Introduction

Food is the basis of life, and its procurement, consumption, and digestion have many interactions with the cultural, biological, psychological, social, and economic development of mankind. The development of an ‘archaeology of food’ over the last three decades, especially in relation to the social diversity or determination of alimentation (Twiss, Reference Twiss2012), is a result of previous developments in cultural anthropology and sociology. One of the ideas driving these studies, championed in particular by Mary Douglas, was to establish a relationship between social determination and foodways. Douglas has shown in several studies that alimentation was governed by strict, socially enforced rules (Douglas, Reference Douglas1972, Reference Douglas2002). She identified the same ‘rules of holiness and cleanliness’ in social relations at the very core of societies with regard to the selection of food. ‘If food is treated as a code, the message it encodes will be found in the pattern of social relations being expressed’ (Douglas, Reference Douglas1972: 61). It is clear that Douglas' thoughts, derived from an in-depth study of Leviticus, should not be uncritically applied to prehistoric contexts, for there the pattern of social relations is a priori unknown.

There is, however, a tendency within archaeological studies dedicated to food to fill in the blanks with hypotheses based on ethnographical or sociological evidence (Twiss, Reference Twiss2012, with bibliography). One of the sociological concepts most abundantly used to interpret the archaeological evidence for foodways is feasting (e.g. Richard & Thomas, Reference Richards, Thomas, Bradley and Gardiner1984; Dietler, Reference Dietler, Wiessner and Schiefenhövel1996; Benz & Gramsch, Reference Benz and Gramsch2006; Twiss, Reference Twiss2008; Dietler & Hayden, Reference Dietler, Hayden, Dietler and Hayden2010; Hayden, Reference Hayden, Dietler and Hayden2010; Aranda Jiménez et al., Reference Aranda Jiménez, Montón-Subías and Sánchez Romero2011; Hayden & Villeneuve, Reference Hayden and Villeneuve2011; Pollock, Reference Pollock2015), a social practice with a good potential of being visible in the archaeological record, since it includes a quantitative and possibly qualitative selection of food and meals in comparison to everyday meals.

The act of feasting is defined here, following Hayden (Reference Hayden, Dietler and Hayden2010: 28), as ‘any sharing between two or more people of special foods in a meal for a special purpose or occasion’. This definition is very broad and can refer to a large spectrum of situations that archaeologists subjectively perceive as ‘special’, whether due to a high degree of visibility in the archaeological record, or to conspicuous structuring, or to the presence of specific finds. Despite the basic problem of categorizing something as ‘special’, lists with indicators for recognizing signs of feasting in archaeological contexts have been elaborated, again largely drawing on ethnographic evidence (Twiss, Reference Twiss2008; Hayden, Reference Hayden, Dietler and Hayden2010: 40–41, tab. 2.1). It has been stressed, however, that structured deposits of food residues not only relate to feasting, but may also reflect a variety of human behaviours (e.g. Hill, Reference Hill, Anderson and Boyle1996; Pollard, Reference Pollard, Mills and Walker2008; Gifford-Gonzales, Reference Gifford-Gonzalez2014). Modern refuse dumps, which are organized according to the principles of waste separation, are a prime example here (Rathje & Murphy, Reference Rathje and Murphy2001). The interpretation of structured deposits is further complicated by difficulties in appreciating the amount of time involved in their formation. A chronological ‘fuzziness’ may be inevitable and is often ignored in interpretations (e.g. Ickerodt, Reference Ickerodt, Reinhold and Hofmann2014). This may result in a static perception that neglects the dynamic of cultural processes behind archaeological features (see for example Binford, Reference Binford1981; Schiffer, Reference Schiffer1987; Sommers, Reference Sommers1991).

The present study endeavours to approach the question of feasting in the context of social structures in Late Bronze Age Eastern Europe. It focuses on a cultural phenomenon called the Noua-Sabatinovka culture (NSC hereafter), which appears over an immense territory between eastern Transylvania and the Volga Basin, roughly between 1500 and 1000 bc. This huge area encompasses a large variety of landscapes, from flat plains to more hilly terrain. In the northern regions the forest-steppe is typical and the southern regions are part of the Eurasian Steppe Belt. Approximately 600 NSC sites are known from this area (Florescu, Reference Florescu1964; Sava, Reference Sava2005a). Most of these are settlements. Characteristic features are the so-called ‘ashmounds’, which are round, grey structures near the settlements (see below). Cemeteries are also located close to the settlements; typically, they are large cemeteries with flat inhumation graves, more rarely with burial mounds. Further, metallurgy is abundantly associated with the NSC, expressed in the archaeological record by numerous hoards with tools, weapons, and ornaments, and through traces of metallurgical activity in the settlements. ‘Ashmounds’ are visible on aerial photographs as grey, round to oval features of up to 60 m in diameter, often in groups of up to thirty (Bicbaev & Sava, Reference Bicbaev and Sava2004; Sava & Kaiser, Reference Sava and Kaiser2011: 56, fig. 12). Their designation derives from the usual interpretation of these structures as mounds of ash that accumulated on the occupation levels of settlements (Sava, Reference Sava2005a; Dietrich, Reference Dietrich, Heske and Horejs2012, Reference Dietrich, Ailincăi, Ţârlea and Micu2013). Interpretations of their function vary widely and range from refuse heaps (Smirnova, Reference Smirnova, Zlatkovskaja and Meljukova1969; Dragomir, Reference Dragomir1980) to settlement structures (Sava & Kaiser, Reference Sava and Kaiser2011; Dietrich, Reference Dietrich, Heske and Horejs2012). Apart from the erroneous identification of the sediment making up the mounds as being ash, one of the main issues pertaining to earlier research on ‘ashmounds’ is that they are based exclusively on the excavation of the mounds themselves (Sava & Kaiser, Reference Sava and Kaiser2011), with the surrounding areas remaining unexplored.

Thus, it is hardly surprising that recent studies have raised questions about many basic assumptions (Sava, Reference Sava2005a; Dietrich, Reference Dietrich2014: 197–206, 288–96). First, chemical analysis has shown that the mounds are not made up of ash at all, but instead of a sediment rich in lime with an ash-like appearance. Further, the heaps did not accumulate on the surface, but accumulated intentionally in basins dug in the outer perimeter of the settlements. These fresh insights lead to a completely new understanding of these mysterious structures.

The ‘Ashmound’ at Rotbav

Recent excavations at the Bronze Age settlement of Rotbav in south-eastern Transylvania have yielded new information (Figure 1, top; Dietrich, Reference Dietrich2014, with a complete list of preliminary reports). The settlement lies on a high terrace of the river Olt; it was excavated in 1970–1973 (by Alexandru Vulpe and Mariana Marcu) and again in 2005–2013 (by Laura Dietrich, Oliver Dietrich, and Alexandru Vulpe) (Figure 1, bottom). The settlement comprises a sequence of six strata dating to between the early Middle Bronze Age and the Early Iron Age. Radiocarbon dates lie between the nineteenth/eighteenth and the twelfth centuries bc. The earliest three layers (Rt. 1–3) belong to the so-called Wietenberg culture of the Middle Bronze Age (Boroffka, Reference Boroffka1994; Dietrich & Dietrich, Reference Dietrich and Dietrich2011). The following two layers (Rt. 4–5) belong to the NSC, while the latest intact stratum (Rt. 6) belongs to the Gáva culture.

Figure 1. Location of Rotbav (top). Three-dimensional model of the settlement and plan of the excavated areas (bottom).

The ‘ashmound’ belongs to the earlier NSC settlement (Rt. 4). It was not heaped upon the walking surfaces of this layer, but lies within a round-oval basin. The basin has a reconstructed diameter of 25–30 m and a depth of 30–50 cm (Figure 2). It was dug into the natural, yellowish loamy soil, and earlier settlement debris (Rt. 1–3) was deliberately and completely removed. The mound was erected only later and is not the primary attribute of the feature.

Figure 2. Section through the ‘ashmound’ (top). Reconstruction of its original position in the settlement (bottom).

The basin is situated on the southern border of the settled area excavated so far (Figure 1, bottom). The contemporaneous settlement (Rt. 4) and the later NSC layer (Rt. 5) are characterized by houses with beaten earth floors; fireplaces and pits are positioned outside. The nearest house structure stands 20 m to the north of the ‘ashmound’. It is represented by a partially preserved burnt loam floor. Another house with accompanying fireplace and pits is located further to the north. Six more houses exist to the west and to the east, at some distance; their exact chronological position (Rt. 4 or 5) is unclear. At least some of them could be contemporary with the ‘ashmound’. Pits are spread all over the plateau. The area south of the ‘ashmound’ has not been excavated so far; nevertheless, a fortuitous find of a cist grave indicates that there is a contemporaneous cemetery in this area (Dietrich & Dietrich, Reference Dietrich and Dietrich2007).

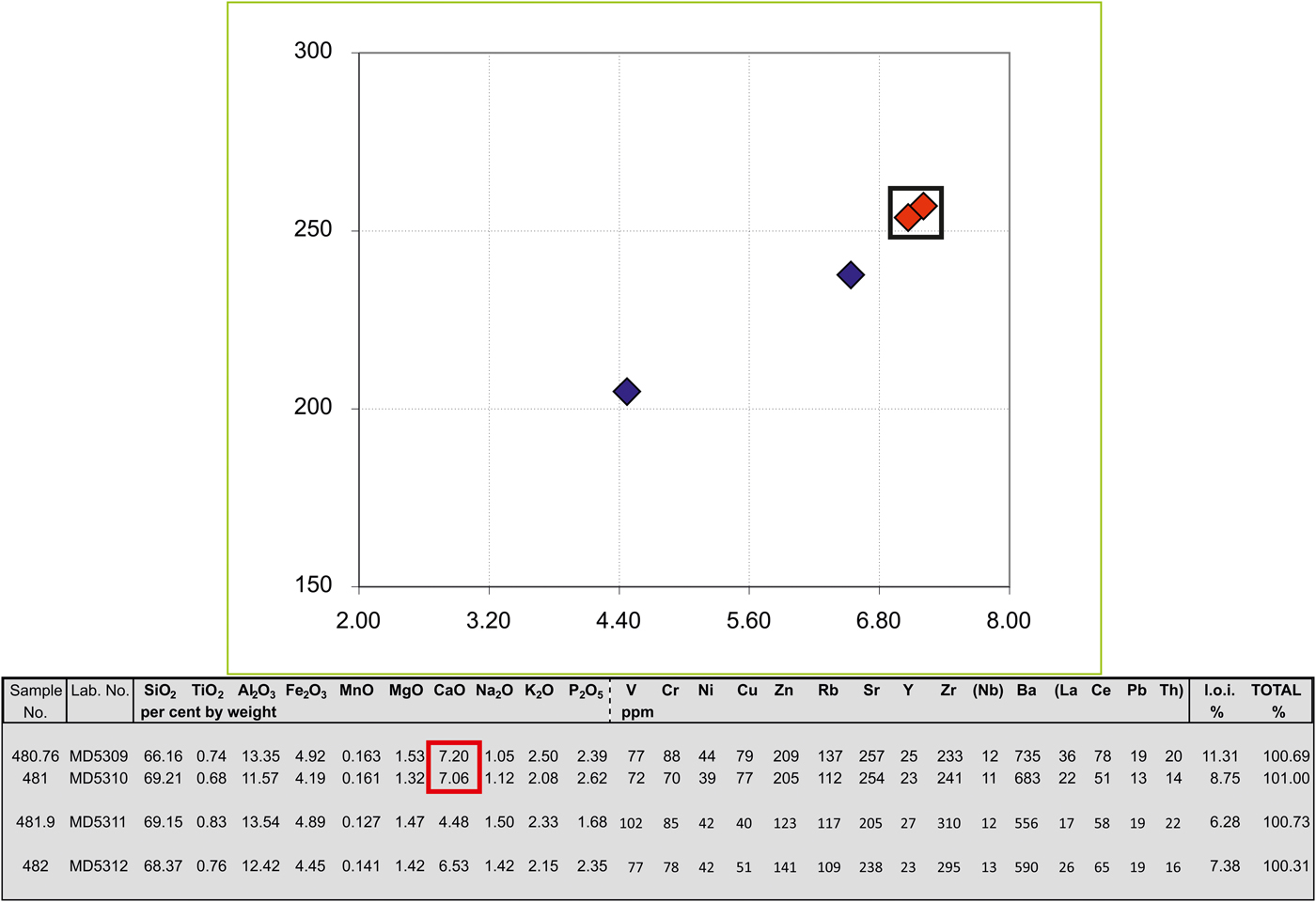

The sediment of the ‘ashmound’ is quite hard and light grey to white. Chemical analysis of this layer by wavelength-dispersive X-ray fluorescence (WD-XRF) was conducted to determine the major elements that compose it, including phosphorus, and a rough estimation of sulphur and chlorine (Figure 3). The samples from the ‘ashmound’ (MD5309 and MD5310) can be clearly differentiated from the surrounding area (MD5311) by their CaO (burnt lime) content. Contents of Na2O, Cu, Zn, and Zirconium also differ, and additionally CaCO3 (calcium carbonate) has been identified. Analysis of the ‘ash’ from the mounds at Odaia Miciurin in Moldavia (Daszkiewicz & Schneider, Reference Daszkiewicz, Schneider, Sava and Kaiser2011; Facklam, Reference Facklam, Sava and Kaiser2011; Sava & Kaiser, Reference Sava and Kaiser2011: 414, tab. 28) and Coslogeni in Romania (Dobrinescu & Haită, Reference Dobrinescu and Haită2005) has yielded similar results, indicating in general that the ‘ashmounds’ of the NSC were most probably not composed of ash.

Figure 3. Chemical analysis by wavelength-dispersive X-ray fluorescence of the sediment from the ‘ashmound’. Graph by M. Daszkiewicz and G. Schneider.

At Rotbav, the lime-rich sediment was densely packed with finds, giving the ‘ashmound’ the appearance of a massive accumulation of food remains and artefacts. Animal bones, pottery fragments, and tools for food processing constitute the greatest part of the finds. In addition, a large number of tools for working hides (so-called crenated scapulae, with notches around the edge of the scapulae's articular surface; Figure 4) were found. The finds differ clearly in number and type from those found in domestic spaces, while the recovery methods were the same for the settlement area and the ‘ashmound’. Weapons as well as certain classes of tools (see below) and ornaments are almost entirely absent from the ‘ashmound’. The finds from the mound are mainly connected to food (Table 1). This structuring and the mound's conspicuous position at the edge of the settlement suggest that this feature played a special role. Hence, for a more in-depth analysis, the criteria elaborated by Twiss (Reference Twiss2008: 420–22, tab. 1) for recognizing feasting in the archaeological record have been applied to the situation in Rotbav.

Figure 4. Crenated scapulae from Rotbav, showing notches cut around the edge of the scapulae's glenoid cavity.

Table 1. Comparison between finds from the ‘ashmound’ and the settlement at Rotbav.

One criterion, the use of special locations, is evident, in view of the deliberate placement of a large oval basin on the periphery of the settlement. Another criterion, the consumption of large quantities of food and drink, is difficult to assess due to the possible chronological biases outlined above. The time span during which the mound was formed is not entirely clear (see above). However, the dense packing of food remains and domestic pottery hints in the direction of large-scale consumption. The pottery vessels from the ‘ashmound’, all fragmented, are mainly coarse, open, situla-shaped pots with heights between 18 and 24 cm, some decorated with applied strips with thumb impressions, and large open bowls with diameters of up to 50 cm (Figure 5). Similar forms are attested in the settlement but in considerably smaller quantities. Calculated for the same surface and depth, the amount of pottery is four times higher in the ‘ashmound’. If one assumes that feasting was a key factor in the formation of the mound, an explanation for this marked difference could lie in the specific production of standardized, large vessels to provide for the needs of a larger group of people.

Figure 5. Coarse and fine wares from the ‘ashmound’ at Rotbav.

A further sign of feasting is the consumption of drink. In the case of the ‘ashmound’, this is proven by a specific kind of drinking vessel: one- or two-handled cups (so-called kantharoi). With their shiny, black polished surface and zoomorphic knobbed handles they represent the main form of the NSC's fine wares (Figure 5). They are rare in the settlement area (Dietrich, Reference Dietrich2014: 291, fig. IX.7), and their main occurrence outside the ‘ashmound’ is in graves (Sava, Reference Sava2002: 150, fig. 46). Another indicator of large-scale food processing is the great number of cooking stones with traces of fire found in the ‘ashmound’ (Figure 6, left). The stones are not worked, but were obviously chosen for their size. They were heated in open fires; their main function seems to have been to warm up liquids, in pots or perhaps also in animal hides (for historic and ethnographic comparison, see Dittmann, Reference Dittmann1990, especially 183–303).

Figure 6. Cooking stones and clay balls from Rotbav.

The density of cooking stones found in the ‘ashmound’ is 14 stones per m2, whereas in the settlement area they appear only sporadically. In domestic spaces another kind of cooking equipment prevails: balls made of non-tempered clay that are similar in form and size to the stones (Figure 6, right), but considerably lower in number. They were found predominantly in pits and in the spaces near the houses and only rarely in the houses. The conchoidal fractures on their surface indicate several cycles of intense heating and rather abrupt cooling (Dittmann, Reference Dittmann1990: 114–15). With traces of fire being absent, the clay balls seem to have been heated carefully and away from an open fire. These clear differences between cooking stones present in the ‘ashmound’ and clay balls in domestic spaces may well indicate different cooking techniques and a different degree of care during the process. The use of clay balls involves greater effort: they had to be made, not just collected like stones. The reason for investing additional effort is most probably because the clay balls offer certain advantages. They do not lose particles when cooling, as many rocks do (Dittmann, Reference Dittmann1990: 116–17, 310), and obviously they can be re-used many times. They are dedicated cooking devices used in daily life and were carefully stored in pits. Cooking stones, however, seem to be ad hoc items used only once. The reason for their use could lie in the rapid preparation of large amounts of food, in situations where the production of clay balls would have been too time-consuming. Further arguments for the interpretation of the ‘ashmound’ are provided by archaeozoological data. Nearly 12,000 animal bones from the settlement have been analyzed; this is one of the largest assemblages available thus far for the Transylvanian Bronze Age. The first important fact, already easily observable during excavation, is that the density of bones found in the ‘ashmound’ is twelve times greater than that found in the settlement. This dense packing suggests that larger amounts of bones were deposited simultaneously.

Twiss (Reference Twiss2008: 429, tab. 4) has highlighted a preference for large animals in feasting events in ethnographic contexts. Regarding animal species, cattle dominates in Rotbav with forty-four per cent, followed by ovicaprines (26 per cent) and pigs (23 per cent). In the ‘ashmound’, bones of large animals dominate, while small- to medium-sized animals prevail in the settlement (Figure 7). Cattle dominate the ‘ashmound’ assemblage (50 per cent), while ovicaprines are significantly more numerous in the settlement than in the ‘ashmound’ (35 per cent vs 19 per cent). Hunting is not important. There are only twenty fragments (0.9 per cent) of wild animals in the ‘ashmound’ and twelve (0.7 per cent) in the settlement.

Figure 7. Distribution of small and large mammals in the ‘ashmound’ and settlement at Rotbav (diagram: percentages; NISP after Vigne, Reference Vigne1988).

Further interesting differences between the domestic spaces and the ‘ashmound’ are obvious in the presence/absence of body parts and in the age distribution of the animals. For cattle, there is a slight emphasis on the meat-rich parts (appendicular and axial skeleton, together 52 per cent). By contrast, body parts that are less rich in meat predominate in the settlement: sixty-six per cent of the bones found there belong to the head and extremities (Figure 8, left).

Figure 8. Distribution of body parts of animals in the ‘ashmound’ and settlement at Rotbav (diagram: percentages; NISP after Vigne, Reference Vigne1988).

Thus, the ‘ashmound’ is obviously connected to the consumption of large amounts of meat, although the statistics could be biased to some degree by post-depositional processes that favour the conservation of larger bones. A probable explanation for the differences between settlement and mound would be the transport of the meat-rich body parts (‘missing’ from the settlement) to the ‘ashmound’ and their use for communal feasting.

There is a slight difference among the pigs regarding their age distribution. The ‘ashmound’ holds the remains of older animals (between 18 and 24 months), while younger animals (between 6 and 18 months) predominate in the domestic area (Figure 9). This difference could again be explained by the larger amounts of meat delivered by older animals, while, in the settlement, the emphasis would have been on economical meat production with earlier slaughtering. Another may lie in a cyclical pattern of events connected to the ‘ashmound’, for example reiterated and regular feasting when pigs of a certain size were available. Body parts are distributed fairly evenly between the settlement and the ‘ashmound’ (Figure 8, right).

Figure 9. Distribution of pig age classes in the ‘ashmound’ and settlement at Rotbav (diagram: percentages).

Ovicaprines also display a conspicuous pattern regarding their age distribution. In the ‘ashmound’, the distribution pattern shows two peaks: one between 0.5 and 1 year, the other between 2 and 4 years. In the domestic area, the distribution pattern is irregular; all age classes being present, with a certain dominance of younger animals, most probably slaughtered for meat. The slight emphasis on older and larger animals in the mound could again hint at an effort to meet a greater demand for meat for certain events. Thus, the distribution patterns of skeletal parts for pigs and ovicaprines (Figure 8, middle and right) are most likely to indicate culinary preferences for certain parts of those animals, in everyday life as well as on special events.

To sum up, archaeozoological analysis clearly shows that the ‘ashmound’ is a highly structured deposit as visible in the intentional and strict selection of the animal parts brought there. It was not formed by chance or as a general refuse heap, and it conforms to several indicators for the leftovers of feasting. The feature contains an immense quantity of bones, mainly from larger animals and/or the parts richest in meat, best suited for large communal events.

If we go beyond the nutritional aspect, Twiss (Reference Twiss2008) further extracted from the ethnographical record performances (singing, dancing, music, oratory), coupled with special costume elements as indicators of festive performances. Both aspects are often difficult to grasp in archaeological contexts. The ‘ashmound’ of Rotbav, however, holds some clues.

As mentioned, the only larger group of objects found in the mound that are not immediately related to food production are crenated scapulae (Figure 4), fashioned from the bones of cattle and pig. They were used as scrapers in hide-working (Dietrich, Reference Dietrich2014: 135–37, with bibliography). In combination with the chemical evidence for lime, the chaîne opératoire can be reconstructed fairly well and corresponds to traditional methods for removing hair from hides. The skins were either put into limewash (Ca(OH)2), or a lime paste was applied to the flesh side of the hides. The paste then permeates the skin and loosens the hair (Mauch, Reference Mauch2004: 26, 65–66).

The mound would, thus, not only hold the remains of feasts, but also perhaps of the large-scale preparation of costume elements. In the domestic areas immediately adjacent to the ‘ashmound’, a high density of bone sewing needles was recorded during excavation. In the rest of the site, needles and crenated scapulae are rare (Dietrich, Reference Dietrich2014: 198, fig. VII.20). Why the needles were not also deposited after use in the mound remains unclear. Feasting would be related to the work-intensive event of slaughtering, butchering, and working the hides of a large number of animals.

A last step in feasting, and a last possible indicator for it in the archaeological record is—according to Twiss (Reference Twiss2008)—the production or display of commemorative items. This is especially difficult to assess, as the commemorative value of an item is highly subjective and susceptible to false modern perceptions. So, although there are indeed some conspicuous elements in the ‘ashmound’ at Rotbav and in some other mounds, their interpretation remains hypothetical. The construction and formation of the mound seem to have been a highly controlled process, starting with the construction of a basin and involving possibly several filling events. These events cannot (yet) be pinpointed more exactly due to the uniformity of the infill and the small number of radiocarbon dates so far available. Nonetheless, a final act in this process can be described in more detail. A small bronze hoard consisting of a ‘Cypriote’ pin and a bronze bar, perhaps the basic form for a bracelet (O. Dietrich, Reference Dietrich, Dietrich, Dietrich, Heeb and Szentmiklosi2009) was discovered immediately under the mound's surface. This hoard could have had a commemorative value; in any case, it can be seen as a closing deposit. Hoards of sewing needles or awls are known from several ‘ashmounds’, and there is also evidence for the careful arrangement of animal skulls (e.g. at Cobâlnea, Sava, Reference Sava, Hänsel and Machnik1998: 273, fig. 2).

Deciphering Feasting

In summary, many of the arguments presented for the recognition of feasting by Twiss (Reference Twiss2008) are recognizable in the ‘ashmound’ at Rotbav. It is hard to say, however, whether the mound area was part of the feasting activities or just the site for depositing the resulting debris. It is reasonably clear that the mound is not the settlement itself, as proposed in recent studies (Sava & Kaiser, Reference Sava and Kaiser2011), but instead a structure intentionally constructed at the periphery of the settled area. A large basin was carefully dug, filled with large quantities of pottery and animal bones (that are structurally distinct from the domestic area), and lastly sealed by a hoard and then left. Two radiocarbon dates (Hd-27972: 3085 ± 23 bp or 1415–1282 cal bc at 95.4 per cent confidence, and Hd-28276: 3196 ± 30 bp or 1518–1415 cal bc at 95.4 per cent confidence) suggest a quite long period of use of the mound, but this is open to further study. The dense packing of finds in a hard sediment hints at the simultaneous deposition of large quantities of objects, even though the exact formation of the lime-rich sediment still awaits pedological explanation. Currently, a slower formation of the deposits through accumulation of food refuse remains a possibility.

The distribution pattern allows us to suggest that a large number of suitable animals were selected and slaughtered in the settlement, then prepared, the hides worked, and the remains deposited in the ‘ashmound’. Strict rules seem to have governed the process, and also the treatment of the tools used and the refuse. The hypothesis of a fast deposition is supported by the differing degree of fragmentation of items in the mound and in the settlement (for the following, see the detailed discussion in Dietrich, Reference Dietrich, Sosna and Brunclíková2016). Regardless of the species or body parts concerned, animal bones in the ‘ashmound’ are larger and less fragmented (Figure 10). Clearly, they were not subjected to the same post-depositional processes as material in the settlement (trampling, etc.). Pottery fragments are more equal in size in the mound than in the domestic spaces. This might indicate an intentional fragmentation of pottery in the ‘ashmound’, or it was again due to different post-depositional processes. The spatial analysis and the fragmentation indexes of pottery from the settlement show that ‘normal’ domestic waste was continuously deposited between the houses, where it underwent diverse processes of degradation, resulting in a large variation in fragment sizes.

Figure 10. Notched boxplot with lengths and weights of animal bones in the ‘ashmound’ (1), NSC-early settlement (2), and NSC early and late settlement (3) at Rotbav (produced using the ‘Free Statistics Software’ provided by Wessa, Reference Wessa2014).

The starting point of this contribution was M. Douglas’ assumption of a rational relationship between food selection and social order (Douglas, Reference Douglas2002), mirrored in the case of Late Bronze Age Rotbav in the phenomenon of feasting, which theoretically can be traced in the archaeological record (Twiss, Reference Twiss2012).

But, even if one accepts this assumption, the selection of feasting foods does not provide a comprehensive image of the social structure or cosmology of the NSC and in particular as expressed in the settlement of Rotbav. Yet the structuring observed in the archaeological contexts at Rotbav and the discrepancies between the settlement and the ‘ashmound’ most probably reflect a set of social rules governing the life of (the larger part?) of its inhabitants and their foodways; with rules governing collective rather than individual aspects. The impression of a collective activity can also be perceived in other aspects of the NSC's archaeological record. The settlements are apparently uniformly structured (Florescu, Reference Florescu1964, 146–50; Dietrich, Reference Dietrich2014: 286–96, with further bibliography), even if that does not imply that hierarchies are missing altogether. The same holds true for the cultural landscape, with a regular spread of settlements apparently without central places (Dietrich, Reference Dietrich2014: 286–96), and the conspicuous uniformity of graves with a lack of complexes containing abundant grave goods (Sava, Reference Sava2002).

Collective feasting—perhaps ‘work feasts’ (Hayden, Reference Hayden, Dietler and Hayden2010: 29–30) connected to hide-working and feasts for promoting social cohesion or community alliance (Hayden, Reference Hayden, Dietler and Hayden2010: 56–57)—is very likely in this context. Cattle predominate not only in Rotbav, but generally in the NSC (Sava, Reference Sava, Horejs, Jung, Kaiser and Teržan2005b; Dietrich, Reference Dietrich2014: 297–301), and seem to have played an important role in the culture's symbolic world, at least judging from abstract representations, such as the clearly zoomorphic knobbed handles of the kantharos vessels (Dietrich, Reference Dietrich2014: 193–94).

On the basis of chemical and archaeozoological analyses of well-excavated sites, we are, thus, beginning to reconstruct a Late Bronze Age society, in which the economic importance of animals was intrinsically entangled with their social and cosmological dimensions, but the picture remains nebulous and further research is needed to bring it into sharper focus.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank M. Daszkiewicz and G. Schneider (Freie Universität Berlin) for undertaking the chemical analysis. Work at Rotbav was financed by the Romanian Ministry of Culture.