The Maritime Paradigm

The production of rock art flourished during the Bronze Age in southern Scandinavia, where images of watercraft were among the most prominent motifs. Their distribution extended across Denmark, Norway, and Sweden and often focused on the sea. Sometimes they were made at ideal landing places or locations that would have been visible from the water, and many panels depict humans, animals, boats, and metal artefacts of the kinds imported to Northern Europe. The relationship between rock art and long-distance exchange has been a theme of recent research, which has largely concentrated on representations of ships or boats (Ling, Reference Ling2014; Skoglund, Reference Skoglund2016: 65–78, 2017; Ling et al., Reference Ling, Earle and Kristiansen2018).

Recent work on coastal rock art has established a ‘maritime paradigm’. It depends on two important observations: the ship is often the dominant image in groups of motifs on a rock art panel, and many of the decorated surfaces were near the water's edge (Nordenborg Myhre, Reference Nordenborg Myhre2004; Coles, Reference Coles2005). Johan Ling (Reference Ling2013, Reference Ling2014) has shown that many sites in the World Heritage area of Bohuslän in western Sweden were located on the coast when they were made, although many of them are now in areas where the sea has retreated since the Bronze Age. His analysis combines several separate features: the locations of the panels, the contents of the pictures, and the activities of the people who created them. Ling (Reference Ling2014) suggests that vessels from various destinations gathered at aggregation sites where rituals—including the making of images—took place. Such locations would have played a significant role in trade and long-distance travel: both are vital components of Bronze Age societies.

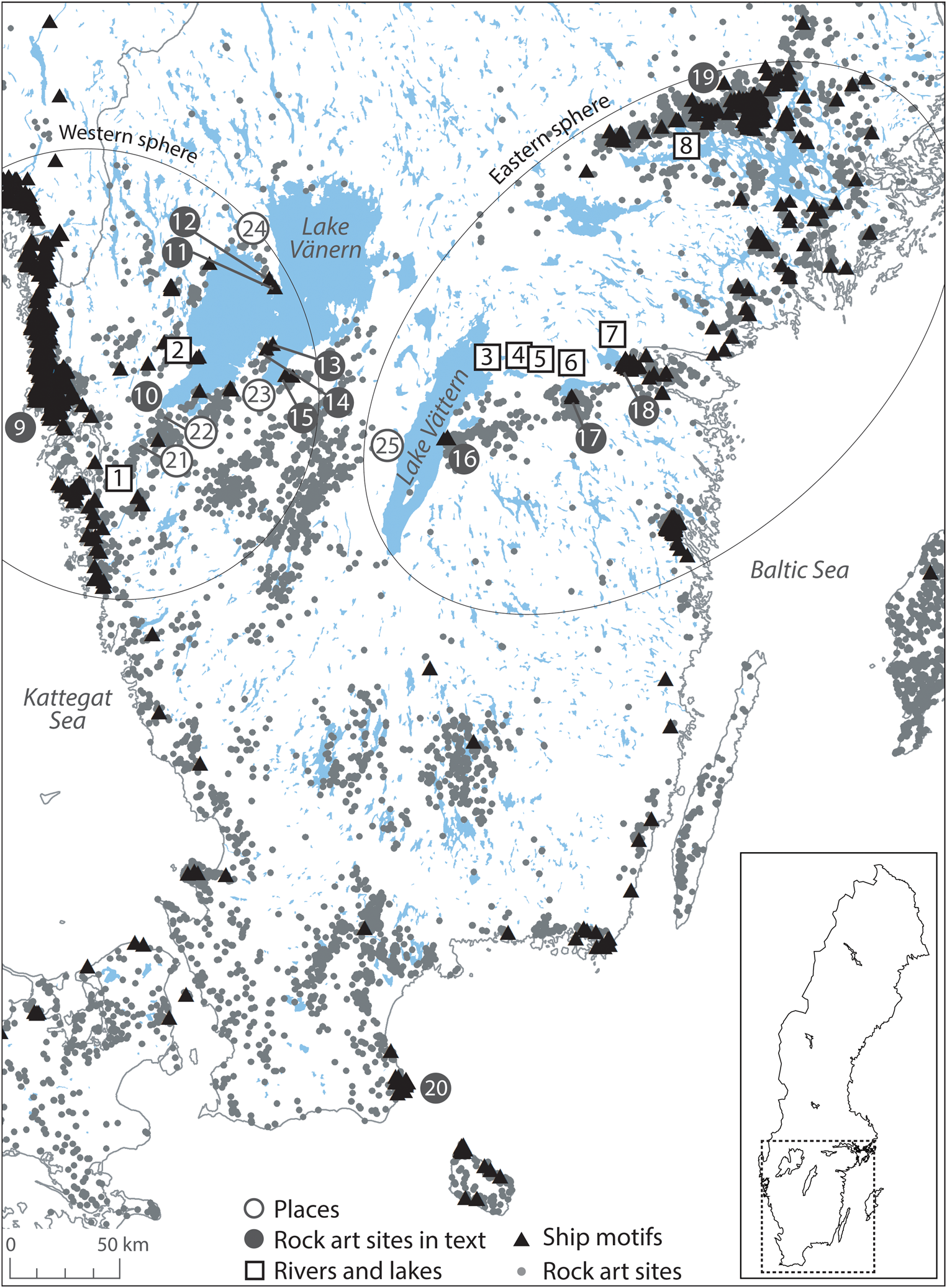

The evidence from other coastal regions supports Ling's arguments for the maritime nature of Bohuslän's rock art (Figure 1, no. 9). In Uppland (Figure 1, no. 19), on the east coast of Sweden, the importance of Lake Mälaren (which in the Bronze Age was not a lake but a bay connected to the sea; Figure 1, no. 8) suggests the same interpretation (Ling, Reference Ling2013). The rock art around Simrishamn (Figure 1, no. 20) in south-eastern Sweden is equally near to the coast (Skoglund, Reference Skoglund2016)—these sites may have been visited by seafarers from the eastern Baltic or Denmark. The rock art in coastal areas has recently been studied according to the maritime paradigm, but similar images of ships extend into inland areas and are less often discussed. Can they be interpreted within the same framework?

Figure 1. Map of rock art sites (dots), rock art sites with ships (triangles), rivers and lakes (squares): 1) Göta älv; 2) River Dalbergså; 3) Motala ström; 4) Lake Boren; 5) Lake Norrbysjön; 6) Lake Roxen; 7) Lake Glan; 8) ‘Lake’ Mälaren. Rock art sites mentioned in the text (black circles): 9) Bohuslän; 10) Bolstad; 11) Eskilsäter 7; 12) Eskilsäter 39; 13) Otterstad 234; 14) Otterstad 101 & 153; 15) Husaby 110; 16) Hästholmen; 17) Gärstad: Rystad 49, Rystad 248; 18) Norrköping; 19) Uppland; 20) Simrishamn. Places (white circles): 21) Lilla Edet; 22) Stora Edet (Trollhättan); 23) Kållandsö; 24) Värmlandsnäs; 25) Hjo. The eastern and western spheres are also shown.

This article focuses on the inland rock art associated with Lake Vänern in western Sweden, and the lakes and watercourses in the east of the country extending from Norrköping (Figure 1, no. 18) to Lake Vättern. In it, we examine the representations of watercraft and their siting in an attempt to work out the relationship between inland and coastal rock art. In addition, we discuss the rock art around the lakes in relation to major European networks, the Baltic network and the Atlantic network, and how these changed through time.

Inland and Coast, East and West

Inland rock art: Lakes Vänern and Vättern

This article focuses specifically on the rock art around two inland lakes, Lakes Vänern and Vättern. They dominate the geography of central Sweden and are so extensive that they can be considered inland seas with a series of small islands (Kvarnäs, Reference Kvarnäs2001) (see Figure 1). Lake Vänern is located towards the west of central Sweden; it is the largest lake in the country and the fourth largest in Europe (Weyhenmeyer et al., Reference Weyhenmeyer, Psenner, Tranvik and Liken2009: 575). Less than 60 km to the south-east of Lake Vänern is the smaller Lake Vättern, which is the second largest lake in Sweden and the sixth largest in Europe (Weyhenmeyer et al., Reference Weyhenmeyer, Psenner, Tranvik and Liken2009: 575). Lakes Vänern and Vättern experienced less dramatic isostatic uplift than the coastal region of Bohuslän, with the north of Lake Vänern experiencing around 3.5 m per thousand years of uplift and the south around 2.6 m per thousand years (Lundqvist, Reference Lundqvist and Freden1998 cited by Drotz et al., Reference Drotz, Wängberg, Jakobsson, Gustavsson and Göran2014). This is evidenced by the palaeo-shoreline maps, which show very little displacement especially around Lake Vättern (SGU, 2018).

Images of vessels are found scattered throughout the landscapes around these bodies of water and the river systems to which they are connected (Figure 1). However, these rock art sites are more modest and less densely distributed than most of their coastal counterparts. Lake Vänern is particularly interesting, as it fills two enormous basins bounded by different types of gneiss (Drotz et al., Reference Drotz, Wängberg, Jakobsson, Gustavsson and Göran2014: 324). The basins are the product of a fault line represented by two peninsulas. Vessels are depicted in small numbers from Värmlandsnäs (Figure 1, no. 24) in the north to Kållandsö (Figure 1, no. 23) in the south, but most of the rock art is around the south-western part of the lake. The main outflow is through the Göta älv (river; Figure 1, no. 1), which runs for 93 km to the Kattegat Sea, and several notable sites have been recorded along its course. Unlike Lake Vänern, Lake Vättern occupies a single basin. Its outflow is through Motala ström (Figure 1, no. 3), which runs eastwards through Lakes Boren, Norrbysjön, Roxen, and Glan (Figure 1, nos. 4–7). Rock art is found in limited quantities along the eastern part of Lake Vättern, where the most significant example is found at Hästholmen (Figure 1, no. 16), but there are smaller sites in the vicinity (see Nilsson, Reference Nilsson2017). Another important group of images is located at Gärstad (Figure 1, no. 17) close to Lake Roxen (Figure 1, no. 6), and there is an even larger concentration of rock art at Norrköping (Figure 1, no. 18) where the Motala ström (Figure 1, no. 3) reaches the Baltic Sea.

Eastern and western rock art

In recent years, south Scandinavian rock art has featured in a number of regional studies (Ling, Reference Ling2013, Reference Ling2014; Skoglund, Reference Skoglund2016; Nilsson, Reference Nilsson2017), making it possible to identify its local characteristics and the ways in which it developed over time. Here, we consider the relationship of ship images in coastal and inland areas, in two extensive regions: a ‘western’ Atlantic sphere centred on Bohuslän (Figure 1, no. 9) and an ‘eastern’ Baltic sphere including Norrköping (Figure 1, no. 18) in Östergotland and the Mälaren valley extending to the east coast. By expanding our geographical view to these broad ‘spheres’, it is possible to compare the representations of ships by the lakes in the interior with their counterparts by the sea.

In eastern Sweden, inland rock art is characterized by ships with in-turned prows (see Figure 3). Images of metal axes are also common inland and resemble those on the coast. It is likely that both groups of axe images were made during the Early Bronze Age (Nordén, Reference Nordén1925: 138; Ling, Reference Ling2013: 83; Skoglund, Reference Skoglund2016: 30–31). There are also certain contrasts within the Baltic sphere: hunting scenes are absent at Simrishamn, yet they appear further north at Norrköping and in the Mälaren valley (Skoglund, Reference Skoglund2016: 99–104). Quite different patterns are found in western Sweden. Images of ships are common at inland sites but they differ from those beside the Baltic and are more like the vessels portrayed in the rock art of Bohuslän during the Late Bronze Age.

Thus, there may have been two separate networks linking the seas and the lakes; they were established at different times, and there is no sign of any overlap between them. Although the Göta Canal, completed in 1830 (Mulder & Kaijser, Reference Mulder and Kaijser2014: 90), connects these spheres today, no such thoroughfare existed in the Bronze Age. Indeed, the high ground between the two large lakes shows little sign of Bronze Age activity (Weiler, Reference Weiler1994: 88–93). Our understanding of the distribution of inland rock art and its relationship to water is primarily based on lakes and present-day rivers in combination with the shore-level data provided by the Geological Survey of Sweden (Sveriges geologiska undersökning; SGU, 2018). Many inland rock art sites seem to be related to present-day watercourses and lakes, but visits to these places reveal more local patterning (Table 1; Figure 1).

Table 1. Rock art sites around Lake Vänern (*sites visited by the authors), their Swedish National Heritage Board (Riksantikvarieämbetet, RAÄ) numbers, the motifs represented, and their relationship to water. ‘Relationship to water’ contains observations of the present-day landscape in comparison to that shown in the shore-level maps of c. 1050 cal bc (3000 kya; SGU, 2018). The references listed are for further information. The data in the table has been sourced from fieldwork, Fornsök (http://www.fmis.raa.se/cocoon/fornsok/search.html), and the database in Nimura, Reference Nimura2015.

With only a few exceptions, the rock art around Lake Vänern has a restricted number of components, and any one panel includes a limited variety of motifs. This is different from the pattern in Bohuslän, where panels on the Bronze Age coast contain more separate elements. Particular images do not appear with any frequency at inland sites around the lakes and fresh motifs were rarely superimposed on older drawings. A similar situation is found further east, but there are important differences. The repertoire is more restricted in the hinterland. At Norrköping, for example, there are hunting scenes and images of swords, but they do not occur along Lake Roxen or Lake Vättern. There is also a significant difference in the number of motifs. Many are found at Norrköping, but fewer at inland sites.

Maritime Places Inland

Another way of comparing inland and coastal rock art is to consider their relationship to water. Perhaps, as Ling suggests (Reference Ling, Stos-Gale, Granding, Billström, Hjärthner-Holdar and Persson2014), representations of ships on the coast marked landing places and sheltered havens, which is where maritime rituals related to travel and trade could have taken place. This is equally plausible at sites around inland water sources, such as Lakes Vänern and Vättern. What follows is a summary of fieldwork carried out on two different occasions. A general survey of sites in the ‘eastern sphere’ took place over multiple visits, and more detailed work was conducted in the ‘western sphere’ (details of the sites around Lake Vänern and further east are presented in Tables 1 and 2).

Table 2. Rock art sites around Lake Vättern and further east mentioned in the text (*sites visited by the authors), their Swedish National Heritage Board (Riksantikvarieämbetet / RAÄ) numbers, the motifs represented, and their relationship to water. ‘Relationship to water’ contains observations of the present-day landscape in comparison to that shown in the shore-level maps of c. 1050 cal bc (3000 kya; SGU, 2018). The references listed are for further information. The data in the table has been sourced from fieldwork, Fornsök (http://www.fmis.raa.se/cocoon/fornsok/search.html), and the database in Nimura, Reference Nimura2015.

Lake Vänern

A good example of an inland maritime place is Otterstad 234 (Figure 1, no. 13). It is almost entirely surrounded by water and less than 100 m from a modern harbour (Kungshamn; not shown on the map) on the tip of Kållandsö (Figure 1, no. 23), the second largest island in the lake (Figures 1 and 2b; Table 1). Here, a panel composed of a few ships and cup marks is on a low-lying outcrop that cannot be seen from the water. There are larger and more prominent rocks nearby, including an outcrop that looks like an inverted boat, but they remained untouched. Comparable features can be identified at other sites, suggesting that the rock art nearest to the lake was connected with harbours: the images were often simple, understated, and placed on inconspicuous outcrops.

Such a situation also occurs at Bolstad (Figure 1, no. 10; Table 1) (Rex Svensson, Reference Rex Svensson1982: 78–81). The site is located at the water's edge, but on the side of a cliff close to where the River Dalbergså (Figure 1, no. 2) enters Lake Vänern. Here there is another modern harbour. Despite its position on a cliff, this is an inconspicuous site. It has two components. The first consists of a few renderings of elk and ships which are visible from the water (Figure 2a). When you stand above them, you look out onto the lake at a point where the other side is invisible. The other component is a single ship, which faces a viewer standing on the cliff edge, and cannot be recognized from below. It is 500 m from a headland that marks the confluence of the river with the lake, based on shoreline reconstruction maps. In the Bronze Age, the distance may have been smaller (Table 1).

Figure 2. a) Bolstad 18:1 (aka Dalbergså) showing three animals and two ships on a cliff face. Inset: the view from atop these images looking out onto Lake Vänern. b) Otterstad 234 contains a few ships and cup marks on a low-lying outcrop (inset). The harbour is shown in the background, as well as the prominent outcrop that looks like an upside-down hull (centre-right) but has no rock art. c) Eskilsäter 7 showing a selection of the seven images of ships on the panel, after heavy rain, emphasizing the deep grooves filled with water.

Other sites are located further away from Lake Vänern. They are more complex than those at the lake's edge, and feature vessels in combination with circular motifs and representations of humans and animals. One example is a small cluster of panels about 3.5 km south of Otterstad 234, namely Otterstad 101 and Otterstad 153 (Figure 1, no. 14; Table 1). These two sites are located about 3 km from the edge of the lake, but under a kilometre from a small bay. Otterstad 101 is another unassuming outcrop, slightly domed like an inverted ship. In this case the imagery is more varied and features cup marks, foot soles, as well as a single vessel. Such sites—slightly more complex in imagery and with a greater number of motifs—are not directly connected to the lake, but can be near other bodies of water.

The same pattern is evident at Husaby 110 (also known as Blomberg) (Figure 1, no. 15; Table 1) (Burenhult, Reference Burenhult1973: 92–93). Here the panel is more complex than those found nearest to the shore, yet it is less than a kilometre from a harbour where boats still moor today. The lake edge does not appear to have changed significantly since 1000 bc. Husaby includes several ships and wheel crosses, and a few motifs resemble those on the west coast of Sweden, including humans with enlarged calves.

Finally, two sites on the Värmlandsnäs peninsula, which extends from the southern point of the lake, are especially intriguing (Figure 1, nos. 11–12 and Figure 2c; Table 1). Again, they may have been near water, but were not directly next to it. Eskilsäter 7 (Figure 1, no. 11) includes at least seven images of ships; two are unusually large and the largest is 2.3 m long. They are situated at the bottom of a gently sloping, wide, flat panel where water pools after it rains. Eskilsäter 39 (Figure 1, no. 12) contains another four ships together with humans, rings, and cup marks (Olsson, Reference Olsson2014: 61–62).

Around Lake Vänern, then, simple rock art can be found close to the water and often near harbours, while slightly more complex sites were located near landing places but set slightly further back from the lake. The latter sites could be near to smaller bodies of water. Other more complex sites exist in the area, but they are located much further from Lake Vänern (mostly over 10 km). They are clustered near smaller bodies of water that may have been connected to Lake Vänern by watercourses during the Bronze Age. These include the various panels around Skepplanda, near to various tributaries of the Göta älv (Figure 1, no. 1), the outflow of Lake Vänern, Husaby 70 (aka Flyhov), and Högsbyn (aka Tisselskog) (see Table 1; not shown on map).

Lake Vättern to the Baltic coast

Rock art in the eastern sphere shares some of these features, but not others. The panel at Hästholmen (Figure 1, no. 16) (Västra Tollstad 21:1; Table 2) in Östergötland was created on elevated ground overlooking the eastern side of the lake, the presence of which is echoed in the large, flat depressions which can fill with rainwater (Figure 3). The panel contains twenty-seven ships probably dating from Period II–III (Nilsson, Reference Nilsson2017) and fourteen axes, as well as other motifs (including nine human figures, six animals, and three feet) (Burenhult, Reference Burenhult1973: 100–01; Broström, Reference Broström2007). The decorated surface includes an unusual concentration of motifs in a region where they are generally uncommon (Goldhahn et al., Reference Goldhahn, Broström and Ihrestam2005). There are few harbours along the eastern margin of the lake, but one is only 300 m from the site. In the medieval period, Hästholmen was a transit point where goods were taken across the water to the city of Hjo (Figure 1, no. 25) (Westerdahl, Reference Westerdahl1998; von Arbin, Reference von Arbin2010). It may have had a similar function in the Bronze Age.

Figure 3. A large boat with its crew at Hästholmen (Västra Tollstad 21:1) with Lake Vättern in the distance, its presence echoed in the pools of water on the rock art panel.

Lake Vättern is connected with the Baltic to the east by the Motala ström and Lake Roxen, where there are panels of figurative images at Gärstad (Rystad 49:1 and Rystad 248:1; Figure 1, no. 17; Table 2) between 500 m and a kilometre from the present shore. The panel closest to Lake Roxen (Rystad 49:1) includes sixteen axes and six ships among other motifs (Broström, Reference Broström2009), while the other panel (Rystad 248:1) contains eight ships among a number of other motifs (Wikell et al., Reference Wikell, Broström and Ihrestam2011). These are the only two sites with figurative images in the area. The Motala ström (Figure 1, no. 3) discharges into the Baltic near the great concentration of rock art at Norrköping (Figure 1, no. 18). About 7000 motifs have been recorded just outside the medieval town, including ships, axes, swords, and human figures (Nordén, Reference Nordén1925; Hauptman Wahlgren, Reference Hauptman Wahlgren2002; Ljunge, Reference Ljunge2015; Nilsson, Reference Nilsson2017).

Again, in the eastern sphere there is an obvious connection between rock art and water. In many cases, it extends to the choice of outcrops for embellishment and the positions of harbours. In the western system, which mainly dates from the Late Bronze Age, there is a contrast between small sites with a few motifs (usually ships) beside the water, and others with a greater variety of images 1–2 km from the lakeshore. This pattern has not been identified in the Early Bronze Age system related to the Baltic, where very ornate panels were close to the water's edge.

Inland and coastal spheres

The representation of bronze artefacts was a feature shared by both western and eastern networks. In these images, axes and swords at a scale of 1:1 were most important in the east (Hauptman Wahlgren, Reference Hauptman Wahlgren2002; Skoglund, Reference Skoglund2018), whereas more people wearing miniature swords can be found in the western zone (Ling, Reference Ling, Stos-Gale, Granding, Billström, Hjärthner-Holdar and Persson2014). Their prototypes were imported from regions further south, and recent research has demonstrated that even local products were made from raw materials that could have been brought to Scandinavia by sea (Ling et al., Reference Ling, Hjärthner-Holdar, Granding, Billström and Persson2013, Reference Ling, Stos-Gale, Granding, Billström, Hjärthner-Holdar and Persson2014; Melheim et al., Reference Melheim, Grandinb, Persson, Billström, Stos-Galed and Ling2018). It is not surprising that exotic artefacts are shown together with ships; this association extends from the Baltic to the Atlantic and to the lakes of southern Sweden. If rock art indicated potential landing places on the coast, would the same apply to inland sites featuring similar designs? If images at the seashore recorded the beginning and ending of journeys, could the same be true of places in the hinterland? If so, how did people and goods travel between these areas?

Fortunately, the possibilities have been discussed in a series of articles by Christer Westerdahl (Reference Westerdahl1992, Reference Westerdahl, Skamby Madsen, Rieck, Crumlin-Pedersen and Olsen1995, Reference Westerdahl and Litwin2000) which draw on the historical geography of southern Scandinavia. He introduces two important concepts (Figure 4a). The first is the transport zone which is characterized by a single means of transport. For example, the open sea would have required large vessels and a sophisticated knowledge of navigation. The river was another transport zone, and light craft used upon it could even be lifted clear of the water and carried overland. Some vessels could possibly have been used in both rivers and on sea journeys that hugged the coast. There was also the use of draught animals or wagons on land.

Figure 4. a) Schematic representation of transit zones and transit points (after Westerdahl, Reference Westerdahl1992, fig. 1); b) map of sailing routes and harbours on Lake Vänern and surroundings (after Westerdahl, Reference Westerdahl1998, fig. 4) superimposed on a shore-level map of c. 1050 cal bc

A second element is the transit point. Goods travelling over long distances could have passed through different transport zones organized around the use of different kinds of vessels. In that case cargoes would have to be reloaded. It could have happened in places with specific characteristics, such as where a river entered the sea. Here, goods were transferred from seagoing vessels to smaller river craft or different kinds of land transport. Another transit point was the portage where ships or goods were taken overland between two bodies of water. This reduced the distance to be covered and avoided obstacles like waterfalls. Westerdahl's work shows that these features played a part during the historical period. Could they have been equally important in the same region during the Bronze Age?

Had a similar scheme been in place in the Bronze Age, different kinds of transport would have to have been available. Scholars have often turned to representations of water transport for this evidence, as watercraft are portrayed in rock art and decorated metalwork, and stone ship settings are a particular feature of the Baltic. However, all these images could have played a specialized role. The designs on Late Bronze Age metalwork show the sun being carried on such a vessel (Kaul, Reference Kaul1998), and the ship settings of the same period are associated with cremation burials (Wehlin, Reference Wehlin2013). Similarly, wheeled vehicles feature in Scandinavian rock art (Johannsen, Reference Johannsen2010), but they are also represented by exceptional artefacts like the Trundholm Sun Chariot (Gelling & Davidson, Reference Gelling and Davidson1969). There is little information on the roles of watercraft in daily life.

We can draw on a little direct evidence: the earliest seaworthy vessel yet discovered in Scandinavia is the plank-built Hjortspring boat dating to the fourth century bc, about a century after archaeologists date the end of the Scandinavian Bronze Age. The ship is 18 m long and is estimated to have held a crew of between eighteen and twenty people. It is generally accepted that boats of this type were suitable for long-distance journeys (Crumlin-Pedersen & Trakadas, Reference Crumlin-Pedersen and Trakadas2003). An important characteristic of the Hjortspring find is its comparatively light construction. It weighs about 500 kg and, if a crew of twenty people lifted the vessel, each would have carried a burden of roughly 25 kilos. Interestingly, it was found 2 km from the sea, which means that it must have been carried to the findspot. If vessels of similar proportions were available during the Bronze Age, could they have made the journey between Lakes Vänern and Vättern and the coast? If not, smaller craft such as dugout canoes or logboats (Kastholm, Reference Kastholm2012, Reference Kastholm2014) may have been used.

It is obvious that both routes—from Lake Vänern to the Kattegat Sea, and from Lake Vättern to the Baltic—would have posed some problems. Lake Vänern is drained by the Göta älv, which would have been navigable with a vessel similar to the Hjortspring boat. There are major waterfalls, such as at Stora Edet (Trollhättan) and Lilla Edet (Figure 1, nos. 21–22), but these obstacles could have been avoided by taking the boat out of the water and carrying it a short distance overland (portaging). Stora Edet means Big Portage and Lilla Edet Little Portage respectively (Westerdahl, Reference Westerdahl1998: 136–37). Scandinavian rock art features a small number of motifs described as ‘ship lifters’ (Ohlmarks, Reference Ohlmarks1963). They are usually interpreted as evidence of rituals or trials of strength, but these images may have referred to groups of people actually lifting ships over small distances on land.

The relationship between Lake Vättern and the Baltic Sea is more complicated, and it is unlikely that plank-built vessels from the Baltic reached Lake Vättern simply by using rivers and lakes. Lake Vättern is connected to the Baltic via the Motala ström, which runs through Lakes Boren, Norrbysjön, Roxen, and Glan (Figure 1, nos. 4–7). It is tempting to imagine a route between Lakes Vättern and Roxen and further to the Baltic but, in contrast to the Göta älv, it has stretches with rapids and waterfalls where boats would have to be carried. Land transport may have played a significant part in this network.

The rock art at Hästholmen (Figure 1, no. 16; Table 2) is different yet again. The site lies 500 m from the present-day shoreline and has a decidedly maritime character: it features many representations of ships and is closely related to the water; after rain, pools of water collect around these images, reflecting the lake in the distance (Figure 3). It is possible that travel on Lake Vättern required plank-built vessels similar to those used at sea. The lake is 135 km long and up to 31 km wide and is known for high waves and rapid changes of wind direction, causing problems even for experienced sailors (von Arbin, Reference von Arbin2010).

There is another way of considering some of these issues. Westerdahl's (Reference Westerdahl, Skamby Madsen, Rieck, Crumlin-Pedersen and Olsen1995) model envisages the use of several different kinds of vessel. The same point has been made in studies of Bronze Age rock art and ship settings (Bradley, Reference Bradley and Goldhahn2009; Bradley et al., Reference Bradley, Skoglund and Wehlin2010; Artursson, Reference Artursson, Bergerbrant and Sabatini2013). Several studies indicate that the ship settings, most of which are on Gotland or the west coast of the Baltic, represented two basic types of vessel: small boats that were best suited to inland waters and larger craft which would be capable of travelling long distances by sea (Bradley, Reference Bradley and Goldhahn2009). If they were portrayed at full size, as is generally supposed, the available space would suggest crews of about fourteen people in one case and more than thirty in the other.

It is impossible to extend this approach to the dimensions of ships in rock art, for there is considerable variation even within a single panel. On the other hand, the sizes of boat crews—typically depicted as single vertical lines above the gunwale—do give some indication of the capacity of individual vessels. In south-eastern Sweden most of these images feature between six and twelve crew strokes (see examples in Figures 2a, 2c, and 3, inset); the most common number is nine (Bradley, Reference Bradley and Goldhahn2009). Here, some vessels were considerably larger, and 24 per cent of the images on the coast feature vessels with more than fifteen crew strokes. That may have been the situation in the Early Bronze Age. Ling's research shows that in the Late Bronze Age at Tanum the equivalent proportion is under 10 per cent (Ling, Reference Ling2014, fig. 10.11).

All these examples, from ship settings to the rock art of the east and west coasts of Sweden, provide evidence for the existence of at least two kinds of vessel during the Bronze Age. The Hjortspring boat with a crew of eighteen to twenty people would have been towards the middle of the range. The point is interesting, as this particular vessel had obviously been manoeuvred overland. Such estimates can never be precise, but they do recall the two elements in Westerdahl's model. They show that more than one kind of vessel was being used during the Bronze Age and that the contrast between ships equipped for long journeys and those better suited to inland waters was reflected in the rock art of this period.

Transport zones and transit points

Westerdahl's scheme emphasizes the importance of separate transport zones (Figure 4). In this case, they may have included the open sea and the rivers leading into the hinterland. The shores of inland lakes were important, too. Are any of these distinctions reflected in the content of the rock art? The distinction between the coastline and inland areas is particularly revealing, but less information is available for the early, eastern network than for Late Bronze Age western connections between the Atlantic and Lake Vänern. That may be because it would have been easier to travel into the hinterland from Bohuslän. Contacts between the Baltic and Lake Vättern were more difficult to maintain and therefore less information is available. With that qualification, there is a striking contrast between the variety of vessels depicted on the coast and those associated with inland lakes. As discussed above, both larger and smaller ships were portrayed on the Baltic shoreline, but, as observed during fieldwork, in almost every case only the smaller variety was associated with an inland site (see Tables 1 and 2). The one exception is revealing, as it is a large boat with a substantial crew near to the water at Hästholmen (Figure 3, inset). It is associated with Lake Vättern where travel could be as dangerous as it was on the open sea (von Arbin, Reference von Arbin2010). There is much clearer evidence from the western network where all the watercraft portrayed in inland areas were comparatively small. By contrast, ships with much larger crews are recorded on the coast of Bohuslän and would have been capable of making longer journeys (Ling, Reference Ling2014, fig. 10.11).

Westerdahl (Reference Westerdahl1992, Reference Westerdahl, Skamby Madsen, Rieck, Crumlin-Pedersen and Olsen1995) also discussed transit points. It is generally accepted that imported commodities were unloaded from seagoing vessels at the shoreline where they could have been transferred to smaller, lighter craft to be taken into the interior. More striking evidence is provided by the siting of rock art in inland areas. It is hardly surprising that it focuses on rivers and lakes when it includes so many images of boats, but it is also clear that, while a few sites were along the major routes into the hinterland, the principal foci were natural harbours. According to Westerdahl's model, these were the obvious places to unload cargoes. Their contents may well have been taken further using vehicles or pack animals. The prehistoric sites shown in Figure 5 are close to the routes around Lake Vänern identified in his study of the historical period.

Figure 5. Rock art sites with ships and a map of sailing routes in Lake Vänern and surroundings (after Westerdahl, Reference Westerdahl1998: fig. 4) superimposed on a shore-level map of c. 1050 cal bc

A Wider Perspective

There is more work to be done at a local scale. This article has been concerned with transport networks and their relationship to prehistoric rock art, but it leaves other subjects for investigation. On one level, we have considered the mechanisms by which non-local items were taken inland, but we have not discussed the contexts in which they changed hands between strangers and local people. Westerdahl's model suggests that more attention should be paid to the transit points in these systems. That will require a more searching analysis of the rock art with which this article began; did all these images refer to connections with the coast, or were some of the design elements more directly related to the motifs associated with inland regions? How much variation existed between sites by the water's edge and those set back from the lakes? Might the relationship between local people and visitors have been expressed through their use of imagery?

Research is also needed at the regional scale. The change of emphasis from an eastern network focused on the Baltic to an Atlantic system with an emphasis on Bohuslän can only be understood in relation to wider developments. It has always been accepted that Scandinavia was at the periphery of ancient Europe as there is no evidence for the extraction of local ores (Ling et al., Reference Ling, Hjärthner-Holdar, Granding, Billström and Persson2013, Reference Ling, Stos-Gale, Granding, Billström, Hjärthner-Holdar and Persson2014; Melheim et al., Reference Melheim, Grandinb, Persson, Billström, Stos-Galed and Ling2018). Despite the material wealth of the Nordic Bronze Age, copper, tin, and gold had to be imported. Metal finds are better represented in Denmark than in the regions studied here, and are comparatively scarce even where tools and weapons are shown in local rock art.

It would be easy to exaggerate the contrast between the Baltic and Atlantic systems. Early Bronze Age images featured in Bohuslän as soon as they appeared in eastern Sweden, but their representation changed over time. The number of decorated panels on the east coast was reduced once more were created in the west, where their number and diversity increased dramatically between 1100 and 700 bc (Ling, Reference Ling2013, Reference Ling2014; Skoglund, Reference Skoglund2016; Nilsson, Reference Nilsson2017). At the same time, the use of this medium became less significant during the Late Bronze Age in Denmark and Scania, where similar designs appeared on decorated metalwork (Kaul, Reference Kaul1998).

Perhaps rock art played a role in two different networks and changed its significance over time. In its earlier manifestation, it depicted artefacts of the kinds represented in specialized contexts in central and western Europe. They include the graves and hoards of the Únětice culture 500 km to the south, and the representations of axeheads on the monument at Stonehenge, 1000 km away in southern England (Skoglund, Reference Skoglund, Skoglund, Ling and Bertilsson2017). Both regions were connected with the Baltic by the use of amber (Vandkilde, Reference Vandkilde2017: 142–51). It may be no accident that amber can be found on the shoreline not far from the cairn at Kivik, which was associated with ‘one of the most extraordinary burials in Bronze Age Europe’ (Kristiansen & Larsson, Reference Kristiansen and Larsson2005: 187). Amber must have been among the commodities exchanged for metal during this period, and it was also used in the complex societies of the Mediterranean (Kaul, Reference Kaul2017; Schallin, Reference Schallin, Bergerbrant and Wessman2017). Most authorities agree that Denmark and parts of Sweden were linked to long-distance networks that extended into central and southern Europe (Vandkilde, Reference Vandkilde2014), and are illustrated by the distributions of diagnostic artefacts. Similarly, metal analysis suggests that artefacts and raw materials were introduced to Scandinavia from the Alps and more distant areas (Ling et al., Reference Ling, Stos-Gale, Granding, Billström, Hjärthner-Holdar and Persson2014).

By the later second millennium bc, long-distance networks were changing, and there is evidence for the introduction of metals from the Iberian Peninsula. At the same time, established links with the Mediterranean seem to have been disrupted by social and political changes there. In Sweden, the distribution of rock art gradually shifted to the west coast and to regions with excellent harbours but less productive land. Even the areas that had supported large-scale food production during the Early Bronze Age seem to have suffered a setback. By 1100 bc, domestic buildings were smaller than their predecessors, mortuary rituals consumed less energy, and metal may not have been so readily available (Kristiansen, Reference Kristiansen, Beck, Eriksen and Kristiansen2018).

Depictions of boats dominate the rock art of Bohuslän and other locations along the shoreline (Coles, Reference Coles2005; Ling, Reference Ling2014). Some of the Late Bronze Age panels show scenes of conflict, and this has led Ling and colleagues (Reference Ling, Earle and Kristiansen2018) to suggest the development of maritime chiefdoms that engaged in long-distance expeditions like those of the Viking Age. The sources of metalwork certainly became more diverse between 1100 and 700 bc, when they ranged from the Alps and northern Germany to as far afield as Britain and Iberia (Ling et al., Reference Ling, Stos-Gale, Granding, Billström, Hjärthner-Holdar and Persson2014). It appears that contacts with communities in western Europe intensified (Ling and Uhnér, Reference Ling and Uhnér2014). The images in the rock art of Bohuslän include types of sword which are found in western Europe but do not occur locally (Skoglund, Reference Skoglund2016: 35–37). Although discussions of this phenomenon seldom extend to Scandinavia, the occupants of the west coast and their exchange partners in the interior might have been located at the furthest limits of this network.

In this paper, we have used the evidence of Bronze Age rock art to investigate the contacts between communities on the coast and those around large inland lakes. That may seem a local concern, but if those networks changed over the course of time, they did so in response to developments that extended over a much larger area. The challenge will be to find the right balance between these elements.

Acknowledgements

The fieldwork at Lake Vänern was supported by the Lennart J. Hägglunds stiftelse för arkeologisk forskning och utbildning. We are grateful to Tommy Andersson (Högsbyn) and Hans Olsson (Värmlands Museum) for their hospitality and local knowledge at Högsbyn and Värmlandsnäs respectively.