Introduction

After Iron Age Gaul was incorporated into the Roman Empire, it experienced changes in socio-economic organization, including a profound transformation of the agro-pastoral system of production. Indeed, it is assumed that the food supply to the segments of the population not involved in primary production (such as military personnel, civil servants, and craftspeople) depended on the agrarian surplus produced by the rural population. The emergence of larger agricultural estates and changes in land-use strategies, equipment, and storage structures reflect this change (e.g. Roymans, Reference Roymans1996; Ferdière et al., Reference Ferdière, Malrain, Matterne, Méniel and Jaubert Nissen2006; Roymans & Derks, Reference Roymans and Derks2011). New structures relating to the transformation and redistribution of agro-pastoral products also emerged in the network of market places that was set up within the territory of Gaul.

Previous research has shown that major changes in husbandry practices that occurred after the Roman conquest are related to the intensification or expansion of agricultural production, relative specialization in some agro-pastoral products, as well as morphological changes in the animals (e.g. Lepetz, Reference Lepetz1996; Lepetz & Matterne, Reference Lepetz and Matterne2003; Albarella et al., Reference Albarella, Johnstone and Vickers2008; Bakels, Reference Bakels2009; Duval et al., Reference Duval, Lepetz and Horard-Herbin2012, Reference Duval, Lepetz and Horard-Herbin2013; Groot & Deschler-Erb, Reference Groot and Deschler-Erb2015). However, transformations were not uniform throughout the territory, and there was therefore considerable regional diversity. Factors commonly cited to explain these differences include environmental characteristics and soil quality, local populations with different traditions who varied in their acceptance or resistance to Roman innovations, and the exchange networks in which these populations were involved.

In order to explore the influence of these factors on the evolution of husbandry practices during the Early Roman period, I use archaeozoological evidence to examine and compare breeding strategies in several civitates of Gallia Belgica and the western part of Germania Inferior (Figure 1). First, an overview of the existing literature attempts to set changes in breeding practices between the Iron Age and the Roman period in several civitates of Gallia Belgica. Then, I focus on two neighbouring civitates, namely, the Civitas Nerviorum, located in Gallia Belgica, and the loess area of the Civitas Tungrorum, which was initially part of Gallia Belgica and later became part of the province of Germania Inferior. The Roman period in these territories started in 58–50 bc, with the invasion by Caesar's troops. Contacts with Romans before the conquest were very limited in both areas (Brulet, Reference Brulet2008). The capitals of the two civitates, Bagacum (Bavay) and Aduatuca Tungrorum (Tongeren or Tongres), are creations ex nihilo, and proto-urbanization is unknown in these territories in the Iron Age. Both study areas are located in a region covered with Pleistocene loess, where most of the soils are fertile and very suitable for agriculture. These territories were part of the ‘villa landscape’ with a hierarchy of large and medium-sized villae, and single farmsteads (Brulet, Reference Brulet2008; Roymans & Derks, Reference Roymans and Derks2011). However, the two civitates have different cultural backgrounds, were part of different administrative entities, and were involved in different exchange networks. Their material culture shows that there were differences in their assimilation of Roman culture in terms of intensity, timing, and the way in which the Roman model spread (Lepot & Espel, Reference Lepot, Espel and Rivet2010; Lepot, Reference Lepot2014a, Reference Lepot2014b). The civitas of the Tungri became quickly and profoundly acculturated, with a clear influence from the Rhine limes, while that of the Nervii was more influenced by the Belgium of Caesar and by the Atlantic coastal area.

Figure 1. Map of Gallia Belgica and Germania Inferior with the civitates and sites mentioned in the text (based on Raepsaet-Charlier ©CReA-Patrimoine 2011).

Material and Methods

The number of archaeozoological datasets from Roman settlements in northern Gaul has substantially increased in recent decades, mainly through the growth of developer-funded archaeological investigations. However, the corpus varies from region to region, and not all areas are equally well covered. For this research, I selected regions containing balanced data-sets of rural sites, civitas capitals and small towns in order to examine both ‘producer’ and ‘consumer’ sites and to investigate the network of production and exchange of animal products (Pigière & Lepot, Reference Pigière, Lepot, Groot, Lentjes and Zeiler2013).

A large archaeozoological dataset is available for the western part of Gallia Belgica, in particular for the civitates of the Ambiani, Atrebates, Bellovaci, Suessiones, and Viromandui (Figure 1). In addition, several syntheses on animal husbandry in the Late Iron Age (Méniel, Reference Méniel2001; Malrain et al., Reference Malrain, Matterne, Méniel, Ferdière, Malrain, Matterne, Méniel and Jaubert Nissen2006; Méniel et al., Reference Méniel, Auxiette, Germinet, Baudry, Horard-Herbin, Bertrand, Duval, Gomez de Soto and Maguer2009) and the Roman period (Lepetz, Reference Lepetz1996, Reference Lepetz and Van Andringa2007, Reference Lepetz2009; Lepetz & Matterne, Reference Lepetz and Matterne2003; Duval et al., Reference Duval, Lepetz and Horard-Herbin2012) cover the western part of Gallia Belgica. For the eastern part of the province, published data about husbandry practices are scarce (Oelschlägel, Reference Oelschlägel and Benecke2006; Bernigaud et al., Reference Bernigaud, Ouzoulias, Lepetz, Wiethold, Zech-Matterne, Séguier, Reddé and Reddé2016). Regarding the Civitas Nerviorum, the data I have gathered for this study consists of faunal assemblages from the town of Bavay, five small towns, and four rural sites (Table 1 and Figure 1). For the Civitas Tungrorum, the data come from the core area of the civitas, in the loess area, in particular from the town of Tongeren, five small towns, and eight rural sites (Table 1 and Figure 1). In the northern, sandy area of the Civitas Tungrorum, the villa of Hoogeloon is the only site to yield a large enough dataset for inclusion here (Kooistra & Groot, Reference Kooistra, Groot, Roymans, Derks and Hiddink2015). Some of the data were recorded by the author, and some were taken from the literature (Table 1). The compilation of archaeozoological analyses conducted by different researchers inevitably results in problems of comparability due to differences between researchers and the use of different methodologies. However, the effects of these problems appear to be minimal in the context of the current approach, which is to search for broad trends (Groot & Deschler-Erb, Reference Groot and Deschler-Erb2015, Reference Groot and Deschler-Erb2016).

Table 1. Sites of the Civitates Nerviorum and Civitas Tungrorum used in this research

NISP, number of identified specimens. MNE, minimum number of elements.

The focus of this article is on cattle husbandry regimes, for which a large amount of data is available. Various types of archaeozoological data have been used in combination: relative frequencies of species, age profiles, sex ratios, pathologies related to the use of cattle as draught animals, and osteometric data (for a detailed presentation of methods, see Pigière, Reference Pigière2009). To assess the relative importance of the main domesticated mammals (pig, cattle, and sheep/goat), percentages were calculated on the basis of NISP counts, and the results are presented in ternary graphs that allow us to present individual assemblages from the different sites and highlight broad patterns. The data are classified according to the type of site (rural settlement, small town, or urban site). The chronological span ranges from the end of the first century bc to the end of the third century ad. Age-at-death of cattle was established on the fusion of bone epiphyses and/or the eruption and attrition of mandibular teeth. It should be noted that raw data about age-at-death are not always provided in the literature. The results of these analyses are therefore summarized here into three broad age categories designed to reveal the main trends in cattle exploitation. We use the term ‘young’, for individuals younger than 2–3 years; ‘sub-adult’ for animals between 2–3 years and 3–4 years; and ‘adult’ for cattle older than 3–4 years. Bone measurements follow the guidelines of von den Driesch (Reference von den Driesch1976). Sex identification relies on osteometry of the metapodia and the first anterior phalanx (Pigière, Reference Pigière2009). The study of pathologies related to traction relies on the method described by Bartosiewicz et al. (Reference Bartosiewicz, Van Neer and Lentacker1997), which focuses on the bones of the feet.

The osteometric analysis employed the log-ratio method. The log size index (LSI) is the logarithm of the ratio between a measurement ‘X’ and its standard ‘S’, calculated as log (X/S) (Meadow, Reference Meadow, Becker, Manhart, Peters and Schibler1999). The standard used here is a female aurochs from Ullerslev (Denmark) dating from the Boreal period (De Cupere & Duru, Reference De Cupere and Duru2003: 116, table 9). Because Iron Age evidence is scarce for the territories covered by the Nervii and Tungri, a Late Iron Age osteometric dataset derived from sites in the western part of Gallia Belgica was used as a reference for the study of the evolution of cattle morphology (Méniel, Reference Méniel1984). In order to examine more precisely when changes in cattle morphology first occurred, we opted for a fine chronological division at the beginning of the Roman period; the data are therefore grouped into Augusto-Tiberian (5/1bc–ad 15/20) and Claudio-Neronian (ad 40/45–65/70) periods. As for the remainder of the Roman period, the dataset do not allow such fine chronological subdivision, the data are grouped into larger time periods: first century ad, first–second century ad, second–third century ad, third century ad. The Mann-Whitney U test was employed to determine the level of statistical validity of the observed biometrical differences.

Archaeozoological Evidence for Husbandry Practices in Western Gallia Belgica

Major differences are observed between the Late Iron Age and the Roman period in the faunal assemblages from the western part of Gallia Belgica, which covers the civitates of the Ambiani, Atrebates, Bellovaci, Suessiones, and Viromandui. In terms of the relative importance of the three main domesticates, pigs and to a lesser extent cattle are predominant in the faunal assemblages of the Late La Tène period (Méniel, Reference Méniel2001; Malrain et al., Reference Malrain, Matterne, Méniel, Ferdière, Malrain, Matterne, Méniel and Jaubert Nissen2006; Méniel et al., Reference Méniel, Auxiette, Germinet, Baudry, Horard-Herbin, Bertrand, Duval, Gomez de Soto and Maguer2009). From the first century ad onwards, a continuous increase in cattle and a decrease in caprines (sheep/goat) has been recorded in the assemblages from fifty-one rural sites in the area (Lepetz, Reference Lepetz1996, Reference Lepetz2009; Lepetz & Matterne, Reference Lepetz and Matterne2003). It is during the Late Roman period that cattle frequency is at its highest. It has been suggested that agriculture was moderately developed in this loess area during the Roman period (Lepetz & Matterne, Reference Lepetz and Matterne2003), with production focused mainly on hulled wheats (emmer and spelt), and that a relatively large proportion of the land was dedicated to pasture.

The emergence of large-scale butchery and craft activities centred on cattle products are strong indications of the importance of cattle to the animal husbandry in the Roman period (Pigière & Lepot, Reference Pigière, Lepot, Groot, Lentjes and Zeiler2013). Mass production of beef and of cattle-related craft products have been identified on urban sites (Arras, Amiens, Soissons, Beauvais) and small towns (Noyon, Estrée-Saint-Denis; Figure 1) (Oueslati, Reference Oueslati2005; Lepetz, Reference Lepetz and Van Andringa2007, Reference Lepetz2009). Large deposits of thousands of fragments of butchery waste attest to the carcass processing of numerous cattle at these settlements (Oueslati, Reference Oueslati2005: 182). New butchery techniques that are clearly distinguishable from Late Iron Age techniques also appeared during the Roman period. These have been linked with the need to process many animals slaughtered on professional butchery sites over a short period (Lepetz, Reference Lepetz1996, Reference Lepetz and Van Andringa2007; Seetah, Reference Seetah and Matlby2006). This Roman butchery technique has been described for several parts of the northern provinces, and it appears to have been quite homogenous throughout the territory, even if some local variations are recorded (e.g. Maltby, Reference Maltby, Fieller, Gilbertson and Ralph1985, Reference Maltby2010; Lignereux & Peters, Reference Lignereux and Peters1996; Oueslati, Reference Oueslati2005; Seetah, Reference Seetah and Pluskowski2005, Reference Seetah and Matlby2006; Lepetz, Reference Lepetz and Van Andringa2007). In the Iron Age, people used a knife for cutting up the carcass and for filleting, whereas the Roman technique mainly used a cleaver for these tasks, which made it possible to process the carcass more quickly. Roman butchery involves the dismembering of the carcass by systematically chopping into the articulations of the legs and extracting the vertebral column by means of longitudinal chops on either side of the vertebrae. Filleting with the blade of a cleaver also produces distinctive butchery marks. Data from Amiens attest to the existence of a professional butchery in western Gallia Belgica from the mid-first century ad onwards (Lepetz, Reference Lepetz and Van Andringa2007). In a fourth-century butchery at Arras, a study of age-at-death showed that most of the cattle slaughtered were adults older than four years (73 per cent) and that, among them, many cattle were ‘senile’, older than eight years (38 per cent). These animals were not bred in the first instance for their meat; they would have been killed at a younger age, at the latest when they had reached the optimum meat-bearing age, at around three years old. These adult cattle were likely to have been used as draught animals and/or for milk production. Unfortunately, no sex-ratio data are available to further investigate what these animals were bred for. At the same time, the breeding of cattle for their meat is evidenced by the food remains excavated in the civilian occupation deposits from the same period at Arras.

A major increase in the size of cattle and other morphological changes have been documented for northern Gaul, which includes the western part of the Gallia Belgica (Duval et al., Reference Duval, Lepetz and Horard-Herbin2012, Reference Duval, Lepetz and Horard-Herbin2013). Duval et al.’s studies, based on a dataset of around 12,000 bones, shows a slow and continuous increase in the size of cattle as early as the Middle La Tène period, but in the Augustan period it grows dramatically and at very different rates compared to previous centuries (Duval et al., Reference Duval, Lepetz and Horard-Herbin2012, Reference Duval, Lepetz and Horard-Herbin2013: fig. 7). During the first century ad, the mean reconstructed withers height of cattle increases markedly from 1.12 m to 1.2 m, with some individuals reaching 1.52 m. By the end of first century ad, larger animals are dominant and the smallest cattle have disappeared. From the mid-second century onwards, there is only a slight increase in cattle size (mean withers height from 1.26 to 1.32 m) and in general the size of the new population appears to have stabilized. But the slenderness indices begin to increase, reflecting selection for stronger animals.

Regional comparisons have shown that the dynamics, nature, and scale of the morphological transformations vary greatly between different areas in northern Gaul (Duval, et al., Reference Duval, Lepetz and Horard-Herbin2012: fig. 26). Two main trends are encompassed in this diversity. In some civitates, alongside the development of herds of medium size cattle, a group of larger animals also appears. The larger cattle show new morphotypes, which suggests that very large individuals were imported into Gaul, perhaps for breeding. In other civitates, a slow and continuous increase in size is recorded and it appears to be the result of the amelioration of indigenous herds.

Within these general patterns, there were cattle of different sizes in the various civitates of the western part of the province of Gallia Belgica throughout the Roman period. Larger cattle are present in the civitates of the Atrebates, Bellovaci, and Remi, while smaller cattle are recorded in the civitas of the Ambiani. The greatest mean withers heights for cattle are recorded from rural sites rather than urban sites in most civitates. This suggests that the function of cattle is related to morphotype, with a predominance of large, working beasts on rural sites, linked to their use in agricultural activities. In addition, a correlation between cattle size and type of rural site in the civitates of the Atrebates and Menapi has shown that large cattle are more frequent on villae, while smaller cattle are more abundant on farms (Oueslati, Reference Oueslati2015). It therefore appears that villae, being highly Romanized places, were at the pinnacle of zootechnical innovations to produce powerful draught animals (Oueslati, Reference Oueslati2015).

In the eastern part of the province, the few rural faunal assemblages from a microregion in the Moselle area in the civitas of the Mediomatrici are also dominated by cattle (based on six sites, NISP = 882; Bernigaud et al., Reference Bernigaud, Ouzoulias, Lepetz, Wiethold, Zech-Matterne, Séguier, Reddé and Reddé2016). Because remains of pig dominate in the food refuse of the nearby town of Divodurum (Metz), Bernigaud et al. (Reference Bernigaud, Ouzoulias, Lepetz, Wiethold, Zech-Matterne, Séguier, Reddé and Reddé2016) argue that surplus production in the surrounding countryside was geared towards pigs. However, because faunal evidence shows that large-scale cattle butchery also took place at Divodurum (Lepetz, Reference Lepetz2009), I would argue that the possibility of surplus production based on cattle cannot be overlooked. Moreover, because the processing of cattle took place in professional butcheries, their remains will be underrepresented in the domestic refuse dumps of the town, and this difference in disposal between the remains of pigs and cattle makes it difficult to compare their relative importance. Pig remains also dominate in domestic dumps at other urban sites in Gallia Belgica, namely Amiens, Saint-Quentin, Arras, and Boulogne (Lepetz, Reference Lepetz and Binet2010).

Among the small towns in the eastern part of Gallia Belgica, the proportions of the main domesticated animals differ. At the vicus of Wallendorf, cattle and pigs are dominant, while at Bliesbrück, pigs and caprines predominate (Oelschlägel, Reference Oelschlägel and Benecke2006). Close to Bliesbrück, at the villa of Reinheim, pigs are the main meat provider of its rich inhabitants. The data collected in the pars rustica of that villa, which should better reflect the production of the villa than the pars urbana, indicate that both pigs and caprines are prevalent. At the villa of Borg, in the Moselle valley, the same consumption patterns as Reinheim are recorded for the inhabitants of the pars urbana. However, in this case, cattle are the most frequent species in the pars rustica.

Archaeozoological Evidence for Husbandry Practices in the Civitas Nerviorum

In the north-eastern part of Gallia Belgica, in the Civitas Nerviorum, cattle appear to be important in the animal economy during the Early Roman period, as shown by the presence of large-scale butchery and craft activities involving cattle products in the town of Bavay and the small towns of Asse, Waudrez, and Famars (Figure 1). At Bavay, several deposits of butchery waste attest to this activity from the first century ad onwards (Oueslati, Reference Oueslati2005; Merkenbreack, Reference Merkenbreack2013). At Asse, huge quantities of butchery remains (in the form of cattle horn cores and foot bones) dated to between the end of the first and the third centuries ad were used in the foundation of a road (Ervynck et al., Reference Ervynck, Van Neer, Lentacker, Derreumaux, Degryse and Biesbrouck2013). At Waudrez, an accumulation of trimmed scapulae and split bones in a well indicate that smoked ham and glue were being produced in the second half of the third century ad (Gautier & Ingels, Reference Gautier and Ingels2003). Finally, at Famars, a refuse dump with an estimated surface area of 200 m2 contained the same kind of waste from glue production (Clotuche, Reference Clotuche and Clotuche2013). Other large rubbish deposits from Famars are currently being investigated and are expected to provide evidence about other craft activities based on cattle products (R. Clotuche, pers. comm.).

Cattle are also largely dominant in the consumption refuse of the inhabitants of all small towns (40–80 per cent) and one villa (49 per cent) (Figure 2) in the Civitas Nerviorum. Cattle are also abundant (44 per cent) in the assemblages of a rich domus at Bavay, where they are nearly as frequent as pig (48 per cent), in line with the consumption pattern of rich inhabitants, which is usually characterized by a higher proportion of pig than cattle. The food selection of the wealthy inhabitants of the southern villae of the civitas is also reflected in the high proportion (47–57 per cent) of pig recorded there, as most of the data come from the pars urbana. At Bruyelle, data from the pars rustica show the importance of pig (39 per cent) and of caprines (43 per cent) in the production of the villa. A relatively high proportion of pigs (39–43 per cent) is also recorded in the small towns of Waudrez and Tournai, which could confirm that pig husbandry was significant in the southern part of the civitas.

Figure 2. Relative proportions of pigs, cattle, and caprines in the Civitas Nerviorum (NISP = 9.400).

Although the data are still limited, it seems that cattle husbandry regimes directed towards different products were practised in the Civitas Nerviorum (Table 2). For small towns (Asse, Famars, Tournai), the age-at-death of the cattle indicates that mainly adult cattle were consumed. These would have been bred as draught animals or for milk production. In some villae, some of the cattle were also adults, and the rest were sub-adults presumably bred for meat (Bruyelle and Meslin). At the villa of Erps-Kwerps, a majority of sub-adults points to meat production.

Table 2. Summary of information about age-at-death at the Civitas Nerviorum and Civitas Tungrorum.

So far, no information had been available about the morphological changes in cattle in the Civitas Nerviorum between the Iron Age and the Roman period. The dataset I have assembled for the territory of the Nervii makes it possible to compile the width measurements of cattle bones and thus provide the first substantive information documenting size changes in this civitas (Figure 3). A sharp increase in width measurements is recorded in the first century ad compared with the Late Iron Age. A further increase is visible in the third century, which suggests a progressive and continuous increase in the size of cattle in the civitas throughout the Early Roman period. These changes are statistically significant (Table 3).

Figure 3. Chronological changes in width measurements of cattle bones (LSI) in the Civitas Nerviorum.

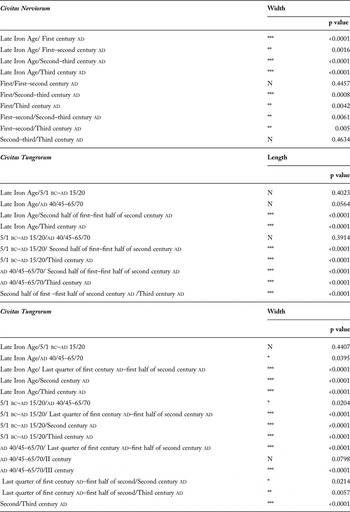

Table 3. Width measurements of cattle bones (LSI) at the Civitas Nerviorum, length and width measurements of cattle bones (LSI) at the Civitas Tungrorum: results of Mann-Whitney U-test.

N, not significant; * significant at 95 per cent confidence interval; ** significant at 99 per cent confidence interval; *** significant at 99.9 per cent confidence interval.

Archaeozoological Evidence for Husbandry Practices in the Civitas Tungrorum

Most archaeozoological data available for the civitas of the Tungri comes from the central area. In this region, cattle played an important role in the animal economy in the Early Roman period, as shown by the occurrence of large-scale butchery and craft activities related to cattle in several small towns and at the urban site of Tongeren (Figure 1 and Table 4). At Liberchies, a professional butchery site and several craft activities—producing smoked ham, making glue, tanning, and probably horn-working — were present in a craft area where features dedicated to tannery activities have been excavated (Lentacker et al., Reference Lentacker, Pigière, Vilvorder, Brulet, Dewert and Vilvorder2001). At Tongeren, the location of such activities in the backyard of a rich domus suggests that the élite were involved (Vanderhoeven & Ervynck, Reference Vanderhoeven, Ervynck, Hingley and Willis2007).

Table 4. Large-scale butchery and craft of cattle products in the core area of the Civitas Tungrorum.

NISP; number of identified specimens; MNE; minimum number of elements.

The importance of cattle in the meat provisioning of urbanized sites is also reflected in the food refuse of the inhabitants of the town of Tongeren and all small towns where cattle are largely dominant (urban centre: 49–73 per cent; small towns: 41–76 per cent; Figure 4). In addition, faunal assemblages associated with wealthy inhabitants in urban centres are distinguished by a high proportion of pigs (Pigière, Reference Pigière, Roymans, Derks and Hiddink2015b). The dominance of cattle is also recorded in the rural sites, where we see more of an emphasis on cattle (37–72 per cent) compared to pigs (13–41 per cent) and caprines (13–33 per cent) during the first and second centuries ad. Cattle are also dominant in the faunal assemblage from the villa of Hoogeloon (57 per cent), located in the northern, sandy area of the civitas. It has been suggested that this site functioned as a central collecting point for surplus cattle produced by the rural sites of the region (Kooistra & Groot, Reference Kooistra, Groot, Roymans, Derks and Hiddink2015). During the third century there is an increase in pig (42–54 per cent) and a decrease in cattle (12–34 per cent) in the rural sites of the central loess area (Figure 4). A similar shift is not recorded in the urbanized sites (urban centre and small towns) in the third century, where cattle are still dominant, but it did take place in the Late Roman period, from the fourth century onwards, while at the same time cattle butchery sites are no longer recorded (Pigière, Reference Pigière2009). A possible decrease in cattle and an increase in caprines may be related to the economic crisis of the third century, as has been postulated for the vicus of Tienen (Ervynck et al., Reference Ervynck, Van Neer, Lentacker, Derreumaux, Degryse and Biesbrouck2013), but this trend needs to be confirmed with more data.

Figure 4. Relative proportions of pigs, cattle, and caprines in the Civitas Tungrorum (NISP= 20.289).

Cattle breeding seems to have had several purposes in the core area of the Civitas Tungrorum in the Early Roman period. On both rural and urban sites, young and sub-adult animals bred for meat, and adult animals bred for use as draught animals, or possibly for milk, are attested (Table 2). In order to further investigate the purpose for which adult individuals were used, the sex-ratio of the large bone assemblages from Namur and Maastricht and from the material linked to craft activities at Liberchies has been analysed (Table 2). These assemblages comprise a high proportion of males (68–74 per cent), and among them numerous large oxen castrated at a young age (Pigière, Reference Pigière, Roymans, Derks and Hiddink2015b). The kill-off patterns and the high frequency of males suggest that a majority of adult cattle were bred for use as draught animals. To determine the extent to which these animals were used for traction, mean pathological indices (PI) have been calculated for the first anterior phalanges of cattle in these assemblages (Pigière, Reference Pigière, Roymans, Derks and Hiddink2015b). Compared with a modern population used exclusively as draught animals (PI=100 per cent), a relatively high mean index has been recorded for Roman cattle at the three sites (per cent PI between 54 and 66). This suggests a relatively intensive exploitation of cattle as draught animals. The pathological indices have also been calculated separately for the large individuals identified as oxen. The indices of these individuals are even higher (per cent PI between 53 and 73), suggesting an intensive use of these oxen as draught animals.

On the basis of the dataset I collected for the core area of the Civitas Tungrorum, it is possible to follow changes in cattle size throughout the Roman period (Figure 5). No morphological changes are detected between the Late Iron Age and the Augusto-Tiberian period (5/1 bc–ad 15/20), although it should be noted that larger cattle are represented in slightly greater quantities in the later assemblages. The first changes appeared during the Claudio-Neronian period (ad 40/45–65/70), when very large individuals occur alongside a majority of smaller individuals. A dramatic increase in the mean size is recorded during the second half of the first century and second century ad, and a further increase is visible in the third century. Therefore, there appears to have been a steady development, characterized by a general increase in stature and a growing proportion of larger animals, although small cattle did not disappear completely. When we examine the width measurements, we can detect the same trend (Figure 6). An increase in width measurement values is recorded from the Claudio-Neronian period onwards, and herds with larger body sizes emerge. This trend intensified at the end of the first century and first half of the second century ad, and once again during the third century. Small-sized cattle are maintained throughout the period, although in lower numbers. All changes are statistically significant (Table 3).

Figure 5. Chronological changes in length measurements of cattle bones (LSI) in the Civitas Tungrorum. IB, second half of first century ad.

Figure 6. Chronological changes in width measurements of cattle bones (LSI) in the Civitas Tungrorum. Ic, last quarter of first century ad; IIA, first half of second century ad.

Discussion

Cattle play an important role in the Early Roman animal economy of the western part of Gallia Belgica and in the civitates of the Nervii and Tungri. Several indices suggest that the emergence of the breeding of large cattle is a response, in the first instance, to the need for powerful draught animals for agricultural activities. The breeding of large animals may also be a response to the requirement for more meat and other by-products in a context of increasing demand from ‘consumer’ sites. In Gallia Belgica, however, the higher frequency of large cattle on rural sites compared to those found on urban sites suggests that larger animals were kept on farms for use in agricultural activities, while the smaller ones were sent to feed the urban population (Duval et al., Reference Duval, Lepetz and Horard-Herbin2012). Moreover, in the Civitas Tungrorum, the demographic data combined with the study of pathologies related to traction show the specialized use of large cattle as draught animals and not primarily as beef cattle. The need for more powerful animals that can plough heavier soils matches other evidence—changes in land use, more specialized crop production, developments in equipment and storage structures (Roymans, Reference Roymans1996; Kooistra, Reference Kooistra1996; Bakels, Reference Bakels2009; Roymans & Derks, Reference Roymans and Derks2011)—of an intensification of agricultural activities in the fertile loess region in the Early Roman period. In addition, data about age-at-death in several civitates demonstrate the existence of cattle breeding for meat production, with animals mainly slaughtered when they reached the optimum meat-bearing age. The intensive exploitation of cattle in professional butcheries and in craft activities in the urban sites and small towns of Gallia Belgica and western Germania Inferior suggests that market economy was focused on cattle. This provides an indirect indication of the surplus produced by the countryside to supply cattle to the urbanized sites. Moreover, several civitates of Gallia Belgica have yielded evidence that the supply of meat to urban sites also relied on the rural surplus production of pigs. At the other end of the spectrum, in the capital of the Tungri, a high proportion of pigs appears only in the diet of wealthy inhabitants, whereas cattle are dominant in the city's general food waste deposits.

In the western part of Gallia Belgica, cattle grow in importance on rural sites during the Late Roman period. The territory of the Tungri follows a different trend, with cattle seemingly decreasing while the proportion of pigs increases in the countryside from the third century ad onwards. During the Late Roman period, the proportion of cattle also drops dramatically and pigs become predominant in the urbanized sites of the Civitas Tungrorum (Pigière, Reference Pigière2009). The decrease in importance of cattle in the Late Roman period is further suggested by the absence of evidence for professional cattle butchery. Indeed, cattle butchery has so far not been identified after the third century ad in the Civitas Tungrorum, whereas several Late Roman butchery sites are known from western Gallia Belgica (Oueslati, Reference Oueslati2005; Lepetz, Reference Lepetz and Van Andringa2007, Reference Lepetz2009).

The emergence of large cattle is documented in all geographical areas considered in this study. However, patterns of cattle size increase differ between western Gallia Belgica and the Civitas Tungrorum. Changes in cattle morphology occur later in the Civitas Tungrorum than in western Gallia Belgica: in the latter, a major transformation already occurs during the Augustan period, whereas in the former changes only begin to appear in the Claudio-Neronian period. Moreover, there are variations in the timing of morphological changes throughout the Early Roman period. Cattle withers height increased continuously until the third century ad in the Civitas Tungrorum, while in the western civitates the tallest herds existed during the second century and there are no significant size changes after this time. Finally, a significant proportion of smaller-sized cattle was maintained throughout the Early Roman period in the Civitas Tungrorum. In the Civitas Nerviorum, the same continuous increase in height is recorded through the Early Roman period.

Conclusion

In the fertile loess area of Gallia Belgica and western Germania Inferior, cattle breeding developed during the Early Roman period to respond to a growing demand for powerful cattle for traction and transport and for supplying ‘consumer’ sites with meat and other by-products. Despite these common trends, several aspects of animal husbandry differ between the civitates of western Gallia Belgica and those of the Nervii and Tungri. Several civitates in Gallia Belgica, including that of the Nervii, appear to be distinguished from the Civitas Tungrorum by more intensive pig husbandry during the Early Roman period. Food patterns were more orientated towards pork in the towns of Gallia Belgica, whereas the capital of the Tungri shows stronger beef consumption patterns. These patterns reflect differences in the surplus production of the countryside in these two areas, which suggests that different types of agricultural specialization existed inside the loess area.

The sharp decrease in cattle in the Civitas Tungrorum during the Late Roman period appears to reflect a reduction in the demands of the market on rural production and could reveal the major role the market played in the orientation of agricultural production. A different trend is visible in western Gallia Belgica, where cattle husbandry seems to increase during the Late Roman period.

The process of integrating Roman agricultural innovations related to morphological changes in cattle appears to start earlier in western Gallia Belgica than in western Germania Inferior. However, it should be stressed that so far there is no evidence of a difference in the extent and timing of cattle size increases between the Civitas Nerviorum and the Civitas Tungrorum. In contrast to other material culture, this aspect of husbandry practices reveals no differences in how the two civitates assimilated Roman culture.

Acknowledgements

The study presented here was carried out with the financial support of the Service de l'Archéologie du Service public de Wallonie (DGO4).