Introduction

For the sixth-century ad poet Venantius Fortunatus, ‘Quod grata lavacra nitescunt’ (‘because the gracious baths shine’) is the main reason why a certain Leontius was praised as a master builder of villae. The passage about a private villa near Bordeaux (Burdigala) underlines the continued importance of bathhouses in elite circles, even long after the Roman empire's heyday. Until recently, private baths were relatively under-researched because the academic focus was on public baths, preferably large and lavishly embellished thermae in important cities (de Haan, Reference de Haan2010: 6–8). Private baths, especially the baths in rural villae, were considered to be derivatives of the public baths, the extravagant whim of an urban elite that wished to enjoy city comforts and impress friends and guests (Nielsen, Reference Nielsen1993: 60). Renewed interest in these private facilities has pointed to the pioneering role in the development of the Roman bathhouse and bathing culture, paving the way for new architectural, technological, and decorative developments (de Haan, Reference de Haan2010: 37–38). With ever larger and more luxurious public baths in the cities, it was mainly in their country estates that the elite tried to outclass their peers with sophisticated baths. In the provinces, the luxury of private Roman-style baths was not only a sign of wealth but also implied participation in a Roman way of life (DeLaine, Reference DeLaine, DeLaine and Johnston1999: 12–13).

Intra-elite competition as a driving force in the construction of private baths has only been examined in secure urban contexts such as Pompeii (de Haan, Reference de Haan1997, Reference de Haan2010), but far less so for villae in rural settings. Finding a region with a representative sample of excavated villa baths that were in use at the same time has been a challenge, but a sizeable archaeological dataset from recent rescue excavations as well as antiquarian investigations exists in the north-western part of the Roman empire, in Gallia Belgica and Germania Inferior. Here, I shall examine how bathhouses were introduced in this region and rapidly became popular markers of wealth and a Roman way of life. I shall focus on how the size and embellishment of baths offered the elite the opportunity to compete with their peers in a region where several contemporaneous villa baths reveal similarities in plan that suggest that their owners were trying to measure up to their close neighbours. The study of such elite peer interaction networks and the way local communities engaged with something as Roman as bathing has important implications for our understanding of the Roman north-west, as it can show how complex societies with few urban centres were drawn into the Roman cultural sphere.

Geographical and Chronological Framework

The continental north-western part of the Roman empire has been somewhat overlooked in the seminal works on Roman baths. Only some of the larger public baths in Germania Inferior, such as those at Heerlen, Xanten, or Trier, were included in studies on the (mainly architectural) evolution of Roman baths in the provinces (Brödner, Reference Brödner1983; Heinz, Reference Heinz1983; Yegül, Reference Yegül1992; Nielsen, Reference Nielsen1993). The less urbanized region between the river Mosel, the North Sea, and the Seine basin yielded very few (monumental) public baths and has therefore largely remained blank. Only some of the larger villae and public baths have been summarily discussed (Grenier, Reference Grenier1960; Ternes, Reference Ternes and Chevalier1992; Coquelet, Reference Coquelet, Ochoa and García-Entero2000; Gros, Reference Gros2001). However, the region, which was administratively divided into three civitates, contains numerous villae that have been identified and excavated over the last two centuries, with important new discoveries made since the start of rescue archaeology in the 1990s. Unfortunately, the publication of the early excavations was often confined to the bulletins of local history clubs or never published. Only the villa baths in Germania Inferior have been the subject of more focused studies (Koethe, Reference Koethe1940; Deru, Reference Deru1994; Dodt, Reference Dodt and Zsolt2005, Reference Dodt2006, Reference Dodt2007).

In Roman times, our research area comprised part of the Roman provinces of Gallia Belgica (created in the last quarter of the first century bc) and Germania Inferior (detached from Belgica in the first century ad), more specifically the civitates of the Menapii, the Nervii, and the Tungri (Figure 1). In modern terms, this roughly translates as the territories of Belgium, the Département du Nord and the northern part of the Département des Ardennes in France, the cantons of Clervaux, Wiltz, Diekirch, and Vianden in the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg, the Eifelkreis Bitburg-Prüm district in Germany's Rhineland-Palatinate, and the County of Zeeland and the Province of Limburg in the Netherlands. Two important historical events delimit the Roman period for this area. It starts not so much with Julius Caesar's conquest of Gaul (beginning in 57 bc) but with the administrative reforms of northern Gaul by Augustus in the last decades of the first century bc (Brulet, Reference Brulet2008: 37). The end is traditionally dated to the withdrawal of the troops along the Rhine and along the Bavay-Cologne road in the early fifth century (Brulet, Reference Brulet2008: 262). Yet, these events are more a modern scholarly convention than strict cultural breaks. The archaeological data for villa construction only start to appear after the middle of the first century ad, after a road network had been established in the period between the Claudian and Flavian rule. The end of the Roman period is even less clear-cut, as early fifth-century events were the result of processes that were already in train during the later third and fourth century. In the second half of the third century, several Germanic raids into north-western Gaul seem to have had a severe impact on rural estates and small agglomerations (Brulet, Reference Brulet2008: 231). Hence the timespan of Roman villae considered here mainly runs from the middle of the first century ad to the end of the third or early fourth century ad.

Figure 1. Map of the study area with indication of the Roman provinces (ad 117), the three civitates, and the different types of baths. The location of the main sites mentioned in the text are labelled, while the location of those in the microregion west of Clavier are given in Figure 6. 1: Aiseau; 2: Anthée; 3: Basse-Wavre; 4: Grobbendonk; 5: Haccourt; 6: Kumtich; 7: Liberchies; 8: Nouvelles; 9: Oudenburg; 10: Tienen. A detailed map with the location of all sites can be accessed at the project website: https://bathsinbelgium.ugent.be/.

The Introduction of Roman Baths in North-Western Continental Europe

In the northern provinces, bathhouses were first introduced after the Roman conquest, whereas in the Mediterranean sphere public and private baths first emerged during the period of Greek expansion and then spread in the Hellenistic era (DeLaine, Reference DeLaine1989; Fagan, Reference Fagan2001; Yegül, Reference Yegül, Lucore and Trümper2013). The role of the army is unknown, as the contemporary sources such as Caesar's De Bello Gallico are silent on this matter and the earliest archaeological evidence of military baths in the northern provinces dates from the Flavian period (Nielsen, Reference Nielsen1993: 76). Temporary camps such as those mentioned by Caesar (De Bello Gallico 2, 18) would not have had bathhouses (Hanel, Reference Hanel, Ochoa and García-Entero2000: 23) but they may have been present in more permanent strongholds (Caesar, De Bello Gallico 4.38). Unfortunately, no such camps of the initial Roman conquest have been excavated in our study region (Brulet, Reference Brulet2008: 41–42). However, the occasional involvement of the army in the construction of civic bathhouses has been established in other parts of the Roman empire, such as in North Africa (Thébert, Reference Thébert2003: 294). As the earliest agglomerations and towns were often linked to a military presence (Brulet, Reference Brulet2008: 36, fig. 39), it is quite likely that some of the first (public) bathhouses were inspired by military baths (Nielsen, Reference Nielsen1993: 74). The first phase of the baths in the villa of Champion-Emptinne was constructed in the middle of the first century ad (Van Ossel & De Poorter, Reference Van Ossel and De Poorter1992: 201). Its plan features a remarkable circular caldarium. The shape is reminiscent of the round sweat rooms (laconica) often present in the early Roman baths in Italy (Nielsen, Reference Nielsen1993: 158). The shape persisted in the plan of military baths. Several examples have been found in Britannia and Germania Inferior, where they are dated to between the mid-first and early second century ad (Fair, Reference Fair1927: 220).

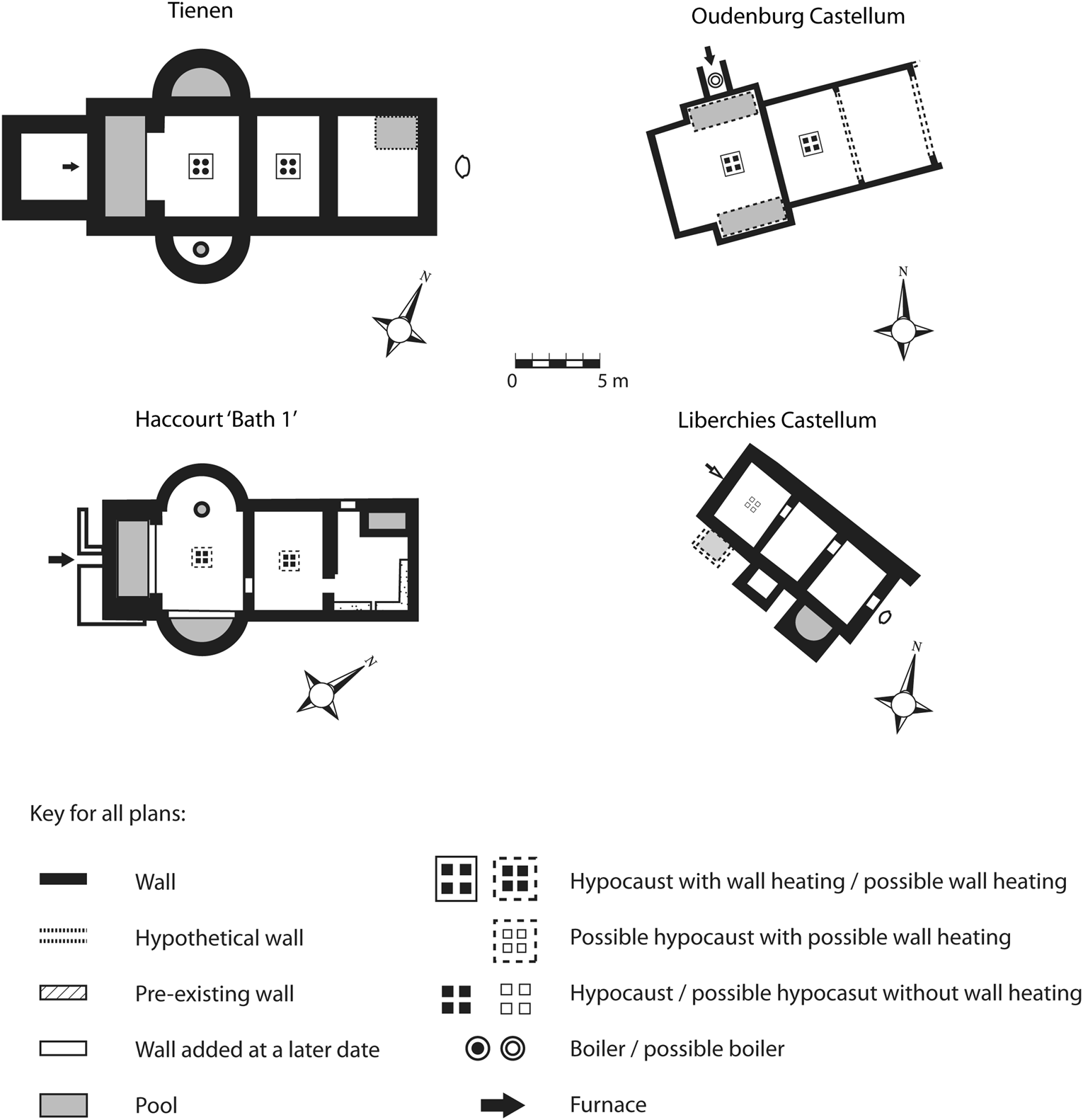

No such early military baths have been found in the three civitates in our study area, although the undated baths outside the military camp of Oudenburg did have such a circular room (Creus, Reference Creus1975: 8–9). Just outside the research area, a round laconicum was present in the first phase (Neronian or Flavian) of the baths at Heerlen (Coriovallum), which probably had a military character (Jeneson et al., Reference Jeneson, Vos, White, Jeneson and Vos2020: 172–73). Perhaps the plan of the early baths at Champion was inspired by these early military baths. The small baths in the vicus of Tienen, dated to the second half of the first century ad (Vanderhoeven et al., Reference Vanderhoeven, Vynckier and Wouters1998), as well as the first bathhouse of the initial villa at Haccourt, dated to the same period (De Boe, Reference De Boe1974), have a simple linear plan consisting of the three basic rooms, the frigidarium, the tepidarium, and the caldarium, a layout also frequently encountered in fortress baths (Nielsen, Reference Nielsen1993: 76). In the research area, the only military baths date to the fourth century ad, namely the castellum baths of Furfooz (Brulet, Reference Brulet1978), Liberchies (Mertens & Brulet, Reference Mertens and Brulet1974), and Oudenburg (Vanhoutte, Reference Vanhoutte, Pösche, Binsfeld and Hoss2018), featuring a basic linear succession of the main rooms (Figure 2). The Flavian or Neronian baths in Heerlen mentioned above also had an axial linear plan (Jeneson et al., Reference Jeneson, Vos, White, Jeneson and Vos2020: 172). Native auxiliaries who returned to their homelands after service and veteran colonists who were awarded lands in the conquered territories might also have been inspired by fortress baths when they built their own private baths (Nielsen, Reference Nielsen1993: 74; Black, Reference Black1994).

Figure 2. Plans of the vicus baths of Tienen, the first villa baths of Haccourt, and the military baths of Oudenburg and Liberchies, with key to all subsequent plans (redrawn after Vanderhoeven et al., Reference Vanderhoeven, Vynckier and Wouters1998: 143, fig. 16; De Boe, Reference De Boe1974: 18, fig. 2; Vanhoutte, Reference Vanhoutte, Pösche, Binsfeld and Hoss2018: 165, fig. 5; Mertens & Brulet, Reference Mertens and Brulet1974: pl. V).

The army may have played a role in the introduction of bathhouses, but the spread throughout the north-western provinces was driven by the local elite, who invested heavily in public baths while acting as members of local councils, as well as in private baths on their country estates (de Haan, Reference de Haan2010: 51–54). The first modest bathhouses, both public and private, appear in our research area from the mid-first century ad onwards, e.g. at Champion phase 1 (Van Ossel & De Poorter, Reference Van Ossel and De Poorter1992), Évelette ‘Clavia’ (Lefert, Reference Lefert2014), Haccourt Baths 1 (De Boe, Reference De Boe1974), Heestert (Janssens, Reference Janssens1984), or Tienen (Vanderhoeven et al., Reference Vanderhoeven, Vynckier and Wouters1998). Besides native army veterans and colonists, the native elites also enjoyed baths infrastructure. The latter were key mediators between the Roman administration and the local population, ensuring that the riches of the provinces reached the Roman treasury (Woolf, Reference Woolf1998: 33). Tacitus gives us an insight into this process in Britain: the sons of chieftains were offered a Roman education ‘and little by little the Britons went astray into alluring vices: to the promenade, the bath, the well-appointed dinner table. The simple natives gave the name of “culture” to this factor of their slavery’ (Tacitus, Agricola 21, translated by Hutton & Peterson, Reference Hutton and Peterson1914: 67). In order to climb the social ladder, local people had to adopt this concept of humanitas (translated in the quotation above as culture), that is, a civilized, Roman way of life (Woolf, Reference Woolf1998: 54–55).

Bathing played an important part in this lifestyle. From the 143 excavated bathhouses in our research area, 116 can be identified as private baths belonging to a villa (c. eighty-one per cent; Maréchal, Reference Maréchal2020). The popularity of private baths is illustrated by the number of excavated baths against the total number of excavated villa sites, taken from the archaeological inventories of the heritage agencies of Flanders and the Netherlands, and the data assembled by the ‘Mapping the civitas Tungrorum’ project of the Gallo-Roman Museum of Tongeren. Out of twenty-one villa sites in the civitas Menapiorum, five had a bathhouse (twenty-four per cent); in the civitas Nerviorum, forty-five villa sites yielded eighteen bathhouses (forty per cent); for the civitas Tungrorum, the 260 villa sites on its fertile loam soils gave an equally high number of ninety-three baths (thirty-six per cent). These percentages are of the same order (thirty-three per cent) as the villae with private baths calculated by Dodt (Reference Dodt2006: 29) for the province of Germania Inferior in the same period (first to late third century ad) (excluding the civitas Tungrorum and villae known only through aerial photography or surface survey). Considering that several villae were only partly excavated, the actual percentage of such sites equipped with baths may be even higher. Furthermore, several bathhouses were also entirely freestanding (Maréchal, Reference Maréchal2020: 160–67), indicating that the absence of baths in the main villa does not automatically imply their absence on the villa estate.

The Luxury of a Bath

Just like the urban domus, the countryside villa was not an exclusively private residence in which only the paterfamilias and his extended family retreated. The master of the house received family, friends, guests, and clients. Unsurprisingly, the house itself had to reflect the wealth and status of its owner and was designed as a statement of power. Luxuria was not a mere extravagance, it was a ‘social necessity in a highly competitive society’ (Wallace-Hadrill, Reference Wallace-Hadrill1988: 45). A large and lavishly decorated private baths complex was luxury par excellence. Several ancient authors make clear that the private baths of Roman villae were not exactly private, at least not in the modern sense of the word. ‘I will give the order to heat the baths’ wrote Cicero to his friend Atticus when hearing of his visit (Cicero, Letters to Atticus 2.3). Like public baths, private baths were to be used in company, such as family, friends, or colleagues. Preparing the baths when receiving visitors was a sign of hospitality. Pliny the Younger even rejoices in the fact that his villa lay close to a small village with three public baths to which he could take his guests when his private baths could not be heated in time (Pliny, Epistulae 2.17.26). It was expected of a good host to have the baths ready and private baths became real showpieces, showcasing the wealth of their owner. In his letters, Seneca deplores the abundant luxury of baths compared to the basic bath used only for washing by Scipio Africanus (Seneca. Epistulae 86.6): ‘But who in these days could bear to bathe in such a fashion? We think ourselves poor and mean if our walls are not resplendent with large and costly mirrors; if our marbles from Alexandria are not set off by mosaics of Numidian stone, if their borders are not faced over on all sides with difficult patterns, arranged in many colours like paintings; if our vaulted ceilings are not buried in glass; if our swimming-pools are not lined with Thasian marble’ (translation by Gummere, Reference Gummere1920: 313). Similar references to the elite investing a fortune in the embellishment of private baths are found in Martial's Epigrams (9.75; 10.79). Still in the fourth century, Ausonius (Mosella, 335–48) dedicates an entire poem to the luxurious baths of a villa along the river Mosel.

The passage by Ausonius reminds us that most authors wrote about the Italian heartland, and that we are far less well informed about the north-western provinces. Fortunately, archaeological remains of villa baths are omnipresent in this part of the empire, even more so than public baths (Maréchal, Reference Maréchal2020). Several of these villa baths clearly surpassed their basic hygienic function and seem to have been constructed to impress. Unlike the modest baths of the first half of the first century ad, some villa baths of the second and third century were large facilities with several heated rooms. The luxurious baths of the villae at Basse-Wavre (Dens & Poils, Reference Dens and Poils1905), Champion (phase 3; Van Ossel & De Poorter, Reference Van Ossel and De Poorter1992), Gesves (phase 2; Lefert, Reference Lefert2008), and Haccourt Baths 3 (De Boe, Reference De Boe1976) are larger than some of the (early) public baths in small centres such as Grobbendonk (De Boe, Reference De Boe1977), Macquenoise (Brulet, Reference Brulet1985), or Tienen (Vanderhoeven et al., Reference Vanderhoeven, Vynckier and Wouters1998) (Table 1).

Table 1. Comparison of the sizes of villa baths and public baths in the research area.

Unsurprisingly, a look at the villae to which the baths belong reveals that these were the larger and more luxurious residences: for example, Haccourt comprises some 4900 m2, Basse-Wavre c. 1400 m2, and Champion and Gesves each cover a minimum of 800 m2 (Figure 3). Conversely, the small and very simple baths at Évelette ‘Clavia’ seem to have belonged to an estate where the main building was built in perishable materials, following vernacular traditions (Lefert, Reference Lefert2014: 238–40). Together with the cellar, it was the only element on the estate to have been constructed in stone. But even the owner of this very modest and still very non-Roman farm invested in this Roman luxury, possibly at an early stage (perhaps in the late first century ad). Similarly, the rather modest villa of Bierbeek, covering an area of some 530 m2, had very basic baths (c. 36 m2) consisting of a single heated room (De Clerck, Reference De Clerck1987). Similar examples of simple baths in the north-western frontier region can also be linked to villae rooted in a vernacular building tradition and with a local material culture, possibly indicating that the local elite invested in this Roman luxury but without building all the traditional rooms (cold, tepid, and warm rooms) and hence not fully adopting the underlying bathing culture (Maréchal, Reference Maréchal2020). The preference for a hot bath in the cold North should not come as a surprise, as Tacitus already noted in Germania (22.1): ‘lavantur, saepius calida, ut apud quos plurimum hiems occupat’ (‘they wash, usually in warm water, since winter bulks so large in their lives’; translated by Hutton & Peterson, Reference Hutton and Peterson1914: 165). This, however, does not mean that smaller baths automatically belonged to an elite with a native background and the larger baths to Roman colonists. Seneca (Epistulae 86.7), even reminds us that it was especially freedmen who invested heavily in their baths ‘merely in order to spend money’ and presumably to present themselves as sophisticated and Roman.

Figure 3. Plans of the villae of Basse-Wavre and Haccourt (second villa) with indication of the baths (redrawn after Dens & Poils, Reference Dens and Poils1905: pl. XIII; De Boe, Reference De Boe1974: 28, fig. 10).

The increasing importance of private baths can be deduced from the fact that several villa baths survived for several generations and were (significantly) enlarged over time, as at Champion, Gesves, Kumtich (Cramers, Reference Cramers and Thomas1984), Meslin- l’Évêque (Deramaix & Sartieaux, Reference Deramaix and Sartieaux1994), or Haccourt Baths 3 (Figure 4). Apparently, the original bathhouse was deemed too small, too old-fashioned, or too modest and the master of the house was prepared to invest considerable funds in larger, more luxurious, and better equipped baths. In the case of Champion (phase 3) and Haccourt Baths 3 (phase 2), a heated swimming pool (piscina calida) was even added. Such an infrastructure was rare, even in public baths (Manderscheid, Reference Manderscheid, de Haan and Jansen1996: 110). In other villae, the original bathhouse was complemented by new, often freestanding, larger baths complexes, e.g. in Aiseau (Kaisin, Reference Kaisin1878), Miécret (Materne, Reference Materne1969), and possibly Mont-lez-Houffalize ‘Fin de Ville’ (Meunier, Reference Meunier1964) (Figure 5). It seems that in all these cases, the baths were being used at the same time, possibly suggesting a differential use, with the integrated baths reserved for the inhabitants and perhaps larger familia, and the freestanding baths used when receiving guests (de Haan, Reference de Haan2010: 129–30). In Merbes-le-Château, the first small baths, integrated in the villa, fell out of use when larger freestanding baths, later connected to the villa by a corridor, were constructed (Authom & Paridaens, Reference Authom and Paridaens2011). Similarly, the first baths in Kumtich were replaced by larger and more luxurious baths. Equipping the villa with larger baths may have signalled increased wealth and power, but may also have been a way of leaving a mark on the villa for posterity, as ‘potent symbols of family continuity’ (Bodel, Reference Bodel1997: 11).

Figure 4. Plans of the baths of the villae of Champion and Gesves showing the gradual increase in size (redrawn after Van Ossel & De Poorter, Reference Van Ossel and De Poorter1992: 202, 208, 213, fig. 4, 9, 14; Lefert, Reference Lefert2008: 201).

Figure 5. Plans of the villae of Aiseau and Miécret with indication of the baths (redrawn after Kaisin, Reference Kaisin1878: pl. II; Materne, Reference Materne1969: 80).

The taste for a splendid interior described by many ancient authors is confirmed by the archaeological remains, even if the buildings’ poor state of preservation and a high degree of spoliation impede a thorough comparative study. As baths were one of the social hubs within villae (Ellis, Reference Ellis2000: 160–63), it is no coincidence that decoration such as wall paintings, mosaic, or opus sectile floors, all relatively rare in our research area (Brulet, Reference Brulet2008: 150–52), are mainly found here. Wall paintings in villae seem to have been reserved for large reception rooms, dining halls, and the baths. Examples were found in several such baths, even if few patterns could be reconstructed. Floral patterns were found in Belgium in the baths at Boirs (Peuskens & Tromme, Reference Peuskens and Tromme1979), Hamois (Van Ossel, Reference Van Ossel1981), Montignies-St-Christophe (Van Bastelaer, Reference Van Bastelaer1891a), Neerharen-Rekem (De Boe, Reference De Boe1982), and Thirimont (Van Bastelaer, Reference Van Bastelaer1891b), and in Germany at Oberüttfeld (Rhineland-Palatinate; Faust, Reference Faust1999), while figurative depictions are known from the baths of Melsbroek (Galesloot, Reference Galesloot1859) and probably Hoogeloon (Hiddink, Reference Hiddink2014). In Grumelange, paintings imitating marble were found in the frigidarium (Malget & Malget, Reference Malget and Malget1912).

Mosaics appear even more exceptionally in our research area. They were present in large villae (over 500 m2) with large baths, at Anthée (Del Marmol, Reference Del Marmol1877), Basse-Wavre, Gerpinnes (De Glymes et al., Reference De Glymes, Henseval and Kaisin1875), Haccourt, Liège (Otte, Reference Otte1990), Limerlé (De Maeyer, Reference De Maeyer1940: 202–03), Modave (Anonymous, 1896), and Nouvelles (Leblois & Leblois, Reference Leblois and Leblois1968). In the villae of Ways and Angre, mosaics were found but no bathhouse has yet been identified (Brulet, Reference Brulet2008: 152). Mosaics with geometric patterns were found in Baths 1 and 3 at Haccourt, Saint-Jean-Geest (Remy, Reference Remy1977), and Baths 2 at Kumtich. Opus sectile floors, often a pattern of black and white lozenges, were found in the baths of Anthée, Boirs, and Boussu-lez-Walcourt (Bayet, Reference Bayet1891). Even in this northern part of the Roman empire, some baths were embellished with imported marbles, such as the Numidian giallo antico (yellow spotted or veined marble) in Nouvelles. As for the large baths of Bruyelle, several fragments of imported stone were found, including Numidian giallo antico, Greek red and green marbles (porfido rosso and porfido verde di Grecia), and unspecified white marbles from the Mediterranean (Ansieau & Bausier, Reference Ansieau, Bausier, Bausier, Bloch and Pigière2018: 260). Nevertheless, most decorative stones seem to have been quarried locally, labelled ‘Belgian marble’ in antiquarian excavation reports. As for flagstones and plinths, they are present in numerous villa baths, and not only in the more luxurious examples (e.g. at Aiseau, Anthée Baths 1, Basse-Wavre, Bois-et-Borsu (De Maeyer, Reference De Maeyer1940: 133), Champion, Gerpinnes, Meerssen (Habets, Reference Habets1871), Melsbroek, Neerharen-Rekem, Nouvelles, or Villers-le-Bouillet (Geubel, Reference Geubel and Balon1938)). Unfortunately, few provenance studies have been carried out to establish the location of the quarries. At least for some villae in this part of Gaul, Seneca's comment about the luxury of private baths seems accurate.

Competition at Work

The literary evidence and the archaeological remains show that the elites tried hard to impress their peers with large, well-equipped, and lavishly decorated baths on their villa estates. To see this ‘competition’ at work, a microregion with a number of contemporaneous Roman villae equipped with baths within a close range of each other was chosen. Establishing their date of construction, rebuilding, and abandonment proved to be a challenge, and the reliability of the early excavation data was sometimes questionable, with unclear plans and little attention paid to different phases within a building. Nonetheless, our sample area includes ten villa sites with baths within a radius of ten kilometres west of the vicus at Clavier-Vervoz in the Roman civitas Tungrorum in the present-day Belgian province of Namur (Figure 6). The villae are located on stony loam soils with favourable natural drainage, often on gentle south-facing slopes dominating a stream. All sites were apparently occupied during the second century ad (Table 2).

Figure 6. Map of the microregion west of Clavier with location of the villa sites (life span in brackets) (background OpenStreetMap; EPSG:31370 – Belgian Lambert 72).

Table 2. Date, baths size, pool size with maximum numbers of bathers and location of the baths in the microregion west of Clavier compared to the size of the main villa building. U: unknown, F: freestanding, I: internal, A: attached.

If we include villa sites in this region without any remains of a bathhouse, only one site can be added, at Haltinne. Since it has not been fully excavated (Brulet, Reference Brulet2008: 535), it is possible that (freestanding?) baths have simply not been found. The fact that almost all villae had baths clearly indicates their importance for their owners, as part of the standard (and expected) facilities. A comparison, when possible, of the size of the baths and that of the villa (ground floor in its final phase) shows that the baths could make up between five and fifteen per cent of the surface (Table 2). Except for the baths at Bois-et-Borsu, of which only one pool and one heated room were excavated (De Maeyer, Reference De Maeyer1940: 133), most sites have at least a basic plan usable for comparison. The plans of the baths of Évelette ‘Résimont’ (Willems, Reference Willems1966) and Miécret Baths 1 (Materne, Reference Materne1969) are very similar, consisting of a frigidarium with piscina and an adjacent caldarium with two alvei (hot pools) at right angles to each other (Figure 7). Furthermore, both baths are integrated within the villa and are roughly the same size. The plans of the baths of Flostoy (Lefert, Reference Lefert2015), Hamois (Van Ossel, Reference Van Ossel1981), Haillot (Lefert, Reference Lefert2002), and Modave are also similar (Figure 8), consisting of a simple linear succession of frigidarium, tepidarium, and caldarium. At Modave and Flostoy, the caldarium and tepidarium were only separated by a thin wall at ground level, the hypocaust being one continuous space. In all baths, the caldarium has one alveus on the axis of the building and one perpendicular to it. The piscina is also perpendicular to this axis and parallel to the perpendicular alveus. Only at Modave does the piscina lie on the main axis. All four baths are roughly of the same size and were later additions to the villa. The baths of Gesves (Lefert, Reference Lefert2008), originally freestanding, are comparable in extent and plan to those of Flostoy, Haillot, Hamois, and Modave, the difference being that its caldarium only had one alveus on the axis of the building. The first phase of the baths in Champion, possibly also freestanding, occupies a similar surface area but has a different plan (Van Ossel & De Poorter, Reference Van Ossel and De Poorter1992). When the baths at Gesves and Champion were enlarged, and attached to the villa, their extents increased to about 250 m2.

Figure 7. Plans of the villa baths of Miécret (Baths 1) and Évelette ‘Résimont’ (redrawn after Kaisin, Reference Kaisin1878: pl. II; Willems, Reference Willems1966, general plan).

Figure 8. Plans of the villa baths of Flostoy, Haillot, Hamois, and Modave (redrawn after Lefert, Reference Lefert2015: 271; Lefert, Reference Lefert2002: 244; Van Ossel, Reference Van Ossel1981: 134, fig. 96; Anonymous, 1896: 181, fig. 1).

Not only do baths with similar plans occupy comparable surface areas, but the size and shape of their pools are also similar (Table 2). Assuming that each bather would require around 1 m2 in a pool, the piscinae of Miécret Baths 1 and Évelette ‘Résimont’ could accommodate two bathers simultaneously, while those of Flostoy, Haillot, Hamois, and Modave could have held between three and six. As for the piscinae of Champion and Gesves, five people could have used them at the same time. The alvei, which are often poorly preserved due to the collapse of the hypocaust, could each accommodate one or two persons, indicating that in most caldaria three or four people could bathe at the same time. Because the water of the alvei had to be heated in boilers first, unlike the piscinae which could be fed directly by an aqueduct, the size of the alvei was rather modest, even in larger baths with large piscinae (Manderscheid, Reference Manderscheid and Wikander2000: 494).

We must nevertheless be careful when interpreting similar plans as evidence of one building influencing another, or the construction of several buildings being owed to the same architect or contractor. The simple linear plan is the easiest way of connecting the basic rooms of a Roman bathhouse and allows for a single furnace to heat both the caldarium and the tepidarium. The location of an alveus above the furnace also ensures the maximal use of direct heat. The similarity in plans may well be the logical result of adding a basic bathhouse to one side of an existing villa. It is, however, not inconceivable that villa owners in the same region used the same professional ‘baths builders’, especially in a region with few central places. Literary sources pertaining to Italy indicate that rich proprietors contacted fabri aedium (‘builders’), who showed them different plans on parchment to choose from (Aulus Gellius, Noctes Atticae 19.10.1–3). The passage by Venantius Fortunatus quoted at the start of this article also underlines the role of the architect in the construction of baths.

Further similarities in building techniques may point to the same builders but can hardly be considered hard evidence. In the similar baths of Modave and Flostoy, the only hypocaust of the baths was probably separated at room-level into two rooms (caldarium and tepidarium) by a thin wall, as suggested at Flostoy by a line of pillars constructed of stone instead of tiles (Lefert, Reference Lefert2015: 271). The piscinae of both bathhouses were also clad with similar tiles. In Miécret Baths 1 and Évelette ‘Résimont’, some hypocaust pillars were made of limestone monoliths (Willems, Reference Willems1966: 16; Materne, Reference Materne1969: 81). Even if the use of such monoliths as hypocaust pillars is not extraordinary in itself (Adam, Reference Adam1984: 290; Schiebold, Reference Schiebold2010: 14–16), these are the only two known examples in our research area. In the villae of Leignon (Hauzeur, Reference Hauzeur1851) and Maillen ‘Sauvenière’ (Mahieu, Reference Mahieu1892), located some fifteen kilometres apart and with baths of similar plan, tiles with the same manufacturer's stamp (HAMSIT) indicate that the builders of these two baths were supplied by the same manufacturer. The occurrence of the same stamp on different villa sites is not uncommon in our research area. Several tile production centres, all with their own stamp, seem to have supplied the villae and local centres with ceramic building materials (Brulet, Reference Brulet2008: 208). The decoration of the baths was unfortunately too damaged to make any links between sites.

Conclusions

Contrary to the picture emerging from most general studies on Roman baths, the north-western continental part of the empire was not a region in which Roman baths and bathing habits were rarely practiced. With so few cities and secondary centres present, it was mainly the rural elite that invested in bathhouses. These were certainly not restricted to the largest and most luxurious villae: from modest buildings to the grand estates that could rival with those in Italy, villae were equipped with this typically Roman luxury. For early villa sites with a local material culture and with strong roots in vernacular architecture, constructing Roman baths could even be a cultural statement, demonstrating the adoption of, or at least familiarity with, a Roman way of life.

By the second century ad, when Roman rule was well established and Roman culture had spread widely, some villa owners were prepared to invest important sums to expand, embellish, or rebuild their private baths. Such conspicuous spending can be understood within the framework of intra-elite competition, revealing a real concern for displaying wealth and emphasizing social status, but also leaving a mark on the family legacy. It is not easy to identify such competition among local elite networks in the archaeological record but the sizeable dataset of excavated villae in our research area has made it possible to define a small sample area with relatively numerous villa sites, almost all equipped with baths. As all sites were occupied roughly at the same time, overlapping in the second century, a comparative analysis shows that baths of equally large villae were not only similar in size, but also in plan.

Competition should perhaps not necessarily be understood in the sense of one villa owner trying to outshine his neighbour with larger and better baths, but more in the sense of ‘keeping up with the Joneses’. The fact that ten out of eleven villae within a ten-kilometre radius west of Clavier had a bath complex, compared to the twenty-four to forty per cent baths-villa ratio in our research area, could indicate that the villa owners in the region all tried to match a certain level of wealth. In this rural area devoid of cities or other central places, it is not unthinkable that they may even have used the same builders, resulting in similar plans and building techniques. Even in this poorly urbanized part of the empire, bathhouses seem to have accompanied a Roman way of life, reminding us that bathing was not the exclusively urban phenomenon modern scholars sometimes present it to be. Baths played an important role as social hubs in a region with few large settlements, cementing local peer interaction networks and contributing to the adoption of new social practices and ideas into local cultures, but possibly also creating social exclusion among the less wealthy. Furthermore, the many villae equipped with such a typical Roman luxury could imply that the north-western part of Gallia Belgica and Germania Inferior was not primarily drawn into the Roman cultural sphere through cities, but through a network of villa-based elites who governed these rural regions.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Research Foundation Flanders (FWO) under Grant 12I9619N. The author would like to thank Wim De Clercq (Ghent University) for commenting on earlier drafts of this article.