Introduction

People project their ‘social self’ (Shaw, Reference Shaw2005; Jervis, Reference Jervis2017) through material culture, especially through clothes and jewellery. According to Eicher (Reference Eicher and Eicher1995: 1), ‘Dress is a coded sensory system of non-verbal communication that aids human interaction in space and time. The codes of dress include visual as well as other sensory modifications (taste, smell, sound, and feel) and supplements (garments, jewellery, and accessories) to the body which set off either or both cognitive and affective processes that result in recognition or lack of recognition by the viewer’. Textiles are, however, rarely preserved in archaeological contexts; usually, what remains are the dress accessories—brooches, dress fasteners, buttons, belts, etc.—the only material evidence of attire. What people wear reflects their status, material situation, and identity, but to understand these relationships, we first need to understand the value, both monetary and social, of those items. Here, we aim to analyse the accessibility to dress, more specifically dress accessories, as one of the factors reflecting the living standard in late medieval (thirteenth to fifteenth century ad) rural communities in central Europe.

Most dress accessories, belt buckles, mounts, or brooches (etc.), seem to be mass-produced items. They are quite common archaeological finds, but are not recovered in large quantities in excavations of medieval sites, whereas they are well-known from metal-detector surveys. They are also present in medieval iconography, but few written sources enlighten us about them. These sources usually refer only to the most valuable specimens, which are absent in archaeological assemblages, except for rare finds of treasure hoards. Moreover, research on dress accessories from rural areas is very rarely noted by archaeologists and historians (for a British perspective, see Smith, Reference Smith2009; Jervis, Reference Jervis2017), mostly because the evidence is scarce. Most of the data available in central Europe come from large urban centres.

There has been little research undertaken on this topic thus far, although the data from rural archaeological sites is more than sufficient for a preliminary study. The finds that were used for this research were recovered from five village sites; our evidence was largely obtained through archival research and no data from metal detecting were available. This evidence is complemented by finds from two cemeteries in modern western Slovakia, Ducové (Ruttkay, Reference Ruttkay, Hanáková, Sekáčová and Stloukal1984, Reference Ruttkay1989) and Krásne (Gogová, Reference Gogová2013).

We argue that in central Europe the dress accessories used by the majority of the inhabitants of towns and villages hardly differ. This leads us to conclude that most of the production was undertaken by craftsmen living in towns, and then distributed further afield. We suggest that the even distribution and access to dress accessories among urban and rural populations shows an adaptation to an urban lifestyle. Nevertheless, an internal stratification within rural communities can be detected. We discuss, following Smith's hypothesis (Reference Smith2009), that the use of similar dress accessories among the inhabitants of towns and villages was not a manifestation of resistance against lords, but rather normal, affordable fashion. Such a conclusion also appears to have been reached by Eljas Oksanen and Michael Lewis (Reference Oksanen and Lewis2020) whose analysis of finds from the British Portable Antiquities Scheme (PAS) shows that the rural population in England and Wales had access to good quality metalwork.

The Data

Medieval dress accessories, as well as other small finds, tend to be a marginalized group of artefacts in the archaeological literature, except in Britain, which has an enviable record of research on dress accessories (e.g. Egan & Pritchard, Reference Egan and Pritchard2002; Hinton, Reference Hinton2005; Cassels, Reference Cassels2013; Standley, Reference Standley2013). Elsewhere, the situation is slowly changing, and recent interest in material culture, especially in ‘assemblage theory’ and ‘Actor-Network Theory’, provides interesting tools and perspectives for further studies (Hicks, Reference Hicks, Hicks and Beaudry2010; Hamilakis & Jones, Reference Hamilakis and Jones2017; Harris, Reference Harris2017; Jervis, Reference Jervis2017). Yet, the archaeological data are unevenly distributed, since, in regions where metal detecting is illegal, most finds come from urban sites usually excavated by commercial companies. In central Europe, the largest corpus of stratified finds comes from a single site in Wroclaw, Nowy Targ Square (New Market Square; Sawicki, Reference Sawicki2017). Some finds were published from Brno (Zůbek, Reference Zůbek2002), but generally most published dress accessories are scattered among site reports and shorter contributions (see Vyšohlíd, Reference Vyšohlíd, Wachowski, Piekalski and Krabath2011). A more general perspective on small finds, including dress accessories, is given in the works of Krabath (Reference Krabath2001) and Wachowski (Reference Wachowski and Bagniewski2002, Reference Wachowski, Doležel and Wihoda2012). As for the question of value, dress accessories from treasure hoards provide information about the finds made of precious materials like silver and gold, which are exceptionally rare in urban or rural assemblages. The studies of the treasure hoards from Pritzwalk (Krabath et al., Reference Krabath, Lambacher and Kluge2006), Fuchsenhof (Prokisch & Kühtreiber, Reference Prokisch and Kühtreiber2004), and Szczecin (Frankowska-Makała, Reference Frankowska-Makała, Glińska, Kroman, Makała and Krzymuska-Fafius2004) are among the most interesting works on the subject in central Europe.

The state of research on deserted and destroyed medieval villages is regionally uneven. Research on such topics hardly features within the present-day borders of Poland (Fokt & Legut-Pintal, Reference Fokt, Legut-Pintal, Nocuń, Przybyła-Dumin and Fokt2016), while it is well advanced in the Czech Republic and Slovakia. However, these studies mostly focus on the organization of settlements, which corresponds well with more strictly historical questions but less so with the social and daily life of the inhabitants of these settlements. Some works refer to the general use of metal (Belcredi, Reference Belcredi1988, Reference Belcredi1989) or crafts from the Czech Republic (Belcredi, Reference Belcredi1983) and Austria (Theune, Reference Theune2009), others focus on selected types of objects, such as horse equipment (Měchurová, Reference Měchurová1985) or small bronze finds (Měchurová, Reference Měchurová1989). In addition, some recent unpublished undergraduate and Master's dissertations have dealt with aspects of the material culture and finds from selected sites in the Czech Republic (Hauser, Reference Hauser2015; Hylmarová, Reference Hylmarová2016).

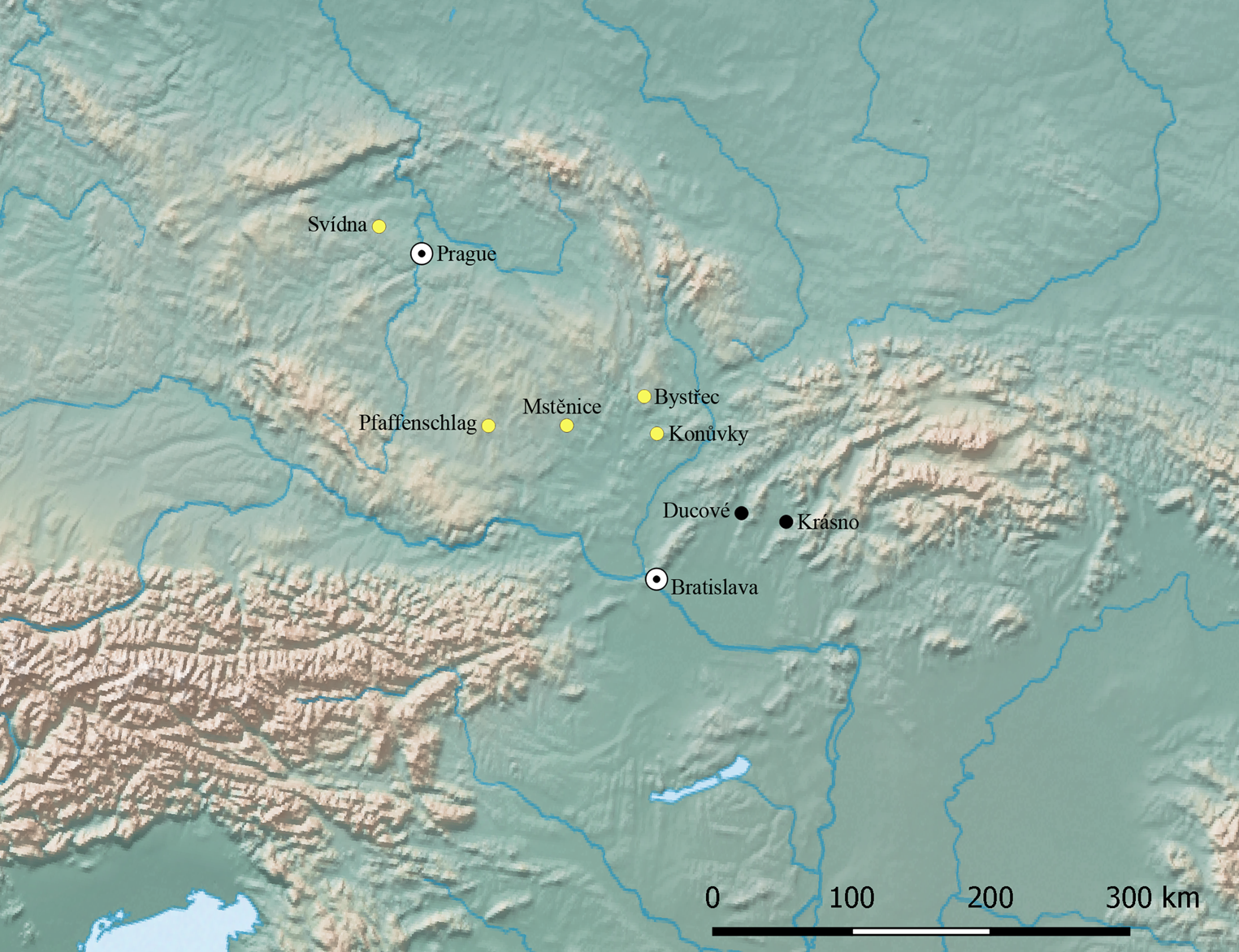

For this study, we have chosen five medieval villages (Figure 1), all founded in the thirteenth century and deserted in the fifteenth century. They were mostly excavated in the 1960s to 1980s. There are no data from metal-detector surveys available, which might have made a more important contribution. A summary of all the selected sites can be found in Supplementary Material, Table S1 and the finds, which form the core of this research, are listed in Supplementary Material, Table S2. We are aware that the villages are located in different areas, and their proximity to larger cities or fairs varies (see Kypta, Reference Kypta2014: 421). Furthermore, the finds from deserted villages differ from those from destroyed villages, as most tools and other objects were usually removed by the inhabitants of the latter villages.

Figure 1. Location map of villages and cemeteries mentioned in the text.

Dress accessories from two cemeteries in present-day western Slovakia were also studied (Figure 1, Supplementary Material, Table S1). It is worth stressing that graves with dress accessories from the late medieval period are exceptionally rare in central Europe, especially from burials dated to the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, and hence they are particularly important for our discussion.

Assessing the Economic Value of Dress Accessories

In the literature consulted, attitudes towards the value of dress accessories seem to vary. In England (Egan & Pritchard, Reference Egan and Pritchard2002; Smith, Reference Smith2009; Jervis, Reference Jervis2017) and the Netherlands (Willemsen, Reference Willemsen and Clevis2009, Reference Willemsen2012), items of non-precious metals are generally considered to be cheap and mass-produced, whereas in central Europe, and especially in the older literature, even bronze dress accessories are considered to be more significant (Krabath, Reference Krabath2001; Wachowski, Reference Wachowski and Bagniewski2002; Janowski & Wywrot-Wyszkowska, Reference Janowski and Wywrot-Wyszkowska2017). This divergence seems to be mostly due to the state of research and the sheer number of finds: in England and Wales, documentation on such finds is now is accessible through the PAS portal (finds.org.uk), whereas the central European data consist mainly of urban finds recovered during rescue excavations. Recent research on finds from medieval Wroclaw (Sawicki, Reference Sawicki2017) and Gdańsk (Bednarz, Reference Bednarz and Krzywdziński2016; Leśniewska, Reference Leśniewska and Krzywdziński2016) suggests that the majority of such urban finds were quite common items. Nevertheless, we still do not have a general tool to estimate the value of medieval dress accessories. In essence, there are seven different types of sources providing information about medieval garments and dress accessories, all contributing to a broader picture:

– Written sources, including testaments, sumptuary laws and other sources

– Iconography

– Urban contexts

– Rural contexts

– Castles / fortified settlements / seignorial towers, etc.

– Burials

– Hoards

In the recent archaeological literature that uses dress accessories as part of a broader debate (Jervis, Reference Jervis2017; Haase & Whatley, Reference Haase and Whatley2020), the classification tends to be simplified and mostly confined to decorated and undecorated examples. Taking the sources of dress accessories listed above into account, we propose a method based on three different factors: the raw materials, decoration and technology (Table 1), and type, when comparing whole assemblage.

Table 1. Value and quality markers to enhance dress accessories.

Raw materials

In the testaments of burghers, different dress elements are quite often mentioned with a given price. The objects are not usually described, the price and the material they are made of being the only information available (Schultz, Reference Schultz1871; Wysmułek, Reference Wysmułek2015). Such sources indicate that the only dress accessories that were worth mentioning and passing down the generations were those made of precious materials like gold and silver, with decoration and technology being a secondary or even unimportant aspect. Similarly, hoards mostly contain finds of precious material, indicating that the cost of the raw materials was the most important factor when determining the value of hoarded items. The presence of precious stones is clearly an important factor, adding to the monetary value of the items into which they are set. Niello and enamel techniques, described in detail by Theophilius Presbyter, a monk writing on the various arts in the twelfth century (see Hendrie, Reference Hendrie1847), are even more complicated in this respect. Nevertheless, even here, the material used (gold or silver gilt) still seems to be more important than the ornamentation.

In evaluating archaeological finds—such as those from Wroclaw, which yielded numerous brooches decorated with enamel, but also bronze examples (Figure 2a–d)—the question is not so much about the difference between precious materials and more mundane ones, but about the gradation among the most common finds, i.e. those made of bronze, tin, and iron.

Figure 2. Dress accessories, New Market Square, Wroclaw. a–d) brooches (inv. nos. 433, 439, 418, and 434); e) iron buckle (inv. no. 166); f) leather belt with mounts (inv. no. 1). After Sawicki, Reference Sawicki2017.

Decoration

Tin-lead alloys are considered cheaper materials than bronze (Egan & Pritchard, Reference Egan and Pritchard2002). However, casting tin is thought to be easier, as it involves a lower temperature, although the final products might be flawed by air bubbles if the moulds were not prepared correctly (Egan, Reference Egan, Kicken, Koldeweij and ter Molen2000: 102). Egan even suggests that the ornaments on these items were intended to hide any flaws from their production (Egan, Reference Egan, Kicken, Koldeweij and ter Molen2000: 102). Tin-lead alloy artefacts are usually cast in more elaborate forms than bronze items, the latter usually decorated after casting (Egan & Pritchard, Reference Egan and Pritchard2002; Sawicki, Reference Sawicki2017). When discussing decoration techniques, the difference between undecorated objects and carved or engraved exemplars is small in terms of the amount of work and tools required to finish them. It is thus debatable whether such general categories as decorated or undecorated are all that pertinent when evaluating the possible value of a dress accessory (Jervis, Reference Jervis2017).

Iron buckles are quite often intentionally not taken into account in works about dress accessories (Fingerlin, Reference Fingerlin1971; Krabath, Reference Krabath2001). Their study can be problematic, as they are not easily identified as accessories worn by people. Some are frequently attributed to horse equipment (Egan & Pritchard, Reference Egan and Pritchard2002; Goßler, Reference Goßler2011) and hence not as part of a person's daily dress or as an item of higher value. However, iron (and steel) buckles are mentioned in the regulations of the Girdlers’ Guild from fourteenth-century London (Egan & Pritchard, Reference Egan and Pritchard2002). Most iron buckles appear to be very simple, undecorated specimens, which constitute the largest component of the assemblage of dress accessories (Sawicki, Reference Sawicki2017: 20). There is, nonetheless, a substantial number of well-made iron buckles, carefully forged and carved with decorations (Figure 2e). Some have traces of a tin coating that originally made them resemble silver exemplars. Their existence is known from written sources, in laws from Legnica (Silesia, modern Poland), which forbade the use of tin buckles (Wachowski, Reference Wachowski and Bagniewski2002: 260).

Type of dress accessories

When considering value, the type of dress accessory is an important factor. Generally speaking, the data are insufficient to establish whether certain types of buckles or strap ends were more valuable than others, a possible exception being the strap ends thought to be part of the belts worn by knights (Wachowski, Reference Wachowski and Bagniewski2002). In more general terms, strictly non-utilitarian dress accessories (following Haase & Whatley, Reference Haase and Whatley2020) were rarer, possibly more expensive, not essential, or even a luxury; they include jewellery (rings) and brooches, which in late medieval times were too small to fasten an outfit and were generally used for decoration. For instance, at the cemetery of Ducové, only six graves out of 220–230 burials contained rings (accompanying females and infants or juveniles), and brooches were found in only seven graves (in three graves they were the only artefact found); by contrast, parts of a belt (at least one buckle) were found in sixty-one graves (Ruttkay, Reference Ruttkay1989). There were only two rings, one of which was made of gold, and no brooches among the finds from the villages selected for our study; there, the majority of most dress accessories consisted of buckles.

This is not surprising, since buckles seem to be an essential element of dress (Smith, Reference Smith2009: 323). The high frequency of buckles compared to other dress accessories is visible in the assemblage from New Market Square in Wroclaw (Sawicki, Reference Sawicki2017: 11), where buckles make up thirty-two per cent of the assemblage and there are almost three times as many buckles as strap ends (178 buckles, 61 strap ends: Sawicki, Reference Sawicki2017: 11). Unlike buckles, strap ends seem to be much more expensive. In late medieval iconography, peasants are shown wearing simple belts with buckles only (Smith, Reference Smith2009: 325, fig. 5 A & B). It may, however, be a false interpretation, since finds from rural cemeteries include fully decorated belts with strap ends as well as mounts. This seems to be an important factor because belts were made of different elements, i.e. buckles, mounts, strap ends, etc., which are usually listed separately among archaeological finds. We can assume that the number of mounts was most probably related to the value of a belt. The numerous cheap decorations on belts were probably quite impressive at first sight, but a closer examination reveals that some were simply made. Many mounts, even though they are frequent, were merely cut and stamped sheets of metal, as attested at Wroclaw (Figure 2f). They were probably more expensive than the undecorated pieces, yet presumably still much cheaper than similar items made of more precious materials such as silver, or silvered or gilded bronze.

To summarize, we have proposed a tripartite scheme consisting of the quality of the raw material, the decoration, and the type of artefact to evaluate dress accessories. The presence of non-utilitarian objects, such as strap ends, brooches, and jewellery (rings) might indicate a wealthier assemblage. The ornament itself seems to be less important, especially when it is only an engraving or a stamped motif. There are nonetheless many factors involved when estimating the value of dress accessories, bearing in mind the uniqueness of each piece and the relational character of medieval trade.

Dress Accessories in Medieval Villages

Here, we attempt to characterize the dress items recovered in selected deserted and destroyed villages. It is worth noting that the question of artefacts recovered in rural areas (not only dress accessories) formed part of discussions among British scholars. In the early days of the PAS, Geoff Egan compared finds from urban and rural areas and concluded, somewhat surprisingly, that there was little difference between these assemblages (Egan, Reference Egan, Giles and Dyer2007). Since then, some more publications have focused on this or similar aspects (Smith, Reference Smith2009; Hinton, Reference Hinton, Dyer and Jones2010; Wheeler, Reference Wheeler, Jervis and Kyle2012; Cassels, Reference Cassels2013; Lewis, Reference Lewis, Jervis, Broderick and Grau Sologestoa2016; Jervis, Reference Jervis2017). It is worth noting that since the early 2000s, the dataset from the PAS has greatly increased and provided more information about the material culture in rural areas (Lewis, Reference Lewis, Jervis, Broderick and Grau Sologestoa2016). A valuable, broader summary about the material culture from Czech medieval villages was also produced by Jan Kypta (Reference Kypta2014).

Villages

It is important to note that we distinguish between villages with a stronghold nearby and those without. Bystřec, Pfaffenshlag, and Svídna are in the latter group (Supplementary Material, Table S2). Bystřec is a deserted village situated in southern Moravia, near the medieval town of Vyškov (c. 15 km distant). The village, which consisted of twenty-two homesteads, was founded in the first half of the thirteenth century and was burnt down around ad 1401 (Belcredi, Reference Belcredi2006: 24–25). Pfaffenschlag is a deserted medieval village near Slavonice in southern Bohemia, which was completely and systematically excavated between 1960 and 1971. It was founded in the thirteenth century and was probably burnt down in 1423 during the Hussite wars. The medieval village spreads over 22,500 m2 and contained sixteen homesteads, their gardens, fields, and a mill. A typical homestead consisted of a tripartite residential house and a cowshed (Nekuda, Reference Nekuda1975: 159). The nearest marketplace was probably in Slavonice (c. 4 km distant). Svídna is situated near the town of Slaný, some ten kilometres away, in central Bohemia and was investigated between 1966 and 1973, first by non-destructive methods (by surface prospection, a geophysical survey, and phosphate analysis) and then three homesteads were excavated. This village was founded in the thirteenth century and abandoned in the first half of the sixteenth century because of a lack of water. It is important to note that Svídna is the only site that was not fully excavated, and it is also the only village which was abandoned and not destroyed during the Hussite wars.

Konůvky and Mstěnice (Supplementary Material, Table S2) belong to the group associated with a small regional stronghold or a manor. Konůvky is a deserted medieval village in the Ždánický forest in southern Moravia, some five kilometres from the town of Ždánice. Ten homesteads with the remains of thirty-three buildings, a motte, and a gothic church with a cemetery were recorded there. The village was founded in the thirteenth century and ceased to exist around the beginning of the fifteenth century, according to the archaeological evidence, or in ad 1481, according to the written sources (Měchurová, Reference Měchurová1997: 8–44). Mstěnice was founded in the second half of the thirteenth century and burnt down in 1468, although the village was probably deserted before this event. It contained seventeen homesteads with three-part houses, a manor (the homestead of the lord), and a stronghold (Nekuda, Reference Nekuda1985: 171–83; Nekuda & Nekuda, Reference Nekuda and Nekuda1997: 53–75). A mill and a motte were close to the village (Nekuda, Reference Nekuda2005: 321). Mstěnice lies between three towns: Moravské Budějovice, Moravský Krumlov, and Třebíč (each some eighteen kilometres distant). All the villages were a maximum of one-day's travel on foot from a larger town with a fair, and three were half a day's travel away. There seems to be no direct correlation between the distance to a fair and access to dress accessories. Most finds come from Konůvky, only five kilometres from a local centre, but the second-most assemblage of finds came from Mstěnice, which required travelling for a day to the nearest town. However, distance does not seem to be important in terms of the quantity of finds of dress accessories (which are only a potential proof of accessibility); rather, it was the infrastructure in the village itself, such as the presence of a stronghold and the lord's residence, that seems to have been significant.

The finds of dress accessories from the villages consist of 130 specimens (Supplementary Material, Tables S1 and S2). Their quantitative analysis is only partially useful, with the ratio between dress accessories and other metal finds more or less flat (Supplementary Material, Table S1). It varies between six per cent (Bystřec) and thirteen per cent (Svídna), although the latter was the only site which was not fully excavated. When we look at the raw numbers of finds, we can nevertheless see that there are more dress accessories at the sites with stronghold (thirty-five finds at Mstěnice and fifty-seven at Konůvky) than in the other villages (twenty-six at Bystřec, nine at Pfaffenschlag, and three at Svídna) (Supplementary Material, Tables S1 and S2). At Svídna, the dearth of dress accessories is also likely to be related to the fact that people abandoned it systematically, probably taking their belongings away when they left.

The situation is unclear when we compare the finds from specific structures in the villages. Most dress accessories were found in the stronghold: twenty in Konůvky and sixteen in Mstěnice. At the latter site, another twelve came from the manor. As for the ordinary houses in the villages, the average number of finds varies from site to site (Supplementary Material, Tables S1 and S2), but generally the average number of dress accessories is around one per house. The situation is different in Svídna (not fully excavated), where there are three buckles from one house for example, and in Mstěnice, where most dress accessories were found in the manor and the stronghold, where the average is around 0.5 per house.

The qualitative analysis of the selected finds provides information on differences between raw materials. Artefacts made of iron and bronze are the only items from the villages (except for a single gold ring) and artefacts made of lead-tin alloys, which are quite common in towns (Egan & Pritchard, Reference Egan and Pritchard2002; Egan, Reference Egan, Giles and Dyer2007; Sawicki, Reference Sawicki2017: 2), are absent. It is possible that this reflects the way the tin-lead alloys are preserved in the ground. Such a situation is also visible in the data from the British PAS. For the period between ad 1200 and 1500 in the database (for December 2018), 2012 objects are made of lead alloys and thirty-two are made of tin or tin alloys; the number of objects made of bronze is far larger, with 54,760 artefacts. In the assemblage of dress accessories from the New Market Square site in Wroclaw (Sawicki, Reference Sawicki2017), seventy-eight out of 515 artefacts were made of lead-tin alloys, i.e. slightly more than fifteen per cent of all the finds. It is difficult to establish whether this indicates lower accessibility to wares made of lead-tin alloys or whether lead-tin artefacts were more often melted down in rural environments.

From all the villages analysed here, ninety-eight of the dress accessories were buckles. Eight are made of bronze alloys, sixty of iron, and the remaining thirty are unidentified (see Supplementary Material, Table S2). However, we expect that most of these finds are made of iron. The other remaining dress accessories are made of bronze, except for one simple gold ring.

We believe that iron was the cheapest and most easily accessible material. Simple iron buckles could have been made by a local smith and distributed among the villagers and their closest network. Such simple items (although quite elaborate iron examples are known, too; Sawicki, Reference Sawicki2017; see also Figure 2e) were not as visually attractive as bronze buckles, although they fulfilled their basic function. We should also recall that iron buckles were used as harness buckles and for agricultural equipment (Goßler, Reference Goßler2011); no doubt some of the exemplars in a given assemblage were used for such purposes. Especially massive buckles, with so-called solid front rollers or with central bars with integrated pins (Sawicki, Reference Sawicki2017: 127, cat. nos. 144, 146), are thought to have fulfilled such functions. Some such buckles are known from medieval burials (Ruttkay, Reference Ruttkay1989: 368), even early modern ones (Sawicki, Reference Sawicki2015: 88), which makes it rather unlikely that large buckles of this kind only belonged to harness fastenings. The form of other iron buckles (excepting spur buckles), especially the most common exemplars with oval or rectangular frames, is too unspecific to link them to a particular purpose. Iron buckles vary significantly in quality; some are very carefully made (Sawicki, Reference Sawicki2017: 124; see Figure 2e), while the bars of others were not assembled by a smith (Sawicki, Reference Sawicki2017: 111, cat. no. 88). The state of preservation of many iron finds makes them more difficult to analyse. Bronze buckles, on the other hand, were mostly cast, which requires moulds and at least a basic workshop. These items were probably made in an urban context by specialized craftsmen, who then distributed their products inland, for example through fairs or travelling traders.

In Konůvky and Bystřec there is little difference between the buckles from the village houses and those from the stronghold and the manor. The bronze examples vary in shape and form, but they are generally simple, utilitarian buckles, probably used to fasten shoes or simple belts. At Konůvky, more elaborate bronze buckles (clearly used for belts) were found in the village but not in the stronghold (Figure 3 a–b), while only one similar bronze buckle was recovered from the Mstěnice manor (Figure 3c). Among the villages without a stronghold, only Pfaffenshlag yielded bronze buckles, all regular belt buckles (Figure 3d). They include rectangular buckles of similar width, as well as composite buckles with a movable front (Figure 3e), which are known from many late medieval sites, including Prague and Wroclaw (Figure 3f–g).

Figure 3. Belt buckles. a–b) Konůvky (inv. nos. 75564 and 75565); c) Mstěnice (inv. no. 15636); d–e) Pfaffenschlag (inv. nos. 36670 and 42656); f–g) New Market Square, Wroclaw (inv. nos. 42 and 65). After Měchurová, Reference Měchurová1989 (Konůvky); Nekuda, Reference Nekuda1975 and Reference Nekuda1985 (Mstěnice); Sawicki, Reference Sawicki2017 (Wroclaw). By Permission of M. Měchurová (specimens from Konůvky), others redrawn and edited by Jakub Sawicki.

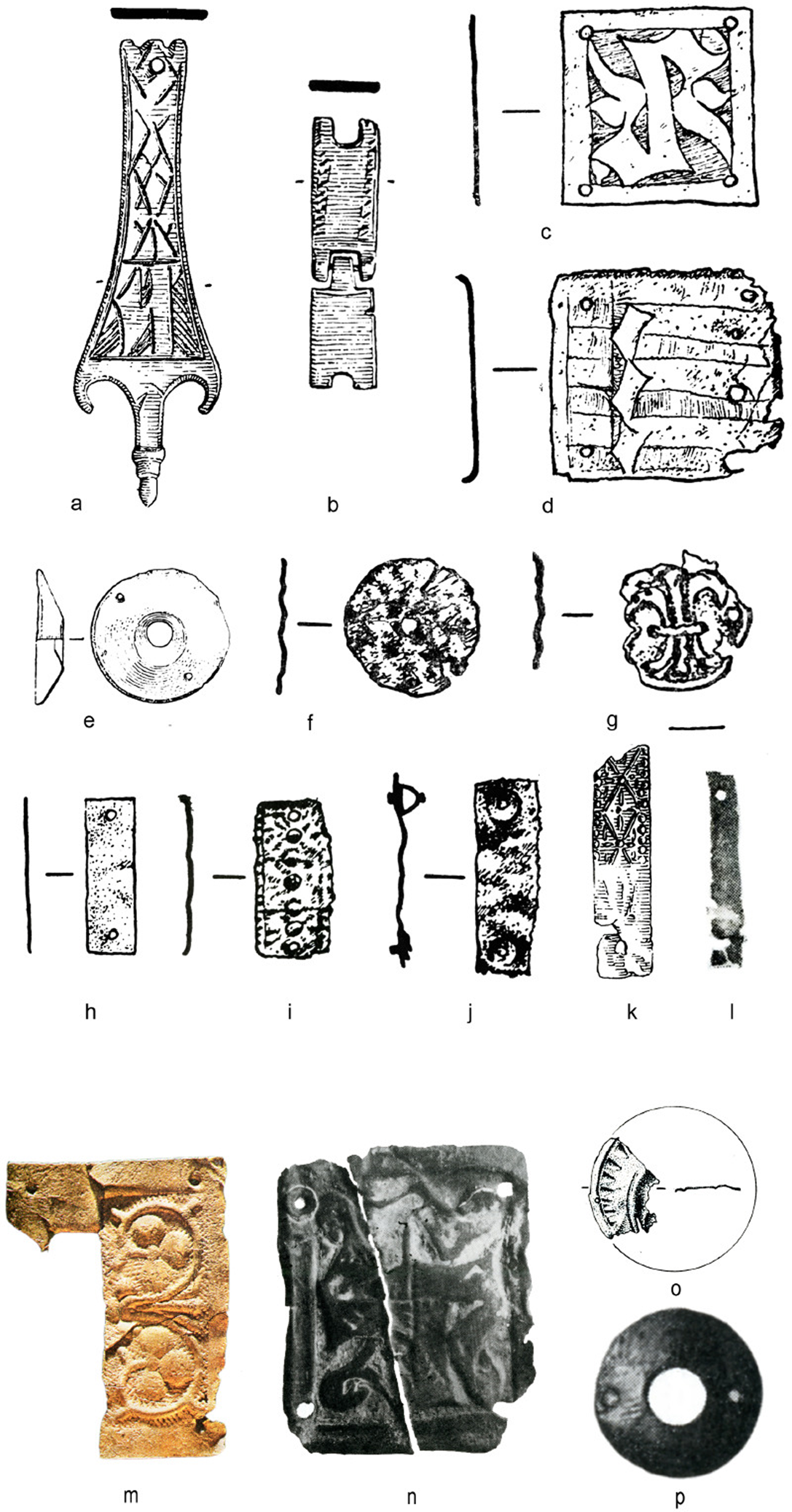

Few other types of dress accessories were found in the villages, and all were made of bronze alloys. They are mostly simple belt mounts (Figure 4). In Konůvky, a decorated strap end was found among them (Figure 4a), in an ordinary house (house no. 4), not in the stronghold. This house also yielded a decorative rectangular belt mount with a geometric motif and a possible book clasp (Figure 4b, 4d), possibly indicating that its occupant had a special position in the community. As for Mstěnice, the belt mounts (Figure 4a–d) were recovered in the stronghold but one of the more decorative examples was found outside it.

Figure 4. Dress accessories. Konůvky: a) strap end (inv. no. 72352); b) hinged belt plate (inv. no. 72353); c–l) belt mounts (inv. nos. 72357, 72354, 72366, 72367, 75802, 72368, 72369, 72370, 72388, and 72389). Mstěnice, belt mounts: m–p (no inv. and inv. nos. 97030, 35349, 35071).

After Měchurová, Reference Měchurová1989 and Reference Měchurová1997 (Konůvky); Nekuda, Reference Nekuda1985 and Nekuda & Nekuda, Reference Nekuda and Nekuda1997 (Mstěnice). By Permission of M. Měchurová (specimens from Konůvky), others redrawn and edited by Jakub Sawicki.

In sum, the dress accessories from the villages are mostly iron buckles, which could have been used not only for human attire but also in farming, for instance as parts of animal harnesses. Other dress accessories, including bronze buckles, only occur in assemblages from the villages with a stronghold (Figure 4). From this we deduce that the latter were richer and better connected with urban networks, not necessarily by distance, but probably by wealth or social connections. However, the (relatively) more ornate dress accessories were not all found within the villages’ stronghold; some came from other houses in those villages. We must, however, bear in mind that these are finds from villages that were destroyed, i.e. its occupants removed most of their possessions as they left. This could explain the lack of brooches or a larger number of rings, as such items may have had a greater value.

Cemeteries

To complement this study, we examined the dress accessories found in burials in the cemeteries of Ducové and Krásno (Supplementary Material, Table S1). A cemetery context is obviously different from a town or village setting, where dress accessories are usually random finds representing most probably lost or discarded items.

Ducové is one of the largest medieval cemeteries in Slovakia, consisting of 1881 graves dating from the ninth to the fifteenth century (mostly tenth–fifteenth century). Some 220 to 230 graves belong to the fourteenth–fifteenth century, suggesting a population of 47–50 people thought to represent one or two villages (Ruttkay, Reference Ruttkay1989: 356). The cemetery in Krásno consisted of 1609 graves dated from the eleventh to the fifteenth century and was used by three villages, Krásno, Nedanovce, and Turčianky (Gogová, Reference Gogová2013).

Ruttkay (Reference Ruttkay1989) suggests that the people buried in Ducové were ordinary local people who were not part of the local elite. The finds from the fourteenth–fifteenth-century graves might, at first glance, indicate the opposite: many graves contained full belt sets, including buckles, various mounts, and strap ends—finds which are very rare in an urban context (Egan & Pritchard, Reference Egan and Pritchard2002; Janowski & Wywrot-Wyszkowska, Reference Janowski and Wywrot-Wyszkowska2017; Sawicki, Reference Sawicki2017). All were made of common materials, bronze and iron, suggesting that the deceased belong to modest classes. Willemsen (Reference Willemsen and Clevis2009, Reference Willemsen2012), as well as Egan and Pritchard (Reference Egan and Pritchard2002), point to the general cheapness and mass production of these types of objects in Europe. In the case of such finds in graves in central Europe, the situation is probably similar. On the other hand, they could have belonged to outfits not normally worn by the inhabitants of rural areas, but as festive dress worn for special occasions.

The existence of specialized craftsmen (e.g. bucklesmith guilds) in many European towns suggests an urban provenance for these dress accessories, although some local production in villages, small towns, or fairs cannot be excluded. Some items could have been made by travelling craftsmen or even non-specialized traders. The production of cast accessories requires skill and experience, crucibles, moulds, and fire, although there is a visible increase from the fourteenth century onwards in dress accessories made from wire and sheet metal (Sawicki, Reference Sawicki2017: 93, cat. no. 30). The ease with which buckles and mounts can be mass-produced suggests a town-centred production and then distribution further afield. The high accessibility to dress accessories in Britain is also noted by Cassels (Reference Cassels2013: 148–49), who showed that, bar a few local trends, there are no major regional variations between cities.

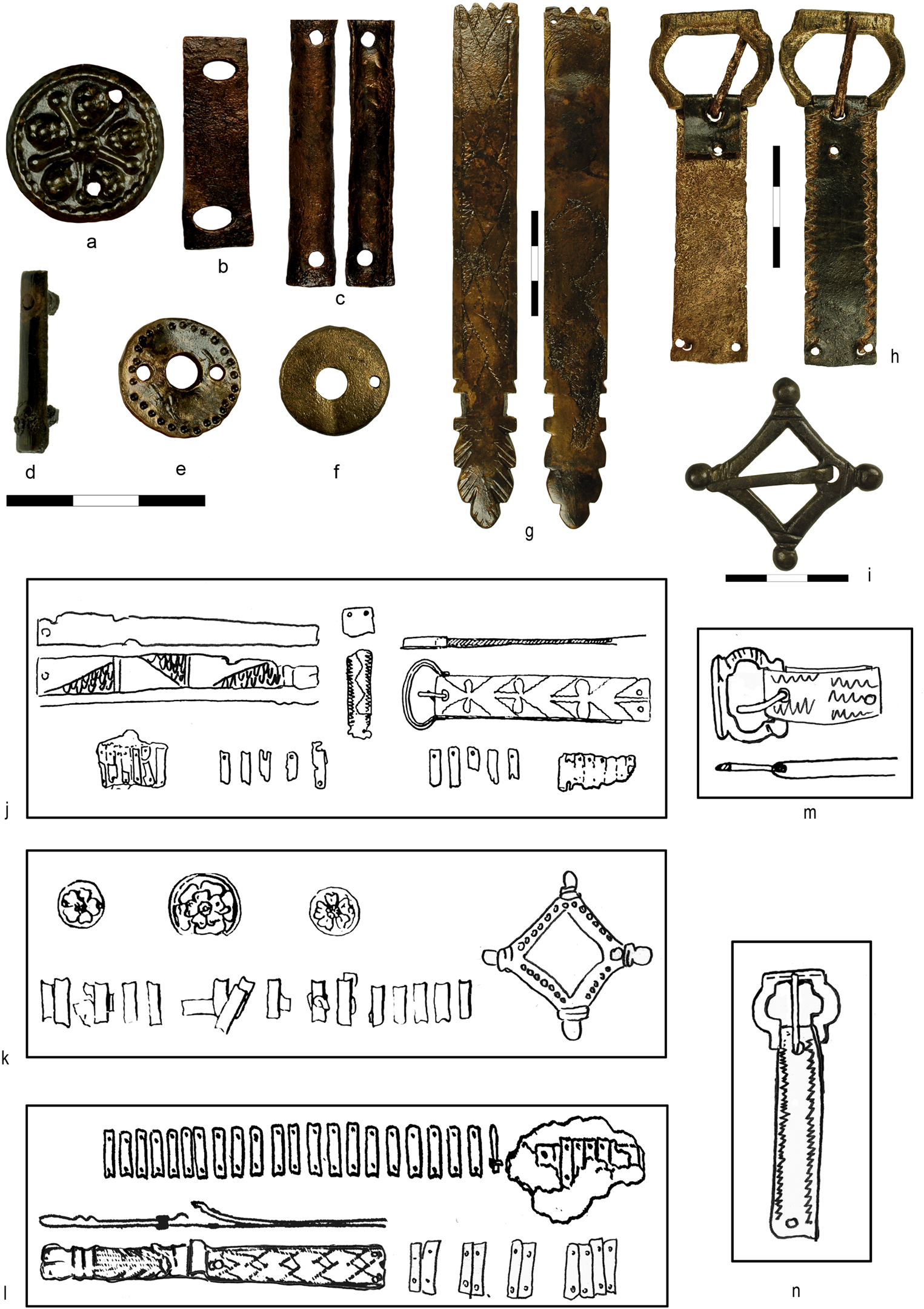

The finds from graves and villages are similar in their forms and motifs (compare Figures 4 and 5; for more examples, see Měchurová, Reference Měchurová1989). This again suggests good access to goods that were most probably manufactured in towns. Simple sheet metal belt mounts seem to be especially common; they occur in the Ducové cemetery (Figure 5) but also in villages (Figure 4h–m) and towns (e.g. Wroclaw: Figure 5b–d). Other items, such as buckles with plates (Figure 5m–n), strap ends (Figure 5g–k), or even brooches (Figure 5i, 5k) are also directly comparable.

Figure 5. Dress accessories. a–i) New Market Square, Wroclaw, (inv. nos. 292, 300, 301, 306, 386, 389, 10, 263, and 448). Burials in the Ducové cemetery: j) artefacts from grave no. 858, juvenile aged between 16 and 18 years; k) artefacts from grave no. 8, juvenile aged between 12 and 14 years; l) artefacts from female grave no. 769; m–n) artefacts from unknown graves. After Sawicki, Reference Sawicki2017 (Wroclaw); Ruttkay, Reference Ruttkay1989 (Ducové). Illustrations redrawn and edited by Jakub Sawicki.

Conclusion

In our evaluation of the value of dress accessories, we noted that the written sources (e.g. testaments) often provide a monetary value for a specific item but without giving any details about its appearance. Hence, comparison with archaeological finds or museum specimens is limited. We suggest that the decorations on dress accessories are secondary in terms of their value, compared to the value of the raw material from which they were made. Most archaeological finds made of copper and tin alloys or iron were common and relatively cheap accessories, even in rural areas. However, we consider, following Howell (Reference Howell2010: 8–17), that the value of an item in the medieval period was not dictated by the market in a modern sense and was not necessarily connected to a monetary circulation system.

Our analysis of the dress accessories found in five excavated villages and two rural cemeteries reveals that the availability and quality of the dress accessories in rural communities are similar to those in urban communities. The finds from villages without strongholds mostly consist of iron buckles, which have also been recovered in urban centres (Sawicki, Reference Sawicki2017). The dress accessories found in the villages with strongholds resemble those known from the towns, and the examples from the cemeteries are identical to those from the urban centres. However, bronze buckles have only been found in villages with strongholds (not only in the strongholds themselves, but also in other neighbouring houses), which suggests better access to such goods. The burial finds might reflect more elaborate, special (mortuary) dress accessories, again suggesting that rural areas had access to such goods and to a certain standard of living.

We suggest that, from a technological point of view, there is little difference between ornamented (engraved) and plain examples made from the same material (Jervis, Reference Jervis2017). Their value may, however, have varied. In villages, the finds are both decorated and plain, whereas in the cemeteries those that are richly decorated dominate. The data from the British PAS documenting a large number of finds of similar quality in rural areas in England and Wales, while not directly comparable, seem to point in a similar direction. This leads us to conclude that access to elements of material culture was quite similar in villages and towns, and that the standards of attire of the rural population were similar to that of the inhabitants of urban areas. This excludes the elite and dress accessories made of silver or gold, which are very rare in archaeological assemblages.

Our interpretations stand in contrast to the hypothesis put forward by Sally V. Smith, who suggests that the unexpectedly good quality of dress accessories in rural areas might reflect the materialization of a resistant identity among the peasantry against the oppression of the local elites (Smith, Reference Smith2009). The increase in rural finds in England and Wales visible in the PAS mostly shows the widespread use of bronze dress accessories outside urban centres. If we consider the urbanization process and urban lifestyle to include the display of status through material culture, we contend that most inhabitants of both towns and villages had access to the same dress accessories, albeit the majority were probably manufactured in towns.

This study is limited by the lack of surface finds from larger rural areas in central Europe and a general lack of publications on dress accessories outside urban centres. Moreover, dress accessories are but a minor part of the whole attire. The fabric used for clothing, the number of garments, or whether they were new or repaired, are likely to have been more important to medieval people than belt buckles. From the entire collection of rural burial finds, there are only seven brooches, which, since they are not utilitarian objects like buckles, could be considered more luxurious artefacts. Finally, although our study has revealed some consumption patterns, we must stress the necessity to acquire more data from different areas to achieve a broader understanding of dress accessories as indicators of value and living conditions in Europe.

Supplementary Material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/eaa.2021.20

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Czech Science Foundation under Grant no. 18-26503S. The authors would like to thank the anonymous reviewers for their comments.