Introduction

When violins fell silent is a remodelled title of a Slovenian commemoration called The night when violins fell silent, dedicated to victims of the porajmos or Romani genocide during the Second World War. The memorial event has been held on 2 August since 2014. The date corresponds to the Romani Holocaust Memorial Day that was accepted by the resolution of the European parliament in 2015 (Toš, Reference Toš, Klopčič and Bedrač2015: 41–42). At that time it was ‘still largely ignored and […] therefore not acknowledged by the broad public and often not recognised or taught in schools, thus placing Roma people among the “ignored” victims of the genocide during World War II’ (European Parliament, 2015).

In the past, the Holocaust itself was a rarely discussed topic amongst Slovenian scholars, as it was considered that it had somewhat bypassed Slovenia, even though the Slovenian Jewish community was almost completely destroyed in the process. This view has changed in the last decade, as the subject has gained more scholarly and public attention (Klopčič & Bedrač, Reference Klopčič, Bedrač, Klopčič and Bedrač2015: 8).

Of course, globally, the Holocaust is a well-known and exhaustively studied issue, in contrast to the Nazi persecution of the Romani, which is referred to in various Romani dialects as porrajmos, porraimos, pharrajimos, samudaripen, kali trash (kali traš), holokosto, and more (Klopčič & Bedrač, Reference Klopčič, Bedrač, Klopčič and Bedrač2015: 9; About & Abakunova, Reference About and Abakunova2016: 1). However, this forgotten genocide of Romani people is mostly known as the porajmos. The first book dedicated to the topic was only published in 1964, by Hans Joachim Döring (Reference Döring1964); and no more than twenty articles discussing Roma and SintiFootnote 1 genocide had been published before that (About & Abakunova, Reference About and Abakunova2016: viii).

Publications focusing on the archaeological traces of Romani genocide are even rarer, as archaeological research into modern conflicts in general is a relatively new field, emerging only in the last two to three decades (Schofield et al., Reference Schofield, Johnson and Beck2002; Schofield, Reference Schofield2005; Saunders, Reference Saunders2010, Reference Saunders2012; Carman, Reference Carman2013).

The death toll amongst the Roma and Sinti is still a matter of debate and research, though an approximate estimate is between 250,000 and 500,000 (Huttenbach, Reference Huttenbach1991: 389). Contrary to popular belief, the mass murder and mistreatment of Slovenian Romani communities was not conducted only by the Third Reich, but also by antifascist and pro-communist partisans in what is now Slovenia. Legacies of these atrocities do not only survive in written historical sources, oral testimonies, and memory, but also in the archaeological record. Between 2017 and 2018, three concealed (i.e. deliberately hidden) mass grave locations have been discovered and investigated, providing evidence of crimes against civilian populations and minorities during the Second World War.

Porajmos in Slovenia

Romani people have been a part of European history from the fourteenth century onwards and were rarely seen as equal citizens in the countries in which they lived. In the area of today's Slovenia, Romani people were already legally persecuted in the Austro-Hungarian Empire during the late nineteenth century (Podbersič, Reference Podbersič and Kladnik Čoh2014: 79; Klopčič, Reference Klopčič, Klopčič and Bedrač2015: 20–22), laying the foundation for hatred towards them and their way of life in the twentieth century. Authorities were not well disposed towards the Romani, as they were considered ‘dangerous’ and alienated. These ‘criminal and asocial’ stereotypes were commonly applied to the Romani across Europe, with such attitudes reaching a peak during the Second World War, when up to half a million or more were killed during the genocide under National Socialism. Most of the victims were sent to the concentration camp (KL) of Auschwitz-Birkenau and other camps to share the fate of millions of Jews (Huttenbach, Reference Huttenbach1991). Romani from the former Kingdom of Yugoslavia were also sent to Uštica, the ‘Gipsy camp’ near the concentration camp of Jasenovac, run by the Independent State of Croatia (Klopčič, Reference Klopčič, Klopčič and Bedrač2015: 21–22).

Before 1941, around 1000 Roma and 100 Sinti lived in the area of the Drava Banate (Dravska banovina), a province in the Kingdom of Yugoslavia (consisting of today's Slovenia minus a part then controlled by Italy) (Podbersič, Reference Podbersič and Kladnik Čoh2014: 80). The Italian authorities deported seventy-eight Roma from the occupied territory of Ljubljana to the Tossicia concentration camp, as they were taken to be ‘socially dangerous’. Slovenian Romani were also held in the Gonars and Chiesanuova camps (Toš, Reference Toš, Klopčič and Bedrač2015: 36). Those from the area of Prekmurje were mostly used as forced labourers for the Hungarians or were drafted into the Hungarian army (Podbersič, Reference Podbersič and Kladnik Čoh2014: 81). Around 300 Romani from other parts of Slovenia under German occupation were sent to the Begunje (Košir, Reference Košir, Saunders and Cornish2017) and Št Vid prisons, from where they were deported to Serbia or to German and Croatian concentration camps such as Jasenovac (Podbersič, Reference Podbersič and Kladnik Čoh2014: 81; Toš, Reference Toš, Klopčič and Bedrač2015: 37). The Slovenian Institute of Contemporary History has compiled an official list of Slovenian victims of the Second World War. Amongst the deceased are 186 Romani victims, of whom ninety-three were killed by the German occupying forces (Toš, Reference Toš, Klopčič and Bedrač2015: 39).

A special chapter of atrocities and crimes against Romani people in Slovenia is represented by partisan mass executions carried out from May to July 1942, when around 160 to 190 Romani from the Province of Ljubljana (under Italian control) lost their lives; if we add the ninety-three Romani killed by the Germans, we reach a higher number than is currently given in the official list of Second World War Slovenian victims (186). Four mass executions are known from oral and written sources (Figure 1). According to these sources, the first killings took place on 10 May 1942 at Mačkovec, where around ten individuals were executed. At the same time, one can read in Krim, a wartime partisan bulletin, that partisans also killed fifty-six members of an ‘organised Gypsy spy and robber gang’ (Podbersič, Reference Podbersič and Kladnik Čoh2014: 81–82). The second killing was carried out on 17 May 1942 in Iška (forty-three individuals), the third at the end of May 1942 at Podklanec near Sodražica, where, according to a wartime newspaper, sixteen Romani were killed. The last, and largest, execution took place on 19 July 1942 at Kanižarica (around sixty individuals; Toš, Reference Toš, Klopčič and Bedrač2015: 38–39). There were also some individual executions (e.g. of Rak Rajmond in April 1942) or executions of individual families (Anon, 1942b: 1; Podbersič, Reference Podbersič and Kladnik Čoh2014: 90–91). The question that has emerged amongst historians and the Romani community in recent years is whether these crimes are part of the porajmos and thus an act of genocide, or represent war crimes or crimes against humanity. This dilemma is multi-layered and divided between different scientific fields dealing with human rights violations. At this point, the archaeological information constitutes new evidence that should be taken into account in future analyses by historians and legal and human rights scholars to determine the true nature of these crimes. The aim of this article is not to determine the designation of the crimes committed, as this falls into the context of international human rights law and the international criminal court, but to present the possibilities from new information gained through archaeological investigations of these crime sites.

Figure 1. Locations of four Romani mass executions. 1) Iška and Gornji Ig; 2) Mačkovec; 3) Boncar (Podklanec); 4) Kanižarica. The remains of the victims from Kanižarica have not yet been found (base map: https://d-maps.com/m/europa/slovenie/slovenie25.pdf).

Archaeology of Genocide, War Crimes, and Mass Death

Archaeological research of modern conflicts is a rapidly evolving sub-discipline (Saunders, Reference Saunders2012), with various research topics such as the First World War, the Second World War, and the Cold War. Amongst these, archaeological research of war crimes, atrocities, genocide, and mass death in general is a special field whose emphasis is mostly on the remains of the National Socialist period in Germany, Austria, and Poland (Sturdy Colls, Reference Sturdy Colls2012; Theune, Reference Theune and Mehler2013) or on the remains of later conflicts in areas such as Yugoslavia or Rwanda (Haglund et al., Reference Haglund, Connor and Scott2001), where mass killings and war crimes were often committed. As Theune points out, written and oral sources can sometimes show contradictory views of the past and reveal only one side of the truth. Sources for some events and places can also be quite sparse (Theune, Reference Theune and Mehler2013: 243).

Archaeological research into genocide and Nazi concentration and death camps has mostly been undertaken in Germany and Poland over the last twenty-five years, and in Austria since around 2004, at sites such as Bełżec, Chełmno, Sobibór, Buchenwald, Ravensbrück, Sachsenhausen, and Mauthausen (Sturdy Colls, Reference Sturdy Colls2012: 73; Theune, Reference Theune and Mehler2013).

Even though much has been achieved in the field of holocaust archaeology in recent years, the material traces of the porajmos were not studied by archaeologists until recently. The first project of this kind was carried out at the former Roma camp in Lety (Czech Republic) between 2016 and 2017 (Vařeka, Reference Vařeka2017, Reference Vařeka2018; Vařeka & Vařeková, Reference Vařeka and Vařeková2017). However, locations of National Socialist ‘terror and mass death’ sites are not the only places studied, as those associated with Communism and other dictatorships have also been investigated. Such is the case at Katyn, where the Soviet NKVD (People's Commissariat for Internal Affairs) committed a mass murder of the Polish elite (Cienciala et al., Reference Cienciala, Lebedeva and Materski2007; Theune, Reference Theune and Mehler2013: 246–47). Slovenia is also amongst the places where numerous extra-judicial killings took place. These were conducted by the partisan resistance movement, driven by Communist ideology. Today, more than 600 locations of mass or individual graves are known. In the post-war period between May 1945 and January 1946, approximately 14,000 Slovenians were killed alongside some 80,000 soldiers and civilians from the former Yugoslavia, mostly from Croatia. In this wave of violence and death, many German and other prisoners of war were also ‘dealt with’ in the same manner (Ferenc, Reference Ferenc2012: 8–9; Dežman, Reference Dežman, Dežman and Jamnik2017: 33).

The inclusion of archaeologists in the excavation or exhumation of the so-called concealed graves started in 2006, though three year earlier, in 2003, an ‘archaeologically comparable method of excavation’ had been used for the first time (Ferenc, Reference Ferenc2012: 18–21; Jamnik, Reference Jamnik, Groen, Márquez-Grant and Janaway2015: 169–70). Excavations at such sites are mostly undertaken under the auspices of the ‘Commission of the Government of the Republic of Slovenia for Solving the Issues of Concealed Burial Sites’ (hereafter the Commission), whose roots date back to 1990. The first exhumation was carried out in 1991, with occasional work in subsequent years. The number of excavations grew between 2006 and 2009. However, the situation changed in 2009 due to political tensions, when the Huda Jama site (probably the best-known Slovenian mass grave with 1410 individuals recovered in 2009 and 2016–2017; Košir & Leben Seljak, Reference Košir, Leben Seljak and Dežman2019a) was discovered. Consequentially, the Commission's endeavours came to an almost complete halt (Ferenc, Reference Ferenc and Dežman2019: 65, 69–75, 81–82). Government-funded work resumed in 2015, when the Concealed War Graves and Burial of Victims Act, forming a legal foundation for exhumations and reburial of the remains, was adopted. Apart from excavation at known gravesites, the Commission also coordinates recording and test trenching of new sites and erecting memorials, information boards, and so forth at known sites.

The main aim of the exhumation work is to provide an appropriate burial for the victims. All the human remains uncovered are either reburied at war or civilian cemeteries or placed in special ossuaries; the final resting place of Romani victims from Iška and Bocnar is still a matter of political and local debate. In the case of a reburial, a memorial service usually takes place. In recent times, individual bones have also been kept as samples for any potential future DNA analysis which might provide identification of individuals.

Today, only a handful of Slovenian archaeologists have years of experience of excavating wartime and post-war mass graves. Nonetheless, the Cultural Heritage Protection Act (2008) declares that conflict-related remains older than fifty years should be regarded as archaeological finds. Regardless of the legislation, there are cases where German soldiers have been reburied by a concessionaire funeral service, whose work does not include archaeologists and anthropologists, and which bypasses the Commission. Indeed, as Tuller states, ‘anyone can dig up a body’ and no special archaeological skills are required, but this does not make someone an archaeologist (Tuller, Reference Tuller and Dirkmaat2012: 158). Non-archaeological exhumations can lead to the loss of important information, as only trained archaeologists have the methodology, tools, and techniques to gather as much evidence and information as possible (Wright et al., Reference Wright, Hanson, Sterenberg, Hunter and Cox2005; Tuller, Reference Tuller and Dirkmaat2012), particularly when dealing with mass graves of twentieth- and twenty-first-century conflicts. Unfortunately, our work in Slovenia is usually dictated by financial and temporal factors. Despite everything, the excavations of Romani victims, carried out in the framework of the 2017 and 2018 yearly plans of the Commission, were conducted at the highest achievable level.

Mačkovec

The Mačkovec gravesite lies in dense woodland in the area of the the Bloke Plateau in south-western Slovenia, next to a wartime partisan camp. The partisan writer Franci Strle mentions in one of his books an encounter with the Romani near Mačkovec. The partisans captured nine Romani on 10 May 1942 and one more person on 12 May. They were all executed under accusations of collaboration with the Italians (Semič-Daki, Reference Semič-Daki1971: 233; Strle, Reference Strle1981: 271).

The existence of the graves was first confirmed by test trenching, which immediately shifted into excavations. Four individual, two double and one mass grave were discovered close to the former partisan camp. Altogether, these seven graves contained the remains of eleven individuals (Figure 2). The individual burials (individuals nos. 1 to 4) were laid tightly together, around 20–30 cm from each other. The deceased were all adult males, between eighteen and thirty-five years old. Near the neck of individual no. 2 a bullet was discovered, and individual no. 4 had an entry bullet wound on the left parietal bone. A probable bullet wound was also observed on the skull of individual no. 3. All the deceased were facing the same way and were probably undressed before execution as no buttons or other remains of clothing were found. Interestingly, leather shoes had been placed on top of the feet of individual no. 2. It may be that somebody had tried to use the victim's shoes, which did not fit and so were thrown into the grave, or perhaps the victim's shoes were exchanged for someone else's. This is plausible as there was a lack of good quality shoes in the early years of the war in Slovenian territory.

Figure 2. Overview of Mačkovec grave site. Individuals nos. 5, 5a, and 6 were in poor condition, as can be seen in the picture (photograph: M. Pečovnik, 2016).

To the east, one mass and one double grave were located. In grave no. 5, poorly preserved remains of three individuals were discovered. At first, it seemed that only two people had been buried there, but anthropological analysis revealed that the remains belonged to an adult female and two possible female children/adolescents, aged between thirteen and sixteen (individuals nos. 5, 5a, and 6). The poor condition of the bones precluded obtaining more accurate data. Amongst the remains, part of a comb, a round mirror, and a button were discovered. Close by, a double burial of adult males, aged twenty to thirty-five, was also found (individuals nos. 7 and 8). They had been put into the grave one atop the other facing opposite directions. Individual no. 7, who was killed with a 9 mm pistol, had two half-moon earrings and a flat Bakelite hairpin (Figure 3), but the sex attributes of the skeleton were male (Košir et al., Reference Košir, Leben Seljak and Rupnik2016). Nearby, another double grave was excavated (no. 7), containing the remains of adult males aged over twenty (individuals nos. 9 and 10). Inside grave no. 7, another 9 mm bullet was located, along with a trouser button from the Royal Yugoslavian Army. Near the graves, two cartridge cases and two 9 × 17 mm cartridges were found. These were mainly used for three pistols, the FN 1922, the Walter PPK, and the Beretta M1934, though also for other pistols. One of the cartridges was a dud (Košir et al., Reference Košir, Leben Seljak and Rupnik2016).

Figure 3. Earrings, flat Bakelite hairpins, and a 9 mm bullet discovered with individual no. 7.

The material evidence alone does not point solely to Romani victims. However, the finds, the presence of women, and the known historical events indicate that we are dealing with Romani victims, as mentioned by partisan writers Stanko Semič (‘Daki’) and Franc Strle (Semič-Daki, Reference Semič-Daki1971; Strle, Reference Strle1981).

The Mass Graves Sites of Iška and Gornji Ig

Less than a week after the Mačkovec executions, another massacre took place in Iška, some eight km north of Mačkovec. According to archive sources, the partisans of the Šercer battalion executed forty-two Romani and four other persons who had also been captured by the partisans. Anton Oblak (born 1933) remembered how the partisans led the captives through his village: ‘Their Romani chief was always on horseback as one of his legs was missing. Even when the partisans led them to their death, he was riding a horse, and after him was a row of gypsies with women and children […]. They proceeded onwards, all fifty of them. We did not know at the time where they were taking them or what would happen to them […]. The partisans came back after about two hours and all the villagers were at the roadside, guessing what had happened. A partisan came towards our house […]. He turned around and said “Everybody who is against us will end like that. Get ready.” That is what I heard. Then the rumours of what had happened started to spread. The partisans who killed the gypsies at Iška later boasted about this in neighbouring pubs and talked about details of the killings’ (Podbersič, Reference Podbersič and Kladnik Čoh2014: 84).

The location was confirmed by test trenching in October 2017 and excavated in November the same year. The gravesite is located near Iška, a small village south of Ljubljana. A large wooden cross marked the supposed location, but no other details about the number of graves were known before the excavation.

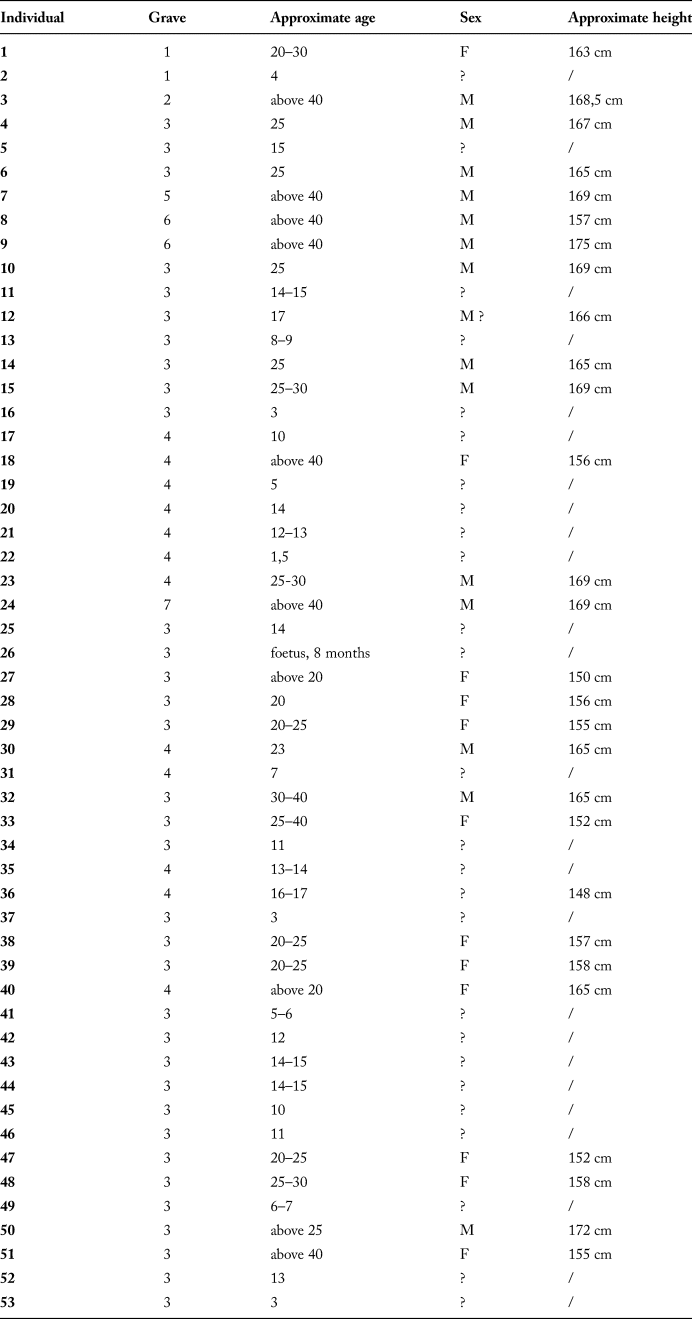

Seven graves were found close to the cross (Supplementary Figure S1). Two were mass graves, two double burials and three individual burials (Figure 4). Altogether, fifty-three skeletal remains were discovered, belonging to twenty-six adults (fourteen men and twelve women), two adolescents (fifteen to seventeen years old), twenty-four children (under fifteen years) and a foetus (Table 1). Amongst the children, ten were between one and six years old and fourteen were between seven and thirteen (Košir & Leben Seljak, Reference Košir and Leben Seljak2018). According to the oral sources on number of the victims, we were dealing with Romani families buried in the two mass graves (nos. 3 and 4), with double and single graves indicating the presence of other victims.

Figure 4. Iška mass graves. A) Grave no. 7 not yet been excavated. B) Close-up of grave no. 4. C) Close-up of grave no. 3 (photographs: M. Pečovnik, 2017).

Table 1. List of excavated individuals from Iška. F: female; M: male (after Košir & Leben Seljak, Reference Košir and Leben Seljak2018).

In a burial pit (grave no. 3) more than 4 m long and up to 1.25 m wide, thirty-four human remains were uncovered (Figure 4; Supplementary Figures S2 and S3). From the position of the skeletons, it was evident they had been thrown into the grave at random, with a complete lack of respect. Amongst the seven adult males and nine adult females (mostly aged under thirty), the remains of one adolescent and seventeen children were located. Six of them were aged between two and six, ten being older (seven to thirteen years). In the north-eastern corner of the grave, the remains of a woman and her foetus, which had a gestational age of eight months were excavated (Figure 5 and Supplementary Figure S4). The remains probably belonged to Jula Hudorovič, who, according to oral sources, was killed in Iška with her entire family (Košir & Leben Seljak, Reference Košir and Leben Seljak2018).

Figure 5. In situ remains of the foetus discovered in grave no. 3, Iška.

Less than a metre from grave no. 3, another mass grave was located (no. 4). This was smaller (2.45 × 1.18 m) and contained fewer remains (Figure 4). Altogether, twelve individuals, piled in all directions, were exhumed from the grave (Table 1 and Supplementary Figures S5 and S6). By sex and age, the victims appear to have been members of one or two families. The remains belonged to two adult females, two adult males, one adolescent (sixteen to seventeen years old), and seven children aged between one and thirteen (Košir & Leben Seljak, Reference Košir and Leben Seljak2018). In both graves, numerous small objects were discovered, clearly showing the civilian status of the victims. In grave no. 4 we found two handbags with small personal and religious items, some knife- and scissor-sharpening equipment, and spare parts for umbrellas (Figure 6). These provided insights into a Romani trade common at that time. An umbrella was also found lying on top of the human remains. Another interesting find, indicative of the viciousness of the massacre, consisted of two dogs thrown into the grave alongside the victims and their property (Supplementary Figure S7).

Figure 6. Some of the objects discovered in one of the handbags in grave no. 4 at Iška. Knife- and scissor-sharpening equipment and spare parts for umbrellas can be seen on the right.

Altogether, forty-six skeletal remains were found in the two graves. If we subtract the foetus, forty-five victims were buried, which is close to the forty-six mentioned in the partisan archive sources. The missing victim could be the ‘chief’ mentioned earlier, as none of the victims was missing a leg. As an additional five graves and seven victims were discovered at the same location, it was obvious that the place was used as a concealed burial site on multiple occasions, probably by the same partisan unit.

In grave no. 1, the remains of a twenty to thirty-year-old woman and a four-year-old child were found (Figure 7 and Supplementary Figure S8). These may have been those of Mira Lampret (born 5 December 1916) and her four-year-old daughter, executed on 5 July 1942 (Figure 8). Indeed, according to a partisan document, Mira Lampret was shot as the wife of a collaborator, together with her daughter; they were not of Romani descent (Anon, 1943). Next to them, another grave containing the remains of a forty to sixty-year-old male (grave no. 2) was found (Figure 7). Grave no. 5 held the remains of a man (at least forty years old; Figure 7); while, in grave no. 6, two men (one at least forty years old, the other possibly over sixty) were buried, alongside an umbrella, several pots, and other small items (Figure 7 and Supplementary Figure S9). The final grave (no. 7) was used for burying another c. forty-year-old man (Figure 7).

Figure 7. Individual and double burials at Iška. A) Grave no. 1; B) Grave no. 2; C) Grave no. 5; D & E) Grave no. 6; and F) Grave no. 7.

Figure 8. Burials at Boncar. A) Grave no. 1; B) Grave no. 2; and C) Grave no. 4.

With one exception, no cartridge cases were found around the graves, making it clear that the victims had been shot somewhere else and then carried or dragged to the graves. Some sources even mention that the bodies were left on the spot of the massacre and that locals subsequently buried them (Maček, Reference Maček2010).

During our research, the police gathered information on a group of females who escaped the massacre. One was later caught with her baby at the nearby village of Gornji Ig, where she was executed. We managed to locate the grave with the help of a local person who remembered that the place was called ‘at the gypsy lady’, where we found the remains of a female, probably twenty years old, buried in a shallow grave (Supplementary Figure S10). The location was used as a pasture during and after the war but was later overgrown with forest. Based on the small buttons, fragments of fabric, and a belt buckle found in the grave, she had been wearing a dress made of black and red cloth and was not wearing shoes. She also had a pilgrim badge of St Mary of Brezje, an important Slovenian religious centre, which was declared a national shrine (Mary Help of Christians) in 2000. Three 7.92 × 57 mm cartridge cases were found, alongside two fragmented bullets (Supplementary Figure S11). The victim had been shot at least three times, the last in the head while already lying in the grave. A fragmented bullet was located under the skull, the fragmentation being due to the impact with the rock on which the victim lay.

Details of both executions are known amongst local people, but some elements were probably exaggerated and applied to different locations. The killing of small children by holding their feet and hitting them against trees (memories of Anton Oblak in Podbersič Reference Podbersič and Kladnik Čoh2014: 84) has been reported for Iška and Gornji Ig and for Kanižarica, for example. While only a couple of bullet wounds were recorded on the skeletal remains and some skulls were indeed fragmented, this was most probably due to post-depositional processes and no archaeological or anthropological evidence of such execution methods was discovered. The only archaeological finding that might support such oral sources is the large number of remains of women and children, including the pregnant victim. The gravesite itself was later used as a pasture in the post-war era. At the time of the excavation in 2017 it was grassed with some trees and bushes.

The Mass Graves at Boncar

The third Romani mass grave site was excavated in October 2018 (Košir & Leben Seljak, Reference Košir and Leben Seljak2019b), when two mass graves and two individual graves were located on Boncar Hill near the village of Podklanec in southern Slovenia (Supplementary Figures S12 and S13). The location of the graves was shown to the research team by a former landowner from Podklanec. He remembered that some objects, such as shoes, parts of clothes, and personal objects, were still lying around on the surface of a steep hill in the first years after the war. This location had been a meadow and had subsequently become overgrown by trees. The remote location was not known to the public and no memorial or offerings of flowers or candles were found on the site.

Several test pits were dug by hand, all with negative results. A metal detector survey of the area also did not yield any traces of the alleged massacre. Following these negative results, a metal detector survey was carried out on a nearby ridge, where several depressions were seen on the surface. Soon, 7.92 × 57 mm cartridge cases were found around two of the depressions and on a slope above. All the cartridge cases were pre-war and made for the Royal Yugoslavian Army; their use by the partisans in the first two years of the war was not unusual. Test trenching of four such features revealed human remains at various depths. Altogether, thirty-five test pits were dug in the area.

The cartridge case distribution made clear that the victim from grave no. 3 and some of the victims from grave no. 1 had been executed at or in the grave, with others shot above the gravesite where fifteen additional cartridge cases and some cartridges were found (Supplementary Figures S14 and S15). Surprisingly, grave no. 3 contained only a few skull fragments. Later, discussions with locals revealed that one Franc Kozina (born 21 July 1909), from the nearby village of Zapotok, had been buried here and was reburied during the war. Grave no. 4 also contained the remains of a man of between twenty-five and thirty-five years old, possibly Ladislav Lesar (born 29 May 1907) from nearby Sodražica (Figure 8). Neither of the men was of Romani descent and both were killed for political reasons (Anon, 1942a). The remaining two graves contained the remains of Romani families, consisting of eighteen people (Table 2).

Table 2. List of excavated individuals from Boncar. F: female; M: male (after Košir & Leben Seljak, Reference Košir and Leben Seljak2019b).

Grave no. 1 (Figure 8; Supplementary Figure S16), which measured 2.6 × 1/1.2 m, contained the remains of nine people: two adult males (eighteen to twenty-two years old and thirty to forty years old), two adult females (eighteen years and at least thirty years), and five children (between six months and fourteen years). Amongst the victims, only one young female had a bullet wound to the head (Supplementary Figure S17), while for the others no bullet wounds were identified, even though some bullets (7.92 mm calibre) were found amongst the remains. One of the children (skeleton no. 2) had severe ante mortem or peri mortem fractures on both femurs. There was a striking similarity with the Iška burials in that two dogs with their collars still on had been thrown over a six-month-old child (Supplementary Figure S7).

The nearby grave no. 2, measuring 2.2 × 1.3 m, contained the remains of nine individuals (Figure 8 and Supplementary Figure S18): a young adult male (between twenty-two and twenty-five years old), two adult females (age could not be determined), and six children (between two and ten years old). In the southern part of the grave and part of its north-eastern corner, some disturbance of the skeletal remains was evident as some of the bones were not in situ and some, e.g. three skulls, were missing (Supplementary Figure S18). A similar situation was observed in grave no. 4, where disturbed remains without a skull were buried. According to the oral testimonies of local people from a nearby village, gathered by a research team during the excavation, a local art student (later a sculptor) had been looking for skulls in the post-war period for his study of the human body. He apparently looted two of the graves and took or destroyed four skulls in total. The individuals from grave no. 3 were most probably shot in the area above the gravesite.

The findings point towards a serious crime committed against civilians in the early years of the war on Slovenian territory. The culprits are known from historical and oral sources, and the remains of the ammunition used for the execution point to the same perpetrators. The killing of entire families, together with their dogs, again, mirrors the level of inhumanity and hate towards the victims.

Discussion

Archaeological traces of violence against the Romani population are an important material testimony of abuse and crimes that took place during the Second World War in today's Slovenia and can serve as new evidence for human rights work. One of the key characteristics of this violence is that the partisan movement was responsible for more deaths amongst the Slovenian Romani than the occupying forces (see e.g. Podbersič, Reference Podbersič and Kladnik Čoh2014). Since there are few historical sources and oral testimonies, Slovenian scholars do not completely agree on how to define these executions, as partisan authorities officially never intended to systematically kill or harm the Romani population (Podbersič, Reference Podbersič and Kladnik Čoh2014: 92; Toš, Reference Toš, Klopčič and Bedrač2015: 39). Considering this crucial fact, some see it as a war crime rather than a genocide. Nevertheless, crimes associated with mass death are also crimes against humanity or can be regarded as ethnic cleansing.

The word genocide comes from the ancient Greek genos (race, kind, category, etc.) and the suffix -cide, from the Latin caedere (to slaughter). It was coined by the lawyer Raphael Lemkin in 1944 (Conversi, Reference Conversi, Delanty and Kumar2006: 320) and describes the ‘crime of all crimes’. Article II of the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide (CPPCG, 1948) states that genocide is regarded as

‘[…] any of the following acts committed with intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnical, racial or religious group, as such:

(a) killing members of the group;

(b) causing serious bodily or mental harm to members of the group;

(c) deliberately inflicting on the group conditions of life calculated to bring about its physical destruction in whole or in part;

(d) imposing measures intended to prevent births within the group;

(e) forcibly transferring children of the group to another group.’

The crime of genocide consists of two main elements, the mental and the physical. The second does not present a problem to determine, as forensic science, anthropology, and archaeology help with gathering the physical evidence. But the mental element, ‘an intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnical, racial or religious group as such’, is usually difficult to determine or prove (UNOGPRP, Genocide, n.d.). According to Conversi, physical atrocities and murder are often seen as criteria for establishing genocide (Conversi, Reference Conversi, Delanty and Kumar2006: 326), but the specific intent is the crucial distinction. Individuals must be targeted because of their association with a particular group (whether national, ethnic, racial, or religious) and the perpetrators must commit the acts with the overall objective of destroying said group (Sirkin, Reference Sirkin2010: 499). If there is no solid evidence for such a specific intent, it can also be inferred from indirect circumstances such as the nature and systematic perpetration of the acts, the targeting of victims due to their association with the group, and the general circumstances of the crime (Anon, 1999, cited in Letnar Černič, Reference Letnar Černič and Kladnik Čoh2014: 47).

The killings could however also be seen as a crime against humanity, a war crime, or even ethnic cleansing. Crimes against humanity (murder, extermination, torture, etc.) must consist of physical, contextual, and mental elements. They must involve large-scale violence in terms of the number of victims, a large geographical area where the violence is conducted, or the systematic nature of the violence. This excludes accidental, random, and isolated cases of such acts. In contrast to the crime of genocide, there is no need to prove an overall specific intent, only a simple intent to commit a crime (UNOGPRP, Crimes against humanity, n.d.).

It could nevertheless still be argued that the murders were random or even isolated acts. These wilful killings might equally fall into the category of war crimes. According to the Rome Statue of the International Criminal Court, war crimes, in a long list of offences, also include wilful killing. War crimes can be committed in an international or non-international armed conflict, and the civilian population can be a victim in any of the cases (UNOGPRP, War crimes, n.d.). In contrast to genocide, special intent is not required to prove such crimes (Sirkin, Reference Sirkin2010: 493).

Since we already have material evidence of executions, the important questions concern the reason for these acts and whether there were specific intentions to commit the crimes. The official reason behind the executions was the suspicion of collaboration between the Romani people and the Italian forces, but no real evidence of such activities exists so far (Toš, Reference Toš, Klopčič and Bedrač2015: 38–39). A partisan encounter with the Romani at Mačkovec was described by Stanko Semič (‘Daki’), a partisan colonel and a national hero, in one of his books. The partisans thought the Romani were spying, as the Romani told them they had been exiled from the vicinity of towns and villages by the Italians (Semič-Daki, Reference Semič-Daki1971: 233). Another partisan writer stated that the same Romani group had an Italian pass for unlimited travel in the Province of Ljubljana and that they were sent there as ‘Italian’ spies (Strle, Reference Strle1981: 271). The murdered victims from Iška were captured by the partisans in a raid intended to detect ‘national traitors’ in the liberated territory around Iška and, after interrogation, all were killed. The ‘operational diary’ of the unit responsible for the mass murder has an entry for 17 May stating that a ‘Gipsy gang’ of forty-two had been executed. The Slovenian historian Podbersič states that a special proclamation (published after the executions, on 19 May 1942, and signed by the national hero Tone Vidmar (‘Luka’) and the political commissar Fric Novak) provided some kind of ‘legal’ background. The proclamation stated that partisans had authority in liberated territories, and that previous Italian laws and legislation no longer held. Due to the danger of espionage, nobody was allowed to leave the liberated territory or to travel between villages and towns in the same area. All violations were to be dealt with according to partisan law (Podbersič, Reference Podbersič and Kladnik Čoh2014: 83).

The third mass murder (Boncar-Podklanec) took place after partisans established a perimeter around the liberated territory of Sodražica. A travelling Romani group was stopped at one of the roadblocks and asked to show their permit to enter the liberated territory. As they did not possess such a document, they were arrested and put on trial, where they were found guilty of spying for the Italians. Stanko Semič wrote that this group was some kind of Italian advance party (Semič-Daki, Reference Semič-Daki1971: 271–72; Podbersič, Reference Podbersič and Kladnik Čoh2014: 85–86) and that the prisoners were handed over to ‘our platoon […] who executed the judgment over the traitors. And that's how the Italian advance party of Gypsy traitors found its end and from that time the Gypsies did not show up in our liberated territory’ (Semič-Daki, Reference Semič-Daki1971: 271–72).

The fourth and largest massacre was carried out near Kanižarica, where the mass grave of around sixty individuals remains to be found. The Romani settlement of eleven houses was surrounded by the partisan army, the village burned to the ground, and the captives taken to a partisan camp. After a couple of days, all were executed. This was done because of the cooperation of the Romani village leader with the Italians, and the statement of the Italian commissar of that area that the Romani were disciplined and loyal (Podbersič, Reference Podbersič and Kladnik Čoh2014: 87–90).

The historical background of the crimes is not to be trusted entirely, especially the accusations of espionage. The archaeological evidence presented here clearly shows that entire families were killed, regardless of the age or sex of the victims. Even pets shared the same fate, increasing the atrocity, murderous intent, and intensity of the crime. This suggests that the perpetrators may have been driven by a determination to completely erase every trace of the victims and their existence, also reflected by the burning of the settlement near Kanižarica. Yet one would think that children, especially those under five, were not ‘spies for the Italian army’ and that families with pets were unlikely to be an ‘Italian advance party’.

Ideas that executions might have been ‘preventive’ in nature have recently emerged (Podbersič, Reference Podbersič and Kladnik Čoh2014: 91). If this were the case, the probable cause would be the Romani way of life, moving from place to place and thereby compromising the partisan presence in remote areas, villages, and woodlands and resulting in the execution of entire families. The Romani were probably also seen as opportunistic because of their partly nomadic way of life and perhaps amenable to Italian payment for espionage or other information. The partisans may well have taken them to be a real threat, obstructing their political and war agendas.

The excavations of the three sites presented above have produced new information on the number, sex, and age of the victims, together with some details on the executions themselves and the events before and after them. These locations could be compared to many sites across the world in terms of their formation, concealment, and execution process. What stands out, at least in a Slovenian context, is the large number of women and, indeed especially, children. The only other site in Slovenia where remains of children have also been found to date is Krimska Jama (Krim Cave), where two foetuses, two children, and eight women were discovered amongst thirty-one victims (Kocmur, Reference Kocmur and Dežman2019).

All these archaeological findings can contribute to various scientific fields dealing with Second World War history, politics, and human rights violations. In the cases of Mačkovec, Iška, and Boncar, the archaeological remains represent new, important evidence regarding violence against the Romani population that could help with the identification of the crimes committed. This is of great significance as the partisan crimes were concealed for many years, and only after the democratic changes in 1991 could this history be seen from another perspective. These crimes, along with crimes of all totalitarian regimes in Slovenia, should be researched by human rights scholars in the future with the help of archaeological, anthropological, and historical evidence. Whether the partisan killings of Romani can be defined as a genocide is not up to archaeologists and historians to decide, but should be a task for scholars who specialize in human rights law.

Conclusions

When looking at the gravesites of Mačkovec, Iška, and Boncar as well as at the remains of men, women, children, and pets, the relevance of the issue of defining the exact nature of the crimes committed comes into question. Does it matter whether it was genocide, a war crime, or simply a series of violent events in the name of a perceived ‘greater good’ (i.e. liberation)? The results of these crimes remain unchanged, regardless of the definition, but the public awareness of the atrocities increases with precise definitions, as some still believe that these were ‘only casualties of war’ and, thus, equal to the fallen soldiers on the frontlines. When discussing the porajmos in a Slovenian context and comparing German and Italian violence with partisan violence, the archaeological and anthropological data may have a significant role to play in determining if these crimes formed part of the porajmos or not.

Archaeological traces of these mass executions represent a unique material testimony of Communist crimes against the Romani minority both in Slovenia and from a wider European perspective. The memories, historical documents, and oral sources already revealed the scale of the tragedy, but only with the remains discovered under our feet did these events become real to the public. Ultimately, we are dealing with vicious, heartless, and violent crimes, with poignant archaeological remains to prove them.

Supplementary Material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/eaa.2019.58.