denied. The security professional is in a banal sense on the outside. But this is not what the advertising draws attention to. Rather, it is the possibility of being inside in the strongest possible sense of becoming merged with the subject. The presentation composes a security where the insides of people are core. It is adding the insides of security subjects to the security collage of commercial advertising.

Moving inside crowds

Other insides than those of specific security subjects are part of the advertising of tracking devices, and reinforce their place in the way this advertising is composing security. For example, in the advertising of tracking technologies for crowd management purposes, much of the focus was also on the ways in which tracking technologies make it possible to be inside the crowd. Every company I visited in the ‘People Movement and Management Area’ was referencing tracking technologies in their advertising; mostly videos, but also thermal sensors. The representatives underlined a variety of ways in which the tracking mattered to them, including the possibilities of visualising crowd movements and the varying density of the crowds. In so doing they recurrently relied on formulations that in various ways indicated the import of tracking devices that not only place them within the crowd, but also give them a sense of moving with it. As a representative of Crowd Vision explained as we were watching a demo in the stand, it is essential to ‘stay with the crowd’, ‘to be with it real time’, ‘to move along with it’, and ‘never slide out’.

For this Crowd Vision representative, being inside the crowd and moving with it seemed to matter partly as a way to get a grasp of the crowd as a whole, to see its shape and contours. S/he kept making comparisons between crowds and flocks of bird, insisting that being inside was a way of knowing the density at specific points. However, s/he also talked about insider presence as disaggregating it into identifiable and observable individuals. By allowing the security professionals to move with the crowd, the tracking devices could help them locate ‘the needle in the haystack’; a major preoccupation for security professionals in airports, sports events, festivals, or border control posts. Companies with names such as Crowd Connected, Crowd Vision, or the Institute for Crowd Simulation were therefore working with advertising focusing on the identification of individuals using slogans such as ‘Right Person. Right Time. Right Place’ or ‘AI-powered person recognition’.

Advertising is holding up the promise that tracking devices will make it possible to be an insider moving with the crowd. It is laying the foundation for an ever deeper and ever more fine-grained understanding of the crowd both as a whole and as disaggregated into its constituent parts. In so doing, it is contributing to a specific composing of security, one where proximity, closeness, and presence are valued. It is diversifying and enlarging the place of the inside in the security collage.

Merging into spaces

A last example of how the advertising of tracking devices locates the inside at the core of composing security is the way it handles space. Even the advertising of tracking technologies obviously designed for observing from distance or above maintain this notion of the inside at their core. When Instro advertises its ‘ultra-long range surveillance and targeting device’ to be attached to ‘planes/drones or similar and used at high altitude’, it does so in a booth with displays of ground details. One of the displays reads ‘human targeting’. The representative points me to another one; a video showing a busy city street asking if I don't feel as if I was there, ‘in the midst of it’. However, the significance of the inside stands out most starkly in the advertising of tracking devices directly promising access to spaces otherwise closed or inscrutable.

Chronos Technologies is a case in point. The company offers a tracking device guaranteeing ‘indoor GPS coverage’. As the salesperson says, this matters because ‘GPS signals are lost when you are indoors, in a tunnel, in a basement or in a cave.’ Not only are standard devices therefore unable to track movements in these, but there is a lag in recovery when the signals again emerge. By using GPS repeaters ‘GPS signals can be kept live’ around the clock even when indoors or undercover for long periods of time. Along similar lines, the representative of a one-man drone operating company explains that the core advantage of the service s/he offers is that the drones can be mounted with ‘any kind of sensor’ and then used to ‘get into spaces’ without having to physically go there. S/he illustrates this by explaining how the drone can fly around a ship and be used to identify ‘anything; chemicals, arms, stowaways. You name it.’Footnote 63 S/he concludes by insisting that this gives an excellent understanding of what is inside the ship; one better than you would have if you were there ‘staring at stacked containers’.

More emphatically, much advertising promotes tracking devices as making it possible to become part of the insides and contribute to their making. For example, to convey the strong sense of insides the multiple sensors of a wearable camera could provide, the project manager of a company originally specialised in infrared fixed cameras pulled up images on her screen. They were the ones the camera s/he was wearing was producing about us in the trade fair as we were talking. Switching between the visualisations/videos of our conversation we could opt for, s/he pointed out that this insider understanding of one's own position could be drawn upon to redesign the space itself. S/he exemplified this both by drawing on the images of us in the SCTX space and with reference to how a prison might want to use the multiple layered view to rethink space in ways that could diminish dangers to guards. Although this project manager never employed the term ‘dynamic design”, s/he was in effect suggesting that the tracking technologies s/he was promoting could be used for that purpose. They could be used for a recasting of the space itself and of the space within it.

As they merge their tracking technologies into space, both the representatives of Chronos Technologies and the drone operator and camera company representative are locating insides centrally in their advertising. An analogously strong emphasis on insides is pervasive also in other areas of advertising as shown above. Advertising morphs tracking devices with the subjects and moves them into the crowds. Insides are pivotal in this advertising of tracking devices and the security it composes. These insides may be more potential than real. However, as Alderman reminds us, ‘the magic is the belief in magic’. It therefore does not matter if ‘all this is, is people with an insane idea’.Footnote 64 What does matter is the politics of this (possibly insane) insistence on a security working from the inside, not only penetrating but becoming part of and transforming subjects, crowds, and spaces.

Negotiating opaque co-presences

In the advertising of tracking devices, an issue occupying considerable space is how to make the tracking device acceptable to the tracked, that is, how to persuade them to allow the tracking devices to do their job, to accept their co-presence and indeed to care for them. The tracked take off, leave behind, and in various ways jam the wearable tracking devices. They mock, block, and mislead them. Their failure to take care of the updating and security of the programmes related to them results in data-transfers and analytical programmes being hacked, rendering the information patchy, imprecise, manipulated, and counterproductive. Considering the intrusiveness of the tracking devices discussed in the preceding sections, this is no more surprising than the presence in the advertising of suggestions for overcoming this. However, how the advertisers engage with these issues may be more unexpected. The precision associated with security technologies is no more present than are the accurate measurements and indicators connected to the management of the data they generate.Footnote 65 To ‘target precision’ as Maja Zehfuss would have it, or to ‘challenge transparent warfare’ as Jan Öberg suggests, therefore appear rather ineffectual if not irrelevant ways of engaging the politics of this advertising.Footnote 66 Instead, what the advertising does emphasise is murky, inside, co-presences – such as those shown in Alg's collage Managed Connections (Figure 6) – that add an element of opacity to the composing of security. I will show the centrality of this opacity in the disciplining, responsibilising, and recasting of the protected subject/asset advertisers resort to when striving to make intrusive tracking devices acceptable.

Figure 6. Managed Connections, collage by Alg, Berlin, 2018.

Disciplining

The trilogy discipline/responsibilise/recast echoes an idiosyncratic and selective reading of Foucauldian conceptualisations of the relationship between power technologies and the subject/self.Footnote 67 The first of these straightforwardly captures a conventional imposition from without. The reference to forms of such conventional disciplining occupies an important place in how advertising construes strategies for how tracking devices can be effectively inserted in practice. The interesting point about this disciplining is less that it is there (it obviously is) and more the centrality of opacity in it. Indeed, while transparency standards or the import of accuracy and precision may have a place as background assumptions about why tracking devices are significant and should be accepted, in the advertising – and hence in the way it is composing security – it is downplayed if not entirely absent. Instead, what the advertising is focused on are ways of imposing an amorphous and ill-defined co-presence.

A presentation focused on the Duty of Care is a good case in point.Footnote 68 The talk began with a historical overview based on court cases and regulatory developments, to make the point that the Duty of Care had evolved and was now applicable also in the security sphere. The presenter then outlined ideas about the implication of this. Enter the tracking devices. The presenter explained that the Duty of Care entailed a duty to provide the best possible care and this included drawing on the best available technologies. The slides accompanying this depicted a lower arm wearing six watches and another showing a male mannequin sending signals from a multiplicity of sensors placed on his body. The speaker urged the audience to realise the import of getting the tracking devices accepted because, if they were not, ‘no Duty of Care can be provided’. To support this point s/he used a generic slide: the red corseted torso of a woman, with black gloves holding a long whip and the text ‘Duty of Obedience’. It was followed by an equally generic slide featuring the metal clad hips a Roman Gladiator and accompanied by sexually charged remarks about the obviously restrictive implications of the tracking devices. The explicitly gendered references are to a (headless) disciplining and (headless) acceptance. References to the reasoned significance of transparency, of accuracy and of precision are left out of the picture, as are references to standards or regulations specifically developed to make these possible.

A similar opacity surrounding the nature and form of the co-presence also marked advertising suggesting the importance of disciplining users to accept tracking devices by falling back on hierarchies. Organisational hierarchies in particular were a recurring reference. ‘If the CSO [Central Security Officer] was linked directly to the CEO [Central Executive Officer] many of these problems would be solved’, as one advertiser put it.Footnote 69 The potential of standards/best-practices/regulations was also invoked suggesting that working with, accepting, and caring for tracking devices ‘could become something like the security drills … something everyone just does because it is in the rulebook’.Footnote 70 And for some advertisers, market authority and most notably insurance policies, were (or rather should be) central to disciplining strategies.Footnote 71 ‘If we could get the insurances to take the problem [of clients turning off their phones or not updating the app] seriously, it would be a clear step forward’ as an app promoter explained. If the insurance would refuse coverage when this happened, it would cease to be a problem.Footnote 72

In this advertising, the disciplining necessary to impose tracking devices is conceived in a manner that marginalises transparency. Advertising either remains silent about the import of transparency and the standards surrounding it, or displaces the argument to other ways of anchoring the disciplining effort such as those found in organisational hierarchies, rules and standards, or insurance policies. In so doing, it is adding an element of undefined opacity to the security collage it is composing.

Responsibilising

A similar pattern of distracting from the import of transparency and accuracy and instead cultivating a co-presence that is opaque is at work also in the way advertisers suggest gaining acceptance of intrusive tracking devices through forms of responsibilisation, that is through strategies geared at making users see it as their responsibility to ensure the co-presence of the tracking devices.

Advertisers of tracking devices will also connect the acceptance of the intrusive presence of tracking devices to a responsibility for broader security issues, leaving underspecified the nature of that link and the kind of presence that makes it possible. The representative of a company advertising services for shopping malls, airports, but also mega-events deplores the hostility with which the tracking technologies on which these services depend are met. I ask how s/he deals with these issues. The answer does not make the case for integrating the devices on the basis that this would ensure greater transparency or accuracy and therefore make the service better. Instead s/he places the weight on the moral responsibility of providing security for visitors, insisting that this responsibility ‘of course is not only a contractual obligation. It is far more fundamental.’ S/he then proceeds to explain in even broader terms that everyone has a responsibility for the ‘bigger picture’ and for terrorism and national security. S/he concludes emphatically that providing security is not ‘a job for one person or company. It is a duty for which everyone shares responsibility.’ Clearly, accepting the presence of tracking devices is integral to that responsibility, albeit for reasons that are left implicit.

An even more striking case in point is the way the representative of the Alaska-based company Chenega makes the case for an acceptance of the services it offers. The company, which offers a broad range of security services including guarding, intelligence, and forensics, takes unusual advantage of the specific legal status of the Native American reserves from which it takes its name. At the company stand I am impressed by how much is made of the reference to the Chenega people. It is omnipresent in the talk of the representatives, as well as in the company's tipi-shaped logo displayed on the walls and on all the Chenega paraphernalia: the pens, shopping bag, USB sticks, and bottle opener distributed at the stand. But the real surprise comes when, after talking with a representative for a while about the drone suspended in the stand (on which ‘you can mount anything’), I ask how the company deals with resistance to intrusive drones. Instead of moving into arguments about increased precision and transparency, the representative answers by pointing to our ‘historical responsibility’ towards the Alaskan Chenega ‘who have invested in security rather than casinos’. S/he then slides into talking about the indispensable place of drones intelligence and the global war on terror. Both moves are in effect responsibilising, but they circumvent any reference to technological accuracy or transparency.

The references to the ‘broader picture’ encapsulated by examples like the Chenega's focus on historical responsibility, or the dangers posed by the war on terror, questions of technological accuracy or transparency are made absent. These are moves or strategies that work to responsibilise by leaving blurry and unclear the exact purpose of the invasive co-presence demanded. They shift the terrain towards the general and imprecise. Their advertising is composing a security where the exact place and role of tracking devices is correspondingly unclear, adding opacity to the final collage.

Recasting

Opacity also marks much of the advertising that renders tracking devices acceptable by recasting the protected. In such advertising, no disciplinary or responsibilising measures are called for to make the tracking devices acceptable. Instead, the subject is recast so that the tracking devices become part of it, inserted into its habits, its body, subjectivity, and perhaps even into its ‘care of the self’.Footnote 73 Self, body, subjectivity, and care of the self are necessarily diverse, varying, and contextual. So are the sensibilities surrounding them. To accommodate this, most advertising is framed to preserve, nurture, and encourage this sprawling multiplicity while leaving blurry what the co-presence is about.

A malleable, adjustable co-presence is central in advertising that recasts people, helping them imagine how the tracking devices could be part of their habits, routines, and lives.Footnote 74 As the promoter offering trials for a programme integrating information from different kinds of sensors puts it, after talking about the worry many of his clients [mostly security managers of large companies] express about the resistance to this kind of tracking: ‘People try it. They realize that it really works for them. They get used to it … Mostly that takes care of irrational fears. That is why we are offering these trials.’Footnote 75 Along similar lines, the promoter of a rather conventional looking location tracking device explained that “simple guidelines; as simple as possible is the key” to enabling people to deal with tracking devices as it best suits them.Footnote 76 The advertising revolves around the adaptability of the tracking devices to the usages, circumstances, and people, rather than referencing any generalised transparency and accuracy the tracking devices (may) pave the way for.

The situational, specific, and circumstantial (and therefore ultimately opaque) is even more pronounced when advertising is recasting the protected so that tracking technologies become an inseparable part not only of routines and habits but also of the embodied person. Reference to the literal anchoring of tracking technologies in people – as chips under the skin – recurs as a forbidden fantasy among advertisers. The representative of a larger intelligence/analytics company details the offerings specifically directed at academics and universities, insisting on security in the context of, for example, fieldwork and study trips.Footnote 77 Recounting an incident with a student who had gone astray during a study trip to Palestine, s/he concludes with the rhetorical question ‘don't you also wish you could have a chip in them?’. When I ask if the company would consider chips in this kind of situation the answer is no: ‘It would be ethically unacceptable.’Footnote 78 The discussion then moves into the possibly positive advantageous usages of chips for tracking prisoners and refugees. The second best option to inserting under the skin – namely a firm and permanent possible anchoring of the technology in people through their clothes, their watches, or their digital extended embodied self is broadly unproblematic and is widely used.Footnote 79 It was presented as a pragmatic solution to the practical problems of integrating tracking devices. Not accepting these would ultimately be ‘immoral’, a sales representative working mainly for humanitarian organisations said. It could jeopardise not only their own personal safety but that of other people and perhaps of an entire mission. Working with them is part of growing up and becoming a responsible adult, s/he insisted.

Rendering tracking devices acceptable by recasting security subjects rests on embracing and working with the necessarily inscrutable, diverse, and imprecise insides of sensemaking. Just as the advertising strategies geared to disciplining and responsibilising clients into accepting the tracking devices, this recasting not only allows but cultivates the opacity surrounding the co-presence it imposes and acceptance of the situated multiplicities and differences it cultivates. It does not strive for transparency or clarity. Rather, the advertising speaks much as the Voice inside Mother Eve's head saying, ‘I feel you, but I don't know how to be any clearer about this.’Footnote 80 In the advertising of tracking devices, transparency has not attained the fetish status it occupies elsewhere. Öberg's question of how would one challenge ‘transparent warfare?’ does not appear pertinent in the SCTX context and his ‘“Baudrillardian” wager’ that we challenge transparent warfare ‘without reifying the value of transparency’ seems easy to accept and even to win.Footnote 81 The issues are elsewhere: in the corporeal, opaque insides rather than in the disembodied, transparent outside.Footnote 82

Conclusion

Should we rejoice? Is the conclusion of this excursion into the world of tracking device advertising and the security it is composing comforting for those of us (including Öberg) interested in critiquing militarising processes? After all, the above has shown that this advertising is composing a security collage with pieces that look rather different from those most security scholars (critical or otherwise) focus on. The affective sensemaking, governing from the inside and opaque co-presences that have been emphasised run contrary to the strategic, technical calculus, governing at a distance and through transparency that are often the central preoccupations. However, while this difference implies a significant qualitative shift of politics, it does little to soothe concerns with the militarising effects of security technologies. Rather, a security composing that emphasies the affective, opaque inside gives depth to the spread of military/security concerns. Unfortunately, this in-depth imbrication is hardly ‘de-securitizing’.Footnote 83 It makes the military/security commodities more ‘sticky’. The advertising of tracking devices not only ‘extends’ the reach of military/security matters but also fundamentally ‘deepens’ it.

While the conclusion that the advertising of tracking devices diffuses a sticky security is discomforting, the compositional analysis that led to it also opens ways for engaging it. Working with compositions ensures that we do not become ‘prisoners of our abstractions’ as Isabelle Stengers puts it.Footnote 84 Instead, it is a way of drawing attention to the multiple, complex, contradictory, paradoxical, and evolving processes at work. It is intent on showing – rather than glossing over and smoothing out – the tensions between heterogeneous aspects of advertising by collocating and turning the composition into a collage. The above did exactly this, juxtaposing internally contradictory pieces of advertising (sensory resonance, inside proximity, and opaque co-presence) and continuously insisting that these add to, rather than replace, the pieces to which I have opposed them (reasoned calculation, outside distance, and transparent separation). In the tensions between the pieces of the resulting collage there is scope for politics. More than this, focus on composing is a focus on process and therefore also on fragility and reversibility. The pieces of the collage may be sticky but focusing on how they were added gives clues about what it takes to remove them. If, for instance and as argued above, responsibilising is central to the acceptance of the co-presence of security technologies, directing attention to this and hence underscoring the import of refusing responsibilisation, is one step on the road to resisting the sticky security of the advertising. Finally, focusing on the composing of collages also leaves an awareness of the spaces in between, and hence of the openness of any collage and composition.

Alderman helped me open this article. Alg will help me close it. Her collage Risk Resistance (Figure 7) reminds me that I have told a linear and straightforward story about a non-linear and complex reality: that of the security compositions generated through the advertising of tracking devices. Moreover, I have left out many stories that play a role in the composing of security. Most significant are perhaps the stories of those resisting militarising security compositions, such as the collages of tracking advertising. These are the stories of those who break the wave of militarisation, who speak from their guts, flex muscles they don't have, and the stories of those who try out the many different punches their way of seeing calls for even if they know that their punches are disproportionate. Whose stories we tell matters. Perhaps it should be a priority to tell the stories of a resistance that invariably appears unreasonable because it is aimed at processes that are not about reason, distance, and transparency but about affects, insides, and opacity? Certainly, CodePink, Guerilla Girls, Monochrome and many others have appropriated the ridicule and made it the basis for action. Perhaps critique generally, and academic critique particularly, needs more courage to do similarly? Perhaps Stengers is right: we need to learn to laugh. ‘The laughter of someone supposed to be impressed always complicates the life of power.’Footnote 85 Critique laughing at itself would complicate life also for the power that makes critics lack the courage to appear ridiculous. But that story is for another time and/or for someone else to tell. The contribution of this article is to provide a sense of why the risk of ridicule may be worth taking and what the punches of resistance could/should aim at.

Figure 7. Risky Resistance, collage by Alg, Berlin, 2018.

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgments are due to Alg for inspiring me to write this, to Claudia Aradau, Rocco Bellanova, Noe Cornago, Charlotte Epstein, Victor Rodriguez, Lucy Suchmann, Juanita Uribe, Elspeth van Veeren, and others who have commented on presentations of this argument. The suggestions of three anonymous reviewers and the constructive comments by Jonathan Austin have done much to shape the current formulation. Responsibility for the result obviously rests with me.

Anna Leander is Professor of International Relations at the Graduate Institute in Geneva. She also holds part-time positions also at PUC, Rio de Janeiro, and at the Copenhagen Business School. She is known primarily for her contributions to the development of practice theoretical approaches to International Relations and for her work on the politics of commercialising military and security matters. Her work is always interdisciplinary and mostly collective. She has authored around one hundred publications, including recent publications in Environment and Planning D: Society and Space and The Indiana Journal of Global Legal Studies. She currently contributes to two major research projects: the Violence Prevention Initiative and the Nordic Centre of Excellence on Security Technologies and Societal Values. In both projects, Anna focuses on the material politics of commercial security technologies and the aesthetic and affective dimensions of this politics. Anna has extensive experience with collective editorial and organisational work. She is currently co-editing the Cambridge Elements in International Security and the Routledge Private Security Studies series. Anna is a board member of the European International Studies Association.