Introduction

The election of President Donald Trump in 2016 signalled a shift in the US towards an outspoken nationalistic foreign policy, setting the country on a path of potential disagreements with many of its traditional allies and away from the rules-based international order paradigm of previous decades.Footnote 1 This change recently led some senior and mostly academic opinion-shapers to question the foundations of the postwar order grand strategy,Footnote 2 specifically the long-term sustainability of maintaining US global primacy through instruments like the current alliance system, trade agreements, military interventions, and export of US values. These criticsFootnote 3 argue that it is increasingly impractical and unrealistic to continue the US foreign policy of the post-Second World War and post-Cold War period given the global trends towards a multi-centric realignment of powers, the legacies of self-inflicted US foreign policy mistakes in recent history, the long-term erosion of the country's economic and technological clout, and the creeping loss of public trust in the US elites’ leadership capability, their policies, and values.

This critique of the fundamentals of the liberal world order, however, has not been heeded by many members of the foreign policy community, including not only foreign policy think tank policy analysts but also media commentators, diplomats, members of the State Department, Congressional staffers, and other experts in federal agencies, lobby organisations, and academia. After Trump's inauguration, most of these foreign policy elites were not in the mood to discuss or develop a new substance and direction for US foreign policy in recognition of ongoing global changes.Footnote 4 Seeing the foundations of the existing rules-based order under assault by President Donald Trump, they fell back into a defensive modus operandi because they did not want to be ‘present at the destruction’ of an order that – in their views – had worked so well in the past.Footnote 5 This raises the question why, now and then, many members of the foreign policy community are reticent to critically evaluate US grand strategy during a time when the enormous shifts in domestic and international relations demand new answers.Footnote 6

The fact that the US foreign policy community was caught unprepared by Trump's nationalist ‘revolution’, their perceived bystander mentality, and their intellectual procrastination towards adapting new, forward-looking concepts and ideas, has often provoked the ‘blob’ label for them. The term was derogatorily coined by President Obama's Deputy National Security Advisor for Strategic Communication Ben Rhodes in a 2016 New York Times interview with David Samuels.Footnote 7 Since then the phrase has become popularised as a label for the attitude of a large segment of the foreign policy elite that lives in a groupthink tower, regurgitating conventional wisdom about precepts of the prevailing international order.Footnote 8

The ‘blob’ thesis has gained traction in political discourse because it expresses the public's lack of trust in the foreign policy community's predictions and policy recommendations.Footnote 9 This uneasiness has been articulated by some prominent and outspoken academic critics. They allege an uncritical grand strategy consensus among mainstream foreign policy commentators, experts, advisers, and lobbyists in the Beltway. Stephen Walt is one of those critics: he defines the blob as ‘individuals and organizations that actively engage on a regular basis with issues of international affairs’Footnote 10 in and outside of US government. Since they are involved in policy advising and policymaking, they are part of a dense network that crosses partisan lines either through formal shared membership in organisations or informal personal relationships and associations, including friendships, marriage, and kinship.Footnote 11 In government positions like the State Department, DoD, and Congressional staffers, or as members of think tanks, academia, lobby organisations, and the media, these ‘influentials’Footnote 12 wield direct and indirect power by shaping foreign policy and policing the boundaries of acceptable policy views.

According to Patrick Porter, another critic of the US foreign policy community, one of the main traits of the blob is the habit of self-censorship based on ‘obvious, axiomatic choices made from unexamined assumptions’,Footnote 13 including the belief in the liberal internationalist ideology of primacy, American exceptionalism, and military interventionism, according to which ‘the United States’ hegemonic leadership is axiomatically good for the United States and the world’.Footnote 14

The blob thesis of a foreign policy elite intent on upholding the traditional order at all cost is contradicted by the ‘polarization’ thesis. Based on earlier leadership studiesFootnote 15 about the breakdown of the US foreign policy consensus, these adherentsFootnote 16 argue that in recent decades the divisions about the strategic and tactical outlines of US foreign policy decision-making have become more pronounced along ideological and Democratic-Republican partisan lines, a thesis that fits pluralist theory assumptions.Footnote 17

Robert Shapiro and Yaeli Bloch-Elkon, for example, refer to various large quantitative surveys about foreign policy attitudes conducted by the PEW Research Center, the Chicago Council on Global Affairs, the Council on Foreign Relations, and others, claiming that partisan conflict and polarisation between the American public and its leaders reaches back to the 1980s but became increasingly apparent during the G. W. Bush and Obama administrations.Footnote 18 They argue that almost unbridgeable partisan fissures developed between Republican and Democrats, ideological conservatives, and liberals. According to defenders of the polarisation thesis, Republicans became dominated by realists and neo-conservatives who favoured a robust foreign policy of hard power to promote US interests, such as economic sanctions, military pressure, and coalitions of the willing. Democrats, on the other hand, were dominated by liberal internationalists and preferred instead, but not exclusively, soft power tools, pushing, for example, a values agenda, like democracy and human rights promotion or supporting the responsibility to protect doctrine.

From the viewpoint of ‘polarisation’ advocates, more recent surveys show that splits have emerged within both major parties and among the foreign policy elite on questions about how to deal with terrorism, failed states, immigration and refugees, globalisation, international treaties and free trade agreements, alliance burden sharing, and foreign aid.Footnote 19 Donald Trump was able to tap into anti-globalist resentments and mobilised support from fringes of the foreign policy community excluded from the mainstream consensus.

Because both the blob and polarisation theses claim to be based on solid evidence, it remains a puzzle how to reconcile their propositions. Can a foreign policy community that is polarised along partisan and ideological lines at the same time share an international order consensus? I argue that the answer to this question requires probing beyond quantitative studies and standardised questionnaires. Using an abductive reconstructivist methodology it will become evident that both the blob and polarisation theses capture elements of prevailing beliefs among experts but lack a comprehensive explanation of the complexity of US grand strategy imperatives.

After a short description of the sample, method, and evaluation, this article will describe the five fundamental foreign policy ‘rules for action’ identified by the qualitative analysis of 37 in-depth interviews: safeguarding US American global leadership; maintenance of alliances; securing US prosperity; orientation towards US-defined values; and the belief in a US mission. From observable regularities of the interviewees’ positions towards those imperatives, four types of foreign policy experts were abductively distinguished: nationalists, realists, pragmatic liberals,Footnote 20 and liberals. The latter three types, labelled here under the umbrella category ‘globalists’, are in favour of upholding the postwar international order as a win-win arrangement. They oppose the efforts of Trump nationalists to tear down this order in favour of a transactional and unilateral zero-sum relationship of the US with friends and foes. But realists, pragmatic liberals, and liberals are unsure of how to explain and respond to Trump's nationalism beyond a defensive or wishful hope to save the vestiges of an US-centric international order.

The summary will draw theoretical and methodological conclusions from these empirical findings and reveal that the blob thesis, while correctly capturing a pro-international order consensus among globalists, neglects deeper divisions that divide realists, pragmatic liberals, and liberal's interpretation of how to achieve international order goals. On the other hand, the polarisation thesis, while correctly describing a partisan and ideological divide among the foreign policy community, ignores the anti-nationalist consensus of the globalists.Footnote 21

As this study demonstrates, richer and more contemporary insights into the divisions and consensus of foreign policy experts’ grand strategy perceptions can be gained by applying qualitative methods.

1. Sample

This study is based on the assumption that foreign policy experts share a set of ingrained beliefs about the role, function, mission, and obligations of their country in international affairs.Footnote 22 It hypothesises that expert opinion precedes public opinion and influences it in multiple ways, particularly through the media and through policy advising via think tanks.Footnote 23 In brokerage-type party systems with strong special interest groups, think tanks formulate policies and promote partisan ideological objectives to members of Congress, the executive, mass media, and the public.Footnote 24 Think tanks are in constant competition to have their specific interpretations of the advancement of national interests accepted as dominant and to provide definitions of what should be considered ‘us’ versus ‘them’, what is considered legal, useful, and desirable for a society, and its special mission in international affairs.Footnote 25

For this reason, this study focused on interviewing members from prominent Washington, DC think tanks in addition to select congressional staffers, diplomats, academics, and media opinion makers with reputation and expertise. Of the 111 foreign policy experts contacted through a mix of convenience and snowball-sampling methods and using funds and networks from the author's home university in Michigan, 22 individuals declined to participate for a variety of reasons and 52 did not respond to phone messages or to emailed interview requests.Footnote 26 Of the 37 experts (33 per cent) who agreed to an interview, 25 were met face-to-face and 12 were questioned by phone.Footnote 27 The average interview lasted 55 minutes. Because the overall population of foreign policy experts cannot be clearly determined, the sample selection was not representative. Nevertheless, respondents’ occupational functions, party affiliation, age, and sex were considered to ensure that the sample captured a diverse spectrum of foreign policy experts,Footnote 28 thereby fulfilling saturation criteria recommended for qualitative sampling.Footnote 29

Most respondents came from 18 well-known foreign policy DC think tanks, among them six conservative, six centrist, and six liberal or progressive institutions.Footnote 30 Five think tanks were foreign-funded. In addition, a private think tank and a law firm involved with think tank advising were represented in this category. Thirteen of the 26 think tank interviewees were directors or presidents of their organisations. Because of the prevalent ‘revolving door’ job rotating mechanism and the tightly-knit and overlapping networks that characterise the DC foreign policy elite, many US respondents previously held jobs in federal and state positions, academia, the legislative branch, military, foundations, NGOs, other think tanks, private enterprises, law, and investment firms. For this reason, the sample also included five university academics affiliated with foreign policy research or think tank institutions as well as a State Department Deputy Assistant Secretary, a diplomat, three Senate staffers, one staffer from the House of Representatives, and a research director from the Library of Congress.

Eighty-four per cent of the 37 respondents were white males, which is typical for the current race and sex distribution of the expert community in DC. The participants’ average age was 54 and ranged from 32 to 91 years. Forty-six per cent of the interviewed persons held a PhD or JD, and many interviewees had degrees from Ivy League universities or similar institutions in the United States or England, indicating the elite educational status of the sample.Footnote 31 Sixty per cent of the experts were non-partisan or their party affiliation was unknown. Among the 15 persons with a known party affiliation, nine were Republican Party members and six were Democrats. From the variation of responses, it can be deduced that the sample reaches across ideological and political lines from progressive left to liberal, independent, conservative, and nationalist positions.

2. Reconstructivist methodology and evaluation

Analysing these 37 interviews required making assumptions about the conceptualisation and empirical operationalisation of grand strategy imperatives that guide policy actors in their interpretation and enactment of foreign policy.Footnote 32 In this study a reconstructivist approachFootnote 33 was applied combining ontological, epistemological, and methodological premises from hermeneutics,Footnote 34 grounded theory,Footnote 35 and philosophical pragmatism's ‘belief is a rule for action’.Footnote 36 This approach shares a similar focus on the ‘intersubjective construction of reality’Footnote 37 by foreign policy actors as the theories of political and strategic culture and related concepts like cognitive mapping,Footnote 38 operational mindset/code,Footnote 39 framing, and image theory. The author preferred the reconstructivist methodology for this project because its ‘rules for action’ concept pays attention to the interaction between political structures and human agency in the form of coagulated shared ideas, norms, and interests.

In this study, rules for action are defined as shared sets of beliefs of actors about grand strategy imperatives in a specific foreign policy ‘structure of corporate practice’Footnote 40 that has been formed over a long timeFootnote 41 and adheres to basic principles of cognitive consistency and legitimacy.Footnote 42 Rules for action are the complex result of internalised social and cultural learning such as collective memories, traditions, and dominant societal norms. In addition, they are influenced by shared experiences of historical events, lessons learned from political decisions and their fall-out, and future expectations.

A reconstructive analysis of interview responses, speech acts, or documents allows trained observers to distill prevalent rules for action contained in these utterances. In qualitative analysis the focus is therefore not on testing positivist assumptions about expert beliefs using theoretical models of rules for action (which are not yet existing for this specific situation) and then deducing if empirical evidence fits hypotheses or not. Instead, the goal is to extract evidence in form of patterns through iterative procedures of coding and abductive analysis. Through this process generic knowledge and new conclusions are drawn. This way the actors’ (not the researchers’) understanding of fundamental rules for action and related typologies are reconstructed.Footnote 43 By abductively creating new theoretical propositions open to empirical falsification and revision in the future, this study is ‘crossing paradigmatic borderlines’,Footnote 44 helping us to develop a deeper and richer explanation of elite beliefs.Footnote 45

The evaluation of the audiotaped interviews using MAXQDA qualitative software followed the flexible coding approach,Footnote 46 starting out with the creation of summary memos and indexing the answers to questions about how respondents described their foreign policy beliefs, lessons learned, challenges ahead, future foreign policy priorities, etc. Then ‘summative, salient, essence-capturing, and/or evocative attributes’Footnote 47 of responses were thematically coded into categories such as leadership, prosperity, alliances, values, US mission, etc.Footnote 48 The latter codes were then further subcategorised and reordered. The iterative process of (re)coding, comparing, ordering, linking, and classifying was strengthened by triangulating the qualitative findings with a quantitative comparative evaluation of sociodemographic characteristics of the respondents to test the credibility, applicability, and consistency of the sample, coding, and analytical evaluation.

In sum, unlike quantitative surveys using preset categories and standardised questionnaires developed by the researcher, the reconstruction of rules for action and the actor typology in this study was derived from how experts represented their positions in the open-ended interviews. The abductive results are actor-centric, allowing unique and highly reliable patterns of thinking to emerge from the actors’ views, thereby improving our insights into the complexities of their reasonings. In this way elite interviews become ‘a tool to tap into political [actor's] constructs that may otherwise be difficult to examine’Footnote 49 by standardised survey questions.

3. Foreign policy rules for action

This section describes the different interpretation of the meaning and application of five foreign policy rules for action by four actor types, that is, nationalists, realists, pragmatic liberals, and liberals. As mentioned earlier, the latter three types fall under the umbrella term ‘globalists’ because they believe in the maintenance of the postwar international order in contrast to nationalists.

The typology reaffirms the existence of relatively stable and consistent but also constrained ideological worldviews of US foreign policy experts.Footnote 50 While the typology labels used here are nominally similar to previous IR classification schemes,Footnote 51 their content is different. It is different because the typology used here was generated through qualitative reconstruction from interviews in autumn 2017, not through quantitative deduction based on standardised survey questions.

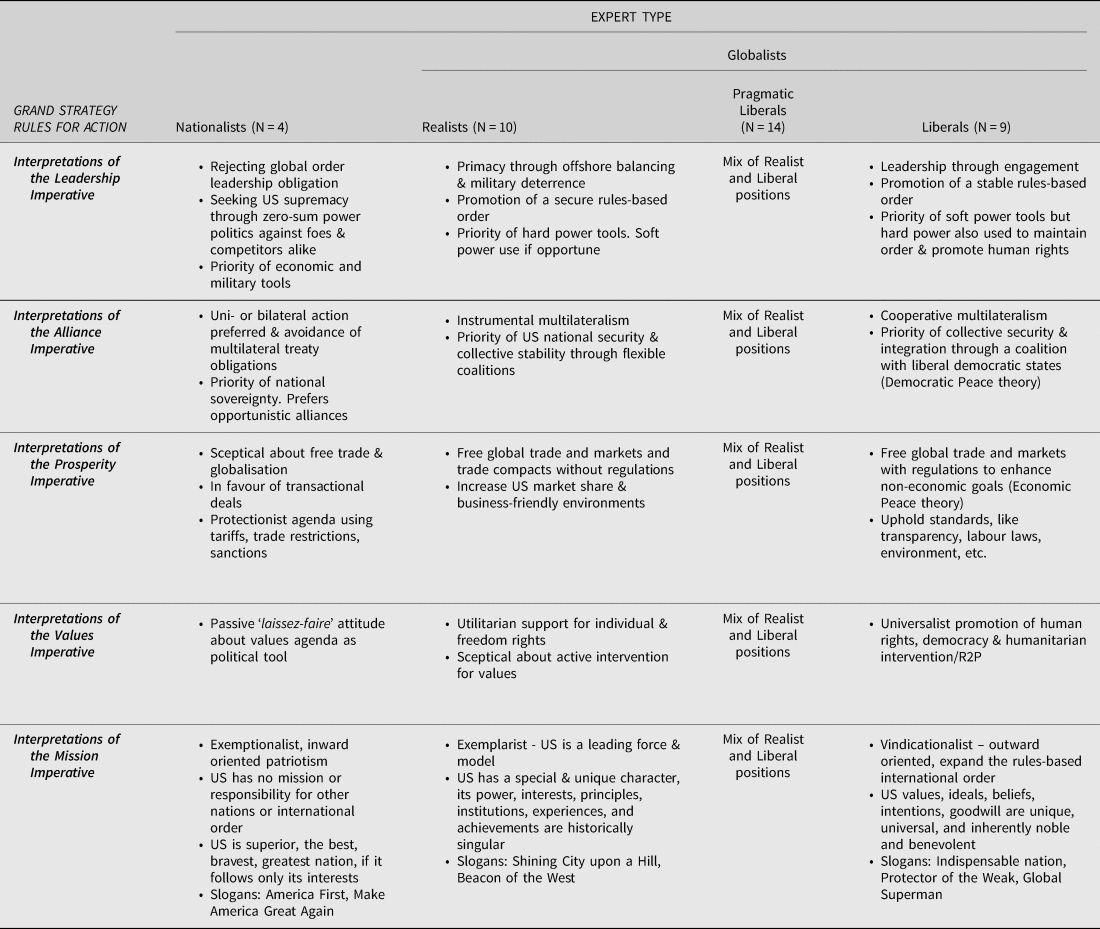

Given the limited sample size and the often idiosyncratic and ambiguous nature of individual actor's assessments of complex foreign policy issues, the rules for action and typology matrix is imperfect and only approximate. Table 1 summarises the five most salient interpretations of rules for action among the sampled expert types.

Table 1. US grand strategy rules for action by expert type.

Note: Placement of individual expert's beliefs by type and rule for action is approximate.

3.1. Global leadership

As mentioned, rules for action work like frames through which decision-makers, experts, and other relevant actors reflect their country's global role, its ultimate goals, and the values for which they stand, and then use them as guidance to make judgements about present and future action. In that sense, rules for action become actor imperatives.

The most important rule literally stated by respondents was ‘US global leadership’. It was usually described as maintaining US military and diplomatic presence on all continents to guarantee a US dominated global order and peace. Many experts mentioned goals like protection of the US homeland against nuclear war and defence of its borders, institutions, and citizens against crime, terrorism, cyberattacks, and illegal immigration.Footnote 52 However, nationalists, realists, pragmatic liberals, and liberals differed in the terminology used, the priorities, and methods to achieve this rule for action.

While many liberal experts favoured using the term ‘leadership’, smaller numbers of respondents used ‘liberal hegemony’, or the word ‘primacy’, common in the IR literature and a favourite among realists in the sample.Footnote 53 A diplomat provided the following definition of leadership:

Our US bipartisan fundamental principle has been to create, manage, maintain, protect, and nurture a global political, economic, and security order in which we as a country can be secure, thrive, and advance economically and politically. … Building a global architecture, a political, security, and economic architecture within which we [the United States] could prosper, maintain our security, and pursue our interests. This is for me one of the most fundamental US bipartisan principles. … We [the United States] see ourselves as the architect, manager, and protector of that architecture (Case 28/Liberal).Footnote 54

As mentioned, ‘primacy’ covered similar dimensions as ‘global leadership’ but with a focus on superiority, domination, and reigning in rising powers or adversaries, a point that is also recognised in the literature.Footnote 55 In the interviews, nationalists tended to be ‘hyperrealists’, considering ‘primacy’ a ‘natural’ by-product of a nation combining its superpower with its interests. Realists and many pragmatic liberals argued that the US seeks to promote and protect US military and political interests and assets abroad and to ‘maintain the dollar as the major currency, maintain American global economic dominance, and control of the trade lines’ (Case 19) while carefully avoiding too much and too little foreign intervention to retain its legitimate global authority.

A few in the liberal group characterised the United States as a ‘hegemonic’ leader, a term that was avoided on Capitol Hill and by most think tank respondents because it is seen as pejorative. But even if this term was not used, the goals of US foreign policy mirror its dominance in world politics. For example, a respondent pointed out that the United States follows a geopolitical strategy of forward continental defence with the goal of ‘preventing regional hegemons on either side of the Eurasian landmass emerging. Preventing particularly Germany and Japan from becoming nuclear powers by providing security for them’ (Case 17/Realist). Or in the words of another realist, the United States does not want to ‘let major powers grab and dominate pieces of the planet’ (Case 33/Realist).

Interviewees also mentioned the US leadership task ‘to maintain or expand American spheres of influence’ by stabilising or replacing regimes by those more willing to cooperate, and, at the same time, by containing adversaries. A realist think tank director referred to the IR scholar John Ikenberry, who supposedly described the

genius of the American system … that you use your power not to make people want to do what you do, but you make it so attractive or so good for them that they want to do it at their free will (Case 10/Realist).

Members of the liberal group less openly displayed such shrewd foreign policy views and, instead, stressed the principle of peacefully engaging adversaries and competitors through diplomacy and other soft power tools to promote a stable rules-based order. Liberals criticised a tendency towards militarisation among hard power realists to ‘take out the hammer when you reach for the toolbox’ (Case 15/Liberal). But liberals were not averse to the idea of intervention abroad to

‘fix’ [countries] with [our allies]. It is somewhat naïve but it certainly influences how we talk about foreign policy [in] any corner of the world. You will [always] find people who are arguing for US involvement. Whether it is from the development angle, trade, or military peacekeeping/peacebuilding … the notion of [US involvement] is still the normal conversation going on in Congress (Case 12/Liberal).

Among all respondents, a consensus existed about the need for US global leadership/primacy. However, globalists and nationalists strongly differ on the means for achieving this goal, which supports the blob thesis. For example, globalists criticise the nationalists’ transactional zero-sum attitude of ‘might makes right’ as rejecting the obligations of benign and legitimate US global leadership. Instead, the US should also respect the rules of the international order it helped to establish. On the other hand, ideological and partisan differences also existed between realists, pragmatic liberals, and liberals about the precise meaning of leadership and how to implement it within the framework of the international order. This finding supports the polarisation thesis. For example, while not being opposed to the use of soft power, many realists expressed sceptical views about its effectiveness. For them the maintenance of military superiority was a legitimate means to play out US advantages in a rules-based, but US dominated, order. Liberals, on the other hand, prioritised soft power and leadership through engagement strategies, whereas pragmatic liberals typically favoured a mix of hard and soft power, like ‘a commitment to peaceful settlement of international disputes backed by the use of force when necessary’ (Case 27/Pragmatic Liberal).

3.2. Alliances

Another rule for action that all respondents shared in the interviews was the imperative to uphold a system of ‘alliances’ for the good of the United States and for its allies, in particular containing so-called ‘bad guys’ and providing order and stability through the use of international institutions, laws, and treaties.Footnote 56 No matter what the actor type, there was a consensus that the NATO alliance and ‘fair’ burden-sharing are central policy pillars for historical, military, political, economic, and cultural reasons:

[For US] foreign policy elites and the military defence elites, for them, NATO is still very important, MORE important than sometimes for the Europeans. There was not much done with regard to NATO in the last 25 years. But for the US elites it is still a very important institution (Case 19/Pragmatic Liberal).

However, disagreements existed among respondents about the meaning and importance of alliances and multilateralism. Nationalists, while rejecting the label of being isolationists (Case 35/Nationalist), were most outspoken against giving ‘too much legal, cultural, political power to globalists, the UN’ (Case 1/Nationalist), international law, and ‘multilateral agreements’ (Case 36/Nationalist), fearing a loss of US national sovereignty to exercise foreign policy in uni- or bilateral fashion when opportune. Realists, pragmatic liberals, and liberals, on the other hand, recognised the benefits of international cooperation in enhancing US national security and global stability. But realists harboured a more instrumental, and liberals a more cooperative, interpretation of collective security and alliances with democratic capitalist states with similar values.

For realists, the US national security and stability of the order had precedence. If necessary, they would resort to coalitions of the willing. International institutions (like the UN) and international law and treaties (like the Paris Climate Accord) were often judged sceptically, even negatively, either as instruments of weaker powers wanting to constrain the US freedom of action or as institutions incapable of fulfilling their goals. Even some liberals agreed that changes were needed, like the following Congressional staffer:

We do need to develop a strategy of how the United States wants to approach that [goal of renewing international system]. We need to develop it in consultation with all of our partners on the [UN] Security Council, even those who are rivals in many instances. We need to speak more frankly with each other. … All nations need to be consulted in developing a plan to renew the international system (Case 22/Liberal).

Except for the centrality of NATO as a pillar of US military and political global leadership, the interpretation of who should be considered an ally, when to go it alone, and what multilateralism signifies was discussed very differently. Realists, pragmatic liberals, and liberals shared a consensus in maintaining a system of alliances because it benefits the US and rejected the nationalist's adversarial or transactional relationship with traditional US allies and their emphasis on sovereignty. But the interpretation of how to practice this rule for action is controversial among realists, pragmatic liberals, and liberals. This illustrates again that both the blob and polarisation theses capture elements of prevailing beliefs among experts, but they lack a comprehensive explanation of the different levels of agreement and disagreements surrounding the international order paradigm.

3.3. Prosperity

One more rule for action mentioned by all respondents was the ‘prosperity’Footnote 57 agenda. It concerns the promotion of private entrepreneurship, market capitalism, and related institutions enhancing US prosperity through its global spread. Again, differences appear when respondents discuss what this means and how this imperative should be implemented.

The nationalists believed that ‘free trade is not working for us’ (Case 36/Nationalist). They had a transactional cost-benefit view about how to regain economic primacy and freedom of action through protectionist measures and the abolishment of supranational regulations, constraining trade agreements, and related institutions (Case 1/Nationalist). In contrast, realists, pragmatic liberals, and liberals stressed the domestic and international benefits of an

open international economic system based on free trade … [since] … there are multiple national interests, there is not just one. Internationally, we have an interest in strengthening the rules-based international order, and not seeing a return to spheres of influence worlds or a world divided into trading blocs again and things like that. We have an interest in an integrated and open international economic system because it generates economic growth and employment in the United States …. We have an interest in bolstering our own domestic economy, which, at the end of the day, is the engine of our national power (Case 32/Pragmatic Liberal).

Another pragmatic liberal underscored the objective of strengthening the global position of the United States as a trading nation interested in free access to markets, an opinion that was shared by many other realists and pragmatic liberals:

The goals are the maintenance or extension of the market economy and of the predominance or considerable share of these markets for the United States, for our banks and production companies particularly. More recently, for our electronics and Internet companies. But obviously the maintenance of a very, very large market share in the global market is a goal (Case 14/Pragmatic Liberal).

While pragmatic liberals and realists more often focused on the advantages of free trade for US business, liberals frequently pointed out the role of free trade in contributing to global stability, peace, development, pro-Western attitudes, and the spread of individual liberties, even democratisation. This interpretation reflects major tenets of the economic or capitalist peaceFootnote 58 theory. A few liberals also mentioned foreign aid, fair global trade, or the upholding of standards like the ‘right to work, fair labor compensation, and work under conditions that are humane and safe’ (Case 22/Liberal) as aspects of their interpretation of the prosperity agenda. This is not surprising because liberals are more likely affiliated with the Democratic Party, which has a strong affiliation with the more regulation-oriented unions.

Overall, there was a consensus among realists, pragmatic liberals, and liberals that free trade and market capitalism a.k.a. globalisation is intrinsically good since it has benefited the United States but also the world economy. These experts also were adamant in their condemnation of what they saw as the nationalists' anti-globalist rhetoric, anti-free trade protectionism, transactionalism, and unwillingness to comprehend global prosperity as a win-win proposal. Thus, the observed views of realists, pragmatic liberals, and liberals versus the nationalist corroborate the blob thesis. However, the different attitudes between realists, pragmatic liberals, and liberals about the implementation of this rule for action, such as the degree of regulation, the purposes of trade compacts, and its main beneficiaries, are in support of the polarisation thesis.

3.4. Values

‘Values’ and, what I call in the next section, ‘mission’ agenda are ideational imperatives that help to legitimise US American foreign policy actions. Here the difference between nationalists and globalists is the emphasis on how to define, protect, advance, and spread various aspects of democracy, individual liberties, and the American way of life. While nationalists do not deny the existence of ‘universal’ American values, they express a more laissez-faire attitude about the use of values as a tool of foreign policy. A nationalist academic pointed out that under Trump

we are not going to hector them [allies like Egypt and Saudi Arabia] on human rights issues, … we are turning away from BOTH Bush and Obama (Case 36/Nationalist).

And a former diplomat deflected the question about his understanding of values in foreign policy by stating:

We want ‘America First’, we want to strengthen the United States [to …] keep things safe, secure, prosperous, and just’ for the United States (Case 1/Nationalist).

Among realists, pragmatic liberals, and liberals, on the other hand, a consensus existed that values are part of the moral compass of US foreign policy, though their meaning and implementation differed. Equal numbers of experts, among them many liberals and pragmatic liberals, identified values with a moral commitment to promote human rights, human dignity, and tolerance, or a responsibility to protect (R2P). Others defined it as the support for democratic governance, rule of law, or the division of power, including a system of checks and balances. A third, but smaller group of mostly realists, focused on fostering the practice of individual rights and civil liberties, the ability to pursue life, liberty, happiness, and various other freedom rights regarding economic activity, the free exchange of ideas, innovation, diversity of lifestyles, or making sure that foreign policy is geared towards protecting humans ‘from’ something, like corruption, totalitarian ideologies, and autocratic state incursion.

While not denying that values should be a complement of foreign policy for ‘strategic reasons’ (Case 13/Realist) or undergird the US ‘security architecture’ (Case 16/Realist), many realists expressed scepticism about the active promotion of values through military or political intervention, such as a former US ambassador:

For instance, in dealing with Russia, we should not be concerned about the way Russia is ruled. I do not like or admire Vladimir Putin, but I am more interested in making sure that we do not find ourselves fighting the Russians. When has Russia been democratic? The same goes … I worry about China as a global superpower, not about how China is ruled within China. I do not think it should be the role of the United States to intervene around the world and promote our values (Case 3/Realist).

Typical of pragmatic liberals was the comment of a think tank member (Case 27) who approvingly observed that the prominent human rights agenda is a normative or aspirational ideal which ‘may slide up and down’ in actual policy preference and practice among different administrations.

In contrast, respondents labelled as liberals and a few pragmatic liberals were more inclined towards promoting values abroad, arguing, for example, that spreading values like democracy would help to avoid ‘wars, bloodshed, and conflict’ because democracies ‘do not go to war with each other’ (Case 18/Pragmatic Liberal), or it would prevent ‘bad things from happening around the world’ (Case 25/Liberal). They also pointed out that the United States is not ‘imposing our values on the rest of the world’ (Case 9/Liberal) but ‘speaking for humanity overall’ (Case 6/Liberal). These interpretations align with the democratic peace theory.Footnote 59

Several experts commented on the moralistic character of the US values agenda as ‘proceeding from a set of almost Protestant puritanical assumptions about the sinfulness of the world’ (Case 16/Realist), or ‘making the world in its [the United States'] image’ (Case 26/Realist), or designed to ‘morally inspire’ Americans (Case 37/Realist) since referring to national interest alone would be considered insufficient to motivate the American public to broadly support US foreign policy. A few interviewees criticised the ‘idealism’ of the values agenda (Case 15/Liberal) or pointed out the hypocrisy of selectively promoting democracy and liberal values, as in the case of Europe, where the United States ‘rules by rules but in Latin America [acts] mostly imperial’ (Case 17/Realist).Footnote 60

Altogether, all experts in this study agreed that values play a role in foreign policy, but beyond that generic agreement fissures between expert types were again visible. Nationalists had the most aloof opinion and considered values a feeble moral imperative that did not contribute much to US power and interests. Realists, pragmatic liberals, and liberals disagreed with this pessimistic attitude, maintaining that values should guide US foreign policy and, therefore, criticised Trump nationalists for their neglect, if not violation, of values by dealing with odious regimes and leaders – a finding that supports the blob thesis. At the same time, globalists differed in their interpretation of the meaning, ranking and implementation of the values agenda, a result that goes along with the polarisation thesis.

3.5. American mission

The multifaceted belief in a US mission was the fifth rule for action shared by all experts. Both the values and the mission imperatives can be considered morally loaded ideological capstones legitimising US global leadership, alliances, and prosperity goals. For nationalists, the mission is a patriotic imperative to restore and maintain the presumed inherent ‘greatness’ and superiority of the country, a rule for action that is aptly expressed in the Trump campaign slogan Make America Great Again. This interpretation of the US mission goes along with an ‘exemptionalist’ America FirstFootnote 61 view, according to which the US is not necessarily bound by rules that apply to other nations.Footnote 62

While this rhetoric is often derided as parochial swagger at the expense of other nations, the globalist variant of the mission imperative has an exceptionalist bend.Footnote 63 It was a nationalist respondent (Case 36) who pointed out that

the dominant thinking in the DC policymaking elites … in both parties. … [assumes] that the United States has a mission … to promote democracy and human rights. And while there may be a case-by-case selectivity, there is this [notion of a US] global mission.

A pragmatic liberal think tank analyst further elaborated on this creedFootnote 64 according to which

the United States has a democracy, stands for goodness, [US values] are not just American norms but are all universal norms. If you can create a global system wherein those virtues get expanded and internalized by an ever-larger number of countries around the world, [the assumption follows that] you will get this more peaceful and more prosperous world. … That [belief] has been the consensus among the foreign policy elite, about how to go about doing that [expansion of the American system] (Case 27/Pragmatic Liberal).

In this study, realists (even hard-nosed ones) favoured a more ‘exemplarist’ view of the US mission, namely to teach the rest of the world that following US ideas, principles, policies, and institutions can lead to national greatness, military power, economic prosperity, and individual happiness. In contrast, liberals and some pragmatic liberals typically followed a ‘vindicationalist’Footnote 65 interpretation of mission, meaning that it is a duty and right of the United States to spread its way of life and its institutions, if necessary by force. This notion is based on a ‘fundamental belief in the rightness of American political values and a belief in democracy and fundamental rights, and a desire … to promote actively those values [abroad]’ (Case 31/Pragmatic Liberal). As mentioned, this rule for action was often expressed in moralistic and idealistic language, evidenced by the experts’ references to the benign or otherwise well-intentioned means and purposes of US foreign policy.Footnote 66

In the interviews, many realists, pragmatic liberals, and liberals confirmed the role that exceptionalism plays in US foreign policy thinking and recognised its presence in the public media, in popular culture, and among members of Congress, think tank pundits, diplomats, and other experts. Even if perceived as having little impact on actual policy decisions,

at least it [exceptionalism] is a core belief amongst probably most political leaders and foreign policy practitioners. You can find some exceptions. Did Nixon and Kissinger believe in American exceptionalism the way I would define it, no, probably not. Does Trump? Certainly not! But generally speaking? Yes, I think so (Case 32/Pragmatic Liberal).

Only very few interviewees denounced the notion that the US has a mission as merely an attempt to give the pursuit of national US interests an appearance of benevolence (Case 13/Realist), or as ‘hypocrisy’ because the country is not ‘living up’ to its own values (Case 24/Pragmatic Liberal, similarly Case 29/Liberal and Case 33/Realist). Another respondent criticised the notion that US foreign policy should be guided by a ‘special set of rules’ as ‘exemptionalist’ (Case 9/Liberal). A non-US think tank expert complained about the abuse of exceptionalism. Referencing Walter Russell Mead,Footnote 67 he commented scornfully that ‘it [America] is … an ideological power that seeks to promote its set of values even at the expense of completely destabilizing the whole world upside-down’ (Case 17/Realist). Such harsh judgement was very untypical. Instead, even the few (mostly academic) critics of a US mission reacted rather defensively to point out that exceptionalist mission thinking was present in other nations, too.

When asked if they believed the American public shared their sense of mission, respondents agreed that American public opinion was more likely in favour of an exemplarist interpretation.Footnote 68 An expert commented that the American public – while not adverse to being told it is exceptional – was inclined to appraise US foreign policy by its perceptible costs and palpable domestic benefits,Footnote 69 rather than blind trust in the foreign policy community's benevolent mission to uphold the international order, for which many Americans – in agreement with Trump – felt little attachment (Case 37/Realist).

Regardless of this known reticence among the US public, the great majority of the globalist experts agreed that the US has a mission and/or responsibility to sustain an international order of its own creation and for its own survival. This conviction also led realists, pragmatic liberals, and liberals to criticise the – in their view – exemptionalist inward orientation, swagger, and jingoism of nationalists. This accord corroborates the blob thesis. However, the degree of legitimacy of the mission rule for action and the best way to accomplish it through vindicationalist or exemplarist action was contested between realists, pragmatic liberals, and liberals in accordance with the polarisation thesis.

4. Main characteristics of respondent types

From observable regularities of the interviewees’ positions towards the five rules for action listed above, the following main characteristics of the four expert types can be established: In this study, respondents who expressed support or sympathy for an anti-globalist, protectionist, values-indifferent agenda of US power and patriotic fervour were labelled ‘nationalist’. They pessimistically worried about the bad intentions of other nations and leaders but optimistically claimed that a more aggressive and frequently unilateral approach in foreign policy would safeguard US interests better and help the US to prevail in a fiercely competitive global environment. They defended major elements of Donald Trump's agenda, such as his veneration of national sovereignty, his complaints about ungrateful NATO allies taking advantage of the US, the supposedly unfair trade practices of competitors, and the nation-building policy mistakes of his presidential predecessors. At the same time, three of the four nationalist respondents disapproved of Trump's blunt attention-getting communication style, bombastic rhetoric, and his often unpredictable, jumbled, and mercurial character and decision-making.Footnote 70

In general, experts who were in favour of securing US primacy through a policy of strength with a focus on maintaining security alliances but sceptical of multilateral commitments, favouring prosperity through free trade, supporting an exemplarist mission while rejecting an active promotion of values through intervention were identified as ‘realist’. For them the US responsibility is to promote its short and long-term interests against competitors and foes alike in a world ruled by the objective laws of brittle human nature. In general, realists (and nationalists) had a more pessimistic Hobbesian worldview according to which historical success and the security of a society is ultimately determined by advancing its national interests and military power – though not only and not always.Footnote 71

Respondents in support of both a mix of realist and liberal imperatives were labelled as ‘pragmatic liberals’.Footnote 72 Their opinions often came with a ring of opportunism, aloofness, and scepticism. Many appeared to be cautious and seemed to not want to take an ideological stand on issues. Compared to realists and liberals, pragmatic liberals appeared to be more willing to change their positions depending on a specific purpose, situation, or circumstance. Often pragmatic liberals combined no-nonsense, even hardnosed realist attitudes with views borrowed from the internationalist playbook of liberals. For example, pragmatic liberals would situationally favour either soft or hard power tools, pursue unilateralism or multilateralism, or strike a win-win balance between advancing US national interests and human rights values at the same time. In some cases, this attitude may also be an indication of non-commitment, that is, upholding norms only rhetorically as an ideal or simply claiming well-meant intentions.

Experts categorised as ‘liberal’ stressed the supposedly ‘noble’ or ‘benign’ intentions and exceptional goodwill of the United States to champion progressive Wilsonian or Kantian ideals of international leadership through engagement, cooperative multilateralism, prosperity through regulated free trade, and the promotion of democracy and universal values like human rights. They considered US institutions and values as unique and exceptional in certain aspects. As the most powerful player in the international system, they also believed the United States has a global responsibility, if not a vindicationalist mission, to uphold the international order and protect the global commons against global threats like climate change, poverty, terrorism, and the like as well as against immoral and unjust adversaries who oppose American ‘universal’ goals and values.

As explained in the previous sections, realists, pragmatic liberals, and liberals, including members of the Republican and Democratic Party, put a clear distance between their own understanding and support of the post-Second World War international order and what they saw as unworkable and antagonising nationalist policy agenda and slogans like ‘America First’. Several respondents pointed out that other members of the foreign policy community, including those in the Trump administration, shared their critical views.Footnote 73 In other words, regardless of party membership or ideological inclination, a gulf separated these ‘globalists’ from Donald Trump and his nationalist followers’ agenda of a zero-sum competitive struggle of nations, enterprises, and leaders.Footnote 74 As we have seen, interpretation differences about nominal identical rules for action also existed between realists, pragmatic liberals, and liberals supporting the notion of the existence of a partisan and ideological polarisation. At the same time, their unmitigated opposition against nationalist positions justified their categorisation as the blob.

Summary and outlook

The purpose of this article was to present the findings from 37 qualitative interviews conducted in autumn 2017 that help us to better understand the dimensions that characterise US grand strategy imperatives a.k.a. rules for action during a time of enormous shifts in domestic and international relations after Donald Trump became president. Two seemingly contradictory explanations, the blob and the polarisation theses, have attempted to explain foreign policy elite perceptions. The reconstructivist methodology used to analyse the interviews revealed both strengths and weaknesses in these explanations. While each thesis captures elements of prevailing grand strategy rules for action among experts, each lacks a comprehensive explanation of the commonalities and differences, as well as shortcomings and conflicts inherent to these imperatives.

The polarisation thesis ignores that realists, pragmatic liberals, and liberals, that is, the globalists, all agree with the postwar international order's five rules for action, defending them against Trump's nationalist challenge. The blob thesis, on the other hand, ignores the existence of continuous ideological and partisan cleavages that divide the globalists among themselves in their interpretation of the order's imperatives.

Because the definition, meaning, and implementation of the five salient rules for action among the expert interviewees were so broad, they allowed for a variety of respondent interpretations, even contradictory ones; for example, the how, where, when, and why of soft and hard power use while exercising global leadership/primacy. Similarly, different understandings existed among the four expert types regarding who should be considered an ally, the degree of uni- or multilateralist policies, and the engagement with allies and foes alike. Regarding the prosperity rule, the balancing of domestic with foreign policy needs, the degrees of regulation, the purposes of trade compacts, and its main beneficiaries were contested. Different interpretations also applied to the two ideational values and mission rules for action. The meaning, importance, legitimacy, and implementation of ‘universal’ values versus national interests and how US foreign policy mission is defined, legitimated, and should be practiced was in dispute. These disagreements reflect inherent conflicts between the five rules for action, such as pursuing power politics to implement national interests and, at the same time, upholding values like democracy, justice, and human rights.Footnote 75

Nationalists stood out because they opposed the globalist notion of multilateral and cooperative arrangements of sharing power and prosperity as being naïve and detrimental to US interests and dominance. The hard-nosed Machiavellian attitude about zero-sum transactional relationships with friends and foes alike, led nationalists to discount the usefulness of values for US foreign policy grand strategy. Instead, they saw values as limiting the exercise of superpower sovereignty. Nationalists also unabashedly advocated for the exemptional greatness of the United States over the globalists' vindicationalist or exemplarist mission imperatives.

How can we explain the findings that realists, pragmatic liberals, and liberals differ in their interpretation of the liberal order grand strategy but at the same time express a consensus in support of this order against the nationalist insurgency? According to Louis Schubert, Thomas Dye, and Harmon Zeigler's elite theory, the maintenance of political, social, and ideological power is an elite's priority. Because Trump is questioning the imperatives of the postwar world, the order's supporters see this as an existential threat to their fundamental creed and existence, regardless of their own partisan and ideological disagreements, which ‘are largely limited to means of achieving common [globalist] goals’.Footnote 76 In addition, since Trump won his office as an anti-elitist outsider attacking the professional foreign policy class in DC, he created a ‘rally around the flag’ effect, alienating experts of all convictions and – ironically – also making it difficult to staff his administration with loyal and qualified supporters.

What explains the reticence of the interviewed realists, pragmatic liberals, and liberal experts to develop an alternative narrative beyond the postwar US-centric international order as response to the nationalist challenge? From the interviews it became clear that most respondents believed the postwar order had successfully served US interests and values – and it would continue to do so.Footnote 77 While embracing the benefits of the international order, realists, pragmatic liberals, and liberals were at the time of the interviews in autumn 2017, still unprepared or unwilling to respond to Donald Trump's nationalist agenda with a new strategic narrative. One of the reasons for their defensive attitude was the shock of Trump's election. Many interviewees stated that before his election they had not realised the danger posed by nationalism nor had they thought about the origins and causes of Trump's success or contemplated how to respond to his insurgency.

Instead, the comments of some interviewees displayed vague hopes that the damages of the Trump administration's foreign policy could be somehow be mitigated by the moderating influence of the so-called ‘adults’ in the White House, reasonable voices in Congress, or the Mueller investigation that started in May 2017.Footnote 78 These wishes were at the same time often mixed with palpable pessimism about the irreparable effects of Trump's policies combined with a gloomy ‘present at the destruction’ posture about the vanishing fortunes of the globalist international order.

Other respondents expressed the hope that after Trump, the postwar, US-centric world order somehow could be revived to its previous glory through some miraculous ‘snap back’ to the status quo ante where supposedly US benevolence and good intentions ruled.Footnote 79 Altogether, globalists, like those sampled in this study in autumn 2017, did not critically reflect on their rules for action nor were they ready to formulate foreign policy alternatives.

Because international relations are rapidly changing, partially as a consequence of Trump's actions, it is unlikely that US foreign policy can or will simply turn back the clock to ‘business as usual’ after Trump is out of office in 2020 or 2024.Footnote 80 Cosmetic changes to the postwar grand strategy, like a reconstitution of the globalist consensus via re-emphasising of soft power values or more restraint, may not suffice either. Therefore, the criticism of Walt, Mearsheimer, Carpenter, and other senior academic commentators and analysts remains valid.Footnote 81

In fact, together with the ceaseless dismantling of the rules-based order by Trump since taking office in January 2017, it appears the Beltway's consensus on reviving the postwar order in its pre-Trump form shows signs of dissolution. For example, a discussion has started among ideological and partisan groups from left to right about how to deal with the shortcomings of the international order grand strategy and what to put in its place after Trump.Footnote 82 These voices recognise that whether caused by outside forces not controlled by the US, or by American mistakes and incompetence, a collapse of central pillars of the current international order could lead to new arrangements that are less favourable to U.S. interestsFootnote 83

From the perspective of elite theory, however, a certain scepticism is advisable. How realistic is the expectation that the prevailing inertia and group think mentality among the foreign policy expert class in DC eventually will give way to a burgeoning pluralist grand strategy debate that will overcome the prevalent strategic narcissism in favour of strategic empathy? It is not yet clear if the ‘mainstream’ foreign policy community is willing to critically assess the shortcomings of the past and is ready to make fundamental adjustments to US foreign policy towards a peaceful, sustainable, and stable new international order where the pursuit of national interests aligns with multilateralism, collective security, international law, and values, like human rights. A reform of the traditional grand strategy consensus is influenced by many imponderables, not least the continuing belief in America's exceptionalist mission, inherent greatness, primacy, and interventionism as well as the seductive allure of nationalism à la Trump.Footnote 84

As, with any scientific approach, the findings presented in this study are incomplete and limited in their scope.Footnote 85 However, they do demonstrate the value of qualitative studies and the utility of the reconstructivist method in developing an empirically grounded typology to describe the dimensions that characterise US grand strategy imperatives during a time of enormous shifts in domestic and international relations. Complementing earlier leadership studies and contemporary large quantitative surveys, these in-depth interviews provide additional rich insights for policy analysis about the complex reasonings of elites. Such studies deserve consideration in future empirical investigations that will hopefully test and refine the outcomes presented here since a more detailed knowledge of elite beliefs will allow to deeper comprehend the direction US foreign policy may take in the future.Footnote 86

Acknowledgements

The author is grateful to Kay M. Losey, Ulrich Franke, the editors, and anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments and suggestions. In addition, I want to thank all policymakers, Congressional staffers, think tank members, diplomats, academics, journalists, and others who allowed me to interview them.

Hermann Kurthen is Professor of Sociology at Grand Valley State University in Michigan. He previously taught at Stony Brook University in New York, the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, and Freie Universität Berlin. He co-edited Safeguarding German-American Relations in the New Century: Understanding and Accepting Mutual Differences (Lanham, MD, 2006); Immigration, Citizenship, and the Welfare State: Germany and the United States, 2 vols (Greenwich, CT, 1998); Antisemitism and Xenophobia in Germany after Unification (New York, NY, 1997), and has served as Associate Editor and Editorial Review Board Member of International Sociology. See https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Hermann_Kurthen.