The so-called postwar liberal international order is on the brink of falling into two prevailing traps. The prolonged trade war between the United States and China seems to foreshadow what Graham Allison calls the “Thucydides Trap”—a highly likely military conflict or even catastrophic war between a ruling state and a rising power that takes place when the power gap between them narrows.Footnote 1 While Allison's Thucydides Trap warning reflects some elements of truth, any hegemonic war between the United States and China seems unthinkable given the nuclear deterrence relationship between the two nations under the logic of mutual assured destruction.Footnote 2

This essay focuses on the “Kindleberger trap,” an equally important, but largely neglected, danger for the current international order. A term coined by Joseph Nye Jr., the Kindleberger trap refers to a situation in which no country takes the lead to maintain international institutions in the international system. Historian Charles Kindleberger famously put the blame for the disastrous decade of the 1930s on the lack of U.S. leadership in providing global public goods after the collapse of Pax Britannica.Footnote 3

Using the Kindleberger trap as a lens, in the early days of U.S. president Donald Trump's first term, Nye warned that Trump should “worry about a China that is simultaneously too weak and too strong.”Footnote 4 If China becomes too strong, it might drag the United States into the Thucydides Trap. However, if China is too weak, it might shirk its responsibility to play a leadership role in any new international order, which in turn would make the world face another Kindleberger trap. Although Nye's article focuses on the perils of managing a rising China, the implicit message emphasizes the indispensable responsibility of the United States in maintaining its leadership of the current international institutions.

As it turns out, President Trump has not only disregarded such prescriptions but also actively engaged in destroying international institutions that the United States has both built and led. Just a few examples will suffice to demonstrate this point. To begin with, as soon as Trump assumed office in January 2017, he withdrew the United States from the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), an Obama-era agreement aimed at precluding China from writing “the rules for the world's fastest-growing region” in international trade.Footnote 5 Then in June 2017, Trump announced that the United States would withdraw from the Paris Climate Agreement. In May 2018, Trump pulled the United States out of the Iran nuclear deal despite mounting criticism from its European allies. Moreover, some reporting found that Trump had threatened to withdraw from the World Trade Organization (WTO) more than one hundred times.Footnote 6 In April 2020, in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic, Trump suspended U.S. funding to the World Health Organization (WHO), alleging that WHO has “severely mismanage[ed] and cover[ed] up” the coronavirus threat.Footnote 7

Interestingly, China—widely perceived as a revisionist state—has a leader who has pledged to protect the existing international order. This statement was made at President Xi Jinping's address at Davos in 2017, but critics argue that it was just a rhetorical gesture.Footnote 8 However, some sophisticated studies suggest that China has largely been a “good” citizen in international institutions since the end of the Cold War.Footnote 9 Why, during that same time period, did the United States behave destructively toward many international institutions that it helped to form and used to lead? Why did China support and even save these existing international institutions? What are the implications of the institutional behaviors of the United States and China for the future of the international order?

This essay attempts to shed some light on these questions from an institutional-balancing perspective. It suggests that we should not worry about the Kindleberger trap, because institutional competition among great powers and institutional change within the current order will help to maintain these institutions as well as to avoid the Kindleberger trap during the order transition. What the United States and China have done regarding international institutions reflects their different institutional-balancing strategies during this period. The real danger of the Kindleberger trap lies in the loss of confidence in international institutions, not in the decline of U.S. hegemony per se. What states, including the United States, should do is to reembrace and reinvigorate the role of multilateralism in world politics so that the dynamics of institutional balancing and subsequent institutional changes in the context of U.S.-China competition will not deprive international society of the public goods and normative values of international institutions. The future international order should not be led by a single country, but by dynamic and balanced international institutions.

International Institutions and International Order

International order is a contested concept in world politics. Realists normally equate the international order with the international system, which is defined by material power capabilities among states. Liberals mainly define the international order by the existing institutional arrangements. For constructivists and English School scholars, the international order is conceptualized as a combination of prevailing norms, ideas, rules, and material power, with an underlying emphasis on culture and norms.Footnote 10 In this essay, we take a hybrid realist-liberal perspective, highlighting the two important components of international order: power distribution and international institutions.Footnote 11 Recalling our previous discussion on the crisis for the current international order, the Thucydides Trap focuses on the change in power distribution between ruling states and rising powers; the Kindleberger trap refers to the danger of potential disarray or the collapse of international institutions.

It is worth noting that there are two types of international institutions. Those of the first type are called primary institutions or fundamental institutions, referring to the fundamental norms and principles that determine the players as well as the basic game of international relations, norms such as sovereignty, nonintervention, territoriality, and the equality of peoples.Footnote 12 Those of the second type are called secondary institutions, including intergovernmental organizations, nongovernmental organizations, as well as treaties and conventions among nation states. The Kindleberger trap largely focuses on the latter, as the concern is a potential dearth of global public goods that are mainly provided by the major secondary institutions of the world, such as the open trading system under the WTO as well as the financial stability ensured by the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank in the postwar era. International institutions are the most dynamic, constitutive part of international order because states interact with one another through rules and institutions on a daily basis. International institutions can be modified and changed according to shifting state interests as well as power struggles among states within institutions.Footnote 13 The relationship between institutions and power distribution, the two main components of international order, is complex. They sometimes interact in ways that are mutually reinforcing and at other times they offset each other's influence. For example, the power struggle between ruling states and rising powers might lead to institutional changes, as occurred with the establishment of U.S.-led international institutions after World War II.Footnote 14 Similarly, some incremental institutional changes might trigger power struggles among states in the power-based order. For example, China's Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) and Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) have caused some concerns in the United States that China might eventually challenge U.S. leadership as well as U.S. hegemony. This institution-rooted worry has triggered a strategic and power-based competition between the United States and China in the international system.Footnote 15

The changes in international institutions will gradually constitute an incremental transition in international order. Differing from liberal scholars such as G. John Ikenberry, who argue that the U.S. decline will not lead to the demise of the basic logic of the liberal international order “as a system of open and rule-based order,”Footnote 16 we suggest that the rules, institutions, and even logic of the liberal international order are not static in nature. Instead, they will change, not just because of the decline of U.S. hegemony but also due to the constant modifications and changes of international institutions embedded in the current liberal order. In other words, U.S. decline is not a necessary or sufficient condition of international order transition, because the international order is inherently in flux no matter whether it is led by the United States or not.

Therefore, the Kindleberger trap's original warning, that the decline of U.S. hegemony will lead to the collapse of international institutions or international order in general, is misleading. It ignores the fact that international institutions actually serve as diplomatic tools for states to navigate through the dynamics of order transition. Depending on the institutional strategies that states adopt and the ways in which they interact with one another, we will see different institutional changes during an order transition. Institutional competition and subsequent institutional change can help preserve the dynamics of international institutions as well as avoid the Kindleberger trap during a period of international order transition.

Institutional Balancing: A Micro Approach to Avoiding the Kindleberger trap

It is worth noting that Robert Keohane also suggests that international institutions will survive after the decline of U.S. hegemony.Footnote 17 Keohane's neoliberal institutionalism, however, highlights the functional utilities of institutions, such as reducing transaction costs and identifying focal points, in fostering international cooperation under anarchy. Differing from Keohane's cooperation-based argument, we suggest that institutional competition can also help to maintain international institutions as well as the international order in general. In particular, institutional competition in the form of institutional balancing among states is a micro approach for states to maintain the dynamics of international institutions. In other words, international institutions will not easily collapse due to the decline of U.S. hegemony, as the Kindleberger trap would suggest. Competition will keep institutions alive and transformed, especially during a period of order transition.

States can rely on two different types of institutional-balancing strategies to compete with one another and to pursue their interests and exert their influence under conditions of deepening economic interdependence and globalization: inclusive institutional balancing and exclusive institutional balancing.Footnote 18 Inclusive institutional balancing refers to an institutional strategy of binding and constraining a target state within the rules, agendas, and practices of institutions. By contrast, exclusive institutional balancing means working to exclude a target state from a specific institution so that the target state will be isolated or pressured by the cohesion and cooperation of institutional grouping. In practice, the ASEAN Regional Forum (ARF) is an inclusive balancing strategy in that ASEAN (the Association of Southeast Asian Nations) has constrained China's foreign policy behavior by using the nonaggressive and cooperative security rules of the ARF since the end of the Cold War. Obama's TPP, however, is seen as exclusive institutional balancing against China because China was intentionally excluded from the TPP due to the agreement's strict entry requirements in environment and labor protection.Footnote 19

Why do states use institutional-balancing strategies? The logic is simple: Traditional military-balancing strategies, either military buildup or alliance formation, are too economically costly to be employed in dealing with states that might pose potential threats but at the same time have close economic and financial ties. Therefore, institutional balancing, an important form of soft balancing, is often chosen by states to cope with pressures and even potential threats from their target states.Footnote 20 During this current period of international order transition, institutional competition in the form of institutional balancing between the hegemon and rising powers will be further intensified.

As is often the case, the ruling power or the hegemon is the original architect of the institutions that comprise a given international order. A prime example of this is the U.S. role in creating postwar international institutions such as the World Bank and IMF, through which the United States employed inclusive institutional balancing to constrain other states’ behaviors within these institutions. Continuing this strategy into the post–Cold War era explains why the United States has admitted other major powers into international institutions, such as bringing China into the WTO.

Rising powers have to make a tough decision with regard to institutions led by the hegemon. They can choose to join these institutions and enjoy institutional benefits, such as market access, investment, and technological transfer, but by doing so, they will also be constrained by the rules and norms set by ruling states. Or, they can decide to stay away from these institutions and maintain greater autonomy, but forego the institutional opportunities and benefits. This calculus is both an economic and a social choice. Economically, rising powers need to calculate the costs and benefits of joining the institutions. Socially, they must decide whether they want to be constrained and eventually socialized by the social groupings led by the hegemon.

As historian Paul Kennedy suggests, “Hegemons always prefer History to freeze, right there, and forever. History, unfortunately, has a habit of wandering off all on its own.”Footnote 21 Great powers rise and fall in the international system, and so do institutions. Existing institutions will experience unavoidable changes and modifications because states, including both ruling powers and rising powers, can become dissatisfied with existing institutional arrangements. The cumulative institutional changes might eventually lead to international order transition, especially when the distribution of power shifts dramatically in the international system. For rising powers, an increase in material capabilities will encourage them to renegotiate the distributional benefits they receive from the existing institutions. For ruling powers, the institutional dividend that they used to enjoy will decrease over time as rising powers join and customize their behavior to the rules and norms of the existing institutions.

Therefore, states will engage in intensive institutional-balancing strategies with one another to maximize their interests and influence during the period of international order transition. In this regard, rising powers can conduct either inclusive or exclusive institutional balancing, or both, to challenge existing institutions and the powers that created them. In the former case, rising powers can work together to push for changes to the rules, especially regarding the distribution of benefits within the existing institutions. One vivid example of such cooperation is rising powers banding together to push for voting power reforms within the IMF, resulting in more weight being given to the votes of these powers.

In the latter case, rising powers may work together to create parallel institutions to those of the dominant order, employing exclusive institutional balancing to challenge the authority of the institutions led by the hegemon. The establishment of the AIIB by China and the New Development Bank by the BRICS (Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa) countries has posed a direct challenge to the World Bank and IMF in global financial governance—although the consequences of such a challenge are still not clear.

The hegemon can likewise choose inclusive and exclusive institutional balancing. Within current institutions, the hegemon can use the existing rules that it originally set to suppress rising powers’ demands and requests. It can even try to rewrite the rules to constrain rising powers’ behaviors. However, if this inclusive institutional balancing does not work simply because rising powers have been included in the institutions already and become too powerful to be constrained by the existing rules, the hegemon can choose an exclusive institutional-balancing strategy by either giving up the existing institution to build a new one or by kicking out the troublemakers—rising powers—from the existing institution. In practice, the hegemon normally combines these two strategies to fulfill its interests.

An example of inclusive balancing is Trump's renegotiation of NAFTA (the North American Free Trade Agreement) with Canada and Mexico ostensibly to maximize U.S. interests. For a similar reason, Trump threatened to withdraw from the WTO unless the organization conducted internal reforms as the United States demanded, because he believed that the WTO was set up “to benefit everybody but us.”Footnote 22 Another example of inclusive balancing is the U.S. decision to block new judges from being appointed to the WTO's appellate body in November 2019, creating the largest crisis for this organization in its twenty-five–year history.Footnote 23 The purpose of paralyzing the WTO is also to force an internal reform inside the organization. If this inclusive-balancing strategy does not work, the United States is more likely to choose an exclusive-balancing strategy to actually withdraw from the WTO and create a new parallel global trading regime.

The United States under the Obama administration refused to join the AIIB initiated by China, in part due to U.S. concerns about China's future leadership in global financial governance. Therefore, the United States chose to exclude itself from this new institution in order to delegitimate China's emerging leadership in the new international order.Footnote 24 This self-exclusion policy is another form of exclusive institutional balancing against China. Therefore, the U.S. withdrawals from international institutions and the institutional contention between the United States and China should not be seen as a sign of the beginning of the Kindleberger trap; they just reflect a normal process of institutional balancing and competition between the hegemon and a rising power during a period of order transition. Institutional competition will not kill international institutions. Instead, it will keep them dynamic and adaptive to new challenges in order transition.

Institutional Changes: A Macro Approach to Avoiding the Kindleberger trap

The purpose of institutional balancing is to strengthen a state's own power as well as to undermine its rivals’ influence through international institutions. States, especially ruling states and rising powers, will compete furiously through various institutional-balancing strategies, seeking advantageous changes to the “authority” and “rules” of existing institutions as well as preferable institutional arrangements in the future international order. Institutional balancing among states will lead to various institutional changes, therefore, which constitute a macro approach to preventing the death of international institutions and avoiding the Kindleberger trap.

Institutional authority refers to the leadership in an international institution. For example, the United States maintains its leadership role or authority in the Bretton Woods institutions, such as the World Bank and IMF. The UN's leadership and authority are shared by the five permanent members of the Security Council through their veto power. Similarly, China plays a leadership role and wields the authority in its newly initiated AIIB as well as in the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO), although Russia seems to be an internal competitor against China in the latter.

The other defining factor for an institution is the set of rules that governs and manages the member states’ behaviors and expectations within the institution. The WTO, for example, has complicated rules and regulations, including dispute settlement mechanisms, to manage trading relations and resolve conflicts among its members. It is worth noting that rules and regulations are normally set by the leading states in the institutions through negotiation and bargaining between such states and other members. Although the rules and regulations should in theory benefit all member states, the leading states usually ensure through these negotiations that they will reap the lion's share of the institutional benefits. Over time, however, the benefits accrued to the leading states from the rules and agenda setting will decrease as more members join the institutions, following the economic law of diminishing returns.

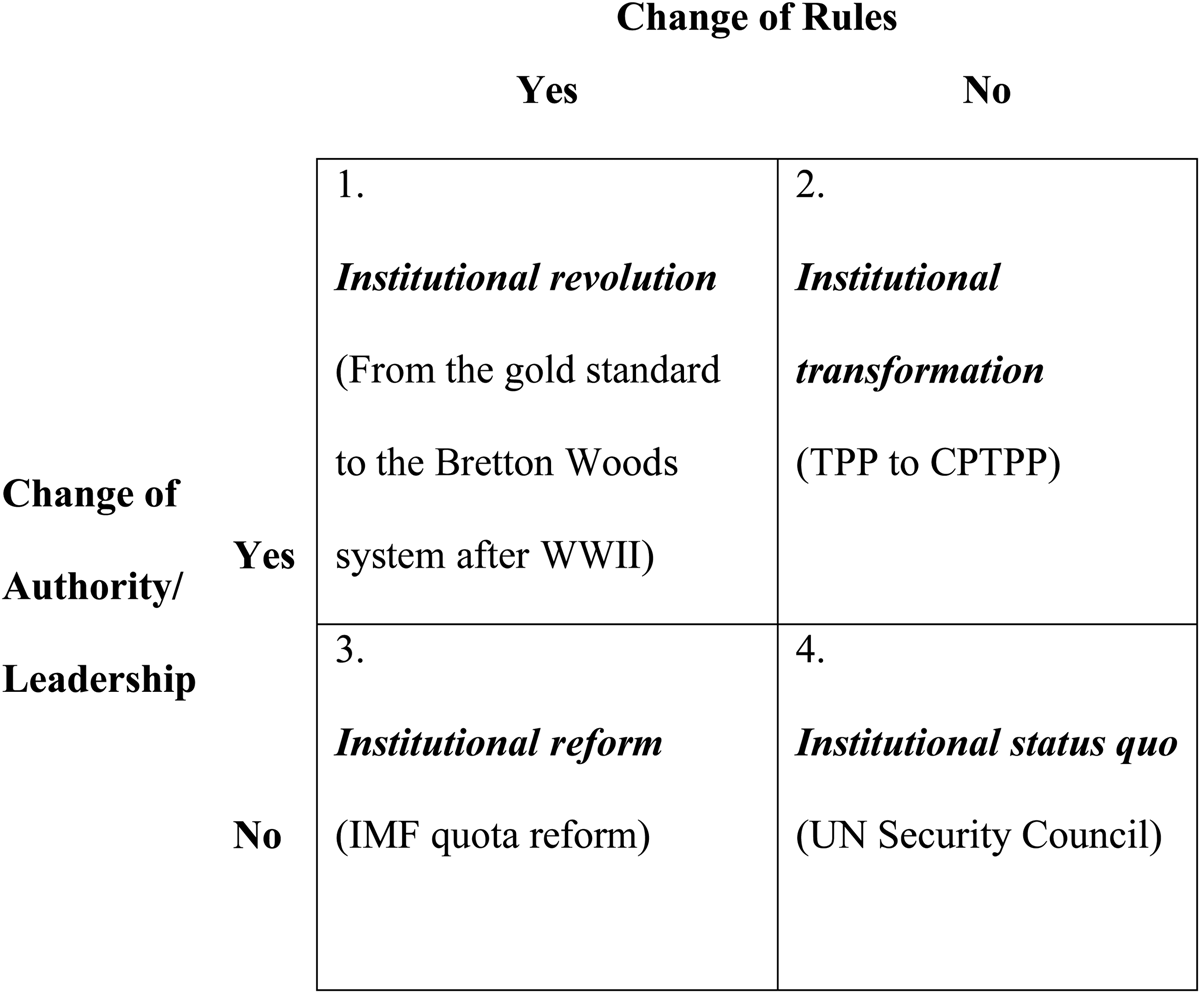

The more intensified that the institutional balancing among great powers becomes, the more institutional changes we will witness during the order transition. Depending on the outcome of their competition with regard to the authority and rules within institutions, we will see four ideal types of institutional changes, which are embedded in the international order transition. These four institutional changes might take place simultaneously or independently during the order transition. Figure 1 illustrates four possible outcomes of institutional balancing among states in any institution.

Figure 1. Four Scenarios of Institutional Changes

Cell 1 refers to a situation where both the authority and the rules of an existing institution are challenged and eventually changed. This will lead to an “institutional revolution,” which is the most profound type of change for existing international institutions. An example of such institutional revolution is the establishment of the Bretton Woods institutions to replace the gold standard: the United States became the new leading state after replacing the U.K.'s hegemony and the U.S. dollar supplanted gold as the new “rule of the game” in the global financial system. Although the establishment of the AIIB and the New Development Bank might have posed some challenges to both the authority and the rules of the global financial system, it is still too early to conclude that they represent an institutional revolution because both U.S. authority and the fundamental rules of the IMF and World Bank have been shaken but still hold, at least for now.

Cell 2 shows a situation where the leadership or authority of an institution is changed but the rules of the institution remain the same. This is called “institutional transformation,” which indicates the transformation of leadership from one state to another. One example of institutional transformation is the change from the TPP to the CPTPP (the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership). While the rules of the TPP and CPTPP are basically the same, the leadership has been transformed from the United States to Japan and Australia because President Trump withdrew from the TPP after he assumed office in early 2017. Institutional transformation will affect the influence and efficiency of the institutions because the new authority or leadership might or might not be able to take on challenges in the same way as the previous authority. This is why the departure of the United States has cast a shadow over the relevance of the CPTPP in the regional trading system.

Cell 3 indicates a situation in which an existing institution's leadership goes unchallenged, but the rules are modified. This will result in an “institutional reform.” It means that the leading states accommodate requests from other powers by changing the rules such that they will benefit these other powers’ interests more than they did previously. This is something of an internal adaptation of an institution; a successful renegotiation between the leading state and other members in the organization. One example of institutional reform is the quota reform of the IMF that increased the voting weight of developing countries. The rules of the IMF have been modified but its leadership remains intact.

Cell 4 represents an institutional status quo situation, in which both the authority and rules of an institution remain unchanged. This does not mean that there is no institutional balancing or struggle among states. As mentioned above, states engage in constant institutional balancing and competition with one another. However, institutional competition might not always lead to changes in the institution. One example of this is the push for UN Security Council (UNSC) reform, which has been advocated by non–P-5 countries for decades. However, so far, neither the authority nor the rules of the UNSC have been changed. It is a situation of institutional status quo.

It is worth emphasizing that the international order encompasses many institutions covering various issue areas. In other words, a state might challenge an institution working in one issue area, but support others working in different issue areas. For example, China is a beneficiary of global economic institutions, including the WTO. Therefore, it is not a surprise that Chinese president Xi Jinping has pledged to protect the global-trading system. However, in the area of human rights China falls outside of the norms of the current liberal order. It is thus not surprising that China has challenged international human rights institutions, such as Amnesty International.

In the same vein, as we have seen above, the United States has challenged some international institutions but supported others. While traditional international relations theorists might feel puzzled by U.S. “revisionist” behavior,Footnote 25 it is normal practice according to our institutional-balancing argument because it is rational for any state, including the hegemon, to challenge the authority and rules of institutions that do not fit its interests. Through different institutional-balancing strategies, the United States might retain, lose, or even regain its authority and leadership as institutional changes take place. Therefore, the decline of U.S. hegemony means neither the inevitable collapse of the international order nor the onset of the Kindleberger trap. Other states will take up the leadership of institutions, and the different types of institutional changes that take place will ensure the dynamics of international institutions.

Conclusion

International institutions, as a constitutive part of the international order, are of great importance to the coming international order transition. This transition will feature intense institutional balancing among states, as well as consequential institutional changes in the international order. States can choose either inclusive or exclusive institutional balancing, or both, to maximize their interests and power during the period of international order transition.

Through institutional balancing, states compete for leadership authority and the ability to write or rewrite the rules of institutions. Depending on how the authority and rules are challenged, we will witness one or more of four types of institutional change: institutional revolution, institutional transformation, institutional reform, and institutional status quo.Footnote 26 The dynamics of institutional changes are largely shaped by the negotiation and bargaining between ruling states and other rising powers. Although institutional competition in the form of institutional balancing can be severe and even harmful to the global economy (and the economies of individual states) and for regional and international stability, even extreme levels of institutional balancing will be much less destructive than military-based balancing among states. More importantly, institutional competition and consequential institutional changes are two remedies to keep international institutions dynamic and alive so that the world will not fall into the Kindleberger trap after the decline of U.S. hegemony.

In addition, institutional balancing can also alleviate the severity of military-based balancing. For example, the arms control treaties between the United States and the Soviet Union played an important stabilizing role in keeping the U.S.-Soviet antagonism “cold” during the Cold War era. For this reason, it was worrisome to the world when Trump withdrew the United States from the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty (INF Treaty) with Russia in August 2019 and announced a similar decision regarding the Treaty on Open Skies in May 2020. These actions have also intensified concerns about the future of the nuclear arms control institution New START (Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty) between the United States and Russia. It remains an ethical imperative for international institutions to play a significant mediating role in managing military competition between the hegemon and the rising powers, especially between the United States and China, in order to avoid the existential threat of a nuclear war.

The decline of U.S. hegemony will not push the whole world into the Kindleberger trap. However, a real danger is a loss of confidence in international institutions. The existing international organizations have failed to rise to the occasion in fighting the COVID-19 pandemic. The WHO has functioned as a “clearinghouse” to offer the most authoritative information regarding COVID-19, but it has neither the power to extract information nor the power to enforce regulations in any country. The UNSC remained silent regarding the struggle to manage the pandemic until July 1, 2020, when it finally adopted a resolution to support the secretary-general's appeal for united efforts to fight COVID-19 in the most vulnerable countries. The belated responses from the UNSC might reflect the deepening divide inside the institution itself. The G-20 convened an unprecedented virtual meeting on the pandemic on March 26, 2020. However, its statement was declaratory in nature, offering no roadmap for action.

The COVID-19 pandemic has pushed the world toward the edge of a cliff with the Kindleberger trap because international institutions have lost their ethical appeal and practical competence in dealing with the pandemic. Moreover, we have witnessed the rampant spread of nationalism and xenophobia in many countries. However, no country can be immune from COVID-19 and no country can fight the virus alone. Therefore, multilateralism is the only cure for this global pandemic as well as the only way for the world to avoid falling into the Kindleberger trap in the future. As French president Emmanuel Macron rightly points out, multilateralism should not be weakened by COVID-19. Instead, the world leaders should “think the unthinkable” to strengthen multilateralism in the postpandemic world.Footnote 27

What states, especially the United States and China, should do is reembrace and reinvigorate the role of multilateralism in world politics. States will still compete for power and influence through international institutions. However, the dynamics of institutional balancing and consequential institutional changes in the context of U.S.-China competition should not deprive international society of the public goods and normative values of international institutions. The complexities and dynamic changes of international institutions will contribute to a gradual and incremental transition in the international order.

If the United States and China, along with other great powers, can refrain from engaging in military competition and conflict with one another, institutional balancing among states in different issue areas might lead to different types of institutional changes, which in turn will feature a more peaceful transition of the international order. The future international order should not be led by a single country but by different leadership groups through various institutions in diverse issue areas. If so, Nye's worry about the Kindleberger trap may not be warranted because the world after U.S. hegemony will become more institutionalized, interdependent, and globalized.