Introduction

The written sources record that the second Punic War was fought between 218 and 201 bc. These dates are traditionally considered to be the starting point in a long process of profound transformations in the socio-political and socio-economic organization of the communities living in the Iberian Peninsula, which led to their incorporation into the Roman political and economic system at the end of the first century bc (Carrocera & Camino, Reference Carrocera, Camino and Fernandez Ochoa1996; Rodríguez-Colmenero, Reference Rodríguez-Colmenero and Rodríguez Colmenero1996; Martín-Bueno, Reference Martín-Bueno2000–2001; Arasa, Reference Arasa2008; Nolla et al., Reference Nolla, Palahí and Vivo2010).

Animal bones have been one of the last archaeological elements to be used to obtain data about the Roman conquest (MacKinnon, Reference MacKinnon2007: 486–492) and yet their study has demonstrated their great potential for the investigation of such important topics as human diet and animal husbandry, and therefore the socio-economic transformations in the newly-conquered territories. Some of the first studies on these topics were by Grant (Reference Grant and Todd1989), Columeau (Reference Columeau1991), and King (Reference King1999).

A large corpus of faunal studies covering the whole area of Hispania Tarraconensis is currently being assembled, making it possible to shed light on some aspects of Iberian socio-economic transformations. It was this growing body of research (and therefore of interest in the contribution of faunal studies to the process of Romanization) that motivated the first scientific meeting in 2013 in León on ‘Romanization in the Iberian Peninsula: A Zooarchaeological Perspective’ (Valenzuela-Lamas et al., Reference Valenzuela-Lamas, Colominas and Fernández Rodríguez2013). The aims of the meeting were to share knowledge about human diet and livestock management in Iberia before and after the Roman conquest. At this meeting, most researchers presented results from sites, regions, or territories separately.

At the first meeting of the International Council for Archaezoology (ICAZ) Roman Period Working Group in Sheffield in 2014, ‘Husbandry in the Western Roman Empire: A Zooarchaeological Perspective’, the authors of this article presented a joint communication which constituted a first attempt at systematizing the archaeozoological data for different parts of Iberia. Here, we build on that communication in order to offer a first synthesis of the main archaeozoological data from Hispania Tarraconensis, following the pioneering works of Anthony King (Reference King1999, Reference King, Keay and Terrenato2001).

The aim of this article is to characterize animal husbandry and hunting practices in Hispania Tarraconensis, and therefore to investigate one of the most important economic activities in ancient societies. This approach allows us to discern whether there were different patterns in the area before the Roman conquest and whether these endured. We shall not limit ourselves to a given region or particular sphere of faunal study but provide an overview of observable changes in animal husbandry and hunting through an analysis of the different zones in Hispania Tarraconensis.

In order to fulfil these objectives, we present archaeozoological data from ninety-four sites, located in the north-west, north, centre, north-east, and east of the Iberian Peninsula occupied between the fifth century bc and the third century ad.

Materials and Methods

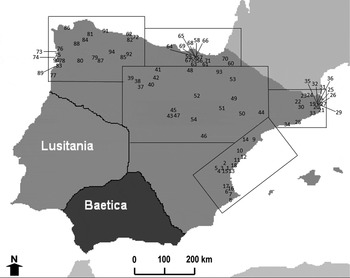

The faunal remains (Table 1) come from ninety-four sites located on the Atlantic seaboard, the Central Plateau (Meseta), and the Mediterranean part of the Iberian Peninsula. Sites in the Atlantic region have been divided into two areas, north and north-west; those in the northern and southern parts of the Central Plateau (Meseta) are grouped in a single central area; finally, Mediterranean sites were separated into north-east and east (Figure 1). All the samples represent the remains of meat production and consumption, since samples from ritual deposits have not been included. Despite the small number of some samples, all are representative of the whole assemblage.

Figure 1. Location of sites mentioned in the text. The numbers refer to the list in Table 1.

Table 1. Archaeological information about the sites mentioned in the text.

The samples come from settlements with different functions, such as oppida, villages, villae, towns, and secondary agglomerations (Table 1). The data are presented site by site, following these categories, to facilitate the interpretation of the data and their future use by researchers who may not be able to access the original studies directly, as many have been published in regional journals. The occupation of these sites has been classified into two general periods: from the fifth to the third/second centuries bc (Middle Iron Age) and from the second/first century bc to the third century ad (early Roman period). This classification allows us to observe general patterns in animal husbandry for the Iberian Middle Iron Age and compare them with the early Roman period.

In order to characterize livestock and hunting practices, the archaeozoological study has centred on the analyses of taxonomic representation of all the species documented (NISP frequency) and the size of the main domestic taxa (Ovis aries, Sus domesticus, and Bos taurus) by estimating their withers heights (Vitt, Reference Vitt1952; Teichert, Reference Teichert1969, Reference Teichert and Clason1975; von den Driesch & Boessneck, Reference von den Driesch and Boessneck1974). Measurements were taken following von den Driesch (Reference von den Driesch1976) and refer only to adult animals without any pathology. These two indicators have been chosen as they are the ones most commonly used in publications, but age and sex estimates and anatomical representation are often not specified in studies. However, information available about those aspects will be included, as far as is possible.

Results

The archaeozoological data are presented by periods, differentiating between the Middle Iron Age (fifth to third/second centuries bc) and the early Roman period (second/first century bc to third century ad). Within each period, the data are presented by areas, focusing on NISP frequencies and withers height.

Middle Iron Age (fifth to third/second centuries BC)

NISP frequencies

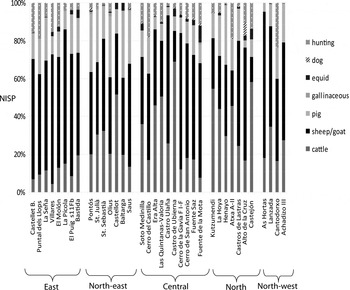

The extensive study of animal bone samples from contemporaneous settlements in the east of the Iberian Peninsula (the modern region of Valencia) reveals considerable diversity in terms of animals (Figure 2). The main species found at the sites are domestic: sheep, goat, pig, cattle, horse, donkey (and the hybrid forms, mule and hinny), dog, and chicken. Despite this diversity, there is a clear emphasis on sheep/goat, with a predominance of sheep. The presence of cattle and pigs varies depending on the environment of the sites in which they occur. Cattle, for example, are dependent on water availability. In addition, wild resources are always present, although their importance varies. The main species hunted are red deer and rabbit. Other minority species include roe deer, wild boar, bear, badger, fox, hare, and lynx. Bird remains, including partridge, golden eagle, griffin vulture, mallard, little bustard, pigeon, gull, and Cory's shearwater, have also been observed (Iborra Eres, Reference Iborra Eres2004; Iborra Eres & Pérez Jordà, Reference Iborra Eres, Pérez Jordà, Groot, Lentjes and Zeiler2013).

Figure 2. Frequency in per cent of faunal remains from Middle Iron Age sites by area.

In the north-east (present-day Catalonia), domestic animals are also predominant and wild animals are rarely present (only cervidae and leporidae remains have been documented). Among the domestic animals, sheep and goat remains predominate (Figure 2). They represent 50 per cent of the total NISP in most of the assemblages. Cattle are the second-most abundant species, followed by pigs, whereas dogs and horses are very scarce or absent. The site of Castellot (n. 23, Figure 1, Table 1), located in the Pyrenees at 1148 m asl, does not follow this general trend. There, cattle remains dominate the assemblage.

In the central area (present-day regions of Madrid, Valladolid, and Burgos), two different trends have been identified (Figure 2). At most sites, including Cerro del Castillo (n. 38 Figure 1, Table 1), Castro Ulaña (n. 41 Figure 1, Table 1), and Fuente de la Mota (n. 46 Figure 1, Table 1), sheep and goat remains predominate. In contrast, at other sites, like Era Alta (n. 39 Figure 1, Table 1) and Las Quintanas-Valoria (n. 40 Figure 1, Table 1), cattle are dominant. However, at all sites, the third-most abundant species is pig, while remains of horses and dogs are scarce. Game, essentially red deer and rabbit, is also found on all sites, albeit in small percentages. These differences in the frequencies of the main domestic species have been attributed to environmental conditions (Castaños, Reference Castaños1997: 661). Cattle are more frequent in the more humid northern plateau whereas in the drier southern plateau and the Jarama and Manzanares valleys, sheep reach percentages of 50 per cent of the total NISP.

This dual trend has also been observed in the north, although cattle remains are preponderant at most sites; at Kutzumendi (n. 55 Figure 1, Table 1) and Castejón (n. 61 Figure 1, Table 1) they even represent over 50 per cent of the total NISP (Figure 2). The predominance of caprines on some sites in the area, such as Castros de Lastras (n. 59 Figure 1, Table 1) and Alto de la Cruz (n. 60 Figure 1, Table 1) has been associated with their proximity to the Ebro valley (Castaños, Reference Castaños1997: 663). As is the case in other areas, the third species in order of frequency is pig, while horses and dogs are scarce. The high frequencies of wild animal remains in Castejón (n. 61 Figure 1, Table 1) (mostly collected red deer antlers) are related to bone working (Castaños & Castaños, Reference Castaños and Castaños2009b: 205–06).

In the north-west, the results resemble more those in the eastern and north-eastern areas (Figure 2). Domestic animals predominate and wild animals are very scarce. The results from Cantodorxo (n. 75 Figure 1, Table 1), however, should be highlighted, as the remains of prey reach 20 per cent of the total NISP, although represented solely by fox, perhaps because its fur was exploited (Fernández Rodríguez et al., Reference Fernández Rodríguez, Rodríguez López, Ferré and Rey Salgado1998). The main domestic species are sheep and goat, with cattle the second-most abundant species, followed by pigs. The absence of horse and domestic fowl in all these sites should also be noted. This has been linked with cultural factors (horse meat was not eaten) and a late introduction of hens in the north-west (for more detailed information, see Fernández Rodríguez, Reference Fernández Rodriguez, Fuertes Prieto and Fernández Freire2003).

Body size

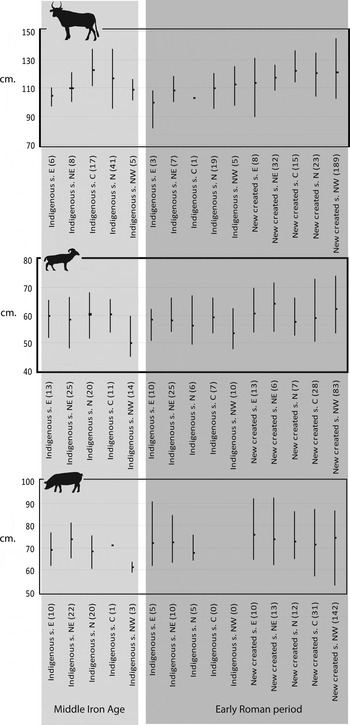

Figure 3 shows the withers height for the main domestic species in each area. In the east, the mean height of cattle is 109.6 cm, with values between 97 and 110 cm. Sheep withers heights vary from 56 to 66 cm. The measurements of pig bones fall between 62 and 77 cm withers height.

Figure 3. Withers height of cattle, sheep, and pig remains in the east (E), north-east (NE), centre (C), north (N), and north-west (NW) of the Iberian Peninsula.

The calculation of the size of the main domestic animals in the north-east shows that they were slightly taller than those in the east. Cattle withers heights range between 100 and 120 cm with a mean of around 110 cm. Sheep withers heights are between 45 and 68 cm with a mean of 59 cm. Pig withers heights, with values between 65 and 81 cm, are more variable than those in the east.

The tallest cattle are documented in the central area, with withers heights ranging between 112 and 137 cm. On the other hand, sheep values closely match data from the east and north-east, with values between 54 and 66 cm and a mean of 60 cm. Only one withers height of 71 cm has been recorded for pigs, i.e. a value close to those found in the east and north-east.

The northern values are similar to the central ones, with high values for cattle withers height, although they vary more here than in the centre, with values ranging between 95 and 137 cm. As for sheep, withers heights appear similar to those documented in the east, north-east, and centre, with values between 52 and 68 cm. The measurements of pig bones also fall within the range of the other areas, with withers heights between 61 and 75 cm.

The withers heights in the north-west resemble those in the east and north-east, especially for cattle, whose heights range from 100 to 115 cm. Values for sheep withers height fall between 45 and 60 cm with a mean of 50 cm. Pigs withers height varies little (because only three values were recorded); the individuals appear to be smaller than in the other areas, with values between 59 and 63 cm.

Early Roman period (second/first century bc to third century ad)

The samples from the early Roman period come from oppida, rural settlements, villas, towns, and production sites. At the same time, the data derive from indigenous sites and newly-founded sites (Table 1) and will be presented according to the type of sites represented and the time of their foundation.

NISP frequencies

The samples from indigenous sites in the east reflect a model of consumption in which caprines and pigs are the most abundant (Figure 4). Wild animals are also frequent and a wide variety of species, from large to small prey, has been recorded. These sites disappear at the end of the first century ad.

Figure 4. Frequency in per cent of faunal remains from early Roman indigenous sites by area.

Two samples come from the Roman town of Valentia (Figure 5). The sample of Valentia ALM (n. 13 Figure 1, Table 1) shows the same trend as that observed in the indigenous oppida: a predominance of sheep and goat remains followed by pigs and cattle and a small amount of wild species. The sample of Valentia Trenor (n. 13 Figure 1, Table 1) reflects a different pattern, with a large proportion of pigs and hunted species, but only further studies will shed light on the relative frequencies of species at this site. This latter pattern is also documented in the town of Lesera (n. 14 Figure 1, Table 1). The faunal evidence reveals that pig and rabbit are the most common species, and a slightly smaller proportion of sheep than goat is noted.

Figure 5. Frequency in per cent of faunal remains from early Roman towns by area.

This trend is also detected in the villae (Figure 6), with a preponderance of pig remains. Caprines continue to be significant and there are more goat than sheep remains. Equids are also important in the villa of Cornelius 1 (n. 17 Table 1, Figure 1) (5 per cent of total NISP). Hunting is significant and in some villae wild animals reach a high percentage. Another characteristic of these sites is the large amount of marine shells and poultry remains (Sanchis, Reference Sanchis, Jimenez and Ribera2002, Reference Sanchis, Albiach and de Madaria2006).

Figure 6. Frequency in per cent of faunal remains from early Roman villae by area.

No pattern can be detected in the secondary agglomerations (Figure 7). Each site has a different profile, with caprine and horse, caprine, or cattle dominant. This variation can be linked to the function of the site, as La Pícola (n. 8 Figure 1, Table 1) is a trading post, Barrio Tunos (n. 15 Figure 1, Table 1) is a mansio and Les Faldetes (n. 16 Figure 1, Table 1) a small rural settlement.

Figure 7. Frequency in per cent of faunal remains from early Roman secondary agglomerations by area.

Two patterns can however be observed in the north-eastern area. The first, characterized by the continued dominance of sheep and goat remains, is only documented on indigenous sites (Figure 4). Once again, the upland site of Castellot (n. 23 Figure 1, Table 1) does not follow this general trend, with a predominance of cattle remains, showing that animal husbandry was practised in this mountainous area in accordance with the surrounding environment.

The newly-created sites show a change in pattern. The villae are characterized by a general decline in the number of sheep and goat remains and an increase in cattle and pigs (Figure 6). This decline in sheep and goats is also attested in the towns with a clear predominance of pig remains (Figure 5). At sites interpreted as secondary agglomerations, the main taxa are more equally represented (Figure 7). A general small increase in wild remains is also attested in all the newly-created sites.

A general increase in caprine remains is documented in all the assemblages from the central area. There is a predominance of caprine remains (50–68 per cent of the total NISP) on all indigenous sites under study, whereas pig and cattle remains do not come to more than 20 per cent (Figure 4). The presence of game is significant at the sites of La Coronilla FI–II (n. 48 Figure 1, Table 1) and El Palao (n. 50 Figure 1, Table 1) (15 and 16 per cent respectively of the total NISP).

The same pattern is documented in the towns with a predominance of caprine remains (40–55 per cent of the total NISP), and an increase in pig and prey remains (Figure 5). At La Cava (n. 54 Figure 1, Table 1), the frequency of cattle (30 per cent of the total NISP) is significant, and it has been associated with the site's location on the northern plateau. Game maintains percentages of about 20 per cent at Tiermes (n. 52 Figure 1, Table 1), Bilbilis (n. 51 Figure 1, Table 1), and Los Bañales (n. 53 Figure 1, Table 1), and therefore the contribution of meat from prey would be considerable on these settlements.

Only one villa is available for the central area, showing a predominance of sheep/goat, followed by hunting remains (Figure 6). The presence of poultry is equally noteworthy. Similarly, only one example is available from a secondary agglomeration, the military site of Cerro de la GaviaFIII (n. 43 Figure 1, Table 1), where a predominance of sheep and goat remains is also attested (Figure 7).

No important changes compared to the previous period are documented in the northern area. Most of the indigenous sites are dominated by cattle remains. The exception is Atxa A-I (n. 58 Figure 1, Table 1) where a predominance of caprine remains is documented (50 per cent of the total NISP), illustrating the dual pattern already observed in the previous period. However, the importance of pigs at this time, on settlements such as Peñas de Oro (n. 64 Figure 1, Table 1) and Iruña-Veleia (n. 65 Figure 1, Table 1), should also be stressed, as they reach 30 and 40 per cent respectively of the total NISP.

This dual pattern is also documented in the newly-created sites. A predominance of cattle remains is observed in the town of Arcaya (n. 66 Figure 1, Table 1)— where pig is the second-most abundant species—and in the villa of Oioz (n. 70 Figure 1, Table 1) (Figures 4 and 5). In contrast, caprine remains are dominant in the villa of Alto de la Cárcel (n. 71 Figure 1, Table 1) (Figure 5). All secondary agglomerations show a predominance of cattle remains, and a similar presence of pigs and caprines (Figure 7).

Several traits can be noted in the north-western area. Two patterns exhibited by indigenous sites appear to be linked to their geographical location (Figure 4). There is a predominance of sheep and goat remains followed by cattle on coastal sites, such as Santa Tegra (n. 77 Figure 1, Table 1), Achadizo IV (n. 76 Figure 1, Table 1), and A Peneda (n. 78 Figure 1, Table 1), following the coastal settlement pattern documented in the previous period. By contrast, cattle, followed by sheep and goat remains, predominate at inland sites, such as Valencia do Sil (n. 78 Figure 1, Table 1), Santomé I (n. 80 Figure 1, Table 1) or Viladonga (n. 81 Figure 1, Table 1), indicating that animal husbandry was practised in accordance with the possibilities offered by the environment. A general increase in the number of dog remains in comparison with the previous period should also be noted. They are especially numerous at the site of Vigo.

Sites interpreted as villae in this north-western area show a general decline in sheep and goat remains and an increase in cattle and pig remains (Figure 6), as has been seen in the north-east. This pattern is also documented in towns with a clear predominance of cattle remains (Figure 5). This dominance of cattle but also pig remains is also attested in the secondary agglomerations (Figure 7). Domestic fowl, horse, and wild species also increase in frequency during this period in all the new foundations, as has been attested in the other areas.

Body size

Figure 3 shows the evolution in size of the main species in the five study areas. In the east, the withers height of the main species is as follows: cattle size rose to between 97 and 108 cm on indigenous sites and to between 90 and 130 cm at the newly-created sites, i.e. the sites established during Romanization have animals with a greater withers height than those of the Middle Iron Age. The same is true for sheep and goat, which have slightly higher withers, with a maximum of 70 cm in both species. The measurements of early Roman pig bones from indigenous sites fall within the range of Middle Iron Age remains, but the standard deviation increases. At the newly-established early Roman sites the mean height of pigs is 76 cm, with values from 68 to 91 cm, showing the presence of both small animals (also documented during the Middle Iron Age) and large animals.

A change in animal size is also evidenced in the north-east. The calculation of cattle withers height shows a clear increase in size during this period. This increase is mainly documented in the newly-created sites, with a spread between 110 and 130 cm. The values from indigenous sites are similar to those recorded in the Middle Iron Age (100–118 cm). The sheep withers height also increases at sites founded after the conquest, with a mean height of around 65 cm and a maximum value of 72 cm. By contrast, on indigenous sites the mean and the maximum values do not vary in relation to the previous period, although smaller individuals are no longer found. The withers height calculated for early Roman pig remains in the north-east is similar to that obtained from the eastern area. Mean values do not vary between the two periods but the standard deviation increases, with a maximum value of 85 cm on indigenous sites and of 93 cm in the new sites of the early Roman period.

Different results were obtained in the central area. No changes in cattle size have been recorded, with values ranging between 114 and 136 cm in the newly-founded sites. Only one cattle withers height of 102 cm has been documented from an indigenous site in the early Roman period. The sheep withers heights show an increase in variability, with larger values only found on the newly-created sites, and a mean height of around 59 cm and a maximum value of 73 cm. No pig values have been recorded on indigenous sites, but the data from the newly-established sites show an increase in the standard deviation, with a maximum value of 87 cm and minimum value of 57 cm.

Trends in the north in the early Roman period appear to be similar to patterns exhibited in the central area. The Romanization of the north appears not to have been accompanied by a change in cattle size, with individuals between 95 and 120 cm at indigenous sites and between 104 and 135 cm in the newly-created sites. Similarly, no change is documented in sheep size. The values fall between 49 and 67 cm on indigenous sites and between 53 and 74 cm at the newly-established sites, with means of 56 and 57 cm respectively. By contrast, pig withers heights vary more in the early Roman period but only in the newly-created sites. Pig values show a similar mean (73 cm) but a maximum value of 86 cm and minimum value of 65 cm on the new sites of this period.

The values in the north-west are very close to those calculated for the north-east. Large cattle are clearly present in the newly-created sites, with values reaching 144 cm at the withers. Similar results are also documented for sheep, with a withers height mean of 62 cm and a maximum value of 74 cm. The standard deviation of pig remains also increases in the north-west with a maximum value of 86 cm, in comparison with 63 cm in the Middle Iron Age.

Discussion: Animal Husbandry and Hunting Practices in Hispania Tarraconensis

The data presented here allow us to make some general remarks about livestock composition and hunting before and after the Roman conquest in Hispania Tarraconensis.

Animal husbandry during the Middle Iron Age was focused on the exploitation of sheep, goat, cattle, and pig. Cattle, followed by caprines, were the main species in the northern area, whereas sheep and goat, followed by cattle, were the most important species in the central, eastern, north-eastern, and north-western regions. Sheep and pig were similar in size in the east, north-east, centre and north, but smaller in the north-west. Some differences also existed in cattle size, as they were larger in the centre and north than in the other areas, where they were of similar size.

The differences in the representation and size of cattle may have been caused by environmental factors, as conditions in the north of the Iberian Peninsula would have been more favourable to the expansion of pastures and more suitable for herds of cattle than in the Mediterranean area, with its drier climate (Castaños, Reference Castaños1997; Blasco, Reference Blasco and Burillo1999; Mariezkurrena, Reference Mariezkurrena2004). This hypothesis, however, does not explain the data obtained so far in the north-western area, which come mainly from coastal settlements. It is therefore probably more appropriate to consider a coastal pattern that would reach as far as the Ebro, where sheep and goat husbandry would be of greater value, and contrast it to an inland pattern, in which cattle would be of more importance and also of larger size.

The information currently available about mortality profiles for Middle Iron Age sites in all areas under study shows that cattle, sheep, and goat were slaughtered at juvenile and adult ages on all sites, suggesting that these animals were used for wool, milk, traction, but also meat. Pigs were slaughtered at juvenile and subadult ages, being exploited for their meat.

This pattern changes with the Roman conquest. Despite some differences between sites and areas, we can identify some general patterns that reflect these changes. First, there is a general increase in the frequency of pig remains in all areas, especially at the newly-created sites. At the same time, a greater diversity in the size of these animals coincides with the arrival of the Romans in the five areas, with both smaller and larger individuals than in the previous period.

Second, the economic importance of cattle increases with the conquest in the north-west and in the north-east, to the detriment of the caprines, on sites continuously occupied from the Middle Iron Age as well as on those founded after the conquest. Cattle are also larger on the newly-established sites in the north-west and north-east.

Third, the frequency of sheep remains increases in the central area at the expense of cattle, and sheep becomes the most important species on all sites under study there after the conquest. However, there is no clear change in their size.

Mortality profiles demonstrate an increasing tendency to slaughter caprine and cattle as adults in all areas, attesting to an increase in the specialization of these animals for purposes other than meat production. In contrast, pigs gradually become the meat-producing animals and they were slaughtered at younger ages.

These changes in animal frequency, withers height, and kill-off-patterns are indicative of a real change in animal husbandry with the conquest of Hispania Tarraconensis. Meat production becomes more focused on pork in the whole province. Pigs are the most profitable species for meat production since they reproduce quickly, their diet is omnivorous, and they require little maintenance (Thurmond, Reference Thurmond2006: 210). We therefore consider that the increase in pork consumption should be directly linked with the increasing concentration of population in larger urban centres. The variability in pig size—since all the withers heights are for adult animals—may be the result of breeding two types of animals, one for reproduction and the other for fattening. It should also be borne in mind that the villae, as agricultural production centres, may have promoted pig breeding in a complementary framework of arable farming and husbandry.

Further, we consider that the increasing frequency of cattle in the north-east and north-west and the presence of larger animals reflect an interest in draught animals. This change may have been the result of a wish (or need) to exploit cultivated lands in a more intensive way, or of working new and poorer land, as well as an increase in overland trade.

The clear increase in sheep in the central area shows the economic importance of this region as a wool producer during the early Roman period, as reported in written sources by Polybius (Histories. 34, 8, 9) and Diodorus (Library of Hist. 5, 33, 2). Sheep farming would continue to be the main livestock activity in the area until the mid-twentieth century.

Other domestic animals on which the conquest appears to have had an impact are horse, dog, and chicken. The economic importance of horse increases with the conquest, its remains being very scarce during the Middle Iron Age but a little more common during Roman times. After the Roman conquest, the presence of donkeys and hybrid forms used as pack animals also increases. The frequency of dogs remains stable in the eastern area but grows in the north-east, north-west, and central areas with the conquest. It is at this time that a large increase in sizes is documented, with three morphotypes: hypometric dogs (between 22 and 37 cm tall); medium-sized individuals (eumetric dogs); and individuals taller than 60 cm at the withers (hypermetric dogs) (for more detailed information, see Altuna & Mariezkurrena, Reference Altuna and Mariezkurrena1992; Fernández Rodríguez, Reference Fernández Rodriguez, Fuertes Prieto and Fernández Freire2003; Sanchis, Reference Sanchis, Albiach and de Madaria2006; Colominas, Reference Colominas2016b; Iborra Eres, Reference Iborra Eresforthcoming). Similar considerations apply to chicken remains. Whereas they are very scarce during the Middle Iron Age, they become more common during the Roman period and increase in size (Castaños et al., Reference Castaños, Castaños and Martín-Bueno2006).

New species, such as cats, camelids, or monkeys were introduced. The domestic cat is well documented at Liria/Edeta (Iborra Eres, Reference Iborra Eresforthcoming) and Valencia do Sil (n. 79 Figure 1, Table 1), where it would have been appreciated to exterminate small rodents. The dromedary appears more ephemeral; its arrival may have been a consequence of the intense commercial activity that characterizes the early Roman period (Morales Muñiz et al., Reference Morales Muñiz, Riquelme and Liesau von Lettow-Vorbeck1995). They may have been used as pack animals or in recreational activities. The ferret raises questions about its domestic or wild nature, but the main context in which it appears, a ritual pit in the town of Liria that contained the remains of ritual feasting and a large number of non-consumed dog skeletons (Iborra Eres, Reference Iborra Eresforthcoming), together with information provided by Strabo from the first century bc (Geography, 3, 2, 6) and by Pliny from the first century ad (Hist. Nat. 8, 81, 218) about the use of ferrets in the Iberian Peninsula to hunt rabbits, lead us to suggest that it was domesticated.

Some changes in hunting activities are also documented. The frequencies of the remains of wild animals indicate that hunting was marginal in the five study areas during the Middle Iron Age, albeit a little more important in the east and centre than in the other regions. In all five areas, the wild animals recorded are mainly red deer, roe deer, and rabbit, with boar, bear, and fox appearing more sporadically. Hunting may have been a leisure activity, or carried out to protect crops and to obtain skins, as the age and gender profiles of the carcasses indicate. This pattern continues during the early Roman period in the five study areas, with an increase in the number of wild animals recorded on the newly-established post-conquest sites. The wild species identified are red deer, roe deer, wild boar, bear, fox, badger, wildcat, hare, and rabbit. The species represented by the largest number of remains are still deer and rabbit, which are present in all the records analysed. Rabbit has been considered to represent prey in this study, although leporaria (warrens) may have existed in some towns, like Asturica (n. 85 Figure 1, Table 1) and Lesera (n. 14 Figure 1, Table 1). In all cases, however, the presence of butchery marks indicates the anthropic origin of the remains. Hunting of small carnivores was practised to obtain their skin, as shown by the butchery marks on their bones. The sites with the largest quantities of deer are usually located in woodlands, although the frequency of this species is also significant in some urban villae, where hunting would be a leisure activity and mainly linked to high status (for more detailed information about the relationship between hunting practices and status, see Fernández Rodríguez, Reference Fernández Rodríguez2003; Iborra Eres, Reference Iborra Eres2004).

Wild birds are also common. The wild birds most frequently hunted and consumed in Roman settlements are partridges, anatidae, pigeons, and doves, although we do not know whether doves were bred in semi-freedom or lived in towers or lofts.

Conclusions

This study has been presented as an overview of hunting and animal husbandry in Hispania Tarraconensis. We have attempted to show that the new territorial and administrative organization that came into being with the Roman conquest of the Iberian Peninsula affected the husbandry that had been practised previously and hence we hope to have demonstrated the potential of archaeozoology to shed light on aspects related to the socio-economic transformation of Hispania Tarraconensis.

Despite differences between the five areas studied, some general patterns emerge. Hunting increases with the Roman conquest, although it was still a minor aspect in terms of meat supply, and linked to leisure activities rather than subsistence. In territories in which caprines were previously the most important livestock, sheep and goat lose importance at the expense of cattle and pigs. By contrast, sheep farming becomes increasingly important in the central area. The three species that increase in importance during the early Roman period also increase in size. At the same time, some new species, such as cats, camelids, and monkeys, are introduced for both economic activities and leisure. We consider that these patterns are the result of more intensive and specialized livestock farming in all the conquered territories, apart from the north, where no substantial changes have been documented.

Hispania Tarraconensis is seen to be an unequally Romanized province, exploited differentially with respect to animal husbandry. We suggest that arable farming was of greater importance in coastal areas, hence the increasing frequency and size of cattle. Caprines were also important, as these animals are the perfect complement when land is left fallow (Buxó & Piqué, Reference Buxó and Piqué2008). In this sense, livestock would have been specialized in terms of products, but diversified in the kinds of animals kept. In contrast, in the central area, sheep farming appears to have been one of the major economic activities, while in the northern area, with its large natural pastures, cattle would have continued to be the main form of livestock.

It should finally be noted that this article is a first attempt at a collaborative project by several archaeozoologists who work in different parts of the Iberian Peninsula. For this reason, we have highlighted aspects common to all areas and general trends. Nevertheless, we have provided information site by site (see Table 1) so that other researchers can use it; it also serves to show, but not discuss, the differences between settlements. We hope that this article acts as a stimulus to this discussion.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the EJA editorial team for their assistance with the English language. Two anonymous reviewers provided comments that greatly improved the paper. L. Colominas is supported by a postdoctoral grant (n° FPDI-2013-18324) from the Government of Spain.