Introduction

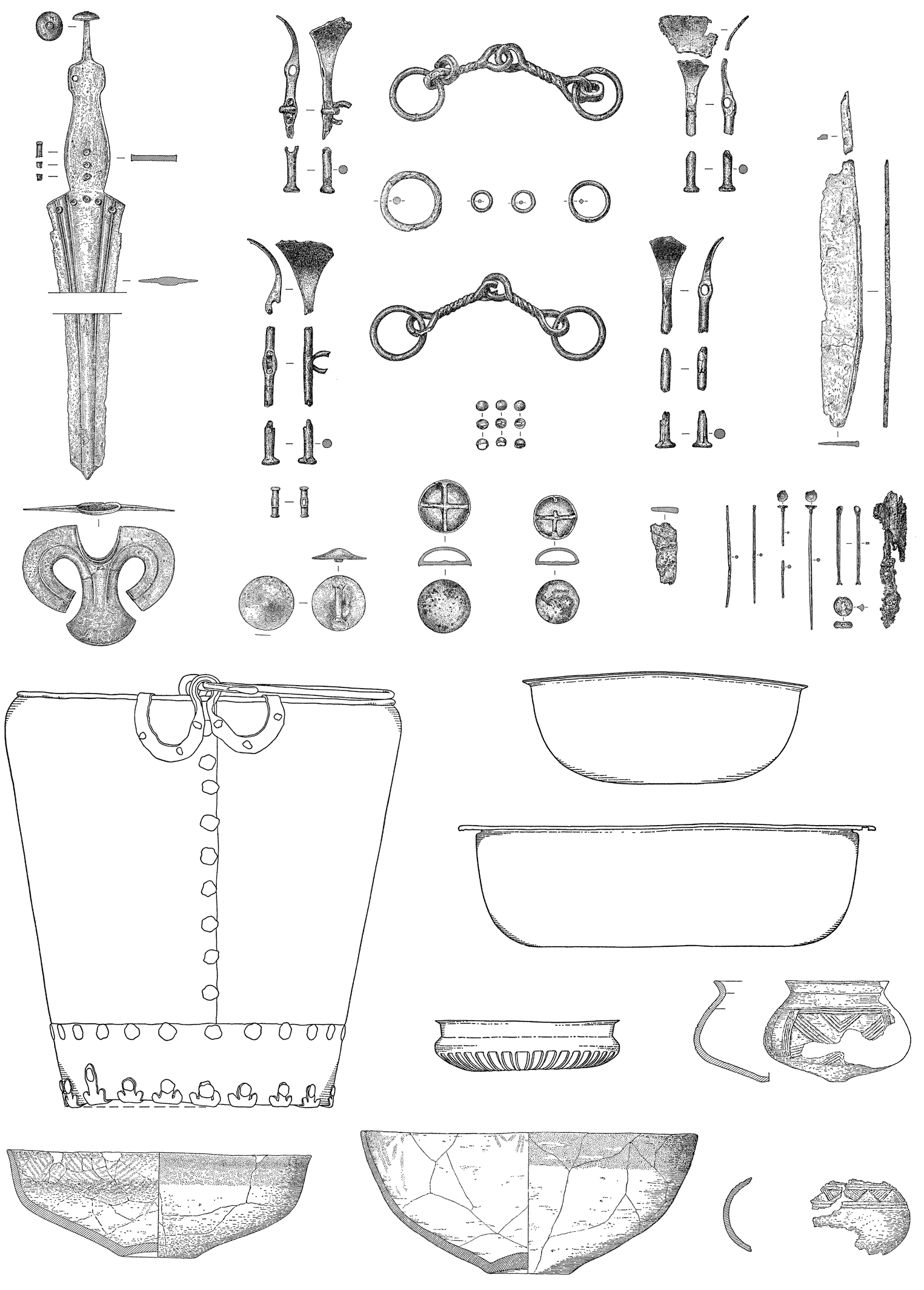

The Early Iron Age (800–500 bc) was a time of rapid development and change characterized by long-distance interaction. It saw the first indisputable rise of elites north of the Alps who interacted across the breadth of Europe (Collis, Reference Collis1984; Kristiansen, Reference Kristiansen1998; Wells, Reference Wells and Milisauskas2011; Huth, Reference Huth, Bräuning, Löhlein and Plouin2012). These elites are mainly known from their exceptional burials containing weaponry, bronze vessels, and horse-drawn ceremonial wagons (e.g. Frankfurt-Stadtwald, Figure 1). These objects played a role in the construction and expression of a complex identity (Pare, Reference Pare1992; Huth, Reference Huth2003b). Such burials are primarily found in the Central European Hallstatt culture. Interments with the same grave goods also occur in surrounding areas, like the Low Countries considered in this article, and it has long been recognized that they reflect long-distance interaction (Figure 2)(Holwerda, Reference Holwerda1934; Kossack, Reference Kossack, Kossack and Ulbert1974; Pare, Reference Pare1992; Krauße, Reference Krauße, von Carnap-Bornheim, Krauße and Wesse2006; Wells, Reference Wells and Milisauskas2011; Milcent, Reference Milcent2012).

Figure 1. Grave goods from Frankfurt-Stadtwald (after Fischer, Reference Fischer1979). Reproduced by permission of the Archäologisches Museum Frankfurt.

Figure 2. Sites discussed in this article. 1 Ede-Bennekom; 2 Rhenen-Koerheuvel; 3 Oss-Vorstengraf; 4 Oss-Zevenbergen; 5 Wijchen; 6 Haps; 7 Horst-Hegelsom; 8 Neerharen-Rekem; 9 Limal-Morimoine; 10 Court-St-Etienne; 11 Kemmelberg; 12 Frankfurt-Sandhof; 13 Frankfurt-Stadtwald; 14 Nidderau; 15 Glauberg; 16 Großeibstadt; 17 Hochdorf; 18 Aislingen; 19 Wehringen; 20 Riedenburg-Untereggersberg; 21 Riedenburg-Emmerthal; 22 Otzing; 23 Gilgenberg-Gansfuß; 24 Mitterkirchen; 25 Hallstatt (map: Lukas Eckert; background: maps-for-free.com).

In the past, studies of Hallstatt culture elite burials focused primarily on the object types interred. Many of the Hallstatt culture's defining attributes, however, show different regional and supra-regional distributions. Therefore, looking at different attributes leads to different assessments of what can be referred to as ‘Hallstatt culture’ (see Karl, Reference Karl, Koch and Cunliffe2010: fig. 2.4). If one focuses on sword distribution, for example, the Low Countries would be a part of a widely defined ‘Hallstatt culture’ extending to the British Isles, while all other definitions exclude the Dutch and Belgian burials (Karl, Reference Karl, Koch and Cunliffe2010). This is reflected in how the ‘Hallstatt culture’ and its geographic distribution are defined (see Müller-Scheeßel, Reference Müller-Scheeßel2000) and shows the dangers of a purely object-based approach, especially as all objects discussed here are only characteristic of the western part of the Hallstatt culture area (see Rebay-Salisbury, Reference Rebay-Salisbury2016 for a recent discussion on distinguishing different groups in Early Iron Age Central Europe). If one considers the presence of single objects only (i.e. those found in the elite burials), then the Low Countries would be viewed as part of the Hallstatt culture, even though settlement patterns, material culture, and burial practices mostly differ. Indeed, the Belgian Kemmelberg is the only settlement to potentially show contacts with Early Iron Age Central Europe (see Fernández-Götz & Ralston, Reference Fernández-Götz and Ralston2017 for a recent overview), but as it post-dates the elite burials discussed here it is not discussed further.

Explanations for burials with Hallstatt culture imports have traditionally focused on trying to find the exports that so-called peripheral areas, like the Low Countries, could have had to offer in trade for exotic bronze vessels, weaponry, and wagons (Frankenstein & Rowlands, Reference Frankenstein and Rowlands1978; Roymans, Reference Roymans, Roymans and Theuws1991; Pare, Reference Pare1992). Here, we take a different approach to exploring the contacts reflected in the Early Iron Age elite burials. We examine the connections reflected in the elite burials of the Central European Hallstatt culture and a geographically distinct concentration of elite graves with Hallstatt culture imports in the Low Countries. By looking beyond the objects interred and comparing the funerary practices through which elite burials in both regions were formed, we hope to show that a practice-based approach to these complexes—rather than a focus purely on the types of objects they contain—leads to a far better understanding of the contacts reflected in them.

We consider not only which objects attributed to the Hallstatt culture ended up in the Low Countries, but also how they were used, treated, and deposited in elite burials, and how this compares with their use and treatment in their area of origin. Working from such a perspective can provide new insights into the agency of things and how material culture was used, appropriated, and recontextualized in different groups (see, for example, Hahn, Reference Hahn, Probst and Spittler2004; Stockhammer, Reference Stockhammer and Stockhammer2012; Hahn & Weis, Reference Hahn, Weis, Hahn and Weis2013; see also Fontijn & van der Vaart-Verschoof, Reference Fontijn, van der Vaart-Verschoof and Hodos2016; Bourgeois & van der Vaart-Verschoof, Reference Bourgeois, van der Vaart-Verschoof, Schumann and van der Vaart-Verschoof2017).

In the following, we first discuss the funerary practices of the Low Countries and how the elite burials are embedded in this regional behaviour. We then consider a number of elements thought characteristic of the Low Countries’ elite funerary rite, which we argue also feature in the Central European Hallstatt culture. These burials therefore indicate more than the mere exchange of objects, and it is imperative that we start considering them as such if we are to understand the elite burials and long-distance contacts that characterize the Early Iron Age.

Early Iron Age Funerary Practices in the Low Countries

In the Low Countries, the elite funerary cremation rite was practised alongside burial in urnfields, which continued in this region well into the Early Iron Age. For a time, both burial customs were practised side by side in the same communities and we discuss them both. We stress, however, that while we of necessity make a distinction between the two here, there was a burial spectrum that ran from the very richest elite burial to the ‘simplest’ urnfield grave (van der Vaart-Verschoof, Reference van der Vaart-Verschoof2017a).

The ‘normal’ way of burying: urnfields

The practice of burying in urnfields was dominant in the Low Countries during the Early Iron Age (e.g. Kooi, Reference Kooi1979; De Laet, Reference De Laet1982; De Mulder, Reference De Mulder2011). This was a diverse burial practice characterized by the cremation rite, and the resulting graves are frequently described as ‘simple’ and ‘modest’ (De Mulder & Bourgeois, Reference De Mulder, Bourgeois, Moore and Armada2011: 303). Men, women, and children are all represented in urnfields, and most were interred in individual graves. These were frequently covered with a small mound, leading over time to the development of (some very large) urnfields. They are also found as flat graves, long barrows, or enclosed by ring-ditches (e.g. Kooi, Reference Kooi1979; De Laet, Reference De Laet1982; Lohof, Reference Lohof1994; Verlinde & Hulst, Reference Verlinde and Hulst2010; De Mulder, Reference De Mulder2011).

Grave goods are generally limited to ceramics (usually a single pot or cup), and metal objects are rare, although there are exceptions. Relatively common finds are small personal items like pins, ornaments, razors, and tweezers, which were frequently fragmented and only partially deposited (e.g. De Laet, Reference De Laet1982; Temmerman, Reference Temmerman2007; Verlinde & Hulst, Reference Verlinde and Hulst2010; De Mulder, Reference De Mulder2011). They are widely accepted to be intentional pars pro toto depositions, and it is likely that it was the ‘representative character of the collected remains that counted’ (Fontijn, Reference Fontijn2002: 204). The urnfields are generally interpreted as collective cemeteries that provided a strong sense of community to the local society (Roymans & Kortlang, Reference Roymans, Kortlang, Theuws and Roymans1999: 36; De Mulder & Bourgeois, Reference De Mulder, Bourgeois, Moore and Armada2011: 303–04).

The elite burials of the Low Countries

At the same time, a very small minority of the population was interred in so-called chieftains’ graves, which primarily date to the eighth and seventh centuries bc. While cremations, these graves yield the same bronze drinking vessels, weaponry, decorated horse-gear and wagon components, tools, toiletries, and personal ornaments as those of the Hallstatt culture (Figure 3). The burials are relatively diverse, ranging from graves with pottery and only a sword or a bronze vessel (e.g. Horst-Hegelsom or Ede-Bennekom) to elaborate burials with a complete ‘set’ like the Chieftain's grave of Oss, which yielded a bronze vessel, a rolled-up Mindelheim sword with gold-inlaid hilt, yoke components, a pair of bridles, tools, pins, and razors (Figure 2). Sometimes there is only one elite burial at a given site, while at others they are clustered together. Almost all are in or near urnfields and/or barrow groups, and they are frequently found at higher points in the landscape. Some sites represent short bursts of activity, while others were used for longer periods. Many grave goods show signs of use, while others are unusable and appear to be purely symbolic (van der Vaart-Verschoof, Reference van der Vaart-Verschoof2017a, Reference van der Vaart-Verschoof2017b).

Figure 3. Artefacts from (a) the Horst-Hegelsom burial: pottery vessels and folded sword (Limburgs Museum, Venlo: L27171.1-3; photograph ©S. van der Vaart-Verschoof); (b) the Ede-Bennekom burial: bronze situla (Rijksmuseum van Oudheden, Leiden: HW 24); and (c) the assemblage from the Chieftain's burial of Oss (Rijksmuseum van Oudheden, Leiden: k 1933/7.1-20). b and c ©Rijksmuseum van Oudheden, Leiden, reproduced with permission.

In many ways, the elite burials were strongly embedded in the locally dominant urnfield funerary practice. This included the rite of cremation and similar burial locations, the elite burials often being found in or near urnfields. The elite funerary practice, however, was far more destructive. Not only were the decedents burned, but grave goods were frequently also placed on the pyre as well. Furthermore, the objects were frequently bent and broken, ranging from rolling up a sword to repeatedly folding elements of wagon decorations. The melted and/or fragmented grave goods were often interred through pars pro toto depositions, something that was also done with human remains (see below). As a key element of the funerary rite, it is argued that the fragmentation of objects and the partial deposition of both objects and human remains were powerful symbolic acts (Chapman, Reference Chapman2000; Brück, Reference Brück2004: 319–21) related to the processing of (relational) identities and contacts in death (e.g. Rebay-Salisbury et al., Reference Rebay-Salisbury, Rebay-Salisbury, Sørensen and Hughes2010; Brück & Fontijn, Reference Brück, Fontijn, Fokkens and Harding2012; see also van der Vaart-Verschoof, Reference van der Vaart-Verschoof2017a: 149–50 for a broader discussion).

The individuals buried with wagons and wagon-related horse-gear in particular were interred through exaggerated, destructive, and ostentatious funerals. In some cases, especially those with wagons and related horse-gear, textiles were used to wrap grave goods or cremated remains. Relatively large barrows frequently marked these graves, and sometimes it appears that mourners intentionally connected the elite graves with ‘ancestral’ burials by reusing ancient mounds. They are also defined by the absence of the horses that pulled the wagons, which appear never to have been interred (see below; van der Vaart-Verschoof, Reference van der Vaart-Verschoof2017b).

In short, the elite burials of the Low Countries in many ways reflect the ‘normal’ way of burying (van der Vaart-Verschoof, Reference van der Vaart-Verschoof2017a). However, the exceptional richness and nature of the grave goods also set them apart from contemporary graves, as do several aspects of the burial practice noted above. It is in these that we argue intensive long-distance contact and interaction (which went beyond the exchange of objects) is reflected.

Elite Burial Practices from an Interregional Perspective

The elite burials of the Low Countries represent tangible evidence of (likely direct) long-distance interaction during the Hallstatt C/D period between this part of north-western Europe and the Hallstatt culture of Central Europe. However, they are almost never studied in this capacity. They may appear as isolated dots on distribution maps (e.g. Pare, Reference Pare1992: figs 4, 10a–d), but the objects are (implicitly) seen as single objects imported from distant regions. Exactly how these objects and the burials in which they are found relate to the Central European Hallstatt culture or their role in large-scale interactions and social differentiation in Early Iron Age Europe is seldom considered. We argue that this hinders our understanding of these exceptional, connected complexes.

In the following, we discuss several defining features of the Low Countries’ elite burial practice and examples from Hallstatt culture burials that, in our opinion, show that elite burials were regionally embedded and interdependent on a large scale and, by extension, connected the elites living in these regions.

Bending and breaking

As noted, one of the main aspects of the Low Countries’ elite burial practice is its destructive nature and the transformation of both grave goods and the deceased. For the former, several practices of transformation and destruction can be observed. Grave goods were bent and folded (e.g. the Oss sword, Figure 7 or the Rhenen tweezers, Figure 4e), but also broken into pieces (e.g. the pendant from Wijchen, Figure 4a, or the horse-bit from Limal-Morimoine Tombelle 1, Figure 4d) to make them unusable (and sometimes to fit into urns). Although the degree and manner of destruction may vary, this transformation is a key element of the Low Countries’ funerary practice, especially in the elite burials (van der Vaart-Verschoof, Reference van der Vaart-Verschoof2017a: 143–61).

Figure 4. Burnt, folded, and fragmented grave goods from Low Countries elite burials, including (a & c) wagon decorations (Museum het Valkhof, Nijmegen); (b) a belt plate from Wijchen (Museum het Valkhof, Nijmegen); (d) a horse-bit fragment from Limal-Morimoine Tombelle 1 (Musées royaux d'Art et Histoire, Bruxelles); and (e) tweezers from Rhenen-Koerheuvel (Museum het Rondeel, Rhenen). Photographs a, b, c, & e by J. van Donkersgoed, ©S. van der Vaart-Verschoof; d after Mariën, Reference Mariën1958: fig. 40, reproduced with permission of Musées royaux d'Art et Histoire, Bruxelles.

Even though deliberate destruction, bending, and the transformation of grave goods are not considered defining elements of the Central European Early Hallstatt period sumptuous burials, recent detailed consideration of these graves has revealed similarities (see also Augstein, Reference Augstein, Schumann and van der Vaart-Verschoof2017). Indeed, the deliberate destruction of grave goods can be observed in many such graves. Trachsel (Reference Trachsel, Karl and Leskovar2005), for example, established that over half the swords known from Hallstatt culture burials were intentionally damaged or destroyed prior to interment (see also Gerdsen, Reference Gerdsen1986). Nevertheless, generally the destruction is less obvious, such as the scabbard chape from Frankfurt-Stadtwald, which seems to have been broken deliberately (Fischer, Reference Fischer1979; Willms, Reference Willms2002). Given the nature of old excavations, it is likely that similar cases of broken objects have gone unrecognized. Even so, the number of fragmented swords clearly indicates that fragmentation was part of elite burial rituals in the Hallstatt culture. Wagons similarly appear to have frequently been buried in a non-functional state (e.g. Wehringen: Pare, Reference Pare1991; Hennig, Reference Hennig2001; or Großeibstadt: Kossack, Reference Kossack1970: 48–49).

In short, it appears that some form of transformation, including the deliberate destruction of grave goods during funerary rituals, featured both in the elite burials of Low Countries and in those of the Central European Hallstatt culture. While the degree of destruction may differ, we argue that there are unrecognized and perhaps underappreciated similarities between them, fragmentation being but one manifestation.

Pars pro toto

As discussed, the custom of pars pro toto deposition, both of grave goods and human remains, forms a defining feature of the Low Countries’ burial practices. Oss, where three monumental Hallstatt C barrows yielded three elite burials showing varying degrees of fragmentation and pars pro toto depositions, is a striking example. The Chieftain's grave of Oss (known as Oss-Vorstengraf) is one of the most complete prehistoric cremation deposits found in the Low Countries, with all skeletal elements (except his teeth) represented (Fokkens et al., Reference Fokkens, van der Vaart-Verschoof, Fontijn, Lemmers, Jansen, Van Wijk, Bakels and Kamermans2012: 212; Lemmers, pers. comm.). The ‘Chieftain's’ remains were buried in a bronze vessel along with a rolled-up Mindelheim sword with gold-inlaid hilt, yoke components, two bridles, tools, dress pins, and razors. While the wagon was dismantled and only elements of the yoke were deposited, none of his grave goods were fragmented (van der Vaart-Verschoof, Reference van der Vaart-Verschoof2017b: 176–98). Mound 7, another monumental barrow less than 500 m away at Oss-Zevenbergen, yielded the cremated remains of a man and a yoke, as well as his burnt-out pyre. Here, however, the man's cremated remains were only partially deposited, and a significant portion was removed from the burial deposit. The fragmented remains of a yoke were left among his burnt-out pyre, with bronze rings deliberately broken and partly removed from the burial context (Fontijn et al., Reference Fontijn, Jansen and van der Vaart-Verschoof2013). It seems that both a selection of the man's remains and his belongings were interred, and selected elements removed as part of the funerary ritual. The most extreme example of the pars pro toto practice comes from Oss-Zevenbergen Mound 3, where only one piece of cremated human bone and small fragments of four objects lay carefully arranged around a burnt plank from a massive and ancient oak (Fokkens et al., Reference Fokkens, Jansen and van Wijk2009).

The burials at Oss demonstrate that both human remains and grave goods were not only fragmented, but partially deposited, suggesting that they were also likely to have been partially retained by the mourners. These graves form but one example of the pars pro toto practice that defines the Low Countries’ burials, particularly for wagons (van der Vaart-Verschoof, Reference van der Vaart-Verschoof2017a). Dutch and Belgian sumptuous graves regularly yield only a few wagon components that hint at the idea of a wagon-grave (see Pare, Reference Pare1992). Even at Wijchen, which yielded the most ‘complete’ wagon in the Low Countries (Figure 5), there are no traces of the wheels. In some cases, the idea of a wagon-grave is indicated by two pieces of horse-gear, as at Court-St-Etienne Tombelle 3. Again, Oss-Zevenbergen Mound 7 is an extreme case where only some bronze yoke decorations (studs and (broken) rings) indicate a wagon-grave (Fontijn et al., Reference Fontijn, Jansen and van der Vaart-Verschoof2013).

Figure 5. Assemblages from (a) Wijchen (Museum het Valkhof, Nijmegen); and (b) Court-St-Etienne Tombelle 3 (Musées royaux d'Art et Histoire, Bruxelles: B1683). Photograph by J. van Donkersgoed, ©S. van der Vaart-Verschoof.

Pars pro toto depositions of grave goods can also be identified in the Hallstatt culture, especially in wagon-graves. As Pare (Reference Pare1992) notes, numerous burials that might be taken to be wagon-graves are only indicated by paired horse-gear, for example Großeibstadt in Bavaria (Kossack, Reference Kossack1970), Hradenín in Czechia (Dvořák, Reference Dvořák1938), or Gilgenberg-Gansfuß in Austria (Stöllner, Reference Stöllner and Dobiat1994). The number of such burials, in contrast to actual wagon-graves, increases over the course of the Hallstatt period (Pare, Reference Pare1992). While we must take into account that Early Iron Age wagons could have been constructed entirely of wood, it is relatively widely accepted that such graves, in particular those with paired horse-gear, represent pars pro toto depositions of wagons and a form of wagon burial. Furthermore, Pare (Reference Pare1992) already noted that some types of wagons were often deposited without their wheels. In some cases, a wagon-box, yoke, and horse-gear are present, but no trace of the wheels, as seems to be the case in the recently excavated Otzing burial in Bavaria (Claßen et al., Reference Claßen, Gussmann, von Looz, Husty and Schmotz2013). Although interpretation of the wooden elements as a wagon-box is still being debated (Gebhard et al., Reference Gebhard, Metzner-Nebelsick and Schumann2015), the yoke and the paired horse-gear clearly evoke a wagon-grave.

Other examples take this pars pro toto practice further, for example in Grave X/1 of the Mitterkirchen cemetery in Upper Austria (Leskovar, Reference Leskovar1998), the earliest sumptuous burial of a woman known in the Hallstatt culture (Metzner-Nebelsick, Reference Metzner-Nebelsick, Bagley, Eggl, Neumann and Schefzik2009). Here the wagon-box and yoke placed in front of it clearly suggest a wagon-grave, even though no traces of wheels or horse-gear were found (Figure 6). Another example that documents the variability of wagon deposition is the burial of Frankfurt-Stadtwald. Here a yoke and richly decorated horse-gear were found, but no trace of a wagon (Fischer, Reference Fischer1979; Willms, Reference Willms2002).

Figure 6. Plan of burial X/1 of Mitterkirchen; note the lack of wheels (after Schumann et al., Reference Schumann, Leskovar, Marschler, Nikulka, Hofmann and Schumann2018: fig. 2). ©Oberösterreichisches Landesmuseum, reproduced with permission.

Considering that the wagon, yoke, and horse-gear components found to be ‘missing’ in such cases generally incorporate metal elements, their absence should be interpreted as intentional pars pro toto wagon depositions, rather than as the result of differential survival. Without going into further detail on the different aspects of the pars pro toto custom, it appears that wagon-graves show similarities in the treatment of grave goods between the Low Countries and the Hallstatt culture. As with fragmentation, the pars pro toto custom seems to be an important aspect of Hallstatt sumptuous burial practice in both the Low Countries and Central Europe.

Wrapping in cloth

The use of textiles as a functional part of the burial practice has been established as one of the defining features of the very richest elite burials of the Low Countries and, intriguingly, is strongly associated with graves argued to show the clearest Hallstatt culture influences. Found primarily in burials with wagons and wagon-related horse-gear, high-quality textiles were used both to wrap objects and interred as precious grave goods in their own right (van der Vaart-Verschoof, Reference van der Vaart-Verschoof2017a, Reference van der Vaart-Verschoof2017b). We must, however, acknowledge that wrapping in textiles generally can only be observed in burials with large quantities of metal grave goods, as textiles usually do not survive in graves if not directly in contact with metal objects (see Grömer, Reference Grömer2016 for exceptions). The best-preserved, and best-known, example is the Chieftain's grave of Oss (Figure 7). Here, exceptional preservation allowed for the identification of six different kinds of textile used to wrap grave goods, as well as another two types of cloth that are likely to have been imported from Central Europe and formed grave goods in their own right (Grömer, pers. comm.; van der Vaart-Verschoof, Reference van der Vaart-Verschoof2017b: 188–98). Textiles were also observed on several other swords and in a bronze bucket from Rhenen-Koerheuvel (van der Vaart-Verschoof, Reference van der Vaart-Verschoof2017b: 215). Poor excavation circumstances generally do not allow us to identify how the textiles were used, but it is believed that in most cases they were used to wrap grave goods as part of the burial rituals.

Figure 7. The Oss sword with details of the textile wrapping on the wooden grip and iron blade. ©Rijksmuseum van Oudheden, Leiden, reproduced with permission.

The use of textiles in funerary rituals in the Hallstatt culture has been well-known since at least the excavation of the well-preserved later Hallstatt burial at Hochdorf in Baden-Württemberg made this practice famous. Some served as a wrapping for grave goods, which appear to have been completely covered in textile at the time of burial (Banck-Burgess, Reference Banck-Burgess1998). This custom is also documented in the Early La Tène period, for example at Glauberg (Hesse) where the same custom has been recognized, especially as attested by the wrapped Schnabelkanne (Bartel et al., Reference Bartel, Bodis, Bosinski, Flügen, Frölich, Geilenkeuser and Piker2002; Balzer et al., Reference Balzer, Peek and Vanden Berghe2014). While evidence for this practice during the Early Hallstatt period is scarcer due to a dearth of research, it can be identified in several cases, especially in the treatment of swords. While preserved textiles on swords could be part of a scabbard or of a simple cover, there are numerous well-preserved cases where acts of wrapping could be recognized, especially in more recently excavated burials. Two Early Iron Age burials excavated at Nidderau in Hesse (Ney, Reference Ney, Schumann and van der Vaart-Verschoof2017), for example, yielded swords wrapped in textile (Figure 8). Re-examination of older excavated swords can also reveal wrapping practices, as at Frankfurt-Sandhof where up to three layers of textile, among other organic remains, were identified on a sword originally excavated and restored in the 1960s (Martins & Willms, Reference Martin and Willms2005). The regular occurrence of this custom is clearly attested by further examples. In Riedenburg-Untereggersberg (Bavaria), a broken sword was found in a grave for which Nikulka (Reference Nikulka1998) has discussed different interpretations of the preserved textiles, among them wrapping, while a sword wrapped in textile and broken into several pieces was recovered from a grave at Mitterkirchen in Upper Austria (Leskovar, Reference Leskovar1998). These examples show how fragmentation and wrapping in textiles are combined for some Hallstatt culture finds, as they are in the Low Countries.

Figure 8. The iron sword of Nidderau grave 2 was wrapped in three layers of textile made of plant fibres (photograph: M. Stotz; after Ney, Reference Ney, Schumann and van der Vaart-Verschoof2017: fig. 4). Reproduced with permission of Wolfram Ney.

In short, the swords evidence the longue durée of this burial custom which is so well-known from the Hallstatt D and Early La Tène period, but was already practised in Hallstatt C. The practice of wrapping grave goods during the burial of exceptional individuals appears to further show the connections that existed between the Low Countries and the Central European Hallstatt culture and connects the Early Hallstatt burials discussed in this article with later princely graves.

Reuse of ancient burial mounds

In this section we address similarities in the locations selected for elite burials and the monuments erected to mark them. While elite burials are also found in other forms, the marking of such graves with barrows was widespread. It can be observed in several prehistoric periods and regions throughout Europe. Here, we concentrate on the apparent desire not only to mark elite burials with barrows, but to also connect them with older graves that may have been perceived as ancestral burials.

As noted above, the elite burials of the Low Countries are frequently covered with barrows, many of them exceptionally large, the ‘Chieftain’ of Oss's burial mound being the largest in the Netherlands with a diameter of 53 m (Fokkens & Jansen, Reference Fokkens and Jansen2004: 133–35). Its size and the burial it contained, however, are not its only interesting aspects. The Chieftain was buried in a pit, deliberately positioned off-centre and dug clean through an older Middle Bronze Age barrow. The mourners knew they were reusing an ancient burial place—already a thousand years old at the time—and respected the earlier central grave when they dug their new burial pit. After placing the Chieftain's urn with its grave goods inside, the pit was covered with a new, massive mound. This desire to connect with ancestral burials may also have motivated the choice of burial location at Oss-Zevenbergen Mound 7 (Fontijn et al., Reference Fontijn, Jansen and van der Vaart-Verschoof2013: 293). Moreover, the elite burials of the Low Countries were frequently enacted in existing burial grounds, in some cases re-activating cemeteries that had been unused for funerary activities for hundreds of years.

In contrast to the earlier Urnfield period, the practice of erecting barrows forms an integral part of burial customs of the Hallstatt culture and is regularly discussed in the context of the definition and the start of the Hallstatt culture (e.g. Pare, Reference Pare, Bourgeois, Bourgeois and Cherretté2003). Yet, as excavations of the last decades show, small urn-graves located between burial mounds appear to remain a central aspect of the Hallstatt funerary ritual, indicating an element of continuity from the Urnfield period. In large parts of the Hallstatt culture area, old, primarily Middle Bronze Age, burial mounds were reused during the Early Iron Age. This practice can be observed on different levels. In some cases, barrows were used for secondary graves during the Early Iron Age (e.g. Riedenburg-Emmerthal in Bavaria; Schanz, Reference Schanz1997). Significantly, though, Bronze Age (and other) barrows were also used as the basis for erecting even larger mounds. The best-known example of this custom is the Frankfurt-Stadtwald burial, discussed above, where three phases of mound building were identified, the earliest dating to the Middle Bronze Age (Fischer, Reference Fischer1979; Willms, Reference Willms2002). In the course of the Early Iron Age elite burial ritual, the mound was hugely enlarged, like that of the Chieftain's burial of Oss.

The reuse of old burial grounds was common in the Hallstatt culture, with at least one fifth of all Early Iron Age cemeteries being based on already existing burial grounds (though in some cases it is unclear if there was a break in use; Müller-Scheeßel, Reference Müller-Scheeßel2013). This custom of reusing old monuments gives interesting insights into the perception of the past in the Early Iron Age (see e.g. Bradley, Reference Bradley2002 on several aspects of this topic) and in the case of the sumptuous burials, this may have taken place in the context of the construction of lineages to legitimize power by constructing a significant past.

Burying horse-gear and wagons, not the horses

There can be no doubt that horses were highly valued in Early Iron Age society, as evidenced not only from the deposition of horse-tack components in burials both in the Low Countries and Hallstatt culture burials, but also the frequent representations of horses on clothing, ornaments, and vessels as well as the miniature wagons, figurines, and cult wagons (e.g. Lucke & Frey, Reference Lucke and Frey1962; Pare, Reference Pare1992: 195–202, fig. 135; Egg, Reference Egg1996; Reichenberger, Reference Reichenberger2000; Metzner-Nebelsick, Reference Metzner-Nebelsick2002: 454–55, 462–68; Koch, Reference Koch2006: 144; Kmeťova, Reference Kmeťova2013b: 68–69).

In the Low Countries, the horses that once pulled the elaborate ceremonial wagons are represented in the elite burials through the interment of their tack rather than their bodies. This varies from the presence of a single metal element to entire bridles, but it is still horse-gear that is interred as a representative of these important animals, not the animals themselves (van der Vaart-Verschoof, Reference van der Vaart-Verschoof2017a, Reference van der Vaart-Verschoof2017b).

While in certain regions of the eastern Alpine Hallstatt culture, horses were sometimes buried with the elite individuals, either completely or in the form of a few (cremated) fragmentary remains (Kmeťova, Reference Kmeťova, Karl and Leskovar2013a, Reference Kmeťova2013b), in the western Hallstatt region almost no horse burials have been found and instead horses are represented through horse-gear components. There are very few exceptions, such as in Aislingen in southern Bavaria (Hennig et al., Reference Hennig, Obermaier, Schweissing, Schuh, Weber, Burger, Bagley, Eggl, Neumann and Schefzik2009).

This brings us to yet another similarity between the elite funerary rites in the Low Countries and those of Central Europe. Clearly wagons and horses were highly valued and symbolically charged, and both in the Low Countries and the western Hallstatt culture mourners appear to have wanted to represent them in graves. In both areas, however, they seem to have done so through the interment of wagon and horse-gear components, rather than through the burial of the horses that pulled the wagons, during elite funerary rites. This selection and composition created in the course of the burial ritual is another similarity, once again showing that more connects the elite burials of the Early Iron Age Low Countries and those of the Hallstatt culture than just use of the same type of grave goods.

Development of the elite funerary rite: weapons as grave goods

Despite the problems associated with the chronology of the Early Hallstatt period, there may also be similarities in the general development of burial rituals and grave goods between the Low Countries and the Central European Hallstatt culture area with respect to the weaponry selected for burial.

Firstly, most Hallstatt culture sword burials do not contain spearheads. Yet there are several very Early Iron Age graves in which the Late Bronze Age tradition of bronze spearhead deposition can be observed, for example in Upper Austria (Schumann, Reference Schumann2015: 131). For the majority of Hallstatt C burials, however, swords were the only weapon interred in graves. However, at the very end of the period, spearheads regularly appear in sword burials in large parts of the Hallstatt culture (see Gerdsen, Reference Gerdsen1986: 54; Stöllner, Reference Stöllner2002: 131–32). Along with the appearance of spearheads towards the end of Hallstatt C, one major change in the burial practices of the western Hallstatt culture concerning weaponry can be observed: during the Hallstatt D period, swords cease to be interred and instead daggers become typical. The early finds are those with antenna-shaped pommels (Sievers, Reference Sievers1982). In some rare assemblages of the Hallstatt culture, these finds occur in the same burials, for example in Hallstatt (Kromer, Reference Kromer1959: pl. 161; Gerdsen, Reference Gerdsen1986: 54) or the recently excavated Nidderau burials (Ney, Reference Ney, Schumann and van der Vaart-Verschoof2017).

Despite the sample of burials from the Low Countries being smaller, making it even harder to investigate how weapon deposition in graves developed, there are once again examples that show similarities. For instance, a weapon grave found at Neerharen-Rekem, dating to the end of the Late Bronze Age (ninth century bc), yielded the cremated remains of three individuals as well as three bronze Gündlingen swords, three bronze spearheads, and two bronze chapes (Temmerman, Reference Temmerman2007). During the Hallstatt C period, swords are the only weapons found in the elite burials, with the exception of Court-St-Etienne Tombelle 3, which contained an early antenna bladed-weapon and an iron spearhead (Mariën, Reference Mariën1958), and the later Haps burial with antenna dagger and small spearheads (Verwers, Reference Verwers1972).

It therefore appears that there are similarities in elite funerary practices between the Low Countries and the Hallstatt culture of Central Europe, in this case in terms of how the association with weapons evolved—from the latest Bronze Age burials with spearheads to classic Hallstatt C assemblages with only swords and the later combination of an antenna weapon with spearheads.

Conclusion: Connected Communities and Shared Actions in Regional Context

Almost a century ago, scholars first recognized that many of the grave goods found in the elite burials of the Low Countries are imports from the Central European Hallstatt culture and hence reflect long-distance connections. As was common at that time, the Dutch and Belgian graves were initially seen as the final resting places of invaders or as the result of large-scale migrations (e.g. Holwerda, Reference Holwerda1934; Mariën, Reference Mariën1952, Reference Mariën1958). Later interpretations focused on identifying the exports that the Low Countries’ inhabitants could have exchanged for the exotic bronze vessels, weaponry, and wagons (e.g. Frankenstein & Rowlands, Reference Frankenstein and Rowlands1978; Roymans, Reference Roymans, Roymans and Theuws1991: 50–54; Pare, Reference Pare1992: 171), and traditionally elite burials in the Low Countries have been perceived as peripheral manifestations (Gerritsen, Reference Gerritsen2003: 10–13; Huth, Reference Huth, Bourgeois, Bourgeois and Cherretté2003a; Fokkens & Jansen, Reference Fokkens and Jansen2004: 84).

However, recent research from a practice-based perspective, involving the detailed examination of all surviving finds and literature, is shedding new light on these important finds. By considering the choices made and actions taken during the funerary rituals rather than focusing on the types of objects deposited, the Low Countries’ elite burials were recognized as being firmly embedded in local funerary practices (van der Vaart-Verschoof, Reference van der Vaart-Verschoof2017a, Reference van der Vaart-Verschoof2017b). At the same time, it was established that, for some elite graves, choices were made during funerary rituals that do not conform to local customs but do appear to make sense from a Hallstatt culture perspective. While it is not claimed that the Low Countries were in some way part of the Hallstatt culture itself, it is argued that individuals familiar with the funerary customs of the Hallstatt cultural sphere must have been involved in these funerary rites. This being the case, the results presented here challenge more than the mere interpretation of the few burials in the Low Countries.

The local understanding in the Low Countries of the significance, symbolism, and use of imported elite gear appears to have run much deeper than previously thought. A preliminary examination suggests that elite graves follow the same conception of burial and way of distinction in both the Low Countries and the Hallstatt culture area. As discussed above, pars pro toto depositions, destruction, wrapping in textile, not burying horses, and the reuse of ancient barrows were practised in both regions, and reveal close ties between the burying communities in these two distinct regions, extending beyond the use and interment of the same types of grave goods. The shared idea behind the lavish graves also indicate that members of societies in the Low Countries and southern Central Europe may have had connected identities and seen themselves in a similar or at least related way. Different social groups throughout Europe were integrated in this specific elite burial practice, the performance of which simultaneously indicated regional and international identities. This phenomenon has recently been interpreted as a potential outcome of a pre-modern globalization in Europe (Fontijn & van der Vaart-Verschoof, Reference Fontijn, van der Vaart-Verschoof and Hodos2016; van der Vaart-Verschoof & Schumann, Reference van der Vaart-Verschoof, Schumann, Schumann and van der Vaart-Verschoof2017), though it could also be interpreted as a form of glocalization or creolization as the mixture of local and global elements in the burial practices in the Low Countries was enacted on different scales of regional and interregional interactions (Stockhammer, Reference Stockhammer and Stockhammer2012; Roudometof, Reference Roudometof2016). The objects and practices observed here, therefore, offer different modes of interpretation dependent on the perspective taken and on the different parts of the practices emphasized.

While this certainly invites further research—in particular, isotope analyses of the human remains found in the Dutch and Belgian elite burials—in our opinion, these examples already demonstrate that not only was there a deeply rooted understanding of Hallstatt culture elite objects and burial practices in the Low Countries, but there seems to have also been an awareness and understanding of Dutch and Belgian funerary customs in the Central European Hallstatt culture. Embracing the practice-based approach can lead to a renewed understanding of the entanglement of these burials. The Early Iron Age burials reflect meaningful transcultural processes, rather than only the exchange of objects; and we argue that we need to adjust our perception of the large-scale interactions testified to in the elite burials of the Low Countries. It is time to revisit this formative period in Europe's past and the elite burials that so characterize it.