Introduction

Consumer voices are often overlooked or ignored in mental health services development and delivery (Buck & Alexander, Reference Buck and Alexander2006; Gee et al. Reference Gee, McGarty and Banfield2016). Understanding consumer expectations is relevant to recovery-oriented rehabilitation given the emphasis on working with consumers’ goals and priorities (Australian Health Ministers Advisory Council, 2013; Moran et al. Reference Moran, Baruch, Azaiza and Lachman2016), and challenges associated with engaging people affected by severe mental illness such as schizophrenia (Meaden et al. Reference Meaden, Hacker, de Villiers, Carbourne and Paget2012; Bright et al. Reference Bright, Kayes, Worrall and McPherson2015; Cook et al. Reference Cook, Mundy, Killaspy, Taylor, Freeman, Craig and King2016). Disengagement has been described as a ‘central challenge’ to actualising recovery-oriented care (Moran et al. Reference Moran, Baruch, Azaiza and Lachman2016).

There has been limited exploration of consumer perspectives on the issue of engagement with mental health services. Smith et al. used qualitative interviews to understand service disengagement by people with serious mental illness in the United States of America (USA) (Smith et al. Reference Smith, Easter, Pollock, Pope and Wisdom2013). Consumers discussed the lack of relevance of services to their needs, distrust of service providers and rejection of the ‘illness model’ (Smith et al. Reference Smith, Easter, Pollock, Pope and Wisdom2013). In contrast, service providers emphasised limitations in consumer insight, stigma, language and cultural barriers. Similar findings emerged in a recent study completed in Israel exploring perspectives of people with severe mental illness who had rejected rehabilitation support (Moran et al. Reference Moran, Baruch, Azaiza and Lachman2016). Factors contributing to disengagement were negative attitudes and limited knowledge about rehabilitation, lack of involvement and incongruence between recommendations and their goals. Another qualitative study in the USA explored the factors impacting engagement in a residential housing programme for people with severe mental illness and homelessness (Padgett et al. Reference Padgett, Henwood, Abrams and Davis2008) and emphasised both person-centred and system-related factors. System-related factors enhancing engagement were acts of kindness, access to housing and pleasant surroundings. Negative systemic influences on engagement were lack of one-to-one staff interaction and emphasis on rules and restrictions. Understanding consumer expectations can facilitate the adaptation of existing services to deliver more consumer-centred care (Csipke et al. Reference Csipke, Papoulias, Vitoratou, Williams, Rose and Wykes2016). Achieving a better fit between what consumers want and what services provide may positively impact engagement and outcomes (Padgett et al. Reference Padgett, Henwood, Abrams and Davis2008; Dudzik, Reference Dudzik2011; Holding et al. Reference Holding, Gregg and Haddock2016).

There has been limited research exploring consumer expectations and experiences of care in residential rehabilitation (McKenna, Reference McKenna2017; Parker et al. Reference Parker, Siskind and Meurk2017b), and in sub-acute residential services generally (Thomas & Rickwood, Reference Thomas and Rickwood2016). Qualitative research undertaken in these settings has focused on experience rather than expectations and prioritised staff perspectives (Parker et al. Reference Parker, Siskind and Meurk2017b). The present study aims to fill this gap by exploring the expectations consumers hold when they commence at a residential rehabilitation service for people affected by severe mental illness in Australia called a Community Care Unit (CCU) (Parker et al. Reference Parker, Dark, Newman, Korman, Meurk, Siskind and Harris2016a).

Methods

Study protocol

This study considers one component of a longitudinal mixed methods comparative evaluation of the equivalence of an integrated peer support and clinical staffing model for residential mental health rehabilitation. The published protocol provides extensive details about the study context, researchers, qualitative methods and interview schedule (Parker et al. Reference Parker, Dark, Newman, Korman, Meurk, Siskind and Harris2016a).

Study context

CCUs support people with severe and persisting mental illness to achieve personal recovery goals over a 6–24 month timeframe (Queensland Health, 2015); most consumers will have a diagnosis of schizophrenia or a related psychotic disorder (Meehan et al. Reference Meehan, Stedman, Parker, Curtis and Jones2017). Consumers reside in self-contained, independent living units in an apartment complex with 24 h support from a multidisciplinary team assisting them with living skills development and community re-integration. The operational framework designates the service as recovery-oriented due to its embracing the possibility of recovery, and its focus on strengths and maximising self-determination (Parker et al. Reference Parker, Dark, Newman, Korman, Meurk, Siskind and Harris2016a).

This study was undertaken at three CCUs located within a large public mental health service in Brisbane, Australia. Two sites were in outer-suburban areas, and the other was in a central suburb. The central site opened in 2011 and operates a traditional clinical staffing model where nursing staff predominate. The outer-suburban sites opened between December 2014 and January 2015 and are trialling a novel integrated staffing model where most staff are employed as peer support workers based on their lived experience of mental illness (Parker et al. Reference Parker, Dark, Vilic, McCann, O'Sullivan, Doyle and Lendich2016b). The integrated staffing model aims to achieve synergistic benefits for consumers engaging with the rehabilitation service through the horizontal collaboration of peer and clinical specialists within a single team. Despite differences in staffing configuration, all three sites operate under the same model of service (see Table 1) and provide similar rehabilitation support and psychosocial interventions. Few consumers entering these services are expected to have had a previous experience of residential rehabilitation (Meehan et al. Reference Meehan, Stedman, Parker, Curtis and Jones2017). Hence, both staffing models are likely to be novel for consumers engaged in the study.

Table 1. Service characteristics at clinical and integrated staffing model CCU sites, adapted from DE-IDENTIFIED et al. 2016 (Parker et al. Reference Parker, Dark, Vilic, McCann, O'Sullivan, Doyle and Lendich2016b)

a CCUs accept involuntary consumers but with a focus on voluntary engagement with rehabilitation activities.

Participants and ethical clearance

The Metro South Human Research Ethics Committee provided ethical approval (HREC/14/QPAH/62). Convenience sampling prioritised interview allocation based on the earliest provision of consent and availability at interview times. There were no exclusion criteria. Over the timeframe of data collection, 48 of the 64 consumers admitted consented to participate.

Interview process

Semi-structured qualitative interviews (Dicicco-Bloom & Crabtree, Reference Dicicco-Bloom and Crabtree2006) explored participants’ expectations of a CCU. The interview schedule was framed by three topics about the CCU: how participants came to be there; expectations of the experience; and expectations of how this would compare to previous mental health care experiences. This paper presents an analysis of the first two topics; the third is the subject of a separate paper (Parker et al. Reference Parker, Dark, Meurk and Newman2017). Interviews were completed between December 2014 and January 2016 by an independent research assistant (EN). All interviews were conducted during the first 6 weeks of participants’ stays, and were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim by an independent transcription service. EN used field notes to verify potential transcription errors and to enhance the understandability of the transcripts.

Analysis

Characteristics of consumers at each site type were considered using independent measures t-tests and χ 2 tests using SPSSv22. De-identified transcripts were uploaded to NVivo11 (QSR, 2016) and the analysis followed a pragmatic grounded theory approach (Parker et al. Reference Parker, Dark, Newman, Korman, Meurk, Siskind and Harris2016a, Reference Parker, Dark, Newman, Korman, Rasmussen and Meurk2017a). An inductive approach was taken in the initial coding, with subsequent confirmation or refutation of emergent themes being guided by an inductive–deductive interplay. Data collection, analysis and theorising occurred in tandem from the outset. Following completion of three interviews at each site EN, CM, SP and FD considered the emerging themes, coding framework, adequacy of the interview schedule, and estimated the sample size likely to achieve thematic saturation. At this stage, the interviewer was instructed not to use the word ‘recovery’ unless this was introduced by the participant. A prompt – ‘what does recovery mean to you?’ – was given, if the participant used the term ‘recovery’. The rationale was to reduce the risk of leading the interviewee, allow for implicit concepts of recovery to emerge, and reduce ambiguity when the term was stated. We judged that thematic saturation was reached following interviews with eight consumers from each of the three sites (n = 24).

Once agreement was reached on the initial coding framework, SP coded all subsequent interviews. The team worked collaboratively to explore limitations in the coding and the extent to which emerging theory was grounded in the data. Interview material was split during the analysis phase to distinguish the static ‘concept’ of what consumers expected a CCU to be (topics 1 and 2) and dynamic expectations of how this would differ from previous care (topic 3). Illustrative excerpts were selected based on author consensus. Excerpts are tagged with the staffing model [‘INT’ (integrated), ‘CLIN’ (clinical)] followed by a random three-digit identifier (e.g. CLIN053). The following quantifiers were applied to indicate the number of participants discussing a concept: some (N = 1–11); half (N = 12); most (N = 13–23) and all (N = 24). Two CCU staff with a lived experience of mental illness (DH and WM) provided written feedback on manuscript drafts. Before finalising the findings and a conceptual map, reflecting the research team's interpretation concepts best synthesising the data, these were presented to 29 current residents and 19 staff across the CCU sites for feedback. This process confirmed the applicability of the analysis to consumers and staff working directly in the investigation context.

Results

Participant characteristics

Table 2 summarises participant characteristics. The average interview length was 20 min (median 18 min, range 11–32 min). Males (75%) and those with a primary diagnosis of schizophrenia (87%) predominated; this was consistent with patterns of service utilisation observed in a 2013 state-wide audit (Meehan et al. Reference Meehan, Stedman, Parker, Curtis and Jones2017). However, the average age of the participants (![]() ${\bar x} = 30.1$, s.d. = 8, range 19–47 years) and the proportion subject to an involuntary treatment order (50%) were both lower than in the state-wide audit (which were

${\bar x} = 30.1$, s.d. = 8, range 19–47 years) and the proportion subject to an involuntary treatment order (50%) were both lower than in the state-wide audit (which were ![]() ${\bar x} = 38.5$ years, 65% respectively).

${\bar x} = 38.5$ years, 65% respectively).

Table 2. Characteristics of consumers interviewed at integrated and clinical staffing model sites. Bracketed values are standard deviations

HoNOS: Health of the Nation Outcome Scale; LSP-16: Life Skills Profile - 16; MHI: Mental Health Inventory-38.

a ICD-10 diagnoses F20.x and F25.x.

#p > 0.05 when a single outlier was excluded from the analysis.

Three statistically significant differences between integrated and clinical staffing model sites were apparent: At the integrated sites, a higher proportion of admissions were from the community v. inpatient facilities than for the clinical site (χ 2(1) = 9.38, p < 0.05); total chlorpromazine equivalence (Kroken et al. Reference Kroken, Johnsen, Ruud, Wentzel-Larsen and Jorgensen2009) for the clinical staffing model group was higher than for the integrated staffing model participants (t (22) = −2.40, p < 0.05), significance was not sustained when a single outlier from the clinical staffing model group was excluded; and 38% of consumers at the integrated site were receiving clozapine on admission compared with none (0%) at the clinical site (χ 2(1) = 4.00, p < .05).

Qualitative analysis

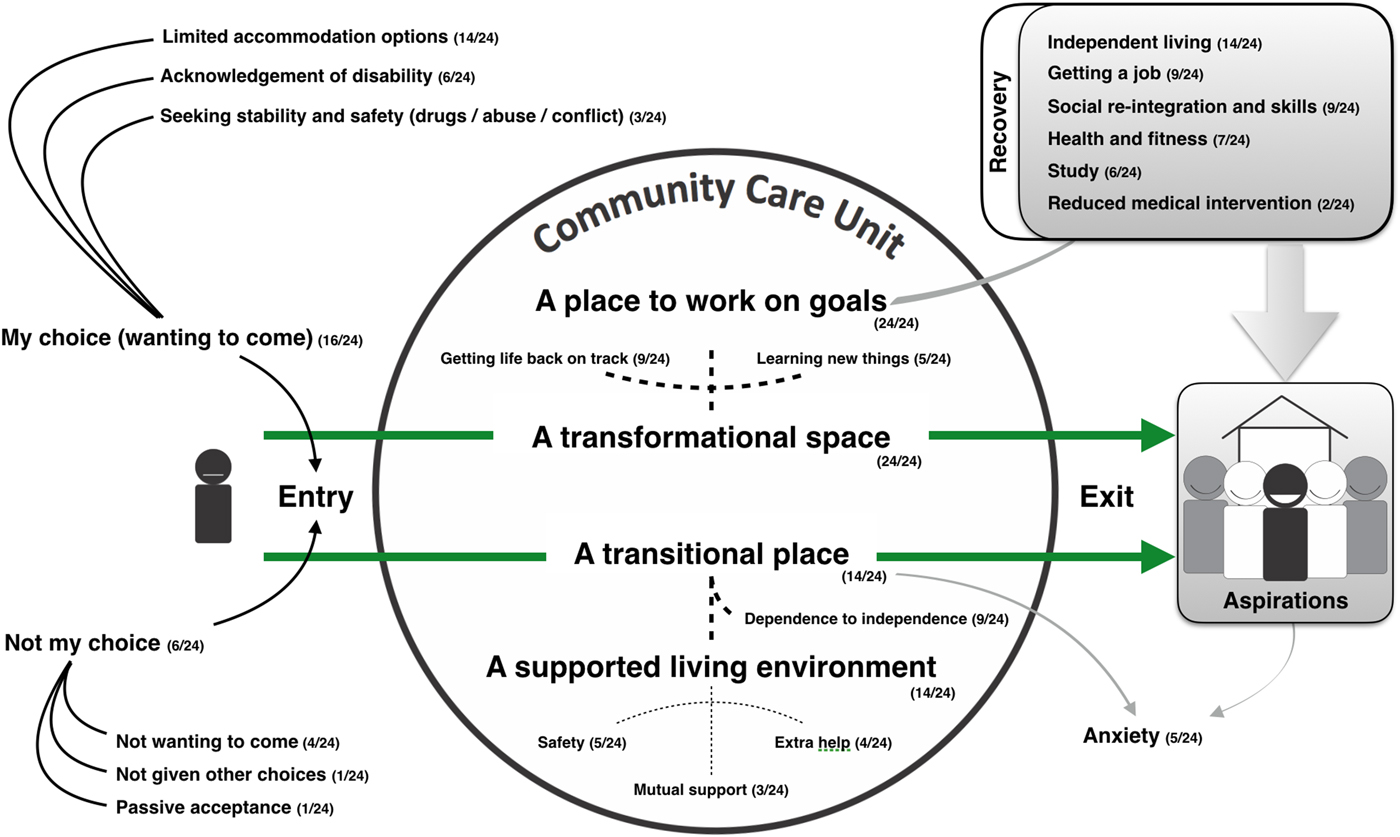

Themes were consistent across the integrated (n = 16) and clinical sites (n = 8). Consequently, we grouped transcripts across all sites for analysis. The absence of divergence was expected given that the CCU was likely to be a novel care setting for all consumers and that the sites operate a shared model of service. The CCU was viewed as a ‘transformational space’ and a ‘transitional place’, with content speaking to the themes of ‘why am I here?’ and ‘what is the CCU to me?’ These concepts and themes are conceptualised in Fig. 1 and elaborated below.

Fig. 1. Key concepts, themes and their inter-relationships identified in exploring consumers concepts of a community-based residential mental health rehabilitation unit.

Why am I here?

Most participants (16/24) indicated they were involved in the decision to come to the CCU:

Yeah, I chose to come here. I was given the option, and I decided I'd jump at the opportunity. (CLIN053)

I was given a few different options from my caseworker, and this one sounded like the best one for me. (INT004)

However, some participants (6/24) spoke of not being involved in the decision, describing not wanting to come (4/24), not being given other options (1/24) or passively accepting the directions of others (1/24). Reasons provided by these participants for being at the CCU included pressure from family and threats from clinicians:

[T]here was a doctor back at the [Community clinic], he pretty much threatened me with injections if I didn't come here. (INT032)

I had heard of it before and didn't want to come here. I thought it would be more clinical…like the hospital. (CLIN090)

The most common motivator given for coming to the CCU was housing insecurity (14/24):

Um, no I don't think there was very many [other places] to choose from. There were hostels, but there's too many drugs there, so I didn't want to go there [laughs]. (CLIN094)

I was going through homelessness at the time, so having a place that I could actually stay sounded great. (INT056)

Some participants identified disability or that they were not able to achieve their goals on their own, as a reason for coming (6/24):

[Coming] for the assisted living to basically get the assistance for the mental health, get to the point of living independently and that sort of thing. (INT098)

[I]n all honesty, I'm probably not quite capable of looking after myself fully now, you know. (CLIN053)

The sub-theme of the need for additional help to stabilise symptoms was also discussed by some participants (4/24): I'm struggling with a few things myself, so I really want to work with …the clinical staff and the doctors to try and get on top of ah what I'm going through. And be able to manage it, control it a lot better. (INT050)

Seeking safety from family conflict and dysfunctional home environments were mentioned by some participants as a motivator for coming to the CCU (3/24):

I don't know, it's just oh well, arguing a lot, a lot more with parents, so I'm like just get out of that scene. (INT066)

Yeah, like the problem I had when I was at home was my brother is a dealer, so there was always drugs there for me. (INT004)

The CCU provides a transformational space

All participants articulated the expectation that they would experience positive change through staying at the CCU (24/24). This theme encompassed the ideas that the CCU is a place to work on goals, to get your life back on track and to learn new things.

A place to work on goals

Working on personal goals was central to participants’ understanding of the CCU (24/24):

I'm just trying to use this place really to achieve my goals, you know pushing my boundaries with anxiety and building confidence, learning living skills such as cooking. (INT004)

Six categories of goals were identified through content analysis and are summarised in Table 3. Participants mentioned between one and five of these goals; half discussed only one type of goal.

Table 3. Goals categories as identified by participants

Getting life back on track

Participants viewed the CCU as a place that would help improve their life trajectory (9/24). This concept was neatly encapsulated by the phrases ‘get your shit together’ (INT050) and ‘get on track and stay on track’ (CLIN079):

[Be]’cause when people come from mental illnesses, or they feel like they've made too many mistakes or they can't – they can't fix them but [you develop] more pride…[and] confidence, you know, being here. (INT082)

A related concept was that of a second chance:

[I]t's an opportunity, another opportunity in my life and I'm willing to take it on board and do the right thing and change my life around because they've given me the chance…[B]ecome what I've been wanting to be a long time. (INT082)

The expectation was generally one of transformation to a new or better self, rather than return to a pre-illness state.

A place to learn new things

The concept of a CCU as a place of learning was identified by some participants (5/24) who saw opportunities to learn new things, particularly living skills:

We're all here to get better and get, um, our independence and try and learn to - how to learn to live on our own and stuff like that. (CLIN094)

The CCU is a transitional place

Most participants considered the CCU to be a transitional place (21/24). This concept reflected the liminality of the CCU as a temporary supported living environment (14/24) or a ‘stepping stone’ (INT082) to increased independence (9/24).

A supported living environment

Participants considered the CCU as ‘a place of support’ (CLIN090) to assist them to live in the community. Some participants emphasised its role as a place of safety (5/24), including protection from drug use (3/24) and being abused by others (2/24):

[T]hey don't tolerate problematic behaviour and especially in…regards to addictions. So I feel safe. (CLIN090)

…I feel safe here, that's just a main thing…‘Cause I don't really like men. Men have abused me and stuff. (INT082)

Some participants appreciated the ‘extra help’ (CLIN079) that was available (4/24):

I feel like here there's a whole team behind me…It's not just me on my own. (CLIN100)

This included valuing mutual support from co-residents (3/24):

[H]elping other people as well…people have problems and some people either ignore it or some people…go and they try and help them out…just tell them about my experience and see if they can absorb it and understand it and learn from it as well. (CLIN041)

Shifting from dependence to independence

Some participants expected that the CCU would facilitate their transition from dependence on others to independence (9/24), including from acute/sub-acute inpatient facilities (5/24) and the parental home (4/24).

[T]hey're sort of teaching you what the real world will be like when you're out on your own [after acute inpatient care]. (CLIN094)

Some expected that the CCU would help them access external agencies and resources (3/24):

[T]hey are helping me, um, with other things that are more complex, such as housing and…dealing with [welfare agencies] and…connecting with an employment consultant and stuff like that. (CLIN090)

A transitional environment is anxiety provoking

The transitional nature of the CCU and participants’ lack of control over service entry and exit was identified as a source of anxiety for some participants (5/24):

I almost fear for, um, where I will go after this because it couldn't be as good…I say to myself…you've just got to enjoy the experience, and maybe one day I'll live in a…nice place like this again [laughs]. (CLIN090)

Discussion

Consumers’ goals and understanding of the functions of a CCU were consistent with the designated model of service (Queensland Health, 2015), frameworks for recovery-oriented mental health practice (Australian Health Ministers Advisory Council, 2013) and the perceptions of CCU staff (Parker et al. Reference Parker, Dark, Newman, Korman, Rasmussen and Meurk2017a). The concept of recovery consumers articulated aligned with the notion of ‘personal recovery’ rather than ‘clinical’ or ‘service-defined’ recovery (Le Boutillier et al. Reference Le Boutillie, Chevalier, Lawrence, Leamy, Bird, Macpherson, Williams and Slade2015), with the expectation being personal transformation rather than restoration of past functioning. However, push factors, most prominently housing insecurity and homelessness, were more common drivers for engagement than pull factors (i.e. being attracted by the opportunities the CCU affords for rehabilitation).

Emphasis on personal recovery

Consumers’ emphasis on personal recovery is consistent with findings from other qualitative evaluations of Australian mental health consumers (Hungerford & Fox, Reference Hungerford and Fox2014), and sub-acute residential settings specifically (McKenna et al. Reference McKenna, Oakes, Fourniotis, Toomey and Furness2016; Thomas & Rickwood, Reference Thomas and Rickwood2016). In interpreting these findings, McKenna et al. (Reference McKenna, Oakes, Fourniotis, Toomey and Furness2016) suggested that the CCU they examined was evolving towards delivering more person-centred care, with staff being active participants in this journey. Yet, the two qualitative studies considering CCU staff perspectives note tensions between personal and clinical recovery concepts in practice (McKenna et al. Reference McKenna, Oakes, Fourniotis, Toomey and Furness2016; Parker et al. Reference Parker, Dark, Newman, Korman, Rasmussen and Meurk2017a). Misalignment between expectations of recovery held by consumers at these services may underlie the problems with engagement that often occur at rehabilitation services.

Accommodation instability and service engagement

The prominence of accommodation instability as a driver of engagement is consistent with a survey of unmet needs in rehabilitation service users in the United Kingdom (Killaspy et al. Reference Killaspy, Rambarran and Bledin2008) which found that consumers prioritised financial and accommodation needs over psychological distress. The lack of alternative residential options for many participants raises concerns about the impact of duress on the decision to engage with the rehabilitation service and that unmet needs within the service system environment might negatively impact CCU consumers’ outcomes.

Our previous study, exploring the staff experience of working at the clinical site, suggested that CCUs being used to resolve accommodation crisis undermined consumers’ ‘rehabilitation readiness’ (Parker et al. Reference Parker, Dark, Newman, Korman, Rasmussen and Meurk2017a). Consumers’ views, however, suggest that even where accommodation instability is a driver of engagement, consumers still express hope that the experience will be beneficial. Engagement in rehabilitation settings is co-constructed and multidimensional, and does not simply reflect the behaviour of consumers (Bright et al. Reference Bright, Kayes, Worrall and McPherson2015). Participants grasped the rehabilitation concept and their views were positive and consistent with those of staff (Parker et al. Reference Parker, Dark, Newman, Korman, Rasmussen and Meurk2017a). Most indicated active involvement in the decision to come to the CCU. These findings are important to note for future evaluation of outcomes for this service, particularly as other studies have offered lack of knowledge and negative attitudes towards rehabilitation as explanations for dis-engagement (Moran et al. Reference Moran, Baruch, Azaiza and Lachman2016).

The priority of our participants was accommodation and not rehabilitation; despite this they also expected that the service would assist them with their goals. Lack of alignment is a known driver of service disengagement (Smith et al. Reference Smith, Easter, Pollock, Pope and Wisdom2013); this highlights the importance of facilitating continued staff and consumer co-creation of these models of service. Regardless of someone's reasons for coming to a rehabilitation service, it is imperative for staff to find ways to increase their awareness of, and motivate their engagement with, evidence-based interventions relevant to their goals. Little is known about the best ways to achieve this (Cook et al. Reference Cook, Mundy, Killaspy, Taylor, Freeman, Craig and King2016) and it should be a focus of future research.

Challenges associated with transitional residential environments

Participants highlighted the anxiety-provoking nature of a transitional supportive environment. The only published long-term follow-up study of former CCU consumers found that many experience high levels of ongoing disability, dependency and impoverished social networks (Chopra & Herrman, Reference Chopra and Herrman2011). This suggests that consumers’ anxiety about their journey post-CCU is justified. In the USA and increasingly in Australia, there has been strong advocacy for alternative approaches to transitional services such as Housing First (Barbato et al. Reference Barbato, Agnetti, D'Avanzo, Frova, Guerrini and Tettamanti2007; Johnson et al. Reference Johnson, Parkinson and Parsell2012). These approaches advocate that stable and permanent accommodation is a key ingredient and not an outcome of recovery. There is promising evidence about the effectiveness of Housing First approaches in facilitating housing tenure (Goering & Streiner, Reference Goering and Streiner2015) and the approach is consistent with consumers’ stated priorities (Killaspy et al. Reference Killaspy, Rambarran and Bledin2008). However, the extent to which this is a viable alternative for the high needs group typically referred to a CCU is unknown.

Limitations

These findings are contextually dependent, and generalisation requires consideration of case-to-case similarity. The absence of similar studies in other settings limits opportunities to explore the concordance of the conceptual model across settings. The initial coding framework was developed by a single rater (SP) holding dual roles as a clinician–researcher. The risk of preconceptions biasing the analysis was addressed through the diversity of the analytic team and the use of respondent verification. Power differentials inherent in the dual roles of several members of the research team and participant anxiety about the transitional nature of CCU support may have limited negative disclosures (Karnieli-Miller et al. Reference Karnieli-Miller, Strier and Pessach2009). Multiple efforts were taken to facilitate a safe space for participation, including interviewer independence and transcript de-identification prior to analysis by the research team.

Implications

Consumers’ motivation for engaging with the rehabilitation service is predominantly driven by accommodation instability. The implications of this should be examined further. It is imperative that staff at residential rehabilitation services actively explore the relevance of rehabilitation support with consumers. However, it is unclear how to best structure these conversations and motivate engagement. The longitudinal qualitative data set we are collecting, and engagement it fosters, is one way to work towards co-creating mutually acceptable and viable service configurations. These data will allow comparison of consumers’ expectations with their subsequent experience and outcomes of care under the integrated and clinical staffing models. In particular, the extent to which expectations of personal recovery are realised at these services (or not) will be explored in later phases of the longitudinal study.

Contributors

SP, FD, EN and CM contributed to the parent study protocol. EN completed all interviews under advisory support from CM. SP developed the initial coding framework, which was refined in consultation with CM, FD and EN. All authors contributed to the analysis, interpretation and review of the manuscript initially drafted by SP.

Conflict of interest

None.

Ethical standards

The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committees on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008.

Availability of data and materials

In accordance with the ethical approval, full transcript data are not publically available. This restriction was due to the re-identifiable nature of the transcripts and the importance of establishing a safe space for participant disclosure.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S2045796017000749.