Introduction

Human trafficking is a serious crime and human rights violation that often involves extreme forms of abuse and deprivation. Defined as the recruitment and movement of individuals – most often by force, coercion or deception – for the purposes of exploitation (United Nations, 2000), it is estimated to affect the lives of over 20 million people worldwide (International Labour Organisation, 2012). Individuals are trafficked for sexual exploitation but also for domestic servitude and forced labour in a range of industries, including factory work, agriculture, construction, commercial fishing and street begging. The violence, abusive living conditions and restrictions on movement commonly associated with trafficking pose serious risks to trafficked people's health, especially mental health. Although evidence on the psychological sequelae of trafficking is limited, studies suggest a high prevalence of depression, anxiety and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) among men and women in contact with post-trafficking support organisations (Turner-Moss et al. Reference Turner-Moss, Zimmerman, Howard and Oram2014; Kiss et al. Reference Kiss, Pocock, Naisanguansri, Suos, Dickson, Thuy, Koehler, Sirisup, Pongrungsee, Nguyen, Borland, Dhavan and Zimmerman2015).

A systematic review conducted in 2012 identified 19 studies reporting on the health risks and problems experienced by women and girls trafficked for sexual exploitation and found a high prevalence of physical and sexual abuse; depression; PTSD; physical symptoms such as headache, back pain and memory loss; and sexually transmitted infection (STI) (Oram et al. Reference Oram, Stockl, Busza, Howard and Zimmerman2012b ). The review also highlighted the near-complete absence of evidence at that time on the health of trafficked men and of individuals trafficked for labour exploitation. However, 17 of the 19 included studies were published within the 5 years prior to the review, suggesting that this is a new and quickly developing research area. Recognising this rapid emergence in studies on health and trafficking, this review was conducted to provide a fuller and up-to-date synthesis of the evidence. Specifically, the systematic review aimed to establish:

-

(a) The prevalence of violence and other health risks experienced by trafficked people;

-

(b) The prevalence and types of physical, mental and sexual health problems among trafficked people;

-

(c) Risk factors associated with physical, mental and sexual health problems among trafficked people.

Methods

The review followed PRISMA guidelines (Moher et al. Reference Moher, Liberati, Tetzlaff and Altman2009), and is registered with PROSPERO (registration CRD42015023564 (http://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero)). The PRISMA statement and protocol for this review are available as Supplementary information.

Study selection criteria

Studies were eligible for inclusion if they: (a) included male or female adults or children who self-identified or were believed by the research team to have been trafficked; (b) measured the prevalence and/or the risk of physical, psychological or sexual violence whilst trafficked, and/or reported on the prevalence or risk of physical, mental, or sexual and reproductive health or disorder; and (c) presented the results of published peer-reviewed or doctoral research based on the following study designs: cross-sectional survey; case–control study; cohort study; case series analysis; experimental study with baseline measures for the outcomes of interest; or secondary analysis of organisational records. If studies included trafficked people as a subset of a broader sample, data on trafficked people must have been reported separately. No restrictions were placed on language, country setting or the method of measuring health risks and outcomes. Qualitative studies, editorials, opinion pieces and reviews were excluded. If the same data were reported by multiple papers, the paper with the largest N relevant to the review objectives was included.

Search strategy

We undertook electronic searches of ten databases indexing peer-reviewed academic literature and five databases and websites indexing theses and dissertations (including MEDLINE, EMBASE and PsycINFO – see Supplementary information for full list). All search terms from Oram et al.'s systematic review were included, plus additional terms for trafficking and specific mental disorders (see Supplementary information). The date limits for searches were 1 January 2011 (the upper limit of the original review) until 17 April 2015. Electronic searches were supplemented by reference list screening and citation tracking using Web of Science and Google Scholar. Twenty-eight experts were asked to nominate additional papers that may have been eligible for inclusion; responses were received from eleven.

Data extraction and quality appraisal

Two reviewers (LO and SH) independently screened titles and abstracts; disagreements were resolved by consensus or by reference to a third reviewer (SO). If it was unclear whether a reference met the inclusion criteria it was retained for full text screening. Two reviewers (LO and SH) independently assessed the full text of potentially eligible studies; disagreements were again resolved by consensus or with the assistance of a third reviewer (SO). If studies collected data on prevalence or risk of violence or health outcomes among trafficked people but did not report it, information was requested from the study authors.

One reviewer (LO) extracted data on study design, sample characteristics, the definition and method of assessing human trafficking, outcome measures and outcomes of interest into standardised electronic forms. Where possible, outcome measures were extracted separately by gender, age and type of exploitation. Data were extracted by a second reviewer (SH) from a random sample of 10% of papers: there were no discrepancies between reviewers and therefore no further dual extraction was undertaken.

The quality of included studies was independently appraised by two reviewers (LO and SH) using criteria adapted from the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP, 2014). The quality appraisal checklist included 15 items assessing study quality, including risk of selection and measurement bias (see Supplementary material). Each item is rated with a grade between 0 and 2, giving a maximum total score of 30 and maximum subscores for risk of selection and measurement bias of 6 and 6, respectively. Reviewers compared scores and any discrepancies in component ratings were discussed and resolved. Studies scoring lower than 50% on questions relating to selection bias or measurement bias were judged to have a relevant risk of bias.

Data analysis

Prevalence estimates and odds ratios (ORs) were calculated, disaggregated by gender and type of exploitation where possible. Where multiple papers reported results from the same study, only the most definitive results were included for each outcome of interest. Pooled prevalence estimates and ORs (with corresponding 95% confidence intervals) were calculated when comparable data were available from validated instruments for three or more studies. All pooled estimates used random effects meta-analysis. Heterogeneity was estimated using the I 2 statistic, which describes the percentage of variation across studies that is due to heterogeneity rather than chance (Higgins & Thompson, Reference Higgins and Thompson2002).

Results

The study selection process is described in Fig. 1. Thirty-seven papers were ultimately included in the review, reporting on 31 studies and 15 085 participants. Two of the included papers were published in languages other than English.

Fig. 1. PRISMA Flow Diagram for systematic literature review update (January 2011 to >17 April 2015).

Key features of included studies

Key characteristics of included studies are summarised in Table 1. Eighteen of the 31 included studies were conducted in South and Southeast Asia, nine in Europe, three in Latin America and one in North America. Twenty-five studies were conducted with women and girls, predominantly in situations of sexual exploitation (22 of 25). Six studies reported on the experiences of trafficked men and children. Half of the studies (16/31) were conducted with participants recruited from post-trafficking support services; 14 were carried out in alternative settings with women in the sex industry; 11 also included sex workers not identified by any official or non-governmental agency as trafficked (‘non-trafficked’). Four studies were conducted in clinical settings, and one study reported findings from a community sample. Quality appraisal indicated that over half of the included studies had a relevant risk of bias: 18 of the 31 scored lower than 50% on criteria relating to selection bias and 12 on criteria relating to measurement bias.

Table 1. Characteristics of included studies (31 studies, reported by 37 papers)

* The quality appraisal instrument (see Appendix 3) has 15 questions. Papers received a score of between 0 and 2 for each question, giving a maximum total score of 30. Scores for two sub-domains – the quality of studies’ sampling strategies and the quality of measurements – are presented alongside the total quality score. Scores for other sub-domains are not shown.

Violence

Eighteen studies reported on trafficked people's experiences of violence (Table 2). Eight studies compared experiences of violence for women trafficked for sexual exploitation to non-trafficked women working in the sex industry. Seven studies found significantly higher odds of violence among trafficked v. non-trafficked sex workers (Sarkar et al. Reference Sarkar, Bal, Mukherjee, Chakraborty, Saha, Ghosh and Parsons2008; Decker et al. Reference Decker, McCauley, Phuengsamran, Janyam and Silverman2011; Gupta et al. Reference Gupta, Reed, Kershaw and Blankenship2011; Silverman et al. Reference Silverman, Raj, Cheng, Decker, Coleman, Bridden, Pardeshi, Saggurti and Samet2011; George & Sabarwal, Reference George and Sabarwal2013; Wirth et al. Reference Wirth, Tchetgen Tchetgen, Silverman and Murray2013; Silverman et al. Reference Silverman, Saggurti, Cheng, Decker, Coleman, Bridden, Pardeshi, Dasgupta, Samet and Raj2014). According to three studies, violence at entry or in the first months after commencing sex work was higher among trafficked sex workers than non-trafficked sex workers; findings were less consistent with regards to violence at other time points. Findings were also inconsistent with regards to whether trafficked women who commenced sex work as minors were at higher risk of experiencing violence (Decker et al. Reference Decker, Mack, Barrows and Silverman2009; Gupta et al. Reference Gupta, Reed, Kershaw and Blankenship2011; Silverman et al. Reference Silverman, Raj, Cheng, Decker, Coleman, Bridden, Pardeshi, Saggurti and Samet2011; Wirth et al. Reference Wirth, Tchetgen Tchetgen, Silverman and Murray2013).

Table 2. Prevalence and risk of violence whilst trafficked (n = 18)

* Not clear from existing data whether this was in the context of trafficking or prior to trafficking experience.

† Control group are children who experienced sexual abuse/sexual assault (CSA).

Six studies reported on violence experienced by trafficked people in contact with post-trafficking support services (Zimmerman et al. Reference Zimmerman, Yun, Shvab, Watts, Trappolin, Treppete, Bimbi, Adams, Jiraporn, Beci, Albrecht, Bindel and Regan2003; Di Tommasso et al. Reference Di Tommaso, Shima, Strom and Bettio2009; McCauley et al. Reference McCauley, Decker and Silverman2010; Turner-Moss et al. Reference Turner-Moss, Zimmerman, Howard and Oram2014; Kiss et al. Reference Kiss, Pocock, Naisanguansri, Suos, Dickson, Thuy, Koehler, Sirisup, Pongrungsee, Nguyen, Borland, Dhavan and Zimmerman2015; Le, Reference Le2014). Women and girls who had been trafficked for sexual exploitation described high levels of physical and sexual violence, which ranged from 33% in a Cambodian case-file review (McCauley et al. Reference McCauley, Decker and Silverman2010) to 90% in a multi-country European survey (Zimmerman et al. Reference Zimmerman, Hossain, Yun, Gajdadziev, Guzun, Tchomaroa, Ciarrocchi, Johansson, Kefurtova, Scodanibbio, Motus, Roche, Morison and Watts2008). Two studies published since the last systematic review provide data on the experiences of violence by trafficked men and children and people who had been trafficked for labour exploitation. A large multi-country survey conducted in post-trafficking services in the Greater Mekong Subregion of Southeast Asia reported that the prevalence of physical violence experienced by men, women and children was 49, 41 and 24%, respectively (Kiss et al. Reference Kiss, Pocock, Naisanguansri, Suos, Dickson, Thuy, Koehler, Sirisup, Pongrungsee, Nguyen, Borland, Dhavan and Zimmerman2015) and sexual violence 1, 44 and 22%, respectively. In the UK analyses of organisational records reported that approximately half of the seven women and almost one-third of the 23 men trafficked for labour exploitation reported physical violence while trafficked (Turner-Moss et al. Reference Turner-Moss, Zimmerman, Howard and Oram2014).

Similarly, a high prevalence of violence was reported by studies that sampled trafficked people in contact with clinical services, including sexual and mental health services and emergency departments (Dal Conte & Di Perri, Reference Dal Conte and Di Perri2011; Oram et al. Reference Oram, Khondoker, Abas, Broadbent and Howard2015; Varma et al. Reference Varma, Gillespie, McCracken and Greenbaum2015). Sexual violence was reported by one-fifth of women in contact with sexual health services in Italy and documented for 73% women and 51% of children in contact with mental health services (Dal Conte & Di Perri, Reference Dal Conte and Di Perri2011; Oram et al. Reference Oram, Khondoker, Abas, Broadbent and Howard2015). Physical violence was documented for 40% of children accessing emergency departments, and 57, 72 and 60% of women, men and children in contact with mental health services (Dal Conte & Di Perri, Reference Dal Conte and Di Perri2011; Oram et al. Reference Oram, Khondoker, Abas, Broadbent and Howard2015). However, these figures may capture violence that took place before, during or after the trafficking situation.

Mental health

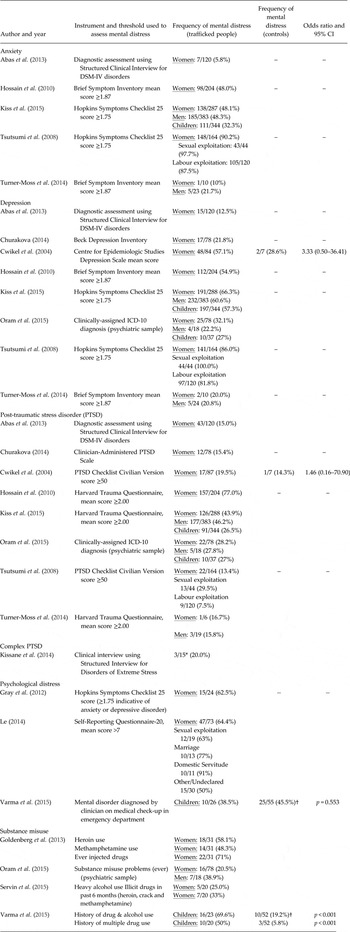

Fifteen studies reported on the mental health of trafficked people: nine on diagnosed or probable depression, anxiety, or PTSD; one on complex PTSD, and three on clinically significant symptoms of psychological distress (Table 3).

Table 3. Prevalence and risk of mental distress among people who have been trafficked (n = 15)

* Mixed sample, 86.7% female.

† Control group are children who experienced sexual abuse/sexual assault (CSA).

Trafficked women

Two studies used diagnostic instruments to assess mental disorders (Abas et al. Reference Abas, Ostrovschi, Prince, Gorceag, Trigub and Oram2013; Kissane et al. Reference Kissane, Szymanski, Upthegrove and Katona2014) and two reported on clinical diagnoses that were assigned by mental health professionals (Oram et al. Reference Oram, Khondoker, Abas, Broadbent and Howard2015; Varma et al. Reference Varma, Gillespie, McCracken and Greenbaum2015). Abas et al. (Reference Abas, Ostrovschi, Prince, Gorceag, Trigub and Oram2013), using the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM Disorders (SCID) to diagnose mental disorder among women in contact with post-trafficking services in Moldova, reported that 55% of the sample met diagnostic criteria for mental disorder at an average of 6 months after return, including PTSD (36%), depression (13%) and anxiety disorder (6%). Oram et al. (Reference Oram, Khondoker, Abas, Broadbent and Howard2015), reporting on a sample of 78 trafficked women in contact with secondary mental health services in England, reported that the most prevalent diagnoses were depression (32%), PTSD and severe stress and adjustment disorders (28%), and schizophrenia and related disorders (9%).

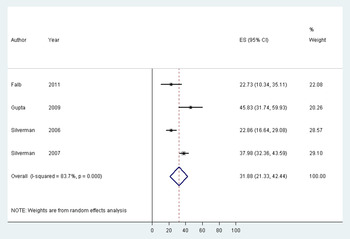

The remaining eight papers used screening instruments to assess probable disorder and varied considerably in their estimates (see Table 6). The pooled prevalence estimates were 50% for symptoms of anxiety (95% CI 21.9–78.2%), 52% for depression (95% CI 33.9–70.8%) and 32% for PTSD (95% CI 8.3–54.9%), but these estimates were associated with high heterogeneity (I 2 = 97.0–98.5%) (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2. Forest plot displaying DerSimonian and Laird weighted random-effect pooled prevalence estimates for prevalence of self-reported symptoms of anxiety, depression and PTSD among trafficked women.

Trafficked men

Three studies reported on the mental health of trafficked men. Two used screening instruments and reported high levels of symptoms of anxiety (21.7–48.3%), depression (20.8–60.6%) and PTSD (15.8–46.2%) (Turner-Moss et al. Reference Turner-Moss, Zimmerman, Howard and Oram2014; Kiss et al. Reference Kiss, Pocock, Naisanguansri, Suos, Dickson, Thuy, Koehler, Sirisup, Pongrungsee, Nguyen, Borland, Dhavan and Zimmerman2015). Oram et al. (Reference Oram, Khondoker, Abas, Broadbent and Howard2015), reporting on a sample of 19 trafficked men in contact with secondary mental health services, indicated the most prevalent diagnoses were depression (21%), PTSD and severe stress and adjustment disorders (26%) and schizophrenia and related psychoses (37%).

Trafficked children

High levels of mental health problems were similarly reported for trafficked children. A study of trafficked children accessing emergency medical services in the USA identified 38.5% had a history of mental disorder, although it is unclear what proportion of this preceded v. followed the trafficking experience (Varma et al. Reference Varma, Gillespie, McCracken and Greenbaum2015). A survey conducted in South East Asia using screening instruments found 32% had probable anxiety, 57% probable depression and 26% probable PTSD. Among 35 trafficked children in contact with secondary mental health services in England, the most common diagnoses were PTSD, severe stress and adjustment disorders (27%) and affective disorders (27%). Other diagnoses included anxiety, conduct disorder and schizophrenia (Oram et al. Reference Oram, Khondoker, Abas, Broadbent and Howard2015).

Risk factors for mental health problems

Table 4 describes risk factors for poor mental health among trafficked people that included factors occurring prior to, during, and after trafficking: childhood sexual abuse; sexual and physical violence while trafficked, poor living and working conditions, restrictions on movement and longer duration of exploitation; and unmet social needs after escaping exploitation (Hossain et al. Reference Hossain, Zimmerman, Abas, Light and Watts2010; Abas et al. Reference Abas, Ostrovschi, Prince, Gorceag, Trigub and Oram2013; Kiss et al. Reference Kiss, Pocock, Naisanguansri, Suos, Dickson, Thuy, Koehler, Sirisup, Pongrungsee, Nguyen, Borland, Dhavan and Zimmerman2015). Le (Reference Le2014) reported that the total severity of violence, as indicated by a composite score of physical, sexual, emotional and labour abuse and forced alcohol use, was predictive of the level of psychological distress among women in contact with post-trafficking services in Vietnam. Higher levels of post-trafficking support were suggested to be associated with a reduced risk of mental disorder (AOR = 0.64, 95% CI 0.52–0.79; Abas et al. Reference Abas, Ostrovschi, Prince, Gorceag, Trigub and Oram2013).

Table 4. Risk factors for mental disorder among people who have been trafficked* (n = 4)

* A plus sign indicates a risk factor; a minus sign indicates that the factor had a protective effect; zero indicates it had no effect of either type; blank cells indicate the factor was not studied. The risk factors shown were examined for depression, anxiety, PTSD and psychological distress.

† This study reported a Total Abuse Score, which combined sexual, physical, emotional, labour abuse and forced alcohol use, to be predictive of psychological distress.

Substance abuse

Four studies collected data on substance misuse and indicated a high prevalence of drug and alcohol use among men, women and children that had been trafficked (Table 6). It is unclear whether participants were coerced to use drugs or alcohol, whilst trafficked (Le, Reference Le2014) or whether they were using substances as a coping strategy during or after escaping the trafficking situation.

Physical health

Data on the physical health of people who have been trafficked were drawn from six studies that collected data on the self-reported symptoms of survivors in contact with post-trafficking services (Table 5). Five were conducted with samples of women and girls trafficked for sexual exploitation; the most commonly reported physical health symptoms were headaches (60–83%), back pain (51–69%), stomach pain (53–61%), dental pain (58%), fatigue (81%) and dizziness (55–70%). Two studies reported on the physical health of trafficked men and children: a large multi-country survey in South East Asia and a small case series conducted in the UK (Turner-Moss et al. Reference Turner-Moss, Zimmerman, Howard and Oram2014; Kiss et al. Reference Kiss, Pocock, Naisanguansri, Suos, Dickson, Thuy, Koehler, Sirisup, Pongrungsee, Nguyen, Borland, Dhavan and Zimmerman2015). The prevalence of physical health symptoms was lower than has been reported for women trafficked for sexual exploitation, but the symptoms most frequently endorsed were similar, including headache, back pain, dental pain, fatigue and memory problems.

Table 5. Physical symptoms reported by people who have been trafficked (n = 6)

Sexual health

HIV

The prevalence of HIV infection was reported by eight studies: three with trafficked and non-trafficked sex workers and four with women accessing post-trafficking support (Table 6). Data from serological tests with trafficked and non-trafficked sex workers indicate an HIV prevalence in the trafficked women ranging from 6.5% from a study in Mexico (Goldenberg et al. Reference Goldenberg, Rangel, Staines, Vera, Lozada, Nguyen, Silverman and Strathdee2013) to 34.3% for a study in India (Wirth et al. Reference Wirth, Tchetgen Tchetgen, Silverman and Murray2013), with a pooled prevalence estimate of 18.1% and high heterogeneity (95% CI 0.5–35.7%, I 2 = 99.2%). Pooled estimates also suggested increased odds of HIV infection among trafficked v. non-trafficked sex workers (OR 1.96, 95% CI 1.11–3.47, I 2 = 54.5% Fig. 3). Wirth et al. (Reference Wirth, Tchetgen Tchetgen, Silverman and Murray2013) reported that odds of HIV infection among trafficked women with forced entry into prostitution was strongly associated with recent experiences of sexual violence (OR = 11.13, 95% CI 2.41–51.40). No association was found between age at entry into prostitution and HIV, and this was not modified by sexual violence (OR = 0.94, 95% CI 0.28–3.13).

Fig. 3. Forest plot displaying DerSimonian and Laird weighted random-effect pooled odds estimates for prevalence of HIV infection among trafficked women currently working in the sex industry in India and Mexico.

Table 6. Prevalence and risk of HIV infection among trafficked women (n = 8)

* Weighted percentage accounting for the probability of selection into the sample using the survey weights provided by the Integrated Behavioural and Biological Assessment.

† Estimated from a weighted marginal structural logistic regression model with district-specific weights constructed to simultaneously adjust for the unequal probability of selection induced by the survey's complex sampling strategy and the following confounders: literacy, whether the participant was widowed and/or deserted at the time of entry into the sex trade, use of sex work to support drug use and age at entry.

The review did not identify any further studies reporting on serological test results for HIV among women accessing post-trafficking support published since Oram et al.'s review. Estimates of the HIV prevalence range from 22.7 to 45.8% (Silverman et al. Reference Silverman, Decker, Gupta, Maheshwari, Patel and Raj2006, Reference Silverman, Decker, Gupta, Maheshwari, Willis and Raj2007; Gupta et al. Reference Gupta, Raj, Decker, Reed and Silverman2009; Falb et al. Reference Falb, McCauley, Decker, Sabarwal, Gupta and Silverman2011), with a pooled prevalence estimate of 31.9% (95% CI 21.3–42.2%) (Fig. 4). Two studies suggested that longer duration of exploitation may be associated with increased odds of infection (Silverman et al. Reference Silverman, Decker, Gupta, Maheshwari, Patel and Raj2006, Reference Silverman, Decker, Gupta, Maheshwari, Willis and Raj2007), and a potential association between odds of infection and the HIV prevalence in the geographical areas to or from which women had been trafficked. Inconsistent findings were reported with respect to age when trafficked. Only one study reported HIV prevalence among women trafficked for labour exploitation (Tsutsumi et al. Reference Tsutsumi, Izutsu, Poudyal, Kato and Marui2008). Their estimate of 0% was obtained by self-report and should be treated with caution, as 80% did not know their HIV status.

Fig. 4. Forest plot displaying DerSimonian and Laird weighted random-effect pooled prevalence estimates for prevalence of HIV infection among sex trafficked women currently in contact with post-trafficking services in India and Nepal.

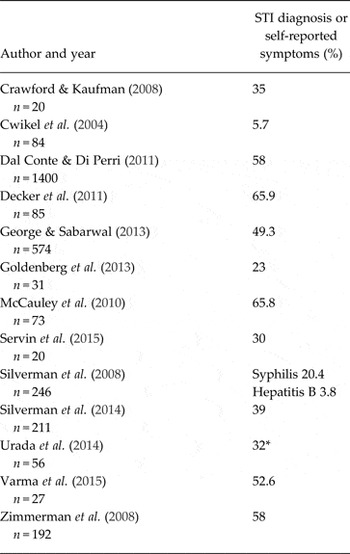

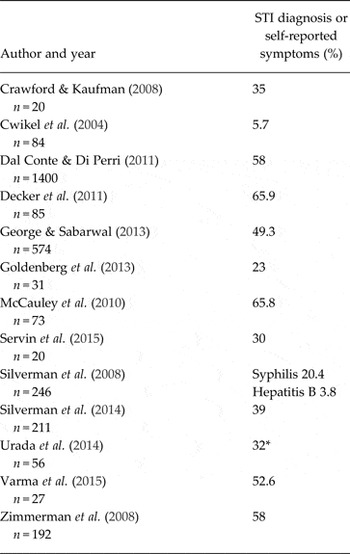

Sexually transmitted infections

Four studies reported on the results of serological tests for individual STIs, with substantial variation in prevalence (Table 7). A further nine studies reported the prevalence of self-reported symptoms of STI, which ranged from 6% in a study of sexually exploited women in Israel to 66% in a cross-sectional survey of trafficked sex workers in Thailand. Five of these nine reported the odds of self-reported STI symptoms among trafficked v. non-trafficked sex workers; none reported a significant difference (Cwikel et al. Reference Cwikel, Chudakov, Paikin, Agmon and Belmaker2004; Decker et al. Reference Decker, McCauley, Phuengsamran, Janyam and Silverman2011; George & Sabarwal, Reference George and Sabarwal2013; Goldenberg et al. Reference Goldenberg, Rangel, Staines, Vera, Lozada, Nguyen, Silverman and Strathdee2013, Silverman et al. Reference Silverman, Saggurti, Cheng, Decker, Coleman, Bridden, Pardeshi, Dasgupta, Samet and Raj2014).

Table 7. Sexually transmitted infections amongst women trafficked for sexual exploitation (n = 13)

* Last 6 months.

Discussion

Key findings

This review highlights the high prevalence of mental, physical and sexual health problems among trafficked people who were exploited in various settings and industries. The review also draws attention to the high levels of physical and sexual violence experienced by trafficked people, including by trafficked children. This review re-emphasises that trafficked men and trafficked children and people trafficked for labour exploitation are underrepresented in research on health and human trafficking. However, emerging evidence indicates a high burden of mental and physical health problems among these groups.

Recent studies have begun to investigate risk factors for poor mental and sexual health outcomes for trafficked people. Risk of mental disorder appears to be increased by multiple factors, including violence prior to and during trafficking, restricted freedom and poor living and working conditions while trafficked, and social support and unmet social needs following escape. These findings are consistent with the broader literature on trauma and risk of adverse reactions, particularly PTSD, which suggests the cumulative risk of multiple traumatic events and the importance of post-trauma social support (Brewin et al. Reference Brewin, Andrews and Valentine2000; Ozer et al. Reference Ozer, Best, Lipsey and Weiss2003). It is also noteworthy that the physical pain or discomfort most frequently endorsed by trafficked people, including headache, stomach pain and memory problems, are non-specific and could be related to either physical or psychological problems. Mental health problems appear to be enduring, with studies reporting a high prevalence of diagnosed disorder several months post-trafficking (Abas et al. Reference Abas, Ostrovschi, Prince, Gorceag, Trigub and Oram2013) and a slower decline in symptoms than for physical health problems (Zimmerman et al. Reference Zimmerman, Hossain, Yun, Roche, Morison and Watts2006). Further research should explore the pathways through which trafficking impacts mental health to inform interventions to promote recovery. Similarly, research is urgently needed to identify and test the effectiveness of psychological interventions to support the mental health of trafficked populations.

Violence may also increase risk of HIV infection (Stockman et al. Reference Stockman, Lucea and Campbell2013; Wirth et al. Reference Wirth, Tchetgen Tchetgen, Silverman and Murray2013). Studies suggest that women and girls trafficked for sexual exploitation are at increased risk of physical and particularly sexual violence as compared to non-trafficked sex workers at initial entry into sex work (Sarkar et al. Reference Sarkar, Bal, Mukherjee, Chakraborty, Saha, Ghosh and Parsons2008; Decker et al. Reference Decker, McCauley, Phuengsamran, Janyam and Silverman2011; Gupta et al. Reference Gupta, Reed, Kershaw and Blankenship2011; Silverman et al. Reference Silverman, Raj, Cheng, Decker, Coleman, Bridden, Pardeshi, Saggurti and Samet2011, Reference Silverman, Saggurti, Cheng, Decker, Coleman, Bridden, Pardeshi, Dasgupta, Samet and Raj2014; George & Sabarwal, Reference George and Sabarwal2013; Wirth et al. Reference Wirth, Tchetgen Tchetgen, Silverman and Murray2013). These studies begin to address calls made in the previous review for research to compare health risks among trafficked and non-trafficked sex workers. However, this review highlights the scarcity of current evidence on the health of what is now recognised as a very large global population of abused and exploited persons. To strengthen post-trafficking support, robust findings are still needed on differences in mental and physical health outcomes and other types of health risks between men, women and children and to compare the risks and health outcomes of people identified as trafficked and those working in the same industries who were not identified as trafficked, especially individuals working in sectors known for extreme forms of exploitation.

Strengths and limitations of the review

The review used a comprehensive search strategy, independent screening and quality appraisal of studies, and adhered to PRISMA reporting guidelines. Doctoral theses were included, as were studies published in languages other than English. However, methodological problems at the level of the primary studies also limit the conclusions that can be drawn from this review. Most studies used non-probability sampling and did not provide information on the representativeness of their samples, limiting generalisability. Half of the included studies were conducted with people recruited from post-trafficking support services, and it is unlikely their experiences represent those of all trafficked people, many of whom probably do not in contact with support services. It is unclear whether those accessing support represent more severe cases of abuse and have more extreme health needs, or conversely, if they represent a sample that is healthier and has greater access to resources, and is therefore able to contact services. Similarly, it is unclear how trafficking identification criteria might have differed by location and/or over time. Likewise, studies with sex industry samples may under-represent those experiencing the highest levels of abuse and restrictions of movement, which would likely limit their ability to participate in the study. The four studies with clinical populations likely overestimate the population-level prevalence of violence and physical, sexual and mental health problems. None of the studies were able to capture accurately people's psychological history prior to trafficking and the possible influence on current symptoms. In the context of a limited number of studies, however, it is not possible to estimate the direction or scale of these potential selection biases with certainty. Estimates of pooled prevalence and risk of HIV amongst women trafficked for sexual exploitation are drawn from a very small number of studies from South and Southeast Asia and Mexico, and were associated with high levels of heterogeneity. It is uncertain to what extent these findings can be generalised to other populations as they likely to be related to local prevalence rates and dynamics of HIV infection.

The comparability of studies and reliability of findings was further limited by diversity of methods and tools used to assess experiences of violence and various health outcomes. Only two studies used diagnostic interviews to assess mental disorder and none used unmodified validated instruments to assess violence and physical health outcomes amongst trafficked people. There is a critical need to develop validated instruments for use with trafficked populations to ensure future studies can produce more rigorous, valid and comparable data.

Definitional differences in trafficking exposure were also apparent in the primary studies. Ten studies categorised women as having been trafficked if they reported being younger than 18 years upon entering the sex industry, regardless of the means of their recruitment. Other studies explicitly operationalised trafficking if the study authors determined that force or coercion was present. Studies that analysed the experiences of violence and health outcomes separately for women who entered the sex industry aged younger than 18 and for women who had been forced or coerced into sex work found differing prevalence of violence and health problems associated with each, suggesting that these definitional differences may result in significant variation in outcomes of interest (Gupta et al. Reference Gupta, Reed, Kershaw and Blankenship2011; Wirth et al. Reference Wirth, Tchetgen Tchetgen, Silverman and Murray2013; Silverman et al. Reference Silverman, Saggurti, Cheng, Decker, Coleman, Bridden, Pardeshi, Dasgupta, Samet and Raj2014). Fifteen of the 37 studies reported on trafficked people in contact with post-trafficking support services in their countries of origin. However, these services varied greatly, from small grassroots non-governmental organisations to official service providers such as those provided by the International Organization for Migration. Support eligibility criteria varied both by type of exploitation, with some services only supporting survivors of sex trafficking, some only for women or children or men, some servings for a broader range of survivors, and yet others setting different thresholds for service access services and operationalising legal definitions of trafficking in their own terms. These differences limit the comparability of findings from within the post-trafficking support service samples.

Conclusion

Research on the health consequences of trafficking is an emerging area of study that is fundamental to developing well-informed mechanisms of identifying, referring and caring for this population These findings, even with their limitations, clearly indicate that human trafficking is a severe form of abuse that occurs in many corners of the globe and which has serious and often long-lasting health problems, including enduring mental distress. The next critical step to respond to the most pressing health needs of trafficked people is to investigate potentially effective psychological interventions to help this highly vulnerable group move beyond their real-life nightmares.

Acknowledgements

We thank the experts in this area who recommended studies for potential inclusion in the review. We are also grateful to Glori Gray, Michele Decker, Lawrence Szymanski and Julie Cwikel for providing supplementary data. We would like to thank Sanghoon Lee and Vasily Chernov for their assistance in translating articles published in Korean and Russian.

Financial Support

SH, LMH, CZ and SO are supported by the Department of Health Policy Research Programme (115/0006). Louise Howard is also supported by an NIHR Research Professorship (NIHR-RP-R3-12-011) and by the NIHR South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust Biomedical Research Centre-Mental Health. This report is independent research commissioned and funded by the Department of Health Policy Research Programme (Optimising Identification, Referral and Care of Trafficked People within the NHS 115/0006). The views expressed in this publication are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the Department of Health. The funder had no role in the design or conduct of the study, collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data or writing of the report. The corresponding author had full access to all the data in the study and had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

Conflicts of Interest

SO is the lead author on two of the papers included in this review and co-author on further two. CZ is the lead author on one paper included in this review and co-author on a further three. LMH, LO and SH declare no conflicts of interest.

Ethical Standards

Ethical approval was not required for this work.

Supplementary Materials

The supplementary materials referred to in this article can be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S2045796016000135