Introduction: Waste Management in Roman Towns

Although discard dynamics and rubbish disposal have been a topic debated for many decades, particularly in the disciplines of ethnoarchaeology and prehistoric archaeology, attention on waste management in Roman towns has only recently become the focus of attention, especially since the early 2000s.

Fortunately we now have some major works at our disposal (Raventós & Remolà, Reference Raventós and Remolà Vallverdú2000; Ballet et al., Reference Ballet, Cordier and Dieudonné-Glad2003; Remolà Vallverdú & Acero Pérez, Reference Remolà Vallverdú and Acero Pérez2011). They constitute excellent syntheses, discussing various case studies, particularly concerning Rome, Gaul, and Hispania. Other sites scattered over the Roman world have also produced interesting and detailed data concerning discard practices and the management of rubbish; therefore, although the data clearly remain unevenly distributed, we now possess a good amount of information concerning the recycling, reuse, collection, disposal, and eventual discard of a wide range of materials which ultimately ended up as rubbish. Together with the archaeological data, historical and epigraphic sources greatly contribute to produce a more vivid picture of the processes, people, and materials involved (see in particular Liebeschuetz, Reference Liebeschuetz, Raventós and Remolà Vallverdú2000 and Panciera, Reference Panciera, Raventós and Remolà Vallverdú2000). Some studies also focus on specific aspects of refuse, such as hygiene, sanitation, and the perception of cleanliness and dirt in the ancient world (Scobie, Reference Scobie1986; Wilson, Reference Wilson and Wikander2000; Kron, Reference Kron and Lo Cascio2012), or the archaeology of toilets and the cultural aspects related to their use (Hobson, Reference Hobson2009; Jansen et al., Reference Jansen, Koloski-Ostrow and Moorman2011). Consequently, with some exceptions and uncertainties, a general model of rubbish disposal in Roman towns can be sketched out with some confidence. In many centres, complex drain grids and sewers guaranteed the efficient disposal of liquid waste; however, while the presence of drains and sewers allows us to easily follow the route of liquids, the solid waste stream is more indistinct and difficult to trace. This process probably started, in many cases, with rubbish being directly thrown out of the window, as vividly reported by Juvenal (Saturae, 3: 268–77), or simply left on the street. Some buildings were provided with cesspits and pits for the more or less temporary disposal of waste (see for instance the domestic pits recovered in the Latin colony of Cosa; Bruno & Scott, Reference Bruno and Scott1993); similarly latrinae (toilets) may have contained excreta (excrements) as well as actual rubbish (Hobson, Reference Hobson2009: 89–103). Eventually, drains and sewers also usually accommodated solid refuse in addition to liquids.

Rubbish remained within the city up to this point, but in all these cases it was then usual to remove it periodically. The existence of a local management of solid waste is indicated by both archaeological data and literary sources. Scholars still disagree on the administrative organization of this management, in particular whether it was up to private landowners or to the local authority to physically provide for the removal of rubbish (Liebeschuetz, Reference Liebeschuetz, Raventós and Remolà Vallverdú2000: 54; Panciera, Reference Panciera, Raventós and Remolà Vallverdú2000: 98–99; Nin & Leguilloux, Reference Nin, Leguilloux, Ballet, Cordier and Dieudonné-Glad2003: 160–61). Nonetheless, epigraphic sources, such as the cippus of L. Sentius (CIL, I2, 839), the so-called cippus of Cingoli (Paci, Reference Paci1983: 224–26), and the Lex Lucerina (CIL, I2, 401; Bodel, Reference Bodel1994) clearly show that public authorities made efforts to keep the urban centres clean. These sources also suggest the existence of active forms of tuitio and purgatio, that is, the maintenance and cleaning of public spaces (see in particular the Tabula Heracleensis, lines 20–76). This of course does not mean that Roman towns were not fairly filthy (Scobie, Reference Scobie1986), particularly when compared to modern standards. The street level may well have risen, but the point is that the bulk of waste was periodically removed.

In the same way as the stercorarii (literally people ‘related to excrements/dirt’) had the task of cleaning the drains (CIL, IV, 10606), other figures (perhaps the stercorarii too) were in charge of keeping the streets clean, using wagons or carts named plostra, which in Rome were allowed to circulate even during the night (Tabula Heracleensis, lines 66–67). In this case, we have to rely on written sources to inform us about a process that has not left any substantial trace in the archaeological record.

Instead, archaeological data provide valuable information on where the waste collected in this way was disposed of: several public dumps have been excavated at sites located all over the Roman world. Major case studies exist for Pompeii (Maiuri, Reference Maiuri1943: 279–81; Romanazzi & Volonté, Reference Romanazzi, Volonté and Chiaramonte Treré1986, in particular pls. VIII–X; Peña, Reference Peña2007: 279–82), Mons Claudianus in Egypt (Maxfield & Bingen, Reference Maxfield, Bingen, Maxfield and Peacock2001), Augustodunum (Autun; Kasprzyck & Labaunne, Reference Kasprzyck, Labaunne, Ballet, Cordier and Dieudonné-Glad2003: 103–04), Lugdunum (Lyon; Desbat, Reference Desbat, Ballet, Cordier and Dieudonné-Glad2003), Vindonissa in Switzerland (von Gonzenbach et al., Reference von Gonzenbach, Ettlinger and Gansser-Burckhardt1951; Ettlinger & von Gonzenbach, Reference Ettlinger and von Gonzenbach1956; Pauli-Gabi, Reference Pauli-Gabi2005), Londinium (London; Miller et al., Reference Miller, Schofield and Rhodes1986), Baelo Claudia in southern Spain (Casasola et al., Reference Casasola, González, Vicente, Jiménez, Álvarez, Sáez Romero, Remolà Vallverdú and Acero Pérez2011), Augusta Emerita (Mérida in Spain; Acero Pérez, Reference Acero Pérez, Remolà Vallverdú and Acero Pérez2011), and Tarraco (Tarragona in Catalonia; Tarrats, Reference Tarrats, Raventós and Remolà Vallverdú2000). These large mounds were preferably located outside the city walls (extra muros), near the gates and the main routes, in ditches and near rivers. They may have reached such a height that it was necessary to remove the top of the mounds to guarantee the defensive effectiveness of the nearby city walls (e.g. in the case of the Aurelian Wall; Dey, Reference Dey2011: 45, footnote 60, 166–67; see also Peña, Reference Peña2007: 279).

Organic waste may also have been disposed through simple manuring, while recycling and reuse (Schiffer, Reference Schiffer1996: 27–46) surely played an important role at different stages of the process of disposal. In fact, they should be considered structured practices (Nin & Leguilloux, Reference Nin, Leguilloux, Ballet, Cordier and Dieudonné-Glad2003: 151–52) and not occasional episodes. They affected the systemic life of both building materials (e.g. the reuse of wooden shingles and beams cited by Birley, Reference Birley1994: 90; and the reuse of other building materials in north eastern Italy during Late Antiquity noted by Cuscito, Reference Cuscito2012) and movable objects made of glass (the collection of cullet in the Roman world is well known as, for example, can be seen in the case of a barrel filled with cullet recovered from a shipwreck in Grado, Italy; Dell'Amico, Reference Dell'Amico2001), metals (e.g. the many examples of metal hoards recovered from across Europe), clay (the presence of grog/chamotte in pottery, bricks, and tiles is well known), and other materials. Often the main reason for recycling and reuse was merely economic (Barker, Reference Barker, Camporeale, Dessales and Pizzo2010), but reuse sometimes implied cultural practices connected with memory, preservation, and status (e.g. Sena Chiesa, Reference Sena Chiesa2012). In general, it is important to stress that, together with other practices (i.e. scavenging), recycling and reuse ‘picked out’ of the stream materials which eventually rejoined the system (for the reuse en masse of dumped materials, see Dicus, Reference Dicus, Platts, Pearce, Barron, Lundock and Yoo2014).

Alongside the main ‘waste stream’, surely managed by municipal authorities, other mechanisms of refuse disposal existed during the Roman period: smaller dumps connected to workshops (Ballet, Reference Ballet, Ballet, Cordier and Dieudonné-Glad2003: 224–26; Dieudonné-Glad & Rodet-Bellarbi, Reference Dieudonné-Glad, Rodet-Bellarbi, Ballet, Cordier and Dieudonné-Glad2003; Kasprzyck & Labaunne, Reference Kasprzyck, Labaunne, Ballet, Cordier and Dieudonné-Glad2003: 101–02; Nin & Leguilloux, Reference Nin, Leguilloux, Ballet, Cordier and Dieudonné-Glad2003: 152–60) or private dwellings are attested within Roman towns during their initial periods of occupation (Kasprzyck & Labaunne, Reference Kasprzyck, Labaunne, Ballet, Cordier and Dieudonné-Glad2003: 99–100), in phases of general decline or local crisis, but also at times when no evidence of deteriorating conditions is documented (Monteil et al., Reference Monteil, Barberan, Bel, Hervé, Ballet, Cordier and Dieudonné-Glad2003). In all these cases, abandoned or collapsed buildings or even whole areas presented an immediate and irresistible opportunity for quick dumping, even within an intensively occupied urban context (Jacobs, Reference Jacobs2013: 606–10). There are countless examples of this phenomenon. With respect to the reuse of Roman dwellings for dumping activities, the case of Mons Claudianus (north-eastern corner of the fort) surely represents one of the best documented contexts (Maxfield, Reference Maxfield, Maxfield and Peacock2001), while the Pythion theatre in Gortyna (Crete) is a good example of a large public building used for dumping from early on, even though the surrounding area was well settled and the city itself was far from abandoned (Bonetto, Reference Bonetto2004). This kind of secondary route for waste disposal indicates that a given amount of rubbish was more or less constantly kept within the city boundaries.

It cannot be excluded that, in some specific cases, the use of abandoned urban areas for dumping was somehow driven by local authorities; this may be the case of the Pythion theatre in Gortyna cited above. Nonetheless, we can assume that in general the more the management of the town was effective, the less this second way of disposing of rubbish kept considerable amounts of refuse within the urban area. Indeed, intra moenia (within the city walls) dumping activities are well documented in periods of urban decline and/or periods of crisis of the municipal elites, a trait which characterizes many towns in late Roman/early medieval times. The Palatine East excavations in Rome (Hostetter et al., Reference Hostetter, Brandt, Flusche, Hostetter and Brandt2009: 193–94), the sewerage system of many centres in Spain (Remolà, Reference Remolà Vallverdú, Raventós and Remolà Vallverdú2000: 118–19) and the well-studied instance of Augustodunum/Autun in Gaul (Kasprzyck & Labaunne, Reference Kasprzyck, Labaunne, Ballet, Cordier and Dieudonné-Glad2003: 103–04) are good examples of this phenomenon. Late Roman written sources, such as a declamation of Ennodius describing the city of Milan (Ennodius, Declamationes, I, 18), seem to be in agreement with the framework provided by the archaeological data.

The Impact of Ancient Waste Management Activities on the Urban Archaeological Record

The existence of more or less structured systems of waste disposal should be postulated for every settlement and necessarily these systems must have been more complex in larger towns. Indeed Vidale (Reference Vidale2004: 49) suggests that there was a tight relationship between the complexity of a given society and the complexity of its way of managing its rubbish (more or less effectively).

If rubbish disposal systems can be apprehended relatively well, the consequences and impact of this phenomenon have received less attention. Most of the works concerning rubbish in Roman settlements have usually adopted a descriptive approach rather than a problem-based line of investigation. However, thanks to the data collected and discussed to date, it is possible to move a step further and ask ourselves, for instance, what the consequences of Roman waste disposal practices were for shaping the urban archaeological record. Moreover, we can also investigate the impact of rubbish management on our own interpretation of the data from urban excavations.

This is a crucial point, as the process of rubbish disposal marks in most cases the passage from the systemic context to the archaeological context (Schiffer, Reference Schiffer1972: 157); it thus plays a key role in shaping the record which is eventually recovered and examined. Among the consequences of the existence of structured systems of waste disposal in Roman towns, the most obvious and substantial aspect is the massive movement of materials from the city to its periphery (indeed the existence of the so-called ‘occupation layers’ in Roman towns has been called into question; Matthews, Reference Matthews and Barber1993; see also Schiffer, Reference Schiffer1996: 59). The efficacy of the waste disposal system is proportional to the percentage of materials displaced out of the urban core. It could also be postulated that the more efficient the urban authorities were in keeping the city clean during a given period, the less this period would be represented by the finds recovered within the city (see Manacorda, Reference Manacorda2013: 793). Conversely, periods in which the power of local authorities was weaker may turn out to be better represented because, to put it simply, rubbish was back within the city's boundaries.

Consequently, this in/out mechanism may affect our way of looking at the economic trends observed in ancient towns, particularly if we are using quantitative analyses of artefact assemblages collected in urban areas. Could the low quantity of intra moenia artefacts datable to a given period be misinterpreted as a sign of economic crisis when in fact it was due to the effective management of urban waste? In order to test this hypothesis and investigate the actual influence of ancient waste disposal strategies on our capacity of reading the record, the urban site of Aquileia, whose development is quite well known through different sources of data, was chosen as a case study. Our understanding of the general economic history of the town is then compared to the quantitative information drawn from the material that recent open-area excavations undertaken within the urban fabric have yielded.

Aquileia: Historical Background

The long history of the Roman colony on the north-eastern Italian Adriatic can be broadly subdivided into four main periods, briefly described here.

The beginnings

The birth of the city (Bandelli, Reference Bandelli1987: 63–67; Bandelli, Reference Bandelli2003) follows the great Roman expansion towards the Po plain just after the end of the second Punic War. The colony was established in 181 bc on the North Adriatic coast (Figure 1), a strategic location from both a military and an economic point of view (see Chiabà, Reference Chiabà, Ghedini, Bueno and Novello2009 for an historical overview of the city up to the beginning of the fourth century ad and for further references). For some years, life in the city must have been quite precarious and this led the civic authorities to ask for more settlers, until a supplementum (addition) of 1500 families was eventually granted by the Senate in 169 bc. Historically we know little about the following years, except that during the Social War Aquileia affirmed its alliance with Rome, thus gaining the status of a municipium optimo iure (town whose citizens have full political rights) in 90 bc.

Figure 1. Aquileia within the context of the Roman road network. Based on Digital Atlas of Roman and Medieval Civilizations (McCormick et al., Reference McCormick2004), modified by the author.

Monumental development and military events

From the last decades of the first century bc, the available archaeological data become more substantial and complement what is known from historical sources. The city, with its forum, markets, theatre, and amphitheatre, was now a Mediterranean metropolis. Thanks to its important river port and very favourable location, Aquileia became a cornerstone of the Empire's east-west and north-south trade networks. Its strategic location also determined the city's involvement in many political and military events, from the passage of Vitellius’ troops in ad 69 to the reign of Lucius Verus and Marcus Aurelius, when Aquileia experienced its first siege and plague brought by Roman soldiers. One of the most famous episodes involving the city is no doubt the later siege of ad 238, known mostly thanks to the testimony of Herodian (τῆς μετὰ Μάρκον βασιλείας ἱστορία, 8.2.3). It is important to stress that Herodian's lines describe a city with a large population and a farmland with large-scale viticulture, a proper emporium for the goods entering Italy.

The peak of Aquileia's political role and the rise of Christianity

With the Tetrarchy, Aquileia also gained an official political role, being the headquarters of the governor of Venetia et Histria (formerly X Regio), and having its own mint from ad 294 (see Marano, Reference Marano, Ghedini, Bueno and Novello2009 for an historical overview of the city in late antiquity and the early middle ages and for further references). The early fourth century saw the rise of Christianity, which quickly found a major focus in Aquileia, as magnificently demonstrated by the famous halls built under the aegis of Bishop Theodore. Archaeological data also attest to the widespread restoration of public and private buildings, along with new constructions in the fourth century.

The fifth century and the end of the ancient city

Aquileia later became involved in long and bloody dynastic conflicts, which culminated in the decapitation of Joannes Primicerius in ad 425; but the most dramatic event in the history of Aquileia took place about thirty years later, when, after a siege which lasted for three months in ad 452, the city was eventually seized by Attila's Huns. This episode still leads to lively archaeological and historical debates about its consequences. For a long time the event had been connected with the end of urban life in Aquileia but more recently, while the destructive and destabilizing impact of Attila's passage is acknowledged, traces of continuity in urban life have also been recognized (see Marano, Reference Marano, Bonetto and Salvadori2012 and Villa, Reference Villa, Bonetto and Salvadori2012 for recent syntheses and further references).

Be that as it may, Aquileia slowly disappears from the written records of the following years; the rise of Ravenna and the fragmentation of the Empire itself surely contributed to the crisis of a town which had made Mediterranean trade its strength. Eventually ancient Aquileia came to an end; this is usually linked to the invasion of the Lombards in ad 568, when the patriarch Paul sought refuge in Grado.

Aspects of continuity and discontinuity

If we look at the whole life span of the city, it is clear that there are no signs of decline at the very least until the third century ad; even the following 150 years are unanimously considered years of growth in many respects (namely political, cultural, and artistic). A constant growth of the settlement, or at least the absence of substantial decline, is suggested by literary sources (Vedaldi Iasbez, Reference Vedaldi Iasbez2007) and by epigraphic, artistic, and architectural evidence. Even demographic studies (Lo Cascio, Reference Lo Cascio2007) do not suggest any substantial decline before the end of the Roman era and the impact of the Antonine plague, which surely played an important demographic role in the Roman world at the end of the second century ad, is still a matter of debate (Lo Cascio, Reference Lo Cascio2009: 162–64; Lo Cascio, Reference Lo Cascio2012). The good health of the city does not seem to be in doubt, in particular for the first two centuries ad (see Buchi, Reference Buchi2003: 208).

Among the available data, it is worth briefly examining the evidence provided by the architectural development of the city, which is obviously not affected by any form of displacement. If we focus on the evidence offered by the ‘neglected’ second century ad, we can appreciate the continuous refurbishment and development of the public structures and infrastructural layout of the city (see Maselli Scotti & Rubinich, Reference Maselli Scotti, Rubinich, Ghedini, Bueno and Novello2009). The forum witnesses substantial refurbishments which can be dated to the late Antonine period (Casari, Reference Casari2004), while major works in the nearby civil basilica can be more generally dated to the second century (Maselli Scotti & Rubinich, Reference Maselli Scotti, Rubinich, Ghedini, Bueno and Novello2009: 98). The dismantling of a large area in the north-western urban district, as part of the necessary works for building the great circus, is dated to the end of that century (Maselli Scotti, Reference Maselli Scotti2002; see also Basso, Reference Basso2004: 327), while in the eastern fluvial port (the core of the city's economic network) infrastructures were improved in the late first/early second century ad (Carre & Maselli Scotti, Reference Carre and Maselli Scotti2001).

Private architecture also provides examples of renovations as well as the introduction of new decorative schemes (see Clementi, Reference Clementi2005; Clementi et al., Reference Clementi, Rinaldi, Novello, Bueno, Ghedini, Bueno and Novello2009). Many triclinia (dining rooms) present floors with T and U schemes, a decoration which complied with the disposition of the dinner couches within the room, and which was particularly widespread during the second century ad; they include the triclinia of the Casa di Licurgo e Ambrosia, the Casa Sud dei Fondi Cossar, the Casa sotto Piazza Capitolo, and the Casa del Tappeto Fiorito (Ghedini & Novello, Reference Ghedini, Novello, Ghedini, Bueno and Novello2009: 117–22).

Although these elements, alone, strongly suggest that the second century ad in Aquileia was far from being a period of crisis, it is important to underline that even the absence of substantial architectural projects would not prove economic decline, since north Italian Roman towns had already been equipped with most of their monuments in the previous 150 years; and, therefore, ordinary maintenance and minor refurbishments may well have been sufficient to keep public and private buildings in use.

Despite this, a second-century ad economic crisis has been considered (Brizzi, Reference Brizzi1978: 98–99; Cipriano & Carre, Reference Cipriano and Carre1987: 486; Donat, Reference Donat and Verzár-Bass1994: 68–70), mainly on the basis of quantitative observations carried out on artefacts assemblages (namely amphorae), i.e. on portable objects. It has to be stressed that most of the assemblages examined came from intra moenia excavations and a critical evaluation of the archaeological deposits was not undertaken.

In general, such a view of second-century ad Cisalpine towns has been challenged, mainly by those studying the architectural development of the urban centres (Rossignani, Reference Rossignani2004), but this issue remains vigorously debated (see in particular Whittaker, Reference Whittaker1994 and Cassola, Reference Cassola1994). If, on the one hand, the third century ad is much more unanimously considered to be a period of political and economic difficulty, the overall evaluation of the previous century is much less straightforward.

Could underestimating the economic relevance of the second century ad in Aquileia in part be due to distortions in the archaeological record caused by ancient processes of waste disposal (in/out stream)? In order to investigate this issue I shall examine the evidence offered by an open-area excavation within the city walls and discuss the interpretation of its contexts and artefacts.

Data from an intra moenia Excavation: The House of Titus Macer

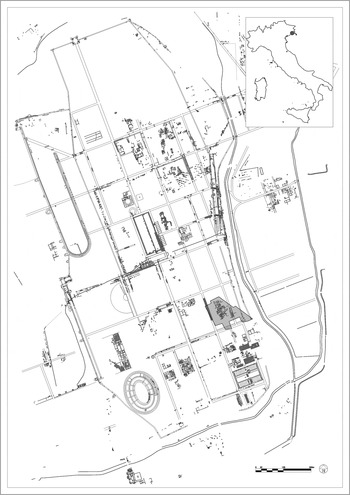

The plot named Fondi ex Cossar is located within the earliest of the city walls and just a few metres north of the famous Basilica (Figure 2). The area was investigated in several campaigns of excavation and renovation works over the last 150 years (Bonetto et al., Reference Bonetto, Bragagnolo, Centola, Dobreva, Furlan, Madrigal, Menin and Previato2012: 138–40; Madrigali, Reference Madrigali, Bonetto and Salvadori2012). New excavations were carried out by a team led by J. Bonetto of the University of Padova between 2009 and 2013 and again in 2015 (Bonetto & Ghiotto, Reference Bonetto and Ghiotto2011, Reference Bonetto and Ghiotto2012, Reference Bonetto and Ghiotto2013; Bonetto et al., Reference Bonetto and Ghiotto2012; Centola et al., Reference Centola, Furlan, Ghiotto, Madrigali, Previato, Bonetto and Salvadori2012); it was the first time in Aquileia that the central part of an insula, whose width roughly corresponds to a single residential plot, was brought to light and re-examined ‘from street to street’.

Figure 2. The area named Fondi ex Cossar (in grey) within the context of ancient Aquileia.

The plot was largely occupied by a great domus, named the House of Titus Macer. It was designed around an atrium (central court of the aristocratic house) to the west and a cryptoporticus (windowed corridor) to the east, with a row of shops fronting the eastern road (Figure 3). The new investigations produced a structural and stratigraphic sequence which is now being studied along with the finds. So far, it appears that the western part of the domus, laid out in a very traditional manner (Bonetto & Furlan, Reference Bonetto and Furlann.d.; Bonetto & Ghedini, Reference Bonetto, Ghedini and Clini2014; Centola et al., Reference Centola, Furlan, Madrigali, Previato, Álvarez, Nogales and Rodà2015), was built at an early stage, whereas a second major building phase, which involved the refurbishment of the old house and substantially lengthening and re-arranging it towards the east, most probably took place in the Augustan period or a little later. It was then that the cryptoporticus and most of the surrounding rooms were built; among them a large oecus (hall) was the main reception hall.

Figure 3. Reconstruction plan of the House of Titus Macer in the early imperial period. The ancient atrium (3) can be seen on the left, while the central part of the dwelling is occupied by a large oecus (19), whose entrance directly faces the cryptoporticus (16). The eastern part of the insula (on the right) accommodates a row of tabernae (25–30).

It seems that minor improvements, such as re-floorings (e.g. the famous mosaic portraying a hound hunting a deer; Grassigli, Reference Grassigli1998: 225–27) and the occasional alteration of a few rooms took place over the next 250 years. Conversely, some major works, including the complete re-arrangement of the atrium area, were carried out between the fourth and the beginning of the fifth centuries ad.

In this period, no dumping activities have been documented within the house; most of the artefacts were embedded in floor make-ups or other strata associated with building activities. No other layers directly connected with the daily activities carried out in the building were recovered and there were no indications (e.g. robbing, collapse of structures, activities other than domestic) that it was abandoned, even temporarily or in part.

Only the last refurbishments documented in the house seem to slightly predate the conversion of some spaces (namely the ancient atrium) to dumping activities. Indeed, the excavation brought to light many small dumps, approximately dated to the mid/late fifth century ad, located within the structures of the domus, which at this stage clearly saw a different form of occupation. The last traces of permanent occupation within the structure seem to be dated to the sixth–seventh centuries ad at the latest. After this, the occupation of the building (or of its remains) would have been sporadic, at least until the extant walls were robbed, most probably in the late Renaissance/early modern period.

Methodology

Having established the archaeological sequence in the area, the chronological data provided by the excavated artefacts must be examined to ascertain which periods are more (or less) represented. How does the chronology of artefacts fluctuate through time? Can we detect any peaks or troughs? In order to provide an answer, we need to express the information (artefacts and their dates) gathered from the whole insula.

Other than the controversial South formula (South, Reference South1972; Martin, Reference Martin, Guidobaldi, Pavolini and Pergola1998), a way of apprehending this kind of data was proposed by Nicola Terrenato and Giovanni Ricci and applied to the study of residuality in contexts from the northern slopes of the Palatine Hill in Rome (Terrenato & Ricci, Reference Terrenato, Ricci, Guidobaldi, Pavolini and Pergola1998). This method, named ‘weighted means sum’, is essentially a more elaborate form of aoristic sum (sum of all the probabilities), a technique first introduced in the field of police investigations (Ratcliffe, Reference Ratcliffe2000).

Apart from identifying residual artefacts, the technique has been used for creating ‘dating profiles’ of whole sites in spatial analysis projects (Millet, Reference Millet, Francovich, Patterson and Barker2000; Roppa, Reference Roppa2013: 104–07) and whole periods in excavation reports (Argento & Di Giuseppe, Reference Argento, Di Giuseppe, Carandini, D'Alessio and Di Giuseppe2006: 34–36). This method is a very good way of showing the cumulative chronology of artefacts and samples collected even within a single context or group of contexts. The wealth of information is maintained and presented in a synthetic way.

Nonetheless, this technique still has some shortcomings and requires correction. In particular:

-

– the graphs produced present a value on the y-axis that does not correspond to the number of artefacts; it just gives a sum of weighted means, i.e. a value of probability. This makes it more difficult to gain an idea of the quantity of material circulating in a given period; in other words, it is less comprehensible;

-

– the technique turns initial uncertainties about the dating of each artefact into some kind of certainty (but multiplied uncertainties should increase rather than decrease the overall level of uncertainty).

This last point has been discussed by E. Crema who states: ‘[…] when the input data are probabilistic, the output data should also be probabilistic. This implies that the aoristic sum could be a misleading approach, as it will obscure possible alternative time series by showing one possible dynamic which is not necessarily the one with the highest chance of occurrence’ (Crema, Reference Crema2012: 449). In the same paper, Crema focuses on variations in the temporal patterns of Jomon pithouses in Japan. He challenges the very basis of the topic and suggests a possible way out. Once the probability calculus is excluded (in our case, the number of permutations that should be performed even for small numbers of artefacts cannot be practically computed), the author suggests that we move to a simulation approach (see Lake, Reference Lake2014). Here the Monte Carlo method offers an effective tool.

This method has been applied in archaeology (besides Crema, Reference Crema2012, see Buck et al., Reference Buck, Cavanagh and Litton1996: 188–99; Crema et al., Reference Crema, Bevan and Lake2010) but, as far as I am aware, it has never been applied to the study of the chronology of artefacts recovered within a deposit, an excavation, or a whole site, although its possible use in this field has been suggested by C. Orton (Orton, Reference Orton2009: 69; for a further, alternative method, known as the triangular model, see Van de Weghe et al., Reference Van de Weghe, Docter, De Maeyer, Bechtold and Ryckbosch2007).

In our case, the basic assumptions are the same as those of the aoristic sum analysis: we have events (temporal diffusion of single artefacts), we have time blocks (5, 10, 25, 50 years), but we do not know the actual life span within the temporal range covered by the sherds we are dealing with. Ultimately, we want to look at the cumulative chronological information provided by the artefacts and examine which time blocks are more or less represented.

If we take a single event and divide it into time boxes and if we assume that each box has the same probability of ‘containing’ the actual life of a sherd, then we can randomly pick up one of the boxes (given our precarious knowledge of ancient production and distribution rates of each type of artefact, assuming a uniform distribution seems to be the more reasonable strategy; normal distributions have also been suggested: Roberts et al., Reference Roberts, Mills, Clark, Haas, Huntley and Trowbridge2012; Ferrarese Lupi & Lella, Reference Ferrarese Lupi and Lella2013; see also Millet, Reference Millet1987; Zanini & Costa, Reference Zanini, Costa, Cau, Reynolds and Bonifay2011; Poblome et al., Reference Poblome, Willet, Firat, Martens, Bes, Johnson and Millet2013). Then the process is repeated for each sherd (event), resulting in simulating a temporal pattern. Of course, one run of such a simulation is almost meaningless, but if we repeat this simulation a great many times, it acquires an increasingly higher probabilistic value. We can finally stop the analysis ‘when we start to observe a relatively good degree of convergence […] or when the standard error of our results becomes minimal’ (Crema, Reference Crema2012: 451). Plotting the cumulative result of the simulation runs, with time (divided in more or less dense boxes) on the x-axis against the simulated number of artefacts on the y-axis, the resulting graph no longer shows a single line with peaks and troughs, but a band which is wider or thinner according to the quality of the data used. Uncertainty is thus considered and formalized and the final result fits the data more accurately.

The two main problems presented by aoristic sum analysis (management of uncertainty and moving from probability to artefacts) are thus solved. The Monte Carlo method is also flexible and can be improved and modified with more a priori knowledge, in order to obtain more accurate and realistic simulations. As this method can be modelled and performed using statistical programmes, add-ons can also be modelled and automated in order to significantly reduce the time employed.

By means of graphs produced by Monte Carlo simulations, using the ‘R’ programme (R core team, 2013), I will first examine the chronological data produced by the excavation of the House of Titus Macer as a whole, and then move on to the evidence offered by two particular kinds of deposits: robber trench backfills and drain culvert fills.

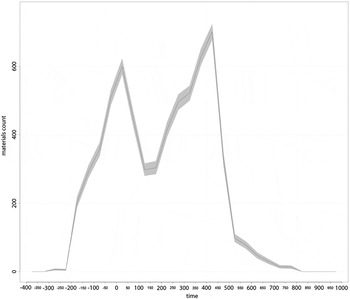

The excavation as a whole

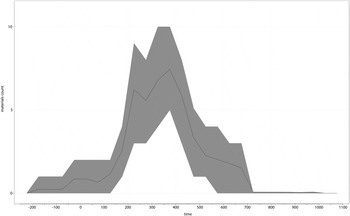

The excavation produced a total of more than 80,000 finds; among them over 13,000 were diagnostic and 6390 have been dated. The sample can therefore be considered reasonably relevant; it represents about 8 per cent of the total amount of artefacts and 49 per cent of the finds that can be reliably dated. The graph in Figure 4 shows the overall chronological distribution of these finds: two major peaks can be clearly seen around the Julio-Claudian period and between the third and fifth centuries ad. As suggested above, in the first case most of the material seems to be linked to the major building activity in the area (the complete re-arrangement of the old atrium house), while in the second case we are dealing with both building activity (earlier stage) and rubbish disposal (later stage). Incidentally, we can note that the most ancient strata have been investigated over very limited areas, thus probably resulting in some quantitative underestimation of the earliest materials of the Late Republican period. Nonetheless, in our case, this seems to be barely significant, as we are interested in the period between the middle of the first century ad and the end of the second century ad. It is indeed poorly represented in the assemblage studied, although, as has been discussed, there are no other clues in the area pointing to any falling off in this period.

Figure 4. The graph shows the chronological distribution of the finds which have been recovered during the excavation of the House of Titus Macer and which have so far been dated (6390 specimens). The time span (x-axis) has been reduced to the period between the mid-Roman Republican age and the tenth century ad. The number of items for each period is reported on the y-axis.

Different rates of residuality in different periods may have played an important role in shaping the graph. This aspect is indeed quite difficult to deal with, and I shall return to the possible role of residuality in understanding the significance of the main peaks. For the moment, if we focus on the lower part of the curve, we can only conclude that the mid-imperial period is greatly underestimated, whether finds are residual or not. It would appear to confirm the existence of some economic decline in the mid-imperial period. Nonetheless, this period is poorly documented not only in terms of artefacts, but also with respect to strata (see above). Given that there is no evidence of a temporary abandonment of the house, we can only conclude that whatever was produced within the domestic space was removed.

It seems plausible to attribute this removal not so much to a unique episode but to the everyday cleaning activities that took place in the domus (Schiffer, Reference Schiffer1996: 59, 64–72; Lamotta & Schiffer, Reference LaMotta, Schiffer and Allison1999: 21; Putzeys, Reference Putzeys, Lavan, Swift and Putzeys2007: 49; for similar trends in storage/production facilities, see Bonetto, Reference Bonetto2009: 192–97). During normal occupation of the house, simple sweeping, together with the periodical clearance of the kitchen (see Peña, Reference Peña2007: 312) and the removal of rubbish from within the domus, most probably directed a continuous flow of materials towards one of the systems of reuse/recycling or of disposal and discard which were outlined at the beginning of this article. In other words, a more or less effective and continuous set of routine activities may have prevented the formation of substantial archaeological deposits within the structures of the dwelling (and a greater part of this evidence should be reasonably sought outside the city walls, in dumps which surely existed around the urban core).

In order to exclude possible distortions due to particular formative dynamics and spatial patterning, and in order to test the hypothesis proposed here, we shall move on to more specific contexts.

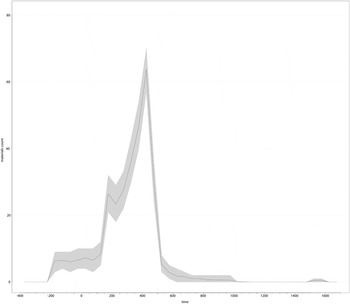

Robber trenches

Robber trenches are one of the most common features in any urban environment. They are usually related to the removal of structures and during removal parts of the nearby sediments were usually also dug up. Trenches could then have been left open or, more often, backfilled to reinstate a level surface. The easiest way to backfill the resulting empty spaces consisted of re-employing the excavated sediments and the unusable part of the removed rubble. It follows that the bulk of the material recovered (which is residual) can roughly reflect the chronology of the previous occupational trends in close vicinity to the trench. Of course this is a simplistic description of the main processes involved and actual ancient activities may have been much more complicated.

If we focus on a smaller area with strata and structures covering the whole life of the domus, such features and their assemblages can provide a good way of testing the trend observed when examining all the dated finds. In this case I chose the robber trenches located in the western part of the domus, arranged around the atrium, and I plotted the data provided by the 318 dated finds. Obviously the sample size is smaller, but the materials belong to a homogeneous group of contexts with the same depositional history and with reasonably well understood formation processes. This means that, in this case, the quality of the sample is better.

The area contained several robber trenches that followed the palimpsest of walls and rooms which defined the building. The surviving ‘chunks’ of stratification were mainly the product of the building activities related to making floors and to the late transformations and dumping episodes which involved the atrium. Most of the materials recovered in the trench backfills are, therefore, expected to come from these original deposits. All the backfills examined can be considered contemporary and they were the product of a substantially unitary group of actions, which eventually led to the systematic dismantling of the surviving walls. The robber trenches, which often precisely followed the wall foundations, were probably deliberately backfilled right after the removal of each wall section, as there are no signs of prolonged exposure: trench sides are vertical and no natural sedimentation occurred on the base of the trenches or along their corners.

What emerges from this kind of secondary deposit (Figure 5) is similar, although not identical, to what has been observed when looking at the whole excavated assemblage. The period spanning the foundation of the colony to the first half of the second century ad is barely represented. The second half of the second century ad is proportionally better represented (probably because some minor architectural work was carried out close to the trenches in this period or a little later); conversely the Julio-Claudian peak has disappeared, with again, the vast majority of material being clustered in the period from ad 300 to 500.

Figure 5. Chronological distribution of the finds recovered within the backfills of the robber trenches located in the western part of the insula. A total of 318 items were processed.

This pattern substantially reflects the depositional history of the excavated area and not a hypothetical economic trend. If on the one hand most of the Late Roman material can be reasonably linked to the last refurbishments of the house and to the later presence of rubbish, most of the earliest finds, less well represented in the graph, are attributable to the previous building activities in the area, from the initial construction of the house to the minor activities that were carried out in the following decades. No strata other than those connected to refurbishment works document the activities which took place in the domus in this period.

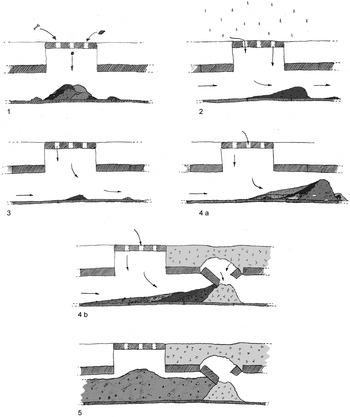

Drain culvert fills

A very similar picture emerges when looking at another kind of deposit, the fill of the drain culverts of the domus. I do not refer to the deliberate backfilling (for whatever reason) of these structures, but to the progressive infilling which occurs when material is occasionally dumped in the drain gratings and transported and deposited, together with large or small amounts of sediment, by flowing water. This last factor is connected to the presence of aqueducts and fountains or simply to rainwater (Figure 6, 1–2; see Hodge, Reference Hodge2002: 332–45).

Figure 6. A possible model for the formation of drain culvert fills: (1) discard and deposition of rubbish; (2, 3) the flow of water (aqueducts or rainwater) moves the deposited items and sediments downstream; (4a, 4b) obstacles or damage prevent the normal flow of water and permanent deposition occurs; (5) materials and sediments keep being deposited. Eventually homogenization and volume loss due to the decay of organic matter transform the deposit.

In the House of Titus Macer, as in the whole of Aquileia, the typical drain culverts are made of a base lined with tiles or bricks, two walls made of fragments of bricks, tiles, and/or sherds, and a roof with transverse Lydian bricks (c. 30 × 45 cm). Lime mortar or clay are the most common binders employed in these structures, thus creating a stable structure, whose specus (duct) was well protected from the upper sediments and from possible intrusions. Drains were generally connected, upstream, with open areas and basins, thus fulfilling their main function of transporting water. As suggested above, more or less occasional dumping on the sewer covers caused these structures to become the means of displacing rubbish. Downstream, the drains of the plot investigated here were connected to the main sewer system, which eventually transported waste water and part of the rubbish to the nearby river. Residual solid waste within the system needed to be removed periodically.

Deposits contained within drains and sewers are of great interest because of their formation processes. If a drain is regularly maintained and cleaned (see Bassi, Reference Bassi, Quilici and Quilici Gigli1997: 224), no substantial amount of deposit should form within a given section also thanks to the more or less constant flow of water (Figure 6, 3). Major sedimentation and deposition of materials could begin if the normal flow of water were prevented by the presence of obstacles downstream or because damage occurred and regular maintenance did not remove these problems. Alternatively, the absence of periodic cleaning of the culvert, in itself, (Figure 6, 4a, 4b) would lead to the accumulation of material. It is also possible that the formation of deposits within drains and sewers is owed to a shortage of water (rain water or overflow of water from aqueducts) which may deprive the system of the necessary flow. In any case, or in the case of a combination of factors, it follows that the end of hydraulic maintenance and the start of the formation of these deposits are closely connected. If deposition occurs when drains are no longer maintained, the bulk of what is recovered is formed at this stage, and when deposition within the drain stops, the formation of the deposit may be considered to have ended (Figure 6, 5). The possibility that sediments from the layers right above the culvert penetrated it seems to have been minimal, at least in the case of the House of Titus Macer, given the excellent construction of the cover. It must be stressed that the assemblages recovered in these kinds of deposits should display low percentages of residuals, since they form gradually as ‘mirrors’ of an evolving systemic context.

In sum, the examination of these contexts can cast some light on the effective maintenance of the sewer system, playing the dual role of removing liquid waste and of disposing of solid waste on a the more or less temporary basis. The contexts of this type recovered during the excavation of the House of Titus Macer present some qualitative characteristics which clearly show that they were the product of dumping activities, containing small heterogeneous fragments of artefacts, bones, shells, and considerable quantities of charcoal chunks.

From a quantitative point of view, the sort of a priori model proposed here is a good fit for the data provided by the deposits formed within the drains of the domus which were not deliberately obliterated by intermediate building activities and whose ‘life’ covers the site's sequence right up to the end of the ancient city.

Unfortunately, in this case the sample size is small (fifty dated specimens), as it was possible to investigate only small chunks of strata. More material (collected during the latest excavation campaign) has yet to be studied, but it can be advanced that the same trend is observable. The graph shown on Figure 7 displays, again, a major peak between the third and the fifth centuries ad, suggesting that, in this period, the maintenance of the drain system declined; this confirms a general decrease in the civic authorities’ handling of rubbish (at least in this part of the city). On the other hand, the period ranging from the foundation of the colony to the second half/end of the second century ad is almost unrepresented, although most of the culverts were probably built during the reign of Augustus. This suggests that substantial deposition was not allowed to occur, meaning that maintenance was effective in this period.

Figure 7. Chronological distribution of the finds recovered within the drain fills examined. A total of fifty items were processed.

Discussion

The graph illustrated in Figure 5 clearly demonstrates the tight correlation between the chronological pattern of the assemblage studied here and the depositional history of the area investigated. Peaks and troughs in the graph can be reasonably linked to activities implying the supply of artefacts and sediments (notably the laying down of floor make-ups and rubbish dumping) and, conversely, with activities connected with the removal of the products of everyday activities carried out within the building. It is worth remembering that no traces of a single, major episode of removal of material have been detected, and therefore a continuous series of minor, physically undetectable activities is the preferred explanation. In other words, if we look at the graph as a whole, it shows a good degree of correspondence with the stratigraphic and formative data collected.

If we focus on the less well represented periods, the graph illustrated in Figure 7 suggests that the lack of material dated to these periods is due to the existence of practices of regular maintenance and cleaning, which clearly must have shifted the artefacts elsewhere. Effectively, the specific formation processes of the drain culvert fills which have been examined here are closely linked to the presence or absence of maintenance activities.

The tendencies observed in the two graphs are reflected, on a larger scale, by the cumulative graph of the whole datable excavated assemblage (Figure 4). It illustrates the influence of the specific history of formation of the excavated area rather than the economic development of the site. Some material dated to the third and fourth centuries ad may be residual, given the last building activity in the area; but the analysis of the drain fills clearly suggests an early decline in the maintenance of the sewer system.

Within this framework, waste disposal seems to play a fundamental role in masking the actual economic situation in some periods. If we take into account what can be deduced from the well-documented existence of waste management systems in Roman cities (see above; Raventós & Remolà, Reference Raventós and Remolà Vallverdú2000; Ballet et al., Reference Ballet, Cordier and Dieudonné-Glad2003; Remolà Vallverdú & Acero Pérez, Reference Remolà Vallverdú and Acero Pérez2011) as well as the trends in the body of data produced by the excavation of the House of Titus Macer, the case for claiming that ancient waste management can distort, even substantially, the intra moenia archaeological record appears quite strong. This seems to be true even when dealing with a large sample of artefacts, as such a process produces a bias affecting the whole (or at least a large part) of the urban area.

What remains in the domus, i.e. those materials actually determining the trends displayed, is substantially represented by:

-

1. a low proportion of finds that escaped the rubbish disposal mechanisms;

-

2. finds which can be linked to some building activities (for instance those deposited with the sediments used to raise a floor, or in the backfill of a foundation trench);

-

3. finds which can be linked to a crisis in the management of waste.

Despite the general dearth of well-published excavations in Aquileia, particularly with respect to quantitative data, two other sets of data seem to produce a pattern consistent with that of the assemblage from the House of Titus Macer. In the case of the excavations near the forum, an economic interpretation seems to have been preferred (see above; Donat, Reference Donat and Verzár-Bass1994: 68–70); while, in the investigations of the river port (it is, stricto sensu, an extramural area but it was, however, settled as well as used for storage and commercial activities), the interpretation of the quantitative fluctuations of the pottery has been more closely linked to the architectural development of the area (Carre, Reference Carre2007). In this case, the main ‘trough’ seems to shift towards the second–third centuries ad.

Seeking further comparisons in the Cisalpine region, the case of Rimini provides a very interesting case study. In the domus of the Palazzo Diotallevi, the phase in which the building displayed the richest decorative scheme (second century ad) is the least well documented by the finds recovered (Iandoli, Reference Iandoli, Braccesi and Montebelli2006: 108–09). Similarly, in the domus Dell'ex Vescovado, the early imperial period (the phase displaying the most intensive occupation) is poorly represented by artefacts; in this case, this lack of evidence has been explicitly attributed to the disposal of waste in unexcavated areas (Mazzeo Saracino, Reference Mazzeo Saracino and Mazzeo Saracino2005: 95). Finally, the same tendency, i.e. a lack of materials dated from the second half of the first century ad to the second century ad, has also been observed in the collections of the local museum (Maioli, Reference Maioli and Rimini1980: 153).

More generally, the difficulty of dealing with quantitative data from urban sites has been well investigated in the case of the Turkish site of Sagalassos, which has been the object of careful excavation and intensive survey (Waelkens, Reference Waelkens1993; Waelkens & Poblome, Reference Waelkens and Poblome1993, Reference Waelkens and Poblome1995, Reference Waelkens and Poblome1997; Waelkens & Loots, Reference Waelkens and Loots2000; Martens, Reference Martens2005). Considerable discrepancies emerged between the datasets produced by two separate investigations (Poblome et al., Reference Poblome, Willet, Firat, Martens, Bes, Johnson and Millet2013), to the point that the researchers provocatively asked themselves how many Sagalassos-es there were. Some possible distorting factors were identified:

-

1. the use of uniform or Gaussian distributions (see above) for modelling ceramic production and distribution rates;

-

2. the use of whole datasets or of datasets with only closely dated materials;

-

3. the mathematical distribution of artefacts in different phases;

-

4. the urban architectural development;

-

5. the surface visibility of different phases.

Alongside these aspects, I think we could add the distortions caused by the displacement of considerable amounts of material through waste management strategies.

The evaluation of the volume of Roman trade is similarly largely based on quantitative data. Some biases in this field are well known: they include the different rates of survival of different goods in the archaeological record, the greater visibility of long-distance trade, the representativeness of the assemblages recovered compared to the original total, etc. (Wilson, Reference Wilson, Bowman and Wilson2009). Among the sites producing quantitative data, towns surely play an important role; consequently, the evaluation of ancient strategies for rubbish disposal may turn out to be helpful in this case too.

It is worth noting that such interpretive problems affect the whole discipline of archaeology and are not limited to the study of the Roman world. Indeed, similar issues exist in other periods and other geographical and cultural contexts. For instance, the evaluation of the fifth century bc in the Punic world is matter of a rich debate in which the use of quantitative data from different settlements plays an important role (see Bonetto, Reference Bonetto2009: 192–93, especially footnotes 561–66 for a brief synthesis and further references; see also M. Botto, P. van Dommelen & A. Roppa, in press).

Conclusions

What has been observed suggests that caution must be exercised when using the data collected within urban sites to draw conclusions about their economic trends. We should remember the importance of a strong link between the data provided by artefacts and the context and excavation which produced them.

Without a proper appreciation of the process of rubbish disposal, we may seriously underestimate the presence of goods in some periods which may have actually been a time of economic stability or even growth. Some phases may turn out to be completely, or almost completely, masked (ghost phases), while others could be substantially over-represented. This drawback can sometimes be counter-balanced, for instance, by a good knowledge of the town's architectural history. Even in this case, we should consider that phases of inactivity in construction, particularly if we are dealing with a small sample, do not necessarily imply economic stagnation or regression. Indeed, great caution should be exercised when handling quantitative data from urban sites whose overall development is poorly known from other sources of information. What if, instead of dealing with such a major Roman centre as Aquileia, whose general development is after all quite well known, we were dealing with a settlement whose history is largely unknown?

In a practical perspective, to effectively tackle the problem of apprehending the economy of ancient urban sites (consumption, import/export, production, etc.) our research agendas should target large urban dumps much more often. As has been observed, urban dumps represent the reverse of the coin whose obverse shows the intra moenia archaeological record. It follows that the investigation of extramural dumps is a necessary step for gaining a complete picture.

From a theoretical point of view, we conclude that an extra/near-site perspective is often a necessary step to better understand intra-site dynamics. Indeed in our case the distortions caused by the spatial patterning of finds are real only if we consider the inhabited area. If we consider the extra moenia surroundings, thus the ancient suburbium, as part of the site, a bias of this kind would disappear. It is interesting to note how spatial patterning (the displacement of finds) produces temporal patterning (the underestimation of the importance of certain periods and the symmetrical overestimation of other periods) and how the two are closely related.

A more general aspect that this case study addresses is related to the meaning of absence of evidence in archaeology. We know that the absence of something that can be expected may be the product of an actual absence in ancient times, or it can be the result of not being able to recover it. In our case, we are clearly observing the second alternative; moreover, the very reason for the lack of artefacts in some periods within the sample studied is caused by civic authorities being much more effective in some periods than in others. In other words, in this case, absence means that things are going well.

Although suburban dumps (which should be a priority target of future excavations) have never been investigated in Aquileia, thus preventing us from reaching definitive conclusions, we can draw some provisional conclusions for the specific case of the city.

For about four centuries, since the foundation of the colony, waste disposal seems to have been quite effective; minor quantities of materials remained within the city walls, mostly (as residual or in-phase materials) when they were part of building activities or simply because they managed to escape the disposal system (see above). As already suggested, this does not imply that the city was ‘clean’: it just indicates that periodical and effective cleaning took place.

This system seems to have experienced an early crisis from the third century ad. Indeed, if on the one hand some third- and fourth-century material may actually be residual because of the last building activities of the fifth century, on the other hand the analysis of the drain fills clearly suggests an early decline in the maintenance of the sewer system and in urban waste management. As observed at the beginning of this article, intramural dumps and the collapse of the sewer system have been documented in other towns, and often these two processes are dated to the third and fourth centuries ad.

During the fifth century, the presence of considerable amounts of rubbish within the city of Aquileia (or at least within the insula studied here) is indicated both by the quantitative analysis of the chronological distribution of finds and by the direct investigation of the strata created by dumping.

The fourth and the fifth centuries ad are, until ad 452, periods of substantial political development within the town, and one may wonder if the crucial events of ad 452 actually played a major role in the crisis of the public waste management. Even if we take into account considerable rates of residuality, quantitative data seem to suggest that, in the middle of the fifth century, the civic disposal of rubbish was already quite inefficient, thus predating the siege and seizure of the town. Moreover, this interpretation seems to be supported by the evidence for an early decline of the sewerage, whose fills show low rates of residuality. Surely, in future, improving the precision of our way of dating single artefacts, types, and classes could produce a clearer framework, thus allowing us to better evaluate the influence of more limited periods or even of single episodes, such the siege of ad 452.

At this point, the main question left is: why did a system which was very effective for four centuries collapse? Of course this decline is connected to the crisis of the whole infrastructural layout of the city, and this is a matter for wider historical discussion. In this sense, the picture proposed here can contribute to the much broader debate concerning the end of ancient towns and the development of medieval towns, including controversies over continuity and discontinuity (for a recent synthesis and further references, see Brogiolo, Reference Brogiolo2011: 207–24).

In conclusion, the study of the management of waste in the ancient world is beginning to produce a good picture of the phenomenon and it has surely much more to contribute. The case study presented here demonstrates that the topic can also be treated in a less descriptive and more active way. In particular, it could be successfully applied to the still little-studied subject of the role and impact that Roman refuse management played in shaping the urban archaeological record and its interpretation.

Acknowledgements

This article is based on a paper presented at the 2015 EAA conference in Glasgow. I wish to thank Dr Filippo Da Re and Dr Paolo Kirschner for their invaluable support with the data produced by the excavation of the House of Titus Macer. I am also grateful to all the colleagues who shared with me so many months in Aquileia and who physically pulled out from the soil the body of data which has been used in this paper; among them I particularly wish to thank Prof. Jacopo Bonetto, Prof. Andrea Ghiotto, Dr Diana Dobreva, Dr Andrea Stella, Dr Emanuele Madrigali, Dr V. Centola and Dr C. Previato. I also wish to thank Dr C. Boschetti and Dr V. Baratella for their helpful suggestions. Finally, my appreciation goes to the two anonymous referees for their precise and constructive observations, and to C. Frieman and M. Hummler for their invaluable work.